User login

An Automated Electronic Tool to Assess the Risk of 30-Day Readmission: Validation of Predictive Performance

From the Divisions of Hospital Medicine (Drs. Dawson, Chirila, Bhide, and Burton) and Biomedical Statistics and Informatics (Ms. Thomas), Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, and the Division of Hospital Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, AZ (Dr. Cannon).

Abstract

- Objective: To validate an electronic tool created to identify inpatients who are at risk of readmission within 30 days and quantify the predictive performance of the readmission risk score (RRS).

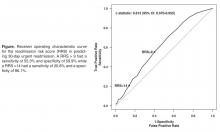

- Methods: Retrospective cohort study including inpa-tients who were discharged between 1 Nov 2012 and 31 Dec 2012. The ability of the RRS to discriminate between those who did and did not have a 30-day urgent readmission was quantified by the c statistic. Calibration was assessed by plotting the observed and predicted probability of 30-day urgent readmission. Predicted probabilities were obtained from generalized estimating equations, clustering on patient.

- Results: Of 1689 hospital inpatient discharges (1515 patients), 159 (9.4%) had a 30-day urgent readmission. The RRS had some discriminative ability (c statistic: 0.612; 95% confidence interval: 0.570–0.655) and good calibration.

- Conclusions: Our study shows that the RRS has some discriminative ability. The automated tool can be used to estimate the probability of a 30-day urgent readmission.

Hospital readmissions are increasingly scrutinized by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers due to their frequency and high cost. It is estimated that up to 25% of all patients discharged from acute care hospitals are readmitted within 30 days [1]. To address this problem, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services is using these rates as one of the benchmarks for quality for hospitals and health care organizations and has begun to assess penalties to those institutions with the highest rates. This scrutiny and the desire for better patient care transitions has resulted in most hospitals implementing various initiatives to reduce potentially avoidable readmissions.

Multiple interventions have been shown to reduce readmissions [2,3]. These interventions have varying effectiveness and are often labor intensive and thus costly to the institutions implementing them. In fact, no one intervention has been shown to be effective alone [4], and it may take several concurrent interventions targeting the highest risk patients to improve transitions of care at discharge that result in reduced readmissions. Many experts do recommend risk stratifying patients in order to target interventions to the highest risk patients for effective use of resources [5,6]. Several risk factor assessments have been proposed with varying success [7–13]. Multiple factors can limit the effectiveness of these risk stratification profiles. They may have low sensitivity and specificity, be based solely on retrospective data, be limited to certain populations, or be created from administrative data only without taking psychosocial factors into consideration [14].

An effective risk assessment ideally would encompass multiple known risk factors including certain comorbidities such as malignancy and heart failure, psychosocial factors such as health literacy and social support, and administrative data including payment source and demographics. All of these have been shown in prior studies to contribute to readmissions [7–13]. In addition, availability of the assessment early in the hospitalization would allow for interventions throughout the hospital stay to mitigate the effect of these factors where possible. To address these needs, our institution formed a readmission task force in January 2010 to review published literature on hospital 30-day readmissions and create a readmission risk score (RRS). The aim of this study was to quantify the predictive performance of the RRS after it was first implemented into the electronic medical record (EMR) in November 2012.

Methods

Study Design and Cohort

All consecutive adult inpatients who were discharged between 1 November 2012 and 31 December 2012 were included in this retrospective cohort study. This narrow time frame corresponded to the period from RRS tool implementation to the start of readmission interventions. We excluded hospitalizations if the patient died in the hospital.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was a 30-day urgent readmission, which included readmissions categorized as either emergency, urgent, or semi-urgent. Secondary outcomes included any 30-day readmission and 30-day death. Only readmissions to Mayo Clinic were examined.

Predictors

In collaboration with the information technology department, an algorithm was written to extract data from the EMR for each patient within 24 hours of admission to the hospital. This data was retrieved from existing repositories of patient information, such as demographic information, payer source, medication list, problem list, and past medical history. In addition, each patient was interviewed by a nurse at the time of admission, and the nurse completed an “admission profile” in the EMR that confirmed or entered past medical history, medications, social support at home, depression symptoms, and learning styles, among other information (Table 1). The algorithm was able to extract data from this evaluation also, so that each element of the risk score was correlated to at least one data source in the EMR. The algorithm then assigned the correct value to each element, and the total score was electronically calculated and placed in a discrete cell in each patient’s record. The algorithm was automatically run again 48 hours after the initial scoring in order to assure completeness of the information. If the patient had a length of stay greater than 5 days, an additional score was generated to include the length of stay component.

Statistical Analysis

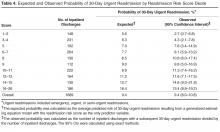

The predictive performance of the RRS was assessed by evaluating the discrimination and calibration. Discrimination is the ability of the RRS to separate those who had a 30-day urgent readmission and those who did not. Discrimination was quantified by the c statistic, which is equivalent to the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve in this study owing to the use of binary endpoints. A c statistic of 1.0 would indicate that the RRS perfectly predicts 30-day urgent readmission while a c statistic of 0.5 would indicate the RRS has no apparent accuracy in predicting 30-day urgent readmission. Calibration assesses how closely predicted outcomes agree with observed outcomes. The predicted probability of 30-day urgent readmission was estimated utilizing a generalized estimating equation model, clustering on patient, with RRS as the only predictor variable. Inpatient discharges were divided into deciles of the predicted probabilities for 30-day urgent readmission. Agreement of the predicted and observed outcomes was displayed graphically according to decile of the predicted outcomes. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R statistical software (version 3.1.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

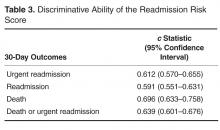

The RRS was significantly associated with 30-day urgent readmission (odds ratio [OR] for 1-point increase in the RRS, 1.07 [95% confidence interval {CI} 1.05–1.10]; P < 0.001). A c statistic of 0.612 (95% CI 0.570–0.655) indicates that the RRS has some ability to discriminate between those with and without a 30-day urgent readmission (Figure, Table 3). The expected and observed probabilities of 30-day urgent readmission were similar in each decile of the RRS. The calibration (Table 4) shows that although there is some deviation between the observed and expected probabilities,

The RRS was also significantly associated with each of the secondary outcome measures. The odds ratios for a 1-point increase in the RRS for any 30-day readmission was 1.06 (95% CI 1.03–1.09, P < 0.001) and the c statistic was 0.591 (95% CI 0.551–0.631, Table 2). The odds ratios for a 1-point increase in the

Discussion

Our study provides evidence that the RRS has some ability to discriminate between patients who did and did not have a 30-day urgent readmission (c statistic 0.612 [95% CI 0.570–0.655]). More importantly the calibration appears to be good particularly in the higher risk patients, which are the most crucial to identify in order to target interventions.

In addition to predicting the risk of readmission, our method of risk evaluation has several other advantages. First, the risk score is assigned to each patient within 24 to 48 hours of admission by using elements available at the time of, or soon after, admission. This early evaluation during the hospitalization identifies patients who could benefit from interventions throughout the stay that could help mitigate the risks and allow for a safer transition. Other studies have used elements available only at discharge, such as lab values and length of stay [7,11]. Donze et al used 7 elements in a validated scoring system, but several of the elements were discharge values and the risk assessment system had a fair discriminatory value with a c statistic of 0.71, similar to our results. The advantage to having the score available at admission is that several of the factors used to compose the RRS could be addressed during the hospitalization, including increased education for those with greater than 7 medications, intensive care management intervention for those with a lack of social support, and increased or modified education for those with low health literacy.

Second, the score is derived entirely from elements available in the EMR, thus the score is calculated automatically within 24 hours of admission and displayed in the chart for all providers to access. This eliminates any need for individual chart review or patient evaluation outside the normal admission process, making this system extremely efficient. Van Walraven et al [9] devised a scoring system using length of stay, acuity of admission, comorbidities and emergency department use (LACE index), with a validation c statistic of 0.684, which again is similar to our results. However, the LACE index uses the Charlson comorbidity index as a measure of patient comorbidity and this can be cumbersome to calculate in clinical practice. Having the score automatically available to all providers caring for the patient increases their awareness of the patient’s level of risk. Allaudeen and colleagues showed that providers are unable to intuitively predict those patients who are at high-risk for readmission [15]; therefore, an objective, readily available risk stratification is necessary to inform the providers.

Third, the risk scoring system uses elements from varied sources to include social, medical, and individual factors, all of which have been shown to increase risk of 30-day readmissions [9,15]. An accurate risk scoring system, ideally, should include elements from multiple sources, and use of the EMR allows for this varied compilation. The risk evaluation is done on every patient, regardless of admitting diagnosis, and in spite of this heterogeneous population, it was still found to be significantly accurate. Prior studies have looked at individual populations [7,10,12,13,16]; however, this can miss many patient populations that are also high-risk. Tailoring individual risk algorithms by diagnosis can also be labor intensive.

Our study has limitations. It is a retrospective study and included a relatively short study period of 2 months. This period was chosen because it represented the time from when the RRS was first implemented to when interventions to reduce readmission according to the RRS began, however, it still encompassed a significant number of discharges. We were only able to evaluate readmissions to our own facility; therefore, patients readmitted to other facilities were not included. Although readmission to any facility is undesirable, having a risk scoring system that can reliably predict readmission to the index admission hospital is still helpful. In addition, we only validated the risk score on patients in our own facility. A larger population from multiple facilities would be helpful for further validation. In spite of this limitation we would expect that most of our readmissions return to our own facility given our community setting. In fact, based on Medicare data for readmissions to all facilities, the difference in readmission rate between our facility and all facilities differs by less than 4%.

In summary, we developed a comprehensive risk scoring system that proved to be moderately predictive of readmission that encompasses multiple factors, is available to all providers early in a hospitalization, and is completely automated via the EMR. Further studies are ongoing to refine this score and improve the predictive performance.

Corresponding author: Nancy L. Dawson, MD, Division of Hospital Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 4500 San Pablo Road, Jacksonville, FL 32224, dawson.nancy11@mayo.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Statistical Brief #153: Readmissions to U.S. hospitals by diagnosis, 2010. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. Available at www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb153.pdf.

2. Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:178–87.

3. Boutwell A, Hwu S. Effective interventions to reduce rehospitalizations: a survey of the published evidence. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2009. Available at www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Publications/EffectiveInterventionsReduceRehospitalizationsASurveyPublishedEvidence.aspx.

4. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, et al. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:520–8.

5. Kripalani S, Theobald CN, Anctil B, Vasilevskis EE. Reducing hospital readmission rates: current strategies and future directions. Ann Rev Med 2014;65:471–85.

6. Osei-Anto A, Joshi M, Audet AM, et al. Health care leader action guide to reduce avoidable readmissions. Chicago: Health Research & Educational Trust; 2010. Available at www.hret.org/care/projects/resources/readmissions_cp.pdf.

7. Zaya M, Phan A, Schwarz ER. Predictors of re-hospitalization in patients with chronic heart failure. World J Cardiol 2012;4:23–30.

8. Hu J, Gonsahn MD, Nerenz DR. Socioeconomic status and readmissions: evidence from an urban teaching hospital. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:778–85.

9. van Walraven C, Dhalla IA, Bell C, et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ 2010;182:551–7.

10. Rana S, Tran T, Luo W, et al. Predicting unplanned readmission after myocardial infarction from routinely collected administrative hospital data. Aust Health Rev 2014;38:377–82.

11. Donze J, Aujesky D, Williams D, Schnipper JL. Potentially avoidable 30-day hospital readmissions in medical patients: derivation and validation of a prediction model. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:632–8.

12. Kogon B, Jain A, Oster M, et al. Risk factors associated with readmission after pediatric cardiothoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:865–73.

13. Harhay M, Lin E, Pai A, et al. Early rehospitalization after kidney transplantation: assessing preventability and prognosis. Am J Transplant 2013;13:3164–72.

14. Preventing unnecessary readmissions: transcending the hospital’s four walls to achieve collaborative care coordination. The Advisory Board Company; 2010. Available at www.advisory.com/research/physician-executive-council/studies/2010/preventing-unnecessary-readmissions.

15. Allaudeen N, Schnipper JL, Orav EJ, et al. Inability of providers to predict unplanned readmissions. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:771–6.

16. Calvillo-King L, Arnold D, Eubank KJ, et al. Impact of social factors on risk of readmission or mortality in pneumonia and heart failure: systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:269–82.

From the Divisions of Hospital Medicine (Drs. Dawson, Chirila, Bhide, and Burton) and Biomedical Statistics and Informatics (Ms. Thomas), Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, and the Division of Hospital Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, AZ (Dr. Cannon).

Abstract

- Objective: To validate an electronic tool created to identify inpatients who are at risk of readmission within 30 days and quantify the predictive performance of the readmission risk score (RRS).

- Methods: Retrospective cohort study including inpa-tients who were discharged between 1 Nov 2012 and 31 Dec 2012. The ability of the RRS to discriminate between those who did and did not have a 30-day urgent readmission was quantified by the c statistic. Calibration was assessed by plotting the observed and predicted probability of 30-day urgent readmission. Predicted probabilities were obtained from generalized estimating equations, clustering on patient.

- Results: Of 1689 hospital inpatient discharges (1515 patients), 159 (9.4%) had a 30-day urgent readmission. The RRS had some discriminative ability (c statistic: 0.612; 95% confidence interval: 0.570–0.655) and good calibration.

- Conclusions: Our study shows that the RRS has some discriminative ability. The automated tool can be used to estimate the probability of a 30-day urgent readmission.

Hospital readmissions are increasingly scrutinized by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers due to their frequency and high cost. It is estimated that up to 25% of all patients discharged from acute care hospitals are readmitted within 30 days [1]. To address this problem, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services is using these rates as one of the benchmarks for quality for hospitals and health care organizations and has begun to assess penalties to those institutions with the highest rates. This scrutiny and the desire for better patient care transitions has resulted in most hospitals implementing various initiatives to reduce potentially avoidable readmissions.

Multiple interventions have been shown to reduce readmissions [2,3]. These interventions have varying effectiveness and are often labor intensive and thus costly to the institutions implementing them. In fact, no one intervention has been shown to be effective alone [4], and it may take several concurrent interventions targeting the highest risk patients to improve transitions of care at discharge that result in reduced readmissions. Many experts do recommend risk stratifying patients in order to target interventions to the highest risk patients for effective use of resources [5,6]. Several risk factor assessments have been proposed with varying success [7–13]. Multiple factors can limit the effectiveness of these risk stratification profiles. They may have low sensitivity and specificity, be based solely on retrospective data, be limited to certain populations, or be created from administrative data only without taking psychosocial factors into consideration [14].

An effective risk assessment ideally would encompass multiple known risk factors including certain comorbidities such as malignancy and heart failure, psychosocial factors such as health literacy and social support, and administrative data including payment source and demographics. All of these have been shown in prior studies to contribute to readmissions [7–13]. In addition, availability of the assessment early in the hospitalization would allow for interventions throughout the hospital stay to mitigate the effect of these factors where possible. To address these needs, our institution formed a readmission task force in January 2010 to review published literature on hospital 30-day readmissions and create a readmission risk score (RRS). The aim of this study was to quantify the predictive performance of the RRS after it was first implemented into the electronic medical record (EMR) in November 2012.

Methods

Study Design and Cohort

All consecutive adult inpatients who were discharged between 1 November 2012 and 31 December 2012 were included in this retrospective cohort study. This narrow time frame corresponded to the period from RRS tool implementation to the start of readmission interventions. We excluded hospitalizations if the patient died in the hospital.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was a 30-day urgent readmission, which included readmissions categorized as either emergency, urgent, or semi-urgent. Secondary outcomes included any 30-day readmission and 30-day death. Only readmissions to Mayo Clinic were examined.

Predictors

In collaboration with the information technology department, an algorithm was written to extract data from the EMR for each patient within 24 hours of admission to the hospital. This data was retrieved from existing repositories of patient information, such as demographic information, payer source, medication list, problem list, and past medical history. In addition, each patient was interviewed by a nurse at the time of admission, and the nurse completed an “admission profile” in the EMR that confirmed or entered past medical history, medications, social support at home, depression symptoms, and learning styles, among other information (Table 1). The algorithm was able to extract data from this evaluation also, so that each element of the risk score was correlated to at least one data source in the EMR. The algorithm then assigned the correct value to each element, and the total score was electronically calculated and placed in a discrete cell in each patient’s record. The algorithm was automatically run again 48 hours after the initial scoring in order to assure completeness of the information. If the patient had a length of stay greater than 5 days, an additional score was generated to include the length of stay component.

Statistical Analysis

The predictive performance of the RRS was assessed by evaluating the discrimination and calibration. Discrimination is the ability of the RRS to separate those who had a 30-day urgent readmission and those who did not. Discrimination was quantified by the c statistic, which is equivalent to the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve in this study owing to the use of binary endpoints. A c statistic of 1.0 would indicate that the RRS perfectly predicts 30-day urgent readmission while a c statistic of 0.5 would indicate the RRS has no apparent accuracy in predicting 30-day urgent readmission. Calibration assesses how closely predicted outcomes agree with observed outcomes. The predicted probability of 30-day urgent readmission was estimated utilizing a generalized estimating equation model, clustering on patient, with RRS as the only predictor variable. Inpatient discharges were divided into deciles of the predicted probabilities for 30-day urgent readmission. Agreement of the predicted and observed outcomes was displayed graphically according to decile of the predicted outcomes. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R statistical software (version 3.1.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

The RRS was significantly associated with 30-day urgent readmission (odds ratio [OR] for 1-point increase in the RRS, 1.07 [95% confidence interval {CI} 1.05–1.10]; P < 0.001). A c statistic of 0.612 (95% CI 0.570–0.655) indicates that the RRS has some ability to discriminate between those with and without a 30-day urgent readmission (Figure, Table 3). The expected and observed probabilities of 30-day urgent readmission were similar in each decile of the RRS. The calibration (Table 4) shows that although there is some deviation between the observed and expected probabilities,

The RRS was also significantly associated with each of the secondary outcome measures. The odds ratios for a 1-point increase in the RRS for any 30-day readmission was 1.06 (95% CI 1.03–1.09, P < 0.001) and the c statistic was 0.591 (95% CI 0.551–0.631, Table 2). The odds ratios for a 1-point increase in the

Discussion

Our study provides evidence that the RRS has some ability to discriminate between patients who did and did not have a 30-day urgent readmission (c statistic 0.612 [95% CI 0.570–0.655]). More importantly the calibration appears to be good particularly in the higher risk patients, which are the most crucial to identify in order to target interventions.

In addition to predicting the risk of readmission, our method of risk evaluation has several other advantages. First, the risk score is assigned to each patient within 24 to 48 hours of admission by using elements available at the time of, or soon after, admission. This early evaluation during the hospitalization identifies patients who could benefit from interventions throughout the stay that could help mitigate the risks and allow for a safer transition. Other studies have used elements available only at discharge, such as lab values and length of stay [7,11]. Donze et al used 7 elements in a validated scoring system, but several of the elements were discharge values and the risk assessment system had a fair discriminatory value with a c statistic of 0.71, similar to our results. The advantage to having the score available at admission is that several of the factors used to compose the RRS could be addressed during the hospitalization, including increased education for those with greater than 7 medications, intensive care management intervention for those with a lack of social support, and increased or modified education for those with low health literacy.

Second, the score is derived entirely from elements available in the EMR, thus the score is calculated automatically within 24 hours of admission and displayed in the chart for all providers to access. This eliminates any need for individual chart review or patient evaluation outside the normal admission process, making this system extremely efficient. Van Walraven et al [9] devised a scoring system using length of stay, acuity of admission, comorbidities and emergency department use (LACE index), with a validation c statistic of 0.684, which again is similar to our results. However, the LACE index uses the Charlson comorbidity index as a measure of patient comorbidity and this can be cumbersome to calculate in clinical practice. Having the score automatically available to all providers caring for the patient increases their awareness of the patient’s level of risk. Allaudeen and colleagues showed that providers are unable to intuitively predict those patients who are at high-risk for readmission [15]; therefore, an objective, readily available risk stratification is necessary to inform the providers.

Third, the risk scoring system uses elements from varied sources to include social, medical, and individual factors, all of which have been shown to increase risk of 30-day readmissions [9,15]. An accurate risk scoring system, ideally, should include elements from multiple sources, and use of the EMR allows for this varied compilation. The risk evaluation is done on every patient, regardless of admitting diagnosis, and in spite of this heterogeneous population, it was still found to be significantly accurate. Prior studies have looked at individual populations [7,10,12,13,16]; however, this can miss many patient populations that are also high-risk. Tailoring individual risk algorithms by diagnosis can also be labor intensive.

Our study has limitations. It is a retrospective study and included a relatively short study period of 2 months. This period was chosen because it represented the time from when the RRS was first implemented to when interventions to reduce readmission according to the RRS began, however, it still encompassed a significant number of discharges. We were only able to evaluate readmissions to our own facility; therefore, patients readmitted to other facilities were not included. Although readmission to any facility is undesirable, having a risk scoring system that can reliably predict readmission to the index admission hospital is still helpful. In addition, we only validated the risk score on patients in our own facility. A larger population from multiple facilities would be helpful for further validation. In spite of this limitation we would expect that most of our readmissions return to our own facility given our community setting. In fact, based on Medicare data for readmissions to all facilities, the difference in readmission rate between our facility and all facilities differs by less than 4%.

In summary, we developed a comprehensive risk scoring system that proved to be moderately predictive of readmission that encompasses multiple factors, is available to all providers early in a hospitalization, and is completely automated via the EMR. Further studies are ongoing to refine this score and improve the predictive performance.

Corresponding author: Nancy L. Dawson, MD, Division of Hospital Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 4500 San Pablo Road, Jacksonville, FL 32224, dawson.nancy11@mayo.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Divisions of Hospital Medicine (Drs. Dawson, Chirila, Bhide, and Burton) and Biomedical Statistics and Informatics (Ms. Thomas), Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, and the Division of Hospital Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Phoenix, AZ (Dr. Cannon).

Abstract

- Objective: To validate an electronic tool created to identify inpatients who are at risk of readmission within 30 days and quantify the predictive performance of the readmission risk score (RRS).

- Methods: Retrospective cohort study including inpa-tients who were discharged between 1 Nov 2012 and 31 Dec 2012. The ability of the RRS to discriminate between those who did and did not have a 30-day urgent readmission was quantified by the c statistic. Calibration was assessed by plotting the observed and predicted probability of 30-day urgent readmission. Predicted probabilities were obtained from generalized estimating equations, clustering on patient.

- Results: Of 1689 hospital inpatient discharges (1515 patients), 159 (9.4%) had a 30-day urgent readmission. The RRS had some discriminative ability (c statistic: 0.612; 95% confidence interval: 0.570–0.655) and good calibration.

- Conclusions: Our study shows that the RRS has some discriminative ability. The automated tool can be used to estimate the probability of a 30-day urgent readmission.

Hospital readmissions are increasingly scrutinized by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other payers due to their frequency and high cost. It is estimated that up to 25% of all patients discharged from acute care hospitals are readmitted within 30 days [1]. To address this problem, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services is using these rates as one of the benchmarks for quality for hospitals and health care organizations and has begun to assess penalties to those institutions with the highest rates. This scrutiny and the desire for better patient care transitions has resulted in most hospitals implementing various initiatives to reduce potentially avoidable readmissions.

Multiple interventions have been shown to reduce readmissions [2,3]. These interventions have varying effectiveness and are often labor intensive and thus costly to the institutions implementing them. In fact, no one intervention has been shown to be effective alone [4], and it may take several concurrent interventions targeting the highest risk patients to improve transitions of care at discharge that result in reduced readmissions. Many experts do recommend risk stratifying patients in order to target interventions to the highest risk patients for effective use of resources [5,6]. Several risk factor assessments have been proposed with varying success [7–13]. Multiple factors can limit the effectiveness of these risk stratification profiles. They may have low sensitivity and specificity, be based solely on retrospective data, be limited to certain populations, or be created from administrative data only without taking psychosocial factors into consideration [14].

An effective risk assessment ideally would encompass multiple known risk factors including certain comorbidities such as malignancy and heart failure, psychosocial factors such as health literacy and social support, and administrative data including payment source and demographics. All of these have been shown in prior studies to contribute to readmissions [7–13]. In addition, availability of the assessment early in the hospitalization would allow for interventions throughout the hospital stay to mitigate the effect of these factors where possible. To address these needs, our institution formed a readmission task force in January 2010 to review published literature on hospital 30-day readmissions and create a readmission risk score (RRS). The aim of this study was to quantify the predictive performance of the RRS after it was first implemented into the electronic medical record (EMR) in November 2012.

Methods

Study Design and Cohort

All consecutive adult inpatients who were discharged between 1 November 2012 and 31 December 2012 were included in this retrospective cohort study. This narrow time frame corresponded to the period from RRS tool implementation to the start of readmission interventions. We excluded hospitalizations if the patient died in the hospital.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was a 30-day urgent readmission, which included readmissions categorized as either emergency, urgent, or semi-urgent. Secondary outcomes included any 30-day readmission and 30-day death. Only readmissions to Mayo Clinic were examined.

Predictors

In collaboration with the information technology department, an algorithm was written to extract data from the EMR for each patient within 24 hours of admission to the hospital. This data was retrieved from existing repositories of patient information, such as demographic information, payer source, medication list, problem list, and past medical history. In addition, each patient was interviewed by a nurse at the time of admission, and the nurse completed an “admission profile” in the EMR that confirmed or entered past medical history, medications, social support at home, depression symptoms, and learning styles, among other information (Table 1). The algorithm was able to extract data from this evaluation also, so that each element of the risk score was correlated to at least one data source in the EMR. The algorithm then assigned the correct value to each element, and the total score was electronically calculated and placed in a discrete cell in each patient’s record. The algorithm was automatically run again 48 hours after the initial scoring in order to assure completeness of the information. If the patient had a length of stay greater than 5 days, an additional score was generated to include the length of stay component.

Statistical Analysis

The predictive performance of the RRS was assessed by evaluating the discrimination and calibration. Discrimination is the ability of the RRS to separate those who had a 30-day urgent readmission and those who did not. Discrimination was quantified by the c statistic, which is equivalent to the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve in this study owing to the use of binary endpoints. A c statistic of 1.0 would indicate that the RRS perfectly predicts 30-day urgent readmission while a c statistic of 0.5 would indicate the RRS has no apparent accuracy in predicting 30-day urgent readmission. Calibration assesses how closely predicted outcomes agree with observed outcomes. The predicted probability of 30-day urgent readmission was estimated utilizing a generalized estimating equation model, clustering on patient, with RRS as the only predictor variable. Inpatient discharges were divided into deciles of the predicted probabilities for 30-day urgent readmission. Agreement of the predicted and observed outcomes was displayed graphically according to decile of the predicted outcomes. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R statistical software (version 3.1.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

The RRS was significantly associated with 30-day urgent readmission (odds ratio [OR] for 1-point increase in the RRS, 1.07 [95% confidence interval {CI} 1.05–1.10]; P < 0.001). A c statistic of 0.612 (95% CI 0.570–0.655) indicates that the RRS has some ability to discriminate between those with and without a 30-day urgent readmission (Figure, Table 3). The expected and observed probabilities of 30-day urgent readmission were similar in each decile of the RRS. The calibration (Table 4) shows that although there is some deviation between the observed and expected probabilities,

The RRS was also significantly associated with each of the secondary outcome measures. The odds ratios for a 1-point increase in the RRS for any 30-day readmission was 1.06 (95% CI 1.03–1.09, P < 0.001) and the c statistic was 0.591 (95% CI 0.551–0.631, Table 2). The odds ratios for a 1-point increase in the

Discussion

Our study provides evidence that the RRS has some ability to discriminate between patients who did and did not have a 30-day urgent readmission (c statistic 0.612 [95% CI 0.570–0.655]). More importantly the calibration appears to be good particularly in the higher risk patients, which are the most crucial to identify in order to target interventions.

In addition to predicting the risk of readmission, our method of risk evaluation has several other advantages. First, the risk score is assigned to each patient within 24 to 48 hours of admission by using elements available at the time of, or soon after, admission. This early evaluation during the hospitalization identifies patients who could benefit from interventions throughout the stay that could help mitigate the risks and allow for a safer transition. Other studies have used elements available only at discharge, such as lab values and length of stay [7,11]. Donze et al used 7 elements in a validated scoring system, but several of the elements were discharge values and the risk assessment system had a fair discriminatory value with a c statistic of 0.71, similar to our results. The advantage to having the score available at admission is that several of the factors used to compose the RRS could be addressed during the hospitalization, including increased education for those with greater than 7 medications, intensive care management intervention for those with a lack of social support, and increased or modified education for those with low health literacy.

Second, the score is derived entirely from elements available in the EMR, thus the score is calculated automatically within 24 hours of admission and displayed in the chart for all providers to access. This eliminates any need for individual chart review or patient evaluation outside the normal admission process, making this system extremely efficient. Van Walraven et al [9] devised a scoring system using length of stay, acuity of admission, comorbidities and emergency department use (LACE index), with a validation c statistic of 0.684, which again is similar to our results. However, the LACE index uses the Charlson comorbidity index as a measure of patient comorbidity and this can be cumbersome to calculate in clinical practice. Having the score automatically available to all providers caring for the patient increases their awareness of the patient’s level of risk. Allaudeen and colleagues showed that providers are unable to intuitively predict those patients who are at high-risk for readmission [15]; therefore, an objective, readily available risk stratification is necessary to inform the providers.

Third, the risk scoring system uses elements from varied sources to include social, medical, and individual factors, all of which have been shown to increase risk of 30-day readmissions [9,15]. An accurate risk scoring system, ideally, should include elements from multiple sources, and use of the EMR allows for this varied compilation. The risk evaluation is done on every patient, regardless of admitting diagnosis, and in spite of this heterogeneous population, it was still found to be significantly accurate. Prior studies have looked at individual populations [7,10,12,13,16]; however, this can miss many patient populations that are also high-risk. Tailoring individual risk algorithms by diagnosis can also be labor intensive.

Our study has limitations. It is a retrospective study and included a relatively short study period of 2 months. This period was chosen because it represented the time from when the RRS was first implemented to when interventions to reduce readmission according to the RRS began, however, it still encompassed a significant number of discharges. We were only able to evaluate readmissions to our own facility; therefore, patients readmitted to other facilities were not included. Although readmission to any facility is undesirable, having a risk scoring system that can reliably predict readmission to the index admission hospital is still helpful. In addition, we only validated the risk score on patients in our own facility. A larger population from multiple facilities would be helpful for further validation. In spite of this limitation we would expect that most of our readmissions return to our own facility given our community setting. In fact, based on Medicare data for readmissions to all facilities, the difference in readmission rate between our facility and all facilities differs by less than 4%.

In summary, we developed a comprehensive risk scoring system that proved to be moderately predictive of readmission that encompasses multiple factors, is available to all providers early in a hospitalization, and is completely automated via the EMR. Further studies are ongoing to refine this score and improve the predictive performance.

Corresponding author: Nancy L. Dawson, MD, Division of Hospital Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 4500 San Pablo Road, Jacksonville, FL 32224, dawson.nancy11@mayo.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Statistical Brief #153: Readmissions to U.S. hospitals by diagnosis, 2010. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. Available at www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb153.pdf.

2. Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:178–87.

3. Boutwell A, Hwu S. Effective interventions to reduce rehospitalizations: a survey of the published evidence. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2009. Available at www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Publications/EffectiveInterventionsReduceRehospitalizationsASurveyPublishedEvidence.aspx.

4. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, et al. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:520–8.

5. Kripalani S, Theobald CN, Anctil B, Vasilevskis EE. Reducing hospital readmission rates: current strategies and future directions. Ann Rev Med 2014;65:471–85.

6. Osei-Anto A, Joshi M, Audet AM, et al. Health care leader action guide to reduce avoidable readmissions. Chicago: Health Research & Educational Trust; 2010. Available at www.hret.org/care/projects/resources/readmissions_cp.pdf.

7. Zaya M, Phan A, Schwarz ER. Predictors of re-hospitalization in patients with chronic heart failure. World J Cardiol 2012;4:23–30.

8. Hu J, Gonsahn MD, Nerenz DR. Socioeconomic status and readmissions: evidence from an urban teaching hospital. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:778–85.

9. van Walraven C, Dhalla IA, Bell C, et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ 2010;182:551–7.

10. Rana S, Tran T, Luo W, et al. Predicting unplanned readmission after myocardial infarction from routinely collected administrative hospital data. Aust Health Rev 2014;38:377–82.

11. Donze J, Aujesky D, Williams D, Schnipper JL. Potentially avoidable 30-day hospital readmissions in medical patients: derivation and validation of a prediction model. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:632–8.

12. Kogon B, Jain A, Oster M, et al. Risk factors associated with readmission after pediatric cardiothoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:865–73.

13. Harhay M, Lin E, Pai A, et al. Early rehospitalization after kidney transplantation: assessing preventability and prognosis. Am J Transplant 2013;13:3164–72.

14. Preventing unnecessary readmissions: transcending the hospital’s four walls to achieve collaborative care coordination. The Advisory Board Company; 2010. Available at www.advisory.com/research/physician-executive-council/studies/2010/preventing-unnecessary-readmissions.

15. Allaudeen N, Schnipper JL, Orav EJ, et al. Inability of providers to predict unplanned readmissions. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:771–6.

16. Calvillo-King L, Arnold D, Eubank KJ, et al. Impact of social factors on risk of readmission or mortality in pneumonia and heart failure: systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:269–82.

1. Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Statistical Brief #153: Readmissions to U.S. hospitals by diagnosis, 2010. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. Available at www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb153.pdf.

2. Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:178–87.

3. Boutwell A, Hwu S. Effective interventions to reduce rehospitalizations: a survey of the published evidence. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2009. Available at www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Publications/EffectiveInterventionsReduceRehospitalizationsASurveyPublishedEvidence.aspx.

4. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, et al. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:520–8.

5. Kripalani S, Theobald CN, Anctil B, Vasilevskis EE. Reducing hospital readmission rates: current strategies and future directions. Ann Rev Med 2014;65:471–85.

6. Osei-Anto A, Joshi M, Audet AM, et al. Health care leader action guide to reduce avoidable readmissions. Chicago: Health Research & Educational Trust; 2010. Available at www.hret.org/care/projects/resources/readmissions_cp.pdf.

7. Zaya M, Phan A, Schwarz ER. Predictors of re-hospitalization in patients with chronic heart failure. World J Cardiol 2012;4:23–30.

8. Hu J, Gonsahn MD, Nerenz DR. Socioeconomic status and readmissions: evidence from an urban teaching hospital. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:778–85.

9. van Walraven C, Dhalla IA, Bell C, et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ 2010;182:551–7.

10. Rana S, Tran T, Luo W, et al. Predicting unplanned readmission after myocardial infarction from routinely collected administrative hospital data. Aust Health Rev 2014;38:377–82.

11. Donze J, Aujesky D, Williams D, Schnipper JL. Potentially avoidable 30-day hospital readmissions in medical patients: derivation and validation of a prediction model. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:632–8.

12. Kogon B, Jain A, Oster M, et al. Risk factors associated with readmission after pediatric cardiothoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:865–73.

13. Harhay M, Lin E, Pai A, et al. Early rehospitalization after kidney transplantation: assessing preventability and prognosis. Am J Transplant 2013;13:3164–72.

14. Preventing unnecessary readmissions: transcending the hospital’s four walls to achieve collaborative care coordination. The Advisory Board Company; 2010. Available at www.advisory.com/research/physician-executive-council/studies/2010/preventing-unnecessary-readmissions.

15. Allaudeen N, Schnipper JL, Orav EJ, et al. Inability of providers to predict unplanned readmissions. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:771–6.

16. Calvillo-King L, Arnold D, Eubank KJ, et al. Impact of social factors on risk of readmission or mortality in pneumonia and heart failure: systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2013;28:269–82.

Physician Burnout Meta‐analysis

Hospital medicine is a rapidly growing field of US clinical practice.[1] Almost since its advent, concerns have been expressed about the potential for hospitalists to burn out.[2] Hospitalists are not unique in this; similar concerns heralded the arrival of other location‐defined specialties, including emergency medicine[3] and the full‐time intensivist model,[4] a fact that has not gone unnoted in the literature about hospitalists.[5]

The existing international literature on physician burnout provides good reason for this concern. Inpatient‐based physicians tend to work unpredictable schedules, with substantial impact on home life.[6] They tend to be young, and much burnout literature suggests a higher risk among younger, less‐experienced physicians.[7] When surveyed, hospitalists have expressed more concerns about their potential for burnout than their outpatient‐based colleagues.[8]

In fact, data suggesting a correlation between inpatient practice and burnout predate the advent of the US hospitalist movement. Increased hospital time was reported to correlate with higher rates of burnout in internists,[9] family practitioners,[10] palliative physicians,[11] junior doctors,[12] radiologists,[13] and cystic fibrosis caregivers.[14] In 1987, Keinan and Melamed[15] noted, Hospital work by its very nature, as compared to the work of a general practitioner, deals with the more severe and complicated illnesses, coupled with continuous daily contacts with patients and their anxious families. In addition, these physicians may find themselves embroiled in the power struggles and competition so common in their work environment.

There are other features, however, that may protect inpatient physicians from burnout. Hospital practice can facilitate favorable social relations involving colleagues, co‐workers, and patients,[16] a factor that may be protective.[17] A hospitalist schedule also can allow more focused time for continuing medical education, research, and teaching,[18] which have all been associated with reduced risk of burnout in some studies.[17] Studies of psychiatrists[19] and pediatricians[20] have shown a lower rate of burnout among physicians with more inpatient duties. Finally, a practice model involving a seemingly stable cadre of inpatient physicians has existed in Europe for decades,[2] indicating at least a degree of sustainability.

Information suggesting a higher rate of burnout among inpatient physicians could be used to target therapeutic interventions and to adjust schedules, whereas the opposite outcome could refute a pervasive myth. We therefore endeavored to summarize the literature on burnout among inpatient versus outpatient physicians in a systematic fashion, and to include data not only from the US hospitalist experience but also from other countries that have used a similar model for decades. Our primary hypothesis was that inpatient physicians experience more burnout than outpatient physicians.

It is important to distinguish burnout from depression, job dissatisfaction, and occupational stress, all of which have been studied extensively in physicians. Burnout, as introduced by Freudenberger[21] and further characterized by Maslach,[22] is a condition in which emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a low sense of personal accomplishment combine to negatively affect work life (as opposed to clinical depression, which affects all aspects of life). Job satisfaction can correlate inversely with burnout, but it is a separate process[23] and the subject of a recent systematic review.[24] The importance of distinguishing burnout from job dissatisfaction is illustrated by a survey of head and neck surgeons, in which 97% of those surveyed indicated satisfaction with their jobs and 34% of the same group answered in the affirmative when asked if they felt burned out.[25]

One obstacle to the meaningful comparison of burnout prevalence across time, geography, and specialty is the myriad ways in which burnout is measured and reported. The oldest and most commonly used instrument to measure burnout is the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), which contains 22 items assessing 3 components of burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment).[26] Other measures include the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory[27] (19 items with the components personal burnout, work‐related burnout, and client‐related burnout), Utrecht Burnout Inventory[28] (20‐item modification of the MBI), Boudreau Burnout Questionnaire[29] (30 items), Arbeitsbezogenes Verhaltens und Erlebensmuster[30] (66‐item questionnaire assessing professional commitment, resistance to stress, and emotional well‐being), Shirom‐Melamed Burnout Measure[31] (22 items with subscales for physical fatigue, cognitive weariness, tension, and listlessness), and a validated single‐item questionnaire.[32]

METHODS

Electronic searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, SCOPUS, and PubMed were undertaken for articles published from January 1, 1974 (the year in which burnout was first described by Freudenberger[21]) to 2012 (last accessed, September 12, 2012) using the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms stress, psychological; burnout, professional; adaptation, psychological; and the keyword burnout. The same sources were searched to create another set for the MeSH terms hospitalists, physician's practice patterns, physicians/px, professional practice location, and the keyword hospitalist#. Where exact subject headings did not exist in databases, comparable subject headings or keywords were used. The 2 sets were then combined using the operator and. Abstracts from the Society of Hospital Medicine annual conferences were hand‐searched, as were reference lists from identified articles. To ensure that pertinent international literature was captured, there was no language restriction in the search.

A 2‐stage screening process was used. The titles and abstracts of all articles identified in the search were independently reviewed by 2 investigators (D.L.R. and K.J.C.) who had no knowledge of each other's results. An article was obtained when either reviewer deemed it worthy of full‐text review.

All full‐text articles were independently reviewed by the same 2 investigators. The inclusion criterion was the measurement of burnout in physicians who are stated to or can be reasonably assumed to spend the substantial majority of their clinical practice exclusively in either the inpatient or the outpatient setting. Studies of emergency department physicians or specialists who invariably spend substantial amounts of time in both settings (eg, surgeons, anesthesiologists) were excluded. Studies limited to trainees or nonphysicians were also excluded. For both stages of review, agreement between the 2 investigators was assessed by calculating the statistic. Disagreements about inclusion were adjudicated by a third investigator (A.I.B.).

Because our goal was to establish and compare the rate of burnout among US hospitalists and other inpatient physicians around the world, we included studies of hospitalists according to the definition in use at the time of the individual study, noting that the formal definition of a hospitalist has changed over the years.[33] Because practice patterns for physicians described as primary care physicians, family doctors, hospital doctors, and others differ substantially from country to country, we otherwise included only the studies where the practice location was stated explicitly or where the authors confirmed that their study participants either are known or can be reasonably assumed to spend more than 75% of their time caring for hospital inpatients, or are known or can be reasonably assumed to spend the vast majority of their time caring for outpatients.

Data were abstracted using a standardized form and included the measure of burnout used in the study, results, practice location of study subjects, and total number of study subjects. When data were not clear (eg, burnout measured but not reported by the authors, practice location of study subjects not clear), authors were contacted by email, or when no current email address could be located or no response was received, by telephone or letter. In instances where burnout was measured repeatedly over time or before and after a specific intervention, only the baseline measurement was recorded. Because all studies were expected to be nonrandomized, methodological quality was assessed using a version of the tool of Downs and Black,[34] adapted where necessary by omitting questions not applicable to the specific study type (eg randomization for survey studies)[35] and giving a maximum of 1 point for the inclusion of a power calculation.

Two a priori analyses were planned: (1) a statistical comparison of articles directly comparing burnout among inpatient and outpatient physicians, and (2) a statistical comparison of articles measuring burnout among inpatient physicians with articles measuring burnout among outpatient physicians by the most frequently reported measuremean subset scores for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment on the MBI.

The primary outcome measures were the differences between mean subset scores for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment on the MBI. All differences are expressed as (outpatient meaninpatient mean). The variance of each outcome was calculated with standard formulas.[36] To calculate the overall estimate, each study was weighted by the reciprocal of its variance. Studies with fewer than 10 subjects were excluded from statistical analysis but retained in the systematic review.

For studies that reported data for both inpatient and outpatient physicians (double‐armed studies), Cochran Q test and the I2 value were used to assess heterogeneity.[37, 38] Substantial heterogeneity was expected because these individual studies were conducted for different populations in different settings with different study designs, and this expectation was confirmed statistically. Therefore, we used a random effects model to estimate the overall effect, providing a conservative approach that accounted for heterogeneity among studies.[39]

To assess the durability of our findings, we performed separate multivariate meta‐regression analyses by including single‐armed studies only and including both single‐armed and double‐armed studies. For these meta‐regressions, means were again weighted by the reciprocal of their variances, and the arms of 2‐armed studies were considered separately. This approach allowed us to generate an estimate of the differences between MBI subset scores from studies that did not include such an estimate when analyzed separately.[40]

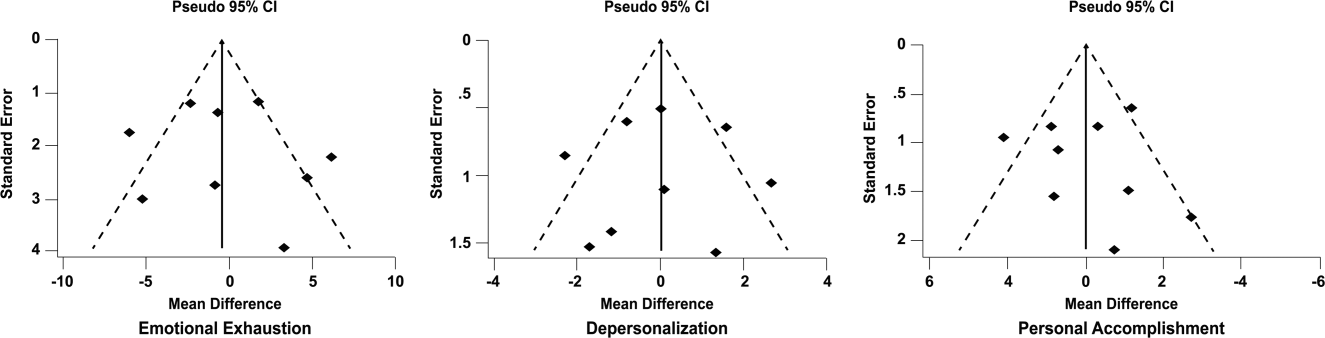

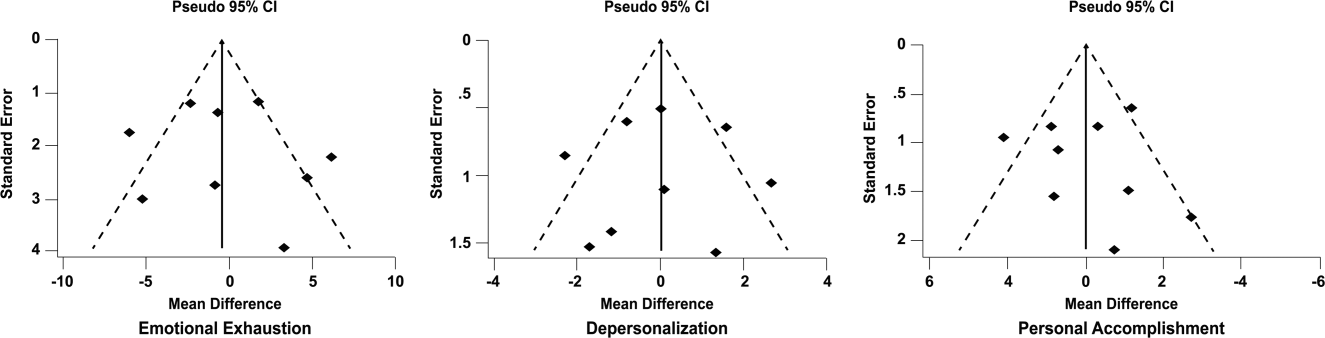

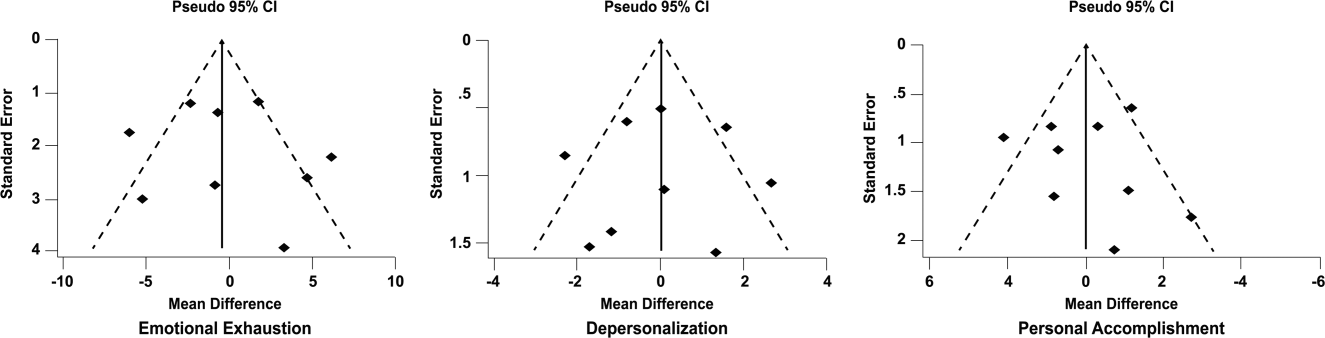

We examined the potential for publication bias in double‐armed studies by constructing a funnel plot, in which mean scores were plotted against their standard errors.[41] The trim‐and‐fill method was used to determine whether adjustment for publication bias was necessary. In addition, Begg's rank correlation test[42] was completed to test for statistically significant publication bias.

Stata 10.0 statistical software (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for data analyses. A P value of 0.05 or less was deemed statistically significant. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analysis checklist was used for the design and execution of the systematic review and meta‐analysis.[43]

Subgroup analyses based on location were undertaken a posteriori. All data (double‐armed meta‐analysis, meta‐regression of single‐armed studies, and meta‐regression of single‐ and double‐armed studies) were analyzed by location (United States vs other; United States vs Europe vs other).

RESULTS

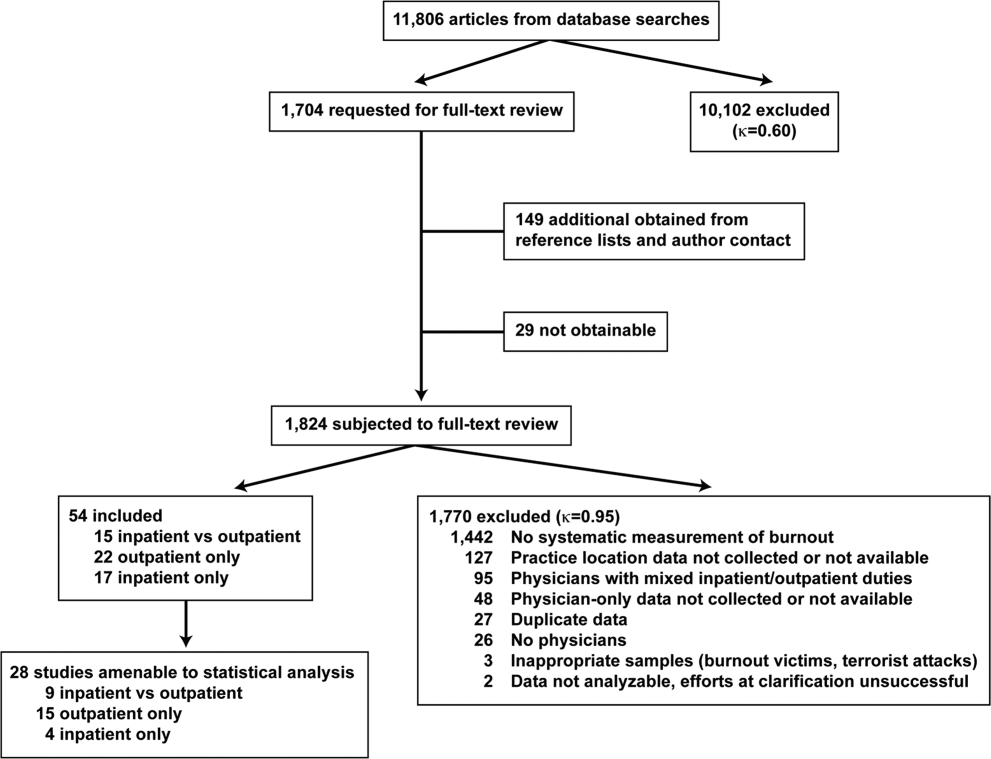

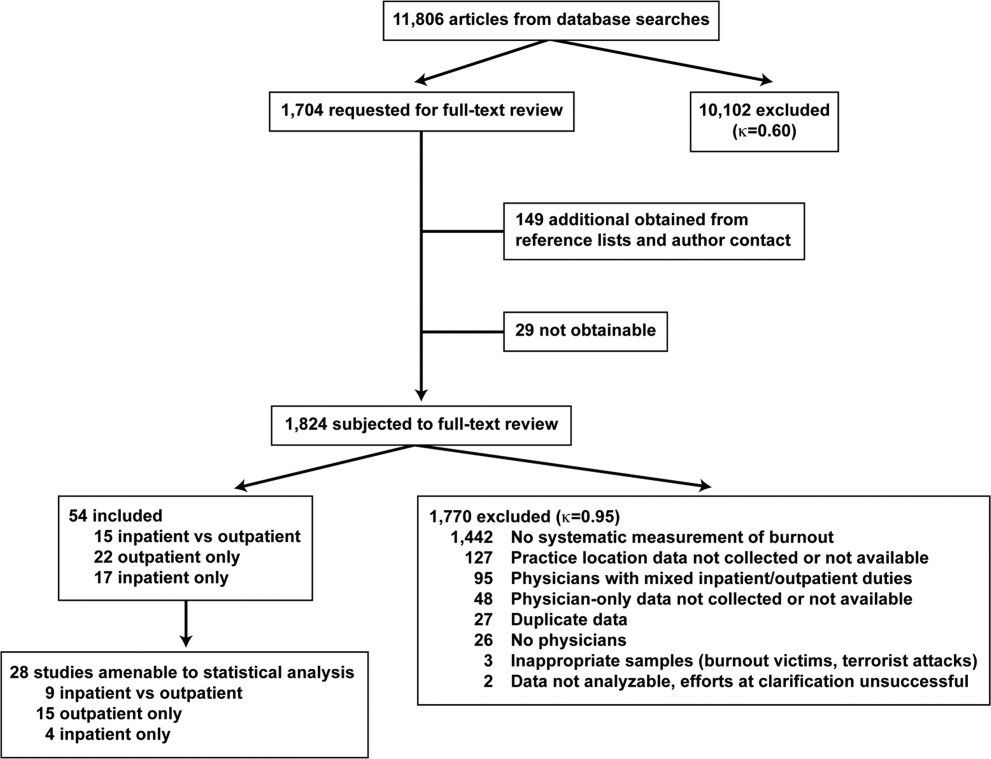

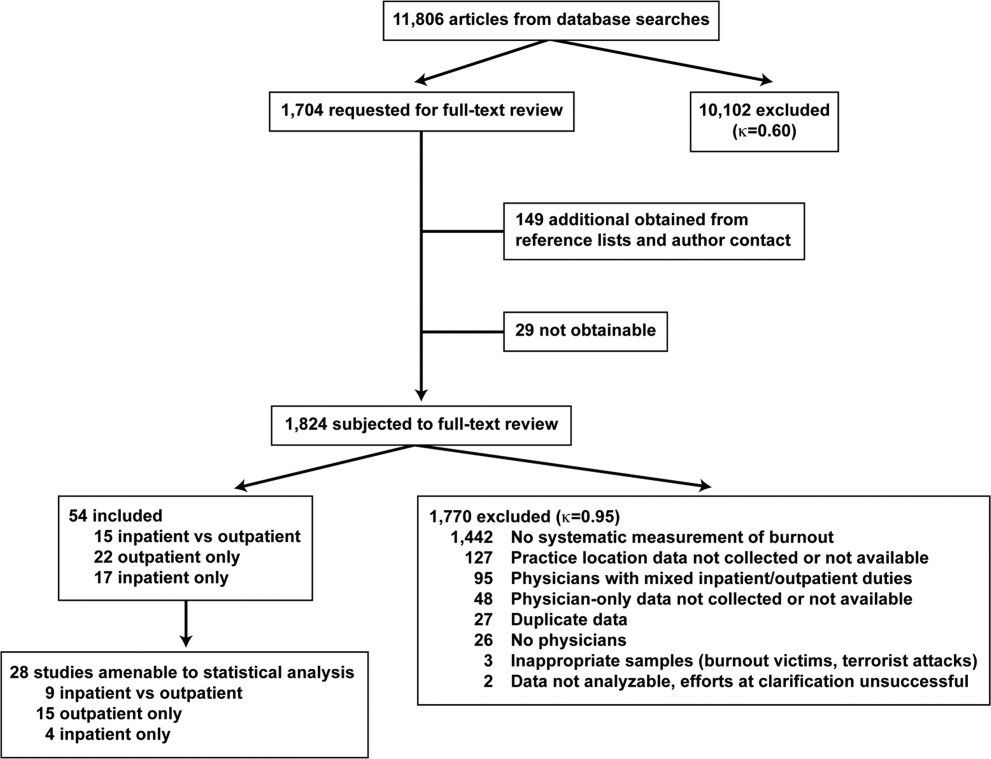

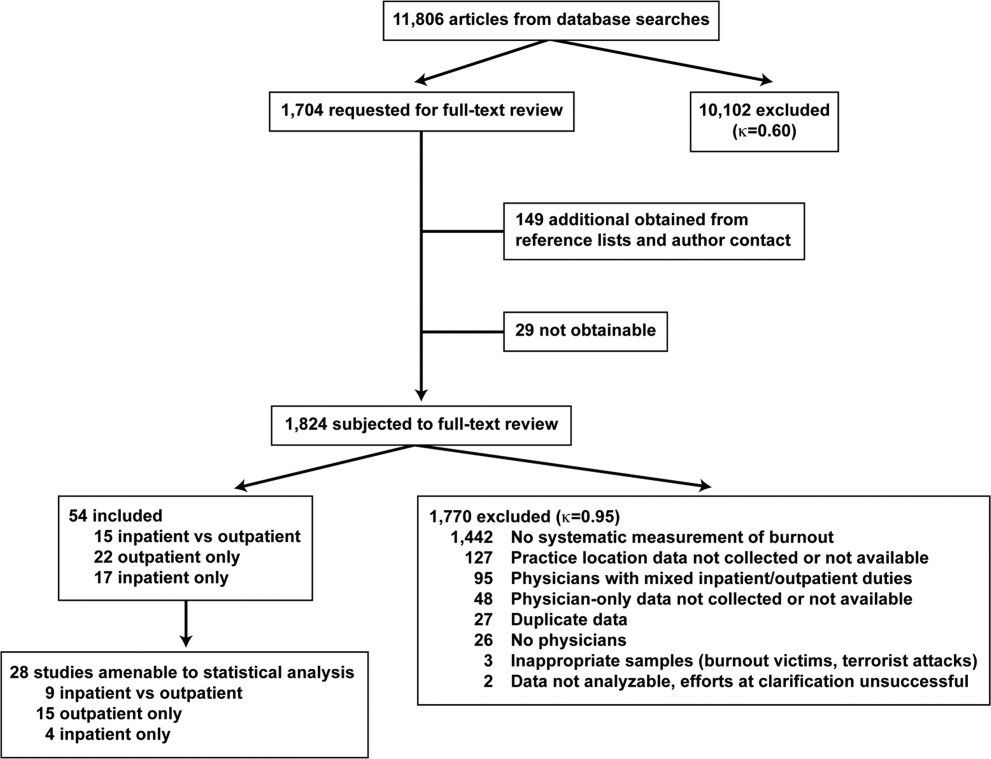

The search results are outlined in Figure 1. In total, 1704 articles met the criteria for full‐text review. A review of pertinent reference lists and author contacts led to the addition of 149 articles. Twenty‐nine references could not be located by any means, despite repeated attempts. Therefore, 1824 articles were subjected to full‐text review by the 2 investigators.

Initially, 57 articles were found that met criteria for inclusion. Of these, 2 articles reported data in formats that could not be interpreted.[44, 45] When efforts to clarify the data with the authors were unsuccessful, these studies were excluded. A study specifically designed to assess the response of physicians to a recent series of terrorist attacks[46] was excluded a posteriori because of lack of generalizability. Of the other 54 studies, 15 reported burnout data on both outpatient physicians and inpatient physicians, 22 reported data on outpatient physicians only, and 17 reported data on inpatient physicians only. Table 1 summarizes the results of the 37 studies involving outpatient physicians; Table 2 summarizes the 32 studies involving inpatient physicians.

| Lead Author, Publication Year | Study Population and Location | Instrument | No. of Participants | EE Score (SD)a | DP Score (SD) | PA Score (SD) | Other Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Schweitzer, 1994[12] | Young physicians of various specialties in South Africa | Single‐item survey | 7 | 6 (83%) endorsed burnout | |||

| Aasland, 1997 [54]b | General practitioners in Norway | Modified MBI (22 items; scale, 15) | 298 | 2.65 (0.80) | 1.90 (0.59) | 3.45 (0.40) | |

| Grassi, 2000 [58] | General practitioners in Italy | MBI | 182 | 18.49 (11.49) | 6.11 (5.86) | 38.52 (7.60) | |

| McManus, 2000 [59]b | General practitioners in United Kingdom | Modified MBI (9 items; scale, 06) | 800 | 8.34 (4.39) | 3.18 (3.40) | 14.16 (2.95) | |

| Yaman, 2002 [60] | General practitioners in 8 European nations | MBI | 98 | 25.1 (8.50) | 7.3 (4.92) | 34.5 (7.67) | |

| Cathbras, 2004 [61] | General practitioners in France | MBI | 306 | 21.85 (12.4) | 9.13 (6.7) | 38.7 (7.1) | |

| Goehring, 2005 [63] | General practitioners, general internists, pediatricians in Switzerland | MBI | 1755 | 17.9 (9.8) | 6.5 (4.7) | 39.6 (6.5) | |

| Esteva, 2006 [64] | General practitioners, pediatricians in Spain | MBI | 261 | 27.4 (11.8) | 10.07 (6.4) | 35.9 (7.06) | |

| Gandini, 2006 [65]b | Physicians of various specialties in Argentina | MBI | 67 | 31.0 (13.8) | 10.2 (6.6) | 38.4 (6.8) | |

| Ozyurt, 2006 [66] | General practitioners in Turkey | Modified MBI (22 items; scale, 04) | 55 | 15.23 (5.80) | 4.47 (3.31) | 23.38 (4.29) | |

| Deighton, 2007 [67]b | Psychiatrists in several German‐speaking nations | MBI | 19 | 30.68 (9.92) | 13.42 (4.23) | 37.16 (3.39) | |

| Dunwoodie, 2007 [68]b | Palliative care physicians in Australia | MBI | 21 | 14.95 (9.14) | 3.95 (3.40) | 38.90 (2.88) | |

| Srgaard, 2007 [69]b | Psychiatrists in 5 European nations | MBI | 22 | 19.41 (8.08) | 6.68 (4.93) | 39.00 (4.40) | |

| Sosa Oberlin, 2007 [56]b | Physicians of various specialties in Argentina | Author‐designed instrument | 33 | 26 (78.8%) had 4 burnout symptoms, 6.15 symptoms per physician | |||

| Voltmer, 2007 [57]b | Physicians of various specialties in Germany | AVEM | 46 | 11 (23.9%) exhibited burnout (type B) pattern | |||

| dm, 2008 [70]b | Physicians of various specialties in Hungary | MBI | 163 | 17.45 (11.12) | 4.86 (4.91) | 36.56 (7.03) | |

| Di Iorio, 2008 [71]b | Dialysis physicians in Italy | Author‐designed instrument | 54 | Work: 2.6 (1.5), Material: 3.1 (2.1), Climate: 3.0 (1.1), Objectives: 3.4 (1.6), Quality: 2.2 (1.5), Justification: 3.2 (2.0) | |||

| Lee, 2008 [49]b | Family physicians in Canada | MBI | 123 | 26.26 (9.53) | 10.20 (5.22) | 38.43 (7.34) | |

| Truchot, 2008 [72] | General practitioners in France | MBI | 259 | 25.4 (11.7) | 7.5 (5.5) | 36.5 (7.1) | |

| Twellaar, 2008 [73]b | General practitioners in the Netherlands | Utrecht Burnout Inventory | 349 | 2.06 (1.11) | 1.71 (1.05) | 5.08 (0.77) | |

| Arigoni, 2009 [17] | General practitioners, pediatricians in Switzerland | MBI | 258 | 22.8 (12.0) | 6.9 (6.1) | 39.0 (7.2) | |

| Bernhardt, 2009 [75] | Clinical geneticists in United States | MBI | 72 | 25.8 (10.01)c | 10.9 (4.16)c | 34.8 (5.43)c | |

| Bressi, 2009 [76]b | Psychiatrists in Italy | MBI | 53 | 23.15 (11.99) | 7.02 (6.29) | 36.41 (7.54) | |

| Krasner, 2009 [77] | General practitioners in United States | MBI | 60 | 26.8 (10.9)d | 8.4 (5.1)d | 40.2 (5.3)d | |

| Lasalvia, 2009 [55]b | Psychiatrists in Italy | Modified MBI (16 items; scale, 06) | 38 | 2.37 (1.27) | 1.51 (1.15) | 4.46 (0.87) | |

| Peisah, 2009 [79]b | Physicians of various specialties in Australia | MBI | 28 | 13.92 (9.24) | 3.66 (3.95) | 39.34 (8.55) | |

| Shanafelt, 2009 [80]b | Physicians of various specialties in United States | MBI | 408 | 20.5 (11.10) | 4.3 (4.74) | 40.8 (6.26) | |

| Zantinge, 2009 [81] | General practitioners in the Netherlands | Utrecht Burnout Inventory | 126 | 1.58 (0.79) | 1.32 (0.72) | 4.27 (0.77) | |

| Voltmer, 2010 [83]b | Psychiatrists in Germany | AVEM | 526 | 114 (21.7%) exhibited burnout (type B) pattern | |||

| Maccacaro, 2011 [85]b | Physicians of various specialties in Italy | MBI | 42 | 14.31 (11.98) | 3.62 (4.95) | 38.24 (6.22) | |

| Lucas, 2011 [84]b | Outpatient physicians periodically staffing an academic hospital teaching service in United States | MBI (EE only) | 30 | 24.37 (14.95) | |||

| Shanafelt, 2012 [87]b | General internists in United States | MBI | 447 | 25.4 (14.0) | 7.5 (6.3) | 41.4 (6.0) | |

| Kushnir, 2004 [62] | General practitioners and pediatricians in Israel | MBI (DP only) and SMBM | 309 | 9.15 (3.95) | SMBM mean (SD), 2.73 per item (0.86) | ||

| Vela‐Bueno, 2008 [74]b | General practitioners in Spain | MBI | 240 | 26.91 (11.61) | 9.20 (6.35) | 35.92 (7.92) | |

| Lesic, 2009 [78]b | General practitioners in Serbia | MBI | 38 | 24.71 (10.81) | 7.47 (5.51) | 37.21 (7.44) | |

| Demirci, 2010 [82]b | Medical specialists related to oncology practice in Hungary | MBI | 26 | 23.31 (11.2) | 6.46 (5.7) | 37.7 (8.14) | |

| Putnik, 2011 [86]b | General practitioners in Hungary | MBI | 370 | 22.22 (11.75) | 3.66 (4.40) | 41.40 (6.85) | |

| Lead Author, Publication Year | Study Population and Location | Instrument | No. of Participants | EE Score (SD)a | DP Score (SD) | PA Score (SD) | Other Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Varga, 1996 [88] | Hospital doctors in Spain | MBI | 179 | 21.61b | 7.33b | 35.28b | |

| Aasland, 1997 [54] | Hospital doctors in Norway | Modified MBI (22 items; scale, 15) | 582 | 2.39 (0.80) | 1.81 (0.65) | 3.51 (0.46) | |

| Bargellini, 2000 [89] | Hospital doctors in Italy | MBI | 51 | 17.45 (9.87) | 7.06 (5.54) | 35.33 (7.90) | |

| Grassi, 2000 [58] | Hospital doctors in Italy | MBI | 146 | 16.17 (9.64) | 5.32 (4.76) | 38.71 (7.28) | |

| Hoff, 2001 [33] | Hospitalists in United States | Single‐item surveyc | 393 | 12.9% burned out (>4/5), 24.9% at risk for burnout (34/5), 62.2% at no current risk (mean, 2.86 on 15 scale) | |||

| Trichard, 2005 [90] | Hospital doctors in France | MBI | 199 | 16 (10.7) | 6.6 (5.7) | 38.5 (6.5) | |

| Gandini, 2006 [65]d | Hospital doctors in Argentina | MBI | 290 | 25.0 (12.7) | 7.9 (6.2) | 40.1 (7.0) | |

| Dunwoodie, 2007 [68]d | Palliative care doctors in Australia | MBI | 14 | 18.29 (14.24) | 5.29 (5.89) | 38.86 (3.42) | |

| Srgaard, 2007 [69]d | Psychiatrists in 5 European nations | MBI | 18 | 18.56 (9.32) | 5.50 (3.79) | 39.08 (5.39) | |

| Sosa Oberlin, 2007 [56]d | Hospital doctors in Argentina | Author‐designed instrument | 3 | 3 (100%) had 4 burnout symptoms, 8.67 symptoms per physician | |||

| Voltmer, 2007 [57]d | Hospital doctors in Germany | AVEM | 271 | 77 (28.4%) exhibited burnout (type B) pattern | |||

| dm, 2008 [70]b | Physicians of various specialties in Hungary | MBI | 194 | 19.23 (10.79) | 4.88 (4.61) | 35.26 (8.42) | |

| Di Iorio, 2008 [71]d | Dialysis physicians in Italy | Author‐designed instrument | 62 | Work, mean (SD), 3.1 (1.4); Material, mean (SD), 3.3 (1.5); Climate, mean (SD), 2.9 (1.1); Objectives, mean (SD), 2.5 (1.5); Quality, mean (SD), 3.0 (1.1); Justification, mean (SD), 3.1 (2.1) | |||

| Fuss, 2008 [91]d | Hospital doctors in Germany | Copenhagen Burnout Inventory | 292 | Mean Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, mean (SD), 46.90 (18.45) | |||

| Marner, 2008 [92]d | Psychiatrists and 1 generalist in United States | MBI | 9 | 20.67 (9.75) | 7.78 (5.14) | 35.33 (6.44) | |

| Shehabi, 2008 [93]d | Intensivists in Australia | Modified MBI (6 items; scale, 15) | 86 | 2.85 (0.93) | 2.64 (0.85) | 2.58 (0.83) | |

| Bressi, 2009 [76]d | Psychiatrists in Italy | MBI | 28 | 17.89 (14.46) | 5.32 (7.01) | 34.57 (11.27) | |

| Brown, 2009 [94] | Hospital doctors in Australia | MBI | 12 | 22.25 (8.59) | 6.33 (2.71) | 39.83 (7.31) | |

| Lasalvia, 2009 [55]d | Psychiatrists in Italy | Modified MBI (16 items; scale, 06) | 21 | 1.95 (1.04) | 1.35 (0.85) | 4.46 (1.04) | |

| Peisah, 2009 [79]d | Hospital doctors in Australia | MBI | 62 | 20.09 (9.91) | 6.34 (4.90) | 35.06 (7.33) | |

| Shanafelt, 2009 [80]d | Hospitalists and intensivists in United States | MBI | 19 | 25.2 (11.59) | 4.4 (3.79) | 38.5 (8.04) | |

| Tunc, 2009 [95] | Hospital doctors in Turkey | Modified MBI (22 items; scale, 04) | 62 | 1.18 (0.78) | 0.81 (0.73) | 3.10 (0.59)e | |

| Cocco, 2010 [96]d | Hospital geriatricians in Italy | MBI | 38 | 16.21 (11.56) | 4.53 (4.63) | 39.13 (7.09) | |

| Doppia, 2011 [97]d | Hospital doctors in France | Copenhagen Burnout Inventory | 1,684 | Mean work‐related burnout score, 2.72 (0.75) | |||

| Glasheen, 2011 [98] | Hospitalists in United States | Single‐item survey | 265 | Mean, 2.08 on 15 scale 62 (23.4%) burned out | |||

| Lucas, 2011 [84]d | Academic hospitalists in United States | MBI (EE only) | 26 | 19.54 (12.85) | |||

| Thorsen, 2011 [99] | Hospital doctors in Malawi | MBI | 2 | 25.5 (4.95) | 8.5 (6.36) | 25.0 (5.66) | |

| Hinami, 2012 [50]d | Hospital doctors in United States | Single‐item survey | 793 | Mean, 2.24 on 15 scale 261 (27.2%) burned out | |||

| Quenot, 2012 [100]d | Intensivists in France | MBI | 4 | 33.25 (4.57) | 13.50 (5.45) | 35.25 (4.86) | |

| Ruitenburg, 2012 [101] | Hospital doctors in the Netherlands | MBI (EE and DP only) | 214 | 13.3 (8.0) | 4.5 (4.1) | ||

| Seibt, 2012 [102]d | Hospital doctors in Germany | Modified MBI (16 items; scale, 06, reported per item rather than totals) | 2,154 | 2.2 (1.4) | 1.4 (1.2) | 5.1 (0.9) | |

| Shanafelt, 2012 [87]d | Hospitalists in United States | MBI | 130 | 24.7 (12.5) | 9.1 (6.9) | 39.0 (7.6) | |

Table 3 summarizes the results of the 15 studies that reported burnout data for both inpatient and outpatient physicians, allowing direct comparisons to be made. Nine studies reported MBI subset totals with standard deviations, 2 used different modifications of the MBI, 2 used different author‐derived measures, 1 used only the emotional exhaustion subscale of the MBI, and 1 used the Arbeitsbezogenes Verhaltens und Erlebensmuster. Therefore, statistical comparison was attempted only for the 9 studies reporting comparable MBI data, comprising burnout data on 1390 outpatient physicians and 899 inpatient physicians.

| Lead Author, Publication Year | Location | Instrument | Inpatient‐Based Physicians | Outpatient‐Based Physicians | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Results, Score (SD)a | No. | Results, Score (SD)a | |||

| ||||||

| Aasland, 1997 [54]b | Norway | Modified MBI (22 items; scale, 15) | 582 | EE, 2.39 (0.80); DP, 1.81 (0.65); PA, 3.51 (0.46) | 298 | EE, 2.65 (0.80); DP, 1.90 (0.59); PA, 3.45 (0.40) |

| Grassi, 2000 [58] | Italy | MBI | 146 | EE, 16.17 (9.64); DP, 5.32 (4.76); PA, 38.71 (7.28) | 182 | EE, 18.49 (11.49); DP, 6.11 (5.86); PA, 38.52 (7.60) |

| Gandini, 2006 [65]b | Argentina | MBI | 290 | EE, 25.0 (12.7);DP, 7.9 (6.2); PA, 40.1 (7.0) | 67 | EE, 31.0 (13.8); DP, 10.2 (6.6); PA, 38.4 (6.8) |

| Dunwoodie, 2007 [68]b | Australia | MBI | 14 | EE, 18.29 (14.24); DP, 5.29 (5.89); PA, 38.86 (3.42) | 21 | EE, 14.95 (9.14); DP, 3.95 (3.40); PA, 38.90 (2.88) |

| Srgaard, 2007 [69]b | 5 European nations | MBI | 18 | EE, 18.56 (9.32); DP, 5.50 (3.79); PA, 39.08 (5.39) | 22 | EE, 19.41 (8.08); DP, 6.68 (4.93); PA, 39.00 (4.40) |

| Sosa Oberlin, 2007 [56]b | Argentina | Author‐designed instrument | 3 | 3 (100%) had 4 burnout symptoms, 8.67 symptoms per physician | 33 | 26 (78.8%) had 4 burnout symptoms, 6.15 symptoms per physician |

| Voltmer, 2007 [57]b | Germany | AVEM | 271 | 77 (28.4%) exhibited burnout (type B) pattern | 46 | 11 (23.9%) exhibited burnout (type B) pattern |

| dm, 2008 [70]b | Hungary | MBI | 194 | EE, 19.23 (10.79); DP, 4.88 (4.61); PA, 35.26 (8.42) | 163 | EE, 17.45 (11.12); DP, 4.86 (4.91); PA, 36.56 (7.03) |

| Di Iorio, 2008 [71]b | Italy | Author‐designed instrument | 62 | Work: 3.1 (1.4); material: 3.3 (1.5); climate: 2.9 (1.1); objectives: 2.5 (1.5); quality: 3.0 (1.1); justification: 3.1 (2.1) | 54 | Work: 2.6 (1.5); material: 3.1 (2.1); climate: 3.0 (1.1); objectives: 3.4 (1.6); quality: 2.2 (1.5); justification: 3.2 (2.0) |

| Bressi, 2009 [76]b | Italy | MBI | 28 | EE, 17.89 (14.46); DP, 5.32 (7.01); PA, 34.57 (11.27) | 53 | EE, 23.15 (11.99); DP, 7.02 (6.29); PA, 36.41 (7.54) |

| Lasalvia, 2009[55]b | Italy | Modified MBI (16 items; scale, 06) | 21 | EE, 1.95 (1.04); DP, 1.35 (0.85); PA, 4.46 (1.04) | 38 | EE, 2.37 (1.27); DP, 1.51 (1.15); PA, 4.46 (0.87) |

| Peisah, 2009 [79]b | Australia | MBI | 62 | EE, 20.09 (9.91); DP, 6.34 (4.90); PA, 35.06 (7.33) | 28 | EE, 13.92 (9.24); DP, 3.66 (3.95); PA, 39.34 (8.55) |

| Shanafelt, 2009 [80]b | United States | MBI | 19 | EE, 25.2 (11.59); DP, 4.4 (3.79); PA, 38.5 (8.04) | 408 | EE, 20.5 (11.10); DP, 4.3 (4.74); PA, 40.8 (6.26) |

| Lucas, 2011 [84]b | United States | MBI (EE only) | 26 | EE, 19.54 (12.85) | 30 | EE, 24.37 (14.95) |

| Shanafelt, 2012 [87]b | United States | MBI | 130 | EE, 24.7 (12.5); DP, 9.1 (6.9); PA, 39.0 (7.6) | 447 | EE, 25.4 (14.0); DP, 7.5 (6.3); PA, 41.4 (6.0) |

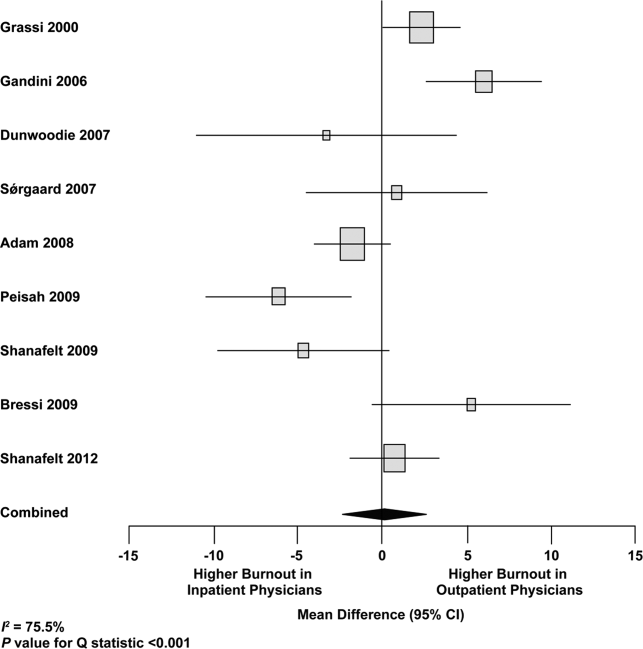

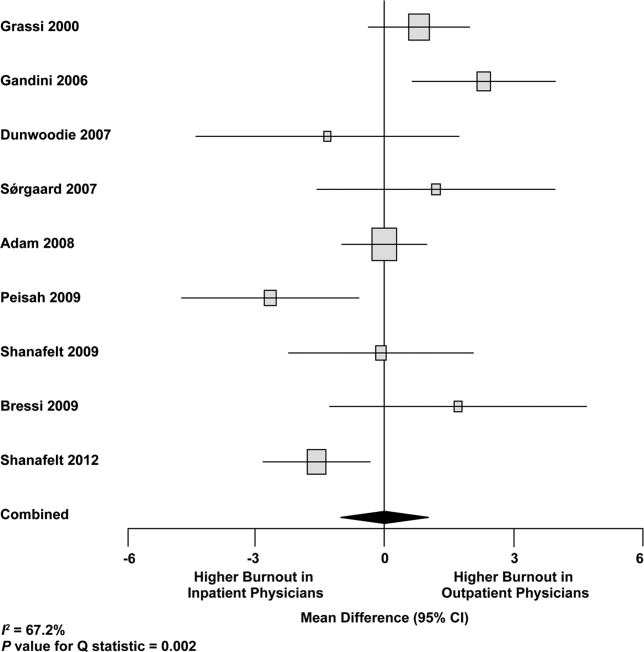

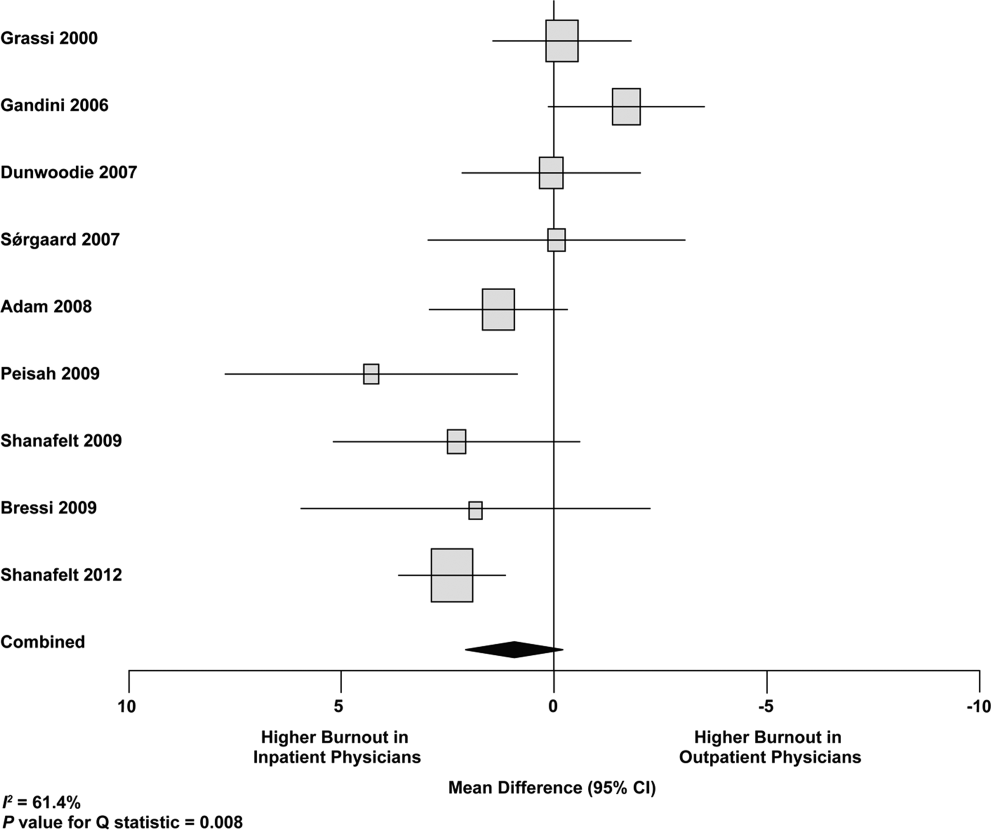

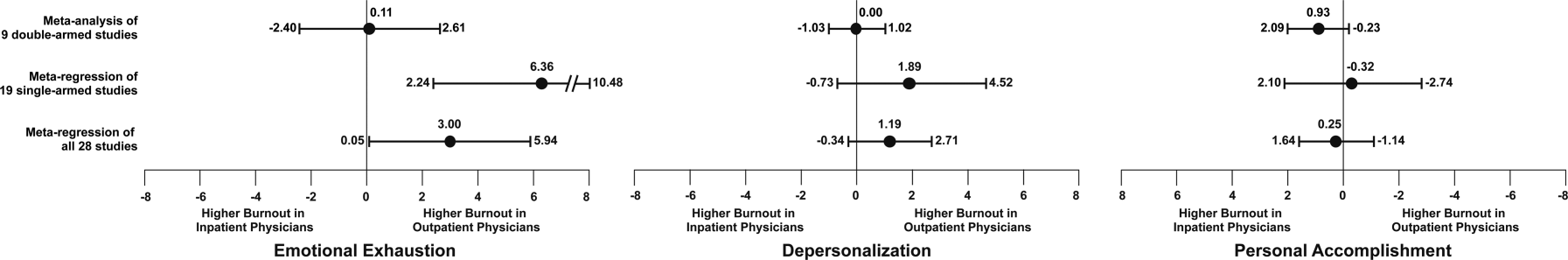

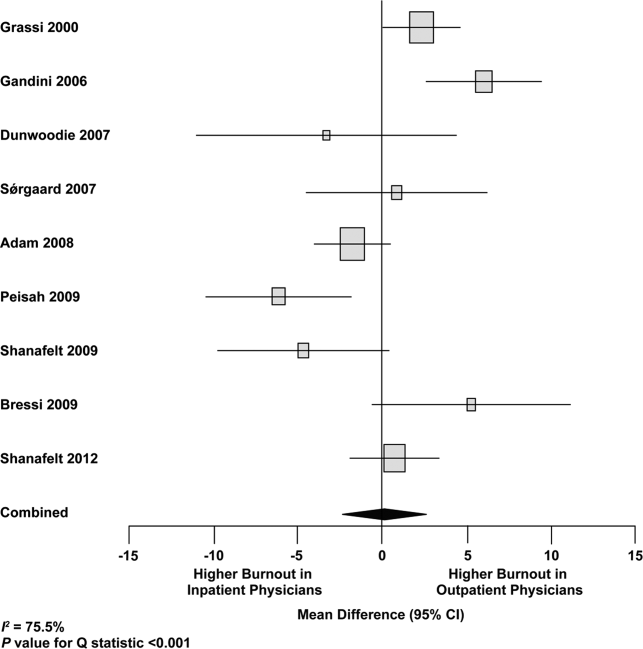

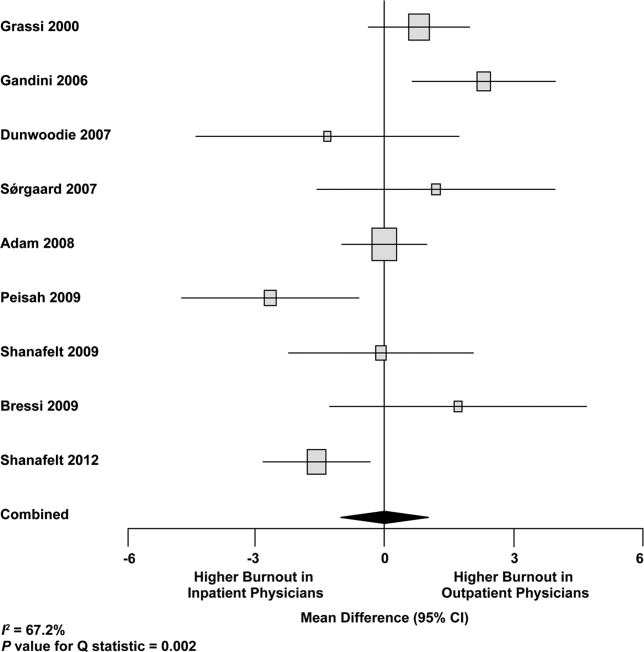

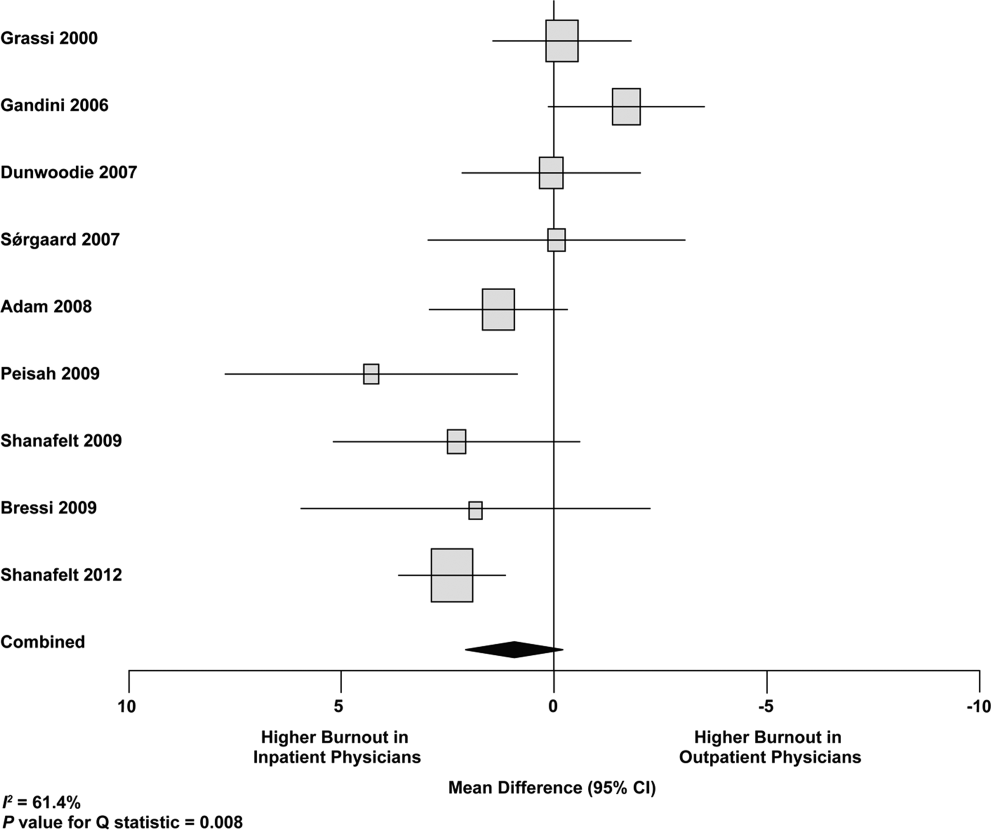

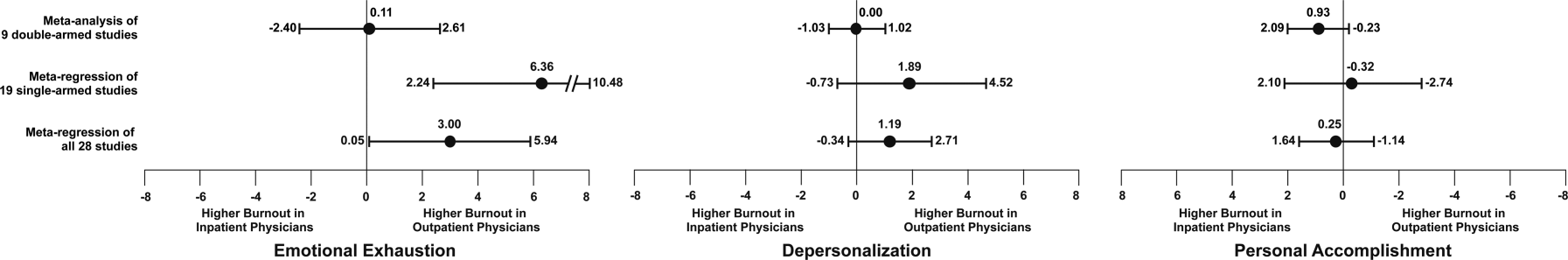

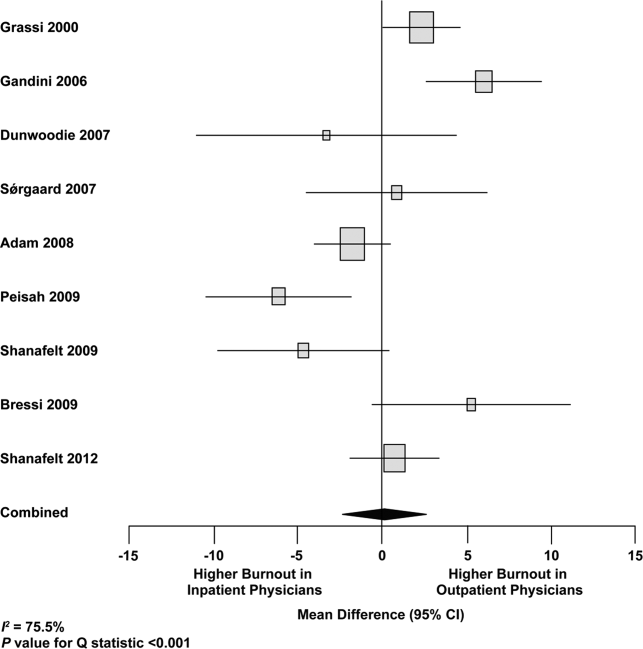

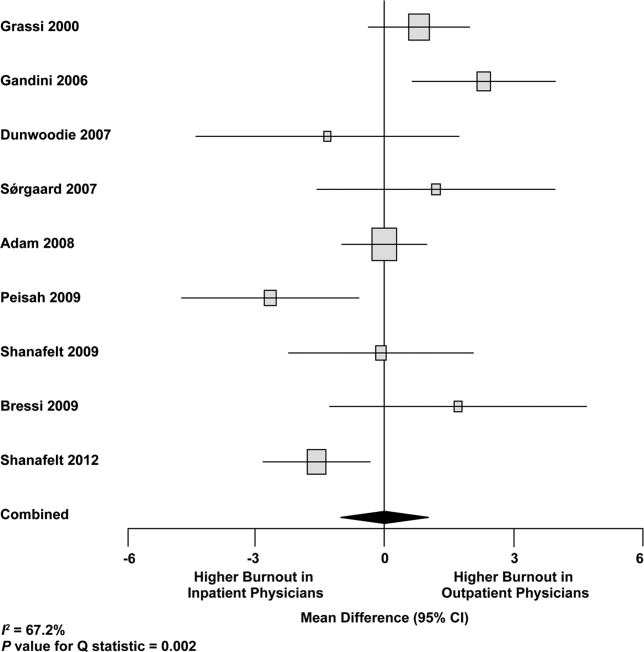

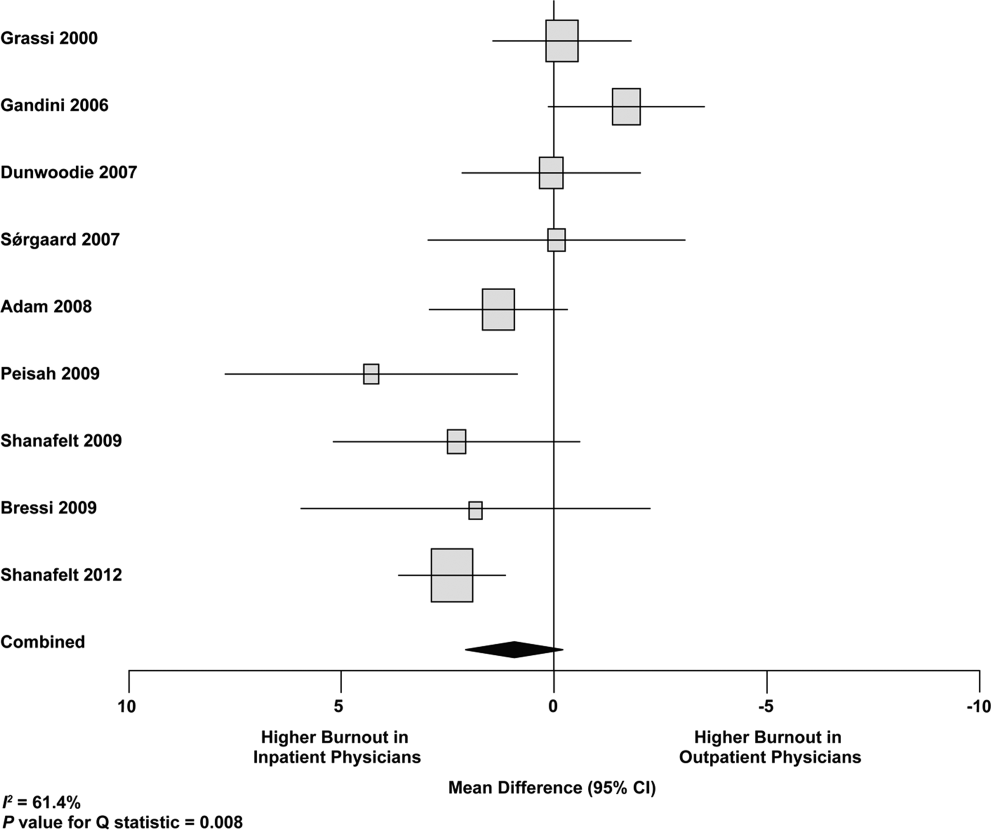

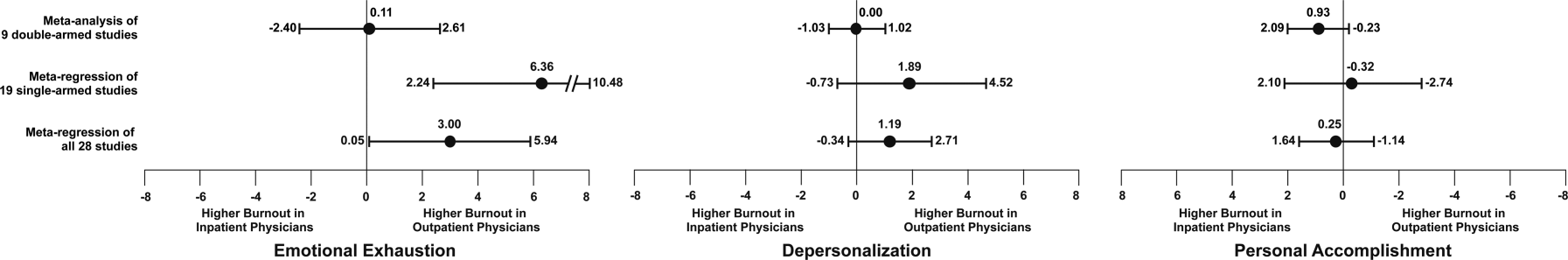

Figure 2 shows that no significant difference existed between the groups regarding emotional exhaustion (mean difference, 0.11 points on a 54‐point scale; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.40 to 2.61; P=0.94). In addition, there was no significant difference between the groups regarding depersonalization (Figure 3; mean difference, 0.00 points on a 30‐point scale; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.02; P=0.99) and personal accomplishment (Figure 4; mean difference, 0.93 points on a 48‐point scale; 95% CI, 0.23 to 2.09; P=0.11).

We used meta‐regression to allow the incorporation of single‐armed MBI studies. Whether single‐armed studies were analyzed separately (15 outpatient studies comprising 3927 physicians, 4 inpatient studies comprising 300 physicians) or analyzed with double‐armed studies (24 outpatient arms comprising 5318 physicians, 13 inpatient arms comprising 1301 physicians), the lack of a significant difference between the groups persisted for the depersonalization and personal accomplishment scales (Figure 5). Emotional exhaustion was significantly higher in outpatient physicians when single‐armed studies were considered separately (mean difference, 6.36 points; 95% CI, 2.24 to 10.48; P=0.002), and this difference persisted when all studies were combined (mean difference, 3.00 points; 95% CI, 0.05 to 5.94, P=0.046).

Subgroup analysis by geographic location showed US outpatient physicians had a significantly higher personal accomplishment score than US inpatient physicians (mean difference, 2.38 points; 95% CI, 1.22 to 3.55; P<0.001) in double‐armed studies. This difference did not persist when single‐armed studies were included through meta‐regression (mean difference, 0.55 points, 95% CI, 4.30 to 5.40, P=0.83).

Table 4 demonstrates that methodological quality was generally good from the standpoint of the reporting and bias subsections of the Downs and Black tool. External validity was scored lower for many studies due to the use of convenience samples and lack of information about physicians who declined to participate.

| Lead Author, Publication Year | Reporting | External Validity | Internal Validity: Bias | Internal Validity: Confounding | Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schweitzer, 1994 [12] | 5 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Varga, 1996 [88] | 5 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Aasland, 1997 [54] | 3 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Bargellini, 2000 [89] | 5 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Grassi, 2000 [58] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| McManus, 2000 [59] | 5 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Hoff, 2001 [33] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 2 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Yaman, 2002 [60] | 5 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Cathbras, 2004 [61] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Kushnir, 2004 [62] | 5 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Goehring, 2005 [63] | 6 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Trichard, 2005 [90] | 3 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Esteva, 2006 [64] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Gandini, 2006 [65] | 6 of 6 points | 1 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Ozyurt, 2006 [66] | 6 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Deighton, 2007 [67] | 5 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Dunwoodie, 2007 [68] | 5 of 6 points | 2 of 2 points | 4 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |

| Srgaard, 2007 [69] | 6 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 1 of 1 point | 1 of 1 point |

| Sosa Oberlin, 2007 [56] | 4 of 6 points | 0 of 2 points | 3 of 4 points | 0 of 1 point | 0 of 1 point |