User login

Intralymphatic Histiocytosis Treated With Intralesional Triamcinolone Acetonide and Pressure Bandage

Intralymphatic histiocytosis was first described in 1994.1 To date, at least 70 cases have been reported in the English-language literature, the majority being associated with systemic or local inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), malignancy, and metal prostheses. The remaining cases arose independent of any detectable disease process.2 The clinical lesion localizes to areas around surgical scars or inflamed joints and generally presents with erythematous livedoid papules and plaques. Because of its rarity, pathologists and clinicians may be unfamiliar with this entity, leading to delayed or missed diagnoses.

Although the pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains unclear, it may be related to dysregulated immune signaling. The condition follows a chronic, relapsing-remitting course that has shown variable response to topical and systemic treatments. We present a rare case of intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with joint replacement/metal prosthesis3-14 that was responsive to a novel treatment with intralesional steroid injection and pressure bandage.

Case Report

An 89-year-old woman presented with a relapsing and remitting rash on the right calf and popliteal fossa of 11 months’ duration. It was becoming more painful over time and recently began to hurt when walking. Her medical history was remarkable for deep vein thromboses of the bilateral legs, Factor V Leiden deficiency, osteoarthritis, and a popliteal (Baker) cyst on the right leg that ruptured 22 months prior to presentation. Her surgical history included bilateral knee replacements (10 years and 2 years prior to the current presentation for the right and left knees, respectively). Her international normalized ratio (2.0) was therapeutic on warfarin.

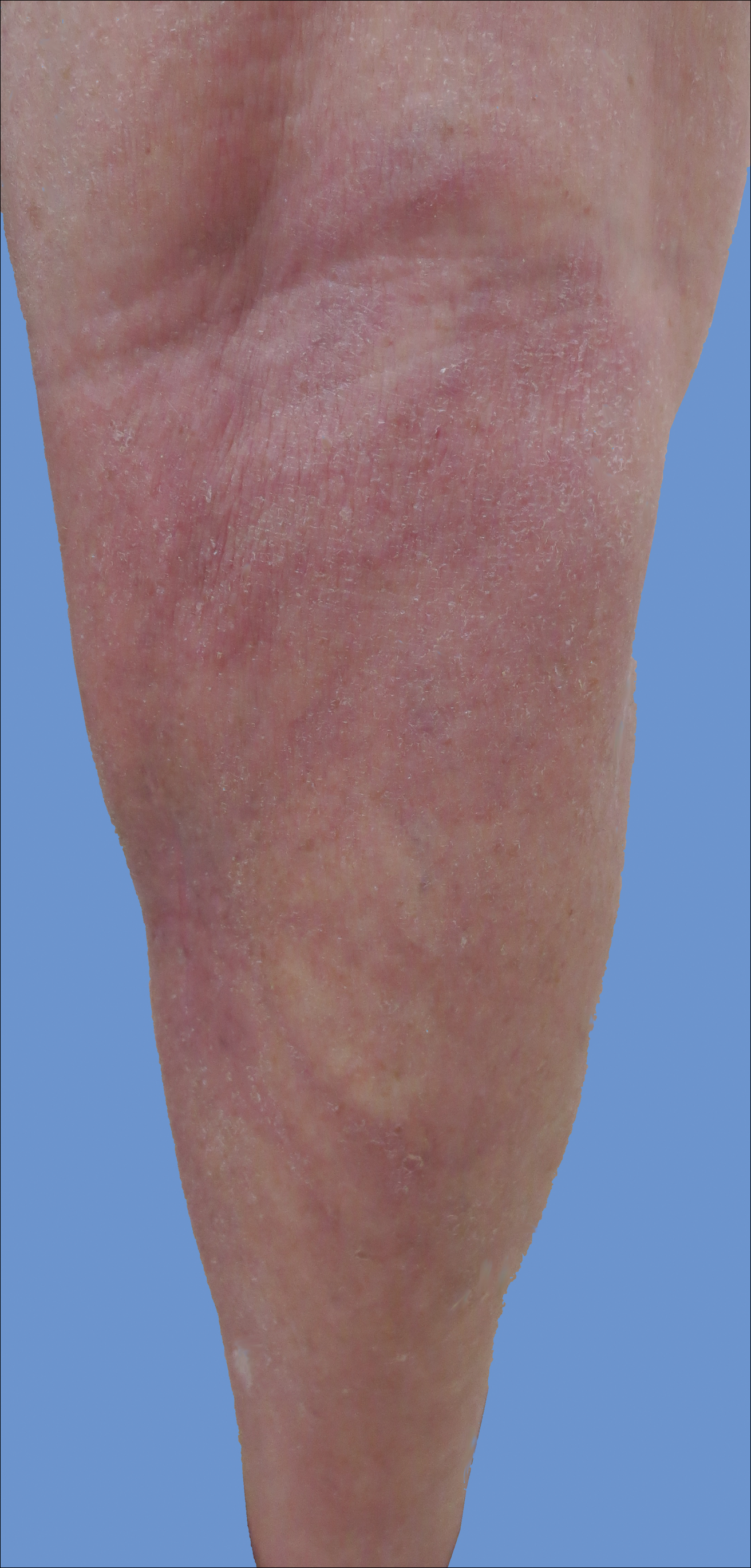

Initially, swelling, pain, and redness developed in the right calf, and recurrent right-leg deep venous thrombosis was ruled out by Doppler ultrasound. The findings were considered to be secondary to inflammation from a popliteal cyst. Symptoms persisted despite application of warm compresses, leg elevation, and compression stockings. Treatment with doxycycline prescribed by the patient’s primary care physician 9 months prior for presumed cellulitis produced little improvement. Physical examination revealed a well-healed vertical scar on the right calf from an incisional biopsy within an 8-cm, tender, erythematous, indurated, sclerotic plaque with erythematous streaks radiating from the center of the plaque (Figure 1). There also was red-brown, indurated discoloration on the right shin.

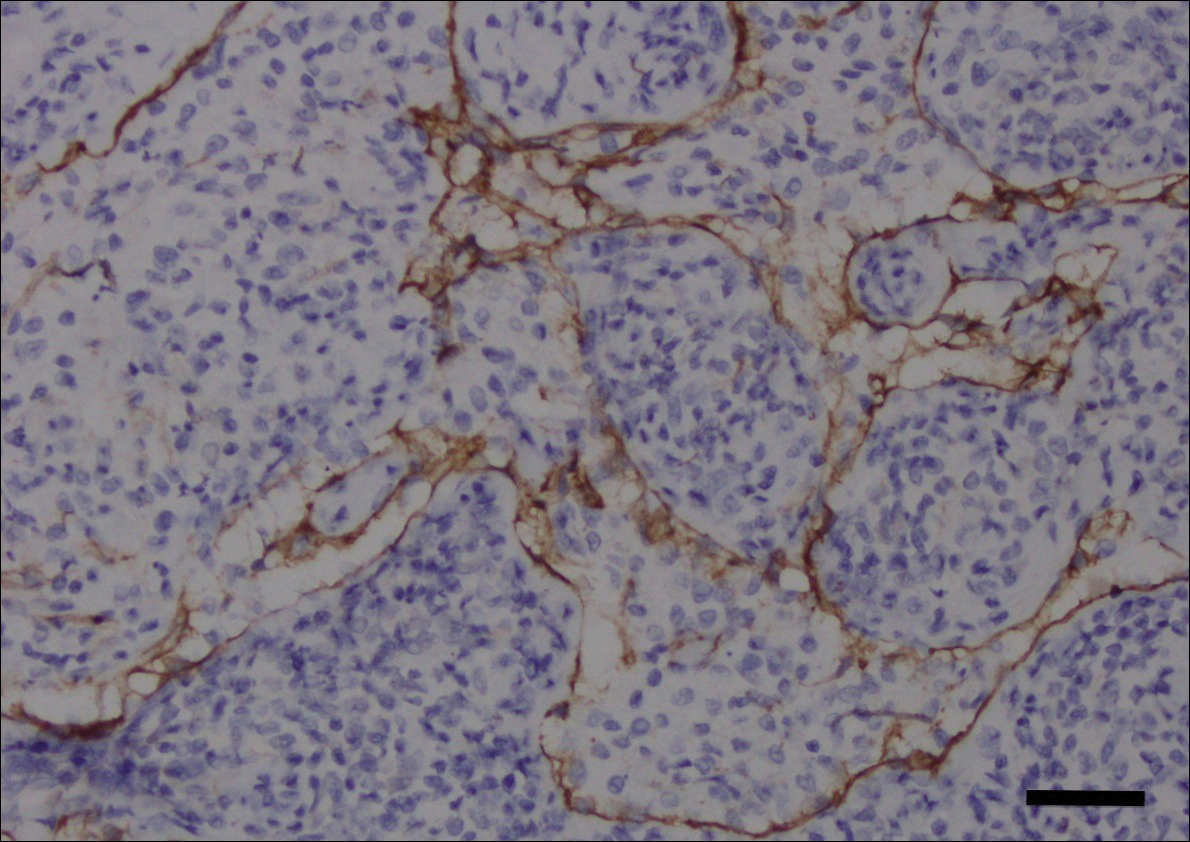

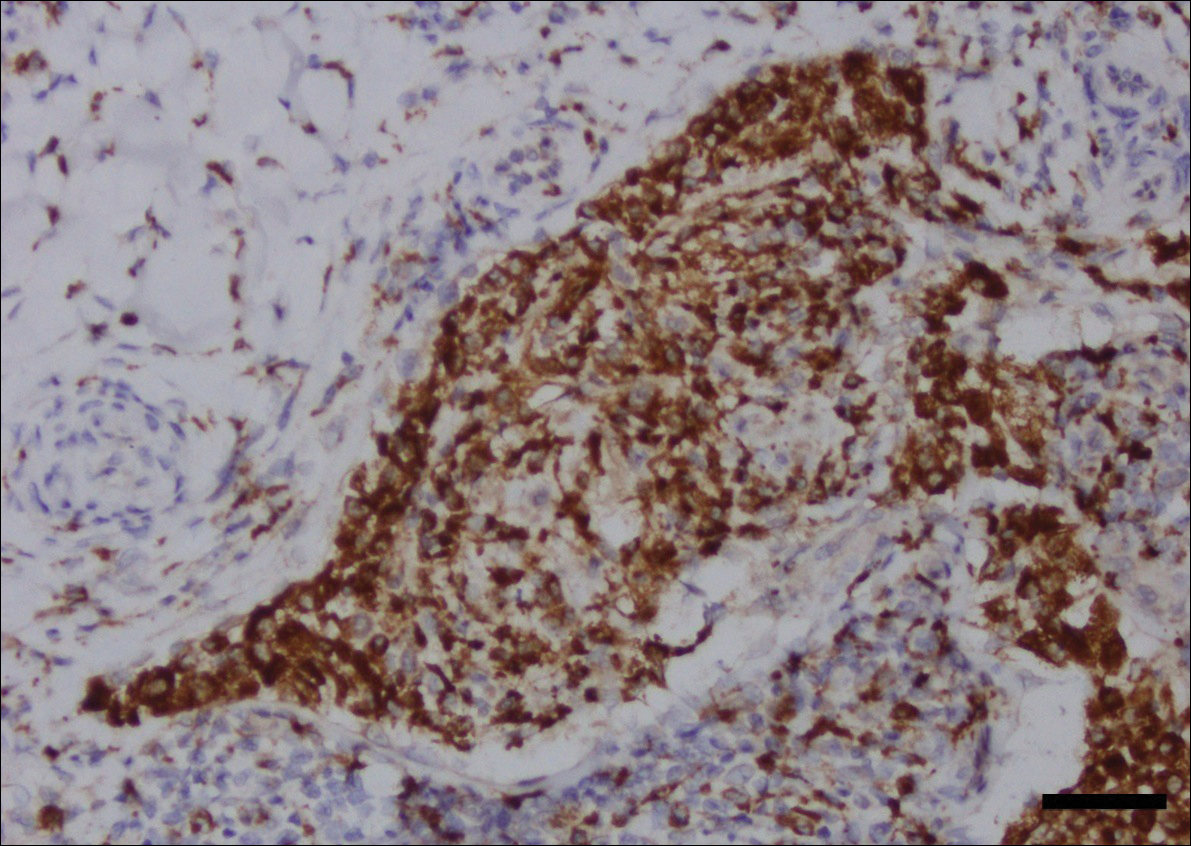

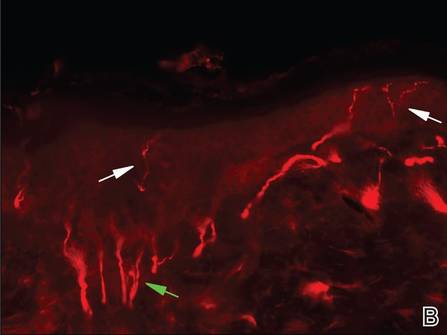

Fine-needle aspiration of the lesion revealed red blood cells and histiocytes. Laboratory studies showed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 74 mm/h (reference range, 0–30 mm/h) and a C-reactive protein level of 39 mg/L (reference range, 0–10 mg/L). An incisional biopsy including the muscular fascia showed dense dermal fibrosis with chronic inflammation and scarring. A dermatopathologist (G. A. S.) reviewed the case and confirmed variable fibrosis and chronic inflammation associated with edema in the dermis and epidermal acanthosis. Inspection of vessels in the mid to upper dermis in one area revealed stellate, thin-walled, vascular structures that contained bland epithelioid cells lining the lumen as well as packed within the vessels. The epithelioid cells did not show atypia or mitotic figures, and they did not show intracytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 2). Immunocytochemical staining for D2-40 was strongly positive in cells lining the vessels, consistent with lymphatics (Figure 3). CD68 immunohistochemistry for histiocytes stained the cells within the lymphatics (Figure 4). A diagnosis of intralymphatic histiocytosis was made.

Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/cc×1.6 cc was injected into the plaque once monthly for 2 consecutive months, and daily compression with a pressure bandage of the right lower leg was initiated. Four months after the first treatment with this regimen, the plaque was smaller and no longer sclerotic or painful, and the erythema was markedly reduced (Figure 5). Clinical and symptomatic improvement continued at 1-year follow-up.

Comment

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous disorder defined histologically by histiocytes within the lumina of lymphatics. In addition to the current case, our review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term intralymphatic histiocytosis yielded more than 70 total cases. The condition has a slight female predominance and typically is seen in individuals over the age of 60 years (age range, 16–89 years).12 Many cases are associated with RA/elevated rheumatoid factor.2,4,8,15-30 At least 9 cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis were associated with premalignant or malignant conditions (ie, adenocarcinoma of the breasts, lungs, and colon; Merkel cell carcinoma; melanoma; melanoma in situ; Mullerian carcinoma, gammopathy).4,15,31-34 Primary disease, defined as occurring in patients who are otherwise healthy, was noted in at least 10 cases.1,2,4,12,35,36 Finally, intralymphatic histiocytosis was identified in areas adjacent to metal implants and joint replacements or exploration in approximately 15 cases (including the current case).3-14,29,37

The condition presents with papules, plaques, and nodules in the setting of characteristic livedoid discoloration; however, some patients present with nonspecific nodules or plaques. Lesions may be symptomatic (eg, pruritic, tender) or asymptomatic. The histologic features of intralymphatic histiocytosis are distinctive but may be focal, as in our case, and the diagnosis is easily missed. The histologic differential diagnosis includes diseases in which intravascular accumulations of cells may be seen, including intravascular B-cell lymphoma, which can be excluded with stains that detect B cells (CD20/CD79a), and reactive angioendotheliomatosis, a benign proliferation of endothelial cells, which may be excluded with stains against endothelial markers (CD31/CD34). The course typically is chronic, and treatment with topical steroids,3,9,15,22,26 cyclophosphamide,15 local radiation,1 thalidomide,35 pentoxifylline,7 and RA medications (eg, prednisolone, methotrexate, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hydroxychloroquine) generally are ineffective.2,16,20,25 Symptoms may improve with joint replacement,4 excision of the involved lesion, treatment of an associated malignancy/infection,33,36,38,39 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, intra-articular steroid injection,18 amoxicillin and aspirin,19 infliximab,25 pressure bandage application,26 steroid-containing adhesive application,18 arthrocentesis,3,27 oral pentoxifylline,21 tacrolimus,29 CO2 laser,40 prednisolone,41 and tocilizumab.28 Treatment of associated RA is beneficial in rare cases.2,15,20,25,26

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis has not been elucidated with certainty but may represent an abnormal proliferative response of histiocytes and vessels in response to chronic systemic or local inflammation. Lymphangiectasis caused by lymphatic obstruction secondary to trauma, surgical manipulation, or chronic inflammation can promote lymphostasis and slowed clearance of antigens producing an accumulation of histiocytes and subsequent local immunologic reactions, thus an “immunocompromised district” is formed.42 It also is thought that rheumatic or prosthetic joints produce inflammatory mediator–rich (namely tumor necrosis factor α) synovial fluid that drains and collects within the dilated lymphatics, creating a nidus for histiocytes.1,5 In one case, treatment with an anti–tumor necrosis factor antibody (infliximab) improved the skin presentation and rheumatoid joint pain.25 Bakr et al2 noted an association with increased intralymphatic macrophage HLA-DR expression. This T-cell surface receptor typically is upregulated in cases of chronic antigen stimulation and autoimmune conditions.

Conclusion

Our patient had a history of a joint prosthesis and a popliteal cyst, which could have altered lymphatic drainage promoting abnormal immune cell trafficking contributing to the development of intralymphatic histiocytosis. The response to intralesional steroids supports this pathogenic hypothesis. Specifically, direct injection of the area suppressed the immune dysregulation, while compression lessened the degree of lymphostasis. In light of previously reported cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis in association with metal implants,3-9 we suggest that the condition should be considered in patients with chronic painful livedoid nodules or plaques around an affected joint, even in the absence of RA. The dermatopathologist should be warned to search carefully for the subtle but distinctive histologic features of the disease that confirm the diagnosis. Treatment with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide with an overlying pressure wrap has minimal side effects and can work quickly with sustained benefits.

- O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

- Bakr F, Webber N, Fassihi H, et al. Primary and secondary intralymphatic histiocytosis [published online January 17, 2014]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:927-933.

- Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants [published online November 10, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.

- Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

- Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

- Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants [published online March 6, 2011]. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

- de Unamuno Bustos B, García Rabasco A, Ballester Sánchez R, et al. Erythematous indurated plaque on the right upper limb. intralymphatic histiocytosis (IH) associated with orthopedic metal implant. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:547-549.

- Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

- Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

- Bidier M, Hamsch C, Kutzner H, et al. Two cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis following hip replacement [published online June 9, 2015]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:700-702.

- Darling MD, Akin R, Tarbox MB, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis overlying hip implantation treated with pentoxifilline. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2015;29(1 suppl):117-121.

- Demirkesen C, Kran T, Leblebici C, et al. Intravascular/intralymphatic histiocytosis: a report of 3 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:783-789.

- Gómez-Sánchez ME, Azaña-Defez JM, Martínez-Martínez ML, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: a report of 2 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:E1-E5.

- Haitz KA, Chapman MS, Seidel GD. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with an orthopedic metal implant. Cutis. 2016;97:E12-E14.

- Rieger E, Soyer HP, Leboit PE, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis or intravascular histiocytosis? an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study in two cases of intravascular histiocytic cell proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:497-504.

- Pruim B, Strutton G, Congdon S, et al. Cutaneous histiocytic lymphangitis: an unusual manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:101-105.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN. The spectrum of cutaneous lesions in rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical and pathological study of 43 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:1-10.

- Takiwaki H, Adachi A, Kohno H, et al. Intravascular or intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a report of 4 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:585-590.

- Mensing CH, Krengel S, Tronnier M, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis: is it “intravascular histiocytosis”? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:216-219.

- Okazaki A, Asada H, Niizeki H, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case with lymphatic endothelial proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1385-1387.

- Catalina-Fernández I, Alvárez AC, Martin FC, et al. Cutaneous intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:165-168.

- Nishie W, Sawamura D, Iitoyo M, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology. 2008;217:144-145.

- Okamoto N, Tanioka M, Yamamoto T, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:516-518.

- Huang H-Y, Liang C-W, Hu S-L, et al. Cutaneous intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E302-E303.

- Sakaguchi M, Nagai H, Tsuji G, et al. Effectiveness of infliximab for intralymphatic histiocytosis with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:131-133.

- Washio K, Nakata K, Nakamura A, et al. Pressure bandage as an effective treatment for intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology. 2011;223:20-24.

- Kaneko T, Takeuchi S, Nakano H, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with rheumatoid arthritis: possible association with the joint involvement. Case Reports Clin Med. 2014;3:149-152.

- Nakajima T, Kawabata D, Nakabo S, et al. Successful treatment with tocilizumab in a case of intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 2014;53:2255-2258.

- Tsujiwaki M, Hata H, Miyauchi T, et al. Warty intralymphatic histiocytosis successfully treated with topical tacrolimus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2267-2269.

- Tanaka M, Funasaka Y, Tsuruta K, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with massive interstitial granulomatous foci in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:237-238.

- Cornejo KM, Cosar EF, O’Donnell P. Cutaneous intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:568-570.

- Tran TAN, Tran Q, Carlson JA. Intralymphatic histiocytosis of the appendix and fallopian tube associated with primary peritoneal high-grade, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of Müllerian origin. Int J Surg Pathol. 2017;25:357-364.

- Echeverría-García B, Botella-Estrada R, Requena C, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis and cancer of the colon [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:257-262.

- Ergen EN, Zwerner JP. Cover image: intralymphatic histiocytosis with giant blanching violaceous plaques. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:325-326.

- Wang Y, Yang H, Tu P. Upper facial swelling: an uncommon manifestation of intralymphatic histiocytosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:814-815.

- Rhee D-Y, Lee D-W, Chang S-E, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis without rheumatoid arthritis. J Dermatol. 2008;35:691-693.

- Gilchrest BA, Eller MS, Geller AC, et al. The pathogenesis of melanoma induced by ultraviolet radiation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1341-1348.

- Asagoe K, Torigoe R, Ofuji R, et al. Reactive intravascular histiocytosis associated with tonsillitis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:560-563.

- Pouryazdanparast P, Yu L, Dalton VK, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis presenting with extensive vulvar necrosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;(36 suppl 1):1-7.

- Reznitsky M, Daugaard S, Charabi BW. Two rare cases of laryngeal intralymphatic histiocytosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:783-788.

- Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, Manabe T, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis comprises M2 macrophages in superficial dermal lymphatics with or without smooth muscles. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:898-902.

- Piccolo V, Ruocco E, Russo T, et al. A possible relationship between metal implant-induced intralymphatic histiocytosis and the concept of the immunocompromised district. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E365.

Intralymphatic histiocytosis was first described in 1994.1 To date, at least 70 cases have been reported in the English-language literature, the majority being associated with systemic or local inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), malignancy, and metal prostheses. The remaining cases arose independent of any detectable disease process.2 The clinical lesion localizes to areas around surgical scars or inflamed joints and generally presents with erythematous livedoid papules and plaques. Because of its rarity, pathologists and clinicians may be unfamiliar with this entity, leading to delayed or missed diagnoses.

Although the pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains unclear, it may be related to dysregulated immune signaling. The condition follows a chronic, relapsing-remitting course that has shown variable response to topical and systemic treatments. We present a rare case of intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with joint replacement/metal prosthesis3-14 that was responsive to a novel treatment with intralesional steroid injection and pressure bandage.

Case Report

An 89-year-old woman presented with a relapsing and remitting rash on the right calf and popliteal fossa of 11 months’ duration. It was becoming more painful over time and recently began to hurt when walking. Her medical history was remarkable for deep vein thromboses of the bilateral legs, Factor V Leiden deficiency, osteoarthritis, and a popliteal (Baker) cyst on the right leg that ruptured 22 months prior to presentation. Her surgical history included bilateral knee replacements (10 years and 2 years prior to the current presentation for the right and left knees, respectively). Her international normalized ratio (2.0) was therapeutic on warfarin.

Initially, swelling, pain, and redness developed in the right calf, and recurrent right-leg deep venous thrombosis was ruled out by Doppler ultrasound. The findings were considered to be secondary to inflammation from a popliteal cyst. Symptoms persisted despite application of warm compresses, leg elevation, and compression stockings. Treatment with doxycycline prescribed by the patient’s primary care physician 9 months prior for presumed cellulitis produced little improvement. Physical examination revealed a well-healed vertical scar on the right calf from an incisional biopsy within an 8-cm, tender, erythematous, indurated, sclerotic plaque with erythematous streaks radiating from the center of the plaque (Figure 1). There also was red-brown, indurated discoloration on the right shin.

Fine-needle aspiration of the lesion revealed red blood cells and histiocytes. Laboratory studies showed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 74 mm/h (reference range, 0–30 mm/h) and a C-reactive protein level of 39 mg/L (reference range, 0–10 mg/L). An incisional biopsy including the muscular fascia showed dense dermal fibrosis with chronic inflammation and scarring. A dermatopathologist (G. A. S.) reviewed the case and confirmed variable fibrosis and chronic inflammation associated with edema in the dermis and epidermal acanthosis. Inspection of vessels in the mid to upper dermis in one area revealed stellate, thin-walled, vascular structures that contained bland epithelioid cells lining the lumen as well as packed within the vessels. The epithelioid cells did not show atypia or mitotic figures, and they did not show intracytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 2). Immunocytochemical staining for D2-40 was strongly positive in cells lining the vessels, consistent with lymphatics (Figure 3). CD68 immunohistochemistry for histiocytes stained the cells within the lymphatics (Figure 4). A diagnosis of intralymphatic histiocytosis was made.

Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/cc×1.6 cc was injected into the plaque once monthly for 2 consecutive months, and daily compression with a pressure bandage of the right lower leg was initiated. Four months after the first treatment with this regimen, the plaque was smaller and no longer sclerotic or painful, and the erythema was markedly reduced (Figure 5). Clinical and symptomatic improvement continued at 1-year follow-up.

Comment

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous disorder defined histologically by histiocytes within the lumina of lymphatics. In addition to the current case, our review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term intralymphatic histiocytosis yielded more than 70 total cases. The condition has a slight female predominance and typically is seen in individuals over the age of 60 years (age range, 16–89 years).12 Many cases are associated with RA/elevated rheumatoid factor.2,4,8,15-30 At least 9 cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis were associated with premalignant or malignant conditions (ie, adenocarcinoma of the breasts, lungs, and colon; Merkel cell carcinoma; melanoma; melanoma in situ; Mullerian carcinoma, gammopathy).4,15,31-34 Primary disease, defined as occurring in patients who are otherwise healthy, was noted in at least 10 cases.1,2,4,12,35,36 Finally, intralymphatic histiocytosis was identified in areas adjacent to metal implants and joint replacements or exploration in approximately 15 cases (including the current case).3-14,29,37

The condition presents with papules, plaques, and nodules in the setting of characteristic livedoid discoloration; however, some patients present with nonspecific nodules or plaques. Lesions may be symptomatic (eg, pruritic, tender) or asymptomatic. The histologic features of intralymphatic histiocytosis are distinctive but may be focal, as in our case, and the diagnosis is easily missed. The histologic differential diagnosis includes diseases in which intravascular accumulations of cells may be seen, including intravascular B-cell lymphoma, which can be excluded with stains that detect B cells (CD20/CD79a), and reactive angioendotheliomatosis, a benign proliferation of endothelial cells, which may be excluded with stains against endothelial markers (CD31/CD34). The course typically is chronic, and treatment with topical steroids,3,9,15,22,26 cyclophosphamide,15 local radiation,1 thalidomide,35 pentoxifylline,7 and RA medications (eg, prednisolone, methotrexate, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hydroxychloroquine) generally are ineffective.2,16,20,25 Symptoms may improve with joint replacement,4 excision of the involved lesion, treatment of an associated malignancy/infection,33,36,38,39 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, intra-articular steroid injection,18 amoxicillin and aspirin,19 infliximab,25 pressure bandage application,26 steroid-containing adhesive application,18 arthrocentesis,3,27 oral pentoxifylline,21 tacrolimus,29 CO2 laser,40 prednisolone,41 and tocilizumab.28 Treatment of associated RA is beneficial in rare cases.2,15,20,25,26

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis has not been elucidated with certainty but may represent an abnormal proliferative response of histiocytes and vessels in response to chronic systemic or local inflammation. Lymphangiectasis caused by lymphatic obstruction secondary to trauma, surgical manipulation, or chronic inflammation can promote lymphostasis and slowed clearance of antigens producing an accumulation of histiocytes and subsequent local immunologic reactions, thus an “immunocompromised district” is formed.42 It also is thought that rheumatic or prosthetic joints produce inflammatory mediator–rich (namely tumor necrosis factor α) synovial fluid that drains and collects within the dilated lymphatics, creating a nidus for histiocytes.1,5 In one case, treatment with an anti–tumor necrosis factor antibody (infliximab) improved the skin presentation and rheumatoid joint pain.25 Bakr et al2 noted an association with increased intralymphatic macrophage HLA-DR expression. This T-cell surface receptor typically is upregulated in cases of chronic antigen stimulation and autoimmune conditions.

Conclusion

Our patient had a history of a joint prosthesis and a popliteal cyst, which could have altered lymphatic drainage promoting abnormal immune cell trafficking contributing to the development of intralymphatic histiocytosis. The response to intralesional steroids supports this pathogenic hypothesis. Specifically, direct injection of the area suppressed the immune dysregulation, while compression lessened the degree of lymphostasis. In light of previously reported cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis in association with metal implants,3-9 we suggest that the condition should be considered in patients with chronic painful livedoid nodules or plaques around an affected joint, even in the absence of RA. The dermatopathologist should be warned to search carefully for the subtle but distinctive histologic features of the disease that confirm the diagnosis. Treatment with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide with an overlying pressure wrap has minimal side effects and can work quickly with sustained benefits.

Intralymphatic histiocytosis was first described in 1994.1 To date, at least 70 cases have been reported in the English-language literature, the majority being associated with systemic or local inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), malignancy, and metal prostheses. The remaining cases arose independent of any detectable disease process.2 The clinical lesion localizes to areas around surgical scars or inflamed joints and generally presents with erythematous livedoid papules and plaques. Because of its rarity, pathologists and clinicians may be unfamiliar with this entity, leading to delayed or missed diagnoses.

Although the pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis remains unclear, it may be related to dysregulated immune signaling. The condition follows a chronic, relapsing-remitting course that has shown variable response to topical and systemic treatments. We present a rare case of intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with joint replacement/metal prosthesis3-14 that was responsive to a novel treatment with intralesional steroid injection and pressure bandage.

Case Report

An 89-year-old woman presented with a relapsing and remitting rash on the right calf and popliteal fossa of 11 months’ duration. It was becoming more painful over time and recently began to hurt when walking. Her medical history was remarkable for deep vein thromboses of the bilateral legs, Factor V Leiden deficiency, osteoarthritis, and a popliteal (Baker) cyst on the right leg that ruptured 22 months prior to presentation. Her surgical history included bilateral knee replacements (10 years and 2 years prior to the current presentation for the right and left knees, respectively). Her international normalized ratio (2.0) was therapeutic on warfarin.

Initially, swelling, pain, and redness developed in the right calf, and recurrent right-leg deep venous thrombosis was ruled out by Doppler ultrasound. The findings were considered to be secondary to inflammation from a popliteal cyst. Symptoms persisted despite application of warm compresses, leg elevation, and compression stockings. Treatment with doxycycline prescribed by the patient’s primary care physician 9 months prior for presumed cellulitis produced little improvement. Physical examination revealed a well-healed vertical scar on the right calf from an incisional biopsy within an 8-cm, tender, erythematous, indurated, sclerotic plaque with erythematous streaks radiating from the center of the plaque (Figure 1). There also was red-brown, indurated discoloration on the right shin.

Fine-needle aspiration of the lesion revealed red blood cells and histiocytes. Laboratory studies showed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 74 mm/h (reference range, 0–30 mm/h) and a C-reactive protein level of 39 mg/L (reference range, 0–10 mg/L). An incisional biopsy including the muscular fascia showed dense dermal fibrosis with chronic inflammation and scarring. A dermatopathologist (G. A. S.) reviewed the case and confirmed variable fibrosis and chronic inflammation associated with edema in the dermis and epidermal acanthosis. Inspection of vessels in the mid to upper dermis in one area revealed stellate, thin-walled, vascular structures that contained bland epithelioid cells lining the lumen as well as packed within the vessels. The epithelioid cells did not show atypia or mitotic figures, and they did not show intracytoplasmic vacuoles (Figure 2). Immunocytochemical staining for D2-40 was strongly positive in cells lining the vessels, consistent with lymphatics (Figure 3). CD68 immunohistochemistry for histiocytes stained the cells within the lymphatics (Figure 4). A diagnosis of intralymphatic histiocytosis was made.

Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/cc×1.6 cc was injected into the plaque once monthly for 2 consecutive months, and daily compression with a pressure bandage of the right lower leg was initiated. Four months after the first treatment with this regimen, the plaque was smaller and no longer sclerotic or painful, and the erythema was markedly reduced (Figure 5). Clinical and symptomatic improvement continued at 1-year follow-up.

Comment

Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare cutaneous disorder defined histologically by histiocytes within the lumina of lymphatics. In addition to the current case, our review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term intralymphatic histiocytosis yielded more than 70 total cases. The condition has a slight female predominance and typically is seen in individuals over the age of 60 years (age range, 16–89 years).12 Many cases are associated with RA/elevated rheumatoid factor.2,4,8,15-30 At least 9 cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis were associated with premalignant or malignant conditions (ie, adenocarcinoma of the breasts, lungs, and colon; Merkel cell carcinoma; melanoma; melanoma in situ; Mullerian carcinoma, gammopathy).4,15,31-34 Primary disease, defined as occurring in patients who are otherwise healthy, was noted in at least 10 cases.1,2,4,12,35,36 Finally, intralymphatic histiocytosis was identified in areas adjacent to metal implants and joint replacements or exploration in approximately 15 cases (including the current case).3-14,29,37

The condition presents with papules, plaques, and nodules in the setting of characteristic livedoid discoloration; however, some patients present with nonspecific nodules or plaques. Lesions may be symptomatic (eg, pruritic, tender) or asymptomatic. The histologic features of intralymphatic histiocytosis are distinctive but may be focal, as in our case, and the diagnosis is easily missed. The histologic differential diagnosis includes diseases in which intravascular accumulations of cells may be seen, including intravascular B-cell lymphoma, which can be excluded with stains that detect B cells (CD20/CD79a), and reactive angioendotheliomatosis, a benign proliferation of endothelial cells, which may be excluded with stains against endothelial markers (CD31/CD34). The course typically is chronic, and treatment with topical steroids,3,9,15,22,26 cyclophosphamide,15 local radiation,1 thalidomide,35 pentoxifylline,7 and RA medications (eg, prednisolone, methotrexate, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hydroxychloroquine) generally are ineffective.2,16,20,25 Symptoms may improve with joint replacement,4 excision of the involved lesion, treatment of an associated malignancy/infection,33,36,38,39 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, intra-articular steroid injection,18 amoxicillin and aspirin,19 infliximab,25 pressure bandage application,26 steroid-containing adhesive application,18 arthrocentesis,3,27 oral pentoxifylline,21 tacrolimus,29 CO2 laser,40 prednisolone,41 and tocilizumab.28 Treatment of associated RA is beneficial in rare cases.2,15,20,25,26

The pathogenesis of intralymphatic histiocytosis has not been elucidated with certainty but may represent an abnormal proliferative response of histiocytes and vessels in response to chronic systemic or local inflammation. Lymphangiectasis caused by lymphatic obstruction secondary to trauma, surgical manipulation, or chronic inflammation can promote lymphostasis and slowed clearance of antigens producing an accumulation of histiocytes and subsequent local immunologic reactions, thus an “immunocompromised district” is formed.42 It also is thought that rheumatic or prosthetic joints produce inflammatory mediator–rich (namely tumor necrosis factor α) synovial fluid that drains and collects within the dilated lymphatics, creating a nidus for histiocytes.1,5 In one case, treatment with an anti–tumor necrosis factor antibody (infliximab) improved the skin presentation and rheumatoid joint pain.25 Bakr et al2 noted an association with increased intralymphatic macrophage HLA-DR expression. This T-cell surface receptor typically is upregulated in cases of chronic antigen stimulation and autoimmune conditions.

Conclusion

Our patient had a history of a joint prosthesis and a popliteal cyst, which could have altered lymphatic drainage promoting abnormal immune cell trafficking contributing to the development of intralymphatic histiocytosis. The response to intralesional steroids supports this pathogenic hypothesis. Specifically, direct injection of the area suppressed the immune dysregulation, while compression lessened the degree of lymphostasis. In light of previously reported cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis in association with metal implants,3-9 we suggest that the condition should be considered in patients with chronic painful livedoid nodules or plaques around an affected joint, even in the absence of RA. The dermatopathologist should be warned to search carefully for the subtle but distinctive histologic features of the disease that confirm the diagnosis. Treatment with intralesional triamcinolone acetonide with an overlying pressure wrap has minimal side effects and can work quickly with sustained benefits.

- O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

- Bakr F, Webber N, Fassihi H, et al. Primary and secondary intralymphatic histiocytosis [published online January 17, 2014]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:927-933.

- Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants [published online November 10, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.

- Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

- Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

- Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants [published online March 6, 2011]. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

- de Unamuno Bustos B, García Rabasco A, Ballester Sánchez R, et al. Erythematous indurated plaque on the right upper limb. intralymphatic histiocytosis (IH) associated with orthopedic metal implant. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:547-549.

- Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

- Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

- Bidier M, Hamsch C, Kutzner H, et al. Two cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis following hip replacement [published online June 9, 2015]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:700-702.

- Darling MD, Akin R, Tarbox MB, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis overlying hip implantation treated with pentoxifilline. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2015;29(1 suppl):117-121.

- Demirkesen C, Kran T, Leblebici C, et al. Intravascular/intralymphatic histiocytosis: a report of 3 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:783-789.

- Gómez-Sánchez ME, Azaña-Defez JM, Martínez-Martínez ML, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: a report of 2 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:E1-E5.

- Haitz KA, Chapman MS, Seidel GD. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with an orthopedic metal implant. Cutis. 2016;97:E12-E14.

- Rieger E, Soyer HP, Leboit PE, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis or intravascular histiocytosis? an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study in two cases of intravascular histiocytic cell proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:497-504.

- Pruim B, Strutton G, Congdon S, et al. Cutaneous histiocytic lymphangitis: an unusual manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:101-105.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN. The spectrum of cutaneous lesions in rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical and pathological study of 43 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:1-10.

- Takiwaki H, Adachi A, Kohno H, et al. Intravascular or intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a report of 4 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:585-590.

- Mensing CH, Krengel S, Tronnier M, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis: is it “intravascular histiocytosis”? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:216-219.

- Okazaki A, Asada H, Niizeki H, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case with lymphatic endothelial proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1385-1387.

- Catalina-Fernández I, Alvárez AC, Martin FC, et al. Cutaneous intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:165-168.

- Nishie W, Sawamura D, Iitoyo M, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology. 2008;217:144-145.

- Okamoto N, Tanioka M, Yamamoto T, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:516-518.

- Huang H-Y, Liang C-W, Hu S-L, et al. Cutaneous intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E302-E303.

- Sakaguchi M, Nagai H, Tsuji G, et al. Effectiveness of infliximab for intralymphatic histiocytosis with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:131-133.

- Washio K, Nakata K, Nakamura A, et al. Pressure bandage as an effective treatment for intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology. 2011;223:20-24.

- Kaneko T, Takeuchi S, Nakano H, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with rheumatoid arthritis: possible association with the joint involvement. Case Reports Clin Med. 2014;3:149-152.

- Nakajima T, Kawabata D, Nakabo S, et al. Successful treatment with tocilizumab in a case of intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 2014;53:2255-2258.

- Tsujiwaki M, Hata H, Miyauchi T, et al. Warty intralymphatic histiocytosis successfully treated with topical tacrolimus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2267-2269.

- Tanaka M, Funasaka Y, Tsuruta K, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with massive interstitial granulomatous foci in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:237-238.

- Cornejo KM, Cosar EF, O’Donnell P. Cutaneous intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:568-570.

- Tran TAN, Tran Q, Carlson JA. Intralymphatic histiocytosis of the appendix and fallopian tube associated with primary peritoneal high-grade, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of Müllerian origin. Int J Surg Pathol. 2017;25:357-364.

- Echeverría-García B, Botella-Estrada R, Requena C, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis and cancer of the colon [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:257-262.

- Ergen EN, Zwerner JP. Cover image: intralymphatic histiocytosis with giant blanching violaceous plaques. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:325-326.

- Wang Y, Yang H, Tu P. Upper facial swelling: an uncommon manifestation of intralymphatic histiocytosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:814-815.

- Rhee D-Y, Lee D-W, Chang S-E, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis without rheumatoid arthritis. J Dermatol. 2008;35:691-693.

- Gilchrest BA, Eller MS, Geller AC, et al. The pathogenesis of melanoma induced by ultraviolet radiation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1341-1348.

- Asagoe K, Torigoe R, Ofuji R, et al. Reactive intravascular histiocytosis associated with tonsillitis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:560-563.

- Pouryazdanparast P, Yu L, Dalton VK, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis presenting with extensive vulvar necrosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;(36 suppl 1):1-7.

- Reznitsky M, Daugaard S, Charabi BW. Two rare cases of laryngeal intralymphatic histiocytosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:783-788.

- Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, Manabe T, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis comprises M2 macrophages in superficial dermal lymphatics with or without smooth muscles. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:898-902.

- Piccolo V, Ruocco E, Russo T, et al. A possible relationship between metal implant-induced intralymphatic histiocytosis and the concept of the immunocompromised district. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E365.

- O’Grady JT, Shahidullah H, Doherty VR, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis. Histopathology. 1994;24:265-268.

- Bakr F, Webber N, Fassihi H, et al. Primary and secondary intralymphatic histiocytosis [published online January 17, 2014]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:927-933.

- Watanabe T, Yamada N, Yoshida Y, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with granuloma formation associated with orthopaedic metal implants [published online November 10, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:402-404.

- Requena L, El-Shabrawi-Caelen L, Walsh SN, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis. a clinicopathologic study of 16 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:140-151.

- Grekin S, Mesfin M, Kang S, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis following placement of a metal implant. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:351-353.

- Rossari S, Scatena C, Gori A, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: cutaneous nodules and metal implants [published online March 6, 2011]. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:534-535.

- de Unamuno Bustos B, García Rabasco A, Ballester Sánchez R, et al. Erythematous indurated plaque on the right upper limb. intralymphatic histiocytosis (IH) associated with orthopedic metal implant. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:547-549.

- Chiu YE, Maloney JE, Bengana C. Erythematous patch overlying a swollen knee—quiz case. intralymphatic histiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1037-1042.

- Saggar S, Lee B, Krivo J, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with orthopedic implants. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:1208-1209.

- Bidier M, Hamsch C, Kutzner H, et al. Two cases of intralymphatic histiocytosis following hip replacement [published online June 9, 2015]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:700-702.

- Darling MD, Akin R, Tarbox MB, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis overlying hip implantation treated with pentoxifilline. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2015;29(1 suppl):117-121.

- Demirkesen C, Kran T, Leblebici C, et al. Intravascular/intralymphatic histiocytosis: a report of 3 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:783-789.

- Gómez-Sánchez ME, Azaña-Defez JM, Martínez-Martínez ML, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis: a report of 2 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:E1-E5.

- Haitz KA, Chapman MS, Seidel GD. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with an orthopedic metal implant. Cutis. 2016;97:E12-E14.

- Rieger E, Soyer HP, Leboit PE, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis or intravascular histiocytosis? an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study in two cases of intravascular histiocytic cell proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:497-504.

- Pruim B, Strutton G, Congdon S, et al. Cutaneous histiocytic lymphangitis: an unusual manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis. Australas J Dermatol. 2000;41:101-105.

- Magro CM, Crowson AN. The spectrum of cutaneous lesions in rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical and pathological study of 43 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:1-10.

- Takiwaki H, Adachi A, Kohno H, et al. Intravascular or intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a report of 4 cases.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:585-590.

- Mensing CH, Krengel S, Tronnier M, et al. Reactive angioendotheliomatosis: is it “intravascular histiocytosis”? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:216-219.

- Okazaki A, Asada H, Niizeki H, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case with lymphatic endothelial proliferation. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1385-1387.

- Catalina-Fernández I, Alvárez AC, Martin FC, et al. Cutaneous intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:165-168.

- Nishie W, Sawamura D, Iitoyo M, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology. 2008;217:144-145.

- Okamoto N, Tanioka M, Yamamoto T, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:516-518.

- Huang H-Y, Liang C-W, Hu S-L, et al. Cutaneous intravascular histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E302-E303.

- Sakaguchi M, Nagai H, Tsuji G, et al. Effectiveness of infliximab for intralymphatic histiocytosis with rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:131-133.

- Washio K, Nakata K, Nakamura A, et al. Pressure bandage as an effective treatment for intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatology. 2011;223:20-24.

- Kaneko T, Takeuchi S, Nakano H, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with rheumatoid arthritis: possible association with the joint involvement. Case Reports Clin Med. 2014;3:149-152.

- Nakajima T, Kawabata D, Nakabo S, et al. Successful treatment with tocilizumab in a case of intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 2014;53:2255-2258.

- Tsujiwaki M, Hata H, Miyauchi T, et al. Warty intralymphatic histiocytosis successfully treated with topical tacrolimus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2267-2269.

- Tanaka M, Funasaka Y, Tsuruta K, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis with massive interstitial granulomatous foci in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:237-238.

- Cornejo KM, Cosar EF, O’Donnell P. Cutaneous intralymphatic histiocytosis associated with lung adenocarcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:568-570.

- Tran TAN, Tran Q, Carlson JA. Intralymphatic histiocytosis of the appendix and fallopian tube associated with primary peritoneal high-grade, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of Müllerian origin. Int J Surg Pathol. 2017;25:357-364.

- Echeverría-García B, Botella-Estrada R, Requena C, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis and cancer of the colon [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:257-262.

- Ergen EN, Zwerner JP. Cover image: intralymphatic histiocytosis with giant blanching violaceous plaques. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:325-326.

- Wang Y, Yang H, Tu P. Upper facial swelling: an uncommon manifestation of intralymphatic histiocytosis. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:814-815.

- Rhee D-Y, Lee D-W, Chang S-E, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis without rheumatoid arthritis. J Dermatol. 2008;35:691-693.

- Gilchrest BA, Eller MS, Geller AC, et al. The pathogenesis of melanoma induced by ultraviolet radiation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1341-1348.

- Asagoe K, Torigoe R, Ofuji R, et al. Reactive intravascular histiocytosis associated with tonsillitis. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:560-563.

- Pouryazdanparast P, Yu L, Dalton VK, et al. Intravascular histiocytosis presenting with extensive vulvar necrosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;(36 suppl 1):1-7.

- Reznitsky M, Daugaard S, Charabi BW. Two rare cases of laryngeal intralymphatic histiocytosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273:783-788.

- Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, Manabe T, et al. Intralymphatic histiocytosis comprises M2 macrophages in superficial dermal lymphatics with or without smooth muscles. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:898-902.

- Piccolo V, Ruocco E, Russo T, et al. A possible relationship between metal implant-induced intralymphatic histiocytosis and the concept of the immunocompromised district. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:E365.

Practice Points

- Intralymphatic histiocytosis is a rare disorder often associated with rheumatic arthritis and joint prostheses.

- The diagnosis is made by histopathology as well as D2-40 and CD68 immunostaining.

- While there is no gold standard of treatment for intralymphatic histiocytosis, intralesional triamcinolone proved efficacious in this case with prolonged results.

Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome With Histopathologic Correlation

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with a concern of itching distributed along the V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve on the left frontoparietal scalp following a herpes zoster (HZ) outbreak in the same dermatome 2 months prior. She initially presented to the emergency department 2 months earlier with vesicular lesions distributed along the V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve, along with facial swelling, periorbital edema, inability to open the left eye, and “excruciating” pain. Her left eye was “itchy” but no ophthalmologic pathology was noted on examination. She was diagnosed with HZ and was treated with valacyclovir and prednisone. Oxycodone-acetaminophen followed by hydromorphone was prescribed for the severe pain with limited benefit. After completing treatment with valacyclovir, oral gabapentin was added for additional pain management, with an initial dose of 100 mg 3 times daily.

At the current presentation, the patient reported profound pruritus in the left frontoparietal scalp region that was intractable and debilitating. Some improvement of the itching was achieved with scratching that resulted in deep ulcerations of the scalp with moderate associated pain. In addition to the prior HZ outbreak, her medical history was remarkable for recurrent lymphoma, uterine cancer, chronic bronchitis, depression, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, and primary varicella-zoster virus infection in childhood. Her current medications included oral gabapentin (600 mg 3 times daily), diphenhydramine, levothyroxine, simvastatin, and topical ointments for itching.

On dermatologic evaluation, the patient rated her pain as a 5 on a 10-point scale of intensity. Alopecia involving the left frontoparietal scalp with a 2×3-cm ulceration in a geometric pattern with surrounding erythema was noted (Figure 1A). There also was hyperpigmentation on the forehead distributed along the V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve (Figure 1B). The patient also had been seen in the pain clinic where examination revealed sensory loss to both light touch and sharp stimulus along the left V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve. Visual fields were full, ocular movements were intact, and the face was symmetric with lower cranial nerves intact.

|

A diagnosis of trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) with chronic pain and pruritus due to a complex sensory neural disorder associated with HZ reactivation was made. Treatment included an increase in the dosage of oral gabapentin (1200 mg 3 times daily), oral oxycodone (5 mg every 4 to 6 hours as needed), and sphenopalatine ganglion block on the left side in an attempt to decrease pain and pruritus. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no improvement in symptoms.

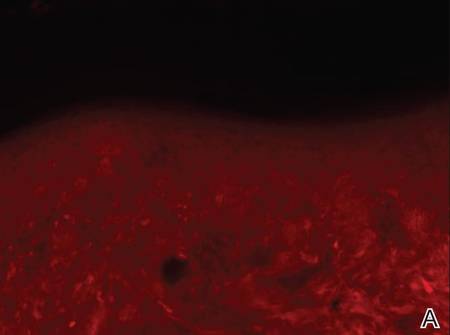

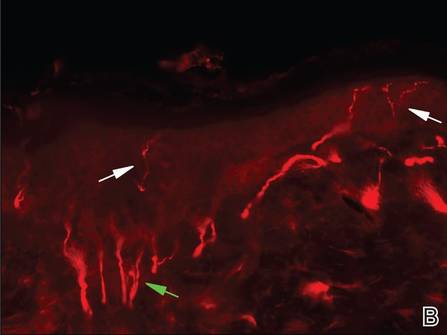

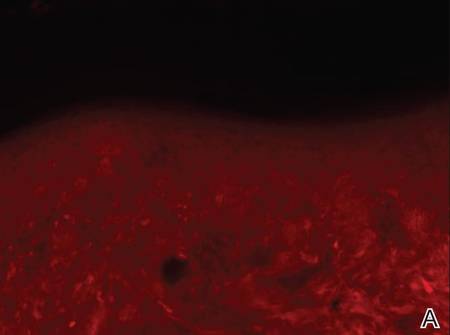

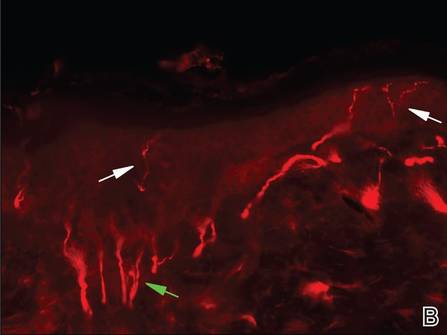

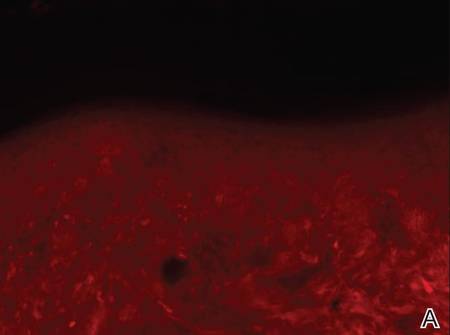

Three scalp punch biopsies were performed on presentation to the dermatology clinic including 2 from the affected area on the left frontoparietal scalp, and one from normal skin on the right side to assess the small nerve fibers affected. Protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5) immunostaining was performed to assess epidermal nerve fiber density. The left scalp biopsies were consistent with a complete focal sensory neuropathy affecting sensory and autonomic axons (Figure 2A). The right scalp biopsy revealed well-innervated skin (Figure 2B).

|

One year after the original HZ outbreak, the patient continued to have debilitating pruritus and pain in the affected dermatome. On physical examination at 1-year follow-up, the hyperpigmentation on the left side of the forehead showed minimal improvement. The ulcerations were healed, but excoriations were noted in the area. Having experienced some relief from titration of the dose of gabapentin 800 mg 3 times daily and doxepin 25 mg nightly at 1-year follow-up, the patient returned to work but remained highly distressed by her symptoms. Neurosurgery was consulted for possible balloon rhizotomy of the left trigeminal nerve, which she ultimately refused due to concerns about side effects.

Comment

Trophic trigeminal syndrome is characterized by unilateral ulceration of the face with anesthesia, paresthesia, and a crescent-shaped erosion or ulcer.1,2 It is one of 2 causes of self-induced facial ulcerations, the other being factitial dermatitis.1,3,4 A 2008 retrospective medical chart review and report of 14 cases helped elucidate the epidemiology of TTS.2 In this case series, the female to male ratio was 6 to 1, and the mean age of TTS onset was 45 years (age range, 6–82 years). The cause of disease in most patients was iatrogenic and the latent period to onset ranged from days to almost one decade. Most patients self-manipulated the face (n=9), and most ulcers affected the second trigeminal division. Pain intensity was severe in most (n=6), and gabapentin offered relief in only 2 cases.2

The etiologies of TTS are wide ranging, and the differential diagnosis should be contemplated when patients present with facial ulcers. Most cases are iatrogenic secondary to trigeminal rhizotomy,5 alcohol injections into the gasserian ganglion, or electrocoagulation. Also common are cases caused by ischemic damage to the trigeminal ganglion6 or Wallenberg syndrome.7 More rare etiologies include trauma,7 craniotomy,7 astrocytoma, acoustic neuroma, meningioma,8 idiopathic causes, basal cell carcinoma, infectious diseases (eg, tertiary syphilis, recurrent herpes simplex virus, leishmaniasis, cutaneous tuberculosis, leprosy, HZ),9-11 or systemic disease (eg, Wegener granulomatosis, Horton arteritis).

Trigeminal trophic syndrome is rare and there is little agreement on a treatment algorithm. As in our case, a methodical trial-and-error approach is suggested while encouraging the patient not to abandon treatment when efforts are not fruitful. The most important treatment strategy is behavioral modification; patients must become aware of the role of self-manipulation and assiduously avoid it. Using occlusive dressings at the affected site also may be helpful3,12 Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation may lead to improvement, but relapse is common with treatment discontinuation. Therapies directed at reducing paresthesia (eg, carbamazepine, diazepam, amitriptyline, chlorpromazine, pimozide) are sometimes successful, but relapse is common.1,3 Transplantation of in vitro–cultured epidermal cells is a new experimental treatment that offers hope for future success.13 Facial reconstruction of the affected area may help patients who can restrain themselves from self-manipulation.4

Skin biopsy findings in our case revealed an interesting aspect of the disease process of TTS. Skin biopsies are helpful in ruling out malignancy and specific stains can be used to further elucidate disease or pathologic processes occurring in the skin. In TTS, no specific changes are seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining, revealing only nonspecific inflammatory changes.1,5 Strikingly, the pathology of affected skin in patients with postherpetic neuralgia often reveals distal nociceptive axon loss,9 as was seen in the skin biopsies from our patient’s left scalp. It has been proven by many researchers in many neuropathic pain conditions that the pathological signature of chronic neuropathic pain is reduction in the density of cutaneous nociceptive innervation.9 The most common method for visualizing cutaneous neuritis is using an immunohistochemical labeling method in which antibodies are directed against PGP 9.5. A pan-axonal neurofilament marker, PGP 9.5 allows for visualization of small sensory nerve endings in the skin. As nociceptive axons degenerate in neuropathic pain conditions, it is believed that initiation of proalgesic changes within remaining peripheral nerves and the central nervous system (CNS) occur. Another interesting aspect of our case was the patient’s persistent intractable itching and chronic pain 2 months following the initial HZ outbreak. Although pain and itching can be evoked by similar stimuli and injuries, it has been shown that both have separate neuronal pathways because they produce different conscious and reflex motor actions.14 For instance, pain causes a withdrawal reflex, while itching causes mechanical stimulation of the affected area. The act of itching is thought to have evolved to protect against threats by the act of dislodging the stimulus rather than withdrawing as seen in pain.14 It has been hypothesized that postherpetic itching (chronic pruritus following an HZ outbreak) is due to spontaneous firing of denervated CNS itch neurons.9

Postherpetic neuralgia–related pain seems to be most closely correlated with degeneration of varicella-zoster virus–infected primary afferent neurons. With deceased afferent neurons sending signals to the CNS and death or dysfunction of inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord due to peripheral nerve injury, there is increased paradoxical electrical activity in specific CNS neurons. This CNS plasticity results in neuropathic pain and other altered sensory abnormalities in patients with TTS.9

Conclusion

We present a case of TTS distributed along the V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve on the left frontoparietal scalp following an HZ outbreak in a 49-year-old woman. Skin biopsies were consistent with this diagnosis, which revealed no neuronal innervation of the affected scalp despite intractable itching and chronic pain. Further research of TTS and postherpetic neuralgia is necessary to find appropriate treatment for patients with these conditions.

1. Kautz O, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Müller ML, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome with extensive ulceration following herpes zoster. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:61-63.

2. Garza I. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of face pain, dysaesthesias, anaesthesia and skin/soft tissue lesions. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:980-985.

3. Farahani RM, Marsee DK, Baden LR, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome with features of oral CMV disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:15-18.

4. Tollefson TT, Kriet JD, Wang TD, et al. Self-induced nasal ulceration. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6:162-166.

5. Monrad SU, Terrell JE, Aronoff DM. The trigeminal trophic syndrome: an unusual cause of nasal ulceration. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:949-952.

6. Elloumi-Jellouli A, Ben Ammar S, Fenniche S, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome: a report of two cases with review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:26.

7. Sadeghi P, Papay FA, Vidimos AT. Trigeminal trophic syndrome—report of four cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:807-812.

8. Luksi´c I, Luksi´c I, Sestan-Crnek S, et al. Trigeminal trophic syndrome of all three nerve branches: an underrecognized complication after brain surgery. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:170-173.

9. Oaklander AL. Mechanisms of pain and itch caused by herpes zoster (shingles). J Pain. 2008;9(1 suppl 1):S10-S18.

10. Gawande A. The itch. The New Yorker. June 2008:58-67.

11. Oaklander AL, Cohen SP, Raju SV. Intractable postherpetic itch and cutaneous deafferentation after facial shingles. Pain. 2002;96:9-12.

12. Preston PW, Orpin SD, Tucker WF, et al. Successful use of a thermoplastic dressing in two cases of the trigeminal trophic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:525-527.

13. Schwerdtner O, Damaskos T, Kage A, et al. Autologous epidermal cells can induce wound closure of neurotrophic ulceration caused by trigeminal trophic syndrome. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;34:443-445.

14. Oaklander AL, Siegel SM. Cutaneous innervation: form and function. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1027-1037.

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with a concern of itching distributed along the V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve on the left frontoparietal scalp following a herpes zoster (HZ) outbreak in the same dermatome 2 months prior. She initially presented to the emergency department 2 months earlier with vesicular lesions distributed along the V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve, along with facial swelling, periorbital edema, inability to open the left eye, and “excruciating” pain. Her left eye was “itchy” but no ophthalmologic pathology was noted on examination. She was diagnosed with HZ and was treated with valacyclovir and prednisone. Oxycodone-acetaminophen followed by hydromorphone was prescribed for the severe pain with limited benefit. After completing treatment with valacyclovir, oral gabapentin was added for additional pain management, with an initial dose of 100 mg 3 times daily.

At the current presentation, the patient reported profound pruritus in the left frontoparietal scalp region that was intractable and debilitating. Some improvement of the itching was achieved with scratching that resulted in deep ulcerations of the scalp with moderate associated pain. In addition to the prior HZ outbreak, her medical history was remarkable for recurrent lymphoma, uterine cancer, chronic bronchitis, depression, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, and primary varicella-zoster virus infection in childhood. Her current medications included oral gabapentin (600 mg 3 times daily), diphenhydramine, levothyroxine, simvastatin, and topical ointments for itching.

On dermatologic evaluation, the patient rated her pain as a 5 on a 10-point scale of intensity. Alopecia involving the left frontoparietal scalp with a 2×3-cm ulceration in a geometric pattern with surrounding erythema was noted (Figure 1A). There also was hyperpigmentation on the forehead distributed along the V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve (Figure 1B). The patient also had been seen in the pain clinic where examination revealed sensory loss to both light touch and sharp stimulus along the left V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve. Visual fields were full, ocular movements were intact, and the face was symmetric with lower cranial nerves intact.

|

A diagnosis of trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) with chronic pain and pruritus due to a complex sensory neural disorder associated with HZ reactivation was made. Treatment included an increase in the dosage of oral gabapentin (1200 mg 3 times daily), oral oxycodone (5 mg every 4 to 6 hours as needed), and sphenopalatine ganglion block on the left side in an attempt to decrease pain and pruritus. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no improvement in symptoms.

Three scalp punch biopsies were performed on presentation to the dermatology clinic including 2 from the affected area on the left frontoparietal scalp, and one from normal skin on the right side to assess the small nerve fibers affected. Protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5) immunostaining was performed to assess epidermal nerve fiber density. The left scalp biopsies were consistent with a complete focal sensory neuropathy affecting sensory and autonomic axons (Figure 2A). The right scalp biopsy revealed well-innervated skin (Figure 2B).

|

One year after the original HZ outbreak, the patient continued to have debilitating pruritus and pain in the affected dermatome. On physical examination at 1-year follow-up, the hyperpigmentation on the left side of the forehead showed minimal improvement. The ulcerations were healed, but excoriations were noted in the area. Having experienced some relief from titration of the dose of gabapentin 800 mg 3 times daily and doxepin 25 mg nightly at 1-year follow-up, the patient returned to work but remained highly distressed by her symptoms. Neurosurgery was consulted for possible balloon rhizotomy of the left trigeminal nerve, which she ultimately refused due to concerns about side effects.

Comment

Trophic trigeminal syndrome is characterized by unilateral ulceration of the face with anesthesia, paresthesia, and a crescent-shaped erosion or ulcer.1,2 It is one of 2 causes of self-induced facial ulcerations, the other being factitial dermatitis.1,3,4 A 2008 retrospective medical chart review and report of 14 cases helped elucidate the epidemiology of TTS.2 In this case series, the female to male ratio was 6 to 1, and the mean age of TTS onset was 45 years (age range, 6–82 years). The cause of disease in most patients was iatrogenic and the latent period to onset ranged from days to almost one decade. Most patients self-manipulated the face (n=9), and most ulcers affected the second trigeminal division. Pain intensity was severe in most (n=6), and gabapentin offered relief in only 2 cases.2

The etiologies of TTS are wide ranging, and the differential diagnosis should be contemplated when patients present with facial ulcers. Most cases are iatrogenic secondary to trigeminal rhizotomy,5 alcohol injections into the gasserian ganglion, or electrocoagulation. Also common are cases caused by ischemic damage to the trigeminal ganglion6 or Wallenberg syndrome.7 More rare etiologies include trauma,7 craniotomy,7 astrocytoma, acoustic neuroma, meningioma,8 idiopathic causes, basal cell carcinoma, infectious diseases (eg, tertiary syphilis, recurrent herpes simplex virus, leishmaniasis, cutaneous tuberculosis, leprosy, HZ),9-11 or systemic disease (eg, Wegener granulomatosis, Horton arteritis).

Trigeminal trophic syndrome is rare and there is little agreement on a treatment algorithm. As in our case, a methodical trial-and-error approach is suggested while encouraging the patient not to abandon treatment when efforts are not fruitful. The most important treatment strategy is behavioral modification; patients must become aware of the role of self-manipulation and assiduously avoid it. Using occlusive dressings at the affected site also may be helpful3,12 Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation may lead to improvement, but relapse is common with treatment discontinuation. Therapies directed at reducing paresthesia (eg, carbamazepine, diazepam, amitriptyline, chlorpromazine, pimozide) are sometimes successful, but relapse is common.1,3 Transplantation of in vitro–cultured epidermal cells is a new experimental treatment that offers hope for future success.13 Facial reconstruction of the affected area may help patients who can restrain themselves from self-manipulation.4

Skin biopsy findings in our case revealed an interesting aspect of the disease process of TTS. Skin biopsies are helpful in ruling out malignancy and specific stains can be used to further elucidate disease or pathologic processes occurring in the skin. In TTS, no specific changes are seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining, revealing only nonspecific inflammatory changes.1,5 Strikingly, the pathology of affected skin in patients with postherpetic neuralgia often reveals distal nociceptive axon loss,9 as was seen in the skin biopsies from our patient’s left scalp. It has been proven by many researchers in many neuropathic pain conditions that the pathological signature of chronic neuropathic pain is reduction in the density of cutaneous nociceptive innervation.9 The most common method for visualizing cutaneous neuritis is using an immunohistochemical labeling method in which antibodies are directed against PGP 9.5. A pan-axonal neurofilament marker, PGP 9.5 allows for visualization of small sensory nerve endings in the skin. As nociceptive axons degenerate in neuropathic pain conditions, it is believed that initiation of proalgesic changes within remaining peripheral nerves and the central nervous system (CNS) occur. Another interesting aspect of our case was the patient’s persistent intractable itching and chronic pain 2 months following the initial HZ outbreak. Although pain and itching can be evoked by similar stimuli and injuries, it has been shown that both have separate neuronal pathways because they produce different conscious and reflex motor actions.14 For instance, pain causes a withdrawal reflex, while itching causes mechanical stimulation of the affected area. The act of itching is thought to have evolved to protect against threats by the act of dislodging the stimulus rather than withdrawing as seen in pain.14 It has been hypothesized that postherpetic itching (chronic pruritus following an HZ outbreak) is due to spontaneous firing of denervated CNS itch neurons.9

Postherpetic neuralgia–related pain seems to be most closely correlated with degeneration of varicella-zoster virus–infected primary afferent neurons. With deceased afferent neurons sending signals to the CNS and death or dysfunction of inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord due to peripheral nerve injury, there is increased paradoxical electrical activity in specific CNS neurons. This CNS plasticity results in neuropathic pain and other altered sensory abnormalities in patients with TTS.9

Conclusion

We present a case of TTS distributed along the V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve on the left frontoparietal scalp following an HZ outbreak in a 49-year-old woman. Skin biopsies were consistent with this diagnosis, which revealed no neuronal innervation of the affected scalp despite intractable itching and chronic pain. Further research of TTS and postherpetic neuralgia is necessary to find appropriate treatment for patients with these conditions.

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with a concern of itching distributed along the V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve on the left frontoparietal scalp following a herpes zoster (HZ) outbreak in the same dermatome 2 months prior. She initially presented to the emergency department 2 months earlier with vesicular lesions distributed along the V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve, along with facial swelling, periorbital edema, inability to open the left eye, and “excruciating” pain. Her left eye was “itchy” but no ophthalmologic pathology was noted on examination. She was diagnosed with HZ and was treated with valacyclovir and prednisone. Oxycodone-acetaminophen followed by hydromorphone was prescribed for the severe pain with limited benefit. After completing treatment with valacyclovir, oral gabapentin was added for additional pain management, with an initial dose of 100 mg 3 times daily.

At the current presentation, the patient reported profound pruritus in the left frontoparietal scalp region that was intractable and debilitating. Some improvement of the itching was achieved with scratching that resulted in deep ulcerations of the scalp with moderate associated pain. In addition to the prior HZ outbreak, her medical history was remarkable for recurrent lymphoma, uterine cancer, chronic bronchitis, depression, hypothyroidism, osteoarthritis, and primary varicella-zoster virus infection in childhood. Her current medications included oral gabapentin (600 mg 3 times daily), diphenhydramine, levothyroxine, simvastatin, and topical ointments for itching.

On dermatologic evaluation, the patient rated her pain as a 5 on a 10-point scale of intensity. Alopecia involving the left frontoparietal scalp with a 2×3-cm ulceration in a geometric pattern with surrounding erythema was noted (Figure 1A). There also was hyperpigmentation on the forehead distributed along the V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve (Figure 1B). The patient also had been seen in the pain clinic where examination revealed sensory loss to both light touch and sharp stimulus along the left V1 branch of the trigeminal nerve. Visual fields were full, ocular movements were intact, and the face was symmetric with lower cranial nerves intact.

|

A diagnosis of trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) with chronic pain and pruritus due to a complex sensory neural disorder associated with HZ reactivation was made. Treatment included an increase in the dosage of oral gabapentin (1200 mg 3 times daily), oral oxycodone (5 mg every 4 to 6 hours as needed), and sphenopalatine ganglion block on the left side in an attempt to decrease pain and pruritus. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no improvement in symptoms.

Three scalp punch biopsies were performed on presentation to the dermatology clinic including 2 from the affected area on the left frontoparietal scalp, and one from normal skin on the right side to assess the small nerve fibers affected. Protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5) immunostaining was performed to assess epidermal nerve fiber density. The left scalp biopsies were consistent with a complete focal sensory neuropathy affecting sensory and autonomic axons (Figure 2A). The right scalp biopsy revealed well-innervated skin (Figure 2B).

|

One year after the original HZ outbreak, the patient continued to have debilitating pruritus and pain in the affected dermatome. On physical examination at 1-year follow-up, the hyperpigmentation on the left side of the forehead showed minimal improvement. The ulcerations were healed, but excoriations were noted in the area. Having experienced some relief from titration of the dose of gabapentin 800 mg 3 times daily and doxepin 25 mg nightly at 1-year follow-up, the patient returned to work but remained highly distressed by her symptoms. Neurosurgery was consulted for possible balloon rhizotomy of the left trigeminal nerve, which she ultimately refused due to concerns about side effects.

Comment

Trophic trigeminal syndrome is characterized by unilateral ulceration of the face with anesthesia, paresthesia, and a crescent-shaped erosion or ulcer.1,2 It is one of 2 causes of self-induced facial ulcerations, the other being factitial dermatitis.1,3,4 A 2008 retrospective medical chart review and report of 14 cases helped elucidate the epidemiology of TTS.2 In this case series, the female to male ratio was 6 to 1, and the mean age of TTS onset was 45 years (age range, 6–82 years). The cause of disease in most patients was iatrogenic and the latent period to onset ranged from days to almost one decade. Most patients self-manipulated the face (n=9), and most ulcers affected the second trigeminal division. Pain intensity was severe in most (n=6), and gabapentin offered relief in only 2 cases.2

The etiologies of TTS are wide ranging, and the differential diagnosis should be contemplated when patients present with facial ulcers. Most cases are iatrogenic secondary to trigeminal rhizotomy,5 alcohol injections into the gasserian ganglion, or electrocoagulation. Also common are cases caused by ischemic damage to the trigeminal ganglion6 or Wallenberg syndrome.7 More rare etiologies include trauma,7 craniotomy,7 astrocytoma, acoustic neuroma, meningioma,8 idiopathic causes, basal cell carcinoma, infectious diseases (eg, tertiary syphilis, recurrent herpes simplex virus, leishmaniasis, cutaneous tuberculosis, leprosy, HZ),9-11 or systemic disease (eg, Wegener granulomatosis, Horton arteritis).

Trigeminal trophic syndrome is rare and there is little agreement on a treatment algorithm. As in our case, a methodical trial-and-error approach is suggested while encouraging the patient not to abandon treatment when efforts are not fruitful. The most important treatment strategy is behavioral modification; patients must become aware of the role of self-manipulation and assiduously avoid it. Using occlusive dressings at the affected site also may be helpful3,12 Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation may lead to improvement, but relapse is common with treatment discontinuation. Therapies directed at reducing paresthesia (eg, carbamazepine, diazepam, amitriptyline, chlorpromazine, pimozide) are sometimes successful, but relapse is common.1,3 Transplantation of in vitro–cultured epidermal cells is a new experimental treatment that offers hope for future success.13 Facial reconstruction of the affected area may help patients who can restrain themselves from self-manipulation.4

Skin biopsy findings in our case revealed an interesting aspect of the disease process of TTS. Skin biopsies are helpful in ruling out malignancy and specific stains can be used to further elucidate disease or pathologic processes occurring in the skin. In TTS, no specific changes are seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining, revealing only nonspecific inflammatory changes.1,5 Strikingly, the pathology of affected skin in patients with postherpetic neuralgia often reveals distal nociceptive axon loss,9 as was seen in the skin biopsies from our patient’s left scalp. It has been proven by many researchers in many neuropathic pain conditions that the pathological signature of chronic neuropathic pain is reduction in the density of cutaneous nociceptive innervation.9 The most common method for visualizing cutaneous neuritis is using an immunohistochemical labeling method in which antibodies are directed against PGP 9.5. A pan-axonal neurofilament marker, PGP 9.5 allows for visualization of small sensory nerve endings in the skin. As nociceptive axons degenerate in neuropathic pain conditions, it is believed that initiation of proalgesic changes within remaining peripheral nerves and the central nervous system (CNS) occur. Another interesting aspect of our case was the patient’s persistent intractable itching and chronic pain 2 months following the initial HZ outbreak. Although pain and itching can be evoked by similar stimuli and injuries, it has been shown that both have separate neuronal pathways because they produce different conscious and reflex motor actions.14 For instance, pain causes a withdrawal reflex, while itching causes mechanical stimulation of the affected area. The act of itching is thought to have evolved to protect against threats by the act of dislodging the stimulus rather than withdrawing as seen in pain.14 It has been hypothesized that postherpetic itching (chronic pruritus following an HZ outbreak) is due to spontaneous firing of denervated CNS itch neurons.9