Article

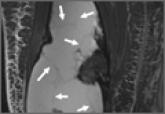

Spontaneous, Chronic Expanding Posterior Thigh Hematoma Mimicking Soft-Tissue Sarcoma in a Morbidly Obese Pregnant Woman

- Author:

- Everhart JS

- Fajolu OK

- Mayerson JL

Soft-tissue sarcomas are rare and often confused for more common and benign disorders during diagnosis. Chronic expanding hematomas are...