News

One practice’s experience with obesity treatment

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

WASHINGTON – “We have heard about a lot of really interesting new things in therapy, but the reality is that they are just not economically viable...

News

Cost is high for Japanese encephalitis vaccinations

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

A model of Japanese encephalitis showed a low chance of transmission coupled with large individual and societal...

News

Disparities found in access to medication treatment for OUDs

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

Medicaid recipients living in counties with fewer black and Hispanic residents – and lower poverty rates – are more likely to receive OUD...

News

FDA approves topical anticholinergic for primary axillary hyperhidrosis

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

Glycopyrronium, approved for children and adults ages 9 years and older, comes in a single-use cloth wipe applied once a day to both axillae.

News

Screen sooner and more often for those with family history of CRC

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

A family history of colorectal cancer is associated with risk of colorectal cancer, and screening guidelines should be adjusted accordingly.

News

Anthrax vaccine recommendations updated in the event of a wide-area release

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

The committee recommended three updates to its current policy of anthrax vaccination.

News

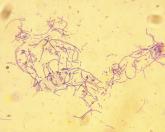

Bullae associated with pediatric human parvovirus B19 infection

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

Parvovirus is generally associated with a “slapped-cheek” appearance, with the appearance of bullae rare.

News

ACIP votes to recommend new strains for the 2018-2019 flu vaccine

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

FluMist is back in the midst of available flu vaccine options.

News

Preterm infant GER is a normal phenomenon

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

Traditional and pharmacologic interventions do not appear to work. Patience may be the best medicine.

News

Pancreatic cancer has a pancreatopathy distinct from type 2 diabetes

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

WASHINGTON – The relationship between pancreatic cancer and diabetes is complex, but certain pathological markers differentiate them.

News

FDA approves pembrolizumab for relapsed/refractory PMBCL

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

The FDA granted accelerated approval based on results from the KEYNOTE-170 trial.

Video

Web portal does not reduce phone encounters or office visits for IBD patients

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

WASHINGTON - The web portal MyChart allows patients to send messages to their providers, but does not improve patient outcomes.

News

Multiple therapies for NAFLD and NASH are now in phase 3 clinical trials

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

WASHINGTON – The trials are tricky, but these much-needed therapies may get conditional approval through reduction of liver inflammation and...

News

Barrett’s segment length, low-grade dysplasia tied to increased risk of neoplastic progression

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

A Dutch study found that age at baseline endoscopy, length of Barrett’s segment, and low-grade dysplasia were significant predictors of neoplastic...

News

FDA approves Olumiant for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis

- Author:

- Ian Lacy

Lilly said it expects the JAK inhibitor to be available in the second quarter of 2018.