User login

Imaging suggestive, but symptoms atypical

A 66-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was brought to the emergency department with a 2-week history of progressive dyspnea followed by altered mental status. He had no history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or drug abuse.

On physical examination, he was stuporous. He had no fever or hypotension, but his pulse and breathing were rapid, and he had central cyanosis, bilateral conjunctival congestion, a puffy face, generalized wheezing, basilar crackles in both lungs, and leg edema.

Laboratory testing showed hypoxia and severe hypercarbia. His hematocrit was 65% (reference range 39–51) and his hemoglobin level was 21.5 g/dL (13–17).

The patient was diagnosed with an exacerbation of COPD. He was intubated, placed on mechanical ventilation, and admitted to the intensive care unit.

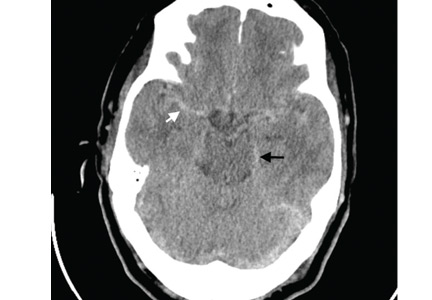

Computed tomography (CT) performed because of his decreased level of consciousness (Figure 1) showed increased attenuation in the ambient cistern and the lateral aspect of the lateral cerebral fissure, suggesting subarachnoid hemorrhage. The attenuation value in these areas was 89 Hounsfield units (typical values for brain tissue are in the 20s to 30s, and for blood in the 30s to 40s). To further evaluate for subarachnoid hemorrhage, lumbar puncture was performed, but analysis of the fluid sample showed normal protein and glucose levels and no cells.

Based on the results of cerebrospinal fluid evaluation and on the CT attenuation value, a diagnosis of pseudosubarachnoid hemorrhage due to polycythemia was made.

SUBARACHNOID VS PSEUDOSUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

Subarachnoid hemorrhage typically begins with a “thunder-clap” headache (beginning suddenly and described by patients as “the worst headache ever.”) While not all patients have this presentation, if imaging suggests subarachnoid hemorrhage but the patient has atypical signs and symptoms (eg, other than headache), then pseudosubarachnoid hemorrhage should be considered.

Brain CT is one of the most reliable tools for diagnosing subarachnoid hemorrhage in the emergency department. Done within 6 hours of symptom onset, it has a sensitivity of 98.7% and a specificity of 99.9%.1 Magnetic resonance imaging can also visualize subarachnoid hemorrhage within the first 12 hours, typically as a hyperintensity in the subarachnoid space on fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery sequences2 and on susceptibility-weighted sequences.

Lumbar puncture is also an important diagnostic tool but carries a risk of brain herniation in patients with brain edema.

Pseudosubarachnoid hemorrhage is an artifact of CT imaging. It is rare, and its prevalence is unknown.3 However, it may be seen in up to 20% of patients after resuscitation, as a result of diffuse cerebral edema that lowers the attenuation of brain tissue on CT, making the vessels relatively conspicuous. It can also be seen in purulent meningitis (due to proteinaceous influx after blood-brain barrier disruption),4 in meningeal leukemia (due to increased cellularity in the leptomeninges), and in severe polycythemia (from a higher concentration of blood and hemoglobin in the vessels).3,5–7

Although the level of attenuation on CT may help distinguish subarachnoid from pseudosubarachnoid hemorrhage, its accuracy has not been defined. Inspecting the CT images may clarify whether areas with high attenuation look like blood vessels vs subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Our patient recovered and had an uneventful follow-up. The cause of his elevated hematocrit was likely chronic hypoxia from COPD.

Acknowledgment: We thank Dr. Saeide Khanbagi and Dr. Azade Nasr-lari for their cooperation.

- Dubosh NM, Bellolio MF, Rabinstein AA, Edlow JA. Sensitivity of early brain computed tomography to exclude aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2016; 47:750–755.

- Sohn CH, Baik SK, Lee HJ, et al. MR imaging of hyperacute subarachnoid and intraventricular hemorrhage at 3T: a preliminary report of gradient echo T2*-weighted sequences. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26:662–665.

- Yuzawa H, Higano S, Mugikura S, et al. Pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage found in patients with postresuscitation encephalopathy: characteristics of CT findings and clinical importance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29:1544–1549.

- Given CA 2nd, Burdette JH, Elster AD, Williams DW 3rd. Pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage: a potential imaging pitfall associated with diffuse cerebral edema. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003; 24:254–256.

- Avrahami E, Katz R, Rabin A, Friedman V. CT diagnosis of non-traumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage in patients with brain edema. Eur J Radiol 1998; 28:222–225.

- Ben Salem D, Osseby GV, Rezaizadeh-Bourdariat K, et al. Spontaneous hyperdense intracranial vessels seen on CT scan in polycythemia cases. J Radiol 2003; 84:605–608. French.

- Hsieh SW, Khor GT, Chen CN, Huang P. Pseudo subarachnoid hemorrhage in meningeal leukemia. J Emerg Med 2012; 42:e109–e111.

A 66-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was brought to the emergency department with a 2-week history of progressive dyspnea followed by altered mental status. He had no history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or drug abuse.

On physical examination, he was stuporous. He had no fever or hypotension, but his pulse and breathing were rapid, and he had central cyanosis, bilateral conjunctival congestion, a puffy face, generalized wheezing, basilar crackles in both lungs, and leg edema.

Laboratory testing showed hypoxia and severe hypercarbia. His hematocrit was 65% (reference range 39–51) and his hemoglobin level was 21.5 g/dL (13–17).

The patient was diagnosed with an exacerbation of COPD. He was intubated, placed on mechanical ventilation, and admitted to the intensive care unit.

Computed tomography (CT) performed because of his decreased level of consciousness (Figure 1) showed increased attenuation in the ambient cistern and the lateral aspect of the lateral cerebral fissure, suggesting subarachnoid hemorrhage. The attenuation value in these areas was 89 Hounsfield units (typical values for brain tissue are in the 20s to 30s, and for blood in the 30s to 40s). To further evaluate for subarachnoid hemorrhage, lumbar puncture was performed, but analysis of the fluid sample showed normal protein and glucose levels and no cells.

Based on the results of cerebrospinal fluid evaluation and on the CT attenuation value, a diagnosis of pseudosubarachnoid hemorrhage due to polycythemia was made.

SUBARACHNOID VS PSEUDOSUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

Subarachnoid hemorrhage typically begins with a “thunder-clap” headache (beginning suddenly and described by patients as “the worst headache ever.”) While not all patients have this presentation, if imaging suggests subarachnoid hemorrhage but the patient has atypical signs and symptoms (eg, other than headache), then pseudosubarachnoid hemorrhage should be considered.

Brain CT is one of the most reliable tools for diagnosing subarachnoid hemorrhage in the emergency department. Done within 6 hours of symptom onset, it has a sensitivity of 98.7% and a specificity of 99.9%.1 Magnetic resonance imaging can also visualize subarachnoid hemorrhage within the first 12 hours, typically as a hyperintensity in the subarachnoid space on fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery sequences2 and on susceptibility-weighted sequences.

Lumbar puncture is also an important diagnostic tool but carries a risk of brain herniation in patients with brain edema.

Pseudosubarachnoid hemorrhage is an artifact of CT imaging. It is rare, and its prevalence is unknown.3 However, it may be seen in up to 20% of patients after resuscitation, as a result of diffuse cerebral edema that lowers the attenuation of brain tissue on CT, making the vessels relatively conspicuous. It can also be seen in purulent meningitis (due to proteinaceous influx after blood-brain barrier disruption),4 in meningeal leukemia (due to increased cellularity in the leptomeninges), and in severe polycythemia (from a higher concentration of blood and hemoglobin in the vessels).3,5–7

Although the level of attenuation on CT may help distinguish subarachnoid from pseudosubarachnoid hemorrhage, its accuracy has not been defined. Inspecting the CT images may clarify whether areas with high attenuation look like blood vessels vs subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Our patient recovered and had an uneventful follow-up. The cause of his elevated hematocrit was likely chronic hypoxia from COPD.

Acknowledgment: We thank Dr. Saeide Khanbagi and Dr. Azade Nasr-lari for their cooperation.

A 66-year-old man with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was brought to the emergency department with a 2-week history of progressive dyspnea followed by altered mental status. He had no history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or drug abuse.

On physical examination, he was stuporous. He had no fever or hypotension, but his pulse and breathing were rapid, and he had central cyanosis, bilateral conjunctival congestion, a puffy face, generalized wheezing, basilar crackles in both lungs, and leg edema.

Laboratory testing showed hypoxia and severe hypercarbia. His hematocrit was 65% (reference range 39–51) and his hemoglobin level was 21.5 g/dL (13–17).

The patient was diagnosed with an exacerbation of COPD. He was intubated, placed on mechanical ventilation, and admitted to the intensive care unit.

Computed tomography (CT) performed because of his decreased level of consciousness (Figure 1) showed increased attenuation in the ambient cistern and the lateral aspect of the lateral cerebral fissure, suggesting subarachnoid hemorrhage. The attenuation value in these areas was 89 Hounsfield units (typical values for brain tissue are in the 20s to 30s, and for blood in the 30s to 40s). To further evaluate for subarachnoid hemorrhage, lumbar puncture was performed, but analysis of the fluid sample showed normal protein and glucose levels and no cells.

Based on the results of cerebrospinal fluid evaluation and on the CT attenuation value, a diagnosis of pseudosubarachnoid hemorrhage due to polycythemia was made.

SUBARACHNOID VS PSEUDOSUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

Subarachnoid hemorrhage typically begins with a “thunder-clap” headache (beginning suddenly and described by patients as “the worst headache ever.”) While not all patients have this presentation, if imaging suggests subarachnoid hemorrhage but the patient has atypical signs and symptoms (eg, other than headache), then pseudosubarachnoid hemorrhage should be considered.

Brain CT is one of the most reliable tools for diagnosing subarachnoid hemorrhage in the emergency department. Done within 6 hours of symptom onset, it has a sensitivity of 98.7% and a specificity of 99.9%.1 Magnetic resonance imaging can also visualize subarachnoid hemorrhage within the first 12 hours, typically as a hyperintensity in the subarachnoid space on fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery sequences2 and on susceptibility-weighted sequences.

Lumbar puncture is also an important diagnostic tool but carries a risk of brain herniation in patients with brain edema.

Pseudosubarachnoid hemorrhage is an artifact of CT imaging. It is rare, and its prevalence is unknown.3 However, it may be seen in up to 20% of patients after resuscitation, as a result of diffuse cerebral edema that lowers the attenuation of brain tissue on CT, making the vessels relatively conspicuous. It can also be seen in purulent meningitis (due to proteinaceous influx after blood-brain barrier disruption),4 in meningeal leukemia (due to increased cellularity in the leptomeninges), and in severe polycythemia (from a higher concentration of blood and hemoglobin in the vessels).3,5–7

Although the level of attenuation on CT may help distinguish subarachnoid from pseudosubarachnoid hemorrhage, its accuracy has not been defined. Inspecting the CT images may clarify whether areas with high attenuation look like blood vessels vs subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Our patient recovered and had an uneventful follow-up. The cause of his elevated hematocrit was likely chronic hypoxia from COPD.

Acknowledgment: We thank Dr. Saeide Khanbagi and Dr. Azade Nasr-lari for their cooperation.

- Dubosh NM, Bellolio MF, Rabinstein AA, Edlow JA. Sensitivity of early brain computed tomography to exclude aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2016; 47:750–755.

- Sohn CH, Baik SK, Lee HJ, et al. MR imaging of hyperacute subarachnoid and intraventricular hemorrhage at 3T: a preliminary report of gradient echo T2*-weighted sequences. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26:662–665.

- Yuzawa H, Higano S, Mugikura S, et al. Pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage found in patients with postresuscitation encephalopathy: characteristics of CT findings and clinical importance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29:1544–1549.

- Given CA 2nd, Burdette JH, Elster AD, Williams DW 3rd. Pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage: a potential imaging pitfall associated with diffuse cerebral edema. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003; 24:254–256.

- Avrahami E, Katz R, Rabin A, Friedman V. CT diagnosis of non-traumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage in patients with brain edema. Eur J Radiol 1998; 28:222–225.

- Ben Salem D, Osseby GV, Rezaizadeh-Bourdariat K, et al. Spontaneous hyperdense intracranial vessels seen on CT scan in polycythemia cases. J Radiol 2003; 84:605–608. French.

- Hsieh SW, Khor GT, Chen CN, Huang P. Pseudo subarachnoid hemorrhage in meningeal leukemia. J Emerg Med 2012; 42:e109–e111.

- Dubosh NM, Bellolio MF, Rabinstein AA, Edlow JA. Sensitivity of early brain computed tomography to exclude aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke 2016; 47:750–755.

- Sohn CH, Baik SK, Lee HJ, et al. MR imaging of hyperacute subarachnoid and intraventricular hemorrhage at 3T: a preliminary report of gradient echo T2*-weighted sequences. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26:662–665.

- Yuzawa H, Higano S, Mugikura S, et al. Pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage found in patients with postresuscitation encephalopathy: characteristics of CT findings and clinical importance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008; 29:1544–1549.

- Given CA 2nd, Burdette JH, Elster AD, Williams DW 3rd. Pseudo-subarachnoid hemorrhage: a potential imaging pitfall associated with diffuse cerebral edema. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003; 24:254–256.

- Avrahami E, Katz R, Rabin A, Friedman V. CT diagnosis of non-traumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage in patients with brain edema. Eur J Radiol 1998; 28:222–225.

- Ben Salem D, Osseby GV, Rezaizadeh-Bourdariat K, et al. Spontaneous hyperdense intracranial vessels seen on CT scan in polycythemia cases. J Radiol 2003; 84:605–608. French.

- Hsieh SW, Khor GT, Chen CN, Huang P. Pseudo subarachnoid hemorrhage in meningeal leukemia. J Emerg Med 2012; 42:e109–e111.

A lump in the umbilicus

A 60-year-old man presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain. The pain was dull and constant, with no radiation and no aggravating or relieving factors. He also reported decreased appetite, weight loss, and constipation over the past 3 months.

He had no history of significant medical problems and was not taking any medications. He had no fever and no evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Physical examination showed mild tenderness around the umbilicus and a painless, small nodule (15 mm by 6 mm) protruding through the umbilicus with surrounding erythematous discoloration (Figure 1). A digital rectal examination was normal. Laboratory studies showed only mild normocytic anemia.

The patient underwent abdominal ultrasonography, which showed free fluid in the abdominopelvic cavity. This was followed by computed tomography of the abdominopelvic cavity, which revealed ascites and a small mass in the umbilicus. Punch biopsy of the umbilical lesion was performed, and histologic study indicated a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma.

Based on the biopsy results and the patient’s history of gastrointestinal symptoms, colonoscopy was performed, which showed an exophytic tumor of the transverse colon. The tumor was biopsied, and pathologic evaluation confirmed adenocarcinoma. A diagnosis of metastatic colon cancer was made. The patient received chemotherapy and underwent surgery to relieve the bowel obstruction.

SISTER MARY JOSEPH NODULE

A periumbilical nodule representing metastatic cancer, also known as Sister Mary Joseph nodule,1 is typically associated with intra-abdominal malignancy. An estimated 1% to 3% of patients with abdominopelvic malignancy present with this nodule,2 most often from gastrointestinal cancer but also from gynecologic malignancies. In about 15% to 30% of cases, no origin is identified.3

How these cancers spread to the umbilicus is not known. Proposed mechanisms include direct transperitoneal, lymphatic, or hematogenous spread, and even iatrogenic spread during laparotomy.4,5

The differential diagnosis includes umbilical hernia, cutaneous endometriosis, lymphangioma, melanoma, pilonidal sinus, and pyogenic granuloma. It is usually described as a painful nodule with irregular margins and a mean diameter of 2 to 3 cm.2 The condition is always a sign of metastatic cancer. Although it can be useful for diagnosing advanced disease, whether this would lead to earlier diagnosis is doubtful. Palliative treatment is generally most appropriate.

- Albano EA, Kanter J. Images in clinical medicine. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:1913.

- Iavazzo C, Madhuri K, Essapen S, Akrivos N, Tailor A, Butler-Manuel S. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule as a first manifestation of primary peritoneal cancer. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2012; 2012:467240.

- Gabriele R, Borghese M, Conte M, Basso L. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule as a first sign of cancer of the cecum: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47:115–117.

- Dar IH, Kamili MA, Dar SH, Kuchaai FA. Sister Mary Joseph nodule—a case report with review of literature. J Res Med Sci 2009; 14:385–387.

- Martínez-Palones JM, Gil-Moreno A, Pérez-Benavente MA, Garcia-Giménez A, Xercavins J. Umbilical metastasis after laparoscopic retroperitoneal paraaortic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer: a true port-site metastasis? Gynecol Oncol 2005; 97:292–295.

A 60-year-old man presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain. The pain was dull and constant, with no radiation and no aggravating or relieving factors. He also reported decreased appetite, weight loss, and constipation over the past 3 months.

He had no history of significant medical problems and was not taking any medications. He had no fever and no evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Physical examination showed mild tenderness around the umbilicus and a painless, small nodule (15 mm by 6 mm) protruding through the umbilicus with surrounding erythematous discoloration (Figure 1). A digital rectal examination was normal. Laboratory studies showed only mild normocytic anemia.

The patient underwent abdominal ultrasonography, which showed free fluid in the abdominopelvic cavity. This was followed by computed tomography of the abdominopelvic cavity, which revealed ascites and a small mass in the umbilicus. Punch biopsy of the umbilical lesion was performed, and histologic study indicated a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma.

Based on the biopsy results and the patient’s history of gastrointestinal symptoms, colonoscopy was performed, which showed an exophytic tumor of the transverse colon. The tumor was biopsied, and pathologic evaluation confirmed adenocarcinoma. A diagnosis of metastatic colon cancer was made. The patient received chemotherapy and underwent surgery to relieve the bowel obstruction.

SISTER MARY JOSEPH NODULE

A periumbilical nodule representing metastatic cancer, also known as Sister Mary Joseph nodule,1 is typically associated with intra-abdominal malignancy. An estimated 1% to 3% of patients with abdominopelvic malignancy present with this nodule,2 most often from gastrointestinal cancer but also from gynecologic malignancies. In about 15% to 30% of cases, no origin is identified.3

How these cancers spread to the umbilicus is not known. Proposed mechanisms include direct transperitoneal, lymphatic, or hematogenous spread, and even iatrogenic spread during laparotomy.4,5

The differential diagnosis includes umbilical hernia, cutaneous endometriosis, lymphangioma, melanoma, pilonidal sinus, and pyogenic granuloma. It is usually described as a painful nodule with irregular margins and a mean diameter of 2 to 3 cm.2 The condition is always a sign of metastatic cancer. Although it can be useful for diagnosing advanced disease, whether this would lead to earlier diagnosis is doubtful. Palliative treatment is generally most appropriate.

A 60-year-old man presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain. The pain was dull and constant, with no radiation and no aggravating or relieving factors. He also reported decreased appetite, weight loss, and constipation over the past 3 months.

He had no history of significant medical problems and was not taking any medications. He had no fever and no evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Physical examination showed mild tenderness around the umbilicus and a painless, small nodule (15 mm by 6 mm) protruding through the umbilicus with surrounding erythematous discoloration (Figure 1). A digital rectal examination was normal. Laboratory studies showed only mild normocytic anemia.

The patient underwent abdominal ultrasonography, which showed free fluid in the abdominopelvic cavity. This was followed by computed tomography of the abdominopelvic cavity, which revealed ascites and a small mass in the umbilicus. Punch biopsy of the umbilical lesion was performed, and histologic study indicated a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma.

Based on the biopsy results and the patient’s history of gastrointestinal symptoms, colonoscopy was performed, which showed an exophytic tumor of the transverse colon. The tumor was biopsied, and pathologic evaluation confirmed adenocarcinoma. A diagnosis of metastatic colon cancer was made. The patient received chemotherapy and underwent surgery to relieve the bowel obstruction.

SISTER MARY JOSEPH NODULE

A periumbilical nodule representing metastatic cancer, also known as Sister Mary Joseph nodule,1 is typically associated with intra-abdominal malignancy. An estimated 1% to 3% of patients with abdominopelvic malignancy present with this nodule,2 most often from gastrointestinal cancer but also from gynecologic malignancies. In about 15% to 30% of cases, no origin is identified.3

How these cancers spread to the umbilicus is not known. Proposed mechanisms include direct transperitoneal, lymphatic, or hematogenous spread, and even iatrogenic spread during laparotomy.4,5

The differential diagnosis includes umbilical hernia, cutaneous endometriosis, lymphangioma, melanoma, pilonidal sinus, and pyogenic granuloma. It is usually described as a painful nodule with irregular margins and a mean diameter of 2 to 3 cm.2 The condition is always a sign of metastatic cancer. Although it can be useful for diagnosing advanced disease, whether this would lead to earlier diagnosis is doubtful. Palliative treatment is generally most appropriate.

- Albano EA, Kanter J. Images in clinical medicine. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:1913.

- Iavazzo C, Madhuri K, Essapen S, Akrivos N, Tailor A, Butler-Manuel S. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule as a first manifestation of primary peritoneal cancer. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2012; 2012:467240.

- Gabriele R, Borghese M, Conte M, Basso L. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule as a first sign of cancer of the cecum: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47:115–117.

- Dar IH, Kamili MA, Dar SH, Kuchaai FA. Sister Mary Joseph nodule—a case report with review of literature. J Res Med Sci 2009; 14:385–387.

- Martínez-Palones JM, Gil-Moreno A, Pérez-Benavente MA, Garcia-Giménez A, Xercavins J. Umbilical metastasis after laparoscopic retroperitoneal paraaortic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer: a true port-site metastasis? Gynecol Oncol 2005; 97:292–295.

- Albano EA, Kanter J. Images in clinical medicine. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:1913.

- Iavazzo C, Madhuri K, Essapen S, Akrivos N, Tailor A, Butler-Manuel S. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule as a first manifestation of primary peritoneal cancer. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2012; 2012:467240.

- Gabriele R, Borghese M, Conte M, Basso L. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule as a first sign of cancer of the cecum: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47:115–117.

- Dar IH, Kamili MA, Dar SH, Kuchaai FA. Sister Mary Joseph nodule—a case report with review of literature. J Res Med Sci 2009; 14:385–387.

- Martínez-Palones JM, Gil-Moreno A, Pérez-Benavente MA, Garcia-Giménez A, Xercavins J. Umbilical metastasis after laparoscopic retroperitoneal paraaortic lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer: a true port-site metastasis? Gynecol Oncol 2005; 97:292–295.