User login

How to perform a vulvar biopsy

Many benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions can occur on the vulva. These can be challenging to differentiate by examination alone. A vulvar biopsy often is needed to appropriately diagnose—and ultimately treat—these various conditions.

In this article, we review vulvar biopsy procedures, describe how to prepare tissue specimens for the pathologist, and provide some brief case examples in which biopsy established the diagnosis.

Ask questions first

Prior to examining a patient with a vulvar lesion, obtain a detailed history. Asking specific questions may aid in making the correct diagnosis, such as:

- How long has the lesion been present? Has it changed? What color is it?

- Was any trigger, or trauma, associated with onset of the lesion?

- Does the lesion itch, burn, or cause pain? Is there any associated bleeding or discharge?

- Are other lesions present in the vagina, anus, or mouth, or are other skin lesions present?

- Are any systemic symptoms present, such as fever, lymphadenopathy, weight loss, or joint pain?

- What is the patient’s previous treatment history, including over-the-counter medications and prescribed medications?

- Has there been any incontinence of urine or stool? Does the patient use a pad?

- Is the patient scratching? Is there any nighttime scratching? It also can be useful to ask her partner, if she has one, about nighttime scratching.

- Is there a family history of vulvar conditions?

- Has there been any change in her use of products like soap, lotions, cleansing wipes, sprays, lubricants, or laundry detergent?

- Has the patient had any new partners or significant travel history?

Preprocedure counseling points

Prior to proceeding with a vulvar biopsy, review with the patient the risks, benefits, and alternatives and obtain patient consent for the procedure. Vulvar biopsy risks include pain, bleeding, infection, injury to surrounding tissue, and the need for further surgery. Make patients aware that some biopsies are nondiagnostic. We recommend that clinicians perform a time-out verification to ensure that the patient’s identity and planned procedure are correct.

Assess the biopsy site

A wide variety of lesions may require a biopsy for diagnosis. While it can be challenging to know where to biopsy, taking the time to determine the proper biopsy site may enhance pathology results.

When considering colored lesions, depth is the important factor, and a punch biopsy often is sufficient. A tumor should be biopsied in the thickest area. Lesions that are concerning for malignancy may require multiple biopsies. An erosion or ulcer is best biopsied on the edge, including a small amount of surrounding tissue. For most patients, biopsy of normal-appearing tissue is of low diagnostic yield. Lastly, we try to avoid biopsies directly on the midline to facilitate better healing.1

A photograph of the vulva prior to biopsy may be helpful for the pathologist to see the tissue. Some electronic medical records have the capability to include photographs. Due to the sensitive nature of these photographs, we prefer that a separate written patient consent be obtained prior to taking photographs. We find also that photos are a useful reference for progression of disease at follow-up in a shared care team.

Continue to: Anesthesia procedure and instrument kit...

Anesthesia procedure and instrument kit

Some patients may benefit from the application of topical lidocaine 4% cream (L.M.X.4) prior to the injection of a local anesthetic for tissue biopsy. Ideally, topical lidocaine should be placed on the vulva and covered with a dressing such as Tegaderm or cellophane up to 30 minutes before the anticipated biopsy procedure. The anesthetic effect generally lasts for about 60 minutes. Many patients report stinging for several seconds upon application. Due to clinic time restrictions, we tend to reserve this method for a limited subset of patients. If planning a return visit for a biopsy, the patient can place the topical anesthetic herself.

For the anesthetic injection, we recommend lidocaine 1% or 2% with epinephrine in all areas of the vulva except for the glans clitoris. For a punch biopsy, we draw up 1 to 3 mL in a 3-mL syringe and inject with a 21- to 30-gauge needle, using a lower gauge for thicker tissue. We have not found buffering the anesthetic with sodium bicarbonate to be of particular use. For the glans clitoris, lidocaine without epinephrine should be utilized.

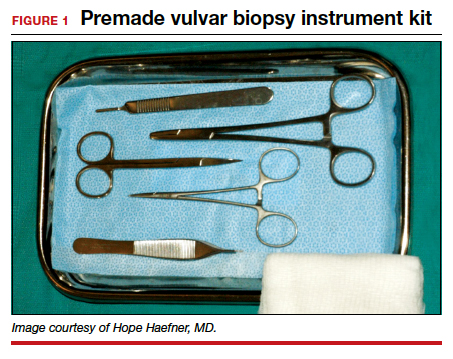

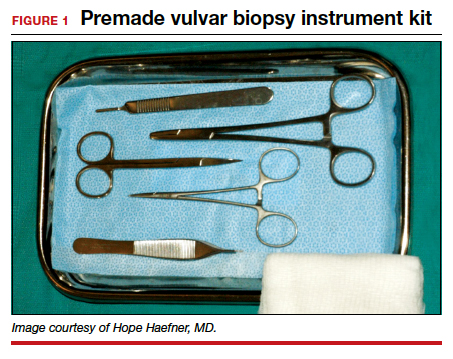

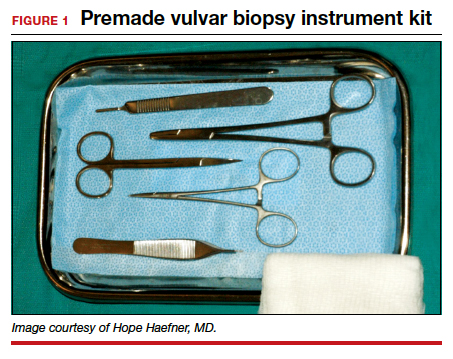

Equipment. Depending on your office setting, having a premade instrument kit may be preferred to peel-pack equipment. We prefer a premade tray that contains sterile gauze, a hemostat, iris scissors, a needle driver, a scalpel handle, and Adson forceps (FIGURE 1).

Types of biopsy procedures

Punch biopsy. We recommend a 4-mm Keyes biopsy punch. As mentioned, we use a biopsy kit to facilitate the procedure. After the tissue is properly anesthetized and prepped, we test the area via gentle touch to the skin with the hemostat or Adson forceps. To perform the punch biopsy, gentle, consistent pressure in a clockwise-counterclockwise fashion yields the best results. The goal is to obtain a 5-mm depth for hair-bearing skin and a 3-mm depth for all other tissue.2 The tissue should then be excised at the base with scissors, taking care not to crush the specimen with forceps.

Punch biopsy permits sampling of the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. Hemostasis is maintained with either silver nitrate, Monsel’s solution (ferric sulfate), or a dissolvable suture such as 4-0 Monocryl (poliglecaprone 25) or Vicryl Rapide (polyglactin 910).

Stitch biopsy. We find the stitch biopsy to be very useful given the architecture of the vulva. A modification of the shave biopsy, the stitch biopsy is depicted in FIGURE 2. A 3-0 or 4-0 dissolvable suture is placed through the intended area of biopsy. Iris scissors are used to undermine the tissue while the suture is held on tension. The goal is to remove the suture with the specimen. Separate sutures are used for hemostasis. The stitch does not cause the crushing artifacts on prepared specimens. Depending on the proceduralist’s comfort, a relatively large sample can be obtained in this fashion. If the suture held on tension is inadvertently cut, a second pass can be made with suture; alternatively, care can be used to remove remaining tissue with forceps and scissors, again avoiding crush injury to the tissue.

Excisional biopsy. Often, a larger area or margins are desired. We find that with adequate preparation, patients tolerate excisions in the office quite well. The planned area for excision can be marked with ink to ensure margins. Adequate anesthesia is instilled. A No. 15 blade scalpel is often the best size used to excise vulvar tissue in an elliptical fashion. Depending on depth of incision, the tissue may need to be approximated in layers for cosmesis and healing.

When planning an excisional biopsy, place a stitch on the excised tissue to mark orientation or pin out the entire specimen to a foam board to help your pathologist interpret tissue orientation.

The box "Vulvar biopsy established the diagnosis" at the end of this discussion provides 6 case examples of vulvar lesions and the respective diagnoses confirmed by biopsy.

Continue to: Preparing tissue for the pathologist...

Preparing tissue for the pathologist

Here are 5 tips for preparing the biopsied specimen for pathology:

- Include a question for the pathologist, such as “rule out lichen sclerosus or lichen simplex chronicus.” The majority of specimens should be sent in formalin. At times, frozen sections are done in the operating room.

- Double-check that the proper paperwork is included with every specimen and be very specific regarding the exact location of the lesion on the vulva. Include photographs whenever possible.

- Request that a dermatopathologist or a gynecologic pathologist with a special interest in vulvar dermatology, when feasible, review the tissue.

- Check your laboratory’s protocol for sending biopsies from areas around ulcerated tissue. Often, special medium is required for immunohistochemistry stains.

- Call your pathologist with questions about results; he or she often is happy to clarify, and together you may be able to arrive at a diagnosis to better serve your patient.3

Complications and how to avoid them

Bleeding. Any procedure has bleeding risks. To avoid bleeding, review the patient’s medication list and medical history prior to biopsy, as certain medications, such as blood thinners, increase risk for bleeding. Counseling a patient on applying direct pressure to the biopsy site for 2 minutes is generally sufficient for any bleeding that may occur once she is discharged from the clinic.

Infection. With aseptic technique, infection of a biopsy site is rare. We use nonsterile gloves for biopsy procedures. This does not increase the risk of infection.4 If a patient has iodine allergy, dilute chlorhexidine is a reasonable alternative for skin cleansing. Instruct the patient to keep the site clean and dry; if the biopsy proximity is close to the urethra or anus, use of a peri-bottle may be preferred after toileting. Instruct patients not to pull sutures. While instructions are specific for each patient, we generally advise that patients wait 4 to 7 days before resuming use of topical medications.

Scarring or tattooing. Avoid using dyed suture on skin surfaces and counsel the patient that silver nitrate can permanently stain tissue. Usually, small biopsies heal well but a small scar is possible.

Key points to keep in mind

- Counsel patients on biopsy risks, benefits, and alternatives. Counsel regarding possible inconclusive results.

- Take time in choosing the biopsy site and consider multiple biopsies.

- Have all anticipated equipment available; consider using premade biopsy kits.

- Consider performing a stitch biopsy to avoid crush injury.

- Take photographs of the area to be biopsied and communicate with your pathologist to facilitate diagnosis.

Case 1

Biopsies were obtained of the areas highlighted in the photo. Pathology shows dVIN.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 2

The examination is consistent with condylomata acuminata and biopsy is recommended with a 4-mm punch. Biopsy results are consistent with condylomata acuminata.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 3

The final pathology shows high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) of the vulva.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 4

This presentation is an excellent opportunity for an excisional biopsy of the vulva. A marking pen is used to draw margins. A No. 15 blade is used to outline and then undermine the lesion, removing it in its entirety.

Final pathology shows a compound nevus of the vulva.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 5

A 4-mm punch biopsy result is consistent with a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 6

A 4-mm punch biopsy result reveals that the pathology is significant for squamous cell carcinoma.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

- Edwards L, Lynch PJ. Genital Dermatology Atlas and Manual. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 93: Diagnosis and management of vulvar skin disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1243-1253.

- Heller DS. Areas of confusion in pathologist-clinician communication as it relates to understanding the vulvar pathology report. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2017;21:327-328.

- Rietz A, Barzin A, Jones K, et al. Sterile or non-sterile gloves for minor skin excisions? J Fam Pract. 2015;64:723-727.

Many benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions can occur on the vulva. These can be challenging to differentiate by examination alone. A vulvar biopsy often is needed to appropriately diagnose—and ultimately treat—these various conditions.

In this article, we review vulvar biopsy procedures, describe how to prepare tissue specimens for the pathologist, and provide some brief case examples in which biopsy established the diagnosis.

Ask questions first

Prior to examining a patient with a vulvar lesion, obtain a detailed history. Asking specific questions may aid in making the correct diagnosis, such as:

- How long has the lesion been present? Has it changed? What color is it?

- Was any trigger, or trauma, associated with onset of the lesion?

- Does the lesion itch, burn, or cause pain? Is there any associated bleeding or discharge?

- Are other lesions present in the vagina, anus, or mouth, or are other skin lesions present?

- Are any systemic symptoms present, such as fever, lymphadenopathy, weight loss, or joint pain?

- What is the patient’s previous treatment history, including over-the-counter medications and prescribed medications?

- Has there been any incontinence of urine or stool? Does the patient use a pad?

- Is the patient scratching? Is there any nighttime scratching? It also can be useful to ask her partner, if she has one, about nighttime scratching.

- Is there a family history of vulvar conditions?

- Has there been any change in her use of products like soap, lotions, cleansing wipes, sprays, lubricants, or laundry detergent?

- Has the patient had any new partners or significant travel history?

Preprocedure counseling points

Prior to proceeding with a vulvar biopsy, review with the patient the risks, benefits, and alternatives and obtain patient consent for the procedure. Vulvar biopsy risks include pain, bleeding, infection, injury to surrounding tissue, and the need for further surgery. Make patients aware that some biopsies are nondiagnostic. We recommend that clinicians perform a time-out verification to ensure that the patient’s identity and planned procedure are correct.

Assess the biopsy site

A wide variety of lesions may require a biopsy for diagnosis. While it can be challenging to know where to biopsy, taking the time to determine the proper biopsy site may enhance pathology results.

When considering colored lesions, depth is the important factor, and a punch biopsy often is sufficient. A tumor should be biopsied in the thickest area. Lesions that are concerning for malignancy may require multiple biopsies. An erosion or ulcer is best biopsied on the edge, including a small amount of surrounding tissue. For most patients, biopsy of normal-appearing tissue is of low diagnostic yield. Lastly, we try to avoid biopsies directly on the midline to facilitate better healing.1

A photograph of the vulva prior to biopsy may be helpful for the pathologist to see the tissue. Some electronic medical records have the capability to include photographs. Due to the sensitive nature of these photographs, we prefer that a separate written patient consent be obtained prior to taking photographs. We find also that photos are a useful reference for progression of disease at follow-up in a shared care team.

Continue to: Anesthesia procedure and instrument kit...

Anesthesia procedure and instrument kit

Some patients may benefit from the application of topical lidocaine 4% cream (L.M.X.4) prior to the injection of a local anesthetic for tissue biopsy. Ideally, topical lidocaine should be placed on the vulva and covered with a dressing such as Tegaderm or cellophane up to 30 minutes before the anticipated biopsy procedure. The anesthetic effect generally lasts for about 60 minutes. Many patients report stinging for several seconds upon application. Due to clinic time restrictions, we tend to reserve this method for a limited subset of patients. If planning a return visit for a biopsy, the patient can place the topical anesthetic herself.

For the anesthetic injection, we recommend lidocaine 1% or 2% with epinephrine in all areas of the vulva except for the glans clitoris. For a punch biopsy, we draw up 1 to 3 mL in a 3-mL syringe and inject with a 21- to 30-gauge needle, using a lower gauge for thicker tissue. We have not found buffering the anesthetic with sodium bicarbonate to be of particular use. For the glans clitoris, lidocaine without epinephrine should be utilized.

Equipment. Depending on your office setting, having a premade instrument kit may be preferred to peel-pack equipment. We prefer a premade tray that contains sterile gauze, a hemostat, iris scissors, a needle driver, a scalpel handle, and Adson forceps (FIGURE 1).

Types of biopsy procedures

Punch biopsy. We recommend a 4-mm Keyes biopsy punch. As mentioned, we use a biopsy kit to facilitate the procedure. After the tissue is properly anesthetized and prepped, we test the area via gentle touch to the skin with the hemostat or Adson forceps. To perform the punch biopsy, gentle, consistent pressure in a clockwise-counterclockwise fashion yields the best results. The goal is to obtain a 5-mm depth for hair-bearing skin and a 3-mm depth for all other tissue.2 The tissue should then be excised at the base with scissors, taking care not to crush the specimen with forceps.

Punch biopsy permits sampling of the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. Hemostasis is maintained with either silver nitrate, Monsel’s solution (ferric sulfate), or a dissolvable suture such as 4-0 Monocryl (poliglecaprone 25) or Vicryl Rapide (polyglactin 910).

Stitch biopsy. We find the stitch biopsy to be very useful given the architecture of the vulva. A modification of the shave biopsy, the stitch biopsy is depicted in FIGURE 2. A 3-0 or 4-0 dissolvable suture is placed through the intended area of biopsy. Iris scissors are used to undermine the tissue while the suture is held on tension. The goal is to remove the suture with the specimen. Separate sutures are used for hemostasis. The stitch does not cause the crushing artifacts on prepared specimens. Depending on the proceduralist’s comfort, a relatively large sample can be obtained in this fashion. If the suture held on tension is inadvertently cut, a second pass can be made with suture; alternatively, care can be used to remove remaining tissue with forceps and scissors, again avoiding crush injury to the tissue.

Excisional biopsy. Often, a larger area or margins are desired. We find that with adequate preparation, patients tolerate excisions in the office quite well. The planned area for excision can be marked with ink to ensure margins. Adequate anesthesia is instilled. A No. 15 blade scalpel is often the best size used to excise vulvar tissue in an elliptical fashion. Depending on depth of incision, the tissue may need to be approximated in layers for cosmesis and healing.

When planning an excisional biopsy, place a stitch on the excised tissue to mark orientation or pin out the entire specimen to a foam board to help your pathologist interpret tissue orientation.

The box "Vulvar biopsy established the diagnosis" at the end of this discussion provides 6 case examples of vulvar lesions and the respective diagnoses confirmed by biopsy.

Continue to: Preparing tissue for the pathologist...

Preparing tissue for the pathologist

Here are 5 tips for preparing the biopsied specimen for pathology:

- Include a question for the pathologist, such as “rule out lichen sclerosus or lichen simplex chronicus.” The majority of specimens should be sent in formalin. At times, frozen sections are done in the operating room.

- Double-check that the proper paperwork is included with every specimen and be very specific regarding the exact location of the lesion on the vulva. Include photographs whenever possible.

- Request that a dermatopathologist or a gynecologic pathologist with a special interest in vulvar dermatology, when feasible, review the tissue.

- Check your laboratory’s protocol for sending biopsies from areas around ulcerated tissue. Often, special medium is required for immunohistochemistry stains.

- Call your pathologist with questions about results; he or she often is happy to clarify, and together you may be able to arrive at a diagnosis to better serve your patient.3

Complications and how to avoid them

Bleeding. Any procedure has bleeding risks. To avoid bleeding, review the patient’s medication list and medical history prior to biopsy, as certain medications, such as blood thinners, increase risk for bleeding. Counseling a patient on applying direct pressure to the biopsy site for 2 minutes is generally sufficient for any bleeding that may occur once she is discharged from the clinic.

Infection. With aseptic technique, infection of a biopsy site is rare. We use nonsterile gloves for biopsy procedures. This does not increase the risk of infection.4 If a patient has iodine allergy, dilute chlorhexidine is a reasonable alternative for skin cleansing. Instruct the patient to keep the site clean and dry; if the biopsy proximity is close to the urethra or anus, use of a peri-bottle may be preferred after toileting. Instruct patients not to pull sutures. While instructions are specific for each patient, we generally advise that patients wait 4 to 7 days before resuming use of topical medications.

Scarring or tattooing. Avoid using dyed suture on skin surfaces and counsel the patient that silver nitrate can permanently stain tissue. Usually, small biopsies heal well but a small scar is possible.

Key points to keep in mind

- Counsel patients on biopsy risks, benefits, and alternatives. Counsel regarding possible inconclusive results.

- Take time in choosing the biopsy site and consider multiple biopsies.

- Have all anticipated equipment available; consider using premade biopsy kits.

- Consider performing a stitch biopsy to avoid crush injury.

- Take photographs of the area to be biopsied and communicate with your pathologist to facilitate diagnosis.

Case 1

Biopsies were obtained of the areas highlighted in the photo. Pathology shows dVIN.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 2

The examination is consistent with condylomata acuminata and biopsy is recommended with a 4-mm punch. Biopsy results are consistent with condylomata acuminata.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 3

The final pathology shows high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) of the vulva.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 4

This presentation is an excellent opportunity for an excisional biopsy of the vulva. A marking pen is used to draw margins. A No. 15 blade is used to outline and then undermine the lesion, removing it in its entirety.

Final pathology shows a compound nevus of the vulva.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 5

A 4-mm punch biopsy result is consistent with a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 6

A 4-mm punch biopsy result reveals that the pathology is significant for squamous cell carcinoma.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Many benign, premalignant, and malignant lesions can occur on the vulva. These can be challenging to differentiate by examination alone. A vulvar biopsy often is needed to appropriately diagnose—and ultimately treat—these various conditions.

In this article, we review vulvar biopsy procedures, describe how to prepare tissue specimens for the pathologist, and provide some brief case examples in which biopsy established the diagnosis.

Ask questions first

Prior to examining a patient with a vulvar lesion, obtain a detailed history. Asking specific questions may aid in making the correct diagnosis, such as:

- How long has the lesion been present? Has it changed? What color is it?

- Was any trigger, or trauma, associated with onset of the lesion?

- Does the lesion itch, burn, or cause pain? Is there any associated bleeding or discharge?

- Are other lesions present in the vagina, anus, or mouth, or are other skin lesions present?

- Are any systemic symptoms present, such as fever, lymphadenopathy, weight loss, or joint pain?

- What is the patient’s previous treatment history, including over-the-counter medications and prescribed medications?

- Has there been any incontinence of urine or stool? Does the patient use a pad?

- Is the patient scratching? Is there any nighttime scratching? It also can be useful to ask her partner, if she has one, about nighttime scratching.

- Is there a family history of vulvar conditions?

- Has there been any change in her use of products like soap, lotions, cleansing wipes, sprays, lubricants, or laundry detergent?

- Has the patient had any new partners or significant travel history?

Preprocedure counseling points

Prior to proceeding with a vulvar biopsy, review with the patient the risks, benefits, and alternatives and obtain patient consent for the procedure. Vulvar biopsy risks include pain, bleeding, infection, injury to surrounding tissue, and the need for further surgery. Make patients aware that some biopsies are nondiagnostic. We recommend that clinicians perform a time-out verification to ensure that the patient’s identity and planned procedure are correct.

Assess the biopsy site

A wide variety of lesions may require a biopsy for diagnosis. While it can be challenging to know where to biopsy, taking the time to determine the proper biopsy site may enhance pathology results.

When considering colored lesions, depth is the important factor, and a punch biopsy often is sufficient. A tumor should be biopsied in the thickest area. Lesions that are concerning for malignancy may require multiple biopsies. An erosion or ulcer is best biopsied on the edge, including a small amount of surrounding tissue. For most patients, biopsy of normal-appearing tissue is of low diagnostic yield. Lastly, we try to avoid biopsies directly on the midline to facilitate better healing.1

A photograph of the vulva prior to biopsy may be helpful for the pathologist to see the tissue. Some electronic medical records have the capability to include photographs. Due to the sensitive nature of these photographs, we prefer that a separate written patient consent be obtained prior to taking photographs. We find also that photos are a useful reference for progression of disease at follow-up in a shared care team.

Continue to: Anesthesia procedure and instrument kit...

Anesthesia procedure and instrument kit

Some patients may benefit from the application of topical lidocaine 4% cream (L.M.X.4) prior to the injection of a local anesthetic for tissue biopsy. Ideally, topical lidocaine should be placed on the vulva and covered with a dressing such as Tegaderm or cellophane up to 30 minutes before the anticipated biopsy procedure. The anesthetic effect generally lasts for about 60 minutes. Many patients report stinging for several seconds upon application. Due to clinic time restrictions, we tend to reserve this method for a limited subset of patients. If planning a return visit for a biopsy, the patient can place the topical anesthetic herself.

For the anesthetic injection, we recommend lidocaine 1% or 2% with epinephrine in all areas of the vulva except for the glans clitoris. For a punch biopsy, we draw up 1 to 3 mL in a 3-mL syringe and inject with a 21- to 30-gauge needle, using a lower gauge for thicker tissue. We have not found buffering the anesthetic with sodium bicarbonate to be of particular use. For the glans clitoris, lidocaine without epinephrine should be utilized.

Equipment. Depending on your office setting, having a premade instrument kit may be preferred to peel-pack equipment. We prefer a premade tray that contains sterile gauze, a hemostat, iris scissors, a needle driver, a scalpel handle, and Adson forceps (FIGURE 1).

Types of biopsy procedures

Punch biopsy. We recommend a 4-mm Keyes biopsy punch. As mentioned, we use a biopsy kit to facilitate the procedure. After the tissue is properly anesthetized and prepped, we test the area via gentle touch to the skin with the hemostat or Adson forceps. To perform the punch biopsy, gentle, consistent pressure in a clockwise-counterclockwise fashion yields the best results. The goal is to obtain a 5-mm depth for hair-bearing skin and a 3-mm depth for all other tissue.2 The tissue should then be excised at the base with scissors, taking care not to crush the specimen with forceps.

Punch biopsy permits sampling of the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. Hemostasis is maintained with either silver nitrate, Monsel’s solution (ferric sulfate), or a dissolvable suture such as 4-0 Monocryl (poliglecaprone 25) or Vicryl Rapide (polyglactin 910).

Stitch biopsy. We find the stitch biopsy to be very useful given the architecture of the vulva. A modification of the shave biopsy, the stitch biopsy is depicted in FIGURE 2. A 3-0 or 4-0 dissolvable suture is placed through the intended area of biopsy. Iris scissors are used to undermine the tissue while the suture is held on tension. The goal is to remove the suture with the specimen. Separate sutures are used for hemostasis. The stitch does not cause the crushing artifacts on prepared specimens. Depending on the proceduralist’s comfort, a relatively large sample can be obtained in this fashion. If the suture held on tension is inadvertently cut, a second pass can be made with suture; alternatively, care can be used to remove remaining tissue with forceps and scissors, again avoiding crush injury to the tissue.

Excisional biopsy. Often, a larger area or margins are desired. We find that with adequate preparation, patients tolerate excisions in the office quite well. The planned area for excision can be marked with ink to ensure margins. Adequate anesthesia is instilled. A No. 15 blade scalpel is often the best size used to excise vulvar tissue in an elliptical fashion. Depending on depth of incision, the tissue may need to be approximated in layers for cosmesis and healing.

When planning an excisional biopsy, place a stitch on the excised tissue to mark orientation or pin out the entire specimen to a foam board to help your pathologist interpret tissue orientation.

The box "Vulvar biopsy established the diagnosis" at the end of this discussion provides 6 case examples of vulvar lesions and the respective diagnoses confirmed by biopsy.

Continue to: Preparing tissue for the pathologist...

Preparing tissue for the pathologist

Here are 5 tips for preparing the biopsied specimen for pathology:

- Include a question for the pathologist, such as “rule out lichen sclerosus or lichen simplex chronicus.” The majority of specimens should be sent in formalin. At times, frozen sections are done in the operating room.

- Double-check that the proper paperwork is included with every specimen and be very specific regarding the exact location of the lesion on the vulva. Include photographs whenever possible.

- Request that a dermatopathologist or a gynecologic pathologist with a special interest in vulvar dermatology, when feasible, review the tissue.

- Check your laboratory’s protocol for sending biopsies from areas around ulcerated tissue. Often, special medium is required for immunohistochemistry stains.

- Call your pathologist with questions about results; he or she often is happy to clarify, and together you may be able to arrive at a diagnosis to better serve your patient.3

Complications and how to avoid them

Bleeding. Any procedure has bleeding risks. To avoid bleeding, review the patient’s medication list and medical history prior to biopsy, as certain medications, such as blood thinners, increase risk for bleeding. Counseling a patient on applying direct pressure to the biopsy site for 2 minutes is generally sufficient for any bleeding that may occur once she is discharged from the clinic.

Infection. With aseptic technique, infection of a biopsy site is rare. We use nonsterile gloves for biopsy procedures. This does not increase the risk of infection.4 If a patient has iodine allergy, dilute chlorhexidine is a reasonable alternative for skin cleansing. Instruct the patient to keep the site clean and dry; if the biopsy proximity is close to the urethra or anus, use of a peri-bottle may be preferred after toileting. Instruct patients not to pull sutures. While instructions are specific for each patient, we generally advise that patients wait 4 to 7 days before resuming use of topical medications.

Scarring or tattooing. Avoid using dyed suture on skin surfaces and counsel the patient that silver nitrate can permanently stain tissue. Usually, small biopsies heal well but a small scar is possible.

Key points to keep in mind

- Counsel patients on biopsy risks, benefits, and alternatives. Counsel regarding possible inconclusive results.

- Take time in choosing the biopsy site and consider multiple biopsies.

- Have all anticipated equipment available; consider using premade biopsy kits.

- Consider performing a stitch biopsy to avoid crush injury.

- Take photographs of the area to be biopsied and communicate with your pathologist to facilitate diagnosis.

Case 1

Biopsies were obtained of the areas highlighted in the photo. Pathology shows dVIN.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 2

The examination is consistent with condylomata acuminata and biopsy is recommended with a 4-mm punch. Biopsy results are consistent with condylomata acuminata.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 3

The final pathology shows high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) of the vulva.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 4

This presentation is an excellent opportunity for an excisional biopsy of the vulva. A marking pen is used to draw margins. A No. 15 blade is used to outline and then undermine the lesion, removing it in its entirety.

Final pathology shows a compound nevus of the vulva.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 5

A 4-mm punch biopsy result is consistent with a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

Case 6

A 4-mm punch biopsy result reveals that the pathology is significant for squamous cell carcinoma.

Image courtesy of Hope Haefner, MD.

- Edwards L, Lynch PJ. Genital Dermatology Atlas and Manual. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 93: Diagnosis and management of vulvar skin disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1243-1253.

- Heller DS. Areas of confusion in pathologist-clinician communication as it relates to understanding the vulvar pathology report. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2017;21:327-328.

- Rietz A, Barzin A, Jones K, et al. Sterile or non-sterile gloves for minor skin excisions? J Fam Pract. 2015;64:723-727.

- Edwards L, Lynch PJ. Genital Dermatology Atlas and Manual. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 93: Diagnosis and management of vulvar skin disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1243-1253.

- Heller DS. Areas of confusion in pathologist-clinician communication as it relates to understanding the vulvar pathology report. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2017;21:327-328.

- Rietz A, Barzin A, Jones K, et al. Sterile or non-sterile gloves for minor skin excisions? J Fam Pract. 2015;64:723-727.