User login

What Is Your Diagnosis? Onychomadesis Following Hand-foot-and-mouth Disease

The Diagnosis: Onychomadesis Following Hand-foot-and-mouth Disease

In 1846, Joseph Honoré Simon Beau described specific diagnostic signs manifested in the nails during various disease states.1 He suggested that the width of the nail plate depression correlated with the duration of illness. Since then, the correlation of nail changes during times of illness has been confirmed. The term Beau lines currently is used to describe transverse ridging of the nail plate due to transient arrest in nail plate formation.1 Onychomadesis is believed to be an extreme form of Beau lines in which the whole thickness of the nail plate is affected, resulting in its separation from the proximal nail fold and shedding of the nail plate.

Nail plate detachment in onychomadesis is due to a severe insult that results in complete arrest of the nail matrix activity. Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.2 Trauma is the leading cause of single-digit onychomadesis, while multiple-digit onychomadesis usually is caused by a systemic disease (eg, blistering illnesses). Cases of multiple-nail onychomadesis have been reported following hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), though the majority of cases of HFMD do not present with onychomadesis.

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is most commonly caused by 2 types of intestinal strains of Human enterovirus A: (1) coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6) or A16 (CVA16) and (2) enterovirus 71.3,4 Symptoms of HFMD include fever and sore throat followed by the development of oral ulcerations 1 to 2 days later. A vesicular or maculopapular rash can then develop on the hands, feet, and mouth. Complications following HFMD are rare but can include encephalitis, meningitis, and pneumonia. Symptoms typically resolve after 6 days without any treatment.3

A cluster of onychomadesis cases following HFMD outbreaks have been reported in Europe, Asia, and the United States. In some reports, causative viral strains have been identified. After a national HFMD outbreak in Finland in fall 2008, investigators isolated strains of CVA6 in the shedded nails of sibling patients.4 The CVA6 strain was found to be the primary pathogen causing that particular HFMD outbreak and onychomadesis was a hallmark presentation of this viral epidemic. Previously, HFMD outbreaks were known to be caused by CVA16 or enterovirus 71, with enterovirus 71 strains occurring mostly in Southeast Asia and Australia.4 In a report from Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis after CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) as compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains. Among patients with onychomadesis, 69% (33/48) were reported to experience concurrent palmoplantar desquamation before or during presentation of nail changes.5

Another Finnish study investigated an atypical outbreak of HFMD that occurred primarily in adult patients.6 Many of these patients also had onychomadesis several weeks following HFMD. Of 317 cases, human enteroviruses were detected in specimens from 212 cases (67%), including both children and adults. Two human enterovirus types—CVA6 (71% [83/117]) and coxsackievirus A10 (28% [33/117])—were identified as the causative agents of the outbreak. One genetic variant of CVA6 predominated, but 3 other genetically distinct CVA6 strains also were found.6 The 2008 HFMD outbreak in Finland was found to be caused by 2 concomitantly circulating human enteroviruses, which up until now have been infrequently detected together as causative agents of HFMD. Onychomadesis was a common occurrence in the Finnish HFMD outbreak, which has been previously linked to CVA6. The co-circulation of CVA6 and coxsackievirus A10 suggests an endemic emergence of new genetic variants of these enteroviruses.6

There also have been several reports of onychomadesis outbreaks in Spain, 2 of which occurred in nursery settings. One report noted that patients with a history of HFMD were 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).3 There also was a noted difference in prevalence of onychomadesis regarding age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (33–42 months). Occurrence of onychomadesis and nail plate changes was observed on average 40 days after HFMD, and an average of 4 nails were shed per case.3 A report investigating a separate HFMD outbreak in Spain found a high percentage of onychomadesis (96% [298/311]) occurring in children younger than 6 years. This outbreak, which occurred in the metropolitan area of Valencia, was associated with an outbreak of HFMD primarily caused by coxsackievirus A10.7 A third Spanish study uncovered a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting as a consequence of HFMD, where 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases were preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.8

A case series reported in Chicago, Illinois, in the late 1990s identified 5 pediatric patients with HFMD associated with Beau lines and onychomadesis.1 Only 3 of 5 (60%) patients had a fever; therefore, fever-induced nail matrix arrest was ruled out as the inciting factor of the nail changes seen. All patients were given over-the-counter analgesics and 2 received antibiotics (amoxicillin for the first 48 hours). None of these medications have been implicated as plausible causes of nail matrix arrest. Two patients were siblings and the rest were not related. None of the patients had a history of close physical proximity (eg, attendance at the same day care or school). All 5 patients developed HFMD within 4 weeks of one another, and all were from the suburbs of Chicago (with 4 of 5 [80%] patients living within a 60-mile radius of each other). Although the causative viral strain was not isolated, the authors concluded that all the patients were likely to have been infected by the same virus due to the general vicinity of the patients to each other. Furthermore, the collective case reports likely represented an HFMD epidemic caused by a particular strain that can induce onychomadesis.1

Supportive care for the viral illness paired with protection of the nail bed until new nail growth occurs is ideal, which requires maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails.

Onychomadesis can follow HFMD, especially in cases caused by CVA6. Cases of onychomadesis are mild and self-limited. When onychomadesis is noted, historical review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to nail changes often will identify the causative disease.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM. Nail disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2012:1130-1131.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Blomqvist S, Klemola P, Kaijalainen S, et al. Co-circulation of coxsackieviruses A6 and A10 in hand, foot and mouth disease outbreak in Finland. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:49-54.

- Davia JL, Bel PH, Ninet VZ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain, associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by enteroviruses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:1-5.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

The Diagnosis: Onychomadesis Following Hand-foot-and-mouth Disease

In 1846, Joseph Honoré Simon Beau described specific diagnostic signs manifested in the nails during various disease states.1 He suggested that the width of the nail plate depression correlated with the duration of illness. Since then, the correlation of nail changes during times of illness has been confirmed. The term Beau lines currently is used to describe transverse ridging of the nail plate due to transient arrest in nail plate formation.1 Onychomadesis is believed to be an extreme form of Beau lines in which the whole thickness of the nail plate is affected, resulting in its separation from the proximal nail fold and shedding of the nail plate.

Nail plate detachment in onychomadesis is due to a severe insult that results in complete arrest of the nail matrix activity. Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.2 Trauma is the leading cause of single-digit onychomadesis, while multiple-digit onychomadesis usually is caused by a systemic disease (eg, blistering illnesses). Cases of multiple-nail onychomadesis have been reported following hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), though the majority of cases of HFMD do not present with onychomadesis.

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is most commonly caused by 2 types of intestinal strains of Human enterovirus A: (1) coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6) or A16 (CVA16) and (2) enterovirus 71.3,4 Symptoms of HFMD include fever and sore throat followed by the development of oral ulcerations 1 to 2 days later. A vesicular or maculopapular rash can then develop on the hands, feet, and mouth. Complications following HFMD are rare but can include encephalitis, meningitis, and pneumonia. Symptoms typically resolve after 6 days without any treatment.3

A cluster of onychomadesis cases following HFMD outbreaks have been reported in Europe, Asia, and the United States. In some reports, causative viral strains have been identified. After a national HFMD outbreak in Finland in fall 2008, investigators isolated strains of CVA6 in the shedded nails of sibling patients.4 The CVA6 strain was found to be the primary pathogen causing that particular HFMD outbreak and onychomadesis was a hallmark presentation of this viral epidemic. Previously, HFMD outbreaks were known to be caused by CVA16 or enterovirus 71, with enterovirus 71 strains occurring mostly in Southeast Asia and Australia.4 In a report from Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis after CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) as compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains. Among patients with onychomadesis, 69% (33/48) were reported to experience concurrent palmoplantar desquamation before or during presentation of nail changes.5

Another Finnish study investigated an atypical outbreak of HFMD that occurred primarily in adult patients.6 Many of these patients also had onychomadesis several weeks following HFMD. Of 317 cases, human enteroviruses were detected in specimens from 212 cases (67%), including both children and adults. Two human enterovirus types—CVA6 (71% [83/117]) and coxsackievirus A10 (28% [33/117])—were identified as the causative agents of the outbreak. One genetic variant of CVA6 predominated, but 3 other genetically distinct CVA6 strains also were found.6 The 2008 HFMD outbreak in Finland was found to be caused by 2 concomitantly circulating human enteroviruses, which up until now have been infrequently detected together as causative agents of HFMD. Onychomadesis was a common occurrence in the Finnish HFMD outbreak, which has been previously linked to CVA6. The co-circulation of CVA6 and coxsackievirus A10 suggests an endemic emergence of new genetic variants of these enteroviruses.6

There also have been several reports of onychomadesis outbreaks in Spain, 2 of which occurred in nursery settings. One report noted that patients with a history of HFMD were 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).3 There also was a noted difference in prevalence of onychomadesis regarding age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (33–42 months). Occurrence of onychomadesis and nail plate changes was observed on average 40 days after HFMD, and an average of 4 nails were shed per case.3 A report investigating a separate HFMD outbreak in Spain found a high percentage of onychomadesis (96% [298/311]) occurring in children younger than 6 years. This outbreak, which occurred in the metropolitan area of Valencia, was associated with an outbreak of HFMD primarily caused by coxsackievirus A10.7 A third Spanish study uncovered a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting as a consequence of HFMD, where 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases were preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.8

A case series reported in Chicago, Illinois, in the late 1990s identified 5 pediatric patients with HFMD associated with Beau lines and onychomadesis.1 Only 3 of 5 (60%) patients had a fever; therefore, fever-induced nail matrix arrest was ruled out as the inciting factor of the nail changes seen. All patients were given over-the-counter analgesics and 2 received antibiotics (amoxicillin for the first 48 hours). None of these medications have been implicated as plausible causes of nail matrix arrest. Two patients were siblings and the rest were not related. None of the patients had a history of close physical proximity (eg, attendance at the same day care or school). All 5 patients developed HFMD within 4 weeks of one another, and all were from the suburbs of Chicago (with 4 of 5 [80%] patients living within a 60-mile radius of each other). Although the causative viral strain was not isolated, the authors concluded that all the patients were likely to have been infected by the same virus due to the general vicinity of the patients to each other. Furthermore, the collective case reports likely represented an HFMD epidemic caused by a particular strain that can induce onychomadesis.1

Supportive care for the viral illness paired with protection of the nail bed until new nail growth occurs is ideal, which requires maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails.

Onychomadesis can follow HFMD, especially in cases caused by CVA6. Cases of onychomadesis are mild and self-limited. When onychomadesis is noted, historical review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to nail changes often will identify the causative disease.

The Diagnosis: Onychomadesis Following Hand-foot-and-mouth Disease

In 1846, Joseph Honoré Simon Beau described specific diagnostic signs manifested in the nails during various disease states.1 He suggested that the width of the nail plate depression correlated with the duration of illness. Since then, the correlation of nail changes during times of illness has been confirmed. The term Beau lines currently is used to describe transverse ridging of the nail plate due to transient arrest in nail plate formation.1 Onychomadesis is believed to be an extreme form of Beau lines in which the whole thickness of the nail plate is affected, resulting in its separation from the proximal nail fold and shedding of the nail plate.

Nail plate detachment in onychomadesis is due to a severe insult that results in complete arrest of the nail matrix activity. Onychomadesis has a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, ranging from mild transverse ridges of the nail plate (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding.2 Trauma is the leading cause of single-digit onychomadesis, while multiple-digit onychomadesis usually is caused by a systemic disease (eg, blistering illnesses). Cases of multiple-nail onychomadesis have been reported following hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD), though the majority of cases of HFMD do not present with onychomadesis.

Hand-foot-and-mouth disease is most commonly caused by 2 types of intestinal strains of Human enterovirus A: (1) coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6) or A16 (CVA16) and (2) enterovirus 71.3,4 Symptoms of HFMD include fever and sore throat followed by the development of oral ulcerations 1 to 2 days later. A vesicular or maculopapular rash can then develop on the hands, feet, and mouth. Complications following HFMD are rare but can include encephalitis, meningitis, and pneumonia. Symptoms typically resolve after 6 days without any treatment.3

A cluster of onychomadesis cases following HFMD outbreaks have been reported in Europe, Asia, and the United States. In some reports, causative viral strains have been identified. After a national HFMD outbreak in Finland in fall 2008, investigators isolated strains of CVA6 in the shedded nails of sibling patients.4 The CVA6 strain was found to be the primary pathogen causing that particular HFMD outbreak and onychomadesis was a hallmark presentation of this viral epidemic. Previously, HFMD outbreaks were known to be caused by CVA16 or enterovirus 71, with enterovirus 71 strains occurring mostly in Southeast Asia and Australia.4 In a report from Taiwan, the incidence of onychomadesis after CVA6 infection was 37% (48/130) as compared to 5% (7/145) in cases with non-CVA6 causative strains. Among patients with onychomadesis, 69% (33/48) were reported to experience concurrent palmoplantar desquamation before or during presentation of nail changes.5

Another Finnish study investigated an atypical outbreak of HFMD that occurred primarily in adult patients.6 Many of these patients also had onychomadesis several weeks following HFMD. Of 317 cases, human enteroviruses were detected in specimens from 212 cases (67%), including both children and adults. Two human enterovirus types—CVA6 (71% [83/117]) and coxsackievirus A10 (28% [33/117])—were identified as the causative agents of the outbreak. One genetic variant of CVA6 predominated, but 3 other genetically distinct CVA6 strains also were found.6 The 2008 HFMD outbreak in Finland was found to be caused by 2 concomitantly circulating human enteroviruses, which up until now have been infrequently detected together as causative agents of HFMD. Onychomadesis was a common occurrence in the Finnish HFMD outbreak, which has been previously linked to CVA6. The co-circulation of CVA6 and coxsackievirus A10 suggests an endemic emergence of new genetic variants of these enteroviruses.6

There also have been several reports of onychomadesis outbreaks in Spain, 2 of which occurred in nursery settings. One report noted that patients with a history of HFMD were 14 times more likely to develop onychomadesis (relative risk, 14; 95% confidence interval, 4.57-42.86).3 There also was a noted difference in prevalence of onychomadesis regarding age: a 55% (18/33) occurrence rate was noted in the youngest age group (9–23 months), 30% (8/27) in the middle age group (24–32 months), and 4% (1/28) in the oldest age group (33–42 months). Occurrence of onychomadesis and nail plate changes was observed on average 40 days after HFMD, and an average of 4 nails were shed per case.3 A report investigating a separate HFMD outbreak in Spain found a high percentage of onychomadesis (96% [298/311]) occurring in children younger than 6 years. This outbreak, which occurred in the metropolitan area of Valencia, was associated with an outbreak of HFMD primarily caused by coxsackievirus A10.7 A third Spanish study uncovered a high occurrence of onychomadesis in a nursery setting as a consequence of HFMD, where 92% (11/12) of onychomadesis cases were preceded by HFMD 2 months prior.8

A case series reported in Chicago, Illinois, in the late 1990s identified 5 pediatric patients with HFMD associated with Beau lines and onychomadesis.1 Only 3 of 5 (60%) patients had a fever; therefore, fever-induced nail matrix arrest was ruled out as the inciting factor of the nail changes seen. All patients were given over-the-counter analgesics and 2 received antibiotics (amoxicillin for the first 48 hours). None of these medications have been implicated as plausible causes of nail matrix arrest. Two patients were siblings and the rest were not related. None of the patients had a history of close physical proximity (eg, attendance at the same day care or school). All 5 patients developed HFMD within 4 weeks of one another, and all were from the suburbs of Chicago (with 4 of 5 [80%] patients living within a 60-mile radius of each other). Although the causative viral strain was not isolated, the authors concluded that all the patients were likely to have been infected by the same virus due to the general vicinity of the patients to each other. Furthermore, the collective case reports likely represented an HFMD epidemic caused by a particular strain that can induce onychomadesis.1

Supportive care for the viral illness paired with protection of the nail bed until new nail growth occurs is ideal, which requires maintaining short nails and using adhesive bandages over the affected nails to avoid snagging the nail or ripping off the partially attached nails.

Onychomadesis can follow HFMD, especially in cases caused by CVA6. Cases of onychomadesis are mild and self-limited. When onychomadesis is noted, historical review of viral illnesses within 1 to 2 months prior to nail changes often will identify the causative disease.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM. Nail disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2012:1130-1131.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Blomqvist S, Klemola P, Kaijalainen S, et al. Co-circulation of coxsackieviruses A6 and A10 in hand, foot and mouth disease outbreak in Finland. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:49-54.

- Davia JL, Bel PH, Ninet VZ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain, associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by enteroviruses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:1-5.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

- Clementz GC, Mancini AJ. Nail matrix arrest following hand-foot-mouth disease: a report of five children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:7-11.

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM. Nail disorders. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2012:1130-1131.

- Guimbao J, Rodrigo P, Alberto MJ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak linked to hand, foot, and mouth disease, Spain, July 2008. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19663.

- Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1485-1488.

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346.

- Blomqvist S, Klemola P, Kaijalainen S, et al. Co-circulation of coxsackieviruses A6 and A10 in hand, foot and mouth disease outbreak in Finland. J Clin Virol. 2010;48:49-54.

- Davia JL, Bel PH, Ninet VZ, et al. Onychomadesis outbreak in Valencia, Spain, associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by enteroviruses. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:1-5.

- Cabrerizo M, De Miguel T, Armada A, et al. Onychomadesis after a hand, foot, and mouth disease outbreak in Spain, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1775-1778.

Fragile Drug Development Process

We are currently in the midst of a new wave of drug developments and approvals for psoriasis; however, we recently have been reminded of the tenuous nature of bringing a new drug to market. Last month, Amgen Inc announced it was pulling out of the long-running collaboration on the high-profile IL-17 program after evaluating the likely commercial impact it would face in light of the suicidal thoughts some patients reported during the studies.

Brodalumab had successfully completed 3 phase 3 studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis known as the AMAGINE program. Top-line results from AMAGINE-1 comparing brodalumab with placebo were released in May 2014. Top-line results from AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab and placebo were announced in November 2014. AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 are identical in design. “During our preparation process for regulatory submissions, we came to believe that labeling requirements likely would limit the appropriate patient population for brodalumab,” said Amgen Executive Vice President of Research and Development Sean Harper in a statement. AstraZeneca must now decide whether to pursue brodalumab independently.

Once the exact data are publicly released, we will be able to better evaluate the issues of suicidal ideation involved.

What’s the issue?

Brodalumab was eagerly anticipated in the dermatology community. In an instant, the drug’s future is in doubt, which once again demonstrates the fragility of the drug development process. How will this recent announcement affect your use of new biologics?

We are currently in the midst of a new wave of drug developments and approvals for psoriasis; however, we recently have been reminded of the tenuous nature of bringing a new drug to market. Last month, Amgen Inc announced it was pulling out of the long-running collaboration on the high-profile IL-17 program after evaluating the likely commercial impact it would face in light of the suicidal thoughts some patients reported during the studies.

Brodalumab had successfully completed 3 phase 3 studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis known as the AMAGINE program. Top-line results from AMAGINE-1 comparing brodalumab with placebo were released in May 2014. Top-line results from AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab and placebo were announced in November 2014. AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 are identical in design. “During our preparation process for regulatory submissions, we came to believe that labeling requirements likely would limit the appropriate patient population for brodalumab,” said Amgen Executive Vice President of Research and Development Sean Harper in a statement. AstraZeneca must now decide whether to pursue brodalumab independently.

Once the exact data are publicly released, we will be able to better evaluate the issues of suicidal ideation involved.

What’s the issue?

Brodalumab was eagerly anticipated in the dermatology community. In an instant, the drug’s future is in doubt, which once again demonstrates the fragility of the drug development process. How will this recent announcement affect your use of new biologics?

We are currently in the midst of a new wave of drug developments and approvals for psoriasis; however, we recently have been reminded of the tenuous nature of bringing a new drug to market. Last month, Amgen Inc announced it was pulling out of the long-running collaboration on the high-profile IL-17 program after evaluating the likely commercial impact it would face in light of the suicidal thoughts some patients reported during the studies.

Brodalumab had successfully completed 3 phase 3 studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis known as the AMAGINE program. Top-line results from AMAGINE-1 comparing brodalumab with placebo were released in May 2014. Top-line results from AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab and placebo were announced in November 2014. AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3 are identical in design. “During our preparation process for regulatory submissions, we came to believe that labeling requirements likely would limit the appropriate patient population for brodalumab,” said Amgen Executive Vice President of Research and Development Sean Harper in a statement. AstraZeneca must now decide whether to pursue brodalumab independently.

Once the exact data are publicly released, we will be able to better evaluate the issues of suicidal ideation involved.

What’s the issue?

Brodalumab was eagerly anticipated in the dermatology community. In an instant, the drug’s future is in doubt, which once again demonstrates the fragility of the drug development process. How will this recent announcement affect your use of new biologics?

Corrona Begins

Over the last 15 years the treatment of psoriasis has been transformed with the advent of biologic agents. Now we have a whole new generation of treatments that is emerging. With all of these therapeutic options, the dermatologic community is in need of increasing data to help us further understand both the therapies and the disease state.

A new independent US psoriasis registry has been established. This registry is a joint collaboration with the National Psoriasis Foundation and Corrona, Inc (Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America, Inc). Data will be gathered through comprehensive questionnaires completed by patients and their dermatologists during appointments.

The registry will function to collect and analyze clinical data, and thereby allow investigators to achieve the following: (1) compare the safety and effectiveness of psoriasis treatments, (2) better understand psoriasis comorbidities, and (3) explore the natural history of the disease.

The registry will begin recruiting patients this year. Initially, the registry will track the drug safety reporting for secukinumab. The goal is for the CORRONA psoriasis registry to enroll at least 3000 patients with psoriasis who are taking secukinumab and then follow their treatment for at least 8 years.

In addition to studying safety and effectiveness of therapeutics, the registry also will help identify potential etiologies of psoriasis, study the relationship between psoriasis and other health conditions, and examine the impact of the condition on quality of life, among other outcomes.

To become an investigator in the registry or learn more about it, visit www.psoriasis.org/corrona-registry.

What’s the issue?

This registry is a welcomed addition to the study of psoriasis. It has the potential to add critical information in the years to come.

Over the last 15 years the treatment of psoriasis has been transformed with the advent of biologic agents. Now we have a whole new generation of treatments that is emerging. With all of these therapeutic options, the dermatologic community is in need of increasing data to help us further understand both the therapies and the disease state.

A new independent US psoriasis registry has been established. This registry is a joint collaboration with the National Psoriasis Foundation and Corrona, Inc (Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America, Inc). Data will be gathered through comprehensive questionnaires completed by patients and their dermatologists during appointments.

The registry will function to collect and analyze clinical data, and thereby allow investigators to achieve the following: (1) compare the safety and effectiveness of psoriasis treatments, (2) better understand psoriasis comorbidities, and (3) explore the natural history of the disease.

The registry will begin recruiting patients this year. Initially, the registry will track the drug safety reporting for secukinumab. The goal is for the CORRONA psoriasis registry to enroll at least 3000 patients with psoriasis who are taking secukinumab and then follow their treatment for at least 8 years.

In addition to studying safety and effectiveness of therapeutics, the registry also will help identify potential etiologies of psoriasis, study the relationship between psoriasis and other health conditions, and examine the impact of the condition on quality of life, among other outcomes.

To become an investigator in the registry or learn more about it, visit www.psoriasis.org/corrona-registry.

What’s the issue?

This registry is a welcomed addition to the study of psoriasis. It has the potential to add critical information in the years to come.

Over the last 15 years the treatment of psoriasis has been transformed with the advent of biologic agents. Now we have a whole new generation of treatments that is emerging. With all of these therapeutic options, the dermatologic community is in need of increasing data to help us further understand both the therapies and the disease state.

A new independent US psoriasis registry has been established. This registry is a joint collaboration with the National Psoriasis Foundation and Corrona, Inc (Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America, Inc). Data will be gathered through comprehensive questionnaires completed by patients and their dermatologists during appointments.

The registry will function to collect and analyze clinical data, and thereby allow investigators to achieve the following: (1) compare the safety and effectiveness of psoriasis treatments, (2) better understand psoriasis comorbidities, and (3) explore the natural history of the disease.

The registry will begin recruiting patients this year. Initially, the registry will track the drug safety reporting for secukinumab. The goal is for the CORRONA psoriasis registry to enroll at least 3000 patients with psoriasis who are taking secukinumab and then follow their treatment for at least 8 years.

In addition to studying safety and effectiveness of therapeutics, the registry also will help identify potential etiologies of psoriasis, study the relationship between psoriasis and other health conditions, and examine the impact of the condition on quality of life, among other outcomes.

To become an investigator in the registry or learn more about it, visit www.psoriasis.org/corrona-registry.

What’s the issue?

This registry is a welcomed addition to the study of psoriasis. It has the potential to add critical information in the years to come.

Novel Psoriasis Therapies and Patient Outcomes, Part 2: Biologic Treatments

Biologic agents that currently are in use for the management of moderate to severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) include the anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α monoclonal antibodies adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab1; however, additional TNF-α inhibitors as well as drugs targeting other pathways presently are in the pipeline. Novel biologic treatments currently in phase 2 through phase 4 clinical trials, including those that have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), are discussed in this article, and a summary is provided in Table 1.

Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors

Certolizumab Pegol

Certolizumab pegol (CZP; UCB, Inc), a pegylated TNF-α inhibitor, is unique in that it does not possess a fragment crystallizable (Fc) region and consequently does not trigger complement activation. The drug is presently FDA approved for active PsA, rheumatoid arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. One phase 2 study reported psoriasis area severity index (PASI) scores of 75 in 83% (48/58) of participants who received CZP 400 mg at week 0 and every other week until week 10 (P<.001 vs placebo).3 In a 24-week phase 3 study (known as RAPID-PsA), 409 participants were randomized into 3 study arms: (1) CZP 400 mg every 4 weeks; (2) CZP 200 mg every 2 weeks; (3) placebo every 2 weeks.4 Of note, 20% of participants had previously received a TNF inhibitor. The study demonstrated improvements in participant-reported outcomes with use of CZP regardless of prior TNF inhibitor use.4

CHS-0214

CHS-0214 (Coherus BioSciences, Inc) is a TNF-α inhibitor and etanercept biosimilar that has entered into a 48-week multicenter phase 3 trial (known as RaPsOdy) for patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. The purpose of the study is to compare PASI scores for CHS-0214 and etanercept to evaluate immunogenicity, safety, and effectiveness over a 12-week period.5 Comparable pharmacokinetics were established in an earlier study.6

Inhibition of the IL-12/IL-23 Pathway

IL-12 and IL-23 are cytokines with prostaglan-din E2–mediated production by dendritic cells that share structural (eg, the p40 subunit) and functional similarities (eg, IFN-γ production). However, each has distinct characteristics. IL-12 aids in naive CD4+ T-cell differentiation, while IL-23 induces IL-17 production by CD4+ memory T cells. IL-17 triggers a proinflammatory chemokine cascade and produces IL-1, IL-6, nitric oxide synthase 2, and TNF-α.7

Briakinumab (ABT-874)

Briakinumab (formerly known as ABT-874)(Abbott Laboratories) is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23. In a phase 3 trial of 350 participants with moderate to severe psoriasis, week 12 PASI 75 scores were achieved in 80.6% of participants who received briakinumab versus 39.6% of those who received etanercept and 6.9% of those who received placebo.8 In a 52-week phase 3 trial of 317 participants with moderate to severe psoriasis, PASI 75 scores were observed in 81.8% of participants who received briakinumab versus 39.9% of those who received methotrexate.9 In another 52-week phase 3 trial of 1465 participants with moderate to severe psoriasis, clinical benefit was reported at 12 weeks in 75.9% of participants for Dermatology Life Quality Index, and 64.8% and 54.1% for psoriasis- and PsA-related pain scores, respectively.10 However, ABT-874 was withdrawn by the manufacturer as of 2011 due to concerns regarding adverse cardiovascular events.9

BI 655066

BI 655066 (Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH) is a human monoclonal antibody that targets the p19 subunit of IL-23. A phase 1 study of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous (IV) versus subcutaneous (SC) administration of BI 655066 as well as its safety and effectiveness versus placebo recently was completed (NCT01577550), but the results were not available at the time of publication. A phase 2 study comparing 3 dosing regimens of BI 655066 versus ustekinumab is ongoing but not actively recruiting patients at the time of publi-cation (NCT02054481).

Ustekinumab (CNTO 1275)

Ustekinumab (formerly known as CNTO 1275)(Janssen Biotech, Inc) is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23. It was FDA approved for treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in September 200911 and PsA in September 201312 for adult patients 18 years or older. One phase 3 trial (known as ACCEPT) compared the effectiveness of ustekinumab versus etanercept in 903 participants with moderate to severe psoriasis at 67 centers worldwide.13 Participants were randomly assigned to receive SC injections of either 45 mg or 90 mg of ustekinumab (at weeks 0 and 4) or high-dose etanercept (50 mg twice weekly for 12 weeks). At week 12, PASI 75 was noted in 67.5% of participants who received 45 mg of ustekinumab and 73.8% of participants who received 90 mg compared to 56.8% of those who received etanercept (P=.01 and P<.001, respectively). In participants who showed no response to etanercept, PASI 75 was achieved in 48.9% within 12 weeks after crossover to ustekinumab. One or more adverse events (AEs) occurred through week 12 in 66.0% of the 45-mg ustekinumab group, 69.2% of the 90-mg group, and 70.0% of the etanercept group; serious AEs were noted in 1.9%, 1.2%, and 1.2%, respectively.13 A 5-year follow-up study of 3117 participants reported an incidence of AEs with ustekinumab that was comparable to other biologics, with malignancy and mortality rates comparable to age-matched controls.14

In a phase 3, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (know as PSUMMIT I), 615 adults with active PsA who had not previously been treated with TNF inhibitors were randomly assigned to placebo, 45 mg of ustekinumab, or 90 mg of ustekinumab. At week 24, more participants receiving ustekinumab 90 mg achieved 20%, 50%, and 70% improvement in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria (49.5%, 27.9%, and 14.2%, respectively) and PASI 75 (62.4%) versus the placebo group (22.8%, 8.7%, 2.4%, and 11%, respectively).15 In a phase 3, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial (known as PSUMMIT 2), 312 adult participants with active PsA who had formerly been treated with conventional therapies and/or TNF inhibitors were randomized to receive placebo (at weeks 0, 4, and 16 with crossover to 45 mg of ustekinumab at weeks 24, 28, and 40) or ustekinumab (45 mg or 90 mg at weeks 0, 4, and every 12 weeks).16 For participants with less than 5% improvement, there was an early escape clinical trial design with placebo to 45 mg of ustekinumab, 45 mg of ustekinumab to 90 mg, and 90 mg of ustekinumab maintained at the same dose. The ACR20 was 43.8% for the ustekinumab group versus 20.2% for the placebo group (P<.001).16

A phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (known as CADMUS) evaluated the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in the treatment of adolescents (age range, 12–18 years) with moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis.17 The primary outcome of the study was the percentage of participants achieving a physician global assessment (PGA) score of cleared (0) or minimal (1) at week 12. One hundred ten participants started and completed the first period in the study (ie, controlled period [weeks 0–12]) and were randomized into 3 groups: placebo (SC injections at weeks 0 and 4), ustekinumab half-standard dose, and ustekinumab standard dose. At week 12, 101 participants started and completed the second period in the study (weeks 12–60). The placebo group received either ustekinumab half-standard dose or ustekinumab standard dose at weeks 12 and 16, then once every 12 weeks with the last dose at week 40, and the ustekinumab half-standard and standard dose groups received the respective doses every 12 weeks with the last dose at week 40. At week 12, PGA scores of 0 or 1 were reported in 5.4% of the placebo group, 67.6% of the ustekinumab half-standard dose group, and 69.4% of the ustekinumab standard dose group (P<.001), and PASI 75 was achieved in 10.8%, 78.4%, and 80.6%, respectively (P<.001).17

A phase 4 study (known as TRANSIT) assessed the safety and efficacy of ustekinumab in participants with plaque psoriasis who had a suboptimal response to methotrexate.18 Participants in the first treatment group received either 45 mg (weight, ≤100 kg) of ustekinumab at weeks 0, 4, and then every 12 weeks until week 40, or 90 mg (weight, >100 kg) in 2 SC injections after immediate discontinuation of methotrexate. The second treatment group followed the same dosing regimen with gradual withdrawal of methotrexate therapy. Adverse events were reported in 61.1% and 64.5% of participants in groups 1 and 2, respectively. In group 1, PASI 75 was observed in 58.1% of participants (95% confi-dence interval [CI], 51.9%-64.3%) at week 12 and 76.3% (95% CI, 70.8%-81.9%) at week 52. In group 2, PASI 75 was observed in 62.2% of participants (95% CI, 56.0%-68.3%) at week 12 and 76.9% (95% CI, 71.4%-82.5%) at week 52.18

In another study that assessed the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in 24 participants with moderate to severe palmoplantar psoriasis, 37.5% of participants achieved a palmar/plantar PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16.19 A phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the safety and effectiveness of ustekinumab in 615 PsA participants showed ACR20 response in 49.5% of the ustekinumab 90-mg group, 42.4% of the ustekinumab 45-mg group, and 22.8% of the placebo group (P<.001).20

A phase 1 study was performed to assess gene expression in the following: (1) IFN-γ modulation in the IL-12 pathway; (2) IL-23 pathway with ustekinumab (45 mg for those weighing <100 kg and 90 mg for ≤100 kg administered SC on day 1 and at weeks 4 and 16); and (3) IL-17 pathway with etanercept (50 mg administered SC twice weekly for 12 weeks, then once weekly for 4 weeks).21 The change in gene expression from baseline in the IL-12 pathway with ustekinumab achieved statistical significance by week 1 (P=.016) with increasing levels of gene expression through week 16 (P=.000184). The change in gene expression from baseline in the IL-23 pathway with ustekinumab achieved statistical significance by week 2 (P=.010) with increasing levels of gene expression through week 16 (P=.000215). The results were less powerful for etanercept, with a change in gene expression from baseline in the IL-17 pathway increasing through week 4 (P=.053) and decreasing by week 16 (P=.098).21

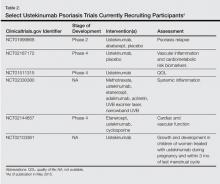

Several clinical trials are underway and are currently recruiting participants (Table 2).

Guselkumab (CNTO 1959)

Guselkumab (formerly known as CNTO 1959)(Janssen Research & Development, LLC) is a human monoclonal antibody targeting the p19 subunit of IL-23. In a double-blind, randomized study of 24 participants receiving 1 dose of CNTO 1959 at 10 mg, 30 mg, 100 mg, or 300 mg versus placebo, a PASI 75 of 50% for the 10-mg subset, 60% for the 30- and 100-mg group, and 100% for the 300-mg group was achieved as opposed to 0% in the placebo group at 12 weeks.22 The rate of AEs was 65% in the CNTO 1959 treatment arm versus 50% in the placebo group at 24 weeks. Furthermore, decreased serum IL-17A titers and gene expression for psoriasis was demonstrated as well as decreased thickness of the epidermis and less dendritic and T-cell expression for the CNTO 1959 study population histologically.22 Results of a phase 2 trial in 293 participants who received CNTO 1959, adalimumab, or placebo indicated PASI 75 at 16 weeks for 81% of the CNTO 1959 50-mg group versus 71% of the adalimumab group, with serious AEs in 3% of participants treated with CNTO 1959 versus 5% treated with adalimumab.23

Tildrakizumab (MK-3222/SCH 900222)

Tildrakizumab (formerly known as MK-3222/SCH 900222)(Merck & Co Inc) is a monoclonal antibody that also targets the p19 subunit of IL-23. Results of a phase 2b trial were promising. This study reported on 355 participants who received placebo versus MK-3222 5 mg, 25 mg, 100 mg, or 200 mg, with PASI 75 scores of 4.4%, 33%, 64%, 66%, and 74%, respectively, noted at 16 weeks.24 A 64-week phase 3 study currently is underway to assess the long-term benefit and safety of MK-3222, but it is not recruiting participants (NCT01722331).

Inhibition of the IL-17 Pathway

The T helper 17 cells (TH17) produce IL-17, a cytokine mediating inflammation that is implicated in psoriasis. Two products target IL-17A, while another targets the IL-17 receptor.25

Secukinumab (AIN457)

Secukinumab (formerly known as AIN457)(Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation) was FDA approved for treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy in January 2015.26 Secukinumab is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-17A. There are many clinical trials underway including a phase 2 extension study (NCT01132612). Many phase 3 studies also are underway evaluating the effectiveness and safety of AIN457 in patients with psoriasis resistant to TNF inhibitors (NCT01961609); its usability and tolerability (NCT01555125), including 2-year extension studies (NCT01640951; NCT01544595); its effectiveness as opposed to ustekinumab (NCT02074982); effectiveness using an autoinjector (NCT01636687); and the PASI 90 in HLA-Cw6–positive and HLA-Cw6–negative patients with moderate to severe psoriasis (known as SUPREME)(NCT02394561).

Other phase 3 trials are being undertaken in patients with moderate to severe palmoplantar psoriasis (NCT01806597; NCT02008890); moderate to severe nail psoriasis (known as TRANSFIGURE)(NCT01807520); moderate to severe scalp psoriasis (NCT02267135); and PsA (NCT01989468; NCT02294227; NCT01892436), including a 5-year study for PsA (known as FUTURE 2)(NCT01752634).

Other studies that are completed with pending results include a phase 1 trial to evaluate its mechanism of action in vivo by studying the spread of AIN457 in tissue as assessed by open flow microperfusion (NCT01539213), a phase 2 trial of the clinical effectiveness of AIN457 at 12 months and biomarker changes (NCT01537432), as well as phase 3 trials of the clinical efficacy of various dosing regimens (known as SCULPTURE)(NCT01406938); safety and effectiveness at 1 year (known as ERASURE)(NCT01365455); and the effectiveness, tolerability, and safety of AIN457 over 2 years in PsA (known as FUTURE 1)(NCT01392326).

In a 56-week phase 2 clinical trial of 100 participants, the PASI scores at 12 weeks and percentage of participants without relapse up to 56 weeks were evaluated.27 There were 4 arms in the study: (1) AIN457 3 mg/kg (day 1) then placebo (days 15 and 29); (2) AIN457 10 mg/kg (day 1) then placebo (days 15 and 29); (3) AIN457 10 mg/kg (days 1, 15, and 29); and (4) placebo (days 1, 15, and 29), with AIN457 and the placebo administered IV. The mean (standard deviation) change from baseline for PASI scores for these respective groups was -12.46 (7.668), -13.35 (6.195), -18.02 (6.792), and -4.18 (4.698), respectively. At week 56, the percentage of participants without a relapse at any point during the study was 12.5%, 22.2%, and 27.8%, respectively.27

In a phase 2 study of 404 participants, PASI 75 scores were assessed at 12 weeks with the SC administration of AIN457 in participants with moderate to severe psoriasis at 3 dosing regimens: (1) a single dose of 150 mg (week 1), (2) monthly doses of 150 mg (weeks 1, 5, and 9), (3) early loading doses of 150 mg (weeks 1, 2, 3, 5, and 9), as compared to placebo. At 12 weeks, PASI 75 scores were 7%, 58%, 72%, and 1%, respectively.28

The phase 3 STATURE trial assessed the safety and effectiveness of SC and IV AIN457 in moderate to severe psoriasis in partial AIN457 nonresponders.29 Nonresponders were participants who demonstrated a PASI score of 50% or more but less than 75%. Participants in this study design who received SC AIN457 demonstrated a PASI 75 of 66.7%, with a 2011 investigator global assessment score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) in 66.7%. In those receiving IV AIN457, the PASI 75 was 90.5%, with a 2011 investigator global assessment score of 0 or 1 in 33.3%.29

In a 52-week phase 3 efficacy trial (known as FIXTURE), 1306 participants received 1 dose of AIN457 300 mg or 150 mg weekly for 5 weeks, then every 4 weeks; 12 weeks of etanercept 50 mg twice weekly, then once weekly; or placebo. The PASI 75 was 77.1% for AIN457 300 mg, 67.0% for AIN457 150 mg, 44.0% for etanercept, and 4.9% for placebo (P<.001).30 In a 52-week efficacy and safety trial (known as ERASURE), 738 participants received 1 dose of AIN457 300 mg or 150 mg weekly for 5 weeks, then every 4 weeks, versus placebo. The PASI 75 was 65.3% for AIN457 300 mg, 51.2% for AIN457 150 mg, and 2.4% for placebo (P<.001). There was a comparable incidence of infection among participants with AIN457 and etanercept, which was greater than placebo.30

Brodalumab (AMG 827)

Brodalumab (formerly known as AMG 827)(Amgen Inc) is a human monoclonal antibody that targets the IL-17A receptor. In a phase 1 randomized trial, 25 participants received either IV brodalumab 700 mg, SC brodalumab 350 mg or 140 mg, or placebo.31 Results demonstrated improvement in PASI score that correlated with increased dosage of brodalumab as well as decreased psoriasis gene expression and decreased thickness of the epidermis in participants receiving the 700-mg IV or 350-mg SC doses. In a phase 2 trial, 198 participants received either brodalumab 280 mg at week 0, then every 4 weeks for 8 weeks, or brodalumab 210 mg, 140 mg, 70 mg, or placebo at week 0, then every 2 weeks for 10 weeks. At week 12, PASI 75 was observed in 82% and 77% of the 210-mg and 140-mg groups, respectively, with no benefit noted in the placebo group (P<.001).31 In a phase 3 trial, 661 participants received brodalumab 210 mg or 140 mg or placebo. At week 12, PASI 75 was observed in 83% of the 210-mg group versus 60% of the 140-mg group; PASI 100 was observed in 42% of the 210-mg group versus 23% of the 140-mg group.32

Ixekizumab (LY2439821)

Ixekizumab (formerly known as LY2439821)(Eli Lilly and Company) is a human monoclonal antibody that targets IL-17A. In a phase 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 142 participants with chronic moderate to severe plaque psoriasis were randomized to receive 10-mg, 25-mg, 75-mg, or 150-mg SC injections of ixekizumab or placebo at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks. At week 12, the percentage of participants with a 75% reduction in PASI score was significantly greater with ixekizumab (150 mg [82.1%], 75 mg [82.8%], and 25 mg [76.7%]), except the 10-mg group, than with placebo (7.7%)(P<.001 for each comparison).33

Inhibition of T-Cell Activation in Antigen-Presenting Cells

Abatacept

Abatacept (Bristol-Myers Squibb) is a fusion protein designed to inhibit T-cell activation by binding receptors for CD80 and CD86 in antigen-presenting cells.34 A phase 1 study of 43 participants demonstrated improved PGA scores of 50% in 46% of psoriasis participants who were treated with abatacept, indicating a dose-responsive association with abatacept in psoriasis patients refractory to other therapies.35 In a 6-month, phase 2, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 170 participants with PsA were randomized to receive placebo or abatacept at doses of 3 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, or 30/10 mg/kg (2 initial doses of 30 mg/kg followed by 10 mg/kg).36 At day 169, ACR20 was observed in 19%, 33%, 48%, and 42% of the placebo and abatacept 3 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg, and 30/10 mg/kg groups, respectively. Compared with placebo, improvements were significantly higher for the abatacept 10-mg/kg (P=.006) and 30/10-mg/kg (P=.022) groups but not for the 3-mg/kg group (P=.121). The authors concluded that abatacept 10 mg/kg could be an appropriate dosing regimen for PsA, as is presently used in the FDA-approved management of rheumatoid arthritis.36 At the time of publication, a phase 3 trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of abatacept SC injection in adults with active PsA was ongoing but was not actively recruiting participants (NCT01860976).

Activation of Regulatory T Cells

Tregalizumab (BT061)

Tregalizumab (formerly known as BT061)(Biotest) is a human monoclonal antibody that activates regulatory T cells. A phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter, multiple-dose, cohort study with escalating doses evaluating the safety and efficacy of BT061 in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis was completed, but the results were not available at the time of publication (NCT01072383).

Inhibition of Toll-like Receptors 7, 8, and 9

IMO-8400

IMO-8400 (Idera Pharmaceuticals) is unique in that it treats psoriasis by targeting toll-like receptors (TLRs) 7, 8, and 9.37 In phase 1 studies, IMO-8400 was well tolerated when administered to a maximum of 0.6 mg/kg.38 An 18-week, phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study evaluating the safety and tolerability of different dose levels—0.075 mg/kg, 0.15 mg/kg, and 0.3 mg/kg—of IMO-8400 versus placebo in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis was completed, but the results were not available at the time of publication (NCT01899729).

Inhibition of Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor

Namilumab (MT203)

Namilumab (formerly known as MT203)(Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited) is a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor inhibitor. At the time of publication, participants were actively being recruited for a phase 2, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding and proof-of-concept study to assess the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of namilumab at 4 different SC doses—300 mg, 160 mg, 100 mg, and 40 mg at baseline with half the dose on days 15, 43, and 71 for each of the 4 treatment arms—versus placebo in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis (NCT02129777).

Conclusion

Novel biologic treatments promise exciting new therapeutic avenues for psoriasis and PsA. Although biologics currently are in use for treatment of psoriasis and PsA in the form of TNF-α inhibitors, other drugs currently in phase 2 through phase 4 clinical trials aim to target other pathways underlying the pathogenesis of psoriasis and PsA, including inhibition of the IL-12/IL-23 pathway; inhibition of the IL-17 pathway; inhibition of T-cell activation in antigen-presenting cells; activation of regulatory T cells; inhibition of TLR-7, TLR-8, and TLR-9; and inhibition of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. These novel therapies offer hope for more targeted treatment strategies for patients with psoriasis and/or PsA.

1. Lee S, Coleman CI, Limone B, et al. Biologic and nonbiologic systemic agents and phototherapy for treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012.

2. Nagler AR, Weinberg JM. Research pipeline III: biologic therapies. In: Weinberg JM, Lebwohl M, eds. Advances in Psoriasis. New York, NY: Springer; 2014:243-251.

3. Reich K, Ortonne JP, Gottlieb AB, et al. Successful treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis with the PEGylated Fab’ certolizumab pegol: results of a phase II randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a re-treatment extension. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:180-190.

4. Gladman D, Fleischmann R, Coteur G, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on multiple facets of psoriatic arthritis as reported by patients: 24-week patient-reported outcome results of a phase III, multicenter study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66:1085-1092.

5. Coherus announces initiation of Phase 3 trial of CHS-0214 (investigational etanercept biosimilar) in chronic plaque psoriasis (RaPsOdy) [press release]. Redwood City, CA: Coherus BioSciences, Inc; July 16, 2014.

6. Coherus announces CHS-0214 (proposed etanercept biosimilar) meets primary endpoint in pivotal pharmacokinetic clinical study [press release]. Redwood City, CA: Coherus BioSciences, Inc; October 28, 2013.

7. Tang C, Chen S, Qian H, et al. Interleukin-23: as a drug target for autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Immunology. 2012;135:112-124.

8. Strober BE, Crowley JJ, Yamauchi PS, et al. Efficacy and safety results from a phase III, randomized controlled trial comparing the safety and efficacy of briakinumab with etanercept and placebo in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:661-668.

9. Reich K, Langley RG, Papp KA, et al. A 52-week trial comparing briakinumab with methotrexate in patients with psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1586-1596.

10. Papp KA, Sundaram M, Bao Y, et al. Effects of briakinumab treatment for moderate to severe psoriasis on health-related quality of life and work productivity and activity impairment: results from a randomized phase III study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:790-798.

11. Stelara (ustekinumab) receives FDA approval to treat active psoriatic arthritis. first and only anti-IL-12/23 treatment approved for adult patients living with psoriatic arthritis [press release]. Horsham, PA: Johnson & Johnson; September 23, 2013.

12. FDA approves new drug to treat psoriasis [press release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; April 17, 2013.

13. Griffiths CE, Strober BE, van de Kerkhof P, et al. Comparison of ustekinumab and etanercept for moderate-to-severe psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:118-128.

14. Papp KA, Griffiths CE, Gordon K, et al. Long-term safety of ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: final results from 5 years of follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:844-854.

15. McInnes IB, Kavanaugh A, Gottlieb AB, et al. Ustekinumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results of the phase 3, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT I study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(suppl):S107-S148.

16. Ritchlin C, Rahman P, Kavanaugh A, et al. Efficacy and safety of the anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite conventional non-biological and biological anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: 6-month and 1-year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised PSUMMIT 2 trial [published online ahead of print Jan 30, 2014]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:990-999.

17. A study of the safety and efficacy of ustekinumab in adolescent patients with psoriasis (CADMUS)(NCT01090427). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01090427?term=NCT01090427&rank=1. Updated January 16, 2015. Accessed April 16, 2015.

18. A safety and efficacy study of ustekinumab in patients with plaque psoriasis who have had an inadequate response to methotrexate (NCT01059773). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01059773?term=NCT01059773&rank=1. Updated November 13, 2014. Accessed April 16, 2015.

19. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in patients with moderate to severe palmar plantar psoriasis (PPP)(NCT01090063). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01090063?term=NCT01090063&rank=1. Updated January 31, 2013. Accessed April 16, 2015.

20. A study of the safety and effectiveness of ustekinumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis (NCT01009086). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01009086?term=NCT01009086&rank=1. Updated February 11, 2015. Accessed April 16, 2015.

21. A study to assess the effect of ustekinumab (Stelara) and etanercept (Enbrel) in participants with moderate to severe psoriasis (MK-0000-206)(NCT01276847). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01276847?term=NCT01276847&rank=1. Updated January 13, 2015. Accessed April 16, 2015.

22. Sofen H, Smith S, Matheson RT, et al. Guselkumab (an IL-23-specific mAb) demonstrates clinical and molecular response in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1032-1040.

23. Callis Duffin K, Wasfi Y, Shen YK, et al. A phase 2, multicenter, randomized, placebo- and active-comparator-controlled, dose-ranging trial to evaluate Guselkumab for the treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque-type psoriasis (X-PLORE). Poster presented at: 72nd Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; March 21-25, 2014; Denver, CO.

24. Papp K. Monoclonal antibody MK-3222 and chronic plaque psoriasis: phase 2b. Paper presented at: 71st Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; March 1-5, 2013; Miami, FL.

25. Huynh D, Kavanaugh A. Psoriatic arthritis: current therapy and future approaches. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:20-28.

26. FDA approves new psoriasis drug Cosentyx [press release]. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; January 21, 2015.

27. Multiple-loading dose regimen study in patients with chronic plaque-type psoriasis (NCT00805480). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00805480?term

=NCT00805480&rank=1. Updated January 28, 2015. Accessed April 16, 2015.

28. AIN457 regimen finding study in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis (NCT00941031). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00941031?term=NCT00941031&rank=1. Updated March 23, 2015. Accessed April 16, 2015.

29. Efficacy and safety of intravenous and subcutaneous secukinumab in moderate to severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis (STATURE)(NCT014712944). https://clinical trials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01412944?term=efficacy+and+safety+of+intravenous+and+subcutaneoussecukinumab&rank=1. Updated March 17, 2015. Accessed April 16, 2015.

30. Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis–results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326-338.

31. Coimbra S, Figueiredo A, Santos-Silva A. Brodalumab: an evidence-based review of its potential in the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Core Evid. 2014;9:89-97.

32. Leavitt M. New biologic clears psoriasis in 42 percent of patients. National Psoriasis Foundation Web site. https://www.psoriasis.org/advance/new-biologic-clears-psoriasis-in-42-percent-of-patients. Accessed April 10, 2015.

33. Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, et al. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1190-1199.

34. Herrero-Beaumont G, Martínez Calatrava MJ, Castañeda S. Abatacept mechanism of action: concordance with its clinical profile. Rheumatol Clin. 2012;8:78-83.

35. Abrams JR, Lebwohl MG, Guzzo CA, et al. CTLA4Ig-mediated blockade of T-cell costimulation in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1243-1252.

36. Mease P, Genovese MC, Gladstein G, et al. Abatacept in the treatment of patients with psoriatic arthritis: results of a six-month, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:939-948.

37. Suárez-Fariñas M, Arbeit R, Jiang W, et al. Suppression of molecular inflammatory pathways by Toll-like receptor 7, 8, and 9 antagonists in a model of IL-23-induced skin inflammation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e84634.

38. A 12-week dose-ranging trial in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (8400-201)(NCT01899729). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01899729. Updated October 16, 2014. Accessed April 27, 2015.

Biologic agents that currently are in use for the management of moderate to severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA) include the anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α monoclonal antibodies adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab1; however, additional TNF-α inhibitors as well as drugs targeting other pathways presently are in the pipeline. Novel biologic treatments currently in phase 2 through phase 4 clinical trials, including those that have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), are discussed in this article, and a summary is provided in Table 1.

Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitors

Certolizumab Pegol

Certolizumab pegol (CZP; UCB, Inc), a pegylated TNF-α inhibitor, is unique in that it does not possess a fragment crystallizable (Fc) region and consequently does not trigger complement activation. The drug is presently FDA approved for active PsA, rheumatoid arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. One phase 2 study reported psoriasis area severity index (PASI) scores of 75 in 83% (48/58) of participants who received CZP 400 mg at week 0 and every other week until week 10 (P<.001 vs placebo).3 In a 24-week phase 3 study (known as RAPID-PsA), 409 participants were randomized into 3 study arms: (1) CZP 400 mg every 4 weeks; (2) CZP 200 mg every 2 weeks; (3) placebo every 2 weeks.4 Of note, 20% of participants had previously received a TNF inhibitor. The study demonstrated improvements in participant-reported outcomes with use of CZP regardless of prior TNF inhibitor use.4

CHS-0214

CHS-0214 (Coherus BioSciences, Inc) is a TNF-α inhibitor and etanercept biosimilar that has entered into a 48-week multicenter phase 3 trial (known as RaPsOdy) for patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. The purpose of the study is to compare PASI scores for CHS-0214 and etanercept to evaluate immunogenicity, safety, and effectiveness over a 12-week period.5 Comparable pharmacokinetics were established in an earlier study.6

Inhibition of the IL-12/IL-23 Pathway

IL-12 and IL-23 are cytokines with prostaglan-din E2–mediated production by dendritic cells that share structural (eg, the p40 subunit) and functional similarities (eg, IFN-γ production). However, each has distinct characteristics. IL-12 aids in naive CD4+ T-cell differentiation, while IL-23 induces IL-17 production by CD4+ memory T cells. IL-17 triggers a proinflammatory chemokine cascade and produces IL-1, IL-6, nitric oxide synthase 2, and TNF-α.7

Briakinumab (ABT-874)

Briakinumab (formerly known as ABT-874)(Abbott Laboratories) is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23. In a phase 3 trial of 350 participants with moderate to severe psoriasis, week 12 PASI 75 scores were achieved in 80.6% of participants who received briakinumab versus 39.6% of those who received etanercept and 6.9% of those who received placebo.8 In a 52-week phase 3 trial of 317 participants with moderate to severe psoriasis, PASI 75 scores were observed in 81.8% of participants who received briakinumab versus 39.9% of those who received methotrexate.9 In another 52-week phase 3 trial of 1465 participants with moderate to severe psoriasis, clinical benefit was reported at 12 weeks in 75.9% of participants for Dermatology Life Quality Index, and 64.8% and 54.1% for psoriasis- and PsA-related pain scores, respectively.10 However, ABT-874 was withdrawn by the manufacturer as of 2011 due to concerns regarding adverse cardiovascular events.9

BI 655066

BI 655066 (Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH) is a human monoclonal antibody that targets the p19 subunit of IL-23. A phase 1 study of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intravenous (IV) versus subcutaneous (SC) administration of BI 655066 as well as its safety and effectiveness versus placebo recently was completed (NCT01577550), but the results were not available at the time of publication. A phase 2 study comparing 3 dosing regimens of BI 655066 versus ustekinumab is ongoing but not actively recruiting patients at the time of publi-cation (NCT02054481).

Ustekinumab (CNTO 1275)

Ustekinumab (formerly known as CNTO 1275)(Janssen Biotech, Inc) is a human monoclonal antibody that inhibits the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23. It was FDA approved for treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in September 200911 and PsA in September 201312 for adult patients 18 years or older. One phase 3 trial (known as ACCEPT) compared the effectiveness of ustekinumab versus etanercept in 903 participants with moderate to severe psoriasis at 67 centers worldwide.13 Participants were randomly assigned to receive SC injections of either 45 mg or 90 mg of ustekinumab (at weeks 0 and 4) or high-dose etanercept (50 mg twice weekly for 12 weeks). At week 12, PASI 75 was noted in 67.5% of participants who received 45 mg of ustekinumab and 73.8% of participants who received 90 mg compared to 56.8% of those who received etanercept (P=.01 and P<.001, respectively). In participants who showed no response to etanercept, PASI 75 was achieved in 48.9% within 12 weeks after crossover to ustekinumab. One or more adverse events (AEs) occurred through week 12 in 66.0% of the 45-mg ustekinumab group, 69.2% of the 90-mg group, and 70.0% of the etanercept group; serious AEs were noted in 1.9%, 1.2%, and 1.2%, respectively.13 A 5-year follow-up study of 3117 participants reported an incidence of AEs with ustekinumab that was comparable to other biologics, with malignancy and mortality rates comparable to age-matched controls.14

In a phase 3, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (know as PSUMMIT I), 615 adults with active PsA who had not previously been treated with TNF inhibitors were randomly assigned to placebo, 45 mg of ustekinumab, or 90 mg of ustekinumab. At week 24, more participants receiving ustekinumab 90 mg achieved 20%, 50%, and 70% improvement in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria (49.5%, 27.9%, and 14.2%, respectively) and PASI 75 (62.4%) versus the placebo group (22.8%, 8.7%, 2.4%, and 11%, respectively).15 In a phase 3, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial (known as PSUMMIT 2), 312 adult participants with active PsA who had formerly been treated with conventional therapies and/or TNF inhibitors were randomized to receive placebo (at weeks 0, 4, and 16 with crossover to 45 mg of ustekinumab at weeks 24, 28, and 40) or ustekinumab (45 mg or 90 mg at weeks 0, 4, and every 12 weeks).16 For participants with less than 5% improvement, there was an early escape clinical trial design with placebo to 45 mg of ustekinumab, 45 mg of ustekinumab to 90 mg, and 90 mg of ustekinumab maintained at the same dose. The ACR20 was 43.8% for the ustekinumab group versus 20.2% for the placebo group (P<.001).16

A phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (known as CADMUS) evaluated the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in the treatment of adolescents (age range, 12–18 years) with moderate to severe plaque-type psoriasis.17 The primary outcome of the study was the percentage of participants achieving a physician global assessment (PGA) score of cleared (0) or minimal (1) at week 12. One hundred ten participants started and completed the first period in the study (ie, controlled period [weeks 0–12]) and were randomized into 3 groups: placebo (SC injections at weeks 0 and 4), ustekinumab half-standard dose, and ustekinumab standard dose. At week 12, 101 participants started and completed the second period in the study (weeks 12–60). The placebo group received either ustekinumab half-standard dose or ustekinumab standard dose at weeks 12 and 16, then once every 12 weeks with the last dose at week 40, and the ustekinumab half-standard and standard dose groups received the respective doses every 12 weeks with the last dose at week 40. At week 12, PGA scores of 0 or 1 were reported in 5.4% of the placebo group, 67.6% of the ustekinumab half-standard dose group, and 69.4% of the ustekinumab standard dose group (P<.001), and PASI 75 was achieved in 10.8%, 78.4%, and 80.6%, respectively (P<.001).17

A phase 4 study (known as TRANSIT) assessed the safety and efficacy of ustekinumab in participants with plaque psoriasis who had a suboptimal response to methotrexate.18 Participants in the first treatment group received either 45 mg (weight, ≤100 kg) of ustekinumab at weeks 0, 4, and then every 12 weeks until week 40, or 90 mg (weight, >100 kg) in 2 SC injections after immediate discontinuation of methotrexate. The second treatment group followed the same dosing regimen with gradual withdrawal of methotrexate therapy. Adverse events were reported in 61.1% and 64.5% of participants in groups 1 and 2, respectively. In group 1, PASI 75 was observed in 58.1% of participants (95% confi-dence interval [CI], 51.9%-64.3%) at week 12 and 76.3% (95% CI, 70.8%-81.9%) at week 52. In group 2, PASI 75 was observed in 62.2% of participants (95% CI, 56.0%-68.3%) at week 12 and 76.9% (95% CI, 71.4%-82.5%) at week 52.18

In another study that assessed the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab in 24 participants with moderate to severe palmoplantar psoriasis, 37.5% of participants achieved a palmar/plantar PGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16.19 A phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the safety and effectiveness of ustekinumab in 615 PsA participants showed ACR20 response in 49.5% of the ustekinumab 90-mg group, 42.4% of the ustekinumab 45-mg group, and 22.8% of the placebo group (P<.001).20

A phase 1 study was performed to assess gene expression in the following: (1) IFN-γ modulation in the IL-12 pathway; (2) IL-23 pathway with ustekinumab (45 mg for those weighing <100 kg and 90 mg for ≤100 kg administered SC on day 1 and at weeks 4 and 16); and (3) IL-17 pathway with etanercept (50 mg administered SC twice weekly for 12 weeks, then once weekly for 4 weeks).21 The change in gene expression from baseline in the IL-12 pathway with ustekinumab achieved statistical significance by week 1 (P=.016) with increasing levels of gene expression through week 16 (P=.000184). The change in gene expression from baseline in the IL-23 pathway with ustekinumab achieved statistical significance by week 2 (P=.010) with increasing levels of gene expression through week 16 (P=.000215). The results were less powerful for etanercept, with a change in gene expression from baseline in the IL-17 pathway increasing through week 4 (P=.053) and decreasing by week 16 (P=.098).21

Several clinical trials are underway and are currently recruiting participants (Table 2).

Guselkumab (CNTO 1959)

Guselkumab (formerly known as CNTO 1959)(Janssen Research & Development, LLC) is a human monoclonal antibody targeting the p19 subunit of IL-23. In a double-blind, randomized study of 24 participants receiving 1 dose of CNTO 1959 at 10 mg, 30 mg, 100 mg, or 300 mg versus placebo, a PASI 75 of 50% for the 10-mg subset, 60% for the 30- and 100-mg group, and 100% for the 300-mg group was achieved as opposed to 0% in the placebo group at 12 weeks.22 The rate of AEs was 65% in the CNTO 1959 treatment arm versus 50% in the placebo group at 24 weeks. Furthermore, decreased serum IL-17A titers and gene expression for psoriasis was demonstrated as well as decreased thickness of the epidermis and less dendritic and T-cell expression for the CNTO 1959 study population histologically.22 Results of a phase 2 trial in 293 participants who received CNTO 1959, adalimumab, or placebo indicated PASI 75 at 16 weeks for 81% of the CNTO 1959 50-mg group versus 71% of the adalimumab group, with serious AEs in 3% of participants treated with CNTO 1959 versus 5% treated with adalimumab.23

Tildrakizumab (MK-3222/SCH 900222)

Tildrakizumab (formerly known as MK-3222/SCH 900222)(Merck & Co Inc) is a monoclonal antibody that also targets the p19 subunit of IL-23. Results of a phase 2b trial were promising. This study reported on 355 participants who received placebo versus MK-3222 5 mg, 25 mg, 100 mg, or 200 mg, with PASI 75 scores of 4.4%, 33%, 64%, 66%, and 74%, respectively, noted at 16 weeks.24 A 64-week phase 3 study currently is underway to assess the long-term benefit and safety of MK-3222, but it is not recruiting participants (NCT01722331).

Inhibition of the IL-17 Pathway

The T helper 17 cells (TH17) produce IL-17, a cytokine mediating inflammation that is implicated in psoriasis. Two products target IL-17A, while another targets the IL-17 receptor.25

Secukinumab (AIN457)