User login

Not the Neck-tar of the Gods

ANSWER

The correct answer is cutaneous sinus tract of odontogenic origin (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

These uncommon lesions are known by several names, including odontogenic fistula. Invariably, they are misdiagnosed as an “infection” and treated with antibiotics, which only calm these lesions until they inevitably return to their pretreatment appearance. Though bacteria (mostly Peptostreptococcus—the anaerobe predominating in the mouth) are involved, this is not an infection as it usually manifests.

The underlying process of this condition is caused by a periapical abscess: as it grows in size and pressure, it enters into the mouth or fistulizes out through the buccal tissue, continuing until it penetrates the skin and begins to release its pustular contents. Eighty percent manifest on the submental or chin area, while 20% tunnel inwards toward the oral cavity.

They initially manifest as papules with a 2-to-3-mm surface that soon drain pus from a central sinus. As this continues, the epithelium responds to the chronic inflammation by forming a mass of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Biopsy would reveal that the mass also shows signs of chronic inflammation. Ordinary bacterial culture often shows nothing because the predominant organism is an anaerobe. At most, one might see a polymicrobial result.

TREATMENT

For affected patients, a dentist can be considered for radiography of the area to confirm the location of the periapical abscess. Then the tooth is usually extracted, resulting in a cure. No further treatment of the sinus tract is necessary because it will essentially disappear over time. The tract does not require excision because it is lined with reactive granulation tissue and not epithelium (as is the case for many other fistular processes).

If the dental exam and radiograph fail to show the expected result, the other diagnoses—thyroglossal duct cyst, branchial cleft cyst, squamous cell carcinoma—would have to be considered.

ANSWER

The correct answer is cutaneous sinus tract of odontogenic origin (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

These uncommon lesions are known by several names, including odontogenic fistula. Invariably, they are misdiagnosed as an “infection” and treated with antibiotics, which only calm these lesions until they inevitably return to their pretreatment appearance. Though bacteria (mostly Peptostreptococcus—the anaerobe predominating in the mouth) are involved, this is not an infection as it usually manifests.

The underlying process of this condition is caused by a periapical abscess: as it grows in size and pressure, it enters into the mouth or fistulizes out through the buccal tissue, continuing until it penetrates the skin and begins to release its pustular contents. Eighty percent manifest on the submental or chin area, while 20% tunnel inwards toward the oral cavity.

They initially manifest as papules with a 2-to-3-mm surface that soon drain pus from a central sinus. As this continues, the epithelium responds to the chronic inflammation by forming a mass of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Biopsy would reveal that the mass also shows signs of chronic inflammation. Ordinary bacterial culture often shows nothing because the predominant organism is an anaerobe. At most, one might see a polymicrobial result.

TREATMENT

For affected patients, a dentist can be considered for radiography of the area to confirm the location of the periapical abscess. Then the tooth is usually extracted, resulting in a cure. No further treatment of the sinus tract is necessary because it will essentially disappear over time. The tract does not require excision because it is lined with reactive granulation tissue and not epithelium (as is the case for many other fistular processes).

If the dental exam and radiograph fail to show the expected result, the other diagnoses—thyroglossal duct cyst, branchial cleft cyst, squamous cell carcinoma—would have to be considered.

ANSWER

The correct answer is cutaneous sinus tract of odontogenic origin (choice “d”).

DISCUSSION

These uncommon lesions are known by several names, including odontogenic fistula. Invariably, they are misdiagnosed as an “infection” and treated with antibiotics, which only calm these lesions until they inevitably return to their pretreatment appearance. Though bacteria (mostly Peptostreptococcus—the anaerobe predominating in the mouth) are involved, this is not an infection as it usually manifests.

The underlying process of this condition is caused by a periapical abscess: as it grows in size and pressure, it enters into the mouth or fistulizes out through the buccal tissue, continuing until it penetrates the skin and begins to release its pustular contents. Eighty percent manifest on the submental or chin area, while 20% tunnel inwards toward the oral cavity.

They initially manifest as papules with a 2-to-3-mm surface that soon drain pus from a central sinus. As this continues, the epithelium responds to the chronic inflammation by forming a mass of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Biopsy would reveal that the mass also shows signs of chronic inflammation. Ordinary bacterial culture often shows nothing because the predominant organism is an anaerobe. At most, one might see a polymicrobial result.

TREATMENT

For affected patients, a dentist can be considered for radiography of the area to confirm the location of the periapical abscess. Then the tooth is usually extracted, resulting in a cure. No further treatment of the sinus tract is necessary because it will essentially disappear over time. The tract does not require excision because it is lined with reactive granulation tissue and not epithelium (as is the case for many other fistular processes).

If the dental exam and radiograph fail to show the expected result, the other diagnoses—thyroglossal duct cyst, branchial cleft cyst, squamous cell carcinoma—would have to be considered.

For 4 years, the lesion on this 66-year-old woman’s chin has been growing slowly, causing little or no pain. However, a foul-smelling cloudy liquid drains from the site about once a week and—understandably—causes her considerable distress. Her primary care provider (PCP) regarded the problem as an infection and prescribed an antibiotic, which reduced the lesion’s size for a time. However, it soon grew again after the patient completed the treatment.

The patient denies any other serious health conditions such as diabetes or immunosuppression. She states she never had an injury to this area. Concerned about the possibility of skin cancer, the PCP refers the patient to dermatology.

Physical exam reveals a patient in no particular distress, afebrile, and oriented in all 3 spheres. She is cooperative with the history and exam. Her husband, who has accompanied her, helps to corroborate her answers.

The lesion is striking both in size (2.8 cm) and mixed morphology. A deeply retracted 1.5-cm dimple is located on the right lower chin/submental interface, situated evenly with the right lateral oral commissure. There is no erythema in this area or elsewhere in or around the lesion.

A fleshy, vermicular, 2 × 4–mm, soft, friable linear mass protrudes from the dimple, extending toward the submental region. Gentle pressure produces a small amount of pustular material issuing from the center of the retracted area. There are no other nodes in the region. There is little or no evidence of past overexposure to ultraviolet sources (dyschromia, weathering, actinic keratoses, or telangiectasias).

Lesion Has Been Giving Him an Earful

ANSWER

The correct answer is gouty tophus (choice “b”).

DISCUSSION

Gout is a defect of purine metabolism, usually caused by underexcretion of uric acid. Diet and heredity also play parts in gout’s development. Gouty tophi usually develop after years of hyperuricemia. As uric acid builds up in the bloodstream over time, it can then begin to be deposited into joints—most commonly the first metatarsal-phalangeal—as well as cartilage or even bones.

On further questioning, the patient recalled having been told on several occasions that his serum uric acid was elevated. In retrospect, his arthritis was most likely gouty in nature.

In terms of the differential, BCC (choice “a”) is common on helical rims, but it would not have contained the type of material found in this patient’s lesion. Also, it would not have waxed and waned as this lesion had done.

Epidermal cysts (choice “c”) can certainly come and go in prominence, but they are filled with a cheesy, pasty material—not the dry crystalline substance found in this lesion. Moreover, most epidermal cysts will have a small comedonal punctum over the center of the lesion. Dystrophic calcification (choice “d”) can mimic gouty tophi, but it is usually rough, firm, and fixed. It certainly would not be coming and going as it pleases.

TREATMENT

Surgical excision of the tophus was offered, but the patient was content with knowing the correct diagnosis. His PCP had previously explained therapeutic options—such as medication and dietary changes—that could address the overall problem. The patient elected to pursue treatment with his PCP.

ANSWER

The correct answer is gouty tophus (choice “b”).

DISCUSSION

Gout is a defect of purine metabolism, usually caused by underexcretion of uric acid. Diet and heredity also play parts in gout’s development. Gouty tophi usually develop after years of hyperuricemia. As uric acid builds up in the bloodstream over time, it can then begin to be deposited into joints—most commonly the first metatarsal-phalangeal—as well as cartilage or even bones.

On further questioning, the patient recalled having been told on several occasions that his serum uric acid was elevated. In retrospect, his arthritis was most likely gouty in nature.

In terms of the differential, BCC (choice “a”) is common on helical rims, but it would not have contained the type of material found in this patient’s lesion. Also, it would not have waxed and waned as this lesion had done.

Epidermal cysts (choice “c”) can certainly come and go in prominence, but they are filled with a cheesy, pasty material—not the dry crystalline substance found in this lesion. Moreover, most epidermal cysts will have a small comedonal punctum over the center of the lesion. Dystrophic calcification (choice “d”) can mimic gouty tophi, but it is usually rough, firm, and fixed. It certainly would not be coming and going as it pleases.

TREATMENT

Surgical excision of the tophus was offered, but the patient was content with knowing the correct diagnosis. His PCP had previously explained therapeutic options—such as medication and dietary changes—that could address the overall problem. The patient elected to pursue treatment with his PCP.

ANSWER

The correct answer is gouty tophus (choice “b”).

DISCUSSION

Gout is a defect of purine metabolism, usually caused by underexcretion of uric acid. Diet and heredity also play parts in gout’s development. Gouty tophi usually develop after years of hyperuricemia. As uric acid builds up in the bloodstream over time, it can then begin to be deposited into joints—most commonly the first metatarsal-phalangeal—as well as cartilage or even bones.

On further questioning, the patient recalled having been told on several occasions that his serum uric acid was elevated. In retrospect, his arthritis was most likely gouty in nature.

In terms of the differential, BCC (choice “a”) is common on helical rims, but it would not have contained the type of material found in this patient’s lesion. Also, it would not have waxed and waned as this lesion had done.

Epidermal cysts (choice “c”) can certainly come and go in prominence, but they are filled with a cheesy, pasty material—not the dry crystalline substance found in this lesion. Moreover, most epidermal cysts will have a small comedonal punctum over the center of the lesion. Dystrophic calcification (choice “d”) can mimic gouty tophi, but it is usually rough, firm, and fixed. It certainly would not be coming and going as it pleases.

TREATMENT

Surgical excision of the tophus was offered, but the patient was content with knowing the correct diagnosis. His PCP had previously explained therapeutic options—such as medication and dietary changes—that could address the overall problem. The patient elected to pursue treatment with his PCP.

Over the years, the lesion on this 49-year-old man’s right ear has waxed and waned in prominence. Although it never causes pain, its unrelenting existence coupled with a history of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) on his face has caused him to worry. He has had no other lesions and is in otherwise good health, except for occasional bouts of arthritis, for which he takes ibuprofen, with good results.

While his family had suggested that the lesion could be a cyst, his primary care provider (PCP) disagreed and referred him to dermatology.

A 5-mm firm papule is located at the right helical crest. The lesion is skin-colored, with no redness, and nontender on palpation, although it is moderately firm and mobile. No punctum is noted.

The surrounding skin has no signs of sun damage, although the patient is quite fair. As a young man, he had far too much sun exposure, burning easily and tanning only with difficulty.

After consultation with the patient, the decision is made to incise the lesion using a #11 blade to examine its contents. The incision reveals a dry crystalline substance, which is easily cleared with brief curettage. This effectively leads to a flattening of the lesion.

Digits in Distress

ANSWER

The correct answer is acrodermatitis of Hallopeau (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Acrodermatitis of Hallopeau (ADH), a rare form of pustular psoriasis, affects the distal digits with changes typified by this patient’s case. It is notoriously difficult to treat, although the advent of the “biologic age” appears to offer a quantum leap in terms of effective treatment alternatives.

Prompt referral to dermatology is needed for ADH to be readily diagnosed and treated. Because ADH is both rare and obscure, it’s not surprising that so many patients suffer for years due to an incorrect diagnosis. And even when correctly diagnosed, treatment is far from satisfactory. For example, methotrexate is commonly used for psoriasis vulgaris but rarely improves ADH—nor do topical steroids or vitamin D–derived topicals.

The 3 other items in the differential would not explain the patient’s condition: (1) Except in cases of immunosuppression, we would not expect Candida (choice “a”) or any other yeast infection to manifest in this manner. (2) Atypical mycobacteria (choice “b”)—such as Mycobacterium marinum—can cause skin infections, but not in a chronically relapsing manner. Moreover, this patient was given minocycline, which would have quickly cleared or at least improved his condition. (3) Pityriasis rubra pilaris (choice “d”) is an unusual papulosquamous disease that can affect nails, but its manifestation would not be as limited as this patient’s was.

TREATMENT

Because the patient’s symptoms are sometimes severe enough to interfere with almost all daily activities, he is clearly in need of prompt treatment. In more severe cases, a short course of cyclosporine followed by a biologic can be an option. For this patient, adalimumab was used. Although it is too early to tell, we expect him to be much improved within a few months.

ANSWER

The correct answer is acrodermatitis of Hallopeau (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Acrodermatitis of Hallopeau (ADH), a rare form of pustular psoriasis, affects the distal digits with changes typified by this patient’s case. It is notoriously difficult to treat, although the advent of the “biologic age” appears to offer a quantum leap in terms of effective treatment alternatives.

Prompt referral to dermatology is needed for ADH to be readily diagnosed and treated. Because ADH is both rare and obscure, it’s not surprising that so many patients suffer for years due to an incorrect diagnosis. And even when correctly diagnosed, treatment is far from satisfactory. For example, methotrexate is commonly used for psoriasis vulgaris but rarely improves ADH—nor do topical steroids or vitamin D–derived topicals.

The 3 other items in the differential would not explain the patient’s condition: (1) Except in cases of immunosuppression, we would not expect Candida (choice “a”) or any other yeast infection to manifest in this manner. (2) Atypical mycobacteria (choice “b”)—such as Mycobacterium marinum—can cause skin infections, but not in a chronically relapsing manner. Moreover, this patient was given minocycline, which would have quickly cleared or at least improved his condition. (3) Pityriasis rubra pilaris (choice “d”) is an unusual papulosquamous disease that can affect nails, but its manifestation would not be as limited as this patient’s was.

TREATMENT

Because the patient’s symptoms are sometimes severe enough to interfere with almost all daily activities, he is clearly in need of prompt treatment. In more severe cases, a short course of cyclosporine followed by a biologic can be an option. For this patient, adalimumab was used. Although it is too early to tell, we expect him to be much improved within a few months.

ANSWER

The correct answer is acrodermatitis of Hallopeau (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Acrodermatitis of Hallopeau (ADH), a rare form of pustular psoriasis, affects the distal digits with changes typified by this patient’s case. It is notoriously difficult to treat, although the advent of the “biologic age” appears to offer a quantum leap in terms of effective treatment alternatives.

Prompt referral to dermatology is needed for ADH to be readily diagnosed and treated. Because ADH is both rare and obscure, it’s not surprising that so many patients suffer for years due to an incorrect diagnosis. And even when correctly diagnosed, treatment is far from satisfactory. For example, methotrexate is commonly used for psoriasis vulgaris but rarely improves ADH—nor do topical steroids or vitamin D–derived topicals.

The 3 other items in the differential would not explain the patient’s condition: (1) Except in cases of immunosuppression, we would not expect Candida (choice “a”) or any other yeast infection to manifest in this manner. (2) Atypical mycobacteria (choice “b”)—such as Mycobacterium marinum—can cause skin infections, but not in a chronically relapsing manner. Moreover, this patient was given minocycline, which would have quickly cleared or at least improved his condition. (3) Pityriasis rubra pilaris (choice “d”) is an unusual papulosquamous disease that can affect nails, but its manifestation would not be as limited as this patient’s was.

TREATMENT

Because the patient’s symptoms are sometimes severe enough to interfere with almost all daily activities, he is clearly in need of prompt treatment. In more severe cases, a short course of cyclosporine followed by a biologic can be an option. For this patient, adalimumab was used. Although it is too early to tell, we expect him to be much improved within a few months.

For years, a 29-year-old man has been troubled by persistent painful outbreaks on his right thumb and forefinger and left great toe. The condition sometimes prevents him from engaging in daily activities. Several health care providers—none a dermatology specialist—attempted to treat him with topical and oral antifungals (clotrimazole and terbinafine), topical steroids (triamcinolone and clobetasol), and oral antibiotics (including minocycline)—none of which had an impact.

His latest provider, a podiatrist, was sure the problem was fungal in origin and prescribed another course of antifungal treatment. When this failed to produce a benefit, the podiatrist conceded that he was at a loss and referred the patient to dermatology.

On physical exam, the 3 affected digits show similar characteristics: the skin is covered by dense, tenacious scaling on a dark red base. Small pustules are noted on these areas in addition to marked dystrophy of the adjacent nails. Bacterial and fungal cultures of the pustular fluid show no growth.

The rest of the patient’s skin—elbows, oral mucosa, knees, and scalp—show no noteworthy changes. He has no other skin problems. There is no family history of psoriasis or other skin conditions.

Baby’s Got Back Rash

ANSWER

The correct answer is psoriasis vulgaris (choice “a”).

DISCUSSION

At least 30% of patients with psoriasis have a family history of the disease—a meaningful clue in developing a differential. Besides asking about the history, always look for corroborating signs in areas where the disease is commonly seen (eg, the fingernails). In this case, further corroboration was provided by the history of illness at the time of the rash’s onset; what was initially strep-driven guttate psoriasis morphed into full-blown psoriasis vulgaris.

The heavy scales, with their salmon-pink base, tipped the scales in favor of psoriasis as the diagnosis. The pinpoint bleeding (known as the Auspitz sign), although not pathognomic for psoriasis, is certainly suggestive of it.

In adults, these findings would probably have been sufficient to settle on psoriasis. But before labeling a young child with a serious, lifelong diagnosis, it was necessary to be sure. For one thing, advanced psoriasis is very unusual in children as young as this patient, and for another, treatment would likely be problematic. Fortunately for clarity’s sake, the biopsy was consistent with psoriasis and inconsistent with the other items in the differential.

TREATMENT

The patient was prescribed a topical steroid cream to apply every other day, alternating with vitamin D–derived ointment. In addition, he was advised to increase his exposure to natural sunlight. Phototherapy with narrow-band ultraviolet light B would be a superior option, but his family lives too far from the clinic to make 3 roundtrips per week for such treatment.

If these measures fail, a biologic agent may be appropriate. Unfortunately, the patient’s insurance carrier requires the failure of several other modalities before it will approve use of such therapy.

ANSWER

The correct answer is psoriasis vulgaris (choice “a”).

DISCUSSION

At least 30% of patients with psoriasis have a family history of the disease—a meaningful clue in developing a differential. Besides asking about the history, always look for corroborating signs in areas where the disease is commonly seen (eg, the fingernails). In this case, further corroboration was provided by the history of illness at the time of the rash’s onset; what was initially strep-driven guttate psoriasis morphed into full-blown psoriasis vulgaris.

The heavy scales, with their salmon-pink base, tipped the scales in favor of psoriasis as the diagnosis. The pinpoint bleeding (known as the Auspitz sign), although not pathognomic for psoriasis, is certainly suggestive of it.

In adults, these findings would probably have been sufficient to settle on psoriasis. But before labeling a young child with a serious, lifelong diagnosis, it was necessary to be sure. For one thing, advanced psoriasis is very unusual in children as young as this patient, and for another, treatment would likely be problematic. Fortunately for clarity’s sake, the biopsy was consistent with psoriasis and inconsistent with the other items in the differential.

TREATMENT

The patient was prescribed a topical steroid cream to apply every other day, alternating with vitamin D–derived ointment. In addition, he was advised to increase his exposure to natural sunlight. Phototherapy with narrow-band ultraviolet light B would be a superior option, but his family lives too far from the clinic to make 3 roundtrips per week for such treatment.

If these measures fail, a biologic agent may be appropriate. Unfortunately, the patient’s insurance carrier requires the failure of several other modalities before it will approve use of such therapy.

ANSWER

The correct answer is psoriasis vulgaris (choice “a”).

DISCUSSION

At least 30% of patients with psoriasis have a family history of the disease—a meaningful clue in developing a differential. Besides asking about the history, always look for corroborating signs in areas where the disease is commonly seen (eg, the fingernails). In this case, further corroboration was provided by the history of illness at the time of the rash’s onset; what was initially strep-driven guttate psoriasis morphed into full-blown psoriasis vulgaris.

The heavy scales, with their salmon-pink base, tipped the scales in favor of psoriasis as the diagnosis. The pinpoint bleeding (known as the Auspitz sign), although not pathognomic for psoriasis, is certainly suggestive of it.

In adults, these findings would probably have been sufficient to settle on psoriasis. But before labeling a young child with a serious, lifelong diagnosis, it was necessary to be sure. For one thing, advanced psoriasis is very unusual in children as young as this patient, and for another, treatment would likely be problematic. Fortunately for clarity’s sake, the biopsy was consistent with psoriasis and inconsistent with the other items in the differential.

TREATMENT

The patient was prescribed a topical steroid cream to apply every other day, alternating with vitamin D–derived ointment. In addition, he was advised to increase his exposure to natural sunlight. Phototherapy with narrow-band ultraviolet light B would be a superior option, but his family lives too far from the clinic to make 3 roundtrips per week for such treatment.

If these measures fail, a biologic agent may be appropriate. Unfortunately, the patient’s insurance carrier requires the failure of several other modalities before it will approve use of such therapy.

Several months ago, a rash of numerous small, red, scaly papules and patches manifested on this 3-year-old boy’s back and shoulders. At the time, he had been ill for about a week, and his primary care provider diagnosed chickenpox—even though the child had been immunized.

Although the patient’s health soon improved, the appearance of the rash worsened. Treatment with various products—including calamine lotion, OTC tolnaftate and miconazole, and a 2-week course of oral antibiotics—was of no help. Finally, the patient was referred to dermatology.

Family history is positive for psoriasis. However, the parents are quick to note that the boy’s rash appears far different from that of affected family members, and previous providers have dismissed this diagnosis from the differential. There is no family or personal history of atopy.

Examination reveals a dense papulosquamous rash mainly confined to the child’s back and posterior shoulders (the area over the scapula). No other areas are similarly affected, but 1 fingernail is mildly pitted.

A #10 blade lifts the edge of one of the scales gently (and painlessly) until there is pinpoint bleeding from 2 tiny foci. A 5-mm full-thickness punch biopsy with primary closure shows marked parakeratosis, collections of neutrophils on the crests of dermal papillae, and fusing of rete ridges, which effectively obscure the normal wave-like pattern of the dermoepidermal junction.

Chin There, Done That—Now What?

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a 3-mm punch biopsy (choice “a”).

DISCUSSION

When the history and physical exam fail to point to a clear diagnosis, skin biopsy can answer a very basic question: What is the pathophysiologic process associated with the lesions? The information thus obtained doesn’t always produce a blinking neon sign of a diagnosis, but at a minimum, it can rule out a great number of things, such as cancer or infection.

More often, the types of cells seen, and the patterns in which they are arranged, tell us a great deal. In this case, accumulations of monocytes, macrophages, and activated T-lymphocytes were arranged in circular patterns, but there was no evidence of necrosis (caseation), which can be seen in tubercular granulomas. Stains performed to identify mycobacterial organisms were negative. These findings established the diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis, a granulomatous disease thought to represent a reaction to an unknown antigen (eg, a microorganism) or environmental substance. It is far more common in those with darker skin types.

Although this patient’s disease was confined to the skin, sarcoidosis can affect virtually any other organ in the body—in particular, the lungs, kidneys, liver, nervous system, or even the eyes. For this reason, patients with sarcoidosis are usually referred to pulmonology for a workup intended to rule out systemic involvement and to other specialists as symptoms dictate.

Many cases of sarcoidosis remit on their own, without treatment. When treatment is initiated, the 2 most commonly used medications are systemic glucocorticoids and/or methotrexate. Both drugs have been associated with serious adverse effects and should only be prescribed by experienced providers.

This combination was prescribed for the case patient, who obtained rapid relief. Blood work (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel) was within normal limits prior to and during treatment, and the pulmonologist pronounced her free of lung involvement.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a 3-mm punch biopsy (choice “a”).

DISCUSSION

When the history and physical exam fail to point to a clear diagnosis, skin biopsy can answer a very basic question: What is the pathophysiologic process associated with the lesions? The information thus obtained doesn’t always produce a blinking neon sign of a diagnosis, but at a minimum, it can rule out a great number of things, such as cancer or infection.

More often, the types of cells seen, and the patterns in which they are arranged, tell us a great deal. In this case, accumulations of monocytes, macrophages, and activated T-lymphocytes were arranged in circular patterns, but there was no evidence of necrosis (caseation), which can be seen in tubercular granulomas. Stains performed to identify mycobacterial organisms were negative. These findings established the diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis, a granulomatous disease thought to represent a reaction to an unknown antigen (eg, a microorganism) or environmental substance. It is far more common in those with darker skin types.

Although this patient’s disease was confined to the skin, sarcoidosis can affect virtually any other organ in the body—in particular, the lungs, kidneys, liver, nervous system, or even the eyes. For this reason, patients with sarcoidosis are usually referred to pulmonology for a workup intended to rule out systemic involvement and to other specialists as symptoms dictate.

Many cases of sarcoidosis remit on their own, without treatment. When treatment is initiated, the 2 most commonly used medications are systemic glucocorticoids and/or methotrexate. Both drugs have been associated with serious adverse effects and should only be prescribed by experienced providers.

This combination was prescribed for the case patient, who obtained rapid relief. Blood work (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel) was within normal limits prior to and during treatment, and the pulmonologist pronounced her free of lung involvement.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a 3-mm punch biopsy (choice “a”).

DISCUSSION

When the history and physical exam fail to point to a clear diagnosis, skin biopsy can answer a very basic question: What is the pathophysiologic process associated with the lesions? The information thus obtained doesn’t always produce a blinking neon sign of a diagnosis, but at a minimum, it can rule out a great number of things, such as cancer or infection.

More often, the types of cells seen, and the patterns in which they are arranged, tell us a great deal. In this case, accumulations of monocytes, macrophages, and activated T-lymphocytes were arranged in circular patterns, but there was no evidence of necrosis (caseation), which can be seen in tubercular granulomas. Stains performed to identify mycobacterial organisms were negative. These findings established the diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis, a granulomatous disease thought to represent a reaction to an unknown antigen (eg, a microorganism) or environmental substance. It is far more common in those with darker skin types.

Although this patient’s disease was confined to the skin, sarcoidosis can affect virtually any other organ in the body—in particular, the lungs, kidneys, liver, nervous system, or even the eyes. For this reason, patients with sarcoidosis are usually referred to pulmonology for a workup intended to rule out systemic involvement and to other specialists as symptoms dictate.

Many cases of sarcoidosis remit on their own, without treatment. When treatment is initiated, the 2 most commonly used medications are systemic glucocorticoids and/or methotrexate. Both drugs have been associated with serious adverse effects and should only be prescribed by experienced providers.

This combination was prescribed for the case patient, who obtained rapid relief. Blood work (complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel) was within normal limits prior to and during treatment, and the pulmonologist pronounced her free of lung involvement.

A 51-year-old woman is referred to dermatology for evaluation of a facial rash that has been present, on and off, for years. It usually affects her right chin and perioral area but occasionally manifests with smaller yet similar lesions elsewhere on the face. The lesions are slightly itchy, but the patient’s main concern is their impact on her appearance.

She has consulted several primary care providers over the years, all of whom initially diagnosed and treated for acne—to no avail. This was typically followed by a recommendation to try an OTC topical product, such as an antifungal (tolnaftate and clotrimazole), hydrocortisone 1%, or triple-antibiotic cream—again, without improvement. At no point was a biopsy suggested.

Examination reveals a dense cluster of papules covering a 5×4-cm section of the right chin and perioral area. Although the lesions appear vesicular, they are in fact solid but soft, shiny, and confluent. The papules are about the same color as her type IV skin. There are no comedones or pustules.

No adenopathy is detected in the region. There is no involvement of the adjacent oral mucosal surfaces.

The patient’s skin elsewhere is unremarkable, and in general, she appears to be in good health (certainly in no distress). She claims to be healthy otherwise, with no fever, malaise, joint pain, fatigue, or shortness of breath. No one else in her household is similarly affected.

Getting a Leg up on the Diagnosis

Three years ago, lesions began appearing on this now 68-year-old woman’s legs. They have grown in size and number, and their roughness disturbs the patient. She has been told the lesions are related to aging, but she has never seen anything like them on her friends or family—and she is worried about what they might mean for her health.

Her primary care provider diagnosed warts and performed cryotherapy on several of the lesions. However, the pain was intolerable and the treatment ineffective. To add insult to injury, each treated spot blistered and took more than a month to heal, leaving behind a pinkish brown blemish.

In all other respects, the patient’s health is excellent.

EXAMINATION

Both legs, from the upper thighs to the tops of the feet, are covered with thousands of uniformly distributed, tiny, keratotic, rough, dry papules. All the lesions are essentially identical: white, with no associated signs of inflammation. The patient’s skin is quite dry in general. Neither her palms nor soles are affected.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The most common problem seen in dermatology offices worldwide is seborrheic keratosis (SK), a totally benign epidermal excrescence that appears to be related to aging and heredity. Most patients are in their 50s when they first notice an SK, and with a bit of luck, they will only see a few in their lifetime. But some patients develop hundreds of SKs, many of which become quite large (3-5 cm) and unsightly. In certain circumstances, SKs can herald the arrival of an occult carcinoma (the Leser-Trelat sign).

This patient has what some consider a variant of SK, called stucco keratosis. These lesions manifest almost exclusively on the lower legs and feet—perhaps due to the relative lack of sebaceous glands in those areas—and most often on men older than 60. Distressing as they are, stucco keratoses have no pathologic implications.

Grossly and histologically, stucco keratoses are different from ordinary SKs. Each stucco keratosis lesion is essentially identical to the others, with a spiculated surface, white color, and average diameter of 2 to 3 mm. Histologically, they demonstrate a thickened epidermis with focal exophytic upward projections that resemble church spires. The lesions do not extend into the dermis.

Treatment of stucco keratoses is, at best, tedious, painful, and futile. The modalities used are cryotherapy or electrodessication with curettage. For a degree of comfort, use of a loofah after bathing will remove or smooth down a few lesions, but this process must be followed by application of a heavy emollient. Alas, regrowth is a certainty.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Stucco keratosis is considered a variant of seborrheic keratosis, although they differ in several significant ways.

- The lesions of stucco keratosis are fairly uniform in appearance: white, rough, spiculated, epidermal papules measuring 2 to 3 mm.

- Stucco keratoses affect about 10% of the population (men more often than women) and have no racial predilection or pathologic implications.

- The lesions are found almost exclusively on the legs, from the knees down to and including the dorsa of the feet.

- Treatment is far from satisfactory, for multiple reasons, including resultant pain and scarring.

Three years ago, lesions began appearing on this now 68-year-old woman’s legs. They have grown in size and number, and their roughness disturbs the patient. She has been told the lesions are related to aging, but she has never seen anything like them on her friends or family—and she is worried about what they might mean for her health.

Her primary care provider diagnosed warts and performed cryotherapy on several of the lesions. However, the pain was intolerable and the treatment ineffective. To add insult to injury, each treated spot blistered and took more than a month to heal, leaving behind a pinkish brown blemish.

In all other respects, the patient’s health is excellent.

EXAMINATION

Both legs, from the upper thighs to the tops of the feet, are covered with thousands of uniformly distributed, tiny, keratotic, rough, dry papules. All the lesions are essentially identical: white, with no associated signs of inflammation. The patient’s skin is quite dry in general. Neither her palms nor soles are affected.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The most common problem seen in dermatology offices worldwide is seborrheic keratosis (SK), a totally benign epidermal excrescence that appears to be related to aging and heredity. Most patients are in their 50s when they first notice an SK, and with a bit of luck, they will only see a few in their lifetime. But some patients develop hundreds of SKs, many of which become quite large (3-5 cm) and unsightly. In certain circumstances, SKs can herald the arrival of an occult carcinoma (the Leser-Trelat sign).

This patient has what some consider a variant of SK, called stucco keratosis. These lesions manifest almost exclusively on the lower legs and feet—perhaps due to the relative lack of sebaceous glands in those areas—and most often on men older than 60. Distressing as they are, stucco keratoses have no pathologic implications.

Grossly and histologically, stucco keratoses are different from ordinary SKs. Each stucco keratosis lesion is essentially identical to the others, with a spiculated surface, white color, and average diameter of 2 to 3 mm. Histologically, they demonstrate a thickened epidermis with focal exophytic upward projections that resemble church spires. The lesions do not extend into the dermis.

Treatment of stucco keratoses is, at best, tedious, painful, and futile. The modalities used are cryotherapy or electrodessication with curettage. For a degree of comfort, use of a loofah after bathing will remove or smooth down a few lesions, but this process must be followed by application of a heavy emollient. Alas, regrowth is a certainty.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Stucco keratosis is considered a variant of seborrheic keratosis, although they differ in several significant ways.

- The lesions of stucco keratosis are fairly uniform in appearance: white, rough, spiculated, epidermal papules measuring 2 to 3 mm.

- Stucco keratoses affect about 10% of the population (men more often than women) and have no racial predilection or pathologic implications.

- The lesions are found almost exclusively on the legs, from the knees down to and including the dorsa of the feet.

- Treatment is far from satisfactory, for multiple reasons, including resultant pain and scarring.

Three years ago, lesions began appearing on this now 68-year-old woman’s legs. They have grown in size and number, and their roughness disturbs the patient. She has been told the lesions are related to aging, but she has never seen anything like them on her friends or family—and she is worried about what they might mean for her health.

Her primary care provider diagnosed warts and performed cryotherapy on several of the lesions. However, the pain was intolerable and the treatment ineffective. To add insult to injury, each treated spot blistered and took more than a month to heal, leaving behind a pinkish brown blemish.

In all other respects, the patient’s health is excellent.

EXAMINATION

Both legs, from the upper thighs to the tops of the feet, are covered with thousands of uniformly distributed, tiny, keratotic, rough, dry papules. All the lesions are essentially identical: white, with no associated signs of inflammation. The patient’s skin is quite dry in general. Neither her palms nor soles are affected.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The most common problem seen in dermatology offices worldwide is seborrheic keratosis (SK), a totally benign epidermal excrescence that appears to be related to aging and heredity. Most patients are in their 50s when they first notice an SK, and with a bit of luck, they will only see a few in their lifetime. But some patients develop hundreds of SKs, many of which become quite large (3-5 cm) and unsightly. In certain circumstances, SKs can herald the arrival of an occult carcinoma (the Leser-Trelat sign).

This patient has what some consider a variant of SK, called stucco keratosis. These lesions manifest almost exclusively on the lower legs and feet—perhaps due to the relative lack of sebaceous glands in those areas—and most often on men older than 60. Distressing as they are, stucco keratoses have no pathologic implications.

Grossly and histologically, stucco keratoses are different from ordinary SKs. Each stucco keratosis lesion is essentially identical to the others, with a spiculated surface, white color, and average diameter of 2 to 3 mm. Histologically, they demonstrate a thickened epidermis with focal exophytic upward projections that resemble church spires. The lesions do not extend into the dermis.

Treatment of stucco keratoses is, at best, tedious, painful, and futile. The modalities used are cryotherapy or electrodessication with curettage. For a degree of comfort, use of a loofah after bathing will remove or smooth down a few lesions, but this process must be followed by application of a heavy emollient. Alas, regrowth is a certainty.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Stucco keratosis is considered a variant of seborrheic keratosis, although they differ in several significant ways.

- The lesions of stucco keratosis are fairly uniform in appearance: white, rough, spiculated, epidermal papules measuring 2 to 3 mm.

- Stucco keratoses affect about 10% of the population (men more often than women) and have no racial predilection or pathologic implications.

- The lesions are found almost exclusively on the legs, from the knees down to and including the dorsa of the feet.

- Treatment is far from satisfactory, for multiple reasons, including resultant pain and scarring.

Keeping Lesions at Arm’s Length

A 14-year-old boy presents to dermatology for evaluation of an asymptomatic “rash” present on his arms since age 6. The condition has caught the attention of family members and teachers over the years, particularly in regard to possible contagion.

The patient is otherwise reasonably healthy, although he has asthma and seasonal allergies.

EXAMINATION

The "rash" consists of uniformly distributed and sized planar papules. Although they are tiny, averaging only 1 mm wide, they are prominent enough to be noticeable and palpable. They appear slightly lighter than the surrounding skin. Distribution is from the lower deltoid to mid-dorsal forearm, affecting both arms identically. The volar aspects and triceps of both arms are totally spared.

The patient has type IV skin.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case is an almost perfect representation of lichen nitidus (LN), in terms of morphology, distribution, and configuration. Close examination of individual lesions revealed that the papules were somewhat planar (ie, flat-topped), giving their surfaces a reflective appearance that the eye interprets as white (particularly contrasted with darker skin).

LN can occur in anyone, but it is most often seen in those with darker skin. It is also frequently seen in children, many of whom are atopic, with dry, sensitive skin that is prone to eczema.

In terms of distribution, LN typically affects the extensor triceps, elbow, and forearms bilaterally. With its flat-topped and shiny appearance, LN is sometimes called "mini-lichen planus"—a condition that can demonstrate similar features. Fortunately, LN is seldom itchy and shares none of the distinct histologic characteristics of lichen planus.

LN is quite unusual, if not rare. It is also idiopathic and nearly always resolves on its own—although this can take months to years.

Emollients help to make the affected skin smoother and less visible. Class 4 steroid creams (eg, triamcinolone 0.05%) can help with itching.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen nitidus (LN) is a rare idiopathic skin condition manifesting with patches of tiny planar papules; it typically affects the elbow and dorsal forearm.

- LN has no pathologic implications and is asymptomatic and self-limited.

- The lesions of LN have a “lichenoid” appearance—ie, a shiny, flat-topped look similar to that seen with lichen planus.

- Fortunately, LN rarely requires treatment, aside from relief of mild itching.

A 14-year-old boy presents to dermatology for evaluation of an asymptomatic “rash” present on his arms since age 6. The condition has caught the attention of family members and teachers over the years, particularly in regard to possible contagion.

The patient is otherwise reasonably healthy, although he has asthma and seasonal allergies.

EXAMINATION

The "rash" consists of uniformly distributed and sized planar papules. Although they are tiny, averaging only 1 mm wide, they are prominent enough to be noticeable and palpable. They appear slightly lighter than the surrounding skin. Distribution is from the lower deltoid to mid-dorsal forearm, affecting both arms identically. The volar aspects and triceps of both arms are totally spared.

The patient has type IV skin.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case is an almost perfect representation of lichen nitidus (LN), in terms of morphology, distribution, and configuration. Close examination of individual lesions revealed that the papules were somewhat planar (ie, flat-topped), giving their surfaces a reflective appearance that the eye interprets as white (particularly contrasted with darker skin).

LN can occur in anyone, but it is most often seen in those with darker skin. It is also frequently seen in children, many of whom are atopic, with dry, sensitive skin that is prone to eczema.

In terms of distribution, LN typically affects the extensor triceps, elbow, and forearms bilaterally. With its flat-topped and shiny appearance, LN is sometimes called "mini-lichen planus"—a condition that can demonstrate similar features. Fortunately, LN is seldom itchy and shares none of the distinct histologic characteristics of lichen planus.

LN is quite unusual, if not rare. It is also idiopathic and nearly always resolves on its own—although this can take months to years.

Emollients help to make the affected skin smoother and less visible. Class 4 steroid creams (eg, triamcinolone 0.05%) can help with itching.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen nitidus (LN) is a rare idiopathic skin condition manifesting with patches of tiny planar papules; it typically affects the elbow and dorsal forearm.

- LN has no pathologic implications and is asymptomatic and self-limited.

- The lesions of LN have a “lichenoid” appearance—ie, a shiny, flat-topped look similar to that seen with lichen planus.

- Fortunately, LN rarely requires treatment, aside from relief of mild itching.

A 14-year-old boy presents to dermatology for evaluation of an asymptomatic “rash” present on his arms since age 6. The condition has caught the attention of family members and teachers over the years, particularly in regard to possible contagion.

The patient is otherwise reasonably healthy, although he has asthma and seasonal allergies.

EXAMINATION

The "rash" consists of uniformly distributed and sized planar papules. Although they are tiny, averaging only 1 mm wide, they are prominent enough to be noticeable and palpable. They appear slightly lighter than the surrounding skin. Distribution is from the lower deltoid to mid-dorsal forearm, affecting both arms identically. The volar aspects and triceps of both arms are totally spared.

The patient has type IV skin.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This case is an almost perfect representation of lichen nitidus (LN), in terms of morphology, distribution, and configuration. Close examination of individual lesions revealed that the papules were somewhat planar (ie, flat-topped), giving their surfaces a reflective appearance that the eye interprets as white (particularly contrasted with darker skin).

LN can occur in anyone, but it is most often seen in those with darker skin. It is also frequently seen in children, many of whom are atopic, with dry, sensitive skin that is prone to eczema.

In terms of distribution, LN typically affects the extensor triceps, elbow, and forearms bilaterally. With its flat-topped and shiny appearance, LN is sometimes called "mini-lichen planus"—a condition that can demonstrate similar features. Fortunately, LN is seldom itchy and shares none of the distinct histologic characteristics of lichen planus.

LN is quite unusual, if not rare. It is also idiopathic and nearly always resolves on its own—although this can take months to years.

Emollients help to make the affected skin smoother and less visible. Class 4 steroid creams (eg, triamcinolone 0.05%) can help with itching.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Lichen nitidus (LN) is a rare idiopathic skin condition manifesting with patches of tiny planar papules; it typically affects the elbow and dorsal forearm.

- LN has no pathologic implications and is asymptomatic and self-limited.

- The lesions of LN have a “lichenoid” appearance—ie, a shiny, flat-topped look similar to that seen with lichen planus.

- Fortunately, LN rarely requires treatment, aside from relief of mild itching.

The Dog Can Stay, but the Rash Must Go

A 50-year-old man presents with a 1-year history of an itchy, bumpy rash on his chest. He denies any history of similar rash and says there have been no “extraordinary changes” in his life that could have triggered this manifestation. Despite consulting various primary care providers, he has been unable to acquire either a definitive diagnosis or effective treatment.

The patient works exclusively in a climate-controlled office. Although there were no changes to laundry detergent, body soap, deodorant, or other products that might have precipitated the rash’s manifestation, he tried alternate products to see what effect they might have. Nothing beneficial came from these experiments. Similarly, the family dogs were temporarily “banished” with no improvement to his condition.

From the outset, the rash and the associated itching have been confined to the patient’s chest. No one else in his family is similarly affected.

The patient is otherwise quite well. He takes no prescription medications and denies any recent foreign travel.

EXAMINATION

The papulovesicular rash is strikingly uniform. The patient’s entire chest is covered with tiny vesicles, many with clear fluid inside. The lesions average 1.2 to 2 mm in width, and nearly all are quite palpable. Each lesion is slightly erythematous but neither warm nor tender on palpation.

Examination of the rest of the patient’s exposed skin reveals no similar lesions. His back, hands, and genitals are notably free of any such lesions.

A shave biopsy is performed, utilizing a saucerization technique, and the specimen is submitted to pathology for routine processing. The report confirms the papulovesicular nature of the lesions—but more significantly, it shows consistent acantholysis (loss of intracellular connections between keratinocytes), along with focal lymphohistiocytic infiltrates.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a classic presentation of Grover disease, also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis (AD). While not rare, it is seen only occasionally in dermatology practices. When it does walk through the door, it is twice as likely to be seen in a male than in a female patient and less commonly seen in those with darker skin.

AD is easy enough to diagnose clinically, without biopsy, particularly in classic cases such as this one. The distribution and morphology of the rash, as well as the gender and age of the patient, are all typical of this idiopathic condition. The biopsy results, besides being consistent with AD, did serve to rule out other items in the differential (eg, bacterial folliculitis, pemphigus, and acne).

Since AD was first described in 1974 by R.W. Grover, MD, much research has been conducted to flesh out the nature of the disease, its potential causes, and possible treatment. One certainty about so-called transient AD is that most cases are far from transient—in fact, they can last for a year or more. Attempts have been made to connect AD with internal disease (eg, occult malignancy) or even mercury exposure, but these theories have not been corroborated.

Consistent treatment success has also been elusive. Most patients achieve decent relief with the use of topical steroid creams, with or without the addition of anti-inflammatory medications (eg, doxycycline). Other options include isotretinoin and psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) photochemotherapy. Fortunately, most cases eventually clear up.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Grover disease, also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis (AD), usually manifests with an acute eruption of papulovesicular lesions.

- AD lesions tend to be confined to the chest and are typically pruritic.

- Clinical diagnosis is usually adequate, although biopsy, which will reveal typical findings of acantholysis, may be necessary to rule out other items in the differential.

- Treatment with topical steroids, oral doxycycline, and “tincture of time” usually suffices, but resolution may take a year or more.

A 50-year-old man presents with a 1-year history of an itchy, bumpy rash on his chest. He denies any history of similar rash and says there have been no “extraordinary changes” in his life that could have triggered this manifestation. Despite consulting various primary care providers, he has been unable to acquire either a definitive diagnosis or effective treatment.

The patient works exclusively in a climate-controlled office. Although there were no changes to laundry detergent, body soap, deodorant, or other products that might have precipitated the rash’s manifestation, he tried alternate products to see what effect they might have. Nothing beneficial came from these experiments. Similarly, the family dogs were temporarily “banished” with no improvement to his condition.

From the outset, the rash and the associated itching have been confined to the patient’s chest. No one else in his family is similarly affected.

The patient is otherwise quite well. He takes no prescription medications and denies any recent foreign travel.

EXAMINATION

The papulovesicular rash is strikingly uniform. The patient’s entire chest is covered with tiny vesicles, many with clear fluid inside. The lesions average 1.2 to 2 mm in width, and nearly all are quite palpable. Each lesion is slightly erythematous but neither warm nor tender on palpation.

Examination of the rest of the patient’s exposed skin reveals no similar lesions. His back, hands, and genitals are notably free of any such lesions.

A shave biopsy is performed, utilizing a saucerization technique, and the specimen is submitted to pathology for routine processing. The report confirms the papulovesicular nature of the lesions—but more significantly, it shows consistent acantholysis (loss of intracellular connections between keratinocytes), along with focal lymphohistiocytic infiltrates.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a classic presentation of Grover disease, also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis (AD). While not rare, it is seen only occasionally in dermatology practices. When it does walk through the door, it is twice as likely to be seen in a male than in a female patient and less commonly seen in those with darker skin.

AD is easy enough to diagnose clinically, without biopsy, particularly in classic cases such as this one. The distribution and morphology of the rash, as well as the gender and age of the patient, are all typical of this idiopathic condition. The biopsy results, besides being consistent with AD, did serve to rule out other items in the differential (eg, bacterial folliculitis, pemphigus, and acne).

Since AD was first described in 1974 by R.W. Grover, MD, much research has been conducted to flesh out the nature of the disease, its potential causes, and possible treatment. One certainty about so-called transient AD is that most cases are far from transient—in fact, they can last for a year or more. Attempts have been made to connect AD with internal disease (eg, occult malignancy) or even mercury exposure, but these theories have not been corroborated.

Consistent treatment success has also been elusive. Most patients achieve decent relief with the use of topical steroid creams, with or without the addition of anti-inflammatory medications (eg, doxycycline). Other options include isotretinoin and psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) photochemotherapy. Fortunately, most cases eventually clear up.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Grover disease, also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis (AD), usually manifests with an acute eruption of papulovesicular lesions.

- AD lesions tend to be confined to the chest and are typically pruritic.

- Clinical diagnosis is usually adequate, although biopsy, which will reveal typical findings of acantholysis, may be necessary to rule out other items in the differential.

- Treatment with topical steroids, oral doxycycline, and “tincture of time” usually suffices, but resolution may take a year or more.

A 50-year-old man presents with a 1-year history of an itchy, bumpy rash on his chest. He denies any history of similar rash and says there have been no “extraordinary changes” in his life that could have triggered this manifestation. Despite consulting various primary care providers, he has been unable to acquire either a definitive diagnosis or effective treatment.

The patient works exclusively in a climate-controlled office. Although there were no changes to laundry detergent, body soap, deodorant, or other products that might have precipitated the rash’s manifestation, he tried alternate products to see what effect they might have. Nothing beneficial came from these experiments. Similarly, the family dogs were temporarily “banished” with no improvement to his condition.

From the outset, the rash and the associated itching have been confined to the patient’s chest. No one else in his family is similarly affected.

The patient is otherwise quite well. He takes no prescription medications and denies any recent foreign travel.

EXAMINATION

The papulovesicular rash is strikingly uniform. The patient’s entire chest is covered with tiny vesicles, many with clear fluid inside. The lesions average 1.2 to 2 mm in width, and nearly all are quite palpable. Each lesion is slightly erythematous but neither warm nor tender on palpation.

Examination of the rest of the patient’s exposed skin reveals no similar lesions. His back, hands, and genitals are notably free of any such lesions.

A shave biopsy is performed, utilizing a saucerization technique, and the specimen is submitted to pathology for routine processing. The report confirms the papulovesicular nature of the lesions—but more significantly, it shows consistent acantholysis (loss of intracellular connections between keratinocytes), along with focal lymphohistiocytic infiltrates.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This is a classic presentation of Grover disease, also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis (AD). While not rare, it is seen only occasionally in dermatology practices. When it does walk through the door, it is twice as likely to be seen in a male than in a female patient and less commonly seen in those with darker skin.

AD is easy enough to diagnose clinically, without biopsy, particularly in classic cases such as this one. The distribution and morphology of the rash, as well as the gender and age of the patient, are all typical of this idiopathic condition. The biopsy results, besides being consistent with AD, did serve to rule out other items in the differential (eg, bacterial folliculitis, pemphigus, and acne).

Since AD was first described in 1974 by R.W. Grover, MD, much research has been conducted to flesh out the nature of the disease, its potential causes, and possible treatment. One certainty about so-called transient AD is that most cases are far from transient—in fact, they can last for a year or more. Attempts have been made to connect AD with internal disease (eg, occult malignancy) or even mercury exposure, but these theories have not been corroborated.

Consistent treatment success has also been elusive. Most patients achieve decent relief with the use of topical steroid creams, with or without the addition of anti-inflammatory medications (eg, doxycycline). Other options include isotretinoin and psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) photochemotherapy. Fortunately, most cases eventually clear up.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Grover disease, also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis (AD), usually manifests with an acute eruption of papulovesicular lesions.

- AD lesions tend to be confined to the chest and are typically pruritic.

- Clinical diagnosis is usually adequate, although biopsy, which will reveal typical findings of acantholysis, may be necessary to rule out other items in the differential.

- Treatment with topical steroids, oral doxycycline, and “tincture of time” usually suffices, but resolution may take a year or more.

Boy, Is My Face Red!

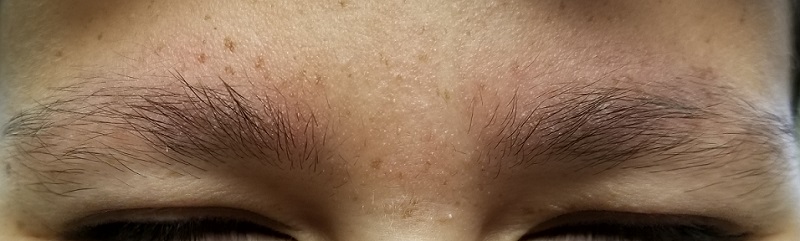

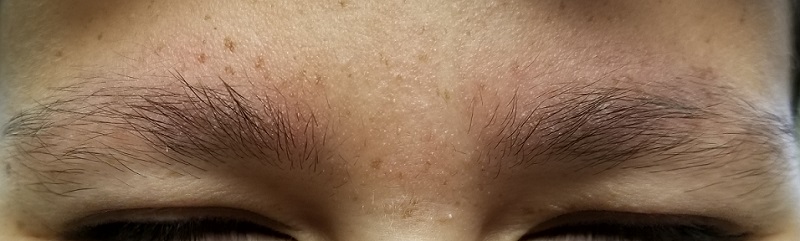

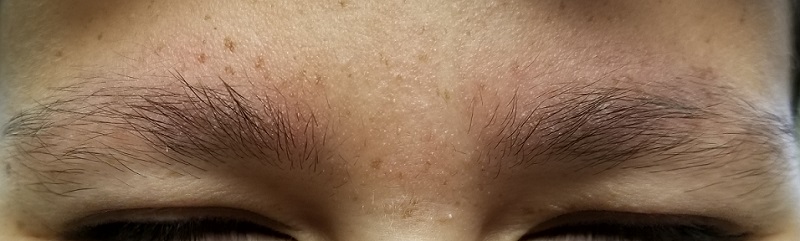

A 17-year-old boy was born with rough skin on his face, arms, legs, thighs, and posterior shoulders. Over the years, his face, especially the posterior lateral aspects, has become progressively redder, while the roughness has increased. The redness is amplified with heat, exertion, anger, or embarrassment. Regarding the latter, mere mention of the condition by his siblings results in worsening of the erythema. Additionally, the skin in his eyebrows is now turning red and scaly.

The patient denies a history of dandruff. His parents, who have accompanied him to the clinic, report a family history of similar skin changes on triceps and thighs, but not on faces. There is no family history of cardiac anomalies or other congenital abnormalities. The boy’s health is otherwise excellent.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s bilateral triceps are covered with fine, rough, follicular papules, which create a faintly erythematous look. Similar lesions are visible on his posterior shoulders and anterior thighs. The skin beneath his eyebrows is faintly erythematous and scaly.

The posterior sides of his face are bright red and covered with the same type of papules. The erythema grows redder as it approaches the immediate preauricular areas, where it ends abruptly, creating a sharp demarcation with the white skin closer to the ears. The visual effect is almost clownish, as if bright red makeup had been applied.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This young man has all the signs of an extremely rare variant of keratosis pilaris (KP) called ulerythema ophryogenes (UO). In the United States, about 40% of adults have ordinary KP, which usually manifests in childhood (with about 80% of cases occurring in adolescent girls). KP is inherited through autosomal dominance, with highly variable penetrance, though no specific gene has been identified. In this form, KP is considered by most experts to be a minor diagnostic criterion for atopic dermatitis.

However, UO is not merely a variant of KP. Over the decades, it has been connected with more serious conditions, such as cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, and Cornelia de Lange disease. Although these conditions are not common, they should be considered when UO is seen.

For this patient, the main concern was his appearance, especially the pronounced erythema around the periphery of his face. This aspect of the problem was addressed with a referral to a provider who can, using an assortment of lasers, try to even out his skin color and hopefully erase the sharp border at the periphery of the affected area.

For the physical discomfort caused by UO, the patient was instructed either to use general moisturizers to reduce dryness or to consider using moisturizers containing salicylic acid, which should help to reduce the prominence of the papules. For the erythema in his brows, he is using 2.5% hydrocortisone ointment two to three times a week.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Ulerythema ophryogenes is a rarely encountered variant of keratosis pilaris—a condition inherited by autosomal dominance with highly variable penetrance.

- Its main significance, beyond cosmetic concerns, is the possible connection with syndromes that involve heart and structural defects (eg, cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome).

- Treatment options include heavy emollients to soften the scaly papules and laser therapy to reduce the extreme redness seen on the periphery of the face.

A 17-year-old boy was born with rough skin on his face, arms, legs, thighs, and posterior shoulders. Over the years, his face, especially the posterior lateral aspects, has become progressively redder, while the roughness has increased. The redness is amplified with heat, exertion, anger, or embarrassment. Regarding the latter, mere mention of the condition by his siblings results in worsening of the erythema. Additionally, the skin in his eyebrows is now turning red and scaly.

The patient denies a history of dandruff. His parents, who have accompanied him to the clinic, report a family history of similar skin changes on triceps and thighs, but not on faces. There is no family history of cardiac anomalies or other congenital abnormalities. The boy’s health is otherwise excellent.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s bilateral triceps are covered with fine, rough, follicular papules, which create a faintly erythematous look. Similar lesions are visible on his posterior shoulders and anterior thighs. The skin beneath his eyebrows is faintly erythematous and scaly.

The posterior sides of his face are bright red and covered with the same type of papules. The erythema grows redder as it approaches the immediate preauricular areas, where it ends abruptly, creating a sharp demarcation with the white skin closer to the ears. The visual effect is almost clownish, as if bright red makeup had been applied.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This young man has all the signs of an extremely rare variant of keratosis pilaris (KP) called ulerythema ophryogenes (UO). In the United States, about 40% of adults have ordinary KP, which usually manifests in childhood (with about 80% of cases occurring in adolescent girls). KP is inherited through autosomal dominance, with highly variable penetrance, though no specific gene has been identified. In this form, KP is considered by most experts to be a minor diagnostic criterion for atopic dermatitis.

However, UO is not merely a variant of KP. Over the decades, it has been connected with more serious conditions, such as cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, and Cornelia de Lange disease. Although these conditions are not common, they should be considered when UO is seen.

For this patient, the main concern was his appearance, especially the pronounced erythema around the periphery of his face. This aspect of the problem was addressed with a referral to a provider who can, using an assortment of lasers, try to even out his skin color and hopefully erase the sharp border at the periphery of the affected area.

For the physical discomfort caused by UO, the patient was instructed either to use general moisturizers to reduce dryness or to consider using moisturizers containing salicylic acid, which should help to reduce the prominence of the papules. For the erythema in his brows, he is using 2.5% hydrocortisone ointment two to three times a week.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Ulerythema ophryogenes is a rarely encountered variant of keratosis pilaris—a condition inherited by autosomal dominance with highly variable penetrance.

- Its main significance, beyond cosmetic concerns, is the possible connection with syndromes that involve heart and structural defects (eg, cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome).

- Treatment options include heavy emollients to soften the scaly papules and laser therapy to reduce the extreme redness seen on the periphery of the face.

A 17-year-old boy was born with rough skin on his face, arms, legs, thighs, and posterior shoulders. Over the years, his face, especially the posterior lateral aspects, has become progressively redder, while the roughness has increased. The redness is amplified with heat, exertion, anger, or embarrassment. Regarding the latter, mere mention of the condition by his siblings results in worsening of the erythema. Additionally, the skin in his eyebrows is now turning red and scaly.

The patient denies a history of dandruff. His parents, who have accompanied him to the clinic, report a family history of similar skin changes on triceps and thighs, but not on faces. There is no family history of cardiac anomalies or other congenital abnormalities. The boy’s health is otherwise excellent.

EXAMINATION

The patient’s bilateral triceps are covered with fine, rough, follicular papules, which create a faintly erythematous look. Similar lesions are visible on his posterior shoulders and anterior thighs. The skin beneath his eyebrows is faintly erythematous and scaly.

The posterior sides of his face are bright red and covered with the same type of papules. The erythema grows redder as it approaches the immediate preauricular areas, where it ends abruptly, creating a sharp demarcation with the white skin closer to the ears. The visual effect is almost clownish, as if bright red makeup had been applied.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

This young man has all the signs of an extremely rare variant of keratosis pilaris (KP) called ulerythema ophryogenes (UO). In the United States, about 40% of adults have ordinary KP, which usually manifests in childhood (with about 80% of cases occurring in adolescent girls). KP is inherited through autosomal dominance, with highly variable penetrance, though no specific gene has been identified. In this form, KP is considered by most experts to be a minor diagnostic criterion for atopic dermatitis.

However, UO is not merely a variant of KP. Over the decades, it has been connected with more serious conditions, such as cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, and Cornelia de Lange disease. Although these conditions are not common, they should be considered when UO is seen.

For this patient, the main concern was his appearance, especially the pronounced erythema around the periphery of his face. This aspect of the problem was addressed with a referral to a provider who can, using an assortment of lasers, try to even out his skin color and hopefully erase the sharp border at the periphery of the affected area.

For the physical discomfort caused by UO, the patient was instructed either to use general moisturizers to reduce dryness or to consider using moisturizers containing salicylic acid, which should help to reduce the prominence of the papules. For the erythema in his brows, he is using 2.5% hydrocortisone ointment two to three times a week.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Ulerythema ophryogenes is a rarely encountered variant of keratosis pilaris—a condition inherited by autosomal dominance with highly variable penetrance.

- Its main significance, beyond cosmetic concerns, is the possible connection with syndromes that involve heart and structural defects (eg, cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome).

- Treatment options include heavy emollients to soften the scaly papules and laser therapy to reduce the extreme redness seen on the periphery of the face.

Start From Scratch

A 50-year-old man presents with complaints of a rash on his right leg that manifested 20 years ago. Although the rash is worrisome, he says the associated pruritus is worse. During the workday, he is able to ignore the itching—but the minute he gets home, he begins to scratch.

He knows the scratching is counterproductive in the long run, but the urge to do it is quite compelling. Sometimes he uses a wet washcloth; other times, he will actually use a hair brush to satiate the itching. The relief is intensely satisfying albeit short lived.

The rash has persisted despite multiple treatment attempts. Tried products include OTC moisturizers and antifungal creams, as well as prescription antifungal creams. None has had an effect.

The patient denies any other skin problems. He does recall having eczema as a child. Although that has long since resolved, he remains quite allergy prone and is particularly sensitive to airborne allergens—a trait that runs strongly in his family.

EXAMINATION

A pink, oval rash covers most of the patient’s right lateral calf. It has a thickened, faintly scaly surface that is uniform and sharply circumscribed. There is no increased warmth or tenderness on palpation. No lymph nodes can be felt in the right groin. A check of the patient’s knees, elbows, scalp, nails, and trunk show no sign of rash or other changes.

What’s the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC), previously known as neurodermatitis, is quite common but frequently misdiagnosed. Patients often report that their condition started with a bug bite or poison ivy—a provocation that gets the patient in the habit of scratching, which continues long after the initial outbreak has subsided. Thus, LSC is often associated with significant chronicity, as typified by this case.

What patients seldom understand is their own role in the perpetuation of their condition. The urge to scratch is so unbearable that few can resist it. Over time, the scratching creates more nerves that have a lower threshold for itching, and thus the itch-scratch-itch cycle is born. Many LSC patients are atopic, which predisposes them to itching in general and to xerosis especially.

The literature asserts that LSC affects the genders equally, but this ignores the fact that it can present significantly differently in men and women. This patient’s area of involvement is quite typical for men, most of whom never moisturize and for whom the lateral calf is readily accessible. In the author’s experience, the most common location for LSC in women is the nuchal scalp, where heat and sweat appear to play a role, along with ready accessibility to fingernails or the sharp end of a pencil. Other common areas of involvement include the dorsal forearms and the scrotum or vulvae.

Biopsy is seldom necessary, but if performed, it will show a marked thickening of the epidermis, orthokeratosis (normal keratinocytes about to shed), and compacted, elongated rete ridges. These and other changes effectively rule out other items in the differential (eg, psoriasis, simple eczema, fungal infection).

Stopping the itch-scratch-itch cycle with mid-strength topical steroid creams or foams is the first step in treating LSC. But then the patient must be convinced of his contribution to the treatment: leaving the affected sites alone. Truth be told, after 20 years of scratching, the best this patient can look forward to is some relief—not only from the itching, but also from concern about all the terrible things he now knows he doesn’t have.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS