User login

Palmoplantar Eruption in a Patient With Mercury Poisoning

Mercury poisoning affects multiple body systems, leading to variable clinical presentations. Mercury intoxication at low levels frequently presents with weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and abdominal pain. At higher levels of mercury intoxication, tremors and neurologic dysfunction are more prevalent.1 Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure vary and include pink disease (acrodynia), mercury exanthem, contact dermatitis, and cutaneous granulomas. Untreated mercury poisoning may result in severe complications, including renal tubular necrosis, pneumonitis, persistent neurologic dysfunction, and fatality in some cases.1,2

Pink disease is a rare disease that typically arises in infants and young children from chronic mercury exposure.3 We report a unique presentation of pink disease occurring in an 18-year-old woman following mercury exposure.

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman who was previously healthy presented to the hospital for evaluation of body aches and back pain. She reported a transient rash on the torso 2 weeks prior, but at the current presentation, only the distal upper and lower extremities were involved. A review of systems revealed myalgia, most severe in the lower back; muscle spasms; stiffness in the fingers; abdominal pain; constipation; paresthesia in the hands and feet; hyperhidrosis; and generalized weakness.

Vitals on admission revealed tachycardia (112 beats per minute). Physical examination revealed the patient was pale and fatigued; she appeared to be in pain, with observable facial grimacing and muscle spasms in the legs. She had poorly demarcated pink macules and papules scattered on the left palm (Figure 1), right forearm, right wrist, and dorsal aspects of the feet including the soles. A few pinpoint pustules were present on the left fifth digit.

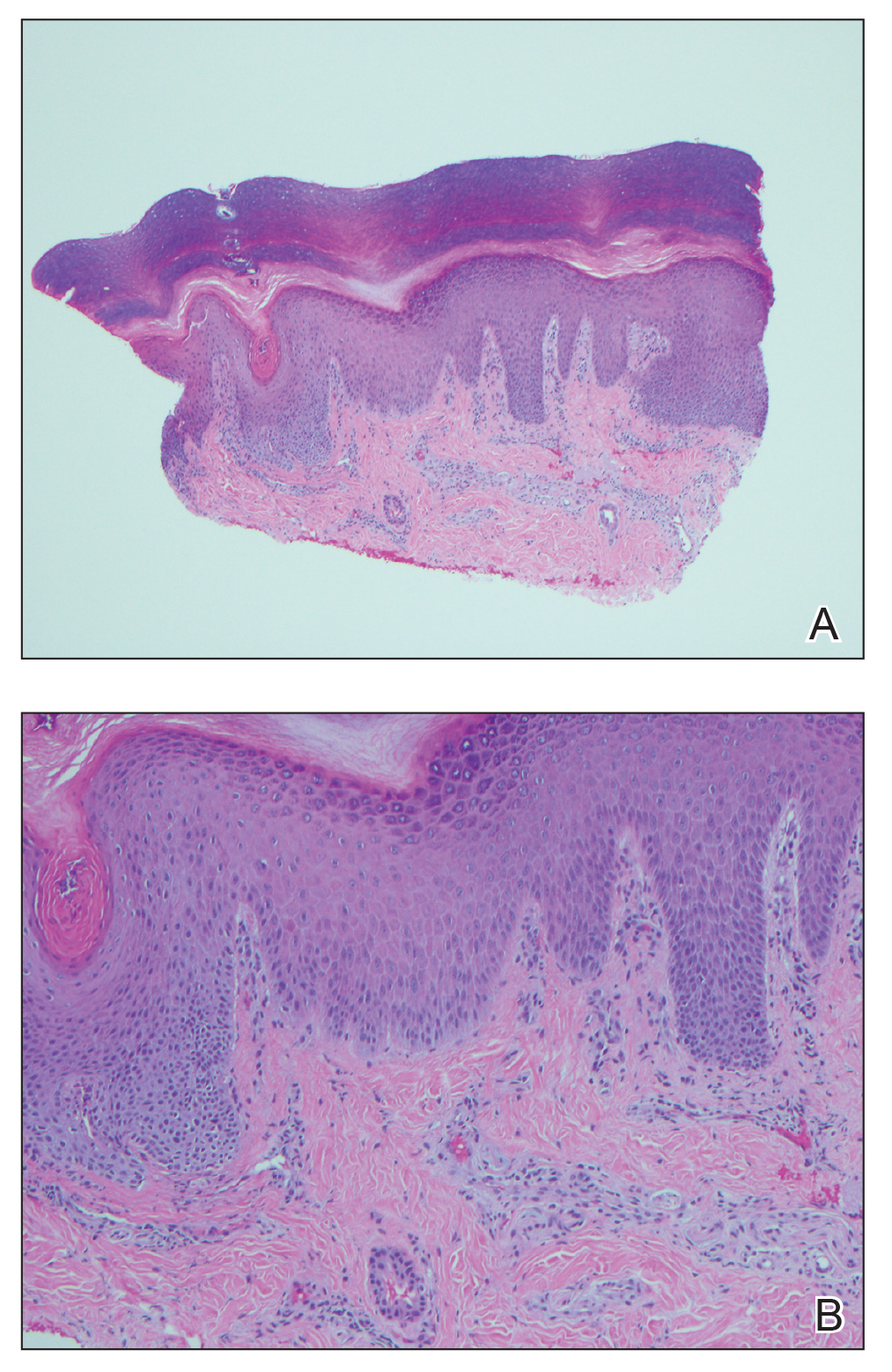

An extensive workup was initiated to rule out infectious, autoimmune, or toxic etiologies. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the left palm were performed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue culture. Findings on hematoxylin and eosin stain were nonspecific, showing acanthosis, orthokeratosis, and a mild interface and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2); superficial bacterial colonization was present, but the tissue culture was negative.

Laboratory studies showed mild transaminitis, and stool was positive for Campylobacter antigen. Electromyography showed myokymia (fascicular muscle contractions). A heavy metal serum panel and urine screen were positive for elevated mercury levels, with a serum mercury level of 23 µg/L (reference range, 0.0–14.9 µg/L) and a urine mercury level of 76 µg/L (reference range, 0–19 µg/L).

Upon further questioning, it was discovered that the patient’s brother and neighbor found a glass bottle containing mercury in their house 10 days prior. They played with the mercury beads with their hands, throwing them around the room and spilling them around the house, which led to mercury exposure in multiple individuals, including our patient. Of note, her brother and neighbor also were hospitalized at the same time as our patient with similar symptoms.

A diagnosis of mercury poisoning was made along with a component of postinfectious reactive arthropathy due to Campylobacter. The myokymia and skin eruption were believed to be secondary to mercury poisoning. The patient was started on ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice daily), intravenous immunoglobulin for Campylobacter, a 2-week treatment regimen with the chelating agent succimer (500 mg twice daily) for mercury poisoning, and a 3-day regimen of pulse intravenous steroids (intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg once daily) to reduce inflammation. Repeat mercury levels showed a downward trend, and the rash improved with time. All family members were advised to undergo testing for mercury exposure.

Comment

Manifestations of Mercury Poisoning

Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure are varied. The most common—allergic contact dermatitis—presents after repeat systemic or topical exposure.4 Mercury exanthem is an acute systemic contact dermatitis most commonly triggered by mercury vapor inhalation. It manifests as an erythematous maculopapular eruption predominantly involving the flexural areas and the anterior thighs in a V-shaped distribution.5 Purpura may be seen in severe cases. Cutaneous granulomas after direct injection of mercury also have been reported as well as cutaneous hyperpigmentation after chronic mercury absorption.6

Presentation of Pink Disease

Pink disease occurs in children after chronic mercury exposure. It was a common pediatric disorder in the 19th century due to the presence of mercury in certain anthelmintics and teething powders.7 However, prevalence drastically decreased after the removal of mercury from these products.3 Although pink disease classically was associated with mercury ingestion, cases also occurred secondary to external application of mercury.7 Additionally, in 1988 a case was reported in a 14-month-old girl after inhalation of mercury vapor from a spilled bottle of mercury.3

Pink disease begins with pink discoloration of the fingertips, nose, and toes, and later progresses to involvement of the hands and feet. Erythema, edema, and desquamation of the hands and feet are seen, along with irritability and autonomic dysfunction that manifests as profuse perspiration, tachycardia, and hypertension.3

Diagnosis of Pink Disease

The differential diagnosis of palmoplantar rash is broad and includes rickettsial disease; syphilis; scabies; toxic shock syndrome; infective endocarditis; meningococcal infection; hand-foot-and-mouth disease; dermatophytosis; and palmoplantar keratodermas. The involvement of the hands and feet in our patient, along with hyperhidrosis, tachycardia, and paresthesia, led us to believe that her condition was a variation of pink disease. The patient’s age at presentation (18 years) was unique, as it is atypical for pink disease. Although the polyarthropathy was attributed to Campylobacter, it is important to note that high levels of mercury exposure also have been associated with polyarthritis,8 polyneuropathy,4 and neuromuscular abnormalities on electromyography.4 Therefore, it is possible that the presence of these symptoms in our patient was either secondary to or compounded by mercury exposure.

Mercury Poisoning

Diagnosis of mercury poisoning can be made by assessing blood, urine, hair, or nail concentrations. However, as mercury deposits in multiple organs, individual concentrations do not correlate with total-body mercury levels.1 Currently, no universal diagnostic criteria for mercury toxicity exist, though a provocation test with the chelating agent 2,

Elemental mercury, as found in some thermometers, dental amalgams, and electrical appliances (eg, certain switches, fluorescent light bulbs), can be converted to inorganic mercury in the body.9 Elemental mercury is vaporized at room temperature; the predominant route of exposure is by subsequent inhalation and lung absorbtion.10 Cutaneous absorption of high concentrations of elementary mercury in either liquid or vapor form may occur, though the rate is slow and absorption is poor. In cases of accidental exposure, contaminated clothing should be removed and immediately decontaminated or disposed. Exposed skin should be washed with a mild soap and water and rinsed thoroughly.10

The treatment of inorganic mercury poisoning is accomplished with the chelating agents succimer, dimercaptopropanesulfonate, dimercaprol, or D-penicillamine.1 In symptomatic cases with high clinical suspicion, the first dose of chelation treatment should be initiated early without delay for laboratory confirmation, as treatment efficacy decreases with an increased interim between exposure and onset of chelation.11 Combination chelation therapy also may be used in treatment. Plasma exchange or hemodialysis are treatment options for extreme, life-threatening cases.1

Conclusion

Mercury exposure should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with a rash on the palms and soles, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms. A high level of suspicion and a thorough history can prevent a delay in treatment and an unnecessarily extensive and expensive workup. An emphasis on early diagnosis and treatment is important for optimal outcomes and can prevent the severe and potentially devastating consequences of mercury toxicity.

- Bernhoft RA. Mercury toxicity and treatment: a review of the literature. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:460508.

- Kamensky OL, Horton D, Kingsley DP, et al. A case of accidental mercury intoxication. J Emerg Med. 2019;56:275-278.

- Dinehart SM, Dillard R, Raimer SS, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of acrodynia (pink disease). Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:107-109.

- Malek A, Aouad K, El Khoury R, et al. Chronic mercury intoxication masquerading as systemic disease: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2017;4:000632.

- Nakayama H, Niki F, Shono M, et al. Mercury exanthem. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:411-417.

- Boyd AS, Seger D, Vannucci S, et al. Mercury exposure and cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:81-90.

- Warkany J. Acrodynia—postmortem of a disease. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112:147-156.

- Karatas¸ GK, Tosun AK, Karacehennem E, et al. Mercury poisoning: an unusual cause of polyarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:73-75.

- Mercury Factsheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Mercury_FactSheet.html. Reviewed April 7, 2017. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- Medical management guidelines for mercury. Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry website. https://www.atsdr.cdc .gov/MMG/MMG.asp?id=106&tid=24. Update October 21, 2014. Accessed September 11, 2020.

- Kosnett MJ. The role of chelation in the treatment of arsenic and mercury poisoning. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:347-354.

Mercury poisoning affects multiple body systems, leading to variable clinical presentations. Mercury intoxication at low levels frequently presents with weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and abdominal pain. At higher levels of mercury intoxication, tremors and neurologic dysfunction are more prevalent.1 Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure vary and include pink disease (acrodynia), mercury exanthem, contact dermatitis, and cutaneous granulomas. Untreated mercury poisoning may result in severe complications, including renal tubular necrosis, pneumonitis, persistent neurologic dysfunction, and fatality in some cases.1,2

Pink disease is a rare disease that typically arises in infants and young children from chronic mercury exposure.3 We report a unique presentation of pink disease occurring in an 18-year-old woman following mercury exposure.

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman who was previously healthy presented to the hospital for evaluation of body aches and back pain. She reported a transient rash on the torso 2 weeks prior, but at the current presentation, only the distal upper and lower extremities were involved. A review of systems revealed myalgia, most severe in the lower back; muscle spasms; stiffness in the fingers; abdominal pain; constipation; paresthesia in the hands and feet; hyperhidrosis; and generalized weakness.

Vitals on admission revealed tachycardia (112 beats per minute). Physical examination revealed the patient was pale and fatigued; she appeared to be in pain, with observable facial grimacing and muscle spasms in the legs. She had poorly demarcated pink macules and papules scattered on the left palm (Figure 1), right forearm, right wrist, and dorsal aspects of the feet including the soles. A few pinpoint pustules were present on the left fifth digit.

An extensive workup was initiated to rule out infectious, autoimmune, or toxic etiologies. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the left palm were performed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue culture. Findings on hematoxylin and eosin stain were nonspecific, showing acanthosis, orthokeratosis, and a mild interface and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2); superficial bacterial colonization was present, but the tissue culture was negative.

Laboratory studies showed mild transaminitis, and stool was positive for Campylobacter antigen. Electromyography showed myokymia (fascicular muscle contractions). A heavy metal serum panel and urine screen were positive for elevated mercury levels, with a serum mercury level of 23 µg/L (reference range, 0.0–14.9 µg/L) and a urine mercury level of 76 µg/L (reference range, 0–19 µg/L).

Upon further questioning, it was discovered that the patient’s brother and neighbor found a glass bottle containing mercury in their house 10 days prior. They played with the mercury beads with their hands, throwing them around the room and spilling them around the house, which led to mercury exposure in multiple individuals, including our patient. Of note, her brother and neighbor also were hospitalized at the same time as our patient with similar symptoms.

A diagnosis of mercury poisoning was made along with a component of postinfectious reactive arthropathy due to Campylobacter. The myokymia and skin eruption were believed to be secondary to mercury poisoning. The patient was started on ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice daily), intravenous immunoglobulin for Campylobacter, a 2-week treatment regimen with the chelating agent succimer (500 mg twice daily) for mercury poisoning, and a 3-day regimen of pulse intravenous steroids (intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg once daily) to reduce inflammation. Repeat mercury levels showed a downward trend, and the rash improved with time. All family members were advised to undergo testing for mercury exposure.

Comment

Manifestations of Mercury Poisoning

Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure are varied. The most common—allergic contact dermatitis—presents after repeat systemic or topical exposure.4 Mercury exanthem is an acute systemic contact dermatitis most commonly triggered by mercury vapor inhalation. It manifests as an erythematous maculopapular eruption predominantly involving the flexural areas and the anterior thighs in a V-shaped distribution.5 Purpura may be seen in severe cases. Cutaneous granulomas after direct injection of mercury also have been reported as well as cutaneous hyperpigmentation after chronic mercury absorption.6

Presentation of Pink Disease

Pink disease occurs in children after chronic mercury exposure. It was a common pediatric disorder in the 19th century due to the presence of mercury in certain anthelmintics and teething powders.7 However, prevalence drastically decreased after the removal of mercury from these products.3 Although pink disease classically was associated with mercury ingestion, cases also occurred secondary to external application of mercury.7 Additionally, in 1988 a case was reported in a 14-month-old girl after inhalation of mercury vapor from a spilled bottle of mercury.3

Pink disease begins with pink discoloration of the fingertips, nose, and toes, and later progresses to involvement of the hands and feet. Erythema, edema, and desquamation of the hands and feet are seen, along with irritability and autonomic dysfunction that manifests as profuse perspiration, tachycardia, and hypertension.3

Diagnosis of Pink Disease

The differential diagnosis of palmoplantar rash is broad and includes rickettsial disease; syphilis; scabies; toxic shock syndrome; infective endocarditis; meningococcal infection; hand-foot-and-mouth disease; dermatophytosis; and palmoplantar keratodermas. The involvement of the hands and feet in our patient, along with hyperhidrosis, tachycardia, and paresthesia, led us to believe that her condition was a variation of pink disease. The patient’s age at presentation (18 years) was unique, as it is atypical for pink disease. Although the polyarthropathy was attributed to Campylobacter, it is important to note that high levels of mercury exposure also have been associated with polyarthritis,8 polyneuropathy,4 and neuromuscular abnormalities on electromyography.4 Therefore, it is possible that the presence of these symptoms in our patient was either secondary to or compounded by mercury exposure.

Mercury Poisoning

Diagnosis of mercury poisoning can be made by assessing blood, urine, hair, or nail concentrations. However, as mercury deposits in multiple organs, individual concentrations do not correlate with total-body mercury levels.1 Currently, no universal diagnostic criteria for mercury toxicity exist, though a provocation test with the chelating agent 2,

Elemental mercury, as found in some thermometers, dental amalgams, and electrical appliances (eg, certain switches, fluorescent light bulbs), can be converted to inorganic mercury in the body.9 Elemental mercury is vaporized at room temperature; the predominant route of exposure is by subsequent inhalation and lung absorbtion.10 Cutaneous absorption of high concentrations of elementary mercury in either liquid or vapor form may occur, though the rate is slow and absorption is poor. In cases of accidental exposure, contaminated clothing should be removed and immediately decontaminated or disposed. Exposed skin should be washed with a mild soap and water and rinsed thoroughly.10

The treatment of inorganic mercury poisoning is accomplished with the chelating agents succimer, dimercaptopropanesulfonate, dimercaprol, or D-penicillamine.1 In symptomatic cases with high clinical suspicion, the first dose of chelation treatment should be initiated early without delay for laboratory confirmation, as treatment efficacy decreases with an increased interim between exposure and onset of chelation.11 Combination chelation therapy also may be used in treatment. Plasma exchange or hemodialysis are treatment options for extreme, life-threatening cases.1

Conclusion

Mercury exposure should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with a rash on the palms and soles, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms. A high level of suspicion and a thorough history can prevent a delay in treatment and an unnecessarily extensive and expensive workup. An emphasis on early diagnosis and treatment is important for optimal outcomes and can prevent the severe and potentially devastating consequences of mercury toxicity.

Mercury poisoning affects multiple body systems, leading to variable clinical presentations. Mercury intoxication at low levels frequently presents with weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and abdominal pain. At higher levels of mercury intoxication, tremors and neurologic dysfunction are more prevalent.1 Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure vary and include pink disease (acrodynia), mercury exanthem, contact dermatitis, and cutaneous granulomas. Untreated mercury poisoning may result in severe complications, including renal tubular necrosis, pneumonitis, persistent neurologic dysfunction, and fatality in some cases.1,2

Pink disease is a rare disease that typically arises in infants and young children from chronic mercury exposure.3 We report a unique presentation of pink disease occurring in an 18-year-old woman following mercury exposure.

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman who was previously healthy presented to the hospital for evaluation of body aches and back pain. She reported a transient rash on the torso 2 weeks prior, but at the current presentation, only the distal upper and lower extremities were involved. A review of systems revealed myalgia, most severe in the lower back; muscle spasms; stiffness in the fingers; abdominal pain; constipation; paresthesia in the hands and feet; hyperhidrosis; and generalized weakness.

Vitals on admission revealed tachycardia (112 beats per minute). Physical examination revealed the patient was pale and fatigued; she appeared to be in pain, with observable facial grimacing and muscle spasms in the legs. She had poorly demarcated pink macules and papules scattered on the left palm (Figure 1), right forearm, right wrist, and dorsal aspects of the feet including the soles. A few pinpoint pustules were present on the left fifth digit.

An extensive workup was initiated to rule out infectious, autoimmune, or toxic etiologies. Two 4-mm punch biopsies of the left palm were performed for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue culture. Findings on hematoxylin and eosin stain were nonspecific, showing acanthosis, orthokeratosis, and a mild interface and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2); superficial bacterial colonization was present, but the tissue culture was negative.

Laboratory studies showed mild transaminitis, and stool was positive for Campylobacter antigen. Electromyography showed myokymia (fascicular muscle contractions). A heavy metal serum panel and urine screen were positive for elevated mercury levels, with a serum mercury level of 23 µg/L (reference range, 0.0–14.9 µg/L) and a urine mercury level of 76 µg/L (reference range, 0–19 µg/L).

Upon further questioning, it was discovered that the patient’s brother and neighbor found a glass bottle containing mercury in their house 10 days prior. They played with the mercury beads with their hands, throwing them around the room and spilling them around the house, which led to mercury exposure in multiple individuals, including our patient. Of note, her brother and neighbor also were hospitalized at the same time as our patient with similar symptoms.

A diagnosis of mercury poisoning was made along with a component of postinfectious reactive arthropathy due to Campylobacter. The myokymia and skin eruption were believed to be secondary to mercury poisoning. The patient was started on ciprofloxacin (750 mg twice daily), intravenous immunoglobulin for Campylobacter, a 2-week treatment regimen with the chelating agent succimer (500 mg twice daily) for mercury poisoning, and a 3-day regimen of pulse intravenous steroids (intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg once daily) to reduce inflammation. Repeat mercury levels showed a downward trend, and the rash improved with time. All family members were advised to undergo testing for mercury exposure.

Comment

Manifestations of Mercury Poisoning

Dermatologic manifestations of mercury exposure are varied. The most common—allergic contact dermatitis—presents after repeat systemic or topical exposure.4 Mercury exanthem is an acute systemic contact dermatitis most commonly triggered by mercury vapor inhalation. It manifests as an erythematous maculopapular eruption predominantly involving the flexural areas and the anterior thighs in a V-shaped distribution.5 Purpura may be seen in severe cases. Cutaneous granulomas after direct injection of mercury also have been reported as well as cutaneous hyperpigmentation after chronic mercury absorption.6

Presentation of Pink Disease

Pink disease occurs in children after chronic mercury exposure. It was a common pediatric disorder in the 19th century due to the presence of mercury in certain anthelmintics and teething powders.7 However, prevalence drastically decreased after the removal of mercury from these products.3 Although pink disease classically was associated with mercury ingestion, cases also occurred secondary to external application of mercury.7 Additionally, in 1988 a case was reported in a 14-month-old girl after inhalation of mercury vapor from a spilled bottle of mercury.3

Pink disease begins with pink discoloration of the fingertips, nose, and toes, and later progresses to involvement of the hands and feet. Erythema, edema, and desquamation of the hands and feet are seen, along with irritability and autonomic dysfunction that manifests as profuse perspiration, tachycardia, and hypertension.3

Diagnosis of Pink Disease

The differential diagnosis of palmoplantar rash is broad and includes rickettsial disease; syphilis; scabies; toxic shock syndrome; infective endocarditis; meningococcal infection; hand-foot-and-mouth disease; dermatophytosis; and palmoplantar keratodermas. The involvement of the hands and feet in our patient, along with hyperhidrosis, tachycardia, and paresthesia, led us to believe that her condition was a variation of pink disease. The patient’s age at presentation (18 years) was unique, as it is atypical for pink disease. Although the polyarthropathy was attributed to Campylobacter, it is important to note that high levels of mercury exposure also have been associated with polyarthritis,8 polyneuropathy,4 and neuromuscular abnormalities on electromyography.4 Therefore, it is possible that the presence of these symptoms in our patient was either secondary to or compounded by mercury exposure.

Mercury Poisoning

Diagnosis of mercury poisoning can be made by assessing blood, urine, hair, or nail concentrations. However, as mercury deposits in multiple organs, individual concentrations do not correlate with total-body mercury levels.1 Currently, no universal diagnostic criteria for mercury toxicity exist, though a provocation test with the chelating agent 2,

Elemental mercury, as found in some thermometers, dental amalgams, and electrical appliances (eg, certain switches, fluorescent light bulbs), can be converted to inorganic mercury in the body.9 Elemental mercury is vaporized at room temperature; the predominant route of exposure is by subsequent inhalation and lung absorbtion.10 Cutaneous absorption of high concentrations of elementary mercury in either liquid or vapor form may occur, though the rate is slow and absorption is poor. In cases of accidental exposure, contaminated clothing should be removed and immediately decontaminated or disposed. Exposed skin should be washed with a mild soap and water and rinsed thoroughly.10

The treatment of inorganic mercury poisoning is accomplished with the chelating agents succimer, dimercaptopropanesulfonate, dimercaprol, or D-penicillamine.1 In symptomatic cases with high clinical suspicion, the first dose of chelation treatment should be initiated early without delay for laboratory confirmation, as treatment efficacy decreases with an increased interim between exposure and onset of chelation.11 Combination chelation therapy also may be used in treatment. Plasma exchange or hemodialysis are treatment options for extreme, life-threatening cases.1

Conclusion

Mercury exposure should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting with a rash on the palms and soles, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms. A high level of suspicion and a thorough history can prevent a delay in treatment and an unnecessarily extensive and expensive workup. An emphasis on early diagnosis and treatment is important for optimal outcomes and can prevent the severe and potentially devastating consequences of mercury toxicity.

- Bernhoft RA. Mercury toxicity and treatment: a review of the literature. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:460508.

- Kamensky OL, Horton D, Kingsley DP, et al. A case of accidental mercury intoxication. J Emerg Med. 2019;56:275-278.

- Dinehart SM, Dillard R, Raimer SS, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of acrodynia (pink disease). Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:107-109.

- Malek A, Aouad K, El Khoury R, et al. Chronic mercury intoxication masquerading as systemic disease: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2017;4:000632.

- Nakayama H, Niki F, Shono M, et al. Mercury exanthem. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:411-417.

- Boyd AS, Seger D, Vannucci S, et al. Mercury exposure and cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:81-90.

- Warkany J. Acrodynia—postmortem of a disease. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112:147-156.

- Karatas¸ GK, Tosun AK, Karacehennem E, et al. Mercury poisoning: an unusual cause of polyarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:73-75.

- Mercury Factsheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Mercury_FactSheet.html. Reviewed April 7, 2017. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- Medical management guidelines for mercury. Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry website. https://www.atsdr.cdc .gov/MMG/MMG.asp?id=106&tid=24. Update October 21, 2014. Accessed September 11, 2020.

- Kosnett MJ. The role of chelation in the treatment of arsenic and mercury poisoning. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:347-354.

- Bernhoft RA. Mercury toxicity and treatment: a review of the literature. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:460508.

- Kamensky OL, Horton D, Kingsley DP, et al. A case of accidental mercury intoxication. J Emerg Med. 2019;56:275-278.

- Dinehart SM, Dillard R, Raimer SS, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of acrodynia (pink disease). Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:107-109.

- Malek A, Aouad K, El Khoury R, et al. Chronic mercury intoxication masquerading as systemic disease: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2017;4:000632.

- Nakayama H, Niki F, Shono M, et al. Mercury exanthem. Contact Dermatitis. 1983;9:411-417.

- Boyd AS, Seger D, Vannucci S, et al. Mercury exposure and cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:81-90.

- Warkany J. Acrodynia—postmortem of a disease. Am J Dis Child. 1966;112:147-156.

- Karatas¸ GK, Tosun AK, Karacehennem E, et al. Mercury poisoning: an unusual cause of polyarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2002;21:73-75.

- Mercury Factsheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Mercury_FactSheet.html. Reviewed April 7, 2017. Accessed October 21, 2020.

- Medical management guidelines for mercury. Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry website. https://www.atsdr.cdc .gov/MMG/MMG.asp?id=106&tid=24. Update October 21, 2014. Accessed September 11, 2020.

- Kosnett MJ. The role of chelation in the treatment of arsenic and mercury poisoning. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9:347-354.

Practice Points

- The dermatologic and histologic presentation of mercury exposure may be nonspecific, requiring a high degree of clinical suspicion to make a diagnosis.

- Mercury exposure should be included in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with a rash of the palms and soles, especially in young patients with systemic symptoms.

Adult-Onset Asymmetrical Lipomatosis

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman presented with extra growth of subcutaneous fat at the left anterior infradiaphragm that expanded circumferentially to the left back over the last 4 years. Two years prior to the current presentation, the left thigh became visibly thicker than the right. Diffuse subtle lipomatosis affecting the ipsilateral face, neck, arms, calf, and foot was noted at that time. Additionally, the patient had hyperlipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, osteoporosis, and scoliosis, all beginning in her late 60s. She reported no alcohol or tobacco use and was taking rosuvastatin, esomeprazole, calcium, vitamin D, and glucosamine. There was no reported family history of asymmetric growth or bony deformities, and her children were healthy.

On physical examination, the lipomatosis affected the entire left side, most prominently around the abdomen, back, and thighs. The affected side was nontender and nonpruritic; there was no atrophy of the unaffected side (Figure). Maximum thigh circumference was 55.1 cm on the affected side and 52.6 cm on the unaffected side. There were no differences in power, reflex, or sensation between the 2 sides, and no hyperhidrosis or vascular malformations were present. Laboratory investigations, including complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, lipids, and thyroid-stimulating and sex hormone panels all were within reference range.

Enzi et al1 reported 2 women who developed asymmetrical lipomatosis between the ages of 13 and 20 years. Acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis should be differentiated from the asymmetrical overgrowth diagnosed in neonates and infants.

Proteus syndrome (PS) is a progressive disease involving a combination of overgrowth in a mosaic distribution, connective tissue and epidermal nevi, ovarian cysts, parotid gland tumor, dysregulated adipose tissue, lymphovascular malformation, and certain facial phenotypes.2,3 The average age of onset is 6 to 18 months, and half of cases present at birth.3,4 Hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome (HHML) describes a mild and nonprogressive variant that does not satisfy the diagnostic criteria of PS; it typically is diagnosed at birth.5 One case of mild and delayed-onset PS was described in a woman who started developing signs at 15 years of age.6 In comparison, asymmetrical lipomatosis and scoliosis were the only abnormal clinical signs present in our patient, and the lipomatosis developed diffusely, as opposed to the typical mosaic distribution found in PS and HHML. Scoliosis can be found in PS and HHML secondary to hemihypertrophy of vertebra or infiltrative intraspinal lipomatosis.7,8 Our patient’s scoliosis was diagnosed more than 10 years prior to the onset of lipomatosis, likely representing degenerative joint disease.9

Prior reported cases of asymmetrical lipomatosis did not describe treatment.1 Ultrasound-guided or conventional liposuction and lipectomy are mainstream therapies for multiple symmetrical lipomatosis, an acquired lipomatosis typically affecting alcoholics in the fourth decade of life. However, recurrence rates are high for surgical treatment of unencapsulated lipomatosis, likely due to incomplete removal of the adipose tissue.10 Alternative treatments found in case reports, including oral salbutamol, mesotherapy using phosphatidylcholine, and fenofibrate (200 mg/d), require further study.11-13 Our patient was not aesthetically bothered by her lipomatosis; therefore, imaging and treatment options were not pursued. In conclusion, we report a patient with acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis with onset in late adulthood, unique from the existing syndromes of asymmetrical hemihyperplasia.1,14

- Enzi G, Digito M, Enzi GB, et al. Asymmetrical lipomatosis: report of two cases. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61:797-800.

- Biesecker LG, Happle R, Mulliken JB, et al. Proteus syndrome: diagnostic criteria, differential diagnosis, and patient evaluation. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84:389-395.

- Biesecker L. The challenges of Proteus syndrome: diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:1151-1157.

- Cohen MM Jr. Proteus syndrome: an update. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2005;137C:38-52.

- Biesecker LG, Peters KF, Darling TN, et al. Clinical differentiation between Proteus syndrome and hemihyperplasia: description of a distinct form of hemihyperplasia. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:311-318.

- Luo S, Feng Y, Zheng Y, et al. Mild and delayed-onset Proteus syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:172-173.

- Takebayashi T, Yamashita T, Yokogushi K, et al. Scoliosis in Proteus syndrome: case report. Spine. 2001;26:E395-E398.

- Schulte TL, Liljenqvist U, Görgens H, et al. Hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome (HHML): a challenge in spinal care. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:714-719.

- Robin GC, Span Y, Steinberg R, et al. Scoliosis in the elderly: a follow-up study. Spine. 1982;7:355-359.

- Brea-García B, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Couto-González I, et al. Madelung’s disease: comorbidities, fatty mass distribution, and response to treatment of 22 patients. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2013;37:409-416.

- Hasegawa T, Matsukura T, Ikeda S. Mesotherapy for benign symmetric lipomatosis. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2010;34:153-156.

- Zeitler H, Ulrich-Merzenich G, Richter DF, et al. Multiple benign symmetric lipomatosis—a differential diagnosis of obesity. is there a rationale for fibrate treatment? Obes Surg. 2008;18:1354-1356.

- Leung N, Gaer J, Beggs D, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis (Launois‐Bensaude syndrome): effect of oral salbutamol. Clin Endocrinol. 1987;27:601-606.

- Craiglow BG, Ko CJ, Antaya RJ. Two cases of hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome and review of asymmetric hemihyperplasia syndromes. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:507-510.

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman presented with extra growth of subcutaneous fat at the left anterior infradiaphragm that expanded circumferentially to the left back over the last 4 years. Two years prior to the current presentation, the left thigh became visibly thicker than the right. Diffuse subtle lipomatosis affecting the ipsilateral face, neck, arms, calf, and foot was noted at that time. Additionally, the patient had hyperlipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, osteoporosis, and scoliosis, all beginning in her late 60s. She reported no alcohol or tobacco use and was taking rosuvastatin, esomeprazole, calcium, vitamin D, and glucosamine. There was no reported family history of asymmetric growth or bony deformities, and her children were healthy.

On physical examination, the lipomatosis affected the entire left side, most prominently around the abdomen, back, and thighs. The affected side was nontender and nonpruritic; there was no atrophy of the unaffected side (Figure). Maximum thigh circumference was 55.1 cm on the affected side and 52.6 cm on the unaffected side. There were no differences in power, reflex, or sensation between the 2 sides, and no hyperhidrosis or vascular malformations were present. Laboratory investigations, including complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, lipids, and thyroid-stimulating and sex hormone panels all were within reference range.

Enzi et al1 reported 2 women who developed asymmetrical lipomatosis between the ages of 13 and 20 years. Acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis should be differentiated from the asymmetrical overgrowth diagnosed in neonates and infants.

Proteus syndrome (PS) is a progressive disease involving a combination of overgrowth in a mosaic distribution, connective tissue and epidermal nevi, ovarian cysts, parotid gland tumor, dysregulated adipose tissue, lymphovascular malformation, and certain facial phenotypes.2,3 The average age of onset is 6 to 18 months, and half of cases present at birth.3,4 Hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome (HHML) describes a mild and nonprogressive variant that does not satisfy the diagnostic criteria of PS; it typically is diagnosed at birth.5 One case of mild and delayed-onset PS was described in a woman who started developing signs at 15 years of age.6 In comparison, asymmetrical lipomatosis and scoliosis were the only abnormal clinical signs present in our patient, and the lipomatosis developed diffusely, as opposed to the typical mosaic distribution found in PS and HHML. Scoliosis can be found in PS and HHML secondary to hemihypertrophy of vertebra or infiltrative intraspinal lipomatosis.7,8 Our patient’s scoliosis was diagnosed more than 10 years prior to the onset of lipomatosis, likely representing degenerative joint disease.9

Prior reported cases of asymmetrical lipomatosis did not describe treatment.1 Ultrasound-guided or conventional liposuction and lipectomy are mainstream therapies for multiple symmetrical lipomatosis, an acquired lipomatosis typically affecting alcoholics in the fourth decade of life. However, recurrence rates are high for surgical treatment of unencapsulated lipomatosis, likely due to incomplete removal of the adipose tissue.10 Alternative treatments found in case reports, including oral salbutamol, mesotherapy using phosphatidylcholine, and fenofibrate (200 mg/d), require further study.11-13 Our patient was not aesthetically bothered by her lipomatosis; therefore, imaging and treatment options were not pursued. In conclusion, we report a patient with acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis with onset in late adulthood, unique from the existing syndromes of asymmetrical hemihyperplasia.1,14

To the Editor:

An 85-year-old woman presented with extra growth of subcutaneous fat at the left anterior infradiaphragm that expanded circumferentially to the left back over the last 4 years. Two years prior to the current presentation, the left thigh became visibly thicker than the right. Diffuse subtle lipomatosis affecting the ipsilateral face, neck, arms, calf, and foot was noted at that time. Additionally, the patient had hyperlipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, osteoporosis, and scoliosis, all beginning in her late 60s. She reported no alcohol or tobacco use and was taking rosuvastatin, esomeprazole, calcium, vitamin D, and glucosamine. There was no reported family history of asymmetric growth or bony deformities, and her children were healthy.

On physical examination, the lipomatosis affected the entire left side, most prominently around the abdomen, back, and thighs. The affected side was nontender and nonpruritic; there was no atrophy of the unaffected side (Figure). Maximum thigh circumference was 55.1 cm on the affected side and 52.6 cm on the unaffected side. There were no differences in power, reflex, or sensation between the 2 sides, and no hyperhidrosis or vascular malformations were present. Laboratory investigations, including complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, lipids, and thyroid-stimulating and sex hormone panels all were within reference range.

Enzi et al1 reported 2 women who developed asymmetrical lipomatosis between the ages of 13 and 20 years. Acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis should be differentiated from the asymmetrical overgrowth diagnosed in neonates and infants.

Proteus syndrome (PS) is a progressive disease involving a combination of overgrowth in a mosaic distribution, connective tissue and epidermal nevi, ovarian cysts, parotid gland tumor, dysregulated adipose tissue, lymphovascular malformation, and certain facial phenotypes.2,3 The average age of onset is 6 to 18 months, and half of cases present at birth.3,4 Hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome (HHML) describes a mild and nonprogressive variant that does not satisfy the diagnostic criteria of PS; it typically is diagnosed at birth.5 One case of mild and delayed-onset PS was described in a woman who started developing signs at 15 years of age.6 In comparison, asymmetrical lipomatosis and scoliosis were the only abnormal clinical signs present in our patient, and the lipomatosis developed diffusely, as opposed to the typical mosaic distribution found in PS and HHML. Scoliosis can be found in PS and HHML secondary to hemihypertrophy of vertebra or infiltrative intraspinal lipomatosis.7,8 Our patient’s scoliosis was diagnosed more than 10 years prior to the onset of lipomatosis, likely representing degenerative joint disease.9

Prior reported cases of asymmetrical lipomatosis did not describe treatment.1 Ultrasound-guided or conventional liposuction and lipectomy are mainstream therapies for multiple symmetrical lipomatosis, an acquired lipomatosis typically affecting alcoholics in the fourth decade of life. However, recurrence rates are high for surgical treatment of unencapsulated lipomatosis, likely due to incomplete removal of the adipose tissue.10 Alternative treatments found in case reports, including oral salbutamol, mesotherapy using phosphatidylcholine, and fenofibrate (200 mg/d), require further study.11-13 Our patient was not aesthetically bothered by her lipomatosis; therefore, imaging and treatment options were not pursued. In conclusion, we report a patient with acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis with onset in late adulthood, unique from the existing syndromes of asymmetrical hemihyperplasia.1,14

- Enzi G, Digito M, Enzi GB, et al. Asymmetrical lipomatosis: report of two cases. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61:797-800.

- Biesecker LG, Happle R, Mulliken JB, et al. Proteus syndrome: diagnostic criteria, differential diagnosis, and patient evaluation. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84:389-395.

- Biesecker L. The challenges of Proteus syndrome: diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:1151-1157.

- Cohen MM Jr. Proteus syndrome: an update. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2005;137C:38-52.

- Biesecker LG, Peters KF, Darling TN, et al. Clinical differentiation between Proteus syndrome and hemihyperplasia: description of a distinct form of hemihyperplasia. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:311-318.

- Luo S, Feng Y, Zheng Y, et al. Mild and delayed-onset Proteus syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:172-173.

- Takebayashi T, Yamashita T, Yokogushi K, et al. Scoliosis in Proteus syndrome: case report. Spine. 2001;26:E395-E398.

- Schulte TL, Liljenqvist U, Görgens H, et al. Hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome (HHML): a challenge in spinal care. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:714-719.

- Robin GC, Span Y, Steinberg R, et al. Scoliosis in the elderly: a follow-up study. Spine. 1982;7:355-359.

- Brea-García B, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Couto-González I, et al. Madelung’s disease: comorbidities, fatty mass distribution, and response to treatment of 22 patients. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2013;37:409-416.

- Hasegawa T, Matsukura T, Ikeda S. Mesotherapy for benign symmetric lipomatosis. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2010;34:153-156.

- Zeitler H, Ulrich-Merzenich G, Richter DF, et al. Multiple benign symmetric lipomatosis—a differential diagnosis of obesity. is there a rationale for fibrate treatment? Obes Surg. 2008;18:1354-1356.

- Leung N, Gaer J, Beggs D, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis (Launois‐Bensaude syndrome): effect of oral salbutamol. Clin Endocrinol. 1987;27:601-606.

- Craiglow BG, Ko CJ, Antaya RJ. Two cases of hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome and review of asymmetric hemihyperplasia syndromes. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:507-510.

- Enzi G, Digito M, Enzi GB, et al. Asymmetrical lipomatosis: report of two cases. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61:797-800.

- Biesecker LG, Happle R, Mulliken JB, et al. Proteus syndrome: diagnostic criteria, differential diagnosis, and patient evaluation. Am J Med Genet. 1999;84:389-395.

- Biesecker L. The challenges of Proteus syndrome: diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:1151-1157.

- Cohen MM Jr. Proteus syndrome: an update. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2005;137C:38-52.

- Biesecker LG, Peters KF, Darling TN, et al. Clinical differentiation between Proteus syndrome and hemihyperplasia: description of a distinct form of hemihyperplasia. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:311-318.

- Luo S, Feng Y, Zheng Y, et al. Mild and delayed-onset Proteus syndrome. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:172-173.

- Takebayashi T, Yamashita T, Yokogushi K, et al. Scoliosis in Proteus syndrome: case report. Spine. 2001;26:E395-E398.

- Schulte TL, Liljenqvist U, Görgens H, et al. Hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome (HHML): a challenge in spinal care. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;74:714-719.

- Robin GC, Span Y, Steinberg R, et al. Scoliosis in the elderly: a follow-up study. Spine. 1982;7:355-359.

- Brea-García B, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Couto-González I, et al. Madelung’s disease: comorbidities, fatty mass distribution, and response to treatment of 22 patients. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2013;37:409-416.

- Hasegawa T, Matsukura T, Ikeda S. Mesotherapy for benign symmetric lipomatosis. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2010;34:153-156.

- Zeitler H, Ulrich-Merzenich G, Richter DF, et al. Multiple benign symmetric lipomatosis—a differential diagnosis of obesity. is there a rationale for fibrate treatment? Obes Surg. 2008;18:1354-1356.

- Leung N, Gaer J, Beggs D, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis (Launois‐Bensaude syndrome): effect of oral salbutamol. Clin Endocrinol. 1987;27:601-606.

- Craiglow BG, Ko CJ, Antaya RJ. Two cases of hemihyperplasia-multiple lipomatosis syndrome and review of asymmetric hemihyperplasia syndromes. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:507-510.

Practice Points

- Acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis is a rare condition that can develop at any age; it should be differentiated from existing syndromes of asymmetrical hemihyperplasia.

- Acquired asymmetrical lipomatosis is a clinical diagnosis with no laboratory changes. If the patient is clinically stable and asymptomatic, no further investigation or management is required.