User login

What Is Your Diagnosis? Pemphigoid Gestationis (Herpes Gestationis)

A 37-year-old pregnant woman at 25 weeks’ gestation presented with a generalized pruritic rash of 3 weeks’ duration. The rash had initiated around the umbilicus and continued to progress with subsequent involvement of the arms and legs. The patient reported no allergies or current medications, and her personal and family history was unremarkable. She had 2 prior uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries. Physical examination revealed severe ecchymotic plaques, vesicles, and bullae on the arms (top), as well as confluent erythematous plaques on the abdomen (bottom), back, and legs. The mucosal surfaces, face, palms, and soles were spared. Laboratory values were within reference range.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigoid Gestationis (Herpes Gestationis)

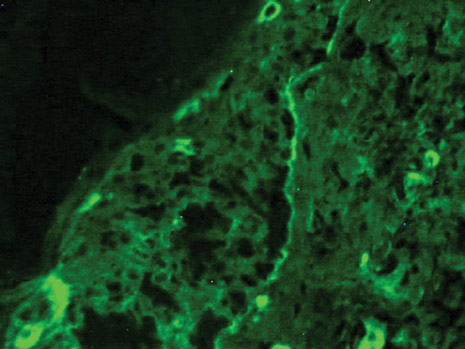

Dermoscopy revealed a patch of erythema with early central vesiculation (Figure 1). Perilesional skin biopsies revealed subepidermal bullae, and direct immunofluorescence revealed linear C3 and IgG deposition at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2).

|

Dermatoses of pregnancy are uncommon and may demonstrate similar clinical manifestations. Pemphigoid gestationis (herpes gestationis) is a condition that may initially mimic other pregnancy-related skin diseases but is followed by the classic manifestations of a bullous disease. A biopsy specimen is needed to identify the epidermal lesions that are present. Once identified, it responds to treatment with steroids.

Pemphigoid gestationis is a skin disorder in which circulating IgG autoantibodies react against transmembrane proteins and hemidesmosomal components of the epidermal basal cells.1 This process leads to complement protein activation through the classical pathway, which promotes leukocyte recruitment and degranulation. The initial clinical manifestation includes pruritus, which is followed by characteristic bullous lesions.

Pemphigoid gestationis is hypothesized to arise from pathologic maternal IgG induced by paternal HLA antigens found in the placenta.2 The incidence of pemphigoid gestationis is thought to range from 1:10,000 to 1:50,000,3 with typical presentation in the second or third trimesters. It may be exacerbated during delivery and generally resolves after delivery. The periumbilical region is the first site affected with subsequent spreading to the arms and legs.3 The initial differential diagnosis based on patient history can include an adverse drug reaction or pruritic urticarial papules and pustules of pregnancy. Diagnosis is based on histologic examination of a perilesional skin biopsy. Light microscopy of the biopsy typically reveals subepidermal bullae with a predominance of infiltrated eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence of the biopsy specimen usually confirms the diagnosis with the presence of linear C3 and IgG deposition at the dermoepidermal junction. Indirect immunofluorescence occasionally may reveal IgG deposition in the basal membrane.4

Treatment generally includes the use of topical and oral steroids.2,5 Fetal risks associated with the disease include premature birth and low birth weight.2,3 Our patient initially was started on a 1-mg/kg dose of oral prednisone and topical steroid (prednisone 60 mg in a tapering dose every 5 days); she showed a good response at 1-week follow-up. She was well controlled with a lower maintenance dose through the rest of the pregnancy and did not show subsequent disease exacerbation.

1. Parker SR, MacKelfresh J. Autoimmune blistering disease in the elderly. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:69-79.

2. Shornick JK. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:172-181.

3. Al-Fouzan AW, Galadari I, Oumeish I, et al. Herpes gestationis (pemphigoid gestationis). Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:109-112.

4. Imber MJ, Murphy GF, Jordon RE. The immunopathology of bullous pemphigoid. Clin Dermatol. 1987;5:81-92.

5. Kirtschig G, Middleton P, Bennett C, et al. Interventions for bullous pemphigoid. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD002292.

A 37-year-old pregnant woman at 25 weeks’ gestation presented with a generalized pruritic rash of 3 weeks’ duration. The rash had initiated around the umbilicus and continued to progress with subsequent involvement of the arms and legs. The patient reported no allergies or current medications, and her personal and family history was unremarkable. She had 2 prior uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries. Physical examination revealed severe ecchymotic plaques, vesicles, and bullae on the arms (top), as well as confluent erythematous plaques on the abdomen (bottom), back, and legs. The mucosal surfaces, face, palms, and soles were spared. Laboratory values were within reference range.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigoid Gestationis (Herpes Gestationis)

Dermoscopy revealed a patch of erythema with early central vesiculation (Figure 1). Perilesional skin biopsies revealed subepidermal bullae, and direct immunofluorescence revealed linear C3 and IgG deposition at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2).

|

Dermatoses of pregnancy are uncommon and may demonstrate similar clinical manifestations. Pemphigoid gestationis (herpes gestationis) is a condition that may initially mimic other pregnancy-related skin diseases but is followed by the classic manifestations of a bullous disease. A biopsy specimen is needed to identify the epidermal lesions that are present. Once identified, it responds to treatment with steroids.

Pemphigoid gestationis is a skin disorder in which circulating IgG autoantibodies react against transmembrane proteins and hemidesmosomal components of the epidermal basal cells.1 This process leads to complement protein activation through the classical pathway, which promotes leukocyte recruitment and degranulation. The initial clinical manifestation includes pruritus, which is followed by characteristic bullous lesions.

Pemphigoid gestationis is hypothesized to arise from pathologic maternal IgG induced by paternal HLA antigens found in the placenta.2 The incidence of pemphigoid gestationis is thought to range from 1:10,000 to 1:50,000,3 with typical presentation in the second or third trimesters. It may be exacerbated during delivery and generally resolves after delivery. The periumbilical region is the first site affected with subsequent spreading to the arms and legs.3 The initial differential diagnosis based on patient history can include an adverse drug reaction or pruritic urticarial papules and pustules of pregnancy. Diagnosis is based on histologic examination of a perilesional skin biopsy. Light microscopy of the biopsy typically reveals subepidermal bullae with a predominance of infiltrated eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence of the biopsy specimen usually confirms the diagnosis with the presence of linear C3 and IgG deposition at the dermoepidermal junction. Indirect immunofluorescence occasionally may reveal IgG deposition in the basal membrane.4

Treatment generally includes the use of topical and oral steroids.2,5 Fetal risks associated with the disease include premature birth and low birth weight.2,3 Our patient initially was started on a 1-mg/kg dose of oral prednisone and topical steroid (prednisone 60 mg in a tapering dose every 5 days); she showed a good response at 1-week follow-up. She was well controlled with a lower maintenance dose through the rest of the pregnancy and did not show subsequent disease exacerbation.

A 37-year-old pregnant woman at 25 weeks’ gestation presented with a generalized pruritic rash of 3 weeks’ duration. The rash had initiated around the umbilicus and continued to progress with subsequent involvement of the arms and legs. The patient reported no allergies or current medications, and her personal and family history was unremarkable. She had 2 prior uncomplicated pregnancies and deliveries. Physical examination revealed severe ecchymotic plaques, vesicles, and bullae on the arms (top), as well as confluent erythematous plaques on the abdomen (bottom), back, and legs. The mucosal surfaces, face, palms, and soles were spared. Laboratory values were within reference range.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigoid Gestationis (Herpes Gestationis)

Dermoscopy revealed a patch of erythema with early central vesiculation (Figure 1). Perilesional skin biopsies revealed subepidermal bullae, and direct immunofluorescence revealed linear C3 and IgG deposition at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2).

|

Dermatoses of pregnancy are uncommon and may demonstrate similar clinical manifestations. Pemphigoid gestationis (herpes gestationis) is a condition that may initially mimic other pregnancy-related skin diseases but is followed by the classic manifestations of a bullous disease. A biopsy specimen is needed to identify the epidermal lesions that are present. Once identified, it responds to treatment with steroids.

Pemphigoid gestationis is a skin disorder in which circulating IgG autoantibodies react against transmembrane proteins and hemidesmosomal components of the epidermal basal cells.1 This process leads to complement protein activation through the classical pathway, which promotes leukocyte recruitment and degranulation. The initial clinical manifestation includes pruritus, which is followed by characteristic bullous lesions.

Pemphigoid gestationis is hypothesized to arise from pathologic maternal IgG induced by paternal HLA antigens found in the placenta.2 The incidence of pemphigoid gestationis is thought to range from 1:10,000 to 1:50,000,3 with typical presentation in the second or third trimesters. It may be exacerbated during delivery and generally resolves after delivery. The periumbilical region is the first site affected with subsequent spreading to the arms and legs.3 The initial differential diagnosis based on patient history can include an adverse drug reaction or pruritic urticarial papules and pustules of pregnancy. Diagnosis is based on histologic examination of a perilesional skin biopsy. Light microscopy of the biopsy typically reveals subepidermal bullae with a predominance of infiltrated eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence of the biopsy specimen usually confirms the diagnosis with the presence of linear C3 and IgG deposition at the dermoepidermal junction. Indirect immunofluorescence occasionally may reveal IgG deposition in the basal membrane.4

Treatment generally includes the use of topical and oral steroids.2,5 Fetal risks associated with the disease include premature birth and low birth weight.2,3 Our patient initially was started on a 1-mg/kg dose of oral prednisone and topical steroid (prednisone 60 mg in a tapering dose every 5 days); she showed a good response at 1-week follow-up. She was well controlled with a lower maintenance dose through the rest of the pregnancy and did not show subsequent disease exacerbation.

1. Parker SR, MacKelfresh J. Autoimmune blistering disease in the elderly. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:69-79.

2. Shornick JK. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:172-181.

3. Al-Fouzan AW, Galadari I, Oumeish I, et al. Herpes gestationis (pemphigoid gestationis). Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:109-112.

4. Imber MJ, Murphy GF, Jordon RE. The immunopathology of bullous pemphigoid. Clin Dermatol. 1987;5:81-92.

5. Kirtschig G, Middleton P, Bennett C, et al. Interventions for bullous pemphigoid. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD002292.

1. Parker SR, MacKelfresh J. Autoimmune blistering disease in the elderly. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:69-79.

2. Shornick JK. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:172-181.

3. Al-Fouzan AW, Galadari I, Oumeish I, et al. Herpes gestationis (pemphigoid gestationis). Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:109-112.

4. Imber MJ, Murphy GF, Jordon RE. The immunopathology of bullous pemphigoid. Clin Dermatol. 1987;5:81-92.

5. Kirtschig G, Middleton P, Bennett C, et al. Interventions for bullous pemphigoid. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD002292.

Hairs With an Irregular Shape

The Diagnosis: Circle Hairs

The patient’s hairs were visualized under dermoscopy (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with circle hairs.

Circle hairs were first described in 1963.1 These peculiar hairs grow in a circular horizontal distribution beneath the stratum corneum and are considered benign incidental findings. Their exact cause is unknown. If taken out and unrolled, their length and diameter tends to be smaller than surrounding hairs. It has been hypothesized that they are the result of hairs that lack the size necessary to perforate the stratum corneum.2 Others propose that they are vestigial remains that once had a part in preserving body heat.3 Circle hairs tend to grow in elderly, hairy, and obese males, predominantly on the torso and thighs.2,4

It is important to distinguish between circle hairs and rolled hairs. Rolled hairs may be found on the surface or beneath the stratum corneum and are associated with inflammation and keratinization abnormalities.2 If taken together, these latter findings can help differentiate between the two. The importance stands in recognizing that both circle hairs and rolled hairs are benign; however, rolled hairs can be related to other skin disorders that need additional treatment.

|

|

| Figure 2. A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (A and B)(both Verhoeff-van Gieson, original magnifications ×40). |

1. Adatto R. Poils en spirale (poils enroules). Dermatologica. 1963;127:145-147.

2. Smith JB, Hogan DJ. Circle hairs are not rolled hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:634-635.

3. Contreras-Ruiz J, Duran-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sanchez L, et al. Circle hairs: a clinical curiosity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:495-497.

4. Levit F, Scott MJ Jr. Circle hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:423-425.

The Diagnosis: Circle Hairs

The patient’s hairs were visualized under dermoscopy (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with circle hairs.

Circle hairs were first described in 1963.1 These peculiar hairs grow in a circular horizontal distribution beneath the stratum corneum and are considered benign incidental findings. Their exact cause is unknown. If taken out and unrolled, their length and diameter tends to be smaller than surrounding hairs. It has been hypothesized that they are the result of hairs that lack the size necessary to perforate the stratum corneum.2 Others propose that they are vestigial remains that once had a part in preserving body heat.3 Circle hairs tend to grow in elderly, hairy, and obese males, predominantly on the torso and thighs.2,4

It is important to distinguish between circle hairs and rolled hairs. Rolled hairs may be found on the surface or beneath the stratum corneum and are associated with inflammation and keratinization abnormalities.2 If taken together, these latter findings can help differentiate between the two. The importance stands in recognizing that both circle hairs and rolled hairs are benign; however, rolled hairs can be related to other skin disorders that need additional treatment.

|

|

| Figure 2. A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (A and B)(both Verhoeff-van Gieson, original magnifications ×40). |

The Diagnosis: Circle Hairs

The patient’s hairs were visualized under dermoscopy (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with circle hairs.

Circle hairs were first described in 1963.1 These peculiar hairs grow in a circular horizontal distribution beneath the stratum corneum and are considered benign incidental findings. Their exact cause is unknown. If taken out and unrolled, their length and diameter tends to be smaller than surrounding hairs. It has been hypothesized that they are the result of hairs that lack the size necessary to perforate the stratum corneum.2 Others propose that they are vestigial remains that once had a part in preserving body heat.3 Circle hairs tend to grow in elderly, hairy, and obese males, predominantly on the torso and thighs.2,4

It is important to distinguish between circle hairs and rolled hairs. Rolled hairs may be found on the surface or beneath the stratum corneum and are associated with inflammation and keratinization abnormalities.2 If taken together, these latter findings can help differentiate between the two. The importance stands in recognizing that both circle hairs and rolled hairs are benign; however, rolled hairs can be related to other skin disorders that need additional treatment.

|

|

| Figure 2. A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (A and B)(both Verhoeff-van Gieson, original magnifications ×40). |

1. Adatto R. Poils en spirale (poils enroules). Dermatologica. 1963;127:145-147.

2. Smith JB, Hogan DJ. Circle hairs are not rolled hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:634-635.

3. Contreras-Ruiz J, Duran-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sanchez L, et al. Circle hairs: a clinical curiosity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:495-497.

4. Levit F, Scott MJ Jr. Circle hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:423-425.

1. Adatto R. Poils en spirale (poils enroules). Dermatologica. 1963;127:145-147.

2. Smith JB, Hogan DJ. Circle hairs are not rolled hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:634-635.

3. Contreras-Ruiz J, Duran-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sanchez L, et al. Circle hairs: a clinical curiosity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:495-497.

4. Levit F, Scott MJ Jr. Circle hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:423-425.

A 74-year-old man was evaluated for numerous peculiar hairs on the back that had been present for several years. He reported no other dermatologic concerns. The patient was obese and led a sedentary lifestyle, spending most of the day sitting or lying down. Physical examination revealed a hairy back with many irregularly shaped hairs.

Eccrine Angiomatous Hamartoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is a benign and uncommon malformation, characterized by increased numbers of eccrine (sweat) glands and numerous capillary channels. It is usually congenital or arises during the prepubertal years; the lesion only rarely presents during adulthood. The color of EAH may be flesh colored, blue-brown, or reddish and may occur as a nodule, plaque, or, less commonly, a macule. In most cases, EAH arises as a single lesion on the extremity, though reports of multiple lesions and those occurring in more unusual sites exist. The symptoms most commonly associated with EAH are pain and hyperhidrosis; enlargement may occur and is usually in concordance with the growth of the patient. It is important to recognize the hamartoma as a benign clinical entity, for which aggressive management is not necessary. In this article, we report a case of EAH occurring in a young girl, and we review 41 well-documented cases in the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 12-year-old previously healthy Hispanic girl presented with a lesion on the posterior aspect of her left lower leg. She reported that the lesion had been present since approximately 4 years of age. The patient denied spontaneous pain but described increased perspiration associated with the lesion, including occasions when she noted wet spots on her clothing overlying the area. Findings from the physical examination revealed a 6x5-cm, flesh-colored, palpable tumor in the left calf. Secretion of a clear fluid could be seen originating from the surface of the tumor, and hypertrichosis was present (Figures 1 and 2). A 4-mm punch biopsy of the mass was performed, and results confirmed the diagnosis of EAH (Figure 3). Results of histopathologic examination revealed an unremarkable epidermis. An increased number of sweat glands and terminal hair follicles were found in the dermis, and dilated sweat ducts were noted in the papillary dermis. In addition, large dilated blood vessels were seen in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Intercellular mucin also was present in the dermal stroma. The constellation of clinical and pathologic features was consistent with the diagnosis of EAH.

The patient declined further diagnostic radiographic evaluation and surgical treatment. She was treated symptomatically for the hypertrichosis and hyperhidrosis, using 13.9% eflornithine cream and topical aluminum chloride, respectively.

Comment

EAH is a rare, benign cutaneous hamartoma consisting of a proliferation of both eccrine glands and thin-walled vascular channels. First described by Lotzbeck in 18591 as an angiomatous-appearing lesion on the cheek of a child, the term EAH was coined by Hyman and coworkers2 in 1968. Since hyperhidrosis is a relatively common finding associated with this condition, various other terms have been used to describe this entity, including sudoriparous angioma3 and functioning sudoriparous angiomatous hamartoma.4 In addition to presenting an additional case of EAH, we review the other 41 cases of EAH reported in the literature (Table 1).

Typically, EAH presents as a solitary, flesh-colored, blue-brown, or reddish papule, plaque, or nodule. However, unusual morphologic variants exist and include hyperkeratotic5 and verrucous6 lesions. There appears to be no gender predilection, and the male-female ratio in the data analyzed was 1:1.1. EAH usually occurs as a solitary lesion, but cases with multiple lesions have been reported and account for approximately 26% of all cases in the literature.3,7-13 The hamartoma often appears at birth2,3,6,9,10,13-22,25 or during early childhood,7,8,16,22-24 as in the present case. In the cases reviewed that were not congenital, the mean age at the time of diagnosis was approximately 21 years, and the range was between 2 months and 73 years. EAH occurs most frequently on the acral areas and, in our review, approximately 74% of all reported lesions were limited to the extremities. However, lesions also have been reported in the sacral region,26 on the buttocks,5,19 face,9 chest,8,13,15,24 or diffusely over multiple anatomic sites.12 EAH is usually asymptomatic, but the most commonly associated symptoms are pain and hyperhidrosis reported in approximately 42% and 32% of all cases analyzed, respectively, including the present case. Approximately 17% of patients with EAH reported both pain and hyperhidrosis (sweating) simultaneously (Table 2). It is postulated that infiltration of small nerves may be responsible for the pain,27,28 and a local increase in the temperature within the angioma may produce the sweating seen in the eccrine component of the hamartoma.3,8,16,27

The diagnosis of EAH is confirmed by histology because the clinical features of the lesion are nonspecific and variable. Histologically, EAH is characterized by a dermal proliferation of well-differentiated eccrine secretory and ductal elements closely associated with thin-walled angiomatous channels. In addition to these defining elements, unusual histopathologic variants have been reported and include the infiltration of adipose tissue,11,16,29 the presence of pilar structures,6,9,11,21 apocrine glands,8 and, as in our case, increased dermal mucin.11 The epidermis typically is unremarkable but may exhibit hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis.5,6 Immunohistochemical analyses using carcinoembryonic antigen and S-100 have demonstrated no difference between normal eccrine glands and those found in the hamartoma.8,10,16 In addition, ulex europaeus, CD34, CD44, and factor VIII–related antigens are expressed by the endothelial cells within the vascular component of the lesion.8,15,16 These findings help support a hamartomatous rather than tumoral origin for EAH. In addition, cytologic atypia and mitotic figures have not been reported.9,29

Imaging modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound, are beginning to be used in the evaluation of EAH. One group of investigators reports that ultrasonography of a biopsy-proven EAH revealed varicose veins in cutaneous and subcutaneous layers but could not determine the size or shape of the lesion.30 Now, radiographic imaging may help confirm the clinical suspicion of an angiomatous lesion, but accurate diagnosis of EAH remains with histology.

The etiology of EAH has not been delineated clearly. Zeller and Goldman6 report that the hamartoma may be caused by abnormal induction of heterotypic dependency during organogenesis. According to this model, altered chemical interactions between the differentiating epithelium and mesenchyme result in the hamartomatous growth of these elements, generating an abnormal proliferation of vascular and eccrine structures.

The differential diagnosis of EAH includes eccrine nevus,32 a rare lesion composed of mature eccrine glands capable of producing localized hyperhidrosis. In addition, localized hyperhidrosis may be seen in a variety of other conditions, including neuritis, myelitis, syringomyelia, general paresis, and tabes dorsalis.32 However, these conditions do not produce cutaneous lesions or histologic abnormalities of eccrine glands. Localized hyperhidrosis also may accompany the blue rubber-bleb nevus syndrome, but histology may distinguish EAH from this disorder. Likewise, EAH clinically may resemble tufted angioma, macular telangiectatic mastocytosis, nevus flammeus, glomus tumor, and smooth muscle hamartoma.9,22,25 These conditions are readily differentiated by histologic analysis.

EAH is a benign and typically slow-growing lesion, though a rapid increase in size was noted in one pregnant woman, indicating that it may be under hormonal influence.31 In this case, partial amputation of the involved finger was necessary to relieve the patient's intractable pain. In general, however, aggressive treatment of EAH is unwarranted. Simple excision usually is curative and reserved for painful or cosmetically unacceptable lesions. One study reports no evidence of recurrent disease 15 months after excision.17 Indeed, the pain associated with EAH may remit spontaneously without treatment, even after several years.28

- Lotzbeck C. Ein Fall von Schweissdrüsengeschwulst an der Wauge. Virchow Arch Pathol Anat. 1859;16:160

- Hyman AB, Harris H, Brownstein MH. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. N Y State J Med. 1968;68:2803-2806.

- Domonkos AN, Suarez LS. Sudoriparous angioma. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:552-553.

- Issa O. Hamartoma angiomatoso sudoriparo funcionante. Actas Dermo Sifiliogr. 1964;55:361-365.

- Tsuji T, Sawada H. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with verrucous features. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:167-169.

- Zeller DJ, Goldman RL. Eccrine-pilar angiomatous hamartoma: report of a unique case. Dermatologica. 1971;143:100-104.

- Morrell DS, Ghali FE, Stahr BJ, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a report of symmetric and painful lesions of the wrists. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:117-119.

- Sulica RL, Kao GF, Sulica VI, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (nevus): immunohistochemical findings and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:71-75.

- Aloi F, Tomasini C, Pippione M. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a multiple variant. Dermatology. 1992;184:219-222.

- Cebreiro C, Sanchez-Aguilar D, Centeno PG, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of seven cases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:267-270.

- Seraly MP, Magee K, Abell E, et al. Eccrine-angiomatous nevus, a new variant. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:274-275.

- Archer BW. Multiple cavernous angiomata of the sweat ducts associated with hemiplegia. Lancet. 1927;17:595-596.

- Lee SY, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Congenital eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of two patients. J Dermatol. 2001;28:338-340.

- Sanmartin O, Botella R, Alegre R, et al. Congenital eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:161-164.

- Kwon OC, Oh ST, Kim SW, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:787-789.

- Smith VC, Montesinos E, Revert A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of three patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:139-142.

- Calderone DC, Glass LF, Seleznick M, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:837-838.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Torres JE, Martin RF, Sanchez JL. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. P R Health Sci J. 1994:13:159-160.

- Kikuchi I, Kuroki Y, Inoue S. Painful eccrine angiomatous nevus on the sole. J Dermatol. 1982;9:329-332.

- Velasco JA, Almeida V. Eccrine-pilar angiomatous nevus. Dermatologica. 1988;177:317-322.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is a benign and uncommon malformation, characterized by increased numbers of eccrine (sweat) glands and numerous capillary channels. It is usually congenital or arises during the prepubertal years; the lesion only rarely presents during adulthood. The color of EAH may be flesh colored, blue-brown, or reddish and may occur as a nodule, plaque, or, less commonly, a macule. In most cases, EAH arises as a single lesion on the extremity, though reports of multiple lesions and those occurring in more unusual sites exist. The symptoms most commonly associated with EAH are pain and hyperhidrosis; enlargement may occur and is usually in concordance with the growth of the patient. It is important to recognize the hamartoma as a benign clinical entity, for which aggressive management is not necessary. In this article, we report a case of EAH occurring in a young girl, and we review 41 well-documented cases in the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 12-year-old previously healthy Hispanic girl presented with a lesion on the posterior aspect of her left lower leg. She reported that the lesion had been present since approximately 4 years of age. The patient denied spontaneous pain but described increased perspiration associated with the lesion, including occasions when she noted wet spots on her clothing overlying the area. Findings from the physical examination revealed a 6x5-cm, flesh-colored, palpable tumor in the left calf. Secretion of a clear fluid could be seen originating from the surface of the tumor, and hypertrichosis was present (Figures 1 and 2). A 4-mm punch biopsy of the mass was performed, and results confirmed the diagnosis of EAH (Figure 3). Results of histopathologic examination revealed an unremarkable epidermis. An increased number of sweat glands and terminal hair follicles were found in the dermis, and dilated sweat ducts were noted in the papillary dermis. In addition, large dilated blood vessels were seen in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Intercellular mucin also was present in the dermal stroma. The constellation of clinical and pathologic features was consistent with the diagnosis of EAH.

The patient declined further diagnostic radiographic evaluation and surgical treatment. She was treated symptomatically for the hypertrichosis and hyperhidrosis, using 13.9% eflornithine cream and topical aluminum chloride, respectively.

Comment

EAH is a rare, benign cutaneous hamartoma consisting of a proliferation of both eccrine glands and thin-walled vascular channels. First described by Lotzbeck in 18591 as an angiomatous-appearing lesion on the cheek of a child, the term EAH was coined by Hyman and coworkers2 in 1968. Since hyperhidrosis is a relatively common finding associated with this condition, various other terms have been used to describe this entity, including sudoriparous angioma3 and functioning sudoriparous angiomatous hamartoma.4 In addition to presenting an additional case of EAH, we review the other 41 cases of EAH reported in the literature (Table 1).

Typically, EAH presents as a solitary, flesh-colored, blue-brown, or reddish papule, plaque, or nodule. However, unusual morphologic variants exist and include hyperkeratotic5 and verrucous6 lesions. There appears to be no gender predilection, and the male-female ratio in the data analyzed was 1:1.1. EAH usually occurs as a solitary lesion, but cases with multiple lesions have been reported and account for approximately 26% of all cases in the literature.3,7-13 The hamartoma often appears at birth2,3,6,9,10,13-22,25 or during early childhood,7,8,16,22-24 as in the present case. In the cases reviewed that were not congenital, the mean age at the time of diagnosis was approximately 21 years, and the range was between 2 months and 73 years. EAH occurs most frequently on the acral areas and, in our review, approximately 74% of all reported lesions were limited to the extremities. However, lesions also have been reported in the sacral region,26 on the buttocks,5,19 face,9 chest,8,13,15,24 or diffusely over multiple anatomic sites.12 EAH is usually asymptomatic, but the most commonly associated symptoms are pain and hyperhidrosis reported in approximately 42% and 32% of all cases analyzed, respectively, including the present case. Approximately 17% of patients with EAH reported both pain and hyperhidrosis (sweating) simultaneously (Table 2). It is postulated that infiltration of small nerves may be responsible for the pain,27,28 and a local increase in the temperature within the angioma may produce the sweating seen in the eccrine component of the hamartoma.3,8,16,27

The diagnosis of EAH is confirmed by histology because the clinical features of the lesion are nonspecific and variable. Histologically, EAH is characterized by a dermal proliferation of well-differentiated eccrine secretory and ductal elements closely associated with thin-walled angiomatous channels. In addition to these defining elements, unusual histopathologic variants have been reported and include the infiltration of adipose tissue,11,16,29 the presence of pilar structures,6,9,11,21 apocrine glands,8 and, as in our case, increased dermal mucin.11 The epidermis typically is unremarkable but may exhibit hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis.5,6 Immunohistochemical analyses using carcinoembryonic antigen and S-100 have demonstrated no difference between normal eccrine glands and those found in the hamartoma.8,10,16 In addition, ulex europaeus, CD34, CD44, and factor VIII–related antigens are expressed by the endothelial cells within the vascular component of the lesion.8,15,16 These findings help support a hamartomatous rather than tumoral origin for EAH. In addition, cytologic atypia and mitotic figures have not been reported.9,29

Imaging modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound, are beginning to be used in the evaluation of EAH. One group of investigators reports that ultrasonography of a biopsy-proven EAH revealed varicose veins in cutaneous and subcutaneous layers but could not determine the size or shape of the lesion.30 Now, radiographic imaging may help confirm the clinical suspicion of an angiomatous lesion, but accurate diagnosis of EAH remains with histology.

The etiology of EAH has not been delineated clearly. Zeller and Goldman6 report that the hamartoma may be caused by abnormal induction of heterotypic dependency during organogenesis. According to this model, altered chemical interactions between the differentiating epithelium and mesenchyme result in the hamartomatous growth of these elements, generating an abnormal proliferation of vascular and eccrine structures.

The differential diagnosis of EAH includes eccrine nevus,32 a rare lesion composed of mature eccrine glands capable of producing localized hyperhidrosis. In addition, localized hyperhidrosis may be seen in a variety of other conditions, including neuritis, myelitis, syringomyelia, general paresis, and tabes dorsalis.32 However, these conditions do not produce cutaneous lesions or histologic abnormalities of eccrine glands. Localized hyperhidrosis also may accompany the blue rubber-bleb nevus syndrome, but histology may distinguish EAH from this disorder. Likewise, EAH clinically may resemble tufted angioma, macular telangiectatic mastocytosis, nevus flammeus, glomus tumor, and smooth muscle hamartoma.9,22,25 These conditions are readily differentiated by histologic analysis.

EAH is a benign and typically slow-growing lesion, though a rapid increase in size was noted in one pregnant woman, indicating that it may be under hormonal influence.31 In this case, partial amputation of the involved finger was necessary to relieve the patient's intractable pain. In general, however, aggressive treatment of EAH is unwarranted. Simple excision usually is curative and reserved for painful or cosmetically unacceptable lesions. One study reports no evidence of recurrent disease 15 months after excision.17 Indeed, the pain associated with EAH may remit spontaneously without treatment, even after several years.28

Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (EAH) is a benign and uncommon malformation, characterized by increased numbers of eccrine (sweat) glands and numerous capillary channels. It is usually congenital or arises during the prepubertal years; the lesion only rarely presents during adulthood. The color of EAH may be flesh colored, blue-brown, or reddish and may occur as a nodule, plaque, or, less commonly, a macule. In most cases, EAH arises as a single lesion on the extremity, though reports of multiple lesions and those occurring in more unusual sites exist. The symptoms most commonly associated with EAH are pain and hyperhidrosis; enlargement may occur and is usually in concordance with the growth of the patient. It is important to recognize the hamartoma as a benign clinical entity, for which aggressive management is not necessary. In this article, we report a case of EAH occurring in a young girl, and we review 41 well-documented cases in the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 12-year-old previously healthy Hispanic girl presented with a lesion on the posterior aspect of her left lower leg. She reported that the lesion had been present since approximately 4 years of age. The patient denied spontaneous pain but described increased perspiration associated with the lesion, including occasions when she noted wet spots on her clothing overlying the area. Findings from the physical examination revealed a 6x5-cm, flesh-colored, palpable tumor in the left calf. Secretion of a clear fluid could be seen originating from the surface of the tumor, and hypertrichosis was present (Figures 1 and 2). A 4-mm punch biopsy of the mass was performed, and results confirmed the diagnosis of EAH (Figure 3). Results of histopathologic examination revealed an unremarkable epidermis. An increased number of sweat glands and terminal hair follicles were found in the dermis, and dilated sweat ducts were noted in the papillary dermis. In addition, large dilated blood vessels were seen in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Intercellular mucin also was present in the dermal stroma. The constellation of clinical and pathologic features was consistent with the diagnosis of EAH.

The patient declined further diagnostic radiographic evaluation and surgical treatment. She was treated symptomatically for the hypertrichosis and hyperhidrosis, using 13.9% eflornithine cream and topical aluminum chloride, respectively.

Comment

EAH is a rare, benign cutaneous hamartoma consisting of a proliferation of both eccrine glands and thin-walled vascular channels. First described by Lotzbeck in 18591 as an angiomatous-appearing lesion on the cheek of a child, the term EAH was coined by Hyman and coworkers2 in 1968. Since hyperhidrosis is a relatively common finding associated with this condition, various other terms have been used to describe this entity, including sudoriparous angioma3 and functioning sudoriparous angiomatous hamartoma.4 In addition to presenting an additional case of EAH, we review the other 41 cases of EAH reported in the literature (Table 1).

Typically, EAH presents as a solitary, flesh-colored, blue-brown, or reddish papule, plaque, or nodule. However, unusual morphologic variants exist and include hyperkeratotic5 and verrucous6 lesions. There appears to be no gender predilection, and the male-female ratio in the data analyzed was 1:1.1. EAH usually occurs as a solitary lesion, but cases with multiple lesions have been reported and account for approximately 26% of all cases in the literature.3,7-13 The hamartoma often appears at birth2,3,6,9,10,13-22,25 or during early childhood,7,8,16,22-24 as in the present case. In the cases reviewed that were not congenital, the mean age at the time of diagnosis was approximately 21 years, and the range was between 2 months and 73 years. EAH occurs most frequently on the acral areas and, in our review, approximately 74% of all reported lesions were limited to the extremities. However, lesions also have been reported in the sacral region,26 on the buttocks,5,19 face,9 chest,8,13,15,24 or diffusely over multiple anatomic sites.12 EAH is usually asymptomatic, but the most commonly associated symptoms are pain and hyperhidrosis reported in approximately 42% and 32% of all cases analyzed, respectively, including the present case. Approximately 17% of patients with EAH reported both pain and hyperhidrosis (sweating) simultaneously (Table 2). It is postulated that infiltration of small nerves may be responsible for the pain,27,28 and a local increase in the temperature within the angioma may produce the sweating seen in the eccrine component of the hamartoma.3,8,16,27

The diagnosis of EAH is confirmed by histology because the clinical features of the lesion are nonspecific and variable. Histologically, EAH is characterized by a dermal proliferation of well-differentiated eccrine secretory and ductal elements closely associated with thin-walled angiomatous channels. In addition to these defining elements, unusual histopathologic variants have been reported and include the infiltration of adipose tissue,11,16,29 the presence of pilar structures,6,9,11,21 apocrine glands,8 and, as in our case, increased dermal mucin.11 The epidermis typically is unremarkable but may exhibit hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and papillomatosis.5,6 Immunohistochemical analyses using carcinoembryonic antigen and S-100 have demonstrated no difference between normal eccrine glands and those found in the hamartoma.8,10,16 In addition, ulex europaeus, CD34, CD44, and factor VIII–related antigens are expressed by the endothelial cells within the vascular component of the lesion.8,15,16 These findings help support a hamartomatous rather than tumoral origin for EAH. In addition, cytologic atypia and mitotic figures have not been reported.9,29

Imaging modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound, are beginning to be used in the evaluation of EAH. One group of investigators reports that ultrasonography of a biopsy-proven EAH revealed varicose veins in cutaneous and subcutaneous layers but could not determine the size or shape of the lesion.30 Now, radiographic imaging may help confirm the clinical suspicion of an angiomatous lesion, but accurate diagnosis of EAH remains with histology.

The etiology of EAH has not been delineated clearly. Zeller and Goldman6 report that the hamartoma may be caused by abnormal induction of heterotypic dependency during organogenesis. According to this model, altered chemical interactions between the differentiating epithelium and mesenchyme result in the hamartomatous growth of these elements, generating an abnormal proliferation of vascular and eccrine structures.

The differential diagnosis of EAH includes eccrine nevus,32 a rare lesion composed of mature eccrine glands capable of producing localized hyperhidrosis. In addition, localized hyperhidrosis may be seen in a variety of other conditions, including neuritis, myelitis, syringomyelia, general paresis, and tabes dorsalis.32 However, these conditions do not produce cutaneous lesions or histologic abnormalities of eccrine glands. Localized hyperhidrosis also may accompany the blue rubber-bleb nevus syndrome, but histology may distinguish EAH from this disorder. Likewise, EAH clinically may resemble tufted angioma, macular telangiectatic mastocytosis, nevus flammeus, glomus tumor, and smooth muscle hamartoma.9,22,25 These conditions are readily differentiated by histologic analysis.

EAH is a benign and typically slow-growing lesion, though a rapid increase in size was noted in one pregnant woman, indicating that it may be under hormonal influence.31 In this case, partial amputation of the involved finger was necessary to relieve the patient's intractable pain. In general, however, aggressive treatment of EAH is unwarranted. Simple excision usually is curative and reserved for painful or cosmetically unacceptable lesions. One study reports no evidence of recurrent disease 15 months after excision.17 Indeed, the pain associated with EAH may remit spontaneously without treatment, even after several years.28

- Lotzbeck C. Ein Fall von Schweissdrüsengeschwulst an der Wauge. Virchow Arch Pathol Anat. 1859;16:160

- Hyman AB, Harris H, Brownstein MH. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. N Y State J Med. 1968;68:2803-2806.

- Domonkos AN, Suarez LS. Sudoriparous angioma. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:552-553.

- Issa O. Hamartoma angiomatoso sudoriparo funcionante. Actas Dermo Sifiliogr. 1964;55:361-365.

- Tsuji T, Sawada H. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with verrucous features. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:167-169.

- Zeller DJ, Goldman RL. Eccrine-pilar angiomatous hamartoma: report of a unique case. Dermatologica. 1971;143:100-104.

- Morrell DS, Ghali FE, Stahr BJ, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a report of symmetric and painful lesions of the wrists. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:117-119.

- Sulica RL, Kao GF, Sulica VI, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (nevus): immunohistochemical findings and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:71-75.

- Aloi F, Tomasini C, Pippione M. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a multiple variant. Dermatology. 1992;184:219-222.

- Cebreiro C, Sanchez-Aguilar D, Centeno PG, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of seven cases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:267-270.

- Seraly MP, Magee K, Abell E, et al. Eccrine-angiomatous nevus, a new variant. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:274-275.

- Archer BW. Multiple cavernous angiomata of the sweat ducts associated with hemiplegia. Lancet. 1927;17:595-596.

- Lee SY, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Congenital eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of two patients. J Dermatol. 2001;28:338-340.

- Sanmartin O, Botella R, Alegre R, et al. Congenital eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:161-164.

- Kwon OC, Oh ST, Kim SW, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:787-789.

- Smith VC, Montesinos E, Revert A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of three patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:139-142.

- Calderone DC, Glass LF, Seleznick M, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:837-838.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Torres JE, Martin RF, Sanchez JL. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. P R Health Sci J. 1994:13:159-160.

- Kikuchi I, Kuroki Y, Inoue S. Painful eccrine angiomatous nevus on the sole. J Dermatol. 1982;9:329-332.

- Velasco JA, Almeida V. Eccrine-pilar angiomatous nevus. Dermatologica. 1988;177:317-322.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol

- Lotzbeck C. Ein Fall von Schweissdrüsengeschwulst an der Wauge. Virchow Arch Pathol Anat. 1859;16:160

- Hyman AB, Harris H, Brownstein MH. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. N Y State J Med. 1968;68:2803-2806.

- Domonkos AN, Suarez LS. Sudoriparous angioma. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:552-553.

- Issa O. Hamartoma angiomatoso sudoriparo funcionante. Actas Dermo Sifiliogr. 1964;55:361-365.

- Tsuji T, Sawada H. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma with verrucous features. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:167-169.

- Zeller DJ, Goldman RL. Eccrine-pilar angiomatous hamartoma: report of a unique case. Dermatologica. 1971;143:100-104.

- Morrell DS, Ghali FE, Stahr BJ, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a report of symmetric and painful lesions of the wrists. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:117-119.

- Sulica RL, Kao GF, Sulica VI, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma (nevus): immunohistochemical findings and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:71-75.

- Aloi F, Tomasini C, Pippione M. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: a multiple variant. Dermatology. 1992;184:219-222.

- Cebreiro C, Sanchez-Aguilar D, Centeno PG, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of seven cases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:267-270.

- Seraly MP, Magee K, Abell E, et al. Eccrine-angiomatous nevus, a new variant. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:274-275.

- Archer BW. Multiple cavernous angiomata of the sweat ducts associated with hemiplegia. Lancet. 1927;17:595-596.

- Lee SY, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Congenital eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of two patients. J Dermatol. 2001;28:338-340.

- Sanmartin O, Botella R, Alegre R, et al. Congenital eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:161-164.

- Kwon OC, Oh ST, Kim SW, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:787-789.

- Smith VC, Montesinos E, Revert A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of three patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:139-142.

- Calderone DC, Glass LF, Seleznick M, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:837-838.

- Nakatsui TC, Schloss E, Krol A, et al. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma: report of a case and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:109-111.

- Torres JE, Martin RF, Sanchez JL. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. P R Health Sci J. 1994:13:159-160.

- Kikuchi I, Kuroki Y, Inoue S. Painful eccrine angiomatous nevus on the sole. J Dermatol. 1982;9:329-332.

- Velasco JA, Almeida V. Eccrine-pilar angiomatous nevus. Dermatologica. 1988;177:317-322.

- Pelle MT, Pride HB, Tyler WB. Eccrine angiomatous hamartoma. J Am Acad Dermatol