User login

Desmoplastic Melanoma Masquerading as Neurofibroma

Desmoplastic melanoma (DMM) is a rare variant of melanoma that presents major challenges to both clinicians and pathologists.1 Clinically, the lesions may appear as subtle bland papules, nodules, or plaques. They can be easily mistaken for benign growths, leading to a delayed diagnosis. Consequently, most DMMs at the time of diagnosis tend to be thick, with a mean Breslow depth ranging from 2.0 to 6.5 mm.2 Histopathologic evaluation has its difficulties. At scanning magnification, these tumors may show low cellularity, mimicking a benign proliferation. It is well recognized that S-100 and other tumor markers lack specificity for DMM, which can be positive in a range of neural tumors and other cell types.2 In some amelanotic tumors, DMM becomes virtually indistinguishable from benign peripheral sheath tumors such as neurofribroma.3

Desmoplastic melanoma is exceedingly uncommon in the United States, with an estimated annual incidence rate of 2.0 cases per million.2 Typical locations of presentation include sun-exposed skin, with the head and neck regions representing more than half of reported cases.2 Desmoplastic melanoma largely is a disease of fair-skinned patients, with 95.5% of cases in the United States occurring in white non-Hispanic individuals. Advancing age, male gender, and head and neck location are associated with an increased risk for DMM-specific death.2 It is important that new or changing lesions in the correct cohort and location are biopsied promptly. We present this case to highlight the ongoing challenges of diagnosing DMM both clinically and histologically and to review the salient features of this often benign-appearing tumor.

Case Report

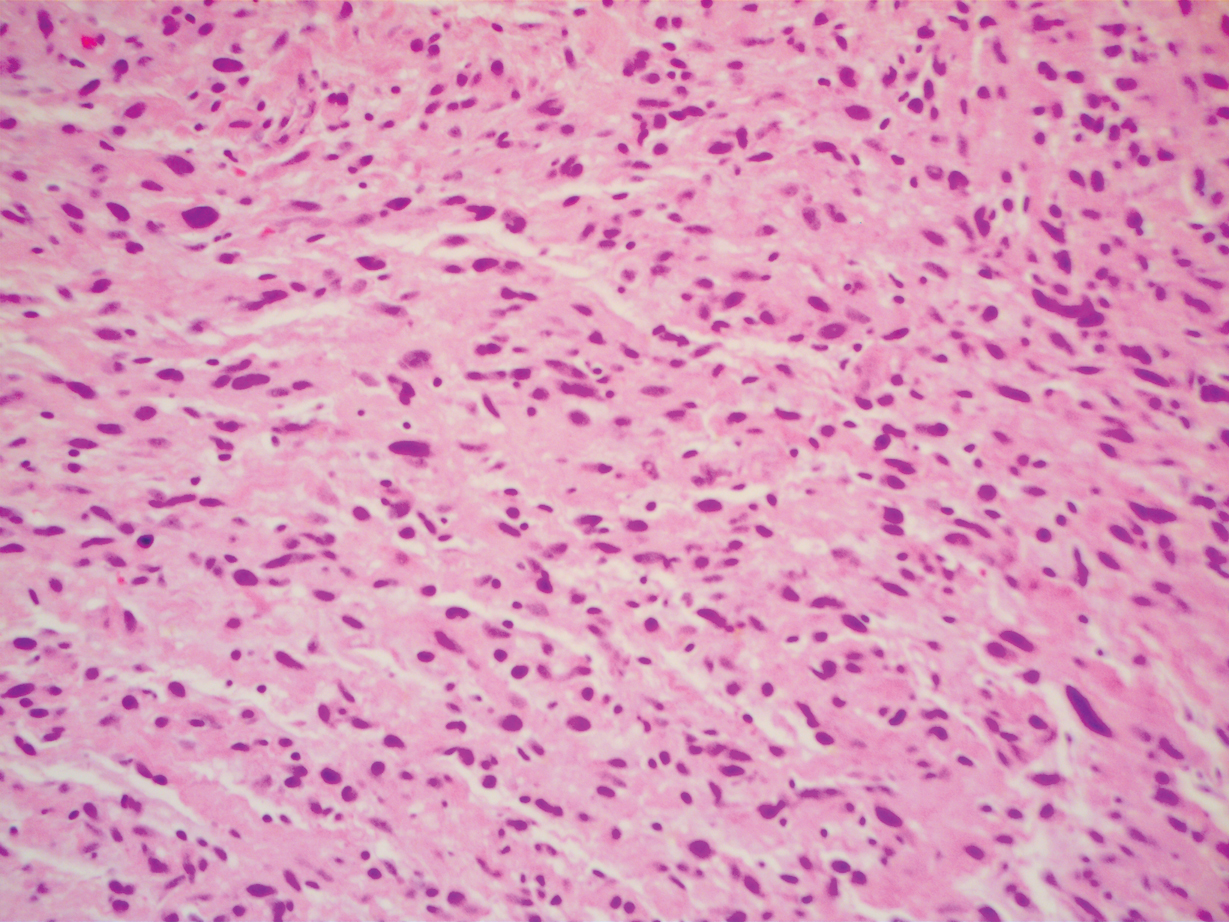

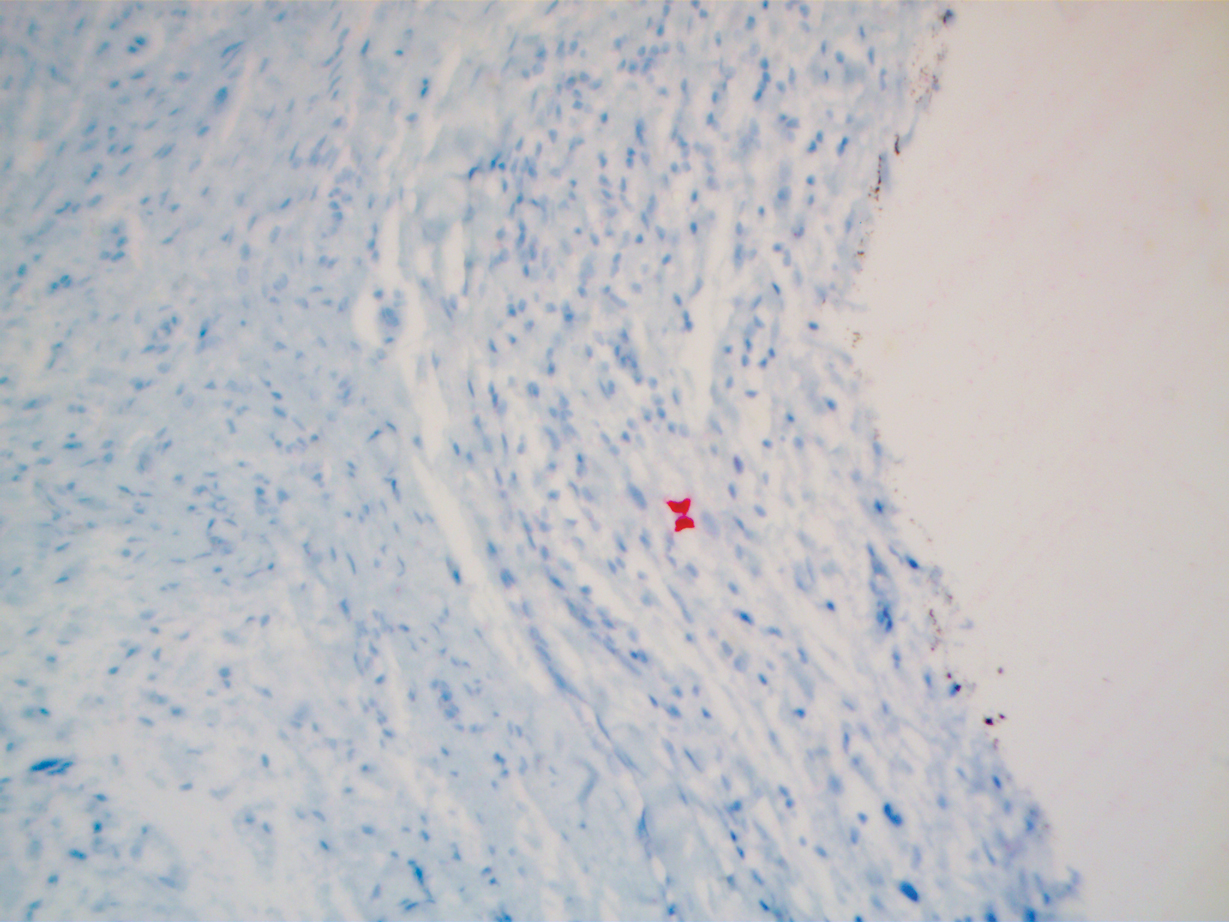

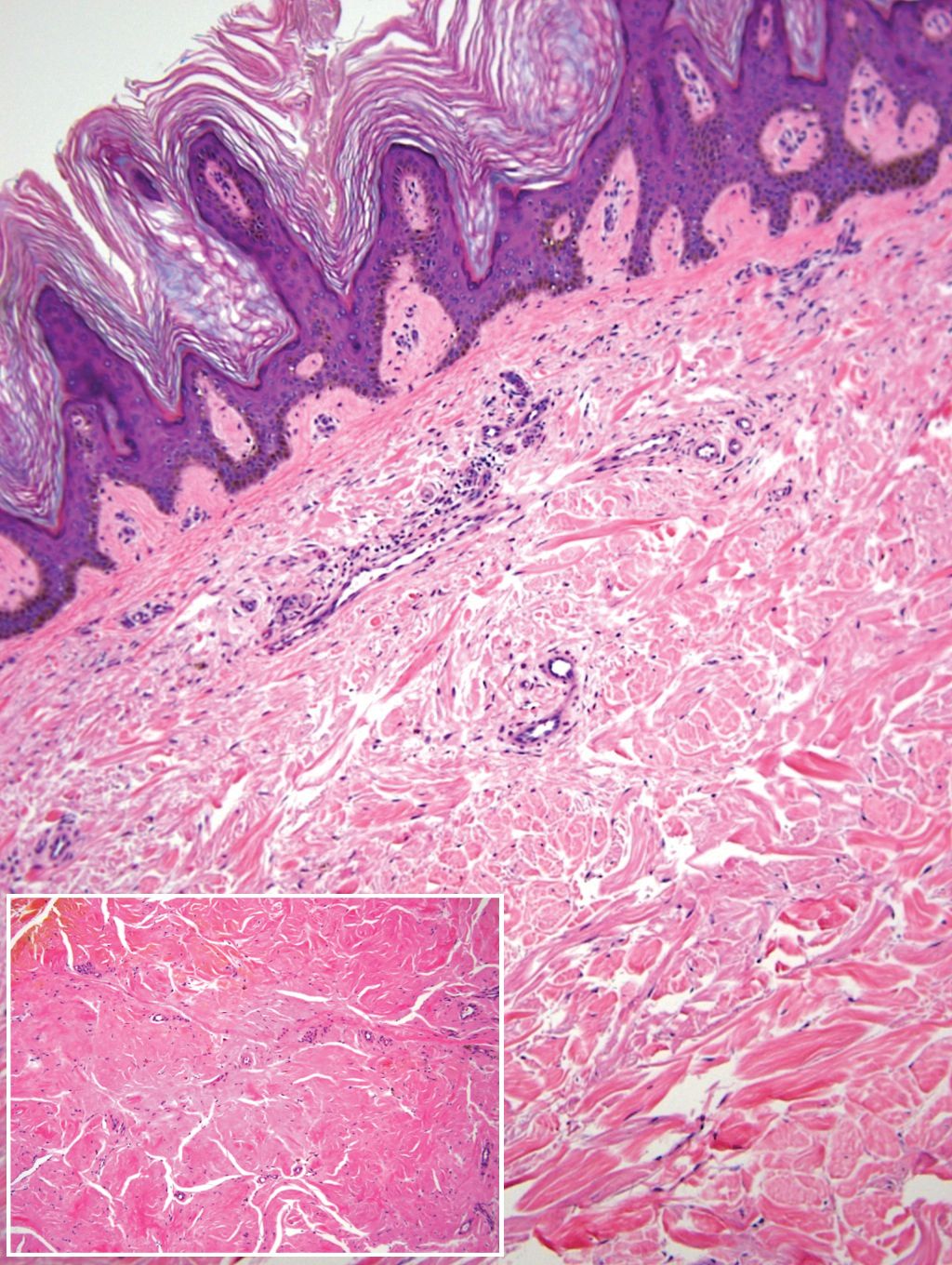

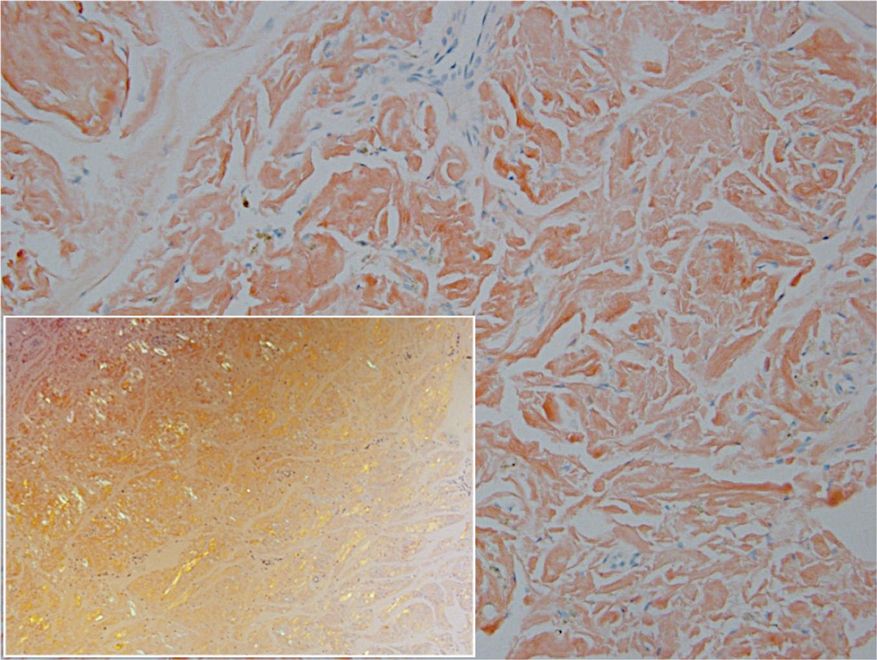

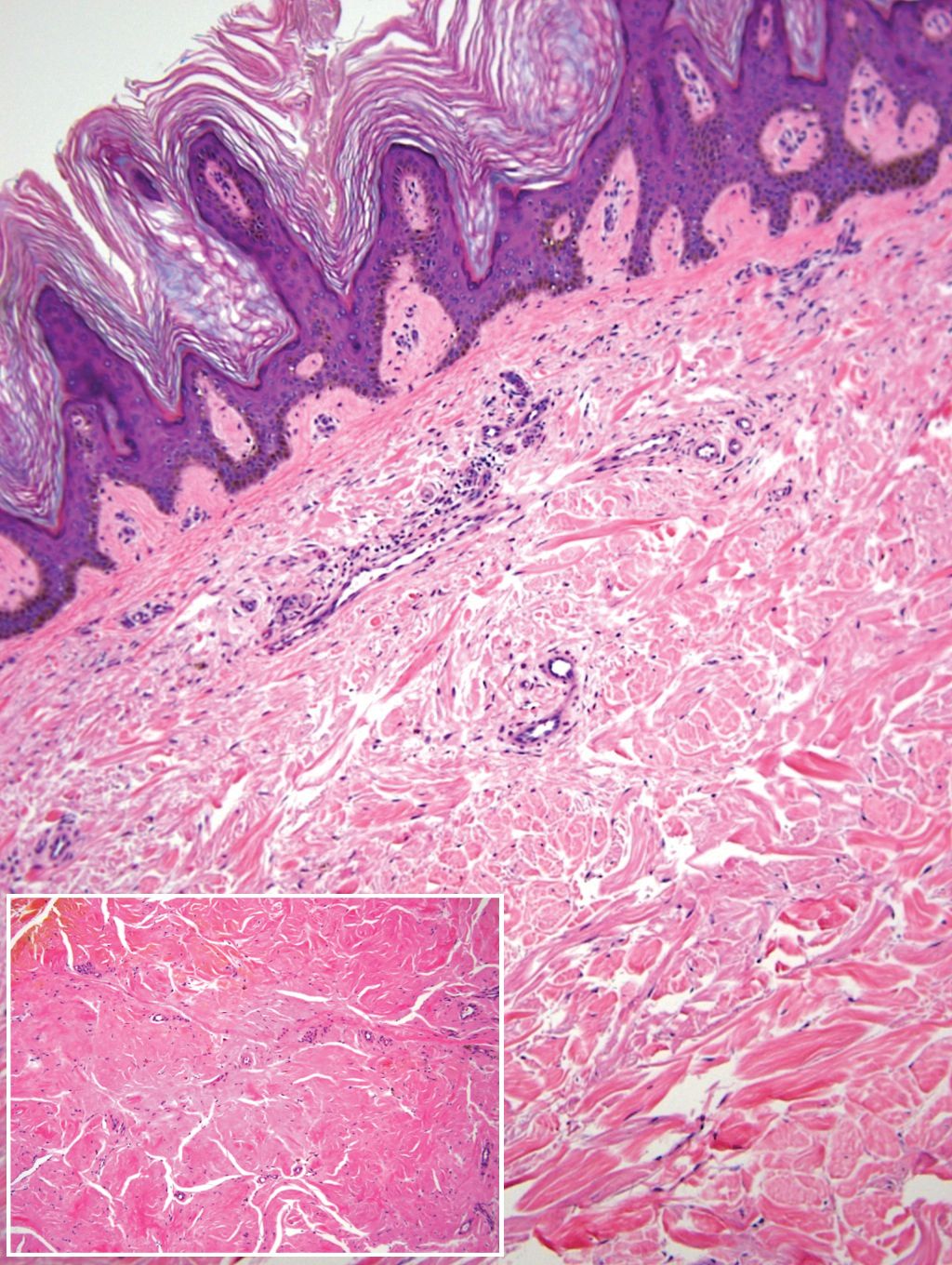

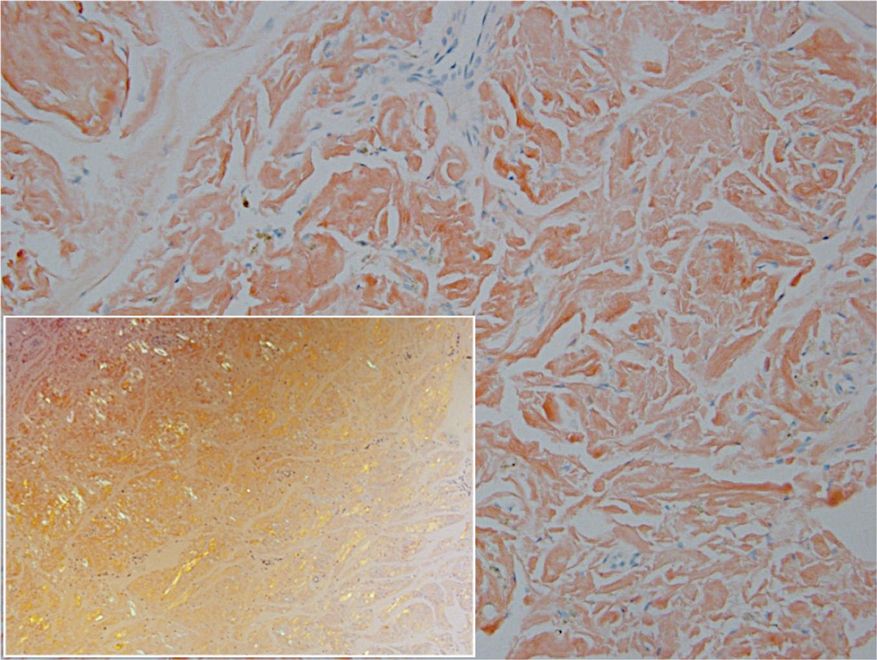

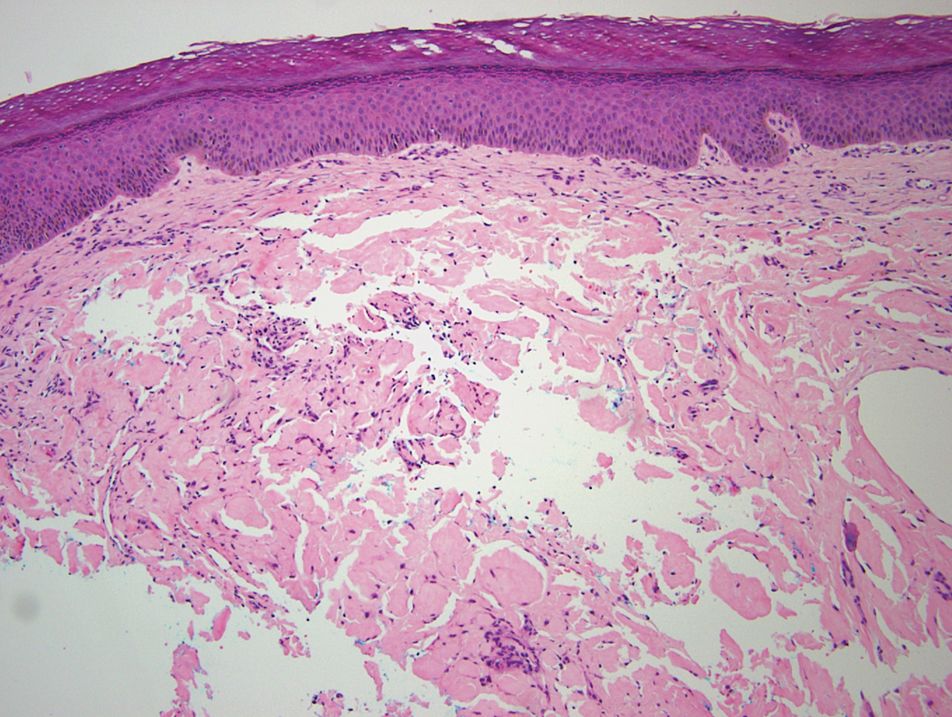

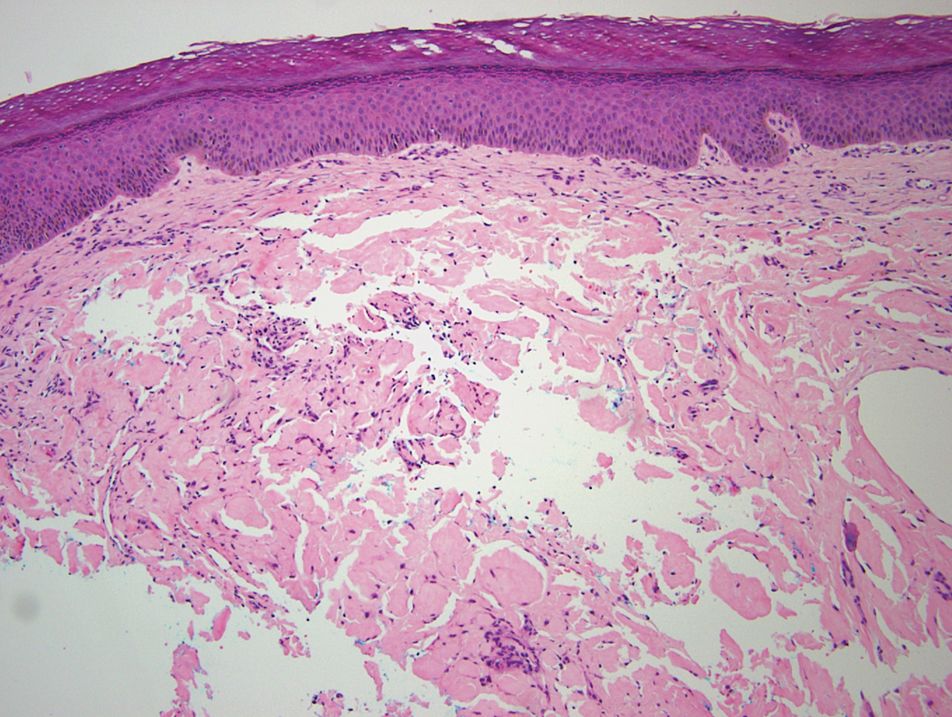

A 51-year-old White man with a history of prostate cancer, a personal and family history of melanoma, and benign neurofibromas presented with a 6-mm, pink, well-demarcated, soft papule on the left lateral neck (Figure 1). The lesion had been stable for many years but began growing more rapidly 1 to 2 years prior to presentation. The lesion was asymptomatic, and he denied changes in color or texture. There also was no bleeding or ulceration. A review of systems was unremarkable. A shave biopsy of the lesion revealed a nodular spindle cell tumor in the dermis resembling a neurofibroma on low power (Figure 2). However, overlying the tumor was a confluent proliferation positive for MART-1 and S-100, which was consistent with a diagnosis of melanoma in situ (Figure 3). Higher-power evaluation of the dermal proliferation showed both bland and hyperchromatic spindled and epithelioid cells (Figure 4), with rare mitotic figures highlighted by PHH3, an uncommon finding in neurofibromas (Figure 5). The dermal spindle cells were positive for S-100 and p75 and negative for Melan-A. Epithelial membrane antigen highlighted a faint sheath surrounding the dermal component. Ki-67 revealed a mildly increased proliferative index in the dermal component. The diagnosis of DMM was made after outside dermatopathology consultation was in agreement. However, the possibility of a melanoma in situ growing in association with an underlying neurofibroma remained a diagnostic consideration histologically. The lesion was widely excised.

Comment

Differential for DMM

Early DMMs may not show sufficient cytologic atypia to permit obvious distinction from neurofibromas, which becomes problematic when encountering a spindle cell proliferation within severely sun-damaged skin, or even more so when an intraepidermal population of melanocytes is situated above a dermal population of slender, spindled, S-100–positive cells, as seen in our patient.4 For these challenging scenarios, Yeh and McCalmont4 have proposed evaluating for a CD34 “fingerprint” pattern. This pattern typically is widespread in neurofibroma but absent or limited in DMM, and it is a useful adjunct in the differential diagnosis when conventional immunohistochemistry has little contribution.

There are several case reports in the literature of DMM mimicking other benign or malignant proliferations. In 2012, Jou et al5 described a case of a 62-year-old White man who presented with an oral nodule consistent with fibrous inflammatory hyperplasia clinically. Incisional biopsy later confirmed the diagnosis of amelanotic DMM.5 Similar case reports have been described in which the diagnosis of DMM was later found to resemble a sarcoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.6,7

Diagnosis of DMM

The prototypical DMM is an asymmetrical and deeply infiltrative spindle cell lesion in severely sun-damaged skin. By definition, the individual melanocytes are separated by connective tissue components, giving the tumor a paucicellular appearance.1 Although the low cellularity can give a deceptively bland scanning aspect, on high-power examination there usually are identifiable atypical spindled cells with enlarged, elongated, and hyperchromatic nuclei. S-100 typically is diffusely positive in DMM, though occasional cases show more limited staining.8 Other commonly used and more specific markers of melanocytic differentiation, including HMB45 and Melan-A, typically are negative in the paucicellular spindle cell components.9 Desmoplastic melanoma can be further categorized by the degree of fibrosis within a particular tumor. If fibrosis is prominent throughout the entire tumor, it is named pure DMM. On the other hand, fibrosis may only represent a portion of an otherwise nondesmoplastic melanoma, which is known as combined DMM.10

Conclusion

We present this case to highlight the ongoing challenges of diagnosing DMM both clinically and histologically. Although a bland-appearing lesion, key clinical features prompting a biopsy in our patient included recent growth of the lesion, a personal history of melanoma, the patient’s fair skin type, a history of heavy sun exposure, and the location of the lesion. According to Busam,11 an associated melanoma in situ component is identified in 80% to 85% of DMM cases. Detection of a melanoma in situ component associated with a malignant spindle cell tumor can help establish the diagnosis of DMM. In the absence of melanoma in situ, a strong diffuse immunoreactivity for S-100 and lack of epithelial markers support the diagnosis.11 After review of the literature, our case likely represents DMM as opposed to a melanoma in situ developing within a neurofibroma.

- Wood BA. Desmoplastic melanoma: recent advances and persisting challenges. Pathology. 2013;45:453-463.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- Machado I, Llombart B, Cruz J, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma may mimic a cutaneous peripheral nerve sheath tumor: report of 3 challenging cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;4:632-638.

- Yeh I, McCalmont, TH. Distinguishing neurofibroma from desmoplastic melanoma: the value of the CD34 fingerprint. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:625-630.

- Jou A, Miranda FV, Oliveira MG, et al. Oral desmoplastic melanoma mimicking inflammatory hyperplasia. Gerodontology. 2012;29:E1163-E1167.

- Ishikura H, Kojo T, Ichimura H, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: a rare primary malignancy in the uterus mimicking a sarcoma. Histopathology. 1998;33:93-94.

- Barnett SL, Wells MJ, Mickey B, et al. Perineural extension of cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma mimicking an intracranial malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. case report. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:273-277.

- Jain S, Allen PW. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma and its variants. a study of 45 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:358-373.

- Skelton HG, Maceira J, Smith KJ, et al. HMB45 negative spindle cell malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:580-584.

- George E, McClain SE, Slingluff CL, et al. Subclassification of desmoplastic melanoma: pure and mixed variants have significantly different capacities for lymph node metastasis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:425-432.

- Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanoma. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:321-330.

Desmoplastic melanoma (DMM) is a rare variant of melanoma that presents major challenges to both clinicians and pathologists.1 Clinically, the lesions may appear as subtle bland papules, nodules, or plaques. They can be easily mistaken for benign growths, leading to a delayed diagnosis. Consequently, most DMMs at the time of diagnosis tend to be thick, with a mean Breslow depth ranging from 2.0 to 6.5 mm.2 Histopathologic evaluation has its difficulties. At scanning magnification, these tumors may show low cellularity, mimicking a benign proliferation. It is well recognized that S-100 and other tumor markers lack specificity for DMM, which can be positive in a range of neural tumors and other cell types.2 In some amelanotic tumors, DMM becomes virtually indistinguishable from benign peripheral sheath tumors such as neurofribroma.3

Desmoplastic melanoma is exceedingly uncommon in the United States, with an estimated annual incidence rate of 2.0 cases per million.2 Typical locations of presentation include sun-exposed skin, with the head and neck regions representing more than half of reported cases.2 Desmoplastic melanoma largely is a disease of fair-skinned patients, with 95.5% of cases in the United States occurring in white non-Hispanic individuals. Advancing age, male gender, and head and neck location are associated with an increased risk for DMM-specific death.2 It is important that new or changing lesions in the correct cohort and location are biopsied promptly. We present this case to highlight the ongoing challenges of diagnosing DMM both clinically and histologically and to review the salient features of this often benign-appearing tumor.

Case Report

A 51-year-old White man with a history of prostate cancer, a personal and family history of melanoma, and benign neurofibromas presented with a 6-mm, pink, well-demarcated, soft papule on the left lateral neck (Figure 1). The lesion had been stable for many years but began growing more rapidly 1 to 2 years prior to presentation. The lesion was asymptomatic, and he denied changes in color or texture. There also was no bleeding or ulceration. A review of systems was unremarkable. A shave biopsy of the lesion revealed a nodular spindle cell tumor in the dermis resembling a neurofibroma on low power (Figure 2). However, overlying the tumor was a confluent proliferation positive for MART-1 and S-100, which was consistent with a diagnosis of melanoma in situ (Figure 3). Higher-power evaluation of the dermal proliferation showed both bland and hyperchromatic spindled and epithelioid cells (Figure 4), with rare mitotic figures highlighted by PHH3, an uncommon finding in neurofibromas (Figure 5). The dermal spindle cells were positive for S-100 and p75 and negative for Melan-A. Epithelial membrane antigen highlighted a faint sheath surrounding the dermal component. Ki-67 revealed a mildly increased proliferative index in the dermal component. The diagnosis of DMM was made after outside dermatopathology consultation was in agreement. However, the possibility of a melanoma in situ growing in association with an underlying neurofibroma remained a diagnostic consideration histologically. The lesion was widely excised.

Comment

Differential for DMM

Early DMMs may not show sufficient cytologic atypia to permit obvious distinction from neurofibromas, which becomes problematic when encountering a spindle cell proliferation within severely sun-damaged skin, or even more so when an intraepidermal population of melanocytes is situated above a dermal population of slender, spindled, S-100–positive cells, as seen in our patient.4 For these challenging scenarios, Yeh and McCalmont4 have proposed evaluating for a CD34 “fingerprint” pattern. This pattern typically is widespread in neurofibroma but absent or limited in DMM, and it is a useful adjunct in the differential diagnosis when conventional immunohistochemistry has little contribution.

There are several case reports in the literature of DMM mimicking other benign or malignant proliferations. In 2012, Jou et al5 described a case of a 62-year-old White man who presented with an oral nodule consistent with fibrous inflammatory hyperplasia clinically. Incisional biopsy later confirmed the diagnosis of amelanotic DMM.5 Similar case reports have been described in which the diagnosis of DMM was later found to resemble a sarcoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.6,7

Diagnosis of DMM

The prototypical DMM is an asymmetrical and deeply infiltrative spindle cell lesion in severely sun-damaged skin. By definition, the individual melanocytes are separated by connective tissue components, giving the tumor a paucicellular appearance.1 Although the low cellularity can give a deceptively bland scanning aspect, on high-power examination there usually are identifiable atypical spindled cells with enlarged, elongated, and hyperchromatic nuclei. S-100 typically is diffusely positive in DMM, though occasional cases show more limited staining.8 Other commonly used and more specific markers of melanocytic differentiation, including HMB45 and Melan-A, typically are negative in the paucicellular spindle cell components.9 Desmoplastic melanoma can be further categorized by the degree of fibrosis within a particular tumor. If fibrosis is prominent throughout the entire tumor, it is named pure DMM. On the other hand, fibrosis may only represent a portion of an otherwise nondesmoplastic melanoma, which is known as combined DMM.10

Conclusion

We present this case to highlight the ongoing challenges of diagnosing DMM both clinically and histologically. Although a bland-appearing lesion, key clinical features prompting a biopsy in our patient included recent growth of the lesion, a personal history of melanoma, the patient’s fair skin type, a history of heavy sun exposure, and the location of the lesion. According to Busam,11 an associated melanoma in situ component is identified in 80% to 85% of DMM cases. Detection of a melanoma in situ component associated with a malignant spindle cell tumor can help establish the diagnosis of DMM. In the absence of melanoma in situ, a strong diffuse immunoreactivity for S-100 and lack of epithelial markers support the diagnosis.11 After review of the literature, our case likely represents DMM as opposed to a melanoma in situ developing within a neurofibroma.

Desmoplastic melanoma (DMM) is a rare variant of melanoma that presents major challenges to both clinicians and pathologists.1 Clinically, the lesions may appear as subtle bland papules, nodules, or plaques. They can be easily mistaken for benign growths, leading to a delayed diagnosis. Consequently, most DMMs at the time of diagnosis tend to be thick, with a mean Breslow depth ranging from 2.0 to 6.5 mm.2 Histopathologic evaluation has its difficulties. At scanning magnification, these tumors may show low cellularity, mimicking a benign proliferation. It is well recognized that S-100 and other tumor markers lack specificity for DMM, which can be positive in a range of neural tumors and other cell types.2 In some amelanotic tumors, DMM becomes virtually indistinguishable from benign peripheral sheath tumors such as neurofribroma.3

Desmoplastic melanoma is exceedingly uncommon in the United States, with an estimated annual incidence rate of 2.0 cases per million.2 Typical locations of presentation include sun-exposed skin, with the head and neck regions representing more than half of reported cases.2 Desmoplastic melanoma largely is a disease of fair-skinned patients, with 95.5% of cases in the United States occurring in white non-Hispanic individuals. Advancing age, male gender, and head and neck location are associated with an increased risk for DMM-specific death.2 It is important that new or changing lesions in the correct cohort and location are biopsied promptly. We present this case to highlight the ongoing challenges of diagnosing DMM both clinically and histologically and to review the salient features of this often benign-appearing tumor.

Case Report

A 51-year-old White man with a history of prostate cancer, a personal and family history of melanoma, and benign neurofibromas presented with a 6-mm, pink, well-demarcated, soft papule on the left lateral neck (Figure 1). The lesion had been stable for many years but began growing more rapidly 1 to 2 years prior to presentation. The lesion was asymptomatic, and he denied changes in color or texture. There also was no bleeding or ulceration. A review of systems was unremarkable. A shave biopsy of the lesion revealed a nodular spindle cell tumor in the dermis resembling a neurofibroma on low power (Figure 2). However, overlying the tumor was a confluent proliferation positive for MART-1 and S-100, which was consistent with a diagnosis of melanoma in situ (Figure 3). Higher-power evaluation of the dermal proliferation showed both bland and hyperchromatic spindled and epithelioid cells (Figure 4), with rare mitotic figures highlighted by PHH3, an uncommon finding in neurofibromas (Figure 5). The dermal spindle cells were positive for S-100 and p75 and negative for Melan-A. Epithelial membrane antigen highlighted a faint sheath surrounding the dermal component. Ki-67 revealed a mildly increased proliferative index in the dermal component. The diagnosis of DMM was made after outside dermatopathology consultation was in agreement. However, the possibility of a melanoma in situ growing in association with an underlying neurofibroma remained a diagnostic consideration histologically. The lesion was widely excised.

Comment

Differential for DMM

Early DMMs may not show sufficient cytologic atypia to permit obvious distinction from neurofibromas, which becomes problematic when encountering a spindle cell proliferation within severely sun-damaged skin, or even more so when an intraepidermal population of melanocytes is situated above a dermal population of slender, spindled, S-100–positive cells, as seen in our patient.4 For these challenging scenarios, Yeh and McCalmont4 have proposed evaluating for a CD34 “fingerprint” pattern. This pattern typically is widespread in neurofibroma but absent or limited in DMM, and it is a useful adjunct in the differential diagnosis when conventional immunohistochemistry has little contribution.

There are several case reports in the literature of DMM mimicking other benign or malignant proliferations. In 2012, Jou et al5 described a case of a 62-year-old White man who presented with an oral nodule consistent with fibrous inflammatory hyperplasia clinically. Incisional biopsy later confirmed the diagnosis of amelanotic DMM.5 Similar case reports have been described in which the diagnosis of DMM was later found to resemble a sarcoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.6,7

Diagnosis of DMM

The prototypical DMM is an asymmetrical and deeply infiltrative spindle cell lesion in severely sun-damaged skin. By definition, the individual melanocytes are separated by connective tissue components, giving the tumor a paucicellular appearance.1 Although the low cellularity can give a deceptively bland scanning aspect, on high-power examination there usually are identifiable atypical spindled cells with enlarged, elongated, and hyperchromatic nuclei. S-100 typically is diffusely positive in DMM, though occasional cases show more limited staining.8 Other commonly used and more specific markers of melanocytic differentiation, including HMB45 and Melan-A, typically are negative in the paucicellular spindle cell components.9 Desmoplastic melanoma can be further categorized by the degree of fibrosis within a particular tumor. If fibrosis is prominent throughout the entire tumor, it is named pure DMM. On the other hand, fibrosis may only represent a portion of an otherwise nondesmoplastic melanoma, which is known as combined DMM.10

Conclusion

We present this case to highlight the ongoing challenges of diagnosing DMM both clinically and histologically. Although a bland-appearing lesion, key clinical features prompting a biopsy in our patient included recent growth of the lesion, a personal history of melanoma, the patient’s fair skin type, a history of heavy sun exposure, and the location of the lesion. According to Busam,11 an associated melanoma in situ component is identified in 80% to 85% of DMM cases. Detection of a melanoma in situ component associated with a malignant spindle cell tumor can help establish the diagnosis of DMM. In the absence of melanoma in situ, a strong diffuse immunoreactivity for S-100 and lack of epithelial markers support the diagnosis.11 After review of the literature, our case likely represents DMM as opposed to a melanoma in situ developing within a neurofibroma.

- Wood BA. Desmoplastic melanoma: recent advances and persisting challenges. Pathology. 2013;45:453-463.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- Machado I, Llombart B, Cruz J, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma may mimic a cutaneous peripheral nerve sheath tumor: report of 3 challenging cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;4:632-638.

- Yeh I, McCalmont, TH. Distinguishing neurofibroma from desmoplastic melanoma: the value of the CD34 fingerprint. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:625-630.

- Jou A, Miranda FV, Oliveira MG, et al. Oral desmoplastic melanoma mimicking inflammatory hyperplasia. Gerodontology. 2012;29:E1163-E1167.

- Ishikura H, Kojo T, Ichimura H, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: a rare primary malignancy in the uterus mimicking a sarcoma. Histopathology. 1998;33:93-94.

- Barnett SL, Wells MJ, Mickey B, et al. Perineural extension of cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma mimicking an intracranial malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. case report. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:273-277.

- Jain S, Allen PW. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma and its variants. a study of 45 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:358-373.

- Skelton HG, Maceira J, Smith KJ, et al. HMB45 negative spindle cell malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:580-584.

- George E, McClain SE, Slingluff CL, et al. Subclassification of desmoplastic melanoma: pure and mixed variants have significantly different capacities for lymph node metastasis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:425-432.

- Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanoma. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:321-330.

- Wood BA. Desmoplastic melanoma: recent advances and persisting challenges. Pathology. 2013;45:453-463.

- Chen LL, Jaimes N, Barker CA, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:825-833.

- Machado I, Llombart B, Cruz J, et al. Desmoplastic melanoma may mimic a cutaneous peripheral nerve sheath tumor: report of 3 challenging cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;4:632-638.

- Yeh I, McCalmont, TH. Distinguishing neurofibroma from desmoplastic melanoma: the value of the CD34 fingerprint. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:625-630.

- Jou A, Miranda FV, Oliveira MG, et al. Oral desmoplastic melanoma mimicking inflammatory hyperplasia. Gerodontology. 2012;29:E1163-E1167.

- Ishikura H, Kojo T, Ichimura H, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma of the uterine cervix: a rare primary malignancy in the uterus mimicking a sarcoma. Histopathology. 1998;33:93-94.

- Barnett SL, Wells MJ, Mickey B, et al. Perineural extension of cutaneous desmoplastic melanoma mimicking an intracranial malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. case report. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:273-277.

- Jain S, Allen PW. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma and its variants. a study of 45 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:358-373.

- Skelton HG, Maceira J, Smith KJ, et al. HMB45 negative spindle cell malignant melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:580-584.

- George E, McClain SE, Slingluff CL, et al. Subclassification of desmoplastic melanoma: pure and mixed variants have significantly different capacities for lymph node metastasis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:425-432.

- Busam KJ. Desmoplastic melanoma. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:321-330.

Practice Points

- Desmoplastic melanoma remains a diagnostic challenge both clinically and histologically.

- New or changing lesions on sun-exposed sites of elderly patients with fair skin types should have a low threshold for biopsy.

- Consensus between more than one dermatopathologist is sometimes required to make the diagnosis histologically.

Cutaneous Insulin-Derived Amyloidosis Presenting as Hyperkeratotic Nodules

Amyloidosis consists of approximately 30 protein-folding disorders sharing the common feature of abnormal extracellular amyloid deposition. In each condition, a specific soluble precursor protein aggregates to form the insoluble fibrils of amyloid, characterized by the beta-pleated sheet structure.1 Amyloidosis occurs as either a systemic or localized process. Insulin-derived (AIns) amyloidosis, a localized process occurring at insulin injection sites, was first reported in 1983.2 There were fewer than 20 reported cases until 2014, when 57 additional cases were reported by just 2 institutions,3,4 indicating that AIns amyloidosis may be more common than previously thought.3,5

Despite the increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus and insulin use, there is a paucity of published cases of AIns amyloidosis. The lack of awareness of this condition among both dermatologists and general practitioners may be in part due to its variable clinical manifestations. We describe 2 patients with unique presentations of localized amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 39-year-old man with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus presented with 4 asymptomatic nodules on the lateral thighs in areas of previous insulin injection. He first noticed the lesions 9 months prior to presentation and subsequently switched the injection site to the abdomen without development of new nodules. Despite being compliant with his insulin regimen, he had a long history of irregular glucose control, including frequent hypoglycemic episodes. The patient was using regular and neutral protamine hagedorn insulin.

On physical examination, 2 soft, nontender, exophytic nodules were noted on each upper thigh with surrounding hyperpigmented and hyperkeratotic collarettes (Figure 1). The nodules ranged in size from 2 to 3.5 cm in diameter.

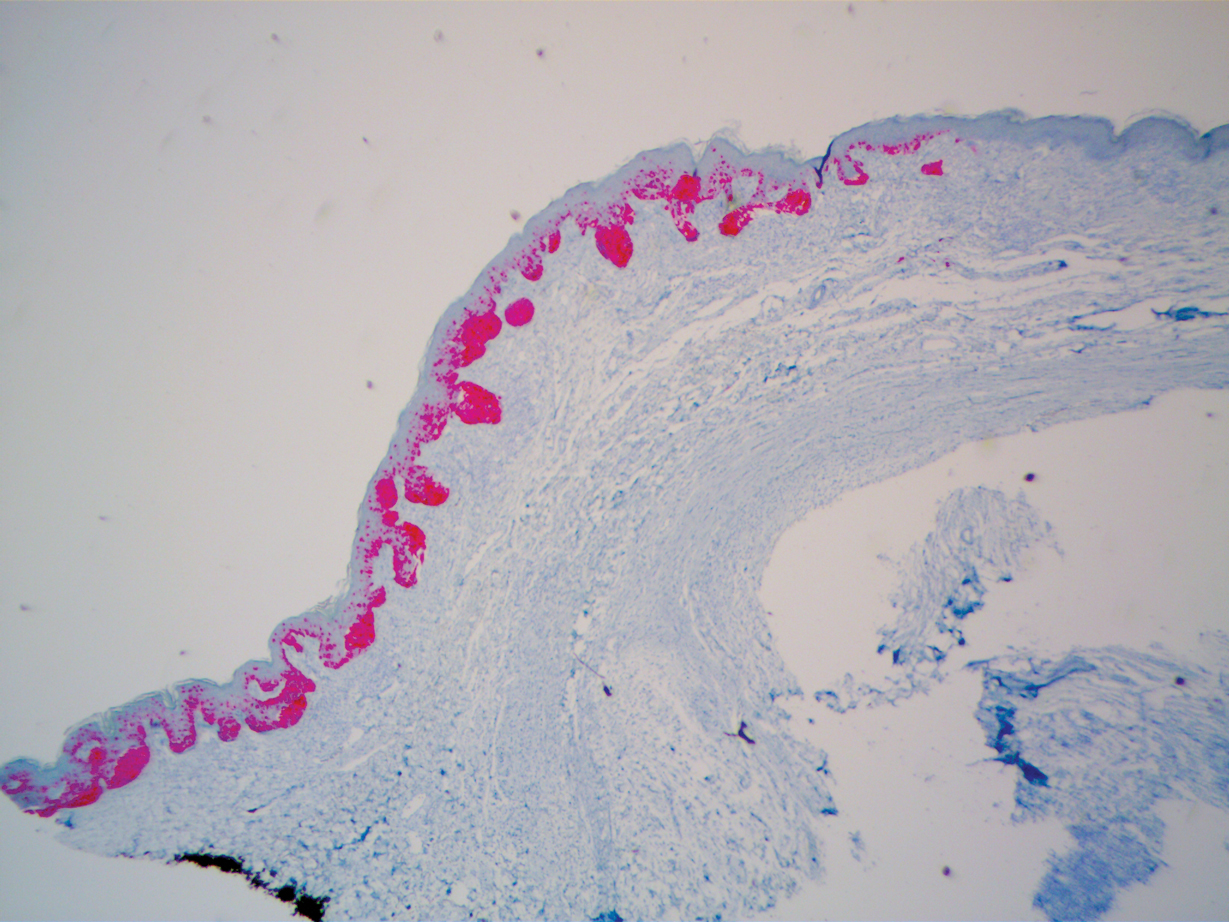

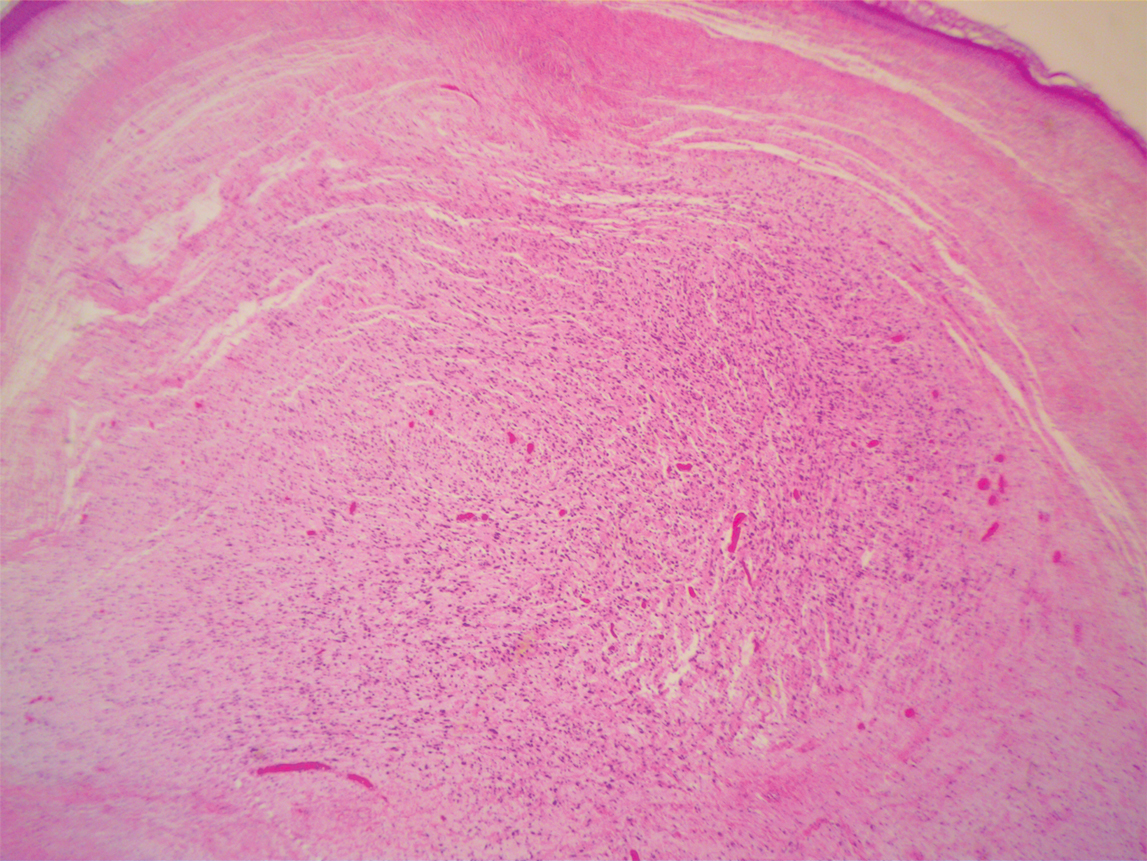

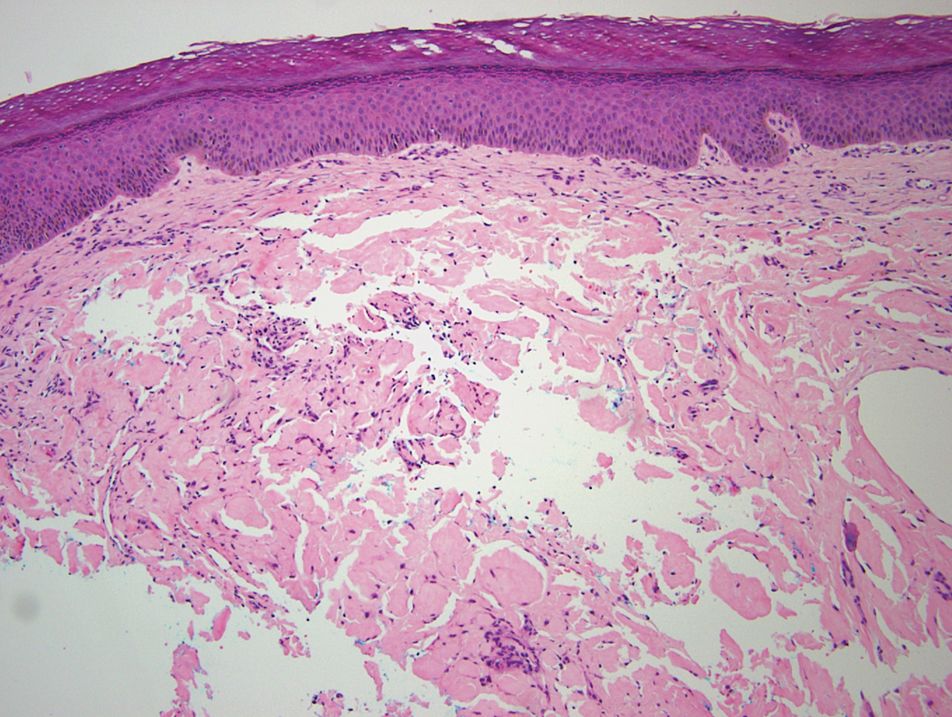

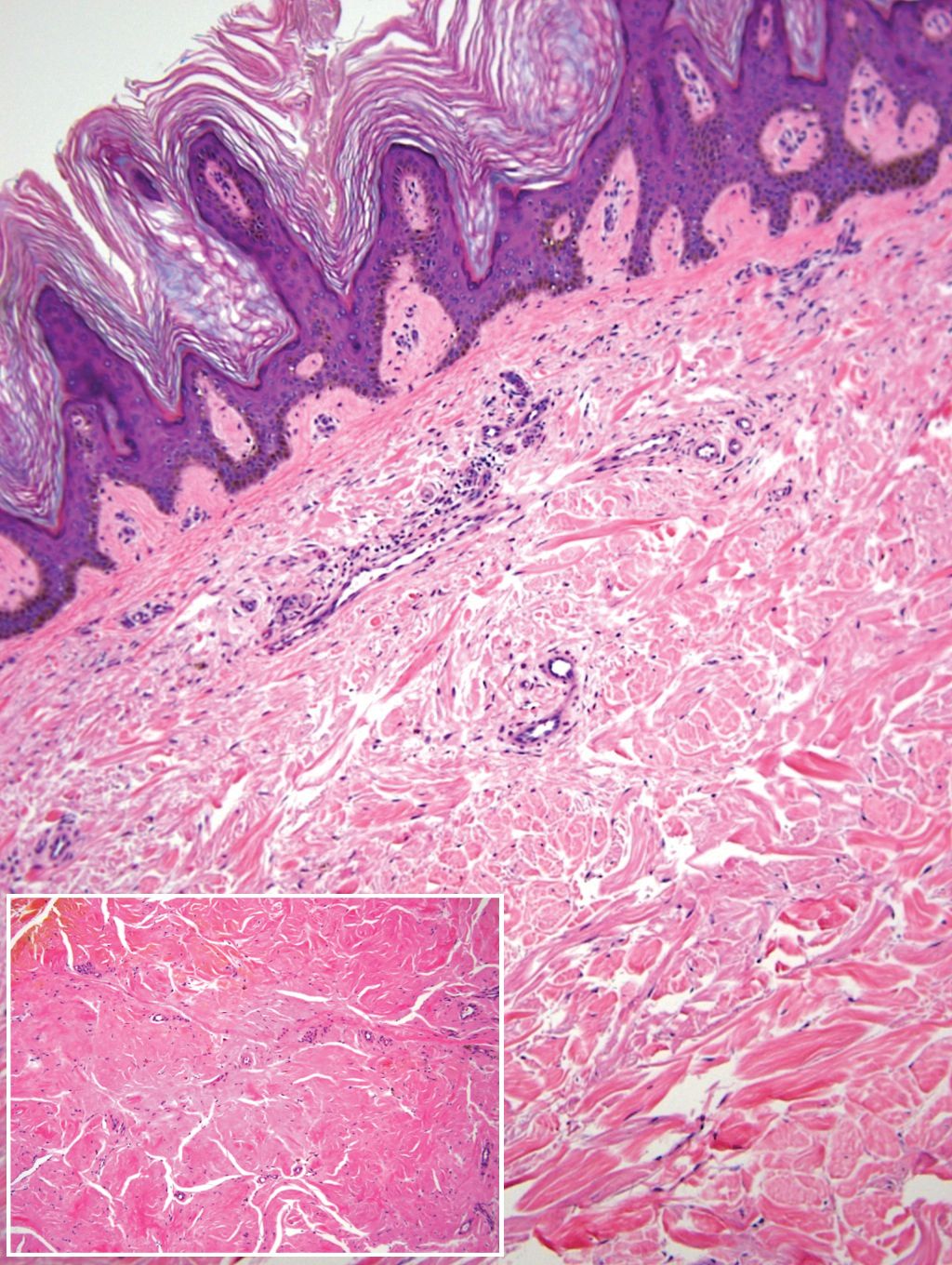

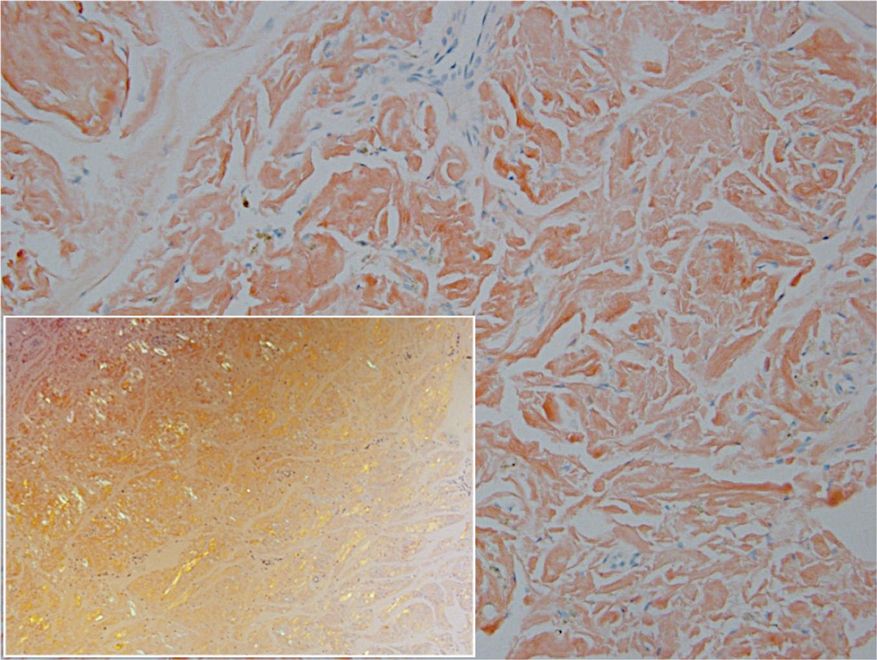

Remarkable laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 207 mg/dL (reference range, 70–110 mg/dL) and a glycohemoglobin of 8.8% (reference range, <5.7%). Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation were normal. Histopathology of the lesions demonstrated diffuse deposition of pink amorphous material associated with prominent papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Congo red staining was positive with green birefringence under polarized light, indicative of amyloid deposits (Figure 3). Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimens was consistent with deposition of AIns amyloidosis.

Due to the size and persistent nature of the lesions, the nodules were removed by tangential excision. In addition, the patient was advised to continue rotating injection sites frequently. His blood glucose levels are now well controlled, and he has not developed any new nodules.

Patient 2

A 53-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with painful subcutaneous nodules on the lower abdomen at sites of previous insulin injections. The nodules developed approximately 1 month after she started treatment with neutral protamine hagedorn insulin and had been slowly enlarging over the past year. She tried switching injection sites after noticing the lesions, but the nodules persisted. The patient had a long history of poor glucose control with chronically elevated glycohemoglobin and blood glucose levels.

On physical examination, 2 hyperpigmented, exophytic, smooth nodules were noted on the right and left lower abdomen, ranging in size from 2.5 to 5.5 cm in diameter (Figure 4).

Relevant laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 197 mg/dL and a glycohemoglobin of 9.3%. A biopsy of the lesion on the left lower abdomen revealed eosinophilic amorphous deposits with fissuring in the dermis (Figure 5). Congo red stain was positive with green birefringence under polarized light. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimen showed deposition of AIns amyloid. The patient began injecting away from the amyloid nodules without development of any new lesions. The original nodules have persisted, and surgical excision is planned.

Comment

Insulin is the suspected precursor protein in AIns amyloidosis, but the exact pathogenesis is unknown. The protein that is derived from insulin in these tumors is now identified as AIns amyloidosis.5,6 It is hypothesized that insulin accumulates locally and is converted to amyloid by an unknown mechanism.7 Other potential contributory factors include chronic inflammation and foreign body reactions developing around amyloid deposits, as well as repeated trauma from injections into a single site.4,5 It appears that lesions may derive from a wide range of insulin types and occur after variable time periods.

A majority of cases of iatrogenic amyloid have been described as single, firm, subcutaneous masses at an injection site that commonly are misdiagnosed as lipomas or lipohypertrophy.7-11 To our knowledge, none of the reported cases resembled the multiple, discrete, exophytic nodules seen in our patients.3,4 The surrounding hyperkeratosis noted in patient 1 is another uncommon feature of AIns amyloidosis (Figures 1 and 2). Only 3 AIns amyloidosis cases described lesions with acanthosis nigricans–like changes, only 1 of which provided a clinical image.6,7,12The mechanism for the acanthosis nigricans–like changes may have been due to the high levels of insulin at the injection site. It has been suggested that the activation of insulinlike growth factor receptor by insulin leads to the proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts.6 Histologic examination of AIns amyloidosis lesions generally demonstrates deposition of homogenous eosinophilic material consistent with amyloid, as well as positive Congo red staining with green birefringence by polarization. Immunohistologic staining with insulin antibody with or without proteomic analysis of the amyloid deposits can confirm the diagnosis. In both of our patients’ specimens, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry was performed for proteomic analysis, and results were consistent with AIns amyloidosis.

Reports in the literature have suggested that the deposition of amyloid at insulin injection sites has the potential to interfere with insulin absorption, leading to poor glucose control.4,11,13 Hence, injection site rotation is a crucial aspect of treatment and prevention of AIns amyloidosis. In their study of 4 patients, Nagase et al4 compared serum insulin levels after insulin injection into amyloid nodules vs insulin levels after injection into normal skin. Insulin absorption at the amyloid sites was 34% of that at normal sites. Given these results, patients should be instructed to inject away from the amyloid deposit once it is identified.6 Glucose levels should be monitored closely when patients first inject away from the amyloid mass, as injection of the same dosage to an area of normal skin can lead to increased insulin absorption and hypoglycemia.4,6 It is possible that the frequent hypoglycemic episodes noted in patient 1 were due to increased insulin sensitivity after switching to injection sites away from amyloid lesions.

Conclusion

Our patients demonstrate unique presentations of localized cutaneous amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites. We report these cases to complement the current data of iatrogenic amyloidosis and provide insight into this likely underreported phenomenon.

- Hazenberg BPC. Amyloidosis: a clinical overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:323-345.

- Storkel S, Schneider HM, Muntefering H, et al. Iatrogenic, insulin-dependent, local amyloidosis. Lab Invest. 1983;48:108-111.

- D’souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration. Amyloid. 2014;21:71-75.

- Nagase T, Iwaya K, Iwaki Y, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis and poor glycemic control: a case series. Am J Med. 2014;127:450-454.

- Gupta Y, Singla G, Singla R. Insulin-derived amyloidosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:174-177.

- Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, et al. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:25-29.

- Yumlu S, Barany R, Eriksson M, et al. Localized insulin-derived amyloidosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: a case report. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1655-1660.

- Okamura S, Hayashino Y, Kore-Eda S, et al. Localized amyloidosis at the site of repeated insulin injection in a patient with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:E200.

- Dische FE, Wernstedt C, Westermark GT, et al. Insulin as an amyloid-fibril protein at sites of repeated insulin injections in a diabetic patient. Diabetologia. 1988;31:158-161.

- Swift B, Hawkins PN, Richards C, et al. Examination of insulin injection sites: an unexpected finding of localized amyloidosis. Diabetic Med. 2002;19:881-882.

- Albert SG, Obadiah J, Parseghian SA, et al. Severe insulin resistance associated with subcutaneous amyloid deposition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:374-376.

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:127-129.

- Endo JO, Rocken C, Lamb S, et al. Nodular amyloidosis in a diabetic patient with frequent hypoglycemia: sequelae of repeatedly injecting insulin without site rotation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:E113-E114.

Amyloidosis consists of approximately 30 protein-folding disorders sharing the common feature of abnormal extracellular amyloid deposition. In each condition, a specific soluble precursor protein aggregates to form the insoluble fibrils of amyloid, characterized by the beta-pleated sheet structure.1 Amyloidosis occurs as either a systemic or localized process. Insulin-derived (AIns) amyloidosis, a localized process occurring at insulin injection sites, was first reported in 1983.2 There were fewer than 20 reported cases until 2014, when 57 additional cases were reported by just 2 institutions,3,4 indicating that AIns amyloidosis may be more common than previously thought.3,5

Despite the increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus and insulin use, there is a paucity of published cases of AIns amyloidosis. The lack of awareness of this condition among both dermatologists and general practitioners may be in part due to its variable clinical manifestations. We describe 2 patients with unique presentations of localized amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 39-year-old man with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus presented with 4 asymptomatic nodules on the lateral thighs in areas of previous insulin injection. He first noticed the lesions 9 months prior to presentation and subsequently switched the injection site to the abdomen without development of new nodules. Despite being compliant with his insulin regimen, he had a long history of irregular glucose control, including frequent hypoglycemic episodes. The patient was using regular and neutral protamine hagedorn insulin.

On physical examination, 2 soft, nontender, exophytic nodules were noted on each upper thigh with surrounding hyperpigmented and hyperkeratotic collarettes (Figure 1). The nodules ranged in size from 2 to 3.5 cm in diameter.

Remarkable laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 207 mg/dL (reference range, 70–110 mg/dL) and a glycohemoglobin of 8.8% (reference range, <5.7%). Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation were normal. Histopathology of the lesions demonstrated diffuse deposition of pink amorphous material associated with prominent papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Congo red staining was positive with green birefringence under polarized light, indicative of amyloid deposits (Figure 3). Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimens was consistent with deposition of AIns amyloidosis.

Due to the size and persistent nature of the lesions, the nodules were removed by tangential excision. In addition, the patient was advised to continue rotating injection sites frequently. His blood glucose levels are now well controlled, and he has not developed any new nodules.

Patient 2

A 53-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with painful subcutaneous nodules on the lower abdomen at sites of previous insulin injections. The nodules developed approximately 1 month after she started treatment with neutral protamine hagedorn insulin and had been slowly enlarging over the past year. She tried switching injection sites after noticing the lesions, but the nodules persisted. The patient had a long history of poor glucose control with chronically elevated glycohemoglobin and blood glucose levels.

On physical examination, 2 hyperpigmented, exophytic, smooth nodules were noted on the right and left lower abdomen, ranging in size from 2.5 to 5.5 cm in diameter (Figure 4).

Relevant laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 197 mg/dL and a glycohemoglobin of 9.3%. A biopsy of the lesion on the left lower abdomen revealed eosinophilic amorphous deposits with fissuring in the dermis (Figure 5). Congo red stain was positive with green birefringence under polarized light. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimen showed deposition of AIns amyloid. The patient began injecting away from the amyloid nodules without development of any new lesions. The original nodules have persisted, and surgical excision is planned.

Comment

Insulin is the suspected precursor protein in AIns amyloidosis, but the exact pathogenesis is unknown. The protein that is derived from insulin in these tumors is now identified as AIns amyloidosis.5,6 It is hypothesized that insulin accumulates locally and is converted to amyloid by an unknown mechanism.7 Other potential contributory factors include chronic inflammation and foreign body reactions developing around amyloid deposits, as well as repeated trauma from injections into a single site.4,5 It appears that lesions may derive from a wide range of insulin types and occur after variable time periods.

A majority of cases of iatrogenic amyloid have been described as single, firm, subcutaneous masses at an injection site that commonly are misdiagnosed as lipomas or lipohypertrophy.7-11 To our knowledge, none of the reported cases resembled the multiple, discrete, exophytic nodules seen in our patients.3,4 The surrounding hyperkeratosis noted in patient 1 is another uncommon feature of AIns amyloidosis (Figures 1 and 2). Only 3 AIns amyloidosis cases described lesions with acanthosis nigricans–like changes, only 1 of which provided a clinical image.6,7,12The mechanism for the acanthosis nigricans–like changes may have been due to the high levels of insulin at the injection site. It has been suggested that the activation of insulinlike growth factor receptor by insulin leads to the proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts.6 Histologic examination of AIns amyloidosis lesions generally demonstrates deposition of homogenous eosinophilic material consistent with amyloid, as well as positive Congo red staining with green birefringence by polarization. Immunohistologic staining with insulin antibody with or without proteomic analysis of the amyloid deposits can confirm the diagnosis. In both of our patients’ specimens, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry was performed for proteomic analysis, and results were consistent with AIns amyloidosis.

Reports in the literature have suggested that the deposition of amyloid at insulin injection sites has the potential to interfere with insulin absorption, leading to poor glucose control.4,11,13 Hence, injection site rotation is a crucial aspect of treatment and prevention of AIns amyloidosis. In their study of 4 patients, Nagase et al4 compared serum insulin levels after insulin injection into amyloid nodules vs insulin levels after injection into normal skin. Insulin absorption at the amyloid sites was 34% of that at normal sites. Given these results, patients should be instructed to inject away from the amyloid deposit once it is identified.6 Glucose levels should be monitored closely when patients first inject away from the amyloid mass, as injection of the same dosage to an area of normal skin can lead to increased insulin absorption and hypoglycemia.4,6 It is possible that the frequent hypoglycemic episodes noted in patient 1 were due to increased insulin sensitivity after switching to injection sites away from amyloid lesions.

Conclusion

Our patients demonstrate unique presentations of localized cutaneous amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites. We report these cases to complement the current data of iatrogenic amyloidosis and provide insight into this likely underreported phenomenon.

Amyloidosis consists of approximately 30 protein-folding disorders sharing the common feature of abnormal extracellular amyloid deposition. In each condition, a specific soluble precursor protein aggregates to form the insoluble fibrils of amyloid, characterized by the beta-pleated sheet structure.1 Amyloidosis occurs as either a systemic or localized process. Insulin-derived (AIns) amyloidosis, a localized process occurring at insulin injection sites, was first reported in 1983.2 There were fewer than 20 reported cases until 2014, when 57 additional cases were reported by just 2 institutions,3,4 indicating that AIns amyloidosis may be more common than previously thought.3,5

Despite the increasing prevalence of diabetes mellitus and insulin use, there is a paucity of published cases of AIns amyloidosis. The lack of awareness of this condition among both dermatologists and general practitioners may be in part due to its variable clinical manifestations. We describe 2 patients with unique presentations of localized amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 39-year-old man with a history of type 1 diabetes mellitus presented with 4 asymptomatic nodules on the lateral thighs in areas of previous insulin injection. He first noticed the lesions 9 months prior to presentation and subsequently switched the injection site to the abdomen without development of new nodules. Despite being compliant with his insulin regimen, he had a long history of irregular glucose control, including frequent hypoglycemic episodes. The patient was using regular and neutral protamine hagedorn insulin.

On physical examination, 2 soft, nontender, exophytic nodules were noted on each upper thigh with surrounding hyperpigmented and hyperkeratotic collarettes (Figure 1). The nodules ranged in size from 2 to 3.5 cm in diameter.

Remarkable laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 207 mg/dL (reference range, 70–110 mg/dL) and a glycohemoglobin of 8.8% (reference range, <5.7%). Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation were normal. Histopathology of the lesions demonstrated diffuse deposition of pink amorphous material associated with prominent papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, and acanthosis (Figure 2). Congo red staining was positive with green birefringence under polarized light, indicative of amyloid deposits (Figure 3). Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimens was consistent with deposition of AIns amyloidosis.

Due to the size and persistent nature of the lesions, the nodules were removed by tangential excision. In addition, the patient was advised to continue rotating injection sites frequently. His blood glucose levels are now well controlled, and he has not developed any new nodules.

Patient 2

A 53-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with painful subcutaneous nodules on the lower abdomen at sites of previous insulin injections. The nodules developed approximately 1 month after she started treatment with neutral protamine hagedorn insulin and had been slowly enlarging over the past year. She tried switching injection sites after noticing the lesions, but the nodules persisted. The patient had a long history of poor glucose control with chronically elevated glycohemoglobin and blood glucose levels.

On physical examination, 2 hyperpigmented, exophytic, smooth nodules were noted on the right and left lower abdomen, ranging in size from 2.5 to 5.5 cm in diameter (Figure 4).

Relevant laboratory data included a fasting glucose level of 197 mg/dL and a glycohemoglobin of 9.3%. A biopsy of the lesion on the left lower abdomen revealed eosinophilic amorphous deposits with fissuring in the dermis (Figure 5). Congo red stain was positive with green birefringence under polarized light. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry of the specimen showed deposition of AIns amyloid. The patient began injecting away from the amyloid nodules without development of any new lesions. The original nodules have persisted, and surgical excision is planned.

Comment

Insulin is the suspected precursor protein in AIns amyloidosis, but the exact pathogenesis is unknown. The protein that is derived from insulin in these tumors is now identified as AIns amyloidosis.5,6 It is hypothesized that insulin accumulates locally and is converted to amyloid by an unknown mechanism.7 Other potential contributory factors include chronic inflammation and foreign body reactions developing around amyloid deposits, as well as repeated trauma from injections into a single site.4,5 It appears that lesions may derive from a wide range of insulin types and occur after variable time periods.

A majority of cases of iatrogenic amyloid have been described as single, firm, subcutaneous masses at an injection site that commonly are misdiagnosed as lipomas or lipohypertrophy.7-11 To our knowledge, none of the reported cases resembled the multiple, discrete, exophytic nodules seen in our patients.3,4 The surrounding hyperkeratosis noted in patient 1 is another uncommon feature of AIns amyloidosis (Figures 1 and 2). Only 3 AIns amyloidosis cases described lesions with acanthosis nigricans–like changes, only 1 of which provided a clinical image.6,7,12The mechanism for the acanthosis nigricans–like changes may have been due to the high levels of insulin at the injection site. It has been suggested that the activation of insulinlike growth factor receptor by insulin leads to the proliferation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts.6 Histologic examination of AIns amyloidosis lesions generally demonstrates deposition of homogenous eosinophilic material consistent with amyloid, as well as positive Congo red staining with green birefringence by polarization. Immunohistologic staining with insulin antibody with or without proteomic analysis of the amyloid deposits can confirm the diagnosis. In both of our patients’ specimens, liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry was performed for proteomic analysis, and results were consistent with AIns amyloidosis.

Reports in the literature have suggested that the deposition of amyloid at insulin injection sites has the potential to interfere with insulin absorption, leading to poor glucose control.4,11,13 Hence, injection site rotation is a crucial aspect of treatment and prevention of AIns amyloidosis. In their study of 4 patients, Nagase et al4 compared serum insulin levels after insulin injection into amyloid nodules vs insulin levels after injection into normal skin. Insulin absorption at the amyloid sites was 34% of that at normal sites. Given these results, patients should be instructed to inject away from the amyloid deposit once it is identified.6 Glucose levels should be monitored closely when patients first inject away from the amyloid mass, as injection of the same dosage to an area of normal skin can lead to increased insulin absorption and hypoglycemia.4,6 It is possible that the frequent hypoglycemic episodes noted in patient 1 were due to increased insulin sensitivity after switching to injection sites away from amyloid lesions.

Conclusion

Our patients demonstrate unique presentations of localized cutaneous amyloidosis at repeated insulin injection sites. We report these cases to complement the current data of iatrogenic amyloidosis and provide insight into this likely underreported phenomenon.

- Hazenberg BPC. Amyloidosis: a clinical overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:323-345.

- Storkel S, Schneider HM, Muntefering H, et al. Iatrogenic, insulin-dependent, local amyloidosis. Lab Invest. 1983;48:108-111.

- D’souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration. Amyloid. 2014;21:71-75.

- Nagase T, Iwaya K, Iwaki Y, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis and poor glycemic control: a case series. Am J Med. 2014;127:450-454.

- Gupta Y, Singla G, Singla R. Insulin-derived amyloidosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:174-177.

- Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, et al. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:25-29.

- Yumlu S, Barany R, Eriksson M, et al. Localized insulin-derived amyloidosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: a case report. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1655-1660.

- Okamura S, Hayashino Y, Kore-Eda S, et al. Localized amyloidosis at the site of repeated insulin injection in a patient with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:E200.

- Dische FE, Wernstedt C, Westermark GT, et al. Insulin as an amyloid-fibril protein at sites of repeated insulin injections in a diabetic patient. Diabetologia. 1988;31:158-161.

- Swift B, Hawkins PN, Richards C, et al. Examination of insulin injection sites: an unexpected finding of localized amyloidosis. Diabetic Med. 2002;19:881-882.

- Albert SG, Obadiah J, Parseghian SA, et al. Severe insulin resistance associated with subcutaneous amyloid deposition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:374-376.

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:127-129.

- Endo JO, Rocken C, Lamb S, et al. Nodular amyloidosis in a diabetic patient with frequent hypoglycemia: sequelae of repeatedly injecting insulin without site rotation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:E113-E114.

- Hazenberg BPC. Amyloidosis: a clinical overview. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:323-345.

- Storkel S, Schneider HM, Muntefering H, et al. Iatrogenic, insulin-dependent, local amyloidosis. Lab Invest. 1983;48:108-111.

- D’souza A, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Pharmaceutical amyloidosis associated with subcutaneous insulin and enfuvirtide administration. Amyloid. 2014;21:71-75.

- Nagase T, Iwaya K, Iwaki Y, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis and poor glycemic control: a case series. Am J Med. 2014;127:450-454.

- Gupta Y, Singla G, Singla R. Insulin-derived amyloidosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19:174-177.

- Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, et al. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:25-29.

- Yumlu S, Barany R, Eriksson M, et al. Localized insulin-derived amyloidosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: a case report. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1655-1660.

- Okamura S, Hayashino Y, Kore-Eda S, et al. Localized amyloidosis at the site of repeated insulin injection in a patient with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:E200.

- Dische FE, Wernstedt C, Westermark GT, et al. Insulin as an amyloid-fibril protein at sites of repeated insulin injections in a diabetic patient. Diabetologia. 1988;31:158-161.

- Swift B, Hawkins PN, Richards C, et al. Examination of insulin injection sites: an unexpected finding of localized amyloidosis. Diabetic Med. 2002;19:881-882.

- Albert SG, Obadiah J, Parseghian SA, et al. Severe insulin resistance associated with subcutaneous amyloid deposition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;75:374-376.

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:127-129.

- Endo JO, Rocken C, Lamb S, et al. Nodular amyloidosis in a diabetic patient with frequent hypoglycemia: sequelae of repeatedly injecting insulin without site rotation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:E113-E114.

Practice Points

- Deposition of amyloid at insulin injection sites has the potential to interfere with insulin absorption, leading to poor glucose control.

- Patients with insulin-derived (AIns) amyloidosis may initially present after noticing nodular deposits.

- Insulin injection site rotation is a crucial aspect of treatment and prevention of AIns amyloidosis.