User login

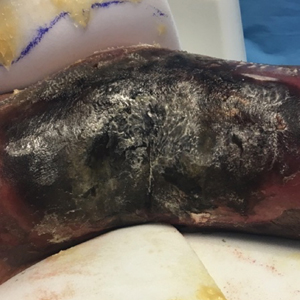

Extensive Purpura and Necrosis of the Leg

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Mucormycosis

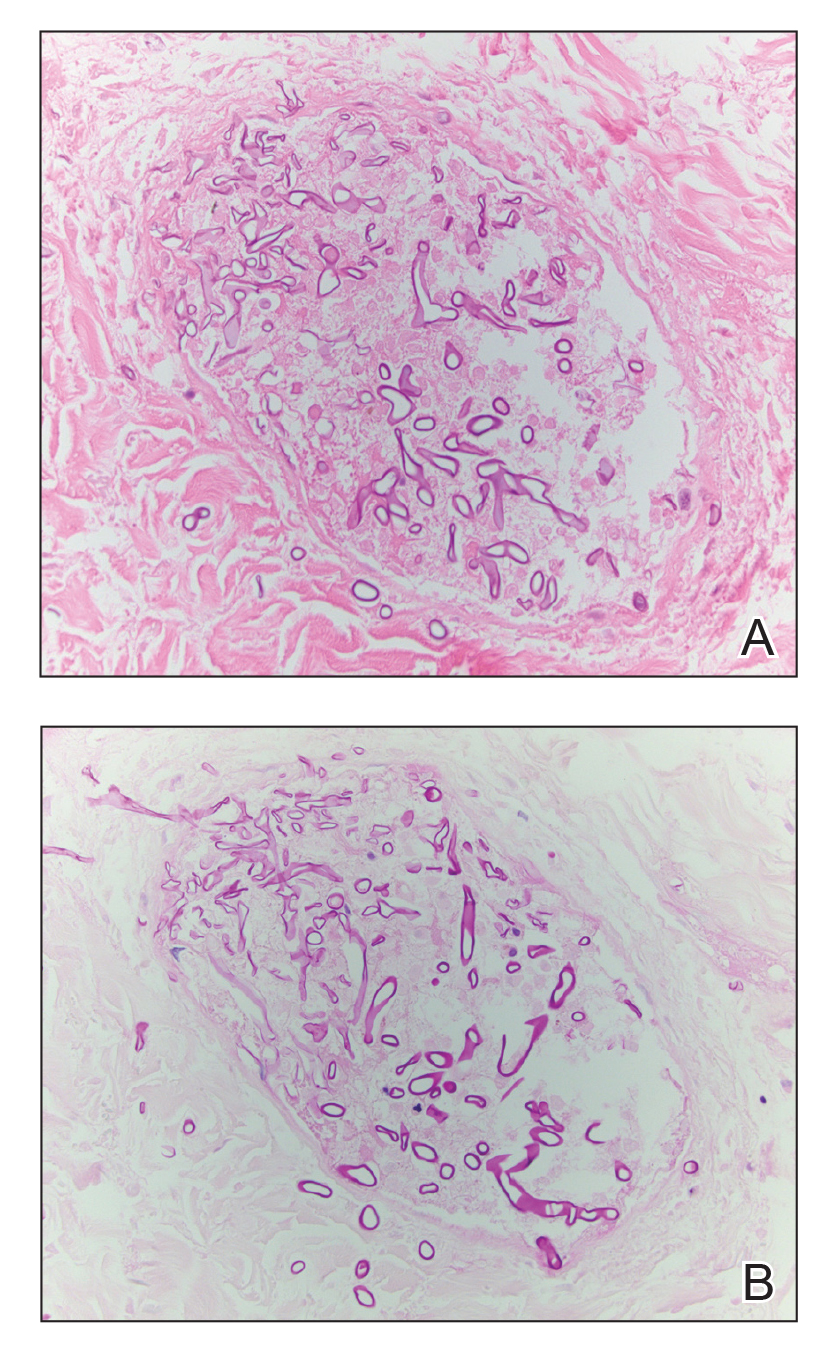

Histopathologic examination of a 6-mm punch biopsy of the edge of the lesion revealed numerous intravascular, broad, nonseptate hyphae in the deep vessels and perivascular dermis that stained bright red with periodic acid-Schiff (Figure). Acid-fast bacilli and Gram stains were negative. Tissue culture grew Rhizopus species. Given the patient's overall poor prognosis, her family decided to pursue hospice care following this diagnosis.

Mucormycosis (formerly zygomycosis) refers to infections from a variety of genera of fungi, most commonly Mucor and Rhizopus, that cause infections primarily in immunocompromised individuals.1 Mucormycosis infections are characterized by tissue necrosis that results from invasion of the vasculature and subsequent thrombosis. The typical presentation of cutaneous mucormycosis is a necrotic eschar accompanied by surrounding erythema and induration.2 Diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, requiring additional testing with skin biopsy and tissue cultures for confirmation.

Cutaneous infection is the third most common presentation of mucormycosis, following rhinocerebral and pulmonary involvement.1 Although rhinocerebral and pulmonary infections normally are caused by inhalation of spores, cutaneous mucormycosis typically is caused by local inoculation, often following skin trauma.2 The skin is the most common location of iatrogenic mucormycosis, often from skin injury related to surgery, catheters, and adhesive tape.3 Most patients with cutaneous mucormycosis have underlying conditions such as hematologic malignancies, diabetes mellitus, or immunosuppression.1 However, outbreaks have occurred in immunocompetent patients following natural disasters.4 Cutaneous mucormycosis disseminates in 13% to 20% of cases in which mortality rates typically exceed 90%.1

Treatment consists of prompt surgical debridement and antifungal agents such as amphotericin B, posaconazole, and isavuconazonium sulfate.1 Our patient had multiple risk factors for infection, including hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, prolonged neutropenia, and treatment with eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody against C5 that blocks the terminal complement cascade. Eculizumab has been associated with increased risk for meningococcemia,5 but the association with mucormycosis is rare. We highlight the importance of recognizing and promptly diagnosing cutaneous mucormycosis given the difficulty of treating this disease and its poor prognosis.

Disseminated aspergillosis demonstrates septate rather than nonseptate hyphae on biopsy. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and purpura fulminans may be associated with thrombocytopenia but demonstrate thrombotic microangiopathy on biopsy. Pyoderma gangrenosum demonstrates neutrophilic infiltrate on biopsy.

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634-653.

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S23-S34.

- Rammaert B, Lanternier F, Zahar JR, et al. Healthcare-associated mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S44-S54.

- Neblett Fanfair R, Benedict K, Bos J, et al. Necrotizing cutaneous mucormycosis after a tornado in Joplin, Missouri, in 2011. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2214-2225.

- McNamara LA, Topaz N, Wang X, et al. High risk for invasive meningococcal disease among patients receiving eculizumab (Soliris) despite receipt of meningococcal vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:734-737.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Mucormycosis

Histopathologic examination of a 6-mm punch biopsy of the edge of the lesion revealed numerous intravascular, broad, nonseptate hyphae in the deep vessels and perivascular dermis that stained bright red with periodic acid-Schiff (Figure). Acid-fast bacilli and Gram stains were negative. Tissue culture grew Rhizopus species. Given the patient's overall poor prognosis, her family decided to pursue hospice care following this diagnosis.

Mucormycosis (formerly zygomycosis) refers to infections from a variety of genera of fungi, most commonly Mucor and Rhizopus, that cause infections primarily in immunocompromised individuals.1 Mucormycosis infections are characterized by tissue necrosis that results from invasion of the vasculature and subsequent thrombosis. The typical presentation of cutaneous mucormycosis is a necrotic eschar accompanied by surrounding erythema and induration.2 Diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, requiring additional testing with skin biopsy and tissue cultures for confirmation.

Cutaneous infection is the third most common presentation of mucormycosis, following rhinocerebral and pulmonary involvement.1 Although rhinocerebral and pulmonary infections normally are caused by inhalation of spores, cutaneous mucormycosis typically is caused by local inoculation, often following skin trauma.2 The skin is the most common location of iatrogenic mucormycosis, often from skin injury related to surgery, catheters, and adhesive tape.3 Most patients with cutaneous mucormycosis have underlying conditions such as hematologic malignancies, diabetes mellitus, or immunosuppression.1 However, outbreaks have occurred in immunocompetent patients following natural disasters.4 Cutaneous mucormycosis disseminates in 13% to 20% of cases in which mortality rates typically exceed 90%.1

Treatment consists of prompt surgical debridement and antifungal agents such as amphotericin B, posaconazole, and isavuconazonium sulfate.1 Our patient had multiple risk factors for infection, including hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, prolonged neutropenia, and treatment with eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody against C5 that blocks the terminal complement cascade. Eculizumab has been associated with increased risk for meningococcemia,5 but the association with mucormycosis is rare. We highlight the importance of recognizing and promptly diagnosing cutaneous mucormycosis given the difficulty of treating this disease and its poor prognosis.

Disseminated aspergillosis demonstrates septate rather than nonseptate hyphae on biopsy. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and purpura fulminans may be associated with thrombocytopenia but demonstrate thrombotic microangiopathy on biopsy. Pyoderma gangrenosum demonstrates neutrophilic infiltrate on biopsy.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Mucormycosis

Histopathologic examination of a 6-mm punch biopsy of the edge of the lesion revealed numerous intravascular, broad, nonseptate hyphae in the deep vessels and perivascular dermis that stained bright red with periodic acid-Schiff (Figure). Acid-fast bacilli and Gram stains were negative. Tissue culture grew Rhizopus species. Given the patient's overall poor prognosis, her family decided to pursue hospice care following this diagnosis.

Mucormycosis (formerly zygomycosis) refers to infections from a variety of genera of fungi, most commonly Mucor and Rhizopus, that cause infections primarily in immunocompromised individuals.1 Mucormycosis infections are characterized by tissue necrosis that results from invasion of the vasculature and subsequent thrombosis. The typical presentation of cutaneous mucormycosis is a necrotic eschar accompanied by surrounding erythema and induration.2 Diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, requiring additional testing with skin biopsy and tissue cultures for confirmation.

Cutaneous infection is the third most common presentation of mucormycosis, following rhinocerebral and pulmonary involvement.1 Although rhinocerebral and pulmonary infections normally are caused by inhalation of spores, cutaneous mucormycosis typically is caused by local inoculation, often following skin trauma.2 The skin is the most common location of iatrogenic mucormycosis, often from skin injury related to surgery, catheters, and adhesive tape.3 Most patients with cutaneous mucormycosis have underlying conditions such as hematologic malignancies, diabetes mellitus, or immunosuppression.1 However, outbreaks have occurred in immunocompetent patients following natural disasters.4 Cutaneous mucormycosis disseminates in 13% to 20% of cases in which mortality rates typically exceed 90%.1

Treatment consists of prompt surgical debridement and antifungal agents such as amphotericin B, posaconazole, and isavuconazonium sulfate.1 Our patient had multiple risk factors for infection, including hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, prolonged neutropenia, and treatment with eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody against C5 that blocks the terminal complement cascade. Eculizumab has been associated with increased risk for meningococcemia,5 but the association with mucormycosis is rare. We highlight the importance of recognizing and promptly diagnosing cutaneous mucormycosis given the difficulty of treating this disease and its poor prognosis.

Disseminated aspergillosis demonstrates septate rather than nonseptate hyphae on biopsy. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and purpura fulminans may be associated with thrombocytopenia but demonstrate thrombotic microangiopathy on biopsy. Pyoderma gangrenosum demonstrates neutrophilic infiltrate on biopsy.

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634-653.

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S23-S34.

- Rammaert B, Lanternier F, Zahar JR, et al. Healthcare-associated mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S44-S54.

- Neblett Fanfair R, Benedict K, Bos J, et al. Necrotizing cutaneous mucormycosis after a tornado in Joplin, Missouri, in 2011. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2214-2225.

- McNamara LA, Topaz N, Wang X, et al. High risk for invasive meningococcal disease among patients receiving eculizumab (Soliris) despite receipt of meningococcal vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:734-737.

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634-653.

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S23-S34.

- Rammaert B, Lanternier F, Zahar JR, et al. Healthcare-associated mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S44-S54.

- Neblett Fanfair R, Benedict K, Bos J, et al. Necrotizing cutaneous mucormycosis after a tornado in Joplin, Missouri, in 2011. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2214-2225.

- McNamara LA, Topaz N, Wang X, et al. High risk for invasive meningococcal disease among patients receiving eculizumab (Soliris) despite receipt of meningococcal vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:734-737.

A 57-year-old woman presented with expanding purpura on the left leg of 2 weeks’ duration following a recent hematopoietic stem cell transplant for refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Prior to dermatologic consultation, the patient had been hospitalized for 2 months following the transplant due to Clostridium difficile colitis, Enterococcus faecium bacteremia, cardiac arrest, delayed engraftment with pancytopenia, and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome with acute renal failure requiring hemodialysis and treatment with eculizumab. Her care team in the hospital initially noticed a small purpuric lesion on the posterior aspect of the left knee. The patient subsequently developed persistent fevers and expansion of the lesion, which prompted consultation of the dermatology service. Physical examination revealed a 22×10-cm, rectangular, indurated, purpuric plaque with central dusky, violaceous to black necrosis with superficial skin sloughing and peripheral dusky erythema extending from the inner thigh to the lower leg. The left distal leg felt cool, and both dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses were absent. Laboratory test results revealed neutropenia and thrombocytopenia (white blood cell count, 0.2×103 /mm3 [reference range, 5–10×103 /mm3 ]; hematocrit, 23.2% [reference range, 41%–50%]; platelet count, 105×103 /µL [reference range, 150–350×103 /µL]). A punch biopsy was performed.

Nonpainful Ulcerations on the Nose and Forehead

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) is a rare condition occurring after injury to the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal trophic syndrome was first described in 1933 by Loveman1 as a complication of ablative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia; however, it has been observed with lesions to the central or peripheral nervous system that damage sensory components of the trigeminal nerve. In our patient, the cause was likely an infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which supplies both the cerebellum and the trigeminal nuclei in the brain stem.

Other possible causes of TTS include injury from herpes zoster ophthalmicus; vertebrobasilar insufficiency; trauma; Mycobacterium leprae neuritis; spinal cord degeneration; syringobulbia; or tumors such as astrocytomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.2 The most typical presenting manifestation is a unilateral, crescent-shaped ulceration of the nasal ala, specifically where cartilage is lacking.3 Less frequently, it affects the upper lip, cheeks, forehead, scalp, and ear. It characteristically spares the nasal tip, which derives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve.4 The affected dermatomal distribution can show anesthesia or paresthesia, promoting the urge to touch, pick, or rub the area.

Histology of the TTS lesion is nondiagnostic, usually showing a mixed dermal inflammation without evidence of infection, vasculitis, or malignancy. In our patient, Gram stain, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, and immunohistochemical stains to rule out leukemia or lymphoma were all negative. In addition, flow cytometry of the forehead tissue also was normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioides, and tuberculosis were negative.During the biopsy, the patient was noted to have anesthesia of the skin. He also admitted to facial manipulation and was noted to have blood and tissue under the fingernails on mornings when the lesion was left uncovered overnight.

Treatment of TTS often can be difficult, especially if patients do not admit to wound manipulation or if manipulation occurs during sleep. Prevention of further ulceration can sometimes be achieved by occlusive dressing alone with mupirocin. Physical barriers can be supplemented with medications such as amitriptyline, carbamazepine, diazepam, chlorpromazine, and gabapentin to attempt to reduce paresthesia.2 Psychiatric consultation can sometimes be necessary and helpful.3 Additionally, negative pressure wound therapy has been used with success in the pediatric setting when digital manipulation is difficult to control.5 More aggressive treatments include transcutaneous electrical stimulation, stellate ganglionectomy, radiotherapy, and innervated rotation flaps.6,7

In summary, recognition of this relatively rare cause of unilateral facial erosions is critical, both to prevent counterproductive treatments such as steroids and to initiate measures to prevent further trauma to the lesion.

- Loveman A. An unusual dermatosis following section of the fifth cranial nerve. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1933;28:369-375.

- Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

- Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1118.

- Setyadi HG, Cohen PR, Schulze KE, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. South Med J. 2007;100:43-48.

- Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:984-986.

- Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

- Willis M, Shockley W, Mobley SR. Treatment options in trigeminal trophic syndrome: a multi-institutional case series. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:712-716.

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) is a rare condition occurring after injury to the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal trophic syndrome was first described in 1933 by Loveman1 as a complication of ablative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia; however, it has been observed with lesions to the central or peripheral nervous system that damage sensory components of the trigeminal nerve. In our patient, the cause was likely an infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which supplies both the cerebellum and the trigeminal nuclei in the brain stem.

Other possible causes of TTS include injury from herpes zoster ophthalmicus; vertebrobasilar insufficiency; trauma; Mycobacterium leprae neuritis; spinal cord degeneration; syringobulbia; or tumors such as astrocytomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.2 The most typical presenting manifestation is a unilateral, crescent-shaped ulceration of the nasal ala, specifically where cartilage is lacking.3 Less frequently, it affects the upper lip, cheeks, forehead, scalp, and ear. It characteristically spares the nasal tip, which derives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve.4 The affected dermatomal distribution can show anesthesia or paresthesia, promoting the urge to touch, pick, or rub the area.

Histology of the TTS lesion is nondiagnostic, usually showing a mixed dermal inflammation without evidence of infection, vasculitis, or malignancy. In our patient, Gram stain, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, and immunohistochemical stains to rule out leukemia or lymphoma were all negative. In addition, flow cytometry of the forehead tissue also was normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioides, and tuberculosis were negative.During the biopsy, the patient was noted to have anesthesia of the skin. He also admitted to facial manipulation and was noted to have blood and tissue under the fingernails on mornings when the lesion was left uncovered overnight.

Treatment of TTS often can be difficult, especially if patients do not admit to wound manipulation or if manipulation occurs during sleep. Prevention of further ulceration can sometimes be achieved by occlusive dressing alone with mupirocin. Physical barriers can be supplemented with medications such as amitriptyline, carbamazepine, diazepam, chlorpromazine, and gabapentin to attempt to reduce paresthesia.2 Psychiatric consultation can sometimes be necessary and helpful.3 Additionally, negative pressure wound therapy has been used with success in the pediatric setting when digital manipulation is difficult to control.5 More aggressive treatments include transcutaneous electrical stimulation, stellate ganglionectomy, radiotherapy, and innervated rotation flaps.6,7

In summary, recognition of this relatively rare cause of unilateral facial erosions is critical, both to prevent counterproductive treatments such as steroids and to initiate measures to prevent further trauma to the lesion.

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) is a rare condition occurring after injury to the sensory roots of the trigeminal nerve. Trigeminal trophic syndrome was first described in 1933 by Loveman1 as a complication of ablative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia; however, it has been observed with lesions to the central or peripheral nervous system that damage sensory components of the trigeminal nerve. In our patient, the cause was likely an infarction of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, which supplies both the cerebellum and the trigeminal nuclei in the brain stem.

Other possible causes of TTS include injury from herpes zoster ophthalmicus; vertebrobasilar insufficiency; trauma; Mycobacterium leprae neuritis; spinal cord degeneration; syringobulbia; or tumors such as astrocytomas, meningiomas, and acoustic neuromas.2 The most typical presenting manifestation is a unilateral, crescent-shaped ulceration of the nasal ala, specifically where cartilage is lacking.3 Less frequently, it affects the upper lip, cheeks, forehead, scalp, and ear. It characteristically spares the nasal tip, which derives sensory innervation from the medial branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve.4 The affected dermatomal distribution can show anesthesia or paresthesia, promoting the urge to touch, pick, or rub the area.

Histology of the TTS lesion is nondiagnostic, usually showing a mixed dermal inflammation without evidence of infection, vasculitis, or malignancy. In our patient, Gram stain, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain, and immunohistochemical stains to rule out leukemia or lymphoma were all negative. In addition, flow cytometry of the forehead tissue also was normal. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis, syphilis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioides, and tuberculosis were negative.During the biopsy, the patient was noted to have anesthesia of the skin. He also admitted to facial manipulation and was noted to have blood and tissue under the fingernails on mornings when the lesion was left uncovered overnight.

Treatment of TTS often can be difficult, especially if patients do not admit to wound manipulation or if manipulation occurs during sleep. Prevention of further ulceration can sometimes be achieved by occlusive dressing alone with mupirocin. Physical barriers can be supplemented with medications such as amitriptyline, carbamazepine, diazepam, chlorpromazine, and gabapentin to attempt to reduce paresthesia.2 Psychiatric consultation can sometimes be necessary and helpful.3 Additionally, negative pressure wound therapy has been used with success in the pediatric setting when digital manipulation is difficult to control.5 More aggressive treatments include transcutaneous electrical stimulation, stellate ganglionectomy, radiotherapy, and innervated rotation flaps.6,7

In summary, recognition of this relatively rare cause of unilateral facial erosions is critical, both to prevent counterproductive treatments such as steroids and to initiate measures to prevent further trauma to the lesion.

- Loveman A. An unusual dermatosis following section of the fifth cranial nerve. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1933;28:369-375.

- Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

- Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1118.

- Setyadi HG, Cohen PR, Schulze KE, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. South Med J. 2007;100:43-48.

- Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:984-986.

- Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

- Willis M, Shockley W, Mobley SR. Treatment options in trigeminal trophic syndrome: a multi-institutional case series. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:712-716.

- Loveman A. An unusual dermatosis following section of the fifth cranial nerve. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1933;28:369-375.

- Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

- Finlay AY. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:1118.

- Setyadi HG, Cohen PR, Schulze KE, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome. South Med J. 2007;100:43-48.

- Fredeking AE, Silverman RA. Successful treatment of trigeminal trophic syndrome in a 6-year-old boy with negative pressure wound therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:984-986.

- Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

- Willis M, Shockley W, Mobley SR. Treatment options in trigeminal trophic syndrome: a multi-institutional case series. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:712-716.

A 57-year-old man with a history of multiple cerebrovascular accidents was transferred from an outside hospital to our inpatient rheumatology service with nonpainful erosions of the forehead and nasal ala of 6 months’ duration. The patient reported that he initially developed a sore on the nose months prior to presentation with worsening sensations of itching and tingling on the forehead and nose. He also noted a headache and gradual loss of vision in the right eye. The patient was immunocompetent and denied arthralgia or any other skin lesions.