User login

Twice exceptionality: A hidden diagnosis in primary care

THE CASE

Michael T,* a 20-year-old cisgender male, visited one of our clinic’s primary care physicians (PCPs). He was reserved and quiet and spoke of his concerns about depression and social anxiety that had been present for several years. He also spoke of his inability to succeed at work and school. Following a thorough PCP review leading to diagnoses of major depressive disorder and social anxiety, the patient agreed to try medication. Over a period of 15 months, trials of medications including fluoxetine, sertraline, aripiprazole, and duloxetine did little to improve the patient’s mood. The PCP decided to consult with our clinic’s integrated health team.

The team reviewed several diagnostic possibilities (TABLE 1) and agreed with the PCP’s diagnoses of major depression and social anxiety. But these disorders alone did not explain the full picture. Team members noted the patient’s unusual communication style, characterized by remarkably long response times and slow processing speed. In particular, when discussing mood, he took several seconds to respond but would respond thoughtfully and with few words.

We administered the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV). Due to differences between the 4 indices within the WAIS-IV, the Full Scale Intelligence Quotient may under- or overestimate abilities across domains; this was the case for this patient. His General Ability Index (GAI) score was 130, in the very superior range and at the 98th percentile, placing him in the category of gifted intelligence. The patient’s processing speed, however, was at the 18th percentile, which explained his delayed response style and presence of developmental asynchrony, a concept occasionally reported when interpreting socio-emotional and educational maladjustment in gifted individuals.

We determined that Mr. T was twice exceptional—intellectually gifted and also having one or more areas of disability.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity .

In individuals with gifted intelligence, a discrepancy between cognitive and emotional development can make them vulnerable to behavioral and emotional challenges. It is not uncommon for gifted individuals to experience co-occurring distress, anxiety, depression, social withdrawal, difficulty coping with challenging tasks and experiences, low self-esteem, and excessive perfectionism.1-6 Giftedness accompanied by a delay in general abilities and processing speed (significant verbal-performance discrepancy) places an individual in the category of twice-exceptionality, or “2E”—having the potential for high achievement while displaying evidence of 1 or more disabilities including emotional or behavioral difficulties.7

2E Individuals: Prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes

Reported prevalence of twice-exceptionality varies, from approximately 180,000 to 360,000 students in the United States.7 In 2009, the National Commission on Twice Exceptional Students provided the following definition of twice exceptionality:7,8

“Twice-exceptional learners are students who demonstrate the potential for high achievement or creative productivity in one or more domains such as math, science, technology, the social arts, the visual, spatial, or performing arts or other areas of human productivity AND who manifest one or more disabilities as defined by federal or state eligibility criteria. These disabilities include specific learning disabilities; speech and language disorders; emotional/behavioral disorders; physical disabilities; Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD); or other health impairments, such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).”

How twice-exceptionality might manifest. The literature describes 3 unique groupings of 2E children: those who excel early due to strong language abilities, but later show signs of disability, often when curricular demands rise in junior high, high school, or even college; students diagnosed with disability, but who show exceptional gifts in some areas that may be masked by their learning difficulties; and highly intelligent students who seem to be average, because their disabilities mask their giftedness or their talents mask their difficulties.9,10

Unique behavioral and emotional challenges of 2E individuals may include lower motivation and academic self-efficacy, low self-worth and feelings of failure, or disruptive behaviors.7,11,12 Anxiety and depression often result from the functional impact of twice-exceptionality as well as resultant withdrawal, social isolation, and delay or hindrance of social skills (such as difficulty interpreting social cues).13,14 The individual in our case displayed many of these challenges, including lower motivation, self-worth, and self-esteem, and comorbid anxiety and depression (TABLE 1), further clouding diagnostic clarity.

Continue to: The need for improved recognition

The need for improved recognition. Twice-exceptionality commonly manifests as children reach grade-school age, but they are underrepresented in programs for the gifted due to misunderstanding and misdiagnosis by professionals.15,16 Best practices in identifying 2E children incorporate multidimensional assessments including pre-referral and screening, preliminary intervention, evaluation procedures, and educational planning.16 Despite research asserting that 2E individuals need more support services, knowing how to best identify and support individuals across various settings can prove difficult.7,17-19

Primary care, as we will discuss in a bit, is an interdisciplinary setting in which identification and comprehensive and collaborative support can occur. Historically, though, mental and physical health care have been “siloed” and mental health professionals’ functions in medical settings have often been circumscribed.20,21

A lesson from how our case unfolded

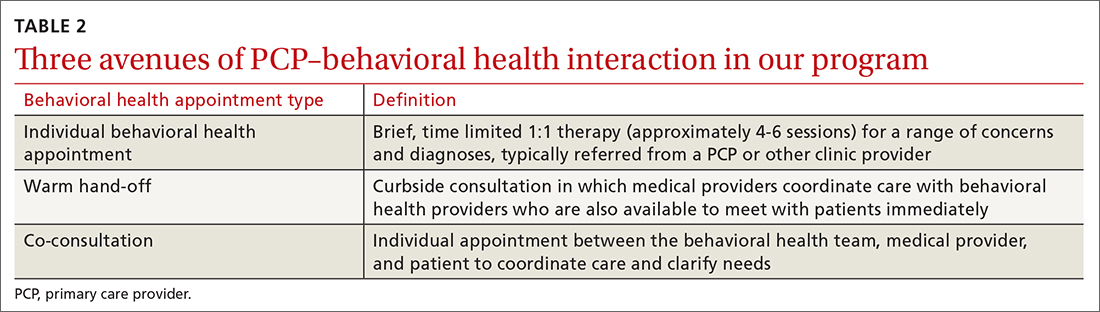

Our integrated health team, known as Integrated Behavioral Health Plus (IBH+), was developed at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and is a system-level integration of behavioral health professionals working with medical providers to improve outcomes and satisfaction.22 Psychology supervisors and trainees, telepsychiatrists and psychiatry residents, social workers, and pharmacists work together with PCPs and residents to deliver comprehensive patient care. Our model includes a range of behavioral health access points for patients (TABLE 2) and the use of complex patient databases and care team meetings.

In the case we have described here, the nature of the patient’s presentation did not trigger any of the clinical procedures described in TABLE 2, and he fell under the radar of complex patient cases in the clinic. Instead, informal, asynchronous clinical conversations between providers were what eventually lead to diagnostic clarification. Team consultation and psychometric testing provided by IBH+ helped uncover the “hidden diagnosis” of this patient in primary care and identified him as twice-exceptional, experiencing both giftedness and significant emotional suffering (major depression and social anxiety, low self-esteem and self-worth).

Takeaways for primary care

Not all PCPs, of course, have immediate onsite access to a program such as ours. However, innovative ways to tap into available resources might include establishing a partnership with 1 or more behavioral health professionals or bridging less formal relationships with such providers in the community and schools to more easily share patient records.

Continue to: Other presentations within 2E populations

Other presentations within 2E populations. 2E individuals may have other presentations coupled with high cognitive ability7: symptoms of hyperactivity disorders; specific learning disabilities; a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (previously termed Asperger type); attention, organizational, social, and behavioral issues; and impulsivity or emotional volatility.

Of note, the perspective of our care team shifted from a “bugs and drugs” perspective of diagnosis and treatment—biological explanations and pharmaceutical solutions—to an approach that explored the underlying interplay between cognitive and emotional functioning for this individual. Our treatment focused on a strengths-based and patient-centered approach. Even without the resources of a full IBH+ model, primary care practices may be able to adapt our experience to their ever-growing complex populations.

Our team shifted treatment planning to the needs of the patient. The 2E identification changed the patient’s perspective about himself. After learning of his giftedness, the patient was able to reframe himself as a highly intelligent, capable individual in need of treatment for depression and social anxiety, as opposed to questioning his intelligence and experiencing confusion and hopelessness within the medical system. His PCP collaborated with the team via telecommunication to maintain an efficacious antidepressant plan and to use a strengths-based approach focused on increasing the patient’s self-view and changing the illness narrative. This narrative was changed by practicing skills, such as challenging unhelpful thought patterns, setting beneficial boundaries, and supporting assertive communication to oppose thoughts and relationships that perpetuated old, negative beliefs and assumptions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn S. Saldaña, PhD, University of Colorado, 12631 East 17th Avenue, AO1 L15, 3rd Floor, Aurora, CO 80045; kathryn. saldana@ucdenver.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to A.F. Williams Family Medicine Clinic and the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus School of Medicine for their unparalleled models of resident training and multidisciplinary care.

1. Guénolé F, Louis J, Creveuil C, et al. Behavioral profiles of clinically referred children with intellectual giftedness. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:540153.

2. Alesi M, Rappo G, Pepi A. Emotional profile and intellectual functioning: A comparison among children with borderline intellectual functioning, average intellectual functioning, and gifted intellectual functioning. SAGE Open. 2015;5:2158244015589995.

3. Alsop G. Asynchrony: intuitively valid and theoretically reliable. Roeper Rev. 2003;25:118-127.

4. Guignard J-H, Jacquet A-Y, Lubart TI. Perfectionism and anxiety: a paradox in intellectual giftedness? PloS One. 2012;7:e41043.

5. Reis SM, McCoach DB. The underachievement of gifted students: What do we know and where do we go? Gifted Child Quarterly. 2000;44:152-170.

6. Barchmann H, Kinze W. Behaviour and achievement disorders in children with high intelligence. Acta Paedopsychiatr. 1990;53:168-172.

7. Reis SM, Baum SM, Burke E. An operational definition of twice-exceptional learners: implications and applications. Gifted Child Quarterly. 2014;58:217-230.

8. NAGC Position Statements & White Papers. Accessed September 18, 2021. http://www.nagc.org/index.aspx?id=5094

9. Neihart M. Identifying and providing services to twice exceptional children. In: Handbook of Giftedness in Children. Pfeiffer SI, ed. Springer; 2008:115-137.

10. Baum SM, Owen SV. To Be Gifted & Learning Disabled: Strategies for Helping Bright Students with Learning & Attention Difficulties. Prufrock Press Inc; 2004.

11. Reis SM. Talents in two places: case studies of high ability students with learning disabilities who have achieved. [Research Monograph 95114]. 1995.

12. Schiff MM, Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Scatter analysis of WISC-R profiles for learning disabled children with superior intelligence. J Learn Disabil. 1981;14:400-404.

13. King EW. Addressing the social and emotional needs of twice-exceptional students. Teaching Exceptional Child. 2005;38:16-21.

14. Stormont M, Stebbins MS, Holliday G. Characteristics and educational support needs of underrepresented gifted adolescents. Psychol Schools. 2001;38:413-423.

15. Morrison WF, Rizza MG. Creating a toolkit for identifying twice-exceptional students. J Educ Gifted. 2007;31:57-76.

16. Rizza MG, Morrison WF. Identifying twice exceptional children: a toolkit for success. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ967126.pdf

17. Cohen SS, Vaughn S. Gifted students with learning disabilities: what does the research say? Learn Disabil. 1994;5:87-94.

18. National Center for Education Statistics. Students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp

19. The Hechinger Report. Twice exceptional, doubly disadvantaged? How schools struggle to serve gifted students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://hechingerreport.org/twice-exceptional-doubly-disadvantaged-how-schools-struggle-to-serve-gifted-students-with-disabilities

20. Mendaglio S. Heightened multifaceted sensitivity of gifted students: implications for counseling. J Secondary Gifted Educ. 2002;14:72-82.

21. Pereles DA, Omdal S, Baldwin L. Response to intervention and twice-exceptional learners: a promising fit. Gifted Child Today. 2009;32:40-51.

22. Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: evidence update 2010-2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. 2016. Accessed September 18, 2021. www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolving-Models-of-BHI.pdf

THE CASE

Michael T,* a 20-year-old cisgender male, visited one of our clinic’s primary care physicians (PCPs). He was reserved and quiet and spoke of his concerns about depression and social anxiety that had been present for several years. He also spoke of his inability to succeed at work and school. Following a thorough PCP review leading to diagnoses of major depressive disorder and social anxiety, the patient agreed to try medication. Over a period of 15 months, trials of medications including fluoxetine, sertraline, aripiprazole, and duloxetine did little to improve the patient’s mood. The PCP decided to consult with our clinic’s integrated health team.

The team reviewed several diagnostic possibilities (TABLE 1) and agreed with the PCP’s diagnoses of major depression and social anxiety. But these disorders alone did not explain the full picture. Team members noted the patient’s unusual communication style, characterized by remarkably long response times and slow processing speed. In particular, when discussing mood, he took several seconds to respond but would respond thoughtfully and with few words.

We administered the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV). Due to differences between the 4 indices within the WAIS-IV, the Full Scale Intelligence Quotient may under- or overestimate abilities across domains; this was the case for this patient. His General Ability Index (GAI) score was 130, in the very superior range and at the 98th percentile, placing him in the category of gifted intelligence. The patient’s processing speed, however, was at the 18th percentile, which explained his delayed response style and presence of developmental asynchrony, a concept occasionally reported when interpreting socio-emotional and educational maladjustment in gifted individuals.

We determined that Mr. T was twice exceptional—intellectually gifted and also having one or more areas of disability.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity .

In individuals with gifted intelligence, a discrepancy between cognitive and emotional development can make them vulnerable to behavioral and emotional challenges. It is not uncommon for gifted individuals to experience co-occurring distress, anxiety, depression, social withdrawal, difficulty coping with challenging tasks and experiences, low self-esteem, and excessive perfectionism.1-6 Giftedness accompanied by a delay in general abilities and processing speed (significant verbal-performance discrepancy) places an individual in the category of twice-exceptionality, or “2E”—having the potential for high achievement while displaying evidence of 1 or more disabilities including emotional or behavioral difficulties.7

2E Individuals: Prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes

Reported prevalence of twice-exceptionality varies, from approximately 180,000 to 360,000 students in the United States.7 In 2009, the National Commission on Twice Exceptional Students provided the following definition of twice exceptionality:7,8

“Twice-exceptional learners are students who demonstrate the potential for high achievement or creative productivity in one or more domains such as math, science, technology, the social arts, the visual, spatial, or performing arts or other areas of human productivity AND who manifest one or more disabilities as defined by federal or state eligibility criteria. These disabilities include specific learning disabilities; speech and language disorders; emotional/behavioral disorders; physical disabilities; Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD); or other health impairments, such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).”

How twice-exceptionality might manifest. The literature describes 3 unique groupings of 2E children: those who excel early due to strong language abilities, but later show signs of disability, often when curricular demands rise in junior high, high school, or even college; students diagnosed with disability, but who show exceptional gifts in some areas that may be masked by their learning difficulties; and highly intelligent students who seem to be average, because their disabilities mask their giftedness or their talents mask their difficulties.9,10

Unique behavioral and emotional challenges of 2E individuals may include lower motivation and academic self-efficacy, low self-worth and feelings of failure, or disruptive behaviors.7,11,12 Anxiety and depression often result from the functional impact of twice-exceptionality as well as resultant withdrawal, social isolation, and delay or hindrance of social skills (such as difficulty interpreting social cues).13,14 The individual in our case displayed many of these challenges, including lower motivation, self-worth, and self-esteem, and comorbid anxiety and depression (TABLE 1), further clouding diagnostic clarity.

Continue to: The need for improved recognition

The need for improved recognition. Twice-exceptionality commonly manifests as children reach grade-school age, but they are underrepresented in programs for the gifted due to misunderstanding and misdiagnosis by professionals.15,16 Best practices in identifying 2E children incorporate multidimensional assessments including pre-referral and screening, preliminary intervention, evaluation procedures, and educational planning.16 Despite research asserting that 2E individuals need more support services, knowing how to best identify and support individuals across various settings can prove difficult.7,17-19

Primary care, as we will discuss in a bit, is an interdisciplinary setting in which identification and comprehensive and collaborative support can occur. Historically, though, mental and physical health care have been “siloed” and mental health professionals’ functions in medical settings have often been circumscribed.20,21

A lesson from how our case unfolded

Our integrated health team, known as Integrated Behavioral Health Plus (IBH+), was developed at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and is a system-level integration of behavioral health professionals working with medical providers to improve outcomes and satisfaction.22 Psychology supervisors and trainees, telepsychiatrists and psychiatry residents, social workers, and pharmacists work together with PCPs and residents to deliver comprehensive patient care. Our model includes a range of behavioral health access points for patients (TABLE 2) and the use of complex patient databases and care team meetings.

In the case we have described here, the nature of the patient’s presentation did not trigger any of the clinical procedures described in TABLE 2, and he fell under the radar of complex patient cases in the clinic. Instead, informal, asynchronous clinical conversations between providers were what eventually lead to diagnostic clarification. Team consultation and psychometric testing provided by IBH+ helped uncover the “hidden diagnosis” of this patient in primary care and identified him as twice-exceptional, experiencing both giftedness and significant emotional suffering (major depression and social anxiety, low self-esteem and self-worth).

Takeaways for primary care

Not all PCPs, of course, have immediate onsite access to a program such as ours. However, innovative ways to tap into available resources might include establishing a partnership with 1 or more behavioral health professionals or bridging less formal relationships with such providers in the community and schools to more easily share patient records.

Continue to: Other presentations within 2E populations

Other presentations within 2E populations. 2E individuals may have other presentations coupled with high cognitive ability7: symptoms of hyperactivity disorders; specific learning disabilities; a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (previously termed Asperger type); attention, organizational, social, and behavioral issues; and impulsivity or emotional volatility.

Of note, the perspective of our care team shifted from a “bugs and drugs” perspective of diagnosis and treatment—biological explanations and pharmaceutical solutions—to an approach that explored the underlying interplay between cognitive and emotional functioning for this individual. Our treatment focused on a strengths-based and patient-centered approach. Even without the resources of a full IBH+ model, primary care practices may be able to adapt our experience to their ever-growing complex populations.

Our team shifted treatment planning to the needs of the patient. The 2E identification changed the patient’s perspective about himself. After learning of his giftedness, the patient was able to reframe himself as a highly intelligent, capable individual in need of treatment for depression and social anxiety, as opposed to questioning his intelligence and experiencing confusion and hopelessness within the medical system. His PCP collaborated with the team via telecommunication to maintain an efficacious antidepressant plan and to use a strengths-based approach focused on increasing the patient’s self-view and changing the illness narrative. This narrative was changed by practicing skills, such as challenging unhelpful thought patterns, setting beneficial boundaries, and supporting assertive communication to oppose thoughts and relationships that perpetuated old, negative beliefs and assumptions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn S. Saldaña, PhD, University of Colorado, 12631 East 17th Avenue, AO1 L15, 3rd Floor, Aurora, CO 80045; kathryn. saldana@ucdenver.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to A.F. Williams Family Medicine Clinic and the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus School of Medicine for their unparalleled models of resident training and multidisciplinary care.

THE CASE

Michael T,* a 20-year-old cisgender male, visited one of our clinic’s primary care physicians (PCPs). He was reserved and quiet and spoke of his concerns about depression and social anxiety that had been present for several years. He also spoke of his inability to succeed at work and school. Following a thorough PCP review leading to diagnoses of major depressive disorder and social anxiety, the patient agreed to try medication. Over a period of 15 months, trials of medications including fluoxetine, sertraline, aripiprazole, and duloxetine did little to improve the patient’s mood. The PCP decided to consult with our clinic’s integrated health team.

The team reviewed several diagnostic possibilities (TABLE 1) and agreed with the PCP’s diagnoses of major depression and social anxiety. But these disorders alone did not explain the full picture. Team members noted the patient’s unusual communication style, characterized by remarkably long response times and slow processing speed. In particular, when discussing mood, he took several seconds to respond but would respond thoughtfully and with few words.

We administered the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV). Due to differences between the 4 indices within the WAIS-IV, the Full Scale Intelligence Quotient may under- or overestimate abilities across domains; this was the case for this patient. His General Ability Index (GAI) score was 130, in the very superior range and at the 98th percentile, placing him in the category of gifted intelligence. The patient’s processing speed, however, was at the 18th percentile, which explained his delayed response style and presence of developmental asynchrony, a concept occasionally reported when interpreting socio-emotional and educational maladjustment in gifted individuals.

We determined that Mr. T was twice exceptional—intellectually gifted and also having one or more areas of disability.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity .

In individuals with gifted intelligence, a discrepancy between cognitive and emotional development can make them vulnerable to behavioral and emotional challenges. It is not uncommon for gifted individuals to experience co-occurring distress, anxiety, depression, social withdrawal, difficulty coping with challenging tasks and experiences, low self-esteem, and excessive perfectionism.1-6 Giftedness accompanied by a delay in general abilities and processing speed (significant verbal-performance discrepancy) places an individual in the category of twice-exceptionality, or “2E”—having the potential for high achievement while displaying evidence of 1 or more disabilities including emotional or behavioral difficulties.7

2E Individuals: Prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes

Reported prevalence of twice-exceptionality varies, from approximately 180,000 to 360,000 students in the United States.7 In 2009, the National Commission on Twice Exceptional Students provided the following definition of twice exceptionality:7,8

“Twice-exceptional learners are students who demonstrate the potential for high achievement or creative productivity in one or more domains such as math, science, technology, the social arts, the visual, spatial, or performing arts or other areas of human productivity AND who manifest one or more disabilities as defined by federal or state eligibility criteria. These disabilities include specific learning disabilities; speech and language disorders; emotional/behavioral disorders; physical disabilities; Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD); or other health impairments, such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).”

How twice-exceptionality might manifest. The literature describes 3 unique groupings of 2E children: those who excel early due to strong language abilities, but later show signs of disability, often when curricular demands rise in junior high, high school, or even college; students diagnosed with disability, but who show exceptional gifts in some areas that may be masked by their learning difficulties; and highly intelligent students who seem to be average, because their disabilities mask their giftedness or their talents mask their difficulties.9,10

Unique behavioral and emotional challenges of 2E individuals may include lower motivation and academic self-efficacy, low self-worth and feelings of failure, or disruptive behaviors.7,11,12 Anxiety and depression often result from the functional impact of twice-exceptionality as well as resultant withdrawal, social isolation, and delay or hindrance of social skills (such as difficulty interpreting social cues).13,14 The individual in our case displayed many of these challenges, including lower motivation, self-worth, and self-esteem, and comorbid anxiety and depression (TABLE 1), further clouding diagnostic clarity.

Continue to: The need for improved recognition

The need for improved recognition. Twice-exceptionality commonly manifests as children reach grade-school age, but they are underrepresented in programs for the gifted due to misunderstanding and misdiagnosis by professionals.15,16 Best practices in identifying 2E children incorporate multidimensional assessments including pre-referral and screening, preliminary intervention, evaluation procedures, and educational planning.16 Despite research asserting that 2E individuals need more support services, knowing how to best identify and support individuals across various settings can prove difficult.7,17-19

Primary care, as we will discuss in a bit, is an interdisciplinary setting in which identification and comprehensive and collaborative support can occur. Historically, though, mental and physical health care have been “siloed” and mental health professionals’ functions in medical settings have often been circumscribed.20,21

A lesson from how our case unfolded

Our integrated health team, known as Integrated Behavioral Health Plus (IBH+), was developed at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and is a system-level integration of behavioral health professionals working with medical providers to improve outcomes and satisfaction.22 Psychology supervisors and trainees, telepsychiatrists and psychiatry residents, social workers, and pharmacists work together with PCPs and residents to deliver comprehensive patient care. Our model includes a range of behavioral health access points for patients (TABLE 2) and the use of complex patient databases and care team meetings.

In the case we have described here, the nature of the patient’s presentation did not trigger any of the clinical procedures described in TABLE 2, and he fell under the radar of complex patient cases in the clinic. Instead, informal, asynchronous clinical conversations between providers were what eventually lead to diagnostic clarification. Team consultation and psychometric testing provided by IBH+ helped uncover the “hidden diagnosis” of this patient in primary care and identified him as twice-exceptional, experiencing both giftedness and significant emotional suffering (major depression and social anxiety, low self-esteem and self-worth).

Takeaways for primary care

Not all PCPs, of course, have immediate onsite access to a program such as ours. However, innovative ways to tap into available resources might include establishing a partnership with 1 or more behavioral health professionals or bridging less formal relationships with such providers in the community and schools to more easily share patient records.

Continue to: Other presentations within 2E populations

Other presentations within 2E populations. 2E individuals may have other presentations coupled with high cognitive ability7: symptoms of hyperactivity disorders; specific learning disabilities; a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (previously termed Asperger type); attention, organizational, social, and behavioral issues; and impulsivity or emotional volatility.

Of note, the perspective of our care team shifted from a “bugs and drugs” perspective of diagnosis and treatment—biological explanations and pharmaceutical solutions—to an approach that explored the underlying interplay between cognitive and emotional functioning for this individual. Our treatment focused on a strengths-based and patient-centered approach. Even without the resources of a full IBH+ model, primary care practices may be able to adapt our experience to their ever-growing complex populations.

Our team shifted treatment planning to the needs of the patient. The 2E identification changed the patient’s perspective about himself. After learning of his giftedness, the patient was able to reframe himself as a highly intelligent, capable individual in need of treatment for depression and social anxiety, as opposed to questioning his intelligence and experiencing confusion and hopelessness within the medical system. His PCP collaborated with the team via telecommunication to maintain an efficacious antidepressant plan and to use a strengths-based approach focused on increasing the patient’s self-view and changing the illness narrative. This narrative was changed by practicing skills, such as challenging unhelpful thought patterns, setting beneficial boundaries, and supporting assertive communication to oppose thoughts and relationships that perpetuated old, negative beliefs and assumptions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn S. Saldaña, PhD, University of Colorado, 12631 East 17th Avenue, AO1 L15, 3rd Floor, Aurora, CO 80045; kathryn. saldana@ucdenver.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to A.F. Williams Family Medicine Clinic and the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus School of Medicine for their unparalleled models of resident training and multidisciplinary care.

1. Guénolé F, Louis J, Creveuil C, et al. Behavioral profiles of clinically referred children with intellectual giftedness. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:540153.

2. Alesi M, Rappo G, Pepi A. Emotional profile and intellectual functioning: A comparison among children with borderline intellectual functioning, average intellectual functioning, and gifted intellectual functioning. SAGE Open. 2015;5:2158244015589995.

3. Alsop G. Asynchrony: intuitively valid and theoretically reliable. Roeper Rev. 2003;25:118-127.

4. Guignard J-H, Jacquet A-Y, Lubart TI. Perfectionism and anxiety: a paradox in intellectual giftedness? PloS One. 2012;7:e41043.

5. Reis SM, McCoach DB. The underachievement of gifted students: What do we know and where do we go? Gifted Child Quarterly. 2000;44:152-170.

6. Barchmann H, Kinze W. Behaviour and achievement disorders in children with high intelligence. Acta Paedopsychiatr. 1990;53:168-172.

7. Reis SM, Baum SM, Burke E. An operational definition of twice-exceptional learners: implications and applications. Gifted Child Quarterly. 2014;58:217-230.

8. NAGC Position Statements & White Papers. Accessed September 18, 2021. http://www.nagc.org/index.aspx?id=5094

9. Neihart M. Identifying and providing services to twice exceptional children. In: Handbook of Giftedness in Children. Pfeiffer SI, ed. Springer; 2008:115-137.

10. Baum SM, Owen SV. To Be Gifted & Learning Disabled: Strategies for Helping Bright Students with Learning & Attention Difficulties. Prufrock Press Inc; 2004.

11. Reis SM. Talents in two places: case studies of high ability students with learning disabilities who have achieved. [Research Monograph 95114]. 1995.

12. Schiff MM, Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Scatter analysis of WISC-R profiles for learning disabled children with superior intelligence. J Learn Disabil. 1981;14:400-404.

13. King EW. Addressing the social and emotional needs of twice-exceptional students. Teaching Exceptional Child. 2005;38:16-21.

14. Stormont M, Stebbins MS, Holliday G. Characteristics and educational support needs of underrepresented gifted adolescents. Psychol Schools. 2001;38:413-423.

15. Morrison WF, Rizza MG. Creating a toolkit for identifying twice-exceptional students. J Educ Gifted. 2007;31:57-76.

16. Rizza MG, Morrison WF. Identifying twice exceptional children: a toolkit for success. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ967126.pdf

17. Cohen SS, Vaughn S. Gifted students with learning disabilities: what does the research say? Learn Disabil. 1994;5:87-94.

18. National Center for Education Statistics. Students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp

19. The Hechinger Report. Twice exceptional, doubly disadvantaged? How schools struggle to serve gifted students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://hechingerreport.org/twice-exceptional-doubly-disadvantaged-how-schools-struggle-to-serve-gifted-students-with-disabilities

20. Mendaglio S. Heightened multifaceted sensitivity of gifted students: implications for counseling. J Secondary Gifted Educ. 2002;14:72-82.

21. Pereles DA, Omdal S, Baldwin L. Response to intervention and twice-exceptional learners: a promising fit. Gifted Child Today. 2009;32:40-51.

22. Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: evidence update 2010-2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. 2016. Accessed September 18, 2021. www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolving-Models-of-BHI.pdf

1. Guénolé F, Louis J, Creveuil C, et al. Behavioral profiles of clinically referred children with intellectual giftedness. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:540153.

2. Alesi M, Rappo G, Pepi A. Emotional profile and intellectual functioning: A comparison among children with borderline intellectual functioning, average intellectual functioning, and gifted intellectual functioning. SAGE Open. 2015;5:2158244015589995.

3. Alsop G. Asynchrony: intuitively valid and theoretically reliable. Roeper Rev. 2003;25:118-127.

4. Guignard J-H, Jacquet A-Y, Lubart TI. Perfectionism and anxiety: a paradox in intellectual giftedness? PloS One. 2012;7:e41043.

5. Reis SM, McCoach DB. The underachievement of gifted students: What do we know and where do we go? Gifted Child Quarterly. 2000;44:152-170.

6. Barchmann H, Kinze W. Behaviour and achievement disorders in children with high intelligence. Acta Paedopsychiatr. 1990;53:168-172.

7. Reis SM, Baum SM, Burke E. An operational definition of twice-exceptional learners: implications and applications. Gifted Child Quarterly. 2014;58:217-230.

8. NAGC Position Statements & White Papers. Accessed September 18, 2021. http://www.nagc.org/index.aspx?id=5094

9. Neihart M. Identifying and providing services to twice exceptional children. In: Handbook of Giftedness in Children. Pfeiffer SI, ed. Springer; 2008:115-137.

10. Baum SM, Owen SV. To Be Gifted & Learning Disabled: Strategies for Helping Bright Students with Learning & Attention Difficulties. Prufrock Press Inc; 2004.

11. Reis SM. Talents in two places: case studies of high ability students with learning disabilities who have achieved. [Research Monograph 95114]. 1995.

12. Schiff MM, Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Scatter analysis of WISC-R profiles for learning disabled children with superior intelligence. J Learn Disabil. 1981;14:400-404.

13. King EW. Addressing the social and emotional needs of twice-exceptional students. Teaching Exceptional Child. 2005;38:16-21.

14. Stormont M, Stebbins MS, Holliday G. Characteristics and educational support needs of underrepresented gifted adolescents. Psychol Schools. 2001;38:413-423.

15. Morrison WF, Rizza MG. Creating a toolkit for identifying twice-exceptional students. J Educ Gifted. 2007;31:57-76.

16. Rizza MG, Morrison WF. Identifying twice exceptional children: a toolkit for success. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ967126.pdf

17. Cohen SS, Vaughn S. Gifted students with learning disabilities: what does the research say? Learn Disabil. 1994;5:87-94.

18. National Center for Education Statistics. Students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp

19. The Hechinger Report. Twice exceptional, doubly disadvantaged? How schools struggle to serve gifted students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://hechingerreport.org/twice-exceptional-doubly-disadvantaged-how-schools-struggle-to-serve-gifted-students-with-disabilities

20. Mendaglio S. Heightened multifaceted sensitivity of gifted students: implications for counseling. J Secondary Gifted Educ. 2002;14:72-82.

21. Pereles DA, Omdal S, Baldwin L. Response to intervention and twice-exceptional learners: a promising fit. Gifted Child Today. 2009;32:40-51.

22. Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: evidence update 2010-2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. 2016. Accessed September 18, 2021. www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolving-Models-of-BHI.pdf