User login

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder-Associated Cognitive Deficits on the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status in a Veteran Population

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) affects about 10 to 25% of veterans in the US and is associated with reductions in quality of life and poor occupational functioning.1,2 PTSD is often associated with multiple cognitive deficits that play a role in a number of clinical symptoms and impair cognition beyond what can be solely attributed to the effects of physical or psychological trauma.3-5 Although the literature on the pattern and magnitude of cognitive deficits associated with PTSD is mixed, dysfunction in attention, verbal memory, speed of information processing, working memory, and executive functioning are the most consistent findings.6-11Verbal memory and attention seem to be particularly negatively impacted by PTSD and especially so in combat-exposed war veterans.7,12 Verbal memory difficulties in returning war veterans also may mediate quality of life and be particularly disruptive to everyday functioning.13 Further, evidence exists that a diagnosis of PTSD is associated with increased risk for dementia and deficits in episodic memory in older adults.14,15

The PTSD-associated cognitive deficits are routinely assessed through neuropsychological measures within the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA). The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) is a commonly used cognitive screening measure in medical settings, and prior research has reinforced its clinical utility across a variety of populations, including Alzheimer disease, schizophrenia, Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, stroke, and traumatic brain injury (TBI).16-24

McKay and colleagues previously examined the use of the RBANS within a sample of individuals who had a history of moderate-to-severe TBIs, with findings suggesting the RBANS is a valid and reliable screening measure in this population.25However, McKay and colleagues used a carefully defined sample in a cognitive neurorehabilitation setting, many of whom experienced a TBI significant enough to require ongoing medical monitoring, attendant care, or substantial support services.

The influence of PTSD-associated cognitive deficits on the RBANS performance is unclear, and which subtests of the measure, if any, are differentially impacted in individuals with and those without a diagnosis of PTSD is uncertain. Further, less is known about the influence of PTSD in outpatient clinical settings when PTSD and TBI are not necessarily the primary presenting problem. The purpose of the current study was to determine the influence of a PTSD diagnosis on performance on the RBANS in an outpatient VA setting.

Methods

Participants included 153 veterans who were 90% male with a mean (SD) age of 46.8 (11.3) years and a mean (SD) education of 14.2 (2.3) years from a catchment area ranging from Montana south through western Texas, and all states west of that line, sequentially evaluated as part of a clinic workup at the California War Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC-CA). WRIISC-CA is a second-level evaluation clinic under patient primary care in the VA system dedicated to providing comprehensive medical evaluations on postdeployment veterans with complex medical concerns, including possible TBI and PTSD. Participants included 23 Vietnam-era, 72 Operation Desert Storm/Desert Shield-era, and 58 Operation Iraqi Freedom/Enduring Freedom-era veterans. We have previously published a more thorough analysis of medical characteristics for a WRIISC-CA sample.26

A Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM IV) diagnosis of current PTSD was determined by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-IV), as administered or supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist during the course of the larger medical evaluation.27 Given the co-occurring nature of TBI and PTSD and their complicated relationship with regard to cognitive functioning, all veterans also underwent a comprehensive examination by a board-certified neurologist to assess for a possible history of TBI, based on the presence of at least 1 past event according to the guidelines recommended by the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine.28,29Veterans were categorized as having a history of no TBI, mild TBI, or moderate TBI. No veterans met criteria for history of severe TBI.Veterans were excluded from the analysis if unable to complete the mental health, neurological, or cognitive evaluations. Informed consent was obtained consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional guidelines established by the VA Palo Alto Human Subjects Review Committee. The study was approved by the VA Palo Alto and Stanford School of Medicine institutional review boards.

Cognitive Measures

All veterans completed a targeted cognitive battery that included the following: a reading recognition measure designed to estimate premorbid intellectual functioning (Wechsler Test of Adult Reading [WTAR]); a measure assessing auditory attention and working memory ability (Wechsler Adults Intelligence Scale-IV [WAIS-IV] Digit Span subtest); a measure assessing processing speed, attention, and cognitive flexibility (Trails A and B); and the RBANS.16,30-32The focus of the current study was on the RBANS, a brief cognitive screening measure that contains 12 subtests examining a variety of cognitive functions. Given that all participants were veterans receiving outpatient services, there was no nonpatient control group for comparison. To address this, all raw data were converted to standardized scores based on healthy normative data provided within the test manual. Specifically, the 12 RBANS subtest scores were converted to age-corrected standardized z scores, which in turn created a total summary score and 5 composite summary indexes: immediate memory, visuospatial/constructional, attention, language, and delayed memory. All veterans completed the Form A version of the measure.

Statistical Analyses

Group level differences on selective demographic and cognitive measures between veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD and those without were examined using t tests. Cognitive variables included standardized scores for the RBANS, including age-adjusted total summary score, index scores, and subtest scores.16 Estimated full-scale IQ and standardized summary scores from the WTAR, demographically adjusted standardized scores for the total time to complete Trails A and time to complete Trails B, and age-adjusted standardized scores for the WAIS-IV Digit Span subtest (forward, backward, and sequencing trials, as well as the summary total score) were examined for group differences.30,31,33 To further examine the association between PTSD and RBANS performance, multivariate multiple regressions were conducted using measures of episodic memory and processing speed from the RBANS (ie, story tasks, list learning tasks, and coding subtests). These specific measures were selected ad hoc based on extant literature.6,10The dependent variable for each analysis was the standardized score from the selected subtest; PTSD status, a diagnosis of TBI, a diagnosis of co-occurring TBI and PTSD, gender, and years of education were predictor variables.

Results

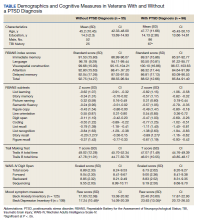

Of the 153 study participants, 98 (64%) met DSM-4 criteria for current PTSD, whereas 55 (36%) did not (Table). There was no group statistical difference between veterans with or without a diagnosis of PTSD for age, education, or gender (P < .05). A diagnosis of PTSD tended to be more frequent in participants with a history of head injury (χ2 = 7.72; P < .05). Veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD performed significantly worse on the RBANS Story Recall subtest compared with the results of those without PTSD (t[138] = 3.10; P < .01); performance on other cognitive measures was not significantly different between the PTSD groups. A diagnosis of PTSD was also significantly associated with self-reported depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory-II; t[123] = -2.81; P < .01). Depressive symptoms were not associated with a history of TBI, and group differences were not significant.

Given the high co-occurrence of PTSD and TBI (68%) in our PTSD sample, secondary analyses examined the association of select diagnoses with performance on the RBANS, specifically veterans with a historical diagnosis of TBI (n = 92) from those without a diagnosis of TBI (n = 61), as well as those with co-occurring PTSD and TBI (n = 71) from those without (n = 82). The majority of the sample met criteria for a history of mild TBI (n = 79) when compared with moderate TBI (n = 13); none met criteria for a past history of severe TBI. PTSD status (β = .63, P = .04) and years of education (β = .16, P < .01) were associated with performance on the RBANS Story Recall subtest (R2= .23, F[5,139] = 8.11, P < .01). Education was the only significant predictor for the rest of the multivariate multiple regressions (all P < .05). A diagnosis of TBI or co-occurring PTSD and TBI was not significantly associated with performance on the Story Memory, Story Recall, List Learning, List Recall, or Coding subtests. multivariate analysis of variance tests for the hypothesis of an overall main effect of PTSD (F(5,130) = 1.08, P = .34), TBI (F[5,130] = .91, P = .48), or PTSD+TBI (F[5,130] =.47, P = .80) on the 4 selected tests were not significant.

Discussion

The findings of the present study suggest that veterans with PTSD perform worse on specific RBANS subtests compared with veterans without PTSD. Specifically, worse performance on the Story Recall subtest of the RBANS memory index was a significant predictor of a diagnosis of PTSD within the statistical model. This association with PTSD was not seen in other demographic (excluding education) or cognitive measures, including other memory tasks, such as List Recall and Figure Recall, and attentional measures, such as WAIS-IV Digit Span, and the Trail Making Test. Overall RBANS index scores were not significantly different between groups, though this is not surprising given that recent research suggests the RBANS composite scores have questionable validity and reliability.34

The finding that a measure of episodic memory is most influenced by PTSD status is consistent with prior research.35 However, there are several possible reasons why Story Recall in particular showed the greatest association, even more than other episodic memory measures. A review by Isaac and colleagues found a diagnosis of PTSD correlated with frontal lobe-associated memory deficits.6 As Story Recall provides only 2 rehearsal trials compared with the 4 trials provided in the RBANS List Learning subtest, it is possible that Story Recall relies more on attentional processes than on learning with repetition.

Research has indicated attention and verbal episodic memory dysfunction are associated with a diagnosis of PTSD in combat veterans, and individuals with a diagnosis of PTSD show deficits in executive functioning, including attention difficulties beyond what is seen in trauma-exposed controls.4,7,8,11,35Furthermore, a diagnosis of PTSD has been shown to be associated with impaired performance on the Logical Memory subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised, a very similar measure to the RBANS Story Recall.36

The present finding that performance on a RBANS subtest was associated with a diagnosis of PTSD but not a history of TBI is not surprising. The majority of the present sample who reported a history of TBI met criteria for a remote head injury of mild severity (86%). Cognitive symptoms related to mild TBI are thought to generally resolve over time, and recent research suggests that PTSD symptoms may account for a substantial portion of reported postconcussive symptoms.37,38Similarly, recent research suggests a diagnosis of mild TBI does not necessarily result in additive cognitive impairment in combat veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD, and that a diagnosis of PTSD is more strongly associated with cognitive symptoms than is mild TBI.5,39,40

The lack of association with RBANS performance and co-occurring PTSD and TBI is less clear. Although both conditions are heterogenous, it may be that individuals with a diagnosis solely of PTSD are quantitively different from those with a concurrent diagnosis of PTSD and TBI (ie, PTSD presumed due to a mild TBI). Specifically, the impact of PTSD on cognition may be related to symptom severity and indexed trauma. A published systematic review on the PTSD-related cognitive impairment showed a medium-to-strong effect size for severity of PTSD symptoms on cognitive performance, with war trauma showing the strongest effect.4In particular, individuals who experience repeated or complex trauma are prone to experience PTSD symptoms with concurrent cognitive deficits, again suggesting the possibility of qualitative differences between outpatient veterans with PTSD and those with mild TBI associated PTSD.41While disentangling PTSD and mild TBI symptoms are notoriously difficult, future research aiming to examine these factors may be beneficial in the ability to draw larger conclusions on the relationship between cognition and PTSD.

Limitations

Several limitations may affect the generalizability of the findings. The present study used a veteran sample referred to a specialty clinic for complicated postdeployment health concerns. Although findings may not be representative of an inpatient population or clinics that focus solely on TBI, they may more adequately reflect veterans using clinical services at VA medical centers. We also did not include measures of PTSD symptom severity (eg, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist), instead using diagnosis based on the gold standard CAPS. In addition, the likelihood of the presence of a remote TBI was based on a clinical interview with a neurologist and not on acute neurologic findings. TBI is a heterogenous diagnosis, with multiple factors that likely influence cognitive performance, including location of the injury, type of injury, and time since injury, which may be lost during group analysis. Further, the RBANS is not intended to serve as a method for a differential diagnosis of PTSD or TBI. Concordant with this, the intention of the current study was to capture the quality of cognitive function on the RBANS within individuals with PTSD.

Conslusions

The ability for veterans to remember a short story following a delay (ie, RBANS Story Recall subtest) was negatively associated with a diagnosis of PTSD. Further, the RBANS best captured cognitive deficits associated with PTSD compared with those with a history of mild TBI, or co-occurring mild TBI and PTSD. These findings may provide insight into the interpretation and attribution of cognitive deficits in the veteran population and holds potential to guide future research examining focused cognitive phenotypes to provide precision targets in individual treatment.

1. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048-1060. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012

2. Schnurr PP, Lunney CA, Bovin MJ, Marx BP. Posttraumatic stress disorder and quality of life: extension of findings to veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):727-735. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.006

3. McNally RJ. Cognitive abnormalities in post-traumatic stress disorder. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10(6):271-277. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.04.007

4. Qureshi SU, Long ME, Bradshaw MR, et al. Does PTSD impair cognition beyond the effect of trauma? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(1):16-28. doi:10.1176/jnp.23.1.jnp16

5. Gordon SN, Fitzpatrick PJ, Hilsabeck RC. No effect of PTSD and other psychiatric disorders on cognitive functioning in veterans with mild TBI. Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;25(3):337-347. doi:10.1080/13854046.2010.550634

6. Isaac CL, Cushway D, Jones GV. Is posttraumatic stress disorder associated with specific deficits in episodic memory? Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(8):939-955. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.004

7. Johnsen GE, Asbjornsen AE. Consistent impaired verbal memory in PTSD: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2008;111(1):74-82. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.02.007

8. Polak AR, Witteveen AB, Reitsma JB, Olff M. The role of executive function in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(1):11-21. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.001

9. Scott JC, Matt GE, Wrocklage KM, et al. A quantitative meta-analysis of neurocognitive functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(1):105-140.

10. Vasterling JJ, Duke LM, Brailey K, Constans JI, Allain AN Jr, Sutker PB. Attention, learning, and memory performances and intellectual resources in Vietnam veterans: PTSD and no disorder comparisons. Neuropsychology. 2002;16(1):5-14. doi:10.1037//0894-4105.16.1.5

11. Wrocklage KM, Schweinsburg BC, Krystal JH, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: associations with performance validity, comorbidities, and functional outcomes. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2016;19:1-13. doi:10.1017/S1355617716000059

12. Yehuda R, Keefe RS, Harvey PD, et al. Learning and memory in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(1):137-139. doi:10.1176/ajp.152.1.137

13. Martindale SL, Morissette SB, Kimbrel NA, et al. Neuropsychological functioning, coping, and quality of life among returning war veterans. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61(3):231-239. doi:10.1037/rep0000076

14. Mackin SR, Lesselyong JA, Yaffe K. Pattern of cognitive impairment in older veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder evaluated at a memory disorders clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(6):637-642. doi:10.1002/gps.2763

15. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.61

16. Randolph C. RBANS Manual: Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. Psychological Corporation; 1998.

17. Duff K, Humphreys Clark JD, O'Bryant SE, Mold JW, Schiffer RB, Sutker PB. Utility of the RBANS in detecting cognitive impairment associated with Alzheimer's disease: sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive powers. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;23(5):603-612. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2008.06.004

18. Gold JM, Queern C, Iannone VN, Buchanan RW. Repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status as a screening test in schizophrenia I: sensitivity, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(12):1944-1950. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.12.1944

19. Beatty WW, Ryder KA, Gontkovsky ST, Scott JG, McSwan KL, Bharucha KJ. Analyzing the subcortical dementia syndrome of Parkinson's disease using the RBANS. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2003;18(5):509-520.

20. Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20(3):310-319. doi:10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823

21. Larson E, Kirschner K, Bode R, Heinemann A, Goodman R. Construct and predictive validity of the repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status in the evaluation of stroke patients. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2005;27(1):16-32. doi:10.1080/138033990513564

22. McKay C, Casey JE, Wertheimer J, Fichtenberg NL. Reliability and validity of the RBANS in a traumatic brain injured sample. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22(1):91-98. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2006.11.003

23. Lippa SM, Hawes S, Jokic E, Caroselli JS. Sensitivity of the RBANS to acute traumatic brain injury and length of post-traumatic amnesia. Brain Inj. 2013;27(6):689-695. doi:10.3109/02699052.2013.771793

24. Pachet AK. Construct validity of the Repeatable Battery of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) with acquired brain injury patients. Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;21(2):286-293. doi:10.1080/13854040500376823

25. McKay C, Wertheimer JC, Fichtenberg NL, Casey JE. The repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status (RBANS): clinical utility in a traumatic brain injury sample. Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;22(2):228-241. doi:10.1080/13854040701260370

26. Sheng T, Fairchild JK, Kong JY, et al. The influence of physical and mental health symptoms on Veterans’ functional health status. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(6):781-796. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2015.07.0146

27. Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, et al. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8(1):75-90. doi:10.1007/BF02105408

28. Mattson EK, Nelson NW, Sponheim SR, Disner SG. The impact of PTSD and mTBI on the relationship between subjective and objective cognitive deficits in combat-exposed veterans. Neuropsychology. Oct 2019;33(7):913-921. doi:10.1037/neu0000560

29. Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1993;8(3):86-87.

30. Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR). The Psychological Corporation; 2001.

31. Wechsler D. Wechsler Adults Intelligence Scale – Fourth Edition: Administration and Scoring Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2008.

32. Reitan R, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Therapy and Clinical Interpretation. Tuscon, AZ: Neuropsychological Press; 1985.

33. Heaton R, Miller S, Taylor M, Grant I. Revised Comprehensive Norms for an Expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically Ajdusted Neuropsychological Norms for African American and Caucasian Adults. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assesment Resources, Inc; 2004.

34. Vogt EM, Prichett GD, Hoelzle JB. Invariant two-component structure of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS). Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2017;24(1)50-64. doi:10.1080/23279095.2015.1088852

35. Gilbertson MW, Gurvits TV, Lasko NB, Orr SP, Pitman RK. Multivariate assessment of explicit memory function in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14(2):413-432. doi:10.1023/A:1011181305501

36. Bremner JD, Randall P, Scott TM, et al. Deficits in short-term memory in adult survivors of childhood abuse. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59(1-2):97-107. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(95)02800-5

37. Belanger HG, Curtiss G, Demery JA, Lebowitz BK, Vanderploeg RD. Factors moderating neuropsychological outcomes following mild traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005;11(3):215-227. doi:10.1017/S1355617705050277

38. Lippa SM, Pastorek NJ, Benge JF, Thornton GM. Postconcussive symptoms after blast and nonblast-related mild traumatic brain injuries in Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16(5):856-866. doi:10.1017/S1355617710000743

39. Soble JR, Spanierman LB, Fitzgerald Smith J. Neuropsychological functioning of combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder and mild traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2013;35(5):551-561. doi:10.1080/13803395.2013.798398

40. Vanderploeg RD, Belanger HG, Curtiss G. Mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder and their associations with health symptoms. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(7):1084-1093. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.023

41. Ainamani HE, Elbert T, Olema DK, Hecker T. PTSD symptom severity relates to cognitive and psycho-social dysfunctioning - a study with Congolese refugees in Uganda. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(1):1283086. doi:10.1080/20008198.2017.1283086

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) affects about 10 to 25% of veterans in the US and is associated with reductions in quality of life and poor occupational functioning.1,2 PTSD is often associated with multiple cognitive deficits that play a role in a number of clinical symptoms and impair cognition beyond what can be solely attributed to the effects of physical or psychological trauma.3-5 Although the literature on the pattern and magnitude of cognitive deficits associated with PTSD is mixed, dysfunction in attention, verbal memory, speed of information processing, working memory, and executive functioning are the most consistent findings.6-11Verbal memory and attention seem to be particularly negatively impacted by PTSD and especially so in combat-exposed war veterans.7,12 Verbal memory difficulties in returning war veterans also may mediate quality of life and be particularly disruptive to everyday functioning.13 Further, evidence exists that a diagnosis of PTSD is associated with increased risk for dementia and deficits in episodic memory in older adults.14,15

The PTSD-associated cognitive deficits are routinely assessed through neuropsychological measures within the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA). The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) is a commonly used cognitive screening measure in medical settings, and prior research has reinforced its clinical utility across a variety of populations, including Alzheimer disease, schizophrenia, Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, stroke, and traumatic brain injury (TBI).16-24

McKay and colleagues previously examined the use of the RBANS within a sample of individuals who had a history of moderate-to-severe TBIs, with findings suggesting the RBANS is a valid and reliable screening measure in this population.25However, McKay and colleagues used a carefully defined sample in a cognitive neurorehabilitation setting, many of whom experienced a TBI significant enough to require ongoing medical monitoring, attendant care, or substantial support services.

The influence of PTSD-associated cognitive deficits on the RBANS performance is unclear, and which subtests of the measure, if any, are differentially impacted in individuals with and those without a diagnosis of PTSD is uncertain. Further, less is known about the influence of PTSD in outpatient clinical settings when PTSD and TBI are not necessarily the primary presenting problem. The purpose of the current study was to determine the influence of a PTSD diagnosis on performance on the RBANS in an outpatient VA setting.

Methods

Participants included 153 veterans who were 90% male with a mean (SD) age of 46.8 (11.3) years and a mean (SD) education of 14.2 (2.3) years from a catchment area ranging from Montana south through western Texas, and all states west of that line, sequentially evaluated as part of a clinic workup at the California War Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC-CA). WRIISC-CA is a second-level evaluation clinic under patient primary care in the VA system dedicated to providing comprehensive medical evaluations on postdeployment veterans with complex medical concerns, including possible TBI and PTSD. Participants included 23 Vietnam-era, 72 Operation Desert Storm/Desert Shield-era, and 58 Operation Iraqi Freedom/Enduring Freedom-era veterans. We have previously published a more thorough analysis of medical characteristics for a WRIISC-CA sample.26

A Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM IV) diagnosis of current PTSD was determined by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-IV), as administered or supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist during the course of the larger medical evaluation.27 Given the co-occurring nature of TBI and PTSD and their complicated relationship with regard to cognitive functioning, all veterans also underwent a comprehensive examination by a board-certified neurologist to assess for a possible history of TBI, based on the presence of at least 1 past event according to the guidelines recommended by the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine.28,29Veterans were categorized as having a history of no TBI, mild TBI, or moderate TBI. No veterans met criteria for history of severe TBI.Veterans were excluded from the analysis if unable to complete the mental health, neurological, or cognitive evaluations. Informed consent was obtained consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional guidelines established by the VA Palo Alto Human Subjects Review Committee. The study was approved by the VA Palo Alto and Stanford School of Medicine institutional review boards.

Cognitive Measures

All veterans completed a targeted cognitive battery that included the following: a reading recognition measure designed to estimate premorbid intellectual functioning (Wechsler Test of Adult Reading [WTAR]); a measure assessing auditory attention and working memory ability (Wechsler Adults Intelligence Scale-IV [WAIS-IV] Digit Span subtest); a measure assessing processing speed, attention, and cognitive flexibility (Trails A and B); and the RBANS.16,30-32The focus of the current study was on the RBANS, a brief cognitive screening measure that contains 12 subtests examining a variety of cognitive functions. Given that all participants were veterans receiving outpatient services, there was no nonpatient control group for comparison. To address this, all raw data were converted to standardized scores based on healthy normative data provided within the test manual. Specifically, the 12 RBANS subtest scores were converted to age-corrected standardized z scores, which in turn created a total summary score and 5 composite summary indexes: immediate memory, visuospatial/constructional, attention, language, and delayed memory. All veterans completed the Form A version of the measure.

Statistical Analyses

Group level differences on selective demographic and cognitive measures between veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD and those without were examined using t tests. Cognitive variables included standardized scores for the RBANS, including age-adjusted total summary score, index scores, and subtest scores.16 Estimated full-scale IQ and standardized summary scores from the WTAR, demographically adjusted standardized scores for the total time to complete Trails A and time to complete Trails B, and age-adjusted standardized scores for the WAIS-IV Digit Span subtest (forward, backward, and sequencing trials, as well as the summary total score) were examined for group differences.30,31,33 To further examine the association between PTSD and RBANS performance, multivariate multiple regressions were conducted using measures of episodic memory and processing speed from the RBANS (ie, story tasks, list learning tasks, and coding subtests). These specific measures were selected ad hoc based on extant literature.6,10The dependent variable for each analysis was the standardized score from the selected subtest; PTSD status, a diagnosis of TBI, a diagnosis of co-occurring TBI and PTSD, gender, and years of education were predictor variables.

Results

Of the 153 study participants, 98 (64%) met DSM-4 criteria for current PTSD, whereas 55 (36%) did not (Table). There was no group statistical difference between veterans with or without a diagnosis of PTSD for age, education, or gender (P < .05). A diagnosis of PTSD tended to be more frequent in participants with a history of head injury (χ2 = 7.72; P < .05). Veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD performed significantly worse on the RBANS Story Recall subtest compared with the results of those without PTSD (t[138] = 3.10; P < .01); performance on other cognitive measures was not significantly different between the PTSD groups. A diagnosis of PTSD was also significantly associated with self-reported depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory-II; t[123] = -2.81; P < .01). Depressive symptoms were not associated with a history of TBI, and group differences were not significant.

Given the high co-occurrence of PTSD and TBI (68%) in our PTSD sample, secondary analyses examined the association of select diagnoses with performance on the RBANS, specifically veterans with a historical diagnosis of TBI (n = 92) from those without a diagnosis of TBI (n = 61), as well as those with co-occurring PTSD and TBI (n = 71) from those without (n = 82). The majority of the sample met criteria for a history of mild TBI (n = 79) when compared with moderate TBI (n = 13); none met criteria for a past history of severe TBI. PTSD status (β = .63, P = .04) and years of education (β = .16, P < .01) were associated with performance on the RBANS Story Recall subtest (R2= .23, F[5,139] = 8.11, P < .01). Education was the only significant predictor for the rest of the multivariate multiple regressions (all P < .05). A diagnosis of TBI or co-occurring PTSD and TBI was not significantly associated with performance on the Story Memory, Story Recall, List Learning, List Recall, or Coding subtests. multivariate analysis of variance tests for the hypothesis of an overall main effect of PTSD (F(5,130) = 1.08, P = .34), TBI (F[5,130] = .91, P = .48), or PTSD+TBI (F[5,130] =.47, P = .80) on the 4 selected tests were not significant.

Discussion

The findings of the present study suggest that veterans with PTSD perform worse on specific RBANS subtests compared with veterans without PTSD. Specifically, worse performance on the Story Recall subtest of the RBANS memory index was a significant predictor of a diagnosis of PTSD within the statistical model. This association with PTSD was not seen in other demographic (excluding education) or cognitive measures, including other memory tasks, such as List Recall and Figure Recall, and attentional measures, such as WAIS-IV Digit Span, and the Trail Making Test. Overall RBANS index scores were not significantly different between groups, though this is not surprising given that recent research suggests the RBANS composite scores have questionable validity and reliability.34

The finding that a measure of episodic memory is most influenced by PTSD status is consistent with prior research.35 However, there are several possible reasons why Story Recall in particular showed the greatest association, even more than other episodic memory measures. A review by Isaac and colleagues found a diagnosis of PTSD correlated with frontal lobe-associated memory deficits.6 As Story Recall provides only 2 rehearsal trials compared with the 4 trials provided in the RBANS List Learning subtest, it is possible that Story Recall relies more on attentional processes than on learning with repetition.

Research has indicated attention and verbal episodic memory dysfunction are associated with a diagnosis of PTSD in combat veterans, and individuals with a diagnosis of PTSD show deficits in executive functioning, including attention difficulties beyond what is seen in trauma-exposed controls.4,7,8,11,35Furthermore, a diagnosis of PTSD has been shown to be associated with impaired performance on the Logical Memory subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised, a very similar measure to the RBANS Story Recall.36

The present finding that performance on a RBANS subtest was associated with a diagnosis of PTSD but not a history of TBI is not surprising. The majority of the present sample who reported a history of TBI met criteria for a remote head injury of mild severity (86%). Cognitive symptoms related to mild TBI are thought to generally resolve over time, and recent research suggests that PTSD symptoms may account for a substantial portion of reported postconcussive symptoms.37,38Similarly, recent research suggests a diagnosis of mild TBI does not necessarily result in additive cognitive impairment in combat veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD, and that a diagnosis of PTSD is more strongly associated with cognitive symptoms than is mild TBI.5,39,40

The lack of association with RBANS performance and co-occurring PTSD and TBI is less clear. Although both conditions are heterogenous, it may be that individuals with a diagnosis solely of PTSD are quantitively different from those with a concurrent diagnosis of PTSD and TBI (ie, PTSD presumed due to a mild TBI). Specifically, the impact of PTSD on cognition may be related to symptom severity and indexed trauma. A published systematic review on the PTSD-related cognitive impairment showed a medium-to-strong effect size for severity of PTSD symptoms on cognitive performance, with war trauma showing the strongest effect.4In particular, individuals who experience repeated or complex trauma are prone to experience PTSD symptoms with concurrent cognitive deficits, again suggesting the possibility of qualitative differences between outpatient veterans with PTSD and those with mild TBI associated PTSD.41While disentangling PTSD and mild TBI symptoms are notoriously difficult, future research aiming to examine these factors may be beneficial in the ability to draw larger conclusions on the relationship between cognition and PTSD.

Limitations

Several limitations may affect the generalizability of the findings. The present study used a veteran sample referred to a specialty clinic for complicated postdeployment health concerns. Although findings may not be representative of an inpatient population or clinics that focus solely on TBI, they may more adequately reflect veterans using clinical services at VA medical centers. We also did not include measures of PTSD symptom severity (eg, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist), instead using diagnosis based on the gold standard CAPS. In addition, the likelihood of the presence of a remote TBI was based on a clinical interview with a neurologist and not on acute neurologic findings. TBI is a heterogenous diagnosis, with multiple factors that likely influence cognitive performance, including location of the injury, type of injury, and time since injury, which may be lost during group analysis. Further, the RBANS is not intended to serve as a method for a differential diagnosis of PTSD or TBI. Concordant with this, the intention of the current study was to capture the quality of cognitive function on the RBANS within individuals with PTSD.

Conslusions

The ability for veterans to remember a short story following a delay (ie, RBANS Story Recall subtest) was negatively associated with a diagnosis of PTSD. Further, the RBANS best captured cognitive deficits associated with PTSD compared with those with a history of mild TBI, or co-occurring mild TBI and PTSD. These findings may provide insight into the interpretation and attribution of cognitive deficits in the veteran population and holds potential to guide future research examining focused cognitive phenotypes to provide precision targets in individual treatment.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) affects about 10 to 25% of veterans in the US and is associated with reductions in quality of life and poor occupational functioning.1,2 PTSD is often associated with multiple cognitive deficits that play a role in a number of clinical symptoms and impair cognition beyond what can be solely attributed to the effects of physical or psychological trauma.3-5 Although the literature on the pattern and magnitude of cognitive deficits associated with PTSD is mixed, dysfunction in attention, verbal memory, speed of information processing, working memory, and executive functioning are the most consistent findings.6-11Verbal memory and attention seem to be particularly negatively impacted by PTSD and especially so in combat-exposed war veterans.7,12 Verbal memory difficulties in returning war veterans also may mediate quality of life and be particularly disruptive to everyday functioning.13 Further, evidence exists that a diagnosis of PTSD is associated with increased risk for dementia and deficits in episodic memory in older adults.14,15

The PTSD-associated cognitive deficits are routinely assessed through neuropsychological measures within the US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA). The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) is a commonly used cognitive screening measure in medical settings, and prior research has reinforced its clinical utility across a variety of populations, including Alzheimer disease, schizophrenia, Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, stroke, and traumatic brain injury (TBI).16-24

McKay and colleagues previously examined the use of the RBANS within a sample of individuals who had a history of moderate-to-severe TBIs, with findings suggesting the RBANS is a valid and reliable screening measure in this population.25However, McKay and colleagues used a carefully defined sample in a cognitive neurorehabilitation setting, many of whom experienced a TBI significant enough to require ongoing medical monitoring, attendant care, or substantial support services.

The influence of PTSD-associated cognitive deficits on the RBANS performance is unclear, and which subtests of the measure, if any, are differentially impacted in individuals with and those without a diagnosis of PTSD is uncertain. Further, less is known about the influence of PTSD in outpatient clinical settings when PTSD and TBI are not necessarily the primary presenting problem. The purpose of the current study was to determine the influence of a PTSD diagnosis on performance on the RBANS in an outpatient VA setting.

Methods

Participants included 153 veterans who were 90% male with a mean (SD) age of 46.8 (11.3) years and a mean (SD) education of 14.2 (2.3) years from a catchment area ranging from Montana south through western Texas, and all states west of that line, sequentially evaluated as part of a clinic workup at the California War Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC-CA). WRIISC-CA is a second-level evaluation clinic under patient primary care in the VA system dedicated to providing comprehensive medical evaluations on postdeployment veterans with complex medical concerns, including possible TBI and PTSD. Participants included 23 Vietnam-era, 72 Operation Desert Storm/Desert Shield-era, and 58 Operation Iraqi Freedom/Enduring Freedom-era veterans. We have previously published a more thorough analysis of medical characteristics for a WRIISC-CA sample.26

A Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM IV) diagnosis of current PTSD was determined by the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-IV), as administered or supervised by a licensed clinical psychologist during the course of the larger medical evaluation.27 Given the co-occurring nature of TBI and PTSD and their complicated relationship with regard to cognitive functioning, all veterans also underwent a comprehensive examination by a board-certified neurologist to assess for a possible history of TBI, based on the presence of at least 1 past event according to the guidelines recommended by the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine.28,29Veterans were categorized as having a history of no TBI, mild TBI, or moderate TBI. No veterans met criteria for history of severe TBI.Veterans were excluded from the analysis if unable to complete the mental health, neurological, or cognitive evaluations. Informed consent was obtained consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional guidelines established by the VA Palo Alto Human Subjects Review Committee. The study was approved by the VA Palo Alto and Stanford School of Medicine institutional review boards.

Cognitive Measures

All veterans completed a targeted cognitive battery that included the following: a reading recognition measure designed to estimate premorbid intellectual functioning (Wechsler Test of Adult Reading [WTAR]); a measure assessing auditory attention and working memory ability (Wechsler Adults Intelligence Scale-IV [WAIS-IV] Digit Span subtest); a measure assessing processing speed, attention, and cognitive flexibility (Trails A and B); and the RBANS.16,30-32The focus of the current study was on the RBANS, a brief cognitive screening measure that contains 12 subtests examining a variety of cognitive functions. Given that all participants were veterans receiving outpatient services, there was no nonpatient control group for comparison. To address this, all raw data were converted to standardized scores based on healthy normative data provided within the test manual. Specifically, the 12 RBANS subtest scores were converted to age-corrected standardized z scores, which in turn created a total summary score and 5 composite summary indexes: immediate memory, visuospatial/constructional, attention, language, and delayed memory. All veterans completed the Form A version of the measure.

Statistical Analyses

Group level differences on selective demographic and cognitive measures between veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD and those without were examined using t tests. Cognitive variables included standardized scores for the RBANS, including age-adjusted total summary score, index scores, and subtest scores.16 Estimated full-scale IQ and standardized summary scores from the WTAR, demographically adjusted standardized scores for the total time to complete Trails A and time to complete Trails B, and age-adjusted standardized scores for the WAIS-IV Digit Span subtest (forward, backward, and sequencing trials, as well as the summary total score) were examined for group differences.30,31,33 To further examine the association between PTSD and RBANS performance, multivariate multiple regressions were conducted using measures of episodic memory and processing speed from the RBANS (ie, story tasks, list learning tasks, and coding subtests). These specific measures were selected ad hoc based on extant literature.6,10The dependent variable for each analysis was the standardized score from the selected subtest; PTSD status, a diagnosis of TBI, a diagnosis of co-occurring TBI and PTSD, gender, and years of education were predictor variables.

Results

Of the 153 study participants, 98 (64%) met DSM-4 criteria for current PTSD, whereas 55 (36%) did not (Table). There was no group statistical difference between veterans with or without a diagnosis of PTSD for age, education, or gender (P < .05). A diagnosis of PTSD tended to be more frequent in participants with a history of head injury (χ2 = 7.72; P < .05). Veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD performed significantly worse on the RBANS Story Recall subtest compared with the results of those without PTSD (t[138] = 3.10; P < .01); performance on other cognitive measures was not significantly different between the PTSD groups. A diagnosis of PTSD was also significantly associated with self-reported depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory-II; t[123] = -2.81; P < .01). Depressive symptoms were not associated with a history of TBI, and group differences were not significant.

Given the high co-occurrence of PTSD and TBI (68%) in our PTSD sample, secondary analyses examined the association of select diagnoses with performance on the RBANS, specifically veterans with a historical diagnosis of TBI (n = 92) from those without a diagnosis of TBI (n = 61), as well as those with co-occurring PTSD and TBI (n = 71) from those without (n = 82). The majority of the sample met criteria for a history of mild TBI (n = 79) when compared with moderate TBI (n = 13); none met criteria for a past history of severe TBI. PTSD status (β = .63, P = .04) and years of education (β = .16, P < .01) were associated with performance on the RBANS Story Recall subtest (R2= .23, F[5,139] = 8.11, P < .01). Education was the only significant predictor for the rest of the multivariate multiple regressions (all P < .05). A diagnosis of TBI or co-occurring PTSD and TBI was not significantly associated with performance on the Story Memory, Story Recall, List Learning, List Recall, or Coding subtests. multivariate analysis of variance tests for the hypothesis of an overall main effect of PTSD (F(5,130) = 1.08, P = .34), TBI (F[5,130] = .91, P = .48), or PTSD+TBI (F[5,130] =.47, P = .80) on the 4 selected tests were not significant.

Discussion

The findings of the present study suggest that veterans with PTSD perform worse on specific RBANS subtests compared with veterans without PTSD. Specifically, worse performance on the Story Recall subtest of the RBANS memory index was a significant predictor of a diagnosis of PTSD within the statistical model. This association with PTSD was not seen in other demographic (excluding education) or cognitive measures, including other memory tasks, such as List Recall and Figure Recall, and attentional measures, such as WAIS-IV Digit Span, and the Trail Making Test. Overall RBANS index scores were not significantly different between groups, though this is not surprising given that recent research suggests the RBANS composite scores have questionable validity and reliability.34

The finding that a measure of episodic memory is most influenced by PTSD status is consistent with prior research.35 However, there are several possible reasons why Story Recall in particular showed the greatest association, even more than other episodic memory measures. A review by Isaac and colleagues found a diagnosis of PTSD correlated with frontal lobe-associated memory deficits.6 As Story Recall provides only 2 rehearsal trials compared with the 4 trials provided in the RBANS List Learning subtest, it is possible that Story Recall relies more on attentional processes than on learning with repetition.

Research has indicated attention and verbal episodic memory dysfunction are associated with a diagnosis of PTSD in combat veterans, and individuals with a diagnosis of PTSD show deficits in executive functioning, including attention difficulties beyond what is seen in trauma-exposed controls.4,7,8,11,35Furthermore, a diagnosis of PTSD has been shown to be associated with impaired performance on the Logical Memory subtest of the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised, a very similar measure to the RBANS Story Recall.36

The present finding that performance on a RBANS subtest was associated with a diagnosis of PTSD but not a history of TBI is not surprising. The majority of the present sample who reported a history of TBI met criteria for a remote head injury of mild severity (86%). Cognitive symptoms related to mild TBI are thought to generally resolve over time, and recent research suggests that PTSD symptoms may account for a substantial portion of reported postconcussive symptoms.37,38Similarly, recent research suggests a diagnosis of mild TBI does not necessarily result in additive cognitive impairment in combat veterans with a diagnosis of PTSD, and that a diagnosis of PTSD is more strongly associated with cognitive symptoms than is mild TBI.5,39,40

The lack of association with RBANS performance and co-occurring PTSD and TBI is less clear. Although both conditions are heterogenous, it may be that individuals with a diagnosis solely of PTSD are quantitively different from those with a concurrent diagnosis of PTSD and TBI (ie, PTSD presumed due to a mild TBI). Specifically, the impact of PTSD on cognition may be related to symptom severity and indexed trauma. A published systematic review on the PTSD-related cognitive impairment showed a medium-to-strong effect size for severity of PTSD symptoms on cognitive performance, with war trauma showing the strongest effect.4In particular, individuals who experience repeated or complex trauma are prone to experience PTSD symptoms with concurrent cognitive deficits, again suggesting the possibility of qualitative differences between outpatient veterans with PTSD and those with mild TBI associated PTSD.41While disentangling PTSD and mild TBI symptoms are notoriously difficult, future research aiming to examine these factors may be beneficial in the ability to draw larger conclusions on the relationship between cognition and PTSD.

Limitations

Several limitations may affect the generalizability of the findings. The present study used a veteran sample referred to a specialty clinic for complicated postdeployment health concerns. Although findings may not be representative of an inpatient population or clinics that focus solely on TBI, they may more adequately reflect veterans using clinical services at VA medical centers. We also did not include measures of PTSD symptom severity (eg, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist), instead using diagnosis based on the gold standard CAPS. In addition, the likelihood of the presence of a remote TBI was based on a clinical interview with a neurologist and not on acute neurologic findings. TBI is a heterogenous diagnosis, with multiple factors that likely influence cognitive performance, including location of the injury, type of injury, and time since injury, which may be lost during group analysis. Further, the RBANS is not intended to serve as a method for a differential diagnosis of PTSD or TBI. Concordant with this, the intention of the current study was to capture the quality of cognitive function on the RBANS within individuals with PTSD.

Conslusions

The ability for veterans to remember a short story following a delay (ie, RBANS Story Recall subtest) was negatively associated with a diagnosis of PTSD. Further, the RBANS best captured cognitive deficits associated with PTSD compared with those with a history of mild TBI, or co-occurring mild TBI and PTSD. These findings may provide insight into the interpretation and attribution of cognitive deficits in the veteran population and holds potential to guide future research examining focused cognitive phenotypes to provide precision targets in individual treatment.

1. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048-1060. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012

2. Schnurr PP, Lunney CA, Bovin MJ, Marx BP. Posttraumatic stress disorder and quality of life: extension of findings to veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):727-735. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.006

3. McNally RJ. Cognitive abnormalities in post-traumatic stress disorder. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10(6):271-277. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.04.007

4. Qureshi SU, Long ME, Bradshaw MR, et al. Does PTSD impair cognition beyond the effect of trauma? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(1):16-28. doi:10.1176/jnp.23.1.jnp16

5. Gordon SN, Fitzpatrick PJ, Hilsabeck RC. No effect of PTSD and other psychiatric disorders on cognitive functioning in veterans with mild TBI. Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;25(3):337-347. doi:10.1080/13854046.2010.550634

6. Isaac CL, Cushway D, Jones GV. Is posttraumatic stress disorder associated with specific deficits in episodic memory? Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(8):939-955. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.004

7. Johnsen GE, Asbjornsen AE. Consistent impaired verbal memory in PTSD: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2008;111(1):74-82. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.02.007

8. Polak AR, Witteveen AB, Reitsma JB, Olff M. The role of executive function in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(1):11-21. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.001

9. Scott JC, Matt GE, Wrocklage KM, et al. A quantitative meta-analysis of neurocognitive functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(1):105-140.

10. Vasterling JJ, Duke LM, Brailey K, Constans JI, Allain AN Jr, Sutker PB. Attention, learning, and memory performances and intellectual resources in Vietnam veterans: PTSD and no disorder comparisons. Neuropsychology. 2002;16(1):5-14. doi:10.1037//0894-4105.16.1.5

11. Wrocklage KM, Schweinsburg BC, Krystal JH, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: associations with performance validity, comorbidities, and functional outcomes. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2016;19:1-13. doi:10.1017/S1355617716000059

12. Yehuda R, Keefe RS, Harvey PD, et al. Learning and memory in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(1):137-139. doi:10.1176/ajp.152.1.137

13. Martindale SL, Morissette SB, Kimbrel NA, et al. Neuropsychological functioning, coping, and quality of life among returning war veterans. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61(3):231-239. doi:10.1037/rep0000076

14. Mackin SR, Lesselyong JA, Yaffe K. Pattern of cognitive impairment in older veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder evaluated at a memory disorders clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(6):637-642. doi:10.1002/gps.2763

15. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.61

16. Randolph C. RBANS Manual: Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. Psychological Corporation; 1998.

17. Duff K, Humphreys Clark JD, O'Bryant SE, Mold JW, Schiffer RB, Sutker PB. Utility of the RBANS in detecting cognitive impairment associated with Alzheimer's disease: sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive powers. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;23(5):603-612. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2008.06.004

18. Gold JM, Queern C, Iannone VN, Buchanan RW. Repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status as a screening test in schizophrenia I: sensitivity, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(12):1944-1950. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.12.1944

19. Beatty WW, Ryder KA, Gontkovsky ST, Scott JG, McSwan KL, Bharucha KJ. Analyzing the subcortical dementia syndrome of Parkinson's disease using the RBANS. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2003;18(5):509-520.

20. Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20(3):310-319. doi:10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823

21. Larson E, Kirschner K, Bode R, Heinemann A, Goodman R. Construct and predictive validity of the repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status in the evaluation of stroke patients. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2005;27(1):16-32. doi:10.1080/138033990513564

22. McKay C, Casey JE, Wertheimer J, Fichtenberg NL. Reliability and validity of the RBANS in a traumatic brain injured sample. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22(1):91-98. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2006.11.003

23. Lippa SM, Hawes S, Jokic E, Caroselli JS. Sensitivity of the RBANS to acute traumatic brain injury and length of post-traumatic amnesia. Brain Inj. 2013;27(6):689-695. doi:10.3109/02699052.2013.771793

24. Pachet AK. Construct validity of the Repeatable Battery of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) with acquired brain injury patients. Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;21(2):286-293. doi:10.1080/13854040500376823

25. McKay C, Wertheimer JC, Fichtenberg NL, Casey JE. The repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status (RBANS): clinical utility in a traumatic brain injury sample. Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;22(2):228-241. doi:10.1080/13854040701260370

26. Sheng T, Fairchild JK, Kong JY, et al. The influence of physical and mental health symptoms on Veterans’ functional health status. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(6):781-796. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2015.07.0146

27. Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, et al. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8(1):75-90. doi:10.1007/BF02105408

28. Mattson EK, Nelson NW, Sponheim SR, Disner SG. The impact of PTSD and mTBI on the relationship between subjective and objective cognitive deficits in combat-exposed veterans. Neuropsychology. Oct 2019;33(7):913-921. doi:10.1037/neu0000560

29. Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1993;8(3):86-87.

30. Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR). The Psychological Corporation; 2001.

31. Wechsler D. Wechsler Adults Intelligence Scale – Fourth Edition: Administration and Scoring Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2008.

32. Reitan R, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Therapy and Clinical Interpretation. Tuscon, AZ: Neuropsychological Press; 1985.

33. Heaton R, Miller S, Taylor M, Grant I. Revised Comprehensive Norms for an Expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically Ajdusted Neuropsychological Norms for African American and Caucasian Adults. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assesment Resources, Inc; 2004.

34. Vogt EM, Prichett GD, Hoelzle JB. Invariant two-component structure of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS). Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2017;24(1)50-64. doi:10.1080/23279095.2015.1088852

35. Gilbertson MW, Gurvits TV, Lasko NB, Orr SP, Pitman RK. Multivariate assessment of explicit memory function in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14(2):413-432. doi:10.1023/A:1011181305501

36. Bremner JD, Randall P, Scott TM, et al. Deficits in short-term memory in adult survivors of childhood abuse. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59(1-2):97-107. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(95)02800-5

37. Belanger HG, Curtiss G, Demery JA, Lebowitz BK, Vanderploeg RD. Factors moderating neuropsychological outcomes following mild traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005;11(3):215-227. doi:10.1017/S1355617705050277

38. Lippa SM, Pastorek NJ, Benge JF, Thornton GM. Postconcussive symptoms after blast and nonblast-related mild traumatic brain injuries in Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16(5):856-866. doi:10.1017/S1355617710000743

39. Soble JR, Spanierman LB, Fitzgerald Smith J. Neuropsychological functioning of combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder and mild traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2013;35(5):551-561. doi:10.1080/13803395.2013.798398

40. Vanderploeg RD, Belanger HG, Curtiss G. Mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder and their associations with health symptoms. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(7):1084-1093. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.023

41. Ainamani HE, Elbert T, Olema DK, Hecker T. PTSD symptom severity relates to cognitive and psycho-social dysfunctioning - a study with Congolese refugees in Uganda. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(1):1283086. doi:10.1080/20008198.2017.1283086

1. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048-1060. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012

2. Schnurr PP, Lunney CA, Bovin MJ, Marx BP. Posttraumatic stress disorder and quality of life: extension of findings to veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):727-735. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.006

3. McNally RJ. Cognitive abnormalities in post-traumatic stress disorder. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10(6):271-277. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.04.007

4. Qureshi SU, Long ME, Bradshaw MR, et al. Does PTSD impair cognition beyond the effect of trauma? J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(1):16-28. doi:10.1176/jnp.23.1.jnp16

5. Gordon SN, Fitzpatrick PJ, Hilsabeck RC. No effect of PTSD and other psychiatric disorders on cognitive functioning in veterans with mild TBI. Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;25(3):337-347. doi:10.1080/13854046.2010.550634

6. Isaac CL, Cushway D, Jones GV. Is posttraumatic stress disorder associated with specific deficits in episodic memory? Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(8):939-955. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.004

7. Johnsen GE, Asbjornsen AE. Consistent impaired verbal memory in PTSD: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2008;111(1):74-82. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2008.02.007

8. Polak AR, Witteveen AB, Reitsma JB, Olff M. The role of executive function in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(1):11-21. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.001

9. Scott JC, Matt GE, Wrocklage KM, et al. A quantitative meta-analysis of neurocognitive functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(1):105-140.

10. Vasterling JJ, Duke LM, Brailey K, Constans JI, Allain AN Jr, Sutker PB. Attention, learning, and memory performances and intellectual resources in Vietnam veterans: PTSD and no disorder comparisons. Neuropsychology. 2002;16(1):5-14. doi:10.1037//0894-4105.16.1.5

11. Wrocklage KM, Schweinsburg BC, Krystal JH, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: associations with performance validity, comorbidities, and functional outcomes. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2016;19:1-13. doi:10.1017/S1355617716000059

12. Yehuda R, Keefe RS, Harvey PD, et al. Learning and memory in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(1):137-139. doi:10.1176/ajp.152.1.137

13. Martindale SL, Morissette SB, Kimbrel NA, et al. Neuropsychological functioning, coping, and quality of life among returning war veterans. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61(3):231-239. doi:10.1037/rep0000076

14. Mackin SR, Lesselyong JA, Yaffe K. Pattern of cognitive impairment in older veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder evaluated at a memory disorders clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(6):637-642. doi:10.1002/gps.2763

15. Yaffe K, Vittinghoff E, Lindquist K, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of dementia among US veterans. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):608-613. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.61

16. Randolph C. RBANS Manual: Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status. Psychological Corporation; 1998.

17. Duff K, Humphreys Clark JD, O'Bryant SE, Mold JW, Schiffer RB, Sutker PB. Utility of the RBANS in detecting cognitive impairment associated with Alzheimer's disease: sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive powers. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;23(5):603-612. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2008.06.004

18. Gold JM, Queern C, Iannone VN, Buchanan RW. Repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status as a screening test in schizophrenia I: sensitivity, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(12):1944-1950. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.12.1944

19. Beatty WW, Ryder KA, Gontkovsky ST, Scott JG, McSwan KL, Bharucha KJ. Analyzing the subcortical dementia syndrome of Parkinson's disease using the RBANS. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2003;18(5):509-520.

20. Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20(3):310-319. doi:10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823

21. Larson E, Kirschner K, Bode R, Heinemann A, Goodman R. Construct and predictive validity of the repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status in the evaluation of stroke patients. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2005;27(1):16-32. doi:10.1080/138033990513564

22. McKay C, Casey JE, Wertheimer J, Fichtenberg NL. Reliability and validity of the RBANS in a traumatic brain injured sample. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22(1):91-98. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2006.11.003

23. Lippa SM, Hawes S, Jokic E, Caroselli JS. Sensitivity of the RBANS to acute traumatic brain injury and length of post-traumatic amnesia. Brain Inj. 2013;27(6):689-695. doi:10.3109/02699052.2013.771793

24. Pachet AK. Construct validity of the Repeatable Battery of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) with acquired brain injury patients. Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;21(2):286-293. doi:10.1080/13854040500376823

25. McKay C, Wertheimer JC, Fichtenberg NL, Casey JE. The repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status (RBANS): clinical utility in a traumatic brain injury sample. Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;22(2):228-241. doi:10.1080/13854040701260370

26. Sheng T, Fairchild JK, Kong JY, et al. The influence of physical and mental health symptoms on Veterans’ functional health status. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2016;53(6):781-796. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2015.07.0146

27. Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, et al. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8(1):75-90. doi:10.1007/BF02105408

28. Mattson EK, Nelson NW, Sponheim SR, Disner SG. The impact of PTSD and mTBI on the relationship between subjective and objective cognitive deficits in combat-exposed veterans. Neuropsychology. Oct 2019;33(7):913-921. doi:10.1037/neu0000560

29. Definition of mild traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1993;8(3):86-87.

30. Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR). The Psychological Corporation; 2001.

31. Wechsler D. Wechsler Adults Intelligence Scale – Fourth Edition: Administration and Scoring Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2008.

32. Reitan R, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Therapy and Clinical Interpretation. Tuscon, AZ: Neuropsychological Press; 1985.

33. Heaton R, Miller S, Taylor M, Grant I. Revised Comprehensive Norms for an Expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically Ajdusted Neuropsychological Norms for African American and Caucasian Adults. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assesment Resources, Inc; 2004.

34. Vogt EM, Prichett GD, Hoelzle JB. Invariant two-component structure of the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS). Appl Neuropsychol Adult. 2017;24(1)50-64. doi:10.1080/23279095.2015.1088852

35. Gilbertson MW, Gurvits TV, Lasko NB, Orr SP, Pitman RK. Multivariate assessment of explicit memory function in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14(2):413-432. doi:10.1023/A:1011181305501

36. Bremner JD, Randall P, Scott TM, et al. Deficits in short-term memory in adult survivors of childhood abuse. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59(1-2):97-107. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(95)02800-5

37. Belanger HG, Curtiss G, Demery JA, Lebowitz BK, Vanderploeg RD. Factors moderating neuropsychological outcomes following mild traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2005;11(3):215-227. doi:10.1017/S1355617705050277

38. Lippa SM, Pastorek NJ, Benge JF, Thornton GM. Postconcussive symptoms after blast and nonblast-related mild traumatic brain injuries in Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2010;16(5):856-866. doi:10.1017/S1355617710000743

39. Soble JR, Spanierman LB, Fitzgerald Smith J. Neuropsychological functioning of combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder and mild traumatic brain injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2013;35(5):551-561. doi:10.1080/13803395.2013.798398

40. Vanderploeg RD, Belanger HG, Curtiss G. Mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder and their associations with health symptoms. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(7):1084-1093. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.023

41. Ainamani HE, Elbert T, Olema DK, Hecker T. PTSD symptom severity relates to cognitive and psycho-social dysfunctioning - a study with Congolese refugees in Uganda. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2017;8(1):1283086. doi:10.1080/20008198.2017.1283086

A Clinical Program to Implement Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Depression in the Department of Veterans Affairs

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is an emerging therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for mental health indications but not widely available in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). rTMS uses a device to create magnetic fields that cause electrical current to flow into targeted neurons in the brain.1 The area of the brain targeted depends on the shape of the magnetic coil and dose of stimulation (Figures 1 and 2). The most common coil shape is the figure-8 coil, which is believed to stimulate about a 2- to 3-cm2 area of the brain at a depth of about 2 cm from the coil surface. The stimulus is thought to activate certain nerve growth factors and ultimately relevant neurotransmitters in the stimulated areas and parts of the brain connected to where the stimulus occurs.2

The most common clinical use of rTMS is for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). The FDA has approved rTMS for the treatment of MDD and for at least 4 device manufacturers. The treatment has been studied in multiple clinical trials.3 An overview of these trials, additional rTMS training and educational materials, and device information can be accessed at www.mirecc.va.gov/visn21/education/tms_education.asp. rTMS for MDD administers a personalized dose with stimulation delivered over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. A typical clinical course runs for 40 minutes a day for 20 to 30 sessions. In addition to studies of depression,1,4-7 rTMS has been studied for the following diseases and conditions:

- Headache (especially migraine)8

- Alzheimer disease9

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)10

- Obesity11

- Schizophrenia12

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)13

- Alcohol and nicotine dependence14

The FDA also has approved the use of rTMS for OCD. In addition, some health care providers (HCPs) are treating depression with rTMS in conjunction with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

Treatment for Veterans

MDD is one of the most significant risk factors for suicide. Therefore, treating depression with rTMS would likely diminish suicide risk. The annual suicide rate among veterans has been higher than the national average.15 However, most of these veterans are not getting their care at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Major efforts at the VA have been made to address this problem, including modification and promotion of the Veterans Crisis Line, increased mental health clinic hours, mental health same-day appointment availability for veterans, as well as raising awareness of suicide and suicidal ideation.16 George and colleagues showed that it is safe and feasible to treat acutely suicidal inpatients at a VA or US Department of Defense hospital over an intensive 3 day, 3 treatments per day regimen. This regimen would be potentially useful in a suicidal inpatient population, a technically and ethically difficult group to study.17

MDD in many patients can be chronic and reoccurring with medication and psychotherapy providing inadequate relief.17 There clearly is a need for additional treatment options. MDD and OCD are the only indications that have received FDA approval for rTMS use. The initial FDA approval for MDD was based on a 2007 study of medication-free patients who had failed previous therapy and found a significant effect of rTMS compared with a sham procedure.7 MDD remains a common problem among veterans who have failed one or more antidepressant medications. Such patients might benefit from rTMS.6,18

rTMS has several advantages over ECT, another significant FDA-approved, nonpharmacologic treatment alternative for medication-refractory MDD. rTMS is less invasive, requires fewer resources, does not require anesthesia or restrict activities, and does not cause memory loss. After an rTMS treatment, the patient can drive home.

Nationwide Pilot Program

The VA pilot program was created to supply rTMS machines nationwide to VHA sites and to offer a framework for establishing a clinical program. Preliminary program evaluation data suggest patients experienced a reduction in depression and suicidal ideation.

There were many challenges to implementation; for example, one VA site was eager to start using the device but could not secure space or personnel. An interdisciplinary team consisting of physicians, nurses, psychologists, suicide prevention coordinators, and others in the VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Precision Neurostimulation Clinic (PNC) has been instrumental in overcoming these challenges. VAPAHCS oversees the pilot and employs the national director.

Thirty-five sites nationwide were initially selected due to their ability to provide space for a rTMS machine and appropriate staffing to set up and run a Clinic (Figure 3). The pilot started with tertiary care VA medical centers then expanded to include community-based outpatient clinics as resources permitted. Sites that were unable to meet these standards were not included. Of these 35 original sites, 26 are treating patients and collecting data. Some early delays were due to unassigned relative value units (RVUs) to rTMS, which since have been revised as imputed RVU values. The American Medical Association established and defined RVUs to compare the value of different health care roles.19 The clinics have been established with smooth operations as the pilot program has provided the infrastructure.

REDCap (www.project-redcap.org), a data collection tool used primarily in academic research settings, was selected to gather program evaluation data through patient questionnaires informed by the VHA measurement-based care initiative. Standard psychometrics were readily available in the VHA application and REDCap Mental Health Assistant includes the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) Brief Symptom Inventory 18, Posttraumatic Checklist 5, Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, and Quality of Life Inventory. The Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scale (TCFES), which can be completed in 30 to 35 minutes and is a measure of overall function of relevant relationships, also may be added. Future studies are needed to confirm psychometrics of this scale in this setting, but the TCFES metric is widely used for similar purposes.

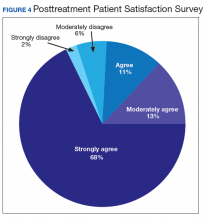

Nationwide, more than 950 patients have started treatment (ie, including active, completed, and discontinued treatment) and 412 veterans have completed the rTMS treatment. The goal of the program evaluation is to examine large scale rTMS efficacy in a large veteran population as well as determine predictors of individual patient response. Nationwide, PHQ-9 depression scores declined from a pretreatment average (SD) of 18.2 (5.5; range, 5-27) to a posttreatment average (SD) of 11.0 (7.1; range, 0-27). Patients also have indicated a high level of satisfaction with the treatment (Figure 4). Collecting data on a national level is a powerful way to examine rTMS efficacy and predictors of response that might be lost in a smaller subset of cases.

Implementation

It took 11 months for the VA contracting department to determine which machine to buy. However, the lengthy process assured that the equipment selected met all standards for clinical safety and efficacy. Furthermore, provision was made to allow for additional orders as new sites came online as well as upgrading the equipment for advances in technology.