User login

Ocular Complications of Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition with a lifetime prevalence of 15% to 20% in industrialized countries.1 It affects both children and adults and is predominantly characterized by a waxing and waning course of eczematous skin lesions and pruritus. In recent years, there is increasing recognition that AD can present with extracutaneous findings. Large-scale epidemiologic studies have reported a notably higher prevalence of ophthalmic complications in the AD population compared to the general population, in a severity-dependent manner.2,3 Potential complications include blepharitis, keratoconjunctivitis, keratoconus, glaucoma, cataracts, retinal detachment, ophthalmic herpes simplex virus infections, and dupilumab-associated ocular complications.

The etiology of each ocular complication in the context of AD is complex and likely multifactorial. Intrinsic immune dysregulation, physical trauma from eye rubbing, AD medication side effects, and genetics all have been speculated to play a role.2 Some of these ocular complications have a chronic course, while others present with sudden onset of symptoms; many of them can result in visual impairment if undiagnosed or left untreated. This article reviews several of the most common ocular comorbidities associated with AD. We discuss the clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and management strategies for each condition.

Blepharitis

Blepharitis, an inflammatory condition of the eyelids, is estimated to affect more than 6% of patients with AD compared to less than 1% of the general population.2 Blepharitis can be classified as anterior or posterior, based on the anatomic location of the affected region relative to the lash margin. Affected individuals may experience pruritus and irritation of the eyelids, tearing, a foreign body or burning sensation, crusting of the eyelids, and photophobia.4 Anterior blepharitis commonly is due to staphylococcal disease, and posterior blepharitis is secondary to structural changes and obstruction of meibomian gland orifices.

Although the pathophysiology is not well defined, xerosis in atopic patients is accompanied by barrier disruption and transepidermal water loss, which promote eyelid skin inflammation.

The mainstay of therapy for atopic blepharitis consists of conventional lid hygiene regimens, such as warm compresses and gentle scrubbing of the lid margins to remove crust and debris, which can be done with nonprescription cleansers, pads, and baby shampoos. Acute exacerbations may require topical antibiotics (ie, erythromycin or bacitracin applied to the lid margins once daily), topical calcineurin inhibitors (ie, cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05%), or low-potency topical corticosteroids (ie, fluorometholone 0.1% or loteprednol etabonate 0.5% ophthalmic suspensions).5 Due to potential side effects of medications, especially topical corticosteroids, patients should be referred to ophthalmologists for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

Keratoconjunctivitis

Atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) is a noninfectious inflammatory condition of the cornea and conjunctiva that occurs in an estimated 25% to 42% of patients with AD.6,7 It frequently presents in late adolescence and has a peak incidence between 30 and 50 years of age.8 The symptoms of AKC include ocular pruritus, redness, ropy mucoid discharge, burning discomfort, photophobia, and blurring of vision. Corneal involvement can progress to corneal neovascularization and punctate or macroepithelial erosions and ulcerations, which increase the risk for corneal scarring and visual impairment.7

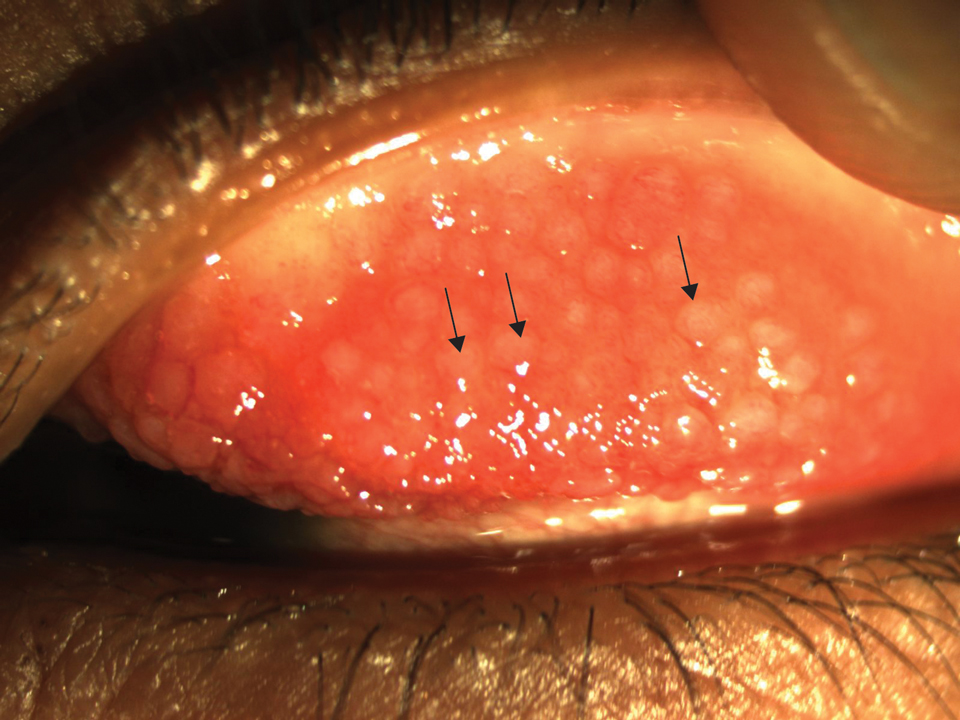

Keratoconjunctivitis is a complex inflammatory disease characterized by infiltration of the conjunctival epithelium by eosinophils, mast cells, and lymphocytes. On examination, patients frequently are found to have concurrent AD of the periorbital skin as well as papillary hypertrophy of the tarsal conjunctiva with accompanying fibrosis, which can lead to entropion (turning inward of the lid margins and lashes) in severe cases.7 Ophthalmic evaluation is strongly recommended for patients with AKC to control symptoms, to limit exacerbations, and to prevent sight-threatening inflammation leading to vision loss. Treatment can be challenging given the chronicity of the condition and may require multiple treatment arms. Conservative measures include cool compresses and treatment with ophthalmic eye drops containing antihistamines (ie, ketotifen 0.025% [available over-the-counter]) and mast cell stabilizers (ie, olopatadine ophthalmic solution 0.1%).8 Atopic keratoconjunctivitis exacerbations may require short-term use of topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors, or systemic equivalents for refractory cases.6 Long-term maintenance therapy typically consists of proper eye hygiene and steroid-sparing agents that reduce ocular inflammation, such as topical cyclosporine and tacrolimus, neither of which are associated with increased intraocular pressure (IOP)(Figure 1).8 Cornea disease resulting from chronic conjunctival/lid microtrauma can be managed with soft or scleral contact lenses.

Keratoconus

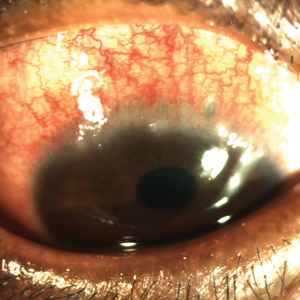

Keratoconus is a noninflammatory ocular disorder characterized by progressive thinning and conelike protrusion of the cornea. The corneal topographic changes result in high irregular astigmatism and reduced visual acuity, which can manifest as image blurring or distortion (Figure 2).2,9 Multiple case series and controlled studies have reported a positive association between keratoconus and a history of atopic disease.10,11

The precise etiology of keratoconus in the context of AD is unclear and likely is multifactorial. Habitual eye rubbing from periocular pruritus and discomfort has been reported to be a notable contributor to keratoconus.12 In addition, intrinsic inflammation and imbalance of cytokines and proteases also may contribute to development of keratoconus.13

Keratoconus is a progressive condition that can severely impact vision, making it critical to diagnose patients before irreversible vision loss occurs. Individuals with risk factors, such as AD of the eyelids, history of eye rubbing, or family history of keratoconus, should be advised to receive routine vision screening for worsening astigmatism, especially during the first few decades of life when keratoconus progresses rapidly.

The conservative management for early keratoconus includes glasses and gas-permeable contact lenses for correction of visual acuity and astigmatism. For advanced keratoconus, scleral lenses often are prescribed. These large-diameter, gas-permeable lenses are designed to rest on the sclera and arch over the entire cornea.9 Alternatively, corneal collagen cross-linking is a newer technique that utilizes riboflavin and UVA irradiation to strengthen the corneal tissue. It has proven to be safe and effective in slowing or stopping the progression of keratoconus, particularly when treated at the early stage, and received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2016.9

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a well-known complication of AD and can lead to irreversible ocular hypertension and optic nerve damage. Corticosteroid use is a major risk factor for glaucoma, and the rise in IOP is thought to be due to increased aqueous outflow resistance.14

Multiple case reports have linked glaucoma to long-term use of potent topical corticosteroids in the facial and palpebral regions, which has been attributed to direct steroid contact and absorption by ocular tissues, as glaucoma rarely occurs with topical steroid application elsewhere on the body.15-17 Systemic steroids (ie, prednisolone) taken for more than 8 weeks also have been associated with a marked rise in IOP.18

Certain risk factors may predispose a steroid user to increased IOP, including existing open-angle glaucoma, diabetes mellitus, collagen disease, and high myopia.15,19 Steroid responders and younger individuals also demonstrate increased sensitivity to steroids.20

Given that glaucoma often is asymptomatic until advanced stages, early detection is the key for proper intervention. Periodic glaucoma screening by an ophthalmologist would be appropriate for known steroid responders, as well as patients with a prolonged history of topical steroid application in the palpebral region and systemic steroid use, family history of glaucoma, or known ocular pathology.21 Furthermore, patients with concurrent glaucoma and AD should be jointly managed by dermatology and ophthalmology, and systemic and topical corticosteroid use should be minimized in favor of alterative agents such as calcineurin inhibitors.22

In addition to steroid-induced glaucoma, intrinsic atopic glaucoma recently has been proposed as a clinical entity and is characterized by increased inflammatory cytokines—IL-8 and CCL2—in the aqueous humor and abnormal accumulation of fibers in corneoscleral meshwork.23

Cataracts

Cataracts are estimated to affect 8% to 25% of patients with AD.21,24 Unlike age-related cataracts, cataracts associated with AD are observed in adolescents and young adults in addition to the older population. The progression of lenticular opacity can rapidly occur and has been reported to coincide with AD flares.25,26

Patients with AD typically present with anterior or posterior subcapsular cataracts instead of nuclear and cortical cataracts, which are more common in the general population.27,28 Anterior subcapsular cataracts are more specific to AD, whereas posterior subcapsular cataracts are associated with both prolonged corticosteroid use and AD.26 Children generally are more sensitive to steroids than adults and may develop cataracts more rapidly and at lower concentrations.29

The pathophysiology of cataract formation and progression in the context of AD is multifactorial. Cataract patients with AD have compromised blood-retinal barrier integrity as well as increased oxidative damage in the lens.30,31 Genetics and blunt trauma from eye rubbing are thought to play a role, and the latter has been associated with faster progression of cataracts.28 In contrast, corticosteroid-induced cataracts likely are caused by transcriptional changes and disrupted osmotic balance in the lens fibers, which can lead to fiber rupture and lens opacification.26,32 Systemic corticosteroids show the strongest association with cataract development, but inhaled and topical steroids also have been implicated.26

Although cataracts can be surgically corrected, prevention is critical. Patients with early-onset periorbital AD, prolonged use of topical or systemic corticosteroids, and family history of cataracts should be routinely screened. Anterior and posterior subcapsular cataracts are diagnosed with red reflex examinations that can be readily performed by the primary care physician or ophthalmologist.33 Atopic dermatitis patients with cataracts should be advised to use calcineurin inhibitors and alternative treatments in place of corticosteroids.

Retinal Detachment

Retinal detachment (RD) is a serious complication of AD that can present in individuals younger than 35 years. The incidence of RD in patients with AD has been estimated to be 4% to 8%.34 Retinal detachment manifests with visual disturbances such as flashing lights, shadows, visual field defect, and blurring of vision, but also may occur in the absence of vision changes.35,36

Across multiple case series, patients who developed RD were consistently found to have AD in the facial or periorbital region and a history of chronic eye rubbing. Multiple patients also presented with concurrent proliferative vitreoretinopathy, lens subluxation, and/or cataracts.35,37 The mechanism for RD has been attributed to ocular contusion from vigorous eye rubbing, as fundus findings between traumatic and AD-associated RD are similarly characterized by tractional breaks in the retina at vitreous base borders.37

Avoidance of eye rubbing and optimized treatment of facial AD may help prevent RD in patients with AD. Furthermore, all patients with symptoms of RD should be immediately referred to ophthalmology for surgical repair.

Herpetic Ocular Disease

Ocular herpes simplex virus infections cause ocular pain and are associated with notable visual morbidity, as recurrences can result in irreversible corneal scarring and neovascularization. Two retrospective case-control studies independently reported that individuals with a history of AD are at greater risk for herpetic ocular disease compared to age-matched controls.38,39 Furthermore, atopic disease is associated with higher recurrence rates and slower regeneration of the corneal epithelium.40

These findings suggest that AD patients with a history of recurrent herpetic ocular diseases should be closely monitored and treated with antiviral prophylaxis and/or topical corticosteroids, depending on the type of keratitis (epithelial or stromal).40 Furthermore, active ocular herpetic infections warrant urgent referral to an ophthalmologist.

Dupilumab-Associated Ocular Complications

Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, is the first biologic therapy to be approved for treatment of moderate to severe AD. Prior clinical trials have described a higher incidence of anterior conjunctivitis in dupilumab-treated AD patients (5%–28%) compared to placebo (2%–11%).41 Of note, the incidence may be as high as 70%, as reported in a recent case series.42 Interestingly, independent trials assessing dupilumab treatment in asthma, nasal polyposis, and eosinophilic esophagitis patients did not observe a higher incidence of conjunctivitis in dupilumab-treated patients compared to placebo, suggesting an AD-specific mechanism.43

Prominent features of dupilumab-associated conjunctivitis include hyperemia of the conjunctiva and limbus, in addition to ocular symptoms such as tearing, burning, and bilateral decrease in visual acuity. Marked reduction of conjunctival goblet cells has been reported.44 In addition to conjunctivitis, blepharitis also has been reported during dupilumab treatment.45

Standardized treatment guidelines for dupilumab-associated ocular complications have not yet been established. Surprisingly, antihistamine eye drops appear to be inefficacious in the treatment of dupilumab-associated conjunctivitis.41 However, the condition has been successfully managed with topical steroids (fluorometholone ophthalmic suspension 0.1%) and tacrolimus ointment 0.03%.41 Lifitegrast, an anti-inflammatory agent approved for chronic dry eye, also has been suggested as a treatment option for patients refractory to topical steroids.45 Alternatively, cessation of dupilumab could be considered in AD patients who experience severe ocular complications. Atopic dermatitis patients taking dupilumab who have any concerning signs for ocular complications should be referred to an ophthalmologist for further diagnosis and management.

Conclusion

Practicing dermatologists likely will encounter patients with concurrent AD and ocular complications. Although eye examinations are not routinely performed in the care of AD patients, dermatologists can proactively inquire about ocular symptoms and monitor patients longitudinally. Early diagnosis and treatment of these ocular conditions can prevent vision loss in these patients. Furthermore, symptomatic control of AD and careful consideration of the side-effect profiles of medications can potentially reduce the incidence of ocular complications in individuals with AD.

Patients with visual concerns or risk factors, such as a history of vigorous eye rubbing or chronic corticosteroid use, should be jointly managed with an ophthalmologist for optimized care. Moreover, acute exacerbations of ocular symptoms and visual deterioration warrant urgent referral to ophthalmology.

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1.

- Govind K, Whang K, Khanna R, et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with increased prevalence of multiple ocular comorbidities. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:298-299.

- Thyssen JP, Toft PB, Halling-Overgaard AS, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and risk of selected ocular disease in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:280-286.e281.

- Putnam CM. Diagnosis and management of blepharitis: an optometrist’s perspective. Clin Optom (Auckl). 2016;8:71-78.

- Amescua G, Akpek EK, Farid M, et al. Blepharitis Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:P56-P93.

- Bielory B, Bielory L. Atopic dermatitis and keratoconjunctivitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010;30:323-336.

- Guglielmetti S, Dart JK, Calder V. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:478-485.

- Chen JJ, Applebaum DS, Sun GS, et al. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:569-575.

- Andreanos KD, Hashemi K, Petrelli M, et al. Keratoconus treatment algorithm. Ophthalmol Ther. 2017;6:245-262.

- Rahi A, Davies P, Ruben M, et al. Keratoconus and coexisting atopic disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1977;61:761-764.

- Gasset AR, Hinson WA, Frias JL. Keratoconus and atopic diseases. Ann Ophthalmol. 1978;10:991-994.

- Bawazeer AM, Hodge WG, Lorimer B. Atopy and keratoconus: a multivariate analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:834-836.

- Galvis V, Sherwin T, Tello A, et al. Keratoconus: an inflammatory disorder? Eye (Lond). 2015;29:843-859.

- Clark AF, Wordinger RJ. The role of steroids in outflow resistance. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:752-759.

- Daniel BS, Orchard D. Ocular side-effects of topical corticosteroids: what a dermatologist needs to know. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:164-169.

- Garrott HM, Walland MJ. Glaucoma from topical corticosteroids to the eyelids. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;32:224-226.

- Aggarwal RK, Potamitis T, Chong NH, et al. Extensive visual loss with topical facial steroids. Eye (Lond). 1993;7(pt 5):664-666.

- Mandapati JS, Metta AK. Intraocular pressure variation in patients on long-term corticosteroids. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2011;2:67-69.

- Jones R 3rd, Rhee DJ. Corticosteroid-induced ocular hypertension and glaucoma: a brief review and update of the literature. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:163-167.

- Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Yasuoka N, Ueta M, et al. Influence of topical steroids on intraocular pressure in patients with atopic dermatitis. Allergol Int. 2018;67:388-391.

- Bercovitch L. Screening for ocular complications in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:588-589.

- Abramovits W, Hung P, Tong KB. Efficacy and economics of topical calcineurin inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:213-222.

- Takakuwa K, Hamanaka T, Mori K, et al. Atopic glaucoma: clinical and pathophysiological analysis. J Glaucoma. 2015;24:662-668.

- Haeck IM, Rouwen TJ, Timmer-de Mik L, et al. Topical corticosteroids in atopic dermatitis and the risk of glaucoma and cataracts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:275-281.

- Amemiya T, Matsuda H, Uehara M. Ocular findings in atopic dermatitis with special reference to the clinical features of atopic cataract. Ophthalmologica. 1980;180:129-132.

- Tatham A. Atopic dermatitis, cutaneous steroids and cataracts in children: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:124.

- Chew M, Chiang PP, Zheng Y, et al. The impact of cataract, cataract types, and cataract grades on vision-specific functioning using Rasch analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:29-38.

- Nagaki Y, Hayasaka S, Kadoi C. Cataract progression in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25:96-99.

- Kaye LD, Kalenak JW, Price RL, et al. Ocular implications of long-term prednisone therapy in children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1993;30:142-144.

- Matsuo T, Saito H, Matsuo N. Cataract and aqueous flare levels in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:36-39.

- Namazi MR, Handjani F, Amirahmadi M. Increased oxidative activity from hydrogen peroxide may be the cause of the predisposition to cataracts among patients with atopic dermatitis. Med Hypotheses. 2006;66:863-864.

- James ER. The etiology of steroid cataract. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2007;23:403-420.

- Lambert SR, Teng JMC. Assessing whether the cataracts associated with atopic dermatitis are associated with steroids or inflammatory factors. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:918-919.

- Sasoh M, Mizutani H, Matsubara H, et al. Incidence of retinal detachment associated with atopic dermatitis in Japan: review of cases from 1992 to 2011. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:1129-1134.

- Yoneda K, Okamoto H, Wada Y, et al. Atopic retinal detachment. report of four cases and a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:586-591.

- Gnana Jothi V, McGimpsey S, Sharkey JA, et al. Retinal detachment repair and cataract surgery in patients with atopic dermatitis. Eye (Lond). 2017;31:1296-1301.

- Oka C, Ideta H, Nagasaki H, et al. Retinal detachment with atopic dermatitis similar to traumatic retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1050-1054.

- Prabriputaloong T, Margolis TP, Lietman TM, et al. Atopic disease and herpes simplex eye disease: a population-based case-control study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:745-749.

- Borkar DS, Gonzales JA, Tham VM, et al. Association between atopy and herpetic eye disease: results from the pacific ocular inflammation study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:326-331.

- Rezende RA, Hammersmith K, Bisol T, et al. Comparative study of ocular herpes simplex virus in patients with and without self-reported atopy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:1120-1125.

- Wollenberg A, Ariens L, Thurau S, et al. Conjunctivitis occurring in atopic dermatitis patients treated with dupilumab-clinical characteristics and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1778-1780.e1.

- Ivert LU, Wahlgren CF, Ivert L, et al. Eye complications during dupilumab treatment for severe atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:375-378.

- Akinlade B, Guttman-Yassky E, de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Conjunctivitis in dupilumab clinical trials [published online March 9, 2019]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.17869.

- Bakker DS, Ariens LFM, van Luijk C, et al. Goblet cell scarcity and conjunctival inflammation during treatment with dupilumab in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1248-1249.

- Zirwas MJ, Wulff K, Beckman K. Lifitegrast add-on treatment for dupilumab-induced ocular surface disease (DIOSD): a novel case report. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:34-36.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition with a lifetime prevalence of 15% to 20% in industrialized countries.1 It affects both children and adults and is predominantly characterized by a waxing and waning course of eczematous skin lesions and pruritus. In recent years, there is increasing recognition that AD can present with extracutaneous findings. Large-scale epidemiologic studies have reported a notably higher prevalence of ophthalmic complications in the AD population compared to the general population, in a severity-dependent manner.2,3 Potential complications include blepharitis, keratoconjunctivitis, keratoconus, glaucoma, cataracts, retinal detachment, ophthalmic herpes simplex virus infections, and dupilumab-associated ocular complications.

The etiology of each ocular complication in the context of AD is complex and likely multifactorial. Intrinsic immune dysregulation, physical trauma from eye rubbing, AD medication side effects, and genetics all have been speculated to play a role.2 Some of these ocular complications have a chronic course, while others present with sudden onset of symptoms; many of them can result in visual impairment if undiagnosed or left untreated. This article reviews several of the most common ocular comorbidities associated with AD. We discuss the clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and management strategies for each condition.

Blepharitis

Blepharitis, an inflammatory condition of the eyelids, is estimated to affect more than 6% of patients with AD compared to less than 1% of the general population.2 Blepharitis can be classified as anterior or posterior, based on the anatomic location of the affected region relative to the lash margin. Affected individuals may experience pruritus and irritation of the eyelids, tearing, a foreign body or burning sensation, crusting of the eyelids, and photophobia.4 Anterior blepharitis commonly is due to staphylococcal disease, and posterior blepharitis is secondary to structural changes and obstruction of meibomian gland orifices.

Although the pathophysiology is not well defined, xerosis in atopic patients is accompanied by barrier disruption and transepidermal water loss, which promote eyelid skin inflammation.

The mainstay of therapy for atopic blepharitis consists of conventional lid hygiene regimens, such as warm compresses and gentle scrubbing of the lid margins to remove crust and debris, which can be done with nonprescription cleansers, pads, and baby shampoos. Acute exacerbations may require topical antibiotics (ie, erythromycin or bacitracin applied to the lid margins once daily), topical calcineurin inhibitors (ie, cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05%), or low-potency topical corticosteroids (ie, fluorometholone 0.1% or loteprednol etabonate 0.5% ophthalmic suspensions).5 Due to potential side effects of medications, especially topical corticosteroids, patients should be referred to ophthalmologists for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

Keratoconjunctivitis

Atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) is a noninfectious inflammatory condition of the cornea and conjunctiva that occurs in an estimated 25% to 42% of patients with AD.6,7 It frequently presents in late adolescence and has a peak incidence between 30 and 50 years of age.8 The symptoms of AKC include ocular pruritus, redness, ropy mucoid discharge, burning discomfort, photophobia, and blurring of vision. Corneal involvement can progress to corneal neovascularization and punctate or macroepithelial erosions and ulcerations, which increase the risk for corneal scarring and visual impairment.7

Keratoconjunctivitis is a complex inflammatory disease characterized by infiltration of the conjunctival epithelium by eosinophils, mast cells, and lymphocytes. On examination, patients frequently are found to have concurrent AD of the periorbital skin as well as papillary hypertrophy of the tarsal conjunctiva with accompanying fibrosis, which can lead to entropion (turning inward of the lid margins and lashes) in severe cases.7 Ophthalmic evaluation is strongly recommended for patients with AKC to control symptoms, to limit exacerbations, and to prevent sight-threatening inflammation leading to vision loss. Treatment can be challenging given the chronicity of the condition and may require multiple treatment arms. Conservative measures include cool compresses and treatment with ophthalmic eye drops containing antihistamines (ie, ketotifen 0.025% [available over-the-counter]) and mast cell stabilizers (ie, olopatadine ophthalmic solution 0.1%).8 Atopic keratoconjunctivitis exacerbations may require short-term use of topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors, or systemic equivalents for refractory cases.6 Long-term maintenance therapy typically consists of proper eye hygiene and steroid-sparing agents that reduce ocular inflammation, such as topical cyclosporine and tacrolimus, neither of which are associated with increased intraocular pressure (IOP)(Figure 1).8 Cornea disease resulting from chronic conjunctival/lid microtrauma can be managed with soft or scleral contact lenses.

Keratoconus

Keratoconus is a noninflammatory ocular disorder characterized by progressive thinning and conelike protrusion of the cornea. The corneal topographic changes result in high irregular astigmatism and reduced visual acuity, which can manifest as image blurring or distortion (Figure 2).2,9 Multiple case series and controlled studies have reported a positive association between keratoconus and a history of atopic disease.10,11

The precise etiology of keratoconus in the context of AD is unclear and likely is multifactorial. Habitual eye rubbing from periocular pruritus and discomfort has been reported to be a notable contributor to keratoconus.12 In addition, intrinsic inflammation and imbalance of cytokines and proteases also may contribute to development of keratoconus.13

Keratoconus is a progressive condition that can severely impact vision, making it critical to diagnose patients before irreversible vision loss occurs. Individuals with risk factors, such as AD of the eyelids, history of eye rubbing, or family history of keratoconus, should be advised to receive routine vision screening for worsening astigmatism, especially during the first few decades of life when keratoconus progresses rapidly.

The conservative management for early keratoconus includes glasses and gas-permeable contact lenses for correction of visual acuity and astigmatism. For advanced keratoconus, scleral lenses often are prescribed. These large-diameter, gas-permeable lenses are designed to rest on the sclera and arch over the entire cornea.9 Alternatively, corneal collagen cross-linking is a newer technique that utilizes riboflavin and UVA irradiation to strengthen the corneal tissue. It has proven to be safe and effective in slowing or stopping the progression of keratoconus, particularly when treated at the early stage, and received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2016.9

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a well-known complication of AD and can lead to irreversible ocular hypertension and optic nerve damage. Corticosteroid use is a major risk factor for glaucoma, and the rise in IOP is thought to be due to increased aqueous outflow resistance.14

Multiple case reports have linked glaucoma to long-term use of potent topical corticosteroids in the facial and palpebral regions, which has been attributed to direct steroid contact and absorption by ocular tissues, as glaucoma rarely occurs with topical steroid application elsewhere on the body.15-17 Systemic steroids (ie, prednisolone) taken for more than 8 weeks also have been associated with a marked rise in IOP.18

Certain risk factors may predispose a steroid user to increased IOP, including existing open-angle glaucoma, diabetes mellitus, collagen disease, and high myopia.15,19 Steroid responders and younger individuals also demonstrate increased sensitivity to steroids.20

Given that glaucoma often is asymptomatic until advanced stages, early detection is the key for proper intervention. Periodic glaucoma screening by an ophthalmologist would be appropriate for known steroid responders, as well as patients with a prolonged history of topical steroid application in the palpebral region and systemic steroid use, family history of glaucoma, or known ocular pathology.21 Furthermore, patients with concurrent glaucoma and AD should be jointly managed by dermatology and ophthalmology, and systemic and topical corticosteroid use should be minimized in favor of alterative agents such as calcineurin inhibitors.22

In addition to steroid-induced glaucoma, intrinsic atopic glaucoma recently has been proposed as a clinical entity and is characterized by increased inflammatory cytokines—IL-8 and CCL2—in the aqueous humor and abnormal accumulation of fibers in corneoscleral meshwork.23

Cataracts

Cataracts are estimated to affect 8% to 25% of patients with AD.21,24 Unlike age-related cataracts, cataracts associated with AD are observed in adolescents and young adults in addition to the older population. The progression of lenticular opacity can rapidly occur and has been reported to coincide with AD flares.25,26

Patients with AD typically present with anterior or posterior subcapsular cataracts instead of nuclear and cortical cataracts, which are more common in the general population.27,28 Anterior subcapsular cataracts are more specific to AD, whereas posterior subcapsular cataracts are associated with both prolonged corticosteroid use and AD.26 Children generally are more sensitive to steroids than adults and may develop cataracts more rapidly and at lower concentrations.29

The pathophysiology of cataract formation and progression in the context of AD is multifactorial. Cataract patients with AD have compromised blood-retinal barrier integrity as well as increased oxidative damage in the lens.30,31 Genetics and blunt trauma from eye rubbing are thought to play a role, and the latter has been associated with faster progression of cataracts.28 In contrast, corticosteroid-induced cataracts likely are caused by transcriptional changes and disrupted osmotic balance in the lens fibers, which can lead to fiber rupture and lens opacification.26,32 Systemic corticosteroids show the strongest association with cataract development, but inhaled and topical steroids also have been implicated.26

Although cataracts can be surgically corrected, prevention is critical. Patients with early-onset periorbital AD, prolonged use of topical or systemic corticosteroids, and family history of cataracts should be routinely screened. Anterior and posterior subcapsular cataracts are diagnosed with red reflex examinations that can be readily performed by the primary care physician or ophthalmologist.33 Atopic dermatitis patients with cataracts should be advised to use calcineurin inhibitors and alternative treatments in place of corticosteroids.

Retinal Detachment

Retinal detachment (RD) is a serious complication of AD that can present in individuals younger than 35 years. The incidence of RD in patients with AD has been estimated to be 4% to 8%.34 Retinal detachment manifests with visual disturbances such as flashing lights, shadows, visual field defect, and blurring of vision, but also may occur in the absence of vision changes.35,36

Across multiple case series, patients who developed RD were consistently found to have AD in the facial or periorbital region and a history of chronic eye rubbing. Multiple patients also presented with concurrent proliferative vitreoretinopathy, lens subluxation, and/or cataracts.35,37 The mechanism for RD has been attributed to ocular contusion from vigorous eye rubbing, as fundus findings between traumatic and AD-associated RD are similarly characterized by tractional breaks in the retina at vitreous base borders.37

Avoidance of eye rubbing and optimized treatment of facial AD may help prevent RD in patients with AD. Furthermore, all patients with symptoms of RD should be immediately referred to ophthalmology for surgical repair.

Herpetic Ocular Disease

Ocular herpes simplex virus infections cause ocular pain and are associated with notable visual morbidity, as recurrences can result in irreversible corneal scarring and neovascularization. Two retrospective case-control studies independently reported that individuals with a history of AD are at greater risk for herpetic ocular disease compared to age-matched controls.38,39 Furthermore, atopic disease is associated with higher recurrence rates and slower regeneration of the corneal epithelium.40

These findings suggest that AD patients with a history of recurrent herpetic ocular diseases should be closely monitored and treated with antiviral prophylaxis and/or topical corticosteroids, depending on the type of keratitis (epithelial or stromal).40 Furthermore, active ocular herpetic infections warrant urgent referral to an ophthalmologist.

Dupilumab-Associated Ocular Complications

Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, is the first biologic therapy to be approved for treatment of moderate to severe AD. Prior clinical trials have described a higher incidence of anterior conjunctivitis in dupilumab-treated AD patients (5%–28%) compared to placebo (2%–11%).41 Of note, the incidence may be as high as 70%, as reported in a recent case series.42 Interestingly, independent trials assessing dupilumab treatment in asthma, nasal polyposis, and eosinophilic esophagitis patients did not observe a higher incidence of conjunctivitis in dupilumab-treated patients compared to placebo, suggesting an AD-specific mechanism.43

Prominent features of dupilumab-associated conjunctivitis include hyperemia of the conjunctiva and limbus, in addition to ocular symptoms such as tearing, burning, and bilateral decrease in visual acuity. Marked reduction of conjunctival goblet cells has been reported.44 In addition to conjunctivitis, blepharitis also has been reported during dupilumab treatment.45

Standardized treatment guidelines for dupilumab-associated ocular complications have not yet been established. Surprisingly, antihistamine eye drops appear to be inefficacious in the treatment of dupilumab-associated conjunctivitis.41 However, the condition has been successfully managed with topical steroids (fluorometholone ophthalmic suspension 0.1%) and tacrolimus ointment 0.03%.41 Lifitegrast, an anti-inflammatory agent approved for chronic dry eye, also has been suggested as a treatment option for patients refractory to topical steroids.45 Alternatively, cessation of dupilumab could be considered in AD patients who experience severe ocular complications. Atopic dermatitis patients taking dupilumab who have any concerning signs for ocular complications should be referred to an ophthalmologist for further diagnosis and management.

Conclusion

Practicing dermatologists likely will encounter patients with concurrent AD and ocular complications. Although eye examinations are not routinely performed in the care of AD patients, dermatologists can proactively inquire about ocular symptoms and monitor patients longitudinally. Early diagnosis and treatment of these ocular conditions can prevent vision loss in these patients. Furthermore, symptomatic control of AD and careful consideration of the side-effect profiles of medications can potentially reduce the incidence of ocular complications in individuals with AD.

Patients with visual concerns or risk factors, such as a history of vigorous eye rubbing or chronic corticosteroid use, should be jointly managed with an ophthalmologist for optimized care. Moreover, acute exacerbations of ocular symptoms and visual deterioration warrant urgent referral to ophthalmology.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition with a lifetime prevalence of 15% to 20% in industrialized countries.1 It affects both children and adults and is predominantly characterized by a waxing and waning course of eczematous skin lesions and pruritus. In recent years, there is increasing recognition that AD can present with extracutaneous findings. Large-scale epidemiologic studies have reported a notably higher prevalence of ophthalmic complications in the AD population compared to the general population, in a severity-dependent manner.2,3 Potential complications include blepharitis, keratoconjunctivitis, keratoconus, glaucoma, cataracts, retinal detachment, ophthalmic herpes simplex virus infections, and dupilumab-associated ocular complications.

The etiology of each ocular complication in the context of AD is complex and likely multifactorial. Intrinsic immune dysregulation, physical trauma from eye rubbing, AD medication side effects, and genetics all have been speculated to play a role.2 Some of these ocular complications have a chronic course, while others present with sudden onset of symptoms; many of them can result in visual impairment if undiagnosed or left untreated. This article reviews several of the most common ocular comorbidities associated with AD. We discuss the clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and management strategies for each condition.

Blepharitis

Blepharitis, an inflammatory condition of the eyelids, is estimated to affect more than 6% of patients with AD compared to less than 1% of the general population.2 Blepharitis can be classified as anterior or posterior, based on the anatomic location of the affected region relative to the lash margin. Affected individuals may experience pruritus and irritation of the eyelids, tearing, a foreign body or burning sensation, crusting of the eyelids, and photophobia.4 Anterior blepharitis commonly is due to staphylococcal disease, and posterior blepharitis is secondary to structural changes and obstruction of meibomian gland orifices.

Although the pathophysiology is not well defined, xerosis in atopic patients is accompanied by barrier disruption and transepidermal water loss, which promote eyelid skin inflammation.

The mainstay of therapy for atopic blepharitis consists of conventional lid hygiene regimens, such as warm compresses and gentle scrubbing of the lid margins to remove crust and debris, which can be done with nonprescription cleansers, pads, and baby shampoos. Acute exacerbations may require topical antibiotics (ie, erythromycin or bacitracin applied to the lid margins once daily), topical calcineurin inhibitors (ie, cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05%), or low-potency topical corticosteroids (ie, fluorometholone 0.1% or loteprednol etabonate 0.5% ophthalmic suspensions).5 Due to potential side effects of medications, especially topical corticosteroids, patients should be referred to ophthalmologists for definitive diagnosis and treatment.

Keratoconjunctivitis

Atopic keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) is a noninfectious inflammatory condition of the cornea and conjunctiva that occurs in an estimated 25% to 42% of patients with AD.6,7 It frequently presents in late adolescence and has a peak incidence between 30 and 50 years of age.8 The symptoms of AKC include ocular pruritus, redness, ropy mucoid discharge, burning discomfort, photophobia, and blurring of vision. Corneal involvement can progress to corneal neovascularization and punctate or macroepithelial erosions and ulcerations, which increase the risk for corneal scarring and visual impairment.7

Keratoconjunctivitis is a complex inflammatory disease characterized by infiltration of the conjunctival epithelium by eosinophils, mast cells, and lymphocytes. On examination, patients frequently are found to have concurrent AD of the periorbital skin as well as papillary hypertrophy of the tarsal conjunctiva with accompanying fibrosis, which can lead to entropion (turning inward of the lid margins and lashes) in severe cases.7 Ophthalmic evaluation is strongly recommended for patients with AKC to control symptoms, to limit exacerbations, and to prevent sight-threatening inflammation leading to vision loss. Treatment can be challenging given the chronicity of the condition and may require multiple treatment arms. Conservative measures include cool compresses and treatment with ophthalmic eye drops containing antihistamines (ie, ketotifen 0.025% [available over-the-counter]) and mast cell stabilizers (ie, olopatadine ophthalmic solution 0.1%).8 Atopic keratoconjunctivitis exacerbations may require short-term use of topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors, or systemic equivalents for refractory cases.6 Long-term maintenance therapy typically consists of proper eye hygiene and steroid-sparing agents that reduce ocular inflammation, such as topical cyclosporine and tacrolimus, neither of which are associated with increased intraocular pressure (IOP)(Figure 1).8 Cornea disease resulting from chronic conjunctival/lid microtrauma can be managed with soft or scleral contact lenses.

Keratoconus

Keratoconus is a noninflammatory ocular disorder characterized by progressive thinning and conelike protrusion of the cornea. The corneal topographic changes result in high irregular astigmatism and reduced visual acuity, which can manifest as image blurring or distortion (Figure 2).2,9 Multiple case series and controlled studies have reported a positive association between keratoconus and a history of atopic disease.10,11

The precise etiology of keratoconus in the context of AD is unclear and likely is multifactorial. Habitual eye rubbing from periocular pruritus and discomfort has been reported to be a notable contributor to keratoconus.12 In addition, intrinsic inflammation and imbalance of cytokines and proteases also may contribute to development of keratoconus.13

Keratoconus is a progressive condition that can severely impact vision, making it critical to diagnose patients before irreversible vision loss occurs. Individuals with risk factors, such as AD of the eyelids, history of eye rubbing, or family history of keratoconus, should be advised to receive routine vision screening for worsening astigmatism, especially during the first few decades of life when keratoconus progresses rapidly.

The conservative management for early keratoconus includes glasses and gas-permeable contact lenses for correction of visual acuity and astigmatism. For advanced keratoconus, scleral lenses often are prescribed. These large-diameter, gas-permeable lenses are designed to rest on the sclera and arch over the entire cornea.9 Alternatively, corneal collagen cross-linking is a newer technique that utilizes riboflavin and UVA irradiation to strengthen the corneal tissue. It has proven to be safe and effective in slowing or stopping the progression of keratoconus, particularly when treated at the early stage, and received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2016.9

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a well-known complication of AD and can lead to irreversible ocular hypertension and optic nerve damage. Corticosteroid use is a major risk factor for glaucoma, and the rise in IOP is thought to be due to increased aqueous outflow resistance.14

Multiple case reports have linked glaucoma to long-term use of potent topical corticosteroids in the facial and palpebral regions, which has been attributed to direct steroid contact and absorption by ocular tissues, as glaucoma rarely occurs with topical steroid application elsewhere on the body.15-17 Systemic steroids (ie, prednisolone) taken for more than 8 weeks also have been associated with a marked rise in IOP.18

Certain risk factors may predispose a steroid user to increased IOP, including existing open-angle glaucoma, diabetes mellitus, collagen disease, and high myopia.15,19 Steroid responders and younger individuals also demonstrate increased sensitivity to steroids.20

Given that glaucoma often is asymptomatic until advanced stages, early detection is the key for proper intervention. Periodic glaucoma screening by an ophthalmologist would be appropriate for known steroid responders, as well as patients with a prolonged history of topical steroid application in the palpebral region and systemic steroid use, family history of glaucoma, or known ocular pathology.21 Furthermore, patients with concurrent glaucoma and AD should be jointly managed by dermatology and ophthalmology, and systemic and topical corticosteroid use should be minimized in favor of alterative agents such as calcineurin inhibitors.22

In addition to steroid-induced glaucoma, intrinsic atopic glaucoma recently has been proposed as a clinical entity and is characterized by increased inflammatory cytokines—IL-8 and CCL2—in the aqueous humor and abnormal accumulation of fibers in corneoscleral meshwork.23

Cataracts

Cataracts are estimated to affect 8% to 25% of patients with AD.21,24 Unlike age-related cataracts, cataracts associated with AD are observed in adolescents and young adults in addition to the older population. The progression of lenticular opacity can rapidly occur and has been reported to coincide with AD flares.25,26

Patients with AD typically present with anterior or posterior subcapsular cataracts instead of nuclear and cortical cataracts, which are more common in the general population.27,28 Anterior subcapsular cataracts are more specific to AD, whereas posterior subcapsular cataracts are associated with both prolonged corticosteroid use and AD.26 Children generally are more sensitive to steroids than adults and may develop cataracts more rapidly and at lower concentrations.29

The pathophysiology of cataract formation and progression in the context of AD is multifactorial. Cataract patients with AD have compromised blood-retinal barrier integrity as well as increased oxidative damage in the lens.30,31 Genetics and blunt trauma from eye rubbing are thought to play a role, and the latter has been associated with faster progression of cataracts.28 In contrast, corticosteroid-induced cataracts likely are caused by transcriptional changes and disrupted osmotic balance in the lens fibers, which can lead to fiber rupture and lens opacification.26,32 Systemic corticosteroids show the strongest association with cataract development, but inhaled and topical steroids also have been implicated.26

Although cataracts can be surgically corrected, prevention is critical. Patients with early-onset periorbital AD, prolonged use of topical or systemic corticosteroids, and family history of cataracts should be routinely screened. Anterior and posterior subcapsular cataracts are diagnosed with red reflex examinations that can be readily performed by the primary care physician or ophthalmologist.33 Atopic dermatitis patients with cataracts should be advised to use calcineurin inhibitors and alternative treatments in place of corticosteroids.

Retinal Detachment

Retinal detachment (RD) is a serious complication of AD that can present in individuals younger than 35 years. The incidence of RD in patients with AD has been estimated to be 4% to 8%.34 Retinal detachment manifests with visual disturbances such as flashing lights, shadows, visual field defect, and blurring of vision, but also may occur in the absence of vision changes.35,36

Across multiple case series, patients who developed RD were consistently found to have AD in the facial or periorbital region and a history of chronic eye rubbing. Multiple patients also presented with concurrent proliferative vitreoretinopathy, lens subluxation, and/or cataracts.35,37 The mechanism for RD has been attributed to ocular contusion from vigorous eye rubbing, as fundus findings between traumatic and AD-associated RD are similarly characterized by tractional breaks in the retina at vitreous base borders.37

Avoidance of eye rubbing and optimized treatment of facial AD may help prevent RD in patients with AD. Furthermore, all patients with symptoms of RD should be immediately referred to ophthalmology for surgical repair.

Herpetic Ocular Disease

Ocular herpes simplex virus infections cause ocular pain and are associated with notable visual morbidity, as recurrences can result in irreversible corneal scarring and neovascularization. Two retrospective case-control studies independently reported that individuals with a history of AD are at greater risk for herpetic ocular disease compared to age-matched controls.38,39 Furthermore, atopic disease is associated with higher recurrence rates and slower regeneration of the corneal epithelium.40

These findings suggest that AD patients with a history of recurrent herpetic ocular diseases should be closely monitored and treated with antiviral prophylaxis and/or topical corticosteroids, depending on the type of keratitis (epithelial or stromal).40 Furthermore, active ocular herpetic infections warrant urgent referral to an ophthalmologist.

Dupilumab-Associated Ocular Complications

Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, is the first biologic therapy to be approved for treatment of moderate to severe AD. Prior clinical trials have described a higher incidence of anterior conjunctivitis in dupilumab-treated AD patients (5%–28%) compared to placebo (2%–11%).41 Of note, the incidence may be as high as 70%, as reported in a recent case series.42 Interestingly, independent trials assessing dupilumab treatment in asthma, nasal polyposis, and eosinophilic esophagitis patients did not observe a higher incidence of conjunctivitis in dupilumab-treated patients compared to placebo, suggesting an AD-specific mechanism.43

Prominent features of dupilumab-associated conjunctivitis include hyperemia of the conjunctiva and limbus, in addition to ocular symptoms such as tearing, burning, and bilateral decrease in visual acuity. Marked reduction of conjunctival goblet cells has been reported.44 In addition to conjunctivitis, blepharitis also has been reported during dupilumab treatment.45

Standardized treatment guidelines for dupilumab-associated ocular complications have not yet been established. Surprisingly, antihistamine eye drops appear to be inefficacious in the treatment of dupilumab-associated conjunctivitis.41 However, the condition has been successfully managed with topical steroids (fluorometholone ophthalmic suspension 0.1%) and tacrolimus ointment 0.03%.41 Lifitegrast, an anti-inflammatory agent approved for chronic dry eye, also has been suggested as a treatment option for patients refractory to topical steroids.45 Alternatively, cessation of dupilumab could be considered in AD patients who experience severe ocular complications. Atopic dermatitis patients taking dupilumab who have any concerning signs for ocular complications should be referred to an ophthalmologist for further diagnosis and management.

Conclusion

Practicing dermatologists likely will encounter patients with concurrent AD and ocular complications. Although eye examinations are not routinely performed in the care of AD patients, dermatologists can proactively inquire about ocular symptoms and monitor patients longitudinally. Early diagnosis and treatment of these ocular conditions can prevent vision loss in these patients. Furthermore, symptomatic control of AD and careful consideration of the side-effect profiles of medications can potentially reduce the incidence of ocular complications in individuals with AD.

Patients with visual concerns or risk factors, such as a history of vigorous eye rubbing or chronic corticosteroid use, should be jointly managed with an ophthalmologist for optimized care. Moreover, acute exacerbations of ocular symptoms and visual deterioration warrant urgent referral to ophthalmology.

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1.

- Govind K, Whang K, Khanna R, et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with increased prevalence of multiple ocular comorbidities. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:298-299.

- Thyssen JP, Toft PB, Halling-Overgaard AS, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and risk of selected ocular disease in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:280-286.e281.

- Putnam CM. Diagnosis and management of blepharitis: an optometrist’s perspective. Clin Optom (Auckl). 2016;8:71-78.

- Amescua G, Akpek EK, Farid M, et al. Blepharitis Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:P56-P93.

- Bielory B, Bielory L. Atopic dermatitis and keratoconjunctivitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010;30:323-336.

- Guglielmetti S, Dart JK, Calder V. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:478-485.

- Chen JJ, Applebaum DS, Sun GS, et al. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:569-575.

- Andreanos KD, Hashemi K, Petrelli M, et al. Keratoconus treatment algorithm. Ophthalmol Ther. 2017;6:245-262.

- Rahi A, Davies P, Ruben M, et al. Keratoconus and coexisting atopic disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1977;61:761-764.

- Gasset AR, Hinson WA, Frias JL. Keratoconus and atopic diseases. Ann Ophthalmol. 1978;10:991-994.

- Bawazeer AM, Hodge WG, Lorimer B. Atopy and keratoconus: a multivariate analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:834-836.

- Galvis V, Sherwin T, Tello A, et al. Keratoconus: an inflammatory disorder? Eye (Lond). 2015;29:843-859.

- Clark AF, Wordinger RJ. The role of steroids in outflow resistance. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:752-759.

- Daniel BS, Orchard D. Ocular side-effects of topical corticosteroids: what a dermatologist needs to know. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:164-169.

- Garrott HM, Walland MJ. Glaucoma from topical corticosteroids to the eyelids. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;32:224-226.

- Aggarwal RK, Potamitis T, Chong NH, et al. Extensive visual loss with topical facial steroids. Eye (Lond). 1993;7(pt 5):664-666.

- Mandapati JS, Metta AK. Intraocular pressure variation in patients on long-term corticosteroids. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2011;2:67-69.

- Jones R 3rd, Rhee DJ. Corticosteroid-induced ocular hypertension and glaucoma: a brief review and update of the literature. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:163-167.

- Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Yasuoka N, Ueta M, et al. Influence of topical steroids on intraocular pressure in patients with atopic dermatitis. Allergol Int. 2018;67:388-391.

- Bercovitch L. Screening for ocular complications in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:588-589.

- Abramovits W, Hung P, Tong KB. Efficacy and economics of topical calcineurin inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:213-222.

- Takakuwa K, Hamanaka T, Mori K, et al. Atopic glaucoma: clinical and pathophysiological analysis. J Glaucoma. 2015;24:662-668.

- Haeck IM, Rouwen TJ, Timmer-de Mik L, et al. Topical corticosteroids in atopic dermatitis and the risk of glaucoma and cataracts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:275-281.

- Amemiya T, Matsuda H, Uehara M. Ocular findings in atopic dermatitis with special reference to the clinical features of atopic cataract. Ophthalmologica. 1980;180:129-132.

- Tatham A. Atopic dermatitis, cutaneous steroids and cataracts in children: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:124.

- Chew M, Chiang PP, Zheng Y, et al. The impact of cataract, cataract types, and cataract grades on vision-specific functioning using Rasch analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:29-38.

- Nagaki Y, Hayasaka S, Kadoi C. Cataract progression in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25:96-99.

- Kaye LD, Kalenak JW, Price RL, et al. Ocular implications of long-term prednisone therapy in children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1993;30:142-144.

- Matsuo T, Saito H, Matsuo N. Cataract and aqueous flare levels in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:36-39.

- Namazi MR, Handjani F, Amirahmadi M. Increased oxidative activity from hydrogen peroxide may be the cause of the predisposition to cataracts among patients with atopic dermatitis. Med Hypotheses. 2006;66:863-864.

- James ER. The etiology of steroid cataract. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2007;23:403-420.

- Lambert SR, Teng JMC. Assessing whether the cataracts associated with atopic dermatitis are associated with steroids or inflammatory factors. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:918-919.

- Sasoh M, Mizutani H, Matsubara H, et al. Incidence of retinal detachment associated with atopic dermatitis in Japan: review of cases from 1992 to 2011. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:1129-1134.

- Yoneda K, Okamoto H, Wada Y, et al. Atopic retinal detachment. report of four cases and a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:586-591.

- Gnana Jothi V, McGimpsey S, Sharkey JA, et al. Retinal detachment repair and cataract surgery in patients with atopic dermatitis. Eye (Lond). 2017;31:1296-1301.

- Oka C, Ideta H, Nagasaki H, et al. Retinal detachment with atopic dermatitis similar to traumatic retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1050-1054.

- Prabriputaloong T, Margolis TP, Lietman TM, et al. Atopic disease and herpes simplex eye disease: a population-based case-control study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:745-749.

- Borkar DS, Gonzales JA, Tham VM, et al. Association between atopy and herpetic eye disease: results from the pacific ocular inflammation study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:326-331.

- Rezende RA, Hammersmith K, Bisol T, et al. Comparative study of ocular herpes simplex virus in patients with and without self-reported atopy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:1120-1125.

- Wollenberg A, Ariens L, Thurau S, et al. Conjunctivitis occurring in atopic dermatitis patients treated with dupilumab-clinical characteristics and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1778-1780.e1.

- Ivert LU, Wahlgren CF, Ivert L, et al. Eye complications during dupilumab treatment for severe atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:375-378.

- Akinlade B, Guttman-Yassky E, de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Conjunctivitis in dupilumab clinical trials [published online March 9, 2019]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.17869.

- Bakker DS, Ariens LFM, van Luijk C, et al. Goblet cell scarcity and conjunctival inflammation during treatment with dupilumab in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1248-1249.

- Zirwas MJ, Wulff K, Beckman K. Lifitegrast add-on treatment for dupilumab-induced ocular surface disease (DIOSD): a novel case report. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:34-36.

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1.

- Govind K, Whang K, Khanna R, et al. Atopic dermatitis is associated with increased prevalence of multiple ocular comorbidities. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:298-299.

- Thyssen JP, Toft PB, Halling-Overgaard AS, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and risk of selected ocular disease in adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:280-286.e281.

- Putnam CM. Diagnosis and management of blepharitis: an optometrist’s perspective. Clin Optom (Auckl). 2016;8:71-78.

- Amescua G, Akpek EK, Farid M, et al. Blepharitis Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology. 2019;126:P56-P93.

- Bielory B, Bielory L. Atopic dermatitis and keratoconjunctivitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010;30:323-336.

- Guglielmetti S, Dart JK, Calder V. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:478-485.

- Chen JJ, Applebaum DS, Sun GS, et al. Atopic keratoconjunctivitis: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:569-575.

- Andreanos KD, Hashemi K, Petrelli M, et al. Keratoconus treatment algorithm. Ophthalmol Ther. 2017;6:245-262.

- Rahi A, Davies P, Ruben M, et al. Keratoconus and coexisting atopic disease. Br J Ophthalmol. 1977;61:761-764.

- Gasset AR, Hinson WA, Frias JL. Keratoconus and atopic diseases. Ann Ophthalmol. 1978;10:991-994.

- Bawazeer AM, Hodge WG, Lorimer B. Atopy and keratoconus: a multivariate analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:834-836.

- Galvis V, Sherwin T, Tello A, et al. Keratoconus: an inflammatory disorder? Eye (Lond). 2015;29:843-859.

- Clark AF, Wordinger RJ. The role of steroids in outflow resistance. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:752-759.

- Daniel BS, Orchard D. Ocular side-effects of topical corticosteroids: what a dermatologist needs to know. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:164-169.

- Garrott HM, Walland MJ. Glaucoma from topical corticosteroids to the eyelids. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;32:224-226.

- Aggarwal RK, Potamitis T, Chong NH, et al. Extensive visual loss with topical facial steroids. Eye (Lond). 1993;7(pt 5):664-666.

- Mandapati JS, Metta AK. Intraocular pressure variation in patients on long-term corticosteroids. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2011;2:67-69.

- Jones R 3rd, Rhee DJ. Corticosteroid-induced ocular hypertension and glaucoma: a brief review and update of the literature. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:163-167.

- Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Yasuoka N, Ueta M, et al. Influence of topical steroids on intraocular pressure in patients with atopic dermatitis. Allergol Int. 2018;67:388-391.

- Bercovitch L. Screening for ocular complications in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:588-589.

- Abramovits W, Hung P, Tong KB. Efficacy and economics of topical calcineurin inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:213-222.

- Takakuwa K, Hamanaka T, Mori K, et al. Atopic glaucoma: clinical and pathophysiological analysis. J Glaucoma. 2015;24:662-668.

- Haeck IM, Rouwen TJ, Timmer-de Mik L, et al. Topical corticosteroids in atopic dermatitis and the risk of glaucoma and cataracts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:275-281.

- Amemiya T, Matsuda H, Uehara M. Ocular findings in atopic dermatitis with special reference to the clinical features of atopic cataract. Ophthalmologica. 1980;180:129-132.

- Tatham A. Atopic dermatitis, cutaneous steroids and cataracts in children: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:124.

- Chew M, Chiang PP, Zheng Y, et al. The impact of cataract, cataract types, and cataract grades on vision-specific functioning using Rasch analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154:29-38.

- Nagaki Y, Hayasaka S, Kadoi C. Cataract progression in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25:96-99.

- Kaye LD, Kalenak JW, Price RL, et al. Ocular implications of long-term prednisone therapy in children. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1993;30:142-144.

- Matsuo T, Saito H, Matsuo N. Cataract and aqueous flare levels in patients with atopic dermatitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:36-39.

- Namazi MR, Handjani F, Amirahmadi M. Increased oxidative activity from hydrogen peroxide may be the cause of the predisposition to cataracts among patients with atopic dermatitis. Med Hypotheses. 2006;66:863-864.

- James ER. The etiology of steroid cataract. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2007;23:403-420.

- Lambert SR, Teng JMC. Assessing whether the cataracts associated with atopic dermatitis are associated with steroids or inflammatory factors. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136:918-919.

- Sasoh M, Mizutani H, Matsubara H, et al. Incidence of retinal detachment associated with atopic dermatitis in Japan: review of cases from 1992 to 2011. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:1129-1134.

- Yoneda K, Okamoto H, Wada Y, et al. Atopic retinal detachment. report of four cases and a review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:586-591.

- Gnana Jothi V, McGimpsey S, Sharkey JA, et al. Retinal detachment repair and cataract surgery in patients with atopic dermatitis. Eye (Lond). 2017;31:1296-1301.

- Oka C, Ideta H, Nagasaki H, et al. Retinal detachment with atopic dermatitis similar to traumatic retinal detachment. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1050-1054.

- Prabriputaloong T, Margolis TP, Lietman TM, et al. Atopic disease and herpes simplex eye disease: a population-based case-control study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:745-749.

- Borkar DS, Gonzales JA, Tham VM, et al. Association between atopy and herpetic eye disease: results from the pacific ocular inflammation study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:326-331.

- Rezende RA, Hammersmith K, Bisol T, et al. Comparative study of ocular herpes simplex virus in patients with and without self-reported atopy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:1120-1125.

- Wollenberg A, Ariens L, Thurau S, et al. Conjunctivitis occurring in atopic dermatitis patients treated with dupilumab-clinical characteristics and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1778-1780.e1.

- Ivert LU, Wahlgren CF, Ivert L, et al. Eye complications during dupilumab treatment for severe atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:375-378.

- Akinlade B, Guttman-Yassky E, de Bruin-Weller M, et al. Conjunctivitis in dupilumab clinical trials [published online March 9, 2019]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.17869.

- Bakker DS, Ariens LFM, van Luijk C, et al. Goblet cell scarcity and conjunctival inflammation during treatment with dupilumab in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1248-1249.

- Zirwas MJ, Wulff K, Beckman K. Lifitegrast add-on treatment for dupilumab-induced ocular surface disease (DIOSD): a novel case report. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:34-36.

Practice Points

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) is associated with various ocular comorbidities that can result in permanent vision loss if untreated.

- Timely recognition of ocular complications in AD patients is critical, and dermatologists should proactively inquire about ocular symptoms in the review of systems.

- Patients with ocular symptoms should be jointly managed with ophthalmology.