User login

The Dermatologist’s Role in Amputee Skin Care

Limb amputation is a major life-changing event that markedly affects a patient’s quality of life as well as his/her ability to participate in activities of daily living. The most prevalent causes for amputation include vascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, trauma, and cancer, respectively.1,2 For amputees, maintaining prosthetic use is a major physical and psychological undertaking that benefits from a multidisciplinary team approach. Although individuals with lower limb amputations are disproportionately impacted by skin disease due to the increased mechanical forces exerted over the lower limbs, patients with upper limb amputations also develop dermatologic conditions secondary to wearing prostheses.

Approximately 185,000 amputations occur each year in the United States.3 Although amputations resulting from peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus tend to occur in older individuals, amputations in younger patients usually occur from trauma.2 The US military has experienced increasing numbers of amputations from trauma due to the ongoing combat operations in the Middle East. Although improvements in body armor and tactical combat casualty care have reduced the number of preventable deaths, the number of casualties surviving with extremity injuries requiring amputation has increased.4,5 As of October 2017, 1705 US servicemembers underwent major limb amputations, with 1914 lower limb amputations and 302 upper limb amputations. These amputations mainly impacted men aged 21 to 29 years, but female servicemembers also were affected, and a small group of servicemembers had multiple amputations.6

One of the most common medical problems that amputees face during long-term care is skin disease, with approximately 75% of amputees using a lower limb prosthesis experiencing skin problems. In general, amputees experience nearly 65% more dermatologic concerns than the general population.7 In one study of 97 individuals with transfemoral amputations, some of the most common issues associated with socket prosthetics included heat and sweating in the prosthetic socket (72%) as well as sores and skin irritation from the socket (62%).8 Given the high incidence of skin disease on residual limbs, dermatologists are uniquely positioned to keep the amputee in his/her prosthesis and prevent prosthetic abandonment.

Complications Following Amputation

Although US military servicemembers who undergo amputations receive the very best prosthetic devices and rehabilitation resources, they still experience prosthesis abandonment.9 Despite the fact that prosthetic limbs and prosthesis technology have substantially improved over the last 2 decades, one study indicated that the high frequency of problems affecting tissue viability at residual limbs is due to the age-old problem of prosthetic fit.10 In patients with the most advanced prostheses, poor fit still results in mechanical damage to the skin, as the residual limb is exposed to unequal and shearing forces across the amputation site as well as high pressures that cause a vaso-occlusive effect.11,12 Issues with poor fit are especially important for more active patients, as they normally want to immediately return to their vigorous preinjury lifestyles. In these patients, even a properly fitting prosthetic may not be able to overcome the fact that the residual limb skin is not well suited for the mechanical forces generated by the prosthesis and the humid environment of the socket.1,13 Another complicating factor is the dynamic nature of the residual limb. Muscle atrophy, changes in gait, and weight gain or loss can lead to an ill-fitting prosthetic and subsequent skin breakdown.

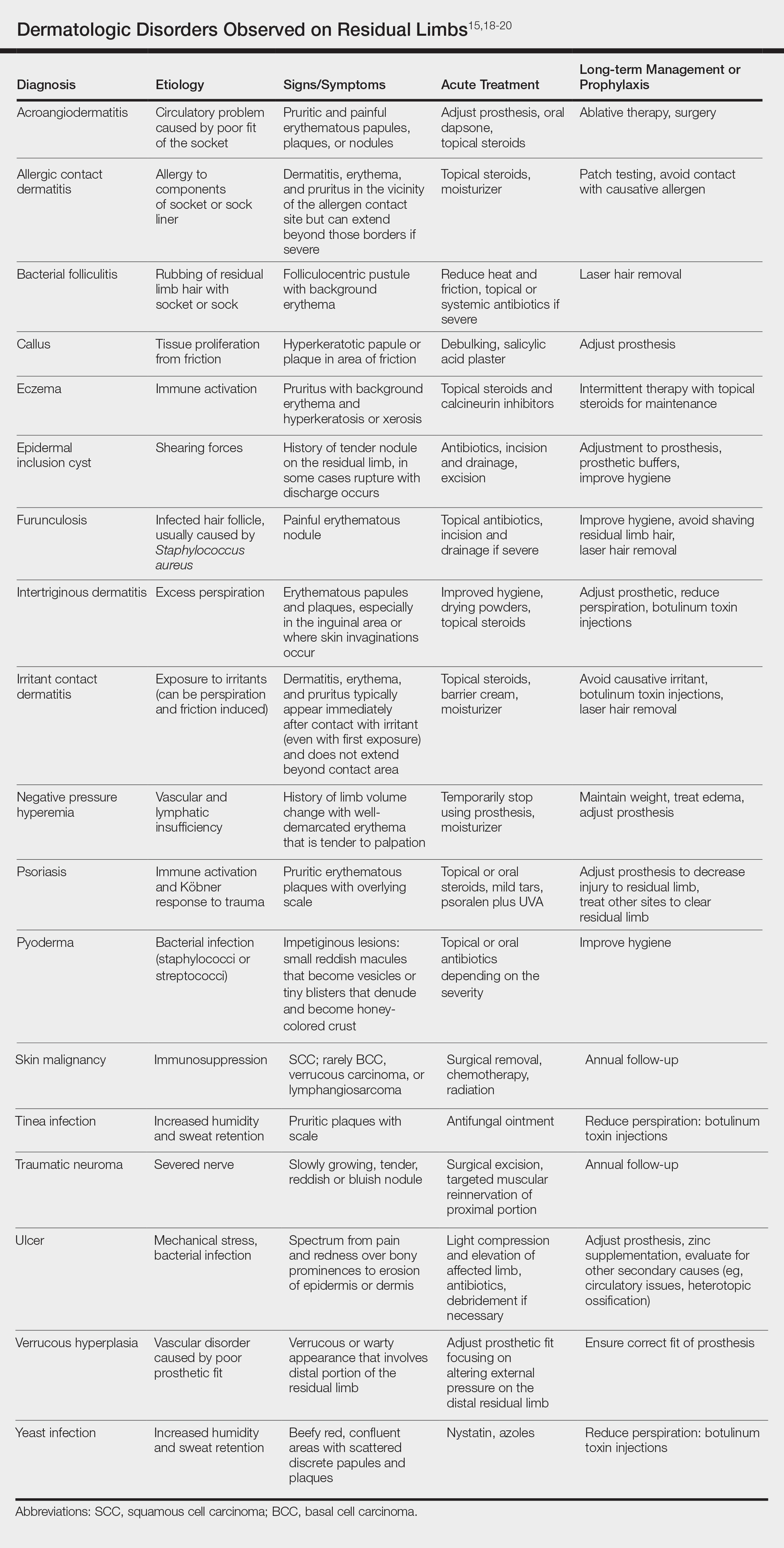

There are many case reports and review articles describing the skin problems in amputees.1,14-17 The Table summarizes these conditions and outlines treatment options for each.15,18-20

Most skin diseases on residual limbs are the result of mechanical skin breakdown, inflammation, infection, or combinations of these processes. Overall, amputees with diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease tend to have skin disease related to poor perfusion, whereas amputees who are active and healthy tend to have conditions related to mechanical stress.7,13,14,17,21,22 Bui et al17 reported ulcers, abscesses, and blisters as the most common skin conditions that occur at the site of residual limbs; however, other less common dermatologic disorders such as skin malignancies, verrucous hyperplasia and carcinoma, granulomatous cutaneous lesions, acroangiodermatitis, and bullous pemphigoid also are seen.23-26 Buikema and Meyerle15 hypothesize that these conditions, as well as the more common skin diseases, are partly from the amputation disrupting blood and lymphatic flow in the residual limb, which causes the site to act as an immunocompromised district that induces dysregulation of neuroimmune regulators.

It is important to note that skin disease on residual limbs is not just an acute problem. Long-term follow-up of 247 traumatic amputees from the Vietnam War showed that almost half of prosthesis users (48.2%) reported a skin problem in the preceding year, more than 38 years after the amputation. Additionally, one-quarter of these individuals experienced skin problems approximately 50% of the time, which unfortunately led to limited use or total abandonment of the prosthesis for the preceding year in 56% of the veterans surveyed.21

Other complications following amputation indirectly lead to skin problems. Heterotopic ossification, or the formation of bone at extraskeletal sites, has been observed in up to 65% of military amputees from recent operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.27,28 If symptomatic, heterotopic ossification can lead to poor prosthetic fit and subsequent skin breakdown. As a result, it has been reported that up to 40% of combat-related lower extremity amputations may require excision of heterotopic ossificiation.29

Amputation also can result in psychologic concerns that indirectly affect skin health. A systematic review by Mckechnie and John30 suggested that despite heterogeneity between studies, even using the lowest figures demonstrated the significance anxiety and depression play in the lives of traumatic amputees. If left untreated, these mental health issues can lead to poor residual limb hygiene and prosthetic maintenance due to reductions in the patient’s energy and motivation. Studies have shown that proper hygiene of residual limbs and silicone liners reduces associated skin problems.19,31

Role of the Dermatologist

Routine care and conservative management of amputee skin problems often are accomplished by prosthetists, primary care physicians, nurses, and physical therapists. In one study, more than 80% of the most common skin problems affecting amputees could be attributed to the prosthesis itself, which highlights the importance of the continued involvement of the prosthetist beyond the initial fitting period.13 However, when a skin problem becomes refractory to conservative management, referral to a dermatologist is prudent; therefore, the dermatologist is an integral member of the multidisciplinary team that provides care for amputees.

The dermatologist often is best positioned to diagnose skin diseases that result from wearing prostheses and is well versed in treatments for short-term and long-term management of skin disease on residual limbs. The dermatologist also can offer prophylactic treatments to decrease sweating and hair growth to prevent potential infections and subsequent skin breakdown. Additionally, proper education on self-care has been shown to decrease the amount of skin problems and increase functional status and quality of life for amputees.32,33 Dermatologists can assist with the patient education process as well as refer amputees to a useful resource from the Amputee Coalition website (www.amputee-coalition.org) to provide specific patient education on how to maintain skin on the residual limb to prevent skin disease.

Current Treatments and Future Directions

Skin disorders affecting residual limbs usually are conditions that dermatologists commonly encounter and are comfortable managing in general practice. Additionally, dermatologists routinely treat hyperhidrosis and conduct laser hair removal, both of which are effective prophylactic adjuncts for amputee skin health. There are a few treatments for reducing residual limb hyperhidrosis that are particularly useful. Although first-line treatment of residual limb hyperhidrosis often is topical aluminum chloride, it requires frequent application and often causes considerable skin irritation when applied to residual limbs. Alternatively, intradermal botulinum toxin has been shown to successfully reduce sweat production in individuals with residual limb hyperhidrosis and is well tolerated.34 A 2017 case report discussed the use of microwave thermal ablation of eccrine coils using a noninvasive 3-step hyperhidrosis treatment system on a bilateral below-the-knee amputee. The authors reported the patient tolerated the procedure well with decreased dermatitis and folliculitis, leading to his ability to wear a prosthetic for longer periods of time.35

Ablative fractional resurfacing with a CO2 laser is another key treatment modality central to amputees, more specifically to traumatic amputees. A CO2 laser can decrease skin tension and increase skin mobility associated with traumatic scars as well as decrease skin vulnerability to biofilms present in chronic wounds on residual limbs. It is believed that the pattern of injury caused by ablative fractional lasers disrupts biofilms and stimulates growth factor secretion and collagen remodeling through the concept of photomicrodebridement.36 The ablative fractional resurfacing approach to scar therapy and chronic wound debridement can result in less skin injury, allowing the amputee to continue rehabilitation and return more quickly to prosthetic use.37

One interesting area of research in amputee care involves the study of novel ways to increase the skin’s ability to adapt to mechanical stress and load bearing and accelerate wound healing on the residual limb. Multiple studies have identified collagen fibril enlargement as an important component of skin adaptation, and biomolecules such as decorin may enhance this process.38-40 The concept of increasing these biomolecules at the correct time during wound healing to strengthen the residual limb tissue currently is being studied.39

Another encouraging area of research is the involvement of fibroblasts in cutaneous wound healing and their role in determining the phenotype of residual limb skin in amputees. The clinical application of autologous fibroblasts is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for cosmetic use as a filler material and currently is under research for other applications, such as skin regeneration after surgery or manipulating skin characteristics to enhance the durability of residual limbs.41

Future preventative care of amputee skin may rely on tracking residual limb health before severe tissue injury occurs. For instance, Rink et al42 described an approach to monitor residual limb health using noninvasive imaging (eg, hyperspectral imaging, laser speckle imaging) and noninvasive probes that measure oxygenation, perfusion, skin barrier function, and skin hydration to the residual limb. Although these limb surveillance sensors would be employed by prosthetists, the dermatologist, as part of the multispecialty team, also could leverage the data for diagnosis and treatment considerations.

Final Thoughts

The dermatologist is an important member of the multidisciplinary team involved in the care of amputees. Skin disease is prevalent in amputees throughout their lives and often leads to abandonment of prostheses. Although current therapies and preventative treatments are for the most part successful, future research involving advanced technology to monitor skin health, increasing residual limb skin durability at the molecular level, and targeted laser therapies are promising. Through engagement and effective collaboration with the entire multidisciplinary team, dermatologists will have a considerable impact on amputee skin health.

- Dudek NL, Marks MB, Marshall SC, et al. Dermatologic conditions associated with use of a lower-extremity prosthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:659-663.

- Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, et al. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:422-429.

- Kozak LJ. Ambulatory and Inpatient Procedures in the United States, 1995. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1998.

- Epstein RA, Heinemann AW, McFarland LV. Quality of life for veterans and servicemembers with major traumatic limb loss from Vietnam and OIF/OEF conflicts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47:373-385.

- Dougherty AL, Mohrle CR, Galarneau MR, et al. Battlefield extremity injuries in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Injury. 2009;40:772-777.

- Farrokhi S, Perez K, Eskridge S, et al. Major deployment-related amputations of lower and upper limbs, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2017. MSMR. 2018;25:10-16.

- Highsmith MJ, Highsmith JT. Identifying and managing skin issues with lower-limb prosthetic use. Amputee Coalition website. https://www.amputee-coalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/.../skin_issues_lower.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2019.

- Hagberg K, Brånemark R. Consequences of non-vascular trans-femoral amputation: a survey of quality of life, prosthetic use and problems. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2001;25:186-194.

- Gajewski D, Granville R. The United States Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(10 spec no):S183-S187.

- Butler K, Bowen C, Hughes AM, et al. A systematic review of the key factors affecting tissue viability and rehabilitation outcomes of the residual limb in lower extremity traumatic amputees. J Tissue Viability. 2014;23:81-93.

- Mak AF, Zhang M, Boone DA. State-of-the-art research in lower-limb prosthetic biomechanics-socket interface: a review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001;38:161-174.

- Silver-Thorn MB, Steege JW. A review of prosthetic interface stress investigations. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1996;33:253-266.

- Dudek NL, Marks MB, Marshall SC. Skin problems in an amputee clinic. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85:424-429.

- Meulenbelt HE, Geertzen JH, Dijkstra PU, et al. Skin problems in lower limb amputees: an overview by case reports. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:147-155.

- Buikema KE, Meyerle JH. Amputation stump: privileged harbor for infections, tumors, and immune disorders. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:670-677.

- Highsmith JT, Highsmith MJ. Common skin pathology in LE prosthesis users. JAAPA. 2007;20:33-36, 47.

- Bui KM, Raugi GJ, Nguyen VQ, et al. Skin problems in individuals with lower-limb loss: literature review and proposed classification system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:1085-1090.

- Levy SW. Skin Problems of the Amputee. St. Louis, MO: Warren H. Green Inc; 1983.

- Levy SW, Allende MF, Barnes GH. Skin problems of the leg amputee. Arch Dermatol. 1962;85:65-81.

- Dumanian GA, Potter BK, Mioton LM, et al. Targeted muscle reinnervation treats neuroma and phantom pain in major limb amputees: a randomized clinical trial [published October 26, 2018]. Ann Surg. 2018. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003088.

- Yang NB, Garza LA, Foote CE, et al. High prevalence of stump dermatoses 38 years or more after amputation. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1283-1286.

- Meulenbelt HE, Geertzen JH, Jonkman MF, et al. Determinants of skin problems of the stump in lower-limb amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:74-81.

- Lin CH, Ma H, Chung MT, et al. Granulomatous cutaneous lesions associated with risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia in an amputated upper limb: risperidone-induced cutaneous granulomas. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:75-78.

- Schwartz RA, Bagley MP, Janniger CK, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of a leg amputation stump. Dermatology. 1991;182:193-195.

- Reilly GD, Boulton AJ, Harrington CI. Stump pemphigoid: a new complication of the amputee. Br Med J. 1983;287:875-876.

- Turan H, Bas¸kan EB, Adim SB, et al. Acroangiodermatitis in a below-knee amputation stump: correspondence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:560-561.

- Edwards DS, Kuhn KM, Potter BK, et al. Heterotopic ossification: a review of current understanding, treatment, and future. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30(suppl 3):S27-S30.

- Potter BK, Burns TC, Lacap AP, et al. Heterotopic ossification following traumatic and combat-related amputations: prevalence, risk factors, and preliminary results of excision. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:476-486.

- Tintle SM, Shawen SB, Forsberg JA, et al. Reoperation after combat-related major lower extremity amputations. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:232-237.

- Mckechnie PS, John A. Anxiety and depression following traumatic limb amputation: a systematic review. Injury. 2014;45:1859-1866.

- Hachisuka K, Nakamura T, Ohmine S, et al. Hygiene problems of residual limb and silicone liners in transtibial amputees wearing the total surface bearing socket. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1286-1290.

- Pantera E, Pourtier-Piotte C, Bensoussan L, et al. Patient education after amputation: systematic review and experts’ opinions. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;57:143-158.

- Blum C, Ehrler S, Isner ME. Assessment of therapeutic education in 135 lower limb amputees. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59:E161.

- Pasquina PF, Perry BN, Alphonso AL, et al. Residual limb hyperhidrosis and rimabotulinumtoxinB: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;97:659-664.e2.

- Mula KN, Winston J, Pace S, et al. Use of a microwave device for treatment of amputation residual limb hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:149-152.

- Shumaker PR, Kwan JM, Badiavas EV, et al. Rapid healing of scar-associated chronic wounds after ablative fractional resurfacing. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1289-1293.

- Anderson RR, Donelan MB, Hivnor C, et al. Laser treatment of traumatic scars with an emphasis on ablative fractional laser resurfacing: consensus report. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:187-193.

- Sanders JE, Mitchell SB, Wang YN, et al. An explant model for the investigation of skin adaptation to mechanical stress. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2002;49(12 pt 2):1626-1631.

- Wang YN, Sanders JE. How does skin adapt to repetitive mechanical stress to become load tolerant? Med Hypotheses. 2003;61:29-35.

- Sanders JE, Goldstein BS. Collagen fibril diameters increase and fibril densities decrease in skin subjected to repetitive compressive and shear stresses. J Biomech. 2001;34:1581-1587.

- Thangapazham R, Darling T, Meyerle J. Alteration of skin properties with autologous dermal fibroblasts. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:8407-8427.

- Rink CL, Wernke MM, Powell HM, et al. Standardized approach to quantitatively measure residual limb skin health in individuals with lower limb amputation. Adv Wound Care. 2017;6:225-232.

Limb amputation is a major life-changing event that markedly affects a patient’s quality of life as well as his/her ability to participate in activities of daily living. The most prevalent causes for amputation include vascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, trauma, and cancer, respectively.1,2 For amputees, maintaining prosthetic use is a major physical and psychological undertaking that benefits from a multidisciplinary team approach. Although individuals with lower limb amputations are disproportionately impacted by skin disease due to the increased mechanical forces exerted over the lower limbs, patients with upper limb amputations also develop dermatologic conditions secondary to wearing prostheses.

Approximately 185,000 amputations occur each year in the United States.3 Although amputations resulting from peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus tend to occur in older individuals, amputations in younger patients usually occur from trauma.2 The US military has experienced increasing numbers of amputations from trauma due to the ongoing combat operations in the Middle East. Although improvements in body armor and tactical combat casualty care have reduced the number of preventable deaths, the number of casualties surviving with extremity injuries requiring amputation has increased.4,5 As of October 2017, 1705 US servicemembers underwent major limb amputations, with 1914 lower limb amputations and 302 upper limb amputations. These amputations mainly impacted men aged 21 to 29 years, but female servicemembers also were affected, and a small group of servicemembers had multiple amputations.6

One of the most common medical problems that amputees face during long-term care is skin disease, with approximately 75% of amputees using a lower limb prosthesis experiencing skin problems. In general, amputees experience nearly 65% more dermatologic concerns than the general population.7 In one study of 97 individuals with transfemoral amputations, some of the most common issues associated with socket prosthetics included heat and sweating in the prosthetic socket (72%) as well as sores and skin irritation from the socket (62%).8 Given the high incidence of skin disease on residual limbs, dermatologists are uniquely positioned to keep the amputee in his/her prosthesis and prevent prosthetic abandonment.

Complications Following Amputation

Although US military servicemembers who undergo amputations receive the very best prosthetic devices and rehabilitation resources, they still experience prosthesis abandonment.9 Despite the fact that prosthetic limbs and prosthesis technology have substantially improved over the last 2 decades, one study indicated that the high frequency of problems affecting tissue viability at residual limbs is due to the age-old problem of prosthetic fit.10 In patients with the most advanced prostheses, poor fit still results in mechanical damage to the skin, as the residual limb is exposed to unequal and shearing forces across the amputation site as well as high pressures that cause a vaso-occlusive effect.11,12 Issues with poor fit are especially important for more active patients, as they normally want to immediately return to their vigorous preinjury lifestyles. In these patients, even a properly fitting prosthetic may not be able to overcome the fact that the residual limb skin is not well suited for the mechanical forces generated by the prosthesis and the humid environment of the socket.1,13 Another complicating factor is the dynamic nature of the residual limb. Muscle atrophy, changes in gait, and weight gain or loss can lead to an ill-fitting prosthetic and subsequent skin breakdown.

There are many case reports and review articles describing the skin problems in amputees.1,14-17 The Table summarizes these conditions and outlines treatment options for each.15,18-20

Most skin diseases on residual limbs are the result of mechanical skin breakdown, inflammation, infection, or combinations of these processes. Overall, amputees with diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease tend to have skin disease related to poor perfusion, whereas amputees who are active and healthy tend to have conditions related to mechanical stress.7,13,14,17,21,22 Bui et al17 reported ulcers, abscesses, and blisters as the most common skin conditions that occur at the site of residual limbs; however, other less common dermatologic disorders such as skin malignancies, verrucous hyperplasia and carcinoma, granulomatous cutaneous lesions, acroangiodermatitis, and bullous pemphigoid also are seen.23-26 Buikema and Meyerle15 hypothesize that these conditions, as well as the more common skin diseases, are partly from the amputation disrupting blood and lymphatic flow in the residual limb, which causes the site to act as an immunocompromised district that induces dysregulation of neuroimmune regulators.

It is important to note that skin disease on residual limbs is not just an acute problem. Long-term follow-up of 247 traumatic amputees from the Vietnam War showed that almost half of prosthesis users (48.2%) reported a skin problem in the preceding year, more than 38 years after the amputation. Additionally, one-quarter of these individuals experienced skin problems approximately 50% of the time, which unfortunately led to limited use or total abandonment of the prosthesis for the preceding year in 56% of the veterans surveyed.21

Other complications following amputation indirectly lead to skin problems. Heterotopic ossification, or the formation of bone at extraskeletal sites, has been observed in up to 65% of military amputees from recent operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.27,28 If symptomatic, heterotopic ossification can lead to poor prosthetic fit and subsequent skin breakdown. As a result, it has been reported that up to 40% of combat-related lower extremity amputations may require excision of heterotopic ossificiation.29

Amputation also can result in psychologic concerns that indirectly affect skin health. A systematic review by Mckechnie and John30 suggested that despite heterogeneity between studies, even using the lowest figures demonstrated the significance anxiety and depression play in the lives of traumatic amputees. If left untreated, these mental health issues can lead to poor residual limb hygiene and prosthetic maintenance due to reductions in the patient’s energy and motivation. Studies have shown that proper hygiene of residual limbs and silicone liners reduces associated skin problems.19,31

Role of the Dermatologist

Routine care and conservative management of amputee skin problems often are accomplished by prosthetists, primary care physicians, nurses, and physical therapists. In one study, more than 80% of the most common skin problems affecting amputees could be attributed to the prosthesis itself, which highlights the importance of the continued involvement of the prosthetist beyond the initial fitting period.13 However, when a skin problem becomes refractory to conservative management, referral to a dermatologist is prudent; therefore, the dermatologist is an integral member of the multidisciplinary team that provides care for amputees.

The dermatologist often is best positioned to diagnose skin diseases that result from wearing prostheses and is well versed in treatments for short-term and long-term management of skin disease on residual limbs. The dermatologist also can offer prophylactic treatments to decrease sweating and hair growth to prevent potential infections and subsequent skin breakdown. Additionally, proper education on self-care has been shown to decrease the amount of skin problems and increase functional status and quality of life for amputees.32,33 Dermatologists can assist with the patient education process as well as refer amputees to a useful resource from the Amputee Coalition website (www.amputee-coalition.org) to provide specific patient education on how to maintain skin on the residual limb to prevent skin disease.

Current Treatments and Future Directions

Skin disorders affecting residual limbs usually are conditions that dermatologists commonly encounter and are comfortable managing in general practice. Additionally, dermatologists routinely treat hyperhidrosis and conduct laser hair removal, both of which are effective prophylactic adjuncts for amputee skin health. There are a few treatments for reducing residual limb hyperhidrosis that are particularly useful. Although first-line treatment of residual limb hyperhidrosis often is topical aluminum chloride, it requires frequent application and often causes considerable skin irritation when applied to residual limbs. Alternatively, intradermal botulinum toxin has been shown to successfully reduce sweat production in individuals with residual limb hyperhidrosis and is well tolerated.34 A 2017 case report discussed the use of microwave thermal ablation of eccrine coils using a noninvasive 3-step hyperhidrosis treatment system on a bilateral below-the-knee amputee. The authors reported the patient tolerated the procedure well with decreased dermatitis and folliculitis, leading to his ability to wear a prosthetic for longer periods of time.35

Ablative fractional resurfacing with a CO2 laser is another key treatment modality central to amputees, more specifically to traumatic amputees. A CO2 laser can decrease skin tension and increase skin mobility associated with traumatic scars as well as decrease skin vulnerability to biofilms present in chronic wounds on residual limbs. It is believed that the pattern of injury caused by ablative fractional lasers disrupts biofilms and stimulates growth factor secretion and collagen remodeling through the concept of photomicrodebridement.36 The ablative fractional resurfacing approach to scar therapy and chronic wound debridement can result in less skin injury, allowing the amputee to continue rehabilitation and return more quickly to prosthetic use.37

One interesting area of research in amputee care involves the study of novel ways to increase the skin’s ability to adapt to mechanical stress and load bearing and accelerate wound healing on the residual limb. Multiple studies have identified collagen fibril enlargement as an important component of skin adaptation, and biomolecules such as decorin may enhance this process.38-40 The concept of increasing these biomolecules at the correct time during wound healing to strengthen the residual limb tissue currently is being studied.39

Another encouraging area of research is the involvement of fibroblasts in cutaneous wound healing and their role in determining the phenotype of residual limb skin in amputees. The clinical application of autologous fibroblasts is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for cosmetic use as a filler material and currently is under research for other applications, such as skin regeneration after surgery or manipulating skin characteristics to enhance the durability of residual limbs.41

Future preventative care of amputee skin may rely on tracking residual limb health before severe tissue injury occurs. For instance, Rink et al42 described an approach to monitor residual limb health using noninvasive imaging (eg, hyperspectral imaging, laser speckle imaging) and noninvasive probes that measure oxygenation, perfusion, skin barrier function, and skin hydration to the residual limb. Although these limb surveillance sensors would be employed by prosthetists, the dermatologist, as part of the multispecialty team, also could leverage the data for diagnosis and treatment considerations.

Final Thoughts

The dermatologist is an important member of the multidisciplinary team involved in the care of amputees. Skin disease is prevalent in amputees throughout their lives and often leads to abandonment of prostheses. Although current therapies and preventative treatments are for the most part successful, future research involving advanced technology to monitor skin health, increasing residual limb skin durability at the molecular level, and targeted laser therapies are promising. Through engagement and effective collaboration with the entire multidisciplinary team, dermatologists will have a considerable impact on amputee skin health.

Limb amputation is a major life-changing event that markedly affects a patient’s quality of life as well as his/her ability to participate in activities of daily living. The most prevalent causes for amputation include vascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, trauma, and cancer, respectively.1,2 For amputees, maintaining prosthetic use is a major physical and psychological undertaking that benefits from a multidisciplinary team approach. Although individuals with lower limb amputations are disproportionately impacted by skin disease due to the increased mechanical forces exerted over the lower limbs, patients with upper limb amputations also develop dermatologic conditions secondary to wearing prostheses.

Approximately 185,000 amputations occur each year in the United States.3 Although amputations resulting from peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus tend to occur in older individuals, amputations in younger patients usually occur from trauma.2 The US military has experienced increasing numbers of amputations from trauma due to the ongoing combat operations in the Middle East. Although improvements in body armor and tactical combat casualty care have reduced the number of preventable deaths, the number of casualties surviving with extremity injuries requiring amputation has increased.4,5 As of October 2017, 1705 US servicemembers underwent major limb amputations, with 1914 lower limb amputations and 302 upper limb amputations. These amputations mainly impacted men aged 21 to 29 years, but female servicemembers also were affected, and a small group of servicemembers had multiple amputations.6

One of the most common medical problems that amputees face during long-term care is skin disease, with approximately 75% of amputees using a lower limb prosthesis experiencing skin problems. In general, amputees experience nearly 65% more dermatologic concerns than the general population.7 In one study of 97 individuals with transfemoral amputations, some of the most common issues associated with socket prosthetics included heat and sweating in the prosthetic socket (72%) as well as sores and skin irritation from the socket (62%).8 Given the high incidence of skin disease on residual limbs, dermatologists are uniquely positioned to keep the amputee in his/her prosthesis and prevent prosthetic abandonment.

Complications Following Amputation

Although US military servicemembers who undergo amputations receive the very best prosthetic devices and rehabilitation resources, they still experience prosthesis abandonment.9 Despite the fact that prosthetic limbs and prosthesis technology have substantially improved over the last 2 decades, one study indicated that the high frequency of problems affecting tissue viability at residual limbs is due to the age-old problem of prosthetic fit.10 In patients with the most advanced prostheses, poor fit still results in mechanical damage to the skin, as the residual limb is exposed to unequal and shearing forces across the amputation site as well as high pressures that cause a vaso-occlusive effect.11,12 Issues with poor fit are especially important for more active patients, as they normally want to immediately return to their vigorous preinjury lifestyles. In these patients, even a properly fitting prosthetic may not be able to overcome the fact that the residual limb skin is not well suited for the mechanical forces generated by the prosthesis and the humid environment of the socket.1,13 Another complicating factor is the dynamic nature of the residual limb. Muscle atrophy, changes in gait, and weight gain or loss can lead to an ill-fitting prosthetic and subsequent skin breakdown.

There are many case reports and review articles describing the skin problems in amputees.1,14-17 The Table summarizes these conditions and outlines treatment options for each.15,18-20

Most skin diseases on residual limbs are the result of mechanical skin breakdown, inflammation, infection, or combinations of these processes. Overall, amputees with diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease tend to have skin disease related to poor perfusion, whereas amputees who are active and healthy tend to have conditions related to mechanical stress.7,13,14,17,21,22 Bui et al17 reported ulcers, abscesses, and blisters as the most common skin conditions that occur at the site of residual limbs; however, other less common dermatologic disorders such as skin malignancies, verrucous hyperplasia and carcinoma, granulomatous cutaneous lesions, acroangiodermatitis, and bullous pemphigoid also are seen.23-26 Buikema and Meyerle15 hypothesize that these conditions, as well as the more common skin diseases, are partly from the amputation disrupting blood and lymphatic flow in the residual limb, which causes the site to act as an immunocompromised district that induces dysregulation of neuroimmune regulators.

It is important to note that skin disease on residual limbs is not just an acute problem. Long-term follow-up of 247 traumatic amputees from the Vietnam War showed that almost half of prosthesis users (48.2%) reported a skin problem in the preceding year, more than 38 years after the amputation. Additionally, one-quarter of these individuals experienced skin problems approximately 50% of the time, which unfortunately led to limited use or total abandonment of the prosthesis for the preceding year in 56% of the veterans surveyed.21

Other complications following amputation indirectly lead to skin problems. Heterotopic ossification, or the formation of bone at extraskeletal sites, has been observed in up to 65% of military amputees from recent operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.27,28 If symptomatic, heterotopic ossification can lead to poor prosthetic fit and subsequent skin breakdown. As a result, it has been reported that up to 40% of combat-related lower extremity amputations may require excision of heterotopic ossificiation.29

Amputation also can result in psychologic concerns that indirectly affect skin health. A systematic review by Mckechnie and John30 suggested that despite heterogeneity between studies, even using the lowest figures demonstrated the significance anxiety and depression play in the lives of traumatic amputees. If left untreated, these mental health issues can lead to poor residual limb hygiene and prosthetic maintenance due to reductions in the patient’s energy and motivation. Studies have shown that proper hygiene of residual limbs and silicone liners reduces associated skin problems.19,31

Role of the Dermatologist

Routine care and conservative management of amputee skin problems often are accomplished by prosthetists, primary care physicians, nurses, and physical therapists. In one study, more than 80% of the most common skin problems affecting amputees could be attributed to the prosthesis itself, which highlights the importance of the continued involvement of the prosthetist beyond the initial fitting period.13 However, when a skin problem becomes refractory to conservative management, referral to a dermatologist is prudent; therefore, the dermatologist is an integral member of the multidisciplinary team that provides care for amputees.

The dermatologist often is best positioned to diagnose skin diseases that result from wearing prostheses and is well versed in treatments for short-term and long-term management of skin disease on residual limbs. The dermatologist also can offer prophylactic treatments to decrease sweating and hair growth to prevent potential infections and subsequent skin breakdown. Additionally, proper education on self-care has been shown to decrease the amount of skin problems and increase functional status and quality of life for amputees.32,33 Dermatologists can assist with the patient education process as well as refer amputees to a useful resource from the Amputee Coalition website (www.amputee-coalition.org) to provide specific patient education on how to maintain skin on the residual limb to prevent skin disease.

Current Treatments and Future Directions

Skin disorders affecting residual limbs usually are conditions that dermatologists commonly encounter and are comfortable managing in general practice. Additionally, dermatologists routinely treat hyperhidrosis and conduct laser hair removal, both of which are effective prophylactic adjuncts for amputee skin health. There are a few treatments for reducing residual limb hyperhidrosis that are particularly useful. Although first-line treatment of residual limb hyperhidrosis often is topical aluminum chloride, it requires frequent application and often causes considerable skin irritation when applied to residual limbs. Alternatively, intradermal botulinum toxin has been shown to successfully reduce sweat production in individuals with residual limb hyperhidrosis and is well tolerated.34 A 2017 case report discussed the use of microwave thermal ablation of eccrine coils using a noninvasive 3-step hyperhidrosis treatment system on a bilateral below-the-knee amputee. The authors reported the patient tolerated the procedure well with decreased dermatitis and folliculitis, leading to his ability to wear a prosthetic for longer periods of time.35

Ablative fractional resurfacing with a CO2 laser is another key treatment modality central to amputees, more specifically to traumatic amputees. A CO2 laser can decrease skin tension and increase skin mobility associated with traumatic scars as well as decrease skin vulnerability to biofilms present in chronic wounds on residual limbs. It is believed that the pattern of injury caused by ablative fractional lasers disrupts biofilms and stimulates growth factor secretion and collagen remodeling through the concept of photomicrodebridement.36 The ablative fractional resurfacing approach to scar therapy and chronic wound debridement can result in less skin injury, allowing the amputee to continue rehabilitation and return more quickly to prosthetic use.37

One interesting area of research in amputee care involves the study of novel ways to increase the skin’s ability to adapt to mechanical stress and load bearing and accelerate wound healing on the residual limb. Multiple studies have identified collagen fibril enlargement as an important component of skin adaptation, and biomolecules such as decorin may enhance this process.38-40 The concept of increasing these biomolecules at the correct time during wound healing to strengthen the residual limb tissue currently is being studied.39

Another encouraging area of research is the involvement of fibroblasts in cutaneous wound healing and their role in determining the phenotype of residual limb skin in amputees. The clinical application of autologous fibroblasts is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for cosmetic use as a filler material and currently is under research for other applications, such as skin regeneration after surgery or manipulating skin characteristics to enhance the durability of residual limbs.41

Future preventative care of amputee skin may rely on tracking residual limb health before severe tissue injury occurs. For instance, Rink et al42 described an approach to monitor residual limb health using noninvasive imaging (eg, hyperspectral imaging, laser speckle imaging) and noninvasive probes that measure oxygenation, perfusion, skin barrier function, and skin hydration to the residual limb. Although these limb surveillance sensors would be employed by prosthetists, the dermatologist, as part of the multispecialty team, also could leverage the data for diagnosis and treatment considerations.

Final Thoughts

The dermatologist is an important member of the multidisciplinary team involved in the care of amputees. Skin disease is prevalent in amputees throughout their lives and often leads to abandonment of prostheses. Although current therapies and preventative treatments are for the most part successful, future research involving advanced technology to monitor skin health, increasing residual limb skin durability at the molecular level, and targeted laser therapies are promising. Through engagement and effective collaboration with the entire multidisciplinary team, dermatologists will have a considerable impact on amputee skin health.

- Dudek NL, Marks MB, Marshall SC, et al. Dermatologic conditions associated with use of a lower-extremity prosthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:659-663.

- Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, et al. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:422-429.

- Kozak LJ. Ambulatory and Inpatient Procedures in the United States, 1995. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1998.

- Epstein RA, Heinemann AW, McFarland LV. Quality of life for veterans and servicemembers with major traumatic limb loss from Vietnam and OIF/OEF conflicts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47:373-385.

- Dougherty AL, Mohrle CR, Galarneau MR, et al. Battlefield extremity injuries in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Injury. 2009;40:772-777.

- Farrokhi S, Perez K, Eskridge S, et al. Major deployment-related amputations of lower and upper limbs, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2017. MSMR. 2018;25:10-16.

- Highsmith MJ, Highsmith JT. Identifying and managing skin issues with lower-limb prosthetic use. Amputee Coalition website. https://www.amputee-coalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/.../skin_issues_lower.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2019.

- Hagberg K, Brånemark R. Consequences of non-vascular trans-femoral amputation: a survey of quality of life, prosthetic use and problems. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2001;25:186-194.

- Gajewski D, Granville R. The United States Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(10 spec no):S183-S187.

- Butler K, Bowen C, Hughes AM, et al. A systematic review of the key factors affecting tissue viability and rehabilitation outcomes of the residual limb in lower extremity traumatic amputees. J Tissue Viability. 2014;23:81-93.

- Mak AF, Zhang M, Boone DA. State-of-the-art research in lower-limb prosthetic biomechanics-socket interface: a review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001;38:161-174.

- Silver-Thorn MB, Steege JW. A review of prosthetic interface stress investigations. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1996;33:253-266.

- Dudek NL, Marks MB, Marshall SC. Skin problems in an amputee clinic. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85:424-429.

- Meulenbelt HE, Geertzen JH, Dijkstra PU, et al. Skin problems in lower limb amputees: an overview by case reports. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:147-155.

- Buikema KE, Meyerle JH. Amputation stump: privileged harbor for infections, tumors, and immune disorders. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:670-677.

- Highsmith JT, Highsmith MJ. Common skin pathology in LE prosthesis users. JAAPA. 2007;20:33-36, 47.

- Bui KM, Raugi GJ, Nguyen VQ, et al. Skin problems in individuals with lower-limb loss: literature review and proposed classification system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:1085-1090.

- Levy SW. Skin Problems of the Amputee. St. Louis, MO: Warren H. Green Inc; 1983.

- Levy SW, Allende MF, Barnes GH. Skin problems of the leg amputee. Arch Dermatol. 1962;85:65-81.

- Dumanian GA, Potter BK, Mioton LM, et al. Targeted muscle reinnervation treats neuroma and phantom pain in major limb amputees: a randomized clinical trial [published October 26, 2018]. Ann Surg. 2018. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003088.

- Yang NB, Garza LA, Foote CE, et al. High prevalence of stump dermatoses 38 years or more after amputation. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1283-1286.

- Meulenbelt HE, Geertzen JH, Jonkman MF, et al. Determinants of skin problems of the stump in lower-limb amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:74-81.

- Lin CH, Ma H, Chung MT, et al. Granulomatous cutaneous lesions associated with risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia in an amputated upper limb: risperidone-induced cutaneous granulomas. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:75-78.

- Schwartz RA, Bagley MP, Janniger CK, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of a leg amputation stump. Dermatology. 1991;182:193-195.

- Reilly GD, Boulton AJ, Harrington CI. Stump pemphigoid: a new complication of the amputee. Br Med J. 1983;287:875-876.

- Turan H, Bas¸kan EB, Adim SB, et al. Acroangiodermatitis in a below-knee amputation stump: correspondence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:560-561.

- Edwards DS, Kuhn KM, Potter BK, et al. Heterotopic ossification: a review of current understanding, treatment, and future. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30(suppl 3):S27-S30.

- Potter BK, Burns TC, Lacap AP, et al. Heterotopic ossification following traumatic and combat-related amputations: prevalence, risk factors, and preliminary results of excision. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:476-486.

- Tintle SM, Shawen SB, Forsberg JA, et al. Reoperation after combat-related major lower extremity amputations. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:232-237.

- Mckechnie PS, John A. Anxiety and depression following traumatic limb amputation: a systematic review. Injury. 2014;45:1859-1866.

- Hachisuka K, Nakamura T, Ohmine S, et al. Hygiene problems of residual limb and silicone liners in transtibial amputees wearing the total surface bearing socket. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1286-1290.

- Pantera E, Pourtier-Piotte C, Bensoussan L, et al. Patient education after amputation: systematic review and experts’ opinions. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;57:143-158.

- Blum C, Ehrler S, Isner ME. Assessment of therapeutic education in 135 lower limb amputees. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59:E161.

- Pasquina PF, Perry BN, Alphonso AL, et al. Residual limb hyperhidrosis and rimabotulinumtoxinB: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;97:659-664.e2.

- Mula KN, Winston J, Pace S, et al. Use of a microwave device for treatment of amputation residual limb hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:149-152.

- Shumaker PR, Kwan JM, Badiavas EV, et al. Rapid healing of scar-associated chronic wounds after ablative fractional resurfacing. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1289-1293.

- Anderson RR, Donelan MB, Hivnor C, et al. Laser treatment of traumatic scars with an emphasis on ablative fractional laser resurfacing: consensus report. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:187-193.

- Sanders JE, Mitchell SB, Wang YN, et al. An explant model for the investigation of skin adaptation to mechanical stress. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2002;49(12 pt 2):1626-1631.

- Wang YN, Sanders JE. How does skin adapt to repetitive mechanical stress to become load tolerant? Med Hypotheses. 2003;61:29-35.

- Sanders JE, Goldstein BS. Collagen fibril diameters increase and fibril densities decrease in skin subjected to repetitive compressive and shear stresses. J Biomech. 2001;34:1581-1587.

- Thangapazham R, Darling T, Meyerle J. Alteration of skin properties with autologous dermal fibroblasts. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:8407-8427.

- Rink CL, Wernke MM, Powell HM, et al. Standardized approach to quantitatively measure residual limb skin health in individuals with lower limb amputation. Adv Wound Care. 2017;6:225-232.

- Dudek NL, Marks MB, Marshall SC, et al. Dermatologic conditions associated with use of a lower-extremity prosthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:659-663.

- Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, et al. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:422-429.

- Kozak LJ. Ambulatory and Inpatient Procedures in the United States, 1995. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 1998.

- Epstein RA, Heinemann AW, McFarland LV. Quality of life for veterans and servicemembers with major traumatic limb loss from Vietnam and OIF/OEF conflicts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47:373-385.

- Dougherty AL, Mohrle CR, Galarneau MR, et al. Battlefield extremity injuries in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Injury. 2009;40:772-777.

- Farrokhi S, Perez K, Eskridge S, et al. Major deployment-related amputations of lower and upper limbs, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2001-2017. MSMR. 2018;25:10-16.

- Highsmith MJ, Highsmith JT. Identifying and managing skin issues with lower-limb prosthetic use. Amputee Coalition website. https://www.amputee-coalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/.../skin_issues_lower.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2019.

- Hagberg K, Brånemark R. Consequences of non-vascular trans-femoral amputation: a survey of quality of life, prosthetic use and problems. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2001;25:186-194.

- Gajewski D, Granville R. The United States Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(10 spec no):S183-S187.

- Butler K, Bowen C, Hughes AM, et al. A systematic review of the key factors affecting tissue viability and rehabilitation outcomes of the residual limb in lower extremity traumatic amputees. J Tissue Viability. 2014;23:81-93.

- Mak AF, Zhang M, Boone DA. State-of-the-art research in lower-limb prosthetic biomechanics-socket interface: a review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2001;38:161-174.

- Silver-Thorn MB, Steege JW. A review of prosthetic interface stress investigations. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1996;33:253-266.

- Dudek NL, Marks MB, Marshall SC. Skin problems in an amputee clinic. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85:424-429.

- Meulenbelt HE, Geertzen JH, Dijkstra PU, et al. Skin problems in lower limb amputees: an overview by case reports. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:147-155.

- Buikema KE, Meyerle JH. Amputation stump: privileged harbor for infections, tumors, and immune disorders. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:670-677.

- Highsmith JT, Highsmith MJ. Common skin pathology in LE prosthesis users. JAAPA. 2007;20:33-36, 47.

- Bui KM, Raugi GJ, Nguyen VQ, et al. Skin problems in individuals with lower-limb loss: literature review and proposed classification system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:1085-1090.

- Levy SW. Skin Problems of the Amputee. St. Louis, MO: Warren H. Green Inc; 1983.

- Levy SW, Allende MF, Barnes GH. Skin problems of the leg amputee. Arch Dermatol. 1962;85:65-81.

- Dumanian GA, Potter BK, Mioton LM, et al. Targeted muscle reinnervation treats neuroma and phantom pain in major limb amputees: a randomized clinical trial [published October 26, 2018]. Ann Surg. 2018. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000003088.

- Yang NB, Garza LA, Foote CE, et al. High prevalence of stump dermatoses 38 years or more after amputation. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1283-1286.

- Meulenbelt HE, Geertzen JH, Jonkman MF, et al. Determinants of skin problems of the stump in lower-limb amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:74-81.

- Lin CH, Ma H, Chung MT, et al. Granulomatous cutaneous lesions associated with risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia in an amputated upper limb: risperidone-induced cutaneous granulomas. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:75-78.

- Schwartz RA, Bagley MP, Janniger CK, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of a leg amputation stump. Dermatology. 1991;182:193-195.

- Reilly GD, Boulton AJ, Harrington CI. Stump pemphigoid: a new complication of the amputee. Br Med J. 1983;287:875-876.

- Turan H, Bas¸kan EB, Adim SB, et al. Acroangiodermatitis in a below-knee amputation stump: correspondence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:560-561.

- Edwards DS, Kuhn KM, Potter BK, et al. Heterotopic ossification: a review of current understanding, treatment, and future. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30(suppl 3):S27-S30.

- Potter BK, Burns TC, Lacap AP, et al. Heterotopic ossification following traumatic and combat-related amputations: prevalence, risk factors, and preliminary results of excision. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:476-486.

- Tintle SM, Shawen SB, Forsberg JA, et al. Reoperation after combat-related major lower extremity amputations. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:232-237.

- Mckechnie PS, John A. Anxiety and depression following traumatic limb amputation: a systematic review. Injury. 2014;45:1859-1866.

- Hachisuka K, Nakamura T, Ohmine S, et al. Hygiene problems of residual limb and silicone liners in transtibial amputees wearing the total surface bearing socket. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:1286-1290.

- Pantera E, Pourtier-Piotte C, Bensoussan L, et al. Patient education after amputation: systematic review and experts’ opinions. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;57:143-158.

- Blum C, Ehrler S, Isner ME. Assessment of therapeutic education in 135 lower limb amputees. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59:E161.

- Pasquina PF, Perry BN, Alphonso AL, et al. Residual limb hyperhidrosis and rimabotulinumtoxinB: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;97:659-664.e2.

- Mula KN, Winston J, Pace S, et al. Use of a microwave device for treatment of amputation residual limb hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:149-152.

- Shumaker PR, Kwan JM, Badiavas EV, et al. Rapid healing of scar-associated chronic wounds after ablative fractional resurfacing. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1289-1293.

- Anderson RR, Donelan MB, Hivnor C, et al. Laser treatment of traumatic scars with an emphasis on ablative fractional laser resurfacing: consensus report. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:187-193.

- Sanders JE, Mitchell SB, Wang YN, et al. An explant model for the investigation of skin adaptation to mechanical stress. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2002;49(12 pt 2):1626-1631.

- Wang YN, Sanders JE. How does skin adapt to repetitive mechanical stress to become load tolerant? Med Hypotheses. 2003;61:29-35.

- Sanders JE, Goldstein BS. Collagen fibril diameters increase and fibril densities decrease in skin subjected to repetitive compressive and shear stresses. J Biomech. 2001;34:1581-1587.

- Thangapazham R, Darling T, Meyerle J. Alteration of skin properties with autologous dermal fibroblasts. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:8407-8427.

- Rink CL, Wernke MM, Powell HM, et al. Standardized approach to quantitatively measure residual limb skin health in individuals with lower limb amputation. Adv Wound Care. 2017;6:225-232.

Practice Points

- Amputees have an increased risk for skin disease occurring on residual limbs.

- It is important to educate patients about proper hygiene techniques for residual limbs and prostheses as well as common signs and symptoms of skin disease at the amputation site.

- Amputees should see a dermatologist within the first year after amputation and often benefit from annual follow-up examinations.

- Early referral to a dermatologist for skin disease affecting residual limbs is warranted.