User login

Nail Irregularities Associated With Sézary Syndrome

Sézary syndrome (SS) is an advanced leukemic form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) that is characterized by generalized erythroderma and T-cell leukemia. Skin changes can include erythroderma, keratosis pilaris–like lesions, keratoderma, ectropion, alopecia, and nail changes.1 Nail changes in SS patients frequently are overlooked and underreported; they vary greatly from patient to patient, and their incidence has not been widely evaluated in the literature.

In this retrospective study, we reviewed medical records from a previously collected CTCL clinic database at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, Texas) and found nail abnormalities in 36 of 83 (43.4%) patients with a diagnosis of SS. Findings for 2 select cases are described in more detail; they were compared to prior case reports from the literature to establish a comprehensive list of nail irregularities that have been associated with SS.

Methods

We examined records from a previously collected CTCL clinic database at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. This database was part of an institutional review board–approved protocol to prospectively collect data from patients with CTCL. Our search yielded 83 patients with SS who were seen between 2007 and 2014.

Results

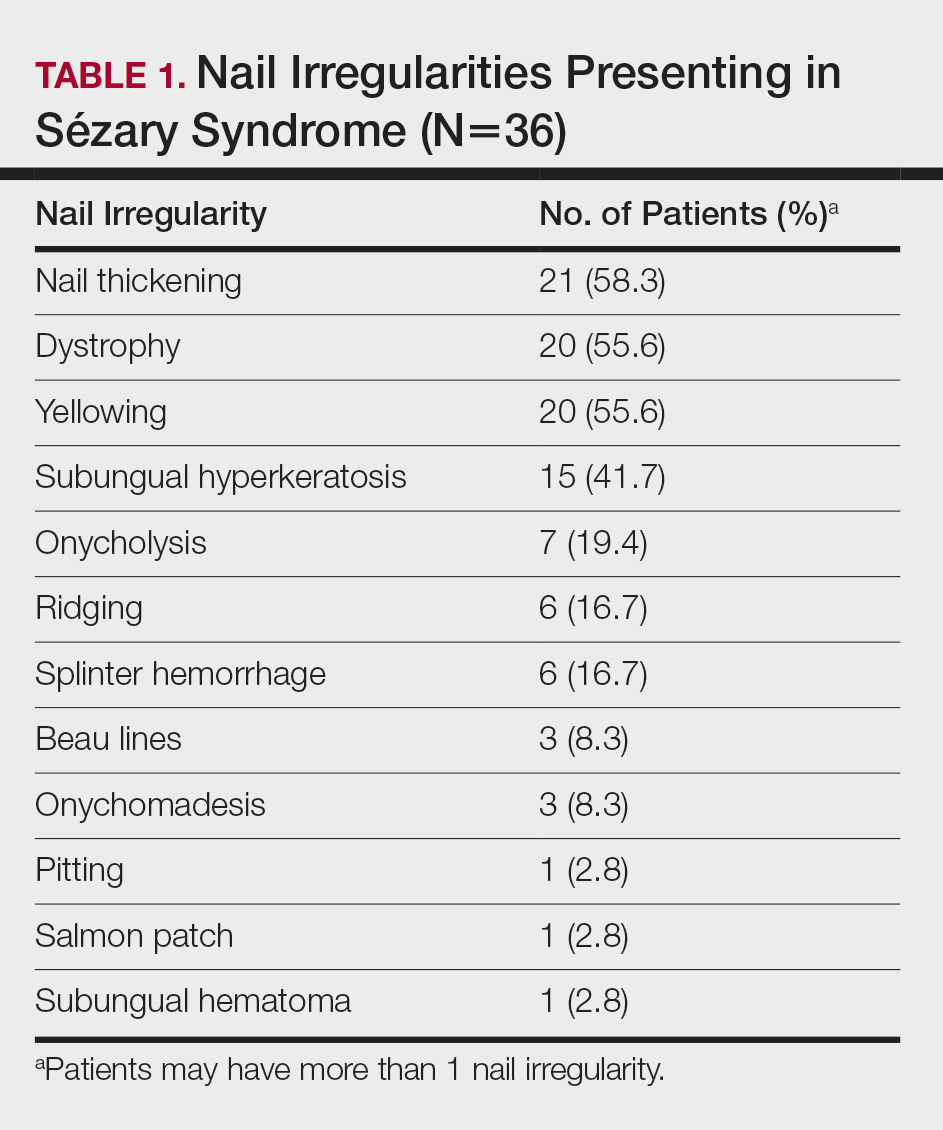

Of the 83 cases reviewed from the CTCL database, 36 (43.4%) SS patients reported at least 1 nail abnormality on the fingernails or toenails. Patients ranged in age from 59 to 85 years and included 27 (75%) men and 9 (25%) women. Nail irregularities noted on physical examination are summarized in Table 1. More than half of the patients presented with nail thickening (58.3% [21/36]), dystrophy (55.6% [20/36]), or yellowing (55.6% [20/36]) of 1 or more nails. Other findings included 15 (41.7%) patients with subungual hyperkeratosis, 3 (8.3%) with Beau lines, and 1 (2.8%) with multiple oil spots consistent with salmon patches. Five (13.9%) patients had only 1 reported nail irregularity, and 1 (2.8%) patient had 6 irregularities. The average number of nail abnormalities per patient was 2.88 (range, 1–6). We selected 2 patients with extensive nail findings who represent the spectrum of nail findings in patients with SS.

Patient 1

A 71-year-old white man presented with a papular rash of 30 years’ duration. The eruption first occurred on the soles of the feet but progressed to generalized erythroderma. He was found to be colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Over the next 9 months, the patient was diagnosed with SS at an outside institution and was treated with cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, gemcitabine, etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, cisplatin, topical steroids, and intravenous methotrexate with no apparent improvement. At presentation to our institution, physical examination revealed pruritus; alopecia; generalized lymphadenopathy; erythroderma; and irregular nail findings, including yellowing, thickened fingernails and toenails with subungual debris, and splinter hemorrhage (Figure 1). A thick plaque with perioral distribution as well as erosions on the face and feet were noted. The total body surface area (BSA) affected was 100% (patches, 91%; plaques, 9%).

At diagnosis at our institution, the patient’s white blood cell (WBC) count was 17,800/µL (reference range, 4000–11,000/µL), with 11% Sézary cells noted. Biopsy of a lymph node from the inguinal area indicated T-cell lymphoma with clonal T-cell receptor (TCR) β gene rearrangement. Biopsy of lesional skin in the right groin area showed an atypical T-cell lymphocytic infiltrate with a CD4:CD8 ratio of 2.9:1 and partial loss of CD7 expression, consistent with mycosis fungoides (MF)/SS stage IVA. At presentation to our institution, the WBC count was 12,700/µL with a neutrophil count of 47% (reference range, 42%–66%), lymphocyte count of 36% (reference range, 24%–44%), monocyte count of 4% (reference range, 2%–7%), platelet count of 427,000/µL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/µL), hemoglobin of 9.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), and lactate dehydrogenase of 733 U/L (reference range, 135–214 U/L). Lymphocytes were positive for CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD25, CD52, TCRα, TCRβ, and TCR VB17; partial for CD26; and negative for CD7, CD8, and CD57. At follow-up 1 month later, the CD4+CD26− T-cell population was 56%, which was consistent with SS T-cell lymphoma.

Skin scrapings from the generalized keratoderma on the patient’s feet were positive for fungal hyphae under potassium hydroxide examination. Nail clippings showed compact keratin with periodic acid–Schiff–positive small yeast forms admixed with bacterial organisms, consistent with onychomycosis. At our institution, the patient received extracorporeal photopheresis, whirlpool therapy (a type of hydrotherapy), steroid wet wraps, and intravenous vancomycin for methicillin-resistant S aureus. He also received bexarotene, levothyroxine sodium, and fenofibrate. After antibiotics and 2 sessions of photopheresis, the total BSA improved from 100% to 33%. The feet and nails were treated with ciclopirox gel and terbinafine, but neither the keratoderma nor the nails improved.

Patient 2

An 84-year-old white man with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia also was diagnosed with SS at an outside institution. One year later, he presented to our institution with mild pruritus and swelling of the lower left leg, which was diagnosed as deep vein thrombosis. There was bilateral scaling of the palms, with fissures present on the left palm. The fingernails showed dystrophy with Beau lines, and the toenails were dystrophic with onycholysis on the bilateral great toes (Figure 2). Patches were noted on most of the body, including the feet, with plaques limited to the hands; the total BSA affected was 80%. Flow cytometry showed an elevated Sézary cell count (CD4+CD26−) of 4700 cells/µL. Complete blood cell count with differential included a hemoglobin level of 11.4 g/dL, hematocrit level of 35.3% (reference range, 37%–47%), a platelet count of 217,000/µL, and a WBC count of 17,7

the bilateral great toes.

Comment

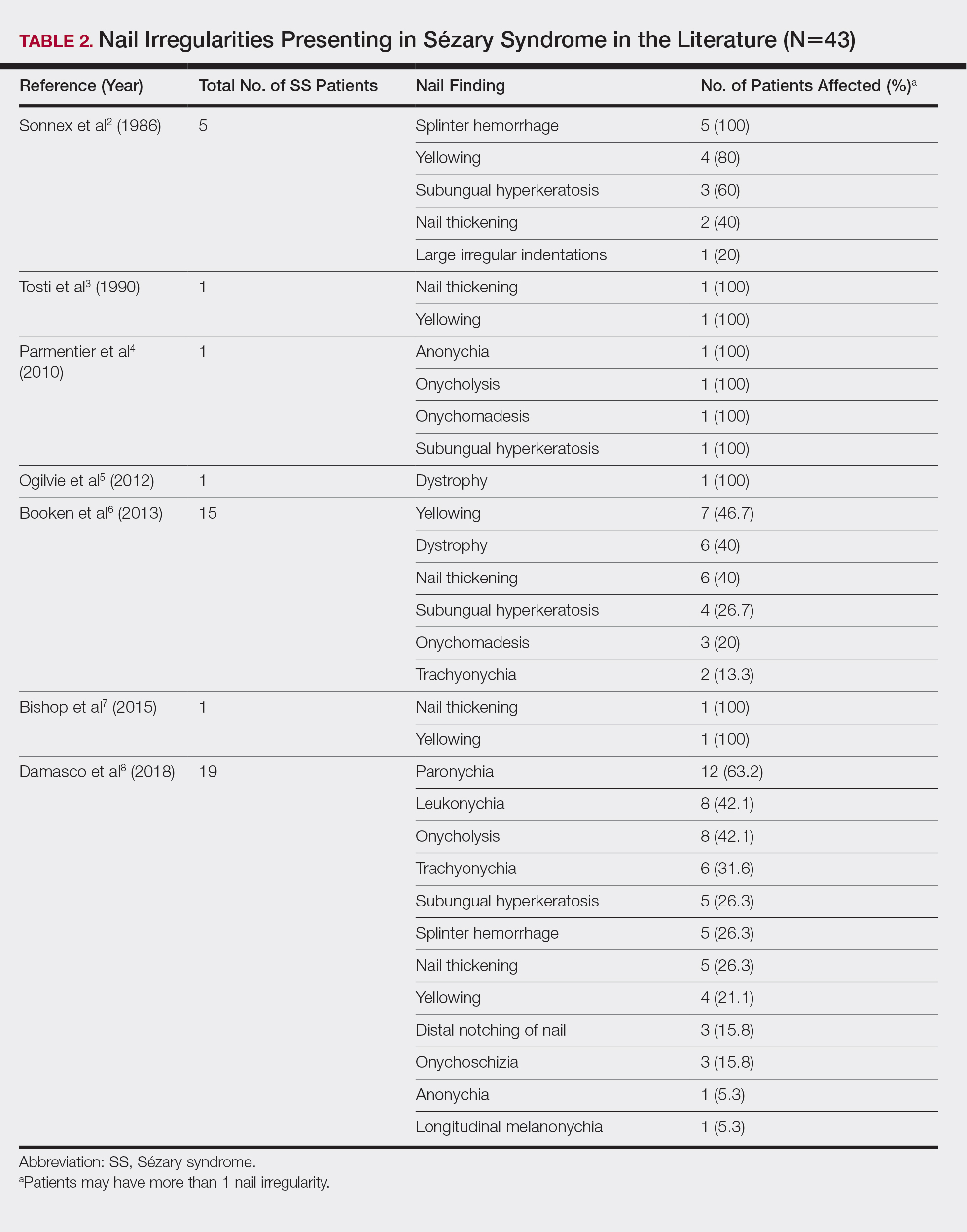

Nail changes are found in many cases of advanced-stage SS but rarely have been reported in the literature. A literature review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the search terms Sézary, nail, onychodystrophy, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and CTCL. All results were reviewed for original reported cases of SS with at least 1 reported nail finding. A total of 7 reports2-8 met these requirements with a total of 43 SS patients with reported nail findings, which are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Our findings are generally consistent with those previously described in the literature. Nail thickening, yellowing, subungual hyperkeratosis, dystrophy, and onycholysis are consistently some of the most common nail findings in patients with SS. In 2012, Martin and Duvic9 found that 52.9% (45/85) of SS patients with keratoderma on physical examination were positive for dermatophyte hyphae when skin scrapings were done under potassium hydroxide examination, a considerably greater incidence than in the general population (10%–20%). The nail changes seen in our SS patients were identical to those found in dermatophyte infections, including discoloration, subungual debris, nail thickening, onycholysis, and dystrophy.10 In patient 1, nail clippings were positive for onychomycosis, a common nail condition that is especially prevalent in older or immunocompromised patients.9,10

Interestingly, findings not observed in the literature included salmon patches and Beau lines. Beau lines are horizontal depressions in the nail plate and often are indicative of temporary interruption of nail growth, such as due to an underlying disease process, severe illness, and/or chemotherapy.11,12 In our review, patient 2 had clinical findings of Beau lines. Because the average time for fingernail regrowth is 3 to 6 months,13 it is reasonable to assume that physical findings associated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab chemotherapy treatment would no longer be demonstrated 11 months after completion of therapy. On the other hand, paronychia was frequently observed by Damasco et al8 (63.2% [12/19] of their cases), yet it was not found in our database or the other literature reports we reviewed. Perhaps these differences are due to differences in patient populations and/or available therapies, lack of documentation, or small sample size and limited reports in the literature.

A common question is: Are the nail irregularities caused by the physical symptoms of advanced CTCL or by the underlying disease process in response to the atypical T cells? Erythroderma has been speculated to cause many of the clinical findings of nail abnormalities found in CTCL patients.2,3 However, Fleming et al14 described an MF patient who experienced onychomadesis without erythroderma, which suggests that a different mechanism may cause these nail changes. The wide range of nail abnormalities in CTCL can cause problems with diagnosing the specific cause underlying the nail alteration.

To further complicate the issue, numerous therapies for CTCL also may cause nail changes, such as the previously described Beau lines. In 2010, Parmentier et al4 reported a patient with nail alterations that had been present for more than 1 year, with 9 of 10 fingernails demonstrating anonychia, onychomadesis, subungual distal hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis. In this case report, the authors were able to exclude phototherapy as the cause of onycholysis (visible separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and other clinical nail findings in the SS patient based on the onset of nail changes prior to beginning psoralen plus UVA therapy and complete sparing of 1 finger.4 The findings in our patient 1, who had no history of psoralen plus UVA therapy at the time the irregular nail findings presented, supports this observation. Total skin electron beam therapy for MF also has been reported to cause temporary nail stasis and thus must be taken into account when considering nail changes in patients with MF/SS.15

A nail matrix biopsy may provide clues to the definitive cause of the clinically observed nail changes; however, this procedure typically is not performed due to patient concerns of postoperative complications including pain and nail dystrophy.16 Histopathology features were similar in reported nail biopsies of 2 SS patients.3,4 Tosti et al3 reported that longitudinal biopsy showed a dense lymphocytic infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes with involuted nuclei and notable epidermotropism. Parmentier et al4 reported a longitudinal nail biopsy in an SS patient that presented with atypical lymphocytes, epidermotropism, and Pautrier microabscess formation. Immunostaining showed CD3 positivity within the distal nail matrix, nail bed, and hyponychium. One-third of the cells stained positive for CD4, while the majority stained positive for CD8. Most notably, the skin, nails, and blood showed identical clonal rearrangement of TCRγ.4 Nail matrix biopsies in MF patients rarely have been reported in the literature, but those that are available show similar features to those seen in SS patients. Harland et al17 summarized the findings of 4 case reports of CTCL patients that included nail biopsies by stating, “[a]ll histopathologic findings from nail biopsies showed a dense subepithelial infiltrate of lymphocytes with marked epitheliotropism.” These histopathologic abnormalities are akin to skin biopsies in MF patients, thus providing an essential link to the disease state of MF and the nail abnormalities found within SS patients.

Treatment of the nail problems found within SS is challenging due to limited research. Parmentier et al4 noted an SS patient who was treated with topical mechlorethamine applied directly to the nail. In this case, topical mechlorethamine was effective at treating onychomadesis, subungual distal hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis within 6 months.4 Another SS patient, who presented with thickening and yellowing of the nail, had reported a proximal nail plate that resolved after chemotherapy. The patient did not survive long enough to note complete improvement of the nail.3 In our study, patient 1 was treated with ciclopirox gel and terbinafine, which did not result in nail improvement. Nail treatments in SS patients have yet to show much improvement and thus need more research and focus in the literature.

Conclusion

Sézary syndrome is a rare CTCL that can present with clinical features that may be mistaken for other diseases. Nail abnormalities in SS patients may be related to fungal involvement, medical therapy, or the underlying disease process of SS. We report one of the largest populations of SS patients with specific reported nail abnormalities, thus expanding the possibilities of nail changes that accompany the disease. Continued research and studies involving SS can provide a better understanding of nail involvement and successful treatment of these clinical findings.

- Willemz e R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Sonnex TS, Dawber RP, Zachary CB, et al. The nails in adult type 1 pityriasis rubra pilaris. a comparison with Sézary syndrome and psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(5 pt 1):956-960.

- Tosti A, Fanti PA, Varotti C. Massive lymphomatous nail involvement in Sézary syndrome. Dermatologica. 1990;181:162-164.

- Parmentier L, Durr C, Vassella E, et al. Specific nail alterations in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: successful treatment with topical mechlorethamine. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1287-1291.

- Ogilvie C, Jackson R, Leach M, et al. Sézary syndrome: diagnosis and management. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2012;42:317-321.

- Booken N, Nicolay JP, Weiss C, et al. Cutaneous tumor cell load correlates with survival in patients with Sézary syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:67-79.

- Bishop BE, Wulkan A, Kerdel F, et al. Nail alterations in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a case series and review of nail manifestations. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:82-86.

- Damasco FM, Geskin L, Akilov OE. Onychodystrophy in Sézary syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:972-973.

- Martin SJ, Duvic M. Prevalence and treatment of palmoplantar keratoderma and tinea pedis in patients with Sézary syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1195-1198.

- Mayo TT, Cantrell W. Putting onychomycosis under the microscope. Nurse Pract. 2014;39:8-11.

- Singh M, Kaur S. Chemotherapy-induced multiple Beau’s lines. Int J Dermatol. 1986;25:590-591.

- Tully AS, Trayes KP, Studdiford JS. Evaluation of nail abnormalities. Am Family Physician. 2012;85:779-787.

- Shirwaikar AA, Thomas T, Shirwaikar A, et al. Treatment of onychomycosis: an update. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2008;70:710-714.

- Fleming CJ, Hunt MJ, Barnetson RS. Mycosis fungoides with onychomadesis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1012-1013.

- Jones GW, Kacinski BM, Wilson LD, et al. Total skin electron radiation in the management of mycosis fungoides: consensus of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Cutaneous Lymphoma Project Group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:364-370.

- Haneke E. Advanced nail surgery. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2011;4:167-175.

- Harland E, Dalle S, Balme B, et al. Ungueotropic T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1071-1073.

Sézary syndrome (SS) is an advanced leukemic form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) that is characterized by generalized erythroderma and T-cell leukemia. Skin changes can include erythroderma, keratosis pilaris–like lesions, keratoderma, ectropion, alopecia, and nail changes.1 Nail changes in SS patients frequently are overlooked and underreported; they vary greatly from patient to patient, and their incidence has not been widely evaluated in the literature.

In this retrospective study, we reviewed medical records from a previously collected CTCL clinic database at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, Texas) and found nail abnormalities in 36 of 83 (43.4%) patients with a diagnosis of SS. Findings for 2 select cases are described in more detail; they were compared to prior case reports from the literature to establish a comprehensive list of nail irregularities that have been associated with SS.

Methods

We examined records from a previously collected CTCL clinic database at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. This database was part of an institutional review board–approved protocol to prospectively collect data from patients with CTCL. Our search yielded 83 patients with SS who were seen between 2007 and 2014.

Results

Of the 83 cases reviewed from the CTCL database, 36 (43.4%) SS patients reported at least 1 nail abnormality on the fingernails or toenails. Patients ranged in age from 59 to 85 years and included 27 (75%) men and 9 (25%) women. Nail irregularities noted on physical examination are summarized in Table 1. More than half of the patients presented with nail thickening (58.3% [21/36]), dystrophy (55.6% [20/36]), or yellowing (55.6% [20/36]) of 1 or more nails. Other findings included 15 (41.7%) patients with subungual hyperkeratosis, 3 (8.3%) with Beau lines, and 1 (2.8%) with multiple oil spots consistent with salmon patches. Five (13.9%) patients had only 1 reported nail irregularity, and 1 (2.8%) patient had 6 irregularities. The average number of nail abnormalities per patient was 2.88 (range, 1–6). We selected 2 patients with extensive nail findings who represent the spectrum of nail findings in patients with SS.

Patient 1

A 71-year-old white man presented with a papular rash of 30 years’ duration. The eruption first occurred on the soles of the feet but progressed to generalized erythroderma. He was found to be colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Over the next 9 months, the patient was diagnosed with SS at an outside institution and was treated with cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, gemcitabine, etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, cisplatin, topical steroids, and intravenous methotrexate with no apparent improvement. At presentation to our institution, physical examination revealed pruritus; alopecia; generalized lymphadenopathy; erythroderma; and irregular nail findings, including yellowing, thickened fingernails and toenails with subungual debris, and splinter hemorrhage (Figure 1). A thick plaque with perioral distribution as well as erosions on the face and feet were noted. The total body surface area (BSA) affected was 100% (patches, 91%; plaques, 9%).

At diagnosis at our institution, the patient’s white blood cell (WBC) count was 17,800/µL (reference range, 4000–11,000/µL), with 11% Sézary cells noted. Biopsy of a lymph node from the inguinal area indicated T-cell lymphoma with clonal T-cell receptor (TCR) β gene rearrangement. Biopsy of lesional skin in the right groin area showed an atypical T-cell lymphocytic infiltrate with a CD4:CD8 ratio of 2.9:1 and partial loss of CD7 expression, consistent with mycosis fungoides (MF)/SS stage IVA. At presentation to our institution, the WBC count was 12,700/µL with a neutrophil count of 47% (reference range, 42%–66%), lymphocyte count of 36% (reference range, 24%–44%), monocyte count of 4% (reference range, 2%–7%), platelet count of 427,000/µL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/µL), hemoglobin of 9.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), and lactate dehydrogenase of 733 U/L (reference range, 135–214 U/L). Lymphocytes were positive for CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD25, CD52, TCRα, TCRβ, and TCR VB17; partial for CD26; and negative for CD7, CD8, and CD57. At follow-up 1 month later, the CD4+CD26− T-cell population was 56%, which was consistent with SS T-cell lymphoma.

Skin scrapings from the generalized keratoderma on the patient’s feet were positive for fungal hyphae under potassium hydroxide examination. Nail clippings showed compact keratin with periodic acid–Schiff–positive small yeast forms admixed with bacterial organisms, consistent with onychomycosis. At our institution, the patient received extracorporeal photopheresis, whirlpool therapy (a type of hydrotherapy), steroid wet wraps, and intravenous vancomycin for methicillin-resistant S aureus. He also received bexarotene, levothyroxine sodium, and fenofibrate. After antibiotics and 2 sessions of photopheresis, the total BSA improved from 100% to 33%. The feet and nails were treated with ciclopirox gel and terbinafine, but neither the keratoderma nor the nails improved.

Patient 2

An 84-year-old white man with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia also was diagnosed with SS at an outside institution. One year later, he presented to our institution with mild pruritus and swelling of the lower left leg, which was diagnosed as deep vein thrombosis. There was bilateral scaling of the palms, with fissures present on the left palm. The fingernails showed dystrophy with Beau lines, and the toenails were dystrophic with onycholysis on the bilateral great toes (Figure 2). Patches were noted on most of the body, including the feet, with plaques limited to the hands; the total BSA affected was 80%. Flow cytometry showed an elevated Sézary cell count (CD4+CD26−) of 4700 cells/µL. Complete blood cell count with differential included a hemoglobin level of 11.4 g/dL, hematocrit level of 35.3% (reference range, 37%–47%), a platelet count of 217,000/µL, and a WBC count of 17,7

the bilateral great toes.

Comment

Nail changes are found in many cases of advanced-stage SS but rarely have been reported in the literature. A literature review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the search terms Sézary, nail, onychodystrophy, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and CTCL. All results were reviewed for original reported cases of SS with at least 1 reported nail finding. A total of 7 reports2-8 met these requirements with a total of 43 SS patients with reported nail findings, which are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Our findings are generally consistent with those previously described in the literature. Nail thickening, yellowing, subungual hyperkeratosis, dystrophy, and onycholysis are consistently some of the most common nail findings in patients with SS. In 2012, Martin and Duvic9 found that 52.9% (45/85) of SS patients with keratoderma on physical examination were positive for dermatophyte hyphae when skin scrapings were done under potassium hydroxide examination, a considerably greater incidence than in the general population (10%–20%). The nail changes seen in our SS patients were identical to those found in dermatophyte infections, including discoloration, subungual debris, nail thickening, onycholysis, and dystrophy.10 In patient 1, nail clippings were positive for onychomycosis, a common nail condition that is especially prevalent in older or immunocompromised patients.9,10

Interestingly, findings not observed in the literature included salmon patches and Beau lines. Beau lines are horizontal depressions in the nail plate and often are indicative of temporary interruption of nail growth, such as due to an underlying disease process, severe illness, and/or chemotherapy.11,12 In our review, patient 2 had clinical findings of Beau lines. Because the average time for fingernail regrowth is 3 to 6 months,13 it is reasonable to assume that physical findings associated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab chemotherapy treatment would no longer be demonstrated 11 months after completion of therapy. On the other hand, paronychia was frequently observed by Damasco et al8 (63.2% [12/19] of their cases), yet it was not found in our database or the other literature reports we reviewed. Perhaps these differences are due to differences in patient populations and/or available therapies, lack of documentation, or small sample size and limited reports in the literature.

A common question is: Are the nail irregularities caused by the physical symptoms of advanced CTCL or by the underlying disease process in response to the atypical T cells? Erythroderma has been speculated to cause many of the clinical findings of nail abnormalities found in CTCL patients.2,3 However, Fleming et al14 described an MF patient who experienced onychomadesis without erythroderma, which suggests that a different mechanism may cause these nail changes. The wide range of nail abnormalities in CTCL can cause problems with diagnosing the specific cause underlying the nail alteration.

To further complicate the issue, numerous therapies for CTCL also may cause nail changes, such as the previously described Beau lines. In 2010, Parmentier et al4 reported a patient with nail alterations that had been present for more than 1 year, with 9 of 10 fingernails demonstrating anonychia, onychomadesis, subungual distal hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis. In this case report, the authors were able to exclude phototherapy as the cause of onycholysis (visible separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and other clinical nail findings in the SS patient based on the onset of nail changes prior to beginning psoralen plus UVA therapy and complete sparing of 1 finger.4 The findings in our patient 1, who had no history of psoralen plus UVA therapy at the time the irregular nail findings presented, supports this observation. Total skin electron beam therapy for MF also has been reported to cause temporary nail stasis and thus must be taken into account when considering nail changes in patients with MF/SS.15

A nail matrix biopsy may provide clues to the definitive cause of the clinically observed nail changes; however, this procedure typically is not performed due to patient concerns of postoperative complications including pain and nail dystrophy.16 Histopathology features were similar in reported nail biopsies of 2 SS patients.3,4 Tosti et al3 reported that longitudinal biopsy showed a dense lymphocytic infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes with involuted nuclei and notable epidermotropism. Parmentier et al4 reported a longitudinal nail biopsy in an SS patient that presented with atypical lymphocytes, epidermotropism, and Pautrier microabscess formation. Immunostaining showed CD3 positivity within the distal nail matrix, nail bed, and hyponychium. One-third of the cells stained positive for CD4, while the majority stained positive for CD8. Most notably, the skin, nails, and blood showed identical clonal rearrangement of TCRγ.4 Nail matrix biopsies in MF patients rarely have been reported in the literature, but those that are available show similar features to those seen in SS patients. Harland et al17 summarized the findings of 4 case reports of CTCL patients that included nail biopsies by stating, “[a]ll histopathologic findings from nail biopsies showed a dense subepithelial infiltrate of lymphocytes with marked epitheliotropism.” These histopathologic abnormalities are akin to skin biopsies in MF patients, thus providing an essential link to the disease state of MF and the nail abnormalities found within SS patients.

Treatment of the nail problems found within SS is challenging due to limited research. Parmentier et al4 noted an SS patient who was treated with topical mechlorethamine applied directly to the nail. In this case, topical mechlorethamine was effective at treating onychomadesis, subungual distal hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis within 6 months.4 Another SS patient, who presented with thickening and yellowing of the nail, had reported a proximal nail plate that resolved after chemotherapy. The patient did not survive long enough to note complete improvement of the nail.3 In our study, patient 1 was treated with ciclopirox gel and terbinafine, which did not result in nail improvement. Nail treatments in SS patients have yet to show much improvement and thus need more research and focus in the literature.

Conclusion

Sézary syndrome is a rare CTCL that can present with clinical features that may be mistaken for other diseases. Nail abnormalities in SS patients may be related to fungal involvement, medical therapy, or the underlying disease process of SS. We report one of the largest populations of SS patients with specific reported nail abnormalities, thus expanding the possibilities of nail changes that accompany the disease. Continued research and studies involving SS can provide a better understanding of nail involvement and successful treatment of these clinical findings.

Sézary syndrome (SS) is an advanced leukemic form of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) that is characterized by generalized erythroderma and T-cell leukemia. Skin changes can include erythroderma, keratosis pilaris–like lesions, keratoderma, ectropion, alopecia, and nail changes.1 Nail changes in SS patients frequently are overlooked and underreported; they vary greatly from patient to patient, and their incidence has not been widely evaluated in the literature.

In this retrospective study, we reviewed medical records from a previously collected CTCL clinic database at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, Texas) and found nail abnormalities in 36 of 83 (43.4%) patients with a diagnosis of SS. Findings for 2 select cases are described in more detail; they were compared to prior case reports from the literature to establish a comprehensive list of nail irregularities that have been associated with SS.

Methods

We examined records from a previously collected CTCL clinic database at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. This database was part of an institutional review board–approved protocol to prospectively collect data from patients with CTCL. Our search yielded 83 patients with SS who were seen between 2007 and 2014.

Results

Of the 83 cases reviewed from the CTCL database, 36 (43.4%) SS patients reported at least 1 nail abnormality on the fingernails or toenails. Patients ranged in age from 59 to 85 years and included 27 (75%) men and 9 (25%) women. Nail irregularities noted on physical examination are summarized in Table 1. More than half of the patients presented with nail thickening (58.3% [21/36]), dystrophy (55.6% [20/36]), or yellowing (55.6% [20/36]) of 1 or more nails. Other findings included 15 (41.7%) patients with subungual hyperkeratosis, 3 (8.3%) with Beau lines, and 1 (2.8%) with multiple oil spots consistent with salmon patches. Five (13.9%) patients had only 1 reported nail irregularity, and 1 (2.8%) patient had 6 irregularities. The average number of nail abnormalities per patient was 2.88 (range, 1–6). We selected 2 patients with extensive nail findings who represent the spectrum of nail findings in patients with SS.

Patient 1

A 71-year-old white man presented with a papular rash of 30 years’ duration. The eruption first occurred on the soles of the feet but progressed to generalized erythroderma. He was found to be colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Over the next 9 months, the patient was diagnosed with SS at an outside institution and was treated with cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, gemcitabine, etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, cisplatin, topical steroids, and intravenous methotrexate with no apparent improvement. At presentation to our institution, physical examination revealed pruritus; alopecia; generalized lymphadenopathy; erythroderma; and irregular nail findings, including yellowing, thickened fingernails and toenails with subungual debris, and splinter hemorrhage (Figure 1). A thick plaque with perioral distribution as well as erosions on the face and feet were noted. The total body surface area (BSA) affected was 100% (patches, 91%; plaques, 9%).

At diagnosis at our institution, the patient’s white blood cell (WBC) count was 17,800/µL (reference range, 4000–11,000/µL), with 11% Sézary cells noted. Biopsy of a lymph node from the inguinal area indicated T-cell lymphoma with clonal T-cell receptor (TCR) β gene rearrangement. Biopsy of lesional skin in the right groin area showed an atypical T-cell lymphocytic infiltrate with a CD4:CD8 ratio of 2.9:1 and partial loss of CD7 expression, consistent with mycosis fungoides (MF)/SS stage IVA. At presentation to our institution, the WBC count was 12,700/µL with a neutrophil count of 47% (reference range, 42%–66%), lymphocyte count of 36% (reference range, 24%–44%), monocyte count of 4% (reference range, 2%–7%), platelet count of 427,000/µL (reference range, 150,000–350,000/µL), hemoglobin of 9.9 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL), and lactate dehydrogenase of 733 U/L (reference range, 135–214 U/L). Lymphocytes were positive for CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD25, CD52, TCRα, TCRβ, and TCR VB17; partial for CD26; and negative for CD7, CD8, and CD57. At follow-up 1 month later, the CD4+CD26− T-cell population was 56%, which was consistent with SS T-cell lymphoma.

Skin scrapings from the generalized keratoderma on the patient’s feet were positive for fungal hyphae under potassium hydroxide examination. Nail clippings showed compact keratin with periodic acid–Schiff–positive small yeast forms admixed with bacterial organisms, consistent with onychomycosis. At our institution, the patient received extracorporeal photopheresis, whirlpool therapy (a type of hydrotherapy), steroid wet wraps, and intravenous vancomycin for methicillin-resistant S aureus. He also received bexarotene, levothyroxine sodium, and fenofibrate. After antibiotics and 2 sessions of photopheresis, the total BSA improved from 100% to 33%. The feet and nails were treated with ciclopirox gel and terbinafine, but neither the keratoderma nor the nails improved.

Patient 2

An 84-year-old white man with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia also was diagnosed with SS at an outside institution. One year later, he presented to our institution with mild pruritus and swelling of the lower left leg, which was diagnosed as deep vein thrombosis. There was bilateral scaling of the palms, with fissures present on the left palm. The fingernails showed dystrophy with Beau lines, and the toenails were dystrophic with onycholysis on the bilateral great toes (Figure 2). Patches were noted on most of the body, including the feet, with plaques limited to the hands; the total BSA affected was 80%. Flow cytometry showed an elevated Sézary cell count (CD4+CD26−) of 4700 cells/µL. Complete blood cell count with differential included a hemoglobin level of 11.4 g/dL, hematocrit level of 35.3% (reference range, 37%–47%), a platelet count of 217,000/µL, and a WBC count of 17,7

the bilateral great toes.

Comment

Nail changes are found in many cases of advanced-stage SS but rarely have been reported in the literature. A literature review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the search terms Sézary, nail, onychodystrophy, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and CTCL. All results were reviewed for original reported cases of SS with at least 1 reported nail finding. A total of 7 reports2-8 met these requirements with a total of 43 SS patients with reported nail findings, which are summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Our findings are generally consistent with those previously described in the literature. Nail thickening, yellowing, subungual hyperkeratosis, dystrophy, and onycholysis are consistently some of the most common nail findings in patients with SS. In 2012, Martin and Duvic9 found that 52.9% (45/85) of SS patients with keratoderma on physical examination were positive for dermatophyte hyphae when skin scrapings were done under potassium hydroxide examination, a considerably greater incidence than in the general population (10%–20%). The nail changes seen in our SS patients were identical to those found in dermatophyte infections, including discoloration, subungual debris, nail thickening, onycholysis, and dystrophy.10 In patient 1, nail clippings were positive for onychomycosis, a common nail condition that is especially prevalent in older or immunocompromised patients.9,10

Interestingly, findings not observed in the literature included salmon patches and Beau lines. Beau lines are horizontal depressions in the nail plate and often are indicative of temporary interruption of nail growth, such as due to an underlying disease process, severe illness, and/or chemotherapy.11,12 In our review, patient 2 had clinical findings of Beau lines. Because the average time for fingernail regrowth is 3 to 6 months,13 it is reasonable to assume that physical findings associated with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab chemotherapy treatment would no longer be demonstrated 11 months after completion of therapy. On the other hand, paronychia was frequently observed by Damasco et al8 (63.2% [12/19] of their cases), yet it was not found in our database or the other literature reports we reviewed. Perhaps these differences are due to differences in patient populations and/or available therapies, lack of documentation, or small sample size and limited reports in the literature.

A common question is: Are the nail irregularities caused by the physical symptoms of advanced CTCL or by the underlying disease process in response to the atypical T cells? Erythroderma has been speculated to cause many of the clinical findings of nail abnormalities found in CTCL patients.2,3 However, Fleming et al14 described an MF patient who experienced onychomadesis without erythroderma, which suggests that a different mechanism may cause these nail changes. The wide range of nail abnormalities in CTCL can cause problems with diagnosing the specific cause underlying the nail alteration.

To further complicate the issue, numerous therapies for CTCL also may cause nail changes, such as the previously described Beau lines. In 2010, Parmentier et al4 reported a patient with nail alterations that had been present for more than 1 year, with 9 of 10 fingernails demonstrating anonychia, onychomadesis, subungual distal hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis. In this case report, the authors were able to exclude phototherapy as the cause of onycholysis (visible separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and other clinical nail findings in the SS patient based on the onset of nail changes prior to beginning psoralen plus UVA therapy and complete sparing of 1 finger.4 The findings in our patient 1, who had no history of psoralen plus UVA therapy at the time the irregular nail findings presented, supports this observation. Total skin electron beam therapy for MF also has been reported to cause temporary nail stasis and thus must be taken into account when considering nail changes in patients with MF/SS.15

A nail matrix biopsy may provide clues to the definitive cause of the clinically observed nail changes; however, this procedure typically is not performed due to patient concerns of postoperative complications including pain and nail dystrophy.16 Histopathology features were similar in reported nail biopsies of 2 SS patients.3,4 Tosti et al3 reported that longitudinal biopsy showed a dense lymphocytic infiltrate of atypical lymphocytes with involuted nuclei and notable epidermotropism. Parmentier et al4 reported a longitudinal nail biopsy in an SS patient that presented with atypical lymphocytes, epidermotropism, and Pautrier microabscess formation. Immunostaining showed CD3 positivity within the distal nail matrix, nail bed, and hyponychium. One-third of the cells stained positive for CD4, while the majority stained positive for CD8. Most notably, the skin, nails, and blood showed identical clonal rearrangement of TCRγ.4 Nail matrix biopsies in MF patients rarely have been reported in the literature, but those that are available show similar features to those seen in SS patients. Harland et al17 summarized the findings of 4 case reports of CTCL patients that included nail biopsies by stating, “[a]ll histopathologic findings from nail biopsies showed a dense subepithelial infiltrate of lymphocytes with marked epitheliotropism.” These histopathologic abnormalities are akin to skin biopsies in MF patients, thus providing an essential link to the disease state of MF and the nail abnormalities found within SS patients.

Treatment of the nail problems found within SS is challenging due to limited research. Parmentier et al4 noted an SS patient who was treated with topical mechlorethamine applied directly to the nail. In this case, topical mechlorethamine was effective at treating onychomadesis, subungual distal hyperkeratosis, and onycholysis within 6 months.4 Another SS patient, who presented with thickening and yellowing of the nail, had reported a proximal nail plate that resolved after chemotherapy. The patient did not survive long enough to note complete improvement of the nail.3 In our study, patient 1 was treated with ciclopirox gel and terbinafine, which did not result in nail improvement. Nail treatments in SS patients have yet to show much improvement and thus need more research and focus in the literature.

Conclusion

Sézary syndrome is a rare CTCL that can present with clinical features that may be mistaken for other diseases. Nail abnormalities in SS patients may be related to fungal involvement, medical therapy, or the underlying disease process of SS. We report one of the largest populations of SS patients with specific reported nail abnormalities, thus expanding the possibilities of nail changes that accompany the disease. Continued research and studies involving SS can provide a better understanding of nail involvement and successful treatment of these clinical findings.

- Willemz e R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Sonnex TS, Dawber RP, Zachary CB, et al. The nails in adult type 1 pityriasis rubra pilaris. a comparison with Sézary syndrome and psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(5 pt 1):956-960.

- Tosti A, Fanti PA, Varotti C. Massive lymphomatous nail involvement in Sézary syndrome. Dermatologica. 1990;181:162-164.

- Parmentier L, Durr C, Vassella E, et al. Specific nail alterations in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: successful treatment with topical mechlorethamine. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1287-1291.

- Ogilvie C, Jackson R, Leach M, et al. Sézary syndrome: diagnosis and management. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2012;42:317-321.

- Booken N, Nicolay JP, Weiss C, et al. Cutaneous tumor cell load correlates with survival in patients with Sézary syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:67-79.

- Bishop BE, Wulkan A, Kerdel F, et al. Nail alterations in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a case series and review of nail manifestations. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:82-86.

- Damasco FM, Geskin L, Akilov OE. Onychodystrophy in Sézary syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:972-973.

- Martin SJ, Duvic M. Prevalence and treatment of palmoplantar keratoderma and tinea pedis in patients with Sézary syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1195-1198.

- Mayo TT, Cantrell W. Putting onychomycosis under the microscope. Nurse Pract. 2014;39:8-11.

- Singh M, Kaur S. Chemotherapy-induced multiple Beau’s lines. Int J Dermatol. 1986;25:590-591.

- Tully AS, Trayes KP, Studdiford JS. Evaluation of nail abnormalities. Am Family Physician. 2012;85:779-787.

- Shirwaikar AA, Thomas T, Shirwaikar A, et al. Treatment of onychomycosis: an update. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2008;70:710-714.

- Fleming CJ, Hunt MJ, Barnetson RS. Mycosis fungoides with onychomadesis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1012-1013.

- Jones GW, Kacinski BM, Wilson LD, et al. Total skin electron radiation in the management of mycosis fungoides: consensus of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Cutaneous Lymphoma Project Group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:364-370.

- Haneke E. Advanced nail surgery. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2011;4:167-175.

- Harland E, Dalle S, Balme B, et al. Ungueotropic T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1071-1073.

- Willemz e R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

- Sonnex TS, Dawber RP, Zachary CB, et al. The nails in adult type 1 pityriasis rubra pilaris. a comparison with Sézary syndrome and psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15(5 pt 1):956-960.

- Tosti A, Fanti PA, Varotti C. Massive lymphomatous nail involvement in Sézary syndrome. Dermatologica. 1990;181:162-164.

- Parmentier L, Durr C, Vassella E, et al. Specific nail alterations in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: successful treatment with topical mechlorethamine. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1287-1291.

- Ogilvie C, Jackson R, Leach M, et al. Sézary syndrome: diagnosis and management. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2012;42:317-321.

- Booken N, Nicolay JP, Weiss C, et al. Cutaneous tumor cell load correlates with survival in patients with Sézary syndrome. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:67-79.

- Bishop BE, Wulkan A, Kerdel F, et al. Nail alterations in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a case series and review of nail manifestations. Skin Appendage Disord. 2015;1:82-86.

- Damasco FM, Geskin L, Akilov OE. Onychodystrophy in Sézary syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:972-973.

- Martin SJ, Duvic M. Prevalence and treatment of palmoplantar keratoderma and tinea pedis in patients with Sézary syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1195-1198.

- Mayo TT, Cantrell W. Putting onychomycosis under the microscope. Nurse Pract. 2014;39:8-11.

- Singh M, Kaur S. Chemotherapy-induced multiple Beau’s lines. Int J Dermatol. 1986;25:590-591.

- Tully AS, Trayes KP, Studdiford JS. Evaluation of nail abnormalities. Am Family Physician. 2012;85:779-787.

- Shirwaikar AA, Thomas T, Shirwaikar A, et al. Treatment of onychomycosis: an update. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2008;70:710-714.

- Fleming CJ, Hunt MJ, Barnetson RS. Mycosis fungoides with onychomadesis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:1012-1013.

- Jones GW, Kacinski BM, Wilson LD, et al. Total skin electron radiation in the management of mycosis fungoides: consensus of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Cutaneous Lymphoma Project Group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:364-370.

- Haneke E. Advanced nail surgery. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2011;4:167-175.

- Harland E, Dalle S, Balme B, et al. Ungueotropic T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1071-1073.

Practice Points

- Nail changes are frequently observed in patients with Sézary syndrome.

- Nail changes in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma may result from the disease process or physical symptoms of advanced disease, or they may present secondary to treatment.

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma in a Patient With Celiac Disease

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common form of a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas known as cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Celiac disease (CD) is associated with increased risk for development of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma and other intraintestinal and extraintestinal non-Hodgkin lymphomas, but a firm association between CD and MF has not been established.1 The first and second cases of concomitant MF and CD were reported in 1985 and 2009 by Coulson and Sanderson2 and Moreira et al,3 respectively. Two other reports of celiac-associated dermatitis herpetiformis and MF exist.4,5 We report a patient with a unique constellation of MF, CD, and Sjögren syndrome (SS).

A 54-year-old woman presented with a worsening nonpruritic, slightly tender, eczematous patch on the back of 19 years’ duration. She had a history of SS diagnosed by salivary gland biopsy. She also had a diagnosis of CD confirmed with positive antigliadin IgA antibodies, with a dramatic improvement in symptoms on a gluten-free diet (GFD) after having abdominal pain and diarrhea for many years. She had no evidence of dermatitis herpetiformis. Recently, more red-brown areas of confluent light pink erythema without clear-cut borders had appeared on the axillae, trunk, and thigh (Figure). The patient also noted new lesions and more erythema of the patches when not adhering to a GFD. A biopsy specimen from the left side of the lateral trunk revealed a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with irregular nuclear contours displaying epidermotropism with a few Pautrier microabscesses. Immunohistochemistry showed strong CD3 and CD4 positivity with loss of CD7 and scattered CD8 staining. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed no aberrant cell populations. The patient was diagnosed with MF stage IB and treated with topical corticosteroids and natural light with improvement.

It has been hypothesized that early MF is an autoimmune process caused by dysregulation of a lymphocytic reaction against chronic exogenous or endogenous antigens.4,5 The association of MF with CD supports the possibility of lymphocytic stimulation by a persistent antigen (ie, gluten) in the gastrointestinal tract. Porter et al4 suggested that in susceptible individuals, the resulting clonal T cells may migrate into the epidermis, causing MF. This theory also is supported by the finding that adherence to a GFD leads to decreased risk for malignancy and morbidity.6 In our patient, the chronic autoimmune stimulation in SS could be a factor in the pathogenesis of MF. Additionally, SS, CD, and MF are all strongly associated with increased incidence of specific but different HLA class II antigens. Mycosis fungoides is associated with HLA-DR5 and DQB1*03 alleles, CD with HLA-DQ2 and DQ8, and SS with HLA-DR15 and DR3. We do not know the HLA type of our patient, but she likely possessed multiple alleles, leading to the unique aggregation of diseases.

Furthermore, studies have shown that lymphocytes in CD patients display impaired regulatory T-cell function, causing increased incidence of autoimmune diseases and malignancy.7,8 By this theory, the occurrence of MF in patients is facilitated by the inability of CD lymphocytes to control the abnormal T-cell proliferation in the skin. Interestingly, the finding of SS in our patient supports the possibility of impaired regulatory T-cell function.

Although the occurrence of both MF and CD in our patient could be coincidental, the possibility of correlation must be considered as more cases are documented.

- Catassi C, Fabiani E, Corrao G, et al; Italian Working Group on Coeliac Disease and Non-Hodgkin’s-Lymphoma. Risk of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in celiac disease. JAMA. 2002;287:1413-1419.

- Coulson IH, Sanderson KV. T-cell lymphoma presenting as tumour d’emblée mycosis fungoides associated with coeliac disease. J R Soc Med. 1985;78(suppl 11):23-24.

- Moreira AI, Menezes N, Varela P, et al. Primary cutaneous peripheral T cell lymphoma and celiac disease [in Portuguese]. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2009;55:253-256.

- Porter WM, Dawe SA, Bunker CB. Dermatitis herpetiformis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:304-305.

- Sun G, Berthelot C, Duvic M. A second case of dermatitis herpetiformis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:506-507.

- Holmes GK, Prior P, Lane MR, et al. Malignancy in coeliac disease—effect of a gluten free diet. Gut. 1989;30:333-338.

- Granzotto M, dal Bo S, Quaglia S, et al. Regulatory T-cell function is impaired in celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1513-1519.

- Roychoudhuri R, Hirahara K, Mousavi K, et al. BACH2 represses effector programs to stabilize T(reg)-mediated immune homeostasis [published online June 2, 2013]. Nature. 2013;498:506-510.

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common form of a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas known as cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Celiac disease (CD) is associated with increased risk for development of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma and other intraintestinal and extraintestinal non-Hodgkin lymphomas, but a firm association between CD and MF has not been established.1 The first and second cases of concomitant MF and CD were reported in 1985 and 2009 by Coulson and Sanderson2 and Moreira et al,3 respectively. Two other reports of celiac-associated dermatitis herpetiformis and MF exist.4,5 We report a patient with a unique constellation of MF, CD, and Sjögren syndrome (SS).

A 54-year-old woman presented with a worsening nonpruritic, slightly tender, eczematous patch on the back of 19 years’ duration. She had a history of SS diagnosed by salivary gland biopsy. She also had a diagnosis of CD confirmed with positive antigliadin IgA antibodies, with a dramatic improvement in symptoms on a gluten-free diet (GFD) after having abdominal pain and diarrhea for many years. She had no evidence of dermatitis herpetiformis. Recently, more red-brown areas of confluent light pink erythema without clear-cut borders had appeared on the axillae, trunk, and thigh (Figure). The patient also noted new lesions and more erythema of the patches when not adhering to a GFD. A biopsy specimen from the left side of the lateral trunk revealed a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with irregular nuclear contours displaying epidermotropism with a few Pautrier microabscesses. Immunohistochemistry showed strong CD3 and CD4 positivity with loss of CD7 and scattered CD8 staining. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed no aberrant cell populations. The patient was diagnosed with MF stage IB and treated with topical corticosteroids and natural light with improvement.

It has been hypothesized that early MF is an autoimmune process caused by dysregulation of a lymphocytic reaction against chronic exogenous or endogenous antigens.4,5 The association of MF with CD supports the possibility of lymphocytic stimulation by a persistent antigen (ie, gluten) in the gastrointestinal tract. Porter et al4 suggested that in susceptible individuals, the resulting clonal T cells may migrate into the epidermis, causing MF. This theory also is supported by the finding that adherence to a GFD leads to decreased risk for malignancy and morbidity.6 In our patient, the chronic autoimmune stimulation in SS could be a factor in the pathogenesis of MF. Additionally, SS, CD, and MF are all strongly associated with increased incidence of specific but different HLA class II antigens. Mycosis fungoides is associated with HLA-DR5 and DQB1*03 alleles, CD with HLA-DQ2 and DQ8, and SS with HLA-DR15 and DR3. We do not know the HLA type of our patient, but she likely possessed multiple alleles, leading to the unique aggregation of diseases.

Furthermore, studies have shown that lymphocytes in CD patients display impaired regulatory T-cell function, causing increased incidence of autoimmune diseases and malignancy.7,8 By this theory, the occurrence of MF in patients is facilitated by the inability of CD lymphocytes to control the abnormal T-cell proliferation in the skin. Interestingly, the finding of SS in our patient supports the possibility of impaired regulatory T-cell function.

Although the occurrence of both MF and CD in our patient could be coincidental, the possibility of correlation must be considered as more cases are documented.

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common form of a heterogeneous group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas known as cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. Celiac disease (CD) is associated with increased risk for development of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma and other intraintestinal and extraintestinal non-Hodgkin lymphomas, but a firm association between CD and MF has not been established.1 The first and second cases of concomitant MF and CD were reported in 1985 and 2009 by Coulson and Sanderson2 and Moreira et al,3 respectively. Two other reports of celiac-associated dermatitis herpetiformis and MF exist.4,5 We report a patient with a unique constellation of MF, CD, and Sjögren syndrome (SS).

A 54-year-old woman presented with a worsening nonpruritic, slightly tender, eczematous patch on the back of 19 years’ duration. She had a history of SS diagnosed by salivary gland biopsy. She also had a diagnosis of CD confirmed with positive antigliadin IgA antibodies, with a dramatic improvement in symptoms on a gluten-free diet (GFD) after having abdominal pain and diarrhea for many years. She had no evidence of dermatitis herpetiformis. Recently, more red-brown areas of confluent light pink erythema without clear-cut borders had appeared on the axillae, trunk, and thigh (Figure). The patient also noted new lesions and more erythema of the patches when not adhering to a GFD. A biopsy specimen from the left side of the lateral trunk revealed a bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate with irregular nuclear contours displaying epidermotropism with a few Pautrier microabscesses. Immunohistochemistry showed strong CD3 and CD4 positivity with loss of CD7 and scattered CD8 staining. Peripheral blood flow cytometry showed no aberrant cell populations. The patient was diagnosed with MF stage IB and treated with topical corticosteroids and natural light with improvement.

It has been hypothesized that early MF is an autoimmune process caused by dysregulation of a lymphocytic reaction against chronic exogenous or endogenous antigens.4,5 The association of MF with CD supports the possibility of lymphocytic stimulation by a persistent antigen (ie, gluten) in the gastrointestinal tract. Porter et al4 suggested that in susceptible individuals, the resulting clonal T cells may migrate into the epidermis, causing MF. This theory also is supported by the finding that adherence to a GFD leads to decreased risk for malignancy and morbidity.6 In our patient, the chronic autoimmune stimulation in SS could be a factor in the pathogenesis of MF. Additionally, SS, CD, and MF are all strongly associated with increased incidence of specific but different HLA class II antigens. Mycosis fungoides is associated with HLA-DR5 and DQB1*03 alleles, CD with HLA-DQ2 and DQ8, and SS with HLA-DR15 and DR3. We do not know the HLA type of our patient, but she likely possessed multiple alleles, leading to the unique aggregation of diseases.

Furthermore, studies have shown that lymphocytes in CD patients display impaired regulatory T-cell function, causing increased incidence of autoimmune diseases and malignancy.7,8 By this theory, the occurrence of MF in patients is facilitated by the inability of CD lymphocytes to control the abnormal T-cell proliferation in the skin. Interestingly, the finding of SS in our patient supports the possibility of impaired regulatory T-cell function.

Although the occurrence of both MF and CD in our patient could be coincidental, the possibility of correlation must be considered as more cases are documented.

- Catassi C, Fabiani E, Corrao G, et al; Italian Working Group on Coeliac Disease and Non-Hodgkin’s-Lymphoma. Risk of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in celiac disease. JAMA. 2002;287:1413-1419.

- Coulson IH, Sanderson KV. T-cell lymphoma presenting as tumour d’emblée mycosis fungoides associated with coeliac disease. J R Soc Med. 1985;78(suppl 11):23-24.

- Moreira AI, Menezes N, Varela P, et al. Primary cutaneous peripheral T cell lymphoma and celiac disease [in Portuguese]. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2009;55:253-256.

- Porter WM, Dawe SA, Bunker CB. Dermatitis herpetiformis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:304-305.

- Sun G, Berthelot C, Duvic M. A second case of dermatitis herpetiformis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:506-507.

- Holmes GK, Prior P, Lane MR, et al. Malignancy in coeliac disease—effect of a gluten free diet. Gut. 1989;30:333-338.

- Granzotto M, dal Bo S, Quaglia S, et al. Regulatory T-cell function is impaired in celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1513-1519.

- Roychoudhuri R, Hirahara K, Mousavi K, et al. BACH2 represses effector programs to stabilize T(reg)-mediated immune homeostasis [published online June 2, 2013]. Nature. 2013;498:506-510.

- Catassi C, Fabiani E, Corrao G, et al; Italian Working Group on Coeliac Disease and Non-Hodgkin’s-Lymphoma. Risk of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in celiac disease. JAMA. 2002;287:1413-1419.

- Coulson IH, Sanderson KV. T-cell lymphoma presenting as tumour d’emblée mycosis fungoides associated with coeliac disease. J R Soc Med. 1985;78(suppl 11):23-24.

- Moreira AI, Menezes N, Varela P, et al. Primary cutaneous peripheral T cell lymphoma and celiac disease [in Portuguese]. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2009;55:253-256.

- Porter WM, Dawe SA, Bunker CB. Dermatitis herpetiformis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:304-305.

- Sun G, Berthelot C, Duvic M. A second case of dermatitis herpetiformis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:506-507.

- Holmes GK, Prior P, Lane MR, et al. Malignancy in coeliac disease—effect of a gluten free diet. Gut. 1989;30:333-338.

- Granzotto M, dal Bo S, Quaglia S, et al. Regulatory T-cell function is impaired in celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1513-1519.

- Roychoudhuri R, Hirahara K, Mousavi K, et al. BACH2 represses effector programs to stabilize T(reg)-mediated immune homeostasis [published online June 2, 2013]. Nature. 2013;498:506-510.

Practice Points

- Mycosis fungoides, the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, is an entity for which the pathogenesis is largely unknown.

- Our case and other cases of celiac disease and mycosis fungoides seem to support the immunologic hypothesis of lymphocytic stimulation by a persistent antigen.