User login

Erythematous Papules on the Ears

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

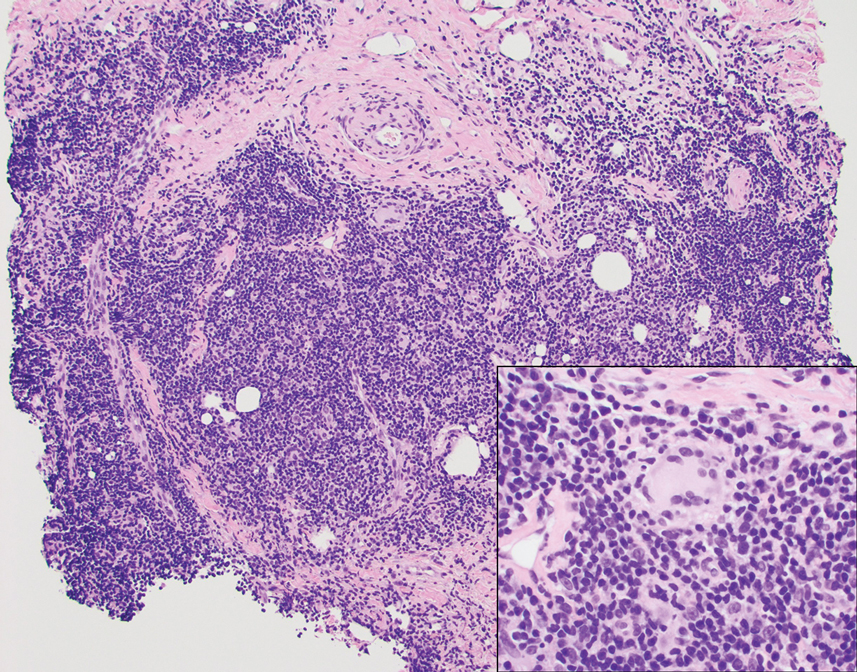

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

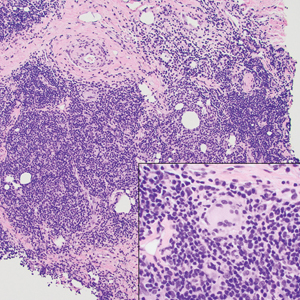

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

The Diagnosis: Borrelial Lymphocytoma (Lymphocytoma Cutis)

A punch biopsy revealed an atypical lobular lymphoid infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissue with a mixed composition of CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells (quiz image, bottom). Immunohistochemical studies revealed a normal CD4:CD8 ratio with preservation of CD5 and CD7. CD30 was largely negative. CD21 failed to detect follicular dendritic cell networks, and κ/λ light chain staining confirmed a preserved ratio of polytypic plasma cells. There was limited staining with B-cell lymphoma (Bcl-2 and Bcl-6). Polymerase chain reaction studies for both T- and B-cell receptors were negative (polyclonal).

Lyme disease is the most frequently reported vectorborne infectious disease in the United States, and borrelial lymphocytoma (BL) is a rare clinical sequela. Borrelial lymphocytoma is a variant of lymphocytoma cutis (also known as benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia), which is an inflammatory lesion that can mimic malignant lymphoma clinically and histologically. Lymphocytoma cutis is considered the prototypical example of cutaneous B-cell pseudolymphoma.1 Due to suspicion for lymphocytoma cutis based on the histologic findings and characteristic location of the lesions in our patient, Lyme serologies were ordered and were positive for IgM antibodies against p23, p39, and p41 antigens in high titers. Our patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 3 weeks with complete resolution of the lesions at 3-month follow-up.

Clinically, BL appears as erythematous papules, plaques, or nodules commonly on the lobules of the ears (quiz image, top). Most cases of lymphocytoma cutis are idiopathic but may be triggered by identifiable associated etiologies including Borrelia burgdorferi, Leishmania donovani, molluscum contagiosum, herpes zoster virus, vaccinations, tattoos, insect bites, and drugs. The main differential diagnosis of lymphocytoma cutis is cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Pseudolymphoma of the skin can mimic nearly all immunohistochemical staining patterns of true B-cell lymphomas.2

Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma frequently occurs on the head and neck. This true lymphoma of the skin can demonstrate prominent follicle centers with centrocytes and fragmented germinal centers (Figure 1) or show a diffuse pattern.3 Most cases show conspicuous Bcl-6 staining, and IgH gene rearrangements can detect a clonal B-cell population in more than 50% of cases.4

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma can occur as a primary cutaneous malignancy or as a manifestation of systemic disease.4 When arising in the skin, lesions tend to affect the extremities, and the disease is classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type. Histologically, sheets of large atypical lymphocytes with numerous mitoses are seen (Figure 2). These cells stain positively with Bcl-2 and frequently demonstrate Bcl-6 and MUM-1, none of which were seen in our case.4 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) tends to present with relapsing erythematous papules. Patients occasionally develop LyP in association with mycosis fungoides or other lymphomas. Both LyP and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma demonstrate conspicuous CD30+ large cells that can be multinucleated or resemble the Reed-Sternberg cells seen in Hodgkin lymphoma (Figure 3).4 Arthropod bite reactions are common but may be confused with lymphomas and pseudolymphomas. The perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate seen in arthropod bite reactions may be dense and usually is associated with numerous eosinophils (Figure 4). Occasional plasma cells also can be seen, and if the infiltrate closely adheres to vascular structures, a diagnosis of erythema chronicum migrans also can be considered. Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma may demonstrate exaggerated or persistent arthropod bite reactions, and atypical lymphocytes can be detected admixed with the otherwise reactive infiltrate.4

Borrelia burgdorferi is primarily endemic to North America and Europe. It is a spirochete bacterium spread by the Ixodes tick that was first recognized as the etiologic agent in 1975 in Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it received its name.5 Most reported cases of Lyme disease occur in the northeastern United States, which correlates with this case given our patient’s place of residence.6 Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis occurs in areas endemic for the Ixodes tick in Europe and North America.7 When describing the genotyping of Borrelia seen in BL, the strain B burgdorferi previously was grouped with Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii.2 In the contemporary literature, however, B burgdorferi is referred to as sensu stricto when specifically talking about the strain B burgdorferi, and the term sensu lato is used when referencing the combination of strains (B burgdorferi, B afzelii, B garinii).

A 2016 study by Maraspin et al8 comprising 144 patients diagnosed with BL showed that the lesions mainly were located on the breast (106 patients [73.6%]) and the earlobe (27 patients [18.8%]), with the remaining cases occurring elsewhere on the body (11 patients [7.6%]). The Borrelia strains isolated from the BL lesions included B afzelii, Borrelia bissettii, and B garinii, with B afzelii being the most commonly identified (84.6% [11/13]).8

Borrelial lymphocytoma usually is categorized as a form of early disseminated Lyme disease and is treated as such. The treatment of choice for early disseminated Lyme disease is doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days. Ceftriaxone and azithromycin are reasonable treatment options for patients who have tetracycline allergies or who are pregnant.9

In conclusion, the presentation of red papules or nodules on the ears should prompt clinical suspicion of Lyme disease, particularly in endemic areas. Differentiating pseudolymphomas from true lymphomas and other reactive conditions can be challenging.

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

- Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi:10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

- Colli C, Leinweber B, Müllegger R, et al. Borrelia burgdorferiassociated lymphocytoma cutis: clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of 106 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:232-240. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2003.00167.x

- Wehbe AM, Neppalli V, Syrbu S, et al. Diffuse follicle centre lymphoma presents with high frequency of extranodal disease. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(15 suppl):19511. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.26.15_suppl.19511

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Cutaneous infiltrates—lymphomatous and leukemic. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1171-1217.

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, De la Cruz-Valadez E, Ocampo -Candiani J, et al. Clinical spectrum of Lyme disease. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:201-208. doi:10.1007/s10096-018-3417-1

- Shapiro ED, Gerber MA. Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:533-542. doi:10.1086/313982

- Kandhari R, Kandhari S, Jain S. Borrelial lymphocytoma cutis: a diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:595-597. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.143530

- Maraspin V, Nahtigal Klevišar M, Ružic´-Sabljic´ E, et al. Borrelial lymphocytoma in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:914-921. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw417

- Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of Lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-1134. doi:10.1086/508667

A 53-year-old man with a history of atopic dermatitis presented with pain and redness of the lobules of both ears of 9 months’ duration. He had no known allergies and took no medications. He lived in suburban Virginia and had not recently traveled outside of the region. Physical examination revealed tender erythematous and edematous nodules on the lobules of both ears (top). There was no evidence of arthritis or neurologic deficits. A punch biopsy was performed (bottom).

Blisters in a Comatose Elderly Woman

The Diagnosis: Coma Blisters

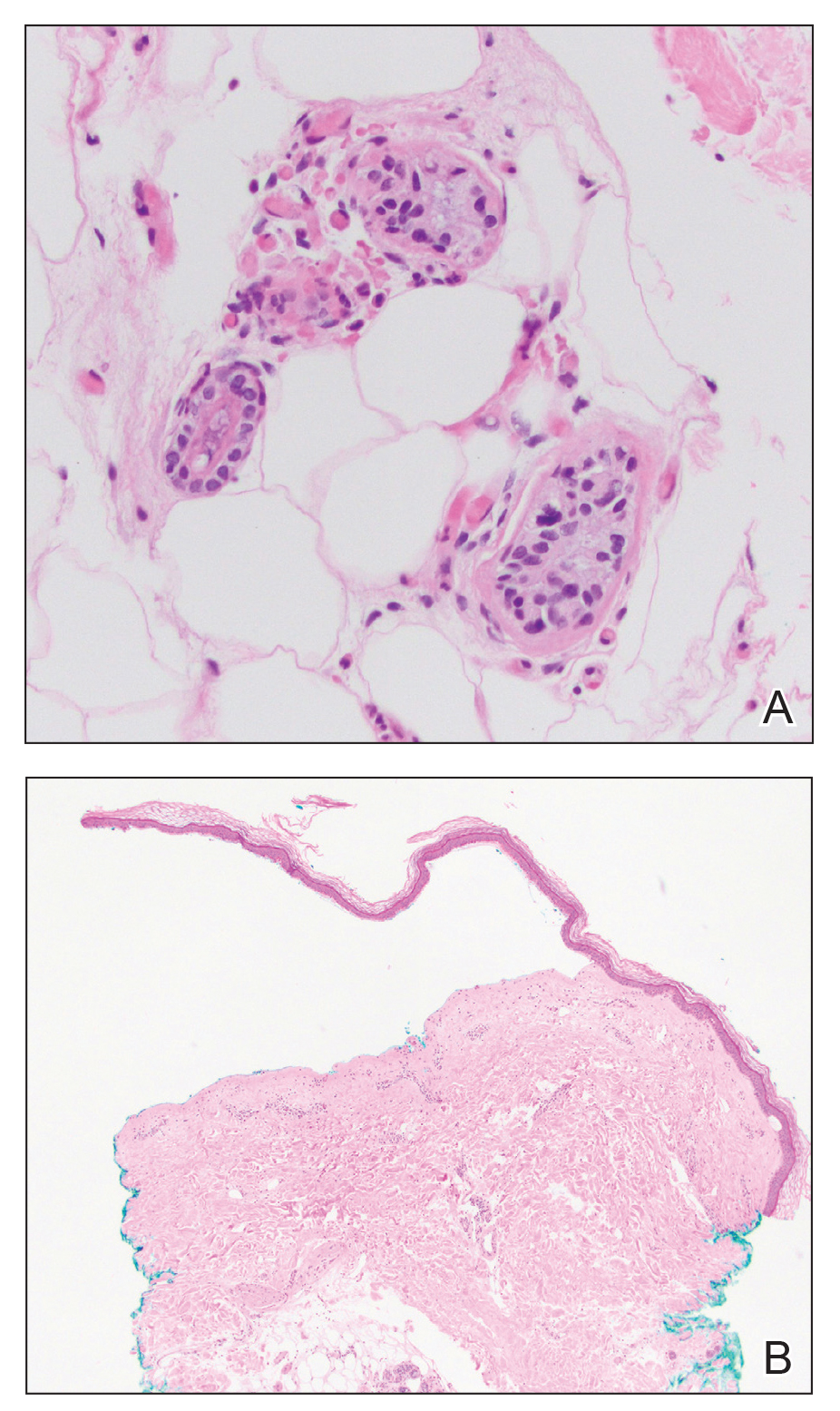

Histologic examination revealed pauci-inflammatory subepidermal blisters with swelling of eccrine cells, signaling impending gland necrosis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence testing on perilesional skin was negative. These findings would be inconsistent for diagnoses of edema blisters (most commonly seen in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic lower extremity edema), friction blisters (intraepidermal blisters seen on histopathology), and bullous pemphigoid (linear IgG and/or C3 staining along the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence testing is characteristic). Although eccrine gland alterations have been seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis,1 the mucous membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases, making the diagnosis less likely. Furthermore, interface changes including prominent keratinocyte necrosis were not seen on histology.

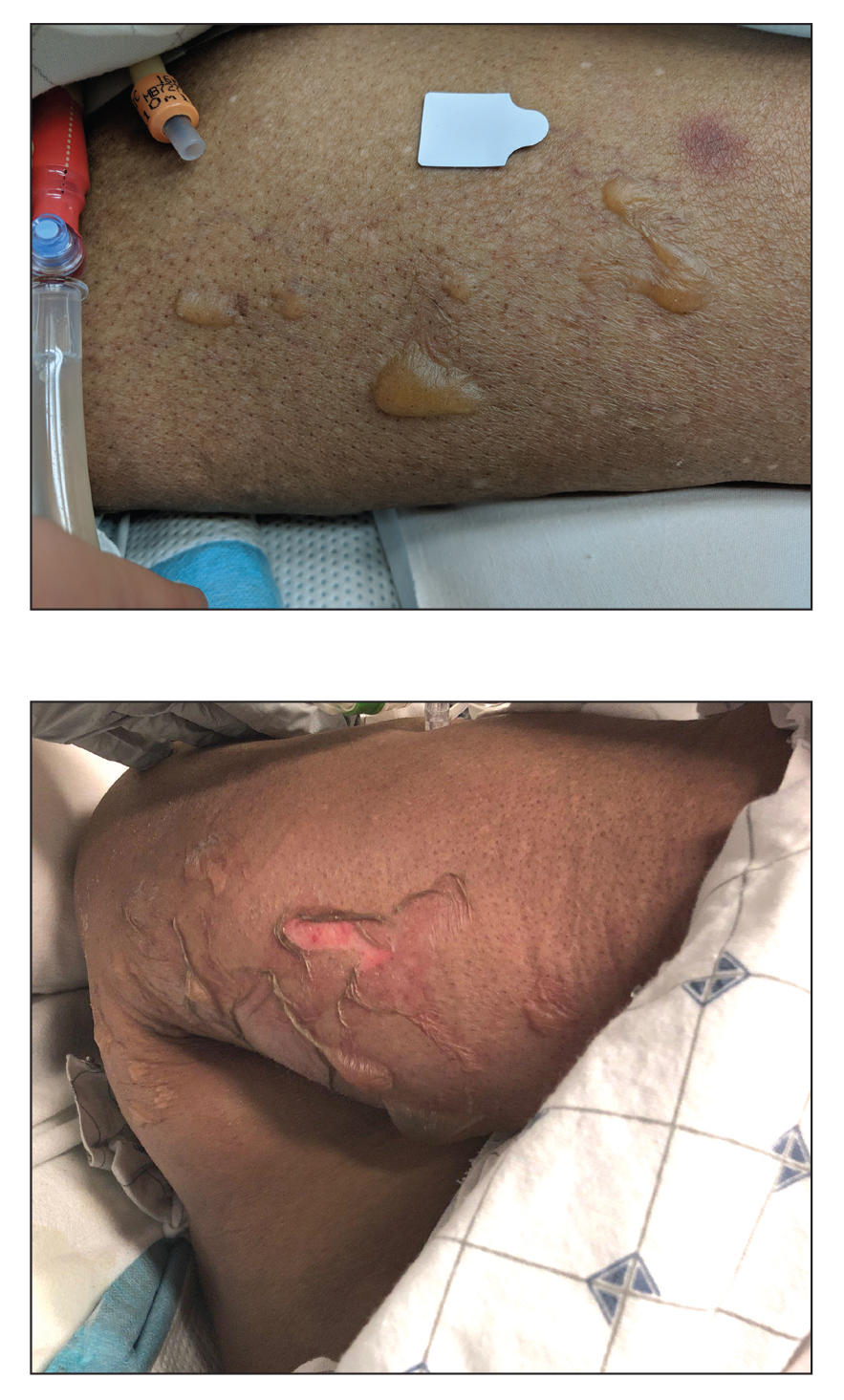

Given the localized nature of the lesions in our patient and negative direct immunofluorescence studies, a diagnosis of coma blisters was made. Gentle wound care practices to the areas of denuded skin were implemented with complete resolution. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and she was extubated and discharged home.

Coma blisters are self-limited bullous lesions that have been reported in comatose patients as early as 1812 when Napoleon’s surgeon first noticed cutaneous blisters in comatose French soldiers being treated for carbon monoxide intoxication.2 Since then, barbiturate overdose has remained the most common association, but coma blisters have occurred in the absence of specific drug exposures. Clinically, erythematous or violaceous plaques typically appear within 24 hours of drug ingestion, and progression to large tense bullae usually occurs within 48 to 72 hours of unconsciousness.3 They characteristically occur in pressure-dependent areas, but reports have shown lesions in non–pressure-dependent areas, including the penis and mouth.1,4 Spontaneous resolution within 1 to 2 weeks is typical.5

The underlying pathogenesis remains controversial, as multiple mechanisms have been suggested, but clear causal evidence is lacking. The original proposition that direct effects of drug toxicity caused the cutaneous observations was later refuted after similar bullous lesions with eccrine gland necrosis were reported in comatose patients with neurologic conditions.6 It is largely accepted that pressure-induced local ischemia—proportional to the duration and amount of pressure—leads to tissue injury and is critical to the pathogenesis. During periods of ischemia, the most metabolically active tissues will undergo necrosis first; however, in eccrine glands, the earliest and most severe damage does not seem to occur in the most metabolically active cells.7 Additionally, this would not provide a viable explanation for coma blisters with eccrine gland necrosis developing in variable non–pressuredependent areas.

Moreover, drug- and non–drug-induced coma blisters can appear identically, but specific histopathologic differences have been reported. The most notable markers of non–drug-induced coma blisters are the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in the epidermis and the presence of thrombosis in dermal vessels.8 Demonstration of necrotic changes in the secretory portion of the eccrine gland is considered the histopathologic hallmark for drug-induced coma blisters, but other findings can include subepidermal or intraepidermal bullae; perivascular infiltrates; and focal necrosis of the epidermis, dermis, subcutis, or epidermal appendages.6 Arteriolar wall necrosis and dermal inflammatory infiltrates also have been observed.7

Benzodiazepines have been widely prescribed and abused since their development, and overdose is much more common today than with barbiturates.9 Coma blisters rarely have been documented in the setting of isolated benzodiazepine overdose, and of the few cases, only one report implicated lorazepam as the causative agent.4,7 The characteristic finding of eccrine gland necrosis consistently was seen in our patient. This case not only emphasizes the need for greater awareness of the association between benzodiazepine overdose and coma blisters but also the importance of clinical context when considering diagnoses. It is essential to note that coma blisters themselves are nonspecific, and the diagnosis of drug-induced coma blisters warrants confirmatory toxicologic analysis.

- Ferreli C, Sulica VI, Aste N, et al. Drug-induced sweat gland necrosis in a non-comatose patient: a case presentation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:443-445.

- Larrey DJ. Memoires de Chirurgie Militaire et Campagnes. Smith and Buisson; 1812.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Varma AJ, Fisher BK, Sarin MK. Diazepam-induced coma with bullae and eccrine sweat gland necrosis. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:1207-1210.

- Rocha J, Pereira T, Ventura F, et al. Coma blisters. Case Rep Dermatol. 2009;1:66-70.

- Arndt KA, Mihm MC, Parrish JA. Bullae: a cutaneous sign of a variety of neurologic diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1973;60:312-320.

- Sánchez Yus E, Requena L, Simón P. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:208-216.

- Kato N, Ueno H, Mimura M. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in non-drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:344-350.

- Kang M, Ghassemzadeh S. Benzodiazepine Toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

The Diagnosis: Coma Blisters

Histologic examination revealed pauci-inflammatory subepidermal blisters with swelling of eccrine cells, signaling impending gland necrosis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence testing on perilesional skin was negative. These findings would be inconsistent for diagnoses of edema blisters (most commonly seen in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic lower extremity edema), friction blisters (intraepidermal blisters seen on histopathology), and bullous pemphigoid (linear IgG and/or C3 staining along the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence testing is characteristic). Although eccrine gland alterations have been seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis,1 the mucous membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases, making the diagnosis less likely. Furthermore, interface changes including prominent keratinocyte necrosis were not seen on histology.

Given the localized nature of the lesions in our patient and negative direct immunofluorescence studies, a diagnosis of coma blisters was made. Gentle wound care practices to the areas of denuded skin were implemented with complete resolution. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and she was extubated and discharged home.

Coma blisters are self-limited bullous lesions that have been reported in comatose patients as early as 1812 when Napoleon’s surgeon first noticed cutaneous blisters in comatose French soldiers being treated for carbon monoxide intoxication.2 Since then, barbiturate overdose has remained the most common association, but coma blisters have occurred in the absence of specific drug exposures. Clinically, erythematous or violaceous plaques typically appear within 24 hours of drug ingestion, and progression to large tense bullae usually occurs within 48 to 72 hours of unconsciousness.3 They characteristically occur in pressure-dependent areas, but reports have shown lesions in non–pressure-dependent areas, including the penis and mouth.1,4 Spontaneous resolution within 1 to 2 weeks is typical.5

The underlying pathogenesis remains controversial, as multiple mechanisms have been suggested, but clear causal evidence is lacking. The original proposition that direct effects of drug toxicity caused the cutaneous observations was later refuted after similar bullous lesions with eccrine gland necrosis were reported in comatose patients with neurologic conditions.6 It is largely accepted that pressure-induced local ischemia—proportional to the duration and amount of pressure—leads to tissue injury and is critical to the pathogenesis. During periods of ischemia, the most metabolically active tissues will undergo necrosis first; however, in eccrine glands, the earliest and most severe damage does not seem to occur in the most metabolically active cells.7 Additionally, this would not provide a viable explanation for coma blisters with eccrine gland necrosis developing in variable non–pressuredependent areas.

Moreover, drug- and non–drug-induced coma blisters can appear identically, but specific histopathologic differences have been reported. The most notable markers of non–drug-induced coma blisters are the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in the epidermis and the presence of thrombosis in dermal vessels.8 Demonstration of necrotic changes in the secretory portion of the eccrine gland is considered the histopathologic hallmark for drug-induced coma blisters, but other findings can include subepidermal or intraepidermal bullae; perivascular infiltrates; and focal necrosis of the epidermis, dermis, subcutis, or epidermal appendages.6 Arteriolar wall necrosis and dermal inflammatory infiltrates also have been observed.7

Benzodiazepines have been widely prescribed and abused since their development, and overdose is much more common today than with barbiturates.9 Coma blisters rarely have been documented in the setting of isolated benzodiazepine overdose, and of the few cases, only one report implicated lorazepam as the causative agent.4,7 The characteristic finding of eccrine gland necrosis consistently was seen in our patient. This case not only emphasizes the need for greater awareness of the association between benzodiazepine overdose and coma blisters but also the importance of clinical context when considering diagnoses. It is essential to note that coma blisters themselves are nonspecific, and the diagnosis of drug-induced coma blisters warrants confirmatory toxicologic analysis.

The Diagnosis: Coma Blisters

Histologic examination revealed pauci-inflammatory subepidermal blisters with swelling of eccrine cells, signaling impending gland necrosis (Figure). Direct immunofluorescence testing on perilesional skin was negative. These findings would be inconsistent for diagnoses of edema blisters (most commonly seen in patients with an acute exacerbation of chronic lower extremity edema), friction blisters (intraepidermal blisters seen on histopathology), and bullous pemphigoid (linear IgG and/or C3 staining along the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence testing is characteristic). Although eccrine gland alterations have been seen in toxic epidermal necrolysis,1 the mucous membranes are involved in more than 90% of cases, making the diagnosis less likely. Furthermore, interface changes including prominent keratinocyte necrosis were not seen on histology.

Given the localized nature of the lesions in our patient and negative direct immunofluorescence studies, a diagnosis of coma blisters was made. Gentle wound care practices to the areas of denuded skin were implemented with complete resolution. The patient’s condition gradually improved, and she was extubated and discharged home.

Coma blisters are self-limited bullous lesions that have been reported in comatose patients as early as 1812 when Napoleon’s surgeon first noticed cutaneous blisters in comatose French soldiers being treated for carbon monoxide intoxication.2 Since then, barbiturate overdose has remained the most common association, but coma blisters have occurred in the absence of specific drug exposures. Clinically, erythematous or violaceous plaques typically appear within 24 hours of drug ingestion, and progression to large tense bullae usually occurs within 48 to 72 hours of unconsciousness.3 They characteristically occur in pressure-dependent areas, but reports have shown lesions in non–pressure-dependent areas, including the penis and mouth.1,4 Spontaneous resolution within 1 to 2 weeks is typical.5

The underlying pathogenesis remains controversial, as multiple mechanisms have been suggested, but clear causal evidence is lacking. The original proposition that direct effects of drug toxicity caused the cutaneous observations was later refuted after similar bullous lesions with eccrine gland necrosis were reported in comatose patients with neurologic conditions.6 It is largely accepted that pressure-induced local ischemia—proportional to the duration and amount of pressure—leads to tissue injury and is critical to the pathogenesis. During periods of ischemia, the most metabolically active tissues will undergo necrosis first; however, in eccrine glands, the earliest and most severe damage does not seem to occur in the most metabolically active cells.7 Additionally, this would not provide a viable explanation for coma blisters with eccrine gland necrosis developing in variable non–pressuredependent areas.

Moreover, drug- and non–drug-induced coma blisters can appear identically, but specific histopathologic differences have been reported. The most notable markers of non–drug-induced coma blisters are the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate in the epidermis and the presence of thrombosis in dermal vessels.8 Demonstration of necrotic changes in the secretory portion of the eccrine gland is considered the histopathologic hallmark for drug-induced coma blisters, but other findings can include subepidermal or intraepidermal bullae; perivascular infiltrates; and focal necrosis of the epidermis, dermis, subcutis, or epidermal appendages.6 Arteriolar wall necrosis and dermal inflammatory infiltrates also have been observed.7

Benzodiazepines have been widely prescribed and abused since their development, and overdose is much more common today than with barbiturates.9 Coma blisters rarely have been documented in the setting of isolated benzodiazepine overdose, and of the few cases, only one report implicated lorazepam as the causative agent.4,7 The characteristic finding of eccrine gland necrosis consistently was seen in our patient. This case not only emphasizes the need for greater awareness of the association between benzodiazepine overdose and coma blisters but also the importance of clinical context when considering diagnoses. It is essential to note that coma blisters themselves are nonspecific, and the diagnosis of drug-induced coma blisters warrants confirmatory toxicologic analysis.

- Ferreli C, Sulica VI, Aste N, et al. Drug-induced sweat gland necrosis in a non-comatose patient: a case presentation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:443-445.

- Larrey DJ. Memoires de Chirurgie Militaire et Campagnes. Smith and Buisson; 1812.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Varma AJ, Fisher BK, Sarin MK. Diazepam-induced coma with bullae and eccrine sweat gland necrosis. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:1207-1210.

- Rocha J, Pereira T, Ventura F, et al. Coma blisters. Case Rep Dermatol. 2009;1:66-70.

- Arndt KA, Mihm MC, Parrish JA. Bullae: a cutaneous sign of a variety of neurologic diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1973;60:312-320.

- Sánchez Yus E, Requena L, Simón P. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:208-216.

- Kato N, Ueno H, Mimura M. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in non-drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:344-350.

- Kang M, Ghassemzadeh S. Benzodiazepine Toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

- Ferreli C, Sulica VI, Aste N, et al. Drug-induced sweat gland necrosis in a non-comatose patient: a case presentation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003;17:443-445.

- Larrey DJ. Memoires de Chirurgie Militaire et Campagnes. Smith and Buisson; 1812.

- Agarwal A, Bansal M, Conner K. Coma blisters with hypoxemic respiratory failure. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Varma AJ, Fisher BK, Sarin MK. Diazepam-induced coma with bullae and eccrine sweat gland necrosis. Arch Intern Med. 1977;137:1207-1210.

- Rocha J, Pereira T, Ventura F, et al. Coma blisters. Case Rep Dermatol. 2009;1:66-70.

- Arndt KA, Mihm MC, Parrish JA. Bullae: a cutaneous sign of a variety of neurologic diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1973;60:312-320.

- Sánchez Yus E, Requena L, Simón P. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:208-216.

- Kato N, Ueno H, Mimura M. Histopathology of cutaneous changes in non-drug-induced coma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:344-350.

- Kang M, Ghassemzadeh S. Benzodiazepine Toxicity. StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

An 82-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after her daughter found her unconscious in the bathroom laying on her right side. Her medical history was notable for hypertension and asthma for which she was on losartan, furosemide, diltiazem, and albuterol. She recently had been prescribed lorazepam for insomnia and had started taking the medication 2 days prior. She underwent intubation and was noted to have flaccid, fluid-filled bullae on the right thigh (top) along with large areas of desquamation on the right lateral arm (bottom) with minimal surrounding erythema. There was no mucous membrane involvement. Urine toxicology was positive for benzodiazepines and negative for all other drugs, including barbiturates.