User login

Disruptive Physician Behavior: The Importance of Recognition and Intervention and Its Impact on Patient Safety

Dramatic stories of disruptive physician behavior (DPB) appear occasionally in the news, such as the physician who shot and killed a colleague within hospital confines or the gynecologist who secretly took photographs using a camera disguised as a pen during pelvic examinations. More common in hospitals, however, are incidents of inappropriate behavior that may generate complaints from patients or other providers and at times snowball into administrative or legal challenges.

“Professionalism” is one of the six competencies listed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)1 and the American Board of Medical Specialties. Unfortunately, incidents of disruptive behavior can result in violation of the tenets of professionalism in the healthcare environment. These behaviors fall along a continuum ranging from outwardly aggressive and uncivil to overly passive and insidious. Although these behaviors can occur across all healthcare disciplines and settings and are not just limited to physicians, the behaviors of physicians often have a much greater impact on the healthcare system as a whole because of their positions of relative “power” within the system.2 Hence, this problem requires greater awareness and education. In this context, the aim of this article is to discuss disruptive behaviors in physicians

The AMA defines DPB as “personal conduct, verbal or physical that has the potential to negatively affect patient care or the ability to work with other members of the healthcare team.”3 The definition of DPB by the Joint Commission includes “all behaviors that undermine a culture of safety.”4 Both the Joint Commission and the AMA recognize the significance and patient safety implications of such behavior. Policy statements by both these organizations underscore the importance of confronting and remedying these potentially dangerous interpersonal behaviors.

Data regarding the prevalence of DPB have been inconsistent. One study estimated that 3%–5% of physicians demonstrate this behavior,5 whereas another study reported a DPB prevalence of 97% among physicians and nurses in the workplace.6 According to a 2004 survey of physician executives, more than 95% of them reported regular encounters of DPB.7

The etiology of such disruptive behaviors is multifactorial and complex. Explanations associated with ‘nature versus nurture’ have ranged from physician psychopathology to unhealthy modeling during training. Both extrinsic and intrinsic factors may also contribute to DPB. External stressors and negative experiences–professional and/or personal–can provoke disruptive behaviors. Overwork, fatigue, strife, and a dysfunctional environment that can arise in both work and home environments can contribute to the development of mental health problems. Stress, burnout, and depression have increasingly become prevalent among physicians and can play a significant role in causing impaired patterns of professional conduct.8, 9 These mental health problems can cause physicians to acquire maladaptive coping strategies such as substance abuse and drug or alcohol dependence. However, it is important to note that physician impairment and substance abuse are not the most frequent causes of DPB. In fact, fewer than 10% of physician behavior issues have been related to substance abuse.2, 5

Psychiatric disorders such as major depression and bipolar and anxiety disorders may also contribute to DPB.10 Most of these disorders (except for schizophrenia) are likely as common among physicians as among the general public.9 An essential clarification is that although DPB can be a manifestation of personality disorders or psychiatric disorders, it does not always stem from underlying psychopathology. Clarifying these distinctions is important for managing the problem and calls for expert professional evaluation in some cases.10

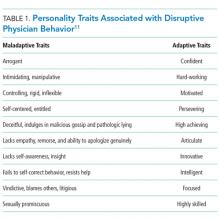

A person’s behavior is shaped by character, values, perceptions, and attitudes. Individuals who engage in DPB typically lack insight and justify their behaviors as a means to achieve a goal. Disrespectful behavior is rooted, in part, in characteristics such as insecurity, immaturity, and aggressiveness; however, it can also be learned, tolerated, and reinforced in the hierarchical hospital culture.11

Other intrinsic factors that may contribute to DPB include lack of emotional intelligence, poor social skills, cultural and ethnic issues, and generation and gender bias.12 Identifying the root causes of DPB can be challenging due to the complexity of the interaction between the healthcare environment and the key players within it; nevertheless, awareness of the contributing factors and early recognition are important. Those who take on the mantle of leadership within hospitals should be educated in this regard.

Repercussions of Disruptive Physician Behavior

An institution’s organizational culture often has an impact on how DPB is addressed. Tolerance of such behavior can have far-reaching consequences. The central tenets of a “culture of safety and respect”–teamwork across disciplines and a blame-free environment in which every member of the healthcare team feels equally empowered to report errors and openly discuss safety issues–would be negatively impacted.

DPB can diminish the quality of care provided, increase the risk of medical errors, and adversely affect patient safety and satisfaction.11-13 Such behavior can cause erosion of relationships and communication between individuals and contribute to a hostile work environment. For instance, nurses or trainees may be afraid to question a physician because of the fear of getting yelled at or being humiliated. Consequently, improperly written orders may be overlooked or a potentially “wrong-site” surgical procedure may not be questioned for fear of provoking a hostile response.

DPB can increase litigation risk and financial costs to institutions. Provider retention may be adversely affected; valued staff may leave hospitals and need to be replaced, and productivity may suffer. When physicians in training observe how their superiors model disruptive behaviors with impunity, a concerning problem that arises is that DPB becomes normalized in the workplace culture, especially if such behaviors are tolerated and result in a perceived gain.

Proposed Interventions

Confrontation of DPB can be challenging without appropriate infrastructure. Healthcare facilities should have a fair system in place for reliable reporting and monitoring of DPB, including a complaints’ verification process, appeals process, and an option for fair hearing.

It is best to initially address the issue in a direct, timely, yet informal manner through counseling or a verbal warning. In several situations, such informal counseling opportunities create a mindful awareness of the problem and the problematic behavior ceases without the need for further action.

When informal intervention is either not appropriate (eg, if the alleged event involved an assault or other illegal behavior) or has already been offered in the past, more formal intervention is required. Institutional progressive disciplinary polices should be in place and adhered to. For example, repeat offenders may be issued written warnings or even temporary suspension of privileges.

Institutional resources such as human resources departments, office of general counsel, office of medical affairs, and the hospital’s medical board may be consulted. Some medical centers have “employee assistance programs” staffed with clinicians skilled in dealing with DPB. Individuals diagnosed with substance abuse or a mental health disorder may require consultation with mental health professionals.14

Special “Professionalism Committees” can be instituted and tasked with investigating complaints and making recommendations for the involvement of resources outside the institution, such as a state medical society.15

Conclusion

Although the vast majority of physicians are well-behaved, it is important to acknowledge that disruptive behaviors can occur in the healthcare environment. Such behaviors have a major impact on workplace culture and patient safety and must be recognized early. Hospital executives and leaders must ensure that appropriate interventions are undertaken—before the quality of patient care is affected and before lives are endangered.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Ansu John for providing editorial assistance with the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose (Conflict of Interest Form submitted as separate PDF document). Dr. Heitt consults with local hospitals, medical practices, and licensing boards regarding physicians and other healthcare practitioners who have been accused of engaging in disruptive behavior. In these situations he may be paid by the board, medical society, hospital, practice or the professional (patient).

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements: general competencies. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011[2].pdf. Accessed July 25, 2017.

2. Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: a persistent threat to patient safety. Patient safety and quality healthcare. Lionheart Publishing, Inc. 2006;3:16-24 https://www.psqh.com/julaug06/disruptive.html. Accessed October 1, 2017.

3. American Medical Association. Opinion E- 9.045–Physicians with disruptive behavior. Chicago, IL American Medical Association 2008.

4. Joint Commission: Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. Sentinel event alert, July 9, 2008:40. http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_40_behaviors_that_undermine_a_culture_of_safety/. Accessed October 1, 2017.

5. Leape LL, Fromson JA. Problem doctors: is there a system-level solution? Ann Int Med. 2006;144:107-115. PubMed

6. Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(8):464-471. PubMed

7. Weber DO. Poll Results: Doctors’ disruptive behavior disturbs physician leaders. The Physician Executive. 2004;30(5):6. PubMed

8. Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3161-3166. PubMed

9. Brown S, Goske M, Johnson C. Beyond substance abuse: stress, burnout and depression as causes of physician impairment and disruptive behavior. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009 6;(7):479-485. PubMed

10. Reynolds NT. Disruptive physician behavior: use and misuse of the label. J Med Regulation. 2012;98(1):8-19.

11. Leape LL, Shore MF, Dienstag JL, et al. Perspective: a culture of respect, part 1: the nature and causes of disrespectful behavior by physicians. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):845-852. PubMed

12. Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. Impact and implications of disruptive behavior in the perioperative arena. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(1):96-105. PubMed

13. Patient Safety Primer: Disruptive and unprofessional behavior. Available at AHRQ Patient Safety Network: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/15/disruptive-and-unprofessional-behavior(Accessed October 1, 2017.

14. Williams BW, Williams MV. The disruptive physician: conceptual organization. JMed Licensure Discipline. 2008;94(3):12-19.

15. Speck R, Foster J, Mulhem V, et al. Development of a professionalism committee approach to address unprofessional medical staff behavior at an academic medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2004;40(4):161-167. PubMed

Dramatic stories of disruptive physician behavior (DPB) appear occasionally in the news, such as the physician who shot and killed a colleague within hospital confines or the gynecologist who secretly took photographs using a camera disguised as a pen during pelvic examinations. More common in hospitals, however, are incidents of inappropriate behavior that may generate complaints from patients or other providers and at times snowball into administrative or legal challenges.

“Professionalism” is one of the six competencies listed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)1 and the American Board of Medical Specialties. Unfortunately, incidents of disruptive behavior can result in violation of the tenets of professionalism in the healthcare environment. These behaviors fall along a continuum ranging from outwardly aggressive and uncivil to overly passive and insidious. Although these behaviors can occur across all healthcare disciplines and settings and are not just limited to physicians, the behaviors of physicians often have a much greater impact on the healthcare system as a whole because of their positions of relative “power” within the system.2 Hence, this problem requires greater awareness and education. In this context, the aim of this article is to discuss disruptive behaviors in physicians

The AMA defines DPB as “personal conduct, verbal or physical that has the potential to negatively affect patient care or the ability to work with other members of the healthcare team.”3 The definition of DPB by the Joint Commission includes “all behaviors that undermine a culture of safety.”4 Both the Joint Commission and the AMA recognize the significance and patient safety implications of such behavior. Policy statements by both these organizations underscore the importance of confronting and remedying these potentially dangerous interpersonal behaviors.

Data regarding the prevalence of DPB have been inconsistent. One study estimated that 3%–5% of physicians demonstrate this behavior,5 whereas another study reported a DPB prevalence of 97% among physicians and nurses in the workplace.6 According to a 2004 survey of physician executives, more than 95% of them reported regular encounters of DPB.7

The etiology of such disruptive behaviors is multifactorial and complex. Explanations associated with ‘nature versus nurture’ have ranged from physician psychopathology to unhealthy modeling during training. Both extrinsic and intrinsic factors may also contribute to DPB. External stressors and negative experiences–professional and/or personal–can provoke disruptive behaviors. Overwork, fatigue, strife, and a dysfunctional environment that can arise in both work and home environments can contribute to the development of mental health problems. Stress, burnout, and depression have increasingly become prevalent among physicians and can play a significant role in causing impaired patterns of professional conduct.8, 9 These mental health problems can cause physicians to acquire maladaptive coping strategies such as substance abuse and drug or alcohol dependence. However, it is important to note that physician impairment and substance abuse are not the most frequent causes of DPB. In fact, fewer than 10% of physician behavior issues have been related to substance abuse.2, 5

Psychiatric disorders such as major depression and bipolar and anxiety disorders may also contribute to DPB.10 Most of these disorders (except for schizophrenia) are likely as common among physicians as among the general public.9 An essential clarification is that although DPB can be a manifestation of personality disorders or psychiatric disorders, it does not always stem from underlying psychopathology. Clarifying these distinctions is important for managing the problem and calls for expert professional evaluation in some cases.10

A person’s behavior is shaped by character, values, perceptions, and attitudes. Individuals who engage in DPB typically lack insight and justify their behaviors as a means to achieve a goal. Disrespectful behavior is rooted, in part, in characteristics such as insecurity, immaturity, and aggressiveness; however, it can also be learned, tolerated, and reinforced in the hierarchical hospital culture.11

Other intrinsic factors that may contribute to DPB include lack of emotional intelligence, poor social skills, cultural and ethnic issues, and generation and gender bias.12 Identifying the root causes of DPB can be challenging due to the complexity of the interaction between the healthcare environment and the key players within it; nevertheless, awareness of the contributing factors and early recognition are important. Those who take on the mantle of leadership within hospitals should be educated in this regard.

Repercussions of Disruptive Physician Behavior

An institution’s organizational culture often has an impact on how DPB is addressed. Tolerance of such behavior can have far-reaching consequences. The central tenets of a “culture of safety and respect”–teamwork across disciplines and a blame-free environment in which every member of the healthcare team feels equally empowered to report errors and openly discuss safety issues–would be negatively impacted.

DPB can diminish the quality of care provided, increase the risk of medical errors, and adversely affect patient safety and satisfaction.11-13 Such behavior can cause erosion of relationships and communication between individuals and contribute to a hostile work environment. For instance, nurses or trainees may be afraid to question a physician because of the fear of getting yelled at or being humiliated. Consequently, improperly written orders may be overlooked or a potentially “wrong-site” surgical procedure may not be questioned for fear of provoking a hostile response.

DPB can increase litigation risk and financial costs to institutions. Provider retention may be adversely affected; valued staff may leave hospitals and need to be replaced, and productivity may suffer. When physicians in training observe how their superiors model disruptive behaviors with impunity, a concerning problem that arises is that DPB becomes normalized in the workplace culture, especially if such behaviors are tolerated and result in a perceived gain.

Proposed Interventions

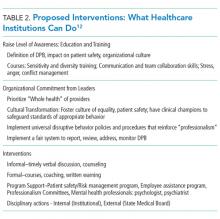

Confrontation of DPB can be challenging without appropriate infrastructure. Healthcare facilities should have a fair system in place for reliable reporting and monitoring of DPB, including a complaints’ verification process, appeals process, and an option for fair hearing.

It is best to initially address the issue in a direct, timely, yet informal manner through counseling or a verbal warning. In several situations, such informal counseling opportunities create a mindful awareness of the problem and the problematic behavior ceases without the need for further action.

When informal intervention is either not appropriate (eg, if the alleged event involved an assault or other illegal behavior) or has already been offered in the past, more formal intervention is required. Institutional progressive disciplinary polices should be in place and adhered to. For example, repeat offenders may be issued written warnings or even temporary suspension of privileges.

Institutional resources such as human resources departments, office of general counsel, office of medical affairs, and the hospital’s medical board may be consulted. Some medical centers have “employee assistance programs” staffed with clinicians skilled in dealing with DPB. Individuals diagnosed with substance abuse or a mental health disorder may require consultation with mental health professionals.14

Special “Professionalism Committees” can be instituted and tasked with investigating complaints and making recommendations for the involvement of resources outside the institution, such as a state medical society.15

Conclusion

Although the vast majority of physicians are well-behaved, it is important to acknowledge that disruptive behaviors can occur in the healthcare environment. Such behaviors have a major impact on workplace culture and patient safety and must be recognized early. Hospital executives and leaders must ensure that appropriate interventions are undertaken—before the quality of patient care is affected and before lives are endangered.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Ansu John for providing editorial assistance with the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose (Conflict of Interest Form submitted as separate PDF document). Dr. Heitt consults with local hospitals, medical practices, and licensing boards regarding physicians and other healthcare practitioners who have been accused of engaging in disruptive behavior. In these situations he may be paid by the board, medical society, hospital, practice or the professional (patient).

Dramatic stories of disruptive physician behavior (DPB) appear occasionally in the news, such as the physician who shot and killed a colleague within hospital confines or the gynecologist who secretly took photographs using a camera disguised as a pen during pelvic examinations. More common in hospitals, however, are incidents of inappropriate behavior that may generate complaints from patients or other providers and at times snowball into administrative or legal challenges.

“Professionalism” is one of the six competencies listed by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)1 and the American Board of Medical Specialties. Unfortunately, incidents of disruptive behavior can result in violation of the tenets of professionalism in the healthcare environment. These behaviors fall along a continuum ranging from outwardly aggressive and uncivil to overly passive and insidious. Although these behaviors can occur across all healthcare disciplines and settings and are not just limited to physicians, the behaviors of physicians often have a much greater impact on the healthcare system as a whole because of their positions of relative “power” within the system.2 Hence, this problem requires greater awareness and education. In this context, the aim of this article is to discuss disruptive behaviors in physicians

The AMA defines DPB as “personal conduct, verbal or physical that has the potential to negatively affect patient care or the ability to work with other members of the healthcare team.”3 The definition of DPB by the Joint Commission includes “all behaviors that undermine a culture of safety.”4 Both the Joint Commission and the AMA recognize the significance and patient safety implications of such behavior. Policy statements by both these organizations underscore the importance of confronting and remedying these potentially dangerous interpersonal behaviors.

Data regarding the prevalence of DPB have been inconsistent. One study estimated that 3%–5% of physicians demonstrate this behavior,5 whereas another study reported a DPB prevalence of 97% among physicians and nurses in the workplace.6 According to a 2004 survey of physician executives, more than 95% of them reported regular encounters of DPB.7

The etiology of such disruptive behaviors is multifactorial and complex. Explanations associated with ‘nature versus nurture’ have ranged from physician psychopathology to unhealthy modeling during training. Both extrinsic and intrinsic factors may also contribute to DPB. External stressors and negative experiences–professional and/or personal–can provoke disruptive behaviors. Overwork, fatigue, strife, and a dysfunctional environment that can arise in both work and home environments can contribute to the development of mental health problems. Stress, burnout, and depression have increasingly become prevalent among physicians and can play a significant role in causing impaired patterns of professional conduct.8, 9 These mental health problems can cause physicians to acquire maladaptive coping strategies such as substance abuse and drug or alcohol dependence. However, it is important to note that physician impairment and substance abuse are not the most frequent causes of DPB. In fact, fewer than 10% of physician behavior issues have been related to substance abuse.2, 5

Psychiatric disorders such as major depression and bipolar and anxiety disorders may also contribute to DPB.10 Most of these disorders (except for schizophrenia) are likely as common among physicians as among the general public.9 An essential clarification is that although DPB can be a manifestation of personality disorders or psychiatric disorders, it does not always stem from underlying psychopathology. Clarifying these distinctions is important for managing the problem and calls for expert professional evaluation in some cases.10

A person’s behavior is shaped by character, values, perceptions, and attitudes. Individuals who engage in DPB typically lack insight and justify their behaviors as a means to achieve a goal. Disrespectful behavior is rooted, in part, in characteristics such as insecurity, immaturity, and aggressiveness; however, it can also be learned, tolerated, and reinforced in the hierarchical hospital culture.11

Other intrinsic factors that may contribute to DPB include lack of emotional intelligence, poor social skills, cultural and ethnic issues, and generation and gender bias.12 Identifying the root causes of DPB can be challenging due to the complexity of the interaction between the healthcare environment and the key players within it; nevertheless, awareness of the contributing factors and early recognition are important. Those who take on the mantle of leadership within hospitals should be educated in this regard.

Repercussions of Disruptive Physician Behavior

An institution’s organizational culture often has an impact on how DPB is addressed. Tolerance of such behavior can have far-reaching consequences. The central tenets of a “culture of safety and respect”–teamwork across disciplines and a blame-free environment in which every member of the healthcare team feels equally empowered to report errors and openly discuss safety issues–would be negatively impacted.

DPB can diminish the quality of care provided, increase the risk of medical errors, and adversely affect patient safety and satisfaction.11-13 Such behavior can cause erosion of relationships and communication between individuals and contribute to a hostile work environment. For instance, nurses or trainees may be afraid to question a physician because of the fear of getting yelled at or being humiliated. Consequently, improperly written orders may be overlooked or a potentially “wrong-site” surgical procedure may not be questioned for fear of provoking a hostile response.

DPB can increase litigation risk and financial costs to institutions. Provider retention may be adversely affected; valued staff may leave hospitals and need to be replaced, and productivity may suffer. When physicians in training observe how their superiors model disruptive behaviors with impunity, a concerning problem that arises is that DPB becomes normalized in the workplace culture, especially if such behaviors are tolerated and result in a perceived gain.

Proposed Interventions

Confrontation of DPB can be challenging without appropriate infrastructure. Healthcare facilities should have a fair system in place for reliable reporting and monitoring of DPB, including a complaints’ verification process, appeals process, and an option for fair hearing.

It is best to initially address the issue in a direct, timely, yet informal manner through counseling or a verbal warning. In several situations, such informal counseling opportunities create a mindful awareness of the problem and the problematic behavior ceases without the need for further action.

When informal intervention is either not appropriate (eg, if the alleged event involved an assault or other illegal behavior) or has already been offered in the past, more formal intervention is required. Institutional progressive disciplinary polices should be in place and adhered to. For example, repeat offenders may be issued written warnings or even temporary suspension of privileges.

Institutional resources such as human resources departments, office of general counsel, office of medical affairs, and the hospital’s medical board may be consulted. Some medical centers have “employee assistance programs” staffed with clinicians skilled in dealing with DPB. Individuals diagnosed with substance abuse or a mental health disorder may require consultation with mental health professionals.14

Special “Professionalism Committees” can be instituted and tasked with investigating complaints and making recommendations for the involvement of resources outside the institution, such as a state medical society.15

Conclusion

Although the vast majority of physicians are well-behaved, it is important to acknowledge that disruptive behaviors can occur in the healthcare environment. Such behaviors have a major impact on workplace culture and patient safety and must be recognized early. Hospital executives and leaders must ensure that appropriate interventions are undertaken—before the quality of patient care is affected and before lives are endangered.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Ansu John for providing editorial assistance with the manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose (Conflict of Interest Form submitted as separate PDF document). Dr. Heitt consults with local hospitals, medical practices, and licensing boards regarding physicians and other healthcare practitioners who have been accused of engaging in disruptive behavior. In these situations he may be paid by the board, medical society, hospital, practice or the professional (patient).

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements: general competencies. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011[2].pdf. Accessed July 25, 2017.

2. Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: a persistent threat to patient safety. Patient safety and quality healthcare. Lionheart Publishing, Inc. 2006;3:16-24 https://www.psqh.com/julaug06/disruptive.html. Accessed October 1, 2017.

3. American Medical Association. Opinion E- 9.045–Physicians with disruptive behavior. Chicago, IL American Medical Association 2008.

4. Joint Commission: Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. Sentinel event alert, July 9, 2008:40. http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_40_behaviors_that_undermine_a_culture_of_safety/. Accessed October 1, 2017.

5. Leape LL, Fromson JA. Problem doctors: is there a system-level solution? Ann Int Med. 2006;144:107-115. PubMed

6. Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(8):464-471. PubMed

7. Weber DO. Poll Results: Doctors’ disruptive behavior disturbs physician leaders. The Physician Executive. 2004;30(5):6. PubMed

8. Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3161-3166. PubMed

9. Brown S, Goske M, Johnson C. Beyond substance abuse: stress, burnout and depression as causes of physician impairment and disruptive behavior. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009 6;(7):479-485. PubMed

10. Reynolds NT. Disruptive physician behavior: use and misuse of the label. J Med Regulation. 2012;98(1):8-19.

11. Leape LL, Shore MF, Dienstag JL, et al. Perspective: a culture of respect, part 1: the nature and causes of disrespectful behavior by physicians. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):845-852. PubMed

12. Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. Impact and implications of disruptive behavior in the perioperative arena. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(1):96-105. PubMed

13. Patient Safety Primer: Disruptive and unprofessional behavior. Available at AHRQ Patient Safety Network: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/15/disruptive-and-unprofessional-behavior(Accessed October 1, 2017.

14. Williams BW, Williams MV. The disruptive physician: conceptual organization. JMed Licensure Discipline. 2008;94(3):12-19.

15. Speck R, Foster J, Mulhem V, et al. Development of a professionalism committee approach to address unprofessional medical staff behavior at an academic medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2004;40(4):161-167. PubMed

1. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements: general competencies. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Common_Program_Requirements_07012011[2].pdf. Accessed July 25, 2017.

2. Porto G, Lauve R. Disruptive clinician behavior: a persistent threat to patient safety. Patient safety and quality healthcare. Lionheart Publishing, Inc. 2006;3:16-24 https://www.psqh.com/julaug06/disruptive.html. Accessed October 1, 2017.

3. American Medical Association. Opinion E- 9.045–Physicians with disruptive behavior. Chicago, IL American Medical Association 2008.

4. Joint Commission: Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. Sentinel event alert, July 9, 2008:40. http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_40_behaviors_that_undermine_a_culture_of_safety/. Accessed October 1, 2017.

5. Leape LL, Fromson JA. Problem doctors: is there a system-level solution? Ann Int Med. 2006;144:107-115. PubMed

6. Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. A survey of the impact of disruptive behaviors and communication defects on patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(8):464-471. PubMed

7. Weber DO. Poll Results: Doctors’ disruptive behavior disturbs physician leaders. The Physician Executive. 2004;30(5):6. PubMed

8. Center C, Davis M, Detre T, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3161-3166. PubMed

9. Brown S, Goske M, Johnson C. Beyond substance abuse: stress, burnout and depression as causes of physician impairment and disruptive behavior. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009 6;(7):479-485. PubMed

10. Reynolds NT. Disruptive physician behavior: use and misuse of the label. J Med Regulation. 2012;98(1):8-19.

11. Leape LL, Shore MF, Dienstag JL, et al. Perspective: a culture of respect, part 1: the nature and causes of disrespectful behavior by physicians. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):845-852. PubMed

12. Rosenstein AH, O’Daniel M. Impact and implications of disruptive behavior in the perioperative arena. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(1):96-105. PubMed

13. Patient Safety Primer: Disruptive and unprofessional behavior. Available at AHRQ Patient Safety Network: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/15/disruptive-and-unprofessional-behavior(Accessed October 1, 2017.

14. Williams BW, Williams MV. The disruptive physician: conceptual organization. JMed Licensure Discipline. 2008;94(3):12-19.

15. Speck R, Foster J, Mulhem V, et al. Development of a professionalism committee approach to address unprofessional medical staff behavior at an academic medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2004;40(4):161-167. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine