User login

2023 Update on menopause

This year’s menopause Update highlights a highly effective nonhormonal medication that recently received approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of bothersome menopausal vasomotor symptoms. In addition, the Update provides guidance regarding how ObGyns should respond when an endometrial biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding reveals proliferative changes.

Breakthrough in women’s health: A new nonhormone therapy for vasomotor symptoms

Johnson KA, Martin N, Nappi RE, et al. Efficacy and safety of fezolinetant in moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a phase 3 RCT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;dgad058. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad058.

Lederman S, Ottery FD, Cano A, et al. Fezolinetant for treatment of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause (SKYLIGHT 1): a phase 3 randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2023;401:1091-1102. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00085-5.

A new oral nonestrogen-containing medication for relief of moderate to severe hot flashes, fezolinetant (Veozah) 45 mg daily, has been approved by the FDA and was expected to be available by the end of May 2023. Fezolinetant is a selective neurokinin 3 (NK3) receptor antagonistthat offers a targeted nonhormonal approach to menopausal vasomotor symptoms (VMS), and it is the first in its class to make it to market.

The decline in estrogen at menopause appears to result in increased signaling at kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) neurons in the thermoregulatory center within the hypothalamus with resultant increases in hot flashes.1,2 Fezolinetant works by binding to and blocking the activities of the NK3 receptor.3-5

Key study findings

Selective NK3 receptor antagonists, including fezolinetant, effectively reduce the frequency and severity of VMS comparable to that of hormone therapy (HT). Two phase 3 clinical trials, Skylight 1 and 2, confirmed the efficacy and safety of fezolinetant 45 mg in treating VMS,6,7 and an additional 52-week placebo-controlled study, Skylight 4, confirmed long-term safety.8 Onset of action occurs within a week. Reported adverse events occurred in 1% to 2% of healthy menopausal women participating in clinical trials; these included headaches, abdominal pain, diarrhea, insomnia, back pain, hot flushes, and reversible elevated hepatic transaminase levels.6-9

The published phase 2 trials9 and the international randomized controlled trial (RCT) 12-week studies, Skylight 1 and 2,6,7 found that once-daily 30-mg and 45-mg doses of fezolinetant significantly reduced VMS frequency and severity at 12 weeks among women aged 40 to 60 years who reported an average of 7 moderate to severe VMS/day; the reduction in reported VMS was sustained at 40 weeks. Phase 3 data from Skylight 1 and 2 demonstrated fezolinetant’s efficacy in reducing the frequency and severity of VMS and provided information on the safety profile of fezolinetant compared with placebo over 12 weeks and a noncontrolled extension for an additional 40 weeks.6,7

Oral fezolinetant was associated with improved quality of life, including reduced VMS-related interference with daily life.10 Johnson and colleagues, reporting for Skylight 2, found VMS frequency and severity improvement by week 1, which achieved statistical significance at weeks 4 and 12, with this improvement maintained through week 52.6 A 64.3% reduction in mean daily VMS from baseline was seen at 12 weeks for fezolinetant 45 mg compared with a 45.4% reduction for placebo. VMS severity significantly decreased compared with placebo at 4 and 12 weeks.6

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were infrequent, reported by 2%, 1%, and 0% of those receiving fezolinetant 30 mg, fezolinetant 45 mg, and placebo.6 Increases in levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were noted and were described as asymptomatic, isolated, intermittent, or transient, and these levels returned to baseline during treatment or after discontinuation.6

Of the 5 participants taking fezolinetant in Skyline 1 with ALT or AST levels greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal in the 12-week randomized trial, levels returned to normal range while continuing treatment in 2 participants, with treatment interruption in 2, and with discontinuation in 1. No new safety signals were seen in the 40-week extension trial.6

Fezolinetant offers a much-needed effective and safe selective nonhormone NK3 receptor antagonist therapy that reduces the frequency and severity of menopausal VMS and has been shown to be safe through 52 weeks of treatment.

To read more about how fezolinetant specifically targets the hormone receptor that triggers hot flashes as well as on prescribing hormone therapy for women with menopausal symptoms, see “Focus on menopause: Q&A with Jan Shifren, MD, and Genevieve NealPerry, MD, PhD,” in the December 2022 issue of OBG Management at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/article/260380/menopause

Continue to: Endometrial and bone safety...

Endometrial and bone safety

Results from Skylight 4, a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, 52-week safety study, provided additional evidence that confirmed the longer-term safety of fezolinetant over a 52-week treatment period.8

Endometrial safety was assessed in postmenopausal women with normal baseline endometrium (n = 599).8 For fezolinetant 45 mg, 1 of 203 participants had endometrial hyperplasia (EH) (0.5%; upper limit of one-sided 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.3%); no cases of EH were noted in the placebo (0 of 186) or fezolinetant 30-mg (0 of 210) groups. The incidence of EH or malignancy in fezolinetant-treated participants was within prespecified limits, as assessed by blinded, centrally read endometrial biopsies. Endometrial malignancy occurred in 1 of 210 in the fezolinetant 30-mg group (0.5%; 95% CI, 2.2%) with no cases in the other groups, thus meeting FDA requirements for endometrial safety.8

In addition, no significant differences were noted in change from baseline endometrial thickness on transvaginal ultrasonography between fezolinetant-treated and placebo groups. Likewise, no loss of bone density was found on dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans or trabecular bone scores.8

Liver safety

Although no cases of severe liver injury were noted, elevations in serum transaminase concentrations greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal were observed in the clinical trials. In Skylight 4, liver enzyme elevations more than 3 times the upper limit of normal occurred in 6 of 583 participants taking placebo, 8 of 590 taking fezolinetant 30 mg, and 12 of 589 taking fezolinetant 45 mg.8

The prescribing information for fezolinetant includes a warning for elevated hepatic transaminases: Fezolinetant should not be started if baseline serum transaminase concentration is equal to or exceeds 2 times the upper limit of normal. Liver tests should be obtained at baseline and repeated every 3 months for the first 9 months and then if symptoms suggest liver injury.11,12

Unmet need for nonhormone treatment of VMS

Vasomotor symptoms affect up to 80% of women, with approximately 25% bothersome enough to warrant treatment. Vasomotor symptoms persist for a median of 7 years, with duration and severity differing by race and ethnicity. Black, Hispanic, and possibly Native American women experience the highest burden of VMS.2 Although VMS, including hot flashes, night sweats, and mood and sleep disturbances, often are considered an annoyance to those with mild symptoms, moderate to severe VMS impact women’s lives, including functioning at home or work, affecting relationships, and decreasing perceived quality of life, and they have been associated with workplace absenteeism and increased health care costs, both direct from medical care and testing and indirect costs from lost work.13-15

Women with 7 or more daily moderate to severe VMS (defined as with sweating or affecting function) reported interference with sleep (94%), concentration (84%), mood (85%), energy (77%), and sexual activity (61%).16 Moderately to severely bothersome VMS have been associated with impaired psychological and general well-being, affecting work performance.17 Based on a Mayo Clinic workplace survey, Faubion and colleagues estimated an annual loss of $1.8 billion in the United States for menopause-related missed work and a $28 billion loss when medical expenses were added.15

Menopausal HT has been the primary treatment for VMS and has been shown to reduce the frequency and severity of hot flashes, with additional benefits on sleep, mood, fatigue, bone loss and reduction of fracture, and genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), and with potential improvement in cardiovascular health with decreased type 2 diabetes.18,19 For healthy women with early menopause and no contraindications, HT has been recommended until at least the age of natural menopause, as observational data suggest that HT prevents osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative changes, and sexual dysfunction for these women.19,20 Similarly, for healthy women younger than age 60 or within 10 years of menopause, initiating HT has been shown to be safe and effective in treating bothersome VMS and preventing osteoporotic fractures and genitourinary changes.19,21

Most systemic HT formulations are inexpensive (for example, available as generics), with multiple dosing and formulations available for use alone or combined as oral, transdermal, or vaginal therapies. Despite the fear that arose for clinicians and women from the initial 2002 findings of the Women’s Health Initiative regarding increased risk of breast cancer, stroke, venous thrombosis, cardiovascular disease, and dementia, major medical societies agree that when initiated at or soon after menopause, HT is a safe and effective therapy to relieve VMS, protect against bone loss, and treat genitourinary changes.19,21

Many women, however, cannot take HT, including those with estrogen-sensitive cancers, such as breast or uterine cancers; prior cardiovascular disease, stroke, or venous thrombotic events; severe endometriosis; or migraine headaches with visual auras.2 In addition, many symptomatic menopausal women without health contraindications choose not to take HT.2 Until now, the only FDA-approved VMS nonhormone therapy has been a low-dose 7.5-mg paroxetine salt. Unfortunately, this formulation, along with the off-label use of other antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), gabapentinoids, oxybutynin, and clonidine, are substantially less effective than HT in treating moderate to severe VMS.

Bottom line

A substantial unmet need remains for effective therapy for moderate to severe VMS for women who cannot or choose not to take menopausal HT to relieve VMS.2,16 Effective, safe nonhormone treatment options such as the new NK3 receptor antagonist fezolinetant will address this clinically important need.

One concern is that the cost of developing and bringing to market the first of a new type of medication will be passed on to consumers, which may put it out of the price range for the many women who need it. However, the development and FDA approval of fezolinetant as the first NK3 receptor antagonist to treat menopausal VMS is potentially a practice changer. It provides a novel, effective, and safe FDA-approved nonhormonal treatment for menopausal women with moderate to severe VMS, particularly for women who cannot or will not take hormone therapy.

Continue to: When endometrial biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding reveals proliferative changes, how should we respond?...

When endometrial biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding reveals proliferative changes, how should we respond?

Abraham C. Proliferative endometrium in menopause: to treat or not to treat? Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:265-267. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005054.

The following case represents a common scenario for ObGyns.

CASE Patient with proliferative endometrial changes

A menopausal patient with a body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2 presents with uterine bleeding. She does not use systemic menopausal hormone therapy. Endometrial biopsy indicates proliferative changes.

When endometrial biopsy performed for bleeding reveals proliferative changes in menopausal women, we traditionally have responded by reassuring the patient that the findings are benign and advising that she should let us know if future spotting or bleeding occurs.

However, a recent review by Abraham published in Obstetrics and Gynecology details the implications of proliferative endometrial changes in menopausal patients, advising that treatment, as well as monitoring, may be appropriate.22

Endometrial changes and what they suggest

In premenopausal women, proliferative endometrial changes are physiologic and result from ovarian estrogen production early in each cycle, during what is called the proliferative (referring to the endometrium) or follicular (referring to the dominant follicle that synthesizes estrogen) phase. In menopausal women who are not using HT, however, proliferative endometrial changes, with orderly uniform glands seen on histologic evaluation, reflect aromatization of androgens by adipose and other tissues into estrogen.

The next step on the continuum to hyperplasia (benign or atypical) after proliferative endometrium is disordered proliferative endometrium. At this stage, histologic evaluation reveals scattered cystic and dilated glands that have a normal gland-to-stroma ratio with a low gland density overall and without any atypia. Randomly distributed glands may have tubal metaplasia or fibrin thrombi associated with microinfarcts, often presenting with irregular bleeding. This is a noncancerous change that occurs with excess estrogen (endogenous or exogenous).23

Progestins reverse endometrial hyperplasia by activating progesterone receptors, which leads to stromal decidualization with thinning of the endometrium. They have a pronounced effect on the histologic appearance of the endometrium. By contrast, endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN, previously known as endometrial hyperplasiawith atypia) shows underlying molecular mutations and histologic alterations and represents a sharp transition to true neoplasia, which greatly increases the risk of endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma.24

For decades, we have been aware that if women diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia are not treated with progestational therapy, their future risk of endometrial cancer is elevated. More recently, we also recognize that menopausal women found to have proliferative endometrial changes, if not treated, have an increased risk of endometrial cancer.

In a retrospective cohort study of almost 300 menopausal women who were not treated after endometrial biopsy revealed proliferative changes, investigators followed participants for an average of 11 years.25 These women had a mean BMI of 34 kg/m2. During follow-up, almost 12% of these women were diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia or cancer. This incidence of endometrial neoplasia was some 4 times higher than for women initially found to have atrophic endometrial changes.25

Progestin treatment

Oral progestin therapy with follow-up endometrial biopsy constitutes traditional management for endometrial hyperplasia. Such therapy minimizes the likelihood that hyperplasia will progress to endometrial cancer.

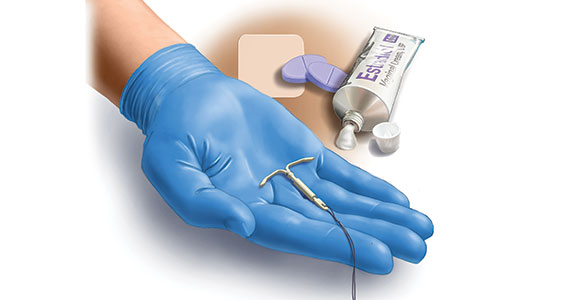

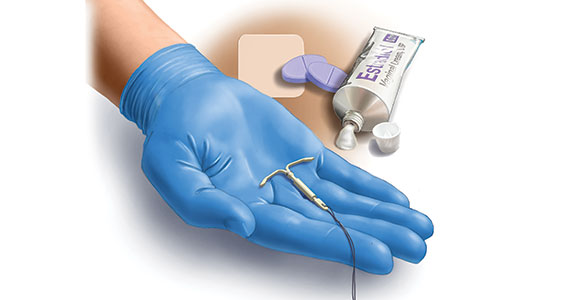

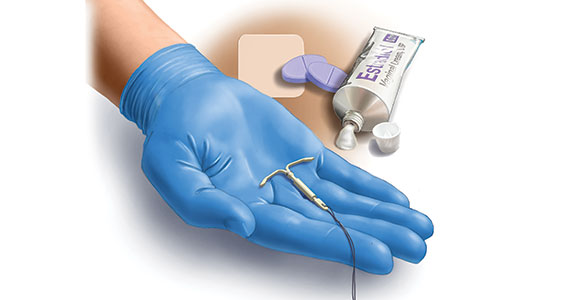

We now recognize that the convenience, as well as the high endometrial progestin levels achieved, with levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs) have advantages over oral progestin therapy in treating endometrial hyperplasia. Indeed, a recent US report found that among women with EIN managed medically, use of progestin-releasing IUDs has grown from 7.7% in 2008 to 35.6% in 2020.26

Although both oral and intrauterine progestin are highly effective in treating simple hyperplasia, progestin IUDs are substantially more effective than oral progestins in treating EIN.27 Progestin concentrations in the endometrium have been shown to be 100-fold higher after LNG-IUD placement compared with oral progestin use.22 In addition, adverse effects, including bloating, unpleasant mood changes, and increased appetite, are more common with oral than intrauterine progestin therapy.28

Unfortunately, data from randomized trials addressing progestational treatment of proliferative endometrium in menopausal women are not available to support the treatment of proliferative endometrium with either oral progestins or the LNG-IUD.22

Role of ultrasonography

Another concern is relying on a finding of thin endometrial thickness on vaginal ultrasonography. In a simulated retrospective cohort study, use of transvaginal ultrasonography to determine the appropriateness of a biopsy was found not to be sufficiently accurate or racially equitable with regard to Black women.29 In simulated data, transvaginal ultrasonography missed almost 5 times more cases of endometrial cancer among Black women compared with White women due to higher fibroid prevalence and nonendometrioid histologic type malignancies in Black women.29

Assessing risk

If proliferative endometrium is found, Abraham suggests assessing risk using22:

- age

- comorbidities (including obesity)

- endometrial echo thickness on vaginal ultrasonography.

Consider the patient’s risk and tolerance of recurrent bleeding as well as her tolerance for progestational adverse effects if medical therapy is chosen. Discussion about next steps should include reviewing the histologic findings with the patient and discussing the difference in risk of progression to endometrial cancer of a finding of proliferative endometrium compared with a histologic finding of endometrial hyperplasia.

Using this patient-centered approach, observation over time with follow-up endometrial biopsies remains a management option. Although some women may tolerate micronized progesterone over synthetic progestins, there is concern that it may be less effective in suppressing the endometrium than synthetic progestins.30 Accordingly, synthetic progestins represent first-line options in this setting.

In her review, Abraham suggests that when endometrial biopsy reveals proliferative changes in a menopausal woman, we should initiate progestin treatment and perform surveillance endometrial sampling every 3 to 6 months. If such sampling reveals benign but not proliferative endometrium, progestin therapy can be stopped and endometrial biopsy repeated if bleeding recurs.22 ●

ObGyns may choose to adopt Abraham’s approach or to hold off on progestin therapy while performing follow-up endometrial sampling. Either way, the take-home message is that the finding of proliferative endometrial changes on biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding requires proactive management.

- Modi M, Dhillo WS. Neurokinin 3 receptor antagonism: a novel treatment for menopausal hot flushes. Neuroendocrinology. 2019;109:242-248. doi:10.1159/000495889

- Pinkerton JV, Redick DL, Homewood LN, et al. Neurokinin receptor antagonist, fezolinetant, for treatment of menopausal vasomotor symptoms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;dgad209. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad209

- Rance NE, Dacks PA, Mittelman-Smith MA, et al. Modulation of body temperature and LH secretion by hypothalamic KNDy (kisspeptin, neurokinin B and dynorphin) neurons: a novel hypothesis on the mechanism of hot flushes. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2013;34:211-227. doi:10.1016 /j.yfrne.2013.07.003

- Mittelman-Smith MA, Williams H, Krajewski-Hall SJ, et al. Role for kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) neurons in cutaneous vasodilatation and the estrogen modulation of body temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:1984619851. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211517109

- Astellas Pharma. Astellas’ Veozah (fezolinetant) approved by US FDA for treatment of vasomotor symptoms due to menopause. May 12, 2023. PR Newswire. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/astellas-veozah-fezolinetant-approved-by-us-fda-for -treatment-of-vasomotor-symptoms-due-to-menopause -301823639.html

- Johnson KA, Martin N, Nappi RE, et al. Efficacy and safety of fezolinetant in moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a phase 3 RCT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;dgad058. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad058

- Lederman S, Ottery FD, Cano A, et al. Fezolinetant for treatment of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause (SKYLIGHT 1): a phase 3 randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2023;401:1091-1102. doi:10.1016 /S0140-6736(23)00085-5

- Neal-Perry G, Cano A, Lederman S, et al. Safety of fezolinetant for vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:737-747. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005114

- Depypere H, Timmerman D, Donders G, et al. Treatment of menopausal vasomotor symptoms with fezolinetant, a neurokinin 3 receptor antagonist: a phase 2a trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:5893-5905. doi: 10.1210/jc .2019-00677

- Santoro N, Waldbaum A, Lederman S, et al. Effect of the neurokinin 3 receptor antagonist fezolinetant on patientreported outcomes in postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, dose-ranging study (VESTA). Menopause. 2020;27:1350-1356. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001621

- FDA approves novel drug to treat moderate to severe hot flashes caused by menopause. May 12, 2023. US Food and Drug Administration. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www .fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves -novel-drug-treat-moderate-severe-hot-flashes-caused -menopause

- Veozah. Prescribing information. Astellas; 2023. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://www.astellas.com/us/system/files /veozah_uspi.pdf

- Pinkerton JV. Money talks: untreated hot flashes cost women, the workplace, and society. Menopause. 2015;22:254-255. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000427

- Sarrel P, Portman D, Lefebvre P, et al. Incremental direct and indirect costs of untreated vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. 2015;22(3):260-266. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000320

- Faubion SS, Enders F, Hedges MS, et al. Impact of menopause symptoms on women in the workplace. Mayo Clin Proc. 2023;98:833-845. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.02.025

- Williams RE, Levine KB, Kalilani L, et al. Menopause- specific questionnaire assessment in US populationbased study shows negative impact on health-related quality of life. Maturitas. 2009;62:153-159. doi:10.1016 /j.maturitas.2008.12.006

- Gartoulla P, Bell RJ, Worsley R, et al. Moderate-severely bothersome vasomotor symptoms are associated with lowered psychological general wellbeing in women at midlife. Maturitas. 2015;81:487-492. doi:10.1016 /j.maturitas.2015.06.004

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management—getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:803-806. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1514242

- 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of the North American Menopause Society Advisory Panel. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2022;29:767-794. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000002028

- Kaunitz AM, Kapoor E, Faubion S. Treatment of women after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed prior to natural menopause. JAMA. 2021;12;326:1429-1430. doi:10.1001 /jama.2021.3305

- Pinkerton JV. Hormone therapy for postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:446-455. doi:10.1056 /NEJMcp1714787

- Abraham C. Proliferative endometrium in menopause: to treat or not to treat? Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:265-267. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005054

- Chandra V, Kim JJ, Benbrook DM, et al. Therapeutic options for management of endometrial hyperplasia. J Gynecol Oncol. 2016;27:e8. doi:10.3802/jgo.2016.27.e8

- Owings RA, Quick CM. Endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:484-491. doi:10.5858 /arpa.2012-0709-RA

- Rotenberg O, Doulaveris G, Fridman D, et al. Long-term outcome of postmenopausal women with proliferative endometrium on endometrial sampling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:896.e1-896.e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.045

- Suzuki Y, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Systemic progestins and progestin-releasing intrauterine device therapy for premenopausal patients with endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:979-987. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005124

- Mandelbaum RS, Ciccone MA, Nusbaum DJ, et al. Progestin therapy for obese women with complex atypical hyperplasia: levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device vs systemic therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:103.e1-103.e13. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.12.273

- Liu S, Kciuk O, Frank M, et al. Progestins of today and tomorrow. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2022;34:344-350. doi:10.1097 /GCO.0000000000000819

- Doll KM, Romano SS, Marsh EE, et al. Estimated performance of transvaginal ultrasonography for evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding in a simulated cohort of black and white women in the US. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1158-1165. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1700

- Gompel A. Progesterone and endometrial cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;69:95-107. doi:10.1016 /j.bpobgyn.2020.05.003

This year’s menopause Update highlights a highly effective nonhormonal medication that recently received approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of bothersome menopausal vasomotor symptoms. In addition, the Update provides guidance regarding how ObGyns should respond when an endometrial biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding reveals proliferative changes.

Breakthrough in women’s health: A new nonhormone therapy for vasomotor symptoms

Johnson KA, Martin N, Nappi RE, et al. Efficacy and safety of fezolinetant in moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a phase 3 RCT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;dgad058. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad058.

Lederman S, Ottery FD, Cano A, et al. Fezolinetant for treatment of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause (SKYLIGHT 1): a phase 3 randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2023;401:1091-1102. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00085-5.

A new oral nonestrogen-containing medication for relief of moderate to severe hot flashes, fezolinetant (Veozah) 45 mg daily, has been approved by the FDA and was expected to be available by the end of May 2023. Fezolinetant is a selective neurokinin 3 (NK3) receptor antagonistthat offers a targeted nonhormonal approach to menopausal vasomotor symptoms (VMS), and it is the first in its class to make it to market.

The decline in estrogen at menopause appears to result in increased signaling at kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) neurons in the thermoregulatory center within the hypothalamus with resultant increases in hot flashes.1,2 Fezolinetant works by binding to and blocking the activities of the NK3 receptor.3-5

Key study findings

Selective NK3 receptor antagonists, including fezolinetant, effectively reduce the frequency and severity of VMS comparable to that of hormone therapy (HT). Two phase 3 clinical trials, Skylight 1 and 2, confirmed the efficacy and safety of fezolinetant 45 mg in treating VMS,6,7 and an additional 52-week placebo-controlled study, Skylight 4, confirmed long-term safety.8 Onset of action occurs within a week. Reported adverse events occurred in 1% to 2% of healthy menopausal women participating in clinical trials; these included headaches, abdominal pain, diarrhea, insomnia, back pain, hot flushes, and reversible elevated hepatic transaminase levels.6-9

The published phase 2 trials9 and the international randomized controlled trial (RCT) 12-week studies, Skylight 1 and 2,6,7 found that once-daily 30-mg and 45-mg doses of fezolinetant significantly reduced VMS frequency and severity at 12 weeks among women aged 40 to 60 years who reported an average of 7 moderate to severe VMS/day; the reduction in reported VMS was sustained at 40 weeks. Phase 3 data from Skylight 1 and 2 demonstrated fezolinetant’s efficacy in reducing the frequency and severity of VMS and provided information on the safety profile of fezolinetant compared with placebo over 12 weeks and a noncontrolled extension for an additional 40 weeks.6,7

Oral fezolinetant was associated with improved quality of life, including reduced VMS-related interference with daily life.10 Johnson and colleagues, reporting for Skylight 2, found VMS frequency and severity improvement by week 1, which achieved statistical significance at weeks 4 and 12, with this improvement maintained through week 52.6 A 64.3% reduction in mean daily VMS from baseline was seen at 12 weeks for fezolinetant 45 mg compared with a 45.4% reduction for placebo. VMS severity significantly decreased compared with placebo at 4 and 12 weeks.6

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were infrequent, reported by 2%, 1%, and 0% of those receiving fezolinetant 30 mg, fezolinetant 45 mg, and placebo.6 Increases in levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were noted and were described as asymptomatic, isolated, intermittent, or transient, and these levels returned to baseline during treatment or after discontinuation.6

Of the 5 participants taking fezolinetant in Skyline 1 with ALT or AST levels greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal in the 12-week randomized trial, levels returned to normal range while continuing treatment in 2 participants, with treatment interruption in 2, and with discontinuation in 1. No new safety signals were seen in the 40-week extension trial.6

Fezolinetant offers a much-needed effective and safe selective nonhormone NK3 receptor antagonist therapy that reduces the frequency and severity of menopausal VMS and has been shown to be safe through 52 weeks of treatment.

To read more about how fezolinetant specifically targets the hormone receptor that triggers hot flashes as well as on prescribing hormone therapy for women with menopausal symptoms, see “Focus on menopause: Q&A with Jan Shifren, MD, and Genevieve NealPerry, MD, PhD,” in the December 2022 issue of OBG Management at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/article/260380/menopause

Continue to: Endometrial and bone safety...

Endometrial and bone safety

Results from Skylight 4, a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, 52-week safety study, provided additional evidence that confirmed the longer-term safety of fezolinetant over a 52-week treatment period.8

Endometrial safety was assessed in postmenopausal women with normal baseline endometrium (n = 599).8 For fezolinetant 45 mg, 1 of 203 participants had endometrial hyperplasia (EH) (0.5%; upper limit of one-sided 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.3%); no cases of EH were noted in the placebo (0 of 186) or fezolinetant 30-mg (0 of 210) groups. The incidence of EH or malignancy in fezolinetant-treated participants was within prespecified limits, as assessed by blinded, centrally read endometrial biopsies. Endometrial malignancy occurred in 1 of 210 in the fezolinetant 30-mg group (0.5%; 95% CI, 2.2%) with no cases in the other groups, thus meeting FDA requirements for endometrial safety.8

In addition, no significant differences were noted in change from baseline endometrial thickness on transvaginal ultrasonography between fezolinetant-treated and placebo groups. Likewise, no loss of bone density was found on dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans or trabecular bone scores.8

Liver safety

Although no cases of severe liver injury were noted, elevations in serum transaminase concentrations greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal were observed in the clinical trials. In Skylight 4, liver enzyme elevations more than 3 times the upper limit of normal occurred in 6 of 583 participants taking placebo, 8 of 590 taking fezolinetant 30 mg, and 12 of 589 taking fezolinetant 45 mg.8

The prescribing information for fezolinetant includes a warning for elevated hepatic transaminases: Fezolinetant should not be started if baseline serum transaminase concentration is equal to or exceeds 2 times the upper limit of normal. Liver tests should be obtained at baseline and repeated every 3 months for the first 9 months and then if symptoms suggest liver injury.11,12

Unmet need for nonhormone treatment of VMS

Vasomotor symptoms affect up to 80% of women, with approximately 25% bothersome enough to warrant treatment. Vasomotor symptoms persist for a median of 7 years, with duration and severity differing by race and ethnicity. Black, Hispanic, and possibly Native American women experience the highest burden of VMS.2 Although VMS, including hot flashes, night sweats, and mood and sleep disturbances, often are considered an annoyance to those with mild symptoms, moderate to severe VMS impact women’s lives, including functioning at home or work, affecting relationships, and decreasing perceived quality of life, and they have been associated with workplace absenteeism and increased health care costs, both direct from medical care and testing and indirect costs from lost work.13-15

Women with 7 or more daily moderate to severe VMS (defined as with sweating or affecting function) reported interference with sleep (94%), concentration (84%), mood (85%), energy (77%), and sexual activity (61%).16 Moderately to severely bothersome VMS have been associated with impaired psychological and general well-being, affecting work performance.17 Based on a Mayo Clinic workplace survey, Faubion and colleagues estimated an annual loss of $1.8 billion in the United States for menopause-related missed work and a $28 billion loss when medical expenses were added.15

Menopausal HT has been the primary treatment for VMS and has been shown to reduce the frequency and severity of hot flashes, with additional benefits on sleep, mood, fatigue, bone loss and reduction of fracture, and genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), and with potential improvement in cardiovascular health with decreased type 2 diabetes.18,19 For healthy women with early menopause and no contraindications, HT has been recommended until at least the age of natural menopause, as observational data suggest that HT prevents osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative changes, and sexual dysfunction for these women.19,20 Similarly, for healthy women younger than age 60 or within 10 years of menopause, initiating HT has been shown to be safe and effective in treating bothersome VMS and preventing osteoporotic fractures and genitourinary changes.19,21

Most systemic HT formulations are inexpensive (for example, available as generics), with multiple dosing and formulations available for use alone or combined as oral, transdermal, or vaginal therapies. Despite the fear that arose for clinicians and women from the initial 2002 findings of the Women’s Health Initiative regarding increased risk of breast cancer, stroke, venous thrombosis, cardiovascular disease, and dementia, major medical societies agree that when initiated at or soon after menopause, HT is a safe and effective therapy to relieve VMS, protect against bone loss, and treat genitourinary changes.19,21

Many women, however, cannot take HT, including those with estrogen-sensitive cancers, such as breast or uterine cancers; prior cardiovascular disease, stroke, or venous thrombotic events; severe endometriosis; or migraine headaches with visual auras.2 In addition, many symptomatic menopausal women without health contraindications choose not to take HT.2 Until now, the only FDA-approved VMS nonhormone therapy has been a low-dose 7.5-mg paroxetine salt. Unfortunately, this formulation, along with the off-label use of other antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), gabapentinoids, oxybutynin, and clonidine, are substantially less effective than HT in treating moderate to severe VMS.

Bottom line

A substantial unmet need remains for effective therapy for moderate to severe VMS for women who cannot or choose not to take menopausal HT to relieve VMS.2,16 Effective, safe nonhormone treatment options such as the new NK3 receptor antagonist fezolinetant will address this clinically important need.

One concern is that the cost of developing and bringing to market the first of a new type of medication will be passed on to consumers, which may put it out of the price range for the many women who need it. However, the development and FDA approval of fezolinetant as the first NK3 receptor antagonist to treat menopausal VMS is potentially a practice changer. It provides a novel, effective, and safe FDA-approved nonhormonal treatment for menopausal women with moderate to severe VMS, particularly for women who cannot or will not take hormone therapy.

Continue to: When endometrial biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding reveals proliferative changes, how should we respond?...

When endometrial biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding reveals proliferative changes, how should we respond?

Abraham C. Proliferative endometrium in menopause: to treat or not to treat? Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:265-267. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005054.

The following case represents a common scenario for ObGyns.

CASE Patient with proliferative endometrial changes

A menopausal patient with a body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2 presents with uterine bleeding. She does not use systemic menopausal hormone therapy. Endometrial biopsy indicates proliferative changes.

When endometrial biopsy performed for bleeding reveals proliferative changes in menopausal women, we traditionally have responded by reassuring the patient that the findings are benign and advising that she should let us know if future spotting or bleeding occurs.

However, a recent review by Abraham published in Obstetrics and Gynecology details the implications of proliferative endometrial changes in menopausal patients, advising that treatment, as well as monitoring, may be appropriate.22

Endometrial changes and what they suggest

In premenopausal women, proliferative endometrial changes are physiologic and result from ovarian estrogen production early in each cycle, during what is called the proliferative (referring to the endometrium) or follicular (referring to the dominant follicle that synthesizes estrogen) phase. In menopausal women who are not using HT, however, proliferative endometrial changes, with orderly uniform glands seen on histologic evaluation, reflect aromatization of androgens by adipose and other tissues into estrogen.

The next step on the continuum to hyperplasia (benign or atypical) after proliferative endometrium is disordered proliferative endometrium. At this stage, histologic evaluation reveals scattered cystic and dilated glands that have a normal gland-to-stroma ratio with a low gland density overall and without any atypia. Randomly distributed glands may have tubal metaplasia or fibrin thrombi associated with microinfarcts, often presenting with irregular bleeding. This is a noncancerous change that occurs with excess estrogen (endogenous or exogenous).23

Progestins reverse endometrial hyperplasia by activating progesterone receptors, which leads to stromal decidualization with thinning of the endometrium. They have a pronounced effect on the histologic appearance of the endometrium. By contrast, endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN, previously known as endometrial hyperplasiawith atypia) shows underlying molecular mutations and histologic alterations and represents a sharp transition to true neoplasia, which greatly increases the risk of endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma.24

For decades, we have been aware that if women diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia are not treated with progestational therapy, their future risk of endometrial cancer is elevated. More recently, we also recognize that menopausal women found to have proliferative endometrial changes, if not treated, have an increased risk of endometrial cancer.

In a retrospective cohort study of almost 300 menopausal women who were not treated after endometrial biopsy revealed proliferative changes, investigators followed participants for an average of 11 years.25 These women had a mean BMI of 34 kg/m2. During follow-up, almost 12% of these women were diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia or cancer. This incidence of endometrial neoplasia was some 4 times higher than for women initially found to have atrophic endometrial changes.25

Progestin treatment

Oral progestin therapy with follow-up endometrial biopsy constitutes traditional management for endometrial hyperplasia. Such therapy minimizes the likelihood that hyperplasia will progress to endometrial cancer.

We now recognize that the convenience, as well as the high endometrial progestin levels achieved, with levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs) have advantages over oral progestin therapy in treating endometrial hyperplasia. Indeed, a recent US report found that among women with EIN managed medically, use of progestin-releasing IUDs has grown from 7.7% in 2008 to 35.6% in 2020.26

Although both oral and intrauterine progestin are highly effective in treating simple hyperplasia, progestin IUDs are substantially more effective than oral progestins in treating EIN.27 Progestin concentrations in the endometrium have been shown to be 100-fold higher after LNG-IUD placement compared with oral progestin use.22 In addition, adverse effects, including bloating, unpleasant mood changes, and increased appetite, are more common with oral than intrauterine progestin therapy.28

Unfortunately, data from randomized trials addressing progestational treatment of proliferative endometrium in menopausal women are not available to support the treatment of proliferative endometrium with either oral progestins or the LNG-IUD.22

Role of ultrasonography

Another concern is relying on a finding of thin endometrial thickness on vaginal ultrasonography. In a simulated retrospective cohort study, use of transvaginal ultrasonography to determine the appropriateness of a biopsy was found not to be sufficiently accurate or racially equitable with regard to Black women.29 In simulated data, transvaginal ultrasonography missed almost 5 times more cases of endometrial cancer among Black women compared with White women due to higher fibroid prevalence and nonendometrioid histologic type malignancies in Black women.29

Assessing risk

If proliferative endometrium is found, Abraham suggests assessing risk using22:

- age

- comorbidities (including obesity)

- endometrial echo thickness on vaginal ultrasonography.

Consider the patient’s risk and tolerance of recurrent bleeding as well as her tolerance for progestational adverse effects if medical therapy is chosen. Discussion about next steps should include reviewing the histologic findings with the patient and discussing the difference in risk of progression to endometrial cancer of a finding of proliferative endometrium compared with a histologic finding of endometrial hyperplasia.

Using this patient-centered approach, observation over time with follow-up endometrial biopsies remains a management option. Although some women may tolerate micronized progesterone over synthetic progestins, there is concern that it may be less effective in suppressing the endometrium than synthetic progestins.30 Accordingly, synthetic progestins represent first-line options in this setting.

In her review, Abraham suggests that when endometrial biopsy reveals proliferative changes in a menopausal woman, we should initiate progestin treatment and perform surveillance endometrial sampling every 3 to 6 months. If such sampling reveals benign but not proliferative endometrium, progestin therapy can be stopped and endometrial biopsy repeated if bleeding recurs.22 ●

ObGyns may choose to adopt Abraham’s approach or to hold off on progestin therapy while performing follow-up endometrial sampling. Either way, the take-home message is that the finding of proliferative endometrial changes on biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding requires proactive management.

This year’s menopause Update highlights a highly effective nonhormonal medication that recently received approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of bothersome menopausal vasomotor symptoms. In addition, the Update provides guidance regarding how ObGyns should respond when an endometrial biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding reveals proliferative changes.

Breakthrough in women’s health: A new nonhormone therapy for vasomotor symptoms

Johnson KA, Martin N, Nappi RE, et al. Efficacy and safety of fezolinetant in moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a phase 3 RCT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;dgad058. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad058.

Lederman S, Ottery FD, Cano A, et al. Fezolinetant for treatment of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause (SKYLIGHT 1): a phase 3 randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2023;401:1091-1102. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00085-5.

A new oral nonestrogen-containing medication for relief of moderate to severe hot flashes, fezolinetant (Veozah) 45 mg daily, has been approved by the FDA and was expected to be available by the end of May 2023. Fezolinetant is a selective neurokinin 3 (NK3) receptor antagonistthat offers a targeted nonhormonal approach to menopausal vasomotor symptoms (VMS), and it is the first in its class to make it to market.

The decline in estrogen at menopause appears to result in increased signaling at kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) neurons in the thermoregulatory center within the hypothalamus with resultant increases in hot flashes.1,2 Fezolinetant works by binding to and blocking the activities of the NK3 receptor.3-5

Key study findings

Selective NK3 receptor antagonists, including fezolinetant, effectively reduce the frequency and severity of VMS comparable to that of hormone therapy (HT). Two phase 3 clinical trials, Skylight 1 and 2, confirmed the efficacy and safety of fezolinetant 45 mg in treating VMS,6,7 and an additional 52-week placebo-controlled study, Skylight 4, confirmed long-term safety.8 Onset of action occurs within a week. Reported adverse events occurred in 1% to 2% of healthy menopausal women participating in clinical trials; these included headaches, abdominal pain, diarrhea, insomnia, back pain, hot flushes, and reversible elevated hepatic transaminase levels.6-9

The published phase 2 trials9 and the international randomized controlled trial (RCT) 12-week studies, Skylight 1 and 2,6,7 found that once-daily 30-mg and 45-mg doses of fezolinetant significantly reduced VMS frequency and severity at 12 weeks among women aged 40 to 60 years who reported an average of 7 moderate to severe VMS/day; the reduction in reported VMS was sustained at 40 weeks. Phase 3 data from Skylight 1 and 2 demonstrated fezolinetant’s efficacy in reducing the frequency and severity of VMS and provided information on the safety profile of fezolinetant compared with placebo over 12 weeks and a noncontrolled extension for an additional 40 weeks.6,7

Oral fezolinetant was associated with improved quality of life, including reduced VMS-related interference with daily life.10 Johnson and colleagues, reporting for Skylight 2, found VMS frequency and severity improvement by week 1, which achieved statistical significance at weeks 4 and 12, with this improvement maintained through week 52.6 A 64.3% reduction in mean daily VMS from baseline was seen at 12 weeks for fezolinetant 45 mg compared with a 45.4% reduction for placebo. VMS severity significantly decreased compared with placebo at 4 and 12 weeks.6

Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were infrequent, reported by 2%, 1%, and 0% of those receiving fezolinetant 30 mg, fezolinetant 45 mg, and placebo.6 Increases in levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were noted and were described as asymptomatic, isolated, intermittent, or transient, and these levels returned to baseline during treatment or after discontinuation.6

Of the 5 participants taking fezolinetant in Skyline 1 with ALT or AST levels greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal in the 12-week randomized trial, levels returned to normal range while continuing treatment in 2 participants, with treatment interruption in 2, and with discontinuation in 1. No new safety signals were seen in the 40-week extension trial.6

Fezolinetant offers a much-needed effective and safe selective nonhormone NK3 receptor antagonist therapy that reduces the frequency and severity of menopausal VMS and has been shown to be safe through 52 weeks of treatment.

To read more about how fezolinetant specifically targets the hormone receptor that triggers hot flashes as well as on prescribing hormone therapy for women with menopausal symptoms, see “Focus on menopause: Q&A with Jan Shifren, MD, and Genevieve NealPerry, MD, PhD,” in the December 2022 issue of OBG Management at https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/article/260380/menopause

Continue to: Endometrial and bone safety...

Endometrial and bone safety

Results from Skylight 4, a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, 52-week safety study, provided additional evidence that confirmed the longer-term safety of fezolinetant over a 52-week treatment period.8

Endometrial safety was assessed in postmenopausal women with normal baseline endometrium (n = 599).8 For fezolinetant 45 mg, 1 of 203 participants had endometrial hyperplasia (EH) (0.5%; upper limit of one-sided 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.3%); no cases of EH were noted in the placebo (0 of 186) or fezolinetant 30-mg (0 of 210) groups. The incidence of EH or malignancy in fezolinetant-treated participants was within prespecified limits, as assessed by blinded, centrally read endometrial biopsies. Endometrial malignancy occurred in 1 of 210 in the fezolinetant 30-mg group (0.5%; 95% CI, 2.2%) with no cases in the other groups, thus meeting FDA requirements for endometrial safety.8

In addition, no significant differences were noted in change from baseline endometrial thickness on transvaginal ultrasonography between fezolinetant-treated and placebo groups. Likewise, no loss of bone density was found on dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans or trabecular bone scores.8

Liver safety

Although no cases of severe liver injury were noted, elevations in serum transaminase concentrations greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal were observed in the clinical trials. In Skylight 4, liver enzyme elevations more than 3 times the upper limit of normal occurred in 6 of 583 participants taking placebo, 8 of 590 taking fezolinetant 30 mg, and 12 of 589 taking fezolinetant 45 mg.8

The prescribing information for fezolinetant includes a warning for elevated hepatic transaminases: Fezolinetant should not be started if baseline serum transaminase concentration is equal to or exceeds 2 times the upper limit of normal. Liver tests should be obtained at baseline and repeated every 3 months for the first 9 months and then if symptoms suggest liver injury.11,12

Unmet need for nonhormone treatment of VMS

Vasomotor symptoms affect up to 80% of women, with approximately 25% bothersome enough to warrant treatment. Vasomotor symptoms persist for a median of 7 years, with duration and severity differing by race and ethnicity. Black, Hispanic, and possibly Native American women experience the highest burden of VMS.2 Although VMS, including hot flashes, night sweats, and mood and sleep disturbances, often are considered an annoyance to those with mild symptoms, moderate to severe VMS impact women’s lives, including functioning at home or work, affecting relationships, and decreasing perceived quality of life, and they have been associated with workplace absenteeism and increased health care costs, both direct from medical care and testing and indirect costs from lost work.13-15

Women with 7 or more daily moderate to severe VMS (defined as with sweating or affecting function) reported interference with sleep (94%), concentration (84%), mood (85%), energy (77%), and sexual activity (61%).16 Moderately to severely bothersome VMS have been associated with impaired psychological and general well-being, affecting work performance.17 Based on a Mayo Clinic workplace survey, Faubion and colleagues estimated an annual loss of $1.8 billion in the United States for menopause-related missed work and a $28 billion loss when medical expenses were added.15

Menopausal HT has been the primary treatment for VMS and has been shown to reduce the frequency and severity of hot flashes, with additional benefits on sleep, mood, fatigue, bone loss and reduction of fracture, and genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), and with potential improvement in cardiovascular health with decreased type 2 diabetes.18,19 For healthy women with early menopause and no contraindications, HT has been recommended until at least the age of natural menopause, as observational data suggest that HT prevents osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative changes, and sexual dysfunction for these women.19,20 Similarly, for healthy women younger than age 60 or within 10 years of menopause, initiating HT has been shown to be safe and effective in treating bothersome VMS and preventing osteoporotic fractures and genitourinary changes.19,21

Most systemic HT formulations are inexpensive (for example, available as generics), with multiple dosing and formulations available for use alone or combined as oral, transdermal, or vaginal therapies. Despite the fear that arose for clinicians and women from the initial 2002 findings of the Women’s Health Initiative regarding increased risk of breast cancer, stroke, venous thrombosis, cardiovascular disease, and dementia, major medical societies agree that when initiated at or soon after menopause, HT is a safe and effective therapy to relieve VMS, protect against bone loss, and treat genitourinary changes.19,21

Many women, however, cannot take HT, including those with estrogen-sensitive cancers, such as breast or uterine cancers; prior cardiovascular disease, stroke, or venous thrombotic events; severe endometriosis; or migraine headaches with visual auras.2 In addition, many symptomatic menopausal women without health contraindications choose not to take HT.2 Until now, the only FDA-approved VMS nonhormone therapy has been a low-dose 7.5-mg paroxetine salt. Unfortunately, this formulation, along with the off-label use of other antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors), gabapentinoids, oxybutynin, and clonidine, are substantially less effective than HT in treating moderate to severe VMS.

Bottom line

A substantial unmet need remains for effective therapy for moderate to severe VMS for women who cannot or choose not to take menopausal HT to relieve VMS.2,16 Effective, safe nonhormone treatment options such as the new NK3 receptor antagonist fezolinetant will address this clinically important need.

One concern is that the cost of developing and bringing to market the first of a new type of medication will be passed on to consumers, which may put it out of the price range for the many women who need it. However, the development and FDA approval of fezolinetant as the first NK3 receptor antagonist to treat menopausal VMS is potentially a practice changer. It provides a novel, effective, and safe FDA-approved nonhormonal treatment for menopausal women with moderate to severe VMS, particularly for women who cannot or will not take hormone therapy.

Continue to: When endometrial biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding reveals proliferative changes, how should we respond?...

When endometrial biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding reveals proliferative changes, how should we respond?

Abraham C. Proliferative endometrium in menopause: to treat or not to treat? Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:265-267. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005054.

The following case represents a common scenario for ObGyns.

CASE Patient with proliferative endometrial changes

A menopausal patient with a body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2 presents with uterine bleeding. She does not use systemic menopausal hormone therapy. Endometrial biopsy indicates proliferative changes.

When endometrial biopsy performed for bleeding reveals proliferative changes in menopausal women, we traditionally have responded by reassuring the patient that the findings are benign and advising that she should let us know if future spotting or bleeding occurs.

However, a recent review by Abraham published in Obstetrics and Gynecology details the implications of proliferative endometrial changes in menopausal patients, advising that treatment, as well as monitoring, may be appropriate.22

Endometrial changes and what they suggest

In premenopausal women, proliferative endometrial changes are physiologic and result from ovarian estrogen production early in each cycle, during what is called the proliferative (referring to the endometrium) or follicular (referring to the dominant follicle that synthesizes estrogen) phase. In menopausal women who are not using HT, however, proliferative endometrial changes, with orderly uniform glands seen on histologic evaluation, reflect aromatization of androgens by adipose and other tissues into estrogen.

The next step on the continuum to hyperplasia (benign or atypical) after proliferative endometrium is disordered proliferative endometrium. At this stage, histologic evaluation reveals scattered cystic and dilated glands that have a normal gland-to-stroma ratio with a low gland density overall and without any atypia. Randomly distributed glands may have tubal metaplasia or fibrin thrombi associated with microinfarcts, often presenting with irregular bleeding. This is a noncancerous change that occurs with excess estrogen (endogenous or exogenous).23

Progestins reverse endometrial hyperplasia by activating progesterone receptors, which leads to stromal decidualization with thinning of the endometrium. They have a pronounced effect on the histologic appearance of the endometrium. By contrast, endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN, previously known as endometrial hyperplasiawith atypia) shows underlying molecular mutations and histologic alterations and represents a sharp transition to true neoplasia, which greatly increases the risk of endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma.24

For decades, we have been aware that if women diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia are not treated with progestational therapy, their future risk of endometrial cancer is elevated. More recently, we also recognize that menopausal women found to have proliferative endometrial changes, if not treated, have an increased risk of endometrial cancer.

In a retrospective cohort study of almost 300 menopausal women who were not treated after endometrial biopsy revealed proliferative changes, investigators followed participants for an average of 11 years.25 These women had a mean BMI of 34 kg/m2. During follow-up, almost 12% of these women were diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia or cancer. This incidence of endometrial neoplasia was some 4 times higher than for women initially found to have atrophic endometrial changes.25

Progestin treatment

Oral progestin therapy with follow-up endometrial biopsy constitutes traditional management for endometrial hyperplasia. Such therapy minimizes the likelihood that hyperplasia will progress to endometrial cancer.

We now recognize that the convenience, as well as the high endometrial progestin levels achieved, with levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs) have advantages over oral progestin therapy in treating endometrial hyperplasia. Indeed, a recent US report found that among women with EIN managed medically, use of progestin-releasing IUDs has grown from 7.7% in 2008 to 35.6% in 2020.26

Although both oral and intrauterine progestin are highly effective in treating simple hyperplasia, progestin IUDs are substantially more effective than oral progestins in treating EIN.27 Progestin concentrations in the endometrium have been shown to be 100-fold higher after LNG-IUD placement compared with oral progestin use.22 In addition, adverse effects, including bloating, unpleasant mood changes, and increased appetite, are more common with oral than intrauterine progestin therapy.28

Unfortunately, data from randomized trials addressing progestational treatment of proliferative endometrium in menopausal women are not available to support the treatment of proliferative endometrium with either oral progestins or the LNG-IUD.22

Role of ultrasonography

Another concern is relying on a finding of thin endometrial thickness on vaginal ultrasonography. In a simulated retrospective cohort study, use of transvaginal ultrasonography to determine the appropriateness of a biopsy was found not to be sufficiently accurate or racially equitable with regard to Black women.29 In simulated data, transvaginal ultrasonography missed almost 5 times more cases of endometrial cancer among Black women compared with White women due to higher fibroid prevalence and nonendometrioid histologic type malignancies in Black women.29

Assessing risk

If proliferative endometrium is found, Abraham suggests assessing risk using22:

- age

- comorbidities (including obesity)

- endometrial echo thickness on vaginal ultrasonography.

Consider the patient’s risk and tolerance of recurrent bleeding as well as her tolerance for progestational adverse effects if medical therapy is chosen. Discussion about next steps should include reviewing the histologic findings with the patient and discussing the difference in risk of progression to endometrial cancer of a finding of proliferative endometrium compared with a histologic finding of endometrial hyperplasia.

Using this patient-centered approach, observation over time with follow-up endometrial biopsies remains a management option. Although some women may tolerate micronized progesterone over synthetic progestins, there is concern that it may be less effective in suppressing the endometrium than synthetic progestins.30 Accordingly, synthetic progestins represent first-line options in this setting.

In her review, Abraham suggests that when endometrial biopsy reveals proliferative changes in a menopausal woman, we should initiate progestin treatment and perform surveillance endometrial sampling every 3 to 6 months. If such sampling reveals benign but not proliferative endometrium, progestin therapy can be stopped and endometrial biopsy repeated if bleeding recurs.22 ●

ObGyns may choose to adopt Abraham’s approach or to hold off on progestin therapy while performing follow-up endometrial sampling. Either way, the take-home message is that the finding of proliferative endometrial changes on biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding requires proactive management.

- Modi M, Dhillo WS. Neurokinin 3 receptor antagonism: a novel treatment for menopausal hot flushes. Neuroendocrinology. 2019;109:242-248. doi:10.1159/000495889

- Pinkerton JV, Redick DL, Homewood LN, et al. Neurokinin receptor antagonist, fezolinetant, for treatment of menopausal vasomotor symptoms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;dgad209. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad209

- Rance NE, Dacks PA, Mittelman-Smith MA, et al. Modulation of body temperature and LH secretion by hypothalamic KNDy (kisspeptin, neurokinin B and dynorphin) neurons: a novel hypothesis on the mechanism of hot flushes. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2013;34:211-227. doi:10.1016 /j.yfrne.2013.07.003

- Mittelman-Smith MA, Williams H, Krajewski-Hall SJ, et al. Role for kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) neurons in cutaneous vasodilatation and the estrogen modulation of body temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:1984619851. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211517109

- Astellas Pharma. Astellas’ Veozah (fezolinetant) approved by US FDA for treatment of vasomotor symptoms due to menopause. May 12, 2023. PR Newswire. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/astellas-veozah-fezolinetant-approved-by-us-fda-for -treatment-of-vasomotor-symptoms-due-to-menopause -301823639.html

- Johnson KA, Martin N, Nappi RE, et al. Efficacy and safety of fezolinetant in moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a phase 3 RCT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;dgad058. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad058

- Lederman S, Ottery FD, Cano A, et al. Fezolinetant for treatment of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause (SKYLIGHT 1): a phase 3 randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2023;401:1091-1102. doi:10.1016 /S0140-6736(23)00085-5

- Neal-Perry G, Cano A, Lederman S, et al. Safety of fezolinetant for vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:737-747. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005114

- Depypere H, Timmerman D, Donders G, et al. Treatment of menopausal vasomotor symptoms with fezolinetant, a neurokinin 3 receptor antagonist: a phase 2a trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:5893-5905. doi: 10.1210/jc .2019-00677

- Santoro N, Waldbaum A, Lederman S, et al. Effect of the neurokinin 3 receptor antagonist fezolinetant on patientreported outcomes in postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, dose-ranging study (VESTA). Menopause. 2020;27:1350-1356. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001621

- FDA approves novel drug to treat moderate to severe hot flashes caused by menopause. May 12, 2023. US Food and Drug Administration. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www .fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves -novel-drug-treat-moderate-severe-hot-flashes-caused -menopause

- Veozah. Prescribing information. Astellas; 2023. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://www.astellas.com/us/system/files /veozah_uspi.pdf

- Pinkerton JV. Money talks: untreated hot flashes cost women, the workplace, and society. Menopause. 2015;22:254-255. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000427

- Sarrel P, Portman D, Lefebvre P, et al. Incremental direct and indirect costs of untreated vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. 2015;22(3):260-266. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000320

- Faubion SS, Enders F, Hedges MS, et al. Impact of menopause symptoms on women in the workplace. Mayo Clin Proc. 2023;98:833-845. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.02.025

- Williams RE, Levine KB, Kalilani L, et al. Menopause- specific questionnaire assessment in US populationbased study shows negative impact on health-related quality of life. Maturitas. 2009;62:153-159. doi:10.1016 /j.maturitas.2008.12.006

- Gartoulla P, Bell RJ, Worsley R, et al. Moderate-severely bothersome vasomotor symptoms are associated with lowered psychological general wellbeing in women at midlife. Maturitas. 2015;81:487-492. doi:10.1016 /j.maturitas.2015.06.004

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management—getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:803-806. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1514242

- 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of the North American Menopause Society Advisory Panel. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2022;29:767-794. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000002028

- Kaunitz AM, Kapoor E, Faubion S. Treatment of women after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed prior to natural menopause. JAMA. 2021;12;326:1429-1430. doi:10.1001 /jama.2021.3305

- Pinkerton JV. Hormone therapy for postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:446-455. doi:10.1056 /NEJMcp1714787

- Abraham C. Proliferative endometrium in menopause: to treat or not to treat? Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:265-267. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005054

- Chandra V, Kim JJ, Benbrook DM, et al. Therapeutic options for management of endometrial hyperplasia. J Gynecol Oncol. 2016;27:e8. doi:10.3802/jgo.2016.27.e8

- Owings RA, Quick CM. Endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:484-491. doi:10.5858 /arpa.2012-0709-RA

- Rotenberg O, Doulaveris G, Fridman D, et al. Long-term outcome of postmenopausal women with proliferative endometrium on endometrial sampling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:896.e1-896.e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.045

- Suzuki Y, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Systemic progestins and progestin-releasing intrauterine device therapy for premenopausal patients with endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:979-987. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005124

- Mandelbaum RS, Ciccone MA, Nusbaum DJ, et al. Progestin therapy for obese women with complex atypical hyperplasia: levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device vs systemic therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:103.e1-103.e13. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.12.273

- Liu S, Kciuk O, Frank M, et al. Progestins of today and tomorrow. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2022;34:344-350. doi:10.1097 /GCO.0000000000000819

- Doll KM, Romano SS, Marsh EE, et al. Estimated performance of transvaginal ultrasonography for evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding in a simulated cohort of black and white women in the US. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1158-1165. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1700

- Gompel A. Progesterone and endometrial cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;69:95-107. doi:10.1016 /j.bpobgyn.2020.05.003

- Modi M, Dhillo WS. Neurokinin 3 receptor antagonism: a novel treatment for menopausal hot flushes. Neuroendocrinology. 2019;109:242-248. doi:10.1159/000495889

- Pinkerton JV, Redick DL, Homewood LN, et al. Neurokinin receptor antagonist, fezolinetant, for treatment of menopausal vasomotor symptoms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;dgad209. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad209

- Rance NE, Dacks PA, Mittelman-Smith MA, et al. Modulation of body temperature and LH secretion by hypothalamic KNDy (kisspeptin, neurokinin B and dynorphin) neurons: a novel hypothesis on the mechanism of hot flushes. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2013;34:211-227. doi:10.1016 /j.yfrne.2013.07.003

- Mittelman-Smith MA, Williams H, Krajewski-Hall SJ, et al. Role for kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) neurons in cutaneous vasodilatation and the estrogen modulation of body temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:1984619851. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211517109

- Astellas Pharma. Astellas’ Veozah (fezolinetant) approved by US FDA for treatment of vasomotor symptoms due to menopause. May 12, 2023. PR Newswire. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/astellas-veozah-fezolinetant-approved-by-us-fda-for -treatment-of-vasomotor-symptoms-due-to-menopause -301823639.html

- Johnson KA, Martin N, Nappi RE, et al. Efficacy and safety of fezolinetant in moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a phase 3 RCT. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;dgad058. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad058

- Lederman S, Ottery FD, Cano A, et al. Fezolinetant for treatment of moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause (SKYLIGHT 1): a phase 3 randomised controlled study. Lancet. 2023;401:1091-1102. doi:10.1016 /S0140-6736(23)00085-5

- Neal-Perry G, Cano A, Lederman S, et al. Safety of fezolinetant for vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:737-747. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005114

- Depypere H, Timmerman D, Donders G, et al. Treatment of menopausal vasomotor symptoms with fezolinetant, a neurokinin 3 receptor antagonist: a phase 2a trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:5893-5905. doi: 10.1210/jc .2019-00677

- Santoro N, Waldbaum A, Lederman S, et al. Effect of the neurokinin 3 receptor antagonist fezolinetant on patientreported outcomes in postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, dose-ranging study (VESTA). Menopause. 2020;27:1350-1356. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001621

- FDA approves novel drug to treat moderate to severe hot flashes caused by menopause. May 12, 2023. US Food and Drug Administration. Accessed May 15, 2023. https://www .fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves -novel-drug-treat-moderate-severe-hot-flashes-caused -menopause

- Veozah. Prescribing information. Astellas; 2023. Accessed May 16, 2023. https://www.astellas.com/us/system/files /veozah_uspi.pdf

- Pinkerton JV. Money talks: untreated hot flashes cost women, the workplace, and society. Menopause. 2015;22:254-255. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000427

- Sarrel P, Portman D, Lefebvre P, et al. Incremental direct and indirect costs of untreated vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. 2015;22(3):260-266. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000320

- Faubion SS, Enders F, Hedges MS, et al. Impact of menopause symptoms on women in the workplace. Mayo Clin Proc. 2023;98:833-845. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.02.025

- Williams RE, Levine KB, Kalilani L, et al. Menopause- specific questionnaire assessment in US populationbased study shows negative impact on health-related quality of life. Maturitas. 2009;62:153-159. doi:10.1016 /j.maturitas.2008.12.006

- Gartoulla P, Bell RJ, Worsley R, et al. Moderate-severely bothersome vasomotor symptoms are associated with lowered psychological general wellbeing in women at midlife. Maturitas. 2015;81:487-492. doi:10.1016 /j.maturitas.2015.06.004

- Manson JE, Kaunitz AM. Menopause management—getting clinical care back on track. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:803-806. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1514242

- 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of the North American Menopause Society Advisory Panel. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2022;29:767-794. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000002028

- Kaunitz AM, Kapoor E, Faubion S. Treatment of women after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed prior to natural menopause. JAMA. 2021;12;326:1429-1430. doi:10.1001 /jama.2021.3305

- Pinkerton JV. Hormone therapy for postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:446-455. doi:10.1056 /NEJMcp1714787

- Abraham C. Proliferative endometrium in menopause: to treat or not to treat? Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:265-267. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005054

- Chandra V, Kim JJ, Benbrook DM, et al. Therapeutic options for management of endometrial hyperplasia. J Gynecol Oncol. 2016;27:e8. doi:10.3802/jgo.2016.27.e8

- Owings RA, Quick CM. Endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:484-491. doi:10.5858 /arpa.2012-0709-RA

- Rotenberg O, Doulaveris G, Fridman D, et al. Long-term outcome of postmenopausal women with proliferative endometrium on endometrial sampling. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:896.e1-896.e7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.045

- Suzuki Y, Chen L, Hou JY, et al. Systemic progestins and progestin-releasing intrauterine device therapy for premenopausal patients with endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:979-987. doi:10.1097 /AOG.0000000000005124

- Mandelbaum RS, Ciccone MA, Nusbaum DJ, et al. Progestin therapy for obese women with complex atypical hyperplasia: levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device vs systemic therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:103.e1-103.e13. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.12.273

- Liu S, Kciuk O, Frank M, et al. Progestins of today and tomorrow. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2022;34:344-350. doi:10.1097 /GCO.0000000000000819

- Doll KM, Romano SS, Marsh EE, et al. Estimated performance of transvaginal ultrasonography for evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding in a simulated cohort of black and white women in the US. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1158-1165. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1700

- Gompel A. Progesterone and endometrial cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;69:95-107. doi:10.1016 /j.bpobgyn.2020.05.003

The perimenopausal period and the benefits of progestin IUDs

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) are now used by more than 15% of US contraceptors. The majority of these IUDs release the progestin levonorgestrel, and with now longer extended use of the IUDs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA),1-3 they become even more attractive for use for contraception,control of menorrhagia or heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) during reproductive years and perimenopause, and potentially, although not FDA approved for this purpose, postmenopause for endometrial protection in estrogen users. In this roundtable discussion, we will look at some of the benefits of the IUD for contraception effectiveness and control of bleeding, as well as the potential risks if used for postmenopausal women.

Progestin IUDs and contraception

JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD, NCMP: Dr. Kaunitz, what are the contraceptive benefits of progestin IUDs during perimenopause?

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD, NCMP: We know fertility declines as women approach menopause. However, when pregnancy occurs in older reproductive-age women, the pregnancies are often unintended, as reflected by high rates of induced abortion in this population. In addition, the prevalence of maternal comorbidities (during pregnancy and delivery) is higher in older reproductive-age women, with the maternal mortality rate more than 5 times higher compared with that of younger women.4 Two recently published clinical trials assessed the extended use of full-size IUDs containing 52 mg of levonor-gestrel (LNG), with the brand names Mirena and Liletta.1,2 The data from these trials confirmed that both IUDs remain highly effective for up to 8 years of use, and currently, both devices are approved for up to 8 years of use. One caveat is that, in the unusual occurrence of a pregnancy being diagnosed in a woman using an IUD, we as clinicians, must be alert to the high prevalence of ectopic pregnancies in this setting.

Progestin IUDs and HMB

Dr. Pinkerton: Dr. Goldstein, can you comment on how well progestin IUDs work for HMB?

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, NCMP, CCD: Many women who need contraception will use these devices for suppressing HMB, and they can be quite effective, if the diagnosis truly is HMB, at reducing bleeding.5 But that efficacy in bleeding reduction may not be quite as long as the efficacy in pregnancy prevention.6 In my experience, among women using IUDs specifically for their HMB, good bleeding control may require changing the IUD at 3 to 5 years.

Barbara S. Levy, MD: When inserting a LNG-IUD for menorrhagia in the perimenopausal time frame, sometimes I will do a progestin withdrawal first, which will thin the endometrium and induce withdrawal bleeding because, in my experience, if you place an IUD in someone with perimenopausal bleeding, you may end up with a lot of breakthrough bleeding.

Perimenopause and hot flashes