User login

Treatment and Current Policies on Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in the US Military

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB)(also referred to as razor bumps) is a skin disease of the face and neck caused by shaving and remains prevalent in the US Military. As the sharpened ends of curly hair strands penetrate back into the epidermis, they can trigger inflammatory reactions, leading to papules and pustules as well as hyperpigmentation and scarring.1 Although anyone with thick curly hair can develop PFB, Black individuals are disproportionately affected, with 45% to 83% reporting PFB symptoms compared with 18% of White individuals.2 In this article, we review the treatments and current policies on PFB in the military.

Treatment Options

Shaving Guidelines—Daily shaving remains the grooming standard for US service members who are encouraged to follow prescribed grooming techniques to prevent mild cases of PFB, defined as having “few, scattered papules with scant hair growth of the beard area,” according to the technical bulletin of the US Army, which provides the most detailed guidelines among the branches.3 The bulletin recommends hydrating the face with warm water, followed by a preshave lotion and shaving with a single pass superiorly to inferiorly. Following shaving, postrazor hydration lotion is recommended. Single-bladed razors are preferred, as there is less trauma to existing PFB and less potential for hair retraction under the epidermis, though multibladed razors can be used with adequate preshave and postrazor hydration.4 Shaving can be undertaken in the evening to ensure adequate time for preshave preparation and postshave hydration. Waterless shaving uses waterless soaps or lotions containing α-hydroxy acid just prior to shaving in lieu of preshaving and postshaving procedures.4

Topical Medications—For PFB cases that are recalcitrant to management by changes in shaving, topical retinoids are commonly prescribed, as they reduce follicular hyperkeratosis that may lead to PFB.5 The Army medical bulletin recommends a pea-sized amount of tretinoin cream or gel 0.025%, 0.05%, or 0.1% for moderate cases, defined as “heavier beard growth, more scattered papules, no evidence of pustules or denudation.”3 Adapalene cream 0.1% may be used instead of tretinoin for sensitive skin. Oral doxycycline or topical benzoyl peroxide–clindamycin may be added for secondary bacterial skin infections. Clinical trials have demonstrated that combination benzoyl peroxide–clindamycin significantly reduces papules and pustules in up to 63% of patients with PFB (P<.029).6 Azelaic acid can be prescribed for prominent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The bulletin also suggests depilatories such as barium sulfide to obtund the hair ends and make them less likely to re-enter the skin surface, though it notes low compliance rates due to strong sulfur odor, messy application, and irritation and reactions to ingredients in the preparations.4

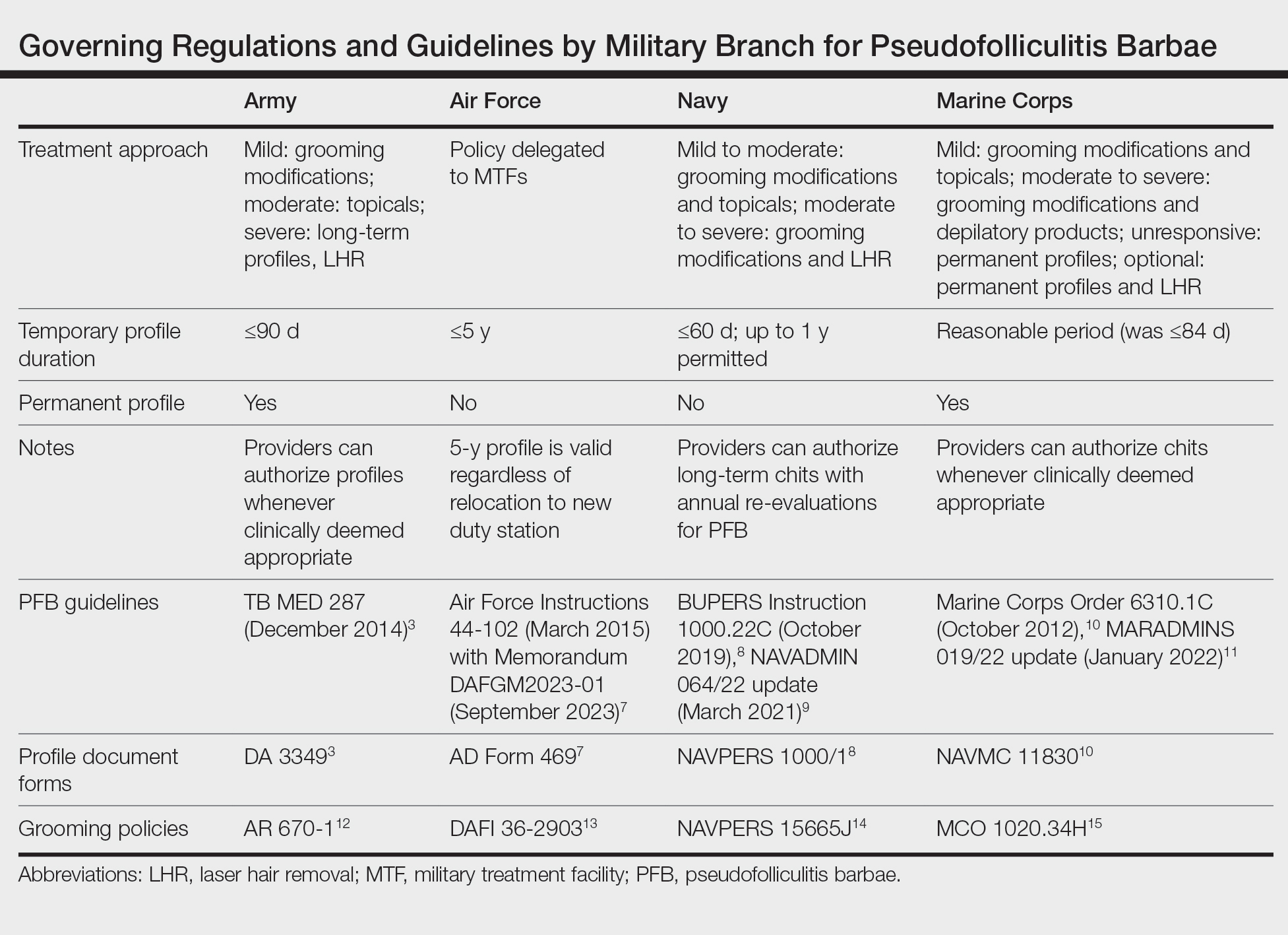

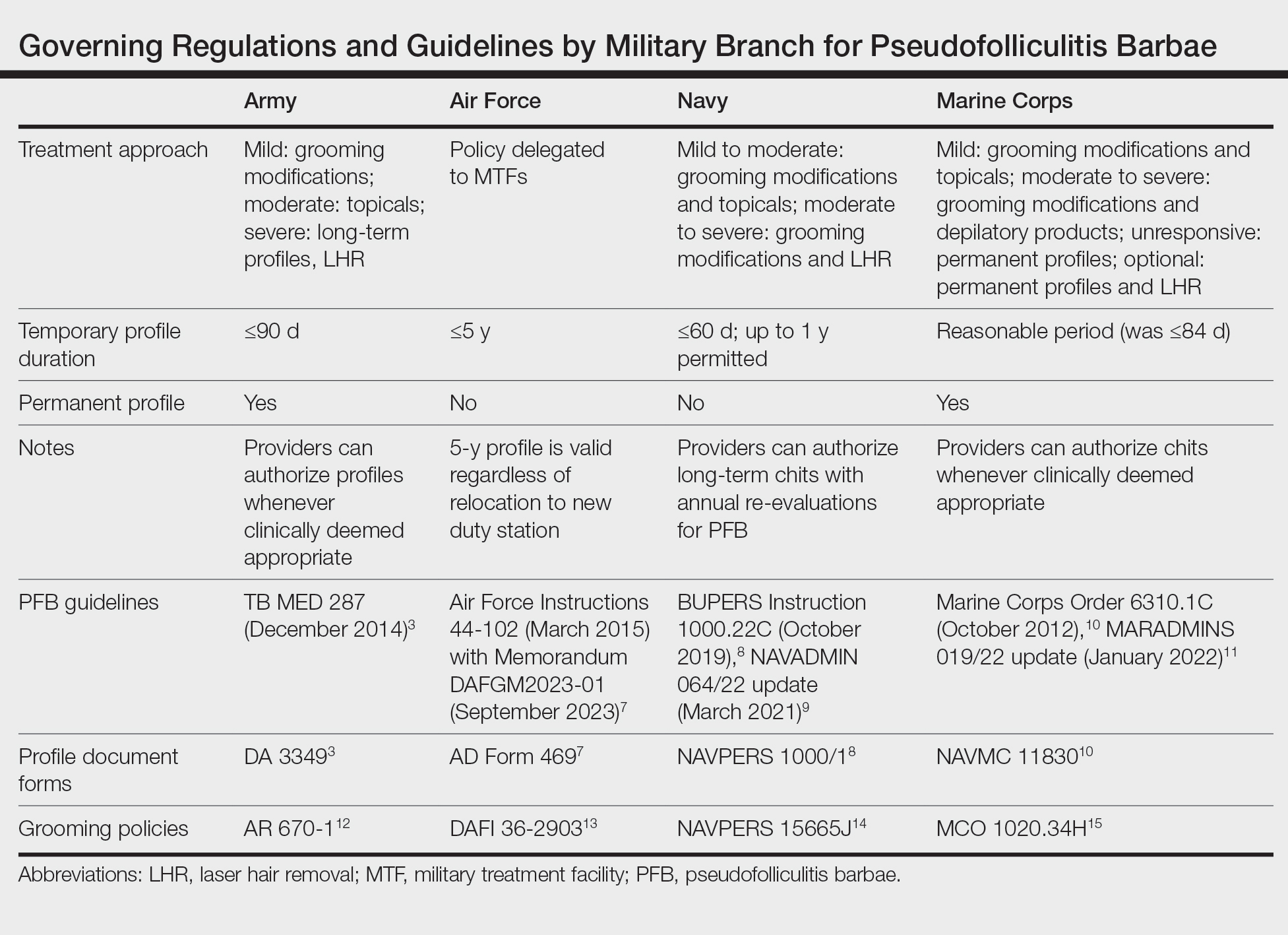

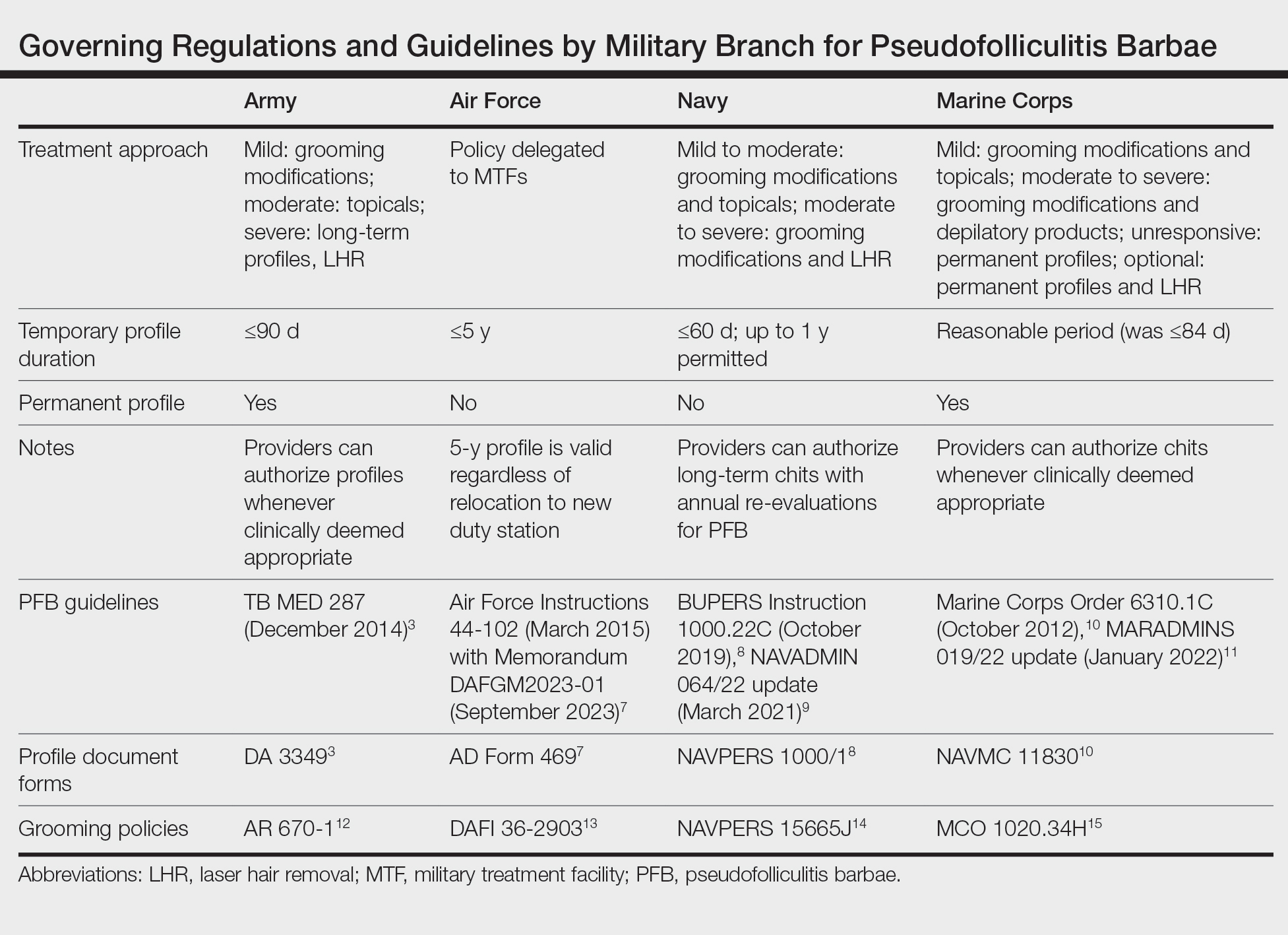

Shaving Waivers and Laser Hair Removal—The definitive treatment of PFB is to not shave, and a shaving waiver or laser hair removal (LHR) are the best options for severe PFB or PFB refractory to other treatments. A shaving waiver (or shaving profile) allows for growth of up to 0.25 inches of facial hair with maintenance of the length using clippers. The shaving profile typically is issued by the referring primary care manager (PCM) but also can be recommended by a dermatologist. Each military branch implements different regulations on shaving profiles, which complicates care delivery at joint-service military treatment facilities (MTFs). The Table provides guidelines that govern the management of PFB by the US Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps. The issuance and duration of shaving waivers vary by service.

Laser hair removal therapy uses high-wavelength lasers that largely bypass the melanocyte-containing basal layer and selectively target hair follicles located deeper in the skin, which results in precise hair reduction with relative sparing of the epidermis.16 Clinical trials at military clinics have demonstrated that treatments with the 1064-nm long-pulse Nd:YAG laser generally are safe and effective in impeding hair growth in Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI.17 This laser, along with the Alexandrite 755-nm long-pulse laser for Fitzpatrick skin types I to III, is widely available and used for LHR at MTFs that house dermatologists. Eflornithine cream 13.9%, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat hirsutism, can be used as monotherapy for treatment of PFB and has a synergistic depilatory effect in PFB patients when used in conjunction with LHR.18,19 Laser hair removal treatments can induce a permanent change in facial hair density and pattern of growth. Side effects and complications of LHR include discomfort during treatment and, in rare instances, blistering and dyspigmentation of the skin as well as paradoxical hair growth.17

TRICARE, the uniformed health care program, covers LHR in the civilian sector if the following criteria are met: candidates must work in an environment that may require breathing protection, and they must have failed conservative therapy; an MTF dermatologist must evaluate each case and attempt LHR at an MTF to limit outside referrals; and the MTF dermatologist must process each outside referral claim to completion and ensure that the LHR is rendered by a civilian dermatologist and is consistent with branch-specific policies.20

Service Policies on PFB

Army—

The technical bulletin also allows a permanent shaving profile for soldiers who demonstrate a severe adverse reaction to treatment or progression of the disease despite a trial of all these methods.3 The regulation stipulates that 0.125 to 0.25 inches of beard growth usually is sufficient to prevent PFB. Patients on profiles must be re-evaluated by a PCM or a dermatologist at least once a year.3

Air Force—Air Force Instruction 44-102 delegates PFB treatment and management strategies to each individual MTF, which allows for decentralized management of PFB, resulting in treatment protocols that can differ from one MTF to another.7 Since 2020, waivers have been valid for 5 years regardless of deployment or permanent change of station location. Previously, shaving profiles required annual renewals.7 Special duties, such as Honor Guard, Thunderbirds, Special Warfare Mission Support, recruiters, and the Air Force Band, often follow the professional appearance standards more strictly. Until recently, the Honor Guard used to reassign those with long-term medical shaving waivers but now allows airmen with shaving profiles to serve with exceptions (eg, shaving before ceremonies).21

Navy—BUPERS (Bureau of Naval Personnel) Instruction 1000.22C divides PFB severity into 2 categories.8 For mild to moderate PFB cases, topical tretinoin and adapalene are recommended, along with improved shaving hygiene practices. As an alternative to topical steroids, topical eflornithine monotherapy can be used twice daily for 60 days. For moderate to severe PFB cases, continued grooming modifications and LHR at military clinics with dermatologic services are expected.8

Naval administrative memorandum NAVADMIN 064/22 (released in 2022) no longer requires sailors with a shaving “chit,” or shaving waiver, to fully grow out their beards.9 Sailors may now outline or edge their beards as long as doing so does not trigger a skin irritation or outbreak. Furthermore, sailors are no longer required to carry a physical copy of their shaving chit at all times. Laser hair removal for sailors with PFB is now considered optional, whereas sailors with severe PFB were previously expected to receive LHR.9

Marine Corps—The Marine Corps endorses a 4-phase treatment algorithm (Table). As of January 2022, permanent shaving chits are authorized. Marines no longer need to carry physical copies of their chits at all times and cannot be separated from service because of PFB.10 New updates explicitly state that medical officers, not the commanding officers, now have final authority for granting shaving chits.11

Final Thoughts

The Army provides the most detailed bulletin, which defines the clinical features and treatments expected for each stage of PFB. All 4 service branches permit temporary profiles, albeit for different lengths of time. However, only the Army and the Marine Corps currently authorize permanent shaving waivers if all treatments mentioned in their respective bulletins have failed.

The Air Force has adopted the most decentralized approach, in which each MTF is responsible for implementing its own treatment protocols and definitions. Air Force regulations now authorize a 5-year shaving profile for medical reasons, including PFB. The Air Force also has spearheaded efforts to create more inclusive policies. A study of 10,000 active-duty male Air Force members conducted by Air Force physicians found that shaving waivers were associated with longer times to promotion. Although self-identified race was not independently linked to longer promotion times, more Black service members were affected because of a higher prevalence of PFB and shaving profiles.22

The Navy has outlined the most specific timeline for therapy for PFB. The regulations allow a 60-day temporary shaving chit that expires on the day of the appointment with the dermatologist or PCM. Although sailors were previously mandated to fully grow out their beards without modifications during the 60-day shaving chit period, Navy leadership recently overturned these requirements. However, permanent shaving chits are still not authorized in the Navy.

Service members are trying to destigmatize shaving profiles and facial hair in our military. A Facebook group called DoD Beard Action Initiative has more than 17,000 members and was created in 2021 to compile testimonies and data regarding the effects of PFB on airmen.23 Soldiers also have petitioned for growing beards in the garrison environment with more than 100,000 signatures, citing that North Atlantic Treaty Organization allied nations permit beard growth in their respective ranks.24 A Sikh marine captain recently won a lawsuit against the US Department of the Navy to maintain a beard with a turban in uniform on religious grounds.25

The clean-shaven look remains standard across the military, not only for uniformity of appearance but also for safety concerns. The Naval Safety Center’s ALSAFE report concluded that any facial hair impedes a tight fit of gas masks, which can be lethal in chemical warfare. However, the report did not explore how different hair lengths would affect the seal of gas masks.26 It remains unknown how 0.25 inch of facial hair, the maximum hair length authorized for most PFB patients, affects the seal. Department of Defense occupational health researchers currently are assessing how each specific facial hair length diminishes the effectiveness of gas masks.27

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to frequent N95 respirator wear in the military. It is likely that growing a long beard disrupts the fitting of N95 respirators and could endanger service members, especially in clinical settings. However, one study confirmed that 0.125 inch of facial hair still results in 98% effectiveness in filtering particles for the respirator wearers.28 Although unverified, it is surmisable that 0.25 inch of facial hair will likely not render all respirators useless. However, current Occupational Safety and Health Administration guidelines require fit tests to be conducted only on clean-shaven faces.29 Effectively, service members with facial hair cannot be fit-tested for N95 respirators.

More research is needed to optimize treatment protocols and regulations for PFB in our military. As long as the current grooming standards remain in place, treatment of PFB will be a controversial topic. Guidelines will need to be continuously updated to balance the needs of our service members and to minimize risk to unit safety and mission success. Department of Defense Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1, revised in late 2022, now no longer designates PFB as a condition that disqualifies a candidate from entering service in any military branch.30 The Department of Defense is demonstrating active research and adoption of policies regarding PFB that will benefit our service members.

- Perry PK, Cook-Bolden FE, Rahman Z, et al. Defining pseudofolliculitis barbae in 2001: a review of the literature and current trends. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S113-S119.

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38:24-27.

- Department of the Army. TB MED 287. Pseudofolliculitis of the beard and acne keloidalis nuchae. Published December 10, 2014. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/tbmed287.pdf

- Tshudy M, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the U.S. military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:52-57.

- Kligman AM, Mills OH. Pseudofolliculitis of the beard and topically applied tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1973;107:551-552.

- Cook-Bolden FE, Barba A, Halder R, et al. Twice-daily applications of benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel versus vehicle in the treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):18-24.

- US Department of the Air Force. Air Force Instruction 44-102. Medical Care Management. March 17, 2015. Updated July 13, 2022. Accessed October 1, 2022. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_sg/publication/afi44-102/afi44-102.pdf

- Chief of Naval Personnel, Department of the Navy. BUPERS Instruction 1000.22C. Management of Navy Uniformed Personnel Diagnosed With Pseudofolliculitis Barbae. October 8, 2019. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Reference/Instructions/BUPERS/BUPERSINST%201000.22C%20Signed.pdf?ver=iby4-mqcxYCTM1t3AOsqxA%3D%3D

- Chief of Naval Operations, Department of the Navy. NAVADMIN 064/22. BUPERSINST 1000,22C Management of Navy uniformed personnel diagnosed with pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) update. Published March 9, 2022. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Messages/NAVADMIN/NAV2022/NAV22064.txt?ver=bc2HUJnvp6q1y2E5vOSp-g%3D%3D

- Commandant of the Marine Corps, Department of the Navy. Marine Corps Order 6310.1C. Pseudofolliculitis Barbae. October 9, 2012. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/MCO%206310.1C.pdf

- US Marine Corps. Advance Notification of Change to MCO 6310.1C (Pseudofolliculitis Barbae), MCO 1900.16 CH2 (Marine Corps Retirement and Separation Manual), and MCO 1040.31 (Enlisted Retention and Career Development Program). January 21, 2022. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.marines.mil/News/Messages/Messages-Display/Article/2907104/advance-notification-of-change-to-mco-63101c-pseudofolliculitis-barbae-mco-1900

- Department of the Army. Army Regulation 670-1. Uniform and Insignia. Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia. January 26, 2021. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN30302-AR_670-1-000-WEB-1.pdf

- Department of the Air Force. Department of the Air Force Guidance Memorandum to DAFI 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of United States Air Force and United States Space Force Personnel. Published March 31, 2023. Accessed November 20, 2023. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/dafi36-2903/dafi36-2903.pdf

- United States Navy uniform regulations NAVPERS 15665J. MyNavy HR website. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/References/US-Navy-Uniforms/Uniform-Regulations/

- US Marine Corps. Marine Corps Uniform Regulations. Published May 1, 2018. Accessed November 20, 2023. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201020.34H%20v2.pdf?ver=2018-06-26-094038-137

- Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Selective photothermolysis: precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation. Science. 1983;220:524-527.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

- Xia Y, Cho SC, Howard RS, et al. Topical eflornithine hydrochloride improves effectiveness of standard laser hair removal for treating pseudofolliculitis barbae: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:694-699.

- Shokeir H, Samy N, Taymour M. Pseudofolliculitis barbae treatment: efficacy of topical eflornithine, long-pulsed Nd-YAG laser versus their combination. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3517-3525. doi:10.1111/jocd.14027

- TRICARE operations manual 6010.59-M. Supplemental Health Care Program (SHCP)—chapter 17. Contractor responsibilities. Military Health System and Defense Health Agency website. Revised November 5, 2021. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://manuals.health.mil/pages/DisplayManualHtmlFile/2022-08-31/AsOf/TO15/C17S3.html

- Air Force Honor Guard: Recruiting. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.honorguard.af.mil/About-Us/Recruiting/

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247.

- DoD Beard Action Initiative Facebook group. Accessed November 5, 2023. https://www.facebook.com/groups/326068578791063/

- Geske R. Petition gets 95K signatures in push for facial hair for soldiers. KWTX. February 4, 2021. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.kwtx.com/2021/02/04/petition-gets-95k-signatures-in-push-for-facial-hair-for-soldiers/

- Athey P. A Sikh marine is now allowed to wear a turban in uniform. Marine Corps Times. October 5, 2021. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.marinecorpstimes.com/news/your-marine-corps/2021/10/05/a-sikh-marine-is-now-allowed-to-wear-a-turban-in-uniform

- US Department of the Navy. Face Seal Guidance update (ALSAFE 18-008). Naval Safety Center. Published November 18, 2018. Accessed October 22, 2022. https://navalsafetycommand.navy.mil/Portals/29/ALSAFE18-008.pdf

- Garland C. Navy and Marine Corps to study facial hair’s effect on gas masks, lawsuit reveals. Stars and Stripes. January 25, 2022. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.stripes.com/branches/navy/2022-01-25/court-oversee-navy-marine-gas-mask-facial-hair-study-4410015.html

- Floyd EL, Henry JB, Johnson DL. Influence of facial hair length, coarseness, and areal density on seal leakage of a tight-fitting half-face respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;15:334-340.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Occupational Safety and Health Standards 1910.134 App A. Fit Testing Procedures—General Requirements. US Department of Labor. April 23, 1998. Updated August 4, 2004. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.134AppA

- US Department of Defense. DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1. Medical Standards for Military Service: Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction. November 16, 2022. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003_vol1.PDF?ver=7fhqacc0jGX_R9_1iexudA%3D%3D

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB)(also referred to as razor bumps) is a skin disease of the face and neck caused by shaving and remains prevalent in the US Military. As the sharpened ends of curly hair strands penetrate back into the epidermis, they can trigger inflammatory reactions, leading to papules and pustules as well as hyperpigmentation and scarring.1 Although anyone with thick curly hair can develop PFB, Black individuals are disproportionately affected, with 45% to 83% reporting PFB symptoms compared with 18% of White individuals.2 In this article, we review the treatments and current policies on PFB in the military.

Treatment Options

Shaving Guidelines—Daily shaving remains the grooming standard for US service members who are encouraged to follow prescribed grooming techniques to prevent mild cases of PFB, defined as having “few, scattered papules with scant hair growth of the beard area,” according to the technical bulletin of the US Army, which provides the most detailed guidelines among the branches.3 The bulletin recommends hydrating the face with warm water, followed by a preshave lotion and shaving with a single pass superiorly to inferiorly. Following shaving, postrazor hydration lotion is recommended. Single-bladed razors are preferred, as there is less trauma to existing PFB and less potential for hair retraction under the epidermis, though multibladed razors can be used with adequate preshave and postrazor hydration.4 Shaving can be undertaken in the evening to ensure adequate time for preshave preparation and postshave hydration. Waterless shaving uses waterless soaps or lotions containing α-hydroxy acid just prior to shaving in lieu of preshaving and postshaving procedures.4

Topical Medications—For PFB cases that are recalcitrant to management by changes in shaving, topical retinoids are commonly prescribed, as they reduce follicular hyperkeratosis that may lead to PFB.5 The Army medical bulletin recommends a pea-sized amount of tretinoin cream or gel 0.025%, 0.05%, or 0.1% for moderate cases, defined as “heavier beard growth, more scattered papules, no evidence of pustules or denudation.”3 Adapalene cream 0.1% may be used instead of tretinoin for sensitive skin. Oral doxycycline or topical benzoyl peroxide–clindamycin may be added for secondary bacterial skin infections. Clinical trials have demonstrated that combination benzoyl peroxide–clindamycin significantly reduces papules and pustules in up to 63% of patients with PFB (P<.029).6 Azelaic acid can be prescribed for prominent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The bulletin also suggests depilatories such as barium sulfide to obtund the hair ends and make them less likely to re-enter the skin surface, though it notes low compliance rates due to strong sulfur odor, messy application, and irritation and reactions to ingredients in the preparations.4

Shaving Waivers and Laser Hair Removal—The definitive treatment of PFB is to not shave, and a shaving waiver or laser hair removal (LHR) are the best options for severe PFB or PFB refractory to other treatments. A shaving waiver (or shaving profile) allows for growth of up to 0.25 inches of facial hair with maintenance of the length using clippers. The shaving profile typically is issued by the referring primary care manager (PCM) but also can be recommended by a dermatologist. Each military branch implements different regulations on shaving profiles, which complicates care delivery at joint-service military treatment facilities (MTFs). The Table provides guidelines that govern the management of PFB by the US Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps. The issuance and duration of shaving waivers vary by service.

Laser hair removal therapy uses high-wavelength lasers that largely bypass the melanocyte-containing basal layer and selectively target hair follicles located deeper in the skin, which results in precise hair reduction with relative sparing of the epidermis.16 Clinical trials at military clinics have demonstrated that treatments with the 1064-nm long-pulse Nd:YAG laser generally are safe and effective in impeding hair growth in Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI.17 This laser, along with the Alexandrite 755-nm long-pulse laser for Fitzpatrick skin types I to III, is widely available and used for LHR at MTFs that house dermatologists. Eflornithine cream 13.9%, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat hirsutism, can be used as monotherapy for treatment of PFB and has a synergistic depilatory effect in PFB patients when used in conjunction with LHR.18,19 Laser hair removal treatments can induce a permanent change in facial hair density and pattern of growth. Side effects and complications of LHR include discomfort during treatment and, in rare instances, blistering and dyspigmentation of the skin as well as paradoxical hair growth.17

TRICARE, the uniformed health care program, covers LHR in the civilian sector if the following criteria are met: candidates must work in an environment that may require breathing protection, and they must have failed conservative therapy; an MTF dermatologist must evaluate each case and attempt LHR at an MTF to limit outside referrals; and the MTF dermatologist must process each outside referral claim to completion and ensure that the LHR is rendered by a civilian dermatologist and is consistent with branch-specific policies.20

Service Policies on PFB

Army—

The technical bulletin also allows a permanent shaving profile for soldiers who demonstrate a severe adverse reaction to treatment or progression of the disease despite a trial of all these methods.3 The regulation stipulates that 0.125 to 0.25 inches of beard growth usually is sufficient to prevent PFB. Patients on profiles must be re-evaluated by a PCM or a dermatologist at least once a year.3

Air Force—Air Force Instruction 44-102 delegates PFB treatment and management strategies to each individual MTF, which allows for decentralized management of PFB, resulting in treatment protocols that can differ from one MTF to another.7 Since 2020, waivers have been valid for 5 years regardless of deployment or permanent change of station location. Previously, shaving profiles required annual renewals.7 Special duties, such as Honor Guard, Thunderbirds, Special Warfare Mission Support, recruiters, and the Air Force Band, often follow the professional appearance standards more strictly. Until recently, the Honor Guard used to reassign those with long-term medical shaving waivers but now allows airmen with shaving profiles to serve with exceptions (eg, shaving before ceremonies).21

Navy—BUPERS (Bureau of Naval Personnel) Instruction 1000.22C divides PFB severity into 2 categories.8 For mild to moderate PFB cases, topical tretinoin and adapalene are recommended, along with improved shaving hygiene practices. As an alternative to topical steroids, topical eflornithine monotherapy can be used twice daily for 60 days. For moderate to severe PFB cases, continued grooming modifications and LHR at military clinics with dermatologic services are expected.8

Naval administrative memorandum NAVADMIN 064/22 (released in 2022) no longer requires sailors with a shaving “chit,” or shaving waiver, to fully grow out their beards.9 Sailors may now outline or edge their beards as long as doing so does not trigger a skin irritation or outbreak. Furthermore, sailors are no longer required to carry a physical copy of their shaving chit at all times. Laser hair removal for sailors with PFB is now considered optional, whereas sailors with severe PFB were previously expected to receive LHR.9

Marine Corps—The Marine Corps endorses a 4-phase treatment algorithm (Table). As of January 2022, permanent shaving chits are authorized. Marines no longer need to carry physical copies of their chits at all times and cannot be separated from service because of PFB.10 New updates explicitly state that medical officers, not the commanding officers, now have final authority for granting shaving chits.11

Final Thoughts

The Army provides the most detailed bulletin, which defines the clinical features and treatments expected for each stage of PFB. All 4 service branches permit temporary profiles, albeit for different lengths of time. However, only the Army and the Marine Corps currently authorize permanent shaving waivers if all treatments mentioned in their respective bulletins have failed.

The Air Force has adopted the most decentralized approach, in which each MTF is responsible for implementing its own treatment protocols and definitions. Air Force regulations now authorize a 5-year shaving profile for medical reasons, including PFB. The Air Force also has spearheaded efforts to create more inclusive policies. A study of 10,000 active-duty male Air Force members conducted by Air Force physicians found that shaving waivers were associated with longer times to promotion. Although self-identified race was not independently linked to longer promotion times, more Black service members were affected because of a higher prevalence of PFB and shaving profiles.22

The Navy has outlined the most specific timeline for therapy for PFB. The regulations allow a 60-day temporary shaving chit that expires on the day of the appointment with the dermatologist or PCM. Although sailors were previously mandated to fully grow out their beards without modifications during the 60-day shaving chit period, Navy leadership recently overturned these requirements. However, permanent shaving chits are still not authorized in the Navy.

Service members are trying to destigmatize shaving profiles and facial hair in our military. A Facebook group called DoD Beard Action Initiative has more than 17,000 members and was created in 2021 to compile testimonies and data regarding the effects of PFB on airmen.23 Soldiers also have petitioned for growing beards in the garrison environment with more than 100,000 signatures, citing that North Atlantic Treaty Organization allied nations permit beard growth in their respective ranks.24 A Sikh marine captain recently won a lawsuit against the US Department of the Navy to maintain a beard with a turban in uniform on religious grounds.25

The clean-shaven look remains standard across the military, not only for uniformity of appearance but also for safety concerns. The Naval Safety Center’s ALSAFE report concluded that any facial hair impedes a tight fit of gas masks, which can be lethal in chemical warfare. However, the report did not explore how different hair lengths would affect the seal of gas masks.26 It remains unknown how 0.25 inch of facial hair, the maximum hair length authorized for most PFB patients, affects the seal. Department of Defense occupational health researchers currently are assessing how each specific facial hair length diminishes the effectiveness of gas masks.27

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to frequent N95 respirator wear in the military. It is likely that growing a long beard disrupts the fitting of N95 respirators and could endanger service members, especially in clinical settings. However, one study confirmed that 0.125 inch of facial hair still results in 98% effectiveness in filtering particles for the respirator wearers.28 Although unverified, it is surmisable that 0.25 inch of facial hair will likely not render all respirators useless. However, current Occupational Safety and Health Administration guidelines require fit tests to be conducted only on clean-shaven faces.29 Effectively, service members with facial hair cannot be fit-tested for N95 respirators.

More research is needed to optimize treatment protocols and regulations for PFB in our military. As long as the current grooming standards remain in place, treatment of PFB will be a controversial topic. Guidelines will need to be continuously updated to balance the needs of our service members and to minimize risk to unit safety and mission success. Department of Defense Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1, revised in late 2022, now no longer designates PFB as a condition that disqualifies a candidate from entering service in any military branch.30 The Department of Defense is demonstrating active research and adoption of policies regarding PFB that will benefit our service members.

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB)(also referred to as razor bumps) is a skin disease of the face and neck caused by shaving and remains prevalent in the US Military. As the sharpened ends of curly hair strands penetrate back into the epidermis, they can trigger inflammatory reactions, leading to papules and pustules as well as hyperpigmentation and scarring.1 Although anyone with thick curly hair can develop PFB, Black individuals are disproportionately affected, with 45% to 83% reporting PFB symptoms compared with 18% of White individuals.2 In this article, we review the treatments and current policies on PFB in the military.

Treatment Options

Shaving Guidelines—Daily shaving remains the grooming standard for US service members who are encouraged to follow prescribed grooming techniques to prevent mild cases of PFB, defined as having “few, scattered papules with scant hair growth of the beard area,” according to the technical bulletin of the US Army, which provides the most detailed guidelines among the branches.3 The bulletin recommends hydrating the face with warm water, followed by a preshave lotion and shaving with a single pass superiorly to inferiorly. Following shaving, postrazor hydration lotion is recommended. Single-bladed razors are preferred, as there is less trauma to existing PFB and less potential for hair retraction under the epidermis, though multibladed razors can be used with adequate preshave and postrazor hydration.4 Shaving can be undertaken in the evening to ensure adequate time for preshave preparation and postshave hydration. Waterless shaving uses waterless soaps or lotions containing α-hydroxy acid just prior to shaving in lieu of preshaving and postshaving procedures.4

Topical Medications—For PFB cases that are recalcitrant to management by changes in shaving, topical retinoids are commonly prescribed, as they reduce follicular hyperkeratosis that may lead to PFB.5 The Army medical bulletin recommends a pea-sized amount of tretinoin cream or gel 0.025%, 0.05%, or 0.1% for moderate cases, defined as “heavier beard growth, more scattered papules, no evidence of pustules or denudation.”3 Adapalene cream 0.1% may be used instead of tretinoin for sensitive skin. Oral doxycycline or topical benzoyl peroxide–clindamycin may be added for secondary bacterial skin infections. Clinical trials have demonstrated that combination benzoyl peroxide–clindamycin significantly reduces papules and pustules in up to 63% of patients with PFB (P<.029).6 Azelaic acid can be prescribed for prominent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The bulletin also suggests depilatories such as barium sulfide to obtund the hair ends and make them less likely to re-enter the skin surface, though it notes low compliance rates due to strong sulfur odor, messy application, and irritation and reactions to ingredients in the preparations.4

Shaving Waivers and Laser Hair Removal—The definitive treatment of PFB is to not shave, and a shaving waiver or laser hair removal (LHR) are the best options for severe PFB or PFB refractory to other treatments. A shaving waiver (or shaving profile) allows for growth of up to 0.25 inches of facial hair with maintenance of the length using clippers. The shaving profile typically is issued by the referring primary care manager (PCM) but also can be recommended by a dermatologist. Each military branch implements different regulations on shaving profiles, which complicates care delivery at joint-service military treatment facilities (MTFs). The Table provides guidelines that govern the management of PFB by the US Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps. The issuance and duration of shaving waivers vary by service.

Laser hair removal therapy uses high-wavelength lasers that largely bypass the melanocyte-containing basal layer and selectively target hair follicles located deeper in the skin, which results in precise hair reduction with relative sparing of the epidermis.16 Clinical trials at military clinics have demonstrated that treatments with the 1064-nm long-pulse Nd:YAG laser generally are safe and effective in impeding hair growth in Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI.17 This laser, along with the Alexandrite 755-nm long-pulse laser for Fitzpatrick skin types I to III, is widely available and used for LHR at MTFs that house dermatologists. Eflornithine cream 13.9%, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat hirsutism, can be used as monotherapy for treatment of PFB and has a synergistic depilatory effect in PFB patients when used in conjunction with LHR.18,19 Laser hair removal treatments can induce a permanent change in facial hair density and pattern of growth. Side effects and complications of LHR include discomfort during treatment and, in rare instances, blistering and dyspigmentation of the skin as well as paradoxical hair growth.17

TRICARE, the uniformed health care program, covers LHR in the civilian sector if the following criteria are met: candidates must work in an environment that may require breathing protection, and they must have failed conservative therapy; an MTF dermatologist must evaluate each case and attempt LHR at an MTF to limit outside referrals; and the MTF dermatologist must process each outside referral claim to completion and ensure that the LHR is rendered by a civilian dermatologist and is consistent with branch-specific policies.20

Service Policies on PFB

Army—

The technical bulletin also allows a permanent shaving profile for soldiers who demonstrate a severe adverse reaction to treatment or progression of the disease despite a trial of all these methods.3 The regulation stipulates that 0.125 to 0.25 inches of beard growth usually is sufficient to prevent PFB. Patients on profiles must be re-evaluated by a PCM or a dermatologist at least once a year.3

Air Force—Air Force Instruction 44-102 delegates PFB treatment and management strategies to each individual MTF, which allows for decentralized management of PFB, resulting in treatment protocols that can differ from one MTF to another.7 Since 2020, waivers have been valid for 5 years regardless of deployment or permanent change of station location. Previously, shaving profiles required annual renewals.7 Special duties, such as Honor Guard, Thunderbirds, Special Warfare Mission Support, recruiters, and the Air Force Band, often follow the professional appearance standards more strictly. Until recently, the Honor Guard used to reassign those with long-term medical shaving waivers but now allows airmen with shaving profiles to serve with exceptions (eg, shaving before ceremonies).21

Navy—BUPERS (Bureau of Naval Personnel) Instruction 1000.22C divides PFB severity into 2 categories.8 For mild to moderate PFB cases, topical tretinoin and adapalene are recommended, along with improved shaving hygiene practices. As an alternative to topical steroids, topical eflornithine monotherapy can be used twice daily for 60 days. For moderate to severe PFB cases, continued grooming modifications and LHR at military clinics with dermatologic services are expected.8

Naval administrative memorandum NAVADMIN 064/22 (released in 2022) no longer requires sailors with a shaving “chit,” or shaving waiver, to fully grow out their beards.9 Sailors may now outline or edge their beards as long as doing so does not trigger a skin irritation or outbreak. Furthermore, sailors are no longer required to carry a physical copy of their shaving chit at all times. Laser hair removal for sailors with PFB is now considered optional, whereas sailors with severe PFB were previously expected to receive LHR.9

Marine Corps—The Marine Corps endorses a 4-phase treatment algorithm (Table). As of January 2022, permanent shaving chits are authorized. Marines no longer need to carry physical copies of their chits at all times and cannot be separated from service because of PFB.10 New updates explicitly state that medical officers, not the commanding officers, now have final authority for granting shaving chits.11

Final Thoughts

The Army provides the most detailed bulletin, which defines the clinical features and treatments expected for each stage of PFB. All 4 service branches permit temporary profiles, albeit for different lengths of time. However, only the Army and the Marine Corps currently authorize permanent shaving waivers if all treatments mentioned in their respective bulletins have failed.

The Air Force has adopted the most decentralized approach, in which each MTF is responsible for implementing its own treatment protocols and definitions. Air Force regulations now authorize a 5-year shaving profile for medical reasons, including PFB. The Air Force also has spearheaded efforts to create more inclusive policies. A study of 10,000 active-duty male Air Force members conducted by Air Force physicians found that shaving waivers were associated with longer times to promotion. Although self-identified race was not independently linked to longer promotion times, more Black service members were affected because of a higher prevalence of PFB and shaving profiles.22

The Navy has outlined the most specific timeline for therapy for PFB. The regulations allow a 60-day temporary shaving chit that expires on the day of the appointment with the dermatologist or PCM. Although sailors were previously mandated to fully grow out their beards without modifications during the 60-day shaving chit period, Navy leadership recently overturned these requirements. However, permanent shaving chits are still not authorized in the Navy.

Service members are trying to destigmatize shaving profiles and facial hair in our military. A Facebook group called DoD Beard Action Initiative has more than 17,000 members and was created in 2021 to compile testimonies and data regarding the effects of PFB on airmen.23 Soldiers also have petitioned for growing beards in the garrison environment with more than 100,000 signatures, citing that North Atlantic Treaty Organization allied nations permit beard growth in their respective ranks.24 A Sikh marine captain recently won a lawsuit against the US Department of the Navy to maintain a beard with a turban in uniform on religious grounds.25

The clean-shaven look remains standard across the military, not only for uniformity of appearance but also for safety concerns. The Naval Safety Center’s ALSAFE report concluded that any facial hair impedes a tight fit of gas masks, which can be lethal in chemical warfare. However, the report did not explore how different hair lengths would affect the seal of gas masks.26 It remains unknown how 0.25 inch of facial hair, the maximum hair length authorized for most PFB patients, affects the seal. Department of Defense occupational health researchers currently are assessing how each specific facial hair length diminishes the effectiveness of gas masks.27

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to frequent N95 respirator wear in the military. It is likely that growing a long beard disrupts the fitting of N95 respirators and could endanger service members, especially in clinical settings. However, one study confirmed that 0.125 inch of facial hair still results in 98% effectiveness in filtering particles for the respirator wearers.28 Although unverified, it is surmisable that 0.25 inch of facial hair will likely not render all respirators useless. However, current Occupational Safety and Health Administration guidelines require fit tests to be conducted only on clean-shaven faces.29 Effectively, service members with facial hair cannot be fit-tested for N95 respirators.

More research is needed to optimize treatment protocols and regulations for PFB in our military. As long as the current grooming standards remain in place, treatment of PFB will be a controversial topic. Guidelines will need to be continuously updated to balance the needs of our service members and to minimize risk to unit safety and mission success. Department of Defense Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1, revised in late 2022, now no longer designates PFB as a condition that disqualifies a candidate from entering service in any military branch.30 The Department of Defense is demonstrating active research and adoption of policies regarding PFB that will benefit our service members.

- Perry PK, Cook-Bolden FE, Rahman Z, et al. Defining pseudofolliculitis barbae in 2001: a review of the literature and current trends. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S113-S119.

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38:24-27.

- Department of the Army. TB MED 287. Pseudofolliculitis of the beard and acne keloidalis nuchae. Published December 10, 2014. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/tbmed287.pdf

- Tshudy M, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the U.S. military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:52-57.

- Kligman AM, Mills OH. Pseudofolliculitis of the beard and topically applied tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1973;107:551-552.

- Cook-Bolden FE, Barba A, Halder R, et al. Twice-daily applications of benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel versus vehicle in the treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):18-24.

- US Department of the Air Force. Air Force Instruction 44-102. Medical Care Management. March 17, 2015. Updated July 13, 2022. Accessed October 1, 2022. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_sg/publication/afi44-102/afi44-102.pdf

- Chief of Naval Personnel, Department of the Navy. BUPERS Instruction 1000.22C. Management of Navy Uniformed Personnel Diagnosed With Pseudofolliculitis Barbae. October 8, 2019. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Reference/Instructions/BUPERS/BUPERSINST%201000.22C%20Signed.pdf?ver=iby4-mqcxYCTM1t3AOsqxA%3D%3D

- Chief of Naval Operations, Department of the Navy. NAVADMIN 064/22. BUPERSINST 1000,22C Management of Navy uniformed personnel diagnosed with pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) update. Published March 9, 2022. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Messages/NAVADMIN/NAV2022/NAV22064.txt?ver=bc2HUJnvp6q1y2E5vOSp-g%3D%3D

- Commandant of the Marine Corps, Department of the Navy. Marine Corps Order 6310.1C. Pseudofolliculitis Barbae. October 9, 2012. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/MCO%206310.1C.pdf

- US Marine Corps. Advance Notification of Change to MCO 6310.1C (Pseudofolliculitis Barbae), MCO 1900.16 CH2 (Marine Corps Retirement and Separation Manual), and MCO 1040.31 (Enlisted Retention and Career Development Program). January 21, 2022. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.marines.mil/News/Messages/Messages-Display/Article/2907104/advance-notification-of-change-to-mco-63101c-pseudofolliculitis-barbae-mco-1900

- Department of the Army. Army Regulation 670-1. Uniform and Insignia. Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia. January 26, 2021. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN30302-AR_670-1-000-WEB-1.pdf

- Department of the Air Force. Department of the Air Force Guidance Memorandum to DAFI 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of United States Air Force and United States Space Force Personnel. Published March 31, 2023. Accessed November 20, 2023. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/dafi36-2903/dafi36-2903.pdf

- United States Navy uniform regulations NAVPERS 15665J. MyNavy HR website. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/References/US-Navy-Uniforms/Uniform-Regulations/

- US Marine Corps. Marine Corps Uniform Regulations. Published May 1, 2018. Accessed November 20, 2023. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201020.34H%20v2.pdf?ver=2018-06-26-094038-137

- Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Selective photothermolysis: precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation. Science. 1983;220:524-527.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

- Xia Y, Cho SC, Howard RS, et al. Topical eflornithine hydrochloride improves effectiveness of standard laser hair removal for treating pseudofolliculitis barbae: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:694-699.

- Shokeir H, Samy N, Taymour M. Pseudofolliculitis barbae treatment: efficacy of topical eflornithine, long-pulsed Nd-YAG laser versus their combination. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3517-3525. doi:10.1111/jocd.14027

- TRICARE operations manual 6010.59-M. Supplemental Health Care Program (SHCP)—chapter 17. Contractor responsibilities. Military Health System and Defense Health Agency website. Revised November 5, 2021. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://manuals.health.mil/pages/DisplayManualHtmlFile/2022-08-31/AsOf/TO15/C17S3.html

- Air Force Honor Guard: Recruiting. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.honorguard.af.mil/About-Us/Recruiting/

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247.

- DoD Beard Action Initiative Facebook group. Accessed November 5, 2023. https://www.facebook.com/groups/326068578791063/

- Geske R. Petition gets 95K signatures in push for facial hair for soldiers. KWTX. February 4, 2021. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.kwtx.com/2021/02/04/petition-gets-95k-signatures-in-push-for-facial-hair-for-soldiers/

- Athey P. A Sikh marine is now allowed to wear a turban in uniform. Marine Corps Times. October 5, 2021. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.marinecorpstimes.com/news/your-marine-corps/2021/10/05/a-sikh-marine-is-now-allowed-to-wear-a-turban-in-uniform

- US Department of the Navy. Face Seal Guidance update (ALSAFE 18-008). Naval Safety Center. Published November 18, 2018. Accessed October 22, 2022. https://navalsafetycommand.navy.mil/Portals/29/ALSAFE18-008.pdf

- Garland C. Navy and Marine Corps to study facial hair’s effect on gas masks, lawsuit reveals. Stars and Stripes. January 25, 2022. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.stripes.com/branches/navy/2022-01-25/court-oversee-navy-marine-gas-mask-facial-hair-study-4410015.html

- Floyd EL, Henry JB, Johnson DL. Influence of facial hair length, coarseness, and areal density on seal leakage of a tight-fitting half-face respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;15:334-340.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Occupational Safety and Health Standards 1910.134 App A. Fit Testing Procedures—General Requirements. US Department of Labor. April 23, 1998. Updated August 4, 2004. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.134AppA

- US Department of Defense. DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1. Medical Standards for Military Service: Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction. November 16, 2022. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003_vol1.PDF?ver=7fhqacc0jGX_R9_1iexudA%3D%3D

- Perry PK, Cook-Bolden FE, Rahman Z, et al. Defining pseudofolliculitis barbae in 2001: a review of the literature and current trends. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(2 suppl understanding):S113-S119.

- Gray J, McMichael AJ. Pseudofolliculitis barbae: understanding the condition and the role of facial grooming. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38:24-27.

- Department of the Army. TB MED 287. Pseudofolliculitis of the beard and acne keloidalis nuchae. Published December 10, 2014. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/tbmed287.pdf

- Tshudy M, Cho S. Pseudofolliculitis barbae in the U.S. military, a review. Mil Med. 2021;186:52-57.

- Kligman AM, Mills OH. Pseudofolliculitis of the beard and topically applied tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1973;107:551-552.

- Cook-Bolden FE, Barba A, Halder R, et al. Twice-daily applications of benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% gel versus vehicle in the treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):18-24.

- US Department of the Air Force. Air Force Instruction 44-102. Medical Care Management. March 17, 2015. Updated July 13, 2022. Accessed October 1, 2022. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_sg/publication/afi44-102/afi44-102.pdf

- Chief of Naval Personnel, Department of the Navy. BUPERS Instruction 1000.22C. Management of Navy Uniformed Personnel Diagnosed With Pseudofolliculitis Barbae. October 8, 2019. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Reference/Instructions/BUPERS/BUPERSINST%201000.22C%20Signed.pdf?ver=iby4-mqcxYCTM1t3AOsqxA%3D%3D

- Chief of Naval Operations, Department of the Navy. NAVADMIN 064/22. BUPERSINST 1000,22C Management of Navy uniformed personnel diagnosed with pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) update. Published March 9, 2022. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/Portals/55/Messages/NAVADMIN/NAV2022/NAV22064.txt?ver=bc2HUJnvp6q1y2E5vOSp-g%3D%3D

- Commandant of the Marine Corps, Department of the Navy. Marine Corps Order 6310.1C. Pseudofolliculitis Barbae. October 9, 2012. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/MCO%206310.1C.pdf

- US Marine Corps. Advance Notification of Change to MCO 6310.1C (Pseudofolliculitis Barbae), MCO 1900.16 CH2 (Marine Corps Retirement and Separation Manual), and MCO 1040.31 (Enlisted Retention and Career Development Program). January 21, 2022. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.marines.mil/News/Messages/Messages-Display/Article/2907104/advance-notification-of-change-to-mco-63101c-pseudofolliculitis-barbae-mco-1900

- Department of the Army. Army Regulation 670-1. Uniform and Insignia. Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia. January 26, 2021. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN30302-AR_670-1-000-WEB-1.pdf

- Department of the Air Force. Department of the Air Force Guidance Memorandum to DAFI 36-2903, Dress and Personal Appearance of United States Air Force and United States Space Force Personnel. Published March 31, 2023. Accessed November 20, 2023. https://static.e-publishing.af.mil/production/1/af_a1/publication/dafi36-2903/dafi36-2903.pdf

- United States Navy uniform regulations NAVPERS 15665J. MyNavy HR website. Accessed November 19, 2023. https://www.mynavyhr.navy.mil/References/US-Navy-Uniforms/Uniform-Regulations/

- US Marine Corps. Marine Corps Uniform Regulations. Published May 1, 2018. Accessed November 20, 2023. https://www.marines.mil/portals/1/Publications/MCO%201020.34H%20v2.pdf?ver=2018-06-26-094038-137

- Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Selective photothermolysis: precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation. Science. 1983;220:524-527.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

- Xia Y, Cho SC, Howard RS, et al. Topical eflornithine hydrochloride improves effectiveness of standard laser hair removal for treating pseudofolliculitis barbae: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:694-699.

- Shokeir H, Samy N, Taymour M. Pseudofolliculitis barbae treatment: efficacy of topical eflornithine, long-pulsed Nd-YAG laser versus their combination. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3517-3525. doi:10.1111/jocd.14027

- TRICARE operations manual 6010.59-M. Supplemental Health Care Program (SHCP)—chapter 17. Contractor responsibilities. Military Health System and Defense Health Agency website. Revised November 5, 2021. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://manuals.health.mil/pages/DisplayManualHtmlFile/2022-08-31/AsOf/TO15/C17S3.html

- Air Force Honor Guard: Recruiting. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.honorguard.af.mil/About-Us/Recruiting/

- Ritchie S, Park J, Banta J, et al. Shaving waivers in the United States Air Force and their impact on promotions of Black/African-American members. Mil Med. 2023;188:E242-E247.

- DoD Beard Action Initiative Facebook group. Accessed November 5, 2023. https://www.facebook.com/groups/326068578791063/

- Geske R. Petition gets 95K signatures in push for facial hair for soldiers. KWTX. February 4, 2021. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.kwtx.com/2021/02/04/petition-gets-95k-signatures-in-push-for-facial-hair-for-soldiers/

- Athey P. A Sikh marine is now allowed to wear a turban in uniform. Marine Corps Times. October 5, 2021. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.marinecorpstimes.com/news/your-marine-corps/2021/10/05/a-sikh-marine-is-now-allowed-to-wear-a-turban-in-uniform

- US Department of the Navy. Face Seal Guidance update (ALSAFE 18-008). Naval Safety Center. Published November 18, 2018. Accessed October 22, 2022. https://navalsafetycommand.navy.mil/Portals/29/ALSAFE18-008.pdf

- Garland C. Navy and Marine Corps to study facial hair’s effect on gas masks, lawsuit reveals. Stars and Stripes. January 25, 2022. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.stripes.com/branches/navy/2022-01-25/court-oversee-navy-marine-gas-mask-facial-hair-study-4410015.html

- Floyd EL, Henry JB, Johnson DL. Influence of facial hair length, coarseness, and areal density on seal leakage of a tight-fitting half-face respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;15:334-340.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Occupational Safety and Health Standards 1910.134 App A. Fit Testing Procedures—General Requirements. US Department of Labor. April 23, 1998. Updated August 4, 2004. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.134AppA

- US Department of Defense. DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1. Medical Standards for Military Service: Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction. November 16, 2022. Accessed November 16, 2023. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003_vol1.PDF?ver=7fhqacc0jGX_R9_1iexudA%3D%3D

Practice Points

- Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB) is common among US service members due to grooming standards in the military.

- Each military branch follows separate yet related guidelines to treat PFB.

- The best treatment for severe or refractory cases of PFB is a long-term shaving restriction or laser hair removal.

Developing and Measuring Effectiveness of a Distance Learning Dermatology Course: A Prospective Observational Study

Medical education has seen major changes over the last decade. The allotted time for preclinical education has decreased from 24 months to 18 months or less at most institutions, with an increased focus on content associated with health care delivery and health system science.1,2 Many schools now include at least some blended learning with online delivery of preclinical education.3 On the other hand, the clinical portion of medical education has remained largely unchanged prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the apprenticeship framework allowing the experienced physician to observe, mentor, and pass on practical knowledge so that the apprentice can one day gain independence after demonstrating adequate proficiency.4

With respect to dermatology education, skin disorders are in the top 5 reported reasons for visits to primary care5; however, a 2009 survey found that only 0.24% to 0.30% of medical schools’ curricula are spent on dermatology.6 Moreover, one institution found that fourth-year medical students received an average of 46.6% on a 15-item quiz designed to assess the ability to diagnose and treat common dermatologic conditions, and within that same cohort, 87.6% of students felt that they received inadequate training in dermatology during medical school.7

COVID-19 caused an unprecedented paradigm shift when medical schools throughout the country, including our own, canceled clinical rotations at the end of March 2020 to protect students and control the spread of infection. To enable clinical and preclinical learning to continue, institutions around the globe turned to either online learning or participation in telehealth as a substitute for clinical rotations.8-10 At the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (Bethesda, Maryland), one of the many online clinical courses offered included a distance learning (DL) dermatology course. Herein, we describe the results of a prospective study evaluating short-term information recall and comprehension as well as students’ confidence in their ability to apply course objectives over 3 months of an online DL dermatology course.

Methods

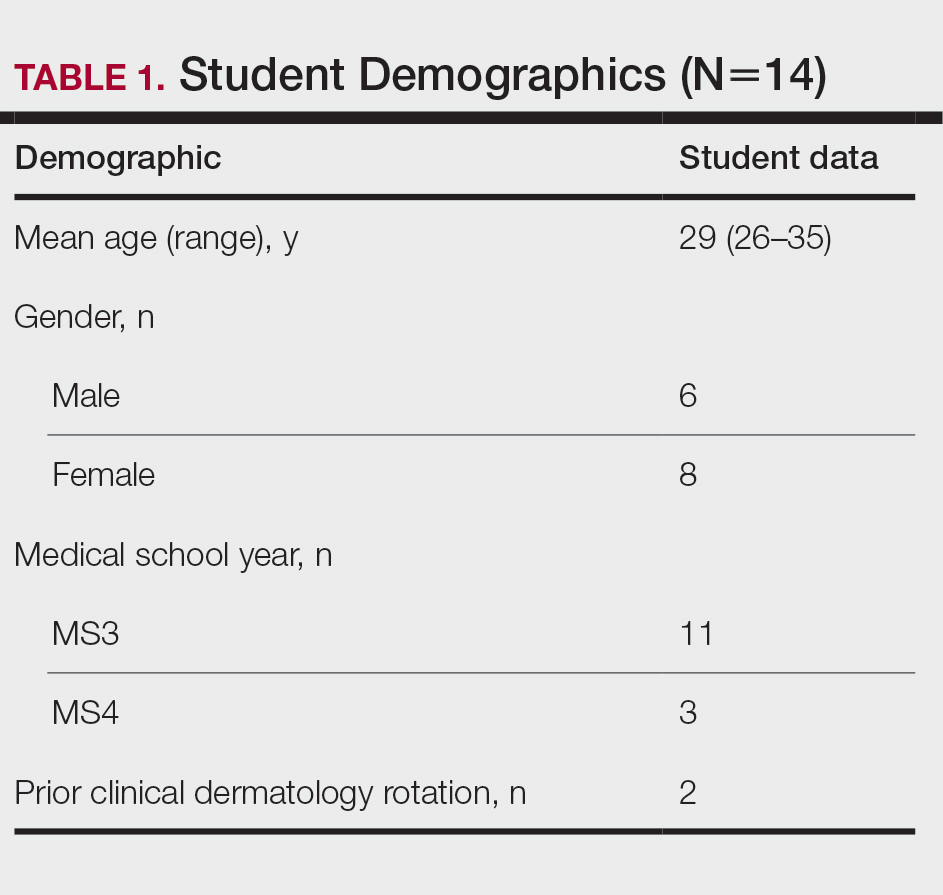

Between April and July 2020, 14 students at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (Table 1) enrolled in 1 of 3 four-week DL dermatology classes. The students independently completed the Basic Dermatology Curriculum, a set of online modules with demonstrated efficacy from the American Academy of Dermatology, over 4 weeks.11 Additionally, students were instructed to review an hour of clinical dermatology images daily from online dermatology atlases and e-books accessed through our medical school’s virtual library. Optional Free Open Access Meducation resources also were provided. The course syllabus provided the students with clear expectations, links to the resources, and a recommended daily schedule.

An online video conferencing platform was utilized for an orientation session and 4 subsequent weekly 1.5-hour virtual meetings. The weekly DL meetings focused on a discussion of clinical images pertinent to the American Academy of Dermatology modules covered for the week. These interactive analytic sessions were referred to as Clinpic sessions. With instructor guidance, the students learned to describe images, and they provided differential diagnoses, workup, and treatments for various skin diseases. The virtual meetings included supplemental lectures detailing the use of teledermatology and laser therapy in the Military Health System and a journal review on the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19.

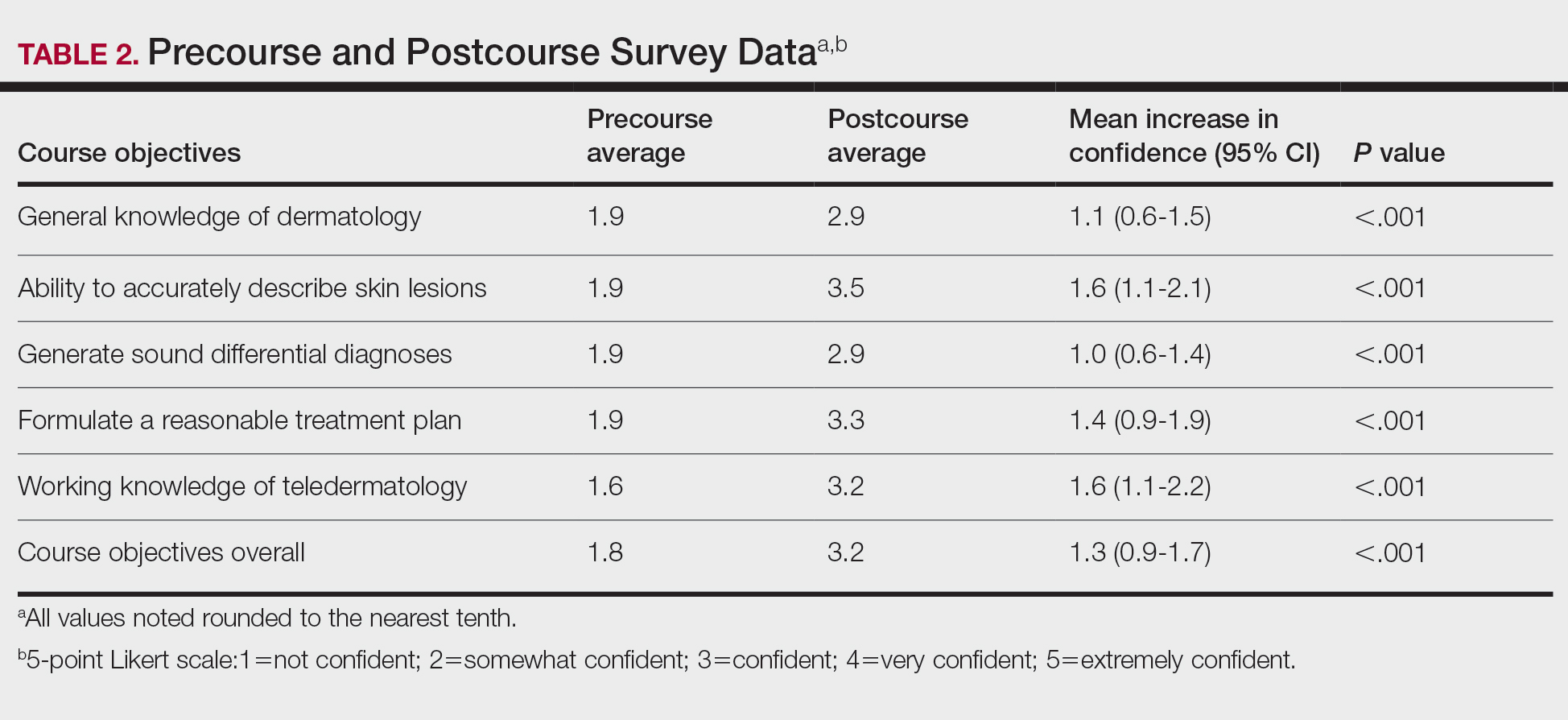

A 40-question, image-based pretest and posttest utilized during clinical rotations evaluated knowledge recall and comprehension. A precourse and postcourse survey using a 5-point Likert scale (1=not confident; 5=extremely confident) assessed students’ confidence levels across course objectives: general knowledge of dermatology, working knowledge of teledermatology, ability to accurately describe skin lesions, generate sound differential diagnoses, and formulate a reasonable treatment plan. Statistical analysis was performed using free online statistical software at statskingdom.com.12

Results

All 14 student enrollees completed the precourse and postcourse tests and surveys. Pretest and posttest scores followed a normal distribution and therefore met criteria for utilization of a parametric test. The precourse test average of 67% (range, 40%–90%) improved to 84% postcourse (range, 70%–98%; P<.001; 95% CI, 11-23 by paired t test). Not surprisingly, the 2 students who had completed a dermatology rotation had higher average pretest and posttest scores (pretest, 87%; posttest, 94%). Students’ confidence with the course objectives were mostly at the somewhat confident level on the 5-point Likert scale precourse survey. By the end of the course, student survey responses increased to confident and very confident levels, corresponding to an overall improvement of 1.3 points (P<.001 by paired t test)(Table 2) when the mean of the survey results was aggregated across every question. Instructor evaluation of student performance mirrored student assessments.

Comment

The DL dermatology course succeeded in helping the enrolled students attain course objectives and offered a reasonable solution when in-person interaction was restricted. The students in the DL course made notable improvements in their dermatology knowledge and improved their communication, diagnosis, and management skills. Although a blended dermatology curriculum with e-learning combined with clinical experience has been shown to increase knowledge acquisition,13,14 our results suggest that an online-only program also can increase comprehension as well as students’ confidence in their abilities.

A major challenge for the DL course was the lack of opportunity to perform common dermatology procedures. The addition of a hands-on skin procedure module would have been a great supplement to the course but was not possible due to social distancing guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic. The small sample size and voluntary enrollment were limitations to this study.

Conclusion

Although the traditional dermatology rotation remains the gold standard for clinical instruction, a well-organized DL teaching environment allowed for a more controlled learning experience with a broader coverage of topics to include potentially greater exposure to rare skin disorders not typically encountered in everyday practice. A DL dermatology course may serve as an enduring curriculum for those who wish to learn dermatology more broadly and are not interested in performing skin procedures or direct patient exposure (eg, those pursuing non–primary care specialties, pathology, or radiology). It also may be attractive to students who have had a prior clinical dermatology rotation and desire a different learning experience with a wide coverage of topics.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank Thomas Darling, MD, PhD (Bethesda, Maryland), for coining the term Clinpic and providing critical feedback throughout the course. The authors also thank Sorana Raiciulescu, MS (Bethesda, Maryland), for assistance with the statistical analysis.

- Emanuel EJ. The inevitable reimagining of medical education. JAMA. 2020;323:1127-1128.

- Skochelak SE, Stack SJ. Creating the medical schools of the future. Acad Med. 2017;92:16-19.

- Vallée A, Blacher J, Cariou A, et al. Blended learning compared to traditional learning in medical education: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:E16504.

- Rangachari D, Brown LE, Kern DE, et al. Clinical coaching: evolving the apprenticeship model for modern housestaff. Med Teach. 2017;39:780-782.

- Finley CR, Chan DS, Garrison S, et al. What are the most common conditions in primary care? Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:832-840.

- McCleskey PE, Gilson RT, DeVillez RL. Medical student core curriculum in dermatology survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:30-35.e4.

- Ulman CA, Binder SB, Borges NJ. Assessment of medical students’ proficiency in dermatology: are medical students adequately prepared to diagnose and treat common dermatologic conditions in the United States? J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:18.

- Loh TY, Hsiao JL, Shi VY. COVID-19 and its effect on medical student education in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E163-E164.

- Hilburg R, Patel N, Ambruso S, et al. Medical education during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: learning from a distance. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020;27:412-417.

- Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:2131-2132.

- McCleskey PE. Clinic teaching made easy: a prospective study of the American Academy of Dermatology core curriculum in primary care learners. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:273-279.e1.

- Paired T Test calculator. Statistics Kingdom website. Accessed February 7, 2022. http://www.statskingdom.com/160MeanT2pair.html

- Fransen F, Martens H, Nagtzaam I, et al. Use of e-learning in clinical clerkships: effects on acquisition of dermatological knowledge and learning processes. Int J Med Educ. 2018;9:11-17.

- Silva CS, Souza MB, Silva Filho RS, et al. E-learning program for medical students in dermatology. Clinics. 2011;66:619-622.

Medical education has seen major changes over the last decade. The allotted time for preclinical education has decreased from 24 months to 18 months or less at most institutions, with an increased focus on content associated with health care delivery and health system science.1,2 Many schools now include at least some blended learning with online delivery of preclinical education.3 On the other hand, the clinical portion of medical education has remained largely unchanged prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the apprenticeship framework allowing the experienced physician to observe, mentor, and pass on practical knowledge so that the apprentice can one day gain independence after demonstrating adequate proficiency.4

With respect to dermatology education, skin disorders are in the top 5 reported reasons for visits to primary care5; however, a 2009 survey found that only 0.24% to 0.30% of medical schools’ curricula are spent on dermatology.6 Moreover, one institution found that fourth-year medical students received an average of 46.6% on a 15-item quiz designed to assess the ability to diagnose and treat common dermatologic conditions, and within that same cohort, 87.6% of students felt that they received inadequate training in dermatology during medical school.7

COVID-19 caused an unprecedented paradigm shift when medical schools throughout the country, including our own, canceled clinical rotations at the end of March 2020 to protect students and control the spread of infection. To enable clinical and preclinical learning to continue, institutions around the globe turned to either online learning or participation in telehealth as a substitute for clinical rotations.8-10 At the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (Bethesda, Maryland), one of the many online clinical courses offered included a distance learning (DL) dermatology course. Herein, we describe the results of a prospective study evaluating short-term information recall and comprehension as well as students’ confidence in their ability to apply course objectives over 3 months of an online DL dermatology course.

Methods

Between April and July 2020, 14 students at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (Table 1) enrolled in 1 of 3 four-week DL dermatology classes. The students independently completed the Basic Dermatology Curriculum, a set of online modules with demonstrated efficacy from the American Academy of Dermatology, over 4 weeks.11 Additionally, students were instructed to review an hour of clinical dermatology images daily from online dermatology atlases and e-books accessed through our medical school’s virtual library. Optional Free Open Access Meducation resources also were provided. The course syllabus provided the students with clear expectations, links to the resources, and a recommended daily schedule.

An online video conferencing platform was utilized for an orientation session and 4 subsequent weekly 1.5-hour virtual meetings. The weekly DL meetings focused on a discussion of clinical images pertinent to the American Academy of Dermatology modules covered for the week. These interactive analytic sessions were referred to as Clinpic sessions. With instructor guidance, the students learned to describe images, and they provided differential diagnoses, workup, and treatments for various skin diseases. The virtual meetings included supplemental lectures detailing the use of teledermatology and laser therapy in the Military Health System and a journal review on the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19.

A 40-question, image-based pretest and posttest utilized during clinical rotations evaluated knowledge recall and comprehension. A precourse and postcourse survey using a 5-point Likert scale (1=not confident; 5=extremely confident) assessed students’ confidence levels across course objectives: general knowledge of dermatology, working knowledge of teledermatology, ability to accurately describe skin lesions, generate sound differential diagnoses, and formulate a reasonable treatment plan. Statistical analysis was performed using free online statistical software at statskingdom.com.12

Results

All 14 student enrollees completed the precourse and postcourse tests and surveys. Pretest and posttest scores followed a normal distribution and therefore met criteria for utilization of a parametric test. The precourse test average of 67% (range, 40%–90%) improved to 84% postcourse (range, 70%–98%; P<.001; 95% CI, 11-23 by paired t test). Not surprisingly, the 2 students who had completed a dermatology rotation had higher average pretest and posttest scores (pretest, 87%; posttest, 94%). Students’ confidence with the course objectives were mostly at the somewhat confident level on the 5-point Likert scale precourse survey. By the end of the course, student survey responses increased to confident and very confident levels, corresponding to an overall improvement of 1.3 points (P<.001 by paired t test)(Table 2) when the mean of the survey results was aggregated across every question. Instructor evaluation of student performance mirrored student assessments.

Comment

The DL dermatology course succeeded in helping the enrolled students attain course objectives and offered a reasonable solution when in-person interaction was restricted. The students in the DL course made notable improvements in their dermatology knowledge and improved their communication, diagnosis, and management skills. Although a blended dermatology curriculum with e-learning combined with clinical experience has been shown to increase knowledge acquisition,13,14 our results suggest that an online-only program also can increase comprehension as well as students’ confidence in their abilities.

A major challenge for the DL course was the lack of opportunity to perform common dermatology procedures. The addition of a hands-on skin procedure module would have been a great supplement to the course but was not possible due to social distancing guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic. The small sample size and voluntary enrollment were limitations to this study.

Conclusion

Although the traditional dermatology rotation remains the gold standard for clinical instruction, a well-organized DL teaching environment allowed for a more controlled learning experience with a broader coverage of topics to include potentially greater exposure to rare skin disorders not typically encountered in everyday practice. A DL dermatology course may serve as an enduring curriculum for those who wish to learn dermatology more broadly and are not interested in performing skin procedures or direct patient exposure (eg, those pursuing non–primary care specialties, pathology, or radiology). It also may be attractive to students who have had a prior clinical dermatology rotation and desire a different learning experience with a wide coverage of topics.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank Thomas Darling, MD, PhD (Bethesda, Maryland), for coining the term Clinpic and providing critical feedback throughout the course. The authors also thank Sorana Raiciulescu, MS (Bethesda, Maryland), for assistance with the statistical analysis.

Medical education has seen major changes over the last decade. The allotted time for preclinical education has decreased from 24 months to 18 months or less at most institutions, with an increased focus on content associated with health care delivery and health system science.1,2 Many schools now include at least some blended learning with online delivery of preclinical education.3 On the other hand, the clinical portion of medical education has remained largely unchanged prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the apprenticeship framework allowing the experienced physician to observe, mentor, and pass on practical knowledge so that the apprentice can one day gain independence after demonstrating adequate proficiency.4

With respect to dermatology education, skin disorders are in the top 5 reported reasons for visits to primary care5; however, a 2009 survey found that only 0.24% to 0.30% of medical schools’ curricula are spent on dermatology.6 Moreover, one institution found that fourth-year medical students received an average of 46.6% on a 15-item quiz designed to assess the ability to diagnose and treat common dermatologic conditions, and within that same cohort, 87.6% of students felt that they received inadequate training in dermatology during medical school.7

COVID-19 caused an unprecedented paradigm shift when medical schools throughout the country, including our own, canceled clinical rotations at the end of March 2020 to protect students and control the spread of infection. To enable clinical and preclinical learning to continue, institutions around the globe turned to either online learning or participation in telehealth as a substitute for clinical rotations.8-10 At the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (Bethesda, Maryland), one of the many online clinical courses offered included a distance learning (DL) dermatology course. Herein, we describe the results of a prospective study evaluating short-term information recall and comprehension as well as students’ confidence in their ability to apply course objectives over 3 months of an online DL dermatology course.

Methods

Between April and July 2020, 14 students at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (Table 1) enrolled in 1 of 3 four-week DL dermatology classes. The students independently completed the Basic Dermatology Curriculum, a set of online modules with demonstrated efficacy from the American Academy of Dermatology, over 4 weeks.11 Additionally, students were instructed to review an hour of clinical dermatology images daily from online dermatology atlases and e-books accessed through our medical school’s virtual library. Optional Free Open Access Meducation resources also were provided. The course syllabus provided the students with clear expectations, links to the resources, and a recommended daily schedule.

An online video conferencing platform was utilized for an orientation session and 4 subsequent weekly 1.5-hour virtual meetings. The weekly DL meetings focused on a discussion of clinical images pertinent to the American Academy of Dermatology modules covered for the week. These interactive analytic sessions were referred to as Clinpic sessions. With instructor guidance, the students learned to describe images, and they provided differential diagnoses, workup, and treatments for various skin diseases. The virtual meetings included supplemental lectures detailing the use of teledermatology and laser therapy in the Military Health System and a journal review on the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19.

A 40-question, image-based pretest and posttest utilized during clinical rotations evaluated knowledge recall and comprehension. A precourse and postcourse survey using a 5-point Likert scale (1=not confident; 5=extremely confident) assessed students’ confidence levels across course objectives: general knowledge of dermatology, working knowledge of teledermatology, ability to accurately describe skin lesions, generate sound differential diagnoses, and formulate a reasonable treatment plan. Statistical analysis was performed using free online statistical software at statskingdom.com.12

Results