User login

Foster Ownership Culture

In my June column (“Follow the Money,” p. 61), I wrote about my concern that SHM’s “2007-2008 SHM Survey: State of the Hospital Medicine Movement” showed that more than one-third of hospitalist group leaders reported they did not know their groups’ annual professional fee revenues or expenses.

This is consistent with my experience working as a consultant with many other practices, and is one of many common findings in a struggling practice.

What about the opposite side of the coin? What are the common attributes of a healthy, successful practice? I talk about this all the time with my consulting colleague, Leslie Flores (director of practice management for SHM). We’ve become convinced that while the attributes to ensure success vary a little from one practice to the next, they can be rolled into the global heading of a “culture of ownership.” That is, the practices in which hospitalists think of themselves as owners of the practice (even if they are, in fact, employees of the hospital or some other organization) are most likely to be successful.

What is it?

Ownership culture is a mind-set, not a legal description of who has contractual ownership of the practice. I learned the hard way that not everyone knows what I mean when I talk about an ownership culture.

During the course of a conference a few years ago, I had several conversations with a sharp hospitalist practice leader about the problems his group faced. Apparently, many other doctors at the hospital treated them like residents. As I learned more it sounded as though this largely was the fault of the hospitalists themselves. It seemed clear to me the underlying theme was each doctor in the practice felt little connection to his/her hospitalist colleagues and the hospital in which they worked.

I began talking with the practice leader about how things could be different if the hospitalists would think of themselves as business owners and act accordingly. Yet, he couldn’t make sense of what I was saying since he thought I was suggesting that all the hospitalists resign from employment by the hospital (and presumably give up the financial support it provided) and form their own corporation. That isn’t necessary. It is possible to maintain an ownership culture even if the hospitalists are employees of a larger organization like a hospital (and not owners of their practice in the contractual sense).

Recognize it

A Web search on “ownership culture” returns a number of interesting sites. In fact, there is a National Center for Employee Ownership, which has an interesting Web site geared toward employees who own a significant portion of their company’s stock.

You also might want to look at their article titled “What Is an Ownership Culture?” (www.nceo.org/library/ownership_culture.html) and think about how your practice fits into that description.

Leslie and I have developed an informal quiz to help hospitalist practices think about whether they are supporting an ownership mindset. While we haven’t done research to validate these measures, we have considerable anecdotal experience supporting the idea that a high score on the questionnaire (i.e., lots of answers in the “pretty much” or “100%” columns) correlates well with an ownership mentality on the part of the doctors in the practice.

We’ve found such practices usually function more effectively and have happier hospitalists and customers (e.g., hospital personnel, other doctors, and patients). If you have an idea for valuable additions, deletions, or modifications to the questionnaire I’d love to hear from you.

Does it Matter?

While there are lots of other components to a good practice, I believe an ownership culture is one of the most important features leading to a successful and thriving practice. It is difficult to maintain a successful practice for very long without it.

You don’t have to take my word for it. Writing in The Baptist Health Care Journey to Excellence, Al Stubblefield says:

“Because it is so rare, an organization that is able to create this culture of ownership within its workforce has a high probability of creating a sustainable competitive advantage … The second advantage, which came as an unexpected bonus for us, is that creating a strong, attractive culture results in incredible recruiting power.” TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

In my June column (“Follow the Money,” p. 61), I wrote about my concern that SHM’s “2007-2008 SHM Survey: State of the Hospital Medicine Movement” showed that more than one-third of hospitalist group leaders reported they did not know their groups’ annual professional fee revenues or expenses.

This is consistent with my experience working as a consultant with many other practices, and is one of many common findings in a struggling practice.

What about the opposite side of the coin? What are the common attributes of a healthy, successful practice? I talk about this all the time with my consulting colleague, Leslie Flores (director of practice management for SHM). We’ve become convinced that while the attributes to ensure success vary a little from one practice to the next, they can be rolled into the global heading of a “culture of ownership.” That is, the practices in which hospitalists think of themselves as owners of the practice (even if they are, in fact, employees of the hospital or some other organization) are most likely to be successful.

What is it?

Ownership culture is a mind-set, not a legal description of who has contractual ownership of the practice. I learned the hard way that not everyone knows what I mean when I talk about an ownership culture.

During the course of a conference a few years ago, I had several conversations with a sharp hospitalist practice leader about the problems his group faced. Apparently, many other doctors at the hospital treated them like residents. As I learned more it sounded as though this largely was the fault of the hospitalists themselves. It seemed clear to me the underlying theme was each doctor in the practice felt little connection to his/her hospitalist colleagues and the hospital in which they worked.

I began talking with the practice leader about how things could be different if the hospitalists would think of themselves as business owners and act accordingly. Yet, he couldn’t make sense of what I was saying since he thought I was suggesting that all the hospitalists resign from employment by the hospital (and presumably give up the financial support it provided) and form their own corporation. That isn’t necessary. It is possible to maintain an ownership culture even if the hospitalists are employees of a larger organization like a hospital (and not owners of their practice in the contractual sense).

Recognize it

A Web search on “ownership culture” returns a number of interesting sites. In fact, there is a National Center for Employee Ownership, which has an interesting Web site geared toward employees who own a significant portion of their company’s stock.

You also might want to look at their article titled “What Is an Ownership Culture?” (www.nceo.org/library/ownership_culture.html) and think about how your practice fits into that description.

Leslie and I have developed an informal quiz to help hospitalist practices think about whether they are supporting an ownership mindset. While we haven’t done research to validate these measures, we have considerable anecdotal experience supporting the idea that a high score on the questionnaire (i.e., lots of answers in the “pretty much” or “100%” columns) correlates well with an ownership mentality on the part of the doctors in the practice.

We’ve found such practices usually function more effectively and have happier hospitalists and customers (e.g., hospital personnel, other doctors, and patients). If you have an idea for valuable additions, deletions, or modifications to the questionnaire I’d love to hear from you.

Does it Matter?

While there are lots of other components to a good practice, I believe an ownership culture is one of the most important features leading to a successful and thriving practice. It is difficult to maintain a successful practice for very long without it.

You don’t have to take my word for it. Writing in The Baptist Health Care Journey to Excellence, Al Stubblefield says:

“Because it is so rare, an organization that is able to create this culture of ownership within its workforce has a high probability of creating a sustainable competitive advantage … The second advantage, which came as an unexpected bonus for us, is that creating a strong, attractive culture results in incredible recruiting power.” TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

In my June column (“Follow the Money,” p. 61), I wrote about my concern that SHM’s “2007-2008 SHM Survey: State of the Hospital Medicine Movement” showed that more than one-third of hospitalist group leaders reported they did not know their groups’ annual professional fee revenues or expenses.

This is consistent with my experience working as a consultant with many other practices, and is one of many common findings in a struggling practice.

What about the opposite side of the coin? What are the common attributes of a healthy, successful practice? I talk about this all the time with my consulting colleague, Leslie Flores (director of practice management for SHM). We’ve become convinced that while the attributes to ensure success vary a little from one practice to the next, they can be rolled into the global heading of a “culture of ownership.” That is, the practices in which hospitalists think of themselves as owners of the practice (even if they are, in fact, employees of the hospital or some other organization) are most likely to be successful.

What is it?

Ownership culture is a mind-set, not a legal description of who has contractual ownership of the practice. I learned the hard way that not everyone knows what I mean when I talk about an ownership culture.

During the course of a conference a few years ago, I had several conversations with a sharp hospitalist practice leader about the problems his group faced. Apparently, many other doctors at the hospital treated them like residents. As I learned more it sounded as though this largely was the fault of the hospitalists themselves. It seemed clear to me the underlying theme was each doctor in the practice felt little connection to his/her hospitalist colleagues and the hospital in which they worked.

I began talking with the practice leader about how things could be different if the hospitalists would think of themselves as business owners and act accordingly. Yet, he couldn’t make sense of what I was saying since he thought I was suggesting that all the hospitalists resign from employment by the hospital (and presumably give up the financial support it provided) and form their own corporation. That isn’t necessary. It is possible to maintain an ownership culture even if the hospitalists are employees of a larger organization like a hospital (and not owners of their practice in the contractual sense).

Recognize it

A Web search on “ownership culture” returns a number of interesting sites. In fact, there is a National Center for Employee Ownership, which has an interesting Web site geared toward employees who own a significant portion of their company’s stock.

You also might want to look at their article titled “What Is an Ownership Culture?” (www.nceo.org/library/ownership_culture.html) and think about how your practice fits into that description.

Leslie and I have developed an informal quiz to help hospitalist practices think about whether they are supporting an ownership mindset. While we haven’t done research to validate these measures, we have considerable anecdotal experience supporting the idea that a high score on the questionnaire (i.e., lots of answers in the “pretty much” or “100%” columns) correlates well with an ownership mentality on the part of the doctors in the practice.

We’ve found such practices usually function more effectively and have happier hospitalists and customers (e.g., hospital personnel, other doctors, and patients). If you have an idea for valuable additions, deletions, or modifications to the questionnaire I’d love to hear from you.

Does it Matter?

While there are lots of other components to a good practice, I believe an ownership culture is one of the most important features leading to a successful and thriving practice. It is difficult to maintain a successful practice for very long without it.

You don’t have to take my word for it. Writing in The Baptist Health Care Journey to Excellence, Al Stubblefield says:

“Because it is so rare, an organization that is able to create this culture of ownership within its workforce has a high probability of creating a sustainable competitive advantage … The second advantage, which came as an unexpected bonus for us, is that creating a strong, attractive culture results in incredible recruiting power.” TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

We’re Hiring

At the 2008 SHM Annual Meeting in San Diego, I had the pleasure of serving as moderator for a panel commenting on the opportunities and challenges faced by hospitalists. I’m not sure how well our predictions will withstand the test of time, but two things came up that I’ll discuss here:

1) Nearly every group is recruiting, and many seem to think the hospitalist shortage will last throughout the careers of those in practice today.

2) Nearly all hospitalist groups are looking for more doctors. I asked the approximately 1,600 in attendance how many are recruiting for more hospitalists. Nearly every hand in the room shot up. It was impressive; one friend (Bob Reynolds) told me he was sitting in the back and could feel a breeze in the room from all the hands being raised. Only about three hands went up when I asked how many thought their staffing was adequate.

Bear in mind that based on the show of hands nearly every group in the country is recruiting. Many groups are looking to add three to six hospitalists this year alone. This is on top of the average group growing about 20% to 25% the past two years, based on my study of data from the “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement.” The survey showed the number of FTE doctors in the average hospitalist group grew from a median six to eight hospitalists (the average went from eight to 9.7).

Hospital medicine is the fastest-growing field in the history of American medicine, and it looks like the demand for hospitalists may be increasing even faster than the supply.

I was tempted to ask for a show of hands from doctors at the meeting who were looking for a hospitalist position, but feared it could disrupt the whole conference as those seeking new doctors pounced on the potential candidates in a piranha-like feeding frenzy. So there is good news for anyone interested in joining a hospitalist group: You should have a lot of choices. If you’re recruiting, you’d better get to work to make sure you have really good plan. Let me offer a few ideas.

Never stop recruiting. Dr. Greg Mappin, VPMA at Self Regional Hospital in Greenwood, S.C., told me his philosophy is to “recruit forever, and hire when necessary.” I agree.

You should build and maintain a robust candidate pipeline by ensuring your practice maintains a high level of visibility before your best source of new doctors. The best source for most groups is the closest residency training program, though other nearby hospitalist or outpatient practices might be a secondary source of new manpower.

I suggest you engage residents by hosting a dinner near their hospital once or twice a year and inviting all second- and third-year residents to attend regardless of their interest in becoming hospitalists. You might do this even in years you may not need to add hospitalists to ensure your dinner becomes a regular event for them and to ensure they’re very familiar with your program. Some hospitals develop night and weekend moonlighting programs that employ nearby residents, which increases the chance some will join the practice upon completion of their training.

Ensure all hospitalists—especially the group leader—actively participate in recruiting. Your hospital or medical group’s physician recruiter can be a terrific asset. He/she can provide advice regarding how to find candidates, arranging interviews, etc. Yet, it is critical for the hospitalist group leader to actively communicate with every candidate, including responding to every inquiry within a day or so.

Too many group leaders make a big mistake by waiting many days to respond to new inquiries, or letting the recruiter handle all communication in advance of an interview. During the interview, be sure the candidate spends time with many of the current group members and provides contact information for every group member in case the candidate would like to call any who weren’t available on the interview day. Consider providing the candidate with a copy of the group schedule, any orientation documents you have, and other such printed materials to review after the visit.

Recruit specifically for short-term members of your practice. Despite concerns about turnover, I think it is reasonable to actively pursue candidates who may have as little as two years to work in your practice. For example, they may plan to move to another town (e.g., when their spouse finishes training) or start fellowship training. In my experience, at least half of new doctors who plan to be a hospitalist for only a year or two will choose to stay on long term.

If you want your classified ad to stand out, think about writing one that specifically targets short-term hospitalists. It could say something like: “Do you have only two years to work as a hospitalist? Then this is the place for you.” You even could add benefits, such as tuition to attend conferences that would be of value for the doctor regardless of their future specialty or practice setting. If you desperately need additional doctors, get creative in recruiting those who plan to stay with you for only a couple years. I’m confident some will end up staying long term.

Continue “recruiting” the doctors in your practice. For a number of reasons, hospitalist turnover may be higher than most other specialties. So it is particularly important to take steps to minimize it. SHM’s white paper on hospitalist career satisfaction (“A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction”) offers observations and valuable suggestions for any practice. Find it under the “Publications” link on SHM’s Web site, www. hospitalmedicine.org.

No End to Shortage

Now back to that panel discussion at SHM’s Annual Meeting in April. I asked the panelists what things would be like if in 10 years the demand for hospitalists decreased, and the supply finally caught up with and ultimately exceeded demand.

I thought this could be a provocative question that would lead to a discussion about how much of our current situation, such as recent increases in hospital financial support provided per hospitalist, are due to the current hospitalist shortage. Will hospitals decrease their support if there is ever an excess of hospitalists?

No one was buying it. Everyone was convinced that despite the incredible growth in numbers of doctors practicing as hospitalists, the demand for hospitalists will continue to grow even faster than the supply. Panelist Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, chief medical officer of Cogent Healthcare in Irvine, Calif., thought this hospitalist shortage would continue throughout our lifetime. I’m not sure how long Ron thinks he (or I) will live, but that’s a pretty bold prediction.

It looks like the current intense recruiting environment is here to stay for a long time. Every practice should be thinking about how best to manage it. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

At the 2008 SHM Annual Meeting in San Diego, I had the pleasure of serving as moderator for a panel commenting on the opportunities and challenges faced by hospitalists. I’m not sure how well our predictions will withstand the test of time, but two things came up that I’ll discuss here:

1) Nearly every group is recruiting, and many seem to think the hospitalist shortage will last throughout the careers of those in practice today.

2) Nearly all hospitalist groups are looking for more doctors. I asked the approximately 1,600 in attendance how many are recruiting for more hospitalists. Nearly every hand in the room shot up. It was impressive; one friend (Bob Reynolds) told me he was sitting in the back and could feel a breeze in the room from all the hands being raised. Only about three hands went up when I asked how many thought their staffing was adequate.

Bear in mind that based on the show of hands nearly every group in the country is recruiting. Many groups are looking to add three to six hospitalists this year alone. This is on top of the average group growing about 20% to 25% the past two years, based on my study of data from the “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement.” The survey showed the number of FTE doctors in the average hospitalist group grew from a median six to eight hospitalists (the average went from eight to 9.7).

Hospital medicine is the fastest-growing field in the history of American medicine, and it looks like the demand for hospitalists may be increasing even faster than the supply.

I was tempted to ask for a show of hands from doctors at the meeting who were looking for a hospitalist position, but feared it could disrupt the whole conference as those seeking new doctors pounced on the potential candidates in a piranha-like feeding frenzy. So there is good news for anyone interested in joining a hospitalist group: You should have a lot of choices. If you’re recruiting, you’d better get to work to make sure you have really good plan. Let me offer a few ideas.

Never stop recruiting. Dr. Greg Mappin, VPMA at Self Regional Hospital in Greenwood, S.C., told me his philosophy is to “recruit forever, and hire when necessary.” I agree.

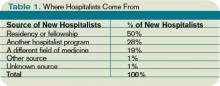

You should build and maintain a robust candidate pipeline by ensuring your practice maintains a high level of visibility before your best source of new doctors. The best source for most groups is the closest residency training program, though other nearby hospitalist or outpatient practices might be a secondary source of new manpower.

I suggest you engage residents by hosting a dinner near their hospital once or twice a year and inviting all second- and third-year residents to attend regardless of their interest in becoming hospitalists. You might do this even in years you may not need to add hospitalists to ensure your dinner becomes a regular event for them and to ensure they’re very familiar with your program. Some hospitals develop night and weekend moonlighting programs that employ nearby residents, which increases the chance some will join the practice upon completion of their training.

Ensure all hospitalists—especially the group leader—actively participate in recruiting. Your hospital or medical group’s physician recruiter can be a terrific asset. He/she can provide advice regarding how to find candidates, arranging interviews, etc. Yet, it is critical for the hospitalist group leader to actively communicate with every candidate, including responding to every inquiry within a day or so.

Too many group leaders make a big mistake by waiting many days to respond to new inquiries, or letting the recruiter handle all communication in advance of an interview. During the interview, be sure the candidate spends time with many of the current group members and provides contact information for every group member in case the candidate would like to call any who weren’t available on the interview day. Consider providing the candidate with a copy of the group schedule, any orientation documents you have, and other such printed materials to review after the visit.

Recruit specifically for short-term members of your practice. Despite concerns about turnover, I think it is reasonable to actively pursue candidates who may have as little as two years to work in your practice. For example, they may plan to move to another town (e.g., when their spouse finishes training) or start fellowship training. In my experience, at least half of new doctors who plan to be a hospitalist for only a year or two will choose to stay on long term.

If you want your classified ad to stand out, think about writing one that specifically targets short-term hospitalists. It could say something like: “Do you have only two years to work as a hospitalist? Then this is the place for you.” You even could add benefits, such as tuition to attend conferences that would be of value for the doctor regardless of their future specialty or practice setting. If you desperately need additional doctors, get creative in recruiting those who plan to stay with you for only a couple years. I’m confident some will end up staying long term.

Continue “recruiting” the doctors in your practice. For a number of reasons, hospitalist turnover may be higher than most other specialties. So it is particularly important to take steps to minimize it. SHM’s white paper on hospitalist career satisfaction (“A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction”) offers observations and valuable suggestions for any practice. Find it under the “Publications” link on SHM’s Web site, www. hospitalmedicine.org.

No End to Shortage

Now back to that panel discussion at SHM’s Annual Meeting in April. I asked the panelists what things would be like if in 10 years the demand for hospitalists decreased, and the supply finally caught up with and ultimately exceeded demand.

I thought this could be a provocative question that would lead to a discussion about how much of our current situation, such as recent increases in hospital financial support provided per hospitalist, are due to the current hospitalist shortage. Will hospitals decrease their support if there is ever an excess of hospitalists?

No one was buying it. Everyone was convinced that despite the incredible growth in numbers of doctors practicing as hospitalists, the demand for hospitalists will continue to grow even faster than the supply. Panelist Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, chief medical officer of Cogent Healthcare in Irvine, Calif., thought this hospitalist shortage would continue throughout our lifetime. I’m not sure how long Ron thinks he (or I) will live, but that’s a pretty bold prediction.

It looks like the current intense recruiting environment is here to stay for a long time. Every practice should be thinking about how best to manage it. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

At the 2008 SHM Annual Meeting in San Diego, I had the pleasure of serving as moderator for a panel commenting on the opportunities and challenges faced by hospitalists. I’m not sure how well our predictions will withstand the test of time, but two things came up that I’ll discuss here:

1) Nearly every group is recruiting, and many seem to think the hospitalist shortage will last throughout the careers of those in practice today.

2) Nearly all hospitalist groups are looking for more doctors. I asked the approximately 1,600 in attendance how many are recruiting for more hospitalists. Nearly every hand in the room shot up. It was impressive; one friend (Bob Reynolds) told me he was sitting in the back and could feel a breeze in the room from all the hands being raised. Only about three hands went up when I asked how many thought their staffing was adequate.

Bear in mind that based on the show of hands nearly every group in the country is recruiting. Many groups are looking to add three to six hospitalists this year alone. This is on top of the average group growing about 20% to 25% the past two years, based on my study of data from the “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement.” The survey showed the number of FTE doctors in the average hospitalist group grew from a median six to eight hospitalists (the average went from eight to 9.7).

Hospital medicine is the fastest-growing field in the history of American medicine, and it looks like the demand for hospitalists may be increasing even faster than the supply.

I was tempted to ask for a show of hands from doctors at the meeting who were looking for a hospitalist position, but feared it could disrupt the whole conference as those seeking new doctors pounced on the potential candidates in a piranha-like feeding frenzy. So there is good news for anyone interested in joining a hospitalist group: You should have a lot of choices. If you’re recruiting, you’d better get to work to make sure you have really good plan. Let me offer a few ideas.

Never stop recruiting. Dr. Greg Mappin, VPMA at Self Regional Hospital in Greenwood, S.C., told me his philosophy is to “recruit forever, and hire when necessary.” I agree.

You should build and maintain a robust candidate pipeline by ensuring your practice maintains a high level of visibility before your best source of new doctors. The best source for most groups is the closest residency training program, though other nearby hospitalist or outpatient practices might be a secondary source of new manpower.

I suggest you engage residents by hosting a dinner near their hospital once or twice a year and inviting all second- and third-year residents to attend regardless of their interest in becoming hospitalists. You might do this even in years you may not need to add hospitalists to ensure your dinner becomes a regular event for them and to ensure they’re very familiar with your program. Some hospitals develop night and weekend moonlighting programs that employ nearby residents, which increases the chance some will join the practice upon completion of their training.

Ensure all hospitalists—especially the group leader—actively participate in recruiting. Your hospital or medical group’s physician recruiter can be a terrific asset. He/she can provide advice regarding how to find candidates, arranging interviews, etc. Yet, it is critical for the hospitalist group leader to actively communicate with every candidate, including responding to every inquiry within a day or so.

Too many group leaders make a big mistake by waiting many days to respond to new inquiries, or letting the recruiter handle all communication in advance of an interview. During the interview, be sure the candidate spends time with many of the current group members and provides contact information for every group member in case the candidate would like to call any who weren’t available on the interview day. Consider providing the candidate with a copy of the group schedule, any orientation documents you have, and other such printed materials to review after the visit.

Recruit specifically for short-term members of your practice. Despite concerns about turnover, I think it is reasonable to actively pursue candidates who may have as little as two years to work in your practice. For example, they may plan to move to another town (e.g., when their spouse finishes training) or start fellowship training. In my experience, at least half of new doctors who plan to be a hospitalist for only a year or two will choose to stay on long term.

If you want your classified ad to stand out, think about writing one that specifically targets short-term hospitalists. It could say something like: “Do you have only two years to work as a hospitalist? Then this is the place for you.” You even could add benefits, such as tuition to attend conferences that would be of value for the doctor regardless of their future specialty or practice setting. If you desperately need additional doctors, get creative in recruiting those who plan to stay with you for only a couple years. I’m confident some will end up staying long term.

Continue “recruiting” the doctors in your practice. For a number of reasons, hospitalist turnover may be higher than most other specialties. So it is particularly important to take steps to minimize it. SHM’s white paper on hospitalist career satisfaction (“A Challenge for a New Specialty: A White Paper on Hospitalist Career Satisfaction”) offers observations and valuable suggestions for any practice. Find it under the “Publications” link on SHM’s Web site, www. hospitalmedicine.org.

No End to Shortage

Now back to that panel discussion at SHM’s Annual Meeting in April. I asked the panelists what things would be like if in 10 years the demand for hospitalists decreased, and the supply finally caught up with and ultimately exceeded demand.

I thought this could be a provocative question that would lead to a discussion about how much of our current situation, such as recent increases in hospital financial support provided per hospitalist, are due to the current hospitalist shortage. Will hospitals decrease their support if there is ever an excess of hospitalists?

No one was buying it. Everyone was convinced that despite the incredible growth in numbers of doctors practicing as hospitalists, the demand for hospitalists will continue to grow even faster than the supply. Panelist Ron Greeno, MD, FCCP, chief medical officer of Cogent Healthcare in Irvine, Calif., thought this hospitalist shortage would continue throughout our lifetime. I’m not sure how long Ron thinks he (or I) will live, but that’s a pretty bold prediction.

It looks like the current intense recruiting environment is here to stay for a long time. Every practice should be thinking about how best to manage it. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Follow the Money

I eagerly await results from SHM’s survey of hospitalist productivity and compensation every two years. I’m most curious about whether a typical hospitalist has experienced an improvement in his/her “juice to squeeze ratio” (aka compensation per unit of work).

I was pleased to see in the recently released “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement” that average hospitalist salaries increased the most for any two-year interval since we began surveying in 1997. If you haven’t seen the survey results, go to SHM’s Web site www.hospitalmedicine.org. Production remained flat, while compensation increased to an average of $188,500. (The survey showed an adjusted mean annual compensation of $193,300, and a median salary of $183,900. See complete survey for explanation regarding the adjusted mean, which refers to data for hospitalists who care for adult patients only.)

The 2008 survey has a couple of findings even more compelling than the gratifying improvement in compensation:

- 37% of HMG leaders did not know their annual expenses; and

- 35% of HMG leaders did not know their annual professional fee revenues.

Think about this for a minute. One-third of hospitalist group leaders don’t know enough about their own practice’s financial picture to know high-level details related to income and expenses. We only can presume an even larger portion of non-leader hospitalists don’t know these things about their practice.

These numbers are disconcerting, and they’re even a little worse than the numbers reported two years ago. How can this be?

Behind the Numbers

My first inclination is to look for reasons the data are misleading. Maybe some leaders chose to respond by indicating they don’t know these numbers, when in fact they do have the numbers but were just too busy to look them up and complete that part of the survey. So they might be better informed than the survey suggests, but just too busy to demonstrate it.

Or, some group leaders in large organizations, like Kaiser, may track and account for productivity and financial health in ways that differ from a typical practice. They may know a lot about their practice, but the metrics the survey asks for aren’t relevant to them.

Maybe the survey results are misleading and group leaders know a lot more about their practice financials than these numbers suggest. Well, maybe.

Unfortunately, in my consulting work up close and personal with hundreds of practices, I regularly meet group leaders who don’t see financial accountability as one of their duties. I think the survey numbers may be a reasonably accurate reflection of reality.

I typically ask group leaders things like what portion of their practice budget is funded by professional fee collections vs. payment from the hospital (or other “sponsoring organization”) and what the pro fee collection rate is. As in the survey, a large portion don’t know. They often say it’s up to someone else to keep track of those numbers and worry about the practice budget. I worry that a leader with such a hands-off approach to the practice budget can’t be very effective.

I also ask leaders things like what is their most important duty as group leader. “Making the schedule” is too often the disappointing answer. Clearly the schedule is a critical part of operating a practice, but in many practices it is reasonable, even optimal, to have a clerical person manage the schedule, or rotate responsibility for creating it among all members of the group. This frees some time the leader can spend on other activities like managing the group’s financial performance, among other things.

What Leaders Do

The ideal hospitalist practice leader’s job description will vary from place to place. It includes many things in addition to ensuring the schedule gets created. There are a handful of things that should probably be on every leader’s list. For my money, this leader should:

- Understand where the money comes from, where it goes, and what portion comes from professional fee collections vs. other sources. Also, to ensure all members of the group are updated on financial parameters regularly;

- Put in place mechanisms to ensure the hospitalists provide high-quality care to patients;

- Facilitate communication among hospitalists, hospital personnel, and medical staff to foster effective working relationships and facilitate problem-solving and conflict resolution;

- Proactively identify opportunities for the practice to enhance the service it provides to its constituents and the organization in general, and negotiating a reasonable balance between such opportunities and the practice’s resources and clinical expertise;

- Serve as a point of contact for referring primary care physicians;

- Representing the group when working and negotiating with the hospital administration; and

- Take an active role in recruitment while addressing behavior and performance issues within the practice.

Whether the leader handles these issues alone, delegates responsibility but still provides oversight, or forms a committee with other hospitalists, will vary from place to place. In every case, though, the leader should make sure these things are happening effectively.

Our field is young, and I think tends to attract people who want to avoid managing a complex practice. Perhaps it is no surprise some leaders may not be handling their job optimally. Fortunately, help is available.

Any group leader who wants to function more effectively can do several things. First, start talking to other practice leaders in your hospital. You could ask the lead doctor in another group what he/she regards as the most important components of their leadership role, and strategies that person used to become an effective leader.

Additionally, SHM has a highly regarded Leadership Academy designed to provide group leaders with the skills and resources required to successfully lead and manage a hospital medicine program now and in the future.

Each group leader should periodically step back from the day-to-day work to think about whether his/her time and energy is optimally allocated. Is the mix of clinical and administrative work reasonable? Does the leader devote time to activities (e.g., making the schedule) that could be handed off to others?

The standards used to differentiate between an effective and ineffective leader are hard to pin down and will vary a lot depending on the characteristics of a practice. Still, a comprehensive understanding of the practice’s budget and financial performance should probably be on everyone’s list. I hope the next SHM survey in late 2009 shows a lot more group leaders know things like their group’s annual expenses and revenues. We’ll see. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

I eagerly await results from SHM’s survey of hospitalist productivity and compensation every two years. I’m most curious about whether a typical hospitalist has experienced an improvement in his/her “juice to squeeze ratio” (aka compensation per unit of work).

I was pleased to see in the recently released “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement” that average hospitalist salaries increased the most for any two-year interval since we began surveying in 1997. If you haven’t seen the survey results, go to SHM’s Web site www.hospitalmedicine.org. Production remained flat, while compensation increased to an average of $188,500. (The survey showed an adjusted mean annual compensation of $193,300, and a median salary of $183,900. See complete survey for explanation regarding the adjusted mean, which refers to data for hospitalists who care for adult patients only.)

The 2008 survey has a couple of findings even more compelling than the gratifying improvement in compensation:

- 37% of HMG leaders did not know their annual expenses; and

- 35% of HMG leaders did not know their annual professional fee revenues.

Think about this for a minute. One-third of hospitalist group leaders don’t know enough about their own practice’s financial picture to know high-level details related to income and expenses. We only can presume an even larger portion of non-leader hospitalists don’t know these things about their practice.

These numbers are disconcerting, and they’re even a little worse than the numbers reported two years ago. How can this be?

Behind the Numbers

My first inclination is to look for reasons the data are misleading. Maybe some leaders chose to respond by indicating they don’t know these numbers, when in fact they do have the numbers but were just too busy to look them up and complete that part of the survey. So they might be better informed than the survey suggests, but just too busy to demonstrate it.

Or, some group leaders in large organizations, like Kaiser, may track and account for productivity and financial health in ways that differ from a typical practice. They may know a lot about their practice, but the metrics the survey asks for aren’t relevant to them.

Maybe the survey results are misleading and group leaders know a lot more about their practice financials than these numbers suggest. Well, maybe.

Unfortunately, in my consulting work up close and personal with hundreds of practices, I regularly meet group leaders who don’t see financial accountability as one of their duties. I think the survey numbers may be a reasonably accurate reflection of reality.

I typically ask group leaders things like what portion of their practice budget is funded by professional fee collections vs. payment from the hospital (or other “sponsoring organization”) and what the pro fee collection rate is. As in the survey, a large portion don’t know. They often say it’s up to someone else to keep track of those numbers and worry about the practice budget. I worry that a leader with such a hands-off approach to the practice budget can’t be very effective.

I also ask leaders things like what is their most important duty as group leader. “Making the schedule” is too often the disappointing answer. Clearly the schedule is a critical part of operating a practice, but in many practices it is reasonable, even optimal, to have a clerical person manage the schedule, or rotate responsibility for creating it among all members of the group. This frees some time the leader can spend on other activities like managing the group’s financial performance, among other things.

What Leaders Do

The ideal hospitalist practice leader’s job description will vary from place to place. It includes many things in addition to ensuring the schedule gets created. There are a handful of things that should probably be on every leader’s list. For my money, this leader should:

- Understand where the money comes from, where it goes, and what portion comes from professional fee collections vs. other sources. Also, to ensure all members of the group are updated on financial parameters regularly;

- Put in place mechanisms to ensure the hospitalists provide high-quality care to patients;

- Facilitate communication among hospitalists, hospital personnel, and medical staff to foster effective working relationships and facilitate problem-solving and conflict resolution;

- Proactively identify opportunities for the practice to enhance the service it provides to its constituents and the organization in general, and negotiating a reasonable balance between such opportunities and the practice’s resources and clinical expertise;

- Serve as a point of contact for referring primary care physicians;

- Representing the group when working and negotiating with the hospital administration; and

- Take an active role in recruitment while addressing behavior and performance issues within the practice.

Whether the leader handles these issues alone, delegates responsibility but still provides oversight, or forms a committee with other hospitalists, will vary from place to place. In every case, though, the leader should make sure these things are happening effectively.

Our field is young, and I think tends to attract people who want to avoid managing a complex practice. Perhaps it is no surprise some leaders may not be handling their job optimally. Fortunately, help is available.

Any group leader who wants to function more effectively can do several things. First, start talking to other practice leaders in your hospital. You could ask the lead doctor in another group what he/she regards as the most important components of their leadership role, and strategies that person used to become an effective leader.

Additionally, SHM has a highly regarded Leadership Academy designed to provide group leaders with the skills and resources required to successfully lead and manage a hospital medicine program now and in the future.

Each group leader should periodically step back from the day-to-day work to think about whether his/her time and energy is optimally allocated. Is the mix of clinical and administrative work reasonable? Does the leader devote time to activities (e.g., making the schedule) that could be handed off to others?

The standards used to differentiate between an effective and ineffective leader are hard to pin down and will vary a lot depending on the characteristics of a practice. Still, a comprehensive understanding of the practice’s budget and financial performance should probably be on everyone’s list. I hope the next SHM survey in late 2009 shows a lot more group leaders know things like their group’s annual expenses and revenues. We’ll see. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

I eagerly await results from SHM’s survey of hospitalist productivity and compensation every two years. I’m most curious about whether a typical hospitalist has experienced an improvement in his/her “juice to squeeze ratio” (aka compensation per unit of work).

I was pleased to see in the recently released “Society of Hospital Medicine 2007-08 Survey: The Authoritative Source on the State of the Hospitalist Movement” that average hospitalist salaries increased the most for any two-year interval since we began surveying in 1997. If you haven’t seen the survey results, go to SHM’s Web site www.hospitalmedicine.org. Production remained flat, while compensation increased to an average of $188,500. (The survey showed an adjusted mean annual compensation of $193,300, and a median salary of $183,900. See complete survey for explanation regarding the adjusted mean, which refers to data for hospitalists who care for adult patients only.)

The 2008 survey has a couple of findings even more compelling than the gratifying improvement in compensation:

- 37% of HMG leaders did not know their annual expenses; and

- 35% of HMG leaders did not know their annual professional fee revenues.

Think about this for a minute. One-third of hospitalist group leaders don’t know enough about their own practice’s financial picture to know high-level details related to income and expenses. We only can presume an even larger portion of non-leader hospitalists don’t know these things about their practice.

These numbers are disconcerting, and they’re even a little worse than the numbers reported two years ago. How can this be?

Behind the Numbers

My first inclination is to look for reasons the data are misleading. Maybe some leaders chose to respond by indicating they don’t know these numbers, when in fact they do have the numbers but were just too busy to look them up and complete that part of the survey. So they might be better informed than the survey suggests, but just too busy to demonstrate it.

Or, some group leaders in large organizations, like Kaiser, may track and account for productivity and financial health in ways that differ from a typical practice. They may know a lot about their practice, but the metrics the survey asks for aren’t relevant to them.

Maybe the survey results are misleading and group leaders know a lot more about their practice financials than these numbers suggest. Well, maybe.

Unfortunately, in my consulting work up close and personal with hundreds of practices, I regularly meet group leaders who don’t see financial accountability as one of their duties. I think the survey numbers may be a reasonably accurate reflection of reality.

I typically ask group leaders things like what portion of their practice budget is funded by professional fee collections vs. payment from the hospital (or other “sponsoring organization”) and what the pro fee collection rate is. As in the survey, a large portion don’t know. They often say it’s up to someone else to keep track of those numbers and worry about the practice budget. I worry that a leader with such a hands-off approach to the practice budget can’t be very effective.

I also ask leaders things like what is their most important duty as group leader. “Making the schedule” is too often the disappointing answer. Clearly the schedule is a critical part of operating a practice, but in many practices it is reasonable, even optimal, to have a clerical person manage the schedule, or rotate responsibility for creating it among all members of the group. This frees some time the leader can spend on other activities like managing the group’s financial performance, among other things.

What Leaders Do

The ideal hospitalist practice leader’s job description will vary from place to place. It includes many things in addition to ensuring the schedule gets created. There are a handful of things that should probably be on every leader’s list. For my money, this leader should:

- Understand where the money comes from, where it goes, and what portion comes from professional fee collections vs. other sources. Also, to ensure all members of the group are updated on financial parameters regularly;

- Put in place mechanisms to ensure the hospitalists provide high-quality care to patients;

- Facilitate communication among hospitalists, hospital personnel, and medical staff to foster effective working relationships and facilitate problem-solving and conflict resolution;

- Proactively identify opportunities for the practice to enhance the service it provides to its constituents and the organization in general, and negotiating a reasonable balance between such opportunities and the practice’s resources and clinical expertise;

- Serve as a point of contact for referring primary care physicians;

- Representing the group when working and negotiating with the hospital administration; and

- Take an active role in recruitment while addressing behavior and performance issues within the practice.

Whether the leader handles these issues alone, delegates responsibility but still provides oversight, or forms a committee with other hospitalists, will vary from place to place. In every case, though, the leader should make sure these things are happening effectively.

Our field is young, and I think tends to attract people who want to avoid managing a complex practice. Perhaps it is no surprise some leaders may not be handling their job optimally. Fortunately, help is available.

Any group leader who wants to function more effectively can do several things. First, start talking to other practice leaders in your hospital. You could ask the lead doctor in another group what he/she regards as the most important components of their leadership role, and strategies that person used to become an effective leader.

Additionally, SHM has a highly regarded Leadership Academy designed to provide group leaders with the skills and resources required to successfully lead and manage a hospital medicine program now and in the future.

Each group leader should periodically step back from the day-to-day work to think about whether his/her time and energy is optimally allocated. Is the mix of clinical and administrative work reasonable? Does the leader devote time to activities (e.g., making the schedule) that could be handed off to others?

The standards used to differentiate between an effective and ineffective leader are hard to pin down and will vary a lot depending on the characteristics of a practice. Still, a comprehensive understanding of the practice’s budget and financial performance should probably be on everyone’s list. I hope the next SHM survey in late 2009 shows a lot more group leaders know things like their group’s annual expenses and revenues. We’ll see. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Value Your Practice

The issue of practice valuation is a sensitive one. Some hospitalist practices might have significant monetary value, which could make it reasonable to ask new doctors to buy in or enable selling the practice for a profit. Still, it’s risky to assume this is the case for your practice.

Let’s examine the issue using a pair of situations I encountered not long ago. I have changed some details of the practices to more clearly illustrate a point and conceal which practices I’m describing. Both situations would have gone smoother if it was clear what the hospitalist practice was worth. But how do you assess that value?

Case No. 1

During a couple of days in 2006, I consulted with a high-performing private practice hospitalist group on the East Coast. The group was led by one of the most energetic and thoughtful leaders I’ve encountered.

Like many other private practice groups, they divided physician members of the practice into partners and non-partners (sometimes referred to as shareholder and non-shareholders in the corporation). A hospitalist who had been a full-time member of the practice for a specified period of time (two years in this case) was eligible to become partner.

This entailed a “buy-in” requiring the doctor to pay money to the practice (usually the doctor would pay using a loan from the practice, which was repaid through deductions from his/her paycheck).

For this practice, the principal benefits of partner status were having a vote in group decisions (non-partners couldn’t vote) and receiving a portion of the distribution of all corporate profits each year. These profits came from two sources:

- Money remaining after all salaries and overhead were paid; and

- Buy-in money received by the practice.

Because the partners had this “upside potential” they agreed they would cover any staff shortages by working extra shifts instead of the non-partners.

Setting things up with a buy-in to achieve partner/shareholder status seemed to make a lot of sense. After all, it is the way nearly all private-practice medical groups in other specialties are structured.

Problems soon arose when they realized there wasn’t significant “profit” available unless there happened to be two or three doctors buying into the practice in a given year.

So, the partners became disenchanted because they shouldered the burden of covering any extra shifts but didn’t get a significant profit distribution in most years. Non-partners who became eligible for partnership were choosing not to buy in because it seemed like more responsibility without more income. The group’s system began breaking down.

Keep in mind they had a terrific practice. The docs liked each other and were pleased with the group leader, were highly regarded by hospital executives and other doctors, and had a growing patient volume.

Yet, the partners were unhappy they weren’t seeing extra compensation as a reward for buying into the practice with the money, time, and effort they invested.

Despite being a desirable practice in nearly every respect, new doctors were choosing to forgo partnership status. These things were creating significant morale issues that threatened the ongoing success of the group.

So why did these problems arise?

Case No. 2

Later in 2006, I worked with a different private-practice hospitalist group out West. Their practice had been started by, and was still owned by, a “parent” medical group. As the hospitalist practice grew, everyone (hospitalists and non-hospitalist doctors in the group) agreed it made sense to have the hospitalist practice separate into its own distinct corporation. Like the practice in the first case, all parties had high regard for one another.

The problem was the non-hospitalists who invested the time and energy to start the hospitalist practice wanted the departing hospitalists to compensate the larger group.

The hospitalists could understand why the other doctors proposed a buyout but wondered what the hospitalists would get in return for paying it. The answer seemed to be not much. They weren’t confident they could recoup their investment by having future hospitalists buy in to the practice (proposing this had scared off more than one recruit), or by selling the practice to another party.

Assess Your Value

The problems faced by both these practices are a result of uncertainty about what their practices are worth.

In the first case, doctors who had the opportunity to buy into the practice were choosing not to because they believed they weren’t going to get anything in return (and had the added burden of putting themselves on the schedule more often to cover open shifts).

Likewise, in the second case the hospitalists agreed it seemed reasonable to pay the other doctors in the parent group to go out on their own. But the hospitalists worried they would never be able to recoup that money by selling shares of the practice to new partner hospitalists or selling the whole group to another entity.

It’s tricky to value any medical practice. A common approach is to put a price on tangible assets owned by the practice (e.g., buildings and equipment like computers and lab apparatus, and the accounts receivable), and the patient base (or good will) the practice has developed.

It isn’t too difficult to come up with a value for tangible assets, and most hospitalist practices have little or nothing in this category (the only hard assets I can think of that I own are my pager, stethoscope, and a couple of lab coats I never wear). Patient lists and good will are particularly difficult to place a value on. Even for a primary care practice with thousands of patient charts, there is no guarantee patients will agree to transfer their care to a purchasing doctor.

For most any kind of medical practice, including a hospitalist group, good will mainly is a function of the referral relationships doctors have developed that ensure a steady flow of patients. Since a steady flow of patients is not a problem for most hospitalist practices (too many patients is more common than too few) the value of that referral stream may not be much.

Another asset many hospitalist practices own is their contract(s) with sponsoring organizations (usually hospitals, but sometimes health plans). They provide for supplemental payments over and above professional fees the practice collects.

This is often a hospitalist practice’s most valuable asset, and it may be worth investing money to acquire. It’s the primary reason large hospitalist staffing companies are willing to pay to acquire local hospitalist practices.

Usually these contracts cannot automatically be assigned to another party without the hospital’s consent. Most hospitals’ loyalty lies with the hospitalists who provide their coverage, not with the company that may hold the contract. For example, with the hospitalists in the second case, their hospital would have been willing to immediately sign a new contract with their spin-off group to maintain their existing hospitalist coverage. The parent group’s hospital contract wasn’t worth acquiring.

All this suggests hospitalist practices may not have much monetary value. That is, an outside party probably wouldn’t pay much to buy your practice. I think this is true for the two practices I describe above. For practices like these, it is probably best to avoid having a buy-in to achieve partner status, and not diverting some practice revenue that would otherwise be used to pay salaries into a “profit” pool from which distributions are made to partners/owners periodically.

Practices Worth A Lot

I’m aware my comments might seem insulting to a group of hospitalists who have worked long and hard for several years to build what they think is a great practice. Surely it’s worth something.

Maybe your practice really does have significant value over and above the salaries the doctors earn. Perhaps you have developed proprietary operational processes that are particularly valuable and would be difficult for others to replicate without knowing your “trade secrets.” These could include things such as particularly effective ways to document, code, and collect professional fees; methods to enhance hospitalist efficiency and/or quality; unusually effective recruitment strategies; or even the ability to negotiate highly favorable contracts with payers.

Even if your practice does have remarkably effective proprietary components, you still would have to convince a buyer these valuable assets would persist after the change in ownership and the departure of key individuals. For example, you might have the best practice in the country because you’ve been able to recruit the best doctors. If I buy your practice and those excellent doctors leave, I’ve lost the unique asset that was key to the practice’s value.

Clearly there is room for a lot of debate about hospitalist practice valuation. (Search the Internet for “medical practice valuation” for a number of good articles about this.) There are many practice management companies that rely on the notion that their ideas and operations provide greater value than other practices. One such company, IPC, had a successful initial public offering of stock that found a marketplace willing to pay for its perceived value. But keep in mind that this company has many practices in many states, and much of the value may lie in the fact that the value of the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. So, unless your practice is huge and has sites in many states, I don’t think you can assume IPC’s public offering means your practice might have a similar value.

Think critically about your practice. Challenge yourself to think about what you would pay for your practice and what you would get in return. If you have a hard time coming up with clear reasons your practice has significant intangible value, you should probably avoid structuring a buy-in for new doctors or a buy-out for departing doctors. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

The issue of practice valuation is a sensitive one. Some hospitalist practices might have significant monetary value, which could make it reasonable to ask new doctors to buy in or enable selling the practice for a profit. Still, it’s risky to assume this is the case for your practice.

Let’s examine the issue using a pair of situations I encountered not long ago. I have changed some details of the practices to more clearly illustrate a point and conceal which practices I’m describing. Both situations would have gone smoother if it was clear what the hospitalist practice was worth. But how do you assess that value?

Case No. 1

During a couple of days in 2006, I consulted with a high-performing private practice hospitalist group on the East Coast. The group was led by one of the most energetic and thoughtful leaders I’ve encountered.

Like many other private practice groups, they divided physician members of the practice into partners and non-partners (sometimes referred to as shareholder and non-shareholders in the corporation). A hospitalist who had been a full-time member of the practice for a specified period of time (two years in this case) was eligible to become partner.

This entailed a “buy-in” requiring the doctor to pay money to the practice (usually the doctor would pay using a loan from the practice, which was repaid through deductions from his/her paycheck).

For this practice, the principal benefits of partner status were having a vote in group decisions (non-partners couldn’t vote) and receiving a portion of the distribution of all corporate profits each year. These profits came from two sources:

- Money remaining after all salaries and overhead were paid; and

- Buy-in money received by the practice.

Because the partners had this “upside potential” they agreed they would cover any staff shortages by working extra shifts instead of the non-partners.

Setting things up with a buy-in to achieve partner/shareholder status seemed to make a lot of sense. After all, it is the way nearly all private-practice medical groups in other specialties are structured.

Problems soon arose when they realized there wasn’t significant “profit” available unless there happened to be two or three doctors buying into the practice in a given year.

So, the partners became disenchanted because they shouldered the burden of covering any extra shifts but didn’t get a significant profit distribution in most years. Non-partners who became eligible for partnership were choosing not to buy in because it seemed like more responsibility without more income. The group’s system began breaking down.

Keep in mind they had a terrific practice. The docs liked each other and were pleased with the group leader, were highly regarded by hospital executives and other doctors, and had a growing patient volume.

Yet, the partners were unhappy they weren’t seeing extra compensation as a reward for buying into the practice with the money, time, and effort they invested.

Despite being a desirable practice in nearly every respect, new doctors were choosing to forgo partnership status. These things were creating significant morale issues that threatened the ongoing success of the group.

So why did these problems arise?

Case No. 2

Later in 2006, I worked with a different private-practice hospitalist group out West. Their practice had been started by, and was still owned by, a “parent” medical group. As the hospitalist practice grew, everyone (hospitalists and non-hospitalist doctors in the group) agreed it made sense to have the hospitalist practice separate into its own distinct corporation. Like the practice in the first case, all parties had high regard for one another.

The problem was the non-hospitalists who invested the time and energy to start the hospitalist practice wanted the departing hospitalists to compensate the larger group.

The hospitalists could understand why the other doctors proposed a buyout but wondered what the hospitalists would get in return for paying it. The answer seemed to be not much. They weren’t confident they could recoup their investment by having future hospitalists buy in to the practice (proposing this had scared off more than one recruit), or by selling the practice to another party.

Assess Your Value

The problems faced by both these practices are a result of uncertainty about what their practices are worth.

In the first case, doctors who had the opportunity to buy into the practice were choosing not to because they believed they weren’t going to get anything in return (and had the added burden of putting themselves on the schedule more often to cover open shifts).

Likewise, in the second case the hospitalists agreed it seemed reasonable to pay the other doctors in the parent group to go out on their own. But the hospitalists worried they would never be able to recoup that money by selling shares of the practice to new partner hospitalists or selling the whole group to another entity.

It’s tricky to value any medical practice. A common approach is to put a price on tangible assets owned by the practice (e.g., buildings and equipment like computers and lab apparatus, and the accounts receivable), and the patient base (or good will) the practice has developed.

It isn’t too difficult to come up with a value for tangible assets, and most hospitalist practices have little or nothing in this category (the only hard assets I can think of that I own are my pager, stethoscope, and a couple of lab coats I never wear). Patient lists and good will are particularly difficult to place a value on. Even for a primary care practice with thousands of patient charts, there is no guarantee patients will agree to transfer their care to a purchasing doctor.

For most any kind of medical practice, including a hospitalist group, good will mainly is a function of the referral relationships doctors have developed that ensure a steady flow of patients. Since a steady flow of patients is not a problem for most hospitalist practices (too many patients is more common than too few) the value of that referral stream may not be much.

Another asset many hospitalist practices own is their contract(s) with sponsoring organizations (usually hospitals, but sometimes health plans). They provide for supplemental payments over and above professional fees the practice collects.

This is often a hospitalist practice’s most valuable asset, and it may be worth investing money to acquire. It’s the primary reason large hospitalist staffing companies are willing to pay to acquire local hospitalist practices.

Usually these contracts cannot automatically be assigned to another party without the hospital’s consent. Most hospitals’ loyalty lies with the hospitalists who provide their coverage, not with the company that may hold the contract. For example, with the hospitalists in the second case, their hospital would have been willing to immediately sign a new contract with their spin-off group to maintain their existing hospitalist coverage. The parent group’s hospital contract wasn’t worth acquiring.

All this suggests hospitalist practices may not have much monetary value. That is, an outside party probably wouldn’t pay much to buy your practice. I think this is true for the two practices I describe above. For practices like these, it is probably best to avoid having a buy-in to achieve partner status, and not diverting some practice revenue that would otherwise be used to pay salaries into a “profit” pool from which distributions are made to partners/owners periodically.

Practices Worth A Lot

I’m aware my comments might seem insulting to a group of hospitalists who have worked long and hard for several years to build what they think is a great practice. Surely it’s worth something.

Maybe your practice really does have significant value over and above the salaries the doctors earn. Perhaps you have developed proprietary operational processes that are particularly valuable and would be difficult for others to replicate without knowing your “trade secrets.” These could include things such as particularly effective ways to document, code, and collect professional fees; methods to enhance hospitalist efficiency and/or quality; unusually effective recruitment strategies; or even the ability to negotiate highly favorable contracts with payers.

Even if your practice does have remarkably effective proprietary components, you still would have to convince a buyer these valuable assets would persist after the change in ownership and the departure of key individuals. For example, you might have the best practice in the country because you’ve been able to recruit the best doctors. If I buy your practice and those excellent doctors leave, I’ve lost the unique asset that was key to the practice’s value.

Clearly there is room for a lot of debate about hospitalist practice valuation. (Search the Internet for “medical practice valuation” for a number of good articles about this.) There are many practice management companies that rely on the notion that their ideas and operations provide greater value than other practices. One such company, IPC, had a successful initial public offering of stock that found a marketplace willing to pay for its perceived value. But keep in mind that this company has many practices in many states, and much of the value may lie in the fact that the value of the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. So, unless your practice is huge and has sites in many states, I don’t think you can assume IPC’s public offering means your practice might have a similar value.

Think critically about your practice. Challenge yourself to think about what you would pay for your practice and what you would get in return. If you have a hard time coming up with clear reasons your practice has significant intangible value, you should probably avoid structuring a buy-in for new doctors or a buy-out for departing doctors. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management consulting firm. He is also part of the faculty for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.