User login

Enhancing Access to Yoga for Older Male Veterans After Cancer: Examining Beliefs About Yoga

Yoga is an effective clinical intervention for cancer survivors. Studies indicate a wide range of benefits, including improvements in physical functioning, emotional well-being and overall quality of life.1-7 Two-thirds of National Cancer Institute designated comprehensive cancer centers offer yoga on-site.8 Yoga is endorsed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American Society of Clinical Oncology for managing symptoms, such as cancer-related anxiety and depression and for improving overall quality of life.9,10

Although the positive effects of yoga on cancer patients are well studied, most published research in this area reports on predominantly middle-aged women with breast cancer.11,12 Less is known about the use of yoga in other groups of cancer patients, such as older adults, veterans, and those from diverse racial or ethnic backgrounds. This gap in the literature is concerning considering that the majority of cancer survivors are aged 60 years or older, and veterans face unique risk factors for cancer associated with herbicide exposure (eg, Agent Orange) and other military-related noxious exposures.13,14 Older cancer survivors may have more difficulty recovering from treatment-related adverse effects, making it especially important to target recovery efforts to older adults.15 Yoga can be adapted for older cancer survivors with age-related comorbidities, similar to adaptations made for older adults who are not cancer survivors but require accommodations for physical limitations.16-20 Similarly, yoga programs targeted to racially diverse cancer survivors are associated with improved mood and well-being in racially diverse cancer survivors, but studies suggest community engagement and cultural adaptation may be important to address the needs of culturally diverse cancer survivors.21-23

Yoga has been increasingly studied within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and has been found effective in reducing symptoms through the use of trauma-informed and military-relevant instruction as well as a military veteran yoga teacher.24-26 This work has not targeted older veterans or cancer survivors who may be more difficult to recruit into such programs, but who would nevertheless benefit.

Clinically, the VHA whole health model is providing increased opportunities for veterans to engage in holistic care including yoga.27 Resources include in-person yoga classes (varies by facility), videos, and handouts with practices uniquely designed for veterans or wounded warriors. As clinicians increasingly refer veterans to these programs, it will be important to develop strategies to engage older veterans in these services.

One important strategy to enhancing access to yoga for older veterans is to consider beliefs about yoga. Beliefs about yoga or general expectations about the outcomes of yoga may be critical to consider in expanding access to yoga in underrepresented groups. Beliefs about yoga may include beliefs about yoga improving health, yoga being difficult or producing discomfort, and yoga involving specific social norms.28 For example, confidence in one’s ability to perform yoga despite discomfort predicted class attendance and practice in a sample of 32 breast cancer survivors.29 Relatedly, positive beliefs about the impact of yoga on health were associated with improvements in mood and quality of life in a sample of 66 cancer survivors.30

The aim of this study was to examine avenues to enhance access to yoga for older veterans, including those from diverse backgrounds, with a focus on the role of beliefs. In the first study we investigate the association between beliefs about and barriers to yoga in a group of older cancer survivors, and we consider the role of demographic and clinical variables in such beliefs and how education may alter beliefs. In alignment with the whole health model of holistic health, we posit that yoga educational materials and resources may contribute to yoga beliefs and work to decrease these barriers. We apply these findings in a second study that enrolled older veterans in yoga and examining the impact of program participation on beliefs and the role of beliefs in program outcomes. In the discussion we return to consider how to increase access to yoga to older veterans based on these findings.

Methods

Study 1 participants were identified from VHA tumor registries. Eligible patients had head and neck, esophageal, gastric, or colorectal cancers and were excluded if they were in hospice care, had dementia, or had a psychotic spectrum disorder. Participants completed a face-to-face semistructured interview at 6, 12, and 18 months after their cancer diagnosis with a trained interviewer. Complete protocol methods, including nonresponder information, are described elsewhere.31

Questions about yoga were asked at the 12 month postdiagnosis interview. Participants were read the following: “Here is a list of services some patients use to recover from cancer. Please tell me if you have used any of these.” The list included yoga, physical therapy, occupational therapy, exercise, meditation, or massage therapy. Next participants were provided education about yoga via the following description: “Yoga is a practice of stress reduction and exercise with stretching, holding positions and deep breathing. For some, it may improve your sleep, energy, flexibility, anxiety, and pain. The postures are done standing, sitting, or lying down. If needed, it can be done all from a chair.” We then asked whether they would attend if yoga was offered at the VHA hospital (yes, no, maybe). Participants provided brief responses to 2 open-ended questions: (“If I came to a yoga class, I …”; and “Is there anything that might make you more likely to come to a yoga class?”) Responses were transcribed verbatim and entered into a database for qualitative analysis. Subsequently, participants completed standardized measures of health-related quality of life and beliefs about yoga as described below.

Study 2 participants were identified from VHA tumor registries and a cancer support group. Eligible patients had a diagnosis of cancer (any type except basil cell carcinoma) within the previous 3 years and were excluded if they were in hospice care, had dementia, or had a psychotic spectrum disorder. Participants completed face-to-face semistructured interviews with a trained interviewer before and after participation in an 8-week yoga group that met twice per week. Complete protocol methods are described elsewhere.16 This paper focuses on 28 of the 37 enrolled patients for whom we have complete pre- and postclass interview data. We previously reported on adaptations made to yoga in our pilot group of 14 individuals, who in this small sample did not show statistically significant changes in their quality of life from before to after the class.16 This analysis includes those 14 individuals and 14 who participated in additional classes, focusing on beliefs, which were not previously reported.

Measures

Participants reported their age, gender, ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino or not), race, and level of education. Information about the cancer diagnosis, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cancer stage, and treatments was obtained from the medical record. The Physical Function and Anxiety Subscales from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System were used to measure health-related quality of life (HRQoL).32-34 Items are rated on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

The Beliefs About Yoga Scale (BAYS) was used to measure beliefs about the outcomes of engaging in yoga.28 The 11-item scale has 3 factors: expected health benefits (5 items), expected discomfort (3 items), and expected social norms (3 items). Items from the expected discomfort and expected social norms are reverse scored so that a higher score indicates more positive beliefs. To reduce participant burden, in study 1 we selected 1 item from each factor with high factor loadings in the original cross-validation sample.28 It would improve my overall health (Benefit, factor loading = .89); I would have to be more flexible to take a class (Discomfort, factor loading = .67); I would be embarrassed in a class (Social norms, factor loading = .75). Participants in study 2 completed the entire 11-item scale. Items were summed to create subscales and total scales.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used in study 1 to characterize participants’ yoga experience and interest. Changes in interest pre- and posteducation were evaluated with χ2 comparison of distribution. The association of beliefs about yoga with 3 levels of interest (yes, no, maybe) was evaluated through analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing the mean score on the summed BAYS items among the 3 groups. The association of demographic (age, education, race) and clinical factors (AJCC stage, physical function) with BAYS was determined through multivariate linear regression.

For analytic purposes, due to small subgroup sample sizes we compared those who identified as non-Hispanic White adults to those who identified as African American/Hispanic/other persons. To further evaluate the relationship of age to yoga beliefs, we examined beliefs about yoga in 3 age groups (40-59 years [n = 24]; 60-69 years [n = 58]; 70-89 years [n = 28]) using ANOVA comparing the mean score on the summed BAYS items among the 3 groups. In study 2, changes in interest before and after the yoga program were evaluated with paired t tests and repeated ANOVA, with beliefs about yoga prior to class as a covariate. The association of demographic and clinical factors with BAYS was determined as in the first sample through multivariate linear regression, except the variable of race was not included due to small sample size (ie, only 3 individuals identified as persons of color).

Thematic analysis in which content-related codes were developed and subsequently grouped together was applied to the data of 110 participants who responded to the open-ended survey questions in study 1 to further illuminate responses to closed-ended questions.35 Transcribed responses to the open-ended questions were transferred to a spreadsheet. An initial code book with code names, definitions, and examples was developed based on an inductive method by one team member (EA).35 Initially, coding and tabulation were conducted separately for each question but it was noted that content extended across response prompts (eg, responses to question 2 “What might make you more likely to come?” were spontaneously provided when answering question 1), thus coding was collapsed across questions. Next, 2 team members (EA, KD) coded the same responses, meeting weekly to discuss discrepancies. The code book was revised following each meeting to reflect refinements in code names and definitions, adding newly generated codes as needed. The process continued until consensus and data saturation was obtained, with 90% intercoder agreement. Next, these codes were subjected to thematic analysis by 2 team members (EA, KD) combining codes into 6 overarching themes. The entire team reviewed the codes and identified 2 supra themes: positive beliefs or facilitators and negative beliefs or barriers.

Consistent with the concept of reflexivity in qualitative research, we acknowledge the influence of the research team members on the qualitative process.36 The primary coding team (EA, KD) are both researchers and employees of Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System who have participated in other research projects involving veterans and qualitative analyses but are not yoga instructors or yoga researchers.

Results

Study 1

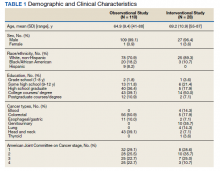

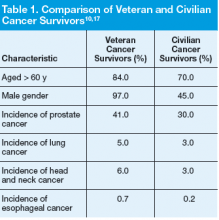

The sample of 110 military veterans was mostly male (99.1%) with a mean (SD) age of 64.9 (9.4) years (range, 41-88)(Table 1). The majority (70.9%) described their race/ethnicity as White, non-Hispanic followed by Black/African American (18.2%) and Hispanic (8.2%) persons; 50.0% had no more than a high school education. The most common cancer diagnoses were colorectal (50.9%), head and neck (39.1%), and esophageal and gastric (10.0%) and ranged from AJCC stages I to IV.

When first asked, the majority of participants (78.2%) reported that they were not interested in yoga, 16.4% reported they might be interested, and 5.5% reported they had tried a yoga class since their cancer diagnosis. In contrast, 40.9% used exercise, 32.7% used meditation, 14.5% used physical or occupational therapy, and 11.8% used massage therapy since their cancer diagnosis.

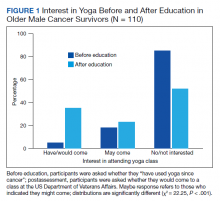

After participants were provided the brief scripted education about yoga, the level of interest shifted: 46.4% not interested, 21.8% interested, and 31.8% definitely interested, demonstrating a statistically significant shift in interest following education (χ2 = 22.25, P < .001) (Figure 1). Those with the most positive beliefs about yoga were most likely to indicate interest. Using the BAYS 3-item survey, the mean (SD) for the definitely interested, might be interested, and not interested groups was 15.1 (3.2), 14.1 (3.2), and 12.3 (2.5), respectively (F = 10.63, P < .001).

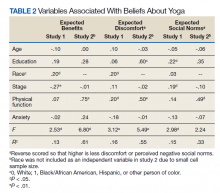

A multivariable regression was run to examine possible associations between participants’ demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and beliefs about yoga as measured by the 3 BAYS items (Table 2). Higher expected health benefits of yoga was associated with identifying as

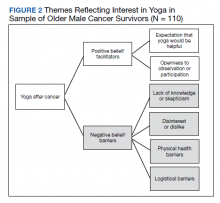

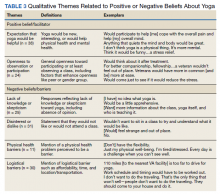

Six themes were identified in qualitative analysis of semistructured interviews reflecting older veterans’ beliefs about yoga, which were grouped into the following suprathemes of positive vs negative beliefs (Figure 2). Exemplar responses appear in Table 3.

Study 2 Intervention Sample

This sample of 28 veterans was mostly male (96.4%) with a mean (SD) age of 69.2 (10.9) years (range, 57-87). The majority (89.3%) described their race as White, followed by Black/African American (10.7%); no participants self-identified in other categories for race/ethnicity. Twelve veterans (42.9%) had no more than a high school education. The most common cancer diagnosis was genitourinary (35.7%) and the AJCC stage ranged from I to IV.

We employed information learned in study 1 to enhance access in study 2. We mailed letters to 278 veterans diagnosed with cancer in the previous 3 years that provided education about yoga based on study 1 findings. Of 207 veterans reached by phone, 133 (64%) stated they were not interested in coming to a yoga class; 74 (36%) were interested, but 30 felt they were unable to attend due to obstacles such as illness or travel. Ultimately 37 (18%) veterans agreed and consented to the class, and 28 (14%) completed postclass surveys.

In multivariate regression, higher expected health benefits of yoga were associated with higher physical function, lower concern about expected discomfort was also associated with higher physical function as well as higher education; similarly, lower concern about expected social norms was associated with higher physical function. Age was not associated with any of the BAYS factors.

Beliefs about yoga improved from before to after class for all 3 domains with greater expected benefit and lower concerns about discomfort or social norms:

Discussion

Yoga is an effective clinical intervention for addressing some long-term adverse effects in cancer survivors, although the body of research focuses predominantly on middle aged, female, White, college-educated breast cancer survivors. There is no evidence to suggest yoga would be less effective in other groups, but it has not been extensively studied in survivors from diverse subgroups. Beliefs about yoga are a factor that may enhance interest in yoga interventions and research, and measures aimed at addressing potential beliefs and fears may capture information that can be used to support older cancer survivors in holistic health. The aims of this study were to examine beliefs about yoga in 2 samples of older cancer survivors who received VHA care. The main findings are (1) interest in yoga was initially low and lower than that of other complementary or exercise-based interventions, but increased when participants were provided brief education about yoga; (2) interest in yoga was associated with beliefs about yoga with qualitative comments illuminating these beliefs; (3) demographic characteristics (education, race) and physical function were associated with beliefs about yoga; and (4) positive beliefs about yoga increased following a brief yoga intervention and was associated with improvements in physical function.

Willingness to consider a class appeared to shift for some older veterans when they were presented brief information about yoga that explained what is involved, how it might help, and that it could be done from a chair if needed. These findings clearly indicated that when trying to enhance participation in yoga in clinical or research programs, it will be important that recruitment materials provide such information. This finding is consistent with the qualitative findings that reflected a lack of knowledge or skepticism about benefits of yoga among some participants. Given the finding that physical function was associated with beliefs about yoga and was also a prominent theme in qualitative analyses,

Age was not associated with beliefs about yoga in either study. Importantly, in a more detailed study 1 follow-up analysis, beliefs about yoga were equivalent for aged > 70 years compared with those aged 40 to 69 years. It is not entirely clear why older adults have been underrepresented in studies of yoga in cancer survivors. However, older adults are vastly underrepresented in clinical trials for many health conditions, even though they are more likely to experience many diseases, including cancer.37 A new National Institutes of Health policy requires that individuals of all ages, including older adults, must be included in all human subjects research unless there are scientific reasons not to include them.38 It is therefore imperative to consider strategies to address underrepresentation of older adults.

Qualitative findings here suggest it will be important to consider logistical barriers including transportation and affordability as well as adaptations requested by older adults (eg, preferences for older teachers).18

Although our sample was small, we also found that adults from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds had more positive beliefs about yoga, such that this finding should be interpreted with caution. Similar to older adults, individuals from diverse racial and ethnic groups are also underrepresented in clinical trials and may have lower access to complementary treatments. Cultural and linguistic adaptations and building community partnerships should be considered in both recruitment and intervention delivery strategies.40We learned that education about yoga may increase interest and that it is possible to recruit older veterans to yoga class. Nevertheless, in study 2, our rate of full participation was low, with only about 1 in 10 participating. Additional efforts to enhance beliefs about yoga and to addresslogistical barriers (offering telehealth yoga) are needed to best reach older veterans.

Limitations

These findings have several limitations. First, participants were homogeneous in age, gender, race/ethnicity and veteran status, which provides a window into this understudied population but limits generalizability and our ability to control across populations. Second, the sample size limited the ability to conduct subgroup and interaction analyses, such as examining potential differential effects of cancer type, treatment, and PTSD on yoga beliefs or to consider the relationship of yoga beliefs with changes in quality of life before and after the yoga intervention in study 2. Additionally, age was not associated with beliefs about yoga in these samples that of mostly older adults. We were able to compare middle-aged and older adults but could not compare beliefs about yoga to adults aged in their 20s and 30s. Last, our study excluded people with dementia and psychotic disorders. Further research is needed to examine yoga for older cancer survivors who have these conditions.

Conclusions

Education that specifically informs potential participants about yoga practice, potential modifications, and potential benefits, as well as adaptations to programs that address physical and logistical barriers may be useful in increasing access to and participation in yoga for older Veterans who are cancer survivors.

Acknowledgments/Funding

The authors have no financial or personal relationships to disclose. This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Rehabilitation Research and Development Service. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Boston Healthcare System, Bedford VA Medical Center, and Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas. We thank the members of the Veterans Cancer Rehabilitation Study (Vetcares) Research teams in Boston and in Houston and the veterans who have participated in our research studies and allow us to contribute to their health care.

1. Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Janelsins M, et al. Multicenter, randomized controlled trial of yoga for sleep quality among cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(26):3233-3241. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.7707

2. Chandwani KD, Thornton B, Perkins GH, et al. Yoga improves quality of life and benefit finding in women undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2010;8(2):43-55.

3. Erratum: Primary follicular lymphoma of disguised as multiple miliary like lesions: A case report and review of literature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2018;61(4):643. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.243009

4. Eyigor S, Uslu R, Apaydın S, Caramat I, Yesil H. Can yoga have any effect on shoulder and arm pain and quality of life in patients with breast cancer? A randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;32:40-45. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.04.010

5. Loudon A, Barnett T, Piller N, Immink MA, Williams AD. Yoga management of breast cancer-related lymphoedema: a randomised controlled pilot-trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:214. Published 2014 Jul 1. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-14-214

6. Browning KK, Kue J, Lyons F, Overcash J. Feasibility of mind-body movement programs for cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44(4):446-456. doi:10.1188/17.ONF.446-456

7. Rosenbaum MS, Velde J. The effects of yoga, massage, and reiki on patient well-being at a cancer resource center. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20(3):E77-E81. doi:10.1188/16.CJON.E77-E81

8. Yun H, Sun L, Mao JJ. Growth of integrative medicine at leading cancer centers between 2009 and 2016: a systematic analysis of NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center websites. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2017;2017(52):lgx004. doi:10.1093/jncimonographs/lgx004

9. Sanft T, Denlinger CS, Armenian S, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: survivorship, version 2.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(7):784-794. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2019.0034

10. Lyman GH, Greenlee H, Bohlke K, et al. Integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment: ASCO endorsement of the SIO clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(25):2647-2655. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.79.2721

11. Culos-Reed SN, Mackenzie MJ, Sohl SJ, Jesse MT, Zahavich AN, Danhauer SC. Yoga & cancer interventions: a review of the clinical significance of patient reported outcomes for cancer survivors. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:642576. doi:10.1155/2012/642576

12. Danhauer SC, Addington EL, Cohen L, et al. Yoga for symptom management in oncology: a review of the evidence base and future directions for research. Cancer. 2019;125(12):1979-1989. doi:10.1002/cncr.31979

13. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34. doi:10.3322/caac.21551

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans’ diseases associated with Agent Orange. Updated June 16, 2021. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/agentorange/conditions

15. Deimling GT, Arendt JA, Kypriotakis G, Bowman KF. Functioning of older, long-term cancer survivors: the role of cancer and comorbidities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(suppl 2):S289-S292. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02515.x

16. King K, Gosian J, Doherty K, et al. Implementing yoga therapy adapted for older veterans who are cancer survivors. Int J Yoga Therap. 2014;24:87-96.

17. Wertman A, Wister AV, Mitchell BA. On and off the mat: yoga experiences of middle-aged and older adults. Can J Aging. 2016;35(2):190-205. doi:10.1017/S0714980816000155

18. Chen KM, Wang HH, Li CH, Chen MH. Community vs. institutional elders’ evaluations of and preferences for yoga exercises. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(7-8):1000-1007. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03337.x

19. Saravanakumar P, Higgins IJ, Van Der Riet PJ, Sibbritt D. Tai chi and yoga in residential aged care: perspectives of participants: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(23-24):4390-4399. doi:10.1111/jocn.14590

20. Fan JT, Chen KM. Using silver yoga exercises to promote physical and mental health of elders with dementia in long-term care facilities. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(8):1222-1230. doi:10.1017/S1041610211000287

21. Taylor TR, Barrow J, Makambi K, et al. A restorative yoga intervention for African-American breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):62-72. doi:10.1007/s40615-017-0342-4

22. Moadel AB, Shah C, Wylie-Rosett J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of yoga among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: effects on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(28):4387-4395. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6027

23. Smith SA, Whitehead MS, Sheats JQ, Chubb B, Alema-Mensah E, Ansa BE. Community engagement to address socio-ecological barriers to physical activity among African American breast cancer survivors. J Ga Public Health Assoc. 2017;6(3):393-397. doi:10.21633/jgpha.6.312

24. Cushing RE, Braun KL, Alden C-Iayt SW, Katz AR. Military-Tailored Yoga for Veterans with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Mil Med. 2018;183(5-6):e223-e231. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx071

25. Davis LW, Schmid AA, Daggy JK, et al. Symptoms improve after a yoga program designed for PTSD in a randomized controlled trial with veterans and civilians. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(8):904-912. doi:10.1037/tra0000564

26. Chopin SM, Sheerin CM, Meyer BL. Yoga for warriors: An intervention for veterans with comorbid chronic pain and PTSD. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(8):888-896. doi:10.1037/tra0000649

27. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Whole health. Updated September 13, 2021. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth

28. Sohl SJ, Schnur JB, Daly L, Suslov K, Montgomery GH. Development of the beliefs about yoga scale. Int J Yoga Therap. 2011;(21):85-91.

29. Cadmus-Bertram L, Littman AJ, Ulrich CM, et al. Predictors of adherence to a 26-week viniyoga intervention among post-treatment breast cancer survivors. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(9):751-758. doi:10.1089/acm.2012.0118

30. Mackenzie MJ, Carlson LE, Ekkekakis P, Paskevich DM, Culos-Reed SN. Affect and mindfulness as predictors of change in mood disturbance, stress symptoms, and quality of life in a community-based yoga program for cancer survivors. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:419496. doi:10.1155/2013/419496

31. Naik AD, Martin LA, Karel M, et al. Cancer survivor rehabilitation and recovery: protocol for the Veterans Cancer Rehabilitation Study (Vet-CaRes). BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:93. Published 2013 Mar 11. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-13-93

32. Northwestern University. PROMIS Health Organization and the PROMIS Cooperative Group. PROMIS Short Form v2.0 - Physical Function 6b. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php?option=com_instruments&view=measure&id=793&Itemid=992

33. Northwestern University. PROMIS Health Organization and the PROMIS Cooperative Group. PROMIS Short Form v1.0 - Anxiety 6a. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php?option=com_instruments&view=measure&id=145&Itemid=992

34. Northwestern University. PROMIS Health Organization and the PROMIS Cooperative Group. PROMIS-43 Profile v2.1. Accessed September 24, 2021. https://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php?option=com_instruments&view=measure&id=858&Itemid=992

35. Todd NJ, Jones SH, Lobban FA. “Recovery” in bipolar disorder: how can service users be supported through a self-management intervention? A qualitative focus group study. J Ment Health. 2012;21(2):114-126. doi:10.3109/09638237.2011.621471

36. Finlay L. “Outing” the researcher: the provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(4):531-545. doi:10.1177/104973202129120052

37. Herrera AP, Snipes SA, King DW, Torres-Vigil I, Goldberg DS, Weinberg AD. Disparate inclusion of older adults in clinical trials: priorities and opportunities for policy and practice change. Am J Public Health. 2010;10(suppl 1):S105-S112. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.162982

38. National Institutes of Health. Revision: NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of individuals across the lifespan as participants in research involving human subjects. Published December 19, 2017. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-18-116.html

39. Townsley CA, Selby R, Siu LL. Systematic review of barriers to the recruitment of older patients with cancer onto clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(13):3112-3124. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.00.141

40. Vuong I, Wright J, Nolan MB, et al. Overcoming barriers: evidence-based strategies to increase enrollment of underrepresented populations in cancer therapeutic clinical trials-a narrative review. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35(5):841-849. doi:10.1007/s13187-019-01650-y

Yoga is an effective clinical intervention for cancer survivors. Studies indicate a wide range of benefits, including improvements in physical functioning, emotional well-being and overall quality of life.1-7 Two-thirds of National Cancer Institute designated comprehensive cancer centers offer yoga on-site.8 Yoga is endorsed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American Society of Clinical Oncology for managing symptoms, such as cancer-related anxiety and depression and for improving overall quality of life.9,10

Although the positive effects of yoga on cancer patients are well studied, most published research in this area reports on predominantly middle-aged women with breast cancer.11,12 Less is known about the use of yoga in other groups of cancer patients, such as older adults, veterans, and those from diverse racial or ethnic backgrounds. This gap in the literature is concerning considering that the majority of cancer survivors are aged 60 years or older, and veterans face unique risk factors for cancer associated with herbicide exposure (eg, Agent Orange) and other military-related noxious exposures.13,14 Older cancer survivors may have more difficulty recovering from treatment-related adverse effects, making it especially important to target recovery efforts to older adults.15 Yoga can be adapted for older cancer survivors with age-related comorbidities, similar to adaptations made for older adults who are not cancer survivors but require accommodations for physical limitations.16-20 Similarly, yoga programs targeted to racially diverse cancer survivors are associated with improved mood and well-being in racially diverse cancer survivors, but studies suggest community engagement and cultural adaptation may be important to address the needs of culturally diverse cancer survivors.21-23

Yoga has been increasingly studied within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and has been found effective in reducing symptoms through the use of trauma-informed and military-relevant instruction as well as a military veteran yoga teacher.24-26 This work has not targeted older veterans or cancer survivors who may be more difficult to recruit into such programs, but who would nevertheless benefit.

Clinically, the VHA whole health model is providing increased opportunities for veterans to engage in holistic care including yoga.27 Resources include in-person yoga classes (varies by facility), videos, and handouts with practices uniquely designed for veterans or wounded warriors. As clinicians increasingly refer veterans to these programs, it will be important to develop strategies to engage older veterans in these services.

One important strategy to enhancing access to yoga for older veterans is to consider beliefs about yoga. Beliefs about yoga or general expectations about the outcomes of yoga may be critical to consider in expanding access to yoga in underrepresented groups. Beliefs about yoga may include beliefs about yoga improving health, yoga being difficult or producing discomfort, and yoga involving specific social norms.28 For example, confidence in one’s ability to perform yoga despite discomfort predicted class attendance and practice in a sample of 32 breast cancer survivors.29 Relatedly, positive beliefs about the impact of yoga on health were associated with improvements in mood and quality of life in a sample of 66 cancer survivors.30

The aim of this study was to examine avenues to enhance access to yoga for older veterans, including those from diverse backgrounds, with a focus on the role of beliefs. In the first study we investigate the association between beliefs about and barriers to yoga in a group of older cancer survivors, and we consider the role of demographic and clinical variables in such beliefs and how education may alter beliefs. In alignment with the whole health model of holistic health, we posit that yoga educational materials and resources may contribute to yoga beliefs and work to decrease these barriers. We apply these findings in a second study that enrolled older veterans in yoga and examining the impact of program participation on beliefs and the role of beliefs in program outcomes. In the discussion we return to consider how to increase access to yoga to older veterans based on these findings.

Methods

Study 1 participants were identified from VHA tumor registries. Eligible patients had head and neck, esophageal, gastric, or colorectal cancers and were excluded if they were in hospice care, had dementia, or had a psychotic spectrum disorder. Participants completed a face-to-face semistructured interview at 6, 12, and 18 months after their cancer diagnosis with a trained interviewer. Complete protocol methods, including nonresponder information, are described elsewhere.31

Questions about yoga were asked at the 12 month postdiagnosis interview. Participants were read the following: “Here is a list of services some patients use to recover from cancer. Please tell me if you have used any of these.” The list included yoga, physical therapy, occupational therapy, exercise, meditation, or massage therapy. Next participants were provided education about yoga via the following description: “Yoga is a practice of stress reduction and exercise with stretching, holding positions and deep breathing. For some, it may improve your sleep, energy, flexibility, anxiety, and pain. The postures are done standing, sitting, or lying down. If needed, it can be done all from a chair.” We then asked whether they would attend if yoga was offered at the VHA hospital (yes, no, maybe). Participants provided brief responses to 2 open-ended questions: (“If I came to a yoga class, I …”; and “Is there anything that might make you more likely to come to a yoga class?”) Responses were transcribed verbatim and entered into a database for qualitative analysis. Subsequently, participants completed standardized measures of health-related quality of life and beliefs about yoga as described below.

Study 2 participants were identified from VHA tumor registries and a cancer support group. Eligible patients had a diagnosis of cancer (any type except basil cell carcinoma) within the previous 3 years and were excluded if they were in hospice care, had dementia, or had a psychotic spectrum disorder. Participants completed face-to-face semistructured interviews with a trained interviewer before and after participation in an 8-week yoga group that met twice per week. Complete protocol methods are described elsewhere.16 This paper focuses on 28 of the 37 enrolled patients for whom we have complete pre- and postclass interview data. We previously reported on adaptations made to yoga in our pilot group of 14 individuals, who in this small sample did not show statistically significant changes in their quality of life from before to after the class.16 This analysis includes those 14 individuals and 14 who participated in additional classes, focusing on beliefs, which were not previously reported.

Measures

Participants reported their age, gender, ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino or not), race, and level of education. Information about the cancer diagnosis, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cancer stage, and treatments was obtained from the medical record. The Physical Function and Anxiety Subscales from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System were used to measure health-related quality of life (HRQoL).32-34 Items are rated on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

The Beliefs About Yoga Scale (BAYS) was used to measure beliefs about the outcomes of engaging in yoga.28 The 11-item scale has 3 factors: expected health benefits (5 items), expected discomfort (3 items), and expected social norms (3 items). Items from the expected discomfort and expected social norms are reverse scored so that a higher score indicates more positive beliefs. To reduce participant burden, in study 1 we selected 1 item from each factor with high factor loadings in the original cross-validation sample.28 It would improve my overall health (Benefit, factor loading = .89); I would have to be more flexible to take a class (Discomfort, factor loading = .67); I would be embarrassed in a class (Social norms, factor loading = .75). Participants in study 2 completed the entire 11-item scale. Items were summed to create subscales and total scales.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used in study 1 to characterize participants’ yoga experience and interest. Changes in interest pre- and posteducation were evaluated with χ2 comparison of distribution. The association of beliefs about yoga with 3 levels of interest (yes, no, maybe) was evaluated through analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing the mean score on the summed BAYS items among the 3 groups. The association of demographic (age, education, race) and clinical factors (AJCC stage, physical function) with BAYS was determined through multivariate linear regression.

For analytic purposes, due to small subgroup sample sizes we compared those who identified as non-Hispanic White adults to those who identified as African American/Hispanic/other persons. To further evaluate the relationship of age to yoga beliefs, we examined beliefs about yoga in 3 age groups (40-59 years [n = 24]; 60-69 years [n = 58]; 70-89 years [n = 28]) using ANOVA comparing the mean score on the summed BAYS items among the 3 groups. In study 2, changes in interest before and after the yoga program were evaluated with paired t tests and repeated ANOVA, with beliefs about yoga prior to class as a covariate. The association of demographic and clinical factors with BAYS was determined as in the first sample through multivariate linear regression, except the variable of race was not included due to small sample size (ie, only 3 individuals identified as persons of color).

Thematic analysis in which content-related codes were developed and subsequently grouped together was applied to the data of 110 participants who responded to the open-ended survey questions in study 1 to further illuminate responses to closed-ended questions.35 Transcribed responses to the open-ended questions were transferred to a spreadsheet. An initial code book with code names, definitions, and examples was developed based on an inductive method by one team member (EA).35 Initially, coding and tabulation were conducted separately for each question but it was noted that content extended across response prompts (eg, responses to question 2 “What might make you more likely to come?” were spontaneously provided when answering question 1), thus coding was collapsed across questions. Next, 2 team members (EA, KD) coded the same responses, meeting weekly to discuss discrepancies. The code book was revised following each meeting to reflect refinements in code names and definitions, adding newly generated codes as needed. The process continued until consensus and data saturation was obtained, with 90% intercoder agreement. Next, these codes were subjected to thematic analysis by 2 team members (EA, KD) combining codes into 6 overarching themes. The entire team reviewed the codes and identified 2 supra themes: positive beliefs or facilitators and negative beliefs or barriers.

Consistent with the concept of reflexivity in qualitative research, we acknowledge the influence of the research team members on the qualitative process.36 The primary coding team (EA, KD) are both researchers and employees of Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System who have participated in other research projects involving veterans and qualitative analyses but are not yoga instructors or yoga researchers.

Results

Study 1

The sample of 110 military veterans was mostly male (99.1%) with a mean (SD) age of 64.9 (9.4) years (range, 41-88)(Table 1). The majority (70.9%) described their race/ethnicity as White, non-Hispanic followed by Black/African American (18.2%) and Hispanic (8.2%) persons; 50.0% had no more than a high school education. The most common cancer diagnoses were colorectal (50.9%), head and neck (39.1%), and esophageal and gastric (10.0%) and ranged from AJCC stages I to IV.

When first asked, the majority of participants (78.2%) reported that they were not interested in yoga, 16.4% reported they might be interested, and 5.5% reported they had tried a yoga class since their cancer diagnosis. In contrast, 40.9% used exercise, 32.7% used meditation, 14.5% used physical or occupational therapy, and 11.8% used massage therapy since their cancer diagnosis.

After participants were provided the brief scripted education about yoga, the level of interest shifted: 46.4% not interested, 21.8% interested, and 31.8% definitely interested, demonstrating a statistically significant shift in interest following education (χ2 = 22.25, P < .001) (Figure 1). Those with the most positive beliefs about yoga were most likely to indicate interest. Using the BAYS 3-item survey, the mean (SD) for the definitely interested, might be interested, and not interested groups was 15.1 (3.2), 14.1 (3.2), and 12.3 (2.5), respectively (F = 10.63, P < .001).

A multivariable regression was run to examine possible associations between participants’ demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and beliefs about yoga as measured by the 3 BAYS items (Table 2). Higher expected health benefits of yoga was associated with identifying as

Six themes were identified in qualitative analysis of semistructured interviews reflecting older veterans’ beliefs about yoga, which were grouped into the following suprathemes of positive vs negative beliefs (Figure 2). Exemplar responses appear in Table 3.

Study 2 Intervention Sample

This sample of 28 veterans was mostly male (96.4%) with a mean (SD) age of 69.2 (10.9) years (range, 57-87). The majority (89.3%) described their race as White, followed by Black/African American (10.7%); no participants self-identified in other categories for race/ethnicity. Twelve veterans (42.9%) had no more than a high school education. The most common cancer diagnosis was genitourinary (35.7%) and the AJCC stage ranged from I to IV.

We employed information learned in study 1 to enhance access in study 2. We mailed letters to 278 veterans diagnosed with cancer in the previous 3 years that provided education about yoga based on study 1 findings. Of 207 veterans reached by phone, 133 (64%) stated they were not interested in coming to a yoga class; 74 (36%) were interested, but 30 felt they were unable to attend due to obstacles such as illness or travel. Ultimately 37 (18%) veterans agreed and consented to the class, and 28 (14%) completed postclass surveys.

In multivariate regression, higher expected health benefits of yoga were associated with higher physical function, lower concern about expected discomfort was also associated with higher physical function as well as higher education; similarly, lower concern about expected social norms was associated with higher physical function. Age was not associated with any of the BAYS factors.

Beliefs about yoga improved from before to after class for all 3 domains with greater expected benefit and lower concerns about discomfort or social norms:

Discussion

Yoga is an effective clinical intervention for addressing some long-term adverse effects in cancer survivors, although the body of research focuses predominantly on middle aged, female, White, college-educated breast cancer survivors. There is no evidence to suggest yoga would be less effective in other groups, but it has not been extensively studied in survivors from diverse subgroups. Beliefs about yoga are a factor that may enhance interest in yoga interventions and research, and measures aimed at addressing potential beliefs and fears may capture information that can be used to support older cancer survivors in holistic health. The aims of this study were to examine beliefs about yoga in 2 samples of older cancer survivors who received VHA care. The main findings are (1) interest in yoga was initially low and lower than that of other complementary or exercise-based interventions, but increased when participants were provided brief education about yoga; (2) interest in yoga was associated with beliefs about yoga with qualitative comments illuminating these beliefs; (3) demographic characteristics (education, race) and physical function were associated with beliefs about yoga; and (4) positive beliefs about yoga increased following a brief yoga intervention and was associated with improvements in physical function.

Willingness to consider a class appeared to shift for some older veterans when they were presented brief information about yoga that explained what is involved, how it might help, and that it could be done from a chair if needed. These findings clearly indicated that when trying to enhance participation in yoga in clinical or research programs, it will be important that recruitment materials provide such information. This finding is consistent with the qualitative findings that reflected a lack of knowledge or skepticism about benefits of yoga among some participants. Given the finding that physical function was associated with beliefs about yoga and was also a prominent theme in qualitative analyses,

Age was not associated with beliefs about yoga in either study. Importantly, in a more detailed study 1 follow-up analysis, beliefs about yoga were equivalent for aged > 70 years compared with those aged 40 to 69 years. It is not entirely clear why older adults have been underrepresented in studies of yoga in cancer survivors. However, older adults are vastly underrepresented in clinical trials for many health conditions, even though they are more likely to experience many diseases, including cancer.37 A new National Institutes of Health policy requires that individuals of all ages, including older adults, must be included in all human subjects research unless there are scientific reasons not to include them.38 It is therefore imperative to consider strategies to address underrepresentation of older adults.

Qualitative findings here suggest it will be important to consider logistical barriers including transportation and affordability as well as adaptations requested by older adults (eg, preferences for older teachers).18

Although our sample was small, we also found that adults from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds had more positive beliefs about yoga, such that this finding should be interpreted with caution. Similar to older adults, individuals from diverse racial and ethnic groups are also underrepresented in clinical trials and may have lower access to complementary treatments. Cultural and linguistic adaptations and building community partnerships should be considered in both recruitment and intervention delivery strategies.40We learned that education about yoga may increase interest and that it is possible to recruit older veterans to yoga class. Nevertheless, in study 2, our rate of full participation was low, with only about 1 in 10 participating. Additional efforts to enhance beliefs about yoga and to addresslogistical barriers (offering telehealth yoga) are needed to best reach older veterans.

Limitations

These findings have several limitations. First, participants were homogeneous in age, gender, race/ethnicity and veteran status, which provides a window into this understudied population but limits generalizability and our ability to control across populations. Second, the sample size limited the ability to conduct subgroup and interaction analyses, such as examining potential differential effects of cancer type, treatment, and PTSD on yoga beliefs or to consider the relationship of yoga beliefs with changes in quality of life before and after the yoga intervention in study 2. Additionally, age was not associated with beliefs about yoga in these samples that of mostly older adults. We were able to compare middle-aged and older adults but could not compare beliefs about yoga to adults aged in their 20s and 30s. Last, our study excluded people with dementia and psychotic disorders. Further research is needed to examine yoga for older cancer survivors who have these conditions.

Conclusions

Education that specifically informs potential participants about yoga practice, potential modifications, and potential benefits, as well as adaptations to programs that address physical and logistical barriers may be useful in increasing access to and participation in yoga for older Veterans who are cancer survivors.

Acknowledgments/Funding

The authors have no financial or personal relationships to disclose. This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Rehabilitation Research and Development Service. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Boston Healthcare System, Bedford VA Medical Center, and Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas. We thank the members of the Veterans Cancer Rehabilitation Study (Vetcares) Research teams in Boston and in Houston and the veterans who have participated in our research studies and allow us to contribute to their health care.

Yoga is an effective clinical intervention for cancer survivors. Studies indicate a wide range of benefits, including improvements in physical functioning, emotional well-being and overall quality of life.1-7 Two-thirds of National Cancer Institute designated comprehensive cancer centers offer yoga on-site.8 Yoga is endorsed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and American Society of Clinical Oncology for managing symptoms, such as cancer-related anxiety and depression and for improving overall quality of life.9,10

Although the positive effects of yoga on cancer patients are well studied, most published research in this area reports on predominantly middle-aged women with breast cancer.11,12 Less is known about the use of yoga in other groups of cancer patients, such as older adults, veterans, and those from diverse racial or ethnic backgrounds. This gap in the literature is concerning considering that the majority of cancer survivors are aged 60 years or older, and veterans face unique risk factors for cancer associated with herbicide exposure (eg, Agent Orange) and other military-related noxious exposures.13,14 Older cancer survivors may have more difficulty recovering from treatment-related adverse effects, making it especially important to target recovery efforts to older adults.15 Yoga can be adapted for older cancer survivors with age-related comorbidities, similar to adaptations made for older adults who are not cancer survivors but require accommodations for physical limitations.16-20 Similarly, yoga programs targeted to racially diverse cancer survivors are associated with improved mood and well-being in racially diverse cancer survivors, but studies suggest community engagement and cultural adaptation may be important to address the needs of culturally diverse cancer survivors.21-23

Yoga has been increasingly studied within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) for treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and has been found effective in reducing symptoms through the use of trauma-informed and military-relevant instruction as well as a military veteran yoga teacher.24-26 This work has not targeted older veterans or cancer survivors who may be more difficult to recruit into such programs, but who would nevertheless benefit.

Clinically, the VHA whole health model is providing increased opportunities for veterans to engage in holistic care including yoga.27 Resources include in-person yoga classes (varies by facility), videos, and handouts with practices uniquely designed for veterans or wounded warriors. As clinicians increasingly refer veterans to these programs, it will be important to develop strategies to engage older veterans in these services.

One important strategy to enhancing access to yoga for older veterans is to consider beliefs about yoga. Beliefs about yoga or general expectations about the outcomes of yoga may be critical to consider in expanding access to yoga in underrepresented groups. Beliefs about yoga may include beliefs about yoga improving health, yoga being difficult or producing discomfort, and yoga involving specific social norms.28 For example, confidence in one’s ability to perform yoga despite discomfort predicted class attendance and practice in a sample of 32 breast cancer survivors.29 Relatedly, positive beliefs about the impact of yoga on health were associated with improvements in mood and quality of life in a sample of 66 cancer survivors.30

The aim of this study was to examine avenues to enhance access to yoga for older veterans, including those from diverse backgrounds, with a focus on the role of beliefs. In the first study we investigate the association between beliefs about and barriers to yoga in a group of older cancer survivors, and we consider the role of demographic and clinical variables in such beliefs and how education may alter beliefs. In alignment with the whole health model of holistic health, we posit that yoga educational materials and resources may contribute to yoga beliefs and work to decrease these barriers. We apply these findings in a second study that enrolled older veterans in yoga and examining the impact of program participation on beliefs and the role of beliefs in program outcomes. In the discussion we return to consider how to increase access to yoga to older veterans based on these findings.

Methods

Study 1 participants were identified from VHA tumor registries. Eligible patients had head and neck, esophageal, gastric, or colorectal cancers and were excluded if they were in hospice care, had dementia, or had a psychotic spectrum disorder. Participants completed a face-to-face semistructured interview at 6, 12, and 18 months after their cancer diagnosis with a trained interviewer. Complete protocol methods, including nonresponder information, are described elsewhere.31

Questions about yoga were asked at the 12 month postdiagnosis interview. Participants were read the following: “Here is a list of services some patients use to recover from cancer. Please tell me if you have used any of these.” The list included yoga, physical therapy, occupational therapy, exercise, meditation, or massage therapy. Next participants were provided education about yoga via the following description: “Yoga is a practice of stress reduction and exercise with stretching, holding positions and deep breathing. For some, it may improve your sleep, energy, flexibility, anxiety, and pain. The postures are done standing, sitting, or lying down. If needed, it can be done all from a chair.” We then asked whether they would attend if yoga was offered at the VHA hospital (yes, no, maybe). Participants provided brief responses to 2 open-ended questions: (“If I came to a yoga class, I …”; and “Is there anything that might make you more likely to come to a yoga class?”) Responses were transcribed verbatim and entered into a database for qualitative analysis. Subsequently, participants completed standardized measures of health-related quality of life and beliefs about yoga as described below.

Study 2 participants were identified from VHA tumor registries and a cancer support group. Eligible patients had a diagnosis of cancer (any type except basil cell carcinoma) within the previous 3 years and were excluded if they were in hospice care, had dementia, or had a psychotic spectrum disorder. Participants completed face-to-face semistructured interviews with a trained interviewer before and after participation in an 8-week yoga group that met twice per week. Complete protocol methods are described elsewhere.16 This paper focuses on 28 of the 37 enrolled patients for whom we have complete pre- and postclass interview data. We previously reported on adaptations made to yoga in our pilot group of 14 individuals, who in this small sample did not show statistically significant changes in their quality of life from before to after the class.16 This analysis includes those 14 individuals and 14 who participated in additional classes, focusing on beliefs, which were not previously reported.

Measures

Participants reported their age, gender, ethnicity (Hispanic/Latino or not), race, and level of education. Information about the cancer diagnosis, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) cancer stage, and treatments was obtained from the medical record. The Physical Function and Anxiety Subscales from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System were used to measure health-related quality of life (HRQoL).32-34 Items are rated on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

The Beliefs About Yoga Scale (BAYS) was used to measure beliefs about the outcomes of engaging in yoga.28 The 11-item scale has 3 factors: expected health benefits (5 items), expected discomfort (3 items), and expected social norms (3 items). Items from the expected discomfort and expected social norms are reverse scored so that a higher score indicates more positive beliefs. To reduce participant burden, in study 1 we selected 1 item from each factor with high factor loadings in the original cross-validation sample.28 It would improve my overall health (Benefit, factor loading = .89); I would have to be more flexible to take a class (Discomfort, factor loading = .67); I would be embarrassed in a class (Social norms, factor loading = .75). Participants in study 2 completed the entire 11-item scale. Items were summed to create subscales and total scales.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used in study 1 to characterize participants’ yoga experience and interest. Changes in interest pre- and posteducation were evaluated with χ2 comparison of distribution. The association of beliefs about yoga with 3 levels of interest (yes, no, maybe) was evaluated through analysis of variance (ANOVA) comparing the mean score on the summed BAYS items among the 3 groups. The association of demographic (age, education, race) and clinical factors (AJCC stage, physical function) with BAYS was determined through multivariate linear regression.

For analytic purposes, due to small subgroup sample sizes we compared those who identified as non-Hispanic White adults to those who identified as African American/Hispanic/other persons. To further evaluate the relationship of age to yoga beliefs, we examined beliefs about yoga in 3 age groups (40-59 years [n = 24]; 60-69 years [n = 58]; 70-89 years [n = 28]) using ANOVA comparing the mean score on the summed BAYS items among the 3 groups. In study 2, changes in interest before and after the yoga program were evaluated with paired t tests and repeated ANOVA, with beliefs about yoga prior to class as a covariate. The association of demographic and clinical factors with BAYS was determined as in the first sample through multivariate linear regression, except the variable of race was not included due to small sample size (ie, only 3 individuals identified as persons of color).

Thematic analysis in which content-related codes were developed and subsequently grouped together was applied to the data of 110 participants who responded to the open-ended survey questions in study 1 to further illuminate responses to closed-ended questions.35 Transcribed responses to the open-ended questions were transferred to a spreadsheet. An initial code book with code names, definitions, and examples was developed based on an inductive method by one team member (EA).35 Initially, coding and tabulation were conducted separately for each question but it was noted that content extended across response prompts (eg, responses to question 2 “What might make you more likely to come?” were spontaneously provided when answering question 1), thus coding was collapsed across questions. Next, 2 team members (EA, KD) coded the same responses, meeting weekly to discuss discrepancies. The code book was revised following each meeting to reflect refinements in code names and definitions, adding newly generated codes as needed. The process continued until consensus and data saturation was obtained, with 90% intercoder agreement. Next, these codes were subjected to thematic analysis by 2 team members (EA, KD) combining codes into 6 overarching themes. The entire team reviewed the codes and identified 2 supra themes: positive beliefs or facilitators and negative beliefs or barriers.

Consistent with the concept of reflexivity in qualitative research, we acknowledge the influence of the research team members on the qualitative process.36 The primary coding team (EA, KD) are both researchers and employees of Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System who have participated in other research projects involving veterans and qualitative analyses but are not yoga instructors or yoga researchers.

Results

Study 1

The sample of 110 military veterans was mostly male (99.1%) with a mean (SD) age of 64.9 (9.4) years (range, 41-88)(Table 1). The majority (70.9%) described their race/ethnicity as White, non-Hispanic followed by Black/African American (18.2%) and Hispanic (8.2%) persons; 50.0% had no more than a high school education. The most common cancer diagnoses were colorectal (50.9%), head and neck (39.1%), and esophageal and gastric (10.0%) and ranged from AJCC stages I to IV.

When first asked, the majority of participants (78.2%) reported that they were not interested in yoga, 16.4% reported they might be interested, and 5.5% reported they had tried a yoga class since their cancer diagnosis. In contrast, 40.9% used exercise, 32.7% used meditation, 14.5% used physical or occupational therapy, and 11.8% used massage therapy since their cancer diagnosis.

After participants were provided the brief scripted education about yoga, the level of interest shifted: 46.4% not interested, 21.8% interested, and 31.8% definitely interested, demonstrating a statistically significant shift in interest following education (χ2 = 22.25, P < .001) (Figure 1). Those with the most positive beliefs about yoga were most likely to indicate interest. Using the BAYS 3-item survey, the mean (SD) for the definitely interested, might be interested, and not interested groups was 15.1 (3.2), 14.1 (3.2), and 12.3 (2.5), respectively (F = 10.63, P < .001).

A multivariable regression was run to examine possible associations between participants’ demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and beliefs about yoga as measured by the 3 BAYS items (Table 2). Higher expected health benefits of yoga was associated with identifying as

Six themes were identified in qualitative analysis of semistructured interviews reflecting older veterans’ beliefs about yoga, which were grouped into the following suprathemes of positive vs negative beliefs (Figure 2). Exemplar responses appear in Table 3.

Study 2 Intervention Sample

This sample of 28 veterans was mostly male (96.4%) with a mean (SD) age of 69.2 (10.9) years (range, 57-87). The majority (89.3%) described their race as White, followed by Black/African American (10.7%); no participants self-identified in other categories for race/ethnicity. Twelve veterans (42.9%) had no more than a high school education. The most common cancer diagnosis was genitourinary (35.7%) and the AJCC stage ranged from I to IV.

We employed information learned in study 1 to enhance access in study 2. We mailed letters to 278 veterans diagnosed with cancer in the previous 3 years that provided education about yoga based on study 1 findings. Of 207 veterans reached by phone, 133 (64%) stated they were not interested in coming to a yoga class; 74 (36%) were interested, but 30 felt they were unable to attend due to obstacles such as illness or travel. Ultimately 37 (18%) veterans agreed and consented to the class, and 28 (14%) completed postclass surveys.

In multivariate regression, higher expected health benefits of yoga were associated with higher physical function, lower concern about expected discomfort was also associated with higher physical function as well as higher education; similarly, lower concern about expected social norms was associated with higher physical function. Age was not associated with any of the BAYS factors.

Beliefs about yoga improved from before to after class for all 3 domains with greater expected benefit and lower concerns about discomfort or social norms:

Discussion

Yoga is an effective clinical intervention for addressing some long-term adverse effects in cancer survivors, although the body of research focuses predominantly on middle aged, female, White, college-educated breast cancer survivors. There is no evidence to suggest yoga would be less effective in other groups, but it has not been extensively studied in survivors from diverse subgroups. Beliefs about yoga are a factor that may enhance interest in yoga interventions and research, and measures aimed at addressing potential beliefs and fears may capture information that can be used to support older cancer survivors in holistic health. The aims of this study were to examine beliefs about yoga in 2 samples of older cancer survivors who received VHA care. The main findings are (1) interest in yoga was initially low and lower than that of other complementary or exercise-based interventions, but increased when participants were provided brief education about yoga; (2) interest in yoga was associated with beliefs about yoga with qualitative comments illuminating these beliefs; (3) demographic characteristics (education, race) and physical function were associated with beliefs about yoga; and (4) positive beliefs about yoga increased following a brief yoga intervention and was associated with improvements in physical function.

Willingness to consider a class appeared to shift for some older veterans when they were presented brief information about yoga that explained what is involved, how it might help, and that it could be done from a chair if needed. These findings clearly indicated that when trying to enhance participation in yoga in clinical or research programs, it will be important that recruitment materials provide such information. This finding is consistent with the qualitative findings that reflected a lack of knowledge or skepticism about benefits of yoga among some participants. Given the finding that physical function was associated with beliefs about yoga and was also a prominent theme in qualitative analyses,

Age was not associated with beliefs about yoga in either study. Importantly, in a more detailed study 1 follow-up analysis, beliefs about yoga were equivalent for aged > 70 years compared with those aged 40 to 69 years. It is not entirely clear why older adults have been underrepresented in studies of yoga in cancer survivors. However, older adults are vastly underrepresented in clinical trials for many health conditions, even though they are more likely to experience many diseases, including cancer.37 A new National Institutes of Health policy requires that individuals of all ages, including older adults, must be included in all human subjects research unless there are scientific reasons not to include them.38 It is therefore imperative to consider strategies to address underrepresentation of older adults.

Qualitative findings here suggest it will be important to consider logistical barriers including transportation and affordability as well as adaptations requested by older adults (eg, preferences for older teachers).18

Although our sample was small, we also found that adults from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds had more positive beliefs about yoga, such that this finding should be interpreted with caution. Similar to older adults, individuals from diverse racial and ethnic groups are also underrepresented in clinical trials and may have lower access to complementary treatments. Cultural and linguistic adaptations and building community partnerships should be considered in both recruitment and intervention delivery strategies.40We learned that education about yoga may increase interest and that it is possible to recruit older veterans to yoga class. Nevertheless, in study 2, our rate of full participation was low, with only about 1 in 10 participating. Additional efforts to enhance beliefs about yoga and to addresslogistical barriers (offering telehealth yoga) are needed to best reach older veterans.

Limitations

These findings have several limitations. First, participants were homogeneous in age, gender, race/ethnicity and veteran status, which provides a window into this understudied population but limits generalizability and our ability to control across populations. Second, the sample size limited the ability to conduct subgroup and interaction analyses, such as examining potential differential effects of cancer type, treatment, and PTSD on yoga beliefs or to consider the relationship of yoga beliefs with changes in quality of life before and after the yoga intervention in study 2. Additionally, age was not associated with beliefs about yoga in these samples that of mostly older adults. We were able to compare middle-aged and older adults but could not compare beliefs about yoga to adults aged in their 20s and 30s. Last, our study excluded people with dementia and psychotic disorders. Further research is needed to examine yoga for older cancer survivors who have these conditions.

Conclusions

Education that specifically informs potential participants about yoga practice, potential modifications, and potential benefits, as well as adaptations to programs that address physical and logistical barriers may be useful in increasing access to and participation in yoga for older Veterans who are cancer survivors.

Acknowledgments/Funding

The authors have no financial or personal relationships to disclose. This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Rehabilitation Research and Development Service. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Boston Healthcare System, Bedford VA Medical Center, and Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas. We thank the members of the Veterans Cancer Rehabilitation Study (Vetcares) Research teams in Boston and in Houston and the veterans who have participated in our research studies and allow us to contribute to their health care.

1. Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Janelsins M, et al. Multicenter, randomized controlled trial of yoga for sleep quality among cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(26):3233-3241. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.7707

2. Chandwani KD, Thornton B, Perkins GH, et al. Yoga improves quality of life and benefit finding in women undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2010;8(2):43-55.

3. Erratum: Primary follicular lymphoma of disguised as multiple miliary like lesions: A case report and review of literature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2018;61(4):643. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.243009

4. Eyigor S, Uslu R, Apaydın S, Caramat I, Yesil H. Can yoga have any effect on shoulder and arm pain and quality of life in patients with breast cancer? A randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;32:40-45. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.04.010

5. Loudon A, Barnett T, Piller N, Immink MA, Williams AD. Yoga management of breast cancer-related lymphoedema: a randomised controlled pilot-trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:214. Published 2014 Jul 1. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-14-214

6. Browning KK, Kue J, Lyons F, Overcash J. Feasibility of mind-body movement programs for cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44(4):446-456. doi:10.1188/17.ONF.446-456

7. Rosenbaum MS, Velde J. The effects of yoga, massage, and reiki on patient well-being at a cancer resource center. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20(3):E77-E81. doi:10.1188/16.CJON.E77-E81

8. Yun H, Sun L, Mao JJ. Growth of integrative medicine at leading cancer centers between 2009 and 2016: a systematic analysis of NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center websites. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2017;2017(52):lgx004. doi:10.1093/jncimonographs/lgx004

9. Sanft T, Denlinger CS, Armenian S, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: survivorship, version 2.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(7):784-794. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2019.0034

10. Lyman GH, Greenlee H, Bohlke K, et al. Integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment: ASCO endorsement of the SIO clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(25):2647-2655. doi:10.1200/JCO.2018.79.2721

11. Culos-Reed SN, Mackenzie MJ, Sohl SJ, Jesse MT, Zahavich AN, Danhauer SC. Yoga & cancer interventions: a review of the clinical significance of patient reported outcomes for cancer survivors. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:642576. doi:10.1155/2012/642576

12. Danhauer SC, Addington EL, Cohen L, et al. Yoga for symptom management in oncology: a review of the evidence base and future directions for research. Cancer. 2019;125(12):1979-1989. doi:10.1002/cncr.31979

13. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7-34. doi:10.3322/caac.21551

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans’ diseases associated with Agent Orange. Updated June 16, 2021. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/exposures/agentorange/conditions

15. Deimling GT, Arendt JA, Kypriotakis G, Bowman KF. Functioning of older, long-term cancer survivors: the role of cancer and comorbidities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(suppl 2):S289-S292. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02515.x

16. King K, Gosian J, Doherty K, et al. Implementing yoga therapy adapted for older veterans who are cancer survivors. Int J Yoga Therap. 2014;24:87-96.

17. Wertman A, Wister AV, Mitchell BA. On and off the mat: yoga experiences of middle-aged and older adults. Can J Aging. 2016;35(2):190-205. doi:10.1017/S0714980816000155

18. Chen KM, Wang HH, Li CH, Chen MH. Community vs. institutional elders’ evaluations of and preferences for yoga exercises. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(7-8):1000-1007. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03337.x

19. Saravanakumar P, Higgins IJ, Van Der Riet PJ, Sibbritt D. Tai chi and yoga in residential aged care: perspectives of participants: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(23-24):4390-4399. doi:10.1111/jocn.14590

20. Fan JT, Chen KM. Using silver yoga exercises to promote physical and mental health of elders with dementia in long-term care facilities. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(8):1222-1230. doi:10.1017/S1041610211000287

21. Taylor TR, Barrow J, Makambi K, et al. A restorative yoga intervention for African-American breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):62-72. doi:10.1007/s40615-017-0342-4

22. Moadel AB, Shah C, Wylie-Rosett J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of yoga among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: effects on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(28):4387-4395. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6027

23. Smith SA, Whitehead MS, Sheats JQ, Chubb B, Alema-Mensah E, Ansa BE. Community engagement to address socio-ecological barriers to physical activity among African American breast cancer survivors. J Ga Public Health Assoc. 2017;6(3):393-397. doi:10.21633/jgpha.6.312

24. Cushing RE, Braun KL, Alden C-Iayt SW, Katz AR. Military-Tailored Yoga for Veterans with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Mil Med. 2018;183(5-6):e223-e231. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx071

25. Davis LW, Schmid AA, Daggy JK, et al. Symptoms improve after a yoga program designed for PTSD in a randomized controlled trial with veterans and civilians. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(8):904-912. doi:10.1037/tra0000564

26. Chopin SM, Sheerin CM, Meyer BL. Yoga for warriors: An intervention for veterans with comorbid chronic pain and PTSD. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(8):888-896. doi:10.1037/tra0000649

27. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Whole health. Updated September 13, 2021. Accessed September 22, 2021. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth

28. Sohl SJ, Schnur JB, Daly L, Suslov K, Montgomery GH. Development of the beliefs about yoga scale. Int J Yoga Therap. 2011;(21):85-91.

29. Cadmus-Bertram L, Littman AJ, Ulrich CM, et al. Predictors of adherence to a 26-week viniyoga intervention among post-treatment breast cancer survivors. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(9):751-758. doi:10.1089/acm.2012.0118

30. Mackenzie MJ, Carlson LE, Ekkekakis P, Paskevich DM, Culos-Reed SN. Affect and mindfulness as predictors of change in mood disturbance, stress symptoms, and quality of life in a community-based yoga program for cancer survivors. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:419496. doi:10.1155/2013/419496