Article

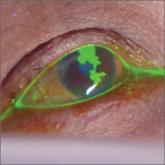

Painful facial blisters, fever, and conjunctivitis

- Author:

- Melissa Neuman, MD

- Jack Spittler, MD

Following Tx for facial blisters, our patient returned with what appeared to be viral conjunctivitis. Further evaluation revealed a missed tip-off...

Article

How do hyaluronic acid and corticosteroid injections compare for knee OA relief?

- Author:

- Corey Lyon, DO

- Emily Spencer, MD

- Jack Spittler, MD

- Kristen Desanto, MSLS, MS, RD, AHIP

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER: Inconsistent evidence shows a small amount of pain relief early (one week to 3 months) with corticosteroid (CS) injections...