User login

Evaluation of Patch Test Reactivities in Patients With Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria

Chronic urticaria (CU) is clinically defined as the daily or almost daily presence of wheals on the skin for at least 6 weeks.1 Chronic urticaria severely affects patients’ quality of life and can cause emotional disability and distress.2 In clinical practice, CU is one of the most common and challenging conditions for general practitioners, dermatologists, and allergists. It can be provoked by a wide variety of different causes or may be the clinical presentation of certain systemic diseases3,4; thus, CU often requires a detailed and time-consuming diagnostic procedure that includes screening for allergies, autoimmune diseases, parasites, malignancies, infections, and metabolic disorders.5,6 In many patients (up to 50% in some case series), the cause or pathogenic mechanism cannot be identified, and the disease is then classified as chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU).7

It has previously been shown that contact sensitization could have some relation with CIU,8 which was further explored in this study. This study sought to evaluate if contact allergy may play a role in disease development in CIU patients in Saudi Arabia and if patch testing should be routinely performed for CIU patients to determine if any allergens can be avoided.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted at the King Khalid University Hospital Allergy Clinic (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) in patients aged 18 to 60 years who had CU for more than 6 weeks. It was a clinic-based study conducted over a period of 2 years (March 2010 to February 2012). The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee at King Khalid University Hospital. Valid written consent was obtained from each patient.

Patients were excluded if they had CU caused by physical factors (eg, hot or cold temperature, water, physical contact) or drug reactions that were possible causative factors or if they had taken oral prednisolone or other oral immunosuppressive drugs (eg, azathioprine, cyclosporine) in the last month. However, patients taking antihistamines were not excluded because it was impossible for the patients to discontinue their urticaria treatment. Other exclusion criteria included CU associated with any systemic disease, thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune disorder, or atopic dermatitis. Pregnant and lactating women were not included in this study.

All new adult CU patients (ie, disease duration >6 weeks) were worked up using the routine diagnostic tests that are typically performed for any new CU patient, including complete blood cell count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, liver function tests, urine analysis, and hepatitis B and C screenings. Further diagnostic tests also were carried out when appropriate according to the patient’s history and physical examination, including levels of urea, electrolytes, thyrotropin, thyroid antibodies (antithyroglobulin and antimicrosomal), and antinuclear antibodies, as well as a Helicobacter pylori test.

All of the patients enrolled in the study were evaluated by skin prick testing to establish the link between CU and its cause. Patch testing was performed in patients who were negative on skin prick testing.

Skin Prick Testing

All patients were advised to temporarily discontinue the use of antihistamines and corticosteroids 5 to 6 days prior to testing.

Patch Testing

Patch tests were carried out using a ready-to-use epicutaneous patch test system for the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).10 A European standard series was used with the addition of 4 allergens of local relevance: black seed oil, local perfume mix, henna, and myrrh (a topical herbal medicine used to promote healing).

Assessment of Improvement

Assessment of urticaria severity using the Chronic Urticaria Severity Score (CUSS), a simple semiquantitative assessment of disease activity, was calculated as the sum of the number of wheals and the degree of itch severity graded from 0 (none) to 3 (severe), according to the guidelines established by the Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology, the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network, the European Dermatology Forum, and the World Allergy Organization.11 The avoidance group of patients was assessed at baseline and after 1 month to evaluate changes in their CUSS after allergen avoidance for 8 weeks.

Statistical Analysis

All of the statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software version 16. Results were presented as the median with the range or the mean (SD).

Results

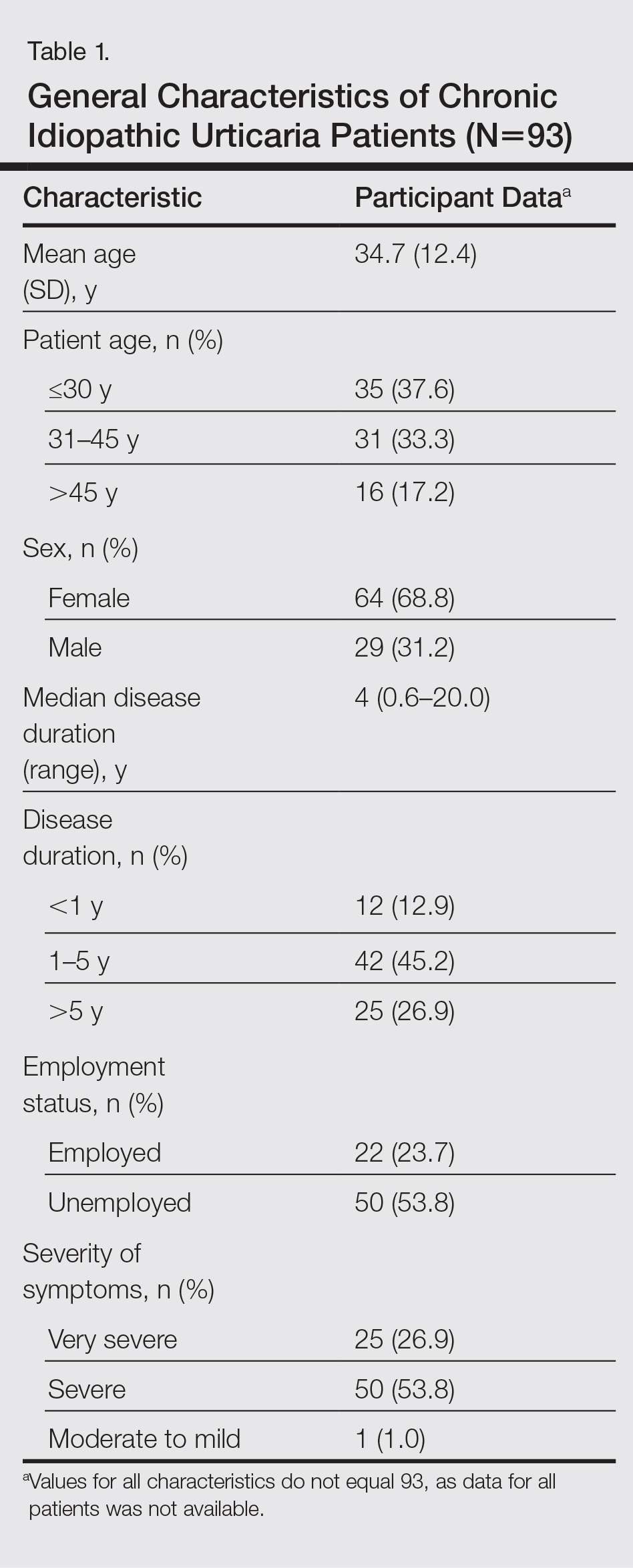

During the study period, a total of 120 CU patients were seen at the clinic. Ninety-three patients with CU met our selection criteria (77.5%) and were enrolled in the study. The mean age (SD) of the patients was 34.7 (12.4) years. Women comprised 68.8% (64/93) of the study population (Table 1).

The duration of urticaria ranged from 0.6 to 20 years, with a median duration of 4 years. Approximately half of the patients (50/93) experienced severe symptoms of urticaria, but only 26.9% (25/93) had graded their urticaria as very severe.

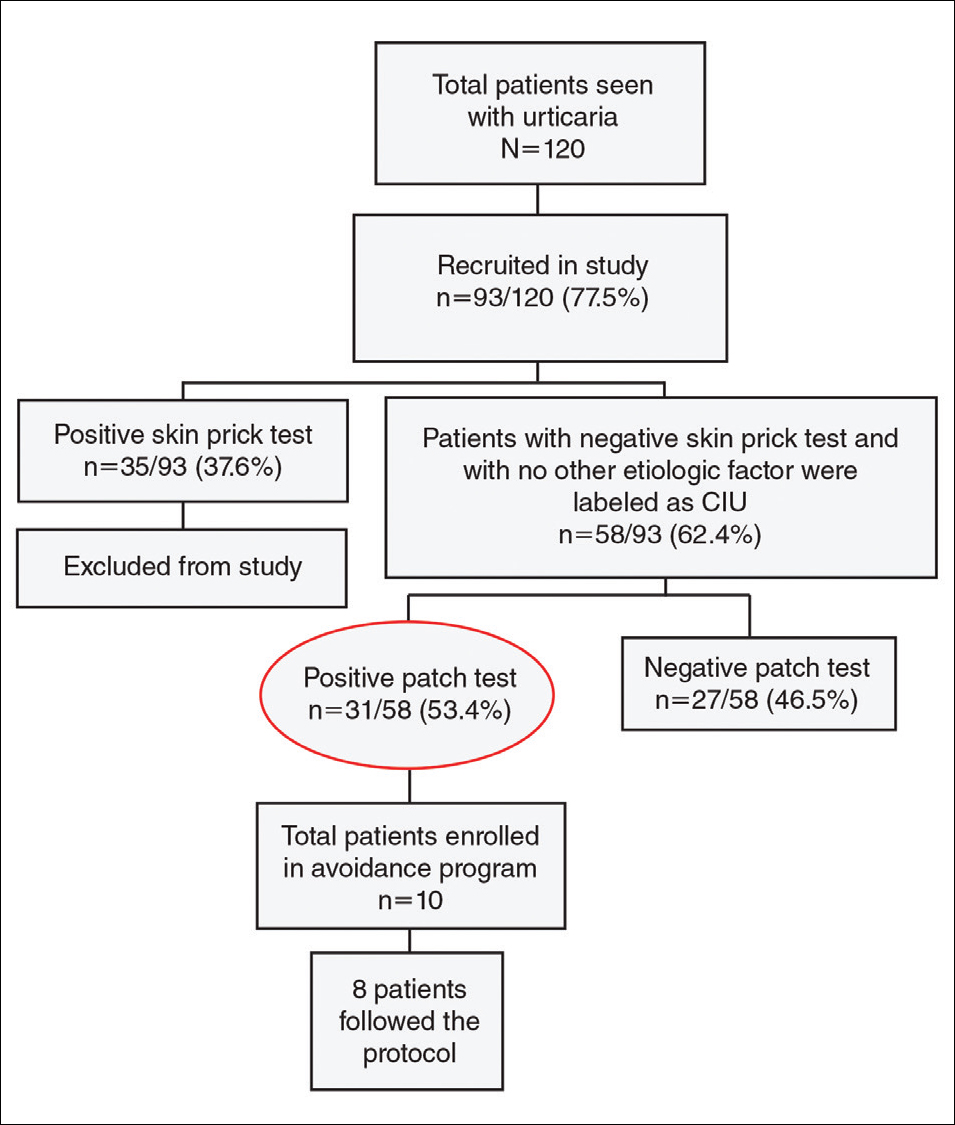

Negative results from the skin prick test were reported in 62.4% (58/93) of patients and were subsequently patch tested. These patients also had no other etiologic factors (eg, infection; thyroid, autoimmune, or metabolic disease). Patients who had positive skin prick test results (35/93 [37.6%]) were not considered to be cases of CIU, according to diagnostic recommendations.12 Of the 58 CIU patients who were patch tested, 31 (53.4%) had positive results and 27 (46.5%) had negative results to both skin prick and patch tests (Figure).

Univariate analysis revealed significant associations between age, gender, and duration of urticaria and patch test positivity (χ2 test, P<.05). T

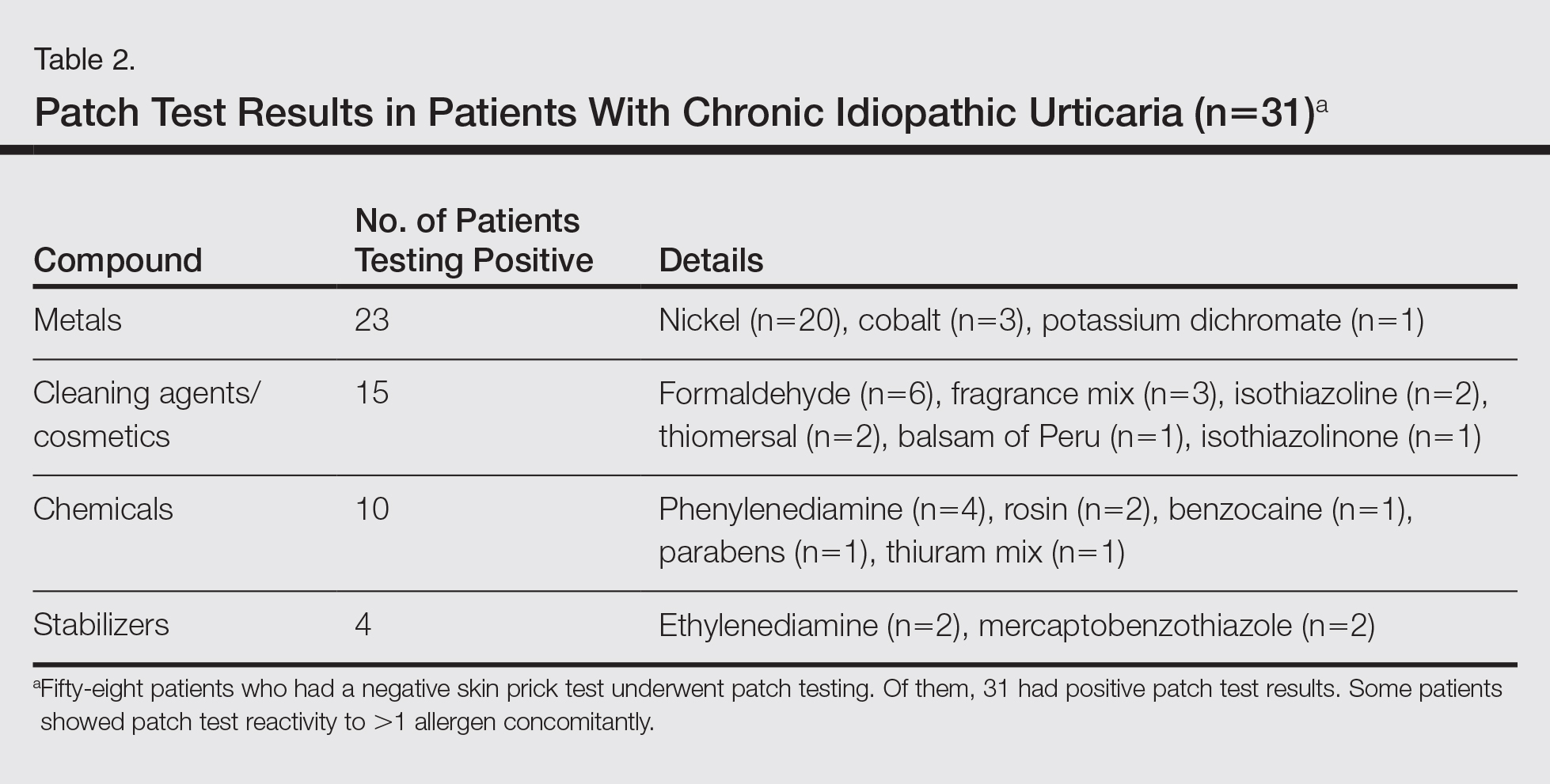

Of the 31 patients with positive patch tests, there were 20 positive reactions to nickel, 6 to formaldehyde, 4 to phenylenediamine, 3 to cobalt, and 3 to a fragrance mix (Table 2). Some patients showed patch test reactivity to more than 1 allergen concomitantly. Overall, these 31 patients had positive reactions to 16 allergens. None of the patients showed actual signs of contact dermatitis (Table 2).

Of

Comment

Chronic idiopathic urticaria is the diagnosis given when urticarial vasculitis, physical urticaria, and all other possible etiologic factors have been excluded in patients with CU. Our study was designed to assess patch test reactivity in patients with CU without any identifiable systemic etiologic factor after detailed laboratory testing and negative skin prick tests.

Chronic idiopathic urticaria can be an extremely disabling and difficult-to-treat condition. Because the cause is unknown, the management of CIU often is frustrating. The

Patch testing is commonly performed to diagnose ACD, and if contact allergens are found via patch testing, patients can often be cured of their dermatitis by avoiding these agents. However, patch testing is not routinely performed in the evaluation of patients with CIU. It is a relatively inexpensive and safe procedure to determine a causal link between sensitization to a specific agent and ACD. In patch test clinics, agents often are tested in standard and screening series. Sensitization that is not suspected from the patient’s history and/or clinical examination can be detected in this manner. Requirements for the inclusion of a chemical in a standard series have been formulated by Bruze et al.13 In addition, ready-to-use materials relevant to the specific leisure activities and working conditions also can be selected for patch testing.

A study conducted in Saudi Arabia showed that the European standard series is suitable for patch testing patients in this community14; however, 3 allergens of local relevance were added in our study: black seed oil, local perfume mix, and henna. Moreover, in our study we added a local allergen known as myrrh, which is a topical herbal medicine used to promote healing that has been reported to cause ACD in some cases.15 We sought to determine if contact allergens can be identified with patch testing in patients with CU and if avoiding these contact allergens would resolve the CU.

Urticaria was once considered an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction, but recent studies have demonstrated the existence of different subgroupsof urticaria, some with an autoimmune mechanism.1-4,11 In CU, skin prick tests are recommended for etiologic workup, while patch testing generally is not recommended.16

It has been observed in clinical practice that a substantial number of patients with CU are positive to patch tests, even without a clear clinical history or signs of contact dermatitis.17 In 2007, Guerra et al17 reported that of 121 patients with CU, 50 (41.3%) tested positive for contact allergens. In all of the patch test–positive patients, avoidance measures led to complete remission within 10 days to 1 month. Therefore, this result suggested that testing for contact sensitization could be helpful in the management of CU. Patients with nickel sensitivity were subsequently allowed to ingest small amounts of nickel-containing foods after 8 weeks of a completely nickel-free diet, and remission persisted.17

Contact dermatitis affects approximately 20% of the general population18; however, there has been little investigation (limited to nickel) into the relationship between contact allergens and CU,19,20 and the underlying mechanisms of the disease are unknown. It has been hypothesized that small amounts of the substances are absorbed through the skin or the digestive tract into the bloodstream over the long-term and are delivered to antigen-presenting cells in the skin, which provide the necessary signals for mast cell activation. Nonetheless, the reasons for a selectively cutaneous localization of the reaction remain largely unclear.

Management of CU is debated among physicians, and several diagnostic flowcharts have been proposed.1,2 In general, patch tests for contact dermatitis are not recommended as a fundamental part of the diagnostic procedure, but Guerra et al17 suggested that contact allergy often plays a role in CU.

There have been inadequate reports of CU found to be caused by common contact sensitizers.21-24 Interestingly, no signs of contact allergy were demonstrated in CU patients before urticarial attack.

Our findings supported our patient selection criteria and also confirmed that contact sensitization may be one of the many possible mechanisms involved in the etiology of CU. Urticaria may have a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction element, and patients with CU without an obvious causal factor can have positive patch test results.

The

The main findings of our study were that 53.4% of patients with CIU had positive patch test results and that avoidance of the sensitizing substance was effective in 5 of 8 patients who completed an avoidance program. Almost all of the patients showed notable remission of symptoms after limiting their exposure to the offending allergens. This study clearly showed that a cause or pathogenesis for CIU could be identified, thus showing that CIU occurs less frequently than is usually assumed.

Our study had limitations. The first is our lack of a controlled challenge test, which is important to confirm an allergen as a cause of CIU.26 Nonetheless, avoidance of the revealed contact allergen was associated with comparable improvement of CIU severity after 1 month in 5 of 8 patients, though such measures were not tested in all 31 of 58 CIU patients who had positive patch test results.

Conclusion

We propose that patch tests should be performed while investigating CU because they give effective diagnostic and therapeutic results in a substantial number of patients. Urticaria, or at least a subgroup of the disease, may have a delayed-type reaction element, which may explain the disease etiology for many CIU patients. Patients with CU without a detectable underlying etiologic factor can have positive patch test results.

- Zuberbier T, Bindslev-Jensen C, Canonica W, et al. Guidelines, definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2006;61:316-331.

- Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria: pathogenesis and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:465-474.

- Champion RH. Urticaria: then and now. Br J Dermatol. 1988;119:427-436.

- Green GA, Koelsche GA, Kierland R. Etiology and pathogenesis of chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy. 1965;23:30-36.

- Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria and angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:175-179.

- Dreskin SC, Andrews KY. The thyroid and urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:408-412.

- Greaves M. Chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:664-672.

- Sharma AD. Use of patch testing for identifying allergen causing chronic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:114-117.

- Li JT, Andrist D, Bamlet WR, et al. Accuracy of patient prediction of allergy skin test results. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:382-384.

- Nelson JL, Mowad CM. Allergic contact dermatitis: patch testing beyond the TRUE test. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:36-41.

- Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al; Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; European Dermatology Forum; World Allergy Organization. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1417-1426.

- Bindslev-Jensen C, Finzi A, Greaves M, et al. Chronic urticaria: diagnostic recommendations. Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:175-180.

- Bruze M, Conde-Slazar L, Goossens A, et al. Thoughts on sensitizers in a standard patch test series. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:241-250.

- Al-Sheikh OA, Gad El-Rab MO. Allergic contact dermatitis: clinical features and profile of sensitizing allergens in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:493-497.

- Al-Suwaidan SN, Gad El Rab MO, Al-Fakhiry S, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from myrrh, a topical herbal medicine used to promote healing. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:137.

- Henz BM, Zuberbier T. Causes of urticaria. In: Henz B, Zuberbier T, Grabbe J, et al, eds. Urticaria: Clinical Diagnostic and Therapeutic Aspects. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1998:19.

- Guerra L, Rogkakou A, Massacane P, et al. Role of contact sensitization in chronic urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:88-90.

- Thyssen JP, Linneberg A, Menné T, et al. The epidemiology of contact allergy in the general population—prevalence and main findings. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:287-299.

- Smart GA, Sherlock JC. Nickel in foods and the diet. Food Addit Contam. 1987;4:61-71.

- Abeck D, Traenckner I, Steinkraus V, et al. Chronic urticaria due to nickel intake. Acta Derm Venereol. 1993;73:438-439.

- Moneret-Vautrin DA. Allergic and pseudo-allergic reactions to foods in chronic urticaria [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130(Spec No 1):1S35-1S42.

- Wedi B, Raap U, Kapp A. Chronic urticaria and infections. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4:387-396.

- Foti C, Nettis E, Cassano N, et al. Acute allergic reactions to Anisakis simplex after ingestion of anchovies. Acta Derm Venerol. 2002;82:121-123.

- Uter W, Hegewald J, Aberer W, et al. The European standard series in 9 European countries, 2002/2003: first results of the European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:136-145.

- Magen E, Mishal J, Menachem S. Impact of contact sensitization in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:202-206.

- Antico A, Soana R. Chronic allergic-like dermatopathies in nickel sensitive patients: results of dietary restrictions and challenge with nickel salts. Allergy Asthma Proc. 1999;20:235-242.

Chronic urticaria (CU) is clinically defined as the daily or almost daily presence of wheals on the skin for at least 6 weeks.1 Chronic urticaria severely affects patients’ quality of life and can cause emotional disability and distress.2 In clinical practice, CU is one of the most common and challenging conditions for general practitioners, dermatologists, and allergists. It can be provoked by a wide variety of different causes or may be the clinical presentation of certain systemic diseases3,4; thus, CU often requires a detailed and time-consuming diagnostic procedure that includes screening for allergies, autoimmune diseases, parasites, malignancies, infections, and metabolic disorders.5,6 In many patients (up to 50% in some case series), the cause or pathogenic mechanism cannot be identified, and the disease is then classified as chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU).7

It has previously been shown that contact sensitization could have some relation with CIU,8 which was further explored in this study. This study sought to evaluate if contact allergy may play a role in disease development in CIU patients in Saudi Arabia and if patch testing should be routinely performed for CIU patients to determine if any allergens can be avoided.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted at the King Khalid University Hospital Allergy Clinic (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) in patients aged 18 to 60 years who had CU for more than 6 weeks. It was a clinic-based study conducted over a period of 2 years (March 2010 to February 2012). The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee at King Khalid University Hospital. Valid written consent was obtained from each patient.

Patients were excluded if they had CU caused by physical factors (eg, hot or cold temperature, water, physical contact) or drug reactions that were possible causative factors or if they had taken oral prednisolone or other oral immunosuppressive drugs (eg, azathioprine, cyclosporine) in the last month. However, patients taking antihistamines were not excluded because it was impossible for the patients to discontinue their urticaria treatment. Other exclusion criteria included CU associated with any systemic disease, thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune disorder, or atopic dermatitis. Pregnant and lactating women were not included in this study.

All new adult CU patients (ie, disease duration >6 weeks) were worked up using the routine diagnostic tests that are typically performed for any new CU patient, including complete blood cell count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, liver function tests, urine analysis, and hepatitis B and C screenings. Further diagnostic tests also were carried out when appropriate according to the patient’s history and physical examination, including levels of urea, electrolytes, thyrotropin, thyroid antibodies (antithyroglobulin and antimicrosomal), and antinuclear antibodies, as well as a Helicobacter pylori test.

All of the patients enrolled in the study were evaluated by skin prick testing to establish the link between CU and its cause. Patch testing was performed in patients who were negative on skin prick testing.

Skin Prick Testing

All patients were advised to temporarily discontinue the use of antihistamines and corticosteroids 5 to 6 days prior to testing.

Patch Testing

Patch tests were carried out using a ready-to-use epicutaneous patch test system for the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).10 A European standard series was used with the addition of 4 allergens of local relevance: black seed oil, local perfume mix, henna, and myrrh (a topical herbal medicine used to promote healing).

Assessment of Improvement

Assessment of urticaria severity using the Chronic Urticaria Severity Score (CUSS), a simple semiquantitative assessment of disease activity, was calculated as the sum of the number of wheals and the degree of itch severity graded from 0 (none) to 3 (severe), according to the guidelines established by the Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology, the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network, the European Dermatology Forum, and the World Allergy Organization.11 The avoidance group of patients was assessed at baseline and after 1 month to evaluate changes in their CUSS after allergen avoidance for 8 weeks.

Statistical Analysis

All of the statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software version 16. Results were presented as the median with the range or the mean (SD).

Results

During the study period, a total of 120 CU patients were seen at the clinic. Ninety-three patients with CU met our selection criteria (77.5%) and were enrolled in the study. The mean age (SD) of the patients was 34.7 (12.4) years. Women comprised 68.8% (64/93) of the study population (Table 1).

The duration of urticaria ranged from 0.6 to 20 years, with a median duration of 4 years. Approximately half of the patients (50/93) experienced severe symptoms of urticaria, but only 26.9% (25/93) had graded their urticaria as very severe.

Negative results from the skin prick test were reported in 62.4% (58/93) of patients and were subsequently patch tested. These patients also had no other etiologic factors (eg, infection; thyroid, autoimmune, or metabolic disease). Patients who had positive skin prick test results (35/93 [37.6%]) were not considered to be cases of CIU, according to diagnostic recommendations.12 Of the 58 CIU patients who were patch tested, 31 (53.4%) had positive results and 27 (46.5%) had negative results to both skin prick and patch tests (Figure).

Univariate analysis revealed significant associations between age, gender, and duration of urticaria and patch test positivity (χ2 test, P<.05). T

Of the 31 patients with positive patch tests, there were 20 positive reactions to nickel, 6 to formaldehyde, 4 to phenylenediamine, 3 to cobalt, and 3 to a fragrance mix (Table 2). Some patients showed patch test reactivity to more than 1 allergen concomitantly. Overall, these 31 patients had positive reactions to 16 allergens. None of the patients showed actual signs of contact dermatitis (Table 2).

Of

Comment

Chronic idiopathic urticaria is the diagnosis given when urticarial vasculitis, physical urticaria, and all other possible etiologic factors have been excluded in patients with CU. Our study was designed to assess patch test reactivity in patients with CU without any identifiable systemic etiologic factor after detailed laboratory testing and negative skin prick tests.

Chronic idiopathic urticaria can be an extremely disabling and difficult-to-treat condition. Because the cause is unknown, the management of CIU often is frustrating. The

Patch testing is commonly performed to diagnose ACD, and if contact allergens are found via patch testing, patients can often be cured of their dermatitis by avoiding these agents. However, patch testing is not routinely performed in the evaluation of patients with CIU. It is a relatively inexpensive and safe procedure to determine a causal link between sensitization to a specific agent and ACD. In patch test clinics, agents often are tested in standard and screening series. Sensitization that is not suspected from the patient’s history and/or clinical examination can be detected in this manner. Requirements for the inclusion of a chemical in a standard series have been formulated by Bruze et al.13 In addition, ready-to-use materials relevant to the specific leisure activities and working conditions also can be selected for patch testing.

A study conducted in Saudi Arabia showed that the European standard series is suitable for patch testing patients in this community14; however, 3 allergens of local relevance were added in our study: black seed oil, local perfume mix, and henna. Moreover, in our study we added a local allergen known as myrrh, which is a topical herbal medicine used to promote healing that has been reported to cause ACD in some cases.15 We sought to determine if contact allergens can be identified with patch testing in patients with CU and if avoiding these contact allergens would resolve the CU.

Urticaria was once considered an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction, but recent studies have demonstrated the existence of different subgroupsof urticaria, some with an autoimmune mechanism.1-4,11 In CU, skin prick tests are recommended for etiologic workup, while patch testing generally is not recommended.16

It has been observed in clinical practice that a substantial number of patients with CU are positive to patch tests, even without a clear clinical history or signs of contact dermatitis.17 In 2007, Guerra et al17 reported that of 121 patients with CU, 50 (41.3%) tested positive for contact allergens. In all of the patch test–positive patients, avoidance measures led to complete remission within 10 days to 1 month. Therefore, this result suggested that testing for contact sensitization could be helpful in the management of CU. Patients with nickel sensitivity were subsequently allowed to ingest small amounts of nickel-containing foods after 8 weeks of a completely nickel-free diet, and remission persisted.17

Contact dermatitis affects approximately 20% of the general population18; however, there has been little investigation (limited to nickel) into the relationship between contact allergens and CU,19,20 and the underlying mechanisms of the disease are unknown. It has been hypothesized that small amounts of the substances are absorbed through the skin or the digestive tract into the bloodstream over the long-term and are delivered to antigen-presenting cells in the skin, which provide the necessary signals for mast cell activation. Nonetheless, the reasons for a selectively cutaneous localization of the reaction remain largely unclear.

Management of CU is debated among physicians, and several diagnostic flowcharts have been proposed.1,2 In general, patch tests for contact dermatitis are not recommended as a fundamental part of the diagnostic procedure, but Guerra et al17 suggested that contact allergy often plays a role in CU.

There have been inadequate reports of CU found to be caused by common contact sensitizers.21-24 Interestingly, no signs of contact allergy were demonstrated in CU patients before urticarial attack.

Our findings supported our patient selection criteria and also confirmed that contact sensitization may be one of the many possible mechanisms involved in the etiology of CU. Urticaria may have a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction element, and patients with CU without an obvious causal factor can have positive patch test results.

The

The main findings of our study were that 53.4% of patients with CIU had positive patch test results and that avoidance of the sensitizing substance was effective in 5 of 8 patients who completed an avoidance program. Almost all of the patients showed notable remission of symptoms after limiting their exposure to the offending allergens. This study clearly showed that a cause or pathogenesis for CIU could be identified, thus showing that CIU occurs less frequently than is usually assumed.

Our study had limitations. The first is our lack of a controlled challenge test, which is important to confirm an allergen as a cause of CIU.26 Nonetheless, avoidance of the revealed contact allergen was associated with comparable improvement of CIU severity after 1 month in 5 of 8 patients, though such measures were not tested in all 31 of 58 CIU patients who had positive patch test results.

Conclusion

We propose that patch tests should be performed while investigating CU because they give effective diagnostic and therapeutic results in a substantial number of patients. Urticaria, or at least a subgroup of the disease, may have a delayed-type reaction element, which may explain the disease etiology for many CIU patients. Patients with CU without a detectable underlying etiologic factor can have positive patch test results.

Chronic urticaria (CU) is clinically defined as the daily or almost daily presence of wheals on the skin for at least 6 weeks.1 Chronic urticaria severely affects patients’ quality of life and can cause emotional disability and distress.2 In clinical practice, CU is one of the most common and challenging conditions for general practitioners, dermatologists, and allergists. It can be provoked by a wide variety of different causes or may be the clinical presentation of certain systemic diseases3,4; thus, CU often requires a detailed and time-consuming diagnostic procedure that includes screening for allergies, autoimmune diseases, parasites, malignancies, infections, and metabolic disorders.5,6 In many patients (up to 50% in some case series), the cause or pathogenic mechanism cannot be identified, and the disease is then classified as chronic idiopathic urticaria (CIU).7

It has previously been shown that contact sensitization could have some relation with CIU,8 which was further explored in this study. This study sought to evaluate if contact allergy may play a role in disease development in CIU patients in Saudi Arabia and if patch testing should be routinely performed for CIU patients to determine if any allergens can be avoided.

Methods

This prospective study was conducted at the King Khalid University Hospital Allergy Clinic (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia) in patients aged 18 to 60 years who had CU for more than 6 weeks. It was a clinic-based study conducted over a period of 2 years (March 2010 to February 2012). The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee at King Khalid University Hospital. Valid written consent was obtained from each patient.

Patients were excluded if they had CU caused by physical factors (eg, hot or cold temperature, water, physical contact) or drug reactions that were possible causative factors or if they had taken oral prednisolone or other oral immunosuppressive drugs (eg, azathioprine, cyclosporine) in the last month. However, patients taking antihistamines were not excluded because it was impossible for the patients to discontinue their urticaria treatment. Other exclusion criteria included CU associated with any systemic disease, thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune disorder, or atopic dermatitis. Pregnant and lactating women were not included in this study.

All new adult CU patients (ie, disease duration >6 weeks) were worked up using the routine diagnostic tests that are typically performed for any new CU patient, including complete blood cell count with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, liver function tests, urine analysis, and hepatitis B and C screenings. Further diagnostic tests also were carried out when appropriate according to the patient’s history and physical examination, including levels of urea, electrolytes, thyrotropin, thyroid antibodies (antithyroglobulin and antimicrosomal), and antinuclear antibodies, as well as a Helicobacter pylori test.

All of the patients enrolled in the study were evaluated by skin prick testing to establish the link between CU and its cause. Patch testing was performed in patients who were negative on skin prick testing.

Skin Prick Testing

All patients were advised to temporarily discontinue the use of antihistamines and corticosteroids 5 to 6 days prior to testing.

Patch Testing

Patch tests were carried out using a ready-to-use epicutaneous patch test system for the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).10 A European standard series was used with the addition of 4 allergens of local relevance: black seed oil, local perfume mix, henna, and myrrh (a topical herbal medicine used to promote healing).

Assessment of Improvement

Assessment of urticaria severity using the Chronic Urticaria Severity Score (CUSS), a simple semiquantitative assessment of disease activity, was calculated as the sum of the number of wheals and the degree of itch severity graded from 0 (none) to 3 (severe), according to the guidelines established by the Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology, the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network, the European Dermatology Forum, and the World Allergy Organization.11 The avoidance group of patients was assessed at baseline and after 1 month to evaluate changes in their CUSS after allergen avoidance for 8 weeks.

Statistical Analysis

All of the statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software version 16. Results were presented as the median with the range or the mean (SD).

Results

During the study period, a total of 120 CU patients were seen at the clinic. Ninety-three patients with CU met our selection criteria (77.5%) and were enrolled in the study. The mean age (SD) of the patients was 34.7 (12.4) years. Women comprised 68.8% (64/93) of the study population (Table 1).

The duration of urticaria ranged from 0.6 to 20 years, with a median duration of 4 years. Approximately half of the patients (50/93) experienced severe symptoms of urticaria, but only 26.9% (25/93) had graded their urticaria as very severe.

Negative results from the skin prick test were reported in 62.4% (58/93) of patients and were subsequently patch tested. These patients also had no other etiologic factors (eg, infection; thyroid, autoimmune, or metabolic disease). Patients who had positive skin prick test results (35/93 [37.6%]) were not considered to be cases of CIU, according to diagnostic recommendations.12 Of the 58 CIU patients who were patch tested, 31 (53.4%) had positive results and 27 (46.5%) had negative results to both skin prick and patch tests (Figure).

Univariate analysis revealed significant associations between age, gender, and duration of urticaria and patch test positivity (χ2 test, P<.05). T

Of the 31 patients with positive patch tests, there were 20 positive reactions to nickel, 6 to formaldehyde, 4 to phenylenediamine, 3 to cobalt, and 3 to a fragrance mix (Table 2). Some patients showed patch test reactivity to more than 1 allergen concomitantly. Overall, these 31 patients had positive reactions to 16 allergens. None of the patients showed actual signs of contact dermatitis (Table 2).

Of

Comment

Chronic idiopathic urticaria is the diagnosis given when urticarial vasculitis, physical urticaria, and all other possible etiologic factors have been excluded in patients with CU. Our study was designed to assess patch test reactivity in patients with CU without any identifiable systemic etiologic factor after detailed laboratory testing and negative skin prick tests.

Chronic idiopathic urticaria can be an extremely disabling and difficult-to-treat condition. Because the cause is unknown, the management of CIU often is frustrating. The

Patch testing is commonly performed to diagnose ACD, and if contact allergens are found via patch testing, patients can often be cured of their dermatitis by avoiding these agents. However, patch testing is not routinely performed in the evaluation of patients with CIU. It is a relatively inexpensive and safe procedure to determine a causal link between sensitization to a specific agent and ACD. In patch test clinics, agents often are tested in standard and screening series. Sensitization that is not suspected from the patient’s history and/or clinical examination can be detected in this manner. Requirements for the inclusion of a chemical in a standard series have been formulated by Bruze et al.13 In addition, ready-to-use materials relevant to the specific leisure activities and working conditions also can be selected for patch testing.

A study conducted in Saudi Arabia showed that the European standard series is suitable for patch testing patients in this community14; however, 3 allergens of local relevance were added in our study: black seed oil, local perfume mix, and henna. Moreover, in our study we added a local allergen known as myrrh, which is a topical herbal medicine used to promote healing that has been reported to cause ACD in some cases.15 We sought to determine if contact allergens can be identified with patch testing in patients with CU and if avoiding these contact allergens would resolve the CU.

Urticaria was once considered an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reaction, but recent studies have demonstrated the existence of different subgroupsof urticaria, some with an autoimmune mechanism.1-4,11 In CU, skin prick tests are recommended for etiologic workup, while patch testing generally is not recommended.16

It has been observed in clinical practice that a substantial number of patients with CU are positive to patch tests, even without a clear clinical history or signs of contact dermatitis.17 In 2007, Guerra et al17 reported that of 121 patients with CU, 50 (41.3%) tested positive for contact allergens. In all of the patch test–positive patients, avoidance measures led to complete remission within 10 days to 1 month. Therefore, this result suggested that testing for contact sensitization could be helpful in the management of CU. Patients with nickel sensitivity were subsequently allowed to ingest small amounts of nickel-containing foods after 8 weeks of a completely nickel-free diet, and remission persisted.17

Contact dermatitis affects approximately 20% of the general population18; however, there has been little investigation (limited to nickel) into the relationship between contact allergens and CU,19,20 and the underlying mechanisms of the disease are unknown. It has been hypothesized that small amounts of the substances are absorbed through the skin or the digestive tract into the bloodstream over the long-term and are delivered to antigen-presenting cells in the skin, which provide the necessary signals for mast cell activation. Nonetheless, the reasons for a selectively cutaneous localization of the reaction remain largely unclear.

Management of CU is debated among physicians, and several diagnostic flowcharts have been proposed.1,2 In general, patch tests for contact dermatitis are not recommended as a fundamental part of the diagnostic procedure, but Guerra et al17 suggested that contact allergy often plays a role in CU.

There have been inadequate reports of CU found to be caused by common contact sensitizers.21-24 Interestingly, no signs of contact allergy were demonstrated in CU patients before urticarial attack.

Our findings supported our patient selection criteria and also confirmed that contact sensitization may be one of the many possible mechanisms involved in the etiology of CU. Urticaria may have a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction element, and patients with CU without an obvious causal factor can have positive patch test results.

The

The main findings of our study were that 53.4% of patients with CIU had positive patch test results and that avoidance of the sensitizing substance was effective in 5 of 8 patients who completed an avoidance program. Almost all of the patients showed notable remission of symptoms after limiting their exposure to the offending allergens. This study clearly showed that a cause or pathogenesis for CIU could be identified, thus showing that CIU occurs less frequently than is usually assumed.

Our study had limitations. The first is our lack of a controlled challenge test, which is important to confirm an allergen as a cause of CIU.26 Nonetheless, avoidance of the revealed contact allergen was associated with comparable improvement of CIU severity after 1 month in 5 of 8 patients, though such measures were not tested in all 31 of 58 CIU patients who had positive patch test results.

Conclusion

We propose that patch tests should be performed while investigating CU because they give effective diagnostic and therapeutic results in a substantial number of patients. Urticaria, or at least a subgroup of the disease, may have a delayed-type reaction element, which may explain the disease etiology for many CIU patients. Patients with CU without a detectable underlying etiologic factor can have positive patch test results.

- Zuberbier T, Bindslev-Jensen C, Canonica W, et al. Guidelines, definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2006;61:316-331.

- Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria: pathogenesis and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:465-474.

- Champion RH. Urticaria: then and now. Br J Dermatol. 1988;119:427-436.

- Green GA, Koelsche GA, Kierland R. Etiology and pathogenesis of chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy. 1965;23:30-36.

- Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria and angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:175-179.

- Dreskin SC, Andrews KY. The thyroid and urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:408-412.

- Greaves M. Chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:664-672.

- Sharma AD. Use of patch testing for identifying allergen causing chronic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:114-117.

- Li JT, Andrist D, Bamlet WR, et al. Accuracy of patient prediction of allergy skin test results. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:382-384.

- Nelson JL, Mowad CM. Allergic contact dermatitis: patch testing beyond the TRUE test. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:36-41.

- Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al; Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; European Dermatology Forum; World Allergy Organization. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1417-1426.

- Bindslev-Jensen C, Finzi A, Greaves M, et al. Chronic urticaria: diagnostic recommendations. Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:175-180.

- Bruze M, Conde-Slazar L, Goossens A, et al. Thoughts on sensitizers in a standard patch test series. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:241-250.

- Al-Sheikh OA, Gad El-Rab MO. Allergic contact dermatitis: clinical features and profile of sensitizing allergens in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:493-497.

- Al-Suwaidan SN, Gad El Rab MO, Al-Fakhiry S, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from myrrh, a topical herbal medicine used to promote healing. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:137.

- Henz BM, Zuberbier T. Causes of urticaria. In: Henz B, Zuberbier T, Grabbe J, et al, eds. Urticaria: Clinical Diagnostic and Therapeutic Aspects. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1998:19.

- Guerra L, Rogkakou A, Massacane P, et al. Role of contact sensitization in chronic urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:88-90.

- Thyssen JP, Linneberg A, Menné T, et al. The epidemiology of contact allergy in the general population—prevalence and main findings. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:287-299.

- Smart GA, Sherlock JC. Nickel in foods and the diet. Food Addit Contam. 1987;4:61-71.

- Abeck D, Traenckner I, Steinkraus V, et al. Chronic urticaria due to nickel intake. Acta Derm Venereol. 1993;73:438-439.

- Moneret-Vautrin DA. Allergic and pseudo-allergic reactions to foods in chronic urticaria [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130(Spec No 1):1S35-1S42.

- Wedi B, Raap U, Kapp A. Chronic urticaria and infections. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4:387-396.

- Foti C, Nettis E, Cassano N, et al. Acute allergic reactions to Anisakis simplex after ingestion of anchovies. Acta Derm Venerol. 2002;82:121-123.

- Uter W, Hegewald J, Aberer W, et al. The European standard series in 9 European countries, 2002/2003: first results of the European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:136-145.

- Magen E, Mishal J, Menachem S. Impact of contact sensitization in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:202-206.

- Antico A, Soana R. Chronic allergic-like dermatopathies in nickel sensitive patients: results of dietary restrictions and challenge with nickel salts. Allergy Asthma Proc. 1999;20:235-242.

- Zuberbier T, Bindslev-Jensen C, Canonica W, et al. Guidelines, definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2006;61:316-331.

- Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria: pathogenesis and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:465-474.

- Champion RH. Urticaria: then and now. Br J Dermatol. 1988;119:427-436.

- Green GA, Koelsche GA, Kierland R. Etiology and pathogenesis of chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy. 1965;23:30-36.

- Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria and angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:175-179.

- Dreskin SC, Andrews KY. The thyroid and urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:408-412.

- Greaves M. Chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:664-672.

- Sharma AD. Use of patch testing for identifying allergen causing chronic urticaria. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:114-117.

- Li JT, Andrist D, Bamlet WR, et al. Accuracy of patient prediction of allergy skin test results. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:382-384.

- Nelson JL, Mowad CM. Allergic contact dermatitis: patch testing beyond the TRUE test. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3:36-41.

- Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al; Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; European Dermatology Forum; World Allergy Organization. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1417-1426.

- Bindslev-Jensen C, Finzi A, Greaves M, et al. Chronic urticaria: diagnostic recommendations. Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:175-180.

- Bruze M, Conde-Slazar L, Goossens A, et al. Thoughts on sensitizers in a standard patch test series. Contact Dermatitis. 1999;41:241-250.

- Al-Sheikh OA, Gad El-Rab MO. Allergic contact dermatitis: clinical features and profile of sensitizing allergens in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:493-497.

- Al-Suwaidan SN, Gad El Rab MO, Al-Fakhiry S, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis from myrrh, a topical herbal medicine used to promote healing. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:137.

- Henz BM, Zuberbier T. Causes of urticaria. In: Henz B, Zuberbier T, Grabbe J, et al, eds. Urticaria: Clinical Diagnostic and Therapeutic Aspects. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1998:19.

- Guerra L, Rogkakou A, Massacane P, et al. Role of contact sensitization in chronic urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:88-90.

- Thyssen JP, Linneberg A, Menné T, et al. The epidemiology of contact allergy in the general population—prevalence and main findings. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:287-299.

- Smart GA, Sherlock JC. Nickel in foods and the diet. Food Addit Contam. 1987;4:61-71.

- Abeck D, Traenckner I, Steinkraus V, et al. Chronic urticaria due to nickel intake. Acta Derm Venereol. 1993;73:438-439.

- Moneret-Vautrin DA. Allergic and pseudo-allergic reactions to foods in chronic urticaria [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2003;130(Spec No 1):1S35-1S42.

- Wedi B, Raap U, Kapp A. Chronic urticaria and infections. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4:387-396.

- Foti C, Nettis E, Cassano N, et al. Acute allergic reactions to Anisakis simplex after ingestion of anchovies. Acta Derm Venerol. 2002;82:121-123.

- Uter W, Hegewald J, Aberer W, et al. The European standard series in 9 European countries, 2002/2003: first results of the European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies. Contact Dermatitis. 2005;53:136-145.

- Magen E, Mishal J, Menachem S. Impact of contact sensitization in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:202-206.

- Antico A, Soana R. Chronic allergic-like dermatopathies in nickel sensitive patients: results of dietary restrictions and challenge with nickel salts. Allergy Asthma Proc. 1999;20:235-242.

Practice Points

- Patients with chronic urticaria (CU) without a detectable underlying etiologic factor can have positive patch test results.

- Avoidance of the sensitizing substance can be effective in CU patients and remission of symptoms can be possible after limiting their exposure to the offending allergens.