User login

2016 Update on female sexual dysfunction

The age-adjusted prevalence of any sexual problem is 43% among US women. A full 22% of these women experience sexually related personal distress.1 With publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition2 has come a shift in classification and, at times, management approach for reported female sexual dysfunction. When women report to their clinicians decreased sexual desire or arousal or pain at penetration, the management is no longer guided by a linear model of sexual response (excitation, plateau, orgasm, and resolution) but rather by a more nuanced and complex biopsychosocial approach. In this model, diagnosis and management strategies to address bothersome sexual concerns consider the whole woman in the context of her physical and psychosocial health. The patient’s age, medical history, and relationship status are among the factors that could affect management of the problem. In an effort to explore this management approach, I used this Update on Female Sexual Dysfunction as an opportunity to convene a roundtable of several experts, representing varying backgrounds and practice vantage points, to discuss 5 cases of sexual problems that you as a busy clinician may encounter in your practice.

Genital atrophy in a sexually inactive 61-year-old woman

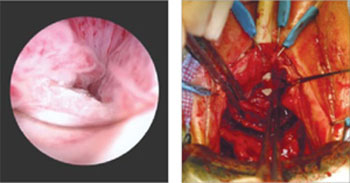

Barbara S. Levy, MD: Two years after her husband's death, which followed several years of illness, your 61-year-old patient mentions at her well woman visit that she anticipates becoming sexually active again. She has not used systemic or vaginal hormone therapy. During pelvic examination, atrophic external genital changes are present, and use of an ultrathin (thinner than a Pederson) speculum reveals vaginal epithelial atrophic changes. A single-digit bimanual exam can be performed with moderate patient discomfort; the patient cannot tolerate a 2-digit bimanual exam. She expresses concern about being able to engage in penile/vaginal sexual intercourse.

Dr. Kaunitz, what is important for you to ask this patient, and what concerns you most on her physical exam?

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD: First, it is important to recognize the patient's expectations and desires. As the case suggests, but further questioning could clarify, she would like to be able to comfortably engage in sexual intercourse with a new partner, but penetration may be difficult (and definitely painful for her) unless treatment is pursued. This combination of mucosal and vestibular atrophic changes (genitourinary syndrome of menopause [GSM], or vulvovaginal atrophy [VVA]) plus the absence of penetration for many years can be a double whammy situation for menopausal women. In this case it has led to extensive contracture of the introitus, and if it is not addressed will cause sexual dysfunction.

Dr. Levy: In addition we need to clarify whether or not a history of breast cancer or some other thing may impact the care we provide. How would you approach talking with this patient in order to manage her care?

Dr. Kaunitz: One step is to see how motivated she is to address this, as it is not something that, as gynecologists, we can snap our fingers and the situation will be resolved. If the patient is motivated to treat the atrophic changes with medical treatment, in the form of low-dose vaginal estrogen, and dilation, either on her own if she's highly motivated to do so, or in my practice more commonly with the support of a women's physical therapist, over time she should be able to comfortably engage in sexual intercourse with penetration. If this is what she wants, we can help steer her in the right direction.

Sheryl Kingsberg, PhD: You know that this woman is motivated by virtue of her initiating the topic herself. Patients are often embarrassed talking about sexual issues, or they are not sure that their gynecologist is comfortable with it. After all, they think, if this is the right place to discuss sexual problems, why didn't he or she ask me? Clinicians must be aware that it is their responsibility to ask about sexual function and not leave it for the patient to open the door.

Dr. Kaunitz: Great point.

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD: Gratefully, a lot of the atrophic changes this patient demonstrates are reversible. However, other autoimmune diseases (eg, lichen planus, which can affect the vaginal epithelium, or lichen sclerosus, which can affect the clitoris, labia, and vulva) can also cause constriction, and in severe cases, complete obliteration of the vagina and introitus. Women may not be sexually active, and for each annual exam their clinician uses a smaller and smaller speculum--to the point that they cannot even access the cervix anymore--and the vagina can close off. Clinicians may not realize that you need something other than estrogen; with lichen planus you need steroid suppository treatment, and with lichen sclerosus you need topical steroid treatment. So these autoimmune conditions should also be in the differential and, with appropriate treatment, the sexual effects can be reversible.

Michael Krychman, MD: I agree. The vulva can be a great mimicker and, according to the history and physical exam, at some point a vulvoscopy, and even potential biopsies, may be warranted as clinically indicated.

The concept of a comprehensive approach, as Dr. Kingsberg had previously mentioned, involves not only sexual medicine but also evaluating the patient's biopsychosocial variables that may impact her condition. We also need to set realistic expectations. Some women may benefit from off-label use of medications besides estrogen, including topical testosterone. Informed consent is very important with these treatments. I also have had much clinical success with intravaginal diazepam/lorazepam for pelvic floor hypertonus.

In addition, certainly I agree that pelvic floor physical therapy (PT) is a vital treatment component for this patient and, not to diminish its importance, but many women cannot afford, nor do they have the time or opportunity, to go to pelvic floor PT. As clinicians, we can develop and implement effective programs, even in the office, to educate the patient to help herself as well.

Dr. Kaunitz: Absolutely. Also, if, in a clinical setting consistent with atrophic changes, an ObGyn physician is comfortable that vulvovaginal changes noted on exam represent GSM/atrophic changes, I do not feel vulvoscopy is warranted.

Dr. Levy: In conclusion, we need to be aware that pelvic floor PT may not be available everywhere and that a woman's own digits and her partner can also be incorporated into this treatment.

Something that we have all talked about in other venues, but have not looked at in the larger sphere here, is whether there is value to seeing women annually and performing pelvic exams. As Dr. Kingsberg mentioned, this is a highly motivated patient. We have many patients out there who are silent sufferers. The physical exam is an opportunity for us to recognize and address this problem.

Dyspareunia and low sexual desire in a breast cancer survivor

Dr. Levy: In this case, a 36-year-old woman with BRCA1−positive breast cancer has vaginal dryness, painful intercourse, and lowered sexual interest since her treatment, which included chemotherapy after bilateral mastectomies. She has a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy(BSO) scheduled for primary prevention of her ovarian cancer risk.

Dr. Kingsberg, what is important for you to know to help guide case management?

Dr. Kingsberg: This woman is actually presenting with 2 sexual problems: dyspareunia, which is probably secondary to VVA or GSM, and low sexual desire. Key questions are: 1) When was symptom onset--acquired after treatment or lifelong? 2) Did she develop the dyspareunia and as a result of having pain during sex lost desire to have sex? Or, did she lose desire and then, without it, had no arousal and therefore pain with penetration developed? It also could be that she has 2 distinct problems, VVA and hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), in which case you need to think about treating both. Finally, we do not actually know if she is having penetrative intercourse or even if she has a partner.

A vulvovaginal exam would give clues as to whether she has VVA, and hormone levels would indicate if she now has chemo-induced menopause. If she is not in menopause now, she certainly is going to be with her BSO. The hormonal changes due to menopause actually can be primarily responsible for both the dyspareunia and HSDD. Management of both symptoms really needs to be based on shared decision making with the patient--with which treatment for which conditions coming first, based on what is causing her the most distress.

I would encourage this woman to treat her VVA since GSM does have long-term physiologic consequences if untreated. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends nonhormonal treatments as first-line treatments, with vaginal estrogen considered if these therapies fail.3 If lubricants and moisturizers and other nonhormonal options are not sufficient, you could consider local estrogen, even though she is a breast cancer survivor, as well as ospemiphene.

If she is distressed by her loss of sexual desire, you can choose to treat her for HSDD. Flibanserin is the first FDA-approved treatment for HSDD. It is only approved in premenopausal women, so it would be considered off-label use if she is postmenopausal (even though she is quite young). You also could consider exogenous testosterone off-label, after consulting with her oncologist.

In addition to the obvious physiologic etiology of her pain and her low desire, the biopsychosocial aspects to consider are: 1) changes to her body image, as she has had bilateral mastectomies, 2) her anxiety about the cancer diagnosis, and 3) concerns about her relationship if she has one--her partner's reactions to her illness and the quality of the relationship outside the bedroom.

Dr. Iglesia: I am seeing here in our nation's capital a lot of advertisements for laser therapy for GSM. I caution women about this because providers are charging a lot of money for this therapy when we do not have long-term safety and effectiveness data for it.

Our group is currently conducting a randomized controlled trial, looking at vaginal estrogen cream versus laser therapy for GSM here at Medstar Health--one of the first in the country as part of a multisite trial. But the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) has come out with a pretty strong statement,4 as has ACOG,5 on this therapy, and I caution people about overzealously offering a very costly procedure targeted to a very vulnerable population, especially to women with personal histories of estrogen-sensitive cancers.

Dr. Krychman: I agree. Very often cancer patients are preyed upon by those offering emerging unproven technologies or medications. We have to work as a coordinated comprehensive team, whether it's a sexual medicine expert, psychologist, urogynecologist, gynecologist, or oncologist, and incorporate the patient's needs and expectations and risk tolerance coupled with treatment efficacy and safety.

Dr. Levy: This was a complex case. The biopsychosocial model is critical here. It's important that we are not siloes in our medical management approach and that we try to help this patient embrace the complexity of her situation. It's not only that she has cancer at age 36; there is a possible guilt factor if she has children and passed that gene on.

Another point that we began to talk about is the fact that in this country we tend to be early adopters of new technology. In our discussion with patients, we should focus on what we know and the risk of the unknowns related to some of the treatment options. But let's discuss lasers a little more later on.

Diminished arousal and orgasmic intensity in a patient taking SSRIs

Dr. Levy: In this next case, a 44-year-old woman in a 15-year marriage notices a change in her orgasmic intensity and latency. She has a supportive husband, and they are attentive to each other's sexual needs. However, she notices a change in her arousal and orgasmic intensity, which has diminished over the last year. She reports that the time to orgasm or latency has increased and both she and her partner are frustrated and getting concerned. She has a history of depression that has been managed by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the past 5 years and has no depressive symptoms currently.

Dr. Krychman, what are you considering before beginning to talk with this patient?

Dr. Krychman: My approach really is a comprehensive one, looking not only at the underlying medical issues but also at the psychological and dynamic relationship facets. We of course also want to look at medications: Has she changed her dose or the timing of when she takes it? Is this a new onset? Finally, we want to know why this is coming to the forefront now. Is it because it is getting worse, or is it because there is some significant issue that is going on in the relationship?

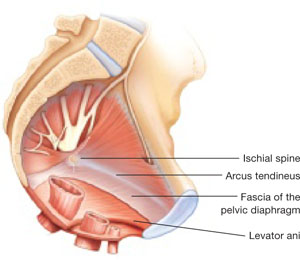

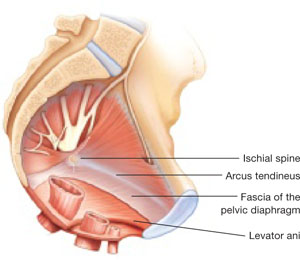

Regarding the physical exam, it is important to rule out underlying genital pelvic pathology. Young women can get changes in the integrity of the pelvic floor, in what I would call the orgasmic matrix--the clitoral tissue, the body, the crura (or arms of the clitoris)--we want to examine and be reassured that her genital anatomy is normal and that there is no underlying pathology that could signal an underlying abnormal hormonal profile. Young women certainly can get lowered estrogen effects at the genital/pelvic tissues (including the labia and vulva), and intravaginally as well. Sometimes women will have pelvic floor hypertonus, as we see with other urinary issues. A thorough pelvic exam is quite vital.

Let's not forget the body that is attached to the genitals; we want to rule out chronic medical disease that may impact her: hypertension, diabetes, or hypercholesterolemia. Untreated, these conditions may directly impact the arousal physiologic mechanisms.

Dr. Levy: In doing this patient's physical exam I would be looking for significant weight gain, and even asking about her partner's weight. Body image can be a huge issue. If she has a history of depression, if she is suffering from a body image problem, she can be feeling unattractive. In my experience this can be a common thing to affect women in their mid-40s.

How would you manage this case?

Dr. Krychman: It is important to divide it up in terms of a conservative to aggressive approach. We want to find out about the relationship. For instance, is the sexual dynamic scripted (ie, boring and predictable)? Is she distracted and frustrated or is she getting enough of the type of stimulation that she likes and enjoys? There certainly are a lot of new devices that are available, whether a self-stimulator or vibrator, the Fiera, or other stimulating devices, that may be important to incorporate into the sexual repertoire. If there is underlying pathology, we want to evaluate and treat that. She may need to be primed, so to speak, with systemic hormones. And does she have issues related to other effects of hormonal deprivation, even local effects? Does she have clitoral atrophy?

There are neutraceuticals that are currently available, whether topical arousal gels or ointments, and we as clinicians need to be critical and evaluate their benefit/risk and look at the data concerning these products. In addition, women who have changes in arousal and in orgasmic intensity and latency may be very frustrated. They describe it as climbing up to a peak but never getting over the top, and this frustration may lead to participant spectatoring, so incorporating a certified sex therapist or counselor is sometimes very critical.

Finally, there are a lot of snake oils, charmers, and charlatan unproven procedures--injecting fillers or other substances into the clitoris are a few examples. I would be a critical clinician, examine the evidence, look at the benefit/risk before advocating an intervention that does not have good clinical data to support its use--a comprehensive approach of sexual medicine as well as sexual psychology.

Dr. Kingsberg: Additionally, we know she is in a long-term relationship--15 years; we want to acknowledge the partner. We talked about the partner's weight, but what about his erectile function? Does he have changes in sexual function that are affecting her, and she is the one carrying the "symptom"?

Looking at each piece separately helps a clinician from getting overwhelmed by the patient who comes in reporting distress with orgasmic dysfunction. We have no pharmacologic FDA-approved treatments, so it can feel off-putting for a clinician to try to fix the reported issue. Looking at each component to help her figure out the underlying cause can be helpful.

Dr. Iglesia: With aging, there can be changes in blood flow, not to mention the hormonal and even peripheral nerve changes, that require more stimulation in order to achieve the desired response. I echo concern about expensive procedures being offered with no evidence, such as the "O" or "G" shot, that can cost up to thousands of dollars.

The other procedure that gives me a lot of angst is clitoral unhooding. The 3 parts of the clitoris are sensitive in terms of innervation and blood flow, and cutting around that delicate tissue goes against the surgical principles required for preserving nerves and blood flow.

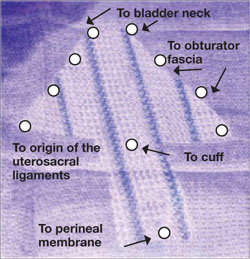

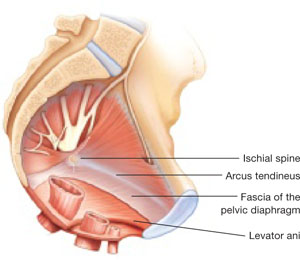

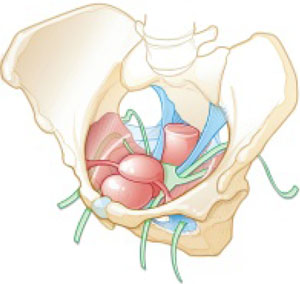

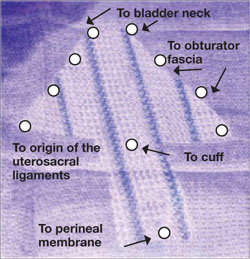

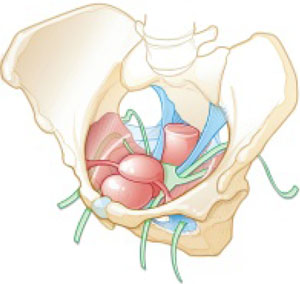

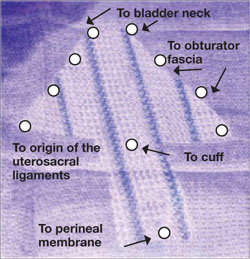

New onset pain post−prolapse surgery with TOT sling placement

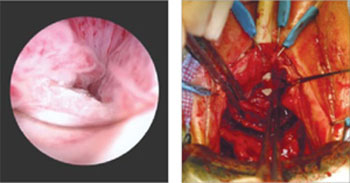

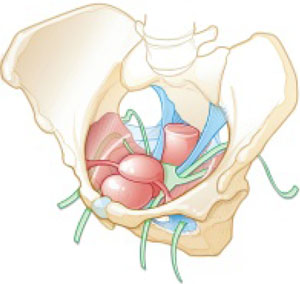

Dr. Levy: For this case, let's consider a 42-year-old woman (P3) who is 6 months post− vaginal hysterectomy. The surgery included ovarian preservation combined with anterior and posterior repair for prolapse as well as apical uterosacral ligament suspension for stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse. A transobturator sling was used.

Extensive preop evaluation was performed, with confirmed symptomatic prolapse. She had no stress incontinence symptoms but did have confirmed occult stress incontinence.

Surgery was uneventful. She resumed intercourse at 8 weeks, but she now has pain with both initial entry and deep penetration. Lubricants and changes in position have not helped. She is in a stable relationship with her husband of 17 years, and she is worried that the sling mesh might be the culprit. On exam, she has no atrophy, pH is 4.5, vaginal length is 8 cm, and there is no prolapse. There is no mesh exposure noted, although she reports slight tenderness with palpation of the right sling arm beneath the right pubic bone.

Dr. Iglesia, what are the patient history questions important to ask here?

Dr. Iglesia: This is not an uncommon scenario--elective surgical correction of occult or latent stress incontinence after surgical correction for pelvic organ prolapse. Now this patient here has no more prolapse complaints; however, she has a new symptom. There are many different causes of dyspareunia; we cannot just assume it is the sling mesh (although with all the legal representation advertisements for those who have had mesh placed, it can certainly be at the top of the patient's mind, causing anxiety and fear).

Multiple trials have looked at prophylactic surgery for incontinence at the time of prolapse repairs. This woman happened to be one of those patients who did not have incontinence symptoms, and they put a sling in. A recent large trial examined women with vaginal prolapse who underwent hysterectomy and suspension.6 (They compared 2 different suspensions.) What is interesting is that 25% of women with prolapse do have baseline pain. However, at 24 months, de novo pain can occur in 10% of women--just from the apical suspension. So, here, it could be the prolapse suspension. Or, in terms of the transobturator sling, long-term data do tell us that the de novo dyspareunia rate ranges on the magnitude of 1% to 9%.7 What is important here is figuring out the cause of the dyspareunia.

Dr. Levy: One of the important points you raised already was that 25% of these women have preoperative pain. So figuring out what her functioning was before surgery and incorporating that into our assessment postop would be pretty important I would think.

Dr. Iglesia: Yes, you need to understand what her typical encounter was before the surgery and how things have changed now that the prolapse is not in the way. Changes obviously can occur with scar tissue, which over time will improve. If she is perimenopausal and starts to get epithelial changes, we can fix that. The question then becomes, "Is the pain emanating from the mesh?"

When examining this patient, it is not uncommon for me to be able to feel "banjo" strings if the mesh is too tight or close to the surface. It is not exposed but it's palpable, and the patient may feel a ridge during penetration. You can ask the patient if pain occurs with different penetration positions. In addition, explore associated neurologic symptoms (numbness or muscle pain in the thigh).

Dr. Kingsberg: There were 2 different sources of pain--on initial entry and at deep penetration. You want to make sure you address both. Importantly, did one precede the other? For instance, if women have pain with penetration they can then end up with an arousal disorder (the length of the vagina cannot increase as much as it might otherwise) and dystonia secondary to the pain with penetration. The timing of the pain--did it all happen at the same time, or did she start out with pain at one point and did it move to something else--is another critical piece of the history.

Dr. Iglesia: It does take a detailed history and physical exam to identify myofascial trigger points. In this case there seems to be pinpoint tenderness directly on the part of the mesh that is not exposed on the right. There are people who feel you should remove the whole mesh, including the arms. Others feel, okay, we can work on these trigger points, with injections, physical therapy, extra lubrication, and neuromodulatory medications. Only then would they think about potentially excising the sling or a portion thereof.

Dr. Krychman: Keep in mind that, even if you do remove the sling, her pain may not subside, if it is secondary to an underlying issue. Because of media sensationalism, she could be focusing on the sling. It is important to set realistic expectations. I often see vulvar pathology or even provoked vestibulodynia that can present with a deep dyspareunia. The concept of collision dyspareunia or introital discomfort or pain on insertion has far reaching implications. We need to look at the patient in totality, ruling out underlying issues related to the bladder, even the colon.

Patient inquires about the benefits of laser treatment for vaginal health

Dr. Levy: Let's move to this last case: A 47-year-old patient who reports lack of sexual satisfaction and attributes it to a loose vagina says, "I've heard about surgery and laser treatment and radiofrequency devices for vaginal health. What are the benefits and risks of these procedures, and will they correct the issues that I'm experiencing?"

How do you approach this patient?

Dr. Krychman: I want to know why this is of paramount importance to her. Is this her actual complaint or is it society's unrealistic expectation of sexual pleasure and performance placed upon her? Or is this a relationship issue surfacing, compounded by physiologic changes? With good communication techniques, like "ask, tell, ask" or effective use of silence (not interrupting), patients will lead us to the reason and the rationale.

Dr. Levy: I have seen a lot of advertising to women, now showing pictures of genitalia, perhaps creating an expectation that we should look infantile in some way. We are creating a sense of beauty and acceptablevisualization of the vagina and vulva that are completely unrealistic. It's fascinating on one hand but it is also disturbing in that some of the direct-to-consumer marketing going on is creating a sense of unease in women who are otherwise perfectly satisfied. Now they take a look at their sagging skin, maybe after having 2 or 3 children, and although they may not look the same they function not so badly perhaps. I think we are creating a distress and an illness model that is interesting to discuss.

Dr. Iglesia, you are in the midst of a randomized trial, giving an informed consent to participants about the expectations for this potential intervention. How do you explain to women what these laser and radiofrequency devices are expected to do and why they might or might not work?

Dr. Iglesia: We are doing a randomized trial for menopausal women who have GSM. We are comparing estrogen cream with fractional CO2 laser therapy. I also am involved in another randomized trial for lichen sclerosus. I am not involved in the cosmetic use of a laser for people who feel their vaginas are just "loose." Like you, Dr. Levy, I am very concerned about the images that women are seeing of the idealized vulva and vagina, and about the rise of cosmetic gynecology, much of which is being performed by plastic surgeons or dermatologists.

A recent article looked at the number of women who are doing pubic hair grooming; the prevalance is about 80% here in America.8 So people have a clear view of what is down there, and then they compare it to what they see in pornographic images on the Internet and want to look like a Barbie doll. That is disturbing because women, particularly young women, do not realize what happens with GSM changes to the vulva and vagina. On the other hand, these laser machines are very expensive, and some doctors are charging thousands of dollars and promising cosmetic and functional results for which we lack long-term, comparative data.

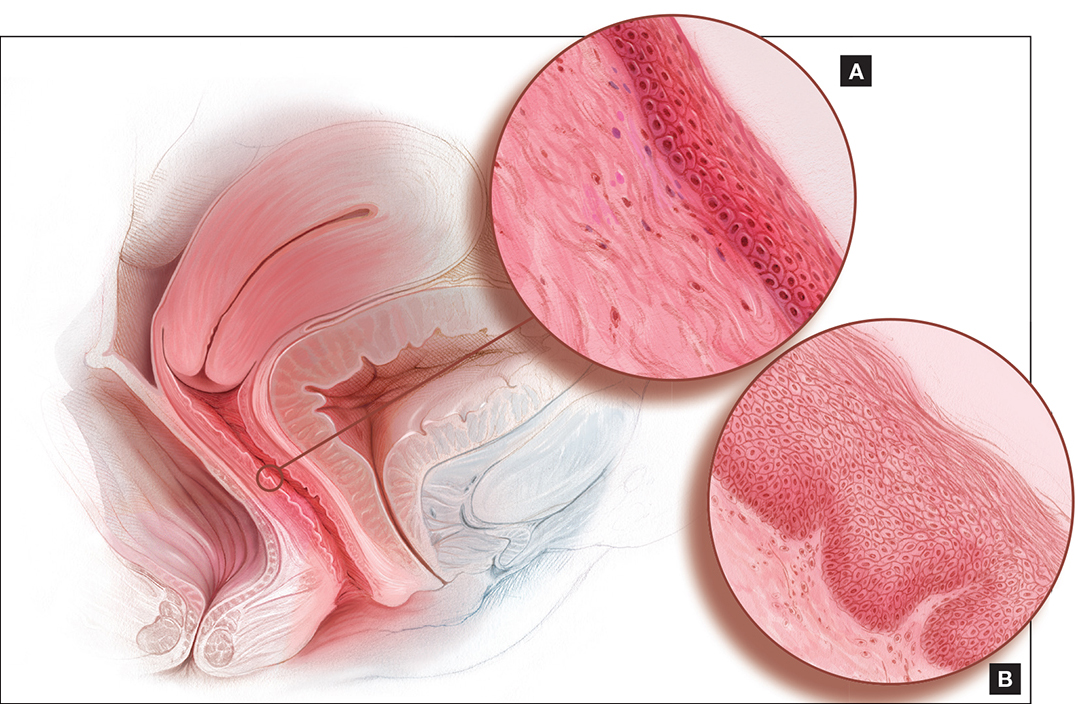

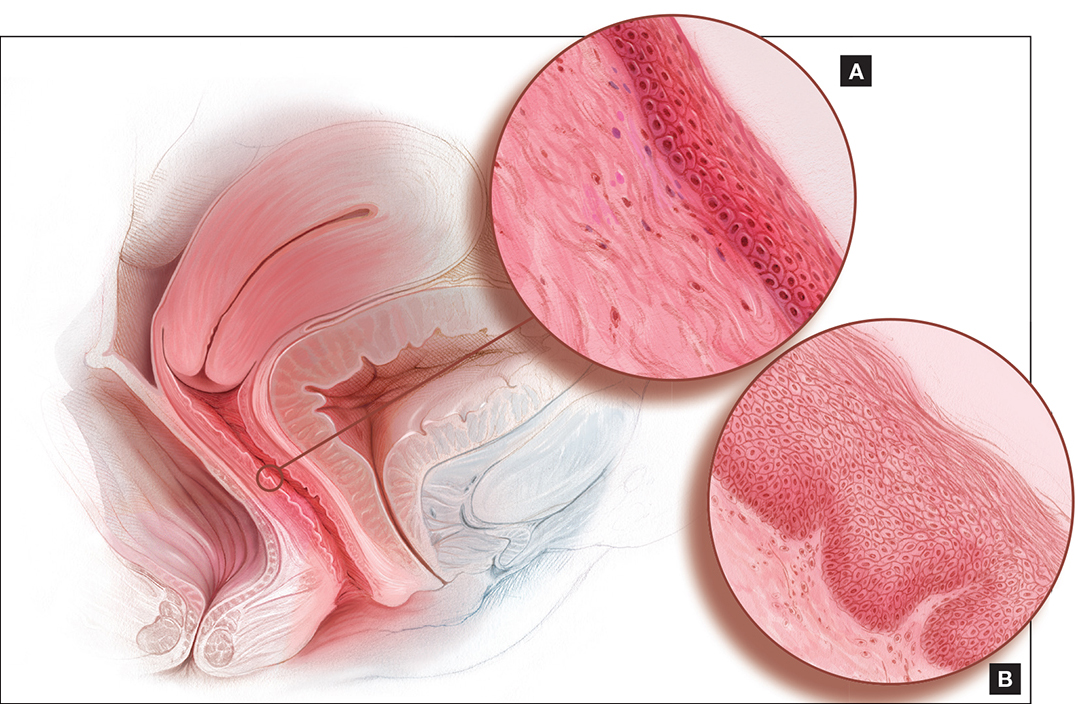

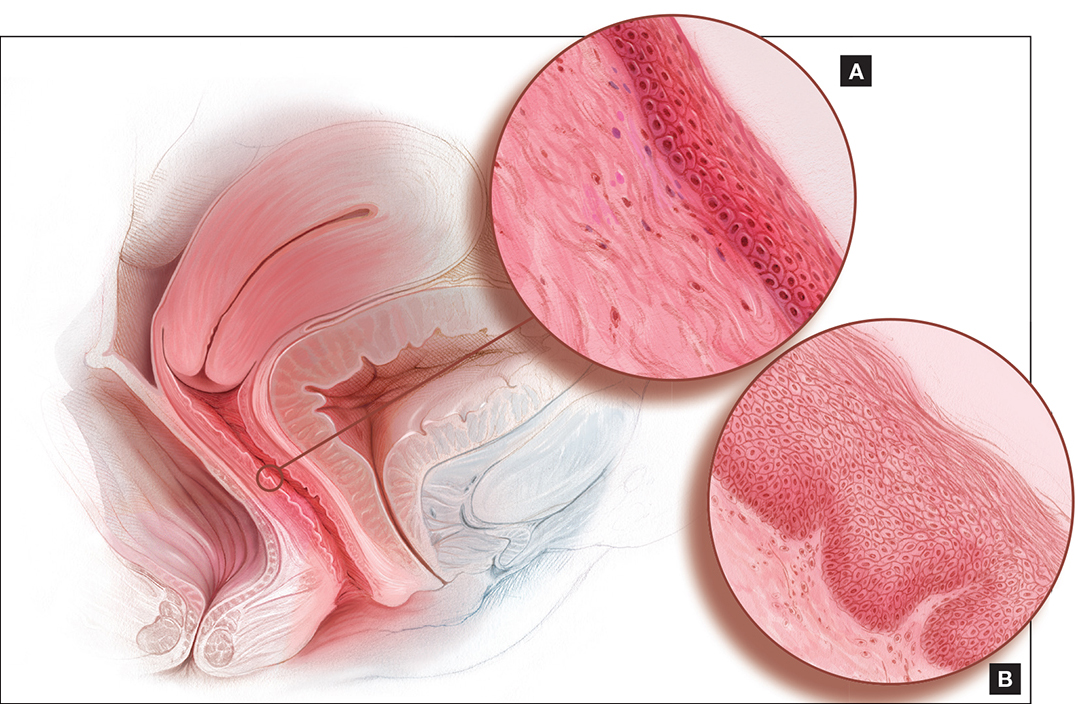

The laser that we are studying is one by Cynosure called Mona Lisa, which works with fractional CO2 and has very low depth of penetration. The concept is that, with microdot therapy (on the order of micrometers), pinpoint destruction will foster regeneration of new collagen and blood flow to the vagina and vulva. We are still in the midst of analyzing this.

Dr. Krychman: I caution people not to lump devices together. There is a significant difference between laser and radiofrequency--especially in the depth of tissue penetration, and level of evidence as well. There are companies performing randomized clinical trials, with well designed sham controls, and have demonstrated clinical efficacy. We need to be cautious of a procedure that is saying it's the best thing since sliced bread, curing interstitial cystitis, dyspareunia, and lichen sclerosus and improving orgasm, lubrication, and arousal. These far reaching, off-label claims are concerning and misleading.

Dr. Levy: I think the important things are 1) shared decision making with the patient and 2) disclosure of what we do not know, which are the long-term results and outcomes and possible downstream negative effects of some of these treatments, since the data we have are so short term.

Dr. Kingsberg: Basics are important. You talked about the pressure for cosmetic appearance, but is that really what is going on for this particular patient? Is she describing a sexual dysfunction when she talks about lack of satisfaction? You need to operationally define that term. Does she have problems with arousal or orgasm or desire and those are what underlie her lack of satisfaction? Is the key to management helping her come to terms with body image issues or to treat a sexual dysfunction? If it truly is a sexual dysfunction, then you can have the shared decision making on preferred treatment approach.

Dr. Levy: This has been an enlightening discussion. Thank all of you for your expertise and clinical acumen.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, Segreti A, Johannes CB. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):970−978.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Arlington, VA; 2013.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Gynecologic Practice, Farrell R. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 659: The Use of Vaginal Estrogen in Women With a History of Estrogen-Dependent Breast Cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(3):e93−e96.

- Krychman ML, Shifren JL, Liu JH, Kingsberg SL, Utian WH. The North American Menopause Society (NAMS). NAMS Menopause e-Consult: Laser treatment safe for vulvovaginal atrophy? 2015;11(3). http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/846960. Accessed August 17, 2016.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Fractional laser treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy and U.S. Food and Drug Administration clearance: Position Statement. http://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Position-Statements/Fractional-Laser-Treatment-of-Vulvovaginal-Atrophy-and-US-Food-and-Drug-Administration-Clearance. Published May 2016. Accessed August 17, 2016.

- Lukacz ES, Warren LK, Richter HE, et al. Quality of life and sexual function 2 years after vaginal surgery for prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(6):1071−1079.

- Brubaker L, Chiang S, Zyczynski H, et al. The impact of stress incontinence surgery on female sexual function. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(5):562.e1.

- Rowen TS, Gaither TW, Awad MA, Osterberg EC, Shindel AW, Breyer BN. Pubic hair grooming prevalence and motivation among women in the United States [published online ahead of print June 29, 2016]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamader matol.2016.2154.

The age-adjusted prevalence of any sexual problem is 43% among US women. A full 22% of these women experience sexually related personal distress.1 With publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition2 has come a shift in classification and, at times, management approach for reported female sexual dysfunction. When women report to their clinicians decreased sexual desire or arousal or pain at penetration, the management is no longer guided by a linear model of sexual response (excitation, plateau, orgasm, and resolution) but rather by a more nuanced and complex biopsychosocial approach. In this model, diagnosis and management strategies to address bothersome sexual concerns consider the whole woman in the context of her physical and psychosocial health. The patient’s age, medical history, and relationship status are among the factors that could affect management of the problem. In an effort to explore this management approach, I used this Update on Female Sexual Dysfunction as an opportunity to convene a roundtable of several experts, representing varying backgrounds and practice vantage points, to discuss 5 cases of sexual problems that you as a busy clinician may encounter in your practice.

Genital atrophy in a sexually inactive 61-year-old woman

Barbara S. Levy, MD: Two years after her husband's death, which followed several years of illness, your 61-year-old patient mentions at her well woman visit that she anticipates becoming sexually active again. She has not used systemic or vaginal hormone therapy. During pelvic examination, atrophic external genital changes are present, and use of an ultrathin (thinner than a Pederson) speculum reveals vaginal epithelial atrophic changes. A single-digit bimanual exam can be performed with moderate patient discomfort; the patient cannot tolerate a 2-digit bimanual exam. She expresses concern about being able to engage in penile/vaginal sexual intercourse.

Dr. Kaunitz, what is important for you to ask this patient, and what concerns you most on her physical exam?

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD: First, it is important to recognize the patient's expectations and desires. As the case suggests, but further questioning could clarify, she would like to be able to comfortably engage in sexual intercourse with a new partner, but penetration may be difficult (and definitely painful for her) unless treatment is pursued. This combination of mucosal and vestibular atrophic changes (genitourinary syndrome of menopause [GSM], or vulvovaginal atrophy [VVA]) plus the absence of penetration for many years can be a double whammy situation for menopausal women. In this case it has led to extensive contracture of the introitus, and if it is not addressed will cause sexual dysfunction.

Dr. Levy: In addition we need to clarify whether or not a history of breast cancer or some other thing may impact the care we provide. How would you approach talking with this patient in order to manage her care?

Dr. Kaunitz: One step is to see how motivated she is to address this, as it is not something that, as gynecologists, we can snap our fingers and the situation will be resolved. If the patient is motivated to treat the atrophic changes with medical treatment, in the form of low-dose vaginal estrogen, and dilation, either on her own if she's highly motivated to do so, or in my practice more commonly with the support of a women's physical therapist, over time she should be able to comfortably engage in sexual intercourse with penetration. If this is what she wants, we can help steer her in the right direction.

Sheryl Kingsberg, PhD: You know that this woman is motivated by virtue of her initiating the topic herself. Patients are often embarrassed talking about sexual issues, or they are not sure that their gynecologist is comfortable with it. After all, they think, if this is the right place to discuss sexual problems, why didn't he or she ask me? Clinicians must be aware that it is their responsibility to ask about sexual function and not leave it for the patient to open the door.

Dr. Kaunitz: Great point.

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD: Gratefully, a lot of the atrophic changes this patient demonstrates are reversible. However, other autoimmune diseases (eg, lichen planus, which can affect the vaginal epithelium, or lichen sclerosus, which can affect the clitoris, labia, and vulva) can also cause constriction, and in severe cases, complete obliteration of the vagina and introitus. Women may not be sexually active, and for each annual exam their clinician uses a smaller and smaller speculum--to the point that they cannot even access the cervix anymore--and the vagina can close off. Clinicians may not realize that you need something other than estrogen; with lichen planus you need steroid suppository treatment, and with lichen sclerosus you need topical steroid treatment. So these autoimmune conditions should also be in the differential and, with appropriate treatment, the sexual effects can be reversible.

Michael Krychman, MD: I agree. The vulva can be a great mimicker and, according to the history and physical exam, at some point a vulvoscopy, and even potential biopsies, may be warranted as clinically indicated.

The concept of a comprehensive approach, as Dr. Kingsberg had previously mentioned, involves not only sexual medicine but also evaluating the patient's biopsychosocial variables that may impact her condition. We also need to set realistic expectations. Some women may benefit from off-label use of medications besides estrogen, including topical testosterone. Informed consent is very important with these treatments. I also have had much clinical success with intravaginal diazepam/lorazepam for pelvic floor hypertonus.

In addition, certainly I agree that pelvic floor physical therapy (PT) is a vital treatment component for this patient and, not to diminish its importance, but many women cannot afford, nor do they have the time or opportunity, to go to pelvic floor PT. As clinicians, we can develop and implement effective programs, even in the office, to educate the patient to help herself as well.

Dr. Kaunitz: Absolutely. Also, if, in a clinical setting consistent with atrophic changes, an ObGyn physician is comfortable that vulvovaginal changes noted on exam represent GSM/atrophic changes, I do not feel vulvoscopy is warranted.

Dr. Levy: In conclusion, we need to be aware that pelvic floor PT may not be available everywhere and that a woman's own digits and her partner can also be incorporated into this treatment.

Something that we have all talked about in other venues, but have not looked at in the larger sphere here, is whether there is value to seeing women annually and performing pelvic exams. As Dr. Kingsberg mentioned, this is a highly motivated patient. We have many patients out there who are silent sufferers. The physical exam is an opportunity for us to recognize and address this problem.

Dyspareunia and low sexual desire in a breast cancer survivor

Dr. Levy: In this case, a 36-year-old woman with BRCA1−positive breast cancer has vaginal dryness, painful intercourse, and lowered sexual interest since her treatment, which included chemotherapy after bilateral mastectomies. She has a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy(BSO) scheduled for primary prevention of her ovarian cancer risk.

Dr. Kingsberg, what is important for you to know to help guide case management?

Dr. Kingsberg: This woman is actually presenting with 2 sexual problems: dyspareunia, which is probably secondary to VVA or GSM, and low sexual desire. Key questions are: 1) When was symptom onset--acquired after treatment or lifelong? 2) Did she develop the dyspareunia and as a result of having pain during sex lost desire to have sex? Or, did she lose desire and then, without it, had no arousal and therefore pain with penetration developed? It also could be that she has 2 distinct problems, VVA and hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), in which case you need to think about treating both. Finally, we do not actually know if she is having penetrative intercourse or even if she has a partner.

A vulvovaginal exam would give clues as to whether she has VVA, and hormone levels would indicate if she now has chemo-induced menopause. If she is not in menopause now, she certainly is going to be with her BSO. The hormonal changes due to menopause actually can be primarily responsible for both the dyspareunia and HSDD. Management of both symptoms really needs to be based on shared decision making with the patient--with which treatment for which conditions coming first, based on what is causing her the most distress.

I would encourage this woman to treat her VVA since GSM does have long-term physiologic consequences if untreated. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends nonhormonal treatments as first-line treatments, with vaginal estrogen considered if these therapies fail.3 If lubricants and moisturizers and other nonhormonal options are not sufficient, you could consider local estrogen, even though she is a breast cancer survivor, as well as ospemiphene.

If she is distressed by her loss of sexual desire, you can choose to treat her for HSDD. Flibanserin is the first FDA-approved treatment for HSDD. It is only approved in premenopausal women, so it would be considered off-label use if she is postmenopausal (even though she is quite young). You also could consider exogenous testosterone off-label, after consulting with her oncologist.

In addition to the obvious physiologic etiology of her pain and her low desire, the biopsychosocial aspects to consider are: 1) changes to her body image, as she has had bilateral mastectomies, 2) her anxiety about the cancer diagnosis, and 3) concerns about her relationship if she has one--her partner's reactions to her illness and the quality of the relationship outside the bedroom.

Dr. Iglesia: I am seeing here in our nation's capital a lot of advertisements for laser therapy for GSM. I caution women about this because providers are charging a lot of money for this therapy when we do not have long-term safety and effectiveness data for it.

Our group is currently conducting a randomized controlled trial, looking at vaginal estrogen cream versus laser therapy for GSM here at Medstar Health--one of the first in the country as part of a multisite trial. But the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) has come out with a pretty strong statement,4 as has ACOG,5 on this therapy, and I caution people about overzealously offering a very costly procedure targeted to a very vulnerable population, especially to women with personal histories of estrogen-sensitive cancers.

Dr. Krychman: I agree. Very often cancer patients are preyed upon by those offering emerging unproven technologies or medications. We have to work as a coordinated comprehensive team, whether it's a sexual medicine expert, psychologist, urogynecologist, gynecologist, or oncologist, and incorporate the patient's needs and expectations and risk tolerance coupled with treatment efficacy and safety.

Dr. Levy: This was a complex case. The biopsychosocial model is critical here. It's important that we are not siloes in our medical management approach and that we try to help this patient embrace the complexity of her situation. It's not only that she has cancer at age 36; there is a possible guilt factor if she has children and passed that gene on.

Another point that we began to talk about is the fact that in this country we tend to be early adopters of new technology. In our discussion with patients, we should focus on what we know and the risk of the unknowns related to some of the treatment options. But let's discuss lasers a little more later on.

Diminished arousal and orgasmic intensity in a patient taking SSRIs

Dr. Levy: In this next case, a 44-year-old woman in a 15-year marriage notices a change in her orgasmic intensity and latency. She has a supportive husband, and they are attentive to each other's sexual needs. However, she notices a change in her arousal and orgasmic intensity, which has diminished over the last year. She reports that the time to orgasm or latency has increased and both she and her partner are frustrated and getting concerned. She has a history of depression that has been managed by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the past 5 years and has no depressive symptoms currently.

Dr. Krychman, what are you considering before beginning to talk with this patient?

Dr. Krychman: My approach really is a comprehensive one, looking not only at the underlying medical issues but also at the psychological and dynamic relationship facets. We of course also want to look at medications: Has she changed her dose or the timing of when she takes it? Is this a new onset? Finally, we want to know why this is coming to the forefront now. Is it because it is getting worse, or is it because there is some significant issue that is going on in the relationship?

Regarding the physical exam, it is important to rule out underlying genital pelvic pathology. Young women can get changes in the integrity of the pelvic floor, in what I would call the orgasmic matrix--the clitoral tissue, the body, the crura (or arms of the clitoris)--we want to examine and be reassured that her genital anatomy is normal and that there is no underlying pathology that could signal an underlying abnormal hormonal profile. Young women certainly can get lowered estrogen effects at the genital/pelvic tissues (including the labia and vulva), and intravaginally as well. Sometimes women will have pelvic floor hypertonus, as we see with other urinary issues. A thorough pelvic exam is quite vital.

Let's not forget the body that is attached to the genitals; we want to rule out chronic medical disease that may impact her: hypertension, diabetes, or hypercholesterolemia. Untreated, these conditions may directly impact the arousal physiologic mechanisms.

Dr. Levy: In doing this patient's physical exam I would be looking for significant weight gain, and even asking about her partner's weight. Body image can be a huge issue. If she has a history of depression, if she is suffering from a body image problem, she can be feeling unattractive. In my experience this can be a common thing to affect women in their mid-40s.

How would you manage this case?

Dr. Krychman: It is important to divide it up in terms of a conservative to aggressive approach. We want to find out about the relationship. For instance, is the sexual dynamic scripted (ie, boring and predictable)? Is she distracted and frustrated or is she getting enough of the type of stimulation that she likes and enjoys? There certainly are a lot of new devices that are available, whether a self-stimulator or vibrator, the Fiera, or other stimulating devices, that may be important to incorporate into the sexual repertoire. If there is underlying pathology, we want to evaluate and treat that. She may need to be primed, so to speak, with systemic hormones. And does she have issues related to other effects of hormonal deprivation, even local effects? Does she have clitoral atrophy?

There are neutraceuticals that are currently available, whether topical arousal gels or ointments, and we as clinicians need to be critical and evaluate their benefit/risk and look at the data concerning these products. In addition, women who have changes in arousal and in orgasmic intensity and latency may be very frustrated. They describe it as climbing up to a peak but never getting over the top, and this frustration may lead to participant spectatoring, so incorporating a certified sex therapist or counselor is sometimes very critical.

Finally, there are a lot of snake oils, charmers, and charlatan unproven procedures--injecting fillers or other substances into the clitoris are a few examples. I would be a critical clinician, examine the evidence, look at the benefit/risk before advocating an intervention that does not have good clinical data to support its use--a comprehensive approach of sexual medicine as well as sexual psychology.

Dr. Kingsberg: Additionally, we know she is in a long-term relationship--15 years; we want to acknowledge the partner. We talked about the partner's weight, but what about his erectile function? Does he have changes in sexual function that are affecting her, and she is the one carrying the "symptom"?

Looking at each piece separately helps a clinician from getting overwhelmed by the patient who comes in reporting distress with orgasmic dysfunction. We have no pharmacologic FDA-approved treatments, so it can feel off-putting for a clinician to try to fix the reported issue. Looking at each component to help her figure out the underlying cause can be helpful.

Dr. Iglesia: With aging, there can be changes in blood flow, not to mention the hormonal and even peripheral nerve changes, that require more stimulation in order to achieve the desired response. I echo concern about expensive procedures being offered with no evidence, such as the "O" or "G" shot, that can cost up to thousands of dollars.

The other procedure that gives me a lot of angst is clitoral unhooding. The 3 parts of the clitoris are sensitive in terms of innervation and blood flow, and cutting around that delicate tissue goes against the surgical principles required for preserving nerves and blood flow.

New onset pain post−prolapse surgery with TOT sling placement

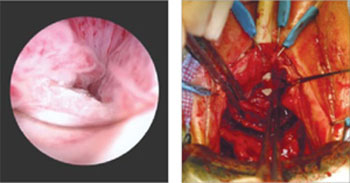

Dr. Levy: For this case, let's consider a 42-year-old woman (P3) who is 6 months post− vaginal hysterectomy. The surgery included ovarian preservation combined with anterior and posterior repair for prolapse as well as apical uterosacral ligament suspension for stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse. A transobturator sling was used.

Extensive preop evaluation was performed, with confirmed symptomatic prolapse. She had no stress incontinence symptoms but did have confirmed occult stress incontinence.

Surgery was uneventful. She resumed intercourse at 8 weeks, but she now has pain with both initial entry and deep penetration. Lubricants and changes in position have not helped. She is in a stable relationship with her husband of 17 years, and she is worried that the sling mesh might be the culprit. On exam, she has no atrophy, pH is 4.5, vaginal length is 8 cm, and there is no prolapse. There is no mesh exposure noted, although she reports slight tenderness with palpation of the right sling arm beneath the right pubic bone.

Dr. Iglesia, what are the patient history questions important to ask here?

Dr. Iglesia: This is not an uncommon scenario--elective surgical correction of occult or latent stress incontinence after surgical correction for pelvic organ prolapse. Now this patient here has no more prolapse complaints; however, she has a new symptom. There are many different causes of dyspareunia; we cannot just assume it is the sling mesh (although with all the legal representation advertisements for those who have had mesh placed, it can certainly be at the top of the patient's mind, causing anxiety and fear).

Multiple trials have looked at prophylactic surgery for incontinence at the time of prolapse repairs. This woman happened to be one of those patients who did not have incontinence symptoms, and they put a sling in. A recent large trial examined women with vaginal prolapse who underwent hysterectomy and suspension.6 (They compared 2 different suspensions.) What is interesting is that 25% of women with prolapse do have baseline pain. However, at 24 months, de novo pain can occur in 10% of women--just from the apical suspension. So, here, it could be the prolapse suspension. Or, in terms of the transobturator sling, long-term data do tell us that the de novo dyspareunia rate ranges on the magnitude of 1% to 9%.7 What is important here is figuring out the cause of the dyspareunia.

Dr. Levy: One of the important points you raised already was that 25% of these women have preoperative pain. So figuring out what her functioning was before surgery and incorporating that into our assessment postop would be pretty important I would think.

Dr. Iglesia: Yes, you need to understand what her typical encounter was before the surgery and how things have changed now that the prolapse is not in the way. Changes obviously can occur with scar tissue, which over time will improve. If she is perimenopausal and starts to get epithelial changes, we can fix that. The question then becomes, "Is the pain emanating from the mesh?"

When examining this patient, it is not uncommon for me to be able to feel "banjo" strings if the mesh is too tight or close to the surface. It is not exposed but it's palpable, and the patient may feel a ridge during penetration. You can ask the patient if pain occurs with different penetration positions. In addition, explore associated neurologic symptoms (numbness or muscle pain in the thigh).

Dr. Kingsberg: There were 2 different sources of pain--on initial entry and at deep penetration. You want to make sure you address both. Importantly, did one precede the other? For instance, if women have pain with penetration they can then end up with an arousal disorder (the length of the vagina cannot increase as much as it might otherwise) and dystonia secondary to the pain with penetration. The timing of the pain--did it all happen at the same time, or did she start out with pain at one point and did it move to something else--is another critical piece of the history.

Dr. Iglesia: It does take a detailed history and physical exam to identify myofascial trigger points. In this case there seems to be pinpoint tenderness directly on the part of the mesh that is not exposed on the right. There are people who feel you should remove the whole mesh, including the arms. Others feel, okay, we can work on these trigger points, with injections, physical therapy, extra lubrication, and neuromodulatory medications. Only then would they think about potentially excising the sling or a portion thereof.

Dr. Krychman: Keep in mind that, even if you do remove the sling, her pain may not subside, if it is secondary to an underlying issue. Because of media sensationalism, she could be focusing on the sling. It is important to set realistic expectations. I often see vulvar pathology or even provoked vestibulodynia that can present with a deep dyspareunia. The concept of collision dyspareunia or introital discomfort or pain on insertion has far reaching implications. We need to look at the patient in totality, ruling out underlying issues related to the bladder, even the colon.

Patient inquires about the benefits of laser treatment for vaginal health

Dr. Levy: Let's move to this last case: A 47-year-old patient who reports lack of sexual satisfaction and attributes it to a loose vagina says, "I've heard about surgery and laser treatment and radiofrequency devices for vaginal health. What are the benefits and risks of these procedures, and will they correct the issues that I'm experiencing?"

How do you approach this patient?

Dr. Krychman: I want to know why this is of paramount importance to her. Is this her actual complaint or is it society's unrealistic expectation of sexual pleasure and performance placed upon her? Or is this a relationship issue surfacing, compounded by physiologic changes? With good communication techniques, like "ask, tell, ask" or effective use of silence (not interrupting), patients will lead us to the reason and the rationale.

Dr. Levy: I have seen a lot of advertising to women, now showing pictures of genitalia, perhaps creating an expectation that we should look infantile in some way. We are creating a sense of beauty and acceptablevisualization of the vagina and vulva that are completely unrealistic. It's fascinating on one hand but it is also disturbing in that some of the direct-to-consumer marketing going on is creating a sense of unease in women who are otherwise perfectly satisfied. Now they take a look at their sagging skin, maybe after having 2 or 3 children, and although they may not look the same they function not so badly perhaps. I think we are creating a distress and an illness model that is interesting to discuss.

Dr. Iglesia, you are in the midst of a randomized trial, giving an informed consent to participants about the expectations for this potential intervention. How do you explain to women what these laser and radiofrequency devices are expected to do and why they might or might not work?

Dr. Iglesia: We are doing a randomized trial for menopausal women who have GSM. We are comparing estrogen cream with fractional CO2 laser therapy. I also am involved in another randomized trial for lichen sclerosus. I am not involved in the cosmetic use of a laser for people who feel their vaginas are just "loose." Like you, Dr. Levy, I am very concerned about the images that women are seeing of the idealized vulva and vagina, and about the rise of cosmetic gynecology, much of which is being performed by plastic surgeons or dermatologists.

A recent article looked at the number of women who are doing pubic hair grooming; the prevalance is about 80% here in America.8 So people have a clear view of what is down there, and then they compare it to what they see in pornographic images on the Internet and want to look like a Barbie doll. That is disturbing because women, particularly young women, do not realize what happens with GSM changes to the vulva and vagina. On the other hand, these laser machines are very expensive, and some doctors are charging thousands of dollars and promising cosmetic and functional results for which we lack long-term, comparative data.

The laser that we are studying is one by Cynosure called Mona Lisa, which works with fractional CO2 and has very low depth of penetration. The concept is that, with microdot therapy (on the order of micrometers), pinpoint destruction will foster regeneration of new collagen and blood flow to the vagina and vulva. We are still in the midst of analyzing this.

Dr. Krychman: I caution people not to lump devices together. There is a significant difference between laser and radiofrequency--especially in the depth of tissue penetration, and level of evidence as well. There are companies performing randomized clinical trials, with well designed sham controls, and have demonstrated clinical efficacy. We need to be cautious of a procedure that is saying it's the best thing since sliced bread, curing interstitial cystitis, dyspareunia, and lichen sclerosus and improving orgasm, lubrication, and arousal. These far reaching, off-label claims are concerning and misleading.

Dr. Levy: I think the important things are 1) shared decision making with the patient and 2) disclosure of what we do not know, which are the long-term results and outcomes and possible downstream negative effects of some of these treatments, since the data we have are so short term.

Dr. Kingsberg: Basics are important. You talked about the pressure for cosmetic appearance, but is that really what is going on for this particular patient? Is she describing a sexual dysfunction when she talks about lack of satisfaction? You need to operationally define that term. Does she have problems with arousal or orgasm or desire and those are what underlie her lack of satisfaction? Is the key to management helping her come to terms with body image issues or to treat a sexual dysfunction? If it truly is a sexual dysfunction, then you can have the shared decision making on preferred treatment approach.

Dr. Levy: This has been an enlightening discussion. Thank all of you for your expertise and clinical acumen.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The age-adjusted prevalence of any sexual problem is 43% among US women. A full 22% of these women experience sexually related personal distress.1 With publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition2 has come a shift in classification and, at times, management approach for reported female sexual dysfunction. When women report to their clinicians decreased sexual desire or arousal or pain at penetration, the management is no longer guided by a linear model of sexual response (excitation, plateau, orgasm, and resolution) but rather by a more nuanced and complex biopsychosocial approach. In this model, diagnosis and management strategies to address bothersome sexual concerns consider the whole woman in the context of her physical and psychosocial health. The patient’s age, medical history, and relationship status are among the factors that could affect management of the problem. In an effort to explore this management approach, I used this Update on Female Sexual Dysfunction as an opportunity to convene a roundtable of several experts, representing varying backgrounds and practice vantage points, to discuss 5 cases of sexual problems that you as a busy clinician may encounter in your practice.

Genital atrophy in a sexually inactive 61-year-old woman

Barbara S. Levy, MD: Two years after her husband's death, which followed several years of illness, your 61-year-old patient mentions at her well woman visit that she anticipates becoming sexually active again. She has not used systemic or vaginal hormone therapy. During pelvic examination, atrophic external genital changes are present, and use of an ultrathin (thinner than a Pederson) speculum reveals vaginal epithelial atrophic changes. A single-digit bimanual exam can be performed with moderate patient discomfort; the patient cannot tolerate a 2-digit bimanual exam. She expresses concern about being able to engage in penile/vaginal sexual intercourse.

Dr. Kaunitz, what is important for you to ask this patient, and what concerns you most on her physical exam?

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD: First, it is important to recognize the patient's expectations and desires. As the case suggests, but further questioning could clarify, she would like to be able to comfortably engage in sexual intercourse with a new partner, but penetration may be difficult (and definitely painful for her) unless treatment is pursued. This combination of mucosal and vestibular atrophic changes (genitourinary syndrome of menopause [GSM], or vulvovaginal atrophy [VVA]) plus the absence of penetration for many years can be a double whammy situation for menopausal women. In this case it has led to extensive contracture of the introitus, and if it is not addressed will cause sexual dysfunction.

Dr. Levy: In addition we need to clarify whether or not a history of breast cancer or some other thing may impact the care we provide. How would you approach talking with this patient in order to manage her care?

Dr. Kaunitz: One step is to see how motivated she is to address this, as it is not something that, as gynecologists, we can snap our fingers and the situation will be resolved. If the patient is motivated to treat the atrophic changes with medical treatment, in the form of low-dose vaginal estrogen, and dilation, either on her own if she's highly motivated to do so, or in my practice more commonly with the support of a women's physical therapist, over time she should be able to comfortably engage in sexual intercourse with penetration. If this is what she wants, we can help steer her in the right direction.

Sheryl Kingsberg, PhD: You know that this woman is motivated by virtue of her initiating the topic herself. Patients are often embarrassed talking about sexual issues, or they are not sure that their gynecologist is comfortable with it. After all, they think, if this is the right place to discuss sexual problems, why didn't he or she ask me? Clinicians must be aware that it is their responsibility to ask about sexual function and not leave it for the patient to open the door.

Dr. Kaunitz: Great point.

Cheryl B. Iglesia, MD: Gratefully, a lot of the atrophic changes this patient demonstrates are reversible. However, other autoimmune diseases (eg, lichen planus, which can affect the vaginal epithelium, or lichen sclerosus, which can affect the clitoris, labia, and vulva) can also cause constriction, and in severe cases, complete obliteration of the vagina and introitus. Women may not be sexually active, and for each annual exam their clinician uses a smaller and smaller speculum--to the point that they cannot even access the cervix anymore--and the vagina can close off. Clinicians may not realize that you need something other than estrogen; with lichen planus you need steroid suppository treatment, and with lichen sclerosus you need topical steroid treatment. So these autoimmune conditions should also be in the differential and, with appropriate treatment, the sexual effects can be reversible.

Michael Krychman, MD: I agree. The vulva can be a great mimicker and, according to the history and physical exam, at some point a vulvoscopy, and even potential biopsies, may be warranted as clinically indicated.

The concept of a comprehensive approach, as Dr. Kingsberg had previously mentioned, involves not only sexual medicine but also evaluating the patient's biopsychosocial variables that may impact her condition. We also need to set realistic expectations. Some women may benefit from off-label use of medications besides estrogen, including topical testosterone. Informed consent is very important with these treatments. I also have had much clinical success with intravaginal diazepam/lorazepam for pelvic floor hypertonus.

In addition, certainly I agree that pelvic floor physical therapy (PT) is a vital treatment component for this patient and, not to diminish its importance, but many women cannot afford, nor do they have the time or opportunity, to go to pelvic floor PT. As clinicians, we can develop and implement effective programs, even in the office, to educate the patient to help herself as well.

Dr. Kaunitz: Absolutely. Also, if, in a clinical setting consistent with atrophic changes, an ObGyn physician is comfortable that vulvovaginal changes noted on exam represent GSM/atrophic changes, I do not feel vulvoscopy is warranted.

Dr. Levy: In conclusion, we need to be aware that pelvic floor PT may not be available everywhere and that a woman's own digits and her partner can also be incorporated into this treatment.

Something that we have all talked about in other venues, but have not looked at in the larger sphere here, is whether there is value to seeing women annually and performing pelvic exams. As Dr. Kingsberg mentioned, this is a highly motivated patient. We have many patients out there who are silent sufferers. The physical exam is an opportunity for us to recognize and address this problem.

Dyspareunia and low sexual desire in a breast cancer survivor

Dr. Levy: In this case, a 36-year-old woman with BRCA1−positive breast cancer has vaginal dryness, painful intercourse, and lowered sexual interest since her treatment, which included chemotherapy after bilateral mastectomies. She has a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy(BSO) scheduled for primary prevention of her ovarian cancer risk.

Dr. Kingsberg, what is important for you to know to help guide case management?

Dr. Kingsberg: This woman is actually presenting with 2 sexual problems: dyspareunia, which is probably secondary to VVA or GSM, and low sexual desire. Key questions are: 1) When was symptom onset--acquired after treatment or lifelong? 2) Did she develop the dyspareunia and as a result of having pain during sex lost desire to have sex? Or, did she lose desire and then, without it, had no arousal and therefore pain with penetration developed? It also could be that she has 2 distinct problems, VVA and hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), in which case you need to think about treating both. Finally, we do not actually know if she is having penetrative intercourse or even if she has a partner.

A vulvovaginal exam would give clues as to whether she has VVA, and hormone levels would indicate if she now has chemo-induced menopause. If she is not in menopause now, she certainly is going to be with her BSO. The hormonal changes due to menopause actually can be primarily responsible for both the dyspareunia and HSDD. Management of both symptoms really needs to be based on shared decision making with the patient--with which treatment for which conditions coming first, based on what is causing her the most distress.

I would encourage this woman to treat her VVA since GSM does have long-term physiologic consequences if untreated. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends nonhormonal treatments as first-line treatments, with vaginal estrogen considered if these therapies fail.3 If lubricants and moisturizers and other nonhormonal options are not sufficient, you could consider local estrogen, even though she is a breast cancer survivor, as well as ospemiphene.

If she is distressed by her loss of sexual desire, you can choose to treat her for HSDD. Flibanserin is the first FDA-approved treatment for HSDD. It is only approved in premenopausal women, so it would be considered off-label use if she is postmenopausal (even though she is quite young). You also could consider exogenous testosterone off-label, after consulting with her oncologist.

In addition to the obvious physiologic etiology of her pain and her low desire, the biopsychosocial aspects to consider are: 1) changes to her body image, as she has had bilateral mastectomies, 2) her anxiety about the cancer diagnosis, and 3) concerns about her relationship if she has one--her partner's reactions to her illness and the quality of the relationship outside the bedroom.

Dr. Iglesia: I am seeing here in our nation's capital a lot of advertisements for laser therapy for GSM. I caution women about this because providers are charging a lot of money for this therapy when we do not have long-term safety and effectiveness data for it.

Our group is currently conducting a randomized controlled trial, looking at vaginal estrogen cream versus laser therapy for GSM here at Medstar Health--one of the first in the country as part of a multisite trial. But the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) has come out with a pretty strong statement,4 as has ACOG,5 on this therapy, and I caution people about overzealously offering a very costly procedure targeted to a very vulnerable population, especially to women with personal histories of estrogen-sensitive cancers.

Dr. Krychman: I agree. Very often cancer patients are preyed upon by those offering emerging unproven technologies or medications. We have to work as a coordinated comprehensive team, whether it's a sexual medicine expert, psychologist, urogynecologist, gynecologist, or oncologist, and incorporate the patient's needs and expectations and risk tolerance coupled with treatment efficacy and safety.

Dr. Levy: This was a complex case. The biopsychosocial model is critical here. It's important that we are not siloes in our medical management approach and that we try to help this patient embrace the complexity of her situation. It's not only that she has cancer at age 36; there is a possible guilt factor if she has children and passed that gene on.

Another point that we began to talk about is the fact that in this country we tend to be early adopters of new technology. In our discussion with patients, we should focus on what we know and the risk of the unknowns related to some of the treatment options. But let's discuss lasers a little more later on.

Diminished arousal and orgasmic intensity in a patient taking SSRIs

Dr. Levy: In this next case, a 44-year-old woman in a 15-year marriage notices a change in her orgasmic intensity and latency. She has a supportive husband, and they are attentive to each other's sexual needs. However, she notices a change in her arousal and orgasmic intensity, which has diminished over the last year. She reports that the time to orgasm or latency has increased and both she and her partner are frustrated and getting concerned. She has a history of depression that has been managed by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the past 5 years and has no depressive symptoms currently.

Dr. Krychman, what are you considering before beginning to talk with this patient?

Dr. Krychman: My approach really is a comprehensive one, looking not only at the underlying medical issues but also at the psychological and dynamic relationship facets. We of course also want to look at medications: Has she changed her dose or the timing of when she takes it? Is this a new onset? Finally, we want to know why this is coming to the forefront now. Is it because it is getting worse, or is it because there is some significant issue that is going on in the relationship?

Regarding the physical exam, it is important to rule out underlying genital pelvic pathology. Young women can get changes in the integrity of the pelvic floor, in what I would call the orgasmic matrix--the clitoral tissue, the body, the crura (or arms of the clitoris)--we want to examine and be reassured that her genital anatomy is normal and that there is no underlying pathology that could signal an underlying abnormal hormonal profile. Young women certainly can get lowered estrogen effects at the genital/pelvic tissues (including the labia and vulva), and intravaginally as well. Sometimes women will have pelvic floor hypertonus, as we see with other urinary issues. A thorough pelvic exam is quite vital.

Let's not forget the body that is attached to the genitals; we want to rule out chronic medical disease that may impact her: hypertension, diabetes, or hypercholesterolemia. Untreated, these conditions may directly impact the arousal physiologic mechanisms.

Dr. Levy: In doing this patient's physical exam I would be looking for significant weight gain, and even asking about her partner's weight. Body image can be a huge issue. If she has a history of depression, if she is suffering from a body image problem, she can be feeling unattractive. In my experience this can be a common thing to affect women in their mid-40s.

How would you manage this case?

Dr. Krychman: It is important to divide it up in terms of a conservative to aggressive approach. We want to find out about the relationship. For instance, is the sexual dynamic scripted (ie, boring and predictable)? Is she distracted and frustrated or is she getting enough of the type of stimulation that she likes and enjoys? There certainly are a lot of new devices that are available, whether a self-stimulator or vibrator, the Fiera, or other stimulating devices, that may be important to incorporate into the sexual repertoire. If there is underlying pathology, we want to evaluate and treat that. She may need to be primed, so to speak, with systemic hormones. And does she have issues related to other effects of hormonal deprivation, even local effects? Does she have clitoral atrophy?

There are neutraceuticals that are currently available, whether topical arousal gels or ointments, and we as clinicians need to be critical and evaluate their benefit/risk and look at the data concerning these products. In addition, women who have changes in arousal and in orgasmic intensity and latency may be very frustrated. They describe it as climbing up to a peak but never getting over the top, and this frustration may lead to participant spectatoring, so incorporating a certified sex therapist or counselor is sometimes very critical.

Finally, there are a lot of snake oils, charmers, and charlatan unproven procedures--injecting fillers or other substances into the clitoris are a few examples. I would be a critical clinician, examine the evidence, look at the benefit/risk before advocating an intervention that does not have good clinical data to support its use--a comprehensive approach of sexual medicine as well as sexual psychology.

Dr. Kingsberg: Additionally, we know she is in a long-term relationship--15 years; we want to acknowledge the partner. We talked about the partner's weight, but what about his erectile function? Does he have changes in sexual function that are affecting her, and she is the one carrying the "symptom"?

Looking at each piece separately helps a clinician from getting overwhelmed by the patient who comes in reporting distress with orgasmic dysfunction. We have no pharmacologic FDA-approved treatments, so it can feel off-putting for a clinician to try to fix the reported issue. Looking at each component to help her figure out the underlying cause can be helpful.

Dr. Iglesia: With aging, there can be changes in blood flow, not to mention the hormonal and even peripheral nerve changes, that require more stimulation in order to achieve the desired response. I echo concern about expensive procedures being offered with no evidence, such as the "O" or "G" shot, that can cost up to thousands of dollars.

The other procedure that gives me a lot of angst is clitoral unhooding. The 3 parts of the clitoris are sensitive in terms of innervation and blood flow, and cutting around that delicate tissue goes against the surgical principles required for preserving nerves and blood flow.

New onset pain post−prolapse surgery with TOT sling placement

Dr. Levy: For this case, let's consider a 42-year-old woman (P3) who is 6 months post− vaginal hysterectomy. The surgery included ovarian preservation combined with anterior and posterior repair for prolapse as well as apical uterosacral ligament suspension for stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse. A transobturator sling was used.

Extensive preop evaluation was performed, with confirmed symptomatic prolapse. She had no stress incontinence symptoms but did have confirmed occult stress incontinence.

Surgery was uneventful. She resumed intercourse at 8 weeks, but she now has pain with both initial entry and deep penetration. Lubricants and changes in position have not helped. She is in a stable relationship with her husband of 17 years, and she is worried that the sling mesh might be the culprit. On exam, she has no atrophy, pH is 4.5, vaginal length is 8 cm, and there is no prolapse. There is no mesh exposure noted, although she reports slight tenderness with palpation of the right sling arm beneath the right pubic bone.

Dr. Iglesia, what are the patient history questions important to ask here?

Dr. Iglesia: This is not an uncommon scenario--elective surgical correction of occult or latent stress incontinence after surgical correction for pelvic organ prolapse. Now this patient here has no more prolapse complaints; however, she has a new symptom. There are many different causes of dyspareunia; we cannot just assume it is the sling mesh (although with all the legal representation advertisements for those who have had mesh placed, it can certainly be at the top of the patient's mind, causing anxiety and fear).

Multiple trials have looked at prophylactic surgery for incontinence at the time of prolapse repairs. This woman happened to be one of those patients who did not have incontinence symptoms, and they put a sling in. A recent large trial examined women with vaginal prolapse who underwent hysterectomy and suspension.6 (They compared 2 different suspensions.) What is interesting is that 25% of women with prolapse do have baseline pain. However, at 24 months, de novo pain can occur in 10% of women--just from the apical suspension. So, here, it could be the prolapse suspension. Or, in terms of the transobturator sling, long-term data do tell us that the de novo dyspareunia rate ranges on the magnitude of 1% to 9%.7 What is important here is figuring out the cause of the dyspareunia.

Dr. Levy: One of the important points you raised already was that 25% of these women have preoperative pain. So figuring out what her functioning was before surgery and incorporating that into our assessment postop would be pretty important I would think.

Dr. Iglesia: Yes, you need to understand what her typical encounter was before the surgery and how things have changed now that the prolapse is not in the way. Changes obviously can occur with scar tissue, which over time will improve. If she is perimenopausal and starts to get epithelial changes, we can fix that. The question then becomes, "Is the pain emanating from the mesh?"

When examining this patient, it is not uncommon for me to be able to feel "banjo" strings if the mesh is too tight or close to the surface. It is not exposed but it's palpable, and the patient may feel a ridge during penetration. You can ask the patient if pain occurs with different penetration positions. In addition, explore associated neurologic symptoms (numbness or muscle pain in the thigh).