User login

Investigating Unstable Thyroid Function

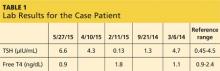

A 43-year-old man presents for his thyroid checkup. He has known hypothyroidism secondary to Hashimoto thyroiditis, also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. He is taking levothyroxine (LT4) 250 μg (two 125-μg tablets once per day). Review of his prior lab results and notes (see Table 1) reveals frequent dose changes (about every three to six months) and a high dosage of LT4, considering his weight (185 lb).

Patients with little or no residual thyroid function require replacement doses of LT4 at approximately 1.6 μg/kg/d, based on lean body weight.1 Since the case patient weighs 84 kg, the expected LT4 dosage would be around 125 to 150 μg/d.

This patient requires a significantly higher dose than expected, and his thyroid levels are fluctuating. These facts should trigger further investigation.

Important historical questions I consider when patients have frequent or significant fluctuations in TSH include

• Are you consistent in taking your medication?

• How do you take your thyroid medication?

• Are you taking any iron supplements, vitamins with iron, or contraceptive pills containing iron?

• Has there been any change in your other medication regimen(s) or medical condition(s)?

• Did you change pharmacies, or did the shape or color of your pill change?

• Have you experienced significant weight changes?

• Do you have any gastrointestinal complaints (nausea/vomiting/diarrhea/bloating)?

MEDICATION ADHERENCE

It is well known but still puzzling to hear that, overall, patients’ medication adherence is merely 50%.2 It is very important that you verify whether your patient is taking his/her medication consistently. Rather than asking “Are you taking your medications?” (to which they are more likely to answer “yes”), I ask “How many pills do you miss in a given week or month?”

For those who have a hard time remembering to take their medication on a regular basis, I recommend setting up a routine: Keep the medication at their bedside and take it first thing upon awakening, or place it beside the toothpaste so they see it every time they brush their teeth in the morning. Another option is of course to set up an alarm as a reminder.

Continue for rules for taking hypothyroid >>

RULES FOR TAKING HYPOTHYROID MEDICATIONS

Thyroid hormone replacement has a narrow therapeutic index, and a subtle change in dosage can significantly alter the therapeutic target. Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the jejunum/ileum, and an acidic pH in the stomach is optimal for thyroid absorption.3 Therefore, taking the medication on an empty stomach (fasting) with a full glass of water and waiting at least one hour before breakfast is recommended, if possible. An alternate option is to take it at bedtime, at least three hours after the last meal. Taking medication along with food, especially high-fiber and soy products, can decrease absorption of thyroid hormone, which may result in an unstable thyroid function test.

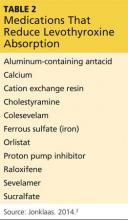

There are supplements and medications that can decrease hypothyroid medication absorption; it is recommended that patients separate these medications by four hours or more in order to minimize this interference. A full list is available in Table 2, but the most commonly encountered are iron supplements, calcium supplements, and proton pump inhibitors.2

In many patients—especially the elderly and those with multiple comorbidities that require polypharmacy—it can be very challenging, if not impossible, to isolate thyroid medication. For these patients, recommend that they be “consistent” with their routine to ensure they achieve a similar absorption rate each time. For example, a patient’s hypothyroid medication absorption might be reduced by 50% by taking it with omeprazole, but as long as the patient consistently takes the medication that way, she can have stable thyroid function.

NEW MEDICATION REGIMEN OR MEDICAL CONDITION

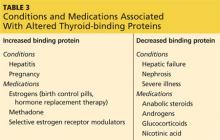

In addition to medications that can interfere with the absorption of thyroid hormone replacement, there are those that affect levels of thyroxine-binding globulin. This affects the bioavailability of thyroid hormones and alters thyroid status.

Thyroid hormones such as thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) are predominantly bound to carrier proteins, and < 1% is unbound (so-called free hormones). Changes in thyroid-binding proteins can alter free hormone levels and thereby change TSH levels. In disease-free euthyroid subjects, the body can compensate by adjusting hormone production for changes in binding proteins to keep the free hormone levels within normal ranges. However, patients who are at or near full replacement doses of hypothyroid medication cannot adjust to the changes.

In patients with hypothyroidism who are taking thyroid hormone replacement, medications or conditions that increase binding proteins will decrease free hormones (by increasing bound hormones) and thereby raise TSH (hypothyroid state). Vice versa, medications and conditions that decrease binding protein will increase free hormones (by decreasing bound hormones) and thereby lower TSH (thyrotoxic state). Table 3 lists commonly encountered medications and conditions associated with altered thyroid-binding proteins.1

It is important to consider pregnancy in women of childbearing age whose TSH has risen for no apparent reason, as their thyroid levels should be maintained in a narrow therapeutic range to prevent fetal complications. Details on thyroid disease during pregnancy can be found in the April 2015 Endocrine Consult, “Managing Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy.”

In women treated for hypothyroidism, starting or discontinuing estrogen-containing medications (birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy) often results in changes in thyroid status. It is a good practice to inform the patient about these changes and to recheck her thyroid labs four to eight weeks after she starts or discontinues estrogen, adjusting the dose if needed.

Continue for changes in manufacturer/brand >>

CHANGES IN MANUFACTURER/BRAND

There are currently multiple brands and generic manufacturers supplying hypothyroid medications and reports that absorption rates and bioavailability vary among them.2 Switching products can result in changes in thyroid status and in TSH levels.

Once a patient has reached euthyroid status, it is imperative to stay on the same dose from the same manufacturer. This may be challenging, as it can be affected by the patient’s insurance carrier, policy changes, or even a change in the pharmacy’s medication supplier. Although patients are supposed to be informed by the pharmacy when the manufacturer is being changed, you may want to educate them to check the shape, color, and dose of their pills and also verify that the manufacturer listed on the bottle is consistent each time they refill their hypothyroid medications. This is especially important for those who require a very narrow TSH target, such as young children, thyroid cancer patients, pregnant women, and frail patients.3

WEIGHT CHANGES

As mentioned, thyroid medications are weight-based, and big changes in weight can lead to changes in thyroid function studies. It is the lean body mass, rather than total body weight, that will affect the thyroid requirement.3 A quick review of the patient’s weight history needs to be done when thyroid function test results have changed.

GASTROINTESTINAL DISTURBANCES

Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the small intestine, and gastric acidity levels have an impact on absorption. Any acute or chronic conditions that affect these areas can alter medication absorption quite significantly. Commonly encountered diseases and conditions are H pylori–related gastritis, atrophic gastritis, celiac disease, and lactose intolerance. Treating these diseases and conditions can improve medication absorption.

I went through the list with the patient, but there was no applicable scenario. I adjusted his medication but went ahead and tested for tissue transglutaminase antibody IgA to rule out celiac disease; results came back mildly positive. The patient was referred to a gastroenterologist, who performed a small intestine biopsy for definitive diagnosis. This revealed “severe” celiac disease. A strict gluten-free diet was started, and the patient’s LT4 dose was adjusted, with regular monitoring, down to 150 μg/d.

Common symptoms of celiac disease include bloating, abdominal pain, and loose stool after consumption of gluten-containing meals. It should be noted that this patient denied all these symptoms, even though he was asked specifically about them. After he started a gluten-free diet, he reported that he actually felt “very calm” in his abdomen and realized he did have symptoms of celiac disease—but he’d had them for so long that he considered it normal. As is often the case, presence of symptoms would raise suspicion ... but lack of symptoms (or report thereof) does not rule out the disease.

CONCLUSION

Most patients with hypothyroidism are fairly well managed with relatively stable medication dosages, but there are subsets of patients who struggle to maintain euthyroid range. The latter require frequent office visits and dosage changes. Carefully reviewing the list of possible reasons for thyroid level changes can improve stability and patient quality of life, prevent complications of fluctuating thyroid levels, and reduce medical costs, such as repeated labs and frequent clinic visits.

REFERENCES

1. Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Hypothyroidism in Adults. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults [published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2013;19(1):175]. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(6):988-1028.

2. Sabate E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

3. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al; American Thyroid Association Task Force on Thyroid Hormone Replacement. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2014;24(12):1670-1751.

A 43-year-old man presents for his thyroid checkup. He has known hypothyroidism secondary to Hashimoto thyroiditis, also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. He is taking levothyroxine (LT4) 250 μg (two 125-μg tablets once per day). Review of his prior lab results and notes (see Table 1) reveals frequent dose changes (about every three to six months) and a high dosage of LT4, considering his weight (185 lb).

Patients with little or no residual thyroid function require replacement doses of LT4 at approximately 1.6 μg/kg/d, based on lean body weight.1 Since the case patient weighs 84 kg, the expected LT4 dosage would be around 125 to 150 μg/d.

This patient requires a significantly higher dose than expected, and his thyroid levels are fluctuating. These facts should trigger further investigation.

Important historical questions I consider when patients have frequent or significant fluctuations in TSH include

• Are you consistent in taking your medication?

• How do you take your thyroid medication?

• Are you taking any iron supplements, vitamins with iron, or contraceptive pills containing iron?

• Has there been any change in your other medication regimen(s) or medical condition(s)?

• Did you change pharmacies, or did the shape or color of your pill change?

• Have you experienced significant weight changes?

• Do you have any gastrointestinal complaints (nausea/vomiting/diarrhea/bloating)?

MEDICATION ADHERENCE

It is well known but still puzzling to hear that, overall, patients’ medication adherence is merely 50%.2 It is very important that you verify whether your patient is taking his/her medication consistently. Rather than asking “Are you taking your medications?” (to which they are more likely to answer “yes”), I ask “How many pills do you miss in a given week or month?”

For those who have a hard time remembering to take their medication on a regular basis, I recommend setting up a routine: Keep the medication at their bedside and take it first thing upon awakening, or place it beside the toothpaste so they see it every time they brush their teeth in the morning. Another option is of course to set up an alarm as a reminder.

Continue for rules for taking hypothyroid >>

RULES FOR TAKING HYPOTHYROID MEDICATIONS

Thyroid hormone replacement has a narrow therapeutic index, and a subtle change in dosage can significantly alter the therapeutic target. Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the jejunum/ileum, and an acidic pH in the stomach is optimal for thyroid absorption.3 Therefore, taking the medication on an empty stomach (fasting) with a full glass of water and waiting at least one hour before breakfast is recommended, if possible. An alternate option is to take it at bedtime, at least three hours after the last meal. Taking medication along with food, especially high-fiber and soy products, can decrease absorption of thyroid hormone, which may result in an unstable thyroid function test.

There are supplements and medications that can decrease hypothyroid medication absorption; it is recommended that patients separate these medications by four hours or more in order to minimize this interference. A full list is available in Table 2, but the most commonly encountered are iron supplements, calcium supplements, and proton pump inhibitors.2

In many patients—especially the elderly and those with multiple comorbidities that require polypharmacy—it can be very challenging, if not impossible, to isolate thyroid medication. For these patients, recommend that they be “consistent” with their routine to ensure they achieve a similar absorption rate each time. For example, a patient’s hypothyroid medication absorption might be reduced by 50% by taking it with omeprazole, but as long as the patient consistently takes the medication that way, she can have stable thyroid function.

NEW MEDICATION REGIMEN OR MEDICAL CONDITION

In addition to medications that can interfere with the absorption of thyroid hormone replacement, there are those that affect levels of thyroxine-binding globulin. This affects the bioavailability of thyroid hormones and alters thyroid status.

Thyroid hormones such as thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) are predominantly bound to carrier proteins, and < 1% is unbound (so-called free hormones). Changes in thyroid-binding proteins can alter free hormone levels and thereby change TSH levels. In disease-free euthyroid subjects, the body can compensate by adjusting hormone production for changes in binding proteins to keep the free hormone levels within normal ranges. However, patients who are at or near full replacement doses of hypothyroid medication cannot adjust to the changes.

In patients with hypothyroidism who are taking thyroid hormone replacement, medications or conditions that increase binding proteins will decrease free hormones (by increasing bound hormones) and thereby raise TSH (hypothyroid state). Vice versa, medications and conditions that decrease binding protein will increase free hormones (by decreasing bound hormones) and thereby lower TSH (thyrotoxic state). Table 3 lists commonly encountered medications and conditions associated with altered thyroid-binding proteins.1

It is important to consider pregnancy in women of childbearing age whose TSH has risen for no apparent reason, as their thyroid levels should be maintained in a narrow therapeutic range to prevent fetal complications. Details on thyroid disease during pregnancy can be found in the April 2015 Endocrine Consult, “Managing Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy.”

In women treated for hypothyroidism, starting or discontinuing estrogen-containing medications (birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy) often results in changes in thyroid status. It is a good practice to inform the patient about these changes and to recheck her thyroid labs four to eight weeks after she starts or discontinues estrogen, adjusting the dose if needed.

Continue for changes in manufacturer/brand >>

CHANGES IN MANUFACTURER/BRAND

There are currently multiple brands and generic manufacturers supplying hypothyroid medications and reports that absorption rates and bioavailability vary among them.2 Switching products can result in changes in thyroid status and in TSH levels.

Once a patient has reached euthyroid status, it is imperative to stay on the same dose from the same manufacturer. This may be challenging, as it can be affected by the patient’s insurance carrier, policy changes, or even a change in the pharmacy’s medication supplier. Although patients are supposed to be informed by the pharmacy when the manufacturer is being changed, you may want to educate them to check the shape, color, and dose of their pills and also verify that the manufacturer listed on the bottle is consistent each time they refill their hypothyroid medications. This is especially important for those who require a very narrow TSH target, such as young children, thyroid cancer patients, pregnant women, and frail patients.3

WEIGHT CHANGES

As mentioned, thyroid medications are weight-based, and big changes in weight can lead to changes in thyroid function studies. It is the lean body mass, rather than total body weight, that will affect the thyroid requirement.3 A quick review of the patient’s weight history needs to be done when thyroid function test results have changed.

GASTROINTESTINAL DISTURBANCES

Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the small intestine, and gastric acidity levels have an impact on absorption. Any acute or chronic conditions that affect these areas can alter medication absorption quite significantly. Commonly encountered diseases and conditions are H pylori–related gastritis, atrophic gastritis, celiac disease, and lactose intolerance. Treating these diseases and conditions can improve medication absorption.

I went through the list with the patient, but there was no applicable scenario. I adjusted his medication but went ahead and tested for tissue transglutaminase antibody IgA to rule out celiac disease; results came back mildly positive. The patient was referred to a gastroenterologist, who performed a small intestine biopsy for definitive diagnosis. This revealed “severe” celiac disease. A strict gluten-free diet was started, and the patient’s LT4 dose was adjusted, with regular monitoring, down to 150 μg/d.

Common symptoms of celiac disease include bloating, abdominal pain, and loose stool after consumption of gluten-containing meals. It should be noted that this patient denied all these symptoms, even though he was asked specifically about them. After he started a gluten-free diet, he reported that he actually felt “very calm” in his abdomen and realized he did have symptoms of celiac disease—but he’d had them for so long that he considered it normal. As is often the case, presence of symptoms would raise suspicion ... but lack of symptoms (or report thereof) does not rule out the disease.

CONCLUSION

Most patients with hypothyroidism are fairly well managed with relatively stable medication dosages, but there are subsets of patients who struggle to maintain euthyroid range. The latter require frequent office visits and dosage changes. Carefully reviewing the list of possible reasons for thyroid level changes can improve stability and patient quality of life, prevent complications of fluctuating thyroid levels, and reduce medical costs, such as repeated labs and frequent clinic visits.

REFERENCES

1. Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Hypothyroidism in Adults. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults [published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2013;19(1):175]. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(6):988-1028.

2. Sabate E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

3. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al; American Thyroid Association Task Force on Thyroid Hormone Replacement. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2014;24(12):1670-1751.

A 43-year-old man presents for his thyroid checkup. He has known hypothyroidism secondary to Hashimoto thyroiditis, also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. He is taking levothyroxine (LT4) 250 μg (two 125-μg tablets once per day). Review of his prior lab results and notes (see Table 1) reveals frequent dose changes (about every three to six months) and a high dosage of LT4, considering his weight (185 lb).

Patients with little or no residual thyroid function require replacement doses of LT4 at approximately 1.6 μg/kg/d, based on lean body weight.1 Since the case patient weighs 84 kg, the expected LT4 dosage would be around 125 to 150 μg/d.

This patient requires a significantly higher dose than expected, and his thyroid levels are fluctuating. These facts should trigger further investigation.

Important historical questions I consider when patients have frequent or significant fluctuations in TSH include

• Are you consistent in taking your medication?

• How do you take your thyroid medication?

• Are you taking any iron supplements, vitamins with iron, or contraceptive pills containing iron?

• Has there been any change in your other medication regimen(s) or medical condition(s)?

• Did you change pharmacies, or did the shape or color of your pill change?

• Have you experienced significant weight changes?

• Do you have any gastrointestinal complaints (nausea/vomiting/diarrhea/bloating)?

MEDICATION ADHERENCE

It is well known but still puzzling to hear that, overall, patients’ medication adherence is merely 50%.2 It is very important that you verify whether your patient is taking his/her medication consistently. Rather than asking “Are you taking your medications?” (to which they are more likely to answer “yes”), I ask “How many pills do you miss in a given week or month?”

For those who have a hard time remembering to take their medication on a regular basis, I recommend setting up a routine: Keep the medication at their bedside and take it first thing upon awakening, or place it beside the toothpaste so they see it every time they brush their teeth in the morning. Another option is of course to set up an alarm as a reminder.

Continue for rules for taking hypothyroid >>

RULES FOR TAKING HYPOTHYROID MEDICATIONS

Thyroid hormone replacement has a narrow therapeutic index, and a subtle change in dosage can significantly alter the therapeutic target. Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the jejunum/ileum, and an acidic pH in the stomach is optimal for thyroid absorption.3 Therefore, taking the medication on an empty stomach (fasting) with a full glass of water and waiting at least one hour before breakfast is recommended, if possible. An alternate option is to take it at bedtime, at least three hours after the last meal. Taking medication along with food, especially high-fiber and soy products, can decrease absorption of thyroid hormone, which may result in an unstable thyroid function test.

There are supplements and medications that can decrease hypothyroid medication absorption; it is recommended that patients separate these medications by four hours or more in order to minimize this interference. A full list is available in Table 2, but the most commonly encountered are iron supplements, calcium supplements, and proton pump inhibitors.2

In many patients—especially the elderly and those with multiple comorbidities that require polypharmacy—it can be very challenging, if not impossible, to isolate thyroid medication. For these patients, recommend that they be “consistent” with their routine to ensure they achieve a similar absorption rate each time. For example, a patient’s hypothyroid medication absorption might be reduced by 50% by taking it with omeprazole, but as long as the patient consistently takes the medication that way, she can have stable thyroid function.

NEW MEDICATION REGIMEN OR MEDICAL CONDITION

In addition to medications that can interfere with the absorption of thyroid hormone replacement, there are those that affect levels of thyroxine-binding globulin. This affects the bioavailability of thyroid hormones and alters thyroid status.

Thyroid hormones such as thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) are predominantly bound to carrier proteins, and < 1% is unbound (so-called free hormones). Changes in thyroid-binding proteins can alter free hormone levels and thereby change TSH levels. In disease-free euthyroid subjects, the body can compensate by adjusting hormone production for changes in binding proteins to keep the free hormone levels within normal ranges. However, patients who are at or near full replacement doses of hypothyroid medication cannot adjust to the changes.

In patients with hypothyroidism who are taking thyroid hormone replacement, medications or conditions that increase binding proteins will decrease free hormones (by increasing bound hormones) and thereby raise TSH (hypothyroid state). Vice versa, medications and conditions that decrease binding protein will increase free hormones (by decreasing bound hormones) and thereby lower TSH (thyrotoxic state). Table 3 lists commonly encountered medications and conditions associated with altered thyroid-binding proteins.1

It is important to consider pregnancy in women of childbearing age whose TSH has risen for no apparent reason, as their thyroid levels should be maintained in a narrow therapeutic range to prevent fetal complications. Details on thyroid disease during pregnancy can be found in the April 2015 Endocrine Consult, “Managing Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy.”

In women treated for hypothyroidism, starting or discontinuing estrogen-containing medications (birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy) often results in changes in thyroid status. It is a good practice to inform the patient about these changes and to recheck her thyroid labs four to eight weeks after she starts or discontinues estrogen, adjusting the dose if needed.

Continue for changes in manufacturer/brand >>

CHANGES IN MANUFACTURER/BRAND

There are currently multiple brands and generic manufacturers supplying hypothyroid medications and reports that absorption rates and bioavailability vary among them.2 Switching products can result in changes in thyroid status and in TSH levels.

Once a patient has reached euthyroid status, it is imperative to stay on the same dose from the same manufacturer. This may be challenging, as it can be affected by the patient’s insurance carrier, policy changes, or even a change in the pharmacy’s medication supplier. Although patients are supposed to be informed by the pharmacy when the manufacturer is being changed, you may want to educate them to check the shape, color, and dose of their pills and also verify that the manufacturer listed on the bottle is consistent each time they refill their hypothyroid medications. This is especially important for those who require a very narrow TSH target, such as young children, thyroid cancer patients, pregnant women, and frail patients.3

WEIGHT CHANGES

As mentioned, thyroid medications are weight-based, and big changes in weight can lead to changes in thyroid function studies. It is the lean body mass, rather than total body weight, that will affect the thyroid requirement.3 A quick review of the patient’s weight history needs to be done when thyroid function test results have changed.

GASTROINTESTINAL DISTURBANCES

Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the small intestine, and gastric acidity levels have an impact on absorption. Any acute or chronic conditions that affect these areas can alter medication absorption quite significantly. Commonly encountered diseases and conditions are H pylori–related gastritis, atrophic gastritis, celiac disease, and lactose intolerance. Treating these diseases and conditions can improve medication absorption.

I went through the list with the patient, but there was no applicable scenario. I adjusted his medication but went ahead and tested for tissue transglutaminase antibody IgA to rule out celiac disease; results came back mildly positive. The patient was referred to a gastroenterologist, who performed a small intestine biopsy for definitive diagnosis. This revealed “severe” celiac disease. A strict gluten-free diet was started, and the patient’s LT4 dose was adjusted, with regular monitoring, down to 150 μg/d.

Common symptoms of celiac disease include bloating, abdominal pain, and loose stool after consumption of gluten-containing meals. It should be noted that this patient denied all these symptoms, even though he was asked specifically about them. After he started a gluten-free diet, he reported that he actually felt “very calm” in his abdomen and realized he did have symptoms of celiac disease—but he’d had them for so long that he considered it normal. As is often the case, presence of symptoms would raise suspicion ... but lack of symptoms (or report thereof) does not rule out the disease.

CONCLUSION

Most patients with hypothyroidism are fairly well managed with relatively stable medication dosages, but there are subsets of patients who struggle to maintain euthyroid range. The latter require frequent office visits and dosage changes. Carefully reviewing the list of possible reasons for thyroid level changes can improve stability and patient quality of life, prevent complications of fluctuating thyroid levels, and reduce medical costs, such as repeated labs and frequent clinic visits.

REFERENCES

1. Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Hypothyroidism in Adults. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults [published correction appears in Endocr Pract. 2013;19(1):175]. Endocr Pract. 2012;18(6):988-1028.

2. Sabate E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

3. Jonklaas J, Bianco AC, Bauer AJ, et al; American Thyroid Association Task Force on Thyroid Hormone Replacement. Guidelines for the treatment of hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2014;24(12):1670-1751.

Be Sure to Look for Secondary Diabetes

A 63-year-old Hispanic woman was referred to endocrinology by her primary care provider for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which was diagnosed 16 years ago. Her antidiabetic medications included insulin glargine (55 U bid), metformin (1,000 mg bid), and glipizide (10 mg bid). She also had known dyslipidemia, hypertension, and depression. There was a history of poorly controlled glucose (A1C between 9% and 13% in the past three years).

This was a relatively common new patient consult in our endocrine clinic. Upon entering the room, I was greeted by the patient and two family members. I quickly noticed the patient’s facial plethora and central obesity with comparatively thin extremities. Further inquiry revealed that the greatest challenge for the patient and her family was her bouts of severe depression, during which she would stop caring and cease to take her medications.

During the physical exam, mild but not significant supraclavicular and dorsocervical fat pads were appreciated. The exam was otherwise unremarkable, with no purple striae on the torso, abdomen, breasts, and extremities.

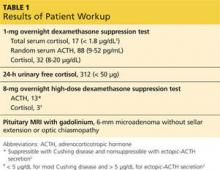

In addition to routine diabetes lab tests (ie, A1C, chemistry panel, lipid panel, urine microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio), an overnight 1-mg oral dexamethasone suppression test was ordered. Results of the latter were abnormal, and further workup confirmed Cushing disease (see Table 1 for results). The patient was referred for neurosurgery.

Continue for Discussion >>

DISCUSSION: SECONDARY DIABETES

It is well known that the prevalence of diabetes is skyrocketing, and medical offices are filled with affected patients. According to a 2011 report from the CDC, 90% to 95% of all diabetes cases are type 2, 5% are type 1 (autoimmune), and the rest (about 1% to 5%) are “other types” of diabetes.3 Due to these disproportionate statistics, clinicians often overlook the possibility of uncommon etiologies and assume all patients with diabetes have type 2—especially when the patient is overweight or obese.

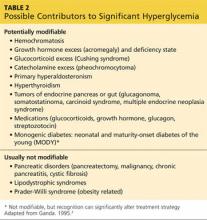

Table 2 lists conditions and medications that may contribute to significant hyperglycemia.4 Some contributors are rather obvious (eg, status post pancreatectomy) or have no impact on treatment strategy (eg, chromosomal defects such as Down or Turner syndrome). However, certain conditions, such as Cushing syndrome, acromegaly, and hemochromatosis, can be relatively hard to recognize due to the variable rate of clinical manifestation, especially in the earlier stages of the disease. Experts have raised concerns that the prevalence of secondary diabetes (1% to 5%) may actually be underestimated due to “misdiagnosis” as T2DM.

Early detection of the underlying disorder, followed by initiation of appropriate treatment, is critical. It will not only improve but also may resolve the patient’s hyperglycemia, and it may also reverse or stop the damage to other vital organs.

The case patient had an unfortunate situation in which her Cushing syndrome was masked by commonly encountered diagnoses of hypertension, T2DM, obesity, and depression. Cushing is an easy diagnosis to miss, since it has an insidious onset and it can take more than five years for some of the physical findings to become evident.

Pancreatic cancer is another uncommon but critical disease worth mentioning. Pancreatic cancer should be in the differential diagnosis for previously euglycemic patients who experience abrupt elevation of glucose or previously well-managed patients whose glucose values quickly get out of control without obvious cause (eg, medication cessation, addition of glucocorticoid therapy, uncontrolled diet).

In our practice, we have encountered three patients with pancreatic cancer in this setting. The only sign was a sudden rise in glucose (300 to 500 mg/dL throughout the day) in patients whose A1C had been low (in the 6% range) with one or two oral medications. Thorough history taking did not reveal any potential causes for sudden hyperglycemia. Only one patient had a palpable mass on abdominal exam and elevated liver enzymes and bilirubin. Unfortunately, that patient died eight months later. The other two had favorable outcomes from surgery and chemotherapy. Early detection was the key for those two patients.

Next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Since the majority of patients with diabetes have T2DM, it is easy to “default” and start treating all patients as such, especially if they are overweight or obese. However, up to 5% of patients actually have underlying disease that may cause or worsen their diabetic status. Overlooking these rare conditions can be detrimental to the patient, as it will adversely affect not only glycemic control but more importantly, overall health. Identifying the underlying disease will allow the patient to receive appropriate treatment, which may offload a significant burden on glycemic control and in some cases, cure the hyperglycemia.

REFERENCES

1. Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al. The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1526-1540.

2. Nieman LK. Establishing the cause of Cushing’s syndrome. Up-to-Date. www.uptodate.com/contents/establishing-the-cause-of-cushings-syndrome. Accessed June 24, 2015.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2015.

4. Ganda OP. Prevalence and incidence of secondary and other types of diabetes. In: Diabetes in America. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1995:69-84.

A 63-year-old Hispanic woman was referred to endocrinology by her primary care provider for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which was diagnosed 16 years ago. Her antidiabetic medications included insulin glargine (55 U bid), metformin (1,000 mg bid), and glipizide (10 mg bid). She also had known dyslipidemia, hypertension, and depression. There was a history of poorly controlled glucose (A1C between 9% and 13% in the past three years).

This was a relatively common new patient consult in our endocrine clinic. Upon entering the room, I was greeted by the patient and two family members. I quickly noticed the patient’s facial plethora and central obesity with comparatively thin extremities. Further inquiry revealed that the greatest challenge for the patient and her family was her bouts of severe depression, during which she would stop caring and cease to take her medications.

During the physical exam, mild but not significant supraclavicular and dorsocervical fat pads were appreciated. The exam was otherwise unremarkable, with no purple striae on the torso, abdomen, breasts, and extremities.

In addition to routine diabetes lab tests (ie, A1C, chemistry panel, lipid panel, urine microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio), an overnight 1-mg oral dexamethasone suppression test was ordered. Results of the latter were abnormal, and further workup confirmed Cushing disease (see Table 1 for results). The patient was referred for neurosurgery.

Continue for Discussion >>

DISCUSSION: SECONDARY DIABETES

It is well known that the prevalence of diabetes is skyrocketing, and medical offices are filled with affected patients. According to a 2011 report from the CDC, 90% to 95% of all diabetes cases are type 2, 5% are type 1 (autoimmune), and the rest (about 1% to 5%) are “other types” of diabetes.3 Due to these disproportionate statistics, clinicians often overlook the possibility of uncommon etiologies and assume all patients with diabetes have type 2—especially when the patient is overweight or obese.

Table 2 lists conditions and medications that may contribute to significant hyperglycemia.4 Some contributors are rather obvious (eg, status post pancreatectomy) or have no impact on treatment strategy (eg, chromosomal defects such as Down or Turner syndrome). However, certain conditions, such as Cushing syndrome, acromegaly, and hemochromatosis, can be relatively hard to recognize due to the variable rate of clinical manifestation, especially in the earlier stages of the disease. Experts have raised concerns that the prevalence of secondary diabetes (1% to 5%) may actually be underestimated due to “misdiagnosis” as T2DM.

Early detection of the underlying disorder, followed by initiation of appropriate treatment, is critical. It will not only improve but also may resolve the patient’s hyperglycemia, and it may also reverse or stop the damage to other vital organs.

The case patient had an unfortunate situation in which her Cushing syndrome was masked by commonly encountered diagnoses of hypertension, T2DM, obesity, and depression. Cushing is an easy diagnosis to miss, since it has an insidious onset and it can take more than five years for some of the physical findings to become evident.

Pancreatic cancer is another uncommon but critical disease worth mentioning. Pancreatic cancer should be in the differential diagnosis for previously euglycemic patients who experience abrupt elevation of glucose or previously well-managed patients whose glucose values quickly get out of control without obvious cause (eg, medication cessation, addition of glucocorticoid therapy, uncontrolled diet).

In our practice, we have encountered three patients with pancreatic cancer in this setting. The only sign was a sudden rise in glucose (300 to 500 mg/dL throughout the day) in patients whose A1C had been low (in the 6% range) with one or two oral medications. Thorough history taking did not reveal any potential causes for sudden hyperglycemia. Only one patient had a palpable mass on abdominal exam and elevated liver enzymes and bilirubin. Unfortunately, that patient died eight months later. The other two had favorable outcomes from surgery and chemotherapy. Early detection was the key for those two patients.

Next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Since the majority of patients with diabetes have T2DM, it is easy to “default” and start treating all patients as such, especially if they are overweight or obese. However, up to 5% of patients actually have underlying disease that may cause or worsen their diabetic status. Overlooking these rare conditions can be detrimental to the patient, as it will adversely affect not only glycemic control but more importantly, overall health. Identifying the underlying disease will allow the patient to receive appropriate treatment, which may offload a significant burden on glycemic control and in some cases, cure the hyperglycemia.

REFERENCES

1. Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al. The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1526-1540.

2. Nieman LK. Establishing the cause of Cushing’s syndrome. Up-to-Date. www.uptodate.com/contents/establishing-the-cause-of-cushings-syndrome. Accessed June 24, 2015.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2015.

4. Ganda OP. Prevalence and incidence of secondary and other types of diabetes. In: Diabetes in America. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1995:69-84.

A 63-year-old Hispanic woman was referred to endocrinology by her primary care provider for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which was diagnosed 16 years ago. Her antidiabetic medications included insulin glargine (55 U bid), metformin (1,000 mg bid), and glipizide (10 mg bid). She also had known dyslipidemia, hypertension, and depression. There was a history of poorly controlled glucose (A1C between 9% and 13% in the past three years).

This was a relatively common new patient consult in our endocrine clinic. Upon entering the room, I was greeted by the patient and two family members. I quickly noticed the patient’s facial plethora and central obesity with comparatively thin extremities. Further inquiry revealed that the greatest challenge for the patient and her family was her bouts of severe depression, during which she would stop caring and cease to take her medications.

During the physical exam, mild but not significant supraclavicular and dorsocervical fat pads were appreciated. The exam was otherwise unremarkable, with no purple striae on the torso, abdomen, breasts, and extremities.

In addition to routine diabetes lab tests (ie, A1C, chemistry panel, lipid panel, urine microalbumin-to-creatinine ratio), an overnight 1-mg oral dexamethasone suppression test was ordered. Results of the latter were abnormal, and further workup confirmed Cushing disease (see Table 1 for results). The patient was referred for neurosurgery.

Continue for Discussion >>

DISCUSSION: SECONDARY DIABETES

It is well known that the prevalence of diabetes is skyrocketing, and medical offices are filled with affected patients. According to a 2011 report from the CDC, 90% to 95% of all diabetes cases are type 2, 5% are type 1 (autoimmune), and the rest (about 1% to 5%) are “other types” of diabetes.3 Due to these disproportionate statistics, clinicians often overlook the possibility of uncommon etiologies and assume all patients with diabetes have type 2—especially when the patient is overweight or obese.

Table 2 lists conditions and medications that may contribute to significant hyperglycemia.4 Some contributors are rather obvious (eg, status post pancreatectomy) or have no impact on treatment strategy (eg, chromosomal defects such as Down or Turner syndrome). However, certain conditions, such as Cushing syndrome, acromegaly, and hemochromatosis, can be relatively hard to recognize due to the variable rate of clinical manifestation, especially in the earlier stages of the disease. Experts have raised concerns that the prevalence of secondary diabetes (1% to 5%) may actually be underestimated due to “misdiagnosis” as T2DM.

Early detection of the underlying disorder, followed by initiation of appropriate treatment, is critical. It will not only improve but also may resolve the patient’s hyperglycemia, and it may also reverse or stop the damage to other vital organs.

The case patient had an unfortunate situation in which her Cushing syndrome was masked by commonly encountered diagnoses of hypertension, T2DM, obesity, and depression. Cushing is an easy diagnosis to miss, since it has an insidious onset and it can take more than five years for some of the physical findings to become evident.

Pancreatic cancer is another uncommon but critical disease worth mentioning. Pancreatic cancer should be in the differential diagnosis for previously euglycemic patients who experience abrupt elevation of glucose or previously well-managed patients whose glucose values quickly get out of control without obvious cause (eg, medication cessation, addition of glucocorticoid therapy, uncontrolled diet).

In our practice, we have encountered three patients with pancreatic cancer in this setting. The only sign was a sudden rise in glucose (300 to 500 mg/dL throughout the day) in patients whose A1C had been low (in the 6% range) with one or two oral medications. Thorough history taking did not reveal any potential causes for sudden hyperglycemia. Only one patient had a palpable mass on abdominal exam and elevated liver enzymes and bilirubin. Unfortunately, that patient died eight months later. The other two had favorable outcomes from surgery and chemotherapy. Early detection was the key for those two patients.

Next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Since the majority of patients with diabetes have T2DM, it is easy to “default” and start treating all patients as such, especially if they are overweight or obese. However, up to 5% of patients actually have underlying disease that may cause or worsen their diabetic status. Overlooking these rare conditions can be detrimental to the patient, as it will adversely affect not only glycemic control but more importantly, overall health. Identifying the underlying disease will allow the patient to receive appropriate treatment, which may offload a significant burden on glycemic control and in some cases, cure the hyperglycemia.

REFERENCES

1. Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al. The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1526-1540.

2. Nieman LK. Establishing the cause of Cushing’s syndrome. Up-to-Date. www.uptodate.com/contents/establishing-the-cause-of-cushings-syndrome. Accessed June 24, 2015.

3. CDC. National Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/ndfs_2011.pdf. Accessed June 24, 2015.

4. Ganda OP. Prevalence and incidence of secondary and other types of diabetes. In: Diabetes in America. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1995:69-84.

Weighing the Options for Obesity Meds

In June 2013, the American Medical Association classified obesity as a disease. Since then, several medical societies have published guidelines to help clinicians improve care of affected patients. One avenue is, of course, pharmacologic treatment.

Until recently, there was only one FDA-approved medication for chronic weight loss on the market: orlistat, which was approved in 1999. (Phentermine and diethylpropion are only indicated for short-term use). After a long hiatus, the FDA approved two additional agents (phentermine/topiramate and lorcaserin)in 2012 and another two (liraglutide and bupropion/naltrexone) in 2014.

While clinicians appreciate having options for managing their patients’ conditions, in this case, many are overwhelmed by the choices. Most health care providers have not received formal training in obesity management. This column will attempt to fill the information gap in terms of what agents are available and what factors should be assessed before prescribing any of them.

Proviso: Experts claim obesity is a chronic disease, similar to hypertension, and should be managed as such. Although not discussed here, the most important aspect of weight loss and maintenance is lifestyle intervention (diet, exercise, and behavioral modification). It should be emphasized that no medication works by itself; all should be used as an adjunct tool to reinforce adherence to lifestyle changes.1 Furthermore, patients may be disappointed to learn that without these changes, the weight may return when they cease medication use.

CASE Deb, age 61, presents to your office for routine follow-up. She has a history of type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, depression, and chronic back pain due to a herniated disc. Her medications include insulin glargine, glyburide, pioglitazone, atorvastatin, metoprolol, paroxetine, and acetaminophen/hydrocodone.

Her vital signs include a blood pressure of 143/91 mm Hg and a pulse of 93 beats/min. She has a BMI of 37 and a waist circumference of 35 in.

Deb, concerned about her weight, would like to discuss weight-loss options. She has tried three different commercial programs; each time, she was able to lose 30 to 50 lb in three to six months but regained the weight once she stopped the program. She reports excessive appetite as the main reason for her rebound weight gain. Her exercise is limited due to her back pain.

She recently tried OTC orlistat but could not tolerate it due to flatulence and fecal urgency. She reports an incident in which she couldn’t reach the bathroom in time.

Continue for Discussion >>

DISCUSSION

The Endocrine Society’s recommended approaches to obesity management include diet, exercise, and behavioral modification for patients with a BMI ≥ 25. The addition of pharmacotherapy can be considered for those with a BMI ≥ 30 or with a BMI ≥ 27 and one or more weight-related comorbidities (eg, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension). This matches the FDA-approved product labeling for chronic weight-loss medications. Bariatric surgery should be considered for patients with a BMI ≥ 40 or with a BMI ≥ 35 and at least one weight-related comorbidity.

Orlistat

Orlistat is available OTC in a 60-mg thrice-daily form. A higher dosage (120 mg tid) is available via prescription. Orlistat decreases fat absorption in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract by inhibiting GI lipase. Average weight loss with orlistat is 3% at first and second year, and, when compared with placebo, 2.4% greater at four years.2

Orlistat should be prescribed with a multivitamin due to decreased absorption of fat-soluble vitamins. It is contraindicated in patients with malabsorption syndrome and gallbladder disease (> 2% incidence3). It can increase cyclosporine exposure, and rare cases of liver failure have been reported. The most common adverse effect is related to steatorrhea. Of the available options, orlistat is the only medication that has no effect on neurohormonal regulation in appetite control and metabolic rate, which may be a limiting factor.

CASE POINT Due to Deb’s intolerance of and embarrassment with GI adverse effects, she requests an alternative medication.

Lorcaserin

Lorcaserin is a selective serotonin 2C receptor agonist that reduces appetite by affecting anorexigenic pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in the hypothalamus. Of note, lorcaserin “selects” the 2C receptor instead of 2A and 2B; 2B receptors are found in both aortic and mitral valves, which may explain the association between fenfluramine/phentermine (commonly known as “fen/phen” and withdrawn from the market in 1997) and possible cardiac valvulopathy. (Fenfluramine is an amphetamine derivative that nonselectively stimulates serotonin release and inhibits reuptake.)

Lorcaserin comes in a 10-mg twice-daily dosage. In studies, patients taking lorcaserin had an average weight loss of 3.3% more than those taking placebo at one year; weight loss was maintained through the second year for those who continued on medication. However, those who stopped the medication at one year had regained their weight by the two-year mark.4

It is recommended that the medication be discontinued if patients don’t achieve a loss of more than 5% of body weight by 12 weeks.

In a study that enrolled diabetic patients, lorcaserin also demonstrated a 0.9% reduction in A1C, which is similar to or even better than some oral antidiabetic medications.4 However, since the manufacturer was not planning for an antidiabetic indication, A1C was only a secondary endpoint. The reduction is most likely due to decreased caloric intake and weight loss.

The most common adverse effects of lorcaserin include headache, dizziness, and fatigue. The discontinuation rate due to intolerance was 8.6%, compared to 6.7% with placebo.5

Although this was not observed in clinical studies, co-administration of lorcaserin (a serotonin receptor agonist) with other serotonergic or antidopaminergic agents can theoretically cause serotonin syndrome or neuroleptic malignant syndrome–like reactions. Caution is therefore advisable when prescribing these agents. The package insert carries a warning for cardiac valvulopathy due to fen/phen’s history and a lack of long-term cardiovascular safety data.

CASE POINT Deb is taking paroxetine (an SSRI) for her depression. Since you are concerned about serotonin syndrome, you decide to keep exploring options. Checking the package insert for phentermine/topiramate, you learn that it does not have a potential adverse reaction related to co-administration with SSRIs.

Phentermine/Topiramate

Phentermine, a sympathomimetic medication, was approved for short-term (12-week) use for weight loss in the 1960s. Topiramate, an antiseizure and migraine prophylactic medication, enhances appetite suppression—although the exact mechanism of action is unknown.1

Four once-daily doses are available: 3.75/23 mg, 7.5/46 mg, 11.25/69 mg, and 15/92 mg. Dosing starts with 3.75/23 mg for two weeks, then increases to 7.5/46 mg. If a loss of 5% or more of body weight is achieved, the patient can continue the dosage; if not, it can be increased to 11.25/69 mg for two weeks and then to 15/92 mg. The average weight loss for mid and maximum dose was 6.6% and 8.6% greater than placebo at one year.5

Commonly reported adverse effects include paraesthesia, dysgeusia (distortion of sense of taste), dizziness, insomnia, constipation, and dry mouth. Due to phentermine’s sympathomimetic action, mild increases in heart rate and blood pressure were reported. The Endocrine Society recommends against the use of phentermine in patients with uncontrolled hypertension and a history of heart disease.1

Weight loss is generally not recommended during pregnancy, and all weight loss medications are classified as category X for pregnancy. Strict caution is advised with this particular agent, as topiramate has known teratogenicity and therefore comes with a Risk Evaluation Mitigation Strategy. Patients must be advised to use appropriate contraception while taking topiramate, and a pregnancy test should be performed before medication commencement and monthly thereafter.

Abrupt cessation of topiramate can cause seizure. When taking the 15/92-mg dosage, the patient should reduce to one tablet every other day for at least one week before discontinuation.

CASE POINT Deb’s blood pressure is still not at goal. This, along with her history of atrial fibrillation and high pulse, prompts you to consider another option.

Bupropion/Naltrexone

Bupropion, a widely used antidepressant, inhibits the uptake of norepinephrine and dopamine and thereby blocks the reward pathway that various foods can induce. Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, blocks the opioid pathway and can be helpful in enhancing weight loss.

This combination comes in an 8/90-mg tablet. The suggested titration regimen is to start with one tablet per day and increase by one tablet every week, up to the maximum dosage of two tablets twice a day. Average weight loss was 3.1% greater than placebo at one year with the maximum dosage. An A1C reduction of 0.6% was seen in diabetic patients.6 It is recommended to stop the medication and seek an alternative treatment option if > 5% loss of body weight is not achieved by 12 weeks.

GI adverse effects (eg, nausea and vomiting) are common; these can be reduced with a slower titration regimen or by prescribing a maximum of one tablet twice daily (instead of two). Every antidepressant carries suicidal risk, and caution is advised with their use. Bupropion can also lower the seizure threshold, and it is contraindicated for patients with seizure disorder. It is also contraindicated in patients who are undergoing abrupt cessation of alcohol, benzodiazepines, or barbiturates. It can increase pulse and blood pressure during early titration; regular blood pressure monitoring is warranted.

CASE POINT Due to Deb’s opioid usage and uncontrolled hypertension, you discuss a final option that was recently approved for weight loss.

Liraglutide

This glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP1) receptor agonist affects the brain to suppress/control appetite, slows down gastric emptying, and induces early satiety. A 3-mg dosage was approved in December 2014, but 0.6-, 1.2-, and 1.8-mg dosages have been available since 2010 for patients with type 2 diabetes.

Average weight loss was 4.5% greater than placebo at one year.7 If < 4% weight loss is achieved by 16 weeks, consider using an alternative agent.

The most common adverse effect is GI upset, which could be related to the mechanism of action (slower gastric emptying). Although self-reported GI upset was high (39%), the actual discontinuation rate was low (2.9% for nausea, 1.7% for vomiting, and 1.4% for diarrhea).3

This adverse effect could, in certain contexts, be considered “wanted,” since it discourages overeating or eating too quickly. My clinical pearl is to tell patients taking liraglutide that they are “trapped” and have to eat smaller portions and eat more slowly or they will be more prone to GI effects. With this strategy, we can encourage portion control and responsibility for behavior. (Please note that this is my experience with the diabetic dosage of liraglutide; I do not have any clinical experience with the obesity dosage, which was not clinically available at the time of writing.)

Both branded versions of liraglutide carry a black-box warning for thyroid C-cell tumors, which were observed in rodents but unproven in humans. The medication is contraindicated in patients with medullary thyroid cancer or with multiple endocrine neoplasia 2 syndrome. Increased rates of acute pancreatitis, cholecystitis, and cholelithiasis were seen in studies, and caution is advised.

Continue for A Word About Meds That Cause Weight Gain >>

A WORD ABOUT MEDS THAT CAUSE WEIGHT GAIN

The Endocrine Society has published a list of medications that can influence weight gain, along with suggestions for alternative agents that are either weight neutral or promote weight loss.

Note that our case patient, Deb, is taking insulin, a sulfonylurea (glyburide), and thiazolidinedione (pioglitazone) for diabetes—all of which can promote weight gain. Guidelines suggest choosing metformin, DPP4 inhibitors, GLP1 agonists, amylin analog, and SGLT2 inhibitors instead when weight gain is a major concern.1

Guidelines also suggest using ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers instead of β-blockers as firstline antihypertensive therapy for diabetic patients.1 Adequate blood pressure and lipid control are imperative in diabetes management.

CASE POINT Deb would need better hypertension control before she considers weight-loss medication. Since she is also taking paroxetine, which among SSRIs is associated with greatest weight gain, a changed to fluoxetine or sertraline should be considered.2

Next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

There are now five medications approved by the FDA for chronic weight loss, with more to come. Agents with different mechanisms of action give us options to help obese patients and hopefully reduce and prevent obesity-related complications. It is important for clinicians to be competent in managing obesity, especially since we live in an era in which the disease is considered pandemic.

REFERENCES

1. Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH, et al; Endocrine Society. Pharmacological management of obesity: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-362.

2. Xenical [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech USA, Inc; 2012.

3. Fujioka K. Safety and tolerability of medications approved for chronic weight management. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;22 (suppl 1):S7-S11.

4. Belviq [package insert]. Woodcliff Lake, NJ: Eisai Inc; 2015.

5. Qsymia [package insert]. Mountain View, CA: Vivus, Inc; 2013.

6. Contrave [package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda USA, Inc; 2014.

7. Saxenda [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk; 2014.

In June 2013, the American Medical Association classified obesity as a disease. Since then, several medical societies have published guidelines to help clinicians improve care of affected patients. One avenue is, of course, pharmacologic treatment.

Until recently, there was only one FDA-approved medication for chronic weight loss on the market: orlistat, which was approved in 1999. (Phentermine and diethylpropion are only indicated for short-term use). After a long hiatus, the FDA approved two additional agents (phentermine/topiramate and lorcaserin)in 2012 and another two (liraglutide and bupropion/naltrexone) in 2014.

While clinicians appreciate having options for managing their patients’ conditions, in this case, many are overwhelmed by the choices. Most health care providers have not received formal training in obesity management. This column will attempt to fill the information gap in terms of what agents are available and what factors should be assessed before prescribing any of them.

Proviso: Experts claim obesity is a chronic disease, similar to hypertension, and should be managed as such. Although not discussed here, the most important aspect of weight loss and maintenance is lifestyle intervention (diet, exercise, and behavioral modification). It should be emphasized that no medication works by itself; all should be used as an adjunct tool to reinforce adherence to lifestyle changes.1 Furthermore, patients may be disappointed to learn that without these changes, the weight may return when they cease medication use.

CASE Deb, age 61, presents to your office for routine follow-up. She has a history of type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, depression, and chronic back pain due to a herniated disc. Her medications include insulin glargine, glyburide, pioglitazone, atorvastatin, metoprolol, paroxetine, and acetaminophen/hydrocodone.

Her vital signs include a blood pressure of 143/91 mm Hg and a pulse of 93 beats/min. She has a BMI of 37 and a waist circumference of 35 in.

Deb, concerned about her weight, would like to discuss weight-loss options. She has tried three different commercial programs; each time, she was able to lose 30 to 50 lb in three to six months but regained the weight once she stopped the program. She reports excessive appetite as the main reason for her rebound weight gain. Her exercise is limited due to her back pain.

She recently tried OTC orlistat but could not tolerate it due to flatulence and fecal urgency. She reports an incident in which she couldn’t reach the bathroom in time.

Continue for Discussion >>

DISCUSSION

The Endocrine Society’s recommended approaches to obesity management include diet, exercise, and behavioral modification for patients with a BMI ≥ 25. The addition of pharmacotherapy can be considered for those with a BMI ≥ 30 or with a BMI ≥ 27 and one or more weight-related comorbidities (eg, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension). This matches the FDA-approved product labeling for chronic weight-loss medications. Bariatric surgery should be considered for patients with a BMI ≥ 40 or with a BMI ≥ 35 and at least one weight-related comorbidity.

Orlistat

Orlistat is available OTC in a 60-mg thrice-daily form. A higher dosage (120 mg tid) is available via prescription. Orlistat decreases fat absorption in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract by inhibiting GI lipase. Average weight loss with orlistat is 3% at first and second year, and, when compared with placebo, 2.4% greater at four years.2

Orlistat should be prescribed with a multivitamin due to decreased absorption of fat-soluble vitamins. It is contraindicated in patients with malabsorption syndrome and gallbladder disease (> 2% incidence3). It can increase cyclosporine exposure, and rare cases of liver failure have been reported. The most common adverse effect is related to steatorrhea. Of the available options, orlistat is the only medication that has no effect on neurohormonal regulation in appetite control and metabolic rate, which may be a limiting factor.

CASE POINT Due to Deb’s intolerance of and embarrassment with GI adverse effects, she requests an alternative medication.

Lorcaserin

Lorcaserin is a selective serotonin 2C receptor agonist that reduces appetite by affecting anorexigenic pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons in the hypothalamus. Of note, lorcaserin “selects” the 2C receptor instead of 2A and 2B; 2B receptors are found in both aortic and mitral valves, which may explain the association between fenfluramine/phentermine (commonly known as “fen/phen” and withdrawn from the market in 1997) and possible cardiac valvulopathy. (Fenfluramine is an amphetamine derivative that nonselectively stimulates serotonin release and inhibits reuptake.)

Lorcaserin comes in a 10-mg twice-daily dosage. In studies, patients taking lorcaserin had an average weight loss of 3.3% more than those taking placebo at one year; weight loss was maintained through the second year for those who continued on medication. However, those who stopped the medication at one year had regained their weight by the two-year mark.4

It is recommended that the medication be discontinued if patients don’t achieve a loss of more than 5% of body weight by 12 weeks.

In a study that enrolled diabetic patients, lorcaserin also demonstrated a 0.9% reduction in A1C, which is similar to or even better than some oral antidiabetic medications.4 However, since the manufacturer was not planning for an antidiabetic indication, A1C was only a secondary endpoint. The reduction is most likely due to decreased caloric intake and weight loss.

The most common adverse effects of lorcaserin include headache, dizziness, and fatigue. The discontinuation rate due to intolerance was 8.6%, compared to 6.7% with placebo.5

Although this was not observed in clinical studies, co-administration of lorcaserin (a serotonin receptor agonist) with other serotonergic or antidopaminergic agents can theoretically cause serotonin syndrome or neuroleptic malignant syndrome–like reactions. Caution is therefore advisable when prescribing these agents. The package insert carries a warning for cardiac valvulopathy due to fen/phen’s history and a lack of long-term cardiovascular safety data.

CASE POINT Deb is taking paroxetine (an SSRI) for her depression. Since you are concerned about serotonin syndrome, you decide to keep exploring options. Checking the package insert for phentermine/topiramate, you learn that it does not have a potential adverse reaction related to co-administration with SSRIs.

Phentermine/Topiramate

Phentermine, a sympathomimetic medication, was approved for short-term (12-week) use for weight loss in the 1960s. Topiramate, an antiseizure and migraine prophylactic medication, enhances appetite suppression—although the exact mechanism of action is unknown.1

Four once-daily doses are available: 3.75/23 mg, 7.5/46 mg, 11.25/69 mg, and 15/92 mg. Dosing starts with 3.75/23 mg for two weeks, then increases to 7.5/46 mg. If a loss of 5% or more of body weight is achieved, the patient can continue the dosage; if not, it can be increased to 11.25/69 mg for two weeks and then to 15/92 mg. The average weight loss for mid and maximum dose was 6.6% and 8.6% greater than placebo at one year.5

Commonly reported adverse effects include paraesthesia, dysgeusia (distortion of sense of taste), dizziness, insomnia, constipation, and dry mouth. Due to phentermine’s sympathomimetic action, mild increases in heart rate and blood pressure were reported. The Endocrine Society recommends against the use of phentermine in patients with uncontrolled hypertension and a history of heart disease.1

Weight loss is generally not recommended during pregnancy, and all weight loss medications are classified as category X for pregnancy. Strict caution is advised with this particular agent, as topiramate has known teratogenicity and therefore comes with a Risk Evaluation Mitigation Strategy. Patients must be advised to use appropriate contraception while taking topiramate, and a pregnancy test should be performed before medication commencement and monthly thereafter.

Abrupt cessation of topiramate can cause seizure. When taking the 15/92-mg dosage, the patient should reduce to one tablet every other day for at least one week before discontinuation.

CASE POINT Deb’s blood pressure is still not at goal. This, along with her history of atrial fibrillation and high pulse, prompts you to consider another option.

Bupropion/Naltrexone

Bupropion, a widely used antidepressant, inhibits the uptake of norepinephrine and dopamine and thereby blocks the reward pathway that various foods can induce. Naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, blocks the opioid pathway and can be helpful in enhancing weight loss.

This combination comes in an 8/90-mg tablet. The suggested titration regimen is to start with one tablet per day and increase by one tablet every week, up to the maximum dosage of two tablets twice a day. Average weight loss was 3.1% greater than placebo at one year with the maximum dosage. An A1C reduction of 0.6% was seen in diabetic patients.6 It is recommended to stop the medication and seek an alternative treatment option if > 5% loss of body weight is not achieved by 12 weeks.

GI adverse effects (eg, nausea and vomiting) are common; these can be reduced with a slower titration regimen or by prescribing a maximum of one tablet twice daily (instead of two). Every antidepressant carries suicidal risk, and caution is advised with their use. Bupropion can also lower the seizure threshold, and it is contraindicated for patients with seizure disorder. It is also contraindicated in patients who are undergoing abrupt cessation of alcohol, benzodiazepines, or barbiturates. It can increase pulse and blood pressure during early titration; regular blood pressure monitoring is warranted.

CASE POINT Due to Deb’s opioid usage and uncontrolled hypertension, you discuss a final option that was recently approved for weight loss.

Liraglutide

This glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP1) receptor agonist affects the brain to suppress/control appetite, slows down gastric emptying, and induces early satiety. A 3-mg dosage was approved in December 2014, but 0.6-, 1.2-, and 1.8-mg dosages have been available since 2010 for patients with type 2 diabetes.

Average weight loss was 4.5% greater than placebo at one year.7 If < 4% weight loss is achieved by 16 weeks, consider using an alternative agent.

The most common adverse effect is GI upset, which could be related to the mechanism of action (slower gastric emptying). Although self-reported GI upset was high (39%), the actual discontinuation rate was low (2.9% for nausea, 1.7% for vomiting, and 1.4% for diarrhea).3

This adverse effect could, in certain contexts, be considered “wanted,” since it discourages overeating or eating too quickly. My clinical pearl is to tell patients taking liraglutide that they are “trapped” and have to eat smaller portions and eat more slowly or they will be more prone to GI effects. With this strategy, we can encourage portion control and responsibility for behavior. (Please note that this is my experience with the diabetic dosage of liraglutide; I do not have any clinical experience with the obesity dosage, which was not clinically available at the time of writing.)

Both branded versions of liraglutide carry a black-box warning for thyroid C-cell tumors, which were observed in rodents but unproven in humans. The medication is contraindicated in patients with medullary thyroid cancer or with multiple endocrine neoplasia 2 syndrome. Increased rates of acute pancreatitis, cholecystitis, and cholelithiasis were seen in studies, and caution is advised.

Continue for A Word About Meds That Cause Weight Gain >>

A WORD ABOUT MEDS THAT CAUSE WEIGHT GAIN

The Endocrine Society has published a list of medications that can influence weight gain, along with suggestions for alternative agents that are either weight neutral or promote weight loss.

Note that our case patient, Deb, is taking insulin, a sulfonylurea (glyburide), and thiazolidinedione (pioglitazone) for diabetes—all of which can promote weight gain. Guidelines suggest choosing metformin, DPP4 inhibitors, GLP1 agonists, amylin analog, and SGLT2 inhibitors instead when weight gain is a major concern.1

Guidelines also suggest using ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers instead of β-blockers as firstline antihypertensive therapy for diabetic patients.1 Adequate blood pressure and lipid control are imperative in diabetes management.

CASE POINT Deb would need better hypertension control before she considers weight-loss medication. Since she is also taking paroxetine, which among SSRIs is associated with greatest weight gain, a changed to fluoxetine or sertraline should be considered.2

Next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

There are now five medications approved by the FDA for chronic weight loss, with more to come. Agents with different mechanisms of action give us options to help obese patients and hopefully reduce and prevent obesity-related complications. It is important for clinicians to be competent in managing obesity, especially since we live in an era in which the disease is considered pandemic.

REFERENCES

1. Apovian CM, Aronne LJ, Bessesen DH, et al; Endocrine Society. Pharmacological management of obesity: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(2):342-362.

2. Xenical [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech USA, Inc; 2012.

3. Fujioka K. Safety and tolerability of medications approved for chronic weight management. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;22 (suppl 1):S7-S11.

4. Belviq [package insert]. Woodcliff Lake, NJ: Eisai Inc; 2015.

5. Qsymia [package insert]. Mountain View, CA: Vivus, Inc; 2013.

6. Contrave [package insert]. Deerfield, IL: Takeda USA, Inc; 2014.

7. Saxenda [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk; 2014.

In June 2013, the American Medical Association classified obesity as a disease. Since then, several medical societies have published guidelines to help clinicians improve care of affected patients. One avenue is, of course, pharmacologic treatment.

Until recently, there was only one FDA-approved medication for chronic weight loss on the market: orlistat, which was approved in 1999. (Phentermine and diethylpropion are only indicated for short-term use). After a long hiatus, the FDA approved two additional agents (phentermine/topiramate and lorcaserin)in 2012 and another two (liraglutide and bupropion/naltrexone) in 2014.

While clinicians appreciate having options for managing their patients’ conditions, in this case, many are overwhelmed by the choices. Most health care providers have not received formal training in obesity management. This column will attempt to fill the information gap in terms of what agents are available and what factors should be assessed before prescribing any of them.

Proviso: Experts claim obesity is a chronic disease, similar to hypertension, and should be managed as such. Although not discussed here, the most important aspect of weight loss and maintenance is lifestyle intervention (diet, exercise, and behavioral modification). It should be emphasized that no medication works by itself; all should be used as an adjunct tool to reinforce adherence to lifestyle changes.1 Furthermore, patients may be disappointed to learn that without these changes, the weight may return when they cease medication use.

CASE Deb, age 61, presents to your office for routine follow-up. She has a history of type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, depression, and chronic back pain due to a herniated disc. Her medications include insulin glargine, glyburide, pioglitazone, atorvastatin, metoprolol, paroxetine, and acetaminophen/hydrocodone.

Her vital signs include a blood pressure of 143/91 mm Hg and a pulse of 93 beats/min. She has a BMI of 37 and a waist circumference of 35 in.

Deb, concerned about her weight, would like to discuss weight-loss options. She has tried three different commercial programs; each time, she was able to lose 30 to 50 lb in three to six months but regained the weight once she stopped the program. She reports excessive appetite as the main reason for her rebound weight gain. Her exercise is limited due to her back pain.

She recently tried OTC orlistat but could not tolerate it due to flatulence and fecal urgency. She reports an incident in which she couldn’t reach the bathroom in time.

Continue for Discussion >>

DISCUSSION

The Endocrine Society’s recommended approaches to obesity management include diet, exercise, and behavioral modification for patients with a BMI ≥ 25. The addition of pharmacotherapy can be considered for those with a BMI ≥ 30 or with a BMI ≥ 27 and one or more weight-related comorbidities (eg, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension). This matches the FDA-approved product labeling for chronic weight-loss medications. Bariatric surgery should be considered for patients with a BMI ≥ 40 or with a BMI ≥ 35 and at least one weight-related comorbidity.

Orlistat