User login

Highlights from the 2018 Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Scientific Meeting

PART 1

- Leading best gynecologic surgical care into the next decade

- Optimal surgical management of stage 3 and 4 pelvic organ prolapse

- Patient experience: It’s not about satisfaction

Andrew P. Cassidenti, MD

Chief, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Kern Medical,

Bakersfield, California

Amanda White, MD

Assistant Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Vivian Aguilar, MD

Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Associate Chair, Clinical Integration and Operations

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Patrick Culligan, MD

Director, Urogynecology and The Center for Female Pelvic Health

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Sarah Huber, MD

Fellow, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA

Chief, Gynecology, St. Luke’s University Health Network

Medical Director, The Institute for Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Allentown, Pennsylvania

Jessica B. Ton, MD

AAGL Fellow, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery

St. Luke’s University Health Network

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

James I. Merlino, MD

President and Chief Medical Officer of Advisory and Strategic Consulting

Press Ganey Associates

Cleveland, Ohio

Amy A. Merlino, MD

Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Enterprise Chief Informatics Officer

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

PART 2

- Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

- What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Rosanne M. Kho, MD

Head, Section of Benign Gynecology

Women’s Health Institute

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Mauricio S. Abrão, MD

Associate Professor and

Director, Endometriosis Division

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

São Paulo University Medical School

São Paulo, Brazil

Alicia Scribner, MD, MPH

Director, Ob/Gyn Simulation Curriculum

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Instructor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Christine Vaccaro, DO

Medical Director, Andersen Simulation Center

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Assistant Professor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland

PART 1

- Leading best gynecologic surgical care into the next decade

- Optimal surgical management of stage 3 and 4 pelvic organ prolapse

- Patient experience: It’s not about satisfaction

Andrew P. Cassidenti, MD

Chief, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Kern Medical,

Bakersfield, California

Amanda White, MD

Assistant Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Vivian Aguilar, MD

Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Associate Chair, Clinical Integration and Operations

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Patrick Culligan, MD

Director, Urogynecology and The Center for Female Pelvic Health

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Sarah Huber, MD

Fellow, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA

Chief, Gynecology, St. Luke’s University Health Network

Medical Director, The Institute for Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Allentown, Pennsylvania

Jessica B. Ton, MD

AAGL Fellow, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery

St. Luke’s University Health Network

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

James I. Merlino, MD

President and Chief Medical Officer of Advisory and Strategic Consulting

Press Ganey Associates

Cleveland, Ohio

Amy A. Merlino, MD

Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Enterprise Chief Informatics Officer

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

PART 2

- Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

- What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Rosanne M. Kho, MD

Head, Section of Benign Gynecology

Women’s Health Institute

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Mauricio S. Abrão, MD

Associate Professor and

Director, Endometriosis Division

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

São Paulo University Medical School

São Paulo, Brazil

Alicia Scribner, MD, MPH

Director, Ob/Gyn Simulation Curriculum

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Instructor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Christine Vaccaro, DO

Medical Director, Andersen Simulation Center

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Assistant Professor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland

PART 1

- Leading best gynecologic surgical care into the next decade

- Optimal surgical management of stage 3 and 4 pelvic organ prolapse

- Patient experience: It’s not about satisfaction

Andrew P. Cassidenti, MD

Chief, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Kern Medical,

Bakersfield, California

Amanda White, MD

Assistant Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Vivian Aguilar, MD

Assistant Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Rebecca G. Rogers, MD

Professor, Department of Women’s Health

Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Associate Chair, Clinical Integration and Operations

Dell Medical School, University of Texas

Austin, Texas

Patrick Culligan, MD

Director, Urogynecology and The Center for Female Pelvic Health

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Sarah Huber, MD

Fellow, Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Department of Urology

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center

New York, New York

Vincent R. Lucente, MD, MBA

Chief, Gynecology, St. Luke’s University Health Network

Medical Director, The Institute for Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery

Allentown, Pennsylvania

Jessica B. Ton, MD

AAGL Fellow, Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery

St. Luke’s University Health Network

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

James I. Merlino, MD

President and Chief Medical Officer of Advisory and Strategic Consulting

Press Ganey Associates

Cleveland, Ohio

Amy A. Merlino, MD

Maternal Fetal Medicine Specialist

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Enterprise Chief Informatics Officer

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

PART 2

- Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

- What’s new in simulation training for hysterectomy

Rosanne M. Kho, MD

Head, Section of Benign Gynecology

Women’s Health Institute

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Mauricio S. Abrão, MD

Associate Professor and

Director, Endometriosis Division

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

São Paulo University Medical School

São Paulo, Brazil

Alicia Scribner, MD, MPH

Director, Ob/Gyn Simulation Curriculum

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Instructor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Christine Vaccaro, DO

Medical Director, Andersen Simulation Center

Madigan Army Medical Center

Tacoma, Washington

Clinical Assistant Professor

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

University of Washington, Seattle

Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences

Bethesda, Maryland

Deep infiltrating endometriosis: Evaluation and management

Endometriosis affects up to 10% of women of reproductive age or, conservatively, about 6.5 million women in the United States.1,2 There are 3 types of endometriosis—superficial, ovarian, and deep—and in the past each of these was assumed to have a distinct pathogenesis.3 Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) is the presence of one or more endometriotic nodules deeper than 5 mm. In a study at a large tertiary-care center, 40% of patients with endometriosis had deep disease.4 DIE is associated with more severe pain and infertility.5 In patients with endometriosis, diagnosis is commonly made 7 to 9 years after the initial pelvic pain presentation.6 For these reasons, well-directed history taking and proper evaluation and treatment should be pursued to relieve pain and optimize outcomes.

CASE Young woman with intensifying pelvic pain

Mary is a 26-year-old social worker who presents to her ObGyn with symptoms of worsening pain during as well as outside her periods. What additional information would you want to obtain from Mary, given her chief symptom of pain?

Investigate the type of pain

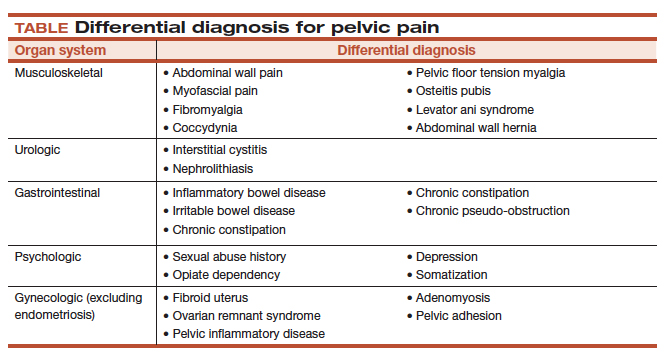

It is important to ask the patient about her menstrual and sexual history, her thoughts regarding near- and long-term fertility, and the type and severity of her pain symptoms. The 5 pain symptoms specific to pelvic pain are dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dysuria, dyschezia, and noncyclic pelvic pain. A visual analog scale (VAS) for pain as well as pelvic pain questionnaires can be used to guide evaluation options and monitor treatment outcomes. In addition, it is of paramount importance to understand the differential diagnoses that can present as pelvic pain (TABLE).

CASE Continued: Mary’s history

Mary reports that she always has had painful periods and that she was started on oral contraceptive pills for pain control and regulation of her periods soon after the onset of menses, when she was 12 years old. In college, she was prescribed oral contraceptive pills for contraception. Recently engaged, she is interested in becoming pregnant in 3 years.

A year ago, Mary discontinued the pills because of their adverse effects. Now she has severe pain during (VAS score, 8/10) and outside (VAS score, 7) her monthly periods. Because of this pain, she has taken time off from work twice within the past 6 months. She has pain during intercourse (VAS score, 7) and some pain with bowel movements during her menses (VAS score, 4). Pelvic examination reveals a normal-sized uterus and adnexa as well as a tender nodule in the rectovaginal septum.

What diagnostic tests and imaging would you obtain?

Imaging’s role in diagnosis

At many advanced centers for endometriosis, DIE is successfully diagnosed with specific magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) protocols. In a recent review, MRI’s pooled sensitivity and specificity for rectosigmoid endometriosis were 92% and 96%, respectively.7 Choice of imaging for DIE depends on the skills and experience of the clinicians at each center. At a large referral center in São Paulo, Brazil, TVUS with bowel preparation had better sensitivity and specificity for deep retrocervical and rectosigmoid disease compared with MRI and digital pelvic examination.8 In addition, at a center in the United States, we found that proficiency in performing TVUS for DIE was achieved after 70 to 75 cases, and the exam took an average of only 20 minutes.9

Despite recent advances in imaging, most gynecologic societies still hold that endometriosis is to be definitively diagnosed with histologic confirmation from tissue biopsies during surgery. Although surgery remains the diagnostic gold standard, it does not mean that all patients with pelvic pain should undergo diagnostic laparoscopy with tissue biopsies.

The combination of compelling clinical signs, symptoms, and imaging findings (such as absence of findings for ovarian and deep endometriosis) can be used to make a presumptive nonsurgical (that is, clinical) diagnosis of endometriosis. Major societies recommend empiric medical therapy (for example, combination oral contraceptives) for the pain associated with superficial endometriosis.10,11 When there is no response to treatment, or when a patient declines or has contraindications to medical therapy, diagnostic laparoscopy with excision of endometriosis should be considered.

CASE Continued: Diagnosis

Mary undergoes TVUS with bowel preparation, which reveals a normal uterus and adnexa and the presence of 2 lesions, a 2×1.5-cm retrocervical lesion and a 1.8×2-cm rectosigmoid lesion 9 cm above the anal verge. The rectosigmoid lesion involves the external muscularis and compromises 30% of the bowel circumference.

How would you manage the bowel DIE?

Read about management options and individualized care.

Management options: Factor in the variables

DIE can involve the ureters and bladder, the retrocervical and rectovaginal spaces, the appendix, and the bowel. Lesions can be single or multifocal. Although our institutions’ imaging with MRI and TVUS is highly accurate, we additionally recommend the use of colonoscopy (with directed biopsies if appropriate) to evaluate patients who present with rectal bleeding, large endometriotic rectal nodules, or have a family history of bowel cancer.

While many studies have found that surgical resection of DIE improves pain and quality of life, surgery can have significant complications.12 Observation is adequate for asymptomatic patients with DIE. Medical treatment may be offered to patients with mild pain (there is no evidence of a reduction in lesion size with medical therapy). In cases of surgical treatment, we encourage the involvement of a multidisciplinary surgical team to reduce complications and optimize outcomes.

Patients with DIE, significant pain (VAS score, >7), and multiple failed in vitro fertilization treatments are candidates for surgery. When bowel endometriosis is noted on imaging, factors such as size, depth, number of lesions, circumferential involvement, and distance from the anal verge are all used to determine the surgical approach. Rectosigmoid lesions smaller than 3 cm can be treated more conservatively—for example, with shaving or anterior resection with manual repair using disk staplers. Segmental resection generally is indicated for rectosigmoid lesions larger than 3 cm, involvement deeper than the submucosal layer, multiple lesions, circumferential involvement of more than 40%, and the presence of obstructed bowel symptoms.13,14

In patients with DIE who present with both infertility and pain, antimüllerian hormone level and TVUS follicular count are used to evaluate ovarian reserve. As surgical treatment may further reduce ovarian reserve in patients with DIE and infertility, we counsel them regarding assisted reproductive technology options before surgery.

CASE Resolved

After thorough discussion, Mary opts to try a different combination oral contraceptive pill formulation. The pills improve her pain symptoms significantly (VAS score, 4), and she decides to forgo surgery. She will be followed up closely on an outpatient basis with serial TVUS imaging.

Individualize management based on patient parameters

Imaging has been used for the nonsurgical diagnosis of DIE for many years, and this practice increasingly is being accepted and adopted. A presumptive nonsurgical diagnosis of endometriosis can be made based on the clinical signs and symptoms obtained from a thorough history and physical examination, in addition to the absence of imaging findings for ovarian and deep endometriosis.

According to guidelines from major ObGyn societies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, empiric medical therapy (including combination oral contraceptives, progesterone-containing formulations, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists) can be considered for patients with presumed endometriosis presenting with pain.15

When surgery is chosen, the surgeon must obtain crucial information on the characteristics of the lesion(s) and involve a multidisciplinary team to achieve the best outcomes for the patient.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789-1799.

- Buck Louis GM, Hediger ML, Peterson CM, et al; ENDO Study Working Group. Incidence of endometriosis by study population and diagnostic method: the ENDO study. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):360-365.

- Nisolle M, Donnez J. Peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and adenomyotic nodules of the rectovaginal septum are three different entities. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(4):585-596.

- Bellelis P, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Gonzales M, Baracat EC, Abrao MS. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of pelvic endometriosis--a case series. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2010;56(4):467-471.

- Fauconnier A, Chapron C. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: epidemiological evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(6):595-606.

- Greene R, Stratton P, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Sinaii N. Diagnostic experience among 4,334 women reporting surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(1):32-39.

- Bazot M, Daraï E. Diagnosis of deep endometriosis: clinical examination, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and other techniques. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):886-894.

- Abrão MS, Gonçalves MO, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Chamie LP, Blasbalg R. Comparison between clinical examination, transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(12):3092-3097.

- Young SW, Dahiya N, Patel MD, et al. Initial accuracy of and learning curve for transvaginal ultrasound with bowel preparation for deep endometriosis in a US tertiary care center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(7):1170-1176.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400-412.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 114: Management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):223-236.

- de Paula Andres M, Borrelli GM, Kho RM, Abrão MS. The current management of deep endometriosis: a systematic review. Minerva Ginecol. 2017;69(6):587-596.

- Abrão MS, Podgaec S, Dias JA Jr, Averbach M, Silva LF, Marino de Carvalho F. Endometriosis lesions that compromise the rectum deeper than the inner muscularis layer have more than 40% of the circumference of the rectum affected by the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(3):280-285.

- Abrão MS, Petraglia F, Falcone T, Keckstein J, Osuga Y, Chapron C. Deep endometriosis infiltrating the recto-sigmoid: critical factors to consider before management. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(3):329-339.

- Kho RM, Andres MP, Borrelli GM, Neto JS, Zanluchi A, Abrao MS. Surgical treatment of different types of endometriosis: comparison of major society guidelines and preferred clinical algorithms [published online ahead of print]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn2018.01.020.

Endometriosis affects up to 10% of women of reproductive age or, conservatively, about 6.5 million women in the United States.1,2 There are 3 types of endometriosis—superficial, ovarian, and deep—and in the past each of these was assumed to have a distinct pathogenesis.3 Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) is the presence of one or more endometriotic nodules deeper than 5 mm. In a study at a large tertiary-care center, 40% of patients with endometriosis had deep disease.4 DIE is associated with more severe pain and infertility.5 In patients with endometriosis, diagnosis is commonly made 7 to 9 years after the initial pelvic pain presentation.6 For these reasons, well-directed history taking and proper evaluation and treatment should be pursued to relieve pain and optimize outcomes.

CASE Young woman with intensifying pelvic pain

Mary is a 26-year-old social worker who presents to her ObGyn with symptoms of worsening pain during as well as outside her periods. What additional information would you want to obtain from Mary, given her chief symptom of pain?

Investigate the type of pain

It is important to ask the patient about her menstrual and sexual history, her thoughts regarding near- and long-term fertility, and the type and severity of her pain symptoms. The 5 pain symptoms specific to pelvic pain are dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dysuria, dyschezia, and noncyclic pelvic pain. A visual analog scale (VAS) for pain as well as pelvic pain questionnaires can be used to guide evaluation options and monitor treatment outcomes. In addition, it is of paramount importance to understand the differential diagnoses that can present as pelvic pain (TABLE).

CASE Continued: Mary’s history

Mary reports that she always has had painful periods and that she was started on oral contraceptive pills for pain control and regulation of her periods soon after the onset of menses, when she was 12 years old. In college, she was prescribed oral contraceptive pills for contraception. Recently engaged, she is interested in becoming pregnant in 3 years.

A year ago, Mary discontinued the pills because of their adverse effects. Now she has severe pain during (VAS score, 8/10) and outside (VAS score, 7) her monthly periods. Because of this pain, she has taken time off from work twice within the past 6 months. She has pain during intercourse (VAS score, 7) and some pain with bowel movements during her menses (VAS score, 4). Pelvic examination reveals a normal-sized uterus and adnexa as well as a tender nodule in the rectovaginal septum.

What diagnostic tests and imaging would you obtain?

Imaging’s role in diagnosis

At many advanced centers for endometriosis, DIE is successfully diagnosed with specific magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) protocols. In a recent review, MRI’s pooled sensitivity and specificity for rectosigmoid endometriosis were 92% and 96%, respectively.7 Choice of imaging for DIE depends on the skills and experience of the clinicians at each center. At a large referral center in São Paulo, Brazil, TVUS with bowel preparation had better sensitivity and specificity for deep retrocervical and rectosigmoid disease compared with MRI and digital pelvic examination.8 In addition, at a center in the United States, we found that proficiency in performing TVUS for DIE was achieved after 70 to 75 cases, and the exam took an average of only 20 minutes.9

Despite recent advances in imaging, most gynecologic societies still hold that endometriosis is to be definitively diagnosed with histologic confirmation from tissue biopsies during surgery. Although surgery remains the diagnostic gold standard, it does not mean that all patients with pelvic pain should undergo diagnostic laparoscopy with tissue biopsies.

The combination of compelling clinical signs, symptoms, and imaging findings (such as absence of findings for ovarian and deep endometriosis) can be used to make a presumptive nonsurgical (that is, clinical) diagnosis of endometriosis. Major societies recommend empiric medical therapy (for example, combination oral contraceptives) for the pain associated with superficial endometriosis.10,11 When there is no response to treatment, or when a patient declines or has contraindications to medical therapy, diagnostic laparoscopy with excision of endometriosis should be considered.

CASE Continued: Diagnosis

Mary undergoes TVUS with bowel preparation, which reveals a normal uterus and adnexa and the presence of 2 lesions, a 2×1.5-cm retrocervical lesion and a 1.8×2-cm rectosigmoid lesion 9 cm above the anal verge. The rectosigmoid lesion involves the external muscularis and compromises 30% of the bowel circumference.

How would you manage the bowel DIE?

Read about management options and individualized care.

Management options: Factor in the variables

DIE can involve the ureters and bladder, the retrocervical and rectovaginal spaces, the appendix, and the bowel. Lesions can be single or multifocal. Although our institutions’ imaging with MRI and TVUS is highly accurate, we additionally recommend the use of colonoscopy (with directed biopsies if appropriate) to evaluate patients who present with rectal bleeding, large endometriotic rectal nodules, or have a family history of bowel cancer.

While many studies have found that surgical resection of DIE improves pain and quality of life, surgery can have significant complications.12 Observation is adequate for asymptomatic patients with DIE. Medical treatment may be offered to patients with mild pain (there is no evidence of a reduction in lesion size with medical therapy). In cases of surgical treatment, we encourage the involvement of a multidisciplinary surgical team to reduce complications and optimize outcomes.

Patients with DIE, significant pain (VAS score, >7), and multiple failed in vitro fertilization treatments are candidates for surgery. When bowel endometriosis is noted on imaging, factors such as size, depth, number of lesions, circumferential involvement, and distance from the anal verge are all used to determine the surgical approach. Rectosigmoid lesions smaller than 3 cm can be treated more conservatively—for example, with shaving or anterior resection with manual repair using disk staplers. Segmental resection generally is indicated for rectosigmoid lesions larger than 3 cm, involvement deeper than the submucosal layer, multiple lesions, circumferential involvement of more than 40%, and the presence of obstructed bowel symptoms.13,14

In patients with DIE who present with both infertility and pain, antimüllerian hormone level and TVUS follicular count are used to evaluate ovarian reserve. As surgical treatment may further reduce ovarian reserve in patients with DIE and infertility, we counsel them regarding assisted reproductive technology options before surgery.

CASE Resolved

After thorough discussion, Mary opts to try a different combination oral contraceptive pill formulation. The pills improve her pain symptoms significantly (VAS score, 4), and she decides to forgo surgery. She will be followed up closely on an outpatient basis with serial TVUS imaging.

Individualize management based on patient parameters

Imaging has been used for the nonsurgical diagnosis of DIE for many years, and this practice increasingly is being accepted and adopted. A presumptive nonsurgical diagnosis of endometriosis can be made based on the clinical signs and symptoms obtained from a thorough history and physical examination, in addition to the absence of imaging findings for ovarian and deep endometriosis.

According to guidelines from major ObGyn societies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, empiric medical therapy (including combination oral contraceptives, progesterone-containing formulations, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists) can be considered for patients with presumed endometriosis presenting with pain.15

When surgery is chosen, the surgeon must obtain crucial information on the characteristics of the lesion(s) and involve a multidisciplinary team to achieve the best outcomes for the patient.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Endometriosis affects up to 10% of women of reproductive age or, conservatively, about 6.5 million women in the United States.1,2 There are 3 types of endometriosis—superficial, ovarian, and deep—and in the past each of these was assumed to have a distinct pathogenesis.3 Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) is the presence of one or more endometriotic nodules deeper than 5 mm. In a study at a large tertiary-care center, 40% of patients with endometriosis had deep disease.4 DIE is associated with more severe pain and infertility.5 In patients with endometriosis, diagnosis is commonly made 7 to 9 years after the initial pelvic pain presentation.6 For these reasons, well-directed history taking and proper evaluation and treatment should be pursued to relieve pain and optimize outcomes.

CASE Young woman with intensifying pelvic pain

Mary is a 26-year-old social worker who presents to her ObGyn with symptoms of worsening pain during as well as outside her periods. What additional information would you want to obtain from Mary, given her chief symptom of pain?

Investigate the type of pain

It is important to ask the patient about her menstrual and sexual history, her thoughts regarding near- and long-term fertility, and the type and severity of her pain symptoms. The 5 pain symptoms specific to pelvic pain are dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dysuria, dyschezia, and noncyclic pelvic pain. A visual analog scale (VAS) for pain as well as pelvic pain questionnaires can be used to guide evaluation options and monitor treatment outcomes. In addition, it is of paramount importance to understand the differential diagnoses that can present as pelvic pain (TABLE).

CASE Continued: Mary’s history

Mary reports that she always has had painful periods and that she was started on oral contraceptive pills for pain control and regulation of her periods soon after the onset of menses, when she was 12 years old. In college, she was prescribed oral contraceptive pills for contraception. Recently engaged, she is interested in becoming pregnant in 3 years.

A year ago, Mary discontinued the pills because of their adverse effects. Now she has severe pain during (VAS score, 8/10) and outside (VAS score, 7) her monthly periods. Because of this pain, she has taken time off from work twice within the past 6 months. She has pain during intercourse (VAS score, 7) and some pain with bowel movements during her menses (VAS score, 4). Pelvic examination reveals a normal-sized uterus and adnexa as well as a tender nodule in the rectovaginal septum.

What diagnostic tests and imaging would you obtain?

Imaging’s role in diagnosis

At many advanced centers for endometriosis, DIE is successfully diagnosed with specific magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) protocols. In a recent review, MRI’s pooled sensitivity and specificity for rectosigmoid endometriosis were 92% and 96%, respectively.7 Choice of imaging for DIE depends on the skills and experience of the clinicians at each center. At a large referral center in São Paulo, Brazil, TVUS with bowel preparation had better sensitivity and specificity for deep retrocervical and rectosigmoid disease compared with MRI and digital pelvic examination.8 In addition, at a center in the United States, we found that proficiency in performing TVUS for DIE was achieved after 70 to 75 cases, and the exam took an average of only 20 minutes.9

Despite recent advances in imaging, most gynecologic societies still hold that endometriosis is to be definitively diagnosed with histologic confirmation from tissue biopsies during surgery. Although surgery remains the diagnostic gold standard, it does not mean that all patients with pelvic pain should undergo diagnostic laparoscopy with tissue biopsies.

The combination of compelling clinical signs, symptoms, and imaging findings (such as absence of findings for ovarian and deep endometriosis) can be used to make a presumptive nonsurgical (that is, clinical) diagnosis of endometriosis. Major societies recommend empiric medical therapy (for example, combination oral contraceptives) for the pain associated with superficial endometriosis.10,11 When there is no response to treatment, or when a patient declines or has contraindications to medical therapy, diagnostic laparoscopy with excision of endometriosis should be considered.

CASE Continued: Diagnosis

Mary undergoes TVUS with bowel preparation, which reveals a normal uterus and adnexa and the presence of 2 lesions, a 2×1.5-cm retrocervical lesion and a 1.8×2-cm rectosigmoid lesion 9 cm above the anal verge. The rectosigmoid lesion involves the external muscularis and compromises 30% of the bowel circumference.

How would you manage the bowel DIE?

Read about management options and individualized care.

Management options: Factor in the variables

DIE can involve the ureters and bladder, the retrocervical and rectovaginal spaces, the appendix, and the bowel. Lesions can be single or multifocal. Although our institutions’ imaging with MRI and TVUS is highly accurate, we additionally recommend the use of colonoscopy (with directed biopsies if appropriate) to evaluate patients who present with rectal bleeding, large endometriotic rectal nodules, or have a family history of bowel cancer.

While many studies have found that surgical resection of DIE improves pain and quality of life, surgery can have significant complications.12 Observation is adequate for asymptomatic patients with DIE. Medical treatment may be offered to patients with mild pain (there is no evidence of a reduction in lesion size with medical therapy). In cases of surgical treatment, we encourage the involvement of a multidisciplinary surgical team to reduce complications and optimize outcomes.

Patients with DIE, significant pain (VAS score, >7), and multiple failed in vitro fertilization treatments are candidates for surgery. When bowel endometriosis is noted on imaging, factors such as size, depth, number of lesions, circumferential involvement, and distance from the anal verge are all used to determine the surgical approach. Rectosigmoid lesions smaller than 3 cm can be treated more conservatively—for example, with shaving or anterior resection with manual repair using disk staplers. Segmental resection generally is indicated for rectosigmoid lesions larger than 3 cm, involvement deeper than the submucosal layer, multiple lesions, circumferential involvement of more than 40%, and the presence of obstructed bowel symptoms.13,14

In patients with DIE who present with both infertility and pain, antimüllerian hormone level and TVUS follicular count are used to evaluate ovarian reserve. As surgical treatment may further reduce ovarian reserve in patients with DIE and infertility, we counsel them regarding assisted reproductive technology options before surgery.

CASE Resolved

After thorough discussion, Mary opts to try a different combination oral contraceptive pill formulation. The pills improve her pain symptoms significantly (VAS score, 4), and she decides to forgo surgery. She will be followed up closely on an outpatient basis with serial TVUS imaging.

Individualize management based on patient parameters

Imaging has been used for the nonsurgical diagnosis of DIE for many years, and this practice increasingly is being accepted and adopted. A presumptive nonsurgical diagnosis of endometriosis can be made based on the clinical signs and symptoms obtained from a thorough history and physical examination, in addition to the absence of imaging findings for ovarian and deep endometriosis.

According to guidelines from major ObGyn societies, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, empiric medical therapy (including combination oral contraceptives, progesterone-containing formulations, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists) can be considered for patients with presumed endometriosis presenting with pain.15

When surgery is chosen, the surgeon must obtain crucial information on the characteristics of the lesion(s) and involve a multidisciplinary team to achieve the best outcomes for the patient.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789-1799.

- Buck Louis GM, Hediger ML, Peterson CM, et al; ENDO Study Working Group. Incidence of endometriosis by study population and diagnostic method: the ENDO study. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):360-365.

- Nisolle M, Donnez J. Peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and adenomyotic nodules of the rectovaginal septum are three different entities. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(4):585-596.

- Bellelis P, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Gonzales M, Baracat EC, Abrao MS. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of pelvic endometriosis--a case series. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2010;56(4):467-471.

- Fauconnier A, Chapron C. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: epidemiological evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(6):595-606.

- Greene R, Stratton P, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Sinaii N. Diagnostic experience among 4,334 women reporting surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(1):32-39.

- Bazot M, Daraï E. Diagnosis of deep endometriosis: clinical examination, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and other techniques. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):886-894.

- Abrão MS, Gonçalves MO, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Chamie LP, Blasbalg R. Comparison between clinical examination, transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(12):3092-3097.

- Young SW, Dahiya N, Patel MD, et al. Initial accuracy of and learning curve for transvaginal ultrasound with bowel preparation for deep endometriosis in a US tertiary care center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(7):1170-1176.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400-412.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 114: Management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):223-236.

- de Paula Andres M, Borrelli GM, Kho RM, Abrão MS. The current management of deep endometriosis: a systematic review. Minerva Ginecol. 2017;69(6):587-596.

- Abrão MS, Podgaec S, Dias JA Jr, Averbach M, Silva LF, Marino de Carvalho F. Endometriosis lesions that compromise the rectum deeper than the inner muscularis layer have more than 40% of the circumference of the rectum affected by the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(3):280-285.

- Abrão MS, Petraglia F, Falcone T, Keckstein J, Osuga Y, Chapron C. Deep endometriosis infiltrating the recto-sigmoid: critical factors to consider before management. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(3):329-339.

- Kho RM, Andres MP, Borrelli GM, Neto JS, Zanluchi A, Abrao MS. Surgical treatment of different types of endometriosis: comparison of major society guidelines and preferred clinical algorithms [published online ahead of print]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn2018.01.020.

- Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789-1799.

- Buck Louis GM, Hediger ML, Peterson CM, et al; ENDO Study Working Group. Incidence of endometriosis by study population and diagnostic method: the ENDO study. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):360-365.

- Nisolle M, Donnez J. Peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and adenomyotic nodules of the rectovaginal septum are three different entities. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(4):585-596.

- Bellelis P, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Gonzales M, Baracat EC, Abrao MS. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of pelvic endometriosis--a case series. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2010;56(4):467-471.

- Fauconnier A, Chapron C. Endometriosis and pelvic pain: epidemiological evidence of the relationship and implications. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(6):595-606.

- Greene R, Stratton P, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Sinaii N. Diagnostic experience among 4,334 women reporting surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(1):32-39.

- Bazot M, Daraï E. Diagnosis of deep endometriosis: clinical examination, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and other techniques. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(6):886-894.

- Abrão MS, Gonçalves MO, Dias JA Jr, Podgaec S, Chamie LP, Blasbalg R. Comparison between clinical examination, transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(12):3092-3097.

- Young SW, Dahiya N, Patel MD, et al. Initial accuracy of and learning curve for transvaginal ultrasound with bowel preparation for deep endometriosis in a US tertiary care center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(7):1170-1176.

- Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, et al; European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):400-412.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 114: Management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):223-236.

- de Paula Andres M, Borrelli GM, Kho RM, Abrão MS. The current management of deep endometriosis: a systematic review. Minerva Ginecol. 2017;69(6):587-596.

- Abrão MS, Podgaec S, Dias JA Jr, Averbach M, Silva LF, Marino de Carvalho F. Endometriosis lesions that compromise the rectum deeper than the inner muscularis layer have more than 40% of the circumference of the rectum affected by the disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(3):280-285.

- Abrão MS, Petraglia F, Falcone T, Keckstein J, Osuga Y, Chapron C. Deep endometriosis infiltrating the recto-sigmoid: critical factors to consider before management. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(3):329-339.

- Kho RM, Andres MP, Borrelli GM, Neto JS, Zanluchi A, Abrao MS. Surgical treatment of different types of endometriosis: comparison of major society guidelines and preferred clinical algorithms [published online ahead of print]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn2018.01.020.

Take-home points

- Specific MRI or TVUS protocols are highly accurate in making a nonsurgical diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE).

- The combination of compelling clinical signs and symptoms and absence of imaging findings for DIE can be used to make a presumptive nonsurgical diagnosis of endometriosis.

- Empiric medical therapy may provide pain relief.

- Conservative treatment, including observation alone, may be considered in asymptomatic patients with DIE and in those with minimal pain.

- Before surgery, it is imperative to know lesion size, depth, circumferential bowel involvement, and location (or distance from the anal verge in cases of rectosigmoid lesion) to optimize surgical outcomes.