User login

nPEP for HIV: Updated CDC guidelines available for primary care physicians

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided health care providers with updated recommendations for nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis (nPEP) with antiretroviral drugs to prevent transmission of HIV following sexual interaction, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposures.1 The new recommendations include the use of more effective and more tolerable drug regimens that employ antiretroviral medications that were approved since the previous guidelines came out in 2005; they also provide updated guidance on exposure assessment, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and longer-term prevention measures, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Screening for HIV infection has been expanding broadly in all health care settings over the past decade, so primary care physicians play an increasingly vital role in preventing HIV infection. Today, primary care physicians are also often the most likely “go-to” health care provider when patients think they may have been exposed to HIV. Clinically, this is an emergency situation, so time is of the essence: Treatment with three powerful antiretrovirals must be initiated within a few hours of – but no later than 72 hours after – an isolated exposure to blood, genital secretions, or other potentially infectious body fluids that may contain HIV.

The key issue for primary care physicians, especially those who have never prescribed PEP before, is advance planning. What you do up front, in terms of organizing materials and training staff, is worth the effort because there is so much at stake – for your patients and for society. The good news is that once you have an established nPEP protocol in place, it stays in place. When a patient asks for help, the protocol kicks in automatically.

Getting ready for nPEP

Prepare your staff:

- Educate your whole staff about the urgency of seeing potential nPEP patients immediately.

- Choose the staff person in your office who will submit requests for PEP medications to the pharmacy and/or pharmaceutical companies; your financial reimbursement staff person is likely a good candidate for this job.

- Learn about patient assistance programs (for uninsured or underinsured patients) and crime victims compensation programs (reimbursement or emergency awards for victims of violent crimes, including rape, for various out-of-pocket expenses including medical expenses).

Keep paperwork and materials on hand:

- Have information and forms for patient assistance programs for pharmaceutical companies supplying the drugs. Pharmaceutical companies are aware of the urgency for nPEP medications and are ready to respond immediately. They may mail the medication so it arrives the next day or, more likely, fax a voucher or other information for the patient to present to a local pharmacist who will fill the prescription.

- Have information on your state’s crime victims compensation program available.

- Consider keeping nPEP Starter Packs (with an initial 3-7 days’ worth of medication) readily available in your office.

Rapid evaluation of patients seeking care after potential exposure to HIV

Effective delivery of nPEP requires prompt initial evaluation of patients and assessment of HIV transmission risk. Take a methodical, step-by-step history of the exposure to address the following basic questions:

- Date and time of exposure? nPEP should be initiated as soon as possible after HIV exposure; it is unlikely to be effective if not initiated within 72 hours or less.

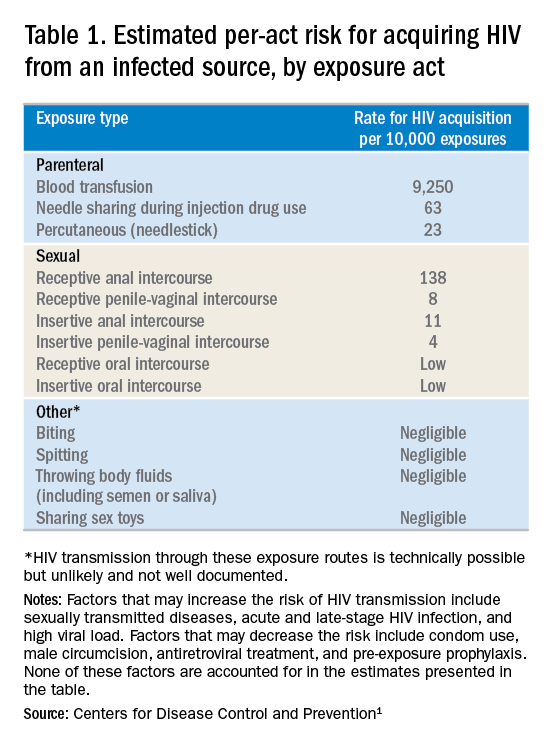

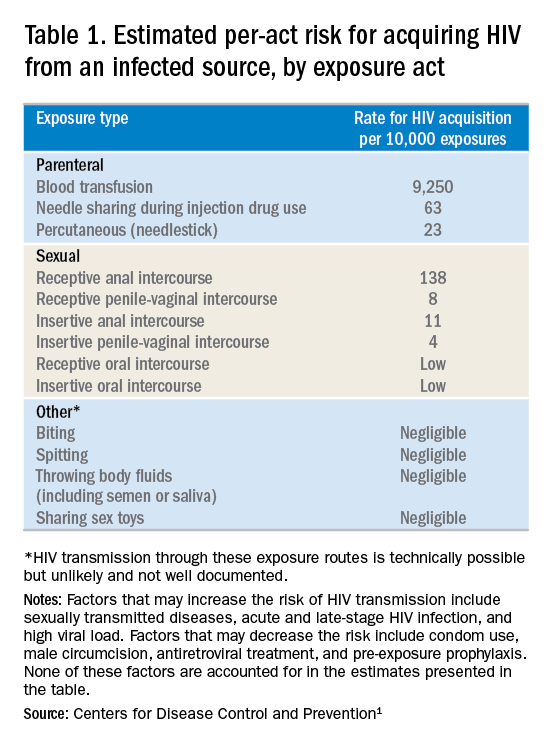

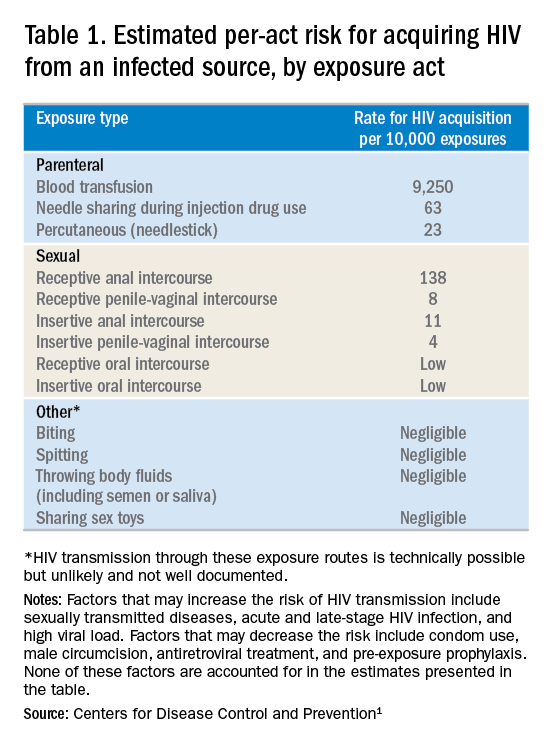

- Frequency of exposure? Type/route of exposure? nPEP is generally reserved for isolated or infrequent exposures that present a substantial risk for HIV acquisition (see Table 1 on HIV acquisition risk below).

- HIV status of exposure source? If the source is positive, is the source person on HIV treatment with antiretroviral therapy? If unknown, is the source person an injecting drug user or a man who has sex with men (MSM)?

Based on the initial evaluation, is nPEP recommended?

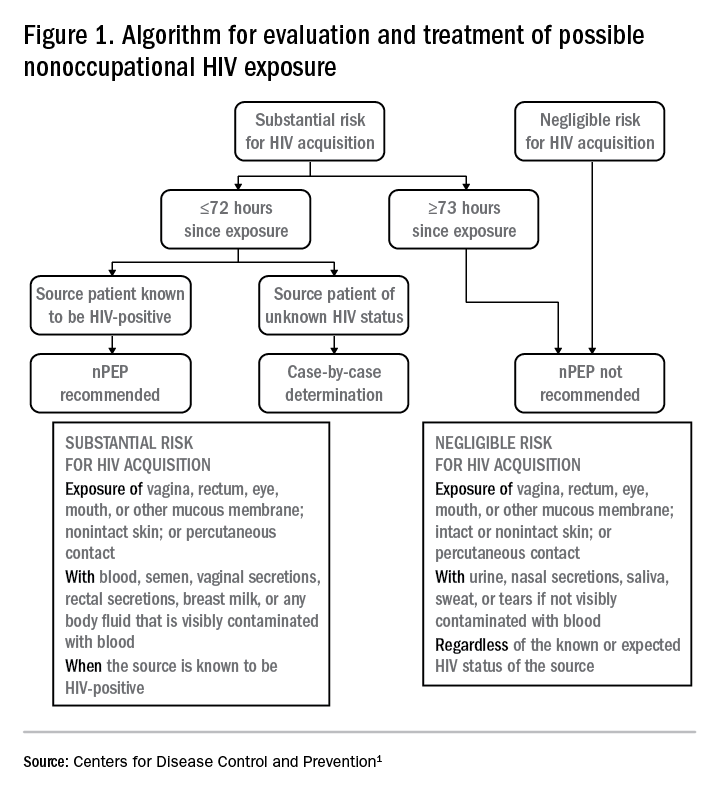

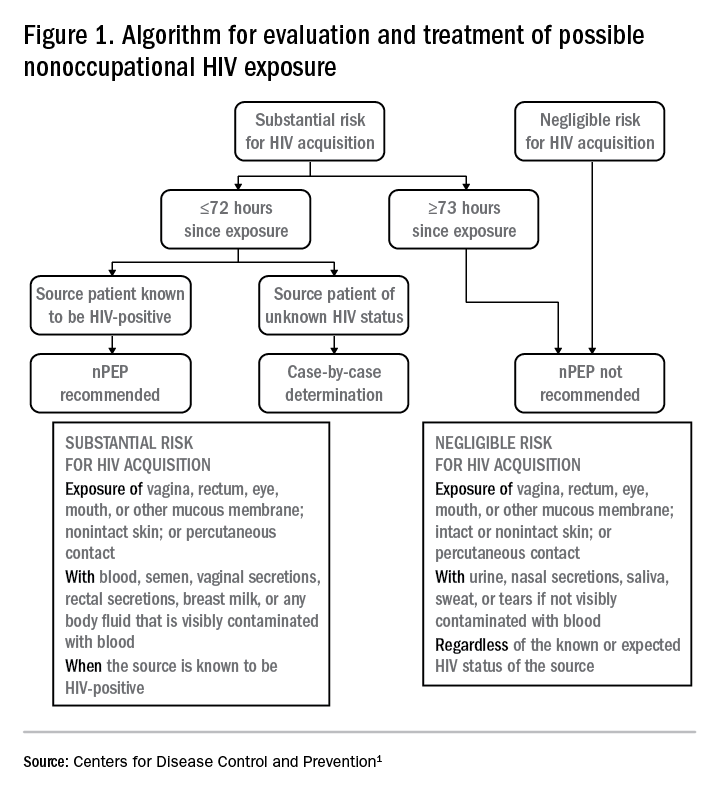

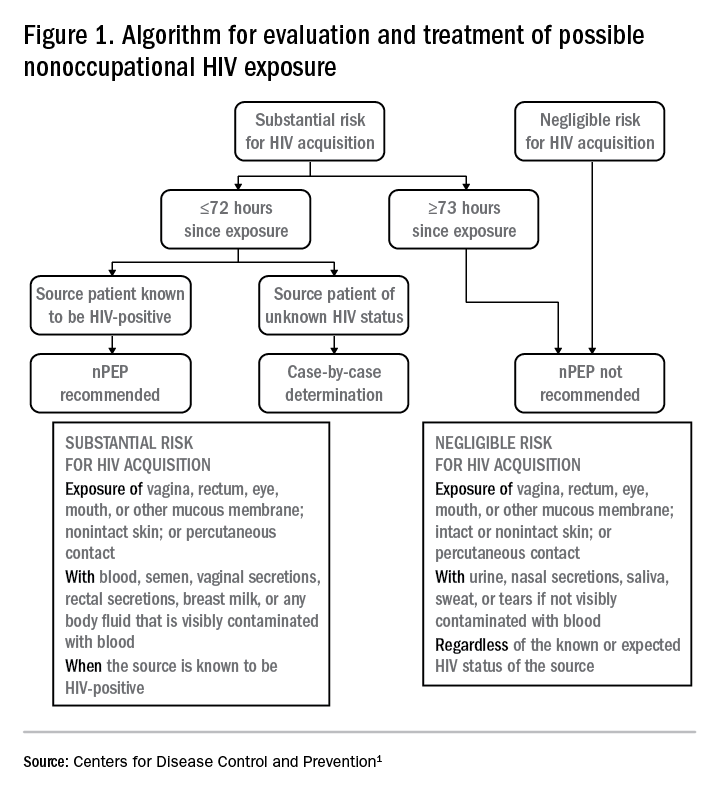

Answers to the questions asked during the initial evaluation of the patient will determine whether nPEP is indicated. Along with its updated recommendations, the CDC provided an algorithm to help guide evaluation and treatment.

Preferred HIV test

Administer an HIV test to all patients considered for nPEP, preferably the rapid combined antigen and antibody test (Ag/Ab), or just the antibody test if the Ag/Ab test is not available. nPEP is indicated only for persons without HIV infections. However, if results are not available during the initial evaluation, assume the patient is not infected. If indicated and started, nPEP can be discontinued if tests later shown the patient already has an HIV infection.

Laboratory testing

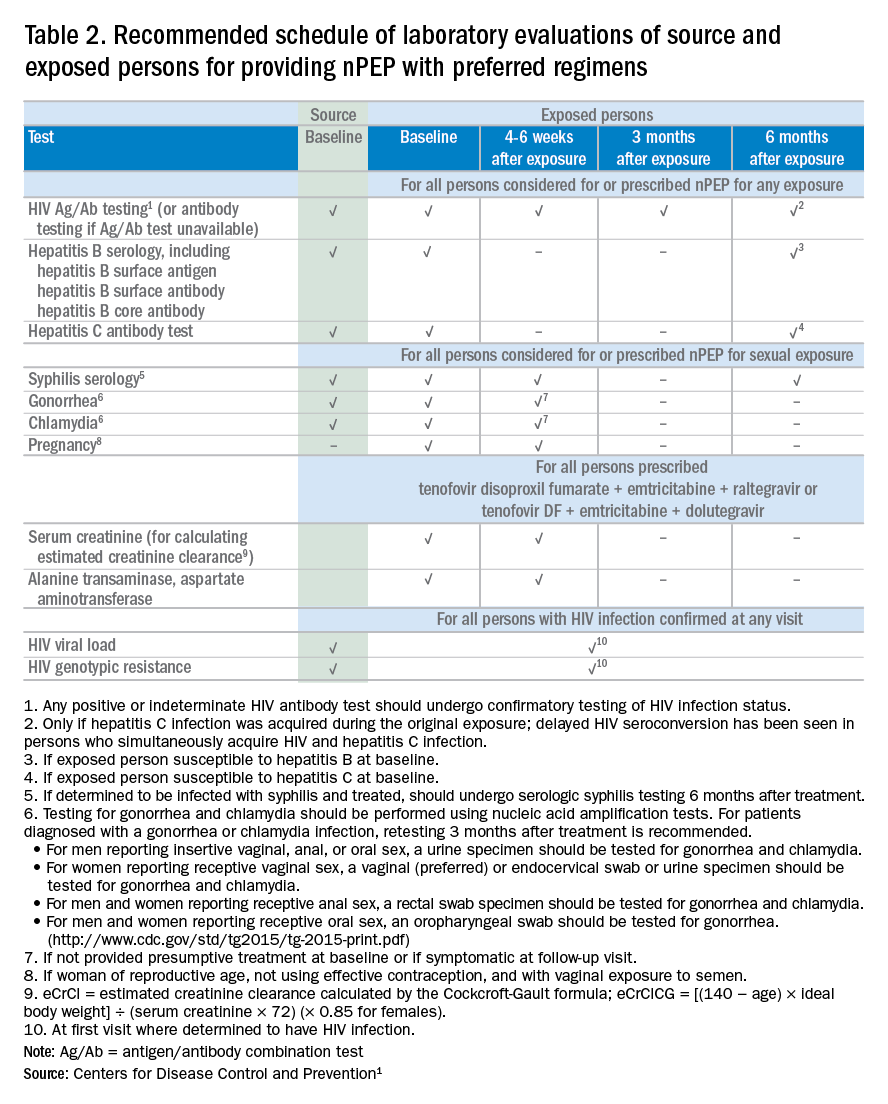

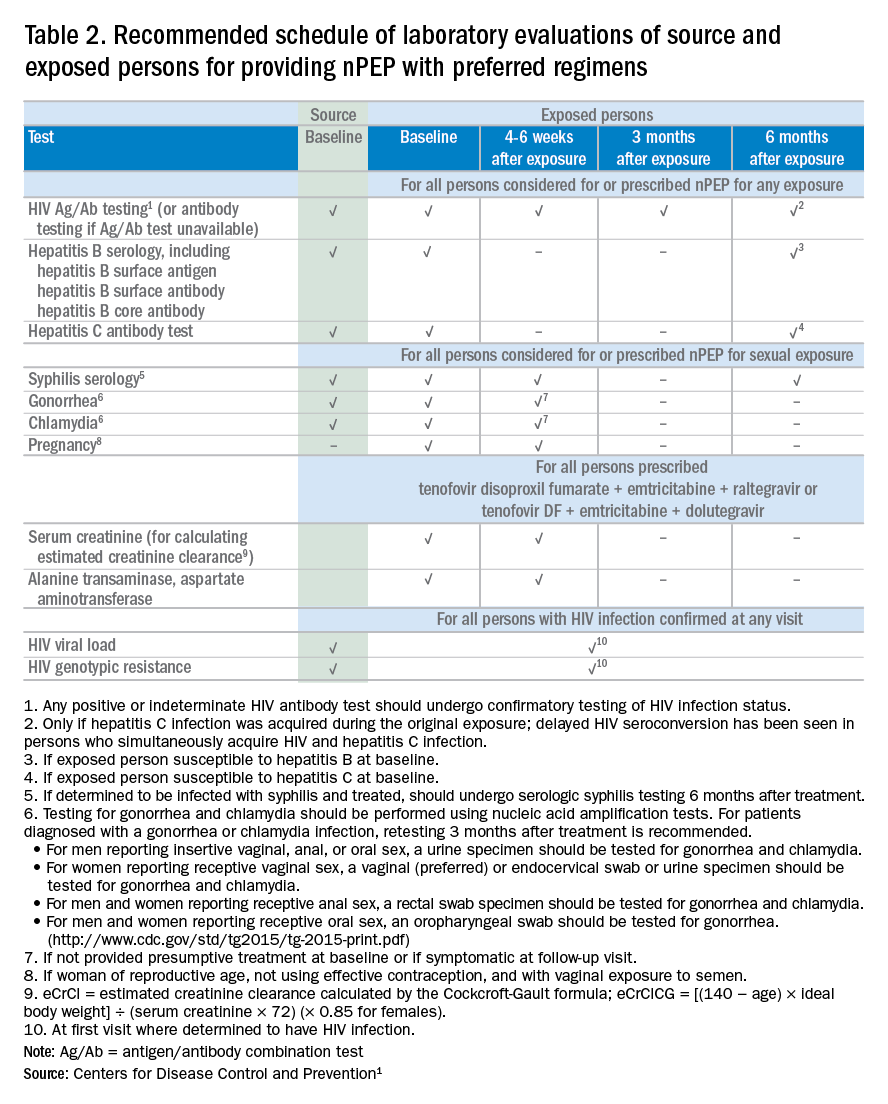

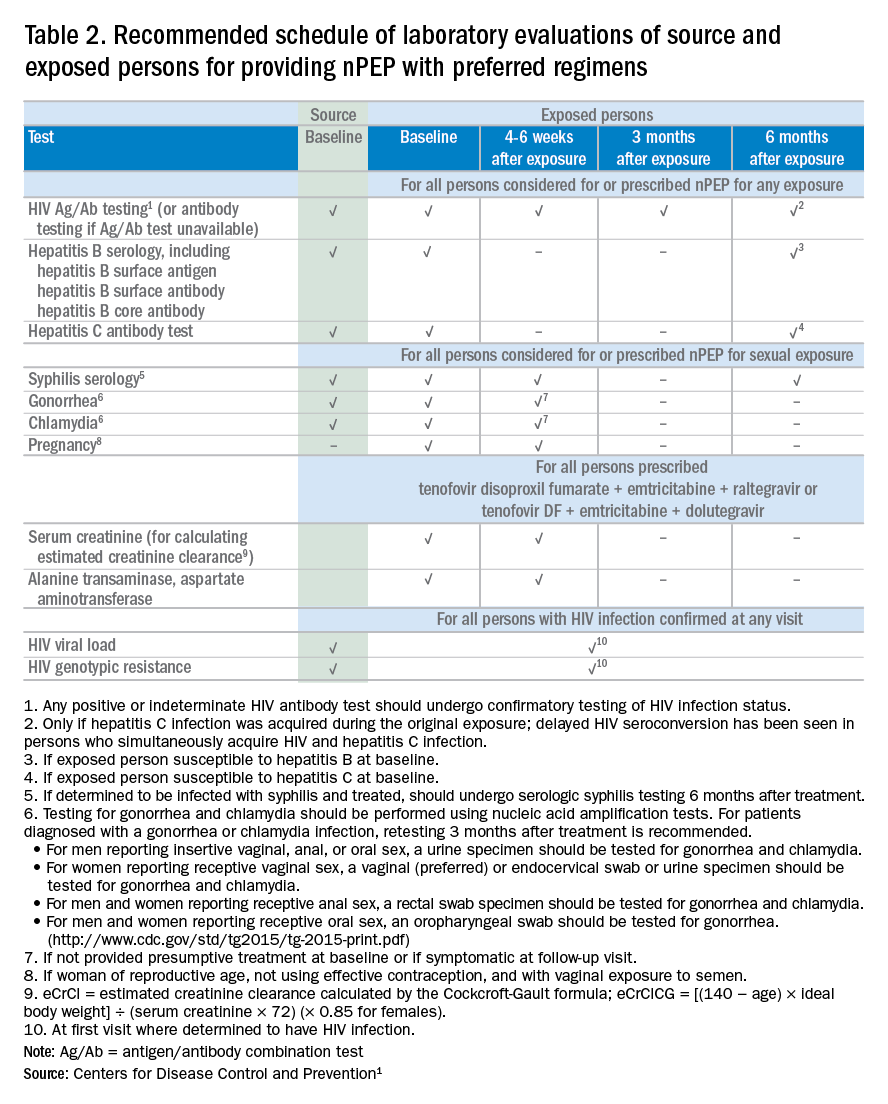

If nPEP is indicated, conduct laboratory testing. Lab testing is required to document the patient’s HIV status (and that of the source person, when available), identify and manage other conditions potentially resulting from exposure, identify conditions that may affect the nPEP medication regimen, and monitor safety or toxicities to the prescribed regimen.

nPEP treatment regimen for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents

In the absence of randomized clinical trials, data from a case/control study demonstrating an 81% reduction of HIV transmission after use of occupational PEP among hospital workers remains the strongest evidence for the benefit of nPEP.1,2 For patients offered nPEP, recommended treatment includes prescribing either of the following regimens for 28 days:

- Preferred regimen: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (300 mg) with emtricitabine (FTC) (200 mg) once daily plus either raltegravir (RAL) 400 mg twice daily or dolutegravir (DTG) 50 mg daily.

- Alternative regimen: TDF (300 mg) with FTC (200 mg) once daily plus darunavir (DRV) (800 mg) and ritonavir (RTV) (100 mg) once daily.

Additional considerations and nPEP treatment regimens for children, patients with decreased renal function, and pregnant women are included in the CDC guidelines.

Crucial Information for Patients on nPEP

Emphasize the importance of proper dosing and adherence.

Review the patient information for each drug in the regimen, specifically the black boxes, warnings, and side effects, and counsel your patients accordingly.

Transitioning from nPEP to PrEP or from PrEP to nPEP

If you have a patient who engages in behavior that places them at risk for frequent, recurrent exposures to HIV, consider transitioning them to PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) following their 28-day course of nPEP.3 PrEP is a two-drug regimen taken daily on an ongoing basis.

Additionally, for patients who are already on PrEP but who have not taken their medications within a week before the possible exposure, consider initiating nPEP for 28 days and then reintroducing PrEP if their HIV status is negative and the problems with adherence can be addressed moving forward.

Raising Awareness About nPEP

Many people never expect to be exposed to HIV and may not know about the availability of PEP in an emergency situation. You can help raise awareness by making educational materials available in your waiting rooms and exam rooms. Brochures and other HIV/AIDS educational materials for patients are available from the CDC Act Against AIDS campaign.

Summary

Dr. Dominguez is a Captain, U.S. Public Health Service, epidemiology branch, division of HIV/AIDS prevention, CDC.

Additional resources

- The CDC recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested for HIV at least once as part of routine health care. As part of its Act Against AIDS initiative, the CDC developed the HIV Screening Standard Care program, which provides free tools and resources to help clinicians and nurses incorporate routine HIV screening into primary care settings.

- HIV guidelines and recommendations .

- Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP)

- Pre-Exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV. United States, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2017.

2. Cardo DM et al. New Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-90.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States–2014: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed March 6, 2017.

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided health care providers with updated recommendations for nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis (nPEP) with antiretroviral drugs to prevent transmission of HIV following sexual interaction, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposures.1 The new recommendations include the use of more effective and more tolerable drug regimens that employ antiretroviral medications that were approved since the previous guidelines came out in 2005; they also provide updated guidance on exposure assessment, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and longer-term prevention measures, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Screening for HIV infection has been expanding broadly in all health care settings over the past decade, so primary care physicians play an increasingly vital role in preventing HIV infection. Today, primary care physicians are also often the most likely “go-to” health care provider when patients think they may have been exposed to HIV. Clinically, this is an emergency situation, so time is of the essence: Treatment with three powerful antiretrovirals must be initiated within a few hours of – but no later than 72 hours after – an isolated exposure to blood, genital secretions, or other potentially infectious body fluids that may contain HIV.

The key issue for primary care physicians, especially those who have never prescribed PEP before, is advance planning. What you do up front, in terms of organizing materials and training staff, is worth the effort because there is so much at stake – for your patients and for society. The good news is that once you have an established nPEP protocol in place, it stays in place. When a patient asks for help, the protocol kicks in automatically.

Getting ready for nPEP

Prepare your staff:

- Educate your whole staff about the urgency of seeing potential nPEP patients immediately.

- Choose the staff person in your office who will submit requests for PEP medications to the pharmacy and/or pharmaceutical companies; your financial reimbursement staff person is likely a good candidate for this job.

- Learn about patient assistance programs (for uninsured or underinsured patients) and crime victims compensation programs (reimbursement or emergency awards for victims of violent crimes, including rape, for various out-of-pocket expenses including medical expenses).

Keep paperwork and materials on hand:

- Have information and forms for patient assistance programs for pharmaceutical companies supplying the drugs. Pharmaceutical companies are aware of the urgency for nPEP medications and are ready to respond immediately. They may mail the medication so it arrives the next day or, more likely, fax a voucher or other information for the patient to present to a local pharmacist who will fill the prescription.

- Have information on your state’s crime victims compensation program available.

- Consider keeping nPEP Starter Packs (with an initial 3-7 days’ worth of medication) readily available in your office.

Rapid evaluation of patients seeking care after potential exposure to HIV

Effective delivery of nPEP requires prompt initial evaluation of patients and assessment of HIV transmission risk. Take a methodical, step-by-step history of the exposure to address the following basic questions:

- Date and time of exposure? nPEP should be initiated as soon as possible after HIV exposure; it is unlikely to be effective if not initiated within 72 hours or less.

- Frequency of exposure? Type/route of exposure? nPEP is generally reserved for isolated or infrequent exposures that present a substantial risk for HIV acquisition (see Table 1 on HIV acquisition risk below).

- HIV status of exposure source? If the source is positive, is the source person on HIV treatment with antiretroviral therapy? If unknown, is the source person an injecting drug user or a man who has sex with men (MSM)?

Based on the initial evaluation, is nPEP recommended?

Answers to the questions asked during the initial evaluation of the patient will determine whether nPEP is indicated. Along with its updated recommendations, the CDC provided an algorithm to help guide evaluation and treatment.

Preferred HIV test

Administer an HIV test to all patients considered for nPEP, preferably the rapid combined antigen and antibody test (Ag/Ab), or just the antibody test if the Ag/Ab test is not available. nPEP is indicated only for persons without HIV infections. However, if results are not available during the initial evaluation, assume the patient is not infected. If indicated and started, nPEP can be discontinued if tests later shown the patient already has an HIV infection.

Laboratory testing

If nPEP is indicated, conduct laboratory testing. Lab testing is required to document the patient’s HIV status (and that of the source person, when available), identify and manage other conditions potentially resulting from exposure, identify conditions that may affect the nPEP medication regimen, and monitor safety or toxicities to the prescribed regimen.

nPEP treatment regimen for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents

In the absence of randomized clinical trials, data from a case/control study demonstrating an 81% reduction of HIV transmission after use of occupational PEP among hospital workers remains the strongest evidence for the benefit of nPEP.1,2 For patients offered nPEP, recommended treatment includes prescribing either of the following regimens for 28 days:

- Preferred regimen: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (300 mg) with emtricitabine (FTC) (200 mg) once daily plus either raltegravir (RAL) 400 mg twice daily or dolutegravir (DTG) 50 mg daily.

- Alternative regimen: TDF (300 mg) with FTC (200 mg) once daily plus darunavir (DRV) (800 mg) and ritonavir (RTV) (100 mg) once daily.

Additional considerations and nPEP treatment regimens for children, patients with decreased renal function, and pregnant women are included in the CDC guidelines.

Crucial Information for Patients on nPEP

Emphasize the importance of proper dosing and adherence.

Review the patient information for each drug in the regimen, specifically the black boxes, warnings, and side effects, and counsel your patients accordingly.

Transitioning from nPEP to PrEP or from PrEP to nPEP

If you have a patient who engages in behavior that places them at risk for frequent, recurrent exposures to HIV, consider transitioning them to PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) following their 28-day course of nPEP.3 PrEP is a two-drug regimen taken daily on an ongoing basis.

Additionally, for patients who are already on PrEP but who have not taken their medications within a week before the possible exposure, consider initiating nPEP for 28 days and then reintroducing PrEP if their HIV status is negative and the problems with adherence can be addressed moving forward.

Raising Awareness About nPEP

Many people never expect to be exposed to HIV and may not know about the availability of PEP in an emergency situation. You can help raise awareness by making educational materials available in your waiting rooms and exam rooms. Brochures and other HIV/AIDS educational materials for patients are available from the CDC Act Against AIDS campaign.

Summary

Dr. Dominguez is a Captain, U.S. Public Health Service, epidemiology branch, division of HIV/AIDS prevention, CDC.

Additional resources

- The CDC recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested for HIV at least once as part of routine health care. As part of its Act Against AIDS initiative, the CDC developed the HIV Screening Standard Care program, which provides free tools and resources to help clinicians and nurses incorporate routine HIV screening into primary care settings.

- HIV guidelines and recommendations .

- Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP)

- Pre-Exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV. United States, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2017.

2. Cardo DM et al. New Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-90.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States–2014: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed March 6, 2017.

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided health care providers with updated recommendations for nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis (nPEP) with antiretroviral drugs to prevent transmission of HIV following sexual interaction, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposures.1 The new recommendations include the use of more effective and more tolerable drug regimens that employ antiretroviral medications that were approved since the previous guidelines came out in 2005; they also provide updated guidance on exposure assessment, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and longer-term prevention measures, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Screening for HIV infection has been expanding broadly in all health care settings over the past decade, so primary care physicians play an increasingly vital role in preventing HIV infection. Today, primary care physicians are also often the most likely “go-to” health care provider when patients think they may have been exposed to HIV. Clinically, this is an emergency situation, so time is of the essence: Treatment with three powerful antiretrovirals must be initiated within a few hours of – but no later than 72 hours after – an isolated exposure to blood, genital secretions, or other potentially infectious body fluids that may contain HIV.

The key issue for primary care physicians, especially those who have never prescribed PEP before, is advance planning. What you do up front, in terms of organizing materials and training staff, is worth the effort because there is so much at stake – for your patients and for society. The good news is that once you have an established nPEP protocol in place, it stays in place. When a patient asks for help, the protocol kicks in automatically.

Getting ready for nPEP

Prepare your staff:

- Educate your whole staff about the urgency of seeing potential nPEP patients immediately.

- Choose the staff person in your office who will submit requests for PEP medications to the pharmacy and/or pharmaceutical companies; your financial reimbursement staff person is likely a good candidate for this job.

- Learn about patient assistance programs (for uninsured or underinsured patients) and crime victims compensation programs (reimbursement or emergency awards for victims of violent crimes, including rape, for various out-of-pocket expenses including medical expenses).

Keep paperwork and materials on hand:

- Have information and forms for patient assistance programs for pharmaceutical companies supplying the drugs. Pharmaceutical companies are aware of the urgency for nPEP medications and are ready to respond immediately. They may mail the medication so it arrives the next day or, more likely, fax a voucher or other information for the patient to present to a local pharmacist who will fill the prescription.

- Have information on your state’s crime victims compensation program available.

- Consider keeping nPEP Starter Packs (with an initial 3-7 days’ worth of medication) readily available in your office.

Rapid evaluation of patients seeking care after potential exposure to HIV

Effective delivery of nPEP requires prompt initial evaluation of patients and assessment of HIV transmission risk. Take a methodical, step-by-step history of the exposure to address the following basic questions:

- Date and time of exposure? nPEP should be initiated as soon as possible after HIV exposure; it is unlikely to be effective if not initiated within 72 hours or less.

- Frequency of exposure? Type/route of exposure? nPEP is generally reserved for isolated or infrequent exposures that present a substantial risk for HIV acquisition (see Table 1 on HIV acquisition risk below).

- HIV status of exposure source? If the source is positive, is the source person on HIV treatment with antiretroviral therapy? If unknown, is the source person an injecting drug user or a man who has sex with men (MSM)?

Based on the initial evaluation, is nPEP recommended?

Answers to the questions asked during the initial evaluation of the patient will determine whether nPEP is indicated. Along with its updated recommendations, the CDC provided an algorithm to help guide evaluation and treatment.

Preferred HIV test

Administer an HIV test to all patients considered for nPEP, preferably the rapid combined antigen and antibody test (Ag/Ab), or just the antibody test if the Ag/Ab test is not available. nPEP is indicated only for persons without HIV infections. However, if results are not available during the initial evaluation, assume the patient is not infected. If indicated and started, nPEP can be discontinued if tests later shown the patient already has an HIV infection.

Laboratory testing

If nPEP is indicated, conduct laboratory testing. Lab testing is required to document the patient’s HIV status (and that of the source person, when available), identify and manage other conditions potentially resulting from exposure, identify conditions that may affect the nPEP medication regimen, and monitor safety or toxicities to the prescribed regimen.

nPEP treatment regimen for otherwise healthy adults and adolescents

In the absence of randomized clinical trials, data from a case/control study demonstrating an 81% reduction of HIV transmission after use of occupational PEP among hospital workers remains the strongest evidence for the benefit of nPEP.1,2 For patients offered nPEP, recommended treatment includes prescribing either of the following regimens for 28 days:

- Preferred regimen: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) (300 mg) with emtricitabine (FTC) (200 mg) once daily plus either raltegravir (RAL) 400 mg twice daily or dolutegravir (DTG) 50 mg daily.

- Alternative regimen: TDF (300 mg) with FTC (200 mg) once daily plus darunavir (DRV) (800 mg) and ritonavir (RTV) (100 mg) once daily.

Additional considerations and nPEP treatment regimens for children, patients with decreased renal function, and pregnant women are included in the CDC guidelines.

Crucial Information for Patients on nPEP

Emphasize the importance of proper dosing and adherence.

Review the patient information for each drug in the regimen, specifically the black boxes, warnings, and side effects, and counsel your patients accordingly.

Transitioning from nPEP to PrEP or from PrEP to nPEP

If you have a patient who engages in behavior that places them at risk for frequent, recurrent exposures to HIV, consider transitioning them to PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) following their 28-day course of nPEP.3 PrEP is a two-drug regimen taken daily on an ongoing basis.

Additionally, for patients who are already on PrEP but who have not taken their medications within a week before the possible exposure, consider initiating nPEP for 28 days and then reintroducing PrEP if their HIV status is negative and the problems with adherence can be addressed moving forward.

Raising Awareness About nPEP

Many people never expect to be exposed to HIV and may not know about the availability of PEP in an emergency situation. You can help raise awareness by making educational materials available in your waiting rooms and exam rooms. Brochures and other HIV/AIDS educational materials for patients are available from the CDC Act Against AIDS campaign.

Summary

Dr. Dominguez is a Captain, U.S. Public Health Service, epidemiology branch, division of HIV/AIDS prevention, CDC.

Additional resources

- The CDC recommends that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 get tested for HIV at least once as part of routine health care. As part of its Act Against AIDS initiative, the CDC developed the HIV Screening Standard Care program, which provides free tools and resources to help clinicians and nurses incorporate routine HIV screening into primary care settings.

- HIV guidelines and recommendations .

- Postexposure prophylaxis (PEP)

- Pre-Exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV. United States, 2016. Accessed March 6, 2017.

2. Cardo DM et al. New Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1485-90.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States–2014: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed March 6, 2017.