User login

A Real Welcome Home: Permanent Housing for Homeless Veterans

Mr. G is a 67-year-old veteran. During the Vietnam War, he had the “most dangerous job”: helicopter door gunner and mechanic. He served in multiple combat missions and was under constant threat of attack. On returning to the U.S., he experienced anger outbursts, nightmares, hypervigilance, and urges to engage in dangerous behavior, such as driving a motorcycle more than 100 mph. Then he began abusing alcohol and drugs. Mr. G’s behavior and substance abuse eventually led to strained family relationships, termination from a high-paying job, and homelessness.

In 2001, the Washington DC VAMC homeless and substance abuse staff provided outreach and services that helped him secure permanent subsidized housing, achieve and maintain sobriety, get treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and get full-time employment. Mr. G has maintained permanent supported housing status for 9 years, regained a sense of purpose, remained drug- and alcohol-free since 2001, attended a Vietnam combat PTSD support group weekly, and been an exemplary employee for 8 years.

In 2009, on any given night in the U.S., more than 75,000 veterans were without a permanent home and living on the streets, as Mr. G had been.1 Nearly 150,000 other veterans were spending the night in an emergency shelter or transitional housing. In early 2010, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) developed a strategic plan to align federal resources toward 4 key objectives, which included preventing and ending homelessness among veterans. Since then, the most dramatic reductions in homelessness have occurred among veterans, with an overall 33% decline in chronic homelessness nationwide.

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), permanent housing is defined as community-based housing without a designated length of stay in which formerly homeless individuals live as independently as possible.2 Under permanent housing, a program participant must be the tenant on a lease for at least 1 year, and the lease is renewable and terminable only for cause. The federal definition of the chronically homeless is a person who is homeless and lives in a place not meant for human habitation, in a safe haven, or in an emergency shelter continuously for at least 1 year; or on at least 4 separate occasions within the past 3 years; and who can be diagnosed with ≥ 1 of the following conditions: substance use disorder, serious mental illness, developmental disability as defined in section 102 of the Developmental Disabilities Assistance Bill of Rights Act of 2000 (42 U.S.C. 15002), PTSD, cognitive impairments caused by brain injury, and chronic physical illness or disability.3

Ending homelessness makes sense from a variety of perspectives. From a moral perspective, no one should experience homelessness, but this is especially true for the men and women who have served in the U.S. military. From a health care and resources perspective, homelessness is associated with poorer medical outcomes; higher medical costs for emergency department visits and hospital admissions; longer stays (often for conditions that could be treated in ambulatory settings); and increased mortality.4-7 From a societal perspective, homelessness is associated with costs for shelters and other forms of temporary housing and with higher justice system costs stemming from police, court, and jail involvement.8 The higher justice system costs are in part attributable to significantly longer incarcerations for homeless persons than for demographically similar inmates who have been similarly charged but have housing.9 According to recent studies, significant cost reductions have been achieved by addressing homelessness and providing permanent housing, particularly for the chronically homeless with mental illness.10-14

This article describes the efforts that have been made, through collaborations and coalitions of government and community partners, to identify and address risk factors for homelessness in Washington, DC—and ultimately to end veteran homelessness in the nation’s capitol.

Historic Perspective on Veteran Homelessness

Although the problem was first described after the Revolutionary War and again after the Civil War, homelessness among U.S. veterans has only recently been academically studied. During the colonial period, men often were promised pensions or land grants in exchange for military service. Several states failed to deliver on these promises, throwing veterans into dire financial circumstances and leaving them homeless. By the end of the Civil War, the size of the veteran population (almost 2 million, counting only those who fought for the Union), combined with an unemployment rate of 40% and economic downturns, led to thousands of veterans becoming homeless.15,16

Homelessness among veterans continued after World War I. In 1932, more than 15,000 homeless and disabled “Bonus Army,” World War I veterans, marched on Washington to demand payment of the financial benefits promised for their military service.

Although World War II and Korean War veterans did not experience homelessness as previous veterans had, the problem resurfaced after Vietnam—the combat veterans of that war were overrepresented among the homeless.17,18 Those at highest risk ranged from age 35 to 44 years in the early years of the all-volunteer military. It has been suggested that their increased risk may reflect social selection—volunteers for military service came from poor economic backgrounds with fewer social supports.19 A more recent study found that 3.8% of more than 300,000 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans who were followed for 5 years after military discharge experienced a homeless episode.20 Female veterans similarly are overrepresented among the homeless.21 Female veterans represent only 1% of the overall female population, yet 3% to 4% are homeless.

Homelessness has always been a social problem, but only during the 1970s and 1980s did homelessness increase in importance—the number of visibly homeless people rose during that period—and investigators began to study and address the issue. Experts have described several factors that contributed to the increase in homelessness during that time.22,23 First, as part of the deinstitutionalization initiative, thousands of mentally ill persons were released from state mental hospitals without a plan in place for affordable or supervised housing. Second, single-room-occupancy dwellings in poor areas, where transient single men lived, were demolished, and affordable housing options decreased. Third, economic and social changes were factors, such as a decreased need for seasonal and unskilled labor; reduced likelihood that relatives will take in homeless family members; and decriminalized public intoxication, loitering, and vagrancy. Out of these conditions came an interest in studying the causes of and risk factors for veteran homelessness and in developing a multipronged approach to end veteran homelessness.

Demographics

Nationally, veterans account for 9% of the homeless population.24 Predominantly, they are single men living in urban areas—only about 9% are women—and 43% served during the Vietnam era.24 Among homeless veterans, minorities are overrepresented—45% are African American or Hispanic, as contrasted with 10% and 3%, respectively, of the general population. More than two-thirds served in the military for more than 3 years, and 76% have a history of mental illness or substance abuse. Compared with the general homeless population, homeless veterans are older, better educated, more likely to have been married, and more likely to have health insurance, primarily through the VA.24,25

The Washington, DC, metropolitan area encompasses the District of Columbia, northern Virginia, the tricounty area of southern Maryland, and Montgomery and Prince George’s counties in Maryland. Demographics for veterans in this area vary somewhat from national figures. According to the 2015 Point-in-Time survey of the homeless, veterans accounted for 5% of the homeless population (less than the national percentage). Most homeless veterans were single men (11.6% were women) and African American (65% of single adults, 85% of adults in families). Forty-five percent reported being employed and 40% had a substance use disorder or a serious mental illness. A large proportion also had at least 1 physical disability, such as hypertension, hepatitis, arthritis, diabetes mellitus, or heart disease.26

Risk Factors

Multiple studies and multivariate analyses have determined that veteran status is associated with an increased risk for homelessness for both male and female veterans.27 Female veterans were 3 times and male veterans 2 times more likely than nonveterans to become homeless, even when poverty, age, race, and geographic variation were controlled. A recent systematic review of U.S. veterans found that the strongest and most consistent risk factors for homelessness were substance use disorders and mental illness, particularly psychotic disorders. Posttraumatic stress disorder was not more significant than other mental conditions but it was a risk factor. Low income, unemployment, and poor money management were also factors.

Social risk factors include lack of support from family and friends. Military service with multiple deployments, transfers, and on-base housing may contribute to interruption of social support and lead to social isolation, thus increasing veterans’ risk for homelessness. Some studies have found that veterans are more likely to report physical injury or medical problems as contributing to homelessness and more likely to have 2 or more chronic medical conditions. Last, history of incarceration and adverse childhood experiences (eg, behavioral problems, family instability, foster care, childhood abuse) also have been found to be risk factors for homelessness among veterans and nonveterans alike.

Understanding these risk factors is an important step in addressing homelessness. Homelessness prevention efforts can screen for these risk factors and then intervene as quickly as possible. Access to mental health and substance abuse services, employment assistance, disability benefits and other income supports, and social services may prevent initial and subsequent episodes of homelessness. The VA, as the largest integrated health system in the U.S., is a critical safety net for low-income and disabled veterans with complex psychosocial needs. One study found access to VA service-connected pensions was protective against homelessness.28

Addressing Homelessness

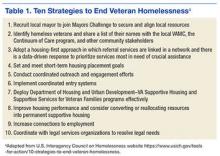

There are 10 USICH-recommended strategies for ending veteran homelessness (Table 1). These strategies cannot be achieved by any single federal agency or exclusively by government agencies—they require multipronged approaches and private and public partnerships. In early 2011, the staff of the Washington DC VAMC homeless program identified a single point of contact who would regularly meet with each Continuum of Care local planning body and each Public Housing Authority (PHA). This contact could identify homeless veterans regardless of the agency from which they were requesting assistance. The contact also facilitated identification of specific bottleneck issues contributing to delays in housing veterans. One such issue was that veterans were filling out application forms by themselves, and in some cases, their information was incomplete, or supporting documents (eg, government-issued IDs) were missing. The VA team adjusted the procedures to better meet veterans’ needs. Now veterans identified as meeting requirements for housing assistance are enrolled in classes in which a caseworker reviews their completed applications to ensure they are complete and supporting documents included. If an ID is needed, the caseworker facilitates the process and then submits the veteran’s application to the local PHA for processing. The result has been no returned applications.

Another issue was that in some cases a veteran spoke with the PHA and indicated interest in an apartment and only later found out that the apartment failed inspection. There would then be back-and-forth communications between PHA and landlord to have repairs made so the unit could pass inspection, which often resulted in long delays. The solution was to have a stock of preinspected housing options. The Washington DC VAMC homeless program now has a housing specialist who identifies preinspected units and can expedite the lease to a veteran. In addition, the homeless program in partnership with the PHA now sets up regular meet-and-greet events for landlords and veterans so veterans can preview available rentals.

Housing-First Model

The homeless program readily adopted the housing-first model. This model focuses on helping individuals and families access housing as quickly as possible and remain permanently housed; this assistance is not time-limited but ongoing. After housing placement, the client can choose from an array of both time-limited and long-term services, which are individualized to promote housing stability and individual well-being. Most important, housing is not contingent on compliance with services. Instead, participants must comply with a standard lease agreement and are provided the services and support that can help them do so successfully. Services are determined by completing needs assessments. In addition, as a veteran is applying for housing, a caseworker actively uses motivational interviewing techniques to enhance the likelihood that the veteran will accept services.

Providing Core Service to Veterans

In 2012, the Washington DC VAMC opened the Community Resource and Referral Center (CRRC) as a one-stop shop for homeless and at-risk veterans in need of basic, core, wraparound services through the VA. Basic services include showers, laundry facilities, and a chapel. The CRRC has onsite psychiatric services that can engage veterans in mental health and substance abuse treatment. There is also an onsite primary care team who specialize in working with the homeless and can address any acute or chronic medical problems. For veterans who want to return to employment, there is an onsite Compensated Work Therapy program, which has uniquely partnered with the VAMC as well as community partners (eg, National Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Quantico National Cemetery, Arlington National Cemetery) to offer therapeutic job experiences that often lead to gainful full-time employment.

Veterans can use an onsite computer lab to complete resumes and apply for employment online, with the assistance of veteran peer specialists and vocational rehabilitation specialists. For veterans who are unable to work, the homeless program team assists with disability applications. Social Security, Veterans Benefits Administration representatives, and Legal Aid have office hours at the CRRC to provide one-stop shopping for veterans. Additional community partnerships have led to classes to help veterans manage income effectively, and veterans are assisted with completing tax returns.

Representatives from the Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) and Health Care for Re-entry Veterans (HCRV) programs are also onsite. The VJO program provides outreach, assessment, and case management for justice-involved veterans to prevent unnecessary criminalization of mental illness and extended incarceration. A VJO program specialist works with courts, legal representatives, and jails and acts as a liaison to engage veterans in treatment and prevent incarcerations through jail diversion strategies. The HCRV program assists incarcerated veterans with reentry into the community through outreach and prerelease assessments, and referrals and links to medical, psychiatric, and social services, including employment services on release. This program also can provide short-term case management assistance on release.

In 2013, to further the implementation of the USICH strategies in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area, 12 local government and nonprofit agencies entered into the Veterans NOW coalition (Table 2). This collaboration enabled development of a coordinated effort to identify all area veterans experiencing homelessness, regardless of which agency the veterans contacted. Further, this team set up processes to assess veterans’ housing and service needs and to match each veteran to the most appropriate housing resource. There was consensus regarding use of the Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool (SPDAT) as the evidence-informed approach for prioritizing client needs and identifying areas in which support is most likely needed to prevent housing instability.29 More than 50 staff members at 20 different agencies in the District of Columbia have now been trained and are using this tool.

Outcomes

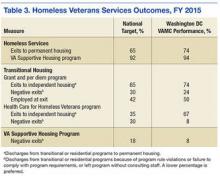

In 2010, the Point-in-Time count identified 718 homeless veterans in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area. By 2016, that number had dropped to 326 (55% reduction). During this same period, the number of veterans served by the Washington DC VAMC homeless program more than tripled, from 2,100 individuals in 2010 to nearly 6,400 in 2015. The coalition has housed or prevented homelessness for nearly 1,300 veterans during the past 2 years alone. Veterans were housed through multiple programs and efforts, including VA Supportive Housing (VASH), Supportive Services for Veteran Families, and Washington, DC Department of Human Services Permanent Supportive Housing. During the past year, > 60% of veterans were successfully placed in VASH housing within 90 days of application submission. Table 3 lists the national targets for assessing performance measurement and success. Not only were the various performance measure benchmarks exceeded, but more important, > 90% of veterans in VASH and Health Care for Homeless Veterans were able to keep their housing stabilized. Using SPDAT, the most chronically homeless and vulnerable were housed first, which accounts for the lower numbers of homeless Washington, DC, area veterans with substance abuse and mental health problems identified in the Point-in-Time survey.

Discussion

At the Washington DC VAMC, HCHV program staff members used evidence-based and evidence-informed tools, collaborated with community partners, and implemented recommended best practices to end veteran homelessness by 2015. Permanent supportive housing through VASH is crucial for helping veterans overcome their lack of income and in providing mechanisms for engaging in mental health and substance abuse services as well as primary care and therapeutic employment opportunities.

When former VA Secretary Eric K. Shinseki first announced the goal of ending veteran homelessness by 2015, many people questioned this goal’s attainability and feasibility. However, through the adoption of the strategies recommended by USICH, the establishment of government and community partnerships (including faith-based groups) and the implementation of programs addressing substance abuse issues, mental and physical health, income limitations, and employment, this goal now seems possible. Overall veteran homelessness decreased by 36% since 2010, and unsheltered homelessness decreased by nearly 50%.30 By the end of 2015, nearly 65,000 veterans are in permanent housing nationwide, and another 8,100 are in the process of obtaining permanent supportive housing. Also, 87% of unsheltered veterans were able to move to safe housing within 30 days of engagement. Last, Supportive Services for Veteran Families was able to assist more than 156,800 individuals (single veterans as well as their children and families).

Sustainability from a national perspective also depends on continued federal funding. Mr. G, described at the beginning of this article, served his country honorably but then experienced the factors that put him at risk for homelessness. Through a veteran-centric team approach, he was able to successfully address each of these factors. As there are another 500 homeless veterans in Washington, DC, much work still needs to be done. With important collaborations and partnerships now in place, the goal of ending veteran homelessness in the District of Columbia is within sight. When homelessness is a thing of the past, we will truly be able to Welcome Home each veteran.

1. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans Veteran Homelessness: A Supplemental Report to the 2009 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress.https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2009AHARveterans Report.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2016.

2. HUD Exchange. Homeless emergency assistance and rapid transition to housing (HEARTH): defining “homeless” final rule. HUD Exchange website. https://www.hudexchange.info/resource/1928 /hearth-defining-homeless-final-rule. Published November 2011. Accessed April 5, 2016.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Community Living (ACL), Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. The Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act of 2000. http://www.acl.gov/Programs/AIDD/DDA_BOR _ACT_2000/docs/dd_act.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2016. 4. Hwang SW. Mortality among men using homeless shelters in Toronto, Ontario. JAMA. 2000;283(16):2152-2157.

5. O’Connell JJ. Premature Mortality in Homeless Populations: A Review of the Literature. Nashville, TN: National Health Care for the Homeless Council; 2005.

6. Salit SA, Kuhn EM, Hartz AJ, Vu JM, Mosso AL. Hopitalization costs associated with homelessness in New York City. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(24):1734-1740.

7. Kushel MB, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R, Moss AR. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):778-784.

8. Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, et al. Healthcare and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA. 2009;301(13):1349-1357.

9. McNeil DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC. Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(7):840-846.

10. Rosenheck R. Cost-effectiveness of services for mentally ill homeless people: the application of research to policy and practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1563-1570.

11. Culhane DP, Metraux S, Hadley T. Public service reductions associated with placement of homeless people with severe mental illness in supportive housing. Housing Policy Debate. 2002;13(1):107-163.

12. Martinez TE, Burt MR. Impact of permanent supportive housing on the use of acute care health services by homeless adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(7):992-999.

13. Culhane DP, Parker WD, Poppe B, et al. Accountability, cost-effectiveness, and program performance: progress since 1998. In: Dennis D, Locke G, Khadduri J, eds. Toward Understanding Homelessness: The 2007 National Symposium on Homelessness Research. Washington, DC: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; Office of Policy Development and Research, U.S. Dept of Housing and Urban Development; 2007.

14. Poulin SR, Maguire M, Metraux S, Culhane DP. Service use and costs for persons experiencing chronic homelessness in Philadelphia: a population-based study. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(11):1093-1098.

15. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA History in Brief. http://www.va.gov/opa/publications/archives /docs/history_in_brief.pdf. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs website. Published December 27, 2013. Accessed April 19, 2016.

16. Kusmer KL. Down and Out, on the Road: The Homeless in American History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002.

17. Baumohl J, ed. Homelessness in America. Westport, CT: Oryx Press; 1996.

18. Fargo J, Metraux S, Byrne T, et al. Prevalence and risk of homelessness among U.S. veterans: a multisite investigation. http://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/docs/Center/Prevalence_Final.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed April 19, 2016.

19. Tsai J, Mares AS, Rosenheck R, Gamache D. Do homeless veterans have the same needs and outcomes as non-veterans? Mil Med. 2012;177(1):27-31.

20. Metraux S, Clegg L, Daigh JD, Culhane DP, Kane V. Risk factors for becoming homeless among a cohort of veterans who served in the era of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(suppl 2):S255-S261.

21. Perl L. Veterans and homelessness. Congressional research Service Report RL34024. https://www.fas .org/sgp/crs/misc/RL34024.pdf.Published November 6, 2015. Accessed April 7, 2016.

22. Rossi PH. Down and Out in America: The Origins of Homelessness. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1989.

23. Burt M. Over the Edge: The Growth of Homelessness in the 1980s. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1992.

24. National Coalition for the Homeless. Homeless Veterans [fact sheet]. http://www .nationalhomeless.org/factsheets/veterans.html. September 2009. Accessed April 19, 2016.

25. Tessler R, Rosenheck R, Gamache F. Comparison of homeless veterans with other homeless men in a large clinical outreach program. Psychiatr Q. 2002;73(2):109-119.

26. Chapman H. Homelessness in Metropolitan Washington: Results and Analysis From the 2015 Point-in-Time Count of Persons Experiencing Homelessness in the Metropolitan Washington Region. Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments website. https://www .mwcog.org/uploads/pub-documents/v15Wlk20150514094353.pdf. Published May 13, 2015. Accessed April 6, 2016.

27. Tsai J, Rosenheck R. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177-195.

28. Edens EL, Kasprow W, Tsai J, Rosenheck R. Association of substance use and VA service-connected disability benefits with risk of homelessness among veterans. Am J Addict. 2011;20(5):412-419.

29. OrgCode Consulting. Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool (SPDAT). http://www.orgcode .com/product/spdat/. Accessed April 19, 2016.

30. Performance.gov. End veteran homelessness: progress update. Performance.gov website. https://www.performance.gov/content/end-veteran-homelessness#progressUpdate. Accessed April 6, 2016.

Mr. G is a 67-year-old veteran. During the Vietnam War, he had the “most dangerous job”: helicopter door gunner and mechanic. He served in multiple combat missions and was under constant threat of attack. On returning to the U.S., he experienced anger outbursts, nightmares, hypervigilance, and urges to engage in dangerous behavior, such as driving a motorcycle more than 100 mph. Then he began abusing alcohol and drugs. Mr. G’s behavior and substance abuse eventually led to strained family relationships, termination from a high-paying job, and homelessness.

In 2001, the Washington DC VAMC homeless and substance abuse staff provided outreach and services that helped him secure permanent subsidized housing, achieve and maintain sobriety, get treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and get full-time employment. Mr. G has maintained permanent supported housing status for 9 years, regained a sense of purpose, remained drug- and alcohol-free since 2001, attended a Vietnam combat PTSD support group weekly, and been an exemplary employee for 8 years.

In 2009, on any given night in the U.S., more than 75,000 veterans were without a permanent home and living on the streets, as Mr. G had been.1 Nearly 150,000 other veterans were spending the night in an emergency shelter or transitional housing. In early 2010, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) developed a strategic plan to align federal resources toward 4 key objectives, which included preventing and ending homelessness among veterans. Since then, the most dramatic reductions in homelessness have occurred among veterans, with an overall 33% decline in chronic homelessness nationwide.

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), permanent housing is defined as community-based housing without a designated length of stay in which formerly homeless individuals live as independently as possible.2 Under permanent housing, a program participant must be the tenant on a lease for at least 1 year, and the lease is renewable and terminable only for cause. The federal definition of the chronically homeless is a person who is homeless and lives in a place not meant for human habitation, in a safe haven, or in an emergency shelter continuously for at least 1 year; or on at least 4 separate occasions within the past 3 years; and who can be diagnosed with ≥ 1 of the following conditions: substance use disorder, serious mental illness, developmental disability as defined in section 102 of the Developmental Disabilities Assistance Bill of Rights Act of 2000 (42 U.S.C. 15002), PTSD, cognitive impairments caused by brain injury, and chronic physical illness or disability.3

Ending homelessness makes sense from a variety of perspectives. From a moral perspective, no one should experience homelessness, but this is especially true for the men and women who have served in the U.S. military. From a health care and resources perspective, homelessness is associated with poorer medical outcomes; higher medical costs for emergency department visits and hospital admissions; longer stays (often for conditions that could be treated in ambulatory settings); and increased mortality.4-7 From a societal perspective, homelessness is associated with costs for shelters and other forms of temporary housing and with higher justice system costs stemming from police, court, and jail involvement.8 The higher justice system costs are in part attributable to significantly longer incarcerations for homeless persons than for demographically similar inmates who have been similarly charged but have housing.9 According to recent studies, significant cost reductions have been achieved by addressing homelessness and providing permanent housing, particularly for the chronically homeless with mental illness.10-14

This article describes the efforts that have been made, through collaborations and coalitions of government and community partners, to identify and address risk factors for homelessness in Washington, DC—and ultimately to end veteran homelessness in the nation’s capitol.

Historic Perspective on Veteran Homelessness

Although the problem was first described after the Revolutionary War and again after the Civil War, homelessness among U.S. veterans has only recently been academically studied. During the colonial period, men often were promised pensions or land grants in exchange for military service. Several states failed to deliver on these promises, throwing veterans into dire financial circumstances and leaving them homeless. By the end of the Civil War, the size of the veteran population (almost 2 million, counting only those who fought for the Union), combined with an unemployment rate of 40% and economic downturns, led to thousands of veterans becoming homeless.15,16

Homelessness among veterans continued after World War I. In 1932, more than 15,000 homeless and disabled “Bonus Army,” World War I veterans, marched on Washington to demand payment of the financial benefits promised for their military service.

Although World War II and Korean War veterans did not experience homelessness as previous veterans had, the problem resurfaced after Vietnam—the combat veterans of that war were overrepresented among the homeless.17,18 Those at highest risk ranged from age 35 to 44 years in the early years of the all-volunteer military. It has been suggested that their increased risk may reflect social selection—volunteers for military service came from poor economic backgrounds with fewer social supports.19 A more recent study found that 3.8% of more than 300,000 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans who were followed for 5 years after military discharge experienced a homeless episode.20 Female veterans similarly are overrepresented among the homeless.21 Female veterans represent only 1% of the overall female population, yet 3% to 4% are homeless.

Homelessness has always been a social problem, but only during the 1970s and 1980s did homelessness increase in importance—the number of visibly homeless people rose during that period—and investigators began to study and address the issue. Experts have described several factors that contributed to the increase in homelessness during that time.22,23 First, as part of the deinstitutionalization initiative, thousands of mentally ill persons were released from state mental hospitals without a plan in place for affordable or supervised housing. Second, single-room-occupancy dwellings in poor areas, where transient single men lived, were demolished, and affordable housing options decreased. Third, economic and social changes were factors, such as a decreased need for seasonal and unskilled labor; reduced likelihood that relatives will take in homeless family members; and decriminalized public intoxication, loitering, and vagrancy. Out of these conditions came an interest in studying the causes of and risk factors for veteran homelessness and in developing a multipronged approach to end veteran homelessness.

Demographics

Nationally, veterans account for 9% of the homeless population.24 Predominantly, they are single men living in urban areas—only about 9% are women—and 43% served during the Vietnam era.24 Among homeless veterans, minorities are overrepresented—45% are African American or Hispanic, as contrasted with 10% and 3%, respectively, of the general population. More than two-thirds served in the military for more than 3 years, and 76% have a history of mental illness or substance abuse. Compared with the general homeless population, homeless veterans are older, better educated, more likely to have been married, and more likely to have health insurance, primarily through the VA.24,25

The Washington, DC, metropolitan area encompasses the District of Columbia, northern Virginia, the tricounty area of southern Maryland, and Montgomery and Prince George’s counties in Maryland. Demographics for veterans in this area vary somewhat from national figures. According to the 2015 Point-in-Time survey of the homeless, veterans accounted for 5% of the homeless population (less than the national percentage). Most homeless veterans were single men (11.6% were women) and African American (65% of single adults, 85% of adults in families). Forty-five percent reported being employed and 40% had a substance use disorder or a serious mental illness. A large proportion also had at least 1 physical disability, such as hypertension, hepatitis, arthritis, diabetes mellitus, or heart disease.26

Risk Factors

Multiple studies and multivariate analyses have determined that veteran status is associated with an increased risk for homelessness for both male and female veterans.27 Female veterans were 3 times and male veterans 2 times more likely than nonveterans to become homeless, even when poverty, age, race, and geographic variation were controlled. A recent systematic review of U.S. veterans found that the strongest and most consistent risk factors for homelessness were substance use disorders and mental illness, particularly psychotic disorders. Posttraumatic stress disorder was not more significant than other mental conditions but it was a risk factor. Low income, unemployment, and poor money management were also factors.

Social risk factors include lack of support from family and friends. Military service with multiple deployments, transfers, and on-base housing may contribute to interruption of social support and lead to social isolation, thus increasing veterans’ risk for homelessness. Some studies have found that veterans are more likely to report physical injury or medical problems as contributing to homelessness and more likely to have 2 or more chronic medical conditions. Last, history of incarceration and adverse childhood experiences (eg, behavioral problems, family instability, foster care, childhood abuse) also have been found to be risk factors for homelessness among veterans and nonveterans alike.

Understanding these risk factors is an important step in addressing homelessness. Homelessness prevention efforts can screen for these risk factors and then intervene as quickly as possible. Access to mental health and substance abuse services, employment assistance, disability benefits and other income supports, and social services may prevent initial and subsequent episodes of homelessness. The VA, as the largest integrated health system in the U.S., is a critical safety net for low-income and disabled veterans with complex psychosocial needs. One study found access to VA service-connected pensions was protective against homelessness.28

Addressing Homelessness

There are 10 USICH-recommended strategies for ending veteran homelessness (Table 1). These strategies cannot be achieved by any single federal agency or exclusively by government agencies—they require multipronged approaches and private and public partnerships. In early 2011, the staff of the Washington DC VAMC homeless program identified a single point of contact who would regularly meet with each Continuum of Care local planning body and each Public Housing Authority (PHA). This contact could identify homeless veterans regardless of the agency from which they were requesting assistance. The contact also facilitated identification of specific bottleneck issues contributing to delays in housing veterans. One such issue was that veterans were filling out application forms by themselves, and in some cases, their information was incomplete, or supporting documents (eg, government-issued IDs) were missing. The VA team adjusted the procedures to better meet veterans’ needs. Now veterans identified as meeting requirements for housing assistance are enrolled in classes in which a caseworker reviews their completed applications to ensure they are complete and supporting documents included. If an ID is needed, the caseworker facilitates the process and then submits the veteran’s application to the local PHA for processing. The result has been no returned applications.

Another issue was that in some cases a veteran spoke with the PHA and indicated interest in an apartment and only later found out that the apartment failed inspection. There would then be back-and-forth communications between PHA and landlord to have repairs made so the unit could pass inspection, which often resulted in long delays. The solution was to have a stock of preinspected housing options. The Washington DC VAMC homeless program now has a housing specialist who identifies preinspected units and can expedite the lease to a veteran. In addition, the homeless program in partnership with the PHA now sets up regular meet-and-greet events for landlords and veterans so veterans can preview available rentals.

Housing-First Model

The homeless program readily adopted the housing-first model. This model focuses on helping individuals and families access housing as quickly as possible and remain permanently housed; this assistance is not time-limited but ongoing. After housing placement, the client can choose from an array of both time-limited and long-term services, which are individualized to promote housing stability and individual well-being. Most important, housing is not contingent on compliance with services. Instead, participants must comply with a standard lease agreement and are provided the services and support that can help them do so successfully. Services are determined by completing needs assessments. In addition, as a veteran is applying for housing, a caseworker actively uses motivational interviewing techniques to enhance the likelihood that the veteran will accept services.

Providing Core Service to Veterans

In 2012, the Washington DC VAMC opened the Community Resource and Referral Center (CRRC) as a one-stop shop for homeless and at-risk veterans in need of basic, core, wraparound services through the VA. Basic services include showers, laundry facilities, and a chapel. The CRRC has onsite psychiatric services that can engage veterans in mental health and substance abuse treatment. There is also an onsite primary care team who specialize in working with the homeless and can address any acute or chronic medical problems. For veterans who want to return to employment, there is an onsite Compensated Work Therapy program, which has uniquely partnered with the VAMC as well as community partners (eg, National Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Quantico National Cemetery, Arlington National Cemetery) to offer therapeutic job experiences that often lead to gainful full-time employment.

Veterans can use an onsite computer lab to complete resumes and apply for employment online, with the assistance of veteran peer specialists and vocational rehabilitation specialists. For veterans who are unable to work, the homeless program team assists with disability applications. Social Security, Veterans Benefits Administration representatives, and Legal Aid have office hours at the CRRC to provide one-stop shopping for veterans. Additional community partnerships have led to classes to help veterans manage income effectively, and veterans are assisted with completing tax returns.

Representatives from the Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) and Health Care for Re-entry Veterans (HCRV) programs are also onsite. The VJO program provides outreach, assessment, and case management for justice-involved veterans to prevent unnecessary criminalization of mental illness and extended incarceration. A VJO program specialist works with courts, legal representatives, and jails and acts as a liaison to engage veterans in treatment and prevent incarcerations through jail diversion strategies. The HCRV program assists incarcerated veterans with reentry into the community through outreach and prerelease assessments, and referrals and links to medical, psychiatric, and social services, including employment services on release. This program also can provide short-term case management assistance on release.

In 2013, to further the implementation of the USICH strategies in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area, 12 local government and nonprofit agencies entered into the Veterans NOW coalition (Table 2). This collaboration enabled development of a coordinated effort to identify all area veterans experiencing homelessness, regardless of which agency the veterans contacted. Further, this team set up processes to assess veterans’ housing and service needs and to match each veteran to the most appropriate housing resource. There was consensus regarding use of the Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool (SPDAT) as the evidence-informed approach for prioritizing client needs and identifying areas in which support is most likely needed to prevent housing instability.29 More than 50 staff members at 20 different agencies in the District of Columbia have now been trained and are using this tool.

Outcomes

In 2010, the Point-in-Time count identified 718 homeless veterans in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area. By 2016, that number had dropped to 326 (55% reduction). During this same period, the number of veterans served by the Washington DC VAMC homeless program more than tripled, from 2,100 individuals in 2010 to nearly 6,400 in 2015. The coalition has housed or prevented homelessness for nearly 1,300 veterans during the past 2 years alone. Veterans were housed through multiple programs and efforts, including VA Supportive Housing (VASH), Supportive Services for Veteran Families, and Washington, DC Department of Human Services Permanent Supportive Housing. During the past year, > 60% of veterans were successfully placed in VASH housing within 90 days of application submission. Table 3 lists the national targets for assessing performance measurement and success. Not only were the various performance measure benchmarks exceeded, but more important, > 90% of veterans in VASH and Health Care for Homeless Veterans were able to keep their housing stabilized. Using SPDAT, the most chronically homeless and vulnerable were housed first, which accounts for the lower numbers of homeless Washington, DC, area veterans with substance abuse and mental health problems identified in the Point-in-Time survey.

Discussion

At the Washington DC VAMC, HCHV program staff members used evidence-based and evidence-informed tools, collaborated with community partners, and implemented recommended best practices to end veteran homelessness by 2015. Permanent supportive housing through VASH is crucial for helping veterans overcome their lack of income and in providing mechanisms for engaging in mental health and substance abuse services as well as primary care and therapeutic employment opportunities.

When former VA Secretary Eric K. Shinseki first announced the goal of ending veteran homelessness by 2015, many people questioned this goal’s attainability and feasibility. However, through the adoption of the strategies recommended by USICH, the establishment of government and community partnerships (including faith-based groups) and the implementation of programs addressing substance abuse issues, mental and physical health, income limitations, and employment, this goal now seems possible. Overall veteran homelessness decreased by 36% since 2010, and unsheltered homelessness decreased by nearly 50%.30 By the end of 2015, nearly 65,000 veterans are in permanent housing nationwide, and another 8,100 are in the process of obtaining permanent supportive housing. Also, 87% of unsheltered veterans were able to move to safe housing within 30 days of engagement. Last, Supportive Services for Veteran Families was able to assist more than 156,800 individuals (single veterans as well as their children and families).

Sustainability from a national perspective also depends on continued federal funding. Mr. G, described at the beginning of this article, served his country honorably but then experienced the factors that put him at risk for homelessness. Through a veteran-centric team approach, he was able to successfully address each of these factors. As there are another 500 homeless veterans in Washington, DC, much work still needs to be done. With important collaborations and partnerships now in place, the goal of ending veteran homelessness in the District of Columbia is within sight. When homelessness is a thing of the past, we will truly be able to Welcome Home each veteran.

Mr. G is a 67-year-old veteran. During the Vietnam War, he had the “most dangerous job”: helicopter door gunner and mechanic. He served in multiple combat missions and was under constant threat of attack. On returning to the U.S., he experienced anger outbursts, nightmares, hypervigilance, and urges to engage in dangerous behavior, such as driving a motorcycle more than 100 mph. Then he began abusing alcohol and drugs. Mr. G’s behavior and substance abuse eventually led to strained family relationships, termination from a high-paying job, and homelessness.

In 2001, the Washington DC VAMC homeless and substance abuse staff provided outreach and services that helped him secure permanent subsidized housing, achieve and maintain sobriety, get treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and get full-time employment. Mr. G has maintained permanent supported housing status for 9 years, regained a sense of purpose, remained drug- and alcohol-free since 2001, attended a Vietnam combat PTSD support group weekly, and been an exemplary employee for 8 years.

In 2009, on any given night in the U.S., more than 75,000 veterans were without a permanent home and living on the streets, as Mr. G had been.1 Nearly 150,000 other veterans were spending the night in an emergency shelter or transitional housing. In early 2010, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) developed a strategic plan to align federal resources toward 4 key objectives, which included preventing and ending homelessness among veterans. Since then, the most dramatic reductions in homelessness have occurred among veterans, with an overall 33% decline in chronic homelessness nationwide.

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), permanent housing is defined as community-based housing without a designated length of stay in which formerly homeless individuals live as independently as possible.2 Under permanent housing, a program participant must be the tenant on a lease for at least 1 year, and the lease is renewable and terminable only for cause. The federal definition of the chronically homeless is a person who is homeless and lives in a place not meant for human habitation, in a safe haven, or in an emergency shelter continuously for at least 1 year; or on at least 4 separate occasions within the past 3 years; and who can be diagnosed with ≥ 1 of the following conditions: substance use disorder, serious mental illness, developmental disability as defined in section 102 of the Developmental Disabilities Assistance Bill of Rights Act of 2000 (42 U.S.C. 15002), PTSD, cognitive impairments caused by brain injury, and chronic physical illness or disability.3

Ending homelessness makes sense from a variety of perspectives. From a moral perspective, no one should experience homelessness, but this is especially true for the men and women who have served in the U.S. military. From a health care and resources perspective, homelessness is associated with poorer medical outcomes; higher medical costs for emergency department visits and hospital admissions; longer stays (often for conditions that could be treated in ambulatory settings); and increased mortality.4-7 From a societal perspective, homelessness is associated with costs for shelters and other forms of temporary housing and with higher justice system costs stemming from police, court, and jail involvement.8 The higher justice system costs are in part attributable to significantly longer incarcerations for homeless persons than for demographically similar inmates who have been similarly charged but have housing.9 According to recent studies, significant cost reductions have been achieved by addressing homelessness and providing permanent housing, particularly for the chronically homeless with mental illness.10-14

This article describes the efforts that have been made, through collaborations and coalitions of government and community partners, to identify and address risk factors for homelessness in Washington, DC—and ultimately to end veteran homelessness in the nation’s capitol.

Historic Perspective on Veteran Homelessness

Although the problem was first described after the Revolutionary War and again after the Civil War, homelessness among U.S. veterans has only recently been academically studied. During the colonial period, men often were promised pensions or land grants in exchange for military service. Several states failed to deliver on these promises, throwing veterans into dire financial circumstances and leaving them homeless. By the end of the Civil War, the size of the veteran population (almost 2 million, counting only those who fought for the Union), combined with an unemployment rate of 40% and economic downturns, led to thousands of veterans becoming homeless.15,16

Homelessness among veterans continued after World War I. In 1932, more than 15,000 homeless and disabled “Bonus Army,” World War I veterans, marched on Washington to demand payment of the financial benefits promised for their military service.

Although World War II and Korean War veterans did not experience homelessness as previous veterans had, the problem resurfaced after Vietnam—the combat veterans of that war were overrepresented among the homeless.17,18 Those at highest risk ranged from age 35 to 44 years in the early years of the all-volunteer military. It has been suggested that their increased risk may reflect social selection—volunteers for military service came from poor economic backgrounds with fewer social supports.19 A more recent study found that 3.8% of more than 300,000 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans who were followed for 5 years after military discharge experienced a homeless episode.20 Female veterans similarly are overrepresented among the homeless.21 Female veterans represent only 1% of the overall female population, yet 3% to 4% are homeless.

Homelessness has always been a social problem, but only during the 1970s and 1980s did homelessness increase in importance—the number of visibly homeless people rose during that period—and investigators began to study and address the issue. Experts have described several factors that contributed to the increase in homelessness during that time.22,23 First, as part of the deinstitutionalization initiative, thousands of mentally ill persons were released from state mental hospitals without a plan in place for affordable or supervised housing. Second, single-room-occupancy dwellings in poor areas, where transient single men lived, were demolished, and affordable housing options decreased. Third, economic and social changes were factors, such as a decreased need for seasonal and unskilled labor; reduced likelihood that relatives will take in homeless family members; and decriminalized public intoxication, loitering, and vagrancy. Out of these conditions came an interest in studying the causes of and risk factors for veteran homelessness and in developing a multipronged approach to end veteran homelessness.

Demographics

Nationally, veterans account for 9% of the homeless population.24 Predominantly, they are single men living in urban areas—only about 9% are women—and 43% served during the Vietnam era.24 Among homeless veterans, minorities are overrepresented—45% are African American or Hispanic, as contrasted with 10% and 3%, respectively, of the general population. More than two-thirds served in the military for more than 3 years, and 76% have a history of mental illness or substance abuse. Compared with the general homeless population, homeless veterans are older, better educated, more likely to have been married, and more likely to have health insurance, primarily through the VA.24,25

The Washington, DC, metropolitan area encompasses the District of Columbia, northern Virginia, the tricounty area of southern Maryland, and Montgomery and Prince George’s counties in Maryland. Demographics for veterans in this area vary somewhat from national figures. According to the 2015 Point-in-Time survey of the homeless, veterans accounted for 5% of the homeless population (less than the national percentage). Most homeless veterans were single men (11.6% were women) and African American (65% of single adults, 85% of adults in families). Forty-five percent reported being employed and 40% had a substance use disorder or a serious mental illness. A large proportion also had at least 1 physical disability, such as hypertension, hepatitis, arthritis, diabetes mellitus, or heart disease.26

Risk Factors

Multiple studies and multivariate analyses have determined that veteran status is associated with an increased risk for homelessness for both male and female veterans.27 Female veterans were 3 times and male veterans 2 times more likely than nonveterans to become homeless, even when poverty, age, race, and geographic variation were controlled. A recent systematic review of U.S. veterans found that the strongest and most consistent risk factors for homelessness were substance use disorders and mental illness, particularly psychotic disorders. Posttraumatic stress disorder was not more significant than other mental conditions but it was a risk factor. Low income, unemployment, and poor money management were also factors.

Social risk factors include lack of support from family and friends. Military service with multiple deployments, transfers, and on-base housing may contribute to interruption of social support and lead to social isolation, thus increasing veterans’ risk for homelessness. Some studies have found that veterans are more likely to report physical injury or medical problems as contributing to homelessness and more likely to have 2 or more chronic medical conditions. Last, history of incarceration and adverse childhood experiences (eg, behavioral problems, family instability, foster care, childhood abuse) also have been found to be risk factors for homelessness among veterans and nonveterans alike.

Understanding these risk factors is an important step in addressing homelessness. Homelessness prevention efforts can screen for these risk factors and then intervene as quickly as possible. Access to mental health and substance abuse services, employment assistance, disability benefits and other income supports, and social services may prevent initial and subsequent episodes of homelessness. The VA, as the largest integrated health system in the U.S., is a critical safety net for low-income and disabled veterans with complex psychosocial needs. One study found access to VA service-connected pensions was protective against homelessness.28

Addressing Homelessness

There are 10 USICH-recommended strategies for ending veteran homelessness (Table 1). These strategies cannot be achieved by any single federal agency or exclusively by government agencies—they require multipronged approaches and private and public partnerships. In early 2011, the staff of the Washington DC VAMC homeless program identified a single point of contact who would regularly meet with each Continuum of Care local planning body and each Public Housing Authority (PHA). This contact could identify homeless veterans regardless of the agency from which they were requesting assistance. The contact also facilitated identification of specific bottleneck issues contributing to delays in housing veterans. One such issue was that veterans were filling out application forms by themselves, and in some cases, their information was incomplete, or supporting documents (eg, government-issued IDs) were missing. The VA team adjusted the procedures to better meet veterans’ needs. Now veterans identified as meeting requirements for housing assistance are enrolled in classes in which a caseworker reviews their completed applications to ensure they are complete and supporting documents included. If an ID is needed, the caseworker facilitates the process and then submits the veteran’s application to the local PHA for processing. The result has been no returned applications.

Another issue was that in some cases a veteran spoke with the PHA and indicated interest in an apartment and only later found out that the apartment failed inspection. There would then be back-and-forth communications between PHA and landlord to have repairs made so the unit could pass inspection, which often resulted in long delays. The solution was to have a stock of preinspected housing options. The Washington DC VAMC homeless program now has a housing specialist who identifies preinspected units and can expedite the lease to a veteran. In addition, the homeless program in partnership with the PHA now sets up regular meet-and-greet events for landlords and veterans so veterans can preview available rentals.

Housing-First Model

The homeless program readily adopted the housing-first model. This model focuses on helping individuals and families access housing as quickly as possible and remain permanently housed; this assistance is not time-limited but ongoing. After housing placement, the client can choose from an array of both time-limited and long-term services, which are individualized to promote housing stability and individual well-being. Most important, housing is not contingent on compliance with services. Instead, participants must comply with a standard lease agreement and are provided the services and support that can help them do so successfully. Services are determined by completing needs assessments. In addition, as a veteran is applying for housing, a caseworker actively uses motivational interviewing techniques to enhance the likelihood that the veteran will accept services.

Providing Core Service to Veterans

In 2012, the Washington DC VAMC opened the Community Resource and Referral Center (CRRC) as a one-stop shop for homeless and at-risk veterans in need of basic, core, wraparound services through the VA. Basic services include showers, laundry facilities, and a chapel. The CRRC has onsite psychiatric services that can engage veterans in mental health and substance abuse treatment. There is also an onsite primary care team who specialize in working with the homeless and can address any acute or chronic medical problems. For veterans who want to return to employment, there is an onsite Compensated Work Therapy program, which has uniquely partnered with the VAMC as well as community partners (eg, National Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Quantico National Cemetery, Arlington National Cemetery) to offer therapeutic job experiences that often lead to gainful full-time employment.

Veterans can use an onsite computer lab to complete resumes and apply for employment online, with the assistance of veteran peer specialists and vocational rehabilitation specialists. For veterans who are unable to work, the homeless program team assists with disability applications. Social Security, Veterans Benefits Administration representatives, and Legal Aid have office hours at the CRRC to provide one-stop shopping for veterans. Additional community partnerships have led to classes to help veterans manage income effectively, and veterans are assisted with completing tax returns.

Representatives from the Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) and Health Care for Re-entry Veterans (HCRV) programs are also onsite. The VJO program provides outreach, assessment, and case management for justice-involved veterans to prevent unnecessary criminalization of mental illness and extended incarceration. A VJO program specialist works with courts, legal representatives, and jails and acts as a liaison to engage veterans in treatment and prevent incarcerations through jail diversion strategies. The HCRV program assists incarcerated veterans with reentry into the community through outreach and prerelease assessments, and referrals and links to medical, psychiatric, and social services, including employment services on release. This program also can provide short-term case management assistance on release.

In 2013, to further the implementation of the USICH strategies in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area, 12 local government and nonprofit agencies entered into the Veterans NOW coalition (Table 2). This collaboration enabled development of a coordinated effort to identify all area veterans experiencing homelessness, regardless of which agency the veterans contacted. Further, this team set up processes to assess veterans’ housing and service needs and to match each veteran to the most appropriate housing resource. There was consensus regarding use of the Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool (SPDAT) as the evidence-informed approach for prioritizing client needs and identifying areas in which support is most likely needed to prevent housing instability.29 More than 50 staff members at 20 different agencies in the District of Columbia have now been trained and are using this tool.

Outcomes

In 2010, the Point-in-Time count identified 718 homeless veterans in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area. By 2016, that number had dropped to 326 (55% reduction). During this same period, the number of veterans served by the Washington DC VAMC homeless program more than tripled, from 2,100 individuals in 2010 to nearly 6,400 in 2015. The coalition has housed or prevented homelessness for nearly 1,300 veterans during the past 2 years alone. Veterans were housed through multiple programs and efforts, including VA Supportive Housing (VASH), Supportive Services for Veteran Families, and Washington, DC Department of Human Services Permanent Supportive Housing. During the past year, > 60% of veterans were successfully placed in VASH housing within 90 days of application submission. Table 3 lists the national targets for assessing performance measurement and success. Not only were the various performance measure benchmarks exceeded, but more important, > 90% of veterans in VASH and Health Care for Homeless Veterans were able to keep their housing stabilized. Using SPDAT, the most chronically homeless and vulnerable were housed first, which accounts for the lower numbers of homeless Washington, DC, area veterans with substance abuse and mental health problems identified in the Point-in-Time survey.

Discussion

At the Washington DC VAMC, HCHV program staff members used evidence-based and evidence-informed tools, collaborated with community partners, and implemented recommended best practices to end veteran homelessness by 2015. Permanent supportive housing through VASH is crucial for helping veterans overcome their lack of income and in providing mechanisms for engaging in mental health and substance abuse services as well as primary care and therapeutic employment opportunities.

When former VA Secretary Eric K. Shinseki first announced the goal of ending veteran homelessness by 2015, many people questioned this goal’s attainability and feasibility. However, through the adoption of the strategies recommended by USICH, the establishment of government and community partnerships (including faith-based groups) and the implementation of programs addressing substance abuse issues, mental and physical health, income limitations, and employment, this goal now seems possible. Overall veteran homelessness decreased by 36% since 2010, and unsheltered homelessness decreased by nearly 50%.30 By the end of 2015, nearly 65,000 veterans are in permanent housing nationwide, and another 8,100 are in the process of obtaining permanent supportive housing. Also, 87% of unsheltered veterans were able to move to safe housing within 30 days of engagement. Last, Supportive Services for Veteran Families was able to assist more than 156,800 individuals (single veterans as well as their children and families).

Sustainability from a national perspective also depends on continued federal funding. Mr. G, described at the beginning of this article, served his country honorably but then experienced the factors that put him at risk for homelessness. Through a veteran-centric team approach, he was able to successfully address each of these factors. As there are another 500 homeless veterans in Washington, DC, much work still needs to be done. With important collaborations and partnerships now in place, the goal of ending veteran homelessness in the District of Columbia is within sight. When homelessness is a thing of the past, we will truly be able to Welcome Home each veteran.

1. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans Veteran Homelessness: A Supplemental Report to the 2009 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress.https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2009AHARveterans Report.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2016.

2. HUD Exchange. Homeless emergency assistance and rapid transition to housing (HEARTH): defining “homeless” final rule. HUD Exchange website. https://www.hudexchange.info/resource/1928 /hearth-defining-homeless-final-rule. Published November 2011. Accessed April 5, 2016.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Community Living (ACL), Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. The Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act of 2000. http://www.acl.gov/Programs/AIDD/DDA_BOR _ACT_2000/docs/dd_act.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2016. 4. Hwang SW. Mortality among men using homeless shelters in Toronto, Ontario. JAMA. 2000;283(16):2152-2157.

5. O’Connell JJ. Premature Mortality in Homeless Populations: A Review of the Literature. Nashville, TN: National Health Care for the Homeless Council; 2005.

6. Salit SA, Kuhn EM, Hartz AJ, Vu JM, Mosso AL. Hopitalization costs associated with homelessness in New York City. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(24):1734-1740.

7. Kushel MB, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R, Moss AR. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):778-784.

8. Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, et al. Healthcare and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA. 2009;301(13):1349-1357.

9. McNeil DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC. Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(7):840-846.

10. Rosenheck R. Cost-effectiveness of services for mentally ill homeless people: the application of research to policy and practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1563-1570.

11. Culhane DP, Metraux S, Hadley T. Public service reductions associated with placement of homeless people with severe mental illness in supportive housing. Housing Policy Debate. 2002;13(1):107-163.

12. Martinez TE, Burt MR. Impact of permanent supportive housing on the use of acute care health services by homeless adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(7):992-999.

13. Culhane DP, Parker WD, Poppe B, et al. Accountability, cost-effectiveness, and program performance: progress since 1998. In: Dennis D, Locke G, Khadduri J, eds. Toward Understanding Homelessness: The 2007 National Symposium on Homelessness Research. Washington, DC: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; Office of Policy Development and Research, U.S. Dept of Housing and Urban Development; 2007.

14. Poulin SR, Maguire M, Metraux S, Culhane DP. Service use and costs for persons experiencing chronic homelessness in Philadelphia: a population-based study. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(11):1093-1098.

15. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA History in Brief. http://www.va.gov/opa/publications/archives /docs/history_in_brief.pdf. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs website. Published December 27, 2013. Accessed April 19, 2016.

16. Kusmer KL. Down and Out, on the Road: The Homeless in American History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002.

17. Baumohl J, ed. Homelessness in America. Westport, CT: Oryx Press; 1996.

18. Fargo J, Metraux S, Byrne T, et al. Prevalence and risk of homelessness among U.S. veterans: a multisite investigation. http://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/docs/Center/Prevalence_Final.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed April 19, 2016.

19. Tsai J, Mares AS, Rosenheck R, Gamache D. Do homeless veterans have the same needs and outcomes as non-veterans? Mil Med. 2012;177(1):27-31.

20. Metraux S, Clegg L, Daigh JD, Culhane DP, Kane V. Risk factors for becoming homeless among a cohort of veterans who served in the era of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(suppl 2):S255-S261.

21. Perl L. Veterans and homelessness. Congressional research Service Report RL34024. https://www.fas .org/sgp/crs/misc/RL34024.pdf.Published November 6, 2015. Accessed April 7, 2016.

22. Rossi PH. Down and Out in America: The Origins of Homelessness. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1989.

23. Burt M. Over the Edge: The Growth of Homelessness in the 1980s. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1992.

24. National Coalition for the Homeless. Homeless Veterans [fact sheet]. http://www .nationalhomeless.org/factsheets/veterans.html. September 2009. Accessed April 19, 2016.

25. Tessler R, Rosenheck R, Gamache F. Comparison of homeless veterans with other homeless men in a large clinical outreach program. Psychiatr Q. 2002;73(2):109-119.

26. Chapman H. Homelessness in Metropolitan Washington: Results and Analysis From the 2015 Point-in-Time Count of Persons Experiencing Homelessness in the Metropolitan Washington Region. Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments website. https://www .mwcog.org/uploads/pub-documents/v15Wlk20150514094353.pdf. Published May 13, 2015. Accessed April 6, 2016.

27. Tsai J, Rosenheck R. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177-195.

28. Edens EL, Kasprow W, Tsai J, Rosenheck R. Association of substance use and VA service-connected disability benefits with risk of homelessness among veterans. Am J Addict. 2011;20(5):412-419.

29. OrgCode Consulting. Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool (SPDAT). http://www.orgcode .com/product/spdat/. Accessed April 19, 2016.

30. Performance.gov. End veteran homelessness: progress update. Performance.gov website. https://www.performance.gov/content/end-veteran-homelessness#progressUpdate. Accessed April 6, 2016.

1. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans Veteran Homelessness: A Supplemental Report to the 2009 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress.https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2009AHARveterans Report.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2016.

2. HUD Exchange. Homeless emergency assistance and rapid transition to housing (HEARTH): defining “homeless” final rule. HUD Exchange website. https://www.hudexchange.info/resource/1928 /hearth-defining-homeless-final-rule. Published November 2011. Accessed April 5, 2016.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Community Living (ACL), Administration on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. The Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act of 2000. http://www.acl.gov/Programs/AIDD/DDA_BOR _ACT_2000/docs/dd_act.pdf. Accessed April 5, 2016. 4. Hwang SW. Mortality among men using homeless shelters in Toronto, Ontario. JAMA. 2000;283(16):2152-2157.

5. O’Connell JJ. Premature Mortality in Homeless Populations: A Review of the Literature. Nashville, TN: National Health Care for the Homeless Council; 2005.

6. Salit SA, Kuhn EM, Hartz AJ, Vu JM, Mosso AL. Hopitalization costs associated with homelessness in New York City. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(24):1734-1740.

7. Kushel MB, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R, Moss AR. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):778-784.

8. Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, et al. Healthcare and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA. 2009;301(13):1349-1357.

9. McNeil DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC. Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(7):840-846.

10. Rosenheck R. Cost-effectiveness of services for mentally ill homeless people: the application of research to policy and practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1563-1570.

11. Culhane DP, Metraux S, Hadley T. Public service reductions associated with placement of homeless people with severe mental illness in supportive housing. Housing Policy Debate. 2002;13(1):107-163.

12. Martinez TE, Burt MR. Impact of permanent supportive housing on the use of acute care health services by homeless adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(7):992-999.

13. Culhane DP, Parker WD, Poppe B, et al. Accountability, cost-effectiveness, and program performance: progress since 1998. In: Dennis D, Locke G, Khadduri J, eds. Toward Understanding Homelessness: The 2007 National Symposium on Homelessness Research. Washington, DC: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; Office of Policy Development and Research, U.S. Dept of Housing and Urban Development; 2007.

14. Poulin SR, Maguire M, Metraux S, Culhane DP. Service use and costs for persons experiencing chronic homelessness in Philadelphia: a population-based study. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(11):1093-1098.

15. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA History in Brief. http://www.va.gov/opa/publications/archives /docs/history_in_brief.pdf. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs website. Published December 27, 2013. Accessed April 19, 2016.

16. Kusmer KL. Down and Out, on the Road: The Homeless in American History. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002.

17. Baumohl J, ed. Homelessness in America. Westport, CT: Oryx Press; 1996.

18. Fargo J, Metraux S, Byrne T, et al. Prevalence and risk of homelessness among U.S. veterans: a multisite investigation. http://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/docs/Center/Prevalence_Final.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed April 19, 2016.

19. Tsai J, Mares AS, Rosenheck R, Gamache D. Do homeless veterans have the same needs and outcomes as non-veterans? Mil Med. 2012;177(1):27-31.

20. Metraux S, Clegg L, Daigh JD, Culhane DP, Kane V. Risk factors for becoming homeless among a cohort of veterans who served in the era of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(suppl 2):S255-S261.

21. Perl L. Veterans and homelessness. Congressional research Service Report RL34024. https://www.fas .org/sgp/crs/misc/RL34024.pdf.Published November 6, 2015. Accessed April 7, 2016.

22. Rossi PH. Down and Out in America: The Origins of Homelessness. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1989.

23. Burt M. Over the Edge: The Growth of Homelessness in the 1980s. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 1992.

24. National Coalition for the Homeless. Homeless Veterans [fact sheet]. http://www .nationalhomeless.org/factsheets/veterans.html. September 2009. Accessed April 19, 2016.

25. Tessler R, Rosenheck R, Gamache F. Comparison of homeless veterans with other homeless men in a large clinical outreach program. Psychiatr Q. 2002;73(2):109-119.

26. Chapman H. Homelessness in Metropolitan Washington: Results and Analysis From the 2015 Point-in-Time Count of Persons Experiencing Homelessness in the Metropolitan Washington Region. Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments website. https://www .mwcog.org/uploads/pub-documents/v15Wlk20150514094353.pdf. Published May 13, 2015. Accessed April 6, 2016.

27. Tsai J, Rosenheck R. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177-195.

28. Edens EL, Kasprow W, Tsai J, Rosenheck R. Association of substance use and VA service-connected disability benefits with risk of homelessness among veterans. Am J Addict. 2011;20(5):412-419.

29. OrgCode Consulting. Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool (SPDAT). http://www.orgcode .com/product/spdat/. Accessed April 19, 2016.