User login

Baby Boomer HCV Screening and Care

INTRODUCTION

The baby boomer generation, born from 1945 to 1965, accounts for 75% of the estimated 2.7 to 3.9 million persons with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the US.[1, 2, 3] Most HCV‐infected baby boomers do not know that they are infected.[4] With the advent of better‐tolerated, more‐effective therapies to treat chronic HCV infection,[5] and to reduce rates of complications such as cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma,[6] universal 1‐time screening of baby boomers has been endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the United States Preventive Services Task Force.[1, 7] Hospitalized baby boomers may offer an important target for HCV screening. Our group conducted an anonymous HCV seroprevalence study of nearly 800 patients on general medicine and trauma services of 2 Philadelphia hospitals, and found that 8% had undiagnosed HCV infection, and 8% had diagnosed HCV. [8]

Little is known about barriers and facilitators to implementation of universal HCV screening of baby boomers. Lessons from implementing HIV screening offer a useful guide.[9] First, limited clinician knowledge and confusion about screening guidelines necessitated convenient, well‐designed educational programs.[10] Second, burdensome consent procedures were reduced by opt‐out consent for screening supplemented by patient education.[9] Third, electronic medical record (EMR) algorithms minimized burdens on staff by efficiently identifying and flagging eligible persons for screening.[11] Fourth, ancillary staff support for patient education and linkage to follow‐up care increased screening rates compared with usual care by physicians/staff.[11] Finally, routine human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing of inpatients increased rates of diagnosis, especially compared with physician referral systems.[12]

This article describes how HIV screening strategies informed the development in a baby boomer HCV screening and linkage to a care program in a safety‐net hospital serving a majority Hispanic population. We report results of the first 14 months of the screening program and linkage to care for chronically HCV‐infected persons after a minimum 10 months follow‐up. We also estimate costs for program implementation and maintenance to inform hospital administrators, healthcare policymakers, and clinicians about resources that may be required to effectively screen hospitalized baby boomers for HCV.

METHODS

Study Setting

The HCV baby boomer screening program was pilot tested in November 2012 and launched December 1, 2012 in a 498‐bed academic‐affiliated hospital of a healthcare system serving the indigent population of South Texas.

Project Development Phase

From October 1, 2012 to November 30, 2012, project infrastructure development and provider/staff education were conducted. A half‐hour PowerPoint lecture (in person or online) was developed about HCV epidemiology, birth‐cohort HCV screening guidelines, newer treatment modalities, and screening program components. Lectures were delivered to departmental chairs at the affiliated medical school, departmental grand rounds, and the hospital's nursing supervisors. One‐on‐one informational meetings were also held with hospital administrators and staff.

With the hospital's information technology team, screens were developed to identify eligible baby boomers from up to 7 years of previous inpatient and outpatient encounters in the EMR from: birth year (19451965) and no prior diagnosis of HCV infection (070.41, 070.44, 070.51, 070.54, 070.7x, V02.62) or any type of completed test for HCV. The algorithm also excluded patients admitted to psychiatry due to lack of decision‐making capacity or patients with a poor prognosis such as metastatic cancer. An audit of 100 consecutive excluded patients identified all as legitimate.

A new laboratory order for HCV screening was developed by laboratory administrators and pathology faculty for an anti‐HCV antibody test followed by reflex HCV RNA testing for positive results per CDC recommendations.[13] The anti‐HCV test was performed on serum or ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid plasma using the Advia Centaur HCV Assay (Bayer HealthCare LLC, Tarrytown, NY). This assay has excellent sensitivity (99.9%) and specificity (97.5%).[14, 15] The HCV RNA assay was performed using quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HCV test (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA). Use of plasma preparation tubes (PPTs) (BD Vacutainer PPT tubes; Becton, Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ) permitted both anti‐HCV antibody and HCV PCR testing to be performed on the same specimen when anti‐HCV antibody was detected, eliminating a second blood draw for the PCR test. For patients eligible for screening, an EMR algorithm was created to add an HCV screening order to over 50 different admission order sets.

To educate patients newly diagnosed with HCV infection, we developed an interactive, low‐literacy, educational program in Spanish and English for an electronic tablet device that addressed: HCV epidemiology, transmission prevention, factors that can accelerate chronic HCV infection, and management/treatment strategies. At several points in the program, the patient needed to answer questions correctly to continue. The tablet retained responses linked to a study identification about alcohol consumption, history of past and current illicit drug use, sexual risk behavior, and offered risk reduction messages. The tablet content and presentation reflected suggestions by Hispanic patient‐reviewers about cultural appropriateness and comprehension.

Project Implementation and Maintenance Phase

We report implementation of the program from December 1, 2012 to January 31, 2014. An automated EMR report classified all baby boomers admitted in the previous 24 hours as: (1) eligible with pending screening test order, (2) eligible without an order, (3) ineligible due to prior HCV test or diagnosis, or (4) ineligible due to comorbidity (eg, metastatic cancer). For approximately one‐third of eligible patients, a study team member placed an order after review of the daily admission report because the order had not been automatically placed.

Admitting nurses initially asked for consent from eligible patients for HCV screening, but this was ultimately deemed too onerous a task along with all of their other duties. We then instituted opt‐out consent with patient education about testing and opportunities to refuse via posters placed throughout the hospital and flyers in admission packets. A bilingual HCV counselor provided HCV screening test results to all patients. She counseled patients who screened positive for HCV with the educational program on an electronic tablet and developed a follow‐up care plan.

A bilingual promotora (community health worker) contacted patients newly diagnosed with chronic HCV infection after hospital discharge to address the following: obtaining insurance, access to primary care and HCV specialty care, scheduling appointments, and treatment for alcohol problems or drug abuse. After obtaining signed consent, the promotora sent test results and recommendations for follow‐up care (eg, hepatitis A and B immunization) to a designated outpatient physician and reminded patients about appointments and pending tests. The promotora received training in motivational interviewing skills to engage patients with needed care including alcohol treatment.

Study Data

A summary report was developed from the EMR with demographic, insurance, clinical, and HCV screening data for all admitted baby boomers. For patients diagnosed with chronic HCV infection, the promotora obtained data about follow‐up HCV care through December 10, 2014 from the EMR, outside provider records, and patient reports.

Study Variables

The 2 outcome measures were a positive anti‐HCV antibody test and positive HCV RNA test. Insurance status was categorized as insured (private, public, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense) or uninsured (self‐pay or county‐based financial assistance program). Problem drinking was identified from International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes for the admission, notes by clinicians describing alcohol abuse/dependence, or quantity/frequency meeting National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism criteria for alcohol problems of >14 drinks/week or >4 drinks/day for men and >7 drinks per week or >3 drinks per day for women.[16]

Implementation costs included informatics support, mobile app development, other patient educational materials, costs of screening tests for uninsured, and 0.3 full‐time equivalent (FTE) of a clinician for half a year. Maintenance costs included salaries for the study team, HCV testing costs, and postage.

Analysis

Demographics by HCV antibody test results are compared using [2] tests or Student t tests as appropriate. Among persons with a positive HCV antibody test, HCV RNA results are similarly compared. This implementation project was approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Institutional Review Board (HSC20130033N).

RESULTS

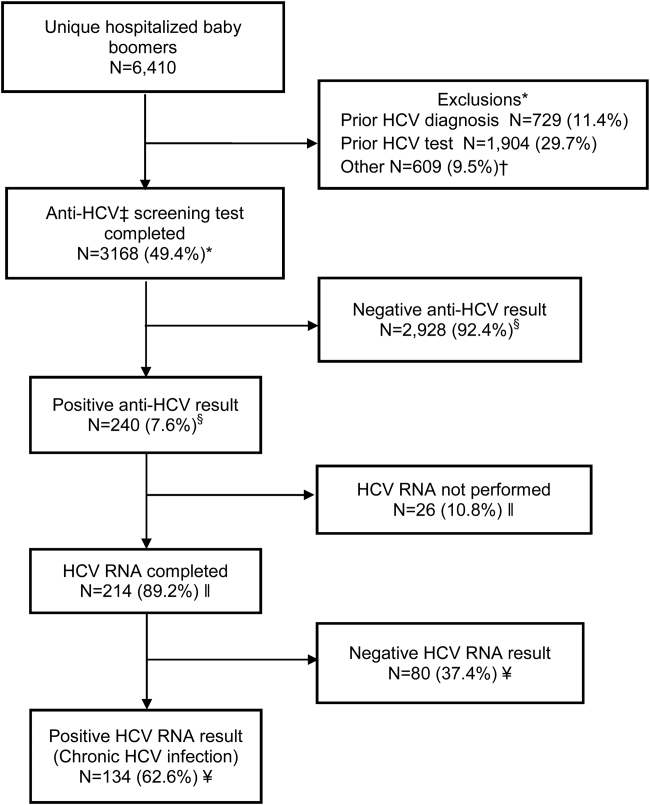

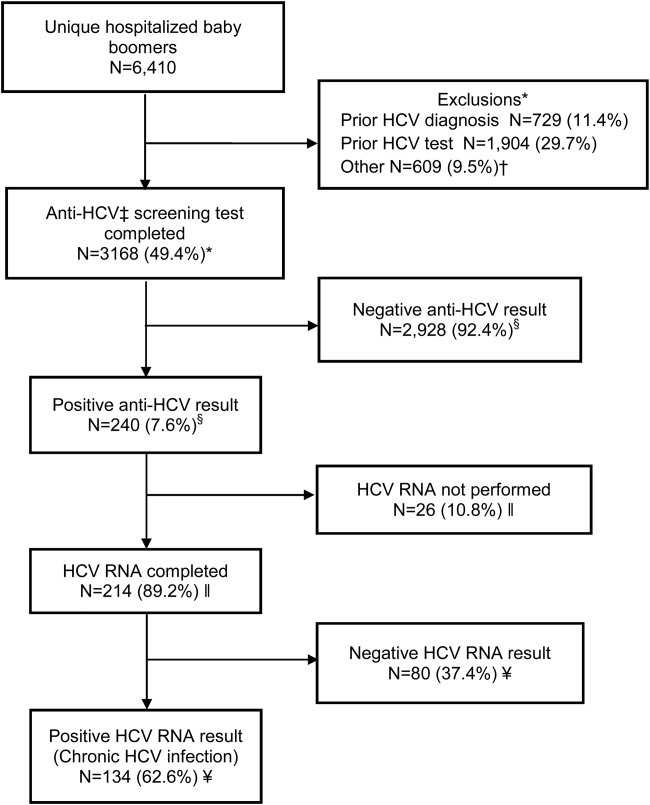

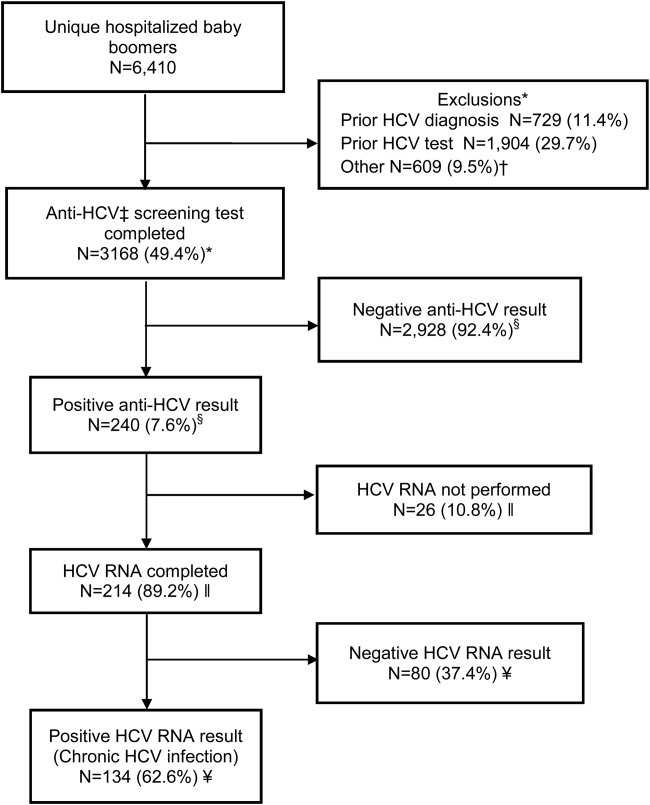

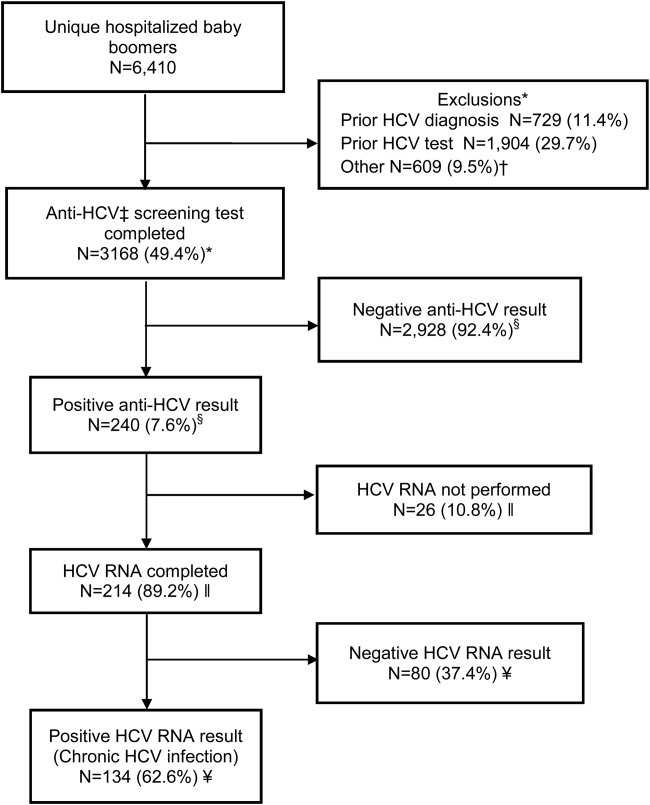

Within 14 months, 6410 unique baby boomers were admitted with a mean age 56.4 years (standard deviation [SD] 5.7), 55.9% men, 59.1% Hispanic, 8.2% nonwhite, and 46.7% uninsured (Table 1). Among admitted patients, 729 (11.4%) had a previous HCV diagnosis and 1904 (29.7%) had been tested for HCV (Figure 1). Anti‐HCV antibody testing was completed for 3168 (49.4% of all admitted patients and 83.9% of never‐tested patients). After exclusions such as significant comorbidity or psychiatric admission, 95% of eligible persons were tested. Of screened patients, 240 (7.6%) were positive; these patients were significantly younger (P<0.0001) and more likely to be men (P<0.0001) and uninsured (P=0.002) (Table 1). Notably, 10% of men were anti‐HCV positive versus 4% of women. In this predominantly Hispanic cohort, no significant difference appeared by race‐ethnicity, but African Americans had a higher prevalence (10.4%) than other groups.

| Characteristic | All Screened Patients, No. | Anti‐HCV Antibody‐Positive Patients, No. (Row %) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overall | 3,168 | Total=240 (7.6) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 57.0 (5.7) | 54.8 (5.0) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 1,771 | 185 (10.4) | <0.0001 |

| Women | 1,397 | 55 (3.9) | |

| Race | |||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 1,036 | 86 (8.3) | 0.12 |

| Hispanic | 1,872 | 134 (7.2) | |

| African American | 163 | 17 (10.4) | |

| Other | 97 | 3 (3.1) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Insured | 1,740 | 109 (6.3) | 0.002 |

| Uninsured | 1,428 | 131 (9.2) | |

HCV RNA testing was completed for 214 (89.2%) anti‐HCVpositive patients, of whom 134 (62.6%) had detectable RNA, indicating chronic HCV infection (Figure 1). Overall, 4.2% of all eligible patients tested for HCV were chronically infected. No characteristics were significantly associated with chronic HCV, but persons with chronic infection tended to be younger, uninsured, and African American (Table 2).

| Characteristics | All HCV RNA‐Tested Patients, No. | HCV RNA‐Positive Patients, No. (Row %) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overall | 214 | 134 (62.6) | |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 54.6 (5.0) | 54.2 (5.1) | 0.09 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 165 | 106 (64.2) | 0.37 |

| Women | 49 | 28 (57.1) | |

| Race | |||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 78 | 49 (62.8) | 0.65 |

| Hispanic | 118 | 73 (61.8) | |

| African American | 15 | 11 (73.3) | |

| Other | 3 | 1 (33.3) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Insured | 92 | 52 (56.5) | 0.11 |

| Uninsured | 122 | 82 (67.2) | |

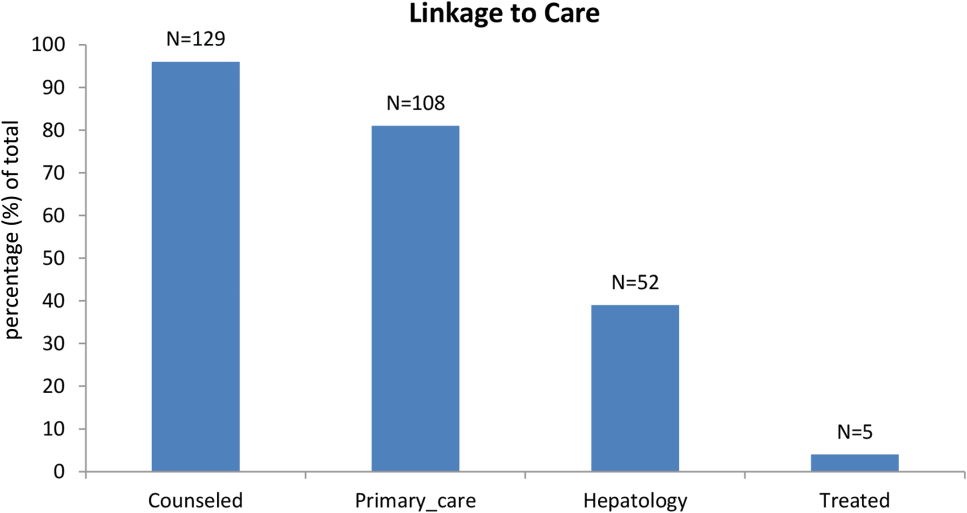

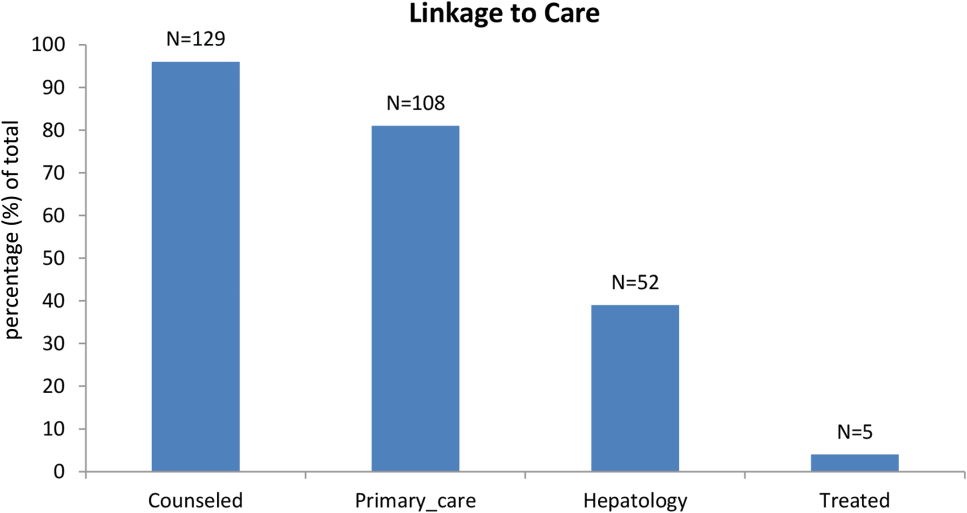

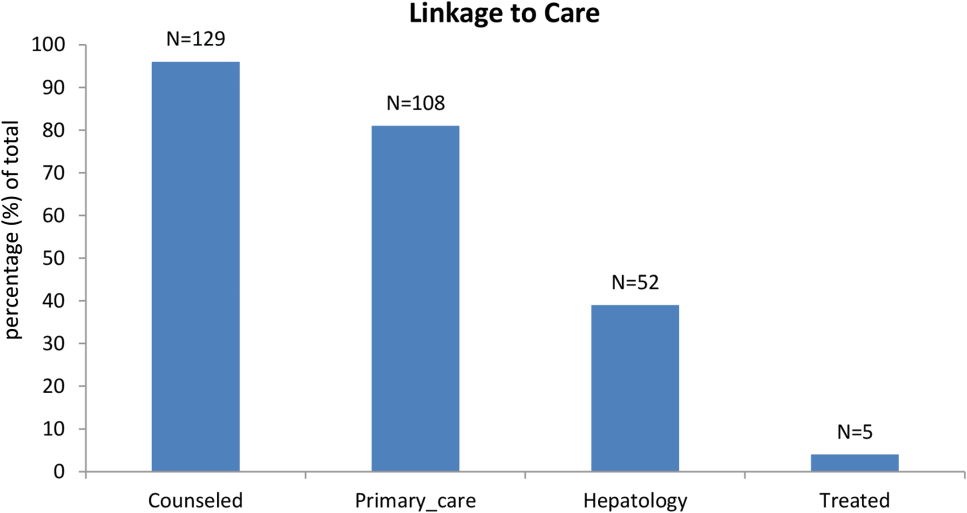

Among patients with chronic HCV infection, 129 (96.3%) were counseled and follow‐up plans developed (Figure 2). By December 10, 2014, 108 (80.6%) patients had received follow‐up primary care, and 52 (38.8%) had care from a hepatologist. Five had initiated HCV‐specific treatment, but many others were awaiting approval for compassionate drug programs offering direct‐acting antivirals. Barriers to care included 82 (61.2%) uninsured, 45 (34%) problem drinkers, 22 (16%) homeless, and 25 (18.6%) incarcerated (not shown). The promotora addressed these issues by visiting homes or homeless shelters, assistance with obtaining county‐based or other types of insurance, offering alcohol risk‐reduction counseling, linking patients to alcohol‐treatment programs, and communicating with the county jail about follow‐up care.

Most of the developmental costs for the program were dedicated to developing EMR programs (Table 3). An optional cost was for the development of the tablet educational program about HCV. In regard to maintenance costs for the first 14 months, the majority was to support the program faculty, counseling/case management, and a nurse practitioner who helped with ordering tests. We also estimated costs for testing uninsured patients (45% of HCV antibody tested, 57% of HCV PCR tested, per Tables 1 and 2, respectively), as they must be borne by the hospital.

| Program Component | Monthly ($) | Total ($) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Development phase (2 months prior to start) | ||

| Personnel | ||

| Faculty physicians (0.3 FTE salary+benefits) | 6,641 | 13,282 |

| Role: Development educational materials, provider education, and pilot testing | ||

| Technology | ||

| Development of eligibility screen and order sets for electronic medical record | 41,171 | |

| HCV counseling educational program for tabletdevelopment and pilot testing (optional) | 15,000 | |

| Patient educational materials (posters, flyers) | 400 | |

| Total for development phase | 69,853 | |

| Maintenance phase (14 months) | ||

| Personnel | ||

| Faculty physicians (0.3 FTE, salary+benefits) | 6,641 | 92,974 |

| Role: Coordinate with hospital staff and faculty, liaison with laboratory, supervise study team, review all identified cases for eligibility and management plans | ||

| Inpatient counselor and outpatient case management (2 FTE, salary+benefits) | 6,343 | 88,802 |

| Role: Inpatient and outpatient counseling of HCV Ab+patients and facilitation of follow‐up care for patients with chronic HCV infection | ||

| Nurse practitioner ($35/hour @ 10 hours/month) | 350 | 4,900 |

| Role: Review daily list of admitted baby boomers and manually order HCV screening test for those missed by the automated order | ||

| Postage | 10 | 140 |

| Laboratory costs for uninsured (based on % in cohort) | ||

| HCV antibody in plasma preparation tubes ($13.41/test 1,423) | 19,082 | |

| HCV RNA PCR ($87.96/test 122) | 10,731 | |

| Total for maintenance phase | 216,629 | |

| Total program costs | 286,482 | |

DISCUSSION

Implementation of universal HCV screening and linkage to care for hospitalized baby boomers utilizes a multicomponent infrastructure that reflects lessons learned from similar HIV programs. Use of an EMR algorithm to identify eligible patients and programs to automatically order HCV screening was a linchpin of our high testing rate and averted testing those who did not require screening. Of all 6410 baby boomers admitted to our safety‐net hospital, the EMR screen identified over 40% as ineligible due to prior diagnosis of HCV infection or prior HCV tests. Most of the additional 609 patients who were not tested were excluded due to comorbidities or admission to psychiatry. Overall, the EMR programs, tests ordered by the team, and opt‐out screening with education resulted in screening 95% of eligible patients. However, this program carries substantial costs, nearly $300,000 for the first 2 years, for unreimbursed services in this safety‐net hospital. The new guidelines for HCV screening[1, 2] are not accompanied by financial support either for program implementation or for screening and linkage to care for the uninsured, creating significant financial hurdles to achieve guideline compliance within already overtaxed public healthcare systems.

The infrastructure implemented in this hospital succeeded in achieving a higher rate of HCV screening of baby boomers than reported by other programs. In an emergency department in Birmingham, Alabama, a screening program for baby boomers tested 66% of 2325 persons who were HCV‐unaware.[17] In an outpatient clinic for men who have sex with men, only 54% of 1329 patients were screened for HCV.[18]

Among 3168 screened patients in our cohort, 7.6% were anti‐HCV antibody positive, which is over twice the prevalence of 3.5% (95% confidence interval: 2.2%‐4.8%) for anti‐HCVpositive tests in baby boomers based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2001 to 2010.[19] However, the Alabama emergency department study found that 11% of tested patients were anti‐HCV positive.[17] Although that study lacked race‐ethnicity data for half of the subjects, among those with this information, 13% of black and 7% of white subjects tested anti‐HCV positive. Compared with the Alabama study, the anti‐HCV prevalence in our cohort was somewhat lower for blacks (10.4%) but higher for non‐Hispanic whites (8.3%). Hispanics in our cohort had the lowest anti‐HCV prevalence (7.2%), whereas the Alabama study did not report this figure. National studies also find that the prevalence of anti‐HCVpositive results is twice as high for blacks compared with non‐Hispanic whites and Hispanics, and nearly twice as high for men compared with women.[19] In our cohort, the proportion of men with anti‐HCVpositive results was nearly 3 times that for women.

Diagnosis of chronic HCV infection requires 2 tests, similar to performing a Western blot test after a positive enzyme‐linked immunoassay for HIV. In a Veterans Affairs study, only 64% of patients with a positive anti‐HCV antibody test had a HCV RNA performed when reflex testing was not performed, and patients had to come in for a second test versus >90% of patients in sites that offer reflex testing.[20] At a somewhat increased price due to using more expensive PPTs ($96/100 PPT tubes vs $6.50/100 for serum red top tubes), both tests were performed on the same blood sample, resulting in 89% of anti‐HCV antibody‐positive patients being tested for HCV RNA.

Overall, 62% of patients in our cohort with a positive anti‐HCV antibody test had HCV RNA detected (viremic) compared with 71% of persons aged 20 years in an NHANES study from 2003 to 2010.[21] Several factors may contribute to this lower rate of chronic infection. In a study of HCV seropositive blood donors, Hispanics and non‐Hispanic whites were significantly more likely to have spontaneously cleared HCV infection than Asians and non‐Hispanic blacks.[22] Spontaneous clearance of HCV has also been associated with younger age at infection and HCV genotype 1.[23] Poorly understood genetic factors may also play a role.[24] The high rate of HCV clearance in our cohort reinforces the need to perform HCV RNA testing.

Overall, 4.2% of our cohort had chronic HCV infection. According to CDC estimates from 1999 to 2008 NHANES data, 2.74 million (3.25%) of 84.2 million US baby boomers have been infected with HCV, and 2.04 million (2.4%) have chronic infection.[1] Therefore, our safety‐net cohort of never‐tested baby boomers had over twice the prevalence of chronic HCV infection than the national estimate for this age group. This high proportion of chronic HCV may reflect our predominantly low‐income patient population. An analysis conducted by Milliman, Inc. using 2010 data estimated that half of all persons with undiagnosed HCV infection are uninsured.[25] This finding reinforces the need to conduct HCV screening in acute‐care settings such as hospitals, because the uninsured have poor access to ambulatory care.

Our chronic HCV‐infected cohort had many barriers to follow‐up care because most were uninsured and 15% were homeless. Our counselors addressed socioeconomic barriers to care[26] and concerns about the disease.[27] Many patients also had problem drinking based on either self‐report or documented in the medical record. Even moderate alcohol use may increase the risk of overall and liver‐related mortality from chronic HCV infection,[28] so our team offered brief alcohol counseling and partnered with healthcare providers and local Alcoholics Anonymous programs to offer support.

We linked 80% of newly diagnosed patients to primary care or hepatology providers, aided by a county‐level financial assistance program for healthcare services for uninsured residents, but it still required patients to pay out of pocket for care. Access to newer, highly effective, all‐oral therapy treatment[5] was slowed while awaiting US Food and Drug Administration approval in the first year of this project, then treatment provided only after lengthy applications to drug company assistance programs with priority given to persons with compensated cirrhosis.

Our project raises serious concerns for policymakers and payers. Should universal baby boomer HCV testing be undertaken without taking into account the financial and personnel resources required to implement this screening program or the substantial expenditures necessary to treat chronically infected persons? Although the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services pay for HCV screening costs,[29] our hospital had to cover costs for uninsured persons. Admittedly, Texas has the highest proportion of residents who are uninsured in the nation, but even in other states, Medicaid and other insurance programs are wrestling with how to deal with the high cost of HCV therapy.[30]

We acknowledge several limitations of this project. First, it was undertaken in only 1 hospital. Yet, our challenges and solutions are likely to be applicable to other hospitals nationally, especially those serving vulnerable populations. Second, patients in our cohort were usually admitted for comorbidities that needed to be managed before HCV infection could be addressed. However, persons with a poor prognosis, such as metastatic cancer, were excluded. We did not attempt to exclude other persons with serious comorbidities such as congestive heart failure, because the guidelines do not currently recommend this, and there may be benefits for patients, their families, and providers from knowing that an individual is chronically HCV infected even if they are not eligible to be treated. Third, the cost of the program was supported in part by a grant and would otherwise have to be borne by the hospital. Fourth, the EMR used by our hospital allows hundreds of admission order sets to be created and made automated order entry hard to implement. This is unlikely to be the situation in other hospitals using different types of EMRs.

It remains to be seen whether safety‐net hospitals with populations at greater risk of HCV infection can afford to support HCV testing and linkage to care. In view of several cost‐effectiveness studies that find screening and treating chronic HCV‐infected baby boomers cost‐effective within standard thresholds,[31, 32, 33] it may be important for policymakers and payers to consider lessons from HIV programs. Because HIV‐infected persons could not afford life‐saving medication, vigorous advocacy efforts led to legislation approving the Ryan White program in 1990 to fill gaps in HIV care that were not covered by other sources of support.[34] HCV infection is the most common blood‐borne infection in the nation, with potentially devastating consequences if ignored, but the underlying premise that universal HCV testing will save lives is in question if most of the individuals who are diagnosed with chronic HCV are low income, uninsured, or underinsured with limited access to curative medications. A rigorous public policy debate regarding both the merits of screening and the availability of treatment to those who are diagnosed is essential to the success of these programs.

Disclosure

Funding for this study was received from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC PS12‐1209PPHF12. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , , , Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61:1–32.

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: evaluation of hepatitis C virus infection testing and reporting–eight U.S. sites, 2005‐2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:357–361.

- , , , , Hepatitis C virus infection in USA: an estimate of true prevalence. Liver Int. 2011;31:1090–1101.

- Institute of Medicine. Hepatitis and liver cancer: a national strategy for prevention and control of hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2010.

- , Current and future therapies for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1907–1917.

- , , , et al. Increasing prevalence of HCC and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1182–1188.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:349–357.

- , , Undiagnosed hepatitis C on the general medicine and trauma services of two urban hospitals. J Infect. 2009;59:62–69.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:51–60.

- , , , et al. Factors affecting clinician educator encouragement of routine HIV testing among trainees. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:839–844.

- , , , et al. Counselor‐versus provider‐based HIV screening in the emergency department: Results from the universal screening for HIV infection in the emergency room (USHER) randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:S126–S132.e1–4.

- , , Approaching the CDC's guidelines on the HIV testing of inpatients: physician‐referral versus nonreferral‐based testing. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:311–317.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Testing for HCV infection: an update of guidance for clinicians and laboratorians. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:362–365.

- Advia Centaur Assay Manual. Malvern, PA: Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics; Pub# 07063235, Rev. C, 2005‐01.

- , , , Comparison of the ADVIA Centaur and Abbott AxSYM immunoassay systems for a routine diagnostic virology laboratory. J Clin Virol. 2004;30:S11–S15.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. Available at: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol‐health/overview‐alcohol‐consumption/moderate‐binge‐drinking. Accessed June 12, 2014.

- , , , et al. Unrecognized chronic hepatitis C virus infection among baby boomers in the emergency department. Hepatology. 2015;61:776–782.

- , , , et al. Low rates of hepatitis screening and vaccination of HIV‐infected MSM in HIV clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:349–353.

- , , , , , The changing epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001 through 2010. J Hepatol. 2014;60:691–698.

- , , , , Viral RNA testing in hepatitis C antibody‐positive veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:235–238.

- , , , et al. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:293–300.

- , , , et al. NHLBI Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study (REDS) Group. Correlates of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA negativity among HCV‐seropositive blood donors. Transfusion. 2006;46:469–475.

- , , , , , Spontaneous loss of hepatitis C virus RNA from serum is associated with genotype 1 and younger age at exposure. J Med Virol. 2011;83:1338–1344.

- , , , et al. Genetics of spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus infection: a complex topic with much to learn. Hepatology. 2014;60:2127–2128.

- , , , Health care reform and hepatitis C: a convergence of risk and opportunity. Available at: http://us.milliman.com/uploadedFiles/insight/2013/convergence‐of‐risk‐and‐opportunity.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2015.

- , , , Hepatitis C testing, infection, and linkage to care among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, 2009‐2010. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:112–119.

- , Barriers to hepatitis C treatment. Liver Int. 2012;32:151–156.

- , , , , Moderate, excessive or heavy alcohol consumption: Each is significantly associated with increased mortality in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:703–709.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Proposed decision memo for screening for hepatitis c virus (HCV) in adults (CAG‐00436N). Available at: http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-proposed-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=272. Accessed June 2, 2014.

- , Therapy for hepatitis C—the costs of success. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1552–1553.

- , , , et al. Economic model of a birth cohort screening program for hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2012;55:1344–1355.

- , , , Cost‐effectiveness analysis of risk‐factor guided and birth‐cohort screening for chronic hepatitis C infection in the United States. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58975.

- , , , et al. The cost‐effectiveness of birth‐cohort screening for hepatitis C antibody in U.S. primary care settings. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:263–270.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health Resources and Services Administration: HIV/AIDS programs. Available at: http://hab.hrsa.gov/abouthab/legislation.html. Accessed April 8, 2015.

INTRODUCTION

The baby boomer generation, born from 1945 to 1965, accounts for 75% of the estimated 2.7 to 3.9 million persons with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the US.[1, 2, 3] Most HCV‐infected baby boomers do not know that they are infected.[4] With the advent of better‐tolerated, more‐effective therapies to treat chronic HCV infection,[5] and to reduce rates of complications such as cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma,[6] universal 1‐time screening of baby boomers has been endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the United States Preventive Services Task Force.[1, 7] Hospitalized baby boomers may offer an important target for HCV screening. Our group conducted an anonymous HCV seroprevalence study of nearly 800 patients on general medicine and trauma services of 2 Philadelphia hospitals, and found that 8% had undiagnosed HCV infection, and 8% had diagnosed HCV. [8]

Little is known about barriers and facilitators to implementation of universal HCV screening of baby boomers. Lessons from implementing HIV screening offer a useful guide.[9] First, limited clinician knowledge and confusion about screening guidelines necessitated convenient, well‐designed educational programs.[10] Second, burdensome consent procedures were reduced by opt‐out consent for screening supplemented by patient education.[9] Third, electronic medical record (EMR) algorithms minimized burdens on staff by efficiently identifying and flagging eligible persons for screening.[11] Fourth, ancillary staff support for patient education and linkage to follow‐up care increased screening rates compared with usual care by physicians/staff.[11] Finally, routine human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing of inpatients increased rates of diagnosis, especially compared with physician referral systems.[12]

This article describes how HIV screening strategies informed the development in a baby boomer HCV screening and linkage to a care program in a safety‐net hospital serving a majority Hispanic population. We report results of the first 14 months of the screening program and linkage to care for chronically HCV‐infected persons after a minimum 10 months follow‐up. We also estimate costs for program implementation and maintenance to inform hospital administrators, healthcare policymakers, and clinicians about resources that may be required to effectively screen hospitalized baby boomers for HCV.

METHODS

Study Setting

The HCV baby boomer screening program was pilot tested in November 2012 and launched December 1, 2012 in a 498‐bed academic‐affiliated hospital of a healthcare system serving the indigent population of South Texas.

Project Development Phase

From October 1, 2012 to November 30, 2012, project infrastructure development and provider/staff education were conducted. A half‐hour PowerPoint lecture (in person or online) was developed about HCV epidemiology, birth‐cohort HCV screening guidelines, newer treatment modalities, and screening program components. Lectures were delivered to departmental chairs at the affiliated medical school, departmental grand rounds, and the hospital's nursing supervisors. One‐on‐one informational meetings were also held with hospital administrators and staff.

With the hospital's information technology team, screens were developed to identify eligible baby boomers from up to 7 years of previous inpatient and outpatient encounters in the EMR from: birth year (19451965) and no prior diagnosis of HCV infection (070.41, 070.44, 070.51, 070.54, 070.7x, V02.62) or any type of completed test for HCV. The algorithm also excluded patients admitted to psychiatry due to lack of decision‐making capacity or patients with a poor prognosis such as metastatic cancer. An audit of 100 consecutive excluded patients identified all as legitimate.

A new laboratory order for HCV screening was developed by laboratory administrators and pathology faculty for an anti‐HCV antibody test followed by reflex HCV RNA testing for positive results per CDC recommendations.[13] The anti‐HCV test was performed on serum or ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid plasma using the Advia Centaur HCV Assay (Bayer HealthCare LLC, Tarrytown, NY). This assay has excellent sensitivity (99.9%) and specificity (97.5%).[14, 15] The HCV RNA assay was performed using quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HCV test (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA). Use of plasma preparation tubes (PPTs) (BD Vacutainer PPT tubes; Becton, Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ) permitted both anti‐HCV antibody and HCV PCR testing to be performed on the same specimen when anti‐HCV antibody was detected, eliminating a second blood draw for the PCR test. For patients eligible for screening, an EMR algorithm was created to add an HCV screening order to over 50 different admission order sets.

To educate patients newly diagnosed with HCV infection, we developed an interactive, low‐literacy, educational program in Spanish and English for an electronic tablet device that addressed: HCV epidemiology, transmission prevention, factors that can accelerate chronic HCV infection, and management/treatment strategies. At several points in the program, the patient needed to answer questions correctly to continue. The tablet retained responses linked to a study identification about alcohol consumption, history of past and current illicit drug use, sexual risk behavior, and offered risk reduction messages. The tablet content and presentation reflected suggestions by Hispanic patient‐reviewers about cultural appropriateness and comprehension.

Project Implementation and Maintenance Phase

We report implementation of the program from December 1, 2012 to January 31, 2014. An automated EMR report classified all baby boomers admitted in the previous 24 hours as: (1) eligible with pending screening test order, (2) eligible without an order, (3) ineligible due to prior HCV test or diagnosis, or (4) ineligible due to comorbidity (eg, metastatic cancer). For approximately one‐third of eligible patients, a study team member placed an order after review of the daily admission report because the order had not been automatically placed.

Admitting nurses initially asked for consent from eligible patients for HCV screening, but this was ultimately deemed too onerous a task along with all of their other duties. We then instituted opt‐out consent with patient education about testing and opportunities to refuse via posters placed throughout the hospital and flyers in admission packets. A bilingual HCV counselor provided HCV screening test results to all patients. She counseled patients who screened positive for HCV with the educational program on an electronic tablet and developed a follow‐up care plan.

A bilingual promotora (community health worker) contacted patients newly diagnosed with chronic HCV infection after hospital discharge to address the following: obtaining insurance, access to primary care and HCV specialty care, scheduling appointments, and treatment for alcohol problems or drug abuse. After obtaining signed consent, the promotora sent test results and recommendations for follow‐up care (eg, hepatitis A and B immunization) to a designated outpatient physician and reminded patients about appointments and pending tests. The promotora received training in motivational interviewing skills to engage patients with needed care including alcohol treatment.

Study Data

A summary report was developed from the EMR with demographic, insurance, clinical, and HCV screening data for all admitted baby boomers. For patients diagnosed with chronic HCV infection, the promotora obtained data about follow‐up HCV care through December 10, 2014 from the EMR, outside provider records, and patient reports.

Study Variables

The 2 outcome measures were a positive anti‐HCV antibody test and positive HCV RNA test. Insurance status was categorized as insured (private, public, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense) or uninsured (self‐pay or county‐based financial assistance program). Problem drinking was identified from International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes for the admission, notes by clinicians describing alcohol abuse/dependence, or quantity/frequency meeting National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism criteria for alcohol problems of >14 drinks/week or >4 drinks/day for men and >7 drinks per week or >3 drinks per day for women.[16]

Implementation costs included informatics support, mobile app development, other patient educational materials, costs of screening tests for uninsured, and 0.3 full‐time equivalent (FTE) of a clinician for half a year. Maintenance costs included salaries for the study team, HCV testing costs, and postage.

Analysis

Demographics by HCV antibody test results are compared using [2] tests or Student t tests as appropriate. Among persons with a positive HCV antibody test, HCV RNA results are similarly compared. This implementation project was approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Institutional Review Board (HSC20130033N).

RESULTS

Within 14 months, 6410 unique baby boomers were admitted with a mean age 56.4 years (standard deviation [SD] 5.7), 55.9% men, 59.1% Hispanic, 8.2% nonwhite, and 46.7% uninsured (Table 1). Among admitted patients, 729 (11.4%) had a previous HCV diagnosis and 1904 (29.7%) had been tested for HCV (Figure 1). Anti‐HCV antibody testing was completed for 3168 (49.4% of all admitted patients and 83.9% of never‐tested patients). After exclusions such as significant comorbidity or psychiatric admission, 95% of eligible persons were tested. Of screened patients, 240 (7.6%) were positive; these patients were significantly younger (P<0.0001) and more likely to be men (P<0.0001) and uninsured (P=0.002) (Table 1). Notably, 10% of men were anti‐HCV positive versus 4% of women. In this predominantly Hispanic cohort, no significant difference appeared by race‐ethnicity, but African Americans had a higher prevalence (10.4%) than other groups.

| Characteristic | All Screened Patients, No. | Anti‐HCV Antibody‐Positive Patients, No. (Row %) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overall | 3,168 | Total=240 (7.6) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 57.0 (5.7) | 54.8 (5.0) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 1,771 | 185 (10.4) | <0.0001 |

| Women | 1,397 | 55 (3.9) | |

| Race | |||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 1,036 | 86 (8.3) | 0.12 |

| Hispanic | 1,872 | 134 (7.2) | |

| African American | 163 | 17 (10.4) | |

| Other | 97 | 3 (3.1) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Insured | 1,740 | 109 (6.3) | 0.002 |

| Uninsured | 1,428 | 131 (9.2) | |

HCV RNA testing was completed for 214 (89.2%) anti‐HCVpositive patients, of whom 134 (62.6%) had detectable RNA, indicating chronic HCV infection (Figure 1). Overall, 4.2% of all eligible patients tested for HCV were chronically infected. No characteristics were significantly associated with chronic HCV, but persons with chronic infection tended to be younger, uninsured, and African American (Table 2).

| Characteristics | All HCV RNA‐Tested Patients, No. | HCV RNA‐Positive Patients, No. (Row %) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overall | 214 | 134 (62.6) | |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 54.6 (5.0) | 54.2 (5.1) | 0.09 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 165 | 106 (64.2) | 0.37 |

| Women | 49 | 28 (57.1) | |

| Race | |||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 78 | 49 (62.8) | 0.65 |

| Hispanic | 118 | 73 (61.8) | |

| African American | 15 | 11 (73.3) | |

| Other | 3 | 1 (33.3) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Insured | 92 | 52 (56.5) | 0.11 |

| Uninsured | 122 | 82 (67.2) | |

Among patients with chronic HCV infection, 129 (96.3%) were counseled and follow‐up plans developed (Figure 2). By December 10, 2014, 108 (80.6%) patients had received follow‐up primary care, and 52 (38.8%) had care from a hepatologist. Five had initiated HCV‐specific treatment, but many others were awaiting approval for compassionate drug programs offering direct‐acting antivirals. Barriers to care included 82 (61.2%) uninsured, 45 (34%) problem drinkers, 22 (16%) homeless, and 25 (18.6%) incarcerated (not shown). The promotora addressed these issues by visiting homes or homeless shelters, assistance with obtaining county‐based or other types of insurance, offering alcohol risk‐reduction counseling, linking patients to alcohol‐treatment programs, and communicating with the county jail about follow‐up care.

Most of the developmental costs for the program were dedicated to developing EMR programs (Table 3). An optional cost was for the development of the tablet educational program about HCV. In regard to maintenance costs for the first 14 months, the majority was to support the program faculty, counseling/case management, and a nurse practitioner who helped with ordering tests. We also estimated costs for testing uninsured patients (45% of HCV antibody tested, 57% of HCV PCR tested, per Tables 1 and 2, respectively), as they must be borne by the hospital.

| Program Component | Monthly ($) | Total ($) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Development phase (2 months prior to start) | ||

| Personnel | ||

| Faculty physicians (0.3 FTE salary+benefits) | 6,641 | 13,282 |

| Role: Development educational materials, provider education, and pilot testing | ||

| Technology | ||

| Development of eligibility screen and order sets for electronic medical record | 41,171 | |

| HCV counseling educational program for tabletdevelopment and pilot testing (optional) | 15,000 | |

| Patient educational materials (posters, flyers) | 400 | |

| Total for development phase | 69,853 | |

| Maintenance phase (14 months) | ||

| Personnel | ||

| Faculty physicians (0.3 FTE, salary+benefits) | 6,641 | 92,974 |

| Role: Coordinate with hospital staff and faculty, liaison with laboratory, supervise study team, review all identified cases for eligibility and management plans | ||

| Inpatient counselor and outpatient case management (2 FTE, salary+benefits) | 6,343 | 88,802 |

| Role: Inpatient and outpatient counseling of HCV Ab+patients and facilitation of follow‐up care for patients with chronic HCV infection | ||

| Nurse practitioner ($35/hour @ 10 hours/month) | 350 | 4,900 |

| Role: Review daily list of admitted baby boomers and manually order HCV screening test for those missed by the automated order | ||

| Postage | 10 | 140 |

| Laboratory costs for uninsured (based on % in cohort) | ||

| HCV antibody in plasma preparation tubes ($13.41/test 1,423) | 19,082 | |

| HCV RNA PCR ($87.96/test 122) | 10,731 | |

| Total for maintenance phase | 216,629 | |

| Total program costs | 286,482 | |

DISCUSSION

Implementation of universal HCV screening and linkage to care for hospitalized baby boomers utilizes a multicomponent infrastructure that reflects lessons learned from similar HIV programs. Use of an EMR algorithm to identify eligible patients and programs to automatically order HCV screening was a linchpin of our high testing rate and averted testing those who did not require screening. Of all 6410 baby boomers admitted to our safety‐net hospital, the EMR screen identified over 40% as ineligible due to prior diagnosis of HCV infection or prior HCV tests. Most of the additional 609 patients who were not tested were excluded due to comorbidities or admission to psychiatry. Overall, the EMR programs, tests ordered by the team, and opt‐out screening with education resulted in screening 95% of eligible patients. However, this program carries substantial costs, nearly $300,000 for the first 2 years, for unreimbursed services in this safety‐net hospital. The new guidelines for HCV screening[1, 2] are not accompanied by financial support either for program implementation or for screening and linkage to care for the uninsured, creating significant financial hurdles to achieve guideline compliance within already overtaxed public healthcare systems.

The infrastructure implemented in this hospital succeeded in achieving a higher rate of HCV screening of baby boomers than reported by other programs. In an emergency department in Birmingham, Alabama, a screening program for baby boomers tested 66% of 2325 persons who were HCV‐unaware.[17] In an outpatient clinic for men who have sex with men, only 54% of 1329 patients were screened for HCV.[18]

Among 3168 screened patients in our cohort, 7.6% were anti‐HCV antibody positive, which is over twice the prevalence of 3.5% (95% confidence interval: 2.2%‐4.8%) for anti‐HCVpositive tests in baby boomers based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2001 to 2010.[19] However, the Alabama emergency department study found that 11% of tested patients were anti‐HCV positive.[17] Although that study lacked race‐ethnicity data for half of the subjects, among those with this information, 13% of black and 7% of white subjects tested anti‐HCV positive. Compared with the Alabama study, the anti‐HCV prevalence in our cohort was somewhat lower for blacks (10.4%) but higher for non‐Hispanic whites (8.3%). Hispanics in our cohort had the lowest anti‐HCV prevalence (7.2%), whereas the Alabama study did not report this figure. National studies also find that the prevalence of anti‐HCVpositive results is twice as high for blacks compared with non‐Hispanic whites and Hispanics, and nearly twice as high for men compared with women.[19] In our cohort, the proportion of men with anti‐HCVpositive results was nearly 3 times that for women.

Diagnosis of chronic HCV infection requires 2 tests, similar to performing a Western blot test after a positive enzyme‐linked immunoassay for HIV. In a Veterans Affairs study, only 64% of patients with a positive anti‐HCV antibody test had a HCV RNA performed when reflex testing was not performed, and patients had to come in for a second test versus >90% of patients in sites that offer reflex testing.[20] At a somewhat increased price due to using more expensive PPTs ($96/100 PPT tubes vs $6.50/100 for serum red top tubes), both tests were performed on the same blood sample, resulting in 89% of anti‐HCV antibody‐positive patients being tested for HCV RNA.

Overall, 62% of patients in our cohort with a positive anti‐HCV antibody test had HCV RNA detected (viremic) compared with 71% of persons aged 20 years in an NHANES study from 2003 to 2010.[21] Several factors may contribute to this lower rate of chronic infection. In a study of HCV seropositive blood donors, Hispanics and non‐Hispanic whites were significantly more likely to have spontaneously cleared HCV infection than Asians and non‐Hispanic blacks.[22] Spontaneous clearance of HCV has also been associated with younger age at infection and HCV genotype 1.[23] Poorly understood genetic factors may also play a role.[24] The high rate of HCV clearance in our cohort reinforces the need to perform HCV RNA testing.

Overall, 4.2% of our cohort had chronic HCV infection. According to CDC estimates from 1999 to 2008 NHANES data, 2.74 million (3.25%) of 84.2 million US baby boomers have been infected with HCV, and 2.04 million (2.4%) have chronic infection.[1] Therefore, our safety‐net cohort of never‐tested baby boomers had over twice the prevalence of chronic HCV infection than the national estimate for this age group. This high proportion of chronic HCV may reflect our predominantly low‐income patient population. An analysis conducted by Milliman, Inc. using 2010 data estimated that half of all persons with undiagnosed HCV infection are uninsured.[25] This finding reinforces the need to conduct HCV screening in acute‐care settings such as hospitals, because the uninsured have poor access to ambulatory care.

Our chronic HCV‐infected cohort had many barriers to follow‐up care because most were uninsured and 15% were homeless. Our counselors addressed socioeconomic barriers to care[26] and concerns about the disease.[27] Many patients also had problem drinking based on either self‐report or documented in the medical record. Even moderate alcohol use may increase the risk of overall and liver‐related mortality from chronic HCV infection,[28] so our team offered brief alcohol counseling and partnered with healthcare providers and local Alcoholics Anonymous programs to offer support.

We linked 80% of newly diagnosed patients to primary care or hepatology providers, aided by a county‐level financial assistance program for healthcare services for uninsured residents, but it still required patients to pay out of pocket for care. Access to newer, highly effective, all‐oral therapy treatment[5] was slowed while awaiting US Food and Drug Administration approval in the first year of this project, then treatment provided only after lengthy applications to drug company assistance programs with priority given to persons with compensated cirrhosis.

Our project raises serious concerns for policymakers and payers. Should universal baby boomer HCV testing be undertaken without taking into account the financial and personnel resources required to implement this screening program or the substantial expenditures necessary to treat chronically infected persons? Although the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services pay for HCV screening costs,[29] our hospital had to cover costs for uninsured persons. Admittedly, Texas has the highest proportion of residents who are uninsured in the nation, but even in other states, Medicaid and other insurance programs are wrestling with how to deal with the high cost of HCV therapy.[30]

We acknowledge several limitations of this project. First, it was undertaken in only 1 hospital. Yet, our challenges and solutions are likely to be applicable to other hospitals nationally, especially those serving vulnerable populations. Second, patients in our cohort were usually admitted for comorbidities that needed to be managed before HCV infection could be addressed. However, persons with a poor prognosis, such as metastatic cancer, were excluded. We did not attempt to exclude other persons with serious comorbidities such as congestive heart failure, because the guidelines do not currently recommend this, and there may be benefits for patients, their families, and providers from knowing that an individual is chronically HCV infected even if they are not eligible to be treated. Third, the cost of the program was supported in part by a grant and would otherwise have to be borne by the hospital. Fourth, the EMR used by our hospital allows hundreds of admission order sets to be created and made automated order entry hard to implement. This is unlikely to be the situation in other hospitals using different types of EMRs.

It remains to be seen whether safety‐net hospitals with populations at greater risk of HCV infection can afford to support HCV testing and linkage to care. In view of several cost‐effectiveness studies that find screening and treating chronic HCV‐infected baby boomers cost‐effective within standard thresholds,[31, 32, 33] it may be important for policymakers and payers to consider lessons from HIV programs. Because HIV‐infected persons could not afford life‐saving medication, vigorous advocacy efforts led to legislation approving the Ryan White program in 1990 to fill gaps in HIV care that were not covered by other sources of support.[34] HCV infection is the most common blood‐borne infection in the nation, with potentially devastating consequences if ignored, but the underlying premise that universal HCV testing will save lives is in question if most of the individuals who are diagnosed with chronic HCV are low income, uninsured, or underinsured with limited access to curative medications. A rigorous public policy debate regarding both the merits of screening and the availability of treatment to those who are diagnosed is essential to the success of these programs.

Disclosure

Funding for this study was received from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC PS12‐1209PPHF12. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

INTRODUCTION

The baby boomer generation, born from 1945 to 1965, accounts for 75% of the estimated 2.7 to 3.9 million persons with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the US.[1, 2, 3] Most HCV‐infected baby boomers do not know that they are infected.[4] With the advent of better‐tolerated, more‐effective therapies to treat chronic HCV infection,[5] and to reduce rates of complications such as cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma,[6] universal 1‐time screening of baby boomers has been endorsed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the United States Preventive Services Task Force.[1, 7] Hospitalized baby boomers may offer an important target for HCV screening. Our group conducted an anonymous HCV seroprevalence study of nearly 800 patients on general medicine and trauma services of 2 Philadelphia hospitals, and found that 8% had undiagnosed HCV infection, and 8% had diagnosed HCV. [8]

Little is known about barriers and facilitators to implementation of universal HCV screening of baby boomers. Lessons from implementing HIV screening offer a useful guide.[9] First, limited clinician knowledge and confusion about screening guidelines necessitated convenient, well‐designed educational programs.[10] Second, burdensome consent procedures were reduced by opt‐out consent for screening supplemented by patient education.[9] Third, electronic medical record (EMR) algorithms minimized burdens on staff by efficiently identifying and flagging eligible persons for screening.[11] Fourth, ancillary staff support for patient education and linkage to follow‐up care increased screening rates compared with usual care by physicians/staff.[11] Finally, routine human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing of inpatients increased rates of diagnosis, especially compared with physician referral systems.[12]

This article describes how HIV screening strategies informed the development in a baby boomer HCV screening and linkage to a care program in a safety‐net hospital serving a majority Hispanic population. We report results of the first 14 months of the screening program and linkage to care for chronically HCV‐infected persons after a minimum 10 months follow‐up. We also estimate costs for program implementation and maintenance to inform hospital administrators, healthcare policymakers, and clinicians about resources that may be required to effectively screen hospitalized baby boomers for HCV.

METHODS

Study Setting

The HCV baby boomer screening program was pilot tested in November 2012 and launched December 1, 2012 in a 498‐bed academic‐affiliated hospital of a healthcare system serving the indigent population of South Texas.

Project Development Phase

From October 1, 2012 to November 30, 2012, project infrastructure development and provider/staff education were conducted. A half‐hour PowerPoint lecture (in person or online) was developed about HCV epidemiology, birth‐cohort HCV screening guidelines, newer treatment modalities, and screening program components. Lectures were delivered to departmental chairs at the affiliated medical school, departmental grand rounds, and the hospital's nursing supervisors. One‐on‐one informational meetings were also held with hospital administrators and staff.

With the hospital's information technology team, screens were developed to identify eligible baby boomers from up to 7 years of previous inpatient and outpatient encounters in the EMR from: birth year (19451965) and no prior diagnosis of HCV infection (070.41, 070.44, 070.51, 070.54, 070.7x, V02.62) or any type of completed test for HCV. The algorithm also excluded patients admitted to psychiatry due to lack of decision‐making capacity or patients with a poor prognosis such as metastatic cancer. An audit of 100 consecutive excluded patients identified all as legitimate.

A new laboratory order for HCV screening was developed by laboratory administrators and pathology faculty for an anti‐HCV antibody test followed by reflex HCV RNA testing for positive results per CDC recommendations.[13] The anti‐HCV test was performed on serum or ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid plasma using the Advia Centaur HCV Assay (Bayer HealthCare LLC, Tarrytown, NY). This assay has excellent sensitivity (99.9%) and specificity (97.5%).[14, 15] The HCV RNA assay was performed using quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan HCV test (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA). Use of plasma preparation tubes (PPTs) (BD Vacutainer PPT tubes; Becton, Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ) permitted both anti‐HCV antibody and HCV PCR testing to be performed on the same specimen when anti‐HCV antibody was detected, eliminating a second blood draw for the PCR test. For patients eligible for screening, an EMR algorithm was created to add an HCV screening order to over 50 different admission order sets.

To educate patients newly diagnosed with HCV infection, we developed an interactive, low‐literacy, educational program in Spanish and English for an electronic tablet device that addressed: HCV epidemiology, transmission prevention, factors that can accelerate chronic HCV infection, and management/treatment strategies. At several points in the program, the patient needed to answer questions correctly to continue. The tablet retained responses linked to a study identification about alcohol consumption, history of past and current illicit drug use, sexual risk behavior, and offered risk reduction messages. The tablet content and presentation reflected suggestions by Hispanic patient‐reviewers about cultural appropriateness and comprehension.

Project Implementation and Maintenance Phase

We report implementation of the program from December 1, 2012 to January 31, 2014. An automated EMR report classified all baby boomers admitted in the previous 24 hours as: (1) eligible with pending screening test order, (2) eligible without an order, (3) ineligible due to prior HCV test or diagnosis, or (4) ineligible due to comorbidity (eg, metastatic cancer). For approximately one‐third of eligible patients, a study team member placed an order after review of the daily admission report because the order had not been automatically placed.

Admitting nurses initially asked for consent from eligible patients for HCV screening, but this was ultimately deemed too onerous a task along with all of their other duties. We then instituted opt‐out consent with patient education about testing and opportunities to refuse via posters placed throughout the hospital and flyers in admission packets. A bilingual HCV counselor provided HCV screening test results to all patients. She counseled patients who screened positive for HCV with the educational program on an electronic tablet and developed a follow‐up care plan.

A bilingual promotora (community health worker) contacted patients newly diagnosed with chronic HCV infection after hospital discharge to address the following: obtaining insurance, access to primary care and HCV specialty care, scheduling appointments, and treatment for alcohol problems or drug abuse. After obtaining signed consent, the promotora sent test results and recommendations for follow‐up care (eg, hepatitis A and B immunization) to a designated outpatient physician and reminded patients about appointments and pending tests. The promotora received training in motivational interviewing skills to engage patients with needed care including alcohol treatment.

Study Data

A summary report was developed from the EMR with demographic, insurance, clinical, and HCV screening data for all admitted baby boomers. For patients diagnosed with chronic HCV infection, the promotora obtained data about follow‐up HCV care through December 10, 2014 from the EMR, outside provider records, and patient reports.

Study Variables

The 2 outcome measures were a positive anti‐HCV antibody test and positive HCV RNA test. Insurance status was categorized as insured (private, public, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense) or uninsured (self‐pay or county‐based financial assistance program). Problem drinking was identified from International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes for the admission, notes by clinicians describing alcohol abuse/dependence, or quantity/frequency meeting National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism criteria for alcohol problems of >14 drinks/week or >4 drinks/day for men and >7 drinks per week or >3 drinks per day for women.[16]

Implementation costs included informatics support, mobile app development, other patient educational materials, costs of screening tests for uninsured, and 0.3 full‐time equivalent (FTE) of a clinician for half a year. Maintenance costs included salaries for the study team, HCV testing costs, and postage.

Analysis

Demographics by HCV antibody test results are compared using [2] tests or Student t tests as appropriate. Among persons with a positive HCV antibody test, HCV RNA results are similarly compared. This implementation project was approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Institutional Review Board (HSC20130033N).

RESULTS

Within 14 months, 6410 unique baby boomers were admitted with a mean age 56.4 years (standard deviation [SD] 5.7), 55.9% men, 59.1% Hispanic, 8.2% nonwhite, and 46.7% uninsured (Table 1). Among admitted patients, 729 (11.4%) had a previous HCV diagnosis and 1904 (29.7%) had been tested for HCV (Figure 1). Anti‐HCV antibody testing was completed for 3168 (49.4% of all admitted patients and 83.9% of never‐tested patients). After exclusions such as significant comorbidity or psychiatric admission, 95% of eligible persons were tested. Of screened patients, 240 (7.6%) were positive; these patients were significantly younger (P<0.0001) and more likely to be men (P<0.0001) and uninsured (P=0.002) (Table 1). Notably, 10% of men were anti‐HCV positive versus 4% of women. In this predominantly Hispanic cohort, no significant difference appeared by race‐ethnicity, but African Americans had a higher prevalence (10.4%) than other groups.

| Characteristic | All Screened Patients, No. | Anti‐HCV Antibody‐Positive Patients, No. (Row %) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overall | 3,168 | Total=240 (7.6) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 57.0 (5.7) | 54.8 (5.0) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 1,771 | 185 (10.4) | <0.0001 |

| Women | 1,397 | 55 (3.9) | |

| Race | |||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 1,036 | 86 (8.3) | 0.12 |

| Hispanic | 1,872 | 134 (7.2) | |

| African American | 163 | 17 (10.4) | |

| Other | 97 | 3 (3.1) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Insured | 1,740 | 109 (6.3) | 0.002 |

| Uninsured | 1,428 | 131 (9.2) | |

HCV RNA testing was completed for 214 (89.2%) anti‐HCVpositive patients, of whom 134 (62.6%) had detectable RNA, indicating chronic HCV infection (Figure 1). Overall, 4.2% of all eligible patients tested for HCV were chronically infected. No characteristics were significantly associated with chronic HCV, but persons with chronic infection tended to be younger, uninsured, and African American (Table 2).

| Characteristics | All HCV RNA‐Tested Patients, No. | HCV RNA‐Positive Patients, No. (Row %) | P Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Overall | 214 | 134 (62.6) | |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 54.6 (5.0) | 54.2 (5.1) | 0.09 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 165 | 106 (64.2) | 0.37 |

| Women | 49 | 28 (57.1) | |

| Race | |||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 78 | 49 (62.8) | 0.65 |

| Hispanic | 118 | 73 (61.8) | |

| African American | 15 | 11 (73.3) | |

| Other | 3 | 1 (33.3) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Insured | 92 | 52 (56.5) | 0.11 |

| Uninsured | 122 | 82 (67.2) | |

Among patients with chronic HCV infection, 129 (96.3%) were counseled and follow‐up plans developed (Figure 2). By December 10, 2014, 108 (80.6%) patients had received follow‐up primary care, and 52 (38.8%) had care from a hepatologist. Five had initiated HCV‐specific treatment, but many others were awaiting approval for compassionate drug programs offering direct‐acting antivirals. Barriers to care included 82 (61.2%) uninsured, 45 (34%) problem drinkers, 22 (16%) homeless, and 25 (18.6%) incarcerated (not shown). The promotora addressed these issues by visiting homes or homeless shelters, assistance with obtaining county‐based or other types of insurance, offering alcohol risk‐reduction counseling, linking patients to alcohol‐treatment programs, and communicating with the county jail about follow‐up care.

Most of the developmental costs for the program were dedicated to developing EMR programs (Table 3). An optional cost was for the development of the tablet educational program about HCV. In regard to maintenance costs for the first 14 months, the majority was to support the program faculty, counseling/case management, and a nurse practitioner who helped with ordering tests. We also estimated costs for testing uninsured patients (45% of HCV antibody tested, 57% of HCV PCR tested, per Tables 1 and 2, respectively), as they must be borne by the hospital.

| Program Component | Monthly ($) | Total ($) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Development phase (2 months prior to start) | ||

| Personnel | ||

| Faculty physicians (0.3 FTE salary+benefits) | 6,641 | 13,282 |

| Role: Development educational materials, provider education, and pilot testing | ||

| Technology | ||

| Development of eligibility screen and order sets for electronic medical record | 41,171 | |

| HCV counseling educational program for tabletdevelopment and pilot testing (optional) | 15,000 | |

| Patient educational materials (posters, flyers) | 400 | |

| Total for development phase | 69,853 | |

| Maintenance phase (14 months) | ||

| Personnel | ||

| Faculty physicians (0.3 FTE, salary+benefits) | 6,641 | 92,974 |

| Role: Coordinate with hospital staff and faculty, liaison with laboratory, supervise study team, review all identified cases for eligibility and management plans | ||

| Inpatient counselor and outpatient case management (2 FTE, salary+benefits) | 6,343 | 88,802 |

| Role: Inpatient and outpatient counseling of HCV Ab+patients and facilitation of follow‐up care for patients with chronic HCV infection | ||

| Nurse practitioner ($35/hour @ 10 hours/month) | 350 | 4,900 |

| Role: Review daily list of admitted baby boomers and manually order HCV screening test for those missed by the automated order | ||

| Postage | 10 | 140 |

| Laboratory costs for uninsured (based on % in cohort) | ||

| HCV antibody in plasma preparation tubes ($13.41/test 1,423) | 19,082 | |

| HCV RNA PCR ($87.96/test 122) | 10,731 | |

| Total for maintenance phase | 216,629 | |

| Total program costs | 286,482 | |

DISCUSSION

Implementation of universal HCV screening and linkage to care for hospitalized baby boomers utilizes a multicomponent infrastructure that reflects lessons learned from similar HIV programs. Use of an EMR algorithm to identify eligible patients and programs to automatically order HCV screening was a linchpin of our high testing rate and averted testing those who did not require screening. Of all 6410 baby boomers admitted to our safety‐net hospital, the EMR screen identified over 40% as ineligible due to prior diagnosis of HCV infection or prior HCV tests. Most of the additional 609 patients who were not tested were excluded due to comorbidities or admission to psychiatry. Overall, the EMR programs, tests ordered by the team, and opt‐out screening with education resulted in screening 95% of eligible patients. However, this program carries substantial costs, nearly $300,000 for the first 2 years, for unreimbursed services in this safety‐net hospital. The new guidelines for HCV screening[1, 2] are not accompanied by financial support either for program implementation or for screening and linkage to care for the uninsured, creating significant financial hurdles to achieve guideline compliance within already overtaxed public healthcare systems.

The infrastructure implemented in this hospital succeeded in achieving a higher rate of HCV screening of baby boomers than reported by other programs. In an emergency department in Birmingham, Alabama, a screening program for baby boomers tested 66% of 2325 persons who were HCV‐unaware.[17] In an outpatient clinic for men who have sex with men, only 54% of 1329 patients were screened for HCV.[18]

Among 3168 screened patients in our cohort, 7.6% were anti‐HCV antibody positive, which is over twice the prevalence of 3.5% (95% confidence interval: 2.2%‐4.8%) for anti‐HCVpositive tests in baby boomers based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2001 to 2010.[19] However, the Alabama emergency department study found that 11% of tested patients were anti‐HCV positive.[17] Although that study lacked race‐ethnicity data for half of the subjects, among those with this information, 13% of black and 7% of white subjects tested anti‐HCV positive. Compared with the Alabama study, the anti‐HCV prevalence in our cohort was somewhat lower for blacks (10.4%) but higher for non‐Hispanic whites (8.3%). Hispanics in our cohort had the lowest anti‐HCV prevalence (7.2%), whereas the Alabama study did not report this figure. National studies also find that the prevalence of anti‐HCVpositive results is twice as high for blacks compared with non‐Hispanic whites and Hispanics, and nearly twice as high for men compared with women.[19] In our cohort, the proportion of men with anti‐HCVpositive results was nearly 3 times that for women.

Diagnosis of chronic HCV infection requires 2 tests, similar to performing a Western blot test after a positive enzyme‐linked immunoassay for HIV. In a Veterans Affairs study, only 64% of patients with a positive anti‐HCV antibody test had a HCV RNA performed when reflex testing was not performed, and patients had to come in for a second test versus >90% of patients in sites that offer reflex testing.[20] At a somewhat increased price due to using more expensive PPTs ($96/100 PPT tubes vs $6.50/100 for serum red top tubes), both tests were performed on the same blood sample, resulting in 89% of anti‐HCV antibody‐positive patients being tested for HCV RNA.

Overall, 62% of patients in our cohort with a positive anti‐HCV antibody test had HCV RNA detected (viremic) compared with 71% of persons aged 20 years in an NHANES study from 2003 to 2010.[21] Several factors may contribute to this lower rate of chronic infection. In a study of HCV seropositive blood donors, Hispanics and non‐Hispanic whites were significantly more likely to have spontaneously cleared HCV infection than Asians and non‐Hispanic blacks.[22] Spontaneous clearance of HCV has also been associated with younger age at infection and HCV genotype 1.[23] Poorly understood genetic factors may also play a role.[24] The high rate of HCV clearance in our cohort reinforces the need to perform HCV RNA testing.

Overall, 4.2% of our cohort had chronic HCV infection. According to CDC estimates from 1999 to 2008 NHANES data, 2.74 million (3.25%) of 84.2 million US baby boomers have been infected with HCV, and 2.04 million (2.4%) have chronic infection.[1] Therefore, our safety‐net cohort of never‐tested baby boomers had over twice the prevalence of chronic HCV infection than the national estimate for this age group. This high proportion of chronic HCV may reflect our predominantly low‐income patient population. An analysis conducted by Milliman, Inc. using 2010 data estimated that half of all persons with undiagnosed HCV infection are uninsured.[25] This finding reinforces the need to conduct HCV screening in acute‐care settings such as hospitals, because the uninsured have poor access to ambulatory care.

Our chronic HCV‐infected cohort had many barriers to follow‐up care because most were uninsured and 15% were homeless. Our counselors addressed socioeconomic barriers to care[26] and concerns about the disease.[27] Many patients also had problem drinking based on either self‐report or documented in the medical record. Even moderate alcohol use may increase the risk of overall and liver‐related mortality from chronic HCV infection,[28] so our team offered brief alcohol counseling and partnered with healthcare providers and local Alcoholics Anonymous programs to offer support.

We linked 80% of newly diagnosed patients to primary care or hepatology providers, aided by a county‐level financial assistance program for healthcare services for uninsured residents, but it still required patients to pay out of pocket for care. Access to newer, highly effective, all‐oral therapy treatment[5] was slowed while awaiting US Food and Drug Administration approval in the first year of this project, then treatment provided only after lengthy applications to drug company assistance programs with priority given to persons with compensated cirrhosis.

Our project raises serious concerns for policymakers and payers. Should universal baby boomer HCV testing be undertaken without taking into account the financial and personnel resources required to implement this screening program or the substantial expenditures necessary to treat chronically infected persons? Although the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services pay for HCV screening costs,[29] our hospital had to cover costs for uninsured persons. Admittedly, Texas has the highest proportion of residents who are uninsured in the nation, but even in other states, Medicaid and other insurance programs are wrestling with how to deal with the high cost of HCV therapy.[30]

We acknowledge several limitations of this project. First, it was undertaken in only 1 hospital. Yet, our challenges and solutions are likely to be applicable to other hospitals nationally, especially those serving vulnerable populations. Second, patients in our cohort were usually admitted for comorbidities that needed to be managed before HCV infection could be addressed. However, persons with a poor prognosis, such as metastatic cancer, were excluded. We did not attempt to exclude other persons with serious comorbidities such as congestive heart failure, because the guidelines do not currently recommend this, and there may be benefits for patients, their families, and providers from knowing that an individual is chronically HCV infected even if they are not eligible to be treated. Third, the cost of the program was supported in part by a grant and would otherwise have to be borne by the hospital. Fourth, the EMR used by our hospital allows hundreds of admission order sets to be created and made automated order entry hard to implement. This is unlikely to be the situation in other hospitals using different types of EMRs.

It remains to be seen whether safety‐net hospitals with populations at greater risk of HCV infection can afford to support HCV testing and linkage to care. In view of several cost‐effectiveness studies that find screening and treating chronic HCV‐infected baby boomers cost‐effective within standard thresholds,[31, 32, 33] it may be important for policymakers and payers to consider lessons from HIV programs. Because HIV‐infected persons could not afford life‐saving medication, vigorous advocacy efforts led to legislation approving the Ryan White program in 1990 to fill gaps in HIV care that were not covered by other sources of support.[34] HCV infection is the most common blood‐borne infection in the nation, with potentially devastating consequences if ignored, but the underlying premise that universal HCV testing will save lives is in question if most of the individuals who are diagnosed with chronic HCV are low income, uninsured, or underinsured with limited access to curative medications. A rigorous public policy debate regarding both the merits of screening and the availability of treatment to those who are diagnosed is essential to the success of these programs.

Disclosure

Funding for this study was received from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC PS12‐1209PPHF12. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , , , Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945–1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61:1–32.

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: evaluation of hepatitis C virus infection testing and reporting–eight U.S. sites, 2005‐2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:357–361.

- , , , , Hepatitis C virus infection in USA: an estimate of true prevalence. Liver Int. 2011;31:1090–1101.