User login

Nurse Practitioners, Physician Assistants Play Key Roles in Hospitalist Practice

—Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, University of Chicago

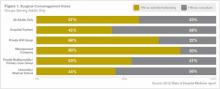

Job One during your first months as a working hospitalist is to acclimate to your hospital and HM group’s procedures. Increasingly, hospitalist teams include nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs); for some new hospitalists, this will require another level of learning on the job. The 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) noted that approximately half of HM groups serving adults and children utilized NPs and/or PAs. Although the report also acknowledged that identifying trends is difficult, the converging factors of aging U.S. demographics and the growing physician shortage indicate that NPs and PAs will become more prevalent in hospital medicine.

Physicians who have not worked alongside NPs or PAs often are unsure of how to approach the working relationship, says Jeanette Kalupa, DNP, ACNP-BC, SFHM, vice president of clinical operations at Hospitalists of Northern Michigan and a member of SHM’s Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant (NP/PA) Committee.

Roles and Scope of Practice

NPs and PAs perform myriad clinical and management responsibilities as hospitalists:

- Coordination of admissions and discharge planning;

- Patient histories, physical examinations, and diagnostic and therapeutic procedures (placing central lines, doing lumbar punctures, etc.);

- Medication orders; and

- Hospital committee work to improve processes of care.

Licensing requirements, physician oversight requirements, and scope of practice vary state to state and hospital to hospital. “If you’ve seen one hospital medicine group, you’ve seen one hospital medicine group”— coined by Mitchell Wilson, MD, SFHM, CMO at Atlanta-based Eagle Hospital Physicians—also applies to the way in which HM groups structure their use of NPs and PAs, says Tracy E. Cardin, ACNP-BC, of the University of Chicago Hospital and chair of the NP/PA Committee. SHM’s website offers information about the scope of practice and best ways to incorporate NPs and PAs into hospitalist practice.

To hospitalists who express anxiety about an NP or PA overstepping bounds and putting the physician’s license at risk, Kalupa reminds them that she, too, has a license that is at risk. When roles are clearly delineated for tasks that NPs and PAs will perform, jeopardizing a license will not be an issue.

Literature supports equivalent outcomes in both primary care and inpatient settings when PAs and NPs are implemented to handle responsibilities within their scope of practice.1,2 Using a PA or NP to handle uncomplicated pneumonia cases, to conduct a stress test, or assemble data for patient rounding, for example, can have a physician multiplier effect, says committee member David A. Friar, MD, SFHM, also a member of the NP/PA Committee. Dr. Friar, based in Traverse City, Mich., works daily with nurse practitioners and physician assistants as part of HNM.

“I think of the healthcare team as a toolbox with which we need to provide care for our patients,” he says. “A screwdriver is not half of a hammer, but it can be the best tool for a certain job. In addition, physicians are often seen as Swiss army knives—that we can do anything. We can make photocopies, but it doesn’t make sense for us to do that. So for cases of simple pneumonia or urinary tract infections, or for following people waiting for discharge, management by an NP or PA makes a lot of sense from an economic standpoint.”

Position Parity

Hospital leadership should set the tone for building a strong multidisciplinary team, Cardin says. Individual physicians can make a difference with the right approach to the working relationship. “If you are going to have successful collaborations with NPs and PAs,” she says, “you have to treat them like a doctor.” This does not mean that the pay structure will be the same, but in areas such as continuing medical education and group socializing, every member of the team should be treated as an equal. That approach makes sense to Dr. Friar, who makes it a point to call every person on the HM team a hospitalist.

He and Kalupa also point out that NPs and PAs can successfully fill team leadership roles. “Physicians need to be willing to accept that the personality traits that made them great clinicians are often not those that one would desire in a team leader,” Dr. Friar says. Using a football analogy, he notes that an important part of being a good team member is to play to other members’ strengths and protect them from their weaknesses. “You don’t have the linebacker run the ball, or the quarterback kick the field goal attempt; you use people’s strengths where they will be most effective for the care of your patients.”

When Conflicts Arise

Successful working relationships between physicians and NP/PAs hinge on clear expectations and the willingness to have difficult conversations, Cardin says. She has practiced as a hospitalist for seven years and prior to that worked in the acute-care setting. As a result, she says, she is quite comfortable seeing patients independently.

Hospitalists new to the group or those who have not worked with NPs before may bristle at that idea, she notes. If a problem arises, such as a perceived encroachment on one’s scope of practice, be willing to address it openly. All relationships are constantly evolving, and it’s important not to overreact.

It’s “just like driving a car,” she says. “If you overcorrect when a wheel comes off the road, you will wreck the car. Sometimes all that’s needed is a small adjustment to manage the problem.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Iglesias B, Ramos F, Serrano B, et al. A randomized controlled trial of nurses vs. doctors in the resolution of acute disease of low complexity in primary care. J Adv Nurs. 2013 March 21. doi: 10.1111/jan.12120 [Epub ahead of print].

- Hoffman LA, Tasota FJ, Zullo TG, et al. Outcomes of care managed by an acute care nurse practitioner/attending physician team in a subacute medical intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14(2):121-130; quiz 131-132.

—Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, University of Chicago

Job One during your first months as a working hospitalist is to acclimate to your hospital and HM group’s procedures. Increasingly, hospitalist teams include nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs); for some new hospitalists, this will require another level of learning on the job. The 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) noted that approximately half of HM groups serving adults and children utilized NPs and/or PAs. Although the report also acknowledged that identifying trends is difficult, the converging factors of aging U.S. demographics and the growing physician shortage indicate that NPs and PAs will become more prevalent in hospital medicine.

Physicians who have not worked alongside NPs or PAs often are unsure of how to approach the working relationship, says Jeanette Kalupa, DNP, ACNP-BC, SFHM, vice president of clinical operations at Hospitalists of Northern Michigan and a member of SHM’s Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant (NP/PA) Committee.

Roles and Scope of Practice

NPs and PAs perform myriad clinical and management responsibilities as hospitalists:

- Coordination of admissions and discharge planning;

- Patient histories, physical examinations, and diagnostic and therapeutic procedures (placing central lines, doing lumbar punctures, etc.);

- Medication orders; and

- Hospital committee work to improve processes of care.

Licensing requirements, physician oversight requirements, and scope of practice vary state to state and hospital to hospital. “If you’ve seen one hospital medicine group, you’ve seen one hospital medicine group”— coined by Mitchell Wilson, MD, SFHM, CMO at Atlanta-based Eagle Hospital Physicians—also applies to the way in which HM groups structure their use of NPs and PAs, says Tracy E. Cardin, ACNP-BC, of the University of Chicago Hospital and chair of the NP/PA Committee. SHM’s website offers information about the scope of practice and best ways to incorporate NPs and PAs into hospitalist practice.

To hospitalists who express anxiety about an NP or PA overstepping bounds and putting the physician’s license at risk, Kalupa reminds them that she, too, has a license that is at risk. When roles are clearly delineated for tasks that NPs and PAs will perform, jeopardizing a license will not be an issue.

Literature supports equivalent outcomes in both primary care and inpatient settings when PAs and NPs are implemented to handle responsibilities within their scope of practice.1,2 Using a PA or NP to handle uncomplicated pneumonia cases, to conduct a stress test, or assemble data for patient rounding, for example, can have a physician multiplier effect, says committee member David A. Friar, MD, SFHM, also a member of the NP/PA Committee. Dr. Friar, based in Traverse City, Mich., works daily with nurse practitioners and physician assistants as part of HNM.

“I think of the healthcare team as a toolbox with which we need to provide care for our patients,” he says. “A screwdriver is not half of a hammer, but it can be the best tool for a certain job. In addition, physicians are often seen as Swiss army knives—that we can do anything. We can make photocopies, but it doesn’t make sense for us to do that. So for cases of simple pneumonia or urinary tract infections, or for following people waiting for discharge, management by an NP or PA makes a lot of sense from an economic standpoint.”

Position Parity

Hospital leadership should set the tone for building a strong multidisciplinary team, Cardin says. Individual physicians can make a difference with the right approach to the working relationship. “If you are going to have successful collaborations with NPs and PAs,” she says, “you have to treat them like a doctor.” This does not mean that the pay structure will be the same, but in areas such as continuing medical education and group socializing, every member of the team should be treated as an equal. That approach makes sense to Dr. Friar, who makes it a point to call every person on the HM team a hospitalist.

He and Kalupa also point out that NPs and PAs can successfully fill team leadership roles. “Physicians need to be willing to accept that the personality traits that made them great clinicians are often not those that one would desire in a team leader,” Dr. Friar says. Using a football analogy, he notes that an important part of being a good team member is to play to other members’ strengths and protect them from their weaknesses. “You don’t have the linebacker run the ball, or the quarterback kick the field goal attempt; you use people’s strengths where they will be most effective for the care of your patients.”

When Conflicts Arise

Successful working relationships between physicians and NP/PAs hinge on clear expectations and the willingness to have difficult conversations, Cardin says. She has practiced as a hospitalist for seven years and prior to that worked in the acute-care setting. As a result, she says, she is quite comfortable seeing patients independently.

Hospitalists new to the group or those who have not worked with NPs before may bristle at that idea, she notes. If a problem arises, such as a perceived encroachment on one’s scope of practice, be willing to address it openly. All relationships are constantly evolving, and it’s important not to overreact.

It’s “just like driving a car,” she says. “If you overcorrect when a wheel comes off the road, you will wreck the car. Sometimes all that’s needed is a small adjustment to manage the problem.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Iglesias B, Ramos F, Serrano B, et al. A randomized controlled trial of nurses vs. doctors in the resolution of acute disease of low complexity in primary care. J Adv Nurs. 2013 March 21. doi: 10.1111/jan.12120 [Epub ahead of print].

- Hoffman LA, Tasota FJ, Zullo TG, et al. Outcomes of care managed by an acute care nurse practitioner/attending physician team in a subacute medical intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14(2):121-130; quiz 131-132.

—Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, University of Chicago

Job One during your first months as a working hospitalist is to acclimate to your hospital and HM group’s procedures. Increasingly, hospitalist teams include nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs); for some new hospitalists, this will require another level of learning on the job. The 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) noted that approximately half of HM groups serving adults and children utilized NPs and/or PAs. Although the report also acknowledged that identifying trends is difficult, the converging factors of aging U.S. demographics and the growing physician shortage indicate that NPs and PAs will become more prevalent in hospital medicine.

Physicians who have not worked alongside NPs or PAs often are unsure of how to approach the working relationship, says Jeanette Kalupa, DNP, ACNP-BC, SFHM, vice president of clinical operations at Hospitalists of Northern Michigan and a member of SHM’s Nurse Practitioner/Physician Assistant (NP/PA) Committee.

Roles and Scope of Practice

NPs and PAs perform myriad clinical and management responsibilities as hospitalists:

- Coordination of admissions and discharge planning;

- Patient histories, physical examinations, and diagnostic and therapeutic procedures (placing central lines, doing lumbar punctures, etc.);

- Medication orders; and

- Hospital committee work to improve processes of care.

Licensing requirements, physician oversight requirements, and scope of practice vary state to state and hospital to hospital. “If you’ve seen one hospital medicine group, you’ve seen one hospital medicine group”— coined by Mitchell Wilson, MD, SFHM, CMO at Atlanta-based Eagle Hospital Physicians—also applies to the way in which HM groups structure their use of NPs and PAs, says Tracy E. Cardin, ACNP-BC, of the University of Chicago Hospital and chair of the NP/PA Committee. SHM’s website offers information about the scope of practice and best ways to incorporate NPs and PAs into hospitalist practice.

To hospitalists who express anxiety about an NP or PA overstepping bounds and putting the physician’s license at risk, Kalupa reminds them that she, too, has a license that is at risk. When roles are clearly delineated for tasks that NPs and PAs will perform, jeopardizing a license will not be an issue.

Literature supports equivalent outcomes in both primary care and inpatient settings when PAs and NPs are implemented to handle responsibilities within their scope of practice.1,2 Using a PA or NP to handle uncomplicated pneumonia cases, to conduct a stress test, or assemble data for patient rounding, for example, can have a physician multiplier effect, says committee member David A. Friar, MD, SFHM, also a member of the NP/PA Committee. Dr. Friar, based in Traverse City, Mich., works daily with nurse practitioners and physician assistants as part of HNM.

“I think of the healthcare team as a toolbox with which we need to provide care for our patients,” he says. “A screwdriver is not half of a hammer, but it can be the best tool for a certain job. In addition, physicians are often seen as Swiss army knives—that we can do anything. We can make photocopies, but it doesn’t make sense for us to do that. So for cases of simple pneumonia or urinary tract infections, or for following people waiting for discharge, management by an NP or PA makes a lot of sense from an economic standpoint.”

Position Parity

Hospital leadership should set the tone for building a strong multidisciplinary team, Cardin says. Individual physicians can make a difference with the right approach to the working relationship. “If you are going to have successful collaborations with NPs and PAs,” she says, “you have to treat them like a doctor.” This does not mean that the pay structure will be the same, but in areas such as continuing medical education and group socializing, every member of the team should be treated as an equal. That approach makes sense to Dr. Friar, who makes it a point to call every person on the HM team a hospitalist.

He and Kalupa also point out that NPs and PAs can successfully fill team leadership roles. “Physicians need to be willing to accept that the personality traits that made them great clinicians are often not those that one would desire in a team leader,” Dr. Friar says. Using a football analogy, he notes that an important part of being a good team member is to play to other members’ strengths and protect them from their weaknesses. “You don’t have the linebacker run the ball, or the quarterback kick the field goal attempt; you use people’s strengths where they will be most effective for the care of your patients.”

When Conflicts Arise

Successful working relationships between physicians and NP/PAs hinge on clear expectations and the willingness to have difficult conversations, Cardin says. She has practiced as a hospitalist for seven years and prior to that worked in the acute-care setting. As a result, she says, she is quite comfortable seeing patients independently.

Hospitalists new to the group or those who have not worked with NPs before may bristle at that idea, she notes. If a problem arises, such as a perceived encroachment on one’s scope of practice, be willing to address it openly. All relationships are constantly evolving, and it’s important not to overreact.

It’s “just like driving a car,” she says. “If you overcorrect when a wheel comes off the road, you will wreck the car. Sometimes all that’s needed is a small adjustment to manage the problem.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Iglesias B, Ramos F, Serrano B, et al. A randomized controlled trial of nurses vs. doctors in the resolution of acute disease of low complexity in primary care. J Adv Nurs. 2013 March 21. doi: 10.1111/jan.12120 [Epub ahead of print].

- Hoffman LA, Tasota FJ, Zullo TG, et al. Outcomes of care managed by an acute care nurse practitioner/attending physician team in a subacute medical intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14(2):121-130; quiz 131-132.

Should Skyrocketing Health Care Costs Concern Hospitalists?

Median hospitalist compensation has grown steadily over the past decade, but physicians aren’t immune to the sting of accelerated premiums, copays, and contributions imposed by health insurers.

According to the Hay Group’s 2011 Physician Compensation Survey, the number of physicians who contributing to health insurance premiums increased to 68% in 2011 from 58% in 2010. The survey showed only 9% of physicians did not pay anything for medical coverage, down from 19% in 2010.

Moreover, the expected physician contribution was between 1% and 25% of the premium.

Dan Fuller, president and cofounder of Alpharetta, Ga.-based IN Compass Health, has noticed an uptick in candidates’ interest in their health-care benefits. “Especially for physicians who have families, health benefits have become one of the top issues in recruiting,” the SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member says.

Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America in Nashville, Tenn., reports that he is seeing an upward trend in employees’ contributions to premiums and out-of-pocket costs. He’s also observed colleagues becoming more selective when choosing their own health-care plans and how they use those plans.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Median hospitalist compensation has grown steadily over the past decade, but physicians aren’t immune to the sting of accelerated premiums, copays, and contributions imposed by health insurers.

According to the Hay Group’s 2011 Physician Compensation Survey, the number of physicians who contributing to health insurance premiums increased to 68% in 2011 from 58% in 2010. The survey showed only 9% of physicians did not pay anything for medical coverage, down from 19% in 2010.

Moreover, the expected physician contribution was between 1% and 25% of the premium.

Dan Fuller, president and cofounder of Alpharetta, Ga.-based IN Compass Health, has noticed an uptick in candidates’ interest in their health-care benefits. “Especially for physicians who have families, health benefits have become one of the top issues in recruiting,” the SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member says.

Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America in Nashville, Tenn., reports that he is seeing an upward trend in employees’ contributions to premiums and out-of-pocket costs. He’s also observed colleagues becoming more selective when choosing their own health-care plans and how they use those plans.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Median hospitalist compensation has grown steadily over the past decade, but physicians aren’t immune to the sting of accelerated premiums, copays, and contributions imposed by health insurers.

According to the Hay Group’s 2011 Physician Compensation Survey, the number of physicians who contributing to health insurance premiums increased to 68% in 2011 from 58% in 2010. The survey showed only 9% of physicians did not pay anything for medical coverage, down from 19% in 2010.

Moreover, the expected physician contribution was between 1% and 25% of the premium.

Dan Fuller, president and cofounder of Alpharetta, Ga.-based IN Compass Health, has noticed an uptick in candidates’ interest in their health-care benefits. “Especially for physicians who have families, health benefits have become one of the top issues in recruiting,” the SHM Practice Analysis Committee (PAC) member says.

Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America in Nashville, Tenn., reports that he is seeing an upward trend in employees’ contributions to premiums and out-of-pocket costs. He’s also observed colleagues becoming more selective when choosing their own health-care plans and how they use those plans.

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

AUDIO EXCLUSIVE: No End in Sight for Medicare Reimbursement's Downward Trend

Click here to listen to Dr. Frederickson's take on Medicare reimbursement

Click here to listen to Dr. Frederickson's take on Medicare reimbursement

Click here to listen to Dr. Frederickson's take on Medicare reimbursement

Hospitalists Can Address Causes of Skyrocketing Health Care Costs

Alarms about our nation’s health-care costs have been sounding for well over a decade. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), spending on U.S. health care doubled between 1999 and 2011, climbing to $2.7 trillion from $1.3 trillion, and now represents 17.9% of the United States’ GDP.1

“The medical care system is bankrupting the country,” Paul B. Ginsburg, PhD, president of the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), based in Washington, D.C., says bluntly. A four-decade-long upward spending trend is “unsustainable,” he wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine with Chapin White, PhD, a senior health researcher at HSC.2

Recent reports suggest that rising premiums and out-of-pocket costs are rendering the price of health care untenable for the average consumer. A 2011 RAND Corp. study found that, for the average American family, the rate of increased costs for health care had outpaced growth in earnings from 1999 to 2009.3 And last year, for the first time, the cost of health care for a typical American family of four surpassed $20,000, the annual Milliman Medical Index reported.4

Should hospitalists be concerned, professionally and personally, about these trends? Absolutely, say hospitalist leaders who spoke with The Hospitalist. HM clinicians have much to contribute at both the macro level (addressing systemic causes of overutilization through quality improvement and other initiatives) and at the micro level, by understanding their personal contributions and by engaging patients and their families in shared decision-making.

But getting at and addressing the root causes of rising health-care costs, according to health-care policy analysts and veteran hospitalists, will require major shifts in thinking and processes.

Contributors to Rising Costs

It’s difficult to pinpoint the root causes of the recent surge in health-care costs. Victor Fuchs, emeritus professor of economics and health research and policy at Stanford University, points to the U.S.’ high administrative costs and complicated billing systems.5 A fragmented, nontransparent system for negotiating fees between insurers and providers also plays a role, as demonstrated in a Consumer Reports investigation into geographic variations in costs for common tests and procedures. A complete blood count might be as low as $15 or as high as $105; a colonoscopy ranges from $800 to $3,160.6

Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM, an SHM Public Policy Committee member and AMA delegate, says rising costs are a provider-specific issue. He challenges colleagues to take an honest look at their own practice patterns to assess whether they’re contributing to overuse of resources (see “A Lesson in Change,”).

“The culture of practice has developed so that this is not going to change overnight,” says Dr. Flansbaum, director of hospitalist services at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. That’s because many physicians fail to view their own decisions as a problem. For example, says Dr. Flansbaum, “an oncologist may not identify a third round of chemotherapy as an embodiment of the problem, or a gastroenterologist might not embody the colonoscopy at Year Four instead of Year Five as the problem. We must come to grips with the usual mindset, look in the mirror, and admit, ‘Maybe we are part of the problem.’”

—Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM

Potential Solutions

Hospitalists, intensivists, and ED clinicians are tasked with finding a balance between being prudent stewards of resources and staying within a comfort zone that promotes patient safety. SHM supports the goals of the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to reduce waste by curtailing duplicative and unnecessary care (see “Better Choices, Better Care,” March 2013). Also included in the campaign (www.ChoosingWisely.org) are the American College of Physicians’ recommendations against low-value testing (e.g. obtaining imaging studies in patients with nonspecific low back pain).

“Those recommendations are not going to solve our health spending problem,” says White, “but they are part of a broader move to give permission to clinicians, based on evidence, to follow more conservative practice patterns.”

Still, counters David I. Auerbach, PhD, a health economist at RAND in Boston and author of the RAND study, “there’s another value to these tests that the cost-effectiveness equations do not always consider, which is, they can bring peace of mind. We’re trying to nudge patients down the pathway that we think is best for them without rationing care. That’s a delicate balance.”

Dr. Flansbaum says SHM’s Public Policy Committee has discussed a variety of issues related to rising costs, although the group has not directly tackled advice in the form of a white paper. He suggests some ways that hospitalists can address cost savings:

- Involve patients in shared decision-making, and discuss the evidence against unnecessary testing;

- Utilize generic medications on discharge, when available, especially if patients are uninsured or have limited drug coverage with their insurance plans;

- Use palliative care whenever appropriate; and

- Adhere to transitional-care standards.

On the macro level, HM has “always been the specialty invited to champion the important discussion relating to resource utilization, and the evidence-based medicine driving that resource utilization,” says Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA) in Nashville, Tenn. He points to SHM’s leadership with Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost) as one example of addressing the utilization of resources in caring for older adults (see “Resources for Improving Transitions in Care,”).

What else can hospitalists do? Going forward, says Dan Fuller, president and co-founder of IN Compass Health in Alpharetta, Ga., it might be a good idea for the SHM Practice Analysis Committee, of which he’s a member, to look at its possible role in the issue.

—Dr. Frederickson

Embrace Reality

Whatever the downstream developments around the Affordable Care Act, Dr. Ginsburg is “confident” that Medicare policies will continue in a direction of reduced reimbursements. Thomas Frederickson, MD, FACP, FHM, MBA, medical director of the hospital medicine service at Alegent Health in Omaha, Neb., agrees with such an assessment. He also believes that hospitalists are in a prime position to improve care delivery at less cost. To do so, though, requires deliberate partnership-building with outpatient providers to better bridge the transitions of care.

At his institution, Dr. Frederickson says, hospitalists invite themselves to primary-care physicians’ (PCP) meetings. This facilitates rapport so that calls to PCPs at discharge not only communicate essential clinical information, but also build confidence in the hospitalists’ care of their patients. As hospitalists demonstrate value, they must intentionally put metrics in place so that administrators appreciate the need to keep the census at a certain level, Dr. Frederickson says.

“We need the time to make these calls, to sit down with families,” he says. “This adds value to our health system and to society at large.”

SHM does a good job, says Dr. Frost, of being part of the conversation as the hospital C-suite focuses more on episodes of care.

“The intensity of that discussion is getting dialed up and will be driven more by government and the payors,” he adds. The challenge going forward will be to bridge those arenas just outside the acute episode of care, where hospitalists have ownership of processes, to those where they do not have as much control. If payors apply broader definitions to the episode of care, Dr. Frost says, hospitalists might be “invited to play an increasing role, that of ‘transitionist.’”

And in that context, he says, hospitalists need to look at length of stay with a new lens.

Partnership-building will become more important as the definition of “episode of care” expands beyond the hospital stay to the post-acute setting.

“Including post-acute care in the episode of care is a core aspect of the whole” value-based purchasing approach, Dr. Ginsburg says. “Hospitals [and hospitalists] will be wise to opt for the model with the greatest potential to reduce costs, particularly costs incurred by other providers.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditures 2011 highlights. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013. costs how much? Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/ 2012/07/that-ct-scan-costs-how-much/index.htm. Accessed Aug. 2, 2012.

- White C, Ginsburg PB. Slower growth in Medicare spending—is this the new normal? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1073-1075.

- Auerbach DI, Kellermann AL. A decade of health care cost growth has wiped out real income gains for an average US family. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(9):1630-1636.

- Milliman Inc. 2012 Milliman Medical Index. Milliman Inc. website. Available at: http://publications.milliman.com/periodicals/mmi/pdfs/milliman-medical-index-2012.pdf. Accessed Aug. 1, 2012.

- Kolata G. Knotty challenges in health care costs. The New York Times website. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/06/health/policy/an-interview-with-victor-fuchs-on-health-care-costs.html. Accessed March 8, 2012.

- Consumer Reports. That CT scan costs how much? Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/ 2012/07/that-ct-scan-costs-how-much/index.htm.

Alarms about our nation’s health-care costs have been sounding for well over a decade. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), spending on U.S. health care doubled between 1999 and 2011, climbing to $2.7 trillion from $1.3 trillion, and now represents 17.9% of the United States’ GDP.1

“The medical care system is bankrupting the country,” Paul B. Ginsburg, PhD, president of the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), based in Washington, D.C., says bluntly. A four-decade-long upward spending trend is “unsustainable,” he wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine with Chapin White, PhD, a senior health researcher at HSC.2

Recent reports suggest that rising premiums and out-of-pocket costs are rendering the price of health care untenable for the average consumer. A 2011 RAND Corp. study found that, for the average American family, the rate of increased costs for health care had outpaced growth in earnings from 1999 to 2009.3 And last year, for the first time, the cost of health care for a typical American family of four surpassed $20,000, the annual Milliman Medical Index reported.4

Should hospitalists be concerned, professionally and personally, about these trends? Absolutely, say hospitalist leaders who spoke with The Hospitalist. HM clinicians have much to contribute at both the macro level (addressing systemic causes of overutilization through quality improvement and other initiatives) and at the micro level, by understanding their personal contributions and by engaging patients and their families in shared decision-making.

But getting at and addressing the root causes of rising health-care costs, according to health-care policy analysts and veteran hospitalists, will require major shifts in thinking and processes.

Contributors to Rising Costs

It’s difficult to pinpoint the root causes of the recent surge in health-care costs. Victor Fuchs, emeritus professor of economics and health research and policy at Stanford University, points to the U.S.’ high administrative costs and complicated billing systems.5 A fragmented, nontransparent system for negotiating fees between insurers and providers also plays a role, as demonstrated in a Consumer Reports investigation into geographic variations in costs for common tests and procedures. A complete blood count might be as low as $15 or as high as $105; a colonoscopy ranges from $800 to $3,160.6

Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM, an SHM Public Policy Committee member and AMA delegate, says rising costs are a provider-specific issue. He challenges colleagues to take an honest look at their own practice patterns to assess whether they’re contributing to overuse of resources (see “A Lesson in Change,”).

“The culture of practice has developed so that this is not going to change overnight,” says Dr. Flansbaum, director of hospitalist services at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. That’s because many physicians fail to view their own decisions as a problem. For example, says Dr. Flansbaum, “an oncologist may not identify a third round of chemotherapy as an embodiment of the problem, or a gastroenterologist might not embody the colonoscopy at Year Four instead of Year Five as the problem. We must come to grips with the usual mindset, look in the mirror, and admit, ‘Maybe we are part of the problem.’”

—Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM

Potential Solutions

Hospitalists, intensivists, and ED clinicians are tasked with finding a balance between being prudent stewards of resources and staying within a comfort zone that promotes patient safety. SHM supports the goals of the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to reduce waste by curtailing duplicative and unnecessary care (see “Better Choices, Better Care,” March 2013). Also included in the campaign (www.ChoosingWisely.org) are the American College of Physicians’ recommendations against low-value testing (e.g. obtaining imaging studies in patients with nonspecific low back pain).

“Those recommendations are not going to solve our health spending problem,” says White, “but they are part of a broader move to give permission to clinicians, based on evidence, to follow more conservative practice patterns.”

Still, counters David I. Auerbach, PhD, a health economist at RAND in Boston and author of the RAND study, “there’s another value to these tests that the cost-effectiveness equations do not always consider, which is, they can bring peace of mind. We’re trying to nudge patients down the pathway that we think is best for them without rationing care. That’s a delicate balance.”

Dr. Flansbaum says SHM’s Public Policy Committee has discussed a variety of issues related to rising costs, although the group has not directly tackled advice in the form of a white paper. He suggests some ways that hospitalists can address cost savings:

- Involve patients in shared decision-making, and discuss the evidence against unnecessary testing;

- Utilize generic medications on discharge, when available, especially if patients are uninsured or have limited drug coverage with their insurance plans;

- Use palliative care whenever appropriate; and

- Adhere to transitional-care standards.

On the macro level, HM has “always been the specialty invited to champion the important discussion relating to resource utilization, and the evidence-based medicine driving that resource utilization,” says Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA) in Nashville, Tenn. He points to SHM’s leadership with Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost) as one example of addressing the utilization of resources in caring for older adults (see “Resources for Improving Transitions in Care,”).

What else can hospitalists do? Going forward, says Dan Fuller, president and co-founder of IN Compass Health in Alpharetta, Ga., it might be a good idea for the SHM Practice Analysis Committee, of which he’s a member, to look at its possible role in the issue.

—Dr. Frederickson

Embrace Reality

Whatever the downstream developments around the Affordable Care Act, Dr. Ginsburg is “confident” that Medicare policies will continue in a direction of reduced reimbursements. Thomas Frederickson, MD, FACP, FHM, MBA, medical director of the hospital medicine service at Alegent Health in Omaha, Neb., agrees with such an assessment. He also believes that hospitalists are in a prime position to improve care delivery at less cost. To do so, though, requires deliberate partnership-building with outpatient providers to better bridge the transitions of care.

At his institution, Dr. Frederickson says, hospitalists invite themselves to primary-care physicians’ (PCP) meetings. This facilitates rapport so that calls to PCPs at discharge not only communicate essential clinical information, but also build confidence in the hospitalists’ care of their patients. As hospitalists demonstrate value, they must intentionally put metrics in place so that administrators appreciate the need to keep the census at a certain level, Dr. Frederickson says.

“We need the time to make these calls, to sit down with families,” he says. “This adds value to our health system and to society at large.”

SHM does a good job, says Dr. Frost, of being part of the conversation as the hospital C-suite focuses more on episodes of care.

“The intensity of that discussion is getting dialed up and will be driven more by government and the payors,” he adds. The challenge going forward will be to bridge those arenas just outside the acute episode of care, where hospitalists have ownership of processes, to those where they do not have as much control. If payors apply broader definitions to the episode of care, Dr. Frost says, hospitalists might be “invited to play an increasing role, that of ‘transitionist.’”

And in that context, he says, hospitalists need to look at length of stay with a new lens.

Partnership-building will become more important as the definition of “episode of care” expands beyond the hospital stay to the post-acute setting.

“Including post-acute care in the episode of care is a core aspect of the whole” value-based purchasing approach, Dr. Ginsburg says. “Hospitals [and hospitalists] will be wise to opt for the model with the greatest potential to reduce costs, particularly costs incurred by other providers.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditures 2011 highlights. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013. costs how much? Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/ 2012/07/that-ct-scan-costs-how-much/index.htm. Accessed Aug. 2, 2012.

- White C, Ginsburg PB. Slower growth in Medicare spending—is this the new normal? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1073-1075.

- Auerbach DI, Kellermann AL. A decade of health care cost growth has wiped out real income gains for an average US family. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(9):1630-1636.

- Milliman Inc. 2012 Milliman Medical Index. Milliman Inc. website. Available at: http://publications.milliman.com/periodicals/mmi/pdfs/milliman-medical-index-2012.pdf. Accessed Aug. 1, 2012.

- Kolata G. Knotty challenges in health care costs. The New York Times website. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/06/health/policy/an-interview-with-victor-fuchs-on-health-care-costs.html. Accessed March 8, 2012.

- Consumer Reports. That CT scan costs how much? Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/ 2012/07/that-ct-scan-costs-how-much/index.htm.

Alarms about our nation’s health-care costs have been sounding for well over a decade. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), spending on U.S. health care doubled between 1999 and 2011, climbing to $2.7 trillion from $1.3 trillion, and now represents 17.9% of the United States’ GDP.1

“The medical care system is bankrupting the country,” Paul B. Ginsburg, PhD, president of the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC), based in Washington, D.C., says bluntly. A four-decade-long upward spending trend is “unsustainable,” he wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine with Chapin White, PhD, a senior health researcher at HSC.2

Recent reports suggest that rising premiums and out-of-pocket costs are rendering the price of health care untenable for the average consumer. A 2011 RAND Corp. study found that, for the average American family, the rate of increased costs for health care had outpaced growth in earnings from 1999 to 2009.3 And last year, for the first time, the cost of health care for a typical American family of four surpassed $20,000, the annual Milliman Medical Index reported.4

Should hospitalists be concerned, professionally and personally, about these trends? Absolutely, say hospitalist leaders who spoke with The Hospitalist. HM clinicians have much to contribute at both the macro level (addressing systemic causes of overutilization through quality improvement and other initiatives) and at the micro level, by understanding their personal contributions and by engaging patients and their families in shared decision-making.

But getting at and addressing the root causes of rising health-care costs, according to health-care policy analysts and veteran hospitalists, will require major shifts in thinking and processes.

Contributors to Rising Costs

It’s difficult to pinpoint the root causes of the recent surge in health-care costs. Victor Fuchs, emeritus professor of economics and health research and policy at Stanford University, points to the U.S.’ high administrative costs and complicated billing systems.5 A fragmented, nontransparent system for negotiating fees between insurers and providers also plays a role, as demonstrated in a Consumer Reports investigation into geographic variations in costs for common tests and procedures. A complete blood count might be as low as $15 or as high as $105; a colonoscopy ranges from $800 to $3,160.6

Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM, an SHM Public Policy Committee member and AMA delegate, says rising costs are a provider-specific issue. He challenges colleagues to take an honest look at their own practice patterns to assess whether they’re contributing to overuse of resources (see “A Lesson in Change,”).

“The culture of practice has developed so that this is not going to change overnight,” says Dr. Flansbaum, director of hospitalist services at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. That’s because many physicians fail to view their own decisions as a problem. For example, says Dr. Flansbaum, “an oncologist may not identify a third round of chemotherapy as an embodiment of the problem, or a gastroenterologist might not embody the colonoscopy at Year Four instead of Year Five as the problem. We must come to grips with the usual mindset, look in the mirror, and admit, ‘Maybe we are part of the problem.’”

—Bradley Flansbaum, DO, MPH, SFHM

Potential Solutions

Hospitalists, intensivists, and ED clinicians are tasked with finding a balance between being prudent stewards of resources and staying within a comfort zone that promotes patient safety. SHM supports the goals of the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign, which aims to reduce waste by curtailing duplicative and unnecessary care (see “Better Choices, Better Care,” March 2013). Also included in the campaign (www.ChoosingWisely.org) are the American College of Physicians’ recommendations against low-value testing (e.g. obtaining imaging studies in patients with nonspecific low back pain).

“Those recommendations are not going to solve our health spending problem,” says White, “but they are part of a broader move to give permission to clinicians, based on evidence, to follow more conservative practice patterns.”

Still, counters David I. Auerbach, PhD, a health economist at RAND in Boston and author of the RAND study, “there’s another value to these tests that the cost-effectiveness equations do not always consider, which is, they can bring peace of mind. We’re trying to nudge patients down the pathway that we think is best for them without rationing care. That’s a delicate balance.”

Dr. Flansbaum says SHM’s Public Policy Committee has discussed a variety of issues related to rising costs, although the group has not directly tackled advice in the form of a white paper. He suggests some ways that hospitalists can address cost savings:

- Involve patients in shared decision-making, and discuss the evidence against unnecessary testing;

- Utilize generic medications on discharge, when available, especially if patients are uninsured or have limited drug coverage with their insurance plans;

- Use palliative care whenever appropriate; and

- Adhere to transitional-care standards.

On the macro level, HM has “always been the specialty invited to champion the important discussion relating to resource utilization, and the evidence-based medicine driving that resource utilization,” says Christopher Frost, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA) in Nashville, Tenn. He points to SHM’s leadership with Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost) as one example of addressing the utilization of resources in caring for older adults (see “Resources for Improving Transitions in Care,”).

What else can hospitalists do? Going forward, says Dan Fuller, president and co-founder of IN Compass Health in Alpharetta, Ga., it might be a good idea for the SHM Practice Analysis Committee, of which he’s a member, to look at its possible role in the issue.

—Dr. Frederickson

Embrace Reality

Whatever the downstream developments around the Affordable Care Act, Dr. Ginsburg is “confident” that Medicare policies will continue in a direction of reduced reimbursements. Thomas Frederickson, MD, FACP, FHM, MBA, medical director of the hospital medicine service at Alegent Health in Omaha, Neb., agrees with such an assessment. He also believes that hospitalists are in a prime position to improve care delivery at less cost. To do so, though, requires deliberate partnership-building with outpatient providers to better bridge the transitions of care.

At his institution, Dr. Frederickson says, hospitalists invite themselves to primary-care physicians’ (PCP) meetings. This facilitates rapport so that calls to PCPs at discharge not only communicate essential clinical information, but also build confidence in the hospitalists’ care of their patients. As hospitalists demonstrate value, they must intentionally put metrics in place so that administrators appreciate the need to keep the census at a certain level, Dr. Frederickson says.

“We need the time to make these calls, to sit down with families,” he says. “This adds value to our health system and to society at large.”

SHM does a good job, says Dr. Frost, of being part of the conversation as the hospital C-suite focuses more on episodes of care.

“The intensity of that discussion is getting dialed up and will be driven more by government and the payors,” he adds. The challenge going forward will be to bridge those arenas just outside the acute episode of care, where hospitalists have ownership of processes, to those where they do not have as much control. If payors apply broader definitions to the episode of care, Dr. Frost says, hospitalists might be “invited to play an increasing role, that of ‘transitionist.’”

And in that context, he says, hospitalists need to look at length of stay with a new lens.

Partnership-building will become more important as the definition of “episode of care” expands beyond the hospital stay to the post-acute setting.

“Including post-acute care in the episode of care is a core aspect of the whole” value-based purchasing approach, Dr. Ginsburg says. “Hospitals [and hospitalists] will be wise to opt for the model with the greatest potential to reduce costs, particularly costs incurred by other providers.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

References

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditures 2011 highlights. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/Downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2013. costs how much? Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/ 2012/07/that-ct-scan-costs-how-much/index.htm. Accessed Aug. 2, 2012.

- White C, Ginsburg PB. Slower growth in Medicare spending—is this the new normal? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1073-1075.

- Auerbach DI, Kellermann AL. A decade of health care cost growth has wiped out real income gains for an average US family. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(9):1630-1636.

- Milliman Inc. 2012 Milliman Medical Index. Milliman Inc. website. Available at: http://publications.milliman.com/periodicals/mmi/pdfs/milliman-medical-index-2012.pdf. Accessed Aug. 1, 2012.

- Kolata G. Knotty challenges in health care costs. The New York Times website. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/06/health/policy/an-interview-with-victor-fuchs-on-health-care-costs.html. Accessed March 8, 2012.

- Consumer Reports. That CT scan costs how much? Consumer Reports website. Available at: http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/magazine/ 2012/07/that-ct-scan-costs-how-much/index.htm.

Hospitalists Can Get Ahead Through Quality and Patient Safety Initiatives

Are you a hospitalist who, on daily rounds, often thinks, “There’s got to be a better way to do this”? You might be just the type of person who can carve a niche for yourself in hospital quality and patient safety—and advance your career in the process.

Successful navigation of the quality-improvement (QI) and patient-safety domains, according to three veteran hospitalists, requires an initial passion and an incremental approach. Now is an especially good time, they agree, for young hospitalists to engage in these types of initiatives.

Why Do It?

In her capacity as president of the Mid-Atlantic Business Unit for Brentwood, Tenn.-based CogentHMG, Julia Wright, MD, SFHM, FACP, often encourages young recruits to consider participation in QI and patient-safety initiatives. She admits that the transition from residency to a busy HM practice, with its higher patient volumes and a faster pace, can be daunting at first. Still, she tries to cultivate interest in initiatives and establish a realistic timeframe for involvement.

There are many reasons to consider this as a career step. Dr. Wright says that quality and patient safety dovetail with hospitalists’ initial reasons for choosing medicine: to improve patients’ lives.

Janet Nagamine, RN, MD, SFHM, former patient safety officer and assistant chief of quality at Kaiser Permanente in Santa Clara, Calif., describes the fit this way: “I might be a good doctor, but as a hospitalist, I rely on many others within the system to deliver, so my patients can’t get good care until the entire system is running well,” she says. “There are all kinds of opportunities to fix our [hospital] system, and I really believe that hospitalists cannot separate themselves from that engagement.”

Elizabeth Gundersen, MD, FHM, of Fort Lauderdale, Fla., agrees that it’s a natural step to think about the ways to make a difference on a larger level. At her former institution, the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Medical School in Worcester, she parlayed her interest in QI to work her way up from ground-level hospitalist to associate chief of her division and quality officer for the hospital. “Physicians get a lot of satisfaction from helping individual patients,” she says. “One thing I really liked about getting involved with quality improvement was being able to make a difference for patients on a systems level.”

An Incremental Path

The path to her current position began with a very specific issue for Dr. Nagamine, an SHM board member who also serves as a Project BOOST co-investigator. “Although I have been doing patient safety since before they had a name for it, I didn’t start out saying that I wanted a career in quality and safety,” she says. “I was trying to take better care of my patients with diabetes, but controlling their glucose was extremely challenging because all the related variables—timing and amount of their insulin dosage, when and how much they had eaten—were charted in different places. This made it hard to adjust their insulin appropriately.”

It quickly became clear to Dr. Nagamine that the solution had to be systemic. She realized that something as basic as taking care of her patients with diabetes required multiple departments (i.e. dietary, nursing, and pharmacy) to furnish information in an integrated manner. So she joined the diabetes committee and went to work on the issue. She helped devise a flow chart that could be used by all relevant departments. A further evolution on the path emanated from one of her patients receiving the wrong medication. She joined the medication safety committee, became chair, “and the next thing you know, I’m in charge of patient safety, and an assistant chief of quality.”

Training Is Necessary

QI and patient-safety methodologies have become sophisticated disciplines in the past two decades, Dr. Wright says. Access to training in QI basics now is readily available to early-career hospitalists. For example, CogentHMG offers program support for QI so that anyone interested “doesn’t have to start from scratch anymore; we can help show them the way and support them in doing it.”

This month, HM13 (www.hospital medicine2013.org)—just outside Washington, D.C.—will offer multiple sessions on quality, as well as the “Initiating Quality Improvement Projects with Built-In Sustainment” workshop, led by Center for Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) core investigator Peter Kaboli, MD, MS, who will address sustainability.

Beyond methodological tools, success in quality and patient safety requires the ability to motivate people, often across multiple disciplines, Dr. Nagamine says. “If you want things to work better, you must invite the right people to the table. For example, we often forget to include key nonclinical stakeholders,” she adds.

When working with hospitals across the country to implement rapid-response tTeams, Dr. Nagamine often reminds them to invite the operators, or “key people,” in the process.

“If you put patient safety at the core of your initiative and create the context for that, most people will agree that it’s the right thing to do and will get on board, even if it’s an extra step for them,” she says. “Know your audience, listen to their perspective, and learn what matters to them. And to most people, it matters that they give good patient care.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Are you a hospitalist who, on daily rounds, often thinks, “There’s got to be a better way to do this”? You might be just the type of person who can carve a niche for yourself in hospital quality and patient safety—and advance your career in the process.

Successful navigation of the quality-improvement (QI) and patient-safety domains, according to three veteran hospitalists, requires an initial passion and an incremental approach. Now is an especially good time, they agree, for young hospitalists to engage in these types of initiatives.

Why Do It?

In her capacity as president of the Mid-Atlantic Business Unit for Brentwood, Tenn.-based CogentHMG, Julia Wright, MD, SFHM, FACP, often encourages young recruits to consider participation in QI and patient-safety initiatives. She admits that the transition from residency to a busy HM practice, with its higher patient volumes and a faster pace, can be daunting at first. Still, she tries to cultivate interest in initiatives and establish a realistic timeframe for involvement.

There are many reasons to consider this as a career step. Dr. Wright says that quality and patient safety dovetail with hospitalists’ initial reasons for choosing medicine: to improve patients’ lives.

Janet Nagamine, RN, MD, SFHM, former patient safety officer and assistant chief of quality at Kaiser Permanente in Santa Clara, Calif., describes the fit this way: “I might be a good doctor, but as a hospitalist, I rely on many others within the system to deliver, so my patients can’t get good care until the entire system is running well,” she says. “There are all kinds of opportunities to fix our [hospital] system, and I really believe that hospitalists cannot separate themselves from that engagement.”

Elizabeth Gundersen, MD, FHM, of Fort Lauderdale, Fla., agrees that it’s a natural step to think about the ways to make a difference on a larger level. At her former institution, the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Medical School in Worcester, she parlayed her interest in QI to work her way up from ground-level hospitalist to associate chief of her division and quality officer for the hospital. “Physicians get a lot of satisfaction from helping individual patients,” she says. “One thing I really liked about getting involved with quality improvement was being able to make a difference for patients on a systems level.”

An Incremental Path

The path to her current position began with a very specific issue for Dr. Nagamine, an SHM board member who also serves as a Project BOOST co-investigator. “Although I have been doing patient safety since before they had a name for it, I didn’t start out saying that I wanted a career in quality and safety,” she says. “I was trying to take better care of my patients with diabetes, but controlling their glucose was extremely challenging because all the related variables—timing and amount of their insulin dosage, when and how much they had eaten—were charted in different places. This made it hard to adjust their insulin appropriately.”

It quickly became clear to Dr. Nagamine that the solution had to be systemic. She realized that something as basic as taking care of her patients with diabetes required multiple departments (i.e. dietary, nursing, and pharmacy) to furnish information in an integrated manner. So she joined the diabetes committee and went to work on the issue. She helped devise a flow chart that could be used by all relevant departments. A further evolution on the path emanated from one of her patients receiving the wrong medication. She joined the medication safety committee, became chair, “and the next thing you know, I’m in charge of patient safety, and an assistant chief of quality.”

Training Is Necessary

QI and patient-safety methodologies have become sophisticated disciplines in the past two decades, Dr. Wright says. Access to training in QI basics now is readily available to early-career hospitalists. For example, CogentHMG offers program support for QI so that anyone interested “doesn’t have to start from scratch anymore; we can help show them the way and support them in doing it.”

This month, HM13 (www.hospital medicine2013.org)—just outside Washington, D.C.—will offer multiple sessions on quality, as well as the “Initiating Quality Improvement Projects with Built-In Sustainment” workshop, led by Center for Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) core investigator Peter Kaboli, MD, MS, who will address sustainability.

Beyond methodological tools, success in quality and patient safety requires the ability to motivate people, often across multiple disciplines, Dr. Nagamine says. “If you want things to work better, you must invite the right people to the table. For example, we often forget to include key nonclinical stakeholders,” she adds.

When working with hospitals across the country to implement rapid-response tTeams, Dr. Nagamine often reminds them to invite the operators, or “key people,” in the process.

“If you put patient safety at the core of your initiative and create the context for that, most people will agree that it’s the right thing to do and will get on board, even if it’s an extra step for them,” she says. “Know your audience, listen to their perspective, and learn what matters to them. And to most people, it matters that they give good patient care.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Are you a hospitalist who, on daily rounds, often thinks, “There’s got to be a better way to do this”? You might be just the type of person who can carve a niche for yourself in hospital quality and patient safety—and advance your career in the process.

Successful navigation of the quality-improvement (QI) and patient-safety domains, according to three veteran hospitalists, requires an initial passion and an incremental approach. Now is an especially good time, they agree, for young hospitalists to engage in these types of initiatives.

Why Do It?

In her capacity as president of the Mid-Atlantic Business Unit for Brentwood, Tenn.-based CogentHMG, Julia Wright, MD, SFHM, FACP, often encourages young recruits to consider participation in QI and patient-safety initiatives. She admits that the transition from residency to a busy HM practice, with its higher patient volumes and a faster pace, can be daunting at first. Still, she tries to cultivate interest in initiatives and establish a realistic timeframe for involvement.

There are many reasons to consider this as a career step. Dr. Wright says that quality and patient safety dovetail with hospitalists’ initial reasons for choosing medicine: to improve patients’ lives.

Janet Nagamine, RN, MD, SFHM, former patient safety officer and assistant chief of quality at Kaiser Permanente in Santa Clara, Calif., describes the fit this way: “I might be a good doctor, but as a hospitalist, I rely on many others within the system to deliver, so my patients can’t get good care until the entire system is running well,” she says. “There are all kinds of opportunities to fix our [hospital] system, and I really believe that hospitalists cannot separate themselves from that engagement.”

Elizabeth Gundersen, MD, FHM, of Fort Lauderdale, Fla., agrees that it’s a natural step to think about the ways to make a difference on a larger level. At her former institution, the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Medical School in Worcester, she parlayed her interest in QI to work her way up from ground-level hospitalist to associate chief of her division and quality officer for the hospital. “Physicians get a lot of satisfaction from helping individual patients,” she says. “One thing I really liked about getting involved with quality improvement was being able to make a difference for patients on a systems level.”

An Incremental Path

The path to her current position began with a very specific issue for Dr. Nagamine, an SHM board member who also serves as a Project BOOST co-investigator. “Although I have been doing patient safety since before they had a name for it, I didn’t start out saying that I wanted a career in quality and safety,” she says. “I was trying to take better care of my patients with diabetes, but controlling their glucose was extremely challenging because all the related variables—timing and amount of their insulin dosage, when and how much they had eaten—were charted in different places. This made it hard to adjust their insulin appropriately.”

It quickly became clear to Dr. Nagamine that the solution had to be systemic. She realized that something as basic as taking care of her patients with diabetes required multiple departments (i.e. dietary, nursing, and pharmacy) to furnish information in an integrated manner. So she joined the diabetes committee and went to work on the issue. She helped devise a flow chart that could be used by all relevant departments. A further evolution on the path emanated from one of her patients receiving the wrong medication. She joined the medication safety committee, became chair, “and the next thing you know, I’m in charge of patient safety, and an assistant chief of quality.”

Training Is Necessary

QI and patient-safety methodologies have become sophisticated disciplines in the past two decades, Dr. Wright says. Access to training in QI basics now is readily available to early-career hospitalists. For example, CogentHMG offers program support for QI so that anyone interested “doesn’t have to start from scratch anymore; we can help show them the way and support them in doing it.”

This month, HM13 (www.hospital medicine2013.org)—just outside Washington, D.C.—will offer multiple sessions on quality, as well as the “Initiating Quality Improvement Projects with Built-In Sustainment” workshop, led by Center for Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation (CADRE) core investigator Peter Kaboli, MD, MS, who will address sustainability.

Beyond methodological tools, success in quality and patient safety requires the ability to motivate people, often across multiple disciplines, Dr. Nagamine says. “If you want things to work better, you must invite the right people to the table. For example, we often forget to include key nonclinical stakeholders,” she adds.

When working with hospitals across the country to implement rapid-response tTeams, Dr. Nagamine often reminds them to invite the operators, or “key people,” in the process.

“If you put patient safety at the core of your initiative and create the context for that, most people will agree that it’s the right thing to do and will get on board, even if it’s an extra step for them,” she says. “Know your audience, listen to their perspective, and learn what matters to them. And to most people, it matters that they give good patient care.”

Gretchen Henkel is a freelance writer in California.

Defining and Protecting Scope of Practice Critical for Hospitalists

Scope creep can lead to suboptimal clinical outcomes if hospitalist practices fail to plan appropriately, Dr. Simone says. The plan must include “development of a staffing and schedule model to accommodate service expansion (when applicable), creation of policies and procedures addressing the new services, and hospitalist training (when appropriate) to ensure competently trained providers,” he adds.

Before any HM group agrees to comanagement, it should first understand the reasons for the request, Dr. Siegal says. According to a presentation he gave at HM07 on the topic, group leaders should:

- Determine if comanagement is a reasonable solution to the problem.

- Identify stakeholders and understand their goals, concerns, and expectations.

- Ask what might be jeopardized if hospitalists participate: Will it overload an already busy service, compromise care elsewhere, or set unrealistic service expectations?

- Set measurable outcomes to quantify the success (or failure) of the new arrangement.

It’s also important to define responsibilities, establish clear lines of communication, and determine how disagreements will be adjudicated. Establish your scope of practice and stick to it, Dr. Siegal says. A big red flag is when your group does things on nights, weekends, or holidays that it doesn’t do during the week.

Scope creep can lead to suboptimal clinical outcomes if hospitalist practices fail to plan appropriately, Dr. Simone says. The plan must include “development of a staffing and schedule model to accommodate service expansion (when applicable), creation of policies and procedures addressing the new services, and hospitalist training (when appropriate) to ensure competently trained providers,” he adds.

Before any HM group agrees to comanagement, it should first understand the reasons for the request, Dr. Siegal says. According to a presentation he gave at HM07 on the topic, group leaders should:

- Determine if comanagement is a reasonable solution to the problem.

- Identify stakeholders and understand their goals, concerns, and expectations.

- Ask what might be jeopardized if hospitalists participate: Will it overload an already busy service, compromise care elsewhere, or set unrealistic service expectations?

- Set measurable outcomes to quantify the success (or failure) of the new arrangement.

It’s also important to define responsibilities, establish clear lines of communication, and determine how disagreements will be adjudicated. Establish your scope of practice and stick to it, Dr. Siegal says. A big red flag is when your group does things on nights, weekends, or holidays that it doesn’t do during the week.

Scope creep can lead to suboptimal clinical outcomes if hospitalist practices fail to plan appropriately, Dr. Simone says. The plan must include “development of a staffing and schedule model to accommodate service expansion (when applicable), creation of policies and procedures addressing the new services, and hospitalist training (when appropriate) to ensure competently trained providers,” he adds.

Before any HM group agrees to comanagement, it should first understand the reasons for the request, Dr. Siegal says. According to a presentation he gave at HM07 on the topic, group leaders should:

- Determine if comanagement is a reasonable solution to the problem.

- Identify stakeholders and understand their goals, concerns, and expectations.

- Ask what might be jeopardized if hospitalists participate: Will it overload an already busy service, compromise care elsewhere, or set unrealistic service expectations?

- Set measurable outcomes to quantify the success (or failure) of the new arrangement.

It’s also important to define responsibilities, establish clear lines of communication, and determine how disagreements will be adjudicated. Establish your scope of practice and stick to it, Dr. Siegal says. A big red flag is when your group does things on nights, weekends, or holidays that it doesn’t do during the week.

Five Ways Hospitalists Can Prevent Overextending Their Services

1. Do not feel sorry for yourself; it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Most of what is happening in medicine is outside of our control,” Dr. Nelson says. “We need to realize that our role is going to change, and we should not perceive ourselves as the low person on the totem pole.”

2. Increase “face time” with your specialist colleagues.

Join them for lunch in the physician’s lounge, call your colleagues by their first names, engage in meaningful discussions about cases, and show empathy for them and their patients. Look for opportunities to do mutual education with other services.

3. Know when to draw the line.

“HM leaders should have the skills to analyze an opportunity and assess whether their program has the staffing capacity and clinical skills to successfully deliver a requested service,” Dr. Simone says. “‘No’ is an acceptable answer, if there are clear and reasonable reasons that support that decision.”

4. Make it about the patient.

Whenever your HM service is approached about comanagement, phrase your decision within the context of ensuring patient safety and delivering quality care. In that way, Dr. Siy says, you will be on solid footing.

5. Openly promote strategic “yes” answers.

Instead of digging in their heels, HM groups can periodically examine all requests, pick one or two to begin with, then promote successful outcomes to boost the group’s value.

1. Do not feel sorry for yourself; it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Most of what is happening in medicine is outside of our control,” Dr. Nelson says. “We need to realize that our role is going to change, and we should not perceive ourselves as the low person on the totem pole.”

2. Increase “face time” with your specialist colleagues.

Join them for lunch in the physician’s lounge, call your colleagues by their first names, engage in meaningful discussions about cases, and show empathy for them and their patients. Look for opportunities to do mutual education with other services.

3. Know when to draw the line.

“HM leaders should have the skills to analyze an opportunity and assess whether their program has the staffing capacity and clinical skills to successfully deliver a requested service,” Dr. Simone says. “‘No’ is an acceptable answer, if there are clear and reasonable reasons that support that decision.”

4. Make it about the patient.

Whenever your HM service is approached about comanagement, phrase your decision within the context of ensuring patient safety and delivering quality care. In that way, Dr. Siy says, you will be on solid footing.

5. Openly promote strategic “yes” answers.

Instead of digging in their heels, HM groups can periodically examine all requests, pick one or two to begin with, then promote successful outcomes to boost the group’s value.

1. Do not feel sorry for yourself; it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Most of what is happening in medicine is outside of our control,” Dr. Nelson says. “We need to realize that our role is going to change, and we should not perceive ourselves as the low person on the totem pole.”

2. Increase “face time” with your specialist colleagues.

Join them for lunch in the physician’s lounge, call your colleagues by their first names, engage in meaningful discussions about cases, and show empathy for them and their patients. Look for opportunities to do mutual education with other services.

3. Know when to draw the line.

“HM leaders should have the skills to analyze an opportunity and assess whether their program has the staffing capacity and clinical skills to successfully deliver a requested service,” Dr. Simone says. “‘No’ is an acceptable answer, if there are clear and reasonable reasons that support that decision.”

4. Make it about the patient.

Whenever your HM service is approached about comanagement, phrase your decision within the context of ensuring patient safety and delivering quality care. In that way, Dr. Siy says, you will be on solid footing.

5. Openly promote strategic “yes” answers.

Instead of digging in their heels, HM groups can periodically examine all requests, pick one or two to begin with, then promote successful outcomes to boost the group’s value.

Pressure to Expand Scope of Practice Extends to Most U.S. Hospitalists

Eric M. Siegal, MD, SFHM, vividly recalls the moment when he realized “scope creep” had become a problem. A hospitalist partner who was working a night shift admitted a young man who had been in a high-speed motor vehicle accident. The hospitalist did so because the general surgeon did not want to come into the hospital.

Dr. Siegal, currently the medical director of critical-care medicine at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee, remembers looking at his partner and asking, “What the hell are you doing admitting a trauma patient? You’re an internist!”

Dr. Siegal’s partner responded, “I’m just trying to show value.”

“That was an ‘a-ha’ moment for me,” says Dr. Siegal, a member of SHM’s board of directors. It was at that point he began to understand that the expansion strategy used by many HM services—to demonstrate value by agreeing to comanage or admit patients for their primary-care (PCP) and specialist colleagues—had produced some unintended negative consequences. “Hospitalists,” he says, “are like the spackle of the hospital. Sometimes spackle is good; it hides flaws and imperfections. But at other times, people use spackle to fix major structural problems.”