User login

Who is liable when a surgical error occurs?

CASE Surgeon accused of operating outside her scope of expertise

A 38-year-old woman (G2 P2002) presented to the emergency department (ED) with acute pelvic pain involving the right lower quadrant (RLQ). The patient had a history of stage IV endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain, primarily affecting the RLQ, that was treated by total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy 6 months earlier. Pertinent findings on physical examination included hypoactive bowel sounds and rebound tenderness. The ED physician ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, which showed no evidence of ureteral injury or other abnormality. The gynecologist who performed the surgery 6 months ago evaluated the patient in the ED.

The gynecologist decided to perform operative laparoscopy because of the severity of the patient’s pain and duration of symptoms. Informed consent obtained in the ED before the patient received analgesics included a handwritten note that said “and other indicated procedures.” The patient signed the document prior to being taken to the operating room (OR). Time out occurred in the OR before anesthesia induction. The gynecologist proceeded with laparoscopic adhesiolysis with planned appendectomy, as she was trained. A normal appendix was noted and left intact. RLQ adhesions involving the colon and abdominal wall were treated with electrosurgical cautery. When the gynecologist found adhesions between the liver and diaphragm in the right upper quadrant (RUQ), she continued adhesiolysis. However, the diaphragm was inadvertently punctured.

As the gynecologist attempted to suture the defect laparoscopically, she encountered difficulty and converted to laparotomy. Adhesions were dense and initially precluded adequate closure of the diaphragmatic defect. The gynecologist persisted and ultimately the closure was adequate; laparotomy concluded. Postoperatively, the patient was given a diagnosis of atelectasis, primarily on the right side; a chest tube was placed by the general surgery team. The patient had an uneventful postoperative period and was discharged on postoperative day 5. One month later she returned to the ED with evidence of pneumonia; she was given a diagnosis of empyema, and antibiotics were administered. She responded well and was discharged after 6 days.

The patient filed a malpractice lawsuit against the gynecologist, the hospital, and associated practitioners. The suit made 3 negligence claims: 1) the surgery was improperly performed, as evidenced by the diaphragmatic perforation; 2) the gynecologist was not adequately trained for RUQ surgery, and 3) the hospital should not have permitted RUQ surgery to proceed. The liability claim cited the lack of qualification of a gynecologic surgeon to proceed with surgical intervention near the diaphragm and the associated consequences of practicing outside the scope of expertise.

Fitz-Hugh Curtis syndrome, a complication of pelvic inflammatory disease that may cause adhesions, was raised as the initial finding at the second surgical procedure and documented as such in the operative report. The plaintiff’s counsel questioned whether surgical correction of this syndrome was within the realm of a gynecologic surgeon. The plaintiff’s counsel argued that the laparoscopic surgical procedure involved bowel and liver; diaphragmatic adhesiolysis was not indicated, especially with normal abdominal CT scan results and the absence of RUQ symptoms. The claim specified that the surgery and care, as a consequence of the RUQ adhesiolysis, resulted in atelectasis, pneumonia, and empyema, with pain and suffering. The plaintiff sought unspecified monetary damages for these results.

What’s the verdict?

The case is in negotiation prior to trial.

Legal and medical considerations

“To err is not just human but intrinsically biological and no profession is exempt from fallibility.”1

Error and liability

To err may be human, but human error is not necessarily the cause of every suboptimal medical outcome. In fact, the overall surgical complication rate has been reported at 3.4%.2 Even when there is an error, it may not have been the kind of error that gives rise to medical malpractice liability. When it comes to surgical errors, the most common are those that actually relate to medications given at surgery that appear to be more common—one recent study found that 1 in 20 perioperative medication administrations resulted in a medication error or an adverse drug event.3

Medical error vs medical malpractice

The fact is that medical error and medical malpractice (or professional negligence) are not the same thing. It is critical to understand the difference.

Medical error is the third leading cause of death in the United States.4 It is defined as “the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim,”5 or, in the Canadian literature, “an act of omission or commission in planning or execution that contributes or could contribute to an unintended result.”6 The gamut of medical errors spans (among others) problems with technique, judgment, medication administration, diagnostic and surgical errors, and incomplete record keeping.5

Negligent error, on the other hand, is generally a subset of medical error recognized by the law. It is error that occurs because of carelessness. Technically, to give rise to liability for negligence (or malpractice) there must be duty, breach, causation, and injury. That is, the physician must owe a duty to the patient, the duty must have been breached, and that breach must have caused an injury.7

Usually the duty in medical practice is that the physician must have acted as a reasonable and prudent professional would have performed under the circumstances. For the most part, malpractice is a level of practice that the profession itself would not view as reasonable practice.8 Specialists usually are held to the higher standards of the specialty. It also can be negligent to undertake practice or a procedure for which the physician is not adequately trained, or for failing to refer the patient to another more qualified physician.

The duty in medicine usually arises from the physician-patient relationship (clearly present here). It is reasonably clear in this case that there was an injury, but, in fact, the question is whether the physician acted carelessly in a way that caused that injury. Our facts leave some ambiguity—unfortunately,a common problem in the real world.

It is possible that the gynecologist was negligent in puncturing the diaphragm. It may have been carelessness, for example, in the way the procedure was performed, or in the decision to proceed despite the difficulties encountered. It is also possible that the gynecologist was not appropriately trained and experienced in the surgery that was undertaken, in which case the decision to do the surgery (rather than to refer to another physician) could well have been negligent. In either of those cases, negligence liability (malpractice) is a possibility.

Proving negligence. It is the plaintiff (the patient) who must prove the elements of negligence (including causation).8 The plaintiff will have to demonstrate not only carelessness, but that carelessness is what caused the injuries for which she is seeking compensation. In this case, the injuries are the consequence of puncturing the diaphragm. The potential damages would be the money to cover the additional medical costs and other expenses, lost wages, and noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering.

The hospital’s role in negligence

The issue of informed consent is also raised in this case, with a handwritten note prior to surgery (but the focus of this article is on medical errors). In addition to the gynecologist, the hospital and other medical personnelwere sued. The hospital is responsible for the acts of its agents, notably its employees. Even if the physicians are not technically hospital employees, the hospital may in some cases be responsible. Among other things, the hospital likely has an obligation to prevent physicians from undertaking inappropriate procedures, including those for which the physician is not appropriately trained. If the gynecologist in this case did not have privileges to perform surgery in this category, the hospital may have an obligation to not schedule the surgery or to intraoperatively question her credentials for such a procedure. In any event, the hospital will have a major role in this case and its interests may, in some instances, be inconsistent with the interests of the physician.

Why settlement discussions?

The case description ends with a note that settlement discussions were underway. If the plaintiff must prove all of the elements of negligence, why have these discussions? First, such discussions are common in almost all negligence cases. This does not mean that the case actually will be settled by the insurance company representing the physician or hospital; many malpractice cases simply fade away because the patient drops the action. Second, there are ambiguities in the facts, and it is sometimes impossible to determine whether or not a jury would find negligence. The hospital may be inclined to settle if there is any realistic chance of a jury ruling against it. Paying a small settlement may be worth avoiding high legal expenses and the risk of an adverse outcome at trial.9

Reducing medical/surgical error through a team approach

Recognizing that “human performance can be affected by many factors that include circadian rhythms, state of mind, physical health, attitude, emotions, propensity for certain common mistakes and errors, and cognitive biases,”10 health care professionals have a commitment to reduce the errors in the interest of patient safety and best practice.

The surgical environment is an opportunity to provide a team approach to patient safety. Surgical risk is a reflection of operative performance, the main factor in the development of postoperative complications.11 We wish to broaden the perspective that gynecologic surgeons, like all surgeons, must keep in mind a number of concerns that can be associated with problems related to surgical procedures, including12:

- visual perception difficulties

- stress

- loss of haptic perception (feedback using touch), as with robot-assisted procedures

- lack of situational awareness (a term we borrow from the aviation industry)

- long-term (and short-term) memory problems.

Analysis of surgical errors shows that they are related to, in order of frequency 1:

- surgical technique

- judgment

- inattention to detail

- incomplete understanding of the problem or surgical situation.

Medical errors: Caring for the second victim (you)

Patrice M. Weiss, MD

We use the term “victim” to refer to the patient and her family following a medical error. The phrase “the second victim” was coined by Dr. Albert Wu in an article in the British Medical Journal1 and describes how a clinician and team of health care professionals also can be affected by medical errors.

What signs and symptoms identify a second victim?Those suffering as a second victim may show signs of depression, loss of joy in work, and difficulty sleeping. They also may replay the events, question their own ability, and feel fearful about making another error. These reactions can lead to burnout—a serious issue that 46% of physicians report.2

As colleagues of those involved in a medical error, we should be cognizant of changes in behavior such as excessive irritability, showing up late for work, or agitation. It may be easier to recognize these symptoms in others rather than in ourselves because we often do not take time to examine how our experiences may affect us personally. Heightening awareness can help us recognize those suffering as second victims and identify the second victim symptoms in ourselves.

How can we help second victims?One challenge second victims face is not being allowed to discuss a medical error. Certainly, due to confidentiality requirements during professional liability cases, we should not talk freely about the event. However, silence creates a barrier that prevents a second victim from processing the incident.

Some hospitals offer forums to discuss medical errors, with the goal of preventing reoccurrence: morbidity and mortality conferences, morning report, Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement meetings, and root cause analyses. These forums often are not perceived by institutions’ employees in a positive way. Are they really meant to improve patient care or do they single out an individual or group in a “name/blame/shame game”? An intimidating process will only worsen a second victim’s symptoms. It is not necessary, however, to create a whole new process; it is possible to restructure, reframe, and change the culture of an existing practice.

Some institutions have developed a formalized program to help second victims. The University of Missouri has a “forYOU team,” an internal, rapid response group that provides emotional first aid to the entire team involved in a medical error case. These responders are not from human resources and do not need to be sought out; they are peers who have been educated about the struggles of the second victim. They will not discuss the case or how care was rendered; they naturally and instinctively provide emotional support to their colleagues.

At my institution, the Carilion Clinic at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, “The Trust Program” encourages truth, respectfulness, understanding, support, and transparency. All health care clinicians receive basic training, but many have volunteered for additional instruction to become mentors because they have experienced second-victim symptoms themselves.

Clinicians want assistance when dealing with a medical error. One poll reports that 90% of physicians felt that health care organizations did not adequately help them cope with the stresses associated with a medical error.3 The goal is to have all institutions recognize that clinicians can be affected by a medical error and offer support.

To hear an expanded audiocast from Dr. Weiss on “the second victim” click here.

Dr. Weiss is Professor, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, and Chief Medical Officer and Executive Vice President, Carilion Clinic, Roanoke, Virginia.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):726–727.

- Peckham C. Medscape Physician Lifestyle Report 2015. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2015/public/overview#1. Published January 26, 2015. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- White AA, Waterman AD, McCotter P, Boyle DJ, Gallagher TH. Supporting health care workers after medical error: considerations for health care leaders. JCOM. 2008;15(5):240–247.

“Inadequacy” with regard to surgical proceduresIndication for surgery is intrinsic to provision of appropriate care. Surgery inherently poses the possibility of unexpected problems. Adequate training and skill, therefore, must include the ability to deal with a range of problems that arise in the course of surgery. The spectrum related to inadequacy as related to surgical problems includes “failed surgery,” defined as “if despite the utmost care of everyone involved and with the responsible consideration of all knowledge, the designed aim is not achieved, surgery by itself has failed.”5 Of paramount importance is the surgeon’s knowledge of technology and the ability to troubleshoot, as well as the OR team’s responsibility for proper maintenance of equipment to ensure optimal functionality.1

Aviation industry studies indicate that “high performing cockpit crews have been shown to devote one third of their communications to discuss threats and mistakes in their environment, while poor performing teams devoted much less, about 5%, of their time to such.”1,13 A well-trained and well-motivated OR nursing team has been equated with reduction in operative time and rate of conversion to laparotomy.14 Outdated instruments may also contribute to surgical errors.1

Moving the “learning curve” out of the OR and into the simulation lab remains valuable, which is also confirmed by the aviation industry.15 The significance of loss of haptic perception continues to be debated between laparoscopic (straight-stick) surgeons and those performing robotic approaches. Does haptic perception play a major role in surgical intervention? Most surgeons do not view loss of haptic perception, as with minimally invasive procedures, as a major impediment to successful surgery. From the legal perspective, loss of haptic perception has not been well addressed.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has focused on patient safety in the surgical environment including concerns for wrong-patient surgery, wrong-side surgery, wrong-level surgery, and wrong-part surgery.16 The Joint Commission has identified factors that may enhance the risk of wrong-site surgery: multiple surgeons involved in the case, multiple procedures during a single surgical visit, unusual time pressures to start or complete the surgery, and unusual physical characteristics including morbid obesity or physical deformity.16

10 starting points for medical error preventionSo what are we to do? Consider:

- Using a preprocedure verification checklist.

- Marking the operative site.

- Completing a time out process prior to starting the procedure, according to the Joint Commission protocol. [For more information on Joint Commission-recommended time out protocols and ways to prevent medical errors, click here.]

- Involving the patient in the identification and procedure definition process. (This is an important part of informed consent.)

- Providing appropriate proctoring and sign-off for new procedures and technology.

- Avoiding sleep deprivation situations, especially with regard to emergency procedures.

- Using only radiopaque-labeled materials placed into the operating cavity.

- Considering medication effect on a fetus, if applicable.

- Reducing distractions from pagers, telephone calls, etc.

- Maintaining a “sterile cockpit” (or distraction free) environment for everyone in the OR.

Set the stage for best outcomesA true team approach is an excellent modus operandi before, during, and after surgery,setting the stage for best outcomes for patients.

“As human beings, surgeons will commit errors and for this reason they have to adopt and utilize stringent defense systems to minimize the incidence of these adverse events … Transparency is the first step on the way to a new safety culture with the acknowledgement of errors when they occur with adoption of systems destined to establish their cause and future prevention.”1

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Galleano R, Franceschi A, Ciciliot M, Falchero F, Cuschieri A. Errors in laparoscopic surgery: what surgeons should know. Mineva Chir. 2011;66(2):107−117.

- Fabri P, Zyas-Castro J. Human error, not communication and systems, underlies surgical complications. Surgery. 2008;144(4):557−565.

- Nanji KC, Patel A, Shaikh S, Seger DL, Bates DW. Evaluation of perioperative medication errors and adverse drug events. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(1):25−34.

- Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error−the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2139. Balogun J, Bramall A, Berstein M. How surgical trainees handle catastrophic errors: a qualitative study. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1179−1184.

- Grober E, Bohnen J. Defining medical error. Can J Surg. 2005;48(1):39−44.

- Anderson RE, ed. Medical Malpractice: A Physician's Sourcebook. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, Inc; 2004.

- Mehlman MJ. Professional power and the standard of care in medicine. 44 Arizona State Law J. 2012;44:1165−1777. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2205485. Revised February 13, 2013.

- Hyman DA, Silver C. On the table: an examination of medical malpractice, litigation, and methods of reform: healthcare quality, patient safety, and the culture of medicine: "Denial Ain't Just a River in Egypt." New Eng Law Rev. 2012;46:417−931.

- Landers R. Reducing surgical errors: implementing a three-hinge approach to success. AORN J. 2015;101(6):657−665.

- Pettigrew R, Burns H, Carter D. Evaluating surgical risk: the importance of technical factors in determining outcome. Br J Surg. 1987;74(9):791−794.

- Parker W. Understanding errors during laparoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2010;37(3):437−449.

- Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Analyzing cockpit communications: the links between language, performance, error, and workload. Hum Perf Extrem Environ. 2000;5(1):63−68.

- Kenyon T, Lenker M, Bax R, Swanstrom L. Cost and benefit of the trained laparoscopic team: a comparative study of a designated nursing team vs. a non-trained team. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(8):812−814.

- Woodman R. Surgeons should train like pilots. BMJ. 1999;319:1321.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 464: Patient safety in the surgical environment. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):786−790.

CASE Surgeon accused of operating outside her scope of expertise

A 38-year-old woman (G2 P2002) presented to the emergency department (ED) with acute pelvic pain involving the right lower quadrant (RLQ). The patient had a history of stage IV endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain, primarily affecting the RLQ, that was treated by total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy 6 months earlier. Pertinent findings on physical examination included hypoactive bowel sounds and rebound tenderness. The ED physician ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, which showed no evidence of ureteral injury or other abnormality. The gynecologist who performed the surgery 6 months ago evaluated the patient in the ED.

The gynecologist decided to perform operative laparoscopy because of the severity of the patient’s pain and duration of symptoms. Informed consent obtained in the ED before the patient received analgesics included a handwritten note that said “and other indicated procedures.” The patient signed the document prior to being taken to the operating room (OR). Time out occurred in the OR before anesthesia induction. The gynecologist proceeded with laparoscopic adhesiolysis with planned appendectomy, as she was trained. A normal appendix was noted and left intact. RLQ adhesions involving the colon and abdominal wall were treated with electrosurgical cautery. When the gynecologist found adhesions between the liver and diaphragm in the right upper quadrant (RUQ), she continued adhesiolysis. However, the diaphragm was inadvertently punctured.

As the gynecologist attempted to suture the defect laparoscopically, she encountered difficulty and converted to laparotomy. Adhesions were dense and initially precluded adequate closure of the diaphragmatic defect. The gynecologist persisted and ultimately the closure was adequate; laparotomy concluded. Postoperatively, the patient was given a diagnosis of atelectasis, primarily on the right side; a chest tube was placed by the general surgery team. The patient had an uneventful postoperative period and was discharged on postoperative day 5. One month later she returned to the ED with evidence of pneumonia; she was given a diagnosis of empyema, and antibiotics were administered. She responded well and was discharged after 6 days.

The patient filed a malpractice lawsuit against the gynecologist, the hospital, and associated practitioners. The suit made 3 negligence claims: 1) the surgery was improperly performed, as evidenced by the diaphragmatic perforation; 2) the gynecologist was not adequately trained for RUQ surgery, and 3) the hospital should not have permitted RUQ surgery to proceed. The liability claim cited the lack of qualification of a gynecologic surgeon to proceed with surgical intervention near the diaphragm and the associated consequences of practicing outside the scope of expertise.

Fitz-Hugh Curtis syndrome, a complication of pelvic inflammatory disease that may cause adhesions, was raised as the initial finding at the second surgical procedure and documented as such in the operative report. The plaintiff’s counsel questioned whether surgical correction of this syndrome was within the realm of a gynecologic surgeon. The plaintiff’s counsel argued that the laparoscopic surgical procedure involved bowel and liver; diaphragmatic adhesiolysis was not indicated, especially with normal abdominal CT scan results and the absence of RUQ symptoms. The claim specified that the surgery and care, as a consequence of the RUQ adhesiolysis, resulted in atelectasis, pneumonia, and empyema, with pain and suffering. The plaintiff sought unspecified monetary damages for these results.

What’s the verdict?

The case is in negotiation prior to trial.

Legal and medical considerations

“To err is not just human but intrinsically biological and no profession is exempt from fallibility.”1

Error and liability

To err may be human, but human error is not necessarily the cause of every suboptimal medical outcome. In fact, the overall surgical complication rate has been reported at 3.4%.2 Even when there is an error, it may not have been the kind of error that gives rise to medical malpractice liability. When it comes to surgical errors, the most common are those that actually relate to medications given at surgery that appear to be more common—one recent study found that 1 in 20 perioperative medication administrations resulted in a medication error or an adverse drug event.3

Medical error vs medical malpractice

The fact is that medical error and medical malpractice (or professional negligence) are not the same thing. It is critical to understand the difference.

Medical error is the third leading cause of death in the United States.4 It is defined as “the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim,”5 or, in the Canadian literature, “an act of omission or commission in planning or execution that contributes or could contribute to an unintended result.”6 The gamut of medical errors spans (among others) problems with technique, judgment, medication administration, diagnostic and surgical errors, and incomplete record keeping.5

Negligent error, on the other hand, is generally a subset of medical error recognized by the law. It is error that occurs because of carelessness. Technically, to give rise to liability for negligence (or malpractice) there must be duty, breach, causation, and injury. That is, the physician must owe a duty to the patient, the duty must have been breached, and that breach must have caused an injury.7

Usually the duty in medical practice is that the physician must have acted as a reasonable and prudent professional would have performed under the circumstances. For the most part, malpractice is a level of practice that the profession itself would not view as reasonable practice.8 Specialists usually are held to the higher standards of the specialty. It also can be negligent to undertake practice or a procedure for which the physician is not adequately trained, or for failing to refer the patient to another more qualified physician.

The duty in medicine usually arises from the physician-patient relationship (clearly present here). It is reasonably clear in this case that there was an injury, but, in fact, the question is whether the physician acted carelessly in a way that caused that injury. Our facts leave some ambiguity—unfortunately,a common problem in the real world.

It is possible that the gynecologist was negligent in puncturing the diaphragm. It may have been carelessness, for example, in the way the procedure was performed, or in the decision to proceed despite the difficulties encountered. It is also possible that the gynecologist was not appropriately trained and experienced in the surgery that was undertaken, in which case the decision to do the surgery (rather than to refer to another physician) could well have been negligent. In either of those cases, negligence liability (malpractice) is a possibility.

Proving negligence. It is the plaintiff (the patient) who must prove the elements of negligence (including causation).8 The plaintiff will have to demonstrate not only carelessness, but that carelessness is what caused the injuries for which she is seeking compensation. In this case, the injuries are the consequence of puncturing the diaphragm. The potential damages would be the money to cover the additional medical costs and other expenses, lost wages, and noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering.

The hospital’s role in negligence

The issue of informed consent is also raised in this case, with a handwritten note prior to surgery (but the focus of this article is on medical errors). In addition to the gynecologist, the hospital and other medical personnelwere sued. The hospital is responsible for the acts of its agents, notably its employees. Even if the physicians are not technically hospital employees, the hospital may in some cases be responsible. Among other things, the hospital likely has an obligation to prevent physicians from undertaking inappropriate procedures, including those for which the physician is not appropriately trained. If the gynecologist in this case did not have privileges to perform surgery in this category, the hospital may have an obligation to not schedule the surgery or to intraoperatively question her credentials for such a procedure. In any event, the hospital will have a major role in this case and its interests may, in some instances, be inconsistent with the interests of the physician.

Why settlement discussions?

The case description ends with a note that settlement discussions were underway. If the plaintiff must prove all of the elements of negligence, why have these discussions? First, such discussions are common in almost all negligence cases. This does not mean that the case actually will be settled by the insurance company representing the physician or hospital; many malpractice cases simply fade away because the patient drops the action. Second, there are ambiguities in the facts, and it is sometimes impossible to determine whether or not a jury would find negligence. The hospital may be inclined to settle if there is any realistic chance of a jury ruling against it. Paying a small settlement may be worth avoiding high legal expenses and the risk of an adverse outcome at trial.9

Reducing medical/surgical error through a team approach

Recognizing that “human performance can be affected by many factors that include circadian rhythms, state of mind, physical health, attitude, emotions, propensity for certain common mistakes and errors, and cognitive biases,”10 health care professionals have a commitment to reduce the errors in the interest of patient safety and best practice.

The surgical environment is an opportunity to provide a team approach to patient safety. Surgical risk is a reflection of operative performance, the main factor in the development of postoperative complications.11 We wish to broaden the perspective that gynecologic surgeons, like all surgeons, must keep in mind a number of concerns that can be associated with problems related to surgical procedures, including12:

- visual perception difficulties

- stress

- loss of haptic perception (feedback using touch), as with robot-assisted procedures

- lack of situational awareness (a term we borrow from the aviation industry)

- long-term (and short-term) memory problems.

Analysis of surgical errors shows that they are related to, in order of frequency 1:

- surgical technique

- judgment

- inattention to detail

- incomplete understanding of the problem or surgical situation.

Medical errors: Caring for the second victim (you)

Patrice M. Weiss, MD

We use the term “victim” to refer to the patient and her family following a medical error. The phrase “the second victim” was coined by Dr. Albert Wu in an article in the British Medical Journal1 and describes how a clinician and team of health care professionals also can be affected by medical errors.

What signs and symptoms identify a second victim?Those suffering as a second victim may show signs of depression, loss of joy in work, and difficulty sleeping. They also may replay the events, question their own ability, and feel fearful about making another error. These reactions can lead to burnout—a serious issue that 46% of physicians report.2

As colleagues of those involved in a medical error, we should be cognizant of changes in behavior such as excessive irritability, showing up late for work, or agitation. It may be easier to recognize these symptoms in others rather than in ourselves because we often do not take time to examine how our experiences may affect us personally. Heightening awareness can help us recognize those suffering as second victims and identify the second victim symptoms in ourselves.

How can we help second victims?One challenge second victims face is not being allowed to discuss a medical error. Certainly, due to confidentiality requirements during professional liability cases, we should not talk freely about the event. However, silence creates a barrier that prevents a second victim from processing the incident.

Some hospitals offer forums to discuss medical errors, with the goal of preventing reoccurrence: morbidity and mortality conferences, morning report, Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement meetings, and root cause analyses. These forums often are not perceived by institutions’ employees in a positive way. Are they really meant to improve patient care or do they single out an individual or group in a “name/blame/shame game”? An intimidating process will only worsen a second victim’s symptoms. It is not necessary, however, to create a whole new process; it is possible to restructure, reframe, and change the culture of an existing practice.

Some institutions have developed a formalized program to help second victims. The University of Missouri has a “forYOU team,” an internal, rapid response group that provides emotional first aid to the entire team involved in a medical error case. These responders are not from human resources and do not need to be sought out; they are peers who have been educated about the struggles of the second victim. They will not discuss the case or how care was rendered; they naturally and instinctively provide emotional support to their colleagues.

At my institution, the Carilion Clinic at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, “The Trust Program” encourages truth, respectfulness, understanding, support, and transparency. All health care clinicians receive basic training, but many have volunteered for additional instruction to become mentors because they have experienced second-victim symptoms themselves.

Clinicians want assistance when dealing with a medical error. One poll reports that 90% of physicians felt that health care organizations did not adequately help them cope with the stresses associated with a medical error.3 The goal is to have all institutions recognize that clinicians can be affected by a medical error and offer support.

To hear an expanded audiocast from Dr. Weiss on “the second victim” click here.

Dr. Weiss is Professor, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, and Chief Medical Officer and Executive Vice President, Carilion Clinic, Roanoke, Virginia.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):726–727.

- Peckham C. Medscape Physician Lifestyle Report 2015. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2015/public/overview#1. Published January 26, 2015. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- White AA, Waterman AD, McCotter P, Boyle DJ, Gallagher TH. Supporting health care workers after medical error: considerations for health care leaders. JCOM. 2008;15(5):240–247.

“Inadequacy” with regard to surgical proceduresIndication for surgery is intrinsic to provision of appropriate care. Surgery inherently poses the possibility of unexpected problems. Adequate training and skill, therefore, must include the ability to deal with a range of problems that arise in the course of surgery. The spectrum related to inadequacy as related to surgical problems includes “failed surgery,” defined as “if despite the utmost care of everyone involved and with the responsible consideration of all knowledge, the designed aim is not achieved, surgery by itself has failed.”5 Of paramount importance is the surgeon’s knowledge of technology and the ability to troubleshoot, as well as the OR team’s responsibility for proper maintenance of equipment to ensure optimal functionality.1

Aviation industry studies indicate that “high performing cockpit crews have been shown to devote one third of their communications to discuss threats and mistakes in their environment, while poor performing teams devoted much less, about 5%, of their time to such.”1,13 A well-trained and well-motivated OR nursing team has been equated with reduction in operative time and rate of conversion to laparotomy.14 Outdated instruments may also contribute to surgical errors.1

Moving the “learning curve” out of the OR and into the simulation lab remains valuable, which is also confirmed by the aviation industry.15 The significance of loss of haptic perception continues to be debated between laparoscopic (straight-stick) surgeons and those performing robotic approaches. Does haptic perception play a major role in surgical intervention? Most surgeons do not view loss of haptic perception, as with minimally invasive procedures, as a major impediment to successful surgery. From the legal perspective, loss of haptic perception has not been well addressed.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has focused on patient safety in the surgical environment including concerns for wrong-patient surgery, wrong-side surgery, wrong-level surgery, and wrong-part surgery.16 The Joint Commission has identified factors that may enhance the risk of wrong-site surgery: multiple surgeons involved in the case, multiple procedures during a single surgical visit, unusual time pressures to start or complete the surgery, and unusual physical characteristics including morbid obesity or physical deformity.16

10 starting points for medical error preventionSo what are we to do? Consider:

- Using a preprocedure verification checklist.

- Marking the operative site.

- Completing a time out process prior to starting the procedure, according to the Joint Commission protocol. [For more information on Joint Commission-recommended time out protocols and ways to prevent medical errors, click here.]

- Involving the patient in the identification and procedure definition process. (This is an important part of informed consent.)

- Providing appropriate proctoring and sign-off for new procedures and technology.

- Avoiding sleep deprivation situations, especially with regard to emergency procedures.

- Using only radiopaque-labeled materials placed into the operating cavity.

- Considering medication effect on a fetus, if applicable.

- Reducing distractions from pagers, telephone calls, etc.

- Maintaining a “sterile cockpit” (or distraction free) environment for everyone in the OR.

Set the stage for best outcomesA true team approach is an excellent modus operandi before, during, and after surgery,setting the stage for best outcomes for patients.

“As human beings, surgeons will commit errors and for this reason they have to adopt and utilize stringent defense systems to minimize the incidence of these adverse events … Transparency is the first step on the way to a new safety culture with the acknowledgement of errors when they occur with adoption of systems destined to establish their cause and future prevention.”1

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Surgeon accused of operating outside her scope of expertise

A 38-year-old woman (G2 P2002) presented to the emergency department (ED) with acute pelvic pain involving the right lower quadrant (RLQ). The patient had a history of stage IV endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain, primarily affecting the RLQ, that was treated by total laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy 6 months earlier. Pertinent findings on physical examination included hypoactive bowel sounds and rebound tenderness. The ED physician ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen, which showed no evidence of ureteral injury or other abnormality. The gynecologist who performed the surgery 6 months ago evaluated the patient in the ED.

The gynecologist decided to perform operative laparoscopy because of the severity of the patient’s pain and duration of symptoms. Informed consent obtained in the ED before the patient received analgesics included a handwritten note that said “and other indicated procedures.” The patient signed the document prior to being taken to the operating room (OR). Time out occurred in the OR before anesthesia induction. The gynecologist proceeded with laparoscopic adhesiolysis with planned appendectomy, as she was trained. A normal appendix was noted and left intact. RLQ adhesions involving the colon and abdominal wall were treated with electrosurgical cautery. When the gynecologist found adhesions between the liver and diaphragm in the right upper quadrant (RUQ), she continued adhesiolysis. However, the diaphragm was inadvertently punctured.

As the gynecologist attempted to suture the defect laparoscopically, she encountered difficulty and converted to laparotomy. Adhesions were dense and initially precluded adequate closure of the diaphragmatic defect. The gynecologist persisted and ultimately the closure was adequate; laparotomy concluded. Postoperatively, the patient was given a diagnosis of atelectasis, primarily on the right side; a chest tube was placed by the general surgery team. The patient had an uneventful postoperative period and was discharged on postoperative day 5. One month later she returned to the ED with evidence of pneumonia; she was given a diagnosis of empyema, and antibiotics were administered. She responded well and was discharged after 6 days.

The patient filed a malpractice lawsuit against the gynecologist, the hospital, and associated practitioners. The suit made 3 negligence claims: 1) the surgery was improperly performed, as evidenced by the diaphragmatic perforation; 2) the gynecologist was not adequately trained for RUQ surgery, and 3) the hospital should not have permitted RUQ surgery to proceed. The liability claim cited the lack of qualification of a gynecologic surgeon to proceed with surgical intervention near the diaphragm and the associated consequences of practicing outside the scope of expertise.

Fitz-Hugh Curtis syndrome, a complication of pelvic inflammatory disease that may cause adhesions, was raised as the initial finding at the second surgical procedure and documented as such in the operative report. The plaintiff’s counsel questioned whether surgical correction of this syndrome was within the realm of a gynecologic surgeon. The plaintiff’s counsel argued that the laparoscopic surgical procedure involved bowel and liver; diaphragmatic adhesiolysis was not indicated, especially with normal abdominal CT scan results and the absence of RUQ symptoms. The claim specified that the surgery and care, as a consequence of the RUQ adhesiolysis, resulted in atelectasis, pneumonia, and empyema, with pain and suffering. The plaintiff sought unspecified monetary damages for these results.

What’s the verdict?

The case is in negotiation prior to trial.

Legal and medical considerations

“To err is not just human but intrinsically biological and no profession is exempt from fallibility.”1

Error and liability

To err may be human, but human error is not necessarily the cause of every suboptimal medical outcome. In fact, the overall surgical complication rate has been reported at 3.4%.2 Even when there is an error, it may not have been the kind of error that gives rise to medical malpractice liability. When it comes to surgical errors, the most common are those that actually relate to medications given at surgery that appear to be more common—one recent study found that 1 in 20 perioperative medication administrations resulted in a medication error or an adverse drug event.3

Medical error vs medical malpractice

The fact is that medical error and medical malpractice (or professional negligence) are not the same thing. It is critical to understand the difference.

Medical error is the third leading cause of death in the United States.4 It is defined as “the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim,”5 or, in the Canadian literature, “an act of omission or commission in planning or execution that contributes or could contribute to an unintended result.”6 The gamut of medical errors spans (among others) problems with technique, judgment, medication administration, diagnostic and surgical errors, and incomplete record keeping.5

Negligent error, on the other hand, is generally a subset of medical error recognized by the law. It is error that occurs because of carelessness. Technically, to give rise to liability for negligence (or malpractice) there must be duty, breach, causation, and injury. That is, the physician must owe a duty to the patient, the duty must have been breached, and that breach must have caused an injury.7

Usually the duty in medical practice is that the physician must have acted as a reasonable and prudent professional would have performed under the circumstances. For the most part, malpractice is a level of practice that the profession itself would not view as reasonable practice.8 Specialists usually are held to the higher standards of the specialty. It also can be negligent to undertake practice or a procedure for which the physician is not adequately trained, or for failing to refer the patient to another more qualified physician.

The duty in medicine usually arises from the physician-patient relationship (clearly present here). It is reasonably clear in this case that there was an injury, but, in fact, the question is whether the physician acted carelessly in a way that caused that injury. Our facts leave some ambiguity—unfortunately,a common problem in the real world.

It is possible that the gynecologist was negligent in puncturing the diaphragm. It may have been carelessness, for example, in the way the procedure was performed, or in the decision to proceed despite the difficulties encountered. It is also possible that the gynecologist was not appropriately trained and experienced in the surgery that was undertaken, in which case the decision to do the surgery (rather than to refer to another physician) could well have been negligent. In either of those cases, negligence liability (malpractice) is a possibility.

Proving negligence. It is the plaintiff (the patient) who must prove the elements of negligence (including causation).8 The plaintiff will have to demonstrate not only carelessness, but that carelessness is what caused the injuries for which she is seeking compensation. In this case, the injuries are the consequence of puncturing the diaphragm. The potential damages would be the money to cover the additional medical costs and other expenses, lost wages, and noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering.

The hospital’s role in negligence

The issue of informed consent is also raised in this case, with a handwritten note prior to surgery (but the focus of this article is on medical errors). In addition to the gynecologist, the hospital and other medical personnelwere sued. The hospital is responsible for the acts of its agents, notably its employees. Even if the physicians are not technically hospital employees, the hospital may in some cases be responsible. Among other things, the hospital likely has an obligation to prevent physicians from undertaking inappropriate procedures, including those for which the physician is not appropriately trained. If the gynecologist in this case did not have privileges to perform surgery in this category, the hospital may have an obligation to not schedule the surgery or to intraoperatively question her credentials for such a procedure. In any event, the hospital will have a major role in this case and its interests may, in some instances, be inconsistent with the interests of the physician.

Why settlement discussions?

The case description ends with a note that settlement discussions were underway. If the plaintiff must prove all of the elements of negligence, why have these discussions? First, such discussions are common in almost all negligence cases. This does not mean that the case actually will be settled by the insurance company representing the physician or hospital; many malpractice cases simply fade away because the patient drops the action. Second, there are ambiguities in the facts, and it is sometimes impossible to determine whether or not a jury would find negligence. The hospital may be inclined to settle if there is any realistic chance of a jury ruling against it. Paying a small settlement may be worth avoiding high legal expenses and the risk of an adverse outcome at trial.9

Reducing medical/surgical error through a team approach

Recognizing that “human performance can be affected by many factors that include circadian rhythms, state of mind, physical health, attitude, emotions, propensity for certain common mistakes and errors, and cognitive biases,”10 health care professionals have a commitment to reduce the errors in the interest of patient safety and best practice.

The surgical environment is an opportunity to provide a team approach to patient safety. Surgical risk is a reflection of operative performance, the main factor in the development of postoperative complications.11 We wish to broaden the perspective that gynecologic surgeons, like all surgeons, must keep in mind a number of concerns that can be associated with problems related to surgical procedures, including12:

- visual perception difficulties

- stress

- loss of haptic perception (feedback using touch), as with robot-assisted procedures

- lack of situational awareness (a term we borrow from the aviation industry)

- long-term (and short-term) memory problems.

Analysis of surgical errors shows that they are related to, in order of frequency 1:

- surgical technique

- judgment

- inattention to detail

- incomplete understanding of the problem or surgical situation.

Medical errors: Caring for the second victim (you)

Patrice M. Weiss, MD

We use the term “victim” to refer to the patient and her family following a medical error. The phrase “the second victim” was coined by Dr. Albert Wu in an article in the British Medical Journal1 and describes how a clinician and team of health care professionals also can be affected by medical errors.

What signs and symptoms identify a second victim?Those suffering as a second victim may show signs of depression, loss of joy in work, and difficulty sleeping. They also may replay the events, question their own ability, and feel fearful about making another error. These reactions can lead to burnout—a serious issue that 46% of physicians report.2

As colleagues of those involved in a medical error, we should be cognizant of changes in behavior such as excessive irritability, showing up late for work, or agitation. It may be easier to recognize these symptoms in others rather than in ourselves because we often do not take time to examine how our experiences may affect us personally. Heightening awareness can help us recognize those suffering as second victims and identify the second victim symptoms in ourselves.

How can we help second victims?One challenge second victims face is not being allowed to discuss a medical error. Certainly, due to confidentiality requirements during professional liability cases, we should not talk freely about the event. However, silence creates a barrier that prevents a second victim from processing the incident.

Some hospitals offer forums to discuss medical errors, with the goal of preventing reoccurrence: morbidity and mortality conferences, morning report, Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement meetings, and root cause analyses. These forums often are not perceived by institutions’ employees in a positive way. Are they really meant to improve patient care or do they single out an individual or group in a “name/blame/shame game”? An intimidating process will only worsen a second victim’s symptoms. It is not necessary, however, to create a whole new process; it is possible to restructure, reframe, and change the culture of an existing practice.

Some institutions have developed a formalized program to help second victims. The University of Missouri has a “forYOU team,” an internal, rapid response group that provides emotional first aid to the entire team involved in a medical error case. These responders are not from human resources and do not need to be sought out; they are peers who have been educated about the struggles of the second victim. They will not discuss the case or how care was rendered; they naturally and instinctively provide emotional support to their colleagues.

At my institution, the Carilion Clinic at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, “The Trust Program” encourages truth, respectfulness, understanding, support, and transparency. All health care clinicians receive basic training, but many have volunteered for additional instruction to become mentors because they have experienced second-victim symptoms themselves.

Clinicians want assistance when dealing with a medical error. One poll reports that 90% of physicians felt that health care organizations did not adequately help them cope with the stresses associated with a medical error.3 The goal is to have all institutions recognize that clinicians can be affected by a medical error and offer support.

To hear an expanded audiocast from Dr. Weiss on “the second victim” click here.

Dr. Weiss is Professor, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, and Chief Medical Officer and Executive Vice President, Carilion Clinic, Roanoke, Virginia.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

References

- Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):726–727.

- Peckham C. Medscape Physician Lifestyle Report 2015. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2015/public/overview#1. Published January 26, 2015. Accessed May 24, 2016.

- White AA, Waterman AD, McCotter P, Boyle DJ, Gallagher TH. Supporting health care workers after medical error: considerations for health care leaders. JCOM. 2008;15(5):240–247.

“Inadequacy” with regard to surgical proceduresIndication for surgery is intrinsic to provision of appropriate care. Surgery inherently poses the possibility of unexpected problems. Adequate training and skill, therefore, must include the ability to deal with a range of problems that arise in the course of surgery. The spectrum related to inadequacy as related to surgical problems includes “failed surgery,” defined as “if despite the utmost care of everyone involved and with the responsible consideration of all knowledge, the designed aim is not achieved, surgery by itself has failed.”5 Of paramount importance is the surgeon’s knowledge of technology and the ability to troubleshoot, as well as the OR team’s responsibility for proper maintenance of equipment to ensure optimal functionality.1

Aviation industry studies indicate that “high performing cockpit crews have been shown to devote one third of their communications to discuss threats and mistakes in their environment, while poor performing teams devoted much less, about 5%, of their time to such.”1,13 A well-trained and well-motivated OR nursing team has been equated with reduction in operative time and rate of conversion to laparotomy.14 Outdated instruments may also contribute to surgical errors.1

Moving the “learning curve” out of the OR and into the simulation lab remains valuable, which is also confirmed by the aviation industry.15 The significance of loss of haptic perception continues to be debated between laparoscopic (straight-stick) surgeons and those performing robotic approaches. Does haptic perception play a major role in surgical intervention? Most surgeons do not view loss of haptic perception, as with minimally invasive procedures, as a major impediment to successful surgery. From the legal perspective, loss of haptic perception has not been well addressed.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has focused on patient safety in the surgical environment including concerns for wrong-patient surgery, wrong-side surgery, wrong-level surgery, and wrong-part surgery.16 The Joint Commission has identified factors that may enhance the risk of wrong-site surgery: multiple surgeons involved in the case, multiple procedures during a single surgical visit, unusual time pressures to start or complete the surgery, and unusual physical characteristics including morbid obesity or physical deformity.16

10 starting points for medical error preventionSo what are we to do? Consider:

- Using a preprocedure verification checklist.

- Marking the operative site.

- Completing a time out process prior to starting the procedure, according to the Joint Commission protocol. [For more information on Joint Commission-recommended time out protocols and ways to prevent medical errors, click here.]

- Involving the patient in the identification and procedure definition process. (This is an important part of informed consent.)

- Providing appropriate proctoring and sign-off for new procedures and technology.

- Avoiding sleep deprivation situations, especially with regard to emergency procedures.

- Using only radiopaque-labeled materials placed into the operating cavity.

- Considering medication effect on a fetus, if applicable.

- Reducing distractions from pagers, telephone calls, etc.

- Maintaining a “sterile cockpit” (or distraction free) environment for everyone in the OR.

Set the stage for best outcomesA true team approach is an excellent modus operandi before, during, and after surgery,setting the stage for best outcomes for patients.

“As human beings, surgeons will commit errors and for this reason they have to adopt and utilize stringent defense systems to minimize the incidence of these adverse events … Transparency is the first step on the way to a new safety culture with the acknowledgement of errors when they occur with adoption of systems destined to establish their cause and future prevention.”1

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Galleano R, Franceschi A, Ciciliot M, Falchero F, Cuschieri A. Errors in laparoscopic surgery: what surgeons should know. Mineva Chir. 2011;66(2):107−117.

- Fabri P, Zyas-Castro J. Human error, not communication and systems, underlies surgical complications. Surgery. 2008;144(4):557−565.

- Nanji KC, Patel A, Shaikh S, Seger DL, Bates DW. Evaluation of perioperative medication errors and adverse drug events. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(1):25−34.

- Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error−the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2139. Balogun J, Bramall A, Berstein M. How surgical trainees handle catastrophic errors: a qualitative study. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1179−1184.

- Grober E, Bohnen J. Defining medical error. Can J Surg. 2005;48(1):39−44.

- Anderson RE, ed. Medical Malpractice: A Physician's Sourcebook. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, Inc; 2004.

- Mehlman MJ. Professional power and the standard of care in medicine. 44 Arizona State Law J. 2012;44:1165−1777. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2205485. Revised February 13, 2013.

- Hyman DA, Silver C. On the table: an examination of medical malpractice, litigation, and methods of reform: healthcare quality, patient safety, and the culture of medicine: "Denial Ain't Just a River in Egypt." New Eng Law Rev. 2012;46:417−931.

- Landers R. Reducing surgical errors: implementing a three-hinge approach to success. AORN J. 2015;101(6):657−665.

- Pettigrew R, Burns H, Carter D. Evaluating surgical risk: the importance of technical factors in determining outcome. Br J Surg. 1987;74(9):791−794.

- Parker W. Understanding errors during laparoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2010;37(3):437−449.

- Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Analyzing cockpit communications: the links between language, performance, error, and workload. Hum Perf Extrem Environ. 2000;5(1):63−68.

- Kenyon T, Lenker M, Bax R, Swanstrom L. Cost and benefit of the trained laparoscopic team: a comparative study of a designated nursing team vs. a non-trained team. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(8):812−814.

- Woodman R. Surgeons should train like pilots. BMJ. 1999;319:1321.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 464: Patient safety in the surgical environment. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):786−790.

- Galleano R, Franceschi A, Ciciliot M, Falchero F, Cuschieri A. Errors in laparoscopic surgery: what surgeons should know. Mineva Chir. 2011;66(2):107−117.

- Fabri P, Zyas-Castro J. Human error, not communication and systems, underlies surgical complications. Surgery. 2008;144(4):557−565.

- Nanji KC, Patel A, Shaikh S, Seger DL, Bates DW. Evaluation of perioperative medication errors and adverse drug events. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(1):25−34.

- Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error−the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. doi:10.1136/bmj.i2139. Balogun J, Bramall A, Berstein M. How surgical trainees handle catastrophic errors: a qualitative study. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1179−1184.

- Grober E, Bohnen J. Defining medical error. Can J Surg. 2005;48(1):39−44.

- Anderson RE, ed. Medical Malpractice: A Physician's Sourcebook. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, Inc; 2004.

- Mehlman MJ. Professional power and the standard of care in medicine. 44 Arizona State Law J. 2012;44:1165−1777. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2205485. Revised February 13, 2013.

- Hyman DA, Silver C. On the table: an examination of medical malpractice, litigation, and methods of reform: healthcare quality, patient safety, and the culture of medicine: "Denial Ain't Just a River in Egypt." New Eng Law Rev. 2012;46:417−931.

- Landers R. Reducing surgical errors: implementing a three-hinge approach to success. AORN J. 2015;101(6):657−665.

- Pettigrew R, Burns H, Carter D. Evaluating surgical risk: the importance of technical factors in determining outcome. Br J Surg. 1987;74(9):791−794.

- Parker W. Understanding errors during laparoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2010;37(3):437−449.

- Sexton JB, Helmreich RL. Analyzing cockpit communications: the links between language, performance, error, and workload. Hum Perf Extrem Environ. 2000;5(1):63−68.

- Kenyon T, Lenker M, Bax R, Swanstrom L. Cost and benefit of the trained laparoscopic team: a comparative study of a designated nursing team vs. a non-trained team. Surg Endosc. 1997;11(8):812−814.

- Woodman R. Surgeons should train like pilots. BMJ. 1999;319:1321.

- American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 464: Patient safety in the surgical environment. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):786−790.

In this Article

- Medical error vs negligence

- Caring for the second victim

- 10 starting points for reducing medical errors

The medicolegal considerations of interacting with your patients online

CASE: Patient discloses personal information in electronic communication. How to respond and what’s at stake?

Your nurse comes to you with a dilemma. Last Friday she received an email from a patient, sent to the nurse’s personal email account (G-mail) that conveyed information regarding the patient’s recent treatment for a herpetic vulvar lesion. The text details presumed exposure, date and time, number of sexual partners, concernfor “spread of disease,” and the patient’s desire to have a comprehensive sexually transmitted infection screening as soon as possible.

Your nurse has years of professional experience, but she is perhaps not the most savvy with regard to current information technology and social media. Nonetheless, she knows it is best not to immediately respond to the patient’s email without checking with you. She tracks you down on Monday morning to review the email and the dilemma she feels she has been placed in. What’s the best next step?

While discussing the general question with the staff, another nurse notes that there have been some reviews of the office on social media. It seems that this second nurse tweets and texts with patients all the time. The office manager strongly suggests that the office “join the 21st Century” by setting up a Facebook page and using their webpage to attract new patients and communicate with current patients.

How do you prepare for this? Is your staff knowledgeable about the dos and don’ts of social media?

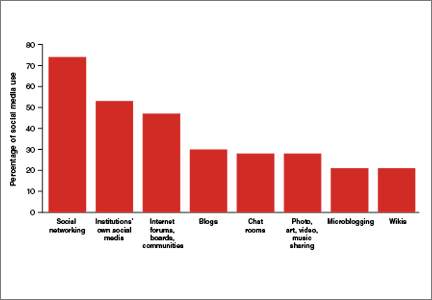

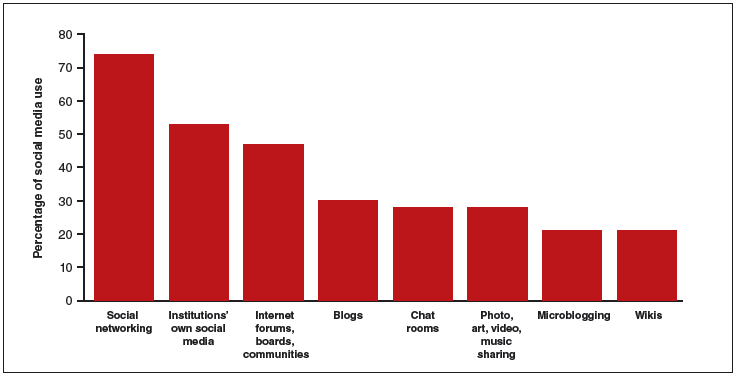

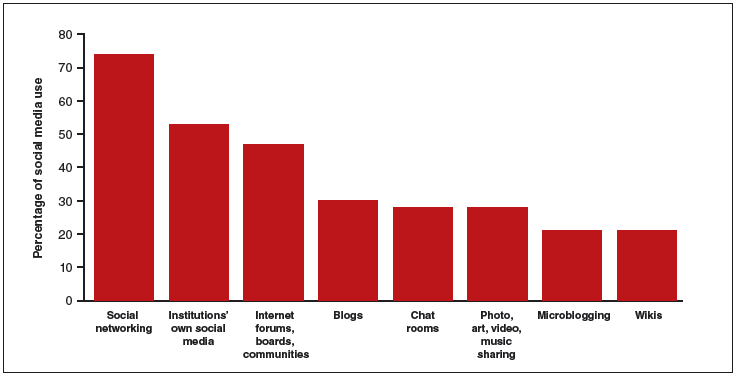

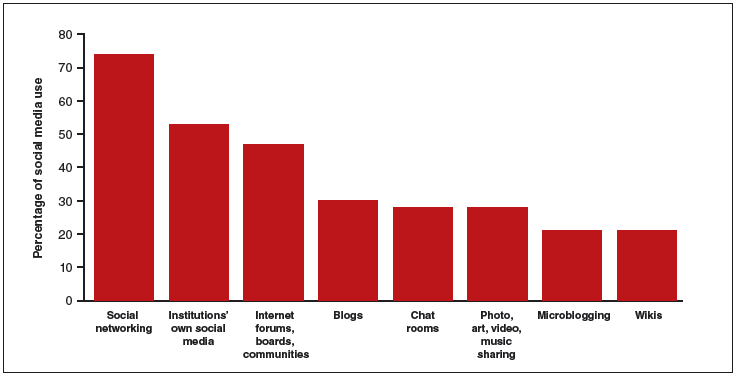

The use of social media by health care providers has been growing for several years. Back in 2011 a large survey by QuantiaMD revealed that 87% of physicians used social media for personal reasons, and 67% of them used it professionally.1 How they used it for professional purposes also was explored in 2011, with almost 3 of 4 physicians using it for social networking and more than half engaging with their own institution’s social media (FIGURE).2 In 2013, 53% of physicians indicated that their practice had a Facebook platform, 28% had a presence on LinkedIn, and 21% were on Twitter.3 Not surprisingly, social media use is higher among younger physicians4; the 2016 equivalents to these percentages most likely are higher.

| Health providers’ use of social media for professional reasons2 |

|

In 2011, a survey found that most health providers used social networking, their institutions’ own social media, and Internet forums, boards, and communities for professional reasons. |

Patients’ outreach through social media regarding health care information continues to grow, with 33.8% asking for health advice using social media.5 While email and other social media open the possibility of improved communication with patients, they also present a number of important professional and legal issues that deserve special consideration.6 Each medium presents its own challenges, but there are 4 categories of concern related to basic values and rights that we consider important to review:

- confidentiality

- dual relationships and conflicts of interest

- quality of care and advice

- general professionalism (including advertising).

Confidentiality

Few values of the medical profession are of longer standing than the commitment to maintain patient privacy. Fifth Century BC obligations continue to apply to the technology of the 21st Century AD. And the challenges are significant.

Email is not secure

In the opening case, the choice to email her clinician was apparently the patient’s. She probably does not realize that email is not very confidential, although it is undoubtedly in the Terms of Service Agreement she clicked through. Her email was likely scanned by her email service provider—Google, in this case—as well as the nurse. If, however, the physician’s office responds by email, it may well compound the confidentiality problem by further distributing the information through yet another email provider.

If, as a physician, you encourage email communication by your patients, a smart approach is to emphasize that such communications are not very confidential. At a minimum, until a secure email system can be established, it is best not to transmit medical information via email and to inform patients of the risk of such communication. In the case above, the nurse who received the email should respond to the patient by telephone (much more secure). Or she can respond to the patient by email (not including the patient’s message in the return), writing that, because email communications are inherently not confidential, she suggests a phone call or personal visit.

This case also notes that the patient sent the email to the nurse’s personal account, not to an office email account. Sending medical emails to an employee’s personal account raises additional problems of confidentiality and appropriate controls. It should be made clear that employees should not be discussing private medical matters via their own email accounts.

Other forms of social media are also not secure

Similar concerns arise about texting and using Twitter by the second nurse. These activities apparently had been unknown to the physician, but the practice still may be responsible for her actions. These are insecure forms of communication and raise serious ethical and legal concerns.

Other social media pose confidentiality risks as well. For example, a physician was dismissed from a position and reprimanded by the medical board for posting patient information on Facebook,7 and an ObGyn caused problems by posting a nasty note about a patient who showed up late for an appointment.8 Too many patients may not understand that posting on social media is the equivalent of standing on a street corner yelling private information. Social media sites that invite the discussion of personal matters are an invitation to trouble.

Physicians are ethically obliged to protect confidentiality

Professional standards place significant ethical obligations on physicians to protect patient confidentiality. The American Medical Association (AMA) has an ethics opinion on professionalism with social media,9 as does the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG).10 Another excellent discussion of ethical and practical issues is a joint position paper by the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards.11 Both documents focus attention on issues of confidentiality.

Physicians are legally obliged to protect confidentiality

There are many legal protections for confidentiality that can be implicated by electronic communications and social media. All states provide protection for unwarranted disclosure of private patient information. Such disclosures made electronically are included.12 Indeed, because electronic disclosures may be broadcast more widely, they may be especially dangerous. The misuse of social media may result in license discipline by the state board, regulatory sanctions, or civil liability (rare, but criminal sanctions are a possibility in extreme circumstances).

In addition to state laws regarding confidentiality, there are a number of federal laws that cover confidential medical information. None is more important than the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the more recent HITECH amendments (Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health).13 These laws have both privacy provisions and security (including “encryption”) requirements. These are complicated laws but at their core are the notions that health care providers and some others:

- are responsible for maintaining the security and privacy of health information

- may not transmit (even unintentionally) such information to others without patient permission or legal authority.14

- may not transmit (even unintentionally) such information to others without patient permission or legal authority.

A good source of step-by-step information about these laws is “Health information privacy: Covered entities and business associates,” on the US Health and Human Services website.14

HITECH also provides for notice to patients when health information is inappropriately transmitted. Thus, a missing USB flash drive with patient information may require notification to thousands of patients.15 Any consideration of the use of email or social media in medical practice must take into account the HIPAA/HITECH obligations to protect the security of patient health information. There can be serious professional consequences for failing to follow the HIPAA requirements.16

Dual relationships and conflicts of interest

In our hypothetical case, the office manager’s suggestion that the office use Facebook and their website to attract new patients also may raise confidentiality problems. The Facebook suggestion especially needs to be considered carefully. Facebook use is estimated to be 63% to 96% among students and 13% to 47% among health care professionals.17 Facebook is most often seen as an interactive social site; it risks blurring the lines between personal and professional relationships.9 There is a consensus that a physician should not “friend” patients on Facebook. The AMA ethics opinion notes that “physicians must maintain appropriate boundaries of the patient-physician relationship in accordance with professional ethical guidelines, just as they would in any other context.”9

Separate personal and professional contacts

Difficulties with interactive social media are not limited to the physicians in a practice. The problems increase with the number of staff members who post or respond on social media. Control of social media is essential. The practice must ensure that staff members do not slip into inappropriate personal comments and relationships. Staff should understand (and be reminded of) the necessity of separating personal and professional contacts.

Avoid misunderstandings

In addition, whatever the intent of the physician and staff may be, it is essentially impossible to know how patients will interpret interactions on these social media. The very informal, off-the-cuff, chatty way in which Facebook and similar sites are used invites misunderstandings, and maintaining professional boundaries is necessary.

Ground rules

All of this is not to say that professionals should never use Facebook or similar sites. Rather, if used, ground rules need to be established.

Social media communications must:

- be professional and not related to personal matters

- not be used to give medical advice

- be controlled by high level staff

- be reviewed periodically.

Staff training

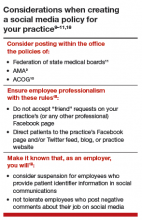

Particularly for interactive social media (email, texts, Twitter, Facebook, etc), it is essential that there be both clear policies and good staff training (TABLE).9–11,18 There really should be no “making it up as we go along.” Staff on a social media lark of their own can be disastrous for the practice. Policies need to be updated frequently, and staff training reinforced and repeated periodically.

Quality of care and advice

Start with your website

Institutions’ websites are major sources of health care information: Nearly 32% of US adults would be very likely to prefer a hospital based on its website.5 Your website can be an important face of your practice to the community—for good or for bad. On one hand, the practice can control what is on a website and, unlike some social media, it will not be directed to individual patients. Done well, it “provides golden opportunities for marketing physician services, as well as for contributing to public health by providing high-quality online content that is both accurate and understandable to laypeople.”19 Done badly, it can convey incorrect and harmful information and discredit the medical practice that established it.

Your website introduces the practice and settings, but it will serve another purpose to thousands of people who likely will see it over time as a source of credible health information. The importance of ensuring that your website is carefully constructed to provide, or link to, good medical advice that contributes to quality of care cannot be overstated.

A good website begins with a clear statement of the reasons and goals for having the site. Professional design assistance generally is used to create the site, but that design process needs to be overseen by a medical professional to ensure that it conveys the sense of the practice and provides completely accurate information. A homepage of dancing clowns with stethoscopes may seem good to a 20-something-year-old designer, but it is not appropriate for a physician. It will be the practice, not the designer, who is held accountable for the site content. Links to other sites need to be vetted and used with care. Patients and other members of the public may well take the links as carrying the endorsement of the practice and its physicians.

Perhaps the greatest risk of a website is that it will not be kept current. Unfortunately, they do not update themselves. Some knowledgeable staff member must frequently review it to update everything from office hours and personnel to links to other sites. In addition, the physicians periodically must review it to ensure that all medical information is up to date and accurate. Old, outdated information about the office can put off potential patients. Outdated medical information may be harmful to patients who rely on it.

Any professional website should include disclaimers informing users that the site is not intended to establish a professional relationship or to give professional advice. The nature and extent of the disclaimer will depend on the type of information on the site. An example of a particularly thorough disclaimer is the Mayo Clinic disclaimer and terms of use (http://www.mayoclinic.org/about-this-site/terms-conditions-use-policy).