User login

Surgical Specimens and Margins

We have attended grand rounds presentations at which students announce that Mohs micrographic surgery evaluates 100% of the surgical margin, whereas standard excision samples 1% to 2% of the margin; we have even fielded questions from neighbors who have come across this information on the internet.1-5 This statement describes a best-case scenario for Mohs surgery and a worst-case scenario for standard excision. We believe that it is important for clinicians to have a more nuanced understanding of how simple excisions are processed so that they can have pertinent discussions with patients, especially now that there is increasing access to personal health information along with increased agency in patient decision-making.

Margins for Mohs Surgery

Theoretically, Mohs surgery should sample all true surgical margins by complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep-margin assessment. Unfortunately, some sections are not cut full face—sections may not always sample a complete surface—when technicians make an error or lack expertise. Some sections may have small tissue folds or small gaps that prevent complete visualization. We estimate that the Mohs sections we review in consultation that are prepared by private practice Mohs surgeons in our communities visualize approximately 98% of surgical margins on average. Incomplete sections contribute to the rare tumor recurrences after Mohs surgery of approximately 2% to 3%.6

Standard Excision Margins

When we obtained the references cited in articles asserting that

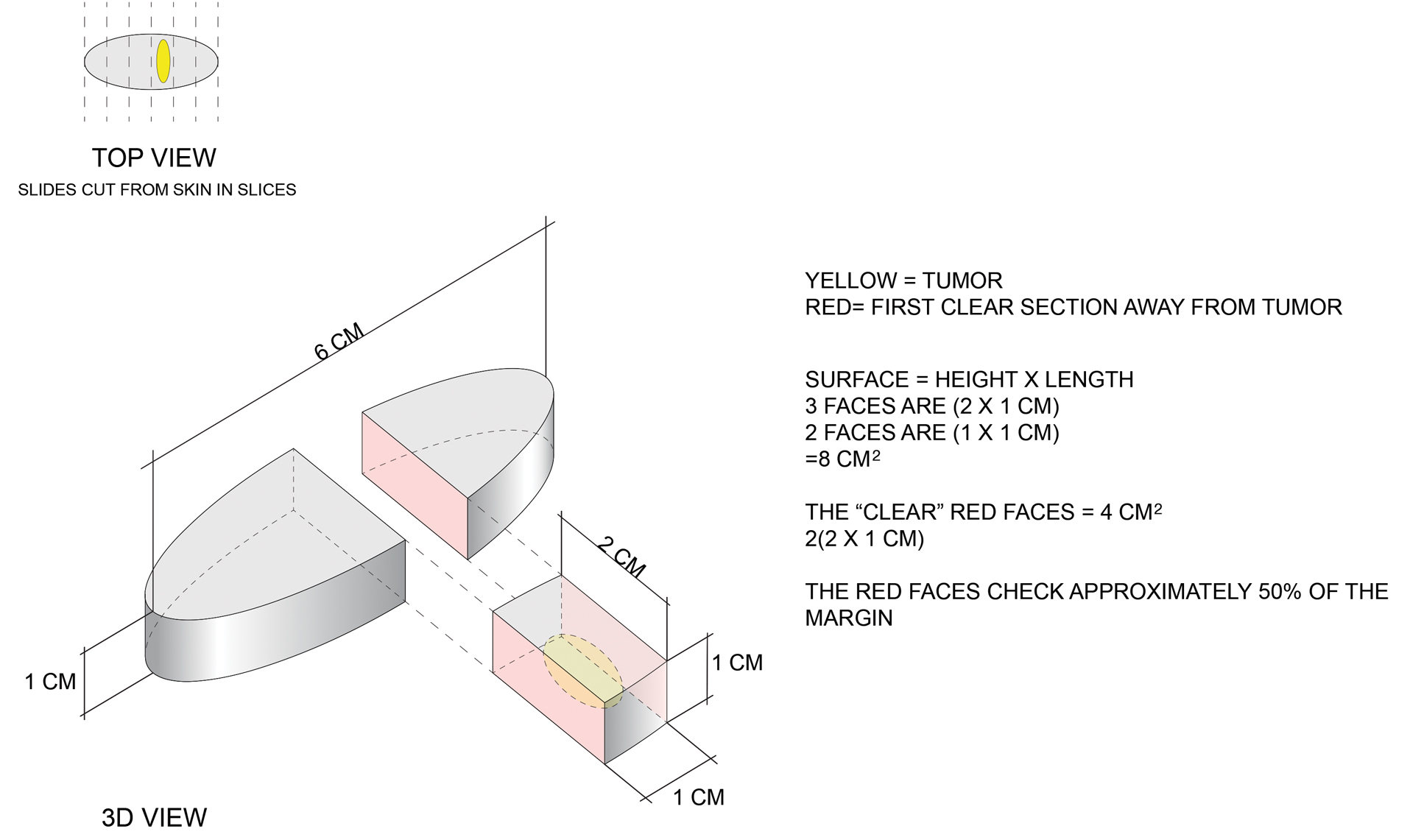

Here is a simple example to show that more margin is accessed in some cases. Consider this hypothetical situation: If a tumor can be readily visualized grossly and housed entirely within an imaginary cuboid (rectangular) prism that is removed in an elliptical specimen with a length of 6 cm, a width of 2 cm, and a height of 1 cm (Figure), then standard sectioning assesses a greater margin.

Bread-loaf sectioning would be expected to examine the complete surface of 2 sides (faces) of the cuboid. Assessing 2 of the 5 clinically relevant sides provides information for approximately 50% of the margins, as sections in the next parallel plane can be expected to be clear after the first clear section is identified. The clinically useful information is not limited to the sum of the widths of sections. Encountering a clear plane typically indicates that there will be no tumor in more distal parallel planes. Warne et al6 developed a formula that can accurately predict the percentage of the margin evaluated by proxy that considers the curvature of the ellipse.

Comparing Standard Excision and Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery consistently results in the best outcomes, but standard excision is effective, too. Standard excision is relatively simple, requires less equipment, is less time consuming, and can provide good value when resources are finite. Data on recurrence of basal cell carcinoma after simple excision are limited, but the recurrence rate is reported to be approximately 3%.7,8 A meta-analysis found that the recurrence rate of basal cell carcinoma treated with standard excision was 0.4%, 1.6%, 2.6%, and 4% with 5-mm, 4-mm, 3-mm, and 2-mm surgical margins, respectively.9

Mohs surgery is the best, most effective, and most tissue-sparing technique for certain nonmelanoma skin cancers. This observation is reflected in guidelines worldwide.10 The adequacy of standard approaches to margin evaluation depends on the capabilities and focus of the laboratory team. Dermatopathologists often are called to the laboratory to decide which technique will be best for a particular case.11 Technicians are trained to take more sections in areas where abnormalities are seen, and some laboratories take photographs of specimens or provide sketches for correlation. Dermatopathologists also routinely request additional sections in areas where visible tumor extends close to surgical margins on microscopic examination.

It is not simply a matter of knowing how much of the margin is sampled but if the most pertinent areas are adequately sampled. Simple sectioning can work well and be cost effective. Many clinicians are unaware of how tissue processing can vary from laboratory to laboratory. There are no uniformly accepted standards for how tissue should be processed. Assiduous and thoughtful evaluation of specimens can affect results. As with any service, some laboratories provide more detailed and conscientious care while others focus more on immediate costs. Clinicians should understand how their specimens are processed by discussing margin evaluation with their dermatopathologist.

Final Thoughts

Used appropriately, Mohs surgery is an excellent technique that can provide outstanding results. Standard excision also has an important place in the dermatologist’s armamentarium and typically provides information about more than 1% to 2% of the margin. Understanding the techniques used to process specimens is critical to delivering the best possible care.

- Tolkachjov SN, Brodland DG, Coldiron BM, et al. Understanding Mohs micrographic surgery: a review and practical guide for the nondermatologist. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1261-1271. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.009

- Thomas RM, Amonette RA. Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician. 1988;37:135-142.

- Buker JL, Amonette RA. Micrographic surgery. Clin Dermatol. 1992:10:309-315. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(92)90074-9

- Kauvar ANB. Mohs: the gold standard. The Skin Cancer Foundation website. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.skincancer.org/treatment-resources/mohs-surgery/mohs-the-gold-standard/

- van Delft LCJ, Nelemans PJ, van Loo E, et al. The illusion of conventional histological resection margin control. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1240-1241. doi:10.1111/bjd.17510

- Warne MM, Klawonn MM, Brodell RT. Bread loaf sections provide useful information on more than 0.5% of surgical margins [published July 5, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.21740

- Mehrany K, Weenig RH, Pittelkow MR, et al. High recurrence rates of basal cell carcinoma after Mohs surgery in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:985-988. doi:10.1001/archderm.140.8.985

- Smeets NWJ, Krekels GAM, Ostertag JU, et al. Surgical excision vs Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1766-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17399-6

- Gulleth Y, Goldberg N, Silverman RP, et al. What is the best surgical margin for a basal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of theliterature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1222-1231. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea450d

- Nahhas AF, Scarbrough CA, Trotter S. A review of the global guidelines on surgical margins for nonmelanoma skin cancers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:37-46.

- Rapini RP. Comparison of methods for checking surgical margins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990; 23:288-294. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70212-z

We have attended grand rounds presentations at which students announce that Mohs micrographic surgery evaluates 100% of the surgical margin, whereas standard excision samples 1% to 2% of the margin; we have even fielded questions from neighbors who have come across this information on the internet.1-5 This statement describes a best-case scenario for Mohs surgery and a worst-case scenario for standard excision. We believe that it is important for clinicians to have a more nuanced understanding of how simple excisions are processed so that they can have pertinent discussions with patients, especially now that there is increasing access to personal health information along with increased agency in patient decision-making.

Margins for Mohs Surgery

Theoretically, Mohs surgery should sample all true surgical margins by complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep-margin assessment. Unfortunately, some sections are not cut full face—sections may not always sample a complete surface—when technicians make an error or lack expertise. Some sections may have small tissue folds or small gaps that prevent complete visualization. We estimate that the Mohs sections we review in consultation that are prepared by private practice Mohs surgeons in our communities visualize approximately 98% of surgical margins on average. Incomplete sections contribute to the rare tumor recurrences after Mohs surgery of approximately 2% to 3%.6

Standard Excision Margins

When we obtained the references cited in articles asserting that

Here is a simple example to show that more margin is accessed in some cases. Consider this hypothetical situation: If a tumor can be readily visualized grossly and housed entirely within an imaginary cuboid (rectangular) prism that is removed in an elliptical specimen with a length of 6 cm, a width of 2 cm, and a height of 1 cm (Figure), then standard sectioning assesses a greater margin.

Bread-loaf sectioning would be expected to examine the complete surface of 2 sides (faces) of the cuboid. Assessing 2 of the 5 clinically relevant sides provides information for approximately 50% of the margins, as sections in the next parallel plane can be expected to be clear after the first clear section is identified. The clinically useful information is not limited to the sum of the widths of sections. Encountering a clear plane typically indicates that there will be no tumor in more distal parallel planes. Warne et al6 developed a formula that can accurately predict the percentage of the margin evaluated by proxy that considers the curvature of the ellipse.

Comparing Standard Excision and Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery consistently results in the best outcomes, but standard excision is effective, too. Standard excision is relatively simple, requires less equipment, is less time consuming, and can provide good value when resources are finite. Data on recurrence of basal cell carcinoma after simple excision are limited, but the recurrence rate is reported to be approximately 3%.7,8 A meta-analysis found that the recurrence rate of basal cell carcinoma treated with standard excision was 0.4%, 1.6%, 2.6%, and 4% with 5-mm, 4-mm, 3-mm, and 2-mm surgical margins, respectively.9

Mohs surgery is the best, most effective, and most tissue-sparing technique for certain nonmelanoma skin cancers. This observation is reflected in guidelines worldwide.10 The adequacy of standard approaches to margin evaluation depends on the capabilities and focus of the laboratory team. Dermatopathologists often are called to the laboratory to decide which technique will be best for a particular case.11 Technicians are trained to take more sections in areas where abnormalities are seen, and some laboratories take photographs of specimens or provide sketches for correlation. Dermatopathologists also routinely request additional sections in areas where visible tumor extends close to surgical margins on microscopic examination.

It is not simply a matter of knowing how much of the margin is sampled but if the most pertinent areas are adequately sampled. Simple sectioning can work well and be cost effective. Many clinicians are unaware of how tissue processing can vary from laboratory to laboratory. There are no uniformly accepted standards for how tissue should be processed. Assiduous and thoughtful evaluation of specimens can affect results. As with any service, some laboratories provide more detailed and conscientious care while others focus more on immediate costs. Clinicians should understand how their specimens are processed by discussing margin evaluation with their dermatopathologist.

Final Thoughts

Used appropriately, Mohs surgery is an excellent technique that can provide outstanding results. Standard excision also has an important place in the dermatologist’s armamentarium and typically provides information about more than 1% to 2% of the margin. Understanding the techniques used to process specimens is critical to delivering the best possible care.

We have attended grand rounds presentations at which students announce that Mohs micrographic surgery evaluates 100% of the surgical margin, whereas standard excision samples 1% to 2% of the margin; we have even fielded questions from neighbors who have come across this information on the internet.1-5 This statement describes a best-case scenario for Mohs surgery and a worst-case scenario for standard excision. We believe that it is important for clinicians to have a more nuanced understanding of how simple excisions are processed so that they can have pertinent discussions with patients, especially now that there is increasing access to personal health information along with increased agency in patient decision-making.

Margins for Mohs Surgery

Theoretically, Mohs surgery should sample all true surgical margins by complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep-margin assessment. Unfortunately, some sections are not cut full face—sections may not always sample a complete surface—when technicians make an error or lack expertise. Some sections may have small tissue folds or small gaps that prevent complete visualization. We estimate that the Mohs sections we review in consultation that are prepared by private practice Mohs surgeons in our communities visualize approximately 98% of surgical margins on average. Incomplete sections contribute to the rare tumor recurrences after Mohs surgery of approximately 2% to 3%.6

Standard Excision Margins

When we obtained the references cited in articles asserting that

Here is a simple example to show that more margin is accessed in some cases. Consider this hypothetical situation: If a tumor can be readily visualized grossly and housed entirely within an imaginary cuboid (rectangular) prism that is removed in an elliptical specimen with a length of 6 cm, a width of 2 cm, and a height of 1 cm (Figure), then standard sectioning assesses a greater margin.

Bread-loaf sectioning would be expected to examine the complete surface of 2 sides (faces) of the cuboid. Assessing 2 of the 5 clinically relevant sides provides information for approximately 50% of the margins, as sections in the next parallel plane can be expected to be clear after the first clear section is identified. The clinically useful information is not limited to the sum of the widths of sections. Encountering a clear plane typically indicates that there will be no tumor in more distal parallel planes. Warne et al6 developed a formula that can accurately predict the percentage of the margin evaluated by proxy that considers the curvature of the ellipse.

Comparing Standard Excision and Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery consistently results in the best outcomes, but standard excision is effective, too. Standard excision is relatively simple, requires less equipment, is less time consuming, and can provide good value when resources are finite. Data on recurrence of basal cell carcinoma after simple excision are limited, but the recurrence rate is reported to be approximately 3%.7,8 A meta-analysis found that the recurrence rate of basal cell carcinoma treated with standard excision was 0.4%, 1.6%, 2.6%, and 4% with 5-mm, 4-mm, 3-mm, and 2-mm surgical margins, respectively.9

Mohs surgery is the best, most effective, and most tissue-sparing technique for certain nonmelanoma skin cancers. This observation is reflected in guidelines worldwide.10 The adequacy of standard approaches to margin evaluation depends on the capabilities and focus of the laboratory team. Dermatopathologists often are called to the laboratory to decide which technique will be best for a particular case.11 Technicians are trained to take more sections in areas where abnormalities are seen, and some laboratories take photographs of specimens or provide sketches for correlation. Dermatopathologists also routinely request additional sections in areas where visible tumor extends close to surgical margins on microscopic examination.

It is not simply a matter of knowing how much of the margin is sampled but if the most pertinent areas are adequately sampled. Simple sectioning can work well and be cost effective. Many clinicians are unaware of how tissue processing can vary from laboratory to laboratory. There are no uniformly accepted standards for how tissue should be processed. Assiduous and thoughtful evaluation of specimens can affect results. As with any service, some laboratories provide more detailed and conscientious care while others focus more on immediate costs. Clinicians should understand how their specimens are processed by discussing margin evaluation with their dermatopathologist.

Final Thoughts

Used appropriately, Mohs surgery is an excellent technique that can provide outstanding results. Standard excision also has an important place in the dermatologist’s armamentarium and typically provides information about more than 1% to 2% of the margin. Understanding the techniques used to process specimens is critical to delivering the best possible care.

- Tolkachjov SN, Brodland DG, Coldiron BM, et al. Understanding Mohs micrographic surgery: a review and practical guide for the nondermatologist. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1261-1271. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.009

- Thomas RM, Amonette RA. Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician. 1988;37:135-142.

- Buker JL, Amonette RA. Micrographic surgery. Clin Dermatol. 1992:10:309-315. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(92)90074-9

- Kauvar ANB. Mohs: the gold standard. The Skin Cancer Foundation website. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.skincancer.org/treatment-resources/mohs-surgery/mohs-the-gold-standard/

- van Delft LCJ, Nelemans PJ, van Loo E, et al. The illusion of conventional histological resection margin control. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1240-1241. doi:10.1111/bjd.17510

- Warne MM, Klawonn MM, Brodell RT. Bread loaf sections provide useful information on more than 0.5% of surgical margins [published July 5, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.21740

- Mehrany K, Weenig RH, Pittelkow MR, et al. High recurrence rates of basal cell carcinoma after Mohs surgery in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:985-988. doi:10.1001/archderm.140.8.985

- Smeets NWJ, Krekels GAM, Ostertag JU, et al. Surgical excision vs Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1766-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17399-6

- Gulleth Y, Goldberg N, Silverman RP, et al. What is the best surgical margin for a basal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of theliterature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1222-1231. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea450d

- Nahhas AF, Scarbrough CA, Trotter S. A review of the global guidelines on surgical margins for nonmelanoma skin cancers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:37-46.

- Rapini RP. Comparison of methods for checking surgical margins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990; 23:288-294. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70212-z

- Tolkachjov SN, Brodland DG, Coldiron BM, et al. Understanding Mohs micrographic surgery: a review and practical guide for the nondermatologist. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1261-1271. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.009

- Thomas RM, Amonette RA. Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician. 1988;37:135-142.

- Buker JL, Amonette RA. Micrographic surgery. Clin Dermatol. 1992:10:309-315. doi:10.1016/0738-081x(92)90074-9

- Kauvar ANB. Mohs: the gold standard. The Skin Cancer Foundation website. Updated March 9, 2021. Accessed June 15, 2022. https://www.skincancer.org/treatment-resources/mohs-surgery/mohs-the-gold-standard/

- van Delft LCJ, Nelemans PJ, van Loo E, et al. The illusion of conventional histological resection margin control. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:1240-1241. doi:10.1111/bjd.17510

- Warne MM, Klawonn MM, Brodell RT. Bread loaf sections provide useful information on more than 0.5% of surgical margins [published July 5, 2022]. Br J Dermatol. doi:10.1111/bjd.21740

- Mehrany K, Weenig RH, Pittelkow MR, et al. High recurrence rates of basal cell carcinoma after Mohs surgery in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:985-988. doi:10.1001/archderm.140.8.985

- Smeets NWJ, Krekels GAM, Ostertag JU, et al. Surgical excision vs Mohs’ micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1766-1772. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17399-6

- Gulleth Y, Goldberg N, Silverman RP, et al. What is the best surgical margin for a basal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of theliterature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1222-1231. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea450d

- Nahhas AF, Scarbrough CA, Trotter S. A review of the global guidelines on surgical margins for nonmelanoma skin cancers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:37-46.

- Rapini RP. Comparison of methods for checking surgical margins. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990; 23:288-294. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70212-z

Practice Points

- Margin analysis in simple excisions can provide useful information by proxy about more than the 1% of the margin often quoted in the literature.

- Simple excisions of uncomplicated keratinocytic carcinomas are associated with high cure rates.

Rapid Onset of Widespread Nodules and Lymphadenopathy

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous γδ T-cell Lymphoma

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTL) is a distinct entity that can be confused with other types of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Often rapidly fatal, PCGDTL has a broad clinical spectrum that may include indolent variants—subcutaneous, epidermotropic, and dermal.1 Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma represents less than 1% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2 Diagnosis and treatment remain challenging. Patients typically present with nodular lesions that progress to ulceration and necrosis. Early lesions can be confused with erythema nodosum, mycosis fungoides, or infection on clinical examination; biopsy establishes the diagnosis. Typical findings include a cytotoxic phenotype, variable epidermotropism, dermal and subcutaneous involvement, and loss of CD4 and often CD8 expression. Testing for Epstein-Barr virus expression yields negative results. The neoplastic lymphocytes in dermal and subcutaneous PCGDTL typically are T-cell intracellular antigen-1 (TIA-1) and granzyme positive.1

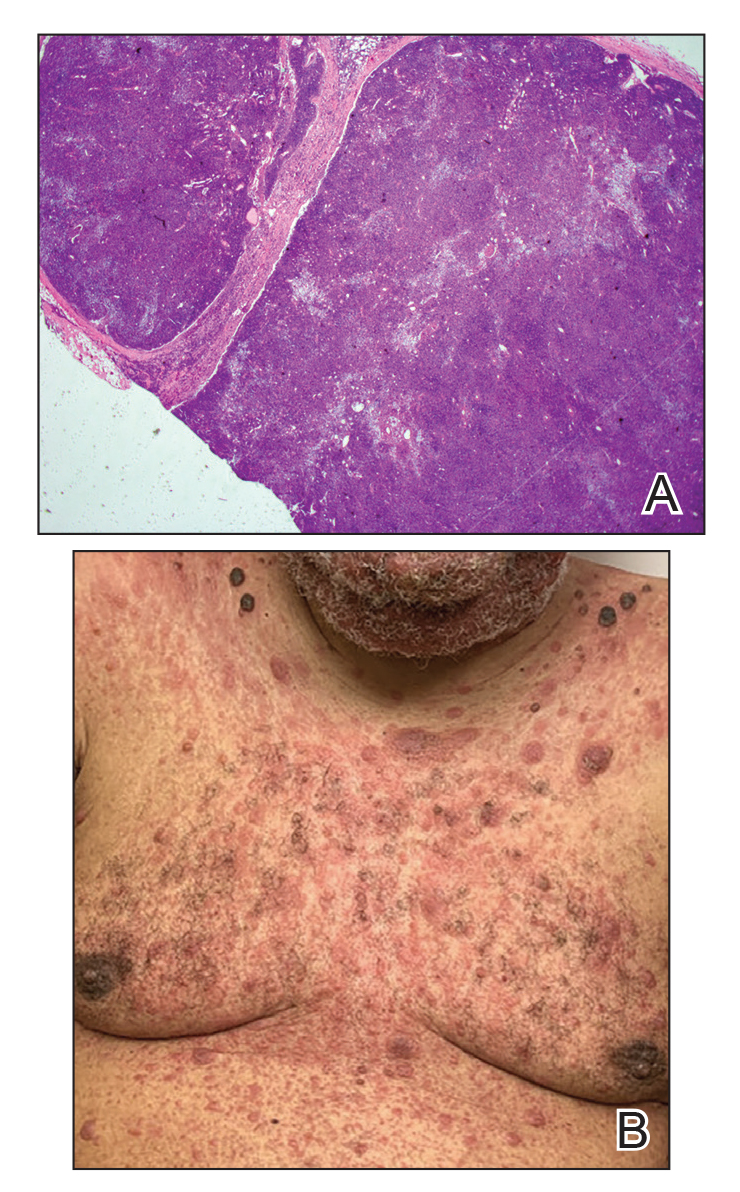

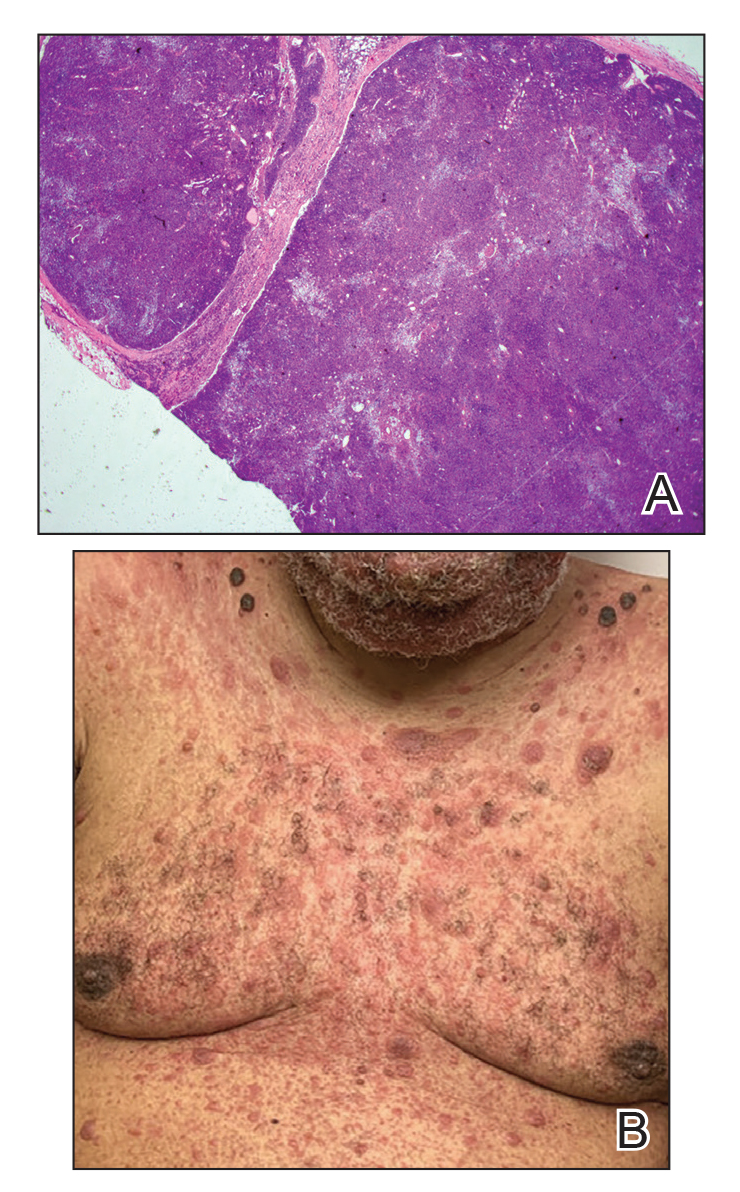

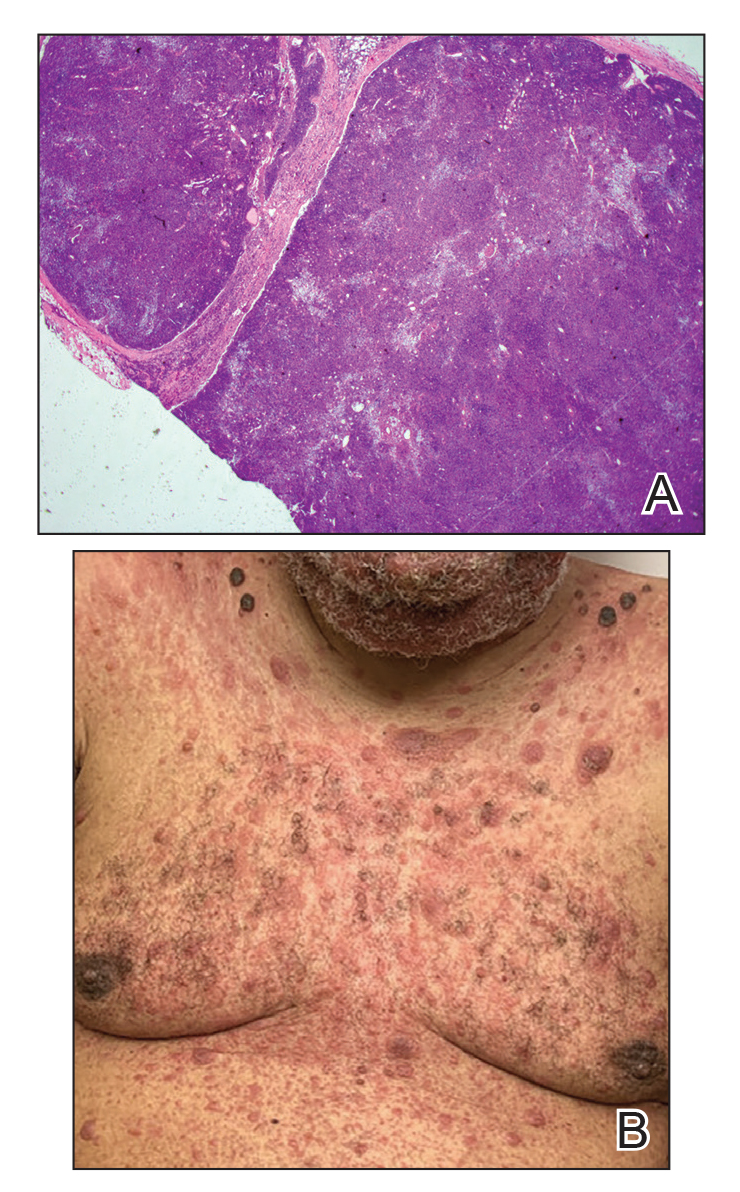

Immunohistochemistry failed to reveal CD8, CD56, granzyme, or T-cell intracellular antigen-1 staining of neoplastic cells in our patient but stained diffusely positive with CD3 and CD4. A CD20 stain decorated only a few dermal cells. The patient’s skin lesions continued to enlarge, and the massive lymphadenopathy made breathing difficult. Computed tomography revealed diffuse systemic involvement. An axillary lymph node biopsy revealed sinusoids with complete diffuse effacement of architecture as well as frequent mitotic figures and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 1A). Negative staining for T-cell receptor beta-F1 of the axillary lymph node biopsy and clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma chain supported the diagnosis of PCGDTL. Nuclear staining for Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA was negative. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 antibodies and polymerase chain reaction also were negative. Flow cytometry demonstrated an atypical population of CD3+, CD4+, and CD7− γδ T lymphocytes, further supporting the diagnosis of lymphoma.

The median life expectancy for patients with dermal or subcutaneous PCGDTL is 10 to 15 months after diagnosis.3 The 5-year life expectancy for PCGDTL is approximately 11%.2 Limited treatment options contribute to the poor outcome. Chemotherapy regimens such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) and EPOCH (etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) have yielded inconsistent results. Stem cell transplant has been tried in progressive disease and also has yielded mixed results.2 Brentuximab is indicated for individuals whose tumors express CD30.4 Associated hemophagic lymphohistiocytosis portends a poor prognosis.5

Despite treatment with etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and high-dose oral steroids, our patient developed progressive difficulty breathing, stridor, kidney injury, and anemia. Our patient died less than 1 month after diagnosis—after only 1 round of chemotherapy—secondary to progressive disease and an uncontrollable gastrointestinal tract bleed. The leonine facies (Figure 1B) encountered in our patient can raise a differential diagnosis that includes infectious as well as neoplastic etiologies; however, most infectious etiologies associated with leonine facies manifest in a chronic fashion rather than with a sudden eruption, as noted in our patient.

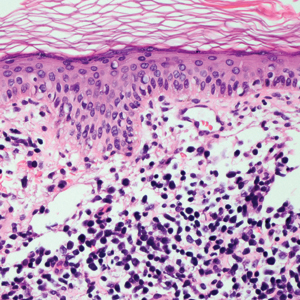

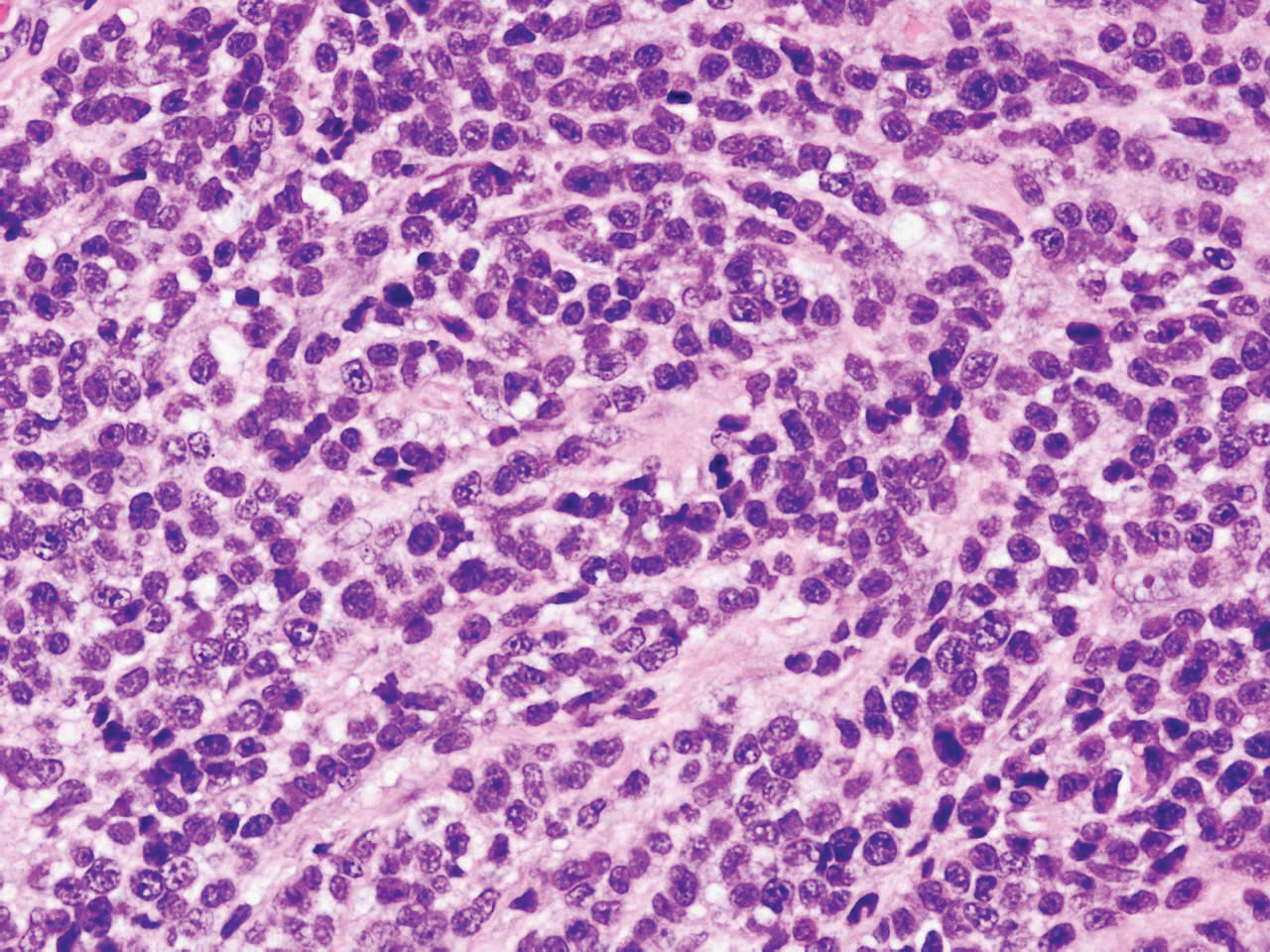

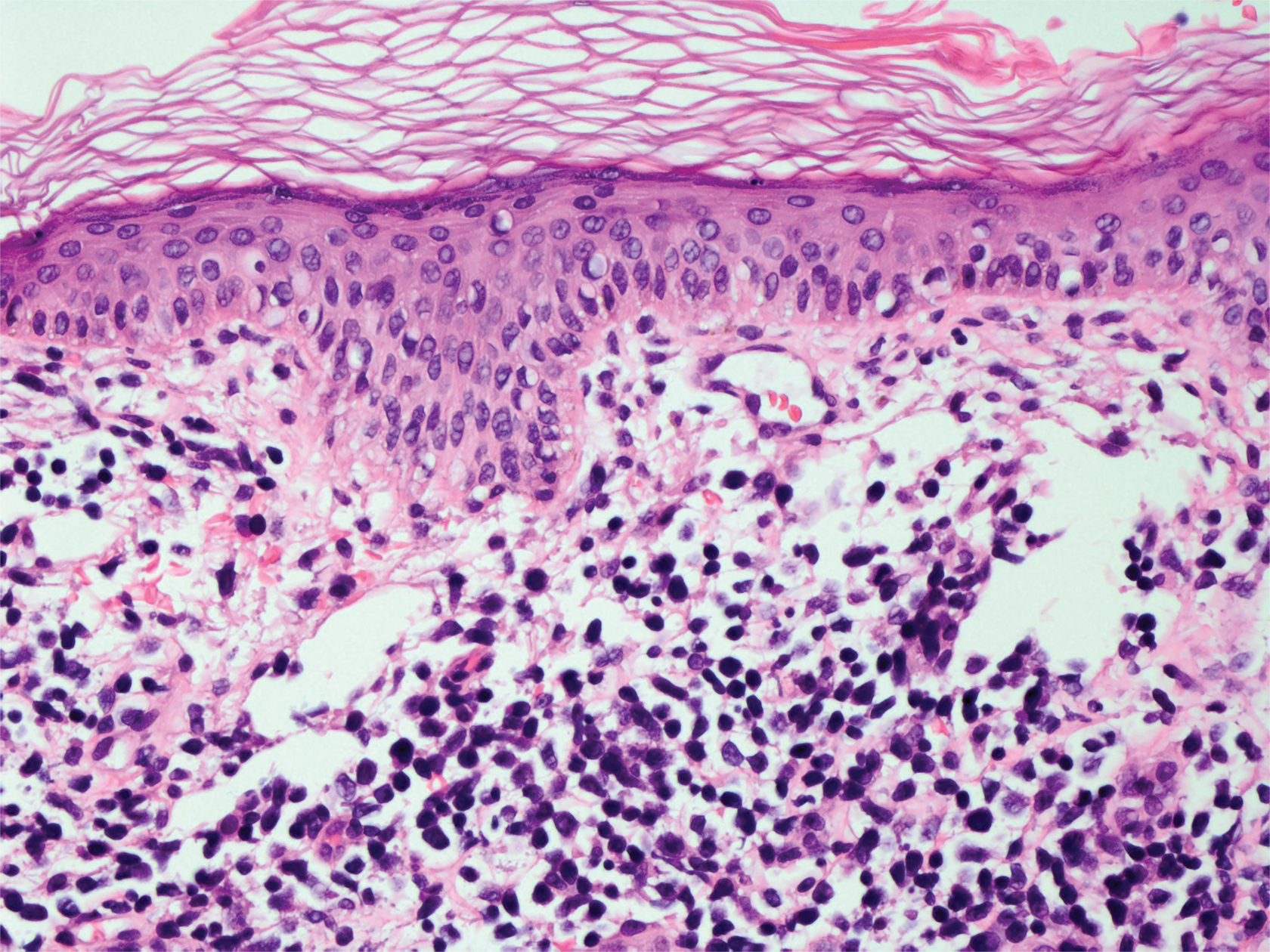

Leprosy is caused by Mycobacterium leprae, a grampositive bacillus. The condition manifests across a spectrum, with the poles being tuberculoid and lepromatous, and borderline variants in between.6-8 Lepromatous leprosy arises in individuals who are unable to mount cellular immunity against M leprae secondary to anergy.6 Lepromatous leprosy often presents with numerous papules and nodules. Aside from cutaneous manifestations, lepromatous leprosy has a predilection for peripheral nerves and specifically Schwann cells. Histologically, biopsy reveals a flat epidermis and a cell-free subepidermal grenz zone. Within the dermis, there is a diffuse histiocytic infiltrate that typically is not centered around nerves (Figure 2).6,7 Mycobacterium leprae can appear scattered throughout or clustered in globi. Mycobacterium leprae stains red with Ziehl-Neelsen or Wade-Fite stains.6,7 Immunohistochemistry reveals a CD4+ helper T cell (TH2) predominance, supported by the increased expression of type 2 reaction cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13.8

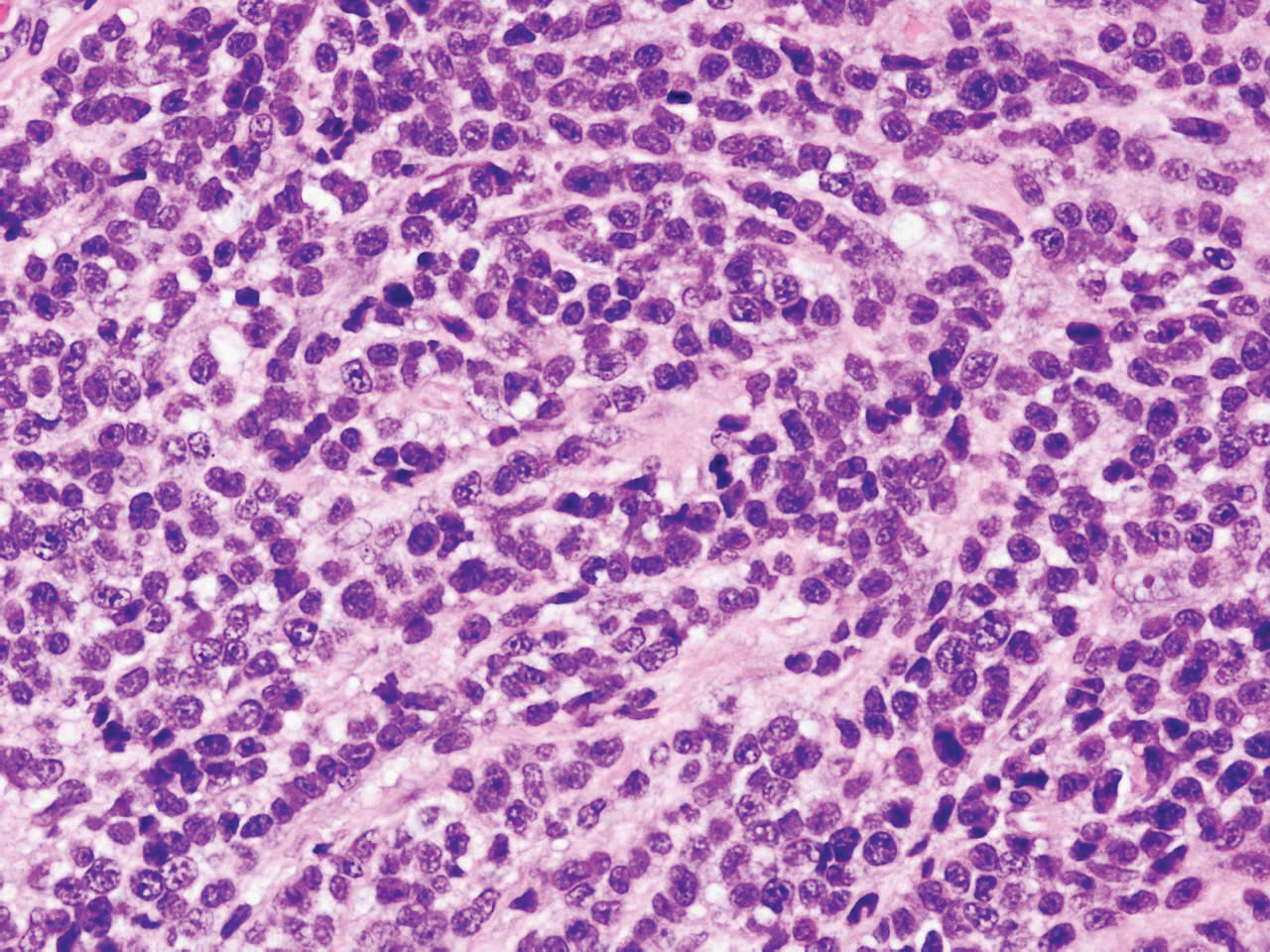

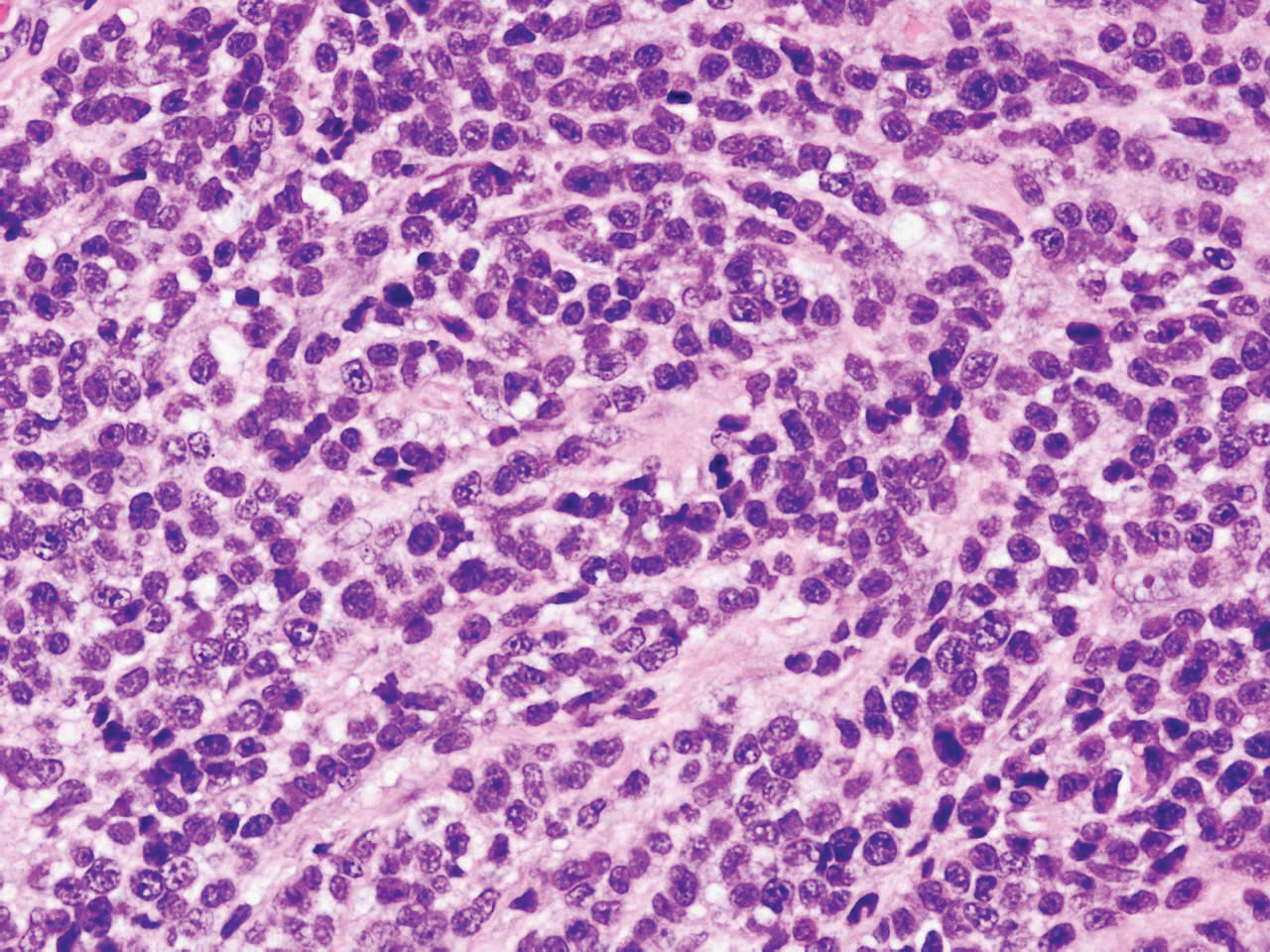

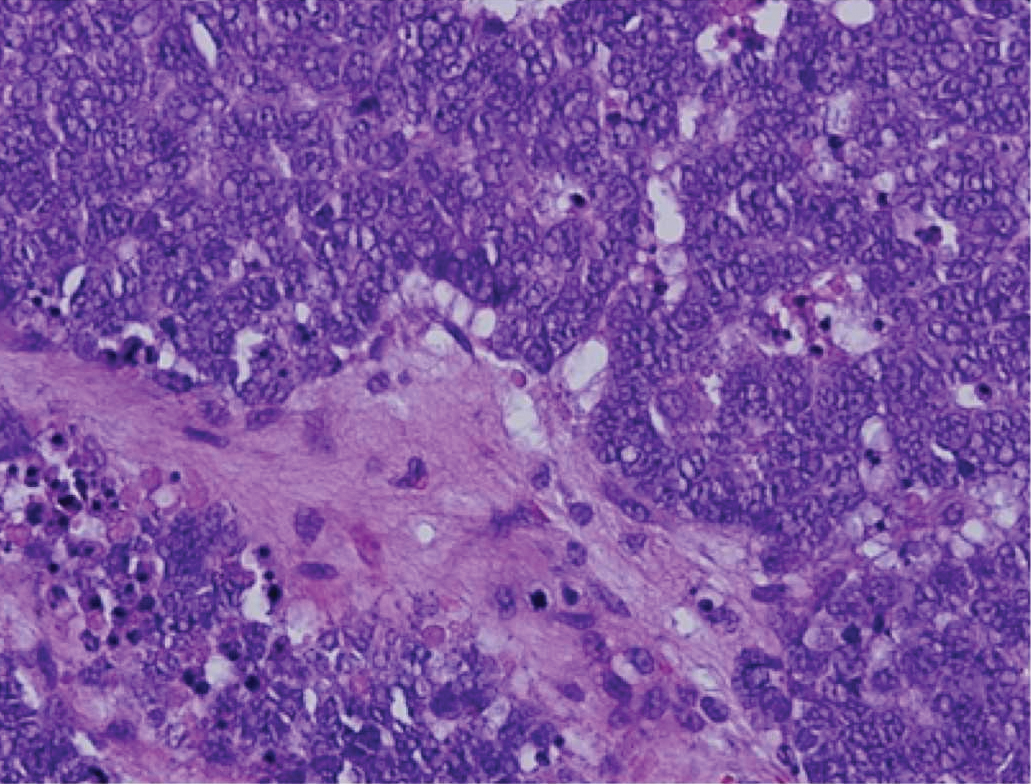

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) embodies 10% to 20% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas; it is more prevalent in older adults (age range, 70–82 years) and women. Clinically, DLBCL presents as either single or multiple rapidly progressing nodules or plaques, usually violaceous or blue-red in color.9,10 The most common area of presentation is on the legs, though it also can surface at other sites.9 On histology, DLBCL has clearly malignant features including frequent mitotic figures, large immunoblasts, and involvement throughout the dermis as well as perivascularly (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped cells and anaplastic features can be present. Immunohistochemically, DLBCL stains strongly positive for CD20 and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) along with other pan–B-cell markers.9-11 The aggressive leg type of DLBCL stains positively for multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1).9,11

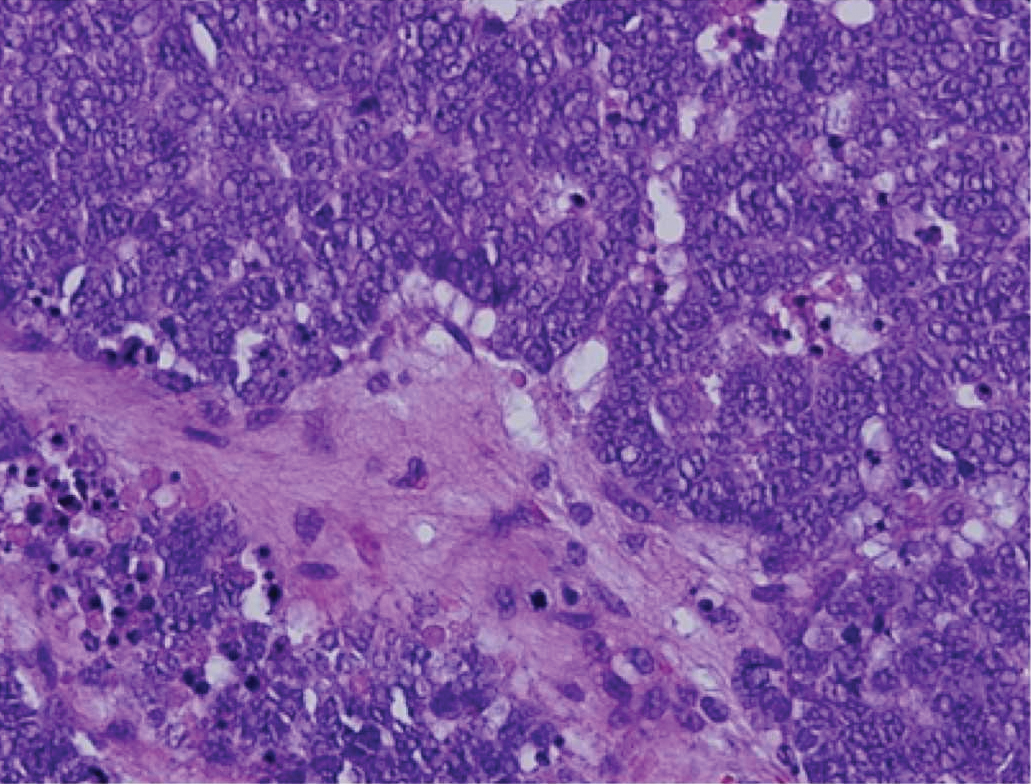

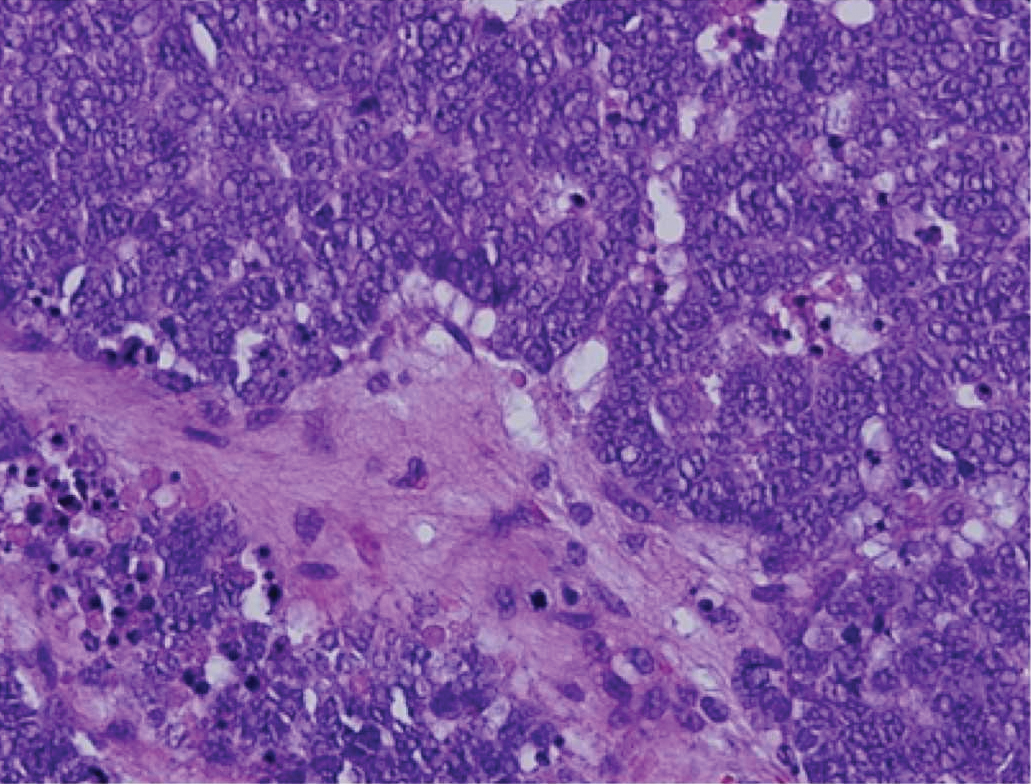

Cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinoma from internal malignancies occurs in approximately 5% of cancer patients with metastatic spread.12 Most of these cutaneous lesions develop in close proximity to the primary tumor such as on the trunk, head, or neck. All cutaneous metastases carry a poor prognosis. Clinical presentation can vary greatly, ranging from painless, firm, or elastic nodules to lesions that mimic inflammatory skin conditions such as erysipelas or scleroderma. The majority of these metastases develop as painless firm nodules that are flesh colored, pink, red-brown, or purple.12,13 The histopathology of metastatic adenocarcinoma demonstrates an infiltrative nodular appearance, though there rarely are well-circumscribed nodules found.13 The lesion originates in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. It is a glandulartype lesion that may reflect the tissue of the primary tumor (Figure 4).12,14 Immunohistochemical stains likely will remain consistent with those of the primary tumor, which is not always the case.14

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive cutaneous malignancy of epithelial and neuroendocrine origin, first described as trabecular carcinoma due to the arrangement of tumor resembling cancellous bone.15,16 Merkel cells are mechanoreceptors found near nerve terminals.17 Approximately 80% of MCCs are associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus, which is a small, double-stranded DNA virus with an icosahedral capsid.17,18 Merkel cell polyomavirus–positive cases of MCC tend to have a better prognosis. In Merkel cell polyomavirus–negative MCC, there is an association with UV damage and increased chromosomal aberrations.18 Merkel cell carcinoma is known for its high rate of recurrence as well as local and distant metastasis. Nodal involvement is the most important prognostic indicator.15 Clinically, MCC is associated with the AEIOU mnemonic (asymptomatic, expanding rapidly, immunosuppression, older than 50 years, UV exposed/fair skin).15-17 Lesions appear as red-blue papules on sun-exposed skin and usually are smaller than 2 cm by their greatest dimension. On histopathology, MCC demonstrates small, round, blue cells arranged in sheets or nests originating in the dermis and occasionally can infiltrate the subcutis and lymphovascular surroundings (Figure 5).16-19 Cells have scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may have fine granular chromatin. Numerous mitotic figures and apoptotic cells also are present. On immunohistochemistry, these cells will stain positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), CK20, and CD56. Due to their neuroendocrine derivation, they also are commonly synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, and chromogranin A positive. Notably, MCC will stain negative for leukocyte common antigen, CD20, CD3, CD34, and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1).16,17

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma can be difficult to diagnose and requires urgent treatment. Clinicians and dermatopathologists need to work together to establish the diagnosis. There is a high mortality rate associated with PCGDTL, making prompt recognition and timely treatment critical. Acknowledgments—Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

- Merrill ED, Agbay R, Miranda RN, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas showing gamma-delta (γδ) phenotype and predominantly epidermotropic pattern are clinicopathologically distinct from classic primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:204-215.

- Foppoli M, Ferreri AJ. Gamma‐delta T‐cell lymphomas. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:206-218.

- Toro JR, Liewehr DJ, Pabby N, et al. Gamma-delta T-cell phenotype is associated with significantly decreased survival in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:3407-3412.

- Rubio-Gonzalez B, Zain J, Garcia L, et al. Cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma successfully treated with brentuximab vedotin. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388-1390.

- Tong H, Ren Y, Liu H, et al. Clinical characteristics of T-cell lymphoma associated with hemophagocytic syndrome: comparison of T-cell lymphoma with and without hemophagocytic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:81-87.

- Brehmer-Andersson E. Leprosy. Dermatopathology. New York, NY: Springer; 2006:110-113.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Naafs B, Noto S. Reactions in leprosy. In: Nunzi E, Massone C, eds. Leprosy: A Practical Guide. Milan, Italy: Springer; 2012:219-239.

- Hope CB, Pincus LB. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:547-574.

- Billero VL, LaSenna CE, Romanelli M, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting as chronic non-healing ulcer. Int Wound J. 2017;14:830-832.

- Testo N, Olson L, Subramaniyam S, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a MYC-IGH rearrangement and gain of BCL2: expanding the spectrum of MYC/BCL2 double hit lymphomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:769-774.

- Boyd AS. Pulmonary signet-ring cell adenocarcinoma metastatic to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:E66-E68.

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:758-761.

- Trinidad CM, Torres-Cabala CA, Prieto VG, et. Al. Update on eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer classification for Merkel Cell carcinoma and histopathological parameters that determine prognosis. J Clin Pathol. 2017;72:337-340.

- Bandino JP, Purvis CG, Shaffer BR, et al. A comparison of the histopathologic growth patterns between non-Merkel cell small round blue cell tumors and Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:815-818.

- Mauzo SH, Rerrarotto R, Bell D, et al. Molecular characteristics and potential therapeutic targets in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:382-390.

- Lowe G, Brewer J, Bordeaux J. Epidemiology and genetics. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:26-28.

- North J, McCalmont T. Histopathologic diagnosis. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:66-69.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous γδ T-cell Lymphoma

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTL) is a distinct entity that can be confused with other types of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Often rapidly fatal, PCGDTL has a broad clinical spectrum that may include indolent variants—subcutaneous, epidermotropic, and dermal.1 Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma represents less than 1% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2 Diagnosis and treatment remain challenging. Patients typically present with nodular lesions that progress to ulceration and necrosis. Early lesions can be confused with erythema nodosum, mycosis fungoides, or infection on clinical examination; biopsy establishes the diagnosis. Typical findings include a cytotoxic phenotype, variable epidermotropism, dermal and subcutaneous involvement, and loss of CD4 and often CD8 expression. Testing for Epstein-Barr virus expression yields negative results. The neoplastic lymphocytes in dermal and subcutaneous PCGDTL typically are T-cell intracellular antigen-1 (TIA-1) and granzyme positive.1

Immunohistochemistry failed to reveal CD8, CD56, granzyme, or T-cell intracellular antigen-1 staining of neoplastic cells in our patient but stained diffusely positive with CD3 and CD4. A CD20 stain decorated only a few dermal cells. The patient’s skin lesions continued to enlarge, and the massive lymphadenopathy made breathing difficult. Computed tomography revealed diffuse systemic involvement. An axillary lymph node biopsy revealed sinusoids with complete diffuse effacement of architecture as well as frequent mitotic figures and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 1A). Negative staining for T-cell receptor beta-F1 of the axillary lymph node biopsy and clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma chain supported the diagnosis of PCGDTL. Nuclear staining for Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA was negative. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 antibodies and polymerase chain reaction also were negative. Flow cytometry demonstrated an atypical population of CD3+, CD4+, and CD7− γδ T lymphocytes, further supporting the diagnosis of lymphoma.

The median life expectancy for patients with dermal or subcutaneous PCGDTL is 10 to 15 months after diagnosis.3 The 5-year life expectancy for PCGDTL is approximately 11%.2 Limited treatment options contribute to the poor outcome. Chemotherapy regimens such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) and EPOCH (etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) have yielded inconsistent results. Stem cell transplant has been tried in progressive disease and also has yielded mixed results.2 Brentuximab is indicated for individuals whose tumors express CD30.4 Associated hemophagic lymphohistiocytosis portends a poor prognosis.5

Despite treatment with etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and high-dose oral steroids, our patient developed progressive difficulty breathing, stridor, kidney injury, and anemia. Our patient died less than 1 month after diagnosis—after only 1 round of chemotherapy—secondary to progressive disease and an uncontrollable gastrointestinal tract bleed. The leonine facies (Figure 1B) encountered in our patient can raise a differential diagnosis that includes infectious as well as neoplastic etiologies; however, most infectious etiologies associated with leonine facies manifest in a chronic fashion rather than with a sudden eruption, as noted in our patient.

Leprosy is caused by Mycobacterium leprae, a grampositive bacillus. The condition manifests across a spectrum, with the poles being tuberculoid and lepromatous, and borderline variants in between.6-8 Lepromatous leprosy arises in individuals who are unable to mount cellular immunity against M leprae secondary to anergy.6 Lepromatous leprosy often presents with numerous papules and nodules. Aside from cutaneous manifestations, lepromatous leprosy has a predilection for peripheral nerves and specifically Schwann cells. Histologically, biopsy reveals a flat epidermis and a cell-free subepidermal grenz zone. Within the dermis, there is a diffuse histiocytic infiltrate that typically is not centered around nerves (Figure 2).6,7 Mycobacterium leprae can appear scattered throughout or clustered in globi. Mycobacterium leprae stains red with Ziehl-Neelsen or Wade-Fite stains.6,7 Immunohistochemistry reveals a CD4+ helper T cell (TH2) predominance, supported by the increased expression of type 2 reaction cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13.8

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) embodies 10% to 20% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas; it is more prevalent in older adults (age range, 70–82 years) and women. Clinically, DLBCL presents as either single or multiple rapidly progressing nodules or plaques, usually violaceous or blue-red in color.9,10 The most common area of presentation is on the legs, though it also can surface at other sites.9 On histology, DLBCL has clearly malignant features including frequent mitotic figures, large immunoblasts, and involvement throughout the dermis as well as perivascularly (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped cells and anaplastic features can be present. Immunohistochemically, DLBCL stains strongly positive for CD20 and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) along with other pan–B-cell markers.9-11 The aggressive leg type of DLBCL stains positively for multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1).9,11

Cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinoma from internal malignancies occurs in approximately 5% of cancer patients with metastatic spread.12 Most of these cutaneous lesions develop in close proximity to the primary tumor such as on the trunk, head, or neck. All cutaneous metastases carry a poor prognosis. Clinical presentation can vary greatly, ranging from painless, firm, or elastic nodules to lesions that mimic inflammatory skin conditions such as erysipelas or scleroderma. The majority of these metastases develop as painless firm nodules that are flesh colored, pink, red-brown, or purple.12,13 The histopathology of metastatic adenocarcinoma demonstrates an infiltrative nodular appearance, though there rarely are well-circumscribed nodules found.13 The lesion originates in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. It is a glandulartype lesion that may reflect the tissue of the primary tumor (Figure 4).12,14 Immunohistochemical stains likely will remain consistent with those of the primary tumor, which is not always the case.14

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive cutaneous malignancy of epithelial and neuroendocrine origin, first described as trabecular carcinoma due to the arrangement of tumor resembling cancellous bone.15,16 Merkel cells are mechanoreceptors found near nerve terminals.17 Approximately 80% of MCCs are associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus, which is a small, double-stranded DNA virus with an icosahedral capsid.17,18 Merkel cell polyomavirus–positive cases of MCC tend to have a better prognosis. In Merkel cell polyomavirus–negative MCC, there is an association with UV damage and increased chromosomal aberrations.18 Merkel cell carcinoma is known for its high rate of recurrence as well as local and distant metastasis. Nodal involvement is the most important prognostic indicator.15 Clinically, MCC is associated with the AEIOU mnemonic (asymptomatic, expanding rapidly, immunosuppression, older than 50 years, UV exposed/fair skin).15-17 Lesions appear as red-blue papules on sun-exposed skin and usually are smaller than 2 cm by their greatest dimension. On histopathology, MCC demonstrates small, round, blue cells arranged in sheets or nests originating in the dermis and occasionally can infiltrate the subcutis and lymphovascular surroundings (Figure 5).16-19 Cells have scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may have fine granular chromatin. Numerous mitotic figures and apoptotic cells also are present. On immunohistochemistry, these cells will stain positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), CK20, and CD56. Due to their neuroendocrine derivation, they also are commonly synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, and chromogranin A positive. Notably, MCC will stain negative for leukocyte common antigen, CD20, CD3, CD34, and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1).16,17

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma can be difficult to diagnose and requires urgent treatment. Clinicians and dermatopathologists need to work together to establish the diagnosis. There is a high mortality rate associated with PCGDTL, making prompt recognition and timely treatment critical. Acknowledgments—Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous γδ T-cell Lymphoma

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma (PCGDTL) is a distinct entity that can be confused with other types of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Often rapidly fatal, PCGDTL has a broad clinical spectrum that may include indolent variants—subcutaneous, epidermotropic, and dermal.1 Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma represents less than 1% of all cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.2 Diagnosis and treatment remain challenging. Patients typically present with nodular lesions that progress to ulceration and necrosis. Early lesions can be confused with erythema nodosum, mycosis fungoides, or infection on clinical examination; biopsy establishes the diagnosis. Typical findings include a cytotoxic phenotype, variable epidermotropism, dermal and subcutaneous involvement, and loss of CD4 and often CD8 expression. Testing for Epstein-Barr virus expression yields negative results. The neoplastic lymphocytes in dermal and subcutaneous PCGDTL typically are T-cell intracellular antigen-1 (TIA-1) and granzyme positive.1

Immunohistochemistry failed to reveal CD8, CD56, granzyme, or T-cell intracellular antigen-1 staining of neoplastic cells in our patient but stained diffusely positive with CD3 and CD4. A CD20 stain decorated only a few dermal cells. The patient’s skin lesions continued to enlarge, and the massive lymphadenopathy made breathing difficult. Computed tomography revealed diffuse systemic involvement. An axillary lymph node biopsy revealed sinusoids with complete diffuse effacement of architecture as well as frequent mitotic figures and karyorrhectic debris (Figure 1A). Negative staining for T-cell receptor beta-F1 of the axillary lymph node biopsy and clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gamma chain supported the diagnosis of PCGDTL. Nuclear staining for Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA was negative. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 antibodies and polymerase chain reaction also were negative. Flow cytometry demonstrated an atypical population of CD3+, CD4+, and CD7− γδ T lymphocytes, further supporting the diagnosis of lymphoma.

The median life expectancy for patients with dermal or subcutaneous PCGDTL is 10 to 15 months after diagnosis.3 The 5-year life expectancy for PCGDTL is approximately 11%.2 Limited treatment options contribute to the poor outcome. Chemotherapy regimens such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) and EPOCH (etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) have yielded inconsistent results. Stem cell transplant has been tried in progressive disease and also has yielded mixed results.2 Brentuximab is indicated for individuals whose tumors express CD30.4 Associated hemophagic lymphohistiocytosis portends a poor prognosis.5

Despite treatment with etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and high-dose oral steroids, our patient developed progressive difficulty breathing, stridor, kidney injury, and anemia. Our patient died less than 1 month after diagnosis—after only 1 round of chemotherapy—secondary to progressive disease and an uncontrollable gastrointestinal tract bleed. The leonine facies (Figure 1B) encountered in our patient can raise a differential diagnosis that includes infectious as well as neoplastic etiologies; however, most infectious etiologies associated with leonine facies manifest in a chronic fashion rather than with a sudden eruption, as noted in our patient.

Leprosy is caused by Mycobacterium leprae, a grampositive bacillus. The condition manifests across a spectrum, with the poles being tuberculoid and lepromatous, and borderline variants in between.6-8 Lepromatous leprosy arises in individuals who are unable to mount cellular immunity against M leprae secondary to anergy.6 Lepromatous leprosy often presents with numerous papules and nodules. Aside from cutaneous manifestations, lepromatous leprosy has a predilection for peripheral nerves and specifically Schwann cells. Histologically, biopsy reveals a flat epidermis and a cell-free subepidermal grenz zone. Within the dermis, there is a diffuse histiocytic infiltrate that typically is not centered around nerves (Figure 2).6,7 Mycobacterium leprae can appear scattered throughout or clustered in globi. Mycobacterium leprae stains red with Ziehl-Neelsen or Wade-Fite stains.6,7 Immunohistochemistry reveals a CD4+ helper T cell (TH2) predominance, supported by the increased expression of type 2 reaction cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13.8

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) embodies 10% to 20% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas; it is more prevalent in older adults (age range, 70–82 years) and women. Clinically, DLBCL presents as either single or multiple rapidly progressing nodules or plaques, usually violaceous or blue-red in color.9,10 The most common area of presentation is on the legs, though it also can surface at other sites.9 On histology, DLBCL has clearly malignant features including frequent mitotic figures, large immunoblasts, and involvement throughout the dermis as well as perivascularly (Figure 3). Spindle-shaped cells and anaplastic features can be present. Immunohistochemically, DLBCL stains strongly positive for CD20 and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) along with other pan–B-cell markers.9-11 The aggressive leg type of DLBCL stains positively for multiple myeloma oncogene 1 (MUM-1).9,11

Cutaneous metastatic adenocarcinoma from internal malignancies occurs in approximately 5% of cancer patients with metastatic spread.12 Most of these cutaneous lesions develop in close proximity to the primary tumor such as on the trunk, head, or neck. All cutaneous metastases carry a poor prognosis. Clinical presentation can vary greatly, ranging from painless, firm, or elastic nodules to lesions that mimic inflammatory skin conditions such as erysipelas or scleroderma. The majority of these metastases develop as painless firm nodules that are flesh colored, pink, red-brown, or purple.12,13 The histopathology of metastatic adenocarcinoma demonstrates an infiltrative nodular appearance, though there rarely are well-circumscribed nodules found.13 The lesion originates in the dermis or subcutaneous tissue. It is a glandulartype lesion that may reflect the tissue of the primary tumor (Figure 4).12,14 Immunohistochemical stains likely will remain consistent with those of the primary tumor, which is not always the case.14

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an aggressive cutaneous malignancy of epithelial and neuroendocrine origin, first described as trabecular carcinoma due to the arrangement of tumor resembling cancellous bone.15,16 Merkel cells are mechanoreceptors found near nerve terminals.17 Approximately 80% of MCCs are associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus, which is a small, double-stranded DNA virus with an icosahedral capsid.17,18 Merkel cell polyomavirus–positive cases of MCC tend to have a better prognosis. In Merkel cell polyomavirus–negative MCC, there is an association with UV damage and increased chromosomal aberrations.18 Merkel cell carcinoma is known for its high rate of recurrence as well as local and distant metastasis. Nodal involvement is the most important prognostic indicator.15 Clinically, MCC is associated with the AEIOU mnemonic (asymptomatic, expanding rapidly, immunosuppression, older than 50 years, UV exposed/fair skin).15-17 Lesions appear as red-blue papules on sun-exposed skin and usually are smaller than 2 cm by their greatest dimension. On histopathology, MCC demonstrates small, round, blue cells arranged in sheets or nests originating in the dermis and occasionally can infiltrate the subcutis and lymphovascular surroundings (Figure 5).16-19 Cells have scant eosinophilic cytoplasm and may have fine granular chromatin. Numerous mitotic figures and apoptotic cells also are present. On immunohistochemistry, these cells will stain positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), CK20, and CD56. Due to their neuroendocrine derivation, they also are commonly synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, and chromogranin A positive. Notably, MCC will stain negative for leukocyte common antigen, CD20, CD3, CD34, and thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1).16,17

Primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphoma can be difficult to diagnose and requires urgent treatment. Clinicians and dermatopathologists need to work together to establish the diagnosis. There is a high mortality rate associated with PCGDTL, making prompt recognition and timely treatment critical. Acknowledgments—Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to our colleagues with the Penn State Health Hematology/Oncology Department (Hershey, Pennsylvania) for comanagement of this patient.

- Merrill ED, Agbay R, Miranda RN, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas showing gamma-delta (γδ) phenotype and predominantly epidermotropic pattern are clinicopathologically distinct from classic primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:204-215.

- Foppoli M, Ferreri AJ. Gamma‐delta T‐cell lymphomas. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:206-218.

- Toro JR, Liewehr DJ, Pabby N, et al. Gamma-delta T-cell phenotype is associated with significantly decreased survival in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:3407-3412.

- Rubio-Gonzalez B, Zain J, Garcia L, et al. Cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma successfully treated with brentuximab vedotin. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388-1390.

- Tong H, Ren Y, Liu H, et al. Clinical characteristics of T-cell lymphoma associated with hemophagocytic syndrome: comparison of T-cell lymphoma with and without hemophagocytic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:81-87.

- Brehmer-Andersson E. Leprosy. Dermatopathology. New York, NY: Springer; 2006:110-113.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Naafs B, Noto S. Reactions in leprosy. In: Nunzi E, Massone C, eds. Leprosy: A Practical Guide. Milan, Italy: Springer; 2012:219-239.

- Hope CB, Pincus LB. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:547-574.

- Billero VL, LaSenna CE, Romanelli M, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting as chronic non-healing ulcer. Int Wound J. 2017;14:830-832.

- Testo N, Olson L, Subramaniyam S, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a MYC-IGH rearrangement and gain of BCL2: expanding the spectrum of MYC/BCL2 double hit lymphomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:769-774.

- Boyd AS. Pulmonary signet-ring cell adenocarcinoma metastatic to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:E66-E68.

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:758-761.

- Trinidad CM, Torres-Cabala CA, Prieto VG, et. Al. Update on eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer classification for Merkel Cell carcinoma and histopathological parameters that determine prognosis. J Clin Pathol. 2017;72:337-340.

- Bandino JP, Purvis CG, Shaffer BR, et al. A comparison of the histopathologic growth patterns between non-Merkel cell small round blue cell tumors and Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:815-818.

- Mauzo SH, Rerrarotto R, Bell D, et al. Molecular characteristics and potential therapeutic targets in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:382-390.

- Lowe G, Brewer J, Bordeaux J. Epidemiology and genetics. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:26-28.

- North J, McCalmont T. Histopathologic diagnosis. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:66-69.

- Merrill ED, Agbay R, Miranda RN, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas showing gamma-delta (γδ) phenotype and predominantly epidermotropic pattern are clinicopathologically distinct from classic primary cutaneous γδ T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41:204-215.

- Foppoli M, Ferreri AJ. Gamma‐delta T‐cell lymphomas. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94:206-218.

- Toro JR, Liewehr DJ, Pabby N, et al. Gamma-delta T-cell phenotype is associated with significantly decreased survival in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:3407-3412.

- Rubio-Gonzalez B, Zain J, Garcia L, et al. Cutaneous gamma-delta T-cell lymphoma successfully treated with brentuximab vedotin. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388-1390.

- Tong H, Ren Y, Liu H, et al. Clinical characteristics of T-cell lymphoma associated with hemophagocytic syndrome: comparison of T-cell lymphoma with and without hemophagocytic syndrome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49:81-87.

- Brehmer-Andersson E. Leprosy. Dermatopathology. New York, NY: Springer; 2006:110-113.

- Massone C, Belachew WA, Schettini A. Histopathology of the lepromatous skin biopsy. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:38-45.

- Naafs B, Noto S. Reactions in leprosy. In: Nunzi E, Massone C, eds. Leprosy: A Practical Guide. Milan, Italy: Springer; 2012:219-239.

- Hope CB, Pincus LB. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:547-574.

- Billero VL, LaSenna CE, Romanelli M, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma presenting as chronic non-healing ulcer. Int Wound J. 2017;14:830-832.

- Testo N, Olson L, Subramaniyam S, et al. Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a MYC-IGH rearrangement and gain of BCL2: expanding the spectrum of MYC/BCL2 double hit lymphomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:769-774.

- Boyd AS. Pulmonary signet-ring cell adenocarcinoma metastatic to the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:E66-E68.

- Guanziroli E, Coggi A, Venegoni L, et al. Cutaneous metastases of internal malignancies: an experience from a single institution. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:609-614.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Cassarino DS. Cutaneous metastasis of adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:758-761.

- Trinidad CM, Torres-Cabala CA, Prieto VG, et. Al. Update on eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer classification for Merkel Cell carcinoma and histopathological parameters that determine prognosis. J Clin Pathol. 2017;72:337-340.

- Bandino JP, Purvis CG, Shaffer BR, et al. A comparison of the histopathologic growth patterns between non-Merkel cell small round blue cell tumors and Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:815-818.

- Mauzo SH, Rerrarotto R, Bell D, et al. Molecular characteristics and potential therapeutic targets in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:382-390.

- Lowe G, Brewer J, Bordeaux J. Epidemiology and genetics. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:26-28.

- North J, McCalmont T. Histopathologic diagnosis. In: Alam M, Bordeaux JS, Yu SS, eds. Merkel Cell Carcinoma. New York, NY: Springer; 2013:66-69.

A 71-year-old man presented with an eruption on the face, shoulders, upper back, and arms of 3 weeks’ duration. The lesions were asymptomatic, and he denied fever, chills, or weight loss. He had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. Physical examination revealed coarse facial features with purple-pink nodules on the face and trunk and ulcerated nodules on the upper extremities. Mucous membrane involvement was noted, and there was marked occipital and submandibular lymphadenopathy. A biopsy of an arm nodule revealed a superficial and deep dermal and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate of atypical CD3+ cells.