User login

When does benign shyness become social anxiety, a treatable disorder?

Since the appearance of social anxiety disorder (SAD) in the DSM-III in 1980, research on its prevalence, characteristics, and treatment have grown (Box 11,2). In addition to the name, the definition of SAD has changed over the years; as a result, its prevalence has increased in recent cohort studies. This has led to debate over whether the experience of shyness is being over-pathologized, or whether SAD has been underdiagnosed in earlier decades. Those who argue that shyness is being over-pathologized note that it is a normal human experience that has evolutionary functions (eg, preventing engagement in harmful social relationships3). Others argue that a high degree of shyness is not beneficial in terms of evolution because it causes the individual to be shunned, so to speak, by society.4

Why worry about ‘over-pathologizing’?

The medicalization of shyness might be a reflection of Western societal values of assertiveness and gregariousness; other societies that value modesty and reticence do not over-pathologize shyness.5 It is important not to assume that someone who is shy necessarily has a “pathologic” level of social anxiety, especially because some people who are shy view that condition as a positive quality, much like sensitivity and conscientiousness.5

The broader issue of what constitutes a mental disorder arises in this debate. A “disorder” is a socially constructed label that describes a set of symptoms occurring together and its associated behaviors, not a real entity with etiological homogeneity.6 Labeling emotional problems “disordered” assumes that happiness is the natural homeostatic state, and distressing emotional states are abnormal and need to be changed.7 A diagnostic label can help improve communication and understand maladaptive behaviors; if that label is reified, however, it can lead to assumptions that the etiology, course, and treatment response are known. Proponents of the diagnostic psychiatric nomenclature have acknowledged the dangers of over-pathologizing normal experiences of living (such as fear) by way of diagnostic labeling.8

Determining when shyness becomes a clinically significant problem—what we call SAD here—demands a delicate distinction that has important implications for treatment. On one hand, if shyness is over-pathologized, persons who neither desire nor need treatment might be subjected to unnecessary and costly intervention. On the other hand, if SAD is underdiagnosed, some persons will not receive treatment that might be beneficial to them.

In this article, we review the similarities and differences between shyness and SAD, and provide recommendations for determining when shyness becomes a more clinically significant problem. We also highlight the importance of this distinction as it pertains to management, and provide suggestions for treatment approaches.

SAD: Definition, prevalence

SAD is defined as a significant fear of embarrassment or humiliation in social or performance-based situations, to a point at which the affected person often avoids these situations or endures them only with a high level of distress9 (Table 1, and Box 2). SAD can be distinguished from other anxiety disorders based on the source and content of the fear (ie, the source being social interaction or performance situations, and the content being a fear that one will show a behavior that will cause embarrassment). SAD also should be distinguished from autism spectrum disorders, in which persons have limited social communication capabilities and inadequate age-appropriate social relationships.

SAD is most highly comorbid with mood and anxiety disorders, with rates of at least 30% in clinical samples.10 The disorder also is highly comorbid with avoidant personality disorder—to a point at which it is argued that they are one and the same disorder.11

As with other psychiatric disorders, anxiety must cause significant impairment or distress. What constitutes significant impairment or distress is subjective, and the arbitrary nature of this criterion can influence estimates of the prevalence of SAD. For example, prevalence ranges as widely as 1.9% to 20.4% when different cut-offs are used for distress ratings and the number of impaired domains.12

The prevalence of SAD varies from 1 epidemiological study to another (ie, the Epidemiological Catchment Area [ECA] Study and the National Comorbidity Survey [NCS])—in part, a consequence of the differing definitions of significant impairment or distress. The ECA study assessed the clinical significance of each symptom in anxiety disorders; the NCS assessed overall clinical significance of the disorder. When the clinical significance criterion was applied at the symptom level to the NCS dataset (as was done in the ECA study), 1-year prevalence decreased by 50% (from 7.4% to 3.7%).13 The manner in which significant impairment or distress is defined (ie, conservatively or liberally) impacts whether social anxiety symptoms are classified as disordered or non-disordered.

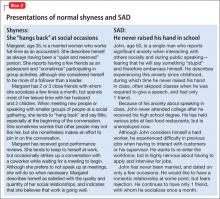

Shyness: Definition, prevalence

Shyness often refers to 1) anxiety, inhibition, reticence, or a combination of these findings, in social and interpersonal situations, and 2) a fear of negative evaluation by others.14 It is a normal facet of personality that combines the experience of social anxiety and inhibited behavior,15 and also has been described as a stable temperament.16 Shyness is common; in the NCS study,17 26% of women and 19% of men characterized themselves as “very shy”; in the NCS Adolescent study,18 nearly 50% of adolescents self-identified as shy.

Persons who are shy tend to self-report greater social anxiety and embarrassment in social situations than non-shy persons do; they also might experience greater autonomic reactivity—especially blushing—in social or performance situations.15 Furthermore, shy persons are more likely to have axis I comorbidity and traits of introversion and neuroticism, compared with non-shy persons.14

Research suggests that temperament and behavioral inhibition are risk factors for mood and anxiety disorders, and appear to have a particularly strong relationship with SAD.19 A recent prospective study showed that shyness tends to increase steeply in toddlerhood, then stabilizes in childhood. Shyness in childhood—but not toddlerhood—is predictive of anxiety, depression, and poorer social skills in adolescence.20

A qualitative, or just quantitative, difference?

It is clear that SAD and shyness share several features—including anxiety and embarrassment—in social interactions. This raises a question: Are SAD and shyness distinct qualitatively, or do they represent points along a continuum, with SAD being an extreme form of shyness?

Continuum hypothesis. Support for the continuum hypothesis includes evidence that SAD and shyness share several features, including autonomic arousal, deficits in social skills (eg, aversion of gaze, difficulty initiating and maintaining conversation), avoidance of social situations, and fear of negative evaluation.21,22 In addition, both shyness and SAD are highly heritable,23 and mothers of shy children have a significantly higher rate of SAD than non-shy children do.24 No familial or genetic studies have compared heritability and familial aggregation in shyness and SAD.

According to the continuum hypothesis, if SAD is an extreme form of shyness, all (or nearly all) persons who have a diagnosis of SAD also would be characterized as shy. However, only approximately one-half of such persons report having been shy in childhood.17 Less than one-quarter of shy persons meet criteria for SAD.14,18 Because many persons who are shy do not meet criteria for SAD, and many who have SAD were not considered shy earlier in life, it has been suggested that this supports a qualitative distinction.

Qualitative distinctiveness. Despite having similarities, several features distinguish the experience of SAD from that of shyness. Compared with shyness, a SAD diagnosis is associated with:

- greater comorbidity

- greater severity of avoidance and impairment

- poorer quality of life.18,21,25

Studies that compared SAD, shyness without SAD, and non-shyness have shown that the shyness without SAD group more closely resembles the non-shy group than the SAD group—particularly with regard to impairment, presence of substance use, and other behavioral problems.18,25

Given the evidence, experts have concluded that shyness and a SAD diagnosis are overlapping yet different constructs that encapsulate qualitative and quantitative differences.25 There is a spectrum of shyness that ranges from a normative level to a higher level that overlaps the experience of SAD, but the 2 states represent different constructs.25

Guidance for making an assessment. Because of similarities in anxiety, embarrassment, and other symptoms in social situations, the best way to determine whether shyness crosses the line into a clinically significant problem is to assess the severity of the anxiety and associated degree of impairment and distress. More severe anxiety paired with distress about having anxiety and significant impairment in multiple areas of functioning might indicate more problematic social anxiety—a diagnosis of SAD—not just “normal” shyness.

It is important to take into account the environmental and cultural context of a patient’s distress and impairment because these features might fall within a normal range, given immediate circumstances (such as speaking in front of a large audience when one is not normally called on to do so, to a degree that does not interfere with general social functioning6).

What is considered a normative range depends on the developmental stage:

- Among children, a greater level of shyness might be considered more normative when it manifests during developmental stages in which separation anxiety appears.

- Among adolescents, a greater level of shyness might be considered normative especially during early adolescence (when social relationships become more important), and during times of transition (ie, entering high school).

- In adulthood, a greater level of normative shyness or social anxiety might be present during a major life change (eg, beginning to date again after the loss of a lengthy marriage or romantic relationship).

Assessment tools

Assessment tools can help you differentiate normal shyness from SAD. Several empirically-validated rating scales exist, including clinician-rated and self-report scales.

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale26 rates the severity of fear and avoidance in a variety of social interaction and performance-based situations. However, it was developed primarily as a clinician-rated scale and might be more burdensome to complete in practice. In addition, it does not provide cut-offs to indicate when more clinically significant anxiety might be likely.

Clinically Useful Social Anxiety Disorder Outcome Scale (CUSADOS)27 and Mini-Social Phobia Inventory (Mini-SPIN)28 are brief self-report scales that provide cut-offs to suggest further assessment is warranted. A cut-off score of 16 on the CUSADOS suggests the presence of SAD with 73% diagnostic efficiency.

One disadvantage to relying on a rating scale alone is the narrow focus on symptoms. Given that shyness and SAD share similar symptoms, it is necessary to assess the degree of impairment related to these symptoms to determine whether the problem is clinically significant. The overly narrow focus on symptoms utilized by the biomedical approach has been criticized for contributing to the medicalization of normal shyness.5

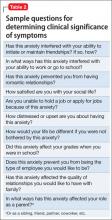

Diagnostic interviews, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders29 include sections on SAD that assess avoidance and impairment/distress associated with anxiety. Because these interviews may increase the time burden during an office visit, there are several general questions outside of a structured interview that you can ask, such as: “Has this anxiety interfered with your ability to initiate or maintain friendships? If so, how?” (Table 2). Persons with clinically significant social anxiety, rather than shyness, tend to report greater effects on their relationships and on work or school performance, as well as greater distress about having that anxiety.

Treatment approaches based on distinctions

Exercise care in making the distinction between normal shyness and dysfunctional and impairing levels of anxiety characteristic of SAD, because persons who display normal shyness but who are overdiagnosed might feel stigmatized by a diagnostic label.5 Also, overpathologizing shyness takes what is a social problem out of context, and could promote treatment strategies that might not be helpful or effective.30

Unnecessary diagnosis might lead to unnecessary treatment, such as prescribing an antidepressant or benzodiazepine. Avoiding such a situation is important, because of the side effects associated with medication and the potential for dependence and withdrawal effects with benzodiazepines.

Persons who exhibit normal shyness do not require medical treatment and, often, do not want it. However, some people may be interested in improving their ability to function in social interactions. Self-help approaches or brief psychotherapy (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) should be the first step—and might be all that is necessary.

The opposite side of the problem. Under-recognition of clinically significant social anxiety can lead to under-treatment, which is common even in patients with a SAD diagnosis.31 Treatment options include CBT, medication, and CBT combined with medication (Table 3):

- several studies have demonstrated the short- and long-term efficacy of CBT alone for SAD

- medication alone has been efficacious in the short-term, but less efficacious than CBT in the long-term

- combined treatment also has been shown to be more efficacious than CBT or medication alone in the short-term

- there is evidence to suggest that CBT alone is more efficacious in the long-term compared with combined treatment.a

CBT is recommended as an appropriate first-line option, especially for mild and moderate SAD; it is the preferred initial treatment option of the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). For more severe presentations (such as the presence of comorbidity) or when a patient did not respond to an adequate course of CBT, combined treatment might be an option—the goal being to taper the medication and continue CBT as a longer-term treatment. Research has shown that continuing CBT while discontinuing medication helps prevent relapse.32,33

Appropriate pharmacotherapy options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.34 Increasingly, benzodiazepines are considered less desirable; they are not recommended for routine use in SAD in the NICE guidelines. Those guidelines call for continuing pharmacotherapy for 6 months when a patient responds to treatment within 3 months, then discontinuing medication with the aid of CBT.

Bottom Line

The severity of anxiety and associated impairment and distress are the main variables that differentiate normal shyness and clinically significant social anxiety. Taking care not to over-pathologize normal shyness and common social anxiety concerns or underdiagnose severe, impairing social anxiety disorder has important implications for treatment—and for whether a patient needs treatment at all.

Related Resources

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment, and treatment of social anxiety disorder. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg159.

• Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, eds. Social anxiety: clinical, developmental, and social perspectives, 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 2010.

• The Shyness Institute. www.shyness.com.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax Clonazepam • Klonopin Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox Paroxetine • Paxil Phenelzine • Nardil

Sertraline • Zoloft Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Kristy L. Dalrymple, PhD, discusses, treating social anxiety disorder. Dr. Dalrymple is Staff Psychologist, Department of Psychiatry, Rhode Island Hospital, and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

1. Bruce LC, Coles ME, Heimberg RG. Social phobia and social anxiety disorder: effect of disorder name on recommendation for treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):538.

2. Bögels SM, Alden L, Beidel DC, et al. Social anxiety disorder: questions and answers for the DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:168-189.

3. Wakefield JC, Horwitz AV, Schmitz MF. Are we overpathologizing the socially anxious? Social phobia from a harmful dysfunction perspective. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):317-319.

4. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Justifying the diagnostic status of social phobia: a reply to Wakefield, Horwitz, and Schmitz. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):320-323.

5. Scott S. The medicalisation of shyness: from social misfits to social fitness. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2006;28(2):133-153.

6. Wakefield JC. The DSM-5 debate over the bereavement exclusion: psychiatric diagnosis and the future of empirically supported treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013; 33(7):825-845.

7. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: the process and practice of mindful change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012.

8. Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA, eds. A research agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

10. Dalrymple KL, Zimmerman M. Does comorbid social anxiety disorder impact the clinical presentation of principal major depressive disorder? J Affect Disord. 2007;100:241-247.

11. Dalrymple KL. Issues and controversies surrounding the diagnosis and treatment of social anxiety disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(8):993-1008.

12. Furmark T, Tillfors M, Everz PO, et al. Social phobia in the general population: prevalence and sociodemographic profile. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:416-424.

13. Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robins LN, et al. Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys’ estimates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:115-123.

14. Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC. Shyness: relationship to social phobia and other psychiatric disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:209-221.

15. Hofmann SG, Moscovitch DA, Hyo-Jin K. Autonomic correlates of social anxiety and embarrassment in shy and non-shy individuals. Int J Psychophysiology. 2006;61:134-142.

16. Kagan J. Temperamental contributions to affective and behavioral profiles in childhood. In: Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, eds. From social anxiety to social phobia: multiple perspectives. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001:216-234.

17. Cox BJ, MacPherson PS, Enns MW. Psychiatric correlates of childhood shyness in a nationally representative sample. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1019-1027.

18. Burstein M, Ameli-Grillon L, Merikangas KR. Shyness versus social phobia in US youth. Pediatrics. 2011;128:917-925.

19. Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco J, Henin A, et al. Behavioral inhibition. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:357-367.

20. Karevold E, Ystrom E, Coplan RJ, et al. A prospective longitudinal study of shyness from infancy to adolescence: stability, age-related changes, and prediction of socio-emotional functioning. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012; 40:1167-1177.

21. Chavira DA, Stein MB, Malcarne VL. Scrutinizing the relationship between shyness and social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16:585-598.

22. Schneier FR, Blanco C, Antia SX, et al. The social anxiety spectrum. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;25:757-774.

23. Stein MB, Chavira DA, Jang KL. Bringing up bashful baby: developmental pathways to social phobia. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2001;24:797-818.

24. Cooper PJ, Eke M. Childhood shyness and maternal social phobia: a community study. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:439-443.

25. Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC, et al. Differentiating social phobia from shyness. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:469-476.

26. Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141-173.

27. Dalrymple, KL, Martinez J, Tepe E, et al. A clinically useful social anxiety disorder outcome scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):758-765.

28. Connor KM, Kobak KA, Churchill LE, et al. Mini-SPIN: a brief screening assessment for generalized social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14(2):137-140.

29. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997.

30. Conrad P. Medicalization and social control. Ann Rev Sociology. 1992;18:209-232.

31. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I. Clinician recognition of anxiety disorders in depressed outpatients. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:325-333.

32. Gelernter CS, Uhde TW, Cimbolic P, et al. Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:938-945.

33. Otto MW, Smits JA, Reese HE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 5):34-41.

34. Blanco C, Bragdon LB, Schneier FR, et al. The evidence-based pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:235-249.

Since the appearance of social anxiety disorder (SAD) in the DSM-III in 1980, research on its prevalence, characteristics, and treatment have grown (Box 11,2). In addition to the name, the definition of SAD has changed over the years; as a result, its prevalence has increased in recent cohort studies. This has led to debate over whether the experience of shyness is being over-pathologized, or whether SAD has been underdiagnosed in earlier decades. Those who argue that shyness is being over-pathologized note that it is a normal human experience that has evolutionary functions (eg, preventing engagement in harmful social relationships3). Others argue that a high degree of shyness is not beneficial in terms of evolution because it causes the individual to be shunned, so to speak, by society.4

Why worry about ‘over-pathologizing’?

The medicalization of shyness might be a reflection of Western societal values of assertiveness and gregariousness; other societies that value modesty and reticence do not over-pathologize shyness.5 It is important not to assume that someone who is shy necessarily has a “pathologic” level of social anxiety, especially because some people who are shy view that condition as a positive quality, much like sensitivity and conscientiousness.5

The broader issue of what constitutes a mental disorder arises in this debate. A “disorder” is a socially constructed label that describes a set of symptoms occurring together and its associated behaviors, not a real entity with etiological homogeneity.6 Labeling emotional problems “disordered” assumes that happiness is the natural homeostatic state, and distressing emotional states are abnormal and need to be changed.7 A diagnostic label can help improve communication and understand maladaptive behaviors; if that label is reified, however, it can lead to assumptions that the etiology, course, and treatment response are known. Proponents of the diagnostic psychiatric nomenclature have acknowledged the dangers of over-pathologizing normal experiences of living (such as fear) by way of diagnostic labeling.8

Determining when shyness becomes a clinically significant problem—what we call SAD here—demands a delicate distinction that has important implications for treatment. On one hand, if shyness is over-pathologized, persons who neither desire nor need treatment might be subjected to unnecessary and costly intervention. On the other hand, if SAD is underdiagnosed, some persons will not receive treatment that might be beneficial to them.

In this article, we review the similarities and differences between shyness and SAD, and provide recommendations for determining when shyness becomes a more clinically significant problem. We also highlight the importance of this distinction as it pertains to management, and provide suggestions for treatment approaches.

SAD: Definition, prevalence

SAD is defined as a significant fear of embarrassment or humiliation in social or performance-based situations, to a point at which the affected person often avoids these situations or endures them only with a high level of distress9 (Table 1, and Box 2). SAD can be distinguished from other anxiety disorders based on the source and content of the fear (ie, the source being social interaction or performance situations, and the content being a fear that one will show a behavior that will cause embarrassment). SAD also should be distinguished from autism spectrum disorders, in which persons have limited social communication capabilities and inadequate age-appropriate social relationships.

SAD is most highly comorbid with mood and anxiety disorders, with rates of at least 30% in clinical samples.10 The disorder also is highly comorbid with avoidant personality disorder—to a point at which it is argued that they are one and the same disorder.11

As with other psychiatric disorders, anxiety must cause significant impairment or distress. What constitutes significant impairment or distress is subjective, and the arbitrary nature of this criterion can influence estimates of the prevalence of SAD. For example, prevalence ranges as widely as 1.9% to 20.4% when different cut-offs are used for distress ratings and the number of impaired domains.12

The prevalence of SAD varies from 1 epidemiological study to another (ie, the Epidemiological Catchment Area [ECA] Study and the National Comorbidity Survey [NCS])—in part, a consequence of the differing definitions of significant impairment or distress. The ECA study assessed the clinical significance of each symptom in anxiety disorders; the NCS assessed overall clinical significance of the disorder. When the clinical significance criterion was applied at the symptom level to the NCS dataset (as was done in the ECA study), 1-year prevalence decreased by 50% (from 7.4% to 3.7%).13 The manner in which significant impairment or distress is defined (ie, conservatively or liberally) impacts whether social anxiety symptoms are classified as disordered or non-disordered.

Shyness: Definition, prevalence

Shyness often refers to 1) anxiety, inhibition, reticence, or a combination of these findings, in social and interpersonal situations, and 2) a fear of negative evaluation by others.14 It is a normal facet of personality that combines the experience of social anxiety and inhibited behavior,15 and also has been described as a stable temperament.16 Shyness is common; in the NCS study,17 26% of women and 19% of men characterized themselves as “very shy”; in the NCS Adolescent study,18 nearly 50% of adolescents self-identified as shy.

Persons who are shy tend to self-report greater social anxiety and embarrassment in social situations than non-shy persons do; they also might experience greater autonomic reactivity—especially blushing—in social or performance situations.15 Furthermore, shy persons are more likely to have axis I comorbidity and traits of introversion and neuroticism, compared with non-shy persons.14

Research suggests that temperament and behavioral inhibition are risk factors for mood and anxiety disorders, and appear to have a particularly strong relationship with SAD.19 A recent prospective study showed that shyness tends to increase steeply in toddlerhood, then stabilizes in childhood. Shyness in childhood—but not toddlerhood—is predictive of anxiety, depression, and poorer social skills in adolescence.20

A qualitative, or just quantitative, difference?

It is clear that SAD and shyness share several features—including anxiety and embarrassment—in social interactions. This raises a question: Are SAD and shyness distinct qualitatively, or do they represent points along a continuum, with SAD being an extreme form of shyness?

Continuum hypothesis. Support for the continuum hypothesis includes evidence that SAD and shyness share several features, including autonomic arousal, deficits in social skills (eg, aversion of gaze, difficulty initiating and maintaining conversation), avoidance of social situations, and fear of negative evaluation.21,22 In addition, both shyness and SAD are highly heritable,23 and mothers of shy children have a significantly higher rate of SAD than non-shy children do.24 No familial or genetic studies have compared heritability and familial aggregation in shyness and SAD.

According to the continuum hypothesis, if SAD is an extreme form of shyness, all (or nearly all) persons who have a diagnosis of SAD also would be characterized as shy. However, only approximately one-half of such persons report having been shy in childhood.17 Less than one-quarter of shy persons meet criteria for SAD.14,18 Because many persons who are shy do not meet criteria for SAD, and many who have SAD were not considered shy earlier in life, it has been suggested that this supports a qualitative distinction.

Qualitative distinctiveness. Despite having similarities, several features distinguish the experience of SAD from that of shyness. Compared with shyness, a SAD diagnosis is associated with:

- greater comorbidity

- greater severity of avoidance and impairment

- poorer quality of life.18,21,25

Studies that compared SAD, shyness without SAD, and non-shyness have shown that the shyness without SAD group more closely resembles the non-shy group than the SAD group—particularly with regard to impairment, presence of substance use, and other behavioral problems.18,25

Given the evidence, experts have concluded that shyness and a SAD diagnosis are overlapping yet different constructs that encapsulate qualitative and quantitative differences.25 There is a spectrum of shyness that ranges from a normative level to a higher level that overlaps the experience of SAD, but the 2 states represent different constructs.25

Guidance for making an assessment. Because of similarities in anxiety, embarrassment, and other symptoms in social situations, the best way to determine whether shyness crosses the line into a clinically significant problem is to assess the severity of the anxiety and associated degree of impairment and distress. More severe anxiety paired with distress about having anxiety and significant impairment in multiple areas of functioning might indicate more problematic social anxiety—a diagnosis of SAD—not just “normal” shyness.

It is important to take into account the environmental and cultural context of a patient’s distress and impairment because these features might fall within a normal range, given immediate circumstances (such as speaking in front of a large audience when one is not normally called on to do so, to a degree that does not interfere with general social functioning6).

What is considered a normative range depends on the developmental stage:

- Among children, a greater level of shyness might be considered more normative when it manifests during developmental stages in which separation anxiety appears.

- Among adolescents, a greater level of shyness might be considered normative especially during early adolescence (when social relationships become more important), and during times of transition (ie, entering high school).

- In adulthood, a greater level of normative shyness or social anxiety might be present during a major life change (eg, beginning to date again after the loss of a lengthy marriage or romantic relationship).

Assessment tools

Assessment tools can help you differentiate normal shyness from SAD. Several empirically-validated rating scales exist, including clinician-rated and self-report scales.

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale26 rates the severity of fear and avoidance in a variety of social interaction and performance-based situations. However, it was developed primarily as a clinician-rated scale and might be more burdensome to complete in practice. In addition, it does not provide cut-offs to indicate when more clinically significant anxiety might be likely.

Clinically Useful Social Anxiety Disorder Outcome Scale (CUSADOS)27 and Mini-Social Phobia Inventory (Mini-SPIN)28 are brief self-report scales that provide cut-offs to suggest further assessment is warranted. A cut-off score of 16 on the CUSADOS suggests the presence of SAD with 73% diagnostic efficiency.

One disadvantage to relying on a rating scale alone is the narrow focus on symptoms. Given that shyness and SAD share similar symptoms, it is necessary to assess the degree of impairment related to these symptoms to determine whether the problem is clinically significant. The overly narrow focus on symptoms utilized by the biomedical approach has been criticized for contributing to the medicalization of normal shyness.5

Diagnostic interviews, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders29 include sections on SAD that assess avoidance and impairment/distress associated with anxiety. Because these interviews may increase the time burden during an office visit, there are several general questions outside of a structured interview that you can ask, such as: “Has this anxiety interfered with your ability to initiate or maintain friendships? If so, how?” (Table 2). Persons with clinically significant social anxiety, rather than shyness, tend to report greater effects on their relationships and on work or school performance, as well as greater distress about having that anxiety.

Treatment approaches based on distinctions

Exercise care in making the distinction between normal shyness and dysfunctional and impairing levels of anxiety characteristic of SAD, because persons who display normal shyness but who are overdiagnosed might feel stigmatized by a diagnostic label.5 Also, overpathologizing shyness takes what is a social problem out of context, and could promote treatment strategies that might not be helpful or effective.30

Unnecessary diagnosis might lead to unnecessary treatment, such as prescribing an antidepressant or benzodiazepine. Avoiding such a situation is important, because of the side effects associated with medication and the potential for dependence and withdrawal effects with benzodiazepines.

Persons who exhibit normal shyness do not require medical treatment and, often, do not want it. However, some people may be interested in improving their ability to function in social interactions. Self-help approaches or brief psychotherapy (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) should be the first step—and might be all that is necessary.

The opposite side of the problem. Under-recognition of clinically significant social anxiety can lead to under-treatment, which is common even in patients with a SAD diagnosis.31 Treatment options include CBT, medication, and CBT combined with medication (Table 3):

- several studies have demonstrated the short- and long-term efficacy of CBT alone for SAD

- medication alone has been efficacious in the short-term, but less efficacious than CBT in the long-term

- combined treatment also has been shown to be more efficacious than CBT or medication alone in the short-term

- there is evidence to suggest that CBT alone is more efficacious in the long-term compared with combined treatment.a

CBT is recommended as an appropriate first-line option, especially for mild and moderate SAD; it is the preferred initial treatment option of the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). For more severe presentations (such as the presence of comorbidity) or when a patient did not respond to an adequate course of CBT, combined treatment might be an option—the goal being to taper the medication and continue CBT as a longer-term treatment. Research has shown that continuing CBT while discontinuing medication helps prevent relapse.32,33

Appropriate pharmacotherapy options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.34 Increasingly, benzodiazepines are considered less desirable; they are not recommended for routine use in SAD in the NICE guidelines. Those guidelines call for continuing pharmacotherapy for 6 months when a patient responds to treatment within 3 months, then discontinuing medication with the aid of CBT.

Bottom Line

The severity of anxiety and associated impairment and distress are the main variables that differentiate normal shyness and clinically significant social anxiety. Taking care not to over-pathologize normal shyness and common social anxiety concerns or underdiagnose severe, impairing social anxiety disorder has important implications for treatment—and for whether a patient needs treatment at all.

Related Resources

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment, and treatment of social anxiety disorder. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg159.

• Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, eds. Social anxiety: clinical, developmental, and social perspectives, 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 2010.

• The Shyness Institute. www.shyness.com.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax Clonazepam • Klonopin Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox Paroxetine • Paxil Phenelzine • Nardil

Sertraline • Zoloft Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Kristy L. Dalrymple, PhD, discusses, treating social anxiety disorder. Dr. Dalrymple is Staff Psychologist, Department of Psychiatry, Rhode Island Hospital, and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

Since the appearance of social anxiety disorder (SAD) in the DSM-III in 1980, research on its prevalence, characteristics, and treatment have grown (Box 11,2). In addition to the name, the definition of SAD has changed over the years; as a result, its prevalence has increased in recent cohort studies. This has led to debate over whether the experience of shyness is being over-pathologized, or whether SAD has been underdiagnosed in earlier decades. Those who argue that shyness is being over-pathologized note that it is a normal human experience that has evolutionary functions (eg, preventing engagement in harmful social relationships3). Others argue that a high degree of shyness is not beneficial in terms of evolution because it causes the individual to be shunned, so to speak, by society.4

Why worry about ‘over-pathologizing’?

The medicalization of shyness might be a reflection of Western societal values of assertiveness and gregariousness; other societies that value modesty and reticence do not over-pathologize shyness.5 It is important not to assume that someone who is shy necessarily has a “pathologic” level of social anxiety, especially because some people who are shy view that condition as a positive quality, much like sensitivity and conscientiousness.5

The broader issue of what constitutes a mental disorder arises in this debate. A “disorder” is a socially constructed label that describes a set of symptoms occurring together and its associated behaviors, not a real entity with etiological homogeneity.6 Labeling emotional problems “disordered” assumes that happiness is the natural homeostatic state, and distressing emotional states are abnormal and need to be changed.7 A diagnostic label can help improve communication and understand maladaptive behaviors; if that label is reified, however, it can lead to assumptions that the etiology, course, and treatment response are known. Proponents of the diagnostic psychiatric nomenclature have acknowledged the dangers of over-pathologizing normal experiences of living (such as fear) by way of diagnostic labeling.8

Determining when shyness becomes a clinically significant problem—what we call SAD here—demands a delicate distinction that has important implications for treatment. On one hand, if shyness is over-pathologized, persons who neither desire nor need treatment might be subjected to unnecessary and costly intervention. On the other hand, if SAD is underdiagnosed, some persons will not receive treatment that might be beneficial to them.

In this article, we review the similarities and differences between shyness and SAD, and provide recommendations for determining when shyness becomes a more clinically significant problem. We also highlight the importance of this distinction as it pertains to management, and provide suggestions for treatment approaches.

SAD: Definition, prevalence

SAD is defined as a significant fear of embarrassment or humiliation in social or performance-based situations, to a point at which the affected person often avoids these situations or endures them only with a high level of distress9 (Table 1, and Box 2). SAD can be distinguished from other anxiety disorders based on the source and content of the fear (ie, the source being social interaction or performance situations, and the content being a fear that one will show a behavior that will cause embarrassment). SAD also should be distinguished from autism spectrum disorders, in which persons have limited social communication capabilities and inadequate age-appropriate social relationships.

SAD is most highly comorbid with mood and anxiety disorders, with rates of at least 30% in clinical samples.10 The disorder also is highly comorbid with avoidant personality disorder—to a point at which it is argued that they are one and the same disorder.11

As with other psychiatric disorders, anxiety must cause significant impairment or distress. What constitutes significant impairment or distress is subjective, and the arbitrary nature of this criterion can influence estimates of the prevalence of SAD. For example, prevalence ranges as widely as 1.9% to 20.4% when different cut-offs are used for distress ratings and the number of impaired domains.12

The prevalence of SAD varies from 1 epidemiological study to another (ie, the Epidemiological Catchment Area [ECA] Study and the National Comorbidity Survey [NCS])—in part, a consequence of the differing definitions of significant impairment or distress. The ECA study assessed the clinical significance of each symptom in anxiety disorders; the NCS assessed overall clinical significance of the disorder. When the clinical significance criterion was applied at the symptom level to the NCS dataset (as was done in the ECA study), 1-year prevalence decreased by 50% (from 7.4% to 3.7%).13 The manner in which significant impairment or distress is defined (ie, conservatively or liberally) impacts whether social anxiety symptoms are classified as disordered or non-disordered.

Shyness: Definition, prevalence

Shyness often refers to 1) anxiety, inhibition, reticence, or a combination of these findings, in social and interpersonal situations, and 2) a fear of negative evaluation by others.14 It is a normal facet of personality that combines the experience of social anxiety and inhibited behavior,15 and also has been described as a stable temperament.16 Shyness is common; in the NCS study,17 26% of women and 19% of men characterized themselves as “very shy”; in the NCS Adolescent study,18 nearly 50% of adolescents self-identified as shy.

Persons who are shy tend to self-report greater social anxiety and embarrassment in social situations than non-shy persons do; they also might experience greater autonomic reactivity—especially blushing—in social or performance situations.15 Furthermore, shy persons are more likely to have axis I comorbidity and traits of introversion and neuroticism, compared with non-shy persons.14

Research suggests that temperament and behavioral inhibition are risk factors for mood and anxiety disorders, and appear to have a particularly strong relationship with SAD.19 A recent prospective study showed that shyness tends to increase steeply in toddlerhood, then stabilizes in childhood. Shyness in childhood—but not toddlerhood—is predictive of anxiety, depression, and poorer social skills in adolescence.20

A qualitative, or just quantitative, difference?

It is clear that SAD and shyness share several features—including anxiety and embarrassment—in social interactions. This raises a question: Are SAD and shyness distinct qualitatively, or do they represent points along a continuum, with SAD being an extreme form of shyness?

Continuum hypothesis. Support for the continuum hypothesis includes evidence that SAD and shyness share several features, including autonomic arousal, deficits in social skills (eg, aversion of gaze, difficulty initiating and maintaining conversation), avoidance of social situations, and fear of negative evaluation.21,22 In addition, both shyness and SAD are highly heritable,23 and mothers of shy children have a significantly higher rate of SAD than non-shy children do.24 No familial or genetic studies have compared heritability and familial aggregation in shyness and SAD.

According to the continuum hypothesis, if SAD is an extreme form of shyness, all (or nearly all) persons who have a diagnosis of SAD also would be characterized as shy. However, only approximately one-half of such persons report having been shy in childhood.17 Less than one-quarter of shy persons meet criteria for SAD.14,18 Because many persons who are shy do not meet criteria for SAD, and many who have SAD were not considered shy earlier in life, it has been suggested that this supports a qualitative distinction.

Qualitative distinctiveness. Despite having similarities, several features distinguish the experience of SAD from that of shyness. Compared with shyness, a SAD diagnosis is associated with:

- greater comorbidity

- greater severity of avoidance and impairment

- poorer quality of life.18,21,25

Studies that compared SAD, shyness without SAD, and non-shyness have shown that the shyness without SAD group more closely resembles the non-shy group than the SAD group—particularly with regard to impairment, presence of substance use, and other behavioral problems.18,25

Given the evidence, experts have concluded that shyness and a SAD diagnosis are overlapping yet different constructs that encapsulate qualitative and quantitative differences.25 There is a spectrum of shyness that ranges from a normative level to a higher level that overlaps the experience of SAD, but the 2 states represent different constructs.25

Guidance for making an assessment. Because of similarities in anxiety, embarrassment, and other symptoms in social situations, the best way to determine whether shyness crosses the line into a clinically significant problem is to assess the severity of the anxiety and associated degree of impairment and distress. More severe anxiety paired with distress about having anxiety and significant impairment in multiple areas of functioning might indicate more problematic social anxiety—a diagnosis of SAD—not just “normal” shyness.

It is important to take into account the environmental and cultural context of a patient’s distress and impairment because these features might fall within a normal range, given immediate circumstances (such as speaking in front of a large audience when one is not normally called on to do so, to a degree that does not interfere with general social functioning6).

What is considered a normative range depends on the developmental stage:

- Among children, a greater level of shyness might be considered more normative when it manifests during developmental stages in which separation anxiety appears.

- Among adolescents, a greater level of shyness might be considered normative especially during early adolescence (when social relationships become more important), and during times of transition (ie, entering high school).

- In adulthood, a greater level of normative shyness or social anxiety might be present during a major life change (eg, beginning to date again after the loss of a lengthy marriage or romantic relationship).

Assessment tools

Assessment tools can help you differentiate normal shyness from SAD. Several empirically-validated rating scales exist, including clinician-rated and self-report scales.

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale26 rates the severity of fear and avoidance in a variety of social interaction and performance-based situations. However, it was developed primarily as a clinician-rated scale and might be more burdensome to complete in practice. In addition, it does not provide cut-offs to indicate when more clinically significant anxiety might be likely.

Clinically Useful Social Anxiety Disorder Outcome Scale (CUSADOS)27 and Mini-Social Phobia Inventory (Mini-SPIN)28 are brief self-report scales that provide cut-offs to suggest further assessment is warranted. A cut-off score of 16 on the CUSADOS suggests the presence of SAD with 73% diagnostic efficiency.

One disadvantage to relying on a rating scale alone is the narrow focus on symptoms. Given that shyness and SAD share similar symptoms, it is necessary to assess the degree of impairment related to these symptoms to determine whether the problem is clinically significant. The overly narrow focus on symptoms utilized by the biomedical approach has been criticized for contributing to the medicalization of normal shyness.5

Diagnostic interviews, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders29 include sections on SAD that assess avoidance and impairment/distress associated with anxiety. Because these interviews may increase the time burden during an office visit, there are several general questions outside of a structured interview that you can ask, such as: “Has this anxiety interfered with your ability to initiate or maintain friendships? If so, how?” (Table 2). Persons with clinically significant social anxiety, rather than shyness, tend to report greater effects on their relationships and on work or school performance, as well as greater distress about having that anxiety.

Treatment approaches based on distinctions

Exercise care in making the distinction between normal shyness and dysfunctional and impairing levels of anxiety characteristic of SAD, because persons who display normal shyness but who are overdiagnosed might feel stigmatized by a diagnostic label.5 Also, overpathologizing shyness takes what is a social problem out of context, and could promote treatment strategies that might not be helpful or effective.30

Unnecessary diagnosis might lead to unnecessary treatment, such as prescribing an antidepressant or benzodiazepine. Avoiding such a situation is important, because of the side effects associated with medication and the potential for dependence and withdrawal effects with benzodiazepines.

Persons who exhibit normal shyness do not require medical treatment and, often, do not want it. However, some people may be interested in improving their ability to function in social interactions. Self-help approaches or brief psychotherapy (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) should be the first step—and might be all that is necessary.

The opposite side of the problem. Under-recognition of clinically significant social anxiety can lead to under-treatment, which is common even in patients with a SAD diagnosis.31 Treatment options include CBT, medication, and CBT combined with medication (Table 3):

- several studies have demonstrated the short- and long-term efficacy of CBT alone for SAD

- medication alone has been efficacious in the short-term, but less efficacious than CBT in the long-term

- combined treatment also has been shown to be more efficacious than CBT or medication alone in the short-term

- there is evidence to suggest that CBT alone is more efficacious in the long-term compared with combined treatment.a

CBT is recommended as an appropriate first-line option, especially for mild and moderate SAD; it is the preferred initial treatment option of the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). For more severe presentations (such as the presence of comorbidity) or when a patient did not respond to an adequate course of CBT, combined treatment might be an option—the goal being to taper the medication and continue CBT as a longer-term treatment. Research has shown that continuing CBT while discontinuing medication helps prevent relapse.32,33

Appropriate pharmacotherapy options include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.34 Increasingly, benzodiazepines are considered less desirable; they are not recommended for routine use in SAD in the NICE guidelines. Those guidelines call for continuing pharmacotherapy for 6 months when a patient responds to treatment within 3 months, then discontinuing medication with the aid of CBT.

Bottom Line

The severity of anxiety and associated impairment and distress are the main variables that differentiate normal shyness and clinically significant social anxiety. Taking care not to over-pathologize normal shyness and common social anxiety concerns or underdiagnose severe, impairing social anxiety disorder has important implications for treatment—and for whether a patient needs treatment at all.

Related Resources

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment, and treatment of social anxiety disorder. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/cg159.

• Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, eds. Social anxiety: clinical, developmental, and social perspectives, 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 2010.

• The Shyness Institute. www.shyness.com.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax Clonazepam • Klonopin Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox Paroxetine • Paxil Phenelzine • Nardil

Sertraline • Zoloft Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Kristy L. Dalrymple, PhD, discusses, treating social anxiety disorder. Dr. Dalrymple is Staff Psychologist, Department of Psychiatry, Rhode Island Hospital, and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

1. Bruce LC, Coles ME, Heimberg RG. Social phobia and social anxiety disorder: effect of disorder name on recommendation for treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):538.

2. Bögels SM, Alden L, Beidel DC, et al. Social anxiety disorder: questions and answers for the DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:168-189.

3. Wakefield JC, Horwitz AV, Schmitz MF. Are we overpathologizing the socially anxious? Social phobia from a harmful dysfunction perspective. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):317-319.

4. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Justifying the diagnostic status of social phobia: a reply to Wakefield, Horwitz, and Schmitz. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):320-323.

5. Scott S. The medicalisation of shyness: from social misfits to social fitness. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2006;28(2):133-153.

6. Wakefield JC. The DSM-5 debate over the bereavement exclusion: psychiatric diagnosis and the future of empirically supported treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013; 33(7):825-845.

7. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: the process and practice of mindful change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012.

8. Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA, eds. A research agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

10. Dalrymple KL, Zimmerman M. Does comorbid social anxiety disorder impact the clinical presentation of principal major depressive disorder? J Affect Disord. 2007;100:241-247.

11. Dalrymple KL. Issues and controversies surrounding the diagnosis and treatment of social anxiety disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(8):993-1008.

12. Furmark T, Tillfors M, Everz PO, et al. Social phobia in the general population: prevalence and sociodemographic profile. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:416-424.

13. Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robins LN, et al. Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys’ estimates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:115-123.

14. Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC. Shyness: relationship to social phobia and other psychiatric disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:209-221.

15. Hofmann SG, Moscovitch DA, Hyo-Jin K. Autonomic correlates of social anxiety and embarrassment in shy and non-shy individuals. Int J Psychophysiology. 2006;61:134-142.

16. Kagan J. Temperamental contributions to affective and behavioral profiles in childhood. In: Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, eds. From social anxiety to social phobia: multiple perspectives. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001:216-234.

17. Cox BJ, MacPherson PS, Enns MW. Psychiatric correlates of childhood shyness in a nationally representative sample. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1019-1027.

18. Burstein M, Ameli-Grillon L, Merikangas KR. Shyness versus social phobia in US youth. Pediatrics. 2011;128:917-925.

19. Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco J, Henin A, et al. Behavioral inhibition. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:357-367.

20. Karevold E, Ystrom E, Coplan RJ, et al. A prospective longitudinal study of shyness from infancy to adolescence: stability, age-related changes, and prediction of socio-emotional functioning. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012; 40:1167-1177.

21. Chavira DA, Stein MB, Malcarne VL. Scrutinizing the relationship between shyness and social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16:585-598.

22. Schneier FR, Blanco C, Antia SX, et al. The social anxiety spectrum. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;25:757-774.

23. Stein MB, Chavira DA, Jang KL. Bringing up bashful baby: developmental pathways to social phobia. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2001;24:797-818.

24. Cooper PJ, Eke M. Childhood shyness and maternal social phobia: a community study. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:439-443.

25. Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC, et al. Differentiating social phobia from shyness. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:469-476.

26. Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141-173.

27. Dalrymple, KL, Martinez J, Tepe E, et al. A clinically useful social anxiety disorder outcome scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):758-765.

28. Connor KM, Kobak KA, Churchill LE, et al. Mini-SPIN: a brief screening assessment for generalized social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14(2):137-140.

29. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997.

30. Conrad P. Medicalization and social control. Ann Rev Sociology. 1992;18:209-232.

31. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I. Clinician recognition of anxiety disorders in depressed outpatients. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:325-333.

32. Gelernter CS, Uhde TW, Cimbolic P, et al. Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:938-945.

33. Otto MW, Smits JA, Reese HE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 5):34-41.

34. Blanco C, Bragdon LB, Schneier FR, et al. The evidence-based pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:235-249.

1. Bruce LC, Coles ME, Heimberg RG. Social phobia and social anxiety disorder: effect of disorder name on recommendation for treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(5):538.

2. Bögels SM, Alden L, Beidel DC, et al. Social anxiety disorder: questions and answers for the DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:168-189.

3. Wakefield JC, Horwitz AV, Schmitz MF. Are we overpathologizing the socially anxious? Social phobia from a harmful dysfunction perspective. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):317-319.

4. Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Justifying the diagnostic status of social phobia: a reply to Wakefield, Horwitz, and Schmitz. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(6):320-323.

5. Scott S. The medicalisation of shyness: from social misfits to social fitness. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2006;28(2):133-153.

6. Wakefield JC. The DSM-5 debate over the bereavement exclusion: psychiatric diagnosis and the future of empirically supported treatment. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013; 33(7):825-845.

7. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: the process and practice of mindful change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012.

8. Kupfer DJ, First MB, Regier DA, eds. A research agenda for DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2002.

9. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

10. Dalrymple KL, Zimmerman M. Does comorbid social anxiety disorder impact the clinical presentation of principal major depressive disorder? J Affect Disord. 2007;100:241-247.

11. Dalrymple KL. Issues and controversies surrounding the diagnosis and treatment of social anxiety disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(8):993-1008.

12. Furmark T, Tillfors M, Everz PO, et al. Social phobia in the general population: prevalence and sociodemographic profile. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:416-424.

13. Narrow WE, Rae DS, Robins LN, et al. Revised prevalence estimates of mental disorders in the United States: using a clinical significance criterion to reconcile 2 surveys’ estimates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:115-123.

14. Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC. Shyness: relationship to social phobia and other psychiatric disorders. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:209-221.

15. Hofmann SG, Moscovitch DA, Hyo-Jin K. Autonomic correlates of social anxiety and embarrassment in shy and non-shy individuals. Int J Psychophysiology. 2006;61:134-142.

16. Kagan J. Temperamental contributions to affective and behavioral profiles in childhood. In: Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, eds. From social anxiety to social phobia: multiple perspectives. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001:216-234.

17. Cox BJ, MacPherson PS, Enns MW. Psychiatric correlates of childhood shyness in a nationally representative sample. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1019-1027.

18. Burstein M, Ameli-Grillon L, Merikangas KR. Shyness versus social phobia in US youth. Pediatrics. 2011;128:917-925.

19. Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Micco J, Henin A, et al. Behavioral inhibition. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:357-367.

20. Karevold E, Ystrom E, Coplan RJ, et al. A prospective longitudinal study of shyness from infancy to adolescence: stability, age-related changes, and prediction of socio-emotional functioning. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2012; 40:1167-1177.

21. Chavira DA, Stein MB, Malcarne VL. Scrutinizing the relationship between shyness and social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2002;16:585-598.

22. Schneier FR, Blanco C, Antia SX, et al. The social anxiety spectrum. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;25:757-774.

23. Stein MB, Chavira DA, Jang KL. Bringing up bashful baby: developmental pathways to social phobia. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2001;24:797-818.

24. Cooper PJ, Eke M. Childhood shyness and maternal social phobia: a community study. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:439-443.

25. Heiser NA, Turner SM, Beidel DC, et al. Differentiating social phobia from shyness. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:469-476.

26. Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1987;22:141-173.

27. Dalrymple, KL, Martinez J, Tepe E, et al. A clinically useful social anxiety disorder outcome scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(7):758-765.

28. Connor KM, Kobak KA, Churchill LE, et al. Mini-SPIN: a brief screening assessment for generalized social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2001;14(2):137-140.

29. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1997.

30. Conrad P. Medicalization and social control. Ann Rev Sociology. 1992;18:209-232.

31. Zimmerman M, Chelminski I. Clinician recognition of anxiety disorders in depressed outpatients. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:325-333.

32. Gelernter CS, Uhde TW, Cimbolic P, et al. Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacological treatments of social phobia: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:938-945.

33. Otto MW, Smits JA, Reese HE. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 5):34-41.

34. Blanco C, Bragdon LB, Schneier FR, et al. The evidence-based pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:235-249.