User login

The Association of Discharge Before Noon and Length of Stay in Hospitalized Pediatric Patients

Many hospitals and emergency departments (EDs) face challenges posed by overcrowding and hospital throughput. Slow ED throughput has been associated with worse patient outcomes.1 One strategy increasingly employed to improve hospital throughput is to increase the rate of inpatient discharges earlier in the day, which is often defined as discharges before noon (DCBNs). The hypothesis behind DCBN is that earlier hospital discharges will allow for earlier ED admissions and thus mitigate ED overcrowding while optimizing inpatient hospital flow. Previous quality improvement efforts to increase the percentage of DCBNs have been successfully implemented. For example, Wertheimer et al. implemented a process for earlier discharges and reported a 27-percentage point (11% to 38%) increase in DCBN on general medicine units.2 In a recent survey among leaders in hospital medicine programs, a majority reported early discharge as an important institutional goal.3

Studies of the effectiveness of DCBN initiatives on improving throughput and shortening length of stay (LOS) in adult patients have had mixed results. Computer modeling has supported the idea that earlier inpatient discharges would shorten ED patient boarding time.4

A question of interest for hospitals is if DCBN is a good indicator of shorter LOS, or is DCBN an arbitrary indicator, as morning discharges might just be the result of a delayed discharge of a patient ready for discharge the prior afternoon/evening. Our study objectives were: (1) to determine whether DCBN is associated with a shorter LOS in a pediatric population at an academic medical center, and (2) to examine separately this association in medical and surgical patients given the different provider workflow and patient clinical characteristics in those groups.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and Settings

We included patients 21 years or younger with an inpatient admission to any of the following pediatric medical or surgical services: cardiac surgery, cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, general services, hematology/oncology, nephrology, orthopedics, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, pulmonology, and urology. Patients whose stay did not extend beyond one midnight were excluded because discharge time of day for these short stays was strongly related to the time of admission. We also excluded patients whose stay extended beyond two standard deviations of the average LOS for the discharge service under the assumption that these patients represented atypical circumstances. Finally, we excluded patients who died or left against medical advice. A consortium diagram of all exclusion criteria can be found in Supplemental Figure 1. Discharge data were extracted from the Carolina Database Warehouse, a data repository of the University of North Carolina Health System. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study (IRB 17-0500).

Measures

The outcome of interest was LOS, defined as discharge date and time minus admission date and time, and thus a continuous measure of time in the hospital rather than a number of midnights. Rajkomar et al. used the same definition of LOS.6 The independent variable of interest was whether the discharge occurred before noon. Because discharges between midnight and 8:00

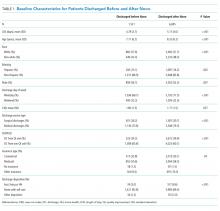

All model covariates were collected at the patient level (Table 1)

Statistical Analysis

Student t tests and χ2 statistics were used to compare baseline characteristics of hospitalizations of patients DCBN and after noon. We used ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models to assess the association between DCBN and LOS. Because DCBN may be correlated with patient characteristics, we used propensity score weighted models. Propensity scores were estimated using a logistic regression predicting DCBN using the variables given in Table 1 (excluding the outcome variable LOS). To estimate the average treatment effect on the entire sample for each model, we weighted each observation by the inverse-probability of treatment as per recent propensity score methods detailed by Garrido et al.9 In the inverse-probability weighted models, we clustered on attending physician to adjust for the autocorrelation caused by unobservable similarities of discharges by the same attending. We tested for multicollinearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF). To test our secondary hypothesis that there was a difference in the relationship between DCBN and LOS based on service type (medical versus surgical), we tested if the service type moderated any of the coefficients using a joint Wald test on the 10 coefficients interacted with the service type.

For our sensitivity analysis, we reran all surgical and medical discharges models changing the LOS outlier exclusion criteria to greater than three and then four standard deviations. Statistical modeling and analysis were completed using Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Our study sample comprised 8,226 pediatric hospitalizations with a LOS mean of 5.10 and a median of 3.91 days respectively (range, 1.25-32.83 days). There were 1,531 (18.6%) DCBNs. Compared to those discharged after noon, patients with DCBN had a higher probability of being surgical patients, having commercial insurance, discharge home with self-care, discharge on the weekend, and discharge from a nonquality improvement unit (Table 1). Patients with DCBN were also more likely to be white, non-Hispanic, and male.

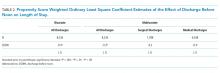

Our propensity score weighted ordinary least score (OLS) LOS regression results are presented in Table 2. In the bivariate analysis, DCBN was associated with an average 0.40 day, or roughly 10 hours, shorter LOS (P < .001). In the multivariate model of all discharges, we found that DCBN was associated with a mean of 0.27 day (P = .010) shorter LOS when compared to discharge in the afternoon when controlling for age, race, ethnicity, weekend discharge, discharge from quality improvement unit, discharge service type, CMI, insurance type, and discharge disposition.

There was no evidence of multicollinearity (mean VIF of 1.14). The Wald test returned an F statistic of 27.50 (P < .001) indicating there was a structural difference in the relationship between LOS and DCBN dependent on discharge service type; thus, we ran separate surgical and medical discharge models to interpret model coefficients for both service types. When we analyzed surgical and medical discharges in separate models, the effect of DCBN on LOS in the medical discharges model was significantly associated with a 0.30 day (P = .017) shorter LOS (Table 2). The association was not significant in the surgical discharges model.

To further test the analysis, we increased the LOS outlier exclusion criteria to three and four standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

The differential effect of DCBN on LOS in surgical and medical discharges suggests that the relationship between DCBN and LOS may be related to provider team workflow. For example, surgical teams may tend to round one time per day early in the morning before spending the entire day in the operating room, and thus completing more early morning discharge orders compared to medical teams. However, if a patient on a surgical service is not ready for discharge first thing in the morning, the patient may be more likely to wait until the following morning for a discharge order. On medical services, physician schedules may allow for more flexibility for rounding and responding with a discharge order when a patient becomes ready; however, medical services may round later in the day compared to surgeons and for a longer period of time, delaying discharges beyond noon that could have been made earlier. Another possibility, given UNC pediatric services are loosely regionalized with surgical patients concentrated more in one unit, is that unit-level differences in how staff processed discharges could have contributed to the difference observed between medical and surgical patients, particularly as there was a unit-level quality improvement effort for decreasing discharge time on one of two medical floors. However, we analyzed for differences based on the discharging unit and found no association. The influence of outliers on the association between DCBN and LOS increases also suggests that this group of children who have extremely long hospital stays might need further exploration.

Our study has some similar and some contrasting results with prior studies in adult patients. Our findings support the modeling literature that suggests DCBN may improve discharge efficiency by shortening patient LOS for some discharges.4 These findings contrast with Rajkomar et al., who reported that DCBN was associated with a longer LOS in adult patients.6 The contrasting findings could be due to differences in pediatric versus adult patients.

Our study has several limitations. While we controlled for observable characteristics using covariates and propensity score weighted analyses, there are likely unobservable characteristics that confound our analysis. We did not measure other factors that may affect discharge time of day such as high occupancy, staffing levels, patient transportation availability, and patient and family preferences. Given these limitations, we caution against interpreting a causal relationship between independent variables and the outcome. Finally, this analysis was conducted at a single tertiary care, academic medical center. The majority of pediatric admissions at this institution are either transferred from other hospitals or scheduled admissions for medical or surgical care. A smaller proportion of discharges are acute, unplanned admissions through our emergency department in children with or without underlying medical complexity. These factors plus the exclusion of observation, extended recovery, and all the less than two-day stays in this study contribute to a relatively higher average LOS. These factors potentially limit generalizability to other care settings. Additionally, the majority of the care teams involve care by resident physicians, and they are often the primary caregivers and write the majority of orders in patient charts such as discharge orders. While we were not able to control for within resident physician similarities between patients, we did control for autocorrelation at the attending level.

CONCLUSION

The results of our study suggest that DCBN is associated with a decreased LOS for medical but not surgical pediatric patients. DCBN may not be an appropriate measure for all services. Further research should be done to identify other feasible but more valid indicators for shorter LOS.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial relationships relative to this article to disclose. The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding

There were no external sources of funding for this work.

1. Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):1-10. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00295.x. PubMed

2. Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: an achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210-214. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2154. PubMed

3. Patel H, Fang MC, Mourad M, et al. Hospitalist and internal medicine leaders’ perspectives of early discharge challenges at academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2017;13(6):388-391. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2885. PubMed

4. Powell ES, Khare RK, Venkatesh AK, Van Roo BD, Adams JG, Reinhardt G. The relationship between inpatient discharge timing and emergency department boarding. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(2):186-196. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.06.028. PubMed

5. Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Iturrate E, Bailey M, Hochman K. Discharge before noon: effect on throughput and sustainability. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):664-669. doi:10.1002/jhm.2412. PubMed

6. Rajkomar A, Valencia V, Novelero M, Mourad M, Auerbach A. The association between discharge before noon and length of stay in medical and surgical patients. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):859-861. doi:10.1002/jhm.2529. PubMed

7. Shine D. Discharge before noon: an urban legend. Am J Med. 2015;128(5):445-446. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.12.011. PubMed

8. Sauer B, Brookhart MA, Roy JA, VanderWeele TJ. Covariate selection. In: Velentgas P, Dreyer NA, Nourjah P, Smith SR, Torchia MM, eds. Developing a Protocol for Observational Comparative Effectiveness Research: A User’s Guide. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013. PubMed

9. Garrido MM, Kelley AS, Paris J, et al. Methods for constructing and assessing propensity scores. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(5):1701-1720. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12182. PubMed

10. Maguire P. Do discharge-before-noon Intiatives work? 2016. https://www.todayshospitalist.com/do-discharge-before-noon-initiatives-work/. Accessed April, 2018.

Many hospitals and emergency departments (EDs) face challenges posed by overcrowding and hospital throughput. Slow ED throughput has been associated with worse patient outcomes.1 One strategy increasingly employed to improve hospital throughput is to increase the rate of inpatient discharges earlier in the day, which is often defined as discharges before noon (DCBNs). The hypothesis behind DCBN is that earlier hospital discharges will allow for earlier ED admissions and thus mitigate ED overcrowding while optimizing inpatient hospital flow. Previous quality improvement efforts to increase the percentage of DCBNs have been successfully implemented. For example, Wertheimer et al. implemented a process for earlier discharges and reported a 27-percentage point (11% to 38%) increase in DCBN on general medicine units.2 In a recent survey among leaders in hospital medicine programs, a majority reported early discharge as an important institutional goal.3

Studies of the effectiveness of DCBN initiatives on improving throughput and shortening length of stay (LOS) in adult patients have had mixed results. Computer modeling has supported the idea that earlier inpatient discharges would shorten ED patient boarding time.4

A question of interest for hospitals is if DCBN is a good indicator of shorter LOS, or is DCBN an arbitrary indicator, as morning discharges might just be the result of a delayed discharge of a patient ready for discharge the prior afternoon/evening. Our study objectives were: (1) to determine whether DCBN is associated with a shorter LOS in a pediatric population at an academic medical center, and (2) to examine separately this association in medical and surgical patients given the different provider workflow and patient clinical characteristics in those groups.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and Settings

We included patients 21 years or younger with an inpatient admission to any of the following pediatric medical or surgical services: cardiac surgery, cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, general services, hematology/oncology, nephrology, orthopedics, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, pulmonology, and urology. Patients whose stay did not extend beyond one midnight were excluded because discharge time of day for these short stays was strongly related to the time of admission. We also excluded patients whose stay extended beyond two standard deviations of the average LOS for the discharge service under the assumption that these patients represented atypical circumstances. Finally, we excluded patients who died or left against medical advice. A consortium diagram of all exclusion criteria can be found in Supplemental Figure 1. Discharge data were extracted from the Carolina Database Warehouse, a data repository of the University of North Carolina Health System. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study (IRB 17-0500).

Measures

The outcome of interest was LOS, defined as discharge date and time minus admission date and time, and thus a continuous measure of time in the hospital rather than a number of midnights. Rajkomar et al. used the same definition of LOS.6 The independent variable of interest was whether the discharge occurred before noon. Because discharges between midnight and 8:00

All model covariates were collected at the patient level (Table 1)

Statistical Analysis

Student t tests and χ2 statistics were used to compare baseline characteristics of hospitalizations of patients DCBN and after noon. We used ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models to assess the association between DCBN and LOS. Because DCBN may be correlated with patient characteristics, we used propensity score weighted models. Propensity scores were estimated using a logistic regression predicting DCBN using the variables given in Table 1 (excluding the outcome variable LOS). To estimate the average treatment effect on the entire sample for each model, we weighted each observation by the inverse-probability of treatment as per recent propensity score methods detailed by Garrido et al.9 In the inverse-probability weighted models, we clustered on attending physician to adjust for the autocorrelation caused by unobservable similarities of discharges by the same attending. We tested for multicollinearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF). To test our secondary hypothesis that there was a difference in the relationship between DCBN and LOS based on service type (medical versus surgical), we tested if the service type moderated any of the coefficients using a joint Wald test on the 10 coefficients interacted with the service type.

For our sensitivity analysis, we reran all surgical and medical discharges models changing the LOS outlier exclusion criteria to greater than three and then four standard deviations. Statistical modeling and analysis were completed using Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Our study sample comprised 8,226 pediatric hospitalizations with a LOS mean of 5.10 and a median of 3.91 days respectively (range, 1.25-32.83 days). There were 1,531 (18.6%) DCBNs. Compared to those discharged after noon, patients with DCBN had a higher probability of being surgical patients, having commercial insurance, discharge home with self-care, discharge on the weekend, and discharge from a nonquality improvement unit (Table 1). Patients with DCBN were also more likely to be white, non-Hispanic, and male.

Our propensity score weighted ordinary least score (OLS) LOS regression results are presented in Table 2. In the bivariate analysis, DCBN was associated with an average 0.40 day, or roughly 10 hours, shorter LOS (P < .001). In the multivariate model of all discharges, we found that DCBN was associated with a mean of 0.27 day (P = .010) shorter LOS when compared to discharge in the afternoon when controlling for age, race, ethnicity, weekend discharge, discharge from quality improvement unit, discharge service type, CMI, insurance type, and discharge disposition.

There was no evidence of multicollinearity (mean VIF of 1.14). The Wald test returned an F statistic of 27.50 (P < .001) indicating there was a structural difference in the relationship between LOS and DCBN dependent on discharge service type; thus, we ran separate surgical and medical discharge models to interpret model coefficients for both service types. When we analyzed surgical and medical discharges in separate models, the effect of DCBN on LOS in the medical discharges model was significantly associated with a 0.30 day (P = .017) shorter LOS (Table 2). The association was not significant in the surgical discharges model.

To further test the analysis, we increased the LOS outlier exclusion criteria to three and four standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

The differential effect of DCBN on LOS in surgical and medical discharges suggests that the relationship between DCBN and LOS may be related to provider team workflow. For example, surgical teams may tend to round one time per day early in the morning before spending the entire day in the operating room, and thus completing more early morning discharge orders compared to medical teams. However, if a patient on a surgical service is not ready for discharge first thing in the morning, the patient may be more likely to wait until the following morning for a discharge order. On medical services, physician schedules may allow for more flexibility for rounding and responding with a discharge order when a patient becomes ready; however, medical services may round later in the day compared to surgeons and for a longer period of time, delaying discharges beyond noon that could have been made earlier. Another possibility, given UNC pediatric services are loosely regionalized with surgical patients concentrated more in one unit, is that unit-level differences in how staff processed discharges could have contributed to the difference observed between medical and surgical patients, particularly as there was a unit-level quality improvement effort for decreasing discharge time on one of two medical floors. However, we analyzed for differences based on the discharging unit and found no association. The influence of outliers on the association between DCBN and LOS increases also suggests that this group of children who have extremely long hospital stays might need further exploration.

Our study has some similar and some contrasting results with prior studies in adult patients. Our findings support the modeling literature that suggests DCBN may improve discharge efficiency by shortening patient LOS for some discharges.4 These findings contrast with Rajkomar et al., who reported that DCBN was associated with a longer LOS in adult patients.6 The contrasting findings could be due to differences in pediatric versus adult patients.

Our study has several limitations. While we controlled for observable characteristics using covariates and propensity score weighted analyses, there are likely unobservable characteristics that confound our analysis. We did not measure other factors that may affect discharge time of day such as high occupancy, staffing levels, patient transportation availability, and patient and family preferences. Given these limitations, we caution against interpreting a causal relationship between independent variables and the outcome. Finally, this analysis was conducted at a single tertiary care, academic medical center. The majority of pediatric admissions at this institution are either transferred from other hospitals or scheduled admissions for medical or surgical care. A smaller proportion of discharges are acute, unplanned admissions through our emergency department in children with or without underlying medical complexity. These factors plus the exclusion of observation, extended recovery, and all the less than two-day stays in this study contribute to a relatively higher average LOS. These factors potentially limit generalizability to other care settings. Additionally, the majority of the care teams involve care by resident physicians, and they are often the primary caregivers and write the majority of orders in patient charts such as discharge orders. While we were not able to control for within resident physician similarities between patients, we did control for autocorrelation at the attending level.

CONCLUSION

The results of our study suggest that DCBN is associated with a decreased LOS for medical but not surgical pediatric patients. DCBN may not be an appropriate measure for all services. Further research should be done to identify other feasible but more valid indicators for shorter LOS.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial relationships relative to this article to disclose. The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding

There were no external sources of funding for this work.

Many hospitals and emergency departments (EDs) face challenges posed by overcrowding and hospital throughput. Slow ED throughput has been associated with worse patient outcomes.1 One strategy increasingly employed to improve hospital throughput is to increase the rate of inpatient discharges earlier in the day, which is often defined as discharges before noon (DCBNs). The hypothesis behind DCBN is that earlier hospital discharges will allow for earlier ED admissions and thus mitigate ED overcrowding while optimizing inpatient hospital flow. Previous quality improvement efforts to increase the percentage of DCBNs have been successfully implemented. For example, Wertheimer et al. implemented a process for earlier discharges and reported a 27-percentage point (11% to 38%) increase in DCBN on general medicine units.2 In a recent survey among leaders in hospital medicine programs, a majority reported early discharge as an important institutional goal.3

Studies of the effectiveness of DCBN initiatives on improving throughput and shortening length of stay (LOS) in adult patients have had mixed results. Computer modeling has supported the idea that earlier inpatient discharges would shorten ED patient boarding time.4

A question of interest for hospitals is if DCBN is a good indicator of shorter LOS, or is DCBN an arbitrary indicator, as morning discharges might just be the result of a delayed discharge of a patient ready for discharge the prior afternoon/evening. Our study objectives were: (1) to determine whether DCBN is associated with a shorter LOS in a pediatric population at an academic medical center, and (2) to examine separately this association in medical and surgical patients given the different provider workflow and patient clinical characteristics in those groups.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and Settings

We included patients 21 years or younger with an inpatient admission to any of the following pediatric medical or surgical services: cardiac surgery, cardiology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, general services, hematology/oncology, nephrology, orthopedics, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, pulmonology, and urology. Patients whose stay did not extend beyond one midnight were excluded because discharge time of day for these short stays was strongly related to the time of admission. We also excluded patients whose stay extended beyond two standard deviations of the average LOS for the discharge service under the assumption that these patients represented atypical circumstances. Finally, we excluded patients who died or left against medical advice. A consortium diagram of all exclusion criteria can be found in Supplemental Figure 1. Discharge data were extracted from the Carolina Database Warehouse, a data repository of the University of North Carolina Health System. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study (IRB 17-0500).

Measures

The outcome of interest was LOS, defined as discharge date and time minus admission date and time, and thus a continuous measure of time in the hospital rather than a number of midnights. Rajkomar et al. used the same definition of LOS.6 The independent variable of interest was whether the discharge occurred before noon. Because discharges between midnight and 8:00

All model covariates were collected at the patient level (Table 1)

Statistical Analysis

Student t tests and χ2 statistics were used to compare baseline characteristics of hospitalizations of patients DCBN and after noon. We used ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models to assess the association between DCBN and LOS. Because DCBN may be correlated with patient characteristics, we used propensity score weighted models. Propensity scores were estimated using a logistic regression predicting DCBN using the variables given in Table 1 (excluding the outcome variable LOS). To estimate the average treatment effect on the entire sample for each model, we weighted each observation by the inverse-probability of treatment as per recent propensity score methods detailed by Garrido et al.9 In the inverse-probability weighted models, we clustered on attending physician to adjust for the autocorrelation caused by unobservable similarities of discharges by the same attending. We tested for multicollinearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF). To test our secondary hypothesis that there was a difference in the relationship between DCBN and LOS based on service type (medical versus surgical), we tested if the service type moderated any of the coefficients using a joint Wald test on the 10 coefficients interacted with the service type.

For our sensitivity analysis, we reran all surgical and medical discharges models changing the LOS outlier exclusion criteria to greater than three and then four standard deviations. Statistical modeling and analysis were completed using Stata version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Our study sample comprised 8,226 pediatric hospitalizations with a LOS mean of 5.10 and a median of 3.91 days respectively (range, 1.25-32.83 days). There were 1,531 (18.6%) DCBNs. Compared to those discharged after noon, patients with DCBN had a higher probability of being surgical patients, having commercial insurance, discharge home with self-care, discharge on the weekend, and discharge from a nonquality improvement unit (Table 1). Patients with DCBN were also more likely to be white, non-Hispanic, and male.

Our propensity score weighted ordinary least score (OLS) LOS regression results are presented in Table 2. In the bivariate analysis, DCBN was associated with an average 0.40 day, or roughly 10 hours, shorter LOS (P < .001). In the multivariate model of all discharges, we found that DCBN was associated with a mean of 0.27 day (P = .010) shorter LOS when compared to discharge in the afternoon when controlling for age, race, ethnicity, weekend discharge, discharge from quality improvement unit, discharge service type, CMI, insurance type, and discharge disposition.

There was no evidence of multicollinearity (mean VIF of 1.14). The Wald test returned an F statistic of 27.50 (P < .001) indicating there was a structural difference in the relationship between LOS and DCBN dependent on discharge service type; thus, we ran separate surgical and medical discharge models to interpret model coefficients for both service types. When we analyzed surgical and medical discharges in separate models, the effect of DCBN on LOS in the medical discharges model was significantly associated with a 0.30 day (P = .017) shorter LOS (Table 2). The association was not significant in the surgical discharges model.

To further test the analysis, we increased the LOS outlier exclusion criteria to three and four standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

The differential effect of DCBN on LOS in surgical and medical discharges suggests that the relationship between DCBN and LOS may be related to provider team workflow. For example, surgical teams may tend to round one time per day early in the morning before spending the entire day in the operating room, and thus completing more early morning discharge orders compared to medical teams. However, if a patient on a surgical service is not ready for discharge first thing in the morning, the patient may be more likely to wait until the following morning for a discharge order. On medical services, physician schedules may allow for more flexibility for rounding and responding with a discharge order when a patient becomes ready; however, medical services may round later in the day compared to surgeons and for a longer period of time, delaying discharges beyond noon that could have been made earlier. Another possibility, given UNC pediatric services are loosely regionalized with surgical patients concentrated more in one unit, is that unit-level differences in how staff processed discharges could have contributed to the difference observed between medical and surgical patients, particularly as there was a unit-level quality improvement effort for decreasing discharge time on one of two medical floors. However, we analyzed for differences based on the discharging unit and found no association. The influence of outliers on the association between DCBN and LOS increases also suggests that this group of children who have extremely long hospital stays might need further exploration.

Our study has some similar and some contrasting results with prior studies in adult patients. Our findings support the modeling literature that suggests DCBN may improve discharge efficiency by shortening patient LOS for some discharges.4 These findings contrast with Rajkomar et al., who reported that DCBN was associated with a longer LOS in adult patients.6 The contrasting findings could be due to differences in pediatric versus adult patients.

Our study has several limitations. While we controlled for observable characteristics using covariates and propensity score weighted analyses, there are likely unobservable characteristics that confound our analysis. We did not measure other factors that may affect discharge time of day such as high occupancy, staffing levels, patient transportation availability, and patient and family preferences. Given these limitations, we caution against interpreting a causal relationship between independent variables and the outcome. Finally, this analysis was conducted at a single tertiary care, academic medical center. The majority of pediatric admissions at this institution are either transferred from other hospitals or scheduled admissions for medical or surgical care. A smaller proportion of discharges are acute, unplanned admissions through our emergency department in children with or without underlying medical complexity. These factors plus the exclusion of observation, extended recovery, and all the less than two-day stays in this study contribute to a relatively higher average LOS. These factors potentially limit generalizability to other care settings. Additionally, the majority of the care teams involve care by resident physicians, and they are often the primary caregivers and write the majority of orders in patient charts such as discharge orders. While we were not able to control for within resident physician similarities between patients, we did control for autocorrelation at the attending level.

CONCLUSION

The results of our study suggest that DCBN is associated with a decreased LOS for medical but not surgical pediatric patients. DCBN may not be an appropriate measure for all services. Further research should be done to identify other feasible but more valid indicators for shorter LOS.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial relationships relative to this article to disclose. The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding

There were no external sources of funding for this work.

1. Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):1-10. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00295.x. PubMed

2. Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: an achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210-214. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2154. PubMed

3. Patel H, Fang MC, Mourad M, et al. Hospitalist and internal medicine leaders’ perspectives of early discharge challenges at academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2017;13(6):388-391. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2885. PubMed

4. Powell ES, Khare RK, Venkatesh AK, Van Roo BD, Adams JG, Reinhardt G. The relationship between inpatient discharge timing and emergency department boarding. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(2):186-196. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.06.028. PubMed

5. Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Iturrate E, Bailey M, Hochman K. Discharge before noon: effect on throughput and sustainability. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):664-669. doi:10.1002/jhm.2412. PubMed

6. Rajkomar A, Valencia V, Novelero M, Mourad M, Auerbach A. The association between discharge before noon and length of stay in medical and surgical patients. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):859-861. doi:10.1002/jhm.2529. PubMed

7. Shine D. Discharge before noon: an urban legend. Am J Med. 2015;128(5):445-446. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.12.011. PubMed

8. Sauer B, Brookhart MA, Roy JA, VanderWeele TJ. Covariate selection. In: Velentgas P, Dreyer NA, Nourjah P, Smith SR, Torchia MM, eds. Developing a Protocol for Observational Comparative Effectiveness Research: A User’s Guide. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013. PubMed

9. Garrido MM, Kelley AS, Paris J, et al. Methods for constructing and assessing propensity scores. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(5):1701-1720. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12182. PubMed

10. Maguire P. Do discharge-before-noon Intiatives work? 2016. https://www.todayshospitalist.com/do-discharge-before-noon-initiatives-work/. Accessed April, 2018.

1. Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):1-10. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00295.x. PubMed

2. Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Bailey M, et al. Discharge before noon: an achievable hospital goal. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):210-214. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2154. PubMed

3. Patel H, Fang MC, Mourad M, et al. Hospitalist and internal medicine leaders’ perspectives of early discharge challenges at academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2017;13(6):388-391. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2885. PubMed

4. Powell ES, Khare RK, Venkatesh AK, Van Roo BD, Adams JG, Reinhardt G. The relationship between inpatient discharge timing and emergency department boarding. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(2):186-196. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.06.028. PubMed

5. Wertheimer B, Jacobs RE, Iturrate E, Bailey M, Hochman K. Discharge before noon: effect on throughput and sustainability. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):664-669. doi:10.1002/jhm.2412. PubMed

6. Rajkomar A, Valencia V, Novelero M, Mourad M, Auerbach A. The association between discharge before noon and length of stay in medical and surgical patients. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):859-861. doi:10.1002/jhm.2529. PubMed

7. Shine D. Discharge before noon: an urban legend. Am J Med. 2015;128(5):445-446. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.12.011. PubMed

8. Sauer B, Brookhart MA, Roy JA, VanderWeele TJ. Covariate selection. In: Velentgas P, Dreyer NA, Nourjah P, Smith SR, Torchia MM, eds. Developing a Protocol for Observational Comparative Effectiveness Research: A User’s Guide. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013. PubMed

9. Garrido MM, Kelley AS, Paris J, et al. Methods for constructing and assessing propensity scores. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(5):1701-1720. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12182. PubMed

10. Maguire P. Do discharge-before-noon Intiatives work? 2016. https://www.todayshospitalist.com/do-discharge-before-noon-initiatives-work/. Accessed April, 2018.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine