User login

Twice exceptionality: A hidden diagnosis in primary care

THE CASE

Michael T,* a 20-year-old cisgender male, visited one of our clinic’s primary care physicians (PCPs). He was reserved and quiet and spoke of his concerns about depression and social anxiety that had been present for several years. He also spoke of his inability to succeed at work and school. Following a thorough PCP review leading to diagnoses of major depressive disorder and social anxiety, the patient agreed to try medication. Over a period of 15 months, trials of medications including fluoxetine, sertraline, aripiprazole, and duloxetine did little to improve the patient’s mood. The PCP decided to consult with our clinic’s integrated health team.

The team reviewed several diagnostic possibilities (TABLE 1) and agreed with the PCP’s diagnoses of major depression and social anxiety. But these disorders alone did not explain the full picture. Team members noted the patient’s unusual communication style, characterized by remarkably long response times and slow processing speed. In particular, when discussing mood, he took several seconds to respond but would respond thoughtfully and with few words.

We administered the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV). Due to differences between the 4 indices within the WAIS-IV, the Full Scale Intelligence Quotient may under- or overestimate abilities across domains; this was the case for this patient. His General Ability Index (GAI) score was 130, in the very superior range and at the 98th percentile, placing him in the category of gifted intelligence. The patient’s processing speed, however, was at the 18th percentile, which explained his delayed response style and presence of developmental asynchrony, a concept occasionally reported when interpreting socio-emotional and educational maladjustment in gifted individuals.

We determined that Mr. T was twice exceptional—intellectually gifted and also having one or more areas of disability.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity .

In individuals with gifted intelligence, a discrepancy between cognitive and emotional development can make them vulnerable to behavioral and emotional challenges. It is not uncommon for gifted individuals to experience co-occurring distress, anxiety, depression, social withdrawal, difficulty coping with challenging tasks and experiences, low self-esteem, and excessive perfectionism.1-6 Giftedness accompanied by a delay in general abilities and processing speed (significant verbal-performance discrepancy) places an individual in the category of twice-exceptionality, or “2E”—having the potential for high achievement while displaying evidence of 1 or more disabilities including emotional or behavioral difficulties.7

2E Individuals: Prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes

Reported prevalence of twice-exceptionality varies, from approximately 180,000 to 360,000 students in the United States.7 In 2009, the National Commission on Twice Exceptional Students provided the following definition of twice exceptionality:7,8

“Twice-exceptional learners are students who demonstrate the potential for high achievement or creative productivity in one or more domains such as math, science, technology, the social arts, the visual, spatial, or performing arts or other areas of human productivity AND who manifest one or more disabilities as defined by federal or state eligibility criteria. These disabilities include specific learning disabilities; speech and language disorders; emotional/behavioral disorders; physical disabilities; Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD); or other health impairments, such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).”

How twice-exceptionality might manifest. The literature describes 3 unique groupings of 2E children: those who excel early due to strong language abilities, but later show signs of disability, often when curricular demands rise in junior high, high school, or even college; students diagnosed with disability, but who show exceptional gifts in some areas that may be masked by their learning difficulties; and highly intelligent students who seem to be average, because their disabilities mask their giftedness or their talents mask their difficulties.9,10

Unique behavioral and emotional challenges of 2E individuals may include lower motivation and academic self-efficacy, low self-worth and feelings of failure, or disruptive behaviors.7,11,12 Anxiety and depression often result from the functional impact of twice-exceptionality as well as resultant withdrawal, social isolation, and delay or hindrance of social skills (such as difficulty interpreting social cues).13,14 The individual in our case displayed many of these challenges, including lower motivation, self-worth, and self-esteem, and comorbid anxiety and depression (TABLE 1), further clouding diagnostic clarity.

Continue to: The need for improved recognition

The need for improved recognition. Twice-exceptionality commonly manifests as children reach grade-school age, but they are underrepresented in programs for the gifted due to misunderstanding and misdiagnosis by professionals.15,16 Best practices in identifying 2E children incorporate multidimensional assessments including pre-referral and screening, preliminary intervention, evaluation procedures, and educational planning.16 Despite research asserting that 2E individuals need more support services, knowing how to best identify and support individuals across various settings can prove difficult.7,17-19

Primary care, as we will discuss in a bit, is an interdisciplinary setting in which identification and comprehensive and collaborative support can occur. Historically, though, mental and physical health care have been “siloed” and mental health professionals’ functions in medical settings have often been circumscribed.20,21

A lesson from how our case unfolded

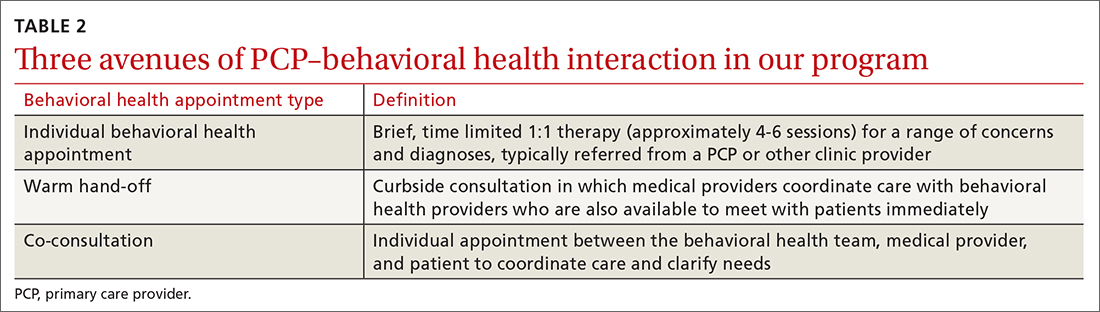

Our integrated health team, known as Integrated Behavioral Health Plus (IBH+), was developed at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and is a system-level integration of behavioral health professionals working with medical providers to improve outcomes and satisfaction.22 Psychology supervisors and trainees, telepsychiatrists and psychiatry residents, social workers, and pharmacists work together with PCPs and residents to deliver comprehensive patient care. Our model includes a range of behavioral health access points for patients (TABLE 2) and the use of complex patient databases and care team meetings.

In the case we have described here, the nature of the patient’s presentation did not trigger any of the clinical procedures described in TABLE 2, and he fell under the radar of complex patient cases in the clinic. Instead, informal, asynchronous clinical conversations between providers were what eventually lead to diagnostic clarification. Team consultation and psychometric testing provided by IBH+ helped uncover the “hidden diagnosis” of this patient in primary care and identified him as twice-exceptional, experiencing both giftedness and significant emotional suffering (major depression and social anxiety, low self-esteem and self-worth).

Takeaways for primary care

Not all PCPs, of course, have immediate onsite access to a program such as ours. However, innovative ways to tap into available resources might include establishing a partnership with 1 or more behavioral health professionals or bridging less formal relationships with such providers in the community and schools to more easily share patient records.

Continue to: Other presentations within 2E populations

Other presentations within 2E populations. 2E individuals may have other presentations coupled with high cognitive ability7: symptoms of hyperactivity disorders; specific learning disabilities; a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (previously termed Asperger type); attention, organizational, social, and behavioral issues; and impulsivity or emotional volatility.

Of note, the perspective of our care team shifted from a “bugs and drugs” perspective of diagnosis and treatment—biological explanations and pharmaceutical solutions—to an approach that explored the underlying interplay between cognitive and emotional functioning for this individual. Our treatment focused on a strengths-based and patient-centered approach. Even without the resources of a full IBH+ model, primary care practices may be able to adapt our experience to their ever-growing complex populations.

Our team shifted treatment planning to the needs of the patient. The 2E identification changed the patient’s perspective about himself. After learning of his giftedness, the patient was able to reframe himself as a highly intelligent, capable individual in need of treatment for depression and social anxiety, as opposed to questioning his intelligence and experiencing confusion and hopelessness within the medical system. His PCP collaborated with the team via telecommunication to maintain an efficacious antidepressant plan and to use a strengths-based approach focused on increasing the patient’s self-view and changing the illness narrative. This narrative was changed by practicing skills, such as challenging unhelpful thought patterns, setting beneficial boundaries, and supporting assertive communication to oppose thoughts and relationships that perpetuated old, negative beliefs and assumptions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn S. Saldaña, PhD, University of Colorado, 12631 East 17th Avenue, AO1 L15, 3rd Floor, Aurora, CO 80045; kathryn. saldana@ucdenver.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to A.F. Williams Family Medicine Clinic and the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus School of Medicine for their unparalleled models of resident training and multidisciplinary care.

1. Guénolé F, Louis J, Creveuil C, et al. Behavioral profiles of clinically referred children with intellectual giftedness. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:540153.

2. Alesi M, Rappo G, Pepi A. Emotional profile and intellectual functioning: A comparison among children with borderline intellectual functioning, average intellectual functioning, and gifted intellectual functioning. SAGE Open. 2015;5:2158244015589995.

3. Alsop G. Asynchrony: intuitively valid and theoretically reliable. Roeper Rev. 2003;25:118-127.

4. Guignard J-H, Jacquet A-Y, Lubart TI. Perfectionism and anxiety: a paradox in intellectual giftedness? PloS One. 2012;7:e41043.

5. Reis SM, McCoach DB. The underachievement of gifted students: What do we know and where do we go? Gifted Child Quarterly. 2000;44:152-170.

6. Barchmann H, Kinze W. Behaviour and achievement disorders in children with high intelligence. Acta Paedopsychiatr. 1990;53:168-172.

7. Reis SM, Baum SM, Burke E. An operational definition of twice-exceptional learners: implications and applications. Gifted Child Quarterly. 2014;58:217-230.

8. NAGC Position Statements & White Papers. Accessed September 18, 2021. http://www.nagc.org/index.aspx?id=5094

9. Neihart M. Identifying and providing services to twice exceptional children. In: Handbook of Giftedness in Children. Pfeiffer SI, ed. Springer; 2008:115-137.

10. Baum SM, Owen SV. To Be Gifted & Learning Disabled: Strategies for Helping Bright Students with Learning & Attention Difficulties. Prufrock Press Inc; 2004.

11. Reis SM. Talents in two places: case studies of high ability students with learning disabilities who have achieved. [Research Monograph 95114]. 1995.

12. Schiff MM, Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Scatter analysis of WISC-R profiles for learning disabled children with superior intelligence. J Learn Disabil. 1981;14:400-404.

13. King EW. Addressing the social and emotional needs of twice-exceptional students. Teaching Exceptional Child. 2005;38:16-21.

14. Stormont M, Stebbins MS, Holliday G. Characteristics and educational support needs of underrepresented gifted adolescents. Psychol Schools. 2001;38:413-423.

15. Morrison WF, Rizza MG. Creating a toolkit for identifying twice-exceptional students. J Educ Gifted. 2007;31:57-76.

16. Rizza MG, Morrison WF. Identifying twice exceptional children: a toolkit for success. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ967126.pdf

17. Cohen SS, Vaughn S. Gifted students with learning disabilities: what does the research say? Learn Disabil. 1994;5:87-94.

18. National Center for Education Statistics. Students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp

19. The Hechinger Report. Twice exceptional, doubly disadvantaged? How schools struggle to serve gifted students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://hechingerreport.org/twice-exceptional-doubly-disadvantaged-how-schools-struggle-to-serve-gifted-students-with-disabilities

20. Mendaglio S. Heightened multifaceted sensitivity of gifted students: implications for counseling. J Secondary Gifted Educ. 2002;14:72-82.

21. Pereles DA, Omdal S, Baldwin L. Response to intervention and twice-exceptional learners: a promising fit. Gifted Child Today. 2009;32:40-51.

22. Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: evidence update 2010-2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. 2016. Accessed September 18, 2021. www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolving-Models-of-BHI.pdf

THE CASE

Michael T,* a 20-year-old cisgender male, visited one of our clinic’s primary care physicians (PCPs). He was reserved and quiet and spoke of his concerns about depression and social anxiety that had been present for several years. He also spoke of his inability to succeed at work and school. Following a thorough PCP review leading to diagnoses of major depressive disorder and social anxiety, the patient agreed to try medication. Over a period of 15 months, trials of medications including fluoxetine, sertraline, aripiprazole, and duloxetine did little to improve the patient’s mood. The PCP decided to consult with our clinic’s integrated health team.

The team reviewed several diagnostic possibilities (TABLE 1) and agreed with the PCP’s diagnoses of major depression and social anxiety. But these disorders alone did not explain the full picture. Team members noted the patient’s unusual communication style, characterized by remarkably long response times and slow processing speed. In particular, when discussing mood, he took several seconds to respond but would respond thoughtfully and with few words.

We administered the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV). Due to differences between the 4 indices within the WAIS-IV, the Full Scale Intelligence Quotient may under- or overestimate abilities across domains; this was the case for this patient. His General Ability Index (GAI) score was 130, in the very superior range and at the 98th percentile, placing him in the category of gifted intelligence. The patient’s processing speed, however, was at the 18th percentile, which explained his delayed response style and presence of developmental asynchrony, a concept occasionally reported when interpreting socio-emotional and educational maladjustment in gifted individuals.

We determined that Mr. T was twice exceptional—intellectually gifted and also having one or more areas of disability.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity .

In individuals with gifted intelligence, a discrepancy between cognitive and emotional development can make them vulnerable to behavioral and emotional challenges. It is not uncommon for gifted individuals to experience co-occurring distress, anxiety, depression, social withdrawal, difficulty coping with challenging tasks and experiences, low self-esteem, and excessive perfectionism.1-6 Giftedness accompanied by a delay in general abilities and processing speed (significant verbal-performance discrepancy) places an individual in the category of twice-exceptionality, or “2E”—having the potential for high achievement while displaying evidence of 1 or more disabilities including emotional or behavioral difficulties.7

2E Individuals: Prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes

Reported prevalence of twice-exceptionality varies, from approximately 180,000 to 360,000 students in the United States.7 In 2009, the National Commission on Twice Exceptional Students provided the following definition of twice exceptionality:7,8

“Twice-exceptional learners are students who demonstrate the potential for high achievement or creative productivity in one or more domains such as math, science, technology, the social arts, the visual, spatial, or performing arts or other areas of human productivity AND who manifest one or more disabilities as defined by federal or state eligibility criteria. These disabilities include specific learning disabilities; speech and language disorders; emotional/behavioral disorders; physical disabilities; Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD); or other health impairments, such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).”

How twice-exceptionality might manifest. The literature describes 3 unique groupings of 2E children: those who excel early due to strong language abilities, but later show signs of disability, often when curricular demands rise in junior high, high school, or even college; students diagnosed with disability, but who show exceptional gifts in some areas that may be masked by their learning difficulties; and highly intelligent students who seem to be average, because their disabilities mask their giftedness or their talents mask their difficulties.9,10

Unique behavioral and emotional challenges of 2E individuals may include lower motivation and academic self-efficacy, low self-worth and feelings of failure, or disruptive behaviors.7,11,12 Anxiety and depression often result from the functional impact of twice-exceptionality as well as resultant withdrawal, social isolation, and delay or hindrance of social skills (such as difficulty interpreting social cues).13,14 The individual in our case displayed many of these challenges, including lower motivation, self-worth, and self-esteem, and comorbid anxiety and depression (TABLE 1), further clouding diagnostic clarity.

Continue to: The need for improved recognition

The need for improved recognition. Twice-exceptionality commonly manifests as children reach grade-school age, but they are underrepresented in programs for the gifted due to misunderstanding and misdiagnosis by professionals.15,16 Best practices in identifying 2E children incorporate multidimensional assessments including pre-referral and screening, preliminary intervention, evaluation procedures, and educational planning.16 Despite research asserting that 2E individuals need more support services, knowing how to best identify and support individuals across various settings can prove difficult.7,17-19

Primary care, as we will discuss in a bit, is an interdisciplinary setting in which identification and comprehensive and collaborative support can occur. Historically, though, mental and physical health care have been “siloed” and mental health professionals’ functions in medical settings have often been circumscribed.20,21

A lesson from how our case unfolded

Our integrated health team, known as Integrated Behavioral Health Plus (IBH+), was developed at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and is a system-level integration of behavioral health professionals working with medical providers to improve outcomes and satisfaction.22 Psychology supervisors and trainees, telepsychiatrists and psychiatry residents, social workers, and pharmacists work together with PCPs and residents to deliver comprehensive patient care. Our model includes a range of behavioral health access points for patients (TABLE 2) and the use of complex patient databases and care team meetings.

In the case we have described here, the nature of the patient’s presentation did not trigger any of the clinical procedures described in TABLE 2, and he fell under the radar of complex patient cases in the clinic. Instead, informal, asynchronous clinical conversations between providers were what eventually lead to diagnostic clarification. Team consultation and psychometric testing provided by IBH+ helped uncover the “hidden diagnosis” of this patient in primary care and identified him as twice-exceptional, experiencing both giftedness and significant emotional suffering (major depression and social anxiety, low self-esteem and self-worth).

Takeaways for primary care

Not all PCPs, of course, have immediate onsite access to a program such as ours. However, innovative ways to tap into available resources might include establishing a partnership with 1 or more behavioral health professionals or bridging less formal relationships with such providers in the community and schools to more easily share patient records.

Continue to: Other presentations within 2E populations

Other presentations within 2E populations. 2E individuals may have other presentations coupled with high cognitive ability7: symptoms of hyperactivity disorders; specific learning disabilities; a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (previously termed Asperger type); attention, organizational, social, and behavioral issues; and impulsivity or emotional volatility.

Of note, the perspective of our care team shifted from a “bugs and drugs” perspective of diagnosis and treatment—biological explanations and pharmaceutical solutions—to an approach that explored the underlying interplay between cognitive and emotional functioning for this individual. Our treatment focused on a strengths-based and patient-centered approach. Even without the resources of a full IBH+ model, primary care practices may be able to adapt our experience to their ever-growing complex populations.

Our team shifted treatment planning to the needs of the patient. The 2E identification changed the patient’s perspective about himself. After learning of his giftedness, the patient was able to reframe himself as a highly intelligent, capable individual in need of treatment for depression and social anxiety, as opposed to questioning his intelligence and experiencing confusion and hopelessness within the medical system. His PCP collaborated with the team via telecommunication to maintain an efficacious antidepressant plan and to use a strengths-based approach focused on increasing the patient’s self-view and changing the illness narrative. This narrative was changed by practicing skills, such as challenging unhelpful thought patterns, setting beneficial boundaries, and supporting assertive communication to oppose thoughts and relationships that perpetuated old, negative beliefs and assumptions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn S. Saldaña, PhD, University of Colorado, 12631 East 17th Avenue, AO1 L15, 3rd Floor, Aurora, CO 80045; kathryn. saldana@ucdenver.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to A.F. Williams Family Medicine Clinic and the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus School of Medicine for their unparalleled models of resident training and multidisciplinary care.

THE CASE

Michael T,* a 20-year-old cisgender male, visited one of our clinic’s primary care physicians (PCPs). He was reserved and quiet and spoke of his concerns about depression and social anxiety that had been present for several years. He also spoke of his inability to succeed at work and school. Following a thorough PCP review leading to diagnoses of major depressive disorder and social anxiety, the patient agreed to try medication. Over a period of 15 months, trials of medications including fluoxetine, sertraline, aripiprazole, and duloxetine did little to improve the patient’s mood. The PCP decided to consult with our clinic’s integrated health team.

The team reviewed several diagnostic possibilities (TABLE 1) and agreed with the PCP’s diagnoses of major depression and social anxiety. But these disorders alone did not explain the full picture. Team members noted the patient’s unusual communication style, characterized by remarkably long response times and slow processing speed. In particular, when discussing mood, he took several seconds to respond but would respond thoughtfully and with few words.

We administered the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV). Due to differences between the 4 indices within the WAIS-IV, the Full Scale Intelligence Quotient may under- or overestimate abilities across domains; this was the case for this patient. His General Ability Index (GAI) score was 130, in the very superior range and at the 98th percentile, placing him in the category of gifted intelligence. The patient’s processing speed, however, was at the 18th percentile, which explained his delayed response style and presence of developmental asynchrony, a concept occasionally reported when interpreting socio-emotional and educational maladjustment in gifted individuals.

We determined that Mr. T was twice exceptional—intellectually gifted and also having one or more areas of disability.

●

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity .

In individuals with gifted intelligence, a discrepancy between cognitive and emotional development can make them vulnerable to behavioral and emotional challenges. It is not uncommon for gifted individuals to experience co-occurring distress, anxiety, depression, social withdrawal, difficulty coping with challenging tasks and experiences, low self-esteem, and excessive perfectionism.1-6 Giftedness accompanied by a delay in general abilities and processing speed (significant verbal-performance discrepancy) places an individual in the category of twice-exceptionality, or “2E”—having the potential for high achievement while displaying evidence of 1 or more disabilities including emotional or behavioral difficulties.7

2E Individuals: Prevalence, characteristics, and outcomes

Reported prevalence of twice-exceptionality varies, from approximately 180,000 to 360,000 students in the United States.7 In 2009, the National Commission on Twice Exceptional Students provided the following definition of twice exceptionality:7,8

“Twice-exceptional learners are students who demonstrate the potential for high achievement or creative productivity in one or more domains such as math, science, technology, the social arts, the visual, spatial, or performing arts or other areas of human productivity AND who manifest one or more disabilities as defined by federal or state eligibility criteria. These disabilities include specific learning disabilities; speech and language disorders; emotional/behavioral disorders; physical disabilities; Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD); or other health impairments, such as Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).”

How twice-exceptionality might manifest. The literature describes 3 unique groupings of 2E children: those who excel early due to strong language abilities, but later show signs of disability, often when curricular demands rise in junior high, high school, or even college; students diagnosed with disability, but who show exceptional gifts in some areas that may be masked by their learning difficulties; and highly intelligent students who seem to be average, because their disabilities mask their giftedness or their talents mask their difficulties.9,10

Unique behavioral and emotional challenges of 2E individuals may include lower motivation and academic self-efficacy, low self-worth and feelings of failure, or disruptive behaviors.7,11,12 Anxiety and depression often result from the functional impact of twice-exceptionality as well as resultant withdrawal, social isolation, and delay or hindrance of social skills (such as difficulty interpreting social cues).13,14 The individual in our case displayed many of these challenges, including lower motivation, self-worth, and self-esteem, and comorbid anxiety and depression (TABLE 1), further clouding diagnostic clarity.

Continue to: The need for improved recognition

The need for improved recognition. Twice-exceptionality commonly manifests as children reach grade-school age, but they are underrepresented in programs for the gifted due to misunderstanding and misdiagnosis by professionals.15,16 Best practices in identifying 2E children incorporate multidimensional assessments including pre-referral and screening, preliminary intervention, evaluation procedures, and educational planning.16 Despite research asserting that 2E individuals need more support services, knowing how to best identify and support individuals across various settings can prove difficult.7,17-19

Primary care, as we will discuss in a bit, is an interdisciplinary setting in which identification and comprehensive and collaborative support can occur. Historically, though, mental and physical health care have been “siloed” and mental health professionals’ functions in medical settings have often been circumscribed.20,21

A lesson from how our case unfolded

Our integrated health team, known as Integrated Behavioral Health Plus (IBH+), was developed at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and is a system-level integration of behavioral health professionals working with medical providers to improve outcomes and satisfaction.22 Psychology supervisors and trainees, telepsychiatrists and psychiatry residents, social workers, and pharmacists work together with PCPs and residents to deliver comprehensive patient care. Our model includes a range of behavioral health access points for patients (TABLE 2) and the use of complex patient databases and care team meetings.

In the case we have described here, the nature of the patient’s presentation did not trigger any of the clinical procedures described in TABLE 2, and he fell under the radar of complex patient cases in the clinic. Instead, informal, asynchronous clinical conversations between providers were what eventually lead to diagnostic clarification. Team consultation and psychometric testing provided by IBH+ helped uncover the “hidden diagnosis” of this patient in primary care and identified him as twice-exceptional, experiencing both giftedness and significant emotional suffering (major depression and social anxiety, low self-esteem and self-worth).

Takeaways for primary care

Not all PCPs, of course, have immediate onsite access to a program such as ours. However, innovative ways to tap into available resources might include establishing a partnership with 1 or more behavioral health professionals or bridging less formal relationships with such providers in the community and schools to more easily share patient records.

Continue to: Other presentations within 2E populations

Other presentations within 2E populations. 2E individuals may have other presentations coupled with high cognitive ability7: symptoms of hyperactivity disorders; specific learning disabilities; a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (previously termed Asperger type); attention, organizational, social, and behavioral issues; and impulsivity or emotional volatility.

Of note, the perspective of our care team shifted from a “bugs and drugs” perspective of diagnosis and treatment—biological explanations and pharmaceutical solutions—to an approach that explored the underlying interplay between cognitive and emotional functioning for this individual. Our treatment focused on a strengths-based and patient-centered approach. Even without the resources of a full IBH+ model, primary care practices may be able to adapt our experience to their ever-growing complex populations.

Our team shifted treatment planning to the needs of the patient. The 2E identification changed the patient’s perspective about himself. After learning of his giftedness, the patient was able to reframe himself as a highly intelligent, capable individual in need of treatment for depression and social anxiety, as opposed to questioning his intelligence and experiencing confusion and hopelessness within the medical system. His PCP collaborated with the team via telecommunication to maintain an efficacious antidepressant plan and to use a strengths-based approach focused on increasing the patient’s self-view and changing the illness narrative. This narrative was changed by practicing skills, such as challenging unhelpful thought patterns, setting beneficial boundaries, and supporting assertive communication to oppose thoughts and relationships that perpetuated old, negative beliefs and assumptions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn S. Saldaña, PhD, University of Colorado, 12631 East 17th Avenue, AO1 L15, 3rd Floor, Aurora, CO 80045; kathryn. saldana@ucdenver.edu.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks to A.F. Williams Family Medicine Clinic and the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus School of Medicine for their unparalleled models of resident training and multidisciplinary care.

1. Guénolé F, Louis J, Creveuil C, et al. Behavioral profiles of clinically referred children with intellectual giftedness. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:540153.

2. Alesi M, Rappo G, Pepi A. Emotional profile and intellectual functioning: A comparison among children with borderline intellectual functioning, average intellectual functioning, and gifted intellectual functioning. SAGE Open. 2015;5:2158244015589995.

3. Alsop G. Asynchrony: intuitively valid and theoretically reliable. Roeper Rev. 2003;25:118-127.

4. Guignard J-H, Jacquet A-Y, Lubart TI. Perfectionism and anxiety: a paradox in intellectual giftedness? PloS One. 2012;7:e41043.

5. Reis SM, McCoach DB. The underachievement of gifted students: What do we know and where do we go? Gifted Child Quarterly. 2000;44:152-170.

6. Barchmann H, Kinze W. Behaviour and achievement disorders in children with high intelligence. Acta Paedopsychiatr. 1990;53:168-172.

7. Reis SM, Baum SM, Burke E. An operational definition of twice-exceptional learners: implications and applications. Gifted Child Quarterly. 2014;58:217-230.

8. NAGC Position Statements & White Papers. Accessed September 18, 2021. http://www.nagc.org/index.aspx?id=5094

9. Neihart M. Identifying and providing services to twice exceptional children. In: Handbook of Giftedness in Children. Pfeiffer SI, ed. Springer; 2008:115-137.

10. Baum SM, Owen SV. To Be Gifted & Learning Disabled: Strategies for Helping Bright Students with Learning & Attention Difficulties. Prufrock Press Inc; 2004.

11. Reis SM. Talents in two places: case studies of high ability students with learning disabilities who have achieved. [Research Monograph 95114]. 1995.

12. Schiff MM, Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Scatter analysis of WISC-R profiles for learning disabled children with superior intelligence. J Learn Disabil. 1981;14:400-404.

13. King EW. Addressing the social and emotional needs of twice-exceptional students. Teaching Exceptional Child. 2005;38:16-21.

14. Stormont M, Stebbins MS, Holliday G. Characteristics and educational support needs of underrepresented gifted adolescents. Psychol Schools. 2001;38:413-423.

15. Morrison WF, Rizza MG. Creating a toolkit for identifying twice-exceptional students. J Educ Gifted. 2007;31:57-76.

16. Rizza MG, Morrison WF. Identifying twice exceptional children: a toolkit for success. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ967126.pdf

17. Cohen SS, Vaughn S. Gifted students with learning disabilities: what does the research say? Learn Disabil. 1994;5:87-94.

18. National Center for Education Statistics. Students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp

19. The Hechinger Report. Twice exceptional, doubly disadvantaged? How schools struggle to serve gifted students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://hechingerreport.org/twice-exceptional-doubly-disadvantaged-how-schools-struggle-to-serve-gifted-students-with-disabilities

20. Mendaglio S. Heightened multifaceted sensitivity of gifted students: implications for counseling. J Secondary Gifted Educ. 2002;14:72-82.

21. Pereles DA, Omdal S, Baldwin L. Response to intervention and twice-exceptional learners: a promising fit. Gifted Child Today. 2009;32:40-51.

22. Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: evidence update 2010-2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. 2016. Accessed September 18, 2021. www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolving-Models-of-BHI.pdf

1. Guénolé F, Louis J, Creveuil C, et al. Behavioral profiles of clinically referred children with intellectual giftedness. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:540153.

2. Alesi M, Rappo G, Pepi A. Emotional profile and intellectual functioning: A comparison among children with borderline intellectual functioning, average intellectual functioning, and gifted intellectual functioning. SAGE Open. 2015;5:2158244015589995.

3. Alsop G. Asynchrony: intuitively valid and theoretically reliable. Roeper Rev. 2003;25:118-127.

4. Guignard J-H, Jacquet A-Y, Lubart TI. Perfectionism and anxiety: a paradox in intellectual giftedness? PloS One. 2012;7:e41043.

5. Reis SM, McCoach DB. The underachievement of gifted students: What do we know and where do we go? Gifted Child Quarterly. 2000;44:152-170.

6. Barchmann H, Kinze W. Behaviour and achievement disorders in children with high intelligence. Acta Paedopsychiatr. 1990;53:168-172.

7. Reis SM, Baum SM, Burke E. An operational definition of twice-exceptional learners: implications and applications. Gifted Child Quarterly. 2014;58:217-230.

8. NAGC Position Statements & White Papers. Accessed September 18, 2021. http://www.nagc.org/index.aspx?id=5094

9. Neihart M. Identifying and providing services to twice exceptional children. In: Handbook of Giftedness in Children. Pfeiffer SI, ed. Springer; 2008:115-137.

10. Baum SM, Owen SV. To Be Gifted & Learning Disabled: Strategies for Helping Bright Students with Learning & Attention Difficulties. Prufrock Press Inc; 2004.

11. Reis SM. Talents in two places: case studies of high ability students with learning disabilities who have achieved. [Research Monograph 95114]. 1995.

12. Schiff MM, Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Scatter analysis of WISC-R profiles for learning disabled children with superior intelligence. J Learn Disabil. 1981;14:400-404.

13. King EW. Addressing the social and emotional needs of twice-exceptional students. Teaching Exceptional Child. 2005;38:16-21.

14. Stormont M, Stebbins MS, Holliday G. Characteristics and educational support needs of underrepresented gifted adolescents. Psychol Schools. 2001;38:413-423.

15. Morrison WF, Rizza MG. Creating a toolkit for identifying twice-exceptional students. J Educ Gifted. 2007;31:57-76.

16. Rizza MG, Morrison WF. Identifying twice exceptional children: a toolkit for success. Accessed September 17, 2021. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ967126.pdf

17. Cohen SS, Vaughn S. Gifted students with learning disabilities: what does the research say? Learn Disabil. 1994;5:87-94.

18. National Center for Education Statistics. Students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgg.asp

19. The Hechinger Report. Twice exceptional, doubly disadvantaged? How schools struggle to serve gifted students with disabilities. Accessed September 18, 2021. https://hechingerreport.org/twice-exceptional-doubly-disadvantaged-how-schools-struggle-to-serve-gifted-students-with-disabilities

20. Mendaglio S. Heightened multifaceted sensitivity of gifted students: implications for counseling. J Secondary Gifted Educ. 2002;14:72-82.

21. Pereles DA, Omdal S, Baldwin L. Response to intervention and twice-exceptional learners: a promising fit. Gifted Child Today. 2009;32:40-51.

22. Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: evidence update 2010-2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. 2016. Accessed September 18, 2021. www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolving-Models-of-BHI.pdf

Painful blisters on fingertips and toes

A 52-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 4-month history of recurrent painful blisters on her fingertips and the tips of her toes (FIGURE 1), arthralgias, painful discoloration of her distal toes and fingers when exposed to cold, and painful nodules on her forearms. She was started on prednisone and was sent to our clinic for follow-up.

At her initial visit to our office, she was continued on prednisone and referred to Rheumatology and Interventional Cardiology, where a work-up for rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other vasculitides was negative. The patient had normal arterial pressures and a normal echocardiogram. An angiogram revealed segmental occlusions of the distal vessels in her arms and legs. The patient denied chest pain, syncope, dyspnea on exertion, or fever. She reported a >30 pack-year history of cigarette smoking.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Thromboangiitis obliterans

Thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO), or Buerger’s disease, is a rare nonatherosclerotic disease that affects the medium and small arteries. The disease has a male predominance, primarily occurs in those younger than 45 years of age, and is most common in people from the Middle and Far East.1 Its distinctive features include ulcerations of the distal extremities and symptoms of claudication and pain at rest. More than 40% of affected patients develop Raynaud’s phenomenon.1 Superficial thrombophlebitis in the form of painful nodules has also been described.2

The etiology of TAO is likely due to disordered inflammation of endothelial cells, which has a strong association with smoking.3 The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but genetics and autoimmunity are suspected contributing factors.

The diagnosis is based on exclusion of other causes

The differential diagnosis includes diabetic angiopathy, embolic disease, atherosclerosis, hypercoagulability/thrombophilia, vasculitis or connective tissue diseases, and drug-associated (eg, cocaine) vasculitis.4

The diagnosis of TAO is based on the exclusion of other causes, although several diagnostic criteria have been proposed, including:

- age <45 years

- current or recent history of tobacco use

- distal extremity involvement (ulcers, claudication, or pain at rest)

- exclusion of diabetes, peripheral artery disease, thrombophilia, or embolic disease

- typical arteriographic findings on imaging, including distal small to medium vessel involvement, segmental occlusions, and “corkscrew-shaped” collaterals.1,2,5,6

Continue to: Lab tests

Lab tests. There are no specific laboratory markers for TAO. The initial evaluation should include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), complete metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA). Tests to exclude other autoimmune diseases include rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticentromere antibody and Scl-70 to exclude CREST syndrome and scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibodies to exclude disorders of hypercoagulability, and drug testing and history-taking to evaluate for drug-related (eg, cocaine) etiologies. Further studies should be performed based on clinical suspicion.

Imaging. Patients with suspected TAO should undergo an arteriogram of the affected extremities and large arteries. Other imaging modalities include computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography. Biopsy is rarely indicated, unless there are atypical findings, such as large artery involvement or arterial nodules. Interestingly, a positive Allen test in a young smoker can be highly suggestive of TAO.1 (For a demonstration of the Allen test, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1tJO0RW9UM.)

Our patient tested negative for rheumatoid arthritis, CREST, and scleroderma and had a normal UA and CMP. She did have a slightly elevated anticardiolipin antibody test, but a negative lupus anticoagulant test, the significance of which is uncertain. Her CRP and ESR were elevated.

Complete smoking cessation is essential for treatment

Several treatments have been proposed, including prostanoids and surgery (surgical revascularization or endovascular therapy).1,4 In severe cases, amputation may be required to remove the affected extremity. However, the most important and most effective treatment for TAO is smoking cessation.1 Of note, several case reports have found that replacing smoking with other nicotine-containing products (eg, chewing tobacco) may not prevent limb loss.7-9

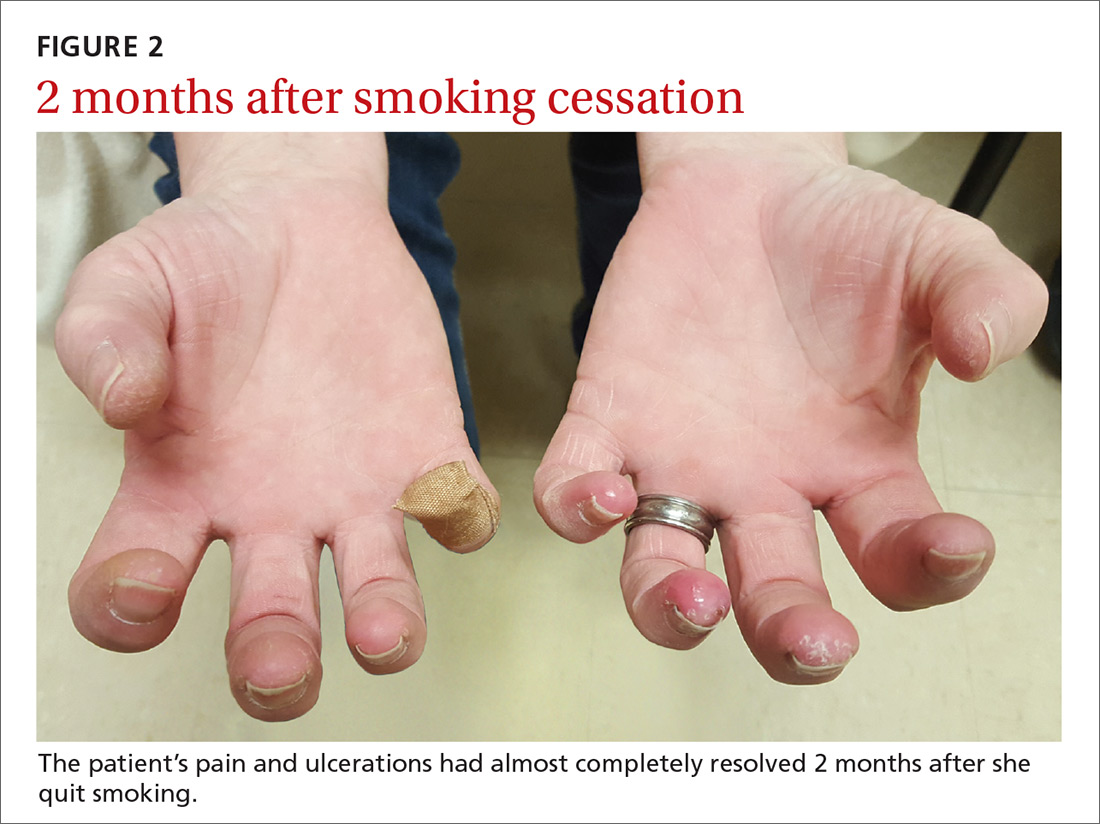

Our patient was tapered off prednisone and was continued on amlodipine 5 mg/d for vasospasm. She was started on varenicline 0.5 mg/d, which was increased to twice daily by Day 4 to aid with smoking cessation. Two months later, the patient’s pain and ulcerations had almost completely resolved (FIGURE 2). She experienced occasional relapses with smoking, during which her ulcerations and Raynaud’s would return. This case reinforces the age-old aphorism of “no tobacco, no Buerger’s disease.”4

CORRESPONDENCE

Seth Mathern, MD, 14300 Orchard Parkway, Westminster, CO 80023; Seth.Mathern@ucdenver.edu.

1. Olin JW. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). N Engl J Med. 2000;343:864-869.

2. Piazza G, Creager MA. Thromboangiitis obliterans. Circulation. 2010;121:1858-1861.

3. Azizi M, Boutouyrie P, Bura-Rivière A, et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans and endothelial function. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40:518-526.

4. Klein-Weigel PF, Richter JG. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). Vasa. 2014;43:337-346.

5. Papa MZ, Rabi I, Adar R. A point scoring system for the clinical diagnosis of Buerger’s disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;11:335-339.

6. Mills JL, Porter JM. Buerger’s disease: a review and update. Semin Vasc Surg. 1993;6:14-23.

7. Lie JT. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:812-813.

8. O’Dell JR, Linder J, Markin RS, et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:1054-1056.

9. Lawrence PF, Lund OI, Jimenez JC, et al. Substitution of smokeless tobacco for cigarettes in Buerger’s disease does not prevent limb loss. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:210-212.

A 52-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 4-month history of recurrent painful blisters on her fingertips and the tips of her toes (FIGURE 1), arthralgias, painful discoloration of her distal toes and fingers when exposed to cold, and painful nodules on her forearms. She was started on prednisone and was sent to our clinic for follow-up.

At her initial visit to our office, she was continued on prednisone and referred to Rheumatology and Interventional Cardiology, where a work-up for rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other vasculitides was negative. The patient had normal arterial pressures and a normal echocardiogram. An angiogram revealed segmental occlusions of the distal vessels in her arms and legs. The patient denied chest pain, syncope, dyspnea on exertion, or fever. She reported a >30 pack-year history of cigarette smoking.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Thromboangiitis obliterans

Thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO), or Buerger’s disease, is a rare nonatherosclerotic disease that affects the medium and small arteries. The disease has a male predominance, primarily occurs in those younger than 45 years of age, and is most common in people from the Middle and Far East.1 Its distinctive features include ulcerations of the distal extremities and symptoms of claudication and pain at rest. More than 40% of affected patients develop Raynaud’s phenomenon.1 Superficial thrombophlebitis in the form of painful nodules has also been described.2

The etiology of TAO is likely due to disordered inflammation of endothelial cells, which has a strong association with smoking.3 The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but genetics and autoimmunity are suspected contributing factors.

The diagnosis is based on exclusion of other causes

The differential diagnosis includes diabetic angiopathy, embolic disease, atherosclerosis, hypercoagulability/thrombophilia, vasculitis or connective tissue diseases, and drug-associated (eg, cocaine) vasculitis.4

The diagnosis of TAO is based on the exclusion of other causes, although several diagnostic criteria have been proposed, including:

- age <45 years

- current or recent history of tobacco use

- distal extremity involvement (ulcers, claudication, or pain at rest)

- exclusion of diabetes, peripheral artery disease, thrombophilia, or embolic disease

- typical arteriographic findings on imaging, including distal small to medium vessel involvement, segmental occlusions, and “corkscrew-shaped” collaterals.1,2,5,6

Continue to: Lab tests

Lab tests. There are no specific laboratory markers for TAO. The initial evaluation should include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), complete metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA). Tests to exclude other autoimmune diseases include rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticentromere antibody and Scl-70 to exclude CREST syndrome and scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibodies to exclude disorders of hypercoagulability, and drug testing and history-taking to evaluate for drug-related (eg, cocaine) etiologies. Further studies should be performed based on clinical suspicion.

Imaging. Patients with suspected TAO should undergo an arteriogram of the affected extremities and large arteries. Other imaging modalities include computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography. Biopsy is rarely indicated, unless there are atypical findings, such as large artery involvement or arterial nodules. Interestingly, a positive Allen test in a young smoker can be highly suggestive of TAO.1 (For a demonstration of the Allen test, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1tJO0RW9UM.)

Our patient tested negative for rheumatoid arthritis, CREST, and scleroderma and had a normal UA and CMP. She did have a slightly elevated anticardiolipin antibody test, but a negative lupus anticoagulant test, the significance of which is uncertain. Her CRP and ESR were elevated.

Complete smoking cessation is essential for treatment

Several treatments have been proposed, including prostanoids and surgery (surgical revascularization or endovascular therapy).1,4 In severe cases, amputation may be required to remove the affected extremity. However, the most important and most effective treatment for TAO is smoking cessation.1 Of note, several case reports have found that replacing smoking with other nicotine-containing products (eg, chewing tobacco) may not prevent limb loss.7-9

Our patient was tapered off prednisone and was continued on amlodipine 5 mg/d for vasospasm. She was started on varenicline 0.5 mg/d, which was increased to twice daily by Day 4 to aid with smoking cessation. Two months later, the patient’s pain and ulcerations had almost completely resolved (FIGURE 2). She experienced occasional relapses with smoking, during which her ulcerations and Raynaud’s would return. This case reinforces the age-old aphorism of “no tobacco, no Buerger’s disease.”4

CORRESPONDENCE

Seth Mathern, MD, 14300 Orchard Parkway, Westminster, CO 80023; Seth.Mathern@ucdenver.edu.

A 52-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 4-month history of recurrent painful blisters on her fingertips and the tips of her toes (FIGURE 1), arthralgias, painful discoloration of her distal toes and fingers when exposed to cold, and painful nodules on her forearms. She was started on prednisone and was sent to our clinic for follow-up.

At her initial visit to our office, she was continued on prednisone and referred to Rheumatology and Interventional Cardiology, where a work-up for rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other vasculitides was negative. The patient had normal arterial pressures and a normal echocardiogram. An angiogram revealed segmental occlusions of the distal vessels in her arms and legs. The patient denied chest pain, syncope, dyspnea on exertion, or fever. She reported a >30 pack-year history of cigarette smoking.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Thromboangiitis obliterans

Thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO), or Buerger’s disease, is a rare nonatherosclerotic disease that affects the medium and small arteries. The disease has a male predominance, primarily occurs in those younger than 45 years of age, and is most common in people from the Middle and Far East.1 Its distinctive features include ulcerations of the distal extremities and symptoms of claudication and pain at rest. More than 40% of affected patients develop Raynaud’s phenomenon.1 Superficial thrombophlebitis in the form of painful nodules has also been described.2

The etiology of TAO is likely due to disordered inflammation of endothelial cells, which has a strong association with smoking.3 The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but genetics and autoimmunity are suspected contributing factors.

The diagnosis is based on exclusion of other causes

The differential diagnosis includes diabetic angiopathy, embolic disease, atherosclerosis, hypercoagulability/thrombophilia, vasculitis or connective tissue diseases, and drug-associated (eg, cocaine) vasculitis.4

The diagnosis of TAO is based on the exclusion of other causes, although several diagnostic criteria have been proposed, including:

- age <45 years

- current or recent history of tobacco use

- distal extremity involvement (ulcers, claudication, or pain at rest)

- exclusion of diabetes, peripheral artery disease, thrombophilia, or embolic disease

- typical arteriographic findings on imaging, including distal small to medium vessel involvement, segmental occlusions, and “corkscrew-shaped” collaterals.1,2,5,6

Continue to: Lab tests

Lab tests. There are no specific laboratory markers for TAO. The initial evaluation should include an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), complete metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA). Tests to exclude other autoimmune diseases include rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticentromere antibody and Scl-70 to exclude CREST syndrome and scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibodies to exclude disorders of hypercoagulability, and drug testing and history-taking to evaluate for drug-related (eg, cocaine) etiologies. Further studies should be performed based on clinical suspicion.

Imaging. Patients with suspected TAO should undergo an arteriogram of the affected extremities and large arteries. Other imaging modalities include computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography. Biopsy is rarely indicated, unless there are atypical findings, such as large artery involvement or arterial nodules. Interestingly, a positive Allen test in a young smoker can be highly suggestive of TAO.1 (For a demonstration of the Allen test, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1tJO0RW9UM.)

Our patient tested negative for rheumatoid arthritis, CREST, and scleroderma and had a normal UA and CMP. She did have a slightly elevated anticardiolipin antibody test, but a negative lupus anticoagulant test, the significance of which is uncertain. Her CRP and ESR were elevated.

Complete smoking cessation is essential for treatment

Several treatments have been proposed, including prostanoids and surgery (surgical revascularization or endovascular therapy).1,4 In severe cases, amputation may be required to remove the affected extremity. However, the most important and most effective treatment for TAO is smoking cessation.1 Of note, several case reports have found that replacing smoking with other nicotine-containing products (eg, chewing tobacco) may not prevent limb loss.7-9

Our patient was tapered off prednisone and was continued on amlodipine 5 mg/d for vasospasm. She was started on varenicline 0.5 mg/d, which was increased to twice daily by Day 4 to aid with smoking cessation. Two months later, the patient’s pain and ulcerations had almost completely resolved (FIGURE 2). She experienced occasional relapses with smoking, during which her ulcerations and Raynaud’s would return. This case reinforces the age-old aphorism of “no tobacco, no Buerger’s disease.”4

CORRESPONDENCE

Seth Mathern, MD, 14300 Orchard Parkway, Westminster, CO 80023; Seth.Mathern@ucdenver.edu.

1. Olin JW. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). N Engl J Med. 2000;343:864-869.

2. Piazza G, Creager MA. Thromboangiitis obliterans. Circulation. 2010;121:1858-1861.

3. Azizi M, Boutouyrie P, Bura-Rivière A, et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans and endothelial function. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40:518-526.

4. Klein-Weigel PF, Richter JG. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). Vasa. 2014;43:337-346.

5. Papa MZ, Rabi I, Adar R. A point scoring system for the clinical diagnosis of Buerger’s disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;11:335-339.

6. Mills JL, Porter JM. Buerger’s disease: a review and update. Semin Vasc Surg. 1993;6:14-23.

7. Lie JT. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:812-813.

8. O’Dell JR, Linder J, Markin RS, et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:1054-1056.

9. Lawrence PF, Lund OI, Jimenez JC, et al. Substitution of smokeless tobacco for cigarettes in Buerger’s disease does not prevent limb loss. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:210-212.

1. Olin JW. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). N Engl J Med. 2000;343:864-869.

2. Piazza G, Creager MA. Thromboangiitis obliterans. Circulation. 2010;121:1858-1861.

3. Azizi M, Boutouyrie P, Bura-Rivière A, et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans and endothelial function. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40:518-526.

4. Klein-Weigel PF, Richter JG. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). Vasa. 2014;43:337-346.

5. Papa MZ, Rabi I, Adar R. A point scoring system for the clinical diagnosis of Buerger’s disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;11:335-339.

6. Mills JL, Porter JM. Buerger’s disease: a review and update. Semin Vasc Surg. 1993;6:14-23.

7. Lie JT. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:812-813.

8. O’Dell JR, Linder J, Markin RS, et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:1054-1056.

9. Lawrence PF, Lund OI, Jimenez JC, et al. Substitution of smokeless tobacco for cigarettes in Buerger’s disease does not prevent limb loss. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:210-212.

A lump on the hip

A 42-year-old man presented with a lump on the side of his left hip, which had developed after he fell on his hip while playing basketball about 2 weeks earlier. He was able to continue playing and finished the game. After the game he noticed a lump, which rapidly increased in size. Significant bruising developed afterwards, and the area was mildly painful. The lump did not interfere with his daily activities, but it was annoying.

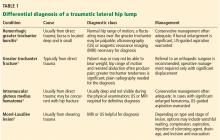

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Morel-Lavallée lesion is an uncommon condition resulting from shearing trauma and collection of fluid in the space between deep fatty tissue and superficial fascia.6 It is usually the result of severe trauma, as in a motor vehicle accident, but it can also result from sports-related trauma, as in our patient.6–8 Lateral hip, gluteal, and sacral regions are the most common locations for Morel-Lavallée lesions and are often associated with an underlying fracture.6,9

Morel-Lavallée lesions usually develop hours or days after trauma, although they may develop weeks or even months later.2 Symptoms include bulging, pain, and loss of cutaneous sensation over the affected area. Although ultrasonography can be used, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for diagnosis and staging.6,10 If there is concern for fracture, plain radiography should be performed.

Mellado and Bencardino classified Morel-Lavallée lesions into 6 types based on their morphology, presence or absence of a capsule, signal behavior on MRI, and enhancement pattern.10 The exact rate of infection in patients with Morel-Lavallée lesions is unknown; however, the risk of infection seems to be highest after surgical intervention or aspiration.5,6

Another potential complication is fluid reaccumulation, which most often occurs with large lesions (> 50 mL) and lesions with a fibrous capsule or pseudocapsule.5 Large lesions can compromise adjacent neurovascular structures, particularly in the extremities.5 Potential consequences include dermal necrosis, compartment syndrome, and tissue necrosis.5

MANAGEMENT APPROACH

Aspiration of a fluid-filled mass is useful in both diagnosis and management of Morel-Lavallée lesions. Treatment includes watchful waiting; compression and pressure wraps; injection of a sclerosing agent (eg, doxycyline, alcohol); needle aspiration; percutaneous drainage with debridement, irrigation, and suction; and incision and evacuation.6

The approach to treatment depends on the stage of the lesion and whether an underlying fracture is present. Depending on the amount of blood and lymphatic products and the acuity of the collected fluid (hours to days post-trauma), aspiration with a large-bore needle (eg, 14 to 22 gauge) may or may not be successful.7 In general, traumatic serosanguinous fluid collections are less painful and resolve faster than well-formed coagulated hematomas.

Patients who have a large lesion, significant pain, or decreased range of motion should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon.

Our patient was managed conservatively, and his symptoms completely resolved in 2 months.

- Ahmad Z, Tibrewal S, Waters G, Nolan J. Solitary amyloidoma related to THA. Orthopedics 2013; 36:e971–e973.

- Harris-Spinks C, Nabhan D, Khodaee M. Noniatrogenic septic olecranon bursitis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016; 15:33–37.

- Price MD, Busconi BD, McMillan S. Proximal femur fractures. In: Miller MD, Sanders TG, eds. Presentation, Imaging and Treatment of Common Musculoskeletal Conditions. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:365–376.

- Stanton MC, Maloney MD, Dehaven KE, Giordano BD. Acute traumatic tear of gluteus medius and minimus tendons in a patient without antecedant peritrochanteric hip pain. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2012; 3:84–88.

- Khodaee M, Deu RS, Mathern S, Bravman JT. Morel-Lavallée lesion in sports. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016; 15:417–422.

- Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, et al. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol 2014; 21:35–43.

- Khodaee M, Deu RS. Ankle Morel-Lavallée lesion in a recreational racquetball player. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2016. Epub ahead of print.

- Shmerling A, Bravman JT, Khodaee M. Morel-Lavallée lesion of the knee in a recreational frisbee player. Case Rep Orthop 2016; 2016:8723489.

- Miller J, Daggett J, Ambay R, Payne WG. Morel-Lavallée lesion. Eplasty 2014; 14:ic12.

- Mellado JM, Bencardino JT. Morel-Lavallée lesion: review with emphasis on MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2005; 13:775–782.

A 42-year-old man presented with a lump on the side of his left hip, which had developed after he fell on his hip while playing basketball about 2 weeks earlier. He was able to continue playing and finished the game. After the game he noticed a lump, which rapidly increased in size. Significant bruising developed afterwards, and the area was mildly painful. The lump did not interfere with his daily activities, but it was annoying.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Morel-Lavallée lesion is an uncommon condition resulting from shearing trauma and collection of fluid in the space between deep fatty tissue and superficial fascia.6 It is usually the result of severe trauma, as in a motor vehicle accident, but it can also result from sports-related trauma, as in our patient.6–8 Lateral hip, gluteal, and sacral regions are the most common locations for Morel-Lavallée lesions and are often associated with an underlying fracture.6,9

Morel-Lavallée lesions usually develop hours or days after trauma, although they may develop weeks or even months later.2 Symptoms include bulging, pain, and loss of cutaneous sensation over the affected area. Although ultrasonography can be used, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for diagnosis and staging.6,10 If there is concern for fracture, plain radiography should be performed.

Mellado and Bencardino classified Morel-Lavallée lesions into 6 types based on their morphology, presence or absence of a capsule, signal behavior on MRI, and enhancement pattern.10 The exact rate of infection in patients with Morel-Lavallée lesions is unknown; however, the risk of infection seems to be highest after surgical intervention or aspiration.5,6

Another potential complication is fluid reaccumulation, which most often occurs with large lesions (> 50 mL) and lesions with a fibrous capsule or pseudocapsule.5 Large lesions can compromise adjacent neurovascular structures, particularly in the extremities.5 Potential consequences include dermal necrosis, compartment syndrome, and tissue necrosis.5

MANAGEMENT APPROACH

Aspiration of a fluid-filled mass is useful in both diagnosis and management of Morel-Lavallée lesions. Treatment includes watchful waiting; compression and pressure wraps; injection of a sclerosing agent (eg, doxycyline, alcohol); needle aspiration; percutaneous drainage with debridement, irrigation, and suction; and incision and evacuation.6

The approach to treatment depends on the stage of the lesion and whether an underlying fracture is present. Depending on the amount of blood and lymphatic products and the acuity of the collected fluid (hours to days post-trauma), aspiration with a large-bore needle (eg, 14 to 22 gauge) may or may not be successful.7 In general, traumatic serosanguinous fluid collections are less painful and resolve faster than well-formed coagulated hematomas.

Patients who have a large lesion, significant pain, or decreased range of motion should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon.

Our patient was managed conservatively, and his symptoms completely resolved in 2 months.

A 42-year-old man presented with a lump on the side of his left hip, which had developed after he fell on his hip while playing basketball about 2 weeks earlier. He was able to continue playing and finished the game. After the game he noticed a lump, which rapidly increased in size. Significant bruising developed afterwards, and the area was mildly painful. The lump did not interfere with his daily activities, but it was annoying.

THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Morel-Lavallée lesion is an uncommon condition resulting from shearing trauma and collection of fluid in the space between deep fatty tissue and superficial fascia.6 It is usually the result of severe trauma, as in a motor vehicle accident, but it can also result from sports-related trauma, as in our patient.6–8 Lateral hip, gluteal, and sacral regions are the most common locations for Morel-Lavallée lesions and are often associated with an underlying fracture.6,9

Morel-Lavallée lesions usually develop hours or days after trauma, although they may develop weeks or even months later.2 Symptoms include bulging, pain, and loss of cutaneous sensation over the affected area. Although ultrasonography can be used, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for diagnosis and staging.6,10 If there is concern for fracture, plain radiography should be performed.

Mellado and Bencardino classified Morel-Lavallée lesions into 6 types based on their morphology, presence or absence of a capsule, signal behavior on MRI, and enhancement pattern.10 The exact rate of infection in patients with Morel-Lavallée lesions is unknown; however, the risk of infection seems to be highest after surgical intervention or aspiration.5,6

Another potential complication is fluid reaccumulation, which most often occurs with large lesions (> 50 mL) and lesions with a fibrous capsule or pseudocapsule.5 Large lesions can compromise adjacent neurovascular structures, particularly in the extremities.5 Potential consequences include dermal necrosis, compartment syndrome, and tissue necrosis.5

MANAGEMENT APPROACH

Aspiration of a fluid-filled mass is useful in both diagnosis and management of Morel-Lavallée lesions. Treatment includes watchful waiting; compression and pressure wraps; injection of a sclerosing agent (eg, doxycyline, alcohol); needle aspiration; percutaneous drainage with debridement, irrigation, and suction; and incision and evacuation.6

The approach to treatment depends on the stage of the lesion and whether an underlying fracture is present. Depending on the amount of blood and lymphatic products and the acuity of the collected fluid (hours to days post-trauma), aspiration with a large-bore needle (eg, 14 to 22 gauge) may or may not be successful.7 In general, traumatic serosanguinous fluid collections are less painful and resolve faster than well-formed coagulated hematomas.

Patients who have a large lesion, significant pain, or decreased range of motion should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon.

Our patient was managed conservatively, and his symptoms completely resolved in 2 months.

- Ahmad Z, Tibrewal S, Waters G, Nolan J. Solitary amyloidoma related to THA. Orthopedics 2013; 36:e971–e973.

- Harris-Spinks C, Nabhan D, Khodaee M. Noniatrogenic septic olecranon bursitis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016; 15:33–37.

- Price MD, Busconi BD, McMillan S. Proximal femur fractures. In: Miller MD, Sanders TG, eds. Presentation, Imaging and Treatment of Common Musculoskeletal Conditions. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:365–376.

- Stanton MC, Maloney MD, Dehaven KE, Giordano BD. Acute traumatic tear of gluteus medius and minimus tendons in a patient without antecedant peritrochanteric hip pain. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2012; 3:84–88.

- Khodaee M, Deu RS, Mathern S, Bravman JT. Morel-Lavallée lesion in sports. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016; 15:417–422.

- Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, et al. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol 2014; 21:35–43.

- Khodaee M, Deu RS. Ankle Morel-Lavallée lesion in a recreational racquetball player. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2016. Epub ahead of print.

- Shmerling A, Bravman JT, Khodaee M. Morel-Lavallée lesion of the knee in a recreational frisbee player. Case Rep Orthop 2016; 2016:8723489.

- Miller J, Daggett J, Ambay R, Payne WG. Morel-Lavallée lesion. Eplasty 2014; 14:ic12.

- Mellado JM, Bencardino JT. Morel-Lavallée lesion: review with emphasis on MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2005; 13:775–782.

- Ahmad Z, Tibrewal S, Waters G, Nolan J. Solitary amyloidoma related to THA. Orthopedics 2013; 36:e971–e973.

- Harris-Spinks C, Nabhan D, Khodaee M. Noniatrogenic septic olecranon bursitis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016; 15:33–37.

- Price MD, Busconi BD, McMillan S. Proximal femur fractures. In: Miller MD, Sanders TG, eds. Presentation, Imaging and Treatment of Common Musculoskeletal Conditions. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2011:365–376.

- Stanton MC, Maloney MD, Dehaven KE, Giordano BD. Acute traumatic tear of gluteus medius and minimus tendons in a patient without antecedant peritrochanteric hip pain. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2012; 3:84–88.

- Khodaee M, Deu RS, Mathern S, Bravman JT. Morel-Lavallée lesion in sports. Curr Sports Med Rep 2016; 15:417–422.

- Bonilla-Yoon I, Masih S, Patel DB, et al. The Morel-Lavallée lesion: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, imaging features, and treatment options. Emerg Radiol 2014; 21:35–43.

- Khodaee M, Deu RS. Ankle Morel-Lavallée lesion in a recreational racquetball player. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2016. Epub ahead of print.

- Shmerling A, Bravman JT, Khodaee M. Morel-Lavallée lesion of the knee in a recreational frisbee player. Case Rep Orthop 2016; 2016:8723489.

- Miller J, Daggett J, Ambay R, Payne WG. Morel-Lavallée lesion. Eplasty 2014; 14:ic12.

- Mellado JM, Bencardino JT. Morel-Lavallée lesion: review with emphasis on MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2005; 13:775–782.