User login

Current Perspectives on Transport Medicine in Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellowships

Transport medicine (TM) involves the provision of care to patients who require transfer to a healthcare facility that can deliver definitive treatment.1 Pediatric interfacility transport occurs in approximately 10% of nonneonatal, nonpregnancy pediatric hospitalizations in the United States.2 Studies document a decline in resident participation in pediatric transports and variability in curricular content.3,4

The Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) Core Competencies include “Transport of the Critically Ill Child.”7 Additionally, the Curriculum Committee of the PHM Fellowship Directors Council proposed a curricular framework that includes a required clinical experience in “Care and Stabilization of the Critically Ill Child,”8 which can occur in a variety of practice settings, including TM. TM is also listed as a potential elective rotation.

In 2014, 60% of PHM fellowships included a required or optional TM rotation.9 A recent study of pediatric emergency, critical care, and neonatal medicine fellowships revealed a paucity of formal or published TM curricula in these programs.10 Furthermore, no standard or published TM curricula have been established for PHM fellowships. The primary objective of our study is to determine attitudes regarding TM training among PHM fellows, recent PHM fellowship graduates, and PHM fellowship program directors (PDs). The secondary objective is to identify how the perspectives of these fellowship stakeholders could influence the design of a TM curriculum.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study focused on 3 stakeholder groups related to PHM fellowships. The subjects included in the study were physicians enrolled in a PHM fellowship (fellow) during the 2015-2016 academic year, graduates of fellowship (graduate) between 2010 and 2015, and fellowship program directors (PD). Unique web-based, anonymous surveys for each group were developed, reviewed by content and methodology experts, and piloted with local pediatric hospitalists. Surveys consisted of unfolding multiple-choice questions and ranking items along Likert scales and the Dreyfus model.

Questions were designed to elicit demographic data, perspectives, and experience related to TM education in PHM fellowships across all respondent groups. Depending on the context, identical or similar questions were asked among the groups. For example, all groups were asked to prioritize learning objectives for a TM rotation. Graduates and PDs reported the most effective teaching methods for use during a TM rotation. Fellows rated their own interest in a TM elective, and PDs were asked to rate the level of interest among their fellows.

Participant contact information was obtained from a website (phmfellows.org) and databases of fellows and graduates, which are maintained by the PHM Fellowship Directors Council (personal communication, Jayne Truckenbrod, DO; February 2, 2017). Between February and April 2016, the participants were individually emailed a link to their respective surveys, and 3 reminder e-mails were sent to nonresponders. The survey was administered through SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com).

SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York) was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive data were presented using mean and standard deviation. Comparisons among fellows, graduates, and PDs were conducted using one-way analyses of variance or Mann-Whitney U test. Frequency of application and self-evaluation of core competency skills before and after the rotation were evaluated using paired sample t-tests. The study protocol was deemed exempt from review by our local Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Forty of 70 (57%) fellows, 32 of 87 graduates (37%), and 14 of 32 PDs (44%) responded to the survey. The majority of the participants described their respective programs as 2 years in duration (59% for fellows, 56% for graduates, and 85% for PDs). Most programs (85%) were based at children’s hospitals. Most graduates (84%) practiced in a children’s hospital, and 12% of them practiced in a community site or a combination of sites.

Both fellows and graduates reported limited involvement in several aspects of TM prior to fellowship. Fellows’ interest in completing a TM rotation during fellowship is greater than the interest as perceived by PDs (3.03+1.00 vs. 2.38+1.19, P = .061). Prior TM exposure in residency or perceived proficiency in TM was not associated with lack of interest. Twenty-five percent of graduates completed a TM rotation during PHM fellowship. Many graduates agreed (41%) or strongly agreed (16%) with the statement “I recommend participating in a TM rotation during PHM fellowship.” Graduates who had completed a TM rotation were more likely to agree with this statement (P = .001).

There were similarities between reservations about participating in a TM rotation among fellows and barriers identified by graduates and PDs (Table). However, no graduates cited lack of relevance to a career in PHM as a barrier to participation in a TM rotation. Fellows, graduates, and PDs reported concordant responses regarding the prioritization of learning objectives for a TM rotation (Table). Both graduates and PDs ranked active learning strategies, such as direct patient care and simulation, as the most effective methods for teaching TM.

Discordance was noted between how frequently fellows participated in aspects of TM during fellowship and graduates’ current practice of PHM (Figure). With regard to select TM-related PHM core competencies, such as respiratory failure, shock, and leading a healthcare team, most (63%–90%, depending on the competency) fellows perceived themselves as “competent” prior to the start of the fellowship. Nevertheless, more than 70% of fellows remained very or extremely interested in gaining additional experience in each competency during fellowship.

DISCUSSION

Survey respondents demonstrate variable levels of interest and engagement in TM training; in particular, fellows and graduates often reported greater interest and value in a TM rotation than PDs. Similar to fellows in related fields,10 PHM fellows and graduates selected clinical topics as the most essential elements of TM training. In accordance with the literature, our findings suggest that direct patient care, one-on-one instruction, and simulation would be appropriate and popular methods for delivering this type of educational content.10,11

Curriculum design for a TM rotation should reinforce clinical PHM competencies related to TM while focusing on topics that are specific to the transport environment, such as methods of interfacility transport, handoffs, transitions of care, and team leadership.2,7,12 Trainee comfort level with different forms of transport (eg, fear of flying, motion sickness) and local and state policies regarding interfacility transfer should also be considered. In addition, fellows could engage in clinical research and quality improvement projects related to TM given the overall paucity of literature in the field.13

Several reasons can explain why fellows and graduates place a greater value on a TM rotation than PDs. Fellows and graduates may perceive inherent value in gaining particular knowledge and skills, such as greater understanding of the logistics and personnel involved in transferring patients and experience working with a healthcare team in a unique and dynamic setting.3,10,14

PDs may not be aware of the extent of participation in elements of transport among graduates. A recent workforce survey of pediatric interfacility transport systems indicated that although medical directors are from the fields of emergency, critical care, and neonatal medicine, 20% of medical control physicians are pediatric hospitalists.4 Given that the majority of PHM fellowships are based at children’s hospitals and transport teams are often associated with intensive care or emergency medicine units, PDs may have limited exposure to transport systems that incorporate hospitalists.

Pediatric hospitalists at all practice sites must have clinical and systems skills related to TM. However, the scope of practice for those working at community sites may be more likely to include distinct elements of TM.6 Currently, most fellowship graduates work at free-standing children’s or university-affiliated hospitals and have pursued careers in academic medicine.15 As the field evolves, the number of fellowship-trained pediatric hospitalists working at community sites may increase, making the acquisition of skills relevant to TM during fellowship training more crucial.

This study has several limitations. We attempted to identify all recent PHM fellowship graduates, but sampling bias may exist. Response bias may have been introduced by the self-reporting of skill and proficiency as well as by the small sample size and response rate for some stakeholder groups. The latter may be exacerbated by the fact that we do not have data on the degree or distribution of program representation among the fellow and graduate groups, given the lack of identifying information collected. Finally, we did not collect specific information about existing TM curricula in PHM fellowships.

We report a variable level of interest and engagement in TM among fellowship stakeholders, even though “Transport of the Critically Ill Child” is a PHM Core Competency. Fellows are interested in TM but unsure of its relevance to a PHM career. Graduates support the acquisition of transport skills during fellowship training.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Tony Woodward, MD for reviewing the survey tools; Sheree Schrager, PhD and Margaret Trost, MD for their valuable insights into the results; and Grant Christman, MD for reviewing the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was secured for this study.

1. Insoft RM, Schwartz HP, Romito J. Guidelines for Air and Ground Transport of Neonatal and Pediatric Patients., 4th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2016.

2. Rosenthal JL, Romano PS, Kokroko J, Gu W, Okumura MJ. Profiling interfacility transfers for hospitalized pediatric patients. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(6):335-343. PubMed

3. Kline-Krammes S, Wheeler DS, Schwartz HP, Forbes M, Bigham MT. Missed opportunities during pediatric residency training. Report of a 10-year follow-up survey in critical care transport medicine. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(1):1-5. PubMed

4. Tanem J, Triscari D, Chan M, Meyer MT. Workforce survey of pediatric interfacility transport systems in the United States. Pediatr Emer Care. 2016;32(6):364-370. PubMed

5. Freed GL, Dunham KM. Pediatric hospitalists: training, current practice, and career goals. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):179-186. PubMed

6. Roberts KB. Pediatric hospitalists in community hospitals: hospital-based generalists with expanded roles. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(5):290-292. PubMed

7. Stucky ER, Maniscalco J, Ottolini MC, et al. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies Supplement: a Framework for Curriculum Development by the Society of Hospital Medicine with acknowledgement to pediatric hospitalists from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Academic Pediatric Association. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(suppl 2):i-xv, 1-114. PubMed

8. Jerardi KE, Fisher E, Rassbach C, et al. Development of a Curricular Framework for Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellowships. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):1-8. PubMed

9. Shah NH, Rhim HJH, Maniscalco J, Wilson K, Rassbach C. The current state of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships: A survey of program directors. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):324-328. PubMed

10. Mickells GE, Goodman DM, Rozenfeld RA. Education of pediatric subspecialty fellows in transport medicine: a national survey. BMC Pediatrics. 2017;17(1):13. PubMed

11. Cross B, Wilson D. High-fidelity simulation for transport team training and competency evaluation. Newborn Inf Nurs Rev. 2009;9(4):200-206.

12. Weingart C, Herstich T, Baker P, et al. Making good better: implementing a standardized handoff in pediatric transport. Air Med J. 2013;32(1):40-46. PubMed

13. Kandil SB, Sanford HA, Northrup V, Bigham MT, Giuliano Jr. JS. Transport disposition using transport risk assessment in pediatrics (TRAP) score. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012;16(3):366-373. PubMed

14. Giardino AP, Tran XG, King J, Giardino ER, Woodward GA, Durbin DR. A longitudinal view of resident education in pediatric emergency interhospital transport. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(9):653-658. PubMed

15. Oshimurua JM, Bauer BD, Shah N, Nguyen N, Maniscalco J. Current roles and perceived needs of pediatric hospital medicine fellowship graduates. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(10):633-637 PubMed

Transport medicine (TM) involves the provision of care to patients who require transfer to a healthcare facility that can deliver definitive treatment.1 Pediatric interfacility transport occurs in approximately 10% of nonneonatal, nonpregnancy pediatric hospitalizations in the United States.2 Studies document a decline in resident participation in pediatric transports and variability in curricular content.3,4

The Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) Core Competencies include “Transport of the Critically Ill Child.”7 Additionally, the Curriculum Committee of the PHM Fellowship Directors Council proposed a curricular framework that includes a required clinical experience in “Care and Stabilization of the Critically Ill Child,”8 which can occur in a variety of practice settings, including TM. TM is also listed as a potential elective rotation.

In 2014, 60% of PHM fellowships included a required or optional TM rotation.9 A recent study of pediatric emergency, critical care, and neonatal medicine fellowships revealed a paucity of formal or published TM curricula in these programs.10 Furthermore, no standard or published TM curricula have been established for PHM fellowships. The primary objective of our study is to determine attitudes regarding TM training among PHM fellows, recent PHM fellowship graduates, and PHM fellowship program directors (PDs). The secondary objective is to identify how the perspectives of these fellowship stakeholders could influence the design of a TM curriculum.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study focused on 3 stakeholder groups related to PHM fellowships. The subjects included in the study were physicians enrolled in a PHM fellowship (fellow) during the 2015-2016 academic year, graduates of fellowship (graduate) between 2010 and 2015, and fellowship program directors (PD). Unique web-based, anonymous surveys for each group were developed, reviewed by content and methodology experts, and piloted with local pediatric hospitalists. Surveys consisted of unfolding multiple-choice questions and ranking items along Likert scales and the Dreyfus model.

Questions were designed to elicit demographic data, perspectives, and experience related to TM education in PHM fellowships across all respondent groups. Depending on the context, identical or similar questions were asked among the groups. For example, all groups were asked to prioritize learning objectives for a TM rotation. Graduates and PDs reported the most effective teaching methods for use during a TM rotation. Fellows rated their own interest in a TM elective, and PDs were asked to rate the level of interest among their fellows.

Participant contact information was obtained from a website (phmfellows.org) and databases of fellows and graduates, which are maintained by the PHM Fellowship Directors Council (personal communication, Jayne Truckenbrod, DO; February 2, 2017). Between February and April 2016, the participants were individually emailed a link to their respective surveys, and 3 reminder e-mails were sent to nonresponders. The survey was administered through SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com).

SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York) was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive data were presented using mean and standard deviation. Comparisons among fellows, graduates, and PDs were conducted using one-way analyses of variance or Mann-Whitney U test. Frequency of application and self-evaluation of core competency skills before and after the rotation were evaluated using paired sample t-tests. The study protocol was deemed exempt from review by our local Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Forty of 70 (57%) fellows, 32 of 87 graduates (37%), and 14 of 32 PDs (44%) responded to the survey. The majority of the participants described their respective programs as 2 years in duration (59% for fellows, 56% for graduates, and 85% for PDs). Most programs (85%) were based at children’s hospitals. Most graduates (84%) practiced in a children’s hospital, and 12% of them practiced in a community site or a combination of sites.

Both fellows and graduates reported limited involvement in several aspects of TM prior to fellowship. Fellows’ interest in completing a TM rotation during fellowship is greater than the interest as perceived by PDs (3.03+1.00 vs. 2.38+1.19, P = .061). Prior TM exposure in residency or perceived proficiency in TM was not associated with lack of interest. Twenty-five percent of graduates completed a TM rotation during PHM fellowship. Many graduates agreed (41%) or strongly agreed (16%) with the statement “I recommend participating in a TM rotation during PHM fellowship.” Graduates who had completed a TM rotation were more likely to agree with this statement (P = .001).

There were similarities between reservations about participating in a TM rotation among fellows and barriers identified by graduates and PDs (Table). However, no graduates cited lack of relevance to a career in PHM as a barrier to participation in a TM rotation. Fellows, graduates, and PDs reported concordant responses regarding the prioritization of learning objectives for a TM rotation (Table). Both graduates and PDs ranked active learning strategies, such as direct patient care and simulation, as the most effective methods for teaching TM.

Discordance was noted between how frequently fellows participated in aspects of TM during fellowship and graduates’ current practice of PHM (Figure). With regard to select TM-related PHM core competencies, such as respiratory failure, shock, and leading a healthcare team, most (63%–90%, depending on the competency) fellows perceived themselves as “competent” prior to the start of the fellowship. Nevertheless, more than 70% of fellows remained very or extremely interested in gaining additional experience in each competency during fellowship.

DISCUSSION

Survey respondents demonstrate variable levels of interest and engagement in TM training; in particular, fellows and graduates often reported greater interest and value in a TM rotation than PDs. Similar to fellows in related fields,10 PHM fellows and graduates selected clinical topics as the most essential elements of TM training. In accordance with the literature, our findings suggest that direct patient care, one-on-one instruction, and simulation would be appropriate and popular methods for delivering this type of educational content.10,11

Curriculum design for a TM rotation should reinforce clinical PHM competencies related to TM while focusing on topics that are specific to the transport environment, such as methods of interfacility transport, handoffs, transitions of care, and team leadership.2,7,12 Trainee comfort level with different forms of transport (eg, fear of flying, motion sickness) and local and state policies regarding interfacility transfer should also be considered. In addition, fellows could engage in clinical research and quality improvement projects related to TM given the overall paucity of literature in the field.13

Several reasons can explain why fellows and graduates place a greater value on a TM rotation than PDs. Fellows and graduates may perceive inherent value in gaining particular knowledge and skills, such as greater understanding of the logistics and personnel involved in transferring patients and experience working with a healthcare team in a unique and dynamic setting.3,10,14

PDs may not be aware of the extent of participation in elements of transport among graduates. A recent workforce survey of pediatric interfacility transport systems indicated that although medical directors are from the fields of emergency, critical care, and neonatal medicine, 20% of medical control physicians are pediatric hospitalists.4 Given that the majority of PHM fellowships are based at children’s hospitals and transport teams are often associated with intensive care or emergency medicine units, PDs may have limited exposure to transport systems that incorporate hospitalists.

Pediatric hospitalists at all practice sites must have clinical and systems skills related to TM. However, the scope of practice for those working at community sites may be more likely to include distinct elements of TM.6 Currently, most fellowship graduates work at free-standing children’s or university-affiliated hospitals and have pursued careers in academic medicine.15 As the field evolves, the number of fellowship-trained pediatric hospitalists working at community sites may increase, making the acquisition of skills relevant to TM during fellowship training more crucial.

This study has several limitations. We attempted to identify all recent PHM fellowship graduates, but sampling bias may exist. Response bias may have been introduced by the self-reporting of skill and proficiency as well as by the small sample size and response rate for some stakeholder groups. The latter may be exacerbated by the fact that we do not have data on the degree or distribution of program representation among the fellow and graduate groups, given the lack of identifying information collected. Finally, we did not collect specific information about existing TM curricula in PHM fellowships.

We report a variable level of interest and engagement in TM among fellowship stakeholders, even though “Transport of the Critically Ill Child” is a PHM Core Competency. Fellows are interested in TM but unsure of its relevance to a PHM career. Graduates support the acquisition of transport skills during fellowship training.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Tony Woodward, MD for reviewing the survey tools; Sheree Schrager, PhD and Margaret Trost, MD for their valuable insights into the results; and Grant Christman, MD for reviewing the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was secured for this study.

Transport medicine (TM) involves the provision of care to patients who require transfer to a healthcare facility that can deliver definitive treatment.1 Pediatric interfacility transport occurs in approximately 10% of nonneonatal, nonpregnancy pediatric hospitalizations in the United States.2 Studies document a decline in resident participation in pediatric transports and variability in curricular content.3,4

The Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) Core Competencies include “Transport of the Critically Ill Child.”7 Additionally, the Curriculum Committee of the PHM Fellowship Directors Council proposed a curricular framework that includes a required clinical experience in “Care and Stabilization of the Critically Ill Child,”8 which can occur in a variety of practice settings, including TM. TM is also listed as a potential elective rotation.

In 2014, 60% of PHM fellowships included a required or optional TM rotation.9 A recent study of pediatric emergency, critical care, and neonatal medicine fellowships revealed a paucity of formal or published TM curricula in these programs.10 Furthermore, no standard or published TM curricula have been established for PHM fellowships. The primary objective of our study is to determine attitudes regarding TM training among PHM fellows, recent PHM fellowship graduates, and PHM fellowship program directors (PDs). The secondary objective is to identify how the perspectives of these fellowship stakeholders could influence the design of a TM curriculum.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study focused on 3 stakeholder groups related to PHM fellowships. The subjects included in the study were physicians enrolled in a PHM fellowship (fellow) during the 2015-2016 academic year, graduates of fellowship (graduate) between 2010 and 2015, and fellowship program directors (PD). Unique web-based, anonymous surveys for each group were developed, reviewed by content and methodology experts, and piloted with local pediatric hospitalists. Surveys consisted of unfolding multiple-choice questions and ranking items along Likert scales and the Dreyfus model.

Questions were designed to elicit demographic data, perspectives, and experience related to TM education in PHM fellowships across all respondent groups. Depending on the context, identical or similar questions were asked among the groups. For example, all groups were asked to prioritize learning objectives for a TM rotation. Graduates and PDs reported the most effective teaching methods for use during a TM rotation. Fellows rated their own interest in a TM elective, and PDs were asked to rate the level of interest among their fellows.

Participant contact information was obtained from a website (phmfellows.org) and databases of fellows and graduates, which are maintained by the PHM Fellowship Directors Council (personal communication, Jayne Truckenbrod, DO; February 2, 2017). Between February and April 2016, the participants were individually emailed a link to their respective surveys, and 3 reminder e-mails were sent to nonresponders. The survey was administered through SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com).

SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York) was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive data were presented using mean and standard deviation. Comparisons among fellows, graduates, and PDs were conducted using one-way analyses of variance or Mann-Whitney U test. Frequency of application and self-evaluation of core competency skills before and after the rotation were evaluated using paired sample t-tests. The study protocol was deemed exempt from review by our local Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Forty of 70 (57%) fellows, 32 of 87 graduates (37%), and 14 of 32 PDs (44%) responded to the survey. The majority of the participants described their respective programs as 2 years in duration (59% for fellows, 56% for graduates, and 85% for PDs). Most programs (85%) were based at children’s hospitals. Most graduates (84%) practiced in a children’s hospital, and 12% of them practiced in a community site or a combination of sites.

Both fellows and graduates reported limited involvement in several aspects of TM prior to fellowship. Fellows’ interest in completing a TM rotation during fellowship is greater than the interest as perceived by PDs (3.03+1.00 vs. 2.38+1.19, P = .061). Prior TM exposure in residency or perceived proficiency in TM was not associated with lack of interest. Twenty-five percent of graduates completed a TM rotation during PHM fellowship. Many graduates agreed (41%) or strongly agreed (16%) with the statement “I recommend participating in a TM rotation during PHM fellowship.” Graduates who had completed a TM rotation were more likely to agree with this statement (P = .001).

There were similarities between reservations about participating in a TM rotation among fellows and barriers identified by graduates and PDs (Table). However, no graduates cited lack of relevance to a career in PHM as a barrier to participation in a TM rotation. Fellows, graduates, and PDs reported concordant responses regarding the prioritization of learning objectives for a TM rotation (Table). Both graduates and PDs ranked active learning strategies, such as direct patient care and simulation, as the most effective methods for teaching TM.

Discordance was noted between how frequently fellows participated in aspects of TM during fellowship and graduates’ current practice of PHM (Figure). With regard to select TM-related PHM core competencies, such as respiratory failure, shock, and leading a healthcare team, most (63%–90%, depending on the competency) fellows perceived themselves as “competent” prior to the start of the fellowship. Nevertheless, more than 70% of fellows remained very or extremely interested in gaining additional experience in each competency during fellowship.

DISCUSSION

Survey respondents demonstrate variable levels of interest and engagement in TM training; in particular, fellows and graduates often reported greater interest and value in a TM rotation than PDs. Similar to fellows in related fields,10 PHM fellows and graduates selected clinical topics as the most essential elements of TM training. In accordance with the literature, our findings suggest that direct patient care, one-on-one instruction, and simulation would be appropriate and popular methods for delivering this type of educational content.10,11

Curriculum design for a TM rotation should reinforce clinical PHM competencies related to TM while focusing on topics that are specific to the transport environment, such as methods of interfacility transport, handoffs, transitions of care, and team leadership.2,7,12 Trainee comfort level with different forms of transport (eg, fear of flying, motion sickness) and local and state policies regarding interfacility transfer should also be considered. In addition, fellows could engage in clinical research and quality improvement projects related to TM given the overall paucity of literature in the field.13

Several reasons can explain why fellows and graduates place a greater value on a TM rotation than PDs. Fellows and graduates may perceive inherent value in gaining particular knowledge and skills, such as greater understanding of the logistics and personnel involved in transferring patients and experience working with a healthcare team in a unique and dynamic setting.3,10,14

PDs may not be aware of the extent of participation in elements of transport among graduates. A recent workforce survey of pediatric interfacility transport systems indicated that although medical directors are from the fields of emergency, critical care, and neonatal medicine, 20% of medical control physicians are pediatric hospitalists.4 Given that the majority of PHM fellowships are based at children’s hospitals and transport teams are often associated with intensive care or emergency medicine units, PDs may have limited exposure to transport systems that incorporate hospitalists.

Pediatric hospitalists at all practice sites must have clinical and systems skills related to TM. However, the scope of practice for those working at community sites may be more likely to include distinct elements of TM.6 Currently, most fellowship graduates work at free-standing children’s or university-affiliated hospitals and have pursued careers in academic medicine.15 As the field evolves, the number of fellowship-trained pediatric hospitalists working at community sites may increase, making the acquisition of skills relevant to TM during fellowship training more crucial.

This study has several limitations. We attempted to identify all recent PHM fellowship graduates, but sampling bias may exist. Response bias may have been introduced by the self-reporting of skill and proficiency as well as by the small sample size and response rate for some stakeholder groups. The latter may be exacerbated by the fact that we do not have data on the degree or distribution of program representation among the fellow and graduate groups, given the lack of identifying information collected. Finally, we did not collect specific information about existing TM curricula in PHM fellowships.

We report a variable level of interest and engagement in TM among fellowship stakeholders, even though “Transport of the Critically Ill Child” is a PHM Core Competency. Fellows are interested in TM but unsure of its relevance to a PHM career. Graduates support the acquisition of transport skills during fellowship training.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Tony Woodward, MD for reviewing the survey tools; Sheree Schrager, PhD and Margaret Trost, MD for their valuable insights into the results; and Grant Christman, MD for reviewing the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was secured for this study.

1. Insoft RM, Schwartz HP, Romito J. Guidelines for Air and Ground Transport of Neonatal and Pediatric Patients., 4th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2016.

2. Rosenthal JL, Romano PS, Kokroko J, Gu W, Okumura MJ. Profiling interfacility transfers for hospitalized pediatric patients. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(6):335-343. PubMed

3. Kline-Krammes S, Wheeler DS, Schwartz HP, Forbes M, Bigham MT. Missed opportunities during pediatric residency training. Report of a 10-year follow-up survey in critical care transport medicine. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(1):1-5. PubMed

4. Tanem J, Triscari D, Chan M, Meyer MT. Workforce survey of pediatric interfacility transport systems in the United States. Pediatr Emer Care. 2016;32(6):364-370. PubMed

5. Freed GL, Dunham KM. Pediatric hospitalists: training, current practice, and career goals. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):179-186. PubMed

6. Roberts KB. Pediatric hospitalists in community hospitals: hospital-based generalists with expanded roles. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(5):290-292. PubMed

7. Stucky ER, Maniscalco J, Ottolini MC, et al. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies Supplement: a Framework for Curriculum Development by the Society of Hospital Medicine with acknowledgement to pediatric hospitalists from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Academic Pediatric Association. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(suppl 2):i-xv, 1-114. PubMed

8. Jerardi KE, Fisher E, Rassbach C, et al. Development of a Curricular Framework for Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellowships. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):1-8. PubMed

9. Shah NH, Rhim HJH, Maniscalco J, Wilson K, Rassbach C. The current state of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships: A survey of program directors. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):324-328. PubMed

10. Mickells GE, Goodman DM, Rozenfeld RA. Education of pediatric subspecialty fellows in transport medicine: a national survey. BMC Pediatrics. 2017;17(1):13. PubMed

11. Cross B, Wilson D. High-fidelity simulation for transport team training and competency evaluation. Newborn Inf Nurs Rev. 2009;9(4):200-206.

12. Weingart C, Herstich T, Baker P, et al. Making good better: implementing a standardized handoff in pediatric transport. Air Med J. 2013;32(1):40-46. PubMed

13. Kandil SB, Sanford HA, Northrup V, Bigham MT, Giuliano Jr. JS. Transport disposition using transport risk assessment in pediatrics (TRAP) score. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012;16(3):366-373. PubMed

14. Giardino AP, Tran XG, King J, Giardino ER, Woodward GA, Durbin DR. A longitudinal view of resident education in pediatric emergency interhospital transport. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(9):653-658. PubMed

15. Oshimurua JM, Bauer BD, Shah N, Nguyen N, Maniscalco J. Current roles and perceived needs of pediatric hospital medicine fellowship graduates. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(10):633-637 PubMed

1. Insoft RM, Schwartz HP, Romito J. Guidelines for Air and Ground Transport of Neonatal and Pediatric Patients., 4th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2016.

2. Rosenthal JL, Romano PS, Kokroko J, Gu W, Okumura MJ. Profiling interfacility transfers for hospitalized pediatric patients. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(6):335-343. PubMed

3. Kline-Krammes S, Wheeler DS, Schwartz HP, Forbes M, Bigham MT. Missed opportunities during pediatric residency training. Report of a 10-year follow-up survey in critical care transport medicine. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(1):1-5. PubMed

4. Tanem J, Triscari D, Chan M, Meyer MT. Workforce survey of pediatric interfacility transport systems in the United States. Pediatr Emer Care. 2016;32(6):364-370. PubMed

5. Freed GL, Dunham KM. Pediatric hospitalists: training, current practice, and career goals. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):179-186. PubMed

6. Roberts KB. Pediatric hospitalists in community hospitals: hospital-based generalists with expanded roles. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(5):290-292. PubMed

7. Stucky ER, Maniscalco J, Ottolini MC, et al. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies Supplement: a Framework for Curriculum Development by the Society of Hospital Medicine with acknowledgement to pediatric hospitalists from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Academic Pediatric Association. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(suppl 2):i-xv, 1-114. PubMed

8. Jerardi KE, Fisher E, Rassbach C, et al. Development of a Curricular Framework for Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellowships. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):1-8. PubMed

9. Shah NH, Rhim HJH, Maniscalco J, Wilson K, Rassbach C. The current state of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships: A survey of program directors. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):324-328. PubMed

10. Mickells GE, Goodman DM, Rozenfeld RA. Education of pediatric subspecialty fellows in transport medicine: a national survey. BMC Pediatrics. 2017;17(1):13. PubMed

11. Cross B, Wilson D. High-fidelity simulation for transport team training and competency evaluation. Newborn Inf Nurs Rev. 2009;9(4):200-206.

12. Weingart C, Herstich T, Baker P, et al. Making good better: implementing a standardized handoff in pediatric transport. Air Med J. 2013;32(1):40-46. PubMed

13. Kandil SB, Sanford HA, Northrup V, Bigham MT, Giuliano Jr. JS. Transport disposition using transport risk assessment in pediatrics (TRAP) score. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012;16(3):366-373. PubMed

14. Giardino AP, Tran XG, King J, Giardino ER, Woodward GA, Durbin DR. A longitudinal view of resident education in pediatric emergency interhospital transport. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(9):653-658. PubMed

15. Oshimurua JM, Bauer BD, Shah N, Nguyen N, Maniscalco J. Current roles and perceived needs of pediatric hospital medicine fellowship graduates. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(10):633-637 PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

The Current State of PHM Fellowships

Pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) fellowship programs came into existence approximately 20 years ago in Canada,[1] and since that time the number of programs in North America has grown dramatically. The first 3 PHM fellowship programs in the United States were initiated in 2003, and by 2008 there were 7 active programs. Just 5 years later in 2013, there were 20 fellowship programs in existence. Now, in 2015, there are over 30 programs, with several more in development. The goal of postresidency training in PHM is to improve the care of hospitalized children by training future hospitalists to provide high‐quality, evidence‐based clinical care and to generate new knowledge and scholarship in areas such as clinical research, patient safety and quality improvement, medical education, practice management, and patient outcomes.[2] Many pediatric hospitalists want to be able to perform research or quality improvement, but feel that they lack the time, skills, resources, and mentorship to do so.[3] To date, fellowship‐trained hospitalists have a demonstrated track record of contributing to the body of literature that is shaping the care of hospitalized children.[4, 5]

At present, PHM is not a recognized subspecialty of the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) and therefore does not fall under the purview of the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), leading to concern from some about the variability in depth and breadth of training across programs.[1] The development and publication of the PHM Core Competencies in 2010 helped define the scope of practice of pediatric hospitalists and provide guidelines for training programs, specifically with respect to clinical and nonclinical areas for assessment of competency.[6] Furthermore, studies of early career hospitalists have identified areas for future fellowship curriculum development, such as core procedural skills, quality improvement, and practice management.[7]

In an effort to address training variability across programs, PHM fellowship directors (FDs) have come together as an organized group, first meeting in 2008, with the primary goal of defining training standards and sharing curricular resources. Annual meetings of the FDs, sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP‐SOHM), began in 2012. A key objective of this annual meeting has been to develop a standardized fellowship curriculum for use across programs as well as to determine gaps in training that need to be addressed. During this process, we have received input from key stakeholders including community hospitalists, internal medicine‐pediatrics hospitalists, and the PHM Certification Steering Committee, which organized the application for subspecialty certification to the ABP. To inform this process of curriculum standardization, we fielded a survey of PHM fellowship directors. The purpose of this article is to summarize the current curricula, operations, and logistics of PHM fellowship programs.

METHODS

This was a cross‐sectional study of 31 PHM fellowship programs across the United States and Canada in April 2014. Inclusion criteria included all pediatric fellowships that were self‐identified to the AAP‐SOHM as providing a hospital medicine fellowship option. This included both PHM fellowships as well as academic general pediatric fellowships with a hospitalist track. A web‐based survey (SurveyMonkey, Inc.) was distributed by e‐mail to the FDs at the 31 training programs (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article). To enhance content validity of survey responses, survey questions were designed using an iterative consensus process among the authors, who included junior and senior FDs and represented the 2014 annual FD meeting planning committee. Items were created to gather feedback on the following key areas of PHM fellowships: program demographics, types of required and elective clinical rotations, graduate coursework offerings, amount of time spent in clinical activities, fellow billing practices, and description of fellows' research activities. The survey consisted of 30 multiple‐choice and short‐answer questions. Follow‐up e‐mail reminders were sent to all FDs 2 weeks and 4 weeks after the initial request was sent. Survey completion was voluntary, and no incentives were offered. The study was determined to be exempt by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board. Data were summarized using frequency distributions. No subgroup comparisons were made.

RESULTS

Program directors from 27/31 (87%) PHM fellowship programs responded to the survey; 25 were active programs, and 2 were under development. Responding programs represented all 4 major regions of the country and Canada, with varying program initiation dates, ranging from 1997 to 2013.

Program Demographics

The duration of most programs (17/27) was 2 years (63%), with 6 (22%) 1‐year programs and 4 (15%) 3‐year programs making up the remainder. Four programs described variable lengths, which could be tailored based on the fellow's individual interest. Two of the programs are 2 years in length, but offer a 1‐year option for fellows who wish to focus on enhancing clinical skills without an academic focus. The other 2 programs are 2 years in length, but will offer an extension to a third year for those pursuing a graduate degree.

Fellow Clinical Activities

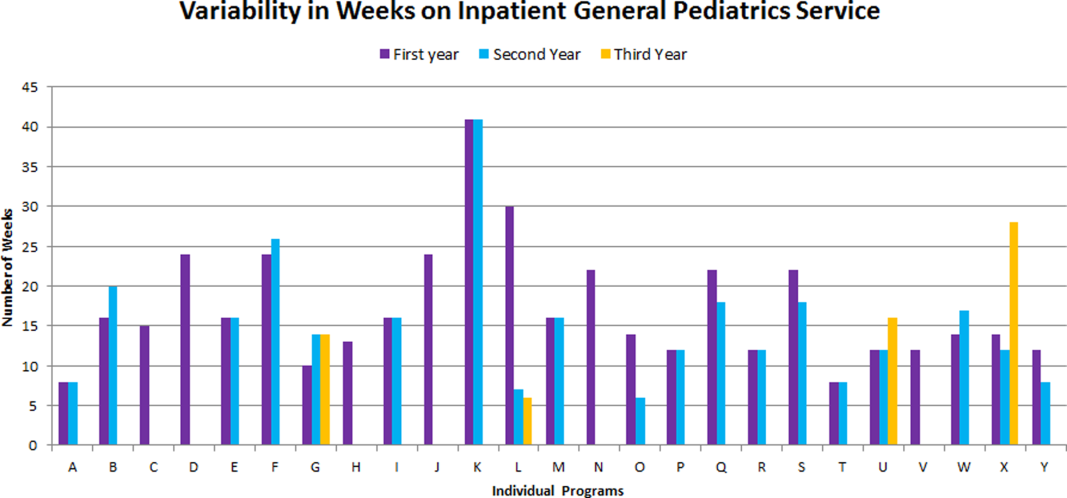

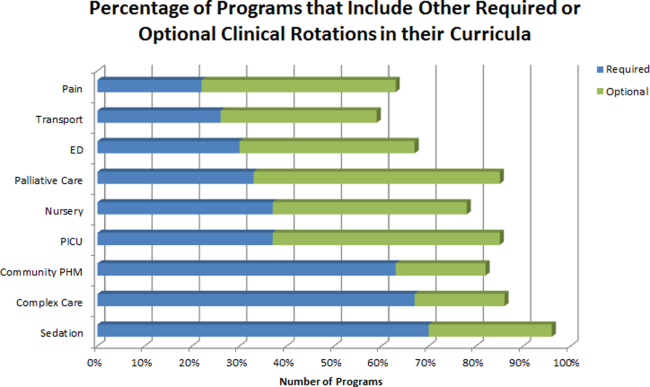

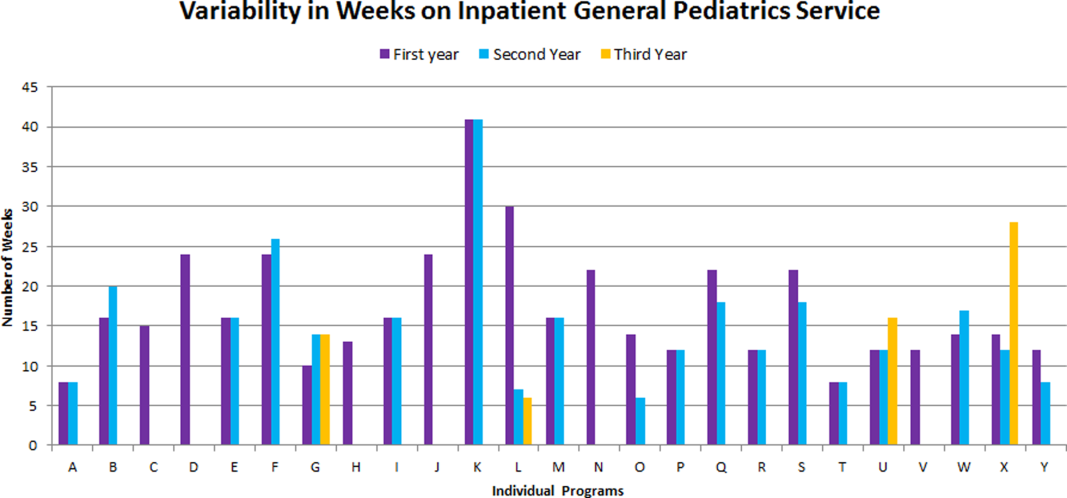

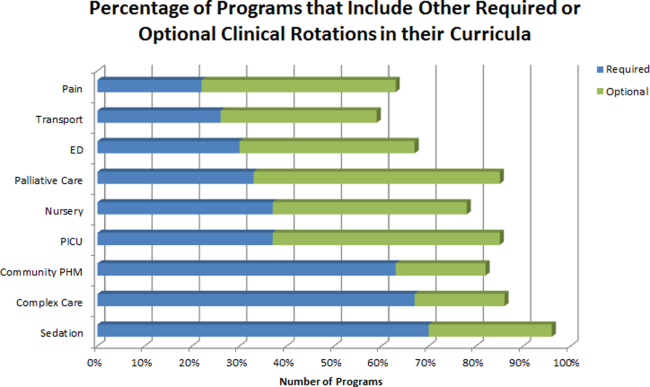

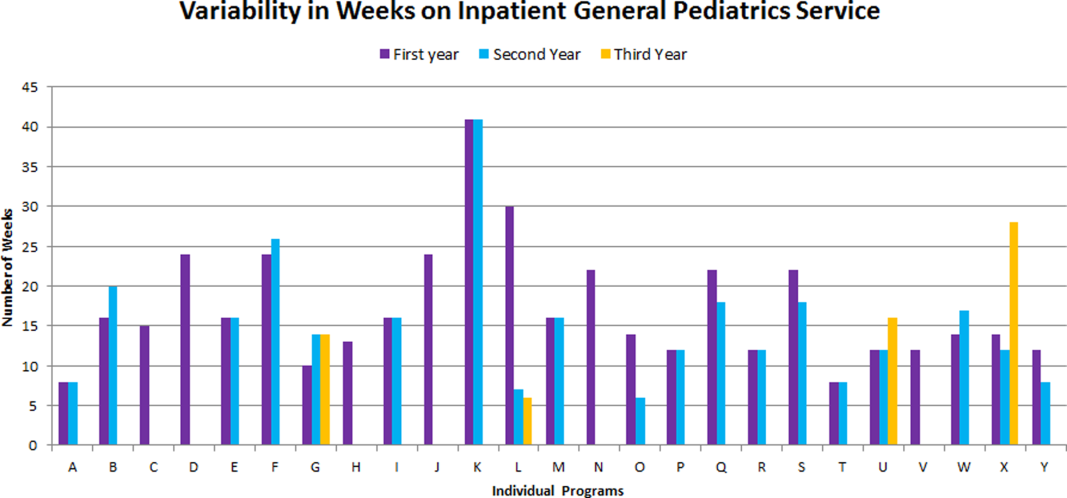

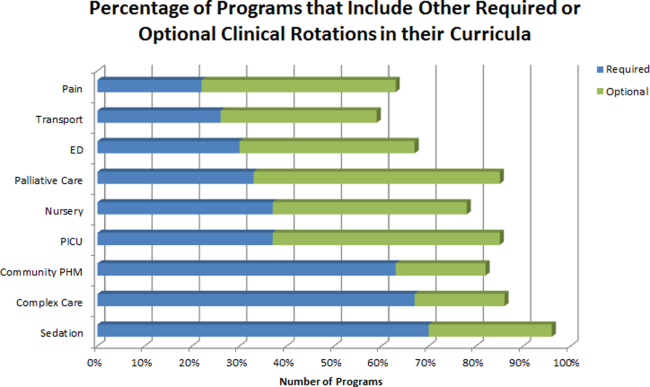

The average amount of total clinical time (weeks on service) across responding programs was 50% (range, 20%65%). When looking specifically at time on the inpatient general pediatric service, number of weeks varied by year of training and by institution, with 12 to 41 weeks in the first year of fellowship, 6 to 41 weeks in the second year of fellowship, and 6 to 28 weeks in the third year of fellowship (Figure 1). Though the range is large, on average, fellows spend 17 weeks on inpatient general pediatrics service during each year of training. Of note, the median number of weeks on inpatient general pediatrics service by year of training was 15 weeks, 16 weeks, and 16.5 weeks, respectively. In addition to inpatient general pediatrics service time, most programs require other clinical rotations, with sedation, complex care, and inpatient pediatrics at community sites being the most frequent (Figure 2). Of the 6 responding 1‐year programs, 5 (83%) allow fellows to bill/generate clinical revenue at some point during their training. Of the 15 responding 2‐year programs, 11 (73%) allow fellows to bill/generate clinical revenue at some point during their training. Of the 4 responding 3‐year programs, 2 (50%) allow their fellows to bill/generate clinical revenue at some point during their training.

Fellow Scholarly Activities

With respect to time dedicated to research, the majority of programs offer coursework such as courses for credit, noncredit courses, or certificate courses. In addition, 11 programs offer fellows a masters' degree in areas including public health, clinical science, epidemiology, education, academic sciences, healthcare quality, clinical and translational research, or health services administration. The majority of these degrees are paid for by departmental funds, with tuition reimbursement, university support, training grants, and personal funds making up the remainder. Twenty‐one (81%) programs provide a scholarship oversight committee for their fellows. Current fellows' (n = 63) primary areas of research are varied and include clinical research (36%), quality‐improvement research (22%), medical education research (20%), health services research (16%), and other areas (6%).

DISCUSSION

This is the most comprehensive description of pediatric hospital medicine fellowship curricula to date. Understanding the scope of these programs is an important first step in developing a standardized curriculum that can be used by all. The results of this survey indicate that although there is variability among PHM fellowship curricular content, several common themes exist.

The number of clinical weeks on the inpatient general pediatrics service varied from program to program, though the majority of programs require fellows to spend 15 to 16 weeks each year of training. The variability may be due in part to the way in which respondents defined the term week on clinical service. For example, if the fellow is primarily on a shift schedule, then he/she may only work 2 to 3 shifts in 1 week, which may have been viewed similarly to daily presence on a more traditional inpatient teaching service with 5 to 7 consecutive days of service. The current study did not explore the details of inpatient general pediatric clinical activities or exposure to opportunities to hone procedural skills, areas that are worth investigating as we move forward to better understand the needs of trainees.

Most residency training programs in general pediatrics require a significant amount of inpatient clinical time, specifically a minimum of 10 units or months, though only half of this time is required to be in inpatient general pediatrics.[8] Although nonfellowship trained early career hospitalists may feel adequately prepared to manage the clinical care of some hospitalized children, perceived competency is significantly lower than their fellowship‐trained colleagues with regard to care of the child with medical complexity and technology‐dependence, and with regard to provision of sedation for procedures.[7] The majority of FDs surveyed in our study indicated that additional clinical experience with sedation, complex care, and inpatient pediatrics at community sites were required of their fellows. Of note, many of these rotations are not commonly required in pediatric residency training programs; however, the PHM core competencies suggest that hospitalists should demonstrate proficiency in these areas to provide optimal care for hospitalized children. Our results suggest that current PHM fellowship curricula help address these clinical gaps. The requirement of these particular specialized experiences may reflect the clinical scope of practice that is expected from potential employers or may be related to staffing needs. It is well documented that the inpatient demographic of large pediatric tertiary care referral centers has changed over the past decade, with an increasing prevalence of children with medical complexity.[9, 10] In both tertiary referral centers and community hospitals, the expansion of the role of the hospitalist in providing specialized clinical services, such as sedation or surgical comanagement, has been significantly driven by financial factors, though a more recent focus on improvement of efficiency and quality of care within the hospital system has relied heavily on hospitalist input.[11, 12, 13] Important next steps in curriculum standardization include ensuring that training programs allow for adequate clinical exposure and proper assessment of competency in these areas, and determining the full complement of clinical training experiences that will produce hospitalists with a well‐defined scope of practice that adequately addresses the needs of hospitalized children.

Most fellowship‐trained hospitalists work primarily in university‐affiliated institutions with expectations for scholarly productivity.[5, 7] Fellowship‐trained hospitalists have made large contributions to the growing body of PHM literature, specifically in the realms of medical education, healthcare quality, clinical pediatrics, and healthcare outcomes.[4] Many PHM fellowship‐trained hospitalists have educational or administrative leadership roles.[2] Our results indicate that current PHM fellows continue to be active in a variety of research activities. In addition, FDs reported that the vast majority of programs included scholarship oversight committees, which ensure a mentored and structured research experience. Finally, most programs require or offer additional coursework, and many programs with university affiliations allow for attainment of graduate degrees. Inclusion of robust research training and infrastructure in all programs is a paramount goal of PHM fellowship training. This will allow graduates to be successful researchers, generating new knowledge and supporting the provision of high‐quality, evidence‐based, and value‐driven care for hospitalized children.

A unique feature of several PHM fellowship programs is that fellows are allowed to bill for clinical encounters. Many programs rely on clinical revenue to support fellow salaries.[14] For some programs, a portion of this clinical revenue comes from fellows billing for clinical encounters.[15] Programs that allow fellows to bill/generate clinical revenue have fellows working in attending roles without direct supervision, whereas nonbilling fellows have direct supervision by an attending.[15] In the current ABP training model, subspecialty fellows cannot independently bill for clinical encounters within their own subspecialty, though they can moonlight as long as they meet the duty hour requirements set forth by the ACGME.[16] FDs will need to consider the impact of this requirement on fellow autonomy and on financial revenue for funding fellow salaries if the field achieves ABP subspecialty status.

Regardless of whether or not PHM becomes a designated subspecialty of the ABP, FDs will continue to work together to develop a standard core curriculum that incorporates elements of clinical and nonclinical training to ensure that graduates not only provide high‐quality care for hospitalized children, but also generate new knowledge that advances the field in care delivery and quality of care in any setting. The results of this study will not only help to inform curriculum standardization, but also assessment and evaluation methods. Currently, PHM FDs meet annually and are nearing consensus on a standard 2‐year curriculum based on the PHM Core Competencies that incorporates core clinical, systems, and scholarly domains. We continue to solicit the input of stakeholders, including new FDs, community hospitalist leaders, internal medicine‐pediatrics hospitalist leaders, the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine, and leaders of national organizations, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, Academic Pediatrics Association, and Society of Hospital Medicine. Additional work around standardizing the fellowship application and recruitment process has resulted in our recent acceptance into the Fall Subspecialty Match through the National Residency Match Program, as well as development and implementation of a common fellowship application form. The FD group has recently formalized, voting into place an executive steering committee, which is responsible for the development and execution of long‐term goals that include finalizing a standardized curriculum, refining program and fellow assessment methods through critical evaluation of fellow metrics and outcomes, and standardization of evaluation methods.

Adopting a standard 2‐year curriculum may affect some programs, specifically those that are currently 1 year in duration. These programs would need to extend the length of their fellowship to allow for the breadth of experiences expected with a standardized 2‐year curriculum. This could result in significant financial challenges, effectively increasing the cost to administer the program. In addition, at present, programs have the flexibility to highlight individual areas of strength to attract candidates, allowing fellows to gain an in‐depth experience in domains such as clinical research, quality improvement, medical education, or health services research. With a standardized curriculum, some programs may have to assemble specific clinical and nonclinical experiences to meet the agreed‐upon expectations for PHM fellowship training. If these resources are not available, programs may need to seek relationships with other institutions to complete their offerings, a possibility that is being actively explored by this group. FDs continue to work with each other to share resources, identify training opportunities, and partner with each other to ensure that the requirements of a standard curriculum can be met.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a voluntary survey of program directors, and though we captured over 80% of programs at the time of the survey, there are currently more programs that have come into existence and more still that are in the development stage, leading to potential sampling error. Second, variable effort or accuracy by participants may have led to some degree of response error, such as content error or nonreporting error. Third, the survey questions focused on high‐level information, making it difficult to make nuanced comparisons between curricular elements or determine best curricular practice. In addition, this survey did not explore medical education and quality improvement activities of fellows, 2 major areas in which hospitalists play a major role in the inpatient setting.[1, 17, 18, 19, 20]

CONCLUSION

PHM fellowship programs have grown and continue to grow at a rapid rate. Variability in training is evident, both in clinical experiences and research experiences, though several common elements were identified in this study. The majority of programs are 2 years, and clinical experience comprises approximately 50% of training time, often including key rotations such as sedation, complex care, and rotations at community hospitals. Future directions include standardizing clinical training and expectations for scholarship, formulating appropriate methods for assessment of competency that can be used across programs, and seeking sustainable sources of funding.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , . Characteristics of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships and training programs. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):157–163.

- , . Pediatric hospitalists in medical education: current roles and future directions. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2012;42(5):120–126.

- , , . Research needs of pediatric hospitalists. Hosp Pediatr. 2011;1(1):38–44.

- , , , . Pediatric hospital medicine fellowships: outcomes and future directions. Paper presented at: Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2014; July 26, 2014; Orlando, FL.

- , , . Pediatric hospitalist research productivity: predictors of success at presenting abstracts and publishing peer‐reviewed manuscripts among pediatric hospitalists. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2(3):149–160.

- , , . Pediatric hospital medicine core competencies: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:339–343.

- , , , . Perceived core competency achievements of fellowship and non‐fellowship early career pediatric hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):373–389.

- Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in pediatrics. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/2013‐PR‐FAQ‐PIF/320_pediatrics_07012013.pdf. Published September 30, 2012. Accessed July 7, 2015.

- , , , , , . Increasing prevalence of medically complex children in US hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):638–646.

- , , , et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647–655.

- , . The expanding role of hospitalists in the United States. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136:591–596.

- , , , , , . Pediatric hospitalist comanagement of spinal fusion surgery patients. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(1):23–30.

- , , , , . Development of a pediatric hospitalist sedation service: training and implementation. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(4):335–339.

- , . Sources of funding and support for pediatric hospital medicine fellowship programs. Poster presented at: Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2014; July 27, 2014; Orlando, FL.

- Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellowship Directors. Pediatric Hospital Medicine Fellowship Directors Annual Meeting: funding and return on investment. July 24, 2014.

- Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education. Frequently asked questions: ACGME common duty hour requirements. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PDFs/dh‐faqs2011.pdf. Updated June 18, 2014. Accessed July 7, 2015.

- , . Pediatric hospitalists: training, current practice and career goals. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):179–186.

- , . The hospitalist movement and its implications for the care of hospitalized children. Pediatrics. 1999;103:473–477.

- . Pediatric hospitalists and medical education. Pediatr Ann. 2014;43(7):e151–e156

- , , , et al. Quality improvement research in pediatric hospital medicine and the role of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) network. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(6):S54–S60.

Pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) fellowship programs came into existence approximately 20 years ago in Canada,[1] and since that time the number of programs in North America has grown dramatically. The first 3 PHM fellowship programs in the United States were initiated in 2003, and by 2008 there were 7 active programs. Just 5 years later in 2013, there were 20 fellowship programs in existence. Now, in 2015, there are over 30 programs, with several more in development. The goal of postresidency training in PHM is to improve the care of hospitalized children by training future hospitalists to provide high‐quality, evidence‐based clinical care and to generate new knowledge and scholarship in areas such as clinical research, patient safety and quality improvement, medical education, practice management, and patient outcomes.[2] Many pediatric hospitalists want to be able to perform research or quality improvement, but feel that they lack the time, skills, resources, and mentorship to do so.[3] To date, fellowship‐trained hospitalists have a demonstrated track record of contributing to the body of literature that is shaping the care of hospitalized children.[4, 5]

At present, PHM is not a recognized subspecialty of the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) and therefore does not fall under the purview of the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), leading to concern from some about the variability in depth and breadth of training across programs.[1] The development and publication of the PHM Core Competencies in 2010 helped define the scope of practice of pediatric hospitalists and provide guidelines for training programs, specifically with respect to clinical and nonclinical areas for assessment of competency.[6] Furthermore, studies of early career hospitalists have identified areas for future fellowship curriculum development, such as core procedural skills, quality improvement, and practice management.[7]

In an effort to address training variability across programs, PHM fellowship directors (FDs) have come together as an organized group, first meeting in 2008, with the primary goal of defining training standards and sharing curricular resources. Annual meetings of the FDs, sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP‐SOHM), began in 2012. A key objective of this annual meeting has been to develop a standardized fellowship curriculum for use across programs as well as to determine gaps in training that need to be addressed. During this process, we have received input from key stakeholders including community hospitalists, internal medicine‐pediatrics hospitalists, and the PHM Certification Steering Committee, which organized the application for subspecialty certification to the ABP. To inform this process of curriculum standardization, we fielded a survey of PHM fellowship directors. The purpose of this article is to summarize the current curricula, operations, and logistics of PHM fellowship programs.

METHODS

This was a cross‐sectional study of 31 PHM fellowship programs across the United States and Canada in April 2014. Inclusion criteria included all pediatric fellowships that were self‐identified to the AAP‐SOHM as providing a hospital medicine fellowship option. This included both PHM fellowships as well as academic general pediatric fellowships with a hospitalist track. A web‐based survey (SurveyMonkey, Inc.) was distributed by e‐mail to the FDs at the 31 training programs (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article). To enhance content validity of survey responses, survey questions were designed using an iterative consensus process among the authors, who included junior and senior FDs and represented the 2014 annual FD meeting planning committee. Items were created to gather feedback on the following key areas of PHM fellowships: program demographics, types of required and elective clinical rotations, graduate coursework offerings, amount of time spent in clinical activities, fellow billing practices, and description of fellows' research activities. The survey consisted of 30 multiple‐choice and short‐answer questions. Follow‐up e‐mail reminders were sent to all FDs 2 weeks and 4 weeks after the initial request was sent. Survey completion was voluntary, and no incentives were offered. The study was determined to be exempt by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board. Data were summarized using frequency distributions. No subgroup comparisons were made.

RESULTS

Program directors from 27/31 (87%) PHM fellowship programs responded to the survey; 25 were active programs, and 2 were under development. Responding programs represented all 4 major regions of the country and Canada, with varying program initiation dates, ranging from 1997 to 2013.

Program Demographics

The duration of most programs (17/27) was 2 years (63%), with 6 (22%) 1‐year programs and 4 (15%) 3‐year programs making up the remainder. Four programs described variable lengths, which could be tailored based on the fellow's individual interest. Two of the programs are 2 years in length, but offer a 1‐year option for fellows who wish to focus on enhancing clinical skills without an academic focus. The other 2 programs are 2 years in length, but will offer an extension to a third year for those pursuing a graduate degree.

Fellow Clinical Activities

The average amount of total clinical time (weeks on service) across responding programs was 50% (range, 20%65%). When looking specifically at time on the inpatient general pediatric service, number of weeks varied by year of training and by institution, with 12 to 41 weeks in the first year of fellowship, 6 to 41 weeks in the second year of fellowship, and 6 to 28 weeks in the third year of fellowship (Figure 1). Though the range is large, on average, fellows spend 17 weeks on inpatient general pediatrics service during each year of training. Of note, the median number of weeks on inpatient general pediatrics service by year of training was 15 weeks, 16 weeks, and 16.5 weeks, respectively. In addition to inpatient general pediatrics service time, most programs require other clinical rotations, with sedation, complex care, and inpatient pediatrics at community sites being the most frequent (Figure 2). Of the 6 responding 1‐year programs, 5 (83%) allow fellows to bill/generate clinical revenue at some point during their training. Of the 15 responding 2‐year programs, 11 (73%) allow fellows to bill/generate clinical revenue at some point during their training. Of the 4 responding 3‐year programs, 2 (50%) allow their fellows to bill/generate clinical revenue at some point during their training.

Fellow Scholarly Activities

With respect to time dedicated to research, the majority of programs offer coursework such as courses for credit, noncredit courses, or certificate courses. In addition, 11 programs offer fellows a masters' degree in areas including public health, clinical science, epidemiology, education, academic sciences, healthcare quality, clinical and translational research, or health services administration. The majority of these degrees are paid for by departmental funds, with tuition reimbursement, university support, training grants, and personal funds making up the remainder. Twenty‐one (81%) programs provide a scholarship oversight committee for their fellows. Current fellows' (n = 63) primary areas of research are varied and include clinical research (36%), quality‐improvement research (22%), medical education research (20%), health services research (16%), and other areas (6%).

DISCUSSION

This is the most comprehensive description of pediatric hospital medicine fellowship curricula to date. Understanding the scope of these programs is an important first step in developing a standardized curriculum that can be used by all. The results of this survey indicate that although there is variability among PHM fellowship curricular content, several common themes exist.

The number of clinical weeks on the inpatient general pediatrics service varied from program to program, though the majority of programs require fellows to spend 15 to 16 weeks each year of training. The variability may be due in part to the way in which respondents defined the term week on clinical service. For example, if the fellow is primarily on a shift schedule, then he/she may only work 2 to 3 shifts in 1 week, which may have been viewed similarly to daily presence on a more traditional inpatient teaching service with 5 to 7 consecutive days of service. The current study did not explore the details of inpatient general pediatric clinical activities or exposure to opportunities to hone procedural skills, areas that are worth investigating as we move forward to better understand the needs of trainees.

Most residency training programs in general pediatrics require a significant amount of inpatient clinical time, specifically a minimum of 10 units or months, though only half of this time is required to be in inpatient general pediatrics.[8] Although nonfellowship trained early career hospitalists may feel adequately prepared to manage the clinical care of some hospitalized children, perceived competency is significantly lower than their fellowship‐trained colleagues with regard to care of the child with medical complexity and technology‐dependence, and with regard to provision of sedation for procedures.[7] The majority of FDs surveyed in our study indicated that additional clinical experience with sedation, complex care, and inpatient pediatrics at community sites were required of their fellows. Of note, many of these rotations are not commonly required in pediatric residency training programs; however, the PHM core competencies suggest that hospitalists should demonstrate proficiency in these areas to provide optimal care for hospitalized children. Our results suggest that current PHM fellowship curricula help address these clinical gaps. The requirement of these particular specialized experiences may reflect the clinical scope of practice that is expected from potential employers or may be related to staffing needs. It is well documented that the inpatient demographic of large pediatric tertiary care referral centers has changed over the past decade, with an increasing prevalence of children with medical complexity.[9, 10] In both tertiary referral centers and community hospitals, the expansion of the role of the hospitalist in providing specialized clinical services, such as sedation or surgical comanagement, has been significantly driven by financial factors, though a more recent focus on improvement of efficiency and quality of care within the hospital system has relied heavily on hospitalist input.[11, 12, 13] Important next steps in curriculum standardization include ensuring that training programs allow for adequate clinical exposure and proper assessment of competency in these areas, and determining the full complement of clinical training experiences that will produce hospitalists with a well‐defined scope of practice that adequately addresses the needs of hospitalized children.

Most fellowship‐trained hospitalists work primarily in university‐affiliated institutions with expectations for scholarly productivity.[5, 7] Fellowship‐trained hospitalists have made large contributions to the growing body of PHM literature, specifically in the realms of medical education, healthcare quality, clinical pediatrics, and healthcare outcomes.[4] Many PHM fellowship‐trained hospitalists have educational or administrative leadership roles.[2] Our results indicate that current PHM fellows continue to be active in a variety of research activities. In addition, FDs reported that the vast majority of programs included scholarship oversight committees, which ensure a mentored and structured research experience. Finally, most programs require or offer additional coursework, and many programs with university affiliations allow for attainment of graduate degrees. Inclusion of robust research training and infrastructure in all programs is a paramount goal of PHM fellowship training. This will allow graduates to be successful researchers, generating new knowledge and supporting the provision of high‐quality, evidence‐based, and value‐driven care for hospitalized children.

A unique feature of several PHM fellowship programs is that fellows are allowed to bill for clinical encounters. Many programs rely on clinical revenue to support fellow salaries.[14] For some programs, a portion of this clinical revenue comes from fellows billing for clinical encounters.[15] Programs that allow fellows to bill/generate clinical revenue have fellows working in attending roles without direct supervision, whereas nonbilling fellows have direct supervision by an attending.[15] In the current ABP training model, subspecialty fellows cannot independently bill for clinical encounters within their own subspecialty, though they can moonlight as long as they meet the duty hour requirements set forth by the ACGME.[16] FDs will need to consider the impact of this requirement on fellow autonomy and on financial revenue for funding fellow salaries if the field achieves ABP subspecialty status.

Regardless of whether or not PHM becomes a designated subspecialty of the ABP, FDs will continue to work together to develop a standard core curriculum that incorporates elements of clinical and nonclinical training to ensure that graduates not only provide high‐quality care for hospitalized children, but also generate new knowledge that advances the field in care delivery and quality of care in any setting. The results of this study will not only help to inform curriculum standardization, but also assessment and evaluation methods. Currently, PHM FDs meet annually and are nearing consensus on a standard 2‐year curriculum based on the PHM Core Competencies that incorporates core clinical, systems, and scholarly domains. We continue to solicit the input of stakeholders, including new FDs, community hospitalist leaders, internal medicine‐pediatrics hospitalist leaders, the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine, and leaders of national organizations, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, Academic Pediatrics Association, and Society of Hospital Medicine. Additional work around standardizing the fellowship application and recruitment process has resulted in our recent acceptance into the Fall Subspecialty Match through the National Residency Match Program, as well as development and implementation of a common fellowship application form. The FD group has recently formalized, voting into place an executive steering committee, which is responsible for the development and execution of long‐term goals that include finalizing a standardized curriculum, refining program and fellow assessment methods through critical evaluation of fellow metrics and outcomes, and standardization of evaluation methods.

Adopting a standard 2‐year curriculum may affect some programs, specifically those that are currently 1 year in duration. These programs would need to extend the length of their fellowship to allow for the breadth of experiences expected with a standardized 2‐year curriculum. This could result in significant financial challenges, effectively increasing the cost to administer the program. In addition, at present, programs have the flexibility to highlight individual areas of strength to attract candidates, allowing fellows to gain an in‐depth experience in domains such as clinical research, quality improvement, medical education, or health services research. With a standardized curriculum, some programs may have to assemble specific clinical and nonclinical experiences to meet the agreed‐upon expectations for PHM fellowship training. If these resources are not available, programs may need to seek relationships with other institutions to complete their offerings, a possibility that is being actively explored by this group. FDs continue to work with each other to share resources, identify training opportunities, and partner with each other to ensure that the requirements of a standard curriculum can be met.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a voluntary survey of program directors, and though we captured over 80% of programs at the time of the survey, there are currently more programs that have come into existence and more still that are in the development stage, leading to potential sampling error. Second, variable effort or accuracy by participants may have led to some degree of response error, such as content error or nonreporting error. Third, the survey questions focused on high‐level information, making it difficult to make nuanced comparisons between curricular elements or determine best curricular practice. In addition, this survey did not explore medical education and quality improvement activities of fellows, 2 major areas in which hospitalists play a major role in the inpatient setting.[1, 17, 18, 19, 20]

CONCLUSION

PHM fellowship programs have grown and continue to grow at a rapid rate. Variability in training is evident, both in clinical experiences and research experiences, though several common elements were identified in this study. The majority of programs are 2 years, and clinical experience comprises approximately 50% of training time, often including key rotations such as sedation, complex care, and rotations at community hospitals. Future directions include standardizing clinical training and expectations for scholarship, formulating appropriate methods for assessment of competency that can be used across programs, and seeking sustainable sources of funding.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) fellowship programs came into existence approximately 20 years ago in Canada,[1] and since that time the number of programs in North America has grown dramatically. The first 3 PHM fellowship programs in the United States were initiated in 2003, and by 2008 there were 7 active programs. Just 5 years later in 2013, there were 20 fellowship programs in existence. Now, in 2015, there are over 30 programs, with several more in development. The goal of postresidency training in PHM is to improve the care of hospitalized children by training future hospitalists to provide high‐quality, evidence‐based clinical care and to generate new knowledge and scholarship in areas such as clinical research, patient safety and quality improvement, medical education, practice management, and patient outcomes.[2] Many pediatric hospitalists want to be able to perform research or quality improvement, but feel that they lack the time, skills, resources, and mentorship to do so.[3] To date, fellowship‐trained hospitalists have a demonstrated track record of contributing to the body of literature that is shaping the care of hospitalized children.[4, 5]

At present, PHM is not a recognized subspecialty of the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) and therefore does not fall under the purview of the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), leading to concern from some about the variability in depth and breadth of training across programs.[1] The development and publication of the PHM Core Competencies in 2010 helped define the scope of practice of pediatric hospitalists and provide guidelines for training programs, specifically with respect to clinical and nonclinical areas for assessment of competency.[6] Furthermore, studies of early career hospitalists have identified areas for future fellowship curriculum development, such as core procedural skills, quality improvement, and practice management.[7]