User login

MDMA Is Off the Table, So What’s Next for PTSD?

It has been 24 years since a pharmaceutical was last approved for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The condition is notoriously difficult to treat, with up to 40% patients finding no relief from symptoms through psychotherapy or current medications.

Many clinicians, advocates, and patients had pinned their hopes on the psychedelic drug midomafetamine with assisted therapy (MDMA-AT). However, in August, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rejected it. At this point, it’s unclear when the therapy will be available, if ever.

“Not getting the FDA approval of any drug at this point is a setback for the field,” Lori Davis, MD, a senior research psychiatrist at the Birmingham Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System in Birmingham, Alabama, told Medscape Medical News.

Having an FDA-approved product would have helped increase public awareness of PTSD and driven interest in developing new therapies, said Davis, who is also adjunct professor of psychiatry at the Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

A Treatable Condition

So with MDMA-AT off the table, where does the field go next?

A public meeting in September hosted by the Reagan-Udall Foundation for the FDA in sought to answer that question. Agency officials joined representatives from the Department of Defense (DoD) and VA, patients, advocates, and industry representatives to discuss the current treatment landscape and what can be done to accelerate development of PTSD treatment.

Despite the common belief that PTSD is intractable, it “is a treatable condition,” Paula P. Schnurr, PhD, executive director of the VA National Center for PTSD, said at the meeting.

“There are effective treatments that work well for a lot of people, although not everyone has a satisfactory response,” she added.

The most effective psychotherapies are “trauma-focused,” and include cognitive processing therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, and prolonged exposure, according to the VA National Center for PTSD.

Three drugs have been approved by the FDA for PTSD: Venlafaxine (Effexor) in 1993, sertraline (Zoloft) in 1999, and paroxetine (Paxil) in 2000.

However, as the September meeting demonstrated, more therapies are needed.

“It’s clear to FDA and the federal government at large that there is an unmet need for safe and effective therapies to treat PTSD,” Bernard Fischer, MD, deputy director of the Division of Psychiatry in the Office of New Drugs at FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said at the meeting.

There is no shortage of research, Fischer added. Nearly 500 trials focused on PTSD are listed on clinicaltrials.gov are recruiting participants now or plan to soon.

Unsurprisingly, one of the primary drivers of PTSD therapeutics research is the VA. About 14% of the 5.7 million veterans who received care through the VA in 2023 had a diagnosis of PTSD.

“The US military is currently losing thousands of service members each year to PTSD- related disability discharges,” US Army Maj. Aaron Wolfgang, MD, a psychiatrist at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, said at the meeting. Only about 12%-20% of patients achieve remission with conventional therapies, added Wolfgang, who also is an assistant professor at the Uniformed Services University.

“For these reasons, establishing better treatments for PTSD is not only a matter of humanitarianism but also a pressing matter of national security,” he said.

The VA has committed at least $230 million to more than 140 active research projects in PTSD, Miriam J. Smyth, PhD, acting director of the clinical science, research and development service at the VA, said at the Reagan-Udall meeting.

One of the VA projects is the PTSD psychopharmacology initiative, which began in 2017 and now has 14 active clinical trials, said Smyth, who is also acting director for brain behavior and mental health at the VA. The first study should be finished by 2025.

The Million Veteran Program, with more than 1 million enrollees, has led to the discovery of genes related to re-experiencing traumatic memories and has confirmed that both PTSD and traumatic brain injury are risk factors for dementia, Smyth said.

The DoD has created a novel platform that establishes a common infrastructure for testing multiple drugs, called M-PACT. The platform allows sharing of placebo data across treatment arms. Drugs cycle off the platform if evidence indicates probability of success or failure.

Four trials are actively recruiting veterans and current service members. One is looking at vilazodone, approved in 2011 for major depressive disorder. It is being compared with placebo and fluoxetine in a trial that is currently recruiting.

Another trial will study daridorexant (sold as Quviviq), an orexin receptor antagonist, against placebo. The FDA approved daridorexant in 2022 as an insomnia treatment. A core issue in PTSD is sleep disruption, noted Davis.

New Therapies on the Way

Separately, Davis and colleagues are also studying methylphenidate, the stimulant used for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. It may help with neurocognitive complaints and reduce PTSD symptoms, said Davis.

Because it is generic, few pharmaceutical manufacturers are likely to test it for PTSD, she said. But eventually, their work may lead a company to test newer stimulants for PTSD, she said.

Another potential therapeutic, BNC210, received Fast Track designation for PTSD from the FDA in 2019. Bionomics Limited in Australia will soon launch phase 3 trials of the investigational oral drug, which is a negative allosteric modulator of the alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. In late July, the company announced “ favorable feedback” from the agency on its phase 2 study, which led to the decision to move forward with larger trials.

Researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital have just reported that they may have found a target within the brain that will allow for transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to ameliorate PTSD symptoms. They published results of a mapping effort in Nature Neuroscience and reported on one patient who had improved symptoms after receiving TMS for severe PTSD.

But perhaps one of the most promising treatments is a combination of sertraline and the new psychiatric medication brexpiprazole.

Brexpiprazole was developed by Otsuka Pharmaceutical and approved in the United States in 2015 as an adjunctive therapy to antidepressants for major depressive disorder and as a treatment for schizophrenia. In 2023, the FDA approved it for Alzheimer’s-related agitation. However, according to Otsuka, its mechanism of action is unknown.

Its efficacy may be mediated through a combination of partial agonist activity at serotonin 5-HT1A and dopamine D2 receptors, antagonist activity at serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, as well as antagonism of alpha-1B/2C receptors, said the company.

“It is the combination, rather than either alone, that’s going to have that broad synergistic pharmacology that is obviously potent for ameliorating the symptoms of PTSD,” said Davis, who has received consulting fees from Otsuka. “That’s an exciting development.”

Otsuka and partner Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals reported results in May from the companies’ phase 2 and 3 randomized clinical trials. The therapy achieved a statistically significant reduction (P <.05) in PTSD symptoms compared with sertraline plus placebo. This was without any supplemental psychotherapy.

The FDA accepted the companies’ new drug application in June and is expected to make a decision on approval in February 2025.

The Potential of Psychedelics

Though Lykos Therapeutics may have to go back to the drawing board on its MDMA-AT, psychedelics still have potential as PTSD therapies, Smyth said, who added that the VA is continuing to encourage study of MDMA and other psychedelic agents.

The VA issued a call for proposals for research on psychedelics in January, focused on MDMA or psilocybin in combination with psychotherapy. The administration received the first wave of applications early in the summer.

Scientific peer review panels made up of research experts from within and outside the VA have reviewed the applications and funding announcements are expected this fall, Smyth said.

Wolfgang, the Army psychiatrist, said, “Under the psychedelic treatment research clinical trial award, we welcome investigators to apply to what we anticipate will usher in a new era of innovation and hope for service members and their families who need it the most.”

Psychedelic studies are also proceeding without VA funding, as they have for years, when most of the trials were backed by universities or foundations or other private money. Johns Hopkins University is recruiting for a study in which patients would receive psilocybin along with trauma-focused psychotherapy, as is Ohio State University.

London-based Compass Pathways said in May that it successfully completed a phase 2 trial of Comp360, its synthetic psilocybin, in PTSD. The company has started a phase 3 study in treatment-resistant depression but has not given any further updates on PTSD.

Davis said that she believes that the FDA’s rejection of Lykos won’t lead to a shutdown of exploration of psychedelics.

“I think it informs these designs going forward, but it doesn’t eliminate that whole field of research,” she said.

Davis reported receiving consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Otsuka and research funding from Alkermes, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and the VA. Schnurr, Fischer, Smyth, and Wolfgang reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

It has been 24 years since a pharmaceutical was last approved for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The condition is notoriously difficult to treat, with up to 40% patients finding no relief from symptoms through psychotherapy or current medications.

Many clinicians, advocates, and patients had pinned their hopes on the psychedelic drug midomafetamine with assisted therapy (MDMA-AT). However, in August, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rejected it. At this point, it’s unclear when the therapy will be available, if ever.

“Not getting the FDA approval of any drug at this point is a setback for the field,” Lori Davis, MD, a senior research psychiatrist at the Birmingham Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System in Birmingham, Alabama, told Medscape Medical News.

Having an FDA-approved product would have helped increase public awareness of PTSD and driven interest in developing new therapies, said Davis, who is also adjunct professor of psychiatry at the Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

A Treatable Condition

So with MDMA-AT off the table, where does the field go next?

A public meeting in September hosted by the Reagan-Udall Foundation for the FDA in sought to answer that question. Agency officials joined representatives from the Department of Defense (DoD) and VA, patients, advocates, and industry representatives to discuss the current treatment landscape and what can be done to accelerate development of PTSD treatment.

Despite the common belief that PTSD is intractable, it “is a treatable condition,” Paula P. Schnurr, PhD, executive director of the VA National Center for PTSD, said at the meeting.

“There are effective treatments that work well for a lot of people, although not everyone has a satisfactory response,” she added.

The most effective psychotherapies are “trauma-focused,” and include cognitive processing therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, and prolonged exposure, according to the VA National Center for PTSD.

Three drugs have been approved by the FDA for PTSD: Venlafaxine (Effexor) in 1993, sertraline (Zoloft) in 1999, and paroxetine (Paxil) in 2000.

However, as the September meeting demonstrated, more therapies are needed.

“It’s clear to FDA and the federal government at large that there is an unmet need for safe and effective therapies to treat PTSD,” Bernard Fischer, MD, deputy director of the Division of Psychiatry in the Office of New Drugs at FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said at the meeting.

There is no shortage of research, Fischer added. Nearly 500 trials focused on PTSD are listed on clinicaltrials.gov are recruiting participants now or plan to soon.

Unsurprisingly, one of the primary drivers of PTSD therapeutics research is the VA. About 14% of the 5.7 million veterans who received care through the VA in 2023 had a diagnosis of PTSD.

“The US military is currently losing thousands of service members each year to PTSD- related disability discharges,” US Army Maj. Aaron Wolfgang, MD, a psychiatrist at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, said at the meeting. Only about 12%-20% of patients achieve remission with conventional therapies, added Wolfgang, who also is an assistant professor at the Uniformed Services University.

“For these reasons, establishing better treatments for PTSD is not only a matter of humanitarianism but also a pressing matter of national security,” he said.

The VA has committed at least $230 million to more than 140 active research projects in PTSD, Miriam J. Smyth, PhD, acting director of the clinical science, research and development service at the VA, said at the Reagan-Udall meeting.

One of the VA projects is the PTSD psychopharmacology initiative, which began in 2017 and now has 14 active clinical trials, said Smyth, who is also acting director for brain behavior and mental health at the VA. The first study should be finished by 2025.

The Million Veteran Program, with more than 1 million enrollees, has led to the discovery of genes related to re-experiencing traumatic memories and has confirmed that both PTSD and traumatic brain injury are risk factors for dementia, Smyth said.

The DoD has created a novel platform that establishes a common infrastructure for testing multiple drugs, called M-PACT. The platform allows sharing of placebo data across treatment arms. Drugs cycle off the platform if evidence indicates probability of success or failure.

Four trials are actively recruiting veterans and current service members. One is looking at vilazodone, approved in 2011 for major depressive disorder. It is being compared with placebo and fluoxetine in a trial that is currently recruiting.

Another trial will study daridorexant (sold as Quviviq), an orexin receptor antagonist, against placebo. The FDA approved daridorexant in 2022 as an insomnia treatment. A core issue in PTSD is sleep disruption, noted Davis.

New Therapies on the Way

Separately, Davis and colleagues are also studying methylphenidate, the stimulant used for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. It may help with neurocognitive complaints and reduce PTSD symptoms, said Davis.

Because it is generic, few pharmaceutical manufacturers are likely to test it for PTSD, she said. But eventually, their work may lead a company to test newer stimulants for PTSD, she said.

Another potential therapeutic, BNC210, received Fast Track designation for PTSD from the FDA in 2019. Bionomics Limited in Australia will soon launch phase 3 trials of the investigational oral drug, which is a negative allosteric modulator of the alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. In late July, the company announced “ favorable feedback” from the agency on its phase 2 study, which led to the decision to move forward with larger trials.

Researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital have just reported that they may have found a target within the brain that will allow for transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to ameliorate PTSD symptoms. They published results of a mapping effort in Nature Neuroscience and reported on one patient who had improved symptoms after receiving TMS for severe PTSD.

But perhaps one of the most promising treatments is a combination of sertraline and the new psychiatric medication brexpiprazole.

Brexpiprazole was developed by Otsuka Pharmaceutical and approved in the United States in 2015 as an adjunctive therapy to antidepressants for major depressive disorder and as a treatment for schizophrenia. In 2023, the FDA approved it for Alzheimer’s-related agitation. However, according to Otsuka, its mechanism of action is unknown.

Its efficacy may be mediated through a combination of partial agonist activity at serotonin 5-HT1A and dopamine D2 receptors, antagonist activity at serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, as well as antagonism of alpha-1B/2C receptors, said the company.

“It is the combination, rather than either alone, that’s going to have that broad synergistic pharmacology that is obviously potent for ameliorating the symptoms of PTSD,” said Davis, who has received consulting fees from Otsuka. “That’s an exciting development.”

Otsuka and partner Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals reported results in May from the companies’ phase 2 and 3 randomized clinical trials. The therapy achieved a statistically significant reduction (P <.05) in PTSD symptoms compared with sertraline plus placebo. This was without any supplemental psychotherapy.

The FDA accepted the companies’ new drug application in June and is expected to make a decision on approval in February 2025.

The Potential of Psychedelics

Though Lykos Therapeutics may have to go back to the drawing board on its MDMA-AT, psychedelics still have potential as PTSD therapies, Smyth said, who added that the VA is continuing to encourage study of MDMA and other psychedelic agents.

The VA issued a call for proposals for research on psychedelics in January, focused on MDMA or psilocybin in combination with psychotherapy. The administration received the first wave of applications early in the summer.

Scientific peer review panels made up of research experts from within and outside the VA have reviewed the applications and funding announcements are expected this fall, Smyth said.

Wolfgang, the Army psychiatrist, said, “Under the psychedelic treatment research clinical trial award, we welcome investigators to apply to what we anticipate will usher in a new era of innovation and hope for service members and their families who need it the most.”

Psychedelic studies are also proceeding without VA funding, as they have for years, when most of the trials were backed by universities or foundations or other private money. Johns Hopkins University is recruiting for a study in which patients would receive psilocybin along with trauma-focused psychotherapy, as is Ohio State University.

London-based Compass Pathways said in May that it successfully completed a phase 2 trial of Comp360, its synthetic psilocybin, in PTSD. The company has started a phase 3 study in treatment-resistant depression but has not given any further updates on PTSD.

Davis said that she believes that the FDA’s rejection of Lykos won’t lead to a shutdown of exploration of psychedelics.

“I think it informs these designs going forward, but it doesn’t eliminate that whole field of research,” she said.

Davis reported receiving consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Otsuka and research funding from Alkermes, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and the VA. Schnurr, Fischer, Smyth, and Wolfgang reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

It has been 24 years since a pharmaceutical was last approved for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The condition is notoriously difficult to treat, with up to 40% patients finding no relief from symptoms through psychotherapy or current medications.

Many clinicians, advocates, and patients had pinned their hopes on the psychedelic drug midomafetamine with assisted therapy (MDMA-AT). However, in August, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rejected it. At this point, it’s unclear when the therapy will be available, if ever.

“Not getting the FDA approval of any drug at this point is a setback for the field,” Lori Davis, MD, a senior research psychiatrist at the Birmingham Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System in Birmingham, Alabama, told Medscape Medical News.

Having an FDA-approved product would have helped increase public awareness of PTSD and driven interest in developing new therapies, said Davis, who is also adjunct professor of psychiatry at the Heersink School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

A Treatable Condition

So with MDMA-AT off the table, where does the field go next?

A public meeting in September hosted by the Reagan-Udall Foundation for the FDA in sought to answer that question. Agency officials joined representatives from the Department of Defense (DoD) and VA, patients, advocates, and industry representatives to discuss the current treatment landscape and what can be done to accelerate development of PTSD treatment.

Despite the common belief that PTSD is intractable, it “is a treatable condition,” Paula P. Schnurr, PhD, executive director of the VA National Center for PTSD, said at the meeting.

“There are effective treatments that work well for a lot of people, although not everyone has a satisfactory response,” she added.

The most effective psychotherapies are “trauma-focused,” and include cognitive processing therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, and prolonged exposure, according to the VA National Center for PTSD.

Three drugs have been approved by the FDA for PTSD: Venlafaxine (Effexor) in 1993, sertraline (Zoloft) in 1999, and paroxetine (Paxil) in 2000.

However, as the September meeting demonstrated, more therapies are needed.

“It’s clear to FDA and the federal government at large that there is an unmet need for safe and effective therapies to treat PTSD,” Bernard Fischer, MD, deputy director of the Division of Psychiatry in the Office of New Drugs at FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said at the meeting.

There is no shortage of research, Fischer added. Nearly 500 trials focused on PTSD are listed on clinicaltrials.gov are recruiting participants now or plan to soon.

Unsurprisingly, one of the primary drivers of PTSD therapeutics research is the VA. About 14% of the 5.7 million veterans who received care through the VA in 2023 had a diagnosis of PTSD.

“The US military is currently losing thousands of service members each year to PTSD- related disability discharges,” US Army Maj. Aaron Wolfgang, MD, a psychiatrist at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, said at the meeting. Only about 12%-20% of patients achieve remission with conventional therapies, added Wolfgang, who also is an assistant professor at the Uniformed Services University.

“For these reasons, establishing better treatments for PTSD is not only a matter of humanitarianism but also a pressing matter of national security,” he said.

The VA has committed at least $230 million to more than 140 active research projects in PTSD, Miriam J. Smyth, PhD, acting director of the clinical science, research and development service at the VA, said at the Reagan-Udall meeting.

One of the VA projects is the PTSD psychopharmacology initiative, which began in 2017 and now has 14 active clinical trials, said Smyth, who is also acting director for brain behavior and mental health at the VA. The first study should be finished by 2025.

The Million Veteran Program, with more than 1 million enrollees, has led to the discovery of genes related to re-experiencing traumatic memories and has confirmed that both PTSD and traumatic brain injury are risk factors for dementia, Smyth said.

The DoD has created a novel platform that establishes a common infrastructure for testing multiple drugs, called M-PACT. The platform allows sharing of placebo data across treatment arms. Drugs cycle off the platform if evidence indicates probability of success or failure.

Four trials are actively recruiting veterans and current service members. One is looking at vilazodone, approved in 2011 for major depressive disorder. It is being compared with placebo and fluoxetine in a trial that is currently recruiting.

Another trial will study daridorexant (sold as Quviviq), an orexin receptor antagonist, against placebo. The FDA approved daridorexant in 2022 as an insomnia treatment. A core issue in PTSD is sleep disruption, noted Davis.

New Therapies on the Way

Separately, Davis and colleagues are also studying methylphenidate, the stimulant used for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. It may help with neurocognitive complaints and reduce PTSD symptoms, said Davis.

Because it is generic, few pharmaceutical manufacturers are likely to test it for PTSD, she said. But eventually, their work may lead a company to test newer stimulants for PTSD, she said.

Another potential therapeutic, BNC210, received Fast Track designation for PTSD from the FDA in 2019. Bionomics Limited in Australia will soon launch phase 3 trials of the investigational oral drug, which is a negative allosteric modulator of the alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. In late July, the company announced “ favorable feedback” from the agency on its phase 2 study, which led to the decision to move forward with larger trials.

Researchers at Brigham and Women’s Hospital have just reported that they may have found a target within the brain that will allow for transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to ameliorate PTSD symptoms. They published results of a mapping effort in Nature Neuroscience and reported on one patient who had improved symptoms after receiving TMS for severe PTSD.

But perhaps one of the most promising treatments is a combination of sertraline and the new psychiatric medication brexpiprazole.

Brexpiprazole was developed by Otsuka Pharmaceutical and approved in the United States in 2015 as an adjunctive therapy to antidepressants for major depressive disorder and as a treatment for schizophrenia. In 2023, the FDA approved it for Alzheimer’s-related agitation. However, according to Otsuka, its mechanism of action is unknown.

Its efficacy may be mediated through a combination of partial agonist activity at serotonin 5-HT1A and dopamine D2 receptors, antagonist activity at serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, as well as antagonism of alpha-1B/2C receptors, said the company.

“It is the combination, rather than either alone, that’s going to have that broad synergistic pharmacology that is obviously potent for ameliorating the symptoms of PTSD,” said Davis, who has received consulting fees from Otsuka. “That’s an exciting development.”

Otsuka and partner Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals reported results in May from the companies’ phase 2 and 3 randomized clinical trials. The therapy achieved a statistically significant reduction (P <.05) in PTSD symptoms compared with sertraline plus placebo. This was without any supplemental psychotherapy.

The FDA accepted the companies’ new drug application in June and is expected to make a decision on approval in February 2025.

The Potential of Psychedelics

Though Lykos Therapeutics may have to go back to the drawing board on its MDMA-AT, psychedelics still have potential as PTSD therapies, Smyth said, who added that the VA is continuing to encourage study of MDMA and other psychedelic agents.

The VA issued a call for proposals for research on psychedelics in January, focused on MDMA or psilocybin in combination with psychotherapy. The administration received the first wave of applications early in the summer.

Scientific peer review panels made up of research experts from within and outside the VA have reviewed the applications and funding announcements are expected this fall, Smyth said.

Wolfgang, the Army psychiatrist, said, “Under the psychedelic treatment research clinical trial award, we welcome investigators to apply to what we anticipate will usher in a new era of innovation and hope for service members and their families who need it the most.”

Psychedelic studies are also proceeding without VA funding, as they have for years, when most of the trials were backed by universities or foundations or other private money. Johns Hopkins University is recruiting for a study in which patients would receive psilocybin along with trauma-focused psychotherapy, as is Ohio State University.

London-based Compass Pathways said in May that it successfully completed a phase 2 trial of Comp360, its synthetic psilocybin, in PTSD. The company has started a phase 3 study in treatment-resistant depression but has not given any further updates on PTSD.

Davis said that she believes that the FDA’s rejection of Lykos won’t lead to a shutdown of exploration of psychedelics.

“I think it informs these designs going forward, but it doesn’t eliminate that whole field of research,” she said.

Davis reported receiving consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Otsuka and research funding from Alkermes, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and the VA. Schnurr, Fischer, Smyth, and Wolfgang reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

PTSD Comorbidities

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Editor's Note: This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

Persistent headaches and nightmares

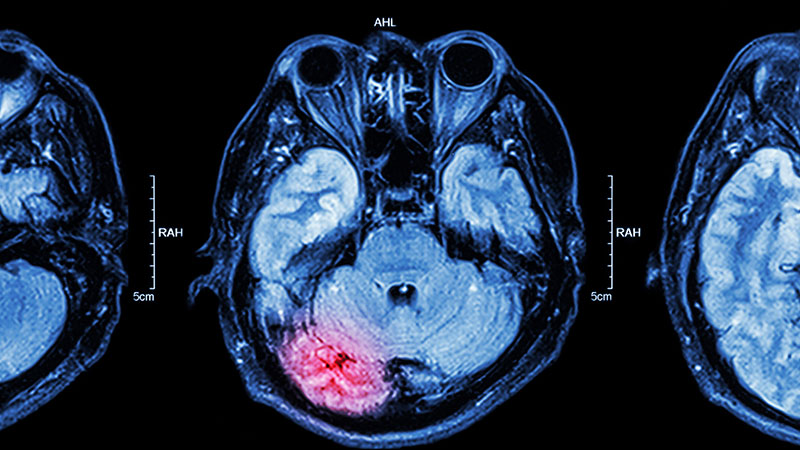

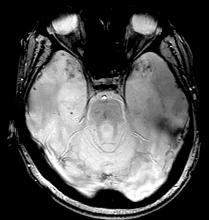

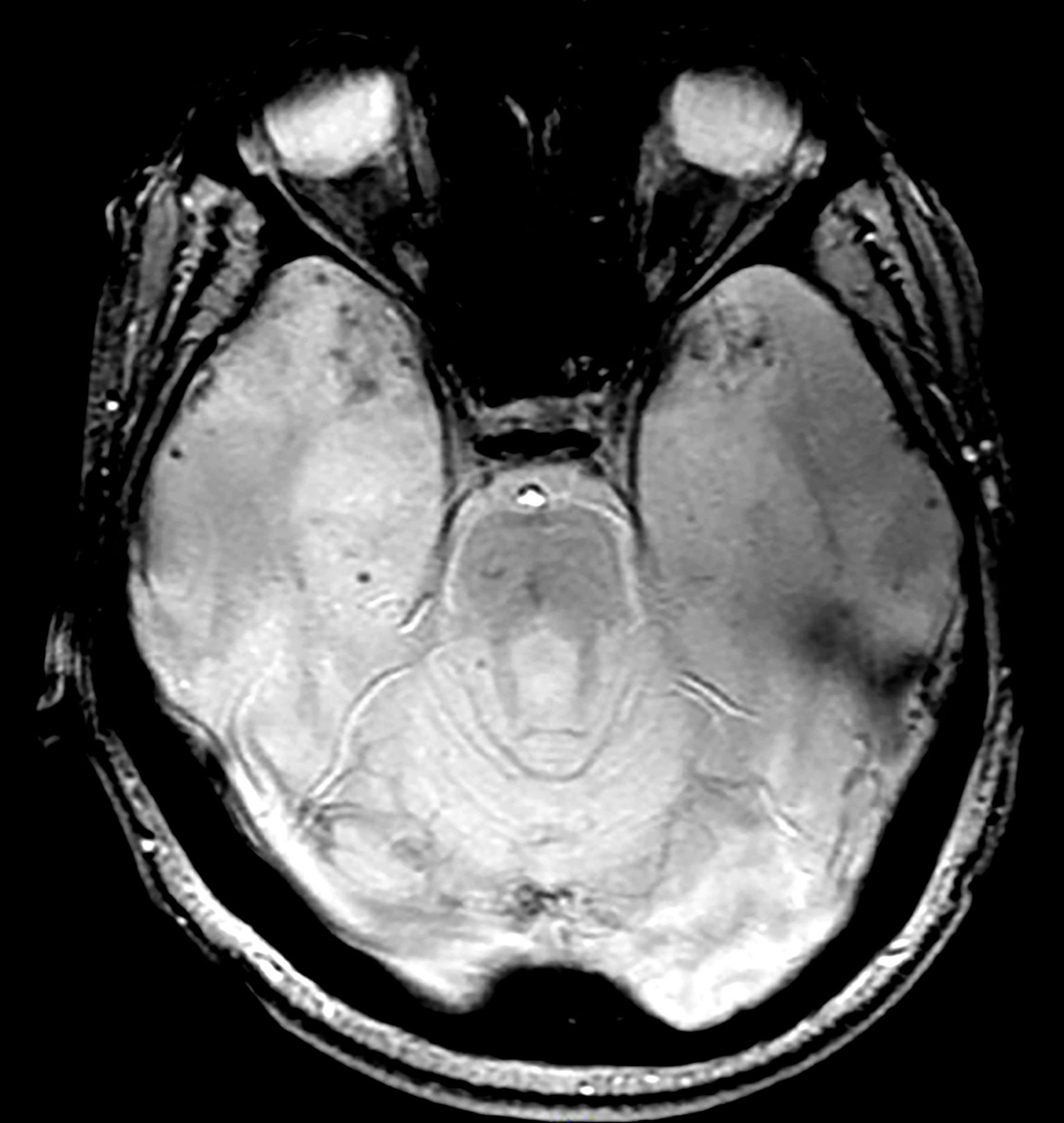

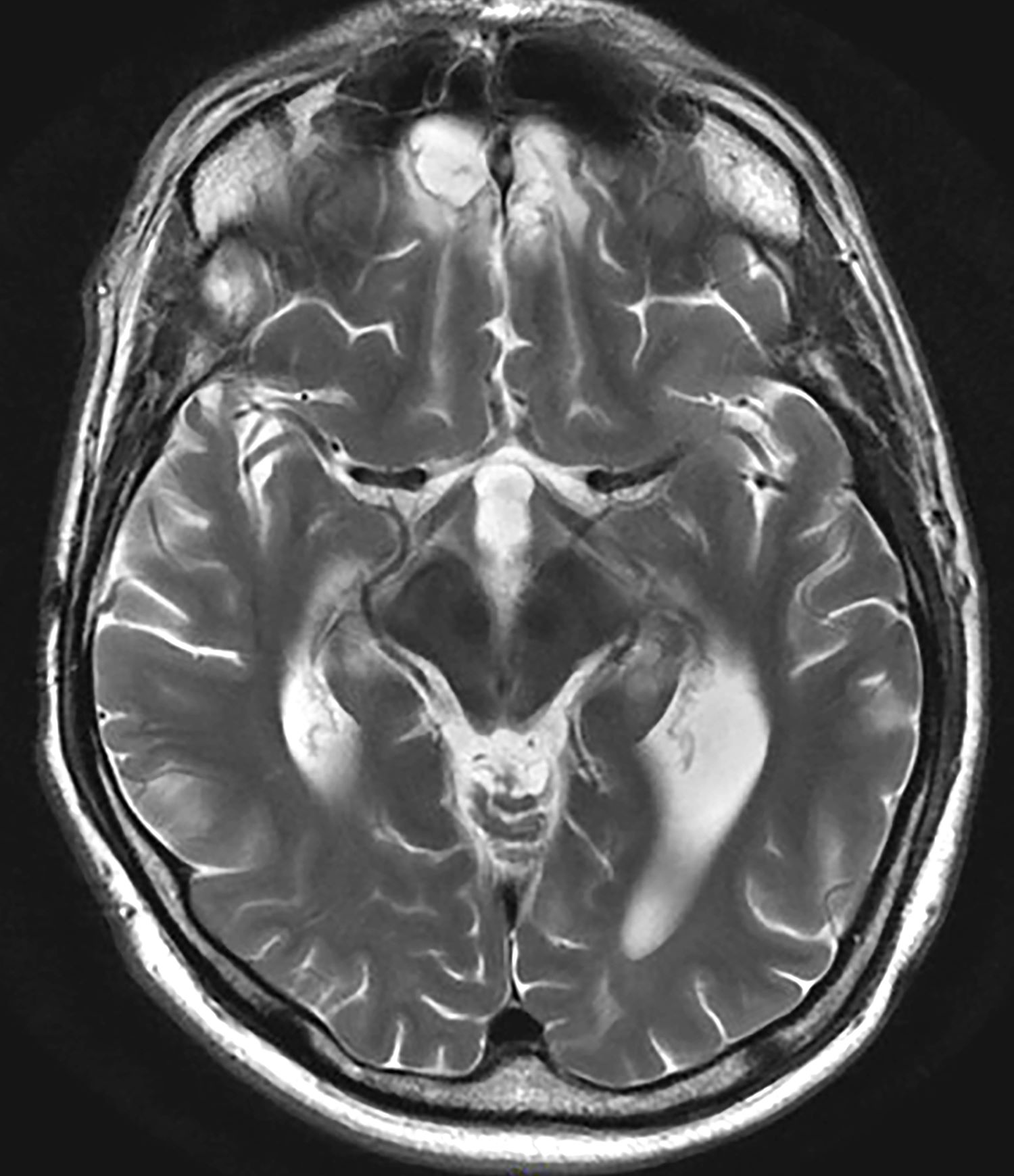

The correct diagnosis is adolescent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as the patient's symptoms — recurrent nightmares, flashbacks, hypervigilance, and avoidance behaviors — are closely linked to her recent traumatic experience, fitting the clinical profile of PTSD. The MRI finding, although abnormal, does not correlate with a neurologic cause for her symptoms and may be incidental.

Temporal lobe epilepsy can cause behavioral changes but does not explain the specific PTSD symptoms like flashbacks and nightmares.

Chronic migraine could explain the headaches but not the full spectrum of PTSD symptoms.

Major depressive disorder could account for some of the emotional and social symptoms but lacks the characteristic re-experiencing and avoidance behaviors typical of PTSD.

Adolescent PTSD is a significant public health concern, causing significant distress to a small portion of the youth population. By late adolescence, approximately two thirds of youths have been exposed to trauma, and 8% of these individuals meet the criteria for PTSD by age 18. The incidence is exceptionally high in cases of sexual abuse and assault, with rates reaching up to 40%. PTSD in adolescents is associated with severe psychological distress, reduced academic performance, and a high rate of comorbidities, including anxiety and depression. There are specific populations (including children who are evacuated from home, asylum seekers, etc.) that show higher rates of PTSD.

PTSD can lead to chronic impairments, comorbid psychiatric disorders, and an increased risk for suicide, with cases documented in toddlers as young as 1 year old. Thus, it is important to consider the individual's background and social history, as older children with PTSD may present with symptoms from early childhood trauma, often distant from the time of clinical evaluation.

Intrusion symptoms are a hallmark of PTSD, characterized by persistent and uncontrollable thoughts, dreams, and emotional reactions related to the traumatic event. These symptoms distinguish PTSD from other anxiety and mood disorders. Children with PTSD often experience involuntary, distressing thoughts and memories triggered by trauma cues, such as sights, sounds, or smells associated with the traumatic event. In younger children, these intrusive thoughts may manifest through repetitive play that re-enacts aspects of the trauma.

Nightmares are also common, although in children the content may not always directly relate to the traumatic event. Chronic nightmares contribute to sleep disturbances, exacerbating PTSD symptoms. Trauma reminders, which can be both internal (thoughts, memories) and external (places, sensory experiences), can provoke severe distress and physiologic reactions.

Avoidance symptoms often develop as a coping mechanism in response to distressing re-experiencing symptoms. Children may avoid thoughts, feelings, and memories of the traumatic event or people, places, and activities associated with the trauma. In young children, avoidance may manifest as restricted play or reduced exploration of their environment.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) outlines specific criteria for diagnosing PTSD in individuals over 6 years old, which includes exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence, and the presence of symptoms such as intrusion, avoidance, negative mood alterations, and heightened arousal. The DSM-5-TR provides tailored diagnostic criteria for developmental differences in symptom expression for children under 6.

Managing PTSD in children requires a patient-specific approach, with an emphasis on obtaining consent from both the patient and guardian. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) recommends psychotherapy as the first-line treatment for pediatric PTSD. However, patients with severe symptoms or comorbidities may initially be unable to engage in meaningful therapy and may require medication to stabilize symptoms before starting psychotherapy.

Trauma-focused psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure-based therapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, is the preferred treatment for PTSD. Clinical studies have shown that patients receiving trauma-focused psychotherapy experience more remarkable symptom improvement than those who do not receive treatment and, in children, psychotherapy generally yields better outcomes than pharmacotherapy.

While selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors like sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for PTSD treatment in adults, their efficacy in children often produces outcomes similar to those of placebo. Medications are typically reserved for severe symptoms and are used as an off-label treatment in pediatric cases. Pharmacologic management may be necessary when the severity of symptoms prevents the use of trauma-focused psychotherapy or requires immediate stabilization.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The correct diagnosis is adolescent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as the patient's symptoms — recurrent nightmares, flashbacks, hypervigilance, and avoidance behaviors — are closely linked to her recent traumatic experience, fitting the clinical profile of PTSD. The MRI finding, although abnormal, does not correlate with a neurologic cause for her symptoms and may be incidental.

Temporal lobe epilepsy can cause behavioral changes but does not explain the specific PTSD symptoms like flashbacks and nightmares.

Chronic migraine could explain the headaches but not the full spectrum of PTSD symptoms.

Major depressive disorder could account for some of the emotional and social symptoms but lacks the characteristic re-experiencing and avoidance behaviors typical of PTSD.

Adolescent PTSD is a significant public health concern, causing significant distress to a small portion of the youth population. By late adolescence, approximately two thirds of youths have been exposed to trauma, and 8% of these individuals meet the criteria for PTSD by age 18. The incidence is exceptionally high in cases of sexual abuse and assault, with rates reaching up to 40%. PTSD in adolescents is associated with severe psychological distress, reduced academic performance, and a high rate of comorbidities, including anxiety and depression. There are specific populations (including children who are evacuated from home, asylum seekers, etc.) that show higher rates of PTSD.

PTSD can lead to chronic impairments, comorbid psychiatric disorders, and an increased risk for suicide, with cases documented in toddlers as young as 1 year old. Thus, it is important to consider the individual's background and social history, as older children with PTSD may present with symptoms from early childhood trauma, often distant from the time of clinical evaluation.

Intrusion symptoms are a hallmark of PTSD, characterized by persistent and uncontrollable thoughts, dreams, and emotional reactions related to the traumatic event. These symptoms distinguish PTSD from other anxiety and mood disorders. Children with PTSD often experience involuntary, distressing thoughts and memories triggered by trauma cues, such as sights, sounds, or smells associated with the traumatic event. In younger children, these intrusive thoughts may manifest through repetitive play that re-enacts aspects of the trauma.

Nightmares are also common, although in children the content may not always directly relate to the traumatic event. Chronic nightmares contribute to sleep disturbances, exacerbating PTSD symptoms. Trauma reminders, which can be both internal (thoughts, memories) and external (places, sensory experiences), can provoke severe distress and physiologic reactions.

Avoidance symptoms often develop as a coping mechanism in response to distressing re-experiencing symptoms. Children may avoid thoughts, feelings, and memories of the traumatic event or people, places, and activities associated with the trauma. In young children, avoidance may manifest as restricted play or reduced exploration of their environment.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) outlines specific criteria for diagnosing PTSD in individuals over 6 years old, which includes exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence, and the presence of symptoms such as intrusion, avoidance, negative mood alterations, and heightened arousal. The DSM-5-TR provides tailored diagnostic criteria for developmental differences in symptom expression for children under 6.

Managing PTSD in children requires a patient-specific approach, with an emphasis on obtaining consent from both the patient and guardian. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) recommends psychotherapy as the first-line treatment for pediatric PTSD. However, patients with severe symptoms or comorbidities may initially be unable to engage in meaningful therapy and may require medication to stabilize symptoms before starting psychotherapy.

Trauma-focused psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure-based therapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, is the preferred treatment for PTSD. Clinical studies have shown that patients receiving trauma-focused psychotherapy experience more remarkable symptom improvement than those who do not receive treatment and, in children, psychotherapy generally yields better outcomes than pharmacotherapy.

While selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors like sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for PTSD treatment in adults, their efficacy in children often produces outcomes similar to those of placebo. Medications are typically reserved for severe symptoms and are used as an off-label treatment in pediatric cases. Pharmacologic management may be necessary when the severity of symptoms prevents the use of trauma-focused psychotherapy or requires immediate stabilization.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The correct diagnosis is adolescent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as the patient's symptoms — recurrent nightmares, flashbacks, hypervigilance, and avoidance behaviors — are closely linked to her recent traumatic experience, fitting the clinical profile of PTSD. The MRI finding, although abnormal, does not correlate with a neurologic cause for her symptoms and may be incidental.

Temporal lobe epilepsy can cause behavioral changes but does not explain the specific PTSD symptoms like flashbacks and nightmares.

Chronic migraine could explain the headaches but not the full spectrum of PTSD symptoms.

Major depressive disorder could account for some of the emotional and social symptoms but lacks the characteristic re-experiencing and avoidance behaviors typical of PTSD.

Adolescent PTSD is a significant public health concern, causing significant distress to a small portion of the youth population. By late adolescence, approximately two thirds of youths have been exposed to trauma, and 8% of these individuals meet the criteria for PTSD by age 18. The incidence is exceptionally high in cases of sexual abuse and assault, with rates reaching up to 40%. PTSD in adolescents is associated with severe psychological distress, reduced academic performance, and a high rate of comorbidities, including anxiety and depression. There are specific populations (including children who are evacuated from home, asylum seekers, etc.) that show higher rates of PTSD.

PTSD can lead to chronic impairments, comorbid psychiatric disorders, and an increased risk for suicide, with cases documented in toddlers as young as 1 year old. Thus, it is important to consider the individual's background and social history, as older children with PTSD may present with symptoms from early childhood trauma, often distant from the time of clinical evaluation.

Intrusion symptoms are a hallmark of PTSD, characterized by persistent and uncontrollable thoughts, dreams, and emotional reactions related to the traumatic event. These symptoms distinguish PTSD from other anxiety and mood disorders. Children with PTSD often experience involuntary, distressing thoughts and memories triggered by trauma cues, such as sights, sounds, or smells associated with the traumatic event. In younger children, these intrusive thoughts may manifest through repetitive play that re-enacts aspects of the trauma.

Nightmares are also common, although in children the content may not always directly relate to the traumatic event. Chronic nightmares contribute to sleep disturbances, exacerbating PTSD symptoms. Trauma reminders, which can be both internal (thoughts, memories) and external (places, sensory experiences), can provoke severe distress and physiologic reactions.

Avoidance symptoms often develop as a coping mechanism in response to distressing re-experiencing symptoms. Children may avoid thoughts, feelings, and memories of the traumatic event or people, places, and activities associated with the trauma. In young children, avoidance may manifest as restricted play or reduced exploration of their environment.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) outlines specific criteria for diagnosing PTSD in individuals over 6 years old, which includes exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence, and the presence of symptoms such as intrusion, avoidance, negative mood alterations, and heightened arousal. The DSM-5-TR provides tailored diagnostic criteria for developmental differences in symptom expression for children under 6.

Managing PTSD in children requires a patient-specific approach, with an emphasis on obtaining consent from both the patient and guardian. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) recommends psychotherapy as the first-line treatment for pediatric PTSD. However, patients with severe symptoms or comorbidities may initially be unable to engage in meaningful therapy and may require medication to stabilize symptoms before starting psychotherapy.

Trauma-focused psychotherapy, including cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), exposure-based therapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, is the preferred treatment for PTSD. Clinical studies have shown that patients receiving trauma-focused psychotherapy experience more remarkable symptom improvement than those who do not receive treatment and, in children, psychotherapy generally yields better outcomes than pharmacotherapy.

While selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors like sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for PTSD treatment in adults, their efficacy in children often produces outcomes similar to those of placebo. Medications are typically reserved for severe symptoms and are used as an off-label treatment in pediatric cases. Pharmacologic management may be necessary when the severity of symptoms prevents the use of trauma-focused psychotherapy or requires immediate stabilization.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 15-year-old girl presented to the emergency department with complaints of persistent headaches, nightmares, and difficulty concentrating in school over the past 3 months. The patient had recently experienced a traumatic event, a severe car accident in which a close friend was critically injured. Since the incident, the patient has been exhibiting increased irritability, avoidance of activities that she previously enjoyed, and a noticeable withdrawal from social interactions. Additionally, she reported recurrent flashbacks to the accident, often triggered by sounds resembling car engines. On physical examination, the patient appeared anxious and exhibited hypervigilance. An MRI of the brain was performed to rule out any organic causes of her symptoms, revealing an area of increased signal intensity in the left cerebellar hemisphere (as highlighted in the image).

An Rx for Burnout, Grief, and Illness: Dance

In 2012, Tara Rynders’ sister was diagnosed with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. For Ms. Rynders, a registered nurse in Denver, Colorado, the news was devastating.

“She was this beautiful 26-year-old woman, strong and healthy, and within 12 hours, she went into a coma and couldn’t move or speak,” Ms. Rynders remembered. She flew to her sister in Reno, Nevada, and moved into her intensive care unit room. The helplessness she felt wasn’t just as a sister, but as a healthcare provider.

“As a nurse, we love to fix things,” Ms. Rynders said. “But when my sister was sick, I couldn’t do anything to fix her. The doctors didn’t even know what was going on.”

When Ms. Rynders’ sister woke from the coma, she couldn’t speak. The only comfort Ms. Rynders could provide was her presence and the ability to put a smile on her sister’s face. So, Ms. Rynders did what came naturally ...

She danced.

In that tiny hospital room, she blasted her sister’s favorite song — “Party in the U.S.A.” by Miley Cyrus — and danced around the room, doing anything she could to make her sister laugh.

And this patient who could not form words found her voice.

“She’d holler so deeply, it almost sounded like she was crying,” Ms. Rynders remembered. “The depths of her grief and the depths of her joy coming out simultaneously. It was really amazing and so healing for both of us.”

Do You Know How Powerful Dancing Really Is?

Ms. Rynders is far from the only healthcare professional who’s discovered the healing power of dance. In recent years, doctors and nurses across the country, from Los Angeles, California, to Atlanta, Georgia; from TikTok’s “Dancing Nurse,” Cindy Jones, to Max Chiu, Nebraska’s breakdancing oncologist, have demonstrated that finding new ways to move your body isn’t just good advice for patients but could be exactly what healthcare providers need to stay mentally and physically healthy.

It comes at a time when the field faces a “mental health crisis,” according to a 2023 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024 found current rates of 49% for burnout and 20% for depression.

And medical professionals are often hesitant about seeking help. Nearly 40% of physicians reported reluctance to seek out mental health treatment over fears of professional repercussions, according to 2024 recommendations by the Mayo Clinic.

The solution? It just might be dancing.

There’s ample evidence. A 2024 study from the University of Sydney, Australia, found that dancing offers more psychological and cognitive benefits — helping with everything from depression to motivation to emotional well-being — than any other type of exercise.

Another study, published in February by

Structured dance, where you learn specific movements, can offer a huge boost to mental health, according to a 2024 University of Sydney study. But so does unchoreographed dancing, where you’re basically just letting your limbs do their own thing. A 2021 study, published in Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, found that 95% of dancers who just moved their bodies, regardless of how it looked to the outside world, still had huge benefits with depression, anxiety, and trauma.

How to Turn a Mastectomy Into a Dance Party

Deborah Cohan, MD, 55, an obstetrician at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center, San Francisco, California, discovered firsthand the power of dance back in 2013. After finding a lump in her breast during a self-exam, Dr. Cohan feared the worst. Days later, her radiologist confirmed she had invasive ductal carcinoma.

“It was a complete shock,” Dr. Cohan remembered. “I took care of myself. I ate right. I had no obvious risk factors. I did work the night shift, and there’s actually an increased risk for breast cancer among ob.gyn. workers who do night shift work. But still, it took me completely by surprise. My kids were 5 and 8 at the time, and I was terrified that they’d grow up without a mom.”

So, Dr. Cohan turned to the only thing that gave her comfort — dance class. Dancing had been an escape for Dr. Cohan since she took her first ballet class at age 3. So, she skipped work and went to her weekly Soul Motion dance class, where she found herself doing the exact opposite of escaping. She embraced her fears.

“I visualized death as a dance partner,” Dr. Cohan said. “I felt a freedom come over my body. It didn’t make sense to me at the time, but it was almost joyful. Not that I was accepting death or anticipating death, but just that I acknowledged its presence. There’s so much pressure among people with cancer to be positive. [But] that’s something that needs to come from within a person, not from outside. Nobody can dictate how someone should be feeling. And as I danced, I was genuinely feeling joy even as I recognized my own fears and didn’t turn away from them. I was experiencing all the emotions at once. It was such a relief to realize this wasn’t all going to be about sadness.”

The experience was so healing for Dr. Cohan that she decided to see if she could bring those same feelings into her bilateral mastectomy. When meeting with her surgical team, Dr. Cohan made an unorthodox request: Could her pre-op include a dance party?

“I asked the anesthesiologist in the pre-op appointment if I could dance, and he said yes,” she remembered, laughing. “And then I checked with the surgeon, and he said yes. And then I asked the perioperative nurse, and he said yes, ‘but only if you don’t make me dance, too’. So somehow it all came together.”

Dr. Cohan decided on the Beyoncé song “Get Me Bodied,” which she says resonated with her because “it’s all about being in your body and being your full self. I was like, that is exactly how I want to show up in the operating room.” The moment the music kicked in and Dr. Cohan broke into dance, all of her stress melted away.

“Even though I’d been given permission to dance, I never expected anybody else to join in,” Dr. Cohan said. But that’s exactly what they did. A friend took a video, which shows Dr. Cohan in a hospital gown and bouffant cap, dancing alongside her surgical and anesthesia teams, all of whom are dressed in scrubs, at Mount Zion Hospital in San Francisco, California.

“It’s weird to say, especially about a mastectomy,” Dr. Cohan said, “but it was one of the most joyful moments of my life.”

The video’s been viewed 8.4 million times and is so inspirational — we dare you to watch it and not want to jump out of your chair to dance — that soon others were following Dr. Cohan’s lead.

- Sixteen-year-old Amari Hall danced to celebrate her successful heart transplant.

- Ana-Alecia Ayala, a 32-year-old uterine cancer survivor, danced along to “Juju on That Beat” to make chemotherapy more tolerable.

- Doreta Norris, a patient with breast cancer, chose “Gangnam Style” to serenade her into surgery.

Bringing Dance to Other Medical Pros

Ms. Rynders realized the true power of dance years before her sister’s illness, when her mother died of cancer. “I’ve always considered myself to be very resilient as a human, but I couldn’t bounce back after my mom died,” she said. “I was nursing full time in the emergency room, and I was sad all the time. And then one day I realized, you know what brings me joy? It’s always been dance.”

She went back to school to get her Master of Fine Arts in Dance from the University of Colorado at Boulder, which she believes helped her heal. “I was actually able to grieve instead of just pretending I was okay,” she said.

Inspired by these experiences, Ms. Rynders founded The Clinic in 2017, a company that provides dance workshops for healthcare professionals struggling with burnout and secondary traumatic stress.

“I see these nurses running down hospital hallways, covered in blood from patients whose lives are literally hanging on a thread,” she said. “They’re dealing with so much stress and grief and hardship. And then to see them with us, playing and laughing — those deep belly laughs that you haven’t done since you were a kid, the deep laughing that comes from deep in your soul. It can be transformational, for them and for you.”

Ms. Rynders remembers one especially healing workshop in which the participants pretended to be astronauts in deep space, using zero gravity to inform their movements. After the exercise, a veteran hospital nurse took Ms. Rynders aside to thank her, mentioning that she was still dealing with grief for her late son, who had died from suicide years earlier.

“She had a lot of guilt around it,” Ms. Rynders remembered. “And she said to me, ‘When I went to space, I felt closer to him.’ It was just this silly little game, but it gave her this lightness that she hadn’t felt in years. She was able to be free and laugh and play and feel close to her son again.”

Good Medicine

Dr. Cohan, who today is cancer free, said her experience made her completely rethink her relationship with patients. She has danced with more than a few of them, though she’s careful never to force it on them. “I never want to project my idea of joy onto others,” she said. “But more than anything, it’s changed my thinking on what it means to take ownership as a patient.”

The one thing Dr. Cohan never wanted as a patient, and the thing she never wants for her own patients, is the loss of agency. “When I danced, I didn’t feel like I was just handing over my body and begrudgingly accepting what was about to happen to me,” she said. “I was taking ownership around my decision, and I felt connected, really connected, to my surgical team.”

As a patient, Dr. Cohan experienced what she calls the “regimented” atmosphere of medicine. “You’re told where to go, what to do, and you have no control over any of it,” recalled Dr. Cohan, who’s now semiretired and runs retreats for women with breast cancer. “But by bringing in dance, it felt really radical that my healthcare team was doing my thing, not the other way around.”

(Re)Learning to Move More Consciously

Healthcare providers need these moments of escape just as much as patients living with disease. The difference is, as Ms. Rynders points out, those in the medical field aren’t always as aware of their emotional distress. “I think if you ask a nurse, ‘How can I help you? What do you need?’ They’re usually like, ‘I don’t know. I don’t even know what I need,’ ” Ms. Rynders said. “Even if they did know what they needed, I think it’s hard to ask for it and even harder to receive it.”

At Ms. Rynders’ workshops, not everybody is comfortable dancing, of course. So, new participants are always given the option just to witness, to be in the room and watch what happens. “But I also really encourage people to take advantage of this opportunity to do something different and disrupt the way we live on a daily basis,” Ms. Rynders said. “Let your brain try something new and be courageous. We’ve only had a few people who sat on the sidelines the whole time.”

It’s not always just about feelings, Dr. Cohan added, but physical relaxation. “Sometimes it’s just about remembering how to move consciously. When I was having surgery, I didn’t just dance to relax myself. I wanted my entire surgical team to be relaxed.”

For Ms. Rynders, every time she dances with her patients, or with fellow healthcare workers, she’s reminded of her sister and the comfort she was able to give her when no amount of medicine would make things better.

“We don’t always need to be fixed by things,” she said. “Sometimes we just need to be present with one another and be with each other. And sometimes, the best way to do that is by dancing till the tears roll down your cheeks.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2012, Tara Rynders’ sister was diagnosed with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. For Ms. Rynders, a registered nurse in Denver, Colorado, the news was devastating.

“She was this beautiful 26-year-old woman, strong and healthy, and within 12 hours, she went into a coma and couldn’t move or speak,” Ms. Rynders remembered. She flew to her sister in Reno, Nevada, and moved into her intensive care unit room. The helplessness she felt wasn’t just as a sister, but as a healthcare provider.

“As a nurse, we love to fix things,” Ms. Rynders said. “But when my sister was sick, I couldn’t do anything to fix her. The doctors didn’t even know what was going on.”

When Ms. Rynders’ sister woke from the coma, she couldn’t speak. The only comfort Ms. Rynders could provide was her presence and the ability to put a smile on her sister’s face. So, Ms. Rynders did what came naturally ...

She danced.

In that tiny hospital room, she blasted her sister’s favorite song — “Party in the U.S.A.” by Miley Cyrus — and danced around the room, doing anything she could to make her sister laugh.

And this patient who could not form words found her voice.

“She’d holler so deeply, it almost sounded like she was crying,” Ms. Rynders remembered. “The depths of her grief and the depths of her joy coming out simultaneously. It was really amazing and so healing for both of us.”

Do You Know How Powerful Dancing Really Is?

Ms. Rynders is far from the only healthcare professional who’s discovered the healing power of dance. In recent years, doctors and nurses across the country, from Los Angeles, California, to Atlanta, Georgia; from TikTok’s “Dancing Nurse,” Cindy Jones, to Max Chiu, Nebraska’s breakdancing oncologist, have demonstrated that finding new ways to move your body isn’t just good advice for patients but could be exactly what healthcare providers need to stay mentally and physically healthy.

It comes at a time when the field faces a “mental health crisis,” according to a 2023 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024 found current rates of 49% for burnout and 20% for depression.

And medical professionals are often hesitant about seeking help. Nearly 40% of physicians reported reluctance to seek out mental health treatment over fears of professional repercussions, according to 2024 recommendations by the Mayo Clinic.

The solution? It just might be dancing.

There’s ample evidence. A 2024 study from the University of Sydney, Australia, found that dancing offers more psychological and cognitive benefits — helping with everything from depression to motivation to emotional well-being — than any other type of exercise.

Another study, published in February by

Structured dance, where you learn specific movements, can offer a huge boost to mental health, according to a 2024 University of Sydney study. But so does unchoreographed dancing, where you’re basically just letting your limbs do their own thing. A 2021 study, published in Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, found that 95% of dancers who just moved their bodies, regardless of how it looked to the outside world, still had huge benefits with depression, anxiety, and trauma.

How to Turn a Mastectomy Into a Dance Party

Deborah Cohan, MD, 55, an obstetrician at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center, San Francisco, California, discovered firsthand the power of dance back in 2013. After finding a lump in her breast during a self-exam, Dr. Cohan feared the worst. Days later, her radiologist confirmed she had invasive ductal carcinoma.

“It was a complete shock,” Dr. Cohan remembered. “I took care of myself. I ate right. I had no obvious risk factors. I did work the night shift, and there’s actually an increased risk for breast cancer among ob.gyn. workers who do night shift work. But still, it took me completely by surprise. My kids were 5 and 8 at the time, and I was terrified that they’d grow up without a mom.”

So, Dr. Cohan turned to the only thing that gave her comfort — dance class. Dancing had been an escape for Dr. Cohan since she took her first ballet class at age 3. So, she skipped work and went to her weekly Soul Motion dance class, where she found herself doing the exact opposite of escaping. She embraced her fears.

“I visualized death as a dance partner,” Dr. Cohan said. “I felt a freedom come over my body. It didn’t make sense to me at the time, but it was almost joyful. Not that I was accepting death or anticipating death, but just that I acknowledged its presence. There’s so much pressure among people with cancer to be positive. [But] that’s something that needs to come from within a person, not from outside. Nobody can dictate how someone should be feeling. And as I danced, I was genuinely feeling joy even as I recognized my own fears and didn’t turn away from them. I was experiencing all the emotions at once. It was such a relief to realize this wasn’t all going to be about sadness.”

The experience was so healing for Dr. Cohan that she decided to see if she could bring those same feelings into her bilateral mastectomy. When meeting with her surgical team, Dr. Cohan made an unorthodox request: Could her pre-op include a dance party?

“I asked the anesthesiologist in the pre-op appointment if I could dance, and he said yes,” she remembered, laughing. “And then I checked with the surgeon, and he said yes. And then I asked the perioperative nurse, and he said yes, ‘but only if you don’t make me dance, too’. So somehow it all came together.”

Dr. Cohan decided on the Beyoncé song “Get Me Bodied,” which she says resonated with her because “it’s all about being in your body and being your full self. I was like, that is exactly how I want to show up in the operating room.” The moment the music kicked in and Dr. Cohan broke into dance, all of her stress melted away.

“Even though I’d been given permission to dance, I never expected anybody else to join in,” Dr. Cohan said. But that’s exactly what they did. A friend took a video, which shows Dr. Cohan in a hospital gown and bouffant cap, dancing alongside her surgical and anesthesia teams, all of whom are dressed in scrubs, at Mount Zion Hospital in San Francisco, California.

“It’s weird to say, especially about a mastectomy,” Dr. Cohan said, “but it was one of the most joyful moments of my life.”

The video’s been viewed 8.4 million times and is so inspirational — we dare you to watch it and not want to jump out of your chair to dance — that soon others were following Dr. Cohan’s lead.

- Sixteen-year-old Amari Hall danced to celebrate her successful heart transplant.

- Ana-Alecia Ayala, a 32-year-old uterine cancer survivor, danced along to “Juju on That Beat” to make chemotherapy more tolerable.

- Doreta Norris, a patient with breast cancer, chose “Gangnam Style” to serenade her into surgery.

Bringing Dance to Other Medical Pros

Ms. Rynders realized the true power of dance years before her sister’s illness, when her mother died of cancer. “I’ve always considered myself to be very resilient as a human, but I couldn’t bounce back after my mom died,” she said. “I was nursing full time in the emergency room, and I was sad all the time. And then one day I realized, you know what brings me joy? It’s always been dance.”

She went back to school to get her Master of Fine Arts in Dance from the University of Colorado at Boulder, which she believes helped her heal. “I was actually able to grieve instead of just pretending I was okay,” she said.

Inspired by these experiences, Ms. Rynders founded The Clinic in 2017, a company that provides dance workshops for healthcare professionals struggling with burnout and secondary traumatic stress.

“I see these nurses running down hospital hallways, covered in blood from patients whose lives are literally hanging on a thread,” she said. “They’re dealing with so much stress and grief and hardship. And then to see them with us, playing and laughing — those deep belly laughs that you haven’t done since you were a kid, the deep laughing that comes from deep in your soul. It can be transformational, for them and for you.”

Ms. Rynders remembers one especially healing workshop in which the participants pretended to be astronauts in deep space, using zero gravity to inform their movements. After the exercise, a veteran hospital nurse took Ms. Rynders aside to thank her, mentioning that she was still dealing with grief for her late son, who had died from suicide years earlier.

“She had a lot of guilt around it,” Ms. Rynders remembered. “And she said to me, ‘When I went to space, I felt closer to him.’ It was just this silly little game, but it gave her this lightness that she hadn’t felt in years. She was able to be free and laugh and play and feel close to her son again.”

Good Medicine

Dr. Cohan, who today is cancer free, said her experience made her completely rethink her relationship with patients. She has danced with more than a few of them, though she’s careful never to force it on them. “I never want to project my idea of joy onto others,” she said. “But more than anything, it’s changed my thinking on what it means to take ownership as a patient.”

The one thing Dr. Cohan never wanted as a patient, and the thing she never wants for her own patients, is the loss of agency. “When I danced, I didn’t feel like I was just handing over my body and begrudgingly accepting what was about to happen to me,” she said. “I was taking ownership around my decision, and I felt connected, really connected, to my surgical team.”

As a patient, Dr. Cohan experienced what she calls the “regimented” atmosphere of medicine. “You’re told where to go, what to do, and you have no control over any of it,” recalled Dr. Cohan, who’s now semiretired and runs retreats for women with breast cancer. “But by bringing in dance, it felt really radical that my healthcare team was doing my thing, not the other way around.”

(Re)Learning to Move More Consciously

Healthcare providers need these moments of escape just as much as patients living with disease. The difference is, as Ms. Rynders points out, those in the medical field aren’t always as aware of their emotional distress. “I think if you ask a nurse, ‘How can I help you? What do you need?’ They’re usually like, ‘I don’t know. I don’t even know what I need,’ ” Ms. Rynders said. “Even if they did know what they needed, I think it’s hard to ask for it and even harder to receive it.”

At Ms. Rynders’ workshops, not everybody is comfortable dancing, of course. So, new participants are always given the option just to witness, to be in the room and watch what happens. “But I also really encourage people to take advantage of this opportunity to do something different and disrupt the way we live on a daily basis,” Ms. Rynders said. “Let your brain try something new and be courageous. We’ve only had a few people who sat on the sidelines the whole time.”

It’s not always just about feelings, Dr. Cohan added, but physical relaxation. “Sometimes it’s just about remembering how to move consciously. When I was having surgery, I didn’t just dance to relax myself. I wanted my entire surgical team to be relaxed.”

For Ms. Rynders, every time she dances with her patients, or with fellow healthcare workers, she’s reminded of her sister and the comfort she was able to give her when no amount of medicine would make things better.

“We don’t always need to be fixed by things,” she said. “Sometimes we just need to be present with one another and be with each other. And sometimes, the best way to do that is by dancing till the tears roll down your cheeks.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2012, Tara Rynders’ sister was diagnosed with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. For Ms. Rynders, a registered nurse in Denver, Colorado, the news was devastating.

“She was this beautiful 26-year-old woman, strong and healthy, and within 12 hours, she went into a coma and couldn’t move or speak,” Ms. Rynders remembered. She flew to her sister in Reno, Nevada, and moved into her intensive care unit room. The helplessness she felt wasn’t just as a sister, but as a healthcare provider.

“As a nurse, we love to fix things,” Ms. Rynders said. “But when my sister was sick, I couldn’t do anything to fix her. The doctors didn’t even know what was going on.”

When Ms. Rynders’ sister woke from the coma, she couldn’t speak. The only comfort Ms. Rynders could provide was her presence and the ability to put a smile on her sister’s face. So, Ms. Rynders did what came naturally ...

She danced.

In that tiny hospital room, she blasted her sister’s favorite song — “Party in the U.S.A.” by Miley Cyrus — and danced around the room, doing anything she could to make her sister laugh.

And this patient who could not form words found her voice.

“She’d holler so deeply, it almost sounded like she was crying,” Ms. Rynders remembered. “The depths of her grief and the depths of her joy coming out simultaneously. It was really amazing and so healing for both of us.”

Do You Know How Powerful Dancing Really Is?

Ms. Rynders is far from the only healthcare professional who’s discovered the healing power of dance. In recent years, doctors and nurses across the country, from Los Angeles, California, to Atlanta, Georgia; from TikTok’s “Dancing Nurse,” Cindy Jones, to Max Chiu, Nebraska’s breakdancing oncologist, have demonstrated that finding new ways to move your body isn’t just good advice for patients but could be exactly what healthcare providers need to stay mentally and physically healthy.

It comes at a time when the field faces a “mental health crisis,” according to a 2023 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Medscape Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2024 found current rates of 49% for burnout and 20% for depression.

And medical professionals are often hesitant about seeking help. Nearly 40% of physicians reported reluctance to seek out mental health treatment over fears of professional repercussions, according to 2024 recommendations by the Mayo Clinic.

The solution? It just might be dancing.

There’s ample evidence. A 2024 study from the University of Sydney, Australia, found that dancing offers more psychological and cognitive benefits — helping with everything from depression to motivation to emotional well-being — than any other type of exercise.

Another study, published in February by

Structured dance, where you learn specific movements, can offer a huge boost to mental health, according to a 2024 University of Sydney study. But so does unchoreographed dancing, where you’re basically just letting your limbs do their own thing. A 2021 study, published in Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, found that 95% of dancers who just moved their bodies, regardless of how it looked to the outside world, still had huge benefits with depression, anxiety, and trauma.

How to Turn a Mastectomy Into a Dance Party

Deborah Cohan, MD, 55, an obstetrician at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center, San Francisco, California, discovered firsthand the power of dance back in 2013. After finding a lump in her breast during a self-exam, Dr. Cohan feared the worst. Days later, her radiologist confirmed she had invasive ductal carcinoma.

“It was a complete shock,” Dr. Cohan remembered. “I took care of myself. I ate right. I had no obvious risk factors. I did work the night shift, and there’s actually an increased risk for breast cancer among ob.gyn. workers who do night shift work. But still, it took me completely by surprise. My kids were 5 and 8 at the time, and I was terrified that they’d grow up without a mom.”

So, Dr. Cohan turned to the only thing that gave her comfort — dance class. Dancing had been an escape for Dr. Cohan since she took her first ballet class at age 3. So, she skipped work and went to her weekly Soul Motion dance class, where she found herself doing the exact opposite of escaping. She embraced her fears.

“I visualized death as a dance partner,” Dr. Cohan said. “I felt a freedom come over my body. It didn’t make sense to me at the time, but it was almost joyful. Not that I was accepting death or anticipating death, but just that I acknowledged its presence. There’s so much pressure among people with cancer to be positive. [But] that’s something that needs to come from within a person, not from outside. Nobody can dictate how someone should be feeling. And as I danced, I was genuinely feeling joy even as I recognized my own fears and didn’t turn away from them. I was experiencing all the emotions at once. It was such a relief to realize this wasn’t all going to be about sadness.”

The experience was so healing for Dr. Cohan that she decided to see if she could bring those same feelings into her bilateral mastectomy. When meeting with her surgical team, Dr. Cohan made an unorthodox request: Could her pre-op include a dance party?

“I asked the anesthesiologist in the pre-op appointment if I could dance, and he said yes,” she remembered, laughing. “And then I checked with the surgeon, and he said yes. And then I asked the perioperative nurse, and he said yes, ‘but only if you don’t make me dance, too’. So somehow it all came together.”

Dr. Cohan decided on the Beyoncé song “Get Me Bodied,” which she says resonated with her because “it’s all about being in your body and being your full self. I was like, that is exactly how I want to show up in the operating room.” The moment the music kicked in and Dr. Cohan broke into dance, all of her stress melted away.

“Even though I’d been given permission to dance, I never expected anybody else to join in,” Dr. Cohan said. But that’s exactly what they did. A friend took a video, which shows Dr. Cohan in a hospital gown and bouffant cap, dancing alongside her surgical and anesthesia teams, all of whom are dressed in scrubs, at Mount Zion Hospital in San Francisco, California.

“It’s weird to say, especially about a mastectomy,” Dr. Cohan said, “but it was one of the most joyful moments of my life.”

The video’s been viewed 8.4 million times and is so inspirational — we dare you to watch it and not want to jump out of your chair to dance — that soon others were following Dr. Cohan’s lead.

- Sixteen-year-old Amari Hall danced to celebrate her successful heart transplant.

- Ana-Alecia Ayala, a 32-year-old uterine cancer survivor, danced along to “Juju on That Beat” to make chemotherapy more tolerable.

- Doreta Norris, a patient with breast cancer, chose “Gangnam Style” to serenade her into surgery.

Bringing Dance to Other Medical Pros

Ms. Rynders realized the true power of dance years before her sister’s illness, when her mother died of cancer. “I’ve always considered myself to be very resilient as a human, but I couldn’t bounce back after my mom died,” she said. “I was nursing full time in the emergency room, and I was sad all the time. And then one day I realized, you know what brings me joy? It’s always been dance.”

She went back to school to get her Master of Fine Arts in Dance from the University of Colorado at Boulder, which she believes helped her heal. “I was actually able to grieve instead of just pretending I was okay,” she said.

Inspired by these experiences, Ms. Rynders founded The Clinic in 2017, a company that provides dance workshops for healthcare professionals struggling with burnout and secondary traumatic stress.

“I see these nurses running down hospital hallways, covered in blood from patients whose lives are literally hanging on a thread,” she said. “They’re dealing with so much stress and grief and hardship. And then to see them with us, playing and laughing — those deep belly laughs that you haven’t done since you were a kid, the deep laughing that comes from deep in your soul. It can be transformational, for them and for you.”