User login

Blips on Lips

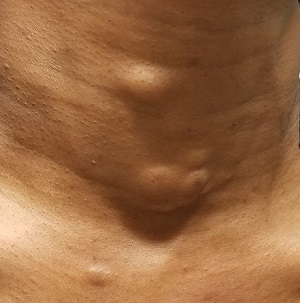

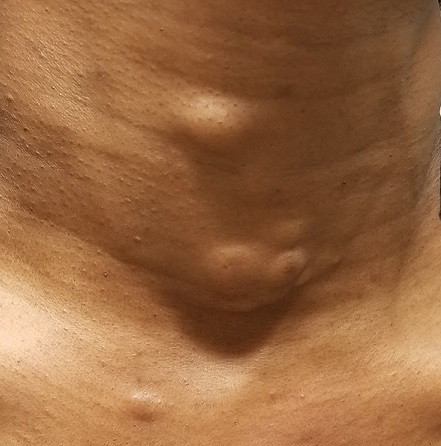

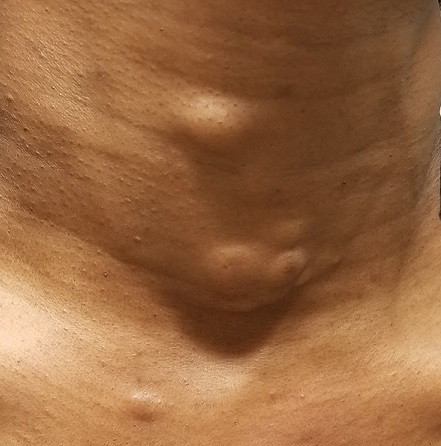

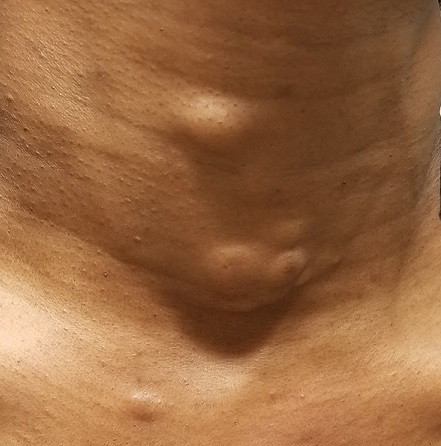

A 39-year-old woman presents with red vascular streaks on her upper and lower lips. They have slowly multiplied and become more prominent since she first noticed them several years ago. Although the lesions are asymptomatic, their effect on her appearance bothers the patient.

Her primary care provider tried to resolve the problem with cryotherapy. But the treatment attempt was unsuccessful.

During history-taking, the patient divulges other existing health problems. She has been diagnosed with Raynaud syndrome, which flares several times a year, especially in cold weather or times of exceptional stress. She also has permanent thickening of the skin on her distal fingers, a result of sudden-onset swelling of all 10 fingers several years ago.

She denies any problems with eating, such as heartburn or difficulty swallowing. She also denies any respiratory problems or chronic fatigue.

EXAMINATION

Seven very slender telangiectasias, most aligned vertically, are seen on the upper and lower vermillion surfaces. They range from a pinpoint to 6 mm in length. There are no similar lesions are on the rest of the oral mucosae, the face, or the chest.

The patient’s fingers, from the metacarpals to the tips, are decidedly edematous and firm but not tender. Several fingertips are scarred from past Raynaud episodes.

The patient looks her stated age and is in no distress.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This patient almost certainly has CREST syndrome, a limited form of systemic sclerosis (or scleroderma). Both represent an autoimmune process in which antibodies attack cell DNA and centromeres (a component of the cell nucleus).

CREST can be difficult to diagnose because it can involve diverse organ systems. The name of the syndrome is an acronym for the symptoms it causes:

Calcinosis is a deposition of calcium triggered by inflammation. It manifests as small subcutaneous nodules, which are usually felt on the hands or seen on radiographs of the hands.

Raynaud syndrome causes intense vasoconstriction of blood vessels, usually in fingertips or toes, which first turn white, then red. The phenomenon is accompanied by pain and can be triggered by cold or stress.

Esophageal dysmotility occurs when atrophy and/or fibrosis of the esophageal lining leads to difficulty swallowing food.

Sclerodactyly is the term for tightening and thickening of the skin on the hands and fingers.

Telangiectasias are dilated capillaries that can worsen with time; they are common on lips, mucosal surfaces, the face, and the chest. They are often associated with vascular disease (eg, pulmonary hypertension).

Any of these signs can be seen with full-blown systemic sclerosis, but CREST is usually much less aggressive and seldom leads to renal or congestive heart failure—the 2 leading causes of death in systemic sclerosis.

Diagnosis is based on recognition of the clinical signs and symptoms, as well as blood work (ie, antinuclear antibody and anti-centromere antibody tests). A skin biopsy is often performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Since there is no effective treatment for the overarching disease, the specific components of CREST are treated separately. For this patient, her lip lesions were treated with light electrodessication. Another option would have been laser treatment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- CREST syndrome, a limited form of systemic sclerosis, is a rare autoimmune condition caused by antibodies to cellular DNA and nuclear centromeres.

- CREST is an acronym for the symptomatic manifestations of the condition: calcinosis, Raynaud disease, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasias.

- Diagnosis is based on connecting the clinical dots and taking a thorough history, as well as lab results (for antinuclear antibodies and anti-centromere antibodies) and a skin biopsy.

- CREST is usually treated symptomatically, one system at a time, since no definitive treatment exists for the disease itself.

A 39-year-old woman presents with red vascular streaks on her upper and lower lips. They have slowly multiplied and become more prominent since she first noticed them several years ago. Although the lesions are asymptomatic, their effect on her appearance bothers the patient.

Her primary care provider tried to resolve the problem with cryotherapy. But the treatment attempt was unsuccessful.

During history-taking, the patient divulges other existing health problems. She has been diagnosed with Raynaud syndrome, which flares several times a year, especially in cold weather or times of exceptional stress. She also has permanent thickening of the skin on her distal fingers, a result of sudden-onset swelling of all 10 fingers several years ago.

She denies any problems with eating, such as heartburn or difficulty swallowing. She also denies any respiratory problems or chronic fatigue.

EXAMINATION

Seven very slender telangiectasias, most aligned vertically, are seen on the upper and lower vermillion surfaces. They range from a pinpoint to 6 mm in length. There are no similar lesions are on the rest of the oral mucosae, the face, or the chest.

The patient’s fingers, from the metacarpals to the tips, are decidedly edematous and firm but not tender. Several fingertips are scarred from past Raynaud episodes.

The patient looks her stated age and is in no distress.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This patient almost certainly has CREST syndrome, a limited form of systemic sclerosis (or scleroderma). Both represent an autoimmune process in which antibodies attack cell DNA and centromeres (a component of the cell nucleus).

CREST can be difficult to diagnose because it can involve diverse organ systems. The name of the syndrome is an acronym for the symptoms it causes:

Calcinosis is a deposition of calcium triggered by inflammation. It manifests as small subcutaneous nodules, which are usually felt on the hands or seen on radiographs of the hands.

Raynaud syndrome causes intense vasoconstriction of blood vessels, usually in fingertips or toes, which first turn white, then red. The phenomenon is accompanied by pain and can be triggered by cold or stress.

Esophageal dysmotility occurs when atrophy and/or fibrosis of the esophageal lining leads to difficulty swallowing food.

Sclerodactyly is the term for tightening and thickening of the skin on the hands and fingers.

Telangiectasias are dilated capillaries that can worsen with time; they are common on lips, mucosal surfaces, the face, and the chest. They are often associated with vascular disease (eg, pulmonary hypertension).

Any of these signs can be seen with full-blown systemic sclerosis, but CREST is usually much less aggressive and seldom leads to renal or congestive heart failure—the 2 leading causes of death in systemic sclerosis.

Diagnosis is based on recognition of the clinical signs and symptoms, as well as blood work (ie, antinuclear antibody and anti-centromere antibody tests). A skin biopsy is often performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Since there is no effective treatment for the overarching disease, the specific components of CREST are treated separately. For this patient, her lip lesions were treated with light electrodessication. Another option would have been laser treatment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- CREST syndrome, a limited form of systemic sclerosis, is a rare autoimmune condition caused by antibodies to cellular DNA and nuclear centromeres.

- CREST is an acronym for the symptomatic manifestations of the condition: calcinosis, Raynaud disease, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasias.

- Diagnosis is based on connecting the clinical dots and taking a thorough history, as well as lab results (for antinuclear antibodies and anti-centromere antibodies) and a skin biopsy.

- CREST is usually treated symptomatically, one system at a time, since no definitive treatment exists for the disease itself.

A 39-year-old woman presents with red vascular streaks on her upper and lower lips. They have slowly multiplied and become more prominent since she first noticed them several years ago. Although the lesions are asymptomatic, their effect on her appearance bothers the patient.

Her primary care provider tried to resolve the problem with cryotherapy. But the treatment attempt was unsuccessful.

During history-taking, the patient divulges other existing health problems. She has been diagnosed with Raynaud syndrome, which flares several times a year, especially in cold weather or times of exceptional stress. She also has permanent thickening of the skin on her distal fingers, a result of sudden-onset swelling of all 10 fingers several years ago.

She denies any problems with eating, such as heartburn or difficulty swallowing. She also denies any respiratory problems or chronic fatigue.

EXAMINATION

Seven very slender telangiectasias, most aligned vertically, are seen on the upper and lower vermillion surfaces. They range from a pinpoint to 6 mm in length. There are no similar lesions are on the rest of the oral mucosae, the face, or the chest.

The patient’s fingers, from the metacarpals to the tips, are decidedly edematous and firm but not tender. Several fingertips are scarred from past Raynaud episodes.

The patient looks her stated age and is in no distress.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This patient almost certainly has CREST syndrome, a limited form of systemic sclerosis (or scleroderma). Both represent an autoimmune process in which antibodies attack cell DNA and centromeres (a component of the cell nucleus).

CREST can be difficult to diagnose because it can involve diverse organ systems. The name of the syndrome is an acronym for the symptoms it causes:

Calcinosis is a deposition of calcium triggered by inflammation. It manifests as small subcutaneous nodules, which are usually felt on the hands or seen on radiographs of the hands.

Raynaud syndrome causes intense vasoconstriction of blood vessels, usually in fingertips or toes, which first turn white, then red. The phenomenon is accompanied by pain and can be triggered by cold or stress.

Esophageal dysmotility occurs when atrophy and/or fibrosis of the esophageal lining leads to difficulty swallowing food.

Sclerodactyly is the term for tightening and thickening of the skin on the hands and fingers.

Telangiectasias are dilated capillaries that can worsen with time; they are common on lips, mucosal surfaces, the face, and the chest. They are often associated with vascular disease (eg, pulmonary hypertension).

Any of these signs can be seen with full-blown systemic sclerosis, but CREST is usually much less aggressive and seldom leads to renal or congestive heart failure—the 2 leading causes of death in systemic sclerosis.

Diagnosis is based on recognition of the clinical signs and symptoms, as well as blood work (ie, antinuclear antibody and anti-centromere antibody tests). A skin biopsy is often performed to confirm the diagnosis.

Since there is no effective treatment for the overarching disease, the specific components of CREST are treated separately. For this patient, her lip lesions were treated with light electrodessication. Another option would have been laser treatment.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- CREST syndrome, a limited form of systemic sclerosis, is a rare autoimmune condition caused by antibodies to cellular DNA and nuclear centromeres.

- CREST is an acronym for the symptomatic manifestations of the condition: calcinosis, Raynaud disease, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasias.

- Diagnosis is based on connecting the clinical dots and taking a thorough history, as well as lab results (for antinuclear antibodies and anti-centromere antibodies) and a skin biopsy.

- CREST is usually treated symptomatically, one system at a time, since no definitive treatment exists for the disease itself.

When Life’s an Itch

A 34-year-old woman self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of a very itchy rash that manifested 2 weeks ago on her right arm. She immediately went to an urgent care clinic, where she was diagnosed with shingles and prescribed valacyclovir. This diagnosis was upsetting to the patient, as she was advised to avoid contact with her newborn niece for at least 2 weeks.

Despite the prescribed medication, however, the rash began to pop up in other areas, including her left arm, chest, and face. Through all of this, the patient felt fine: no fever, myalgia, or malaise.

Her husband suggested she seek an appointment with dermatology, which was expedited by a phone call from her primary care provider.

EXAMINATION

The patient is afebrile and in no acute distress. She is, however, quite upset with the widespread collections of vesicles on mildly erythematous bases, many in a linear configuration. In several areas, there is ecchymosis secondary to scratching.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Poison ivy, or Rhus dermatitis, is one of the most common dermatologic problems seen in medicine—and yet, its various presentations can, as this case illustrates, be quite confusing. Even when it is recognized, treatment is far from satisfactory (but more on that later). Furthermore, there is a lot of misinformation about everything from the appearance of the offending plant to the condition’s “contagious” nature.

From a broader perspective, poison ivy is becoming more prevalent and its effects more pronounced as cities expand into formerly open country. The Rhus plant family (Toxicodendron radicans and others) thrives on our increasing levels of CO2, effectively making the “poisonous” resin in the stems, leaves, and berries more potent.

With repeated exposure, the vast majority of the population will develop an allergy to this resin, known as urushiol, which can persist even on long-dead plants, vines, and leaves. (It does take repeated exposure to develop the requisite T-cell population, which is why many children are immune to it.) The urushiol does not serve as a protective substance for the plant; rather, it helps the plant retain water. In fact, many animals feed on the plant with impunity.

Virtually all members of the poison ivy family display “leaves of three” emerging from a single stem, with each triplet alternating first on one side of the branch and then on the other. Several varieties of the plant flourish over vast areas of the world, but in the United States, east of the Rockies, Toxicodendron radicans is the dominant member of the family. It can grow as a low vine, a shrub, or a climbing vine, each with a distinct appearance aside from the leaves, which are almond-shaped, smooth, and usually shiny with smooth surfaces. Most mature leaves will have a single notch, sometimes called a “thumb,” on otherwise smooth, nonserrated edges. In the summer, tiny white and yellow berries begin to grow.

The climbing vines of older plants can reach heights of 10 meters or more. These vines can reach a thickness of 3 inches and often appear “furry,” with tiny rootlets covering their surfaces. Plants this large can produce leaves 12 to 14 inches long.

Clinically, the appearance of linear pink to red pruritic vesicular streaks typify this contact dermatitis, which can immediately follow exposure or take days to appear. Said exposure can be direct or via pets, tools, or aerosols (eg, from neighbors mowing their lawns). Besides avoidance of the great outdoors, washing thoroughly immediately after exposure makes sense (but many are unaware that they’ve been exposed until it’s too late).

Poison ivy is not contagious, though the general public firmly believes otherwise. Left untreated, it clears within 2 weeks (except in unusual cases). For those who cannot bear to wait, treatment is problematic, to say the least. OTC products, such as calamine lotion, do nothing for the itching but may help with blistering. Topical or systemic steroids reduce itching somewhat. Antihistamines are useless, since this condition does not involve histamine release.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Poison ivy (Rhus dermatitis) is quite common and becoming more so due to encroaching civilization and increasing CO2 levels.

- “Leaves of three, let it be” is still good advice, because the poison ivy plant Toxicodendron radicans manifests with three almond-shaped, shiny, green leaves grouped in threes.

- Urushiol is the name of the oily resin found in the plant’s stem, leaves, and berries, and is the trigger resulting in contact dermatitis.

- Poison ivy is not contagious and typically clears in 2 weeks.

A 34-year-old woman self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of a very itchy rash that manifested 2 weeks ago on her right arm. She immediately went to an urgent care clinic, where she was diagnosed with shingles and prescribed valacyclovir. This diagnosis was upsetting to the patient, as she was advised to avoid contact with her newborn niece for at least 2 weeks.

Despite the prescribed medication, however, the rash began to pop up in other areas, including her left arm, chest, and face. Through all of this, the patient felt fine: no fever, myalgia, or malaise.

Her husband suggested she seek an appointment with dermatology, which was expedited by a phone call from her primary care provider.

EXAMINATION

The patient is afebrile and in no acute distress. She is, however, quite upset with the widespread collections of vesicles on mildly erythematous bases, many in a linear configuration. In several areas, there is ecchymosis secondary to scratching.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Poison ivy, or Rhus dermatitis, is one of the most common dermatologic problems seen in medicine—and yet, its various presentations can, as this case illustrates, be quite confusing. Even when it is recognized, treatment is far from satisfactory (but more on that later). Furthermore, there is a lot of misinformation about everything from the appearance of the offending plant to the condition’s “contagious” nature.

From a broader perspective, poison ivy is becoming more prevalent and its effects more pronounced as cities expand into formerly open country. The Rhus plant family (Toxicodendron radicans and others) thrives on our increasing levels of CO2, effectively making the “poisonous” resin in the stems, leaves, and berries more potent.

With repeated exposure, the vast majority of the population will develop an allergy to this resin, known as urushiol, which can persist even on long-dead plants, vines, and leaves. (It does take repeated exposure to develop the requisite T-cell population, which is why many children are immune to it.) The urushiol does not serve as a protective substance for the plant; rather, it helps the plant retain water. In fact, many animals feed on the plant with impunity.

Virtually all members of the poison ivy family display “leaves of three” emerging from a single stem, with each triplet alternating first on one side of the branch and then on the other. Several varieties of the plant flourish over vast areas of the world, but in the United States, east of the Rockies, Toxicodendron radicans is the dominant member of the family. It can grow as a low vine, a shrub, or a climbing vine, each with a distinct appearance aside from the leaves, which are almond-shaped, smooth, and usually shiny with smooth surfaces. Most mature leaves will have a single notch, sometimes called a “thumb,” on otherwise smooth, nonserrated edges. In the summer, tiny white and yellow berries begin to grow.

The climbing vines of older plants can reach heights of 10 meters or more. These vines can reach a thickness of 3 inches and often appear “furry,” with tiny rootlets covering their surfaces. Plants this large can produce leaves 12 to 14 inches long.

Clinically, the appearance of linear pink to red pruritic vesicular streaks typify this contact dermatitis, which can immediately follow exposure or take days to appear. Said exposure can be direct or via pets, tools, or aerosols (eg, from neighbors mowing their lawns). Besides avoidance of the great outdoors, washing thoroughly immediately after exposure makes sense (but many are unaware that they’ve been exposed until it’s too late).

Poison ivy is not contagious, though the general public firmly believes otherwise. Left untreated, it clears within 2 weeks (except in unusual cases). For those who cannot bear to wait, treatment is problematic, to say the least. OTC products, such as calamine lotion, do nothing for the itching but may help with blistering. Topical or systemic steroids reduce itching somewhat. Antihistamines are useless, since this condition does not involve histamine release.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Poison ivy (Rhus dermatitis) is quite common and becoming more so due to encroaching civilization and increasing CO2 levels.

- “Leaves of three, let it be” is still good advice, because the poison ivy plant Toxicodendron radicans manifests with three almond-shaped, shiny, green leaves grouped in threes.

- Urushiol is the name of the oily resin found in the plant’s stem, leaves, and berries, and is the trigger resulting in contact dermatitis.

- Poison ivy is not contagious and typically clears in 2 weeks.

A 34-year-old woman self-refers to dermatology for evaluation of a very itchy rash that manifested 2 weeks ago on her right arm. She immediately went to an urgent care clinic, where she was diagnosed with shingles and prescribed valacyclovir. This diagnosis was upsetting to the patient, as she was advised to avoid contact with her newborn niece for at least 2 weeks.

Despite the prescribed medication, however, the rash began to pop up in other areas, including her left arm, chest, and face. Through all of this, the patient felt fine: no fever, myalgia, or malaise.

Her husband suggested she seek an appointment with dermatology, which was expedited by a phone call from her primary care provider.

EXAMINATION

The patient is afebrile and in no acute distress. She is, however, quite upset with the widespread collections of vesicles on mildly erythematous bases, many in a linear configuration. In several areas, there is ecchymosis secondary to scratching.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Poison ivy, or Rhus dermatitis, is one of the most common dermatologic problems seen in medicine—and yet, its various presentations can, as this case illustrates, be quite confusing. Even when it is recognized, treatment is far from satisfactory (but more on that later). Furthermore, there is a lot of misinformation about everything from the appearance of the offending plant to the condition’s “contagious” nature.

From a broader perspective, poison ivy is becoming more prevalent and its effects more pronounced as cities expand into formerly open country. The Rhus plant family (Toxicodendron radicans and others) thrives on our increasing levels of CO2, effectively making the “poisonous” resin in the stems, leaves, and berries more potent.

With repeated exposure, the vast majority of the population will develop an allergy to this resin, known as urushiol, which can persist even on long-dead plants, vines, and leaves. (It does take repeated exposure to develop the requisite T-cell population, which is why many children are immune to it.) The urushiol does not serve as a protective substance for the plant; rather, it helps the plant retain water. In fact, many animals feed on the plant with impunity.

Virtually all members of the poison ivy family display “leaves of three” emerging from a single stem, with each triplet alternating first on one side of the branch and then on the other. Several varieties of the plant flourish over vast areas of the world, but in the United States, east of the Rockies, Toxicodendron radicans is the dominant member of the family. It can grow as a low vine, a shrub, or a climbing vine, each with a distinct appearance aside from the leaves, which are almond-shaped, smooth, and usually shiny with smooth surfaces. Most mature leaves will have a single notch, sometimes called a “thumb,” on otherwise smooth, nonserrated edges. In the summer, tiny white and yellow berries begin to grow.

The climbing vines of older plants can reach heights of 10 meters or more. These vines can reach a thickness of 3 inches and often appear “furry,” with tiny rootlets covering their surfaces. Plants this large can produce leaves 12 to 14 inches long.

Clinically, the appearance of linear pink to red pruritic vesicular streaks typify this contact dermatitis, which can immediately follow exposure or take days to appear. Said exposure can be direct or via pets, tools, or aerosols (eg, from neighbors mowing their lawns). Besides avoidance of the great outdoors, washing thoroughly immediately after exposure makes sense (but many are unaware that they’ve been exposed until it’s too late).

Poison ivy is not contagious, though the general public firmly believes otherwise. Left untreated, it clears within 2 weeks (except in unusual cases). For those who cannot bear to wait, treatment is problematic, to say the least. OTC products, such as calamine lotion, do nothing for the itching but may help with blistering. Topical or systemic steroids reduce itching somewhat. Antihistamines are useless, since this condition does not involve histamine release.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Poison ivy (Rhus dermatitis) is quite common and becoming more so due to encroaching civilization and increasing CO2 levels.

- “Leaves of three, let it be” is still good advice, because the poison ivy plant Toxicodendron radicans manifests with three almond-shaped, shiny, green leaves grouped in threes.

- Urushiol is the name of the oily resin found in the plant’s stem, leaves, and berries, and is the trigger resulting in contact dermatitis.

- Poison ivy is not contagious and typically clears in 2 weeks.

An Atypical Problem for Atopical People

At age 1, a girl developed a blistery rash on the left side of her face. It was soon followed by a low-grade fever and modest malaise. All symptoms cleared within 2 weeks. Now, at age 4, she continues to experience similar, periodic outbreaks in the same location.

She has already been seen by various providers, including a dermatologist, and received several different diagnoses. The dermatologist scraped the rash and determined it to be a fungal infection. However, the recommended topical antifungal cream had no effect. At least 3 other providers (all nondermatology) called it cellulitis and treated with oral antibiotics, but these attempts also failed.

EXAMINATION

There are no active lesions at the time of this initial examination and no palpable adenopathy in the region. There is a large area of erythema in a macular pattern over the right cheek. No scarring is visible.

The patient later returns when a new outbreak occurs. This time, there are distinct blisters and reactive adenopathy in the adjacent nodal areas.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Results of a viral culture indicate herpes simplex.

The recurrence of persistent, vesicular rashes in the same location signifies a herpetic nature. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is easier to diagnose in an adult patient, due to the ability to elicit a reliable history of premonitory symptoms. Small children have difficulty verbalizing the distinction between a tingle, an itch, and mild pain, which herald the onset of an HSV outbreak.

An episode of HSV can be triggered by anything that raises the body temperature (eg, stress, sickness, or sun exposure). Also important to note, these kinds of outbreaks can occur almost anywhere on the body, including ears, fingers, nipples, noses, and eyelids.

In my experience, most patients with longstanding herpes outbreaks are atopic (ie, allergy prone) or come from families in which atopy is common. Atopic patients are well known to be susceptible to all manner of skin infections, but most especially to herpes. It’s as if their immune systems overreact to pollen, mold, dust, and other allergens, while viral, fungal, and bacterial antigens fly under their immune radar.

In this case, the child was treated with valacyclovir on a chronic, as opposed to episodic, basis. With a bit of luck, this treatment will help to diminish HSV attacks as she matures.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Anything that raises body temperature (sun, colds, or even stress) can trigger an episode of herpes simplex virus (HSV).

- Vesicular rashes that recur in the same location should be presumed herpetic, until proven otherwise. Usually, viral cultures aren’t necessary since the differential is so narrow.

- Atopy can predispose one to all manner of skin infections, including viral, fungal, and bacterial.

- Treatment of chronic HSV can be episodic or preventive, depending on the frequency and severity of attacks.

At age 1, a girl developed a blistery rash on the left side of her face. It was soon followed by a low-grade fever and modest malaise. All symptoms cleared within 2 weeks. Now, at age 4, she continues to experience similar, periodic outbreaks in the same location.

She has already been seen by various providers, including a dermatologist, and received several different diagnoses. The dermatologist scraped the rash and determined it to be a fungal infection. However, the recommended topical antifungal cream had no effect. At least 3 other providers (all nondermatology) called it cellulitis and treated with oral antibiotics, but these attempts also failed.

EXAMINATION

There are no active lesions at the time of this initial examination and no palpable adenopathy in the region. There is a large area of erythema in a macular pattern over the right cheek. No scarring is visible.

The patient later returns when a new outbreak occurs. This time, there are distinct blisters and reactive adenopathy in the adjacent nodal areas.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Results of a viral culture indicate herpes simplex.

The recurrence of persistent, vesicular rashes in the same location signifies a herpetic nature. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is easier to diagnose in an adult patient, due to the ability to elicit a reliable history of premonitory symptoms. Small children have difficulty verbalizing the distinction between a tingle, an itch, and mild pain, which herald the onset of an HSV outbreak.

An episode of HSV can be triggered by anything that raises the body temperature (eg, stress, sickness, or sun exposure). Also important to note, these kinds of outbreaks can occur almost anywhere on the body, including ears, fingers, nipples, noses, and eyelids.

In my experience, most patients with longstanding herpes outbreaks are atopic (ie, allergy prone) or come from families in which atopy is common. Atopic patients are well known to be susceptible to all manner of skin infections, but most especially to herpes. It’s as if their immune systems overreact to pollen, mold, dust, and other allergens, while viral, fungal, and bacterial antigens fly under their immune radar.

In this case, the child was treated with valacyclovir on a chronic, as opposed to episodic, basis. With a bit of luck, this treatment will help to diminish HSV attacks as she matures.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Anything that raises body temperature (sun, colds, or even stress) can trigger an episode of herpes simplex virus (HSV).

- Vesicular rashes that recur in the same location should be presumed herpetic, until proven otherwise. Usually, viral cultures aren’t necessary since the differential is so narrow.

- Atopy can predispose one to all manner of skin infections, including viral, fungal, and bacterial.

- Treatment of chronic HSV can be episodic or preventive, depending on the frequency and severity of attacks.

At age 1, a girl developed a blistery rash on the left side of her face. It was soon followed by a low-grade fever and modest malaise. All symptoms cleared within 2 weeks. Now, at age 4, she continues to experience similar, periodic outbreaks in the same location.

She has already been seen by various providers, including a dermatologist, and received several different diagnoses. The dermatologist scraped the rash and determined it to be a fungal infection. However, the recommended topical antifungal cream had no effect. At least 3 other providers (all nondermatology) called it cellulitis and treated with oral antibiotics, but these attempts also failed.

EXAMINATION

There are no active lesions at the time of this initial examination and no palpable adenopathy in the region. There is a large area of erythema in a macular pattern over the right cheek. No scarring is visible.

The patient later returns when a new outbreak occurs. This time, there are distinct blisters and reactive adenopathy in the adjacent nodal areas.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Results of a viral culture indicate herpes simplex.

The recurrence of persistent, vesicular rashes in the same location signifies a herpetic nature. Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is easier to diagnose in an adult patient, due to the ability to elicit a reliable history of premonitory symptoms. Small children have difficulty verbalizing the distinction between a tingle, an itch, and mild pain, which herald the onset of an HSV outbreak.

An episode of HSV can be triggered by anything that raises the body temperature (eg, stress, sickness, or sun exposure). Also important to note, these kinds of outbreaks can occur almost anywhere on the body, including ears, fingers, nipples, noses, and eyelids.

In my experience, most patients with longstanding herpes outbreaks are atopic (ie, allergy prone) or come from families in which atopy is common. Atopic patients are well known to be susceptible to all manner of skin infections, but most especially to herpes. It’s as if their immune systems overreact to pollen, mold, dust, and other allergens, while viral, fungal, and bacterial antigens fly under their immune radar.

In this case, the child was treated with valacyclovir on a chronic, as opposed to episodic, basis. With a bit of luck, this treatment will help to diminish HSV attacks as she matures.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Anything that raises body temperature (sun, colds, or even stress) can trigger an episode of herpes simplex virus (HSV).

- Vesicular rashes that recur in the same location should be presumed herpetic, until proven otherwise. Usually, viral cultures aren’t necessary since the differential is so narrow.

- Atopy can predispose one to all manner of skin infections, including viral, fungal, and bacterial.

- Treatment of chronic HSV can be episodic or preventive, depending on the frequency and severity of attacks.

Boiling Points

This 37-year-old woman began developing “boils” under both arms at age 12. Over the years, the lesions have become more numerous and bothersome. They are often painful and large and are capable of bursting on their own, releasing purulent material. Occasionally, similar lesions appear under her breasts and in the groin. The problem seems to wax and wane with her menstrual cycle. Family history reveals that both her mother and one of her sisters have had the same problem, again starting around the time of menarche.

Whenever the patient seeks medical care, usually at the emergency department, the diagnosis is always the same: boils. Normally, the prescribed treatment includes incision, drainage, and packing of the largest lesions, followed by 2 weeks of oral antibiotics. While the problem generally improves after treatment, it invariably returns.

Her health is decent overall. However, she has been overweight for years and has been smoking since she was 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s left axilla shows ropy, hypertrophic scars, many comedones, and several fluctuant cystic subcutaneous masses. There is no frank erythema, although the patient indicates there often is.

No such changes are seen on examination of her right axilla. Instead, there is a slender 12-cm linear scar running across the axillary fold. Upon questioning, the patient reports that several years ago, a surgeon removed three-fourths of the skin and subcutaneous tissue from this area. This procedure cured the “boils” on her right arm, but it also left her with chronic lymphedema in that extremity.

Other intertriginous areas are free of significant changes.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

In the US, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) affects 1% to 4% of the population and about 4 times as many females as males. But as this case demonstrates, it is consistently misidentified as “boils” or “staph infection” by providers unfamiliar with the correct diagnosis.

HS involves hair follicles in intertriginous areas of the body that are rich with apocrine glands (eg, armpit, groin). The condition, initially known as acne inversa, was first described in 1833 by Dr. Alfred Velpeau, a French surgeon. Despite some minor similarities, HS is not actually a form of acne, nor is it an infection. About one-third of HS patients inherit the condition, and generally, onset occurs post puberty, suggesting a hormonal component.

With HS, the hair follicle and associated apocrine gland fail to function normally. As sweat accumulates in subcutaneous tissue, it creates a chronic inflammatory reaction manifesting with large comedones, cysts, and abscesses. Eventually, it can result in ropy, hypertrophic scars on the surface and deep tracts connecting multiple lesions. HS is classified as mild (stage 1), moderate (stage 2), or severe (stage 3) using the Hurley staging system.

HS is notoriously difficult to cure, but the anti-inflammatory effects of some antibiotics (eg, minocycline, doxycycline) can offer some relief, as can anti-androgens (eg, spironolactone). The use of isotretinoin has yielded disappointing results. For small lesions, intralesional injection of glucocorticoids can be useful for short-term relief of pain and swelling.

The most encouraging recent development in HS treatment is the approval for the use of adalimumab (Humira) in severe cases that have failed to respond to other modalities. Even with use of this biologic, decent control is probably the best outcome—and that’s at an annual cost of $50,000, plus the patient’s exposure to potentially serious adverse effects due to immunosuppression.

Another approach is surgical, with all its attendant risks, as this patient experienced in her right axilla. Simple incision and drainage offer little beyond temporary relief of pain.

Environmental factors should not be overlooked; obesity and smoking have both been linked to HS in multiple studies.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Hidradenitis suppurativa, also known as acne inversa, results from malfunction of the hair follicle and associated apocrine glands in intertriginous areas.

- HS can range from mild (with minor pustules and sparse comedones) to and severe (diffuse disease, affecting multiple areas with heavy ropy scarring, large painful abscesses, and connecting tracts).

- HS affects approximately 4 times as many females as males, almost all with post-pubertal onset—strongly suggestive of a hormonal component.

- Treatment is problematic, although the recent approval of adalimumab for use in HS is proving to be helpful, if not curative. Some oral antibiotics and anti-androgens have shown mixed results.

This 37-year-old woman began developing “boils” under both arms at age 12. Over the years, the lesions have become more numerous and bothersome. They are often painful and large and are capable of bursting on their own, releasing purulent material. Occasionally, similar lesions appear under her breasts and in the groin. The problem seems to wax and wane with her menstrual cycle. Family history reveals that both her mother and one of her sisters have had the same problem, again starting around the time of menarche.

Whenever the patient seeks medical care, usually at the emergency department, the diagnosis is always the same: boils. Normally, the prescribed treatment includes incision, drainage, and packing of the largest lesions, followed by 2 weeks of oral antibiotics. While the problem generally improves after treatment, it invariably returns.

Her health is decent overall. However, she has been overweight for years and has been smoking since she was 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s left axilla shows ropy, hypertrophic scars, many comedones, and several fluctuant cystic subcutaneous masses. There is no frank erythema, although the patient indicates there often is.

No such changes are seen on examination of her right axilla. Instead, there is a slender 12-cm linear scar running across the axillary fold. Upon questioning, the patient reports that several years ago, a surgeon removed three-fourths of the skin and subcutaneous tissue from this area. This procedure cured the “boils” on her right arm, but it also left her with chronic lymphedema in that extremity.

Other intertriginous areas are free of significant changes.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

In the US, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) affects 1% to 4% of the population and about 4 times as many females as males. But as this case demonstrates, it is consistently misidentified as “boils” or “staph infection” by providers unfamiliar with the correct diagnosis.

HS involves hair follicles in intertriginous areas of the body that are rich with apocrine glands (eg, armpit, groin). The condition, initially known as acne inversa, was first described in 1833 by Dr. Alfred Velpeau, a French surgeon. Despite some minor similarities, HS is not actually a form of acne, nor is it an infection. About one-third of HS patients inherit the condition, and generally, onset occurs post puberty, suggesting a hormonal component.

With HS, the hair follicle and associated apocrine gland fail to function normally. As sweat accumulates in subcutaneous tissue, it creates a chronic inflammatory reaction manifesting with large comedones, cysts, and abscesses. Eventually, it can result in ropy, hypertrophic scars on the surface and deep tracts connecting multiple lesions. HS is classified as mild (stage 1), moderate (stage 2), or severe (stage 3) using the Hurley staging system.

HS is notoriously difficult to cure, but the anti-inflammatory effects of some antibiotics (eg, minocycline, doxycycline) can offer some relief, as can anti-androgens (eg, spironolactone). The use of isotretinoin has yielded disappointing results. For small lesions, intralesional injection of glucocorticoids can be useful for short-term relief of pain and swelling.

The most encouraging recent development in HS treatment is the approval for the use of adalimumab (Humira) in severe cases that have failed to respond to other modalities. Even with use of this biologic, decent control is probably the best outcome—and that’s at an annual cost of $50,000, plus the patient’s exposure to potentially serious adverse effects due to immunosuppression.

Another approach is surgical, with all its attendant risks, as this patient experienced in her right axilla. Simple incision and drainage offer little beyond temporary relief of pain.

Environmental factors should not be overlooked; obesity and smoking have both been linked to HS in multiple studies.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Hidradenitis suppurativa, also known as acne inversa, results from malfunction of the hair follicle and associated apocrine glands in intertriginous areas.

- HS can range from mild (with minor pustules and sparse comedones) to and severe (diffuse disease, affecting multiple areas with heavy ropy scarring, large painful abscesses, and connecting tracts).

- HS affects approximately 4 times as many females as males, almost all with post-pubertal onset—strongly suggestive of a hormonal component.

- Treatment is problematic, although the recent approval of adalimumab for use in HS is proving to be helpful, if not curative. Some oral antibiotics and anti-androgens have shown mixed results.

This 37-year-old woman began developing “boils” under both arms at age 12. Over the years, the lesions have become more numerous and bothersome. They are often painful and large and are capable of bursting on their own, releasing purulent material. Occasionally, similar lesions appear under her breasts and in the groin. The problem seems to wax and wane with her menstrual cycle. Family history reveals that both her mother and one of her sisters have had the same problem, again starting around the time of menarche.

Whenever the patient seeks medical care, usually at the emergency department, the diagnosis is always the same: boils. Normally, the prescribed treatment includes incision, drainage, and packing of the largest lesions, followed by 2 weeks of oral antibiotics. While the problem generally improves after treatment, it invariably returns.

Her health is decent overall. However, she has been overweight for years and has been smoking since she was 14.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s left axilla shows ropy, hypertrophic scars, many comedones, and several fluctuant cystic subcutaneous masses. There is no frank erythema, although the patient indicates there often is.

No such changes are seen on examination of her right axilla. Instead, there is a slender 12-cm linear scar running across the axillary fold. Upon questioning, the patient reports that several years ago, a surgeon removed three-fourths of the skin and subcutaneous tissue from this area. This procedure cured the “boils” on her right arm, but it also left her with chronic lymphedema in that extremity.

Other intertriginous areas are free of significant changes.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

In the US, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) affects 1% to 4% of the population and about 4 times as many females as males. But as this case demonstrates, it is consistently misidentified as “boils” or “staph infection” by providers unfamiliar with the correct diagnosis.

HS involves hair follicles in intertriginous areas of the body that are rich with apocrine glands (eg, armpit, groin). The condition, initially known as acne inversa, was first described in 1833 by Dr. Alfred Velpeau, a French surgeon. Despite some minor similarities, HS is not actually a form of acne, nor is it an infection. About one-third of HS patients inherit the condition, and generally, onset occurs post puberty, suggesting a hormonal component.

With HS, the hair follicle and associated apocrine gland fail to function normally. As sweat accumulates in subcutaneous tissue, it creates a chronic inflammatory reaction manifesting with large comedones, cysts, and abscesses. Eventually, it can result in ropy, hypertrophic scars on the surface and deep tracts connecting multiple lesions. HS is classified as mild (stage 1), moderate (stage 2), or severe (stage 3) using the Hurley staging system.

HS is notoriously difficult to cure, but the anti-inflammatory effects of some antibiotics (eg, minocycline, doxycycline) can offer some relief, as can anti-androgens (eg, spironolactone). The use of isotretinoin has yielded disappointing results. For small lesions, intralesional injection of glucocorticoids can be useful for short-term relief of pain and swelling.

The most encouraging recent development in HS treatment is the approval for the use of adalimumab (Humira) in severe cases that have failed to respond to other modalities. Even with use of this biologic, decent control is probably the best outcome—and that’s at an annual cost of $50,000, plus the patient’s exposure to potentially serious adverse effects due to immunosuppression.

Another approach is surgical, with all its attendant risks, as this patient experienced in her right axilla. Simple incision and drainage offer little beyond temporary relief of pain.

Environmental factors should not be overlooked; obesity and smoking have both been linked to HS in multiple studies.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Hidradenitis suppurativa, also known as acne inversa, results from malfunction of the hair follicle and associated apocrine glands in intertriginous areas.

- HS can range from mild (with minor pustules and sparse comedones) to and severe (diffuse disease, affecting multiple areas with heavy ropy scarring, large painful abscesses, and connecting tracts).

- HS affects approximately 4 times as many females as males, almost all with post-pubertal onset—strongly suggestive of a hormonal component.

- Treatment is problematic, although the recent approval of adalimumab for use in HS is proving to be helpful, if not curative. Some oral antibiotics and anti-androgens have shown mixed results.

“Cupping” With Pain

A 30-year-old woman with a history of chronic overexposure to UV light presents to dermatology for a routine skin exam. The patient has a history of poor toleration to UV light, especially as a child, but participated in regular tanning as a teen. However, she stopped tanning when her sister developed a melanoma.

Additionally, the patient has been experiencing upper back pain, for which she has seen a variety of providers. Most recently, she consulted a naturopath, who recommended cupping therapy. Although the patient believes the therapy is alleviating her pain, she is distressed by the subsequent formation of large blemishes on her back and asks about possible treatment.

EXAMINATION

There are 10 large round patches, each measuring 7 cm in diameter, on the patient’s back. These patches consist of multiple petechiae and brown hyperpigmentation. On palpation, there is no surface disturbance or tenderness. The discoloration is nonblanchable. The size, shape, and configuration of the lesions is consistent with the patient's description of the cupping procedures she has undergone on several occasions.

Notably, the patient's skin is categorized as type II on the Fitzpatrick scale, with advanced dermatoheliosis.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

"Cupping," as medical therapy, was first described in ancient texts 3000 to 4000 years ago. The application of cups to the patient’s skin was intended to draw out substances (eg, toxins and fluids) inside the body that were believed to cause a variety of ailments. Though its use has long since been discarded in mainstream medicine, it is still used routinely in both Chinese and alternative medicine.

Cupping has been evaluated by numerous medical individuals and organizations, who uniformly dismiss any benefit it might offer, even as a placebo. From a pathophysiologic standpoint, cupping causes localized dilation of blood and lymph vessels, thus creating telangiectasia that, as they resolve, leave behind postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and edema. (Excessive production of telangiectasia might indicate pathologic capillary fragility, possibly secondary to Rumpel-Leede phenomenon.)

The patient's skin type can affect the rate of resolution (longer for those with darker skin, shorter for those with fair skin); there is little we can do to speed up this process. Although the case patient was disappointed with the lack of available treatment for her blemishes, she was insistent about continuing the cupping therapy.

Interestingly, there is a differential diagnosis for such lesions; it includes injury from tennis balls, racquetballs, paintballs, or even baseballs—though the associated lesions are usually solitary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Cupping, as medical therapy, has been around for thousands of years and is still routinely used in both Chinese and alternative medicine.

- The intention of its use is to draw out noxious substances that purportedly cause the patient's complaint—however, according to numerous medical authorities, the practice is totally ineffective.

- The suction effect of cupping induces edema and telangiectasia, which in turn results in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that clears slowly.

- Similar lesions can result from being struck by paintballs, racquetballs, tennis balls, and baseballs.

A 30-year-old woman with a history of chronic overexposure to UV light presents to dermatology for a routine skin exam. The patient has a history of poor toleration to UV light, especially as a child, but participated in regular tanning as a teen. However, she stopped tanning when her sister developed a melanoma.

Additionally, the patient has been experiencing upper back pain, for which she has seen a variety of providers. Most recently, she consulted a naturopath, who recommended cupping therapy. Although the patient believes the therapy is alleviating her pain, she is distressed by the subsequent formation of large blemishes on her back and asks about possible treatment.

EXAMINATION

There are 10 large round patches, each measuring 7 cm in diameter, on the patient’s back. These patches consist of multiple petechiae and brown hyperpigmentation. On palpation, there is no surface disturbance or tenderness. The discoloration is nonblanchable. The size, shape, and configuration of the lesions is consistent with the patient's description of the cupping procedures she has undergone on several occasions.

Notably, the patient's skin is categorized as type II on the Fitzpatrick scale, with advanced dermatoheliosis.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

"Cupping," as medical therapy, was first described in ancient texts 3000 to 4000 years ago. The application of cups to the patient’s skin was intended to draw out substances (eg, toxins and fluids) inside the body that were believed to cause a variety of ailments. Though its use has long since been discarded in mainstream medicine, it is still used routinely in both Chinese and alternative medicine.

Cupping has been evaluated by numerous medical individuals and organizations, who uniformly dismiss any benefit it might offer, even as a placebo. From a pathophysiologic standpoint, cupping causes localized dilation of blood and lymph vessels, thus creating telangiectasia that, as they resolve, leave behind postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and edema. (Excessive production of telangiectasia might indicate pathologic capillary fragility, possibly secondary to Rumpel-Leede phenomenon.)

The patient's skin type can affect the rate of resolution (longer for those with darker skin, shorter for those with fair skin); there is little we can do to speed up this process. Although the case patient was disappointed with the lack of available treatment for her blemishes, she was insistent about continuing the cupping therapy.

Interestingly, there is a differential diagnosis for such lesions; it includes injury from tennis balls, racquetballs, paintballs, or even baseballs—though the associated lesions are usually solitary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Cupping, as medical therapy, has been around for thousands of years and is still routinely used in both Chinese and alternative medicine.

- The intention of its use is to draw out noxious substances that purportedly cause the patient's complaint—however, according to numerous medical authorities, the practice is totally ineffective.

- The suction effect of cupping induces edema and telangiectasia, which in turn results in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that clears slowly.

- Similar lesions can result from being struck by paintballs, racquetballs, tennis balls, and baseballs.

A 30-year-old woman with a history of chronic overexposure to UV light presents to dermatology for a routine skin exam. The patient has a history of poor toleration to UV light, especially as a child, but participated in regular tanning as a teen. However, she stopped tanning when her sister developed a melanoma.

Additionally, the patient has been experiencing upper back pain, for which she has seen a variety of providers. Most recently, she consulted a naturopath, who recommended cupping therapy. Although the patient believes the therapy is alleviating her pain, she is distressed by the subsequent formation of large blemishes on her back and asks about possible treatment.

EXAMINATION

There are 10 large round patches, each measuring 7 cm in diameter, on the patient’s back. These patches consist of multiple petechiae and brown hyperpigmentation. On palpation, there is no surface disturbance or tenderness. The discoloration is nonblanchable. The size, shape, and configuration of the lesions is consistent with the patient's description of the cupping procedures she has undergone on several occasions.

Notably, the patient's skin is categorized as type II on the Fitzpatrick scale, with advanced dermatoheliosis.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

"Cupping," as medical therapy, was first described in ancient texts 3000 to 4000 years ago. The application of cups to the patient’s skin was intended to draw out substances (eg, toxins and fluids) inside the body that were believed to cause a variety of ailments. Though its use has long since been discarded in mainstream medicine, it is still used routinely in both Chinese and alternative medicine.

Cupping has been evaluated by numerous medical individuals and organizations, who uniformly dismiss any benefit it might offer, even as a placebo. From a pathophysiologic standpoint, cupping causes localized dilation of blood and lymph vessels, thus creating telangiectasia that, as they resolve, leave behind postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and edema. (Excessive production of telangiectasia might indicate pathologic capillary fragility, possibly secondary to Rumpel-Leede phenomenon.)

The patient's skin type can affect the rate of resolution (longer for those with darker skin, shorter for those with fair skin); there is little we can do to speed up this process. Although the case patient was disappointed with the lack of available treatment for her blemishes, she was insistent about continuing the cupping therapy.

Interestingly, there is a differential diagnosis for such lesions; it includes injury from tennis balls, racquetballs, paintballs, or even baseballs—though the associated lesions are usually solitary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Cupping, as medical therapy, has been around for thousands of years and is still routinely used in both Chinese and alternative medicine.

- The intention of its use is to draw out noxious substances that purportedly cause the patient's complaint—however, according to numerous medical authorities, the practice is totally ineffective.

- The suction effect of cupping induces edema and telangiectasia, which in turn results in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that clears slowly.

- Similar lesions can result from being struck by paintballs, racquetballs, tennis balls, and baseballs.

Baby’s Rash Causes Family Feud

Since birth, this 5-month-old boy has had a facial rash that comes and goes. At times severe, it is the source of much familial disagreement about its cause: Some say the problem is related to food, while others are sure it represents infection.

Several medications, including triple-antibiotic ointment and nystatin cream, have been tried. None have had much effect.

The child is well in all other respects—gaining weight as expected and experiencing normal growth and development. The rash does not appear to bother him as much as it bothers his family to see.

Further questioning reveals a strong family history of seasonal allergies, eczema, and asthma. Notably, all affected individuals have long since outgrown those problems.

EXAMINATION

The child is in no apparent distress but is noted to have nasal congestion, with continual mouth breathing. Overall, his skin is quite dry and fair.

The rash itself is rather florid, affecting the perioral area and spreading onto the cheeks in a symmetrical configuration. The skin in these areas is focally erythematous, though not swollen. It is also quite scaly in places, giving the appearance of, as his parents note, “chapped” skin. Examination of the diaper area reveals a similar look focally.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case is typical of those seen multiple times daily in primary care and dermatology offices—hardly surprising, since atopic dermatitis (AD) affects about 20% of all newborns in this and other developed countries. In very young children, AD primarily affects the face and diaper area, as well as the trunk. About 50% of affected patients will have cradle cap—as did this child in his first month of life, we subsequently learned.

The tendency to develop AD is inherited. It is not related to food, although children with AD could develop a food allergy. However, it would more likely manifest with gastrointestinal symptoms. Another myth embedded in Western culture is that AD is caused by exposure to a particular laundry detergent.

Rather, this child and others like him have inherited dry, thin, overreactive skin that is bathed early on with nasal secretions, bacteria, and saliva. Later, their eczema will migrate to areas that stay moist, such as the antecubital and popliteal folds, or to the area around the neck, where the itching can be intense—which of course causes the child to scratch, in turn worsening the problem.

Patient/parent education is the key to dealing with AD and can be bolstered by handouts or direction to reliable websites. Besides objectifying the problem, these resources detail its nature and outline the need for daily bathing with mild cleansers, generous application of heavy moisturizers, careful use of topical corticosteroid creams or ointments (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone), and avoidance of woolen clothing or bedding.

Another important component of patient/parent education is the reassurance that eczema will not scar the patient. It does occasionally become severe enough to require a short course of oral antibiotics (eg, cephalexin) or even the use of oral prednisolone. Since AD is not a histamine-driven process, antihistamines are ineffective for eczema.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) is extremely common, affecting 20% of all newborns in developed countries.

- Infantile eczema typically centers on the face, particularly the perioral area.

- Later, it begins to involve the antecubital and popliteal areas, which stay moist a good part of the time.

- Most children outgrow the worst of the problem—and go on to have children who develop it.

Since birth, this 5-month-old boy has had a facial rash that comes and goes. At times severe, it is the source of much familial disagreement about its cause: Some say the problem is related to food, while others are sure it represents infection.

Several medications, including triple-antibiotic ointment and nystatin cream, have been tried. None have had much effect.

The child is well in all other respects—gaining weight as expected and experiencing normal growth and development. The rash does not appear to bother him as much as it bothers his family to see.

Further questioning reveals a strong family history of seasonal allergies, eczema, and asthma. Notably, all affected individuals have long since outgrown those problems.

EXAMINATION

The child is in no apparent distress but is noted to have nasal congestion, with continual mouth breathing. Overall, his skin is quite dry and fair.

The rash itself is rather florid, affecting the perioral area and spreading onto the cheeks in a symmetrical configuration. The skin in these areas is focally erythematous, though not swollen. It is also quite scaly in places, giving the appearance of, as his parents note, “chapped” skin. Examination of the diaper area reveals a similar look focally.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case is typical of those seen multiple times daily in primary care and dermatology offices—hardly surprising, since atopic dermatitis (AD) affects about 20% of all newborns in this and other developed countries. In very young children, AD primarily affects the face and diaper area, as well as the trunk. About 50% of affected patients will have cradle cap—as did this child in his first month of life, we subsequently learned.

The tendency to develop AD is inherited. It is not related to food, although children with AD could develop a food allergy. However, it would more likely manifest with gastrointestinal symptoms. Another myth embedded in Western culture is that AD is caused by exposure to a particular laundry detergent.

Rather, this child and others like him have inherited dry, thin, overreactive skin that is bathed early on with nasal secretions, bacteria, and saliva. Later, their eczema will migrate to areas that stay moist, such as the antecubital and popliteal folds, or to the area around the neck, where the itching can be intense—which of course causes the child to scratch, in turn worsening the problem.

Patient/parent education is the key to dealing with AD and can be bolstered by handouts or direction to reliable websites. Besides objectifying the problem, these resources detail its nature and outline the need for daily bathing with mild cleansers, generous application of heavy moisturizers, careful use of topical corticosteroid creams or ointments (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone), and avoidance of woolen clothing or bedding.

Another important component of patient/parent education is the reassurance that eczema will not scar the patient. It does occasionally become severe enough to require a short course of oral antibiotics (eg, cephalexin) or even the use of oral prednisolone. Since AD is not a histamine-driven process, antihistamines are ineffective for eczema.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) is extremely common, affecting 20% of all newborns in developed countries.

- Infantile eczema typically centers on the face, particularly the perioral area.

- Later, it begins to involve the antecubital and popliteal areas, which stay moist a good part of the time.

- Most children outgrow the worst of the problem—and go on to have children who develop it.

Since birth, this 5-month-old boy has had a facial rash that comes and goes. At times severe, it is the source of much familial disagreement about its cause: Some say the problem is related to food, while others are sure it represents infection.

Several medications, including triple-antibiotic ointment and nystatin cream, have been tried. None have had much effect.

The child is well in all other respects—gaining weight as expected and experiencing normal growth and development. The rash does not appear to bother him as much as it bothers his family to see.

Further questioning reveals a strong family history of seasonal allergies, eczema, and asthma. Notably, all affected individuals have long since outgrown those problems.

EXAMINATION

The child is in no apparent distress but is noted to have nasal congestion, with continual mouth breathing. Overall, his skin is quite dry and fair.

The rash itself is rather florid, affecting the perioral area and spreading onto the cheeks in a symmetrical configuration. The skin in these areas is focally erythematous, though not swollen. It is also quite scaly in places, giving the appearance of, as his parents note, “chapped” skin. Examination of the diaper area reveals a similar look focally.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case is typical of those seen multiple times daily in primary care and dermatology offices—hardly surprising, since atopic dermatitis (AD) affects about 20% of all newborns in this and other developed countries. In very young children, AD primarily affects the face and diaper area, as well as the trunk. About 50% of affected patients will have cradle cap—as did this child in his first month of life, we subsequently learned.

The tendency to develop AD is inherited. It is not related to food, although children with AD could develop a food allergy. However, it would more likely manifest with gastrointestinal symptoms. Another myth embedded in Western culture is that AD is caused by exposure to a particular laundry detergent.

Rather, this child and others like him have inherited dry, thin, overreactive skin that is bathed early on with nasal secretions, bacteria, and saliva. Later, their eczema will migrate to areas that stay moist, such as the antecubital and popliteal folds, or to the area around the neck, where the itching can be intense—which of course causes the child to scratch, in turn worsening the problem.

Patient/parent education is the key to dealing with AD and can be bolstered by handouts or direction to reliable websites. Besides objectifying the problem, these resources detail its nature and outline the need for daily bathing with mild cleansers, generous application of heavy moisturizers, careful use of topical corticosteroid creams or ointments (eg, 2.5% hydrocortisone), and avoidance of woolen clothing or bedding.

Another important component of patient/parent education is the reassurance that eczema will not scar the patient. It does occasionally become severe enough to require a short course of oral antibiotics (eg, cephalexin) or even the use of oral prednisolone. Since AD is not a histamine-driven process, antihistamines are ineffective for eczema.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Atopic dermatitis (AD) is extremely common, affecting 20% of all newborns in developed countries.

- Infantile eczema typically centers on the face, particularly the perioral area.

- Later, it begins to involve the antecubital and popliteal areas, which stay moist a good part of the time.

- Most children outgrow the worst of the problem—and go on to have children who develop it.

Can You Put Your Finger on the Diagnosis?

An 8-year-old boy is brought in for evaluation of a collection of blisters on his finger, near the nail. The problem manifested about 6 days ago. The affected area is tender to touch. The child reportedly feels well, with no fever or malaise.

The patient has an extensive personal and family history of atopy. Since birth, he has had dry, sensitive skin and has experienced episodes of eczema, seasonal allergies, and asthma. Three months ago, he was admitted to the hospital with eczema herpeticum and successfully treated with IV acyclovir.

EXAMINATION

A cluster of vesicles is seen in the lateral perionychial area of the left third finger. Very modest erythema surrounds the vesicles, which contain cloudy yellow fluid suggestive of pus. There is a palpable lymph node in the left epitrochlear area.

The child is afebrile and in no distress. Patches of mild eczema are seen on the extremities and trunk.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The lesion on this child’s finger is a herpetic whitlow. Patients with atopy are often susceptible to all types of skin infections: bacterial, fungal, and viral. In fact, human papillomavirus infection manifesting as multiple warts is not uncommon in this population. Nor is herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, of which this case represents 1 manifestation.

A culture could have been done to confirm the diagnosis, but that would entail opening a vesicle to collect the fluid and then waiting at least 2 weeks for the results. By then, this whitlow would have long since resolved.

As with all HSV infections in the immunocompetent, treatment with acyclovir must be started in the first 2 to 3 days to have any effect—so such treatment in this case would be useless. If the herpetic whitlow were to recur in the same location, prompt treatment could be initiated, which would likely shorten the disease course and reduce symptoms.

Another HSV infection seen almost exclusively in atopic patients is eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This diffuse infection comprises dozens of tiny papulovesicular lesions, mostly concentrated on the face but often spilling down onto the chest. Patients with Darier disease or seborrheic dermatitis can also acquire it.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Patients with atopy, especially children, are susceptible to all kinds of skin infections—fungal, bacterial, and viral.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can appear in almost any location, including on fingers, but can also manifest as diffuse papulovesicular lesions on the face and chest of atopic patients.

- The blisters/vesicles of HSV are often pus-filled and usually provoke regional adenopathy.

- If diagnosed early enough, herpetic whitlows can be successfully treated with oral acyclovir; this doesn’t provide a cure but does stop the particular episode.

An 8-year-old boy is brought in for evaluation of a collection of blisters on his finger, near the nail. The problem manifested about 6 days ago. The affected area is tender to touch. The child reportedly feels well, with no fever or malaise.

The patient has an extensive personal and family history of atopy. Since birth, he has had dry, sensitive skin and has experienced episodes of eczema, seasonal allergies, and asthma. Three months ago, he was admitted to the hospital with eczema herpeticum and successfully treated with IV acyclovir.

EXAMINATION

A cluster of vesicles is seen in the lateral perionychial area of the left third finger. Very modest erythema surrounds the vesicles, which contain cloudy yellow fluid suggestive of pus. There is a palpable lymph node in the left epitrochlear area.

The child is afebrile and in no distress. Patches of mild eczema are seen on the extremities and trunk.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The lesion on this child’s finger is a herpetic whitlow. Patients with atopy are often susceptible to all types of skin infections: bacterial, fungal, and viral. In fact, human papillomavirus infection manifesting as multiple warts is not uncommon in this population. Nor is herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, of which this case represents 1 manifestation.

A culture could have been done to confirm the diagnosis, but that would entail opening a vesicle to collect the fluid and then waiting at least 2 weeks for the results. By then, this whitlow would have long since resolved.

As with all HSV infections in the immunocompetent, treatment with acyclovir must be started in the first 2 to 3 days to have any effect—so such treatment in this case would be useless. If the herpetic whitlow were to recur in the same location, prompt treatment could be initiated, which would likely shorten the disease course and reduce symptoms.

Another HSV infection seen almost exclusively in atopic patients is eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This diffuse infection comprises dozens of tiny papulovesicular lesions, mostly concentrated on the face but often spilling down onto the chest. Patients with Darier disease or seborrheic dermatitis can also acquire it.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Patients with atopy, especially children, are susceptible to all kinds of skin infections—fungal, bacterial, and viral.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can appear in almost any location, including on fingers, but can also manifest as diffuse papulovesicular lesions on the face and chest of atopic patients.

- The blisters/vesicles of HSV are often pus-filled and usually provoke regional adenopathy.

- If diagnosed early enough, herpetic whitlows can be successfully treated with oral acyclovir; this doesn’t provide a cure but does stop the particular episode.

An 8-year-old boy is brought in for evaluation of a collection of blisters on his finger, near the nail. The problem manifested about 6 days ago. The affected area is tender to touch. The child reportedly feels well, with no fever or malaise.

The patient has an extensive personal and family history of atopy. Since birth, he has had dry, sensitive skin and has experienced episodes of eczema, seasonal allergies, and asthma. Three months ago, he was admitted to the hospital with eczema herpeticum and successfully treated with IV acyclovir.

EXAMINATION

A cluster of vesicles is seen in the lateral perionychial area of the left third finger. Very modest erythema surrounds the vesicles, which contain cloudy yellow fluid suggestive of pus. There is a palpable lymph node in the left epitrochlear area.

The child is afebrile and in no distress. Patches of mild eczema are seen on the extremities and trunk.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The lesion on this child’s finger is a herpetic whitlow. Patients with atopy are often susceptible to all types of skin infections: bacterial, fungal, and viral. In fact, human papillomavirus infection manifesting as multiple warts is not uncommon in this population. Nor is herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, of which this case represents 1 manifestation.

A culture could have been done to confirm the diagnosis, but that would entail opening a vesicle to collect the fluid and then waiting at least 2 weeks for the results. By then, this whitlow would have long since resolved.

As with all HSV infections in the immunocompetent, treatment with acyclovir must be started in the first 2 to 3 days to have any effect—so such treatment in this case would be useless. If the herpetic whitlow were to recur in the same location, prompt treatment could be initiated, which would likely shorten the disease course and reduce symptoms.

Another HSV infection seen almost exclusively in atopic patients is eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption). This diffuse infection comprises dozens of tiny papulovesicular lesions, mostly concentrated on the face but often spilling down onto the chest. Patients with Darier disease or seborrheic dermatitis can also acquire it.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Patients with atopy, especially children, are susceptible to all kinds of skin infections—fungal, bacterial, and viral.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV) can appear in almost any location, including on fingers, but can also manifest as diffuse papulovesicular lesions on the face and chest of atopic patients.

- The blisters/vesicles of HSV are often pus-filled and usually provoke regional adenopathy.

- If diagnosed early enough, herpetic whitlows can be successfully treated with oral acyclovir; this doesn’t provide a cure but does stop the particular episode.

She Needs A-cyst-ance