User login

Wolf in sheep’s clothing: metatarsal osteosarcoma

Metatarsal bones are an unusual subsite for small bone involvement in osteosarcomas. This subgroup is often misdiagnosed and hence associated with significant treatment delays. The standard treatment of metatarsal osteosarcomas remains the same as for those treated at other sites, namely neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. Limb salvage surgery or metatarsectomy in the foot is often a challenge owing to the poor compartmentalization of the disease. We hereby describe the case of a young girl with a metatarsal osteosarcoma who was managed with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and limb salvage surgery.

Introduction

Osteosarcomas are the most common primary malignant bone tumor in children and adolescents. Although predominantly occurring in pediatric and adolescent age groups, bimodal distribution (with a second incidence peak occurring in the sixth and seventh decades) is not uncommon.1 Osteosarcomas of the foot and small bones represent a rare and distinct clinical entity. This must have been a well-known observation for years that led to Watson-Jones stating, “Sarcoma of this [metatarsal] bone has not yet been reported in thousands of years in any country.”2 The incidence of osteosarcomas of the foot is estimated to be from 0.2% to 2%.3

These tumors, owing to their rarity, often lead to diagnostic dilemmas and hence treatment delays.4 They are usually mistaken for inflammatory conditions and often treated with—but not limited to—curettages and drainage procedures.5 The following case of osteosarcoma of the metatarsal bone in a young girl highlights the importance of having a high index of clinical suspicion prior to treatment.

Case Presentation and Summary

A 10-year-old girl visited our outpatient clinic with a painful progressive swelling on the dorsum of the left foot of 2 months’ duration. There was no history of antecedent trauma or fever. Physical examination revealed a bony hard swelling measuring around 5 x 6 cm on the dorsum of the left foot around the region of the second metatarsal. There was no regional lymphadenopathy or distal neurovascular deficit. She was evaluated with a plain radiograph that demonstrated a lytic lesion in the left second metatarsal associated with cortical destruction and periosteal reaction (Figure 1). A subsequent magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed a bony lesion destroying part of the left second metatarsal with cortical destruction and marrow involvement and affecting the soft tissue around the adjacent third metatarsal (Figure 2). Needle biopsy showed chondroblastic osteosarcoma. Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax and bone scan were both negative for distant metastases.

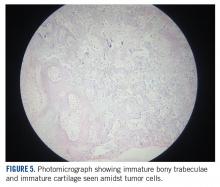

She received 3 cycles of a MAP (highdose methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin) regimen as neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Response assessment scans showed partial response (Figures 3A and B). We performed a wide excision of the second and third metatarsal with reconstruction using a segment of non-vascularized fibular graft as rigid fixation (Figure 4). The postoperative period was uneventful. She was able to begin partial weight bearing on the fourth postoperative day and her sutures were removed on the twelfth postoperative day. She received adjuvant chemotherapy following surgery. The final histopathology report showed residual disease with Huvos grade III response (>90% necrosis) with all margins negative for malignancy (Figure 5). At present, the child is disease-free at 5 months of treatment completion and is undergoing regular follow-up visits.

Discussion

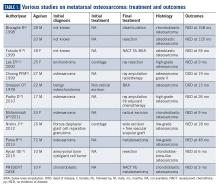

Metatarsal involvement amongst smallbone osteosarcomas is uncommon.3 There are about 32 cases of osteosarcomas reported in the literature from 1940 to 2018 involving the metatarsal bones (Table 1). According to a review article from the Mayo Clinic, the most common bone of the foot involved is the calcaneum.6 While the incidence of osteosarcomas of the foot as a whole is around 0.2% to 2%,3 metatarsal involvement is documented in 0.5% of these patients.7 However, a recent study depicted metatarsal involvement in 33% of all osteosarcomas of the foot.8

Osteosarcomas at conventional sites tend to have a bimodal age distribution with respect to disease affliction.9 Metatarsal osteosarcomas, however, are more common in an older age group.4,10 Our patient is probably the second youngest reported case of metatarsal osteosarcoma in the literature.11

Biscaglia et al propounded that osteosarcomas of the metatarsal were a distinct subgroup due to the rarity of occurrence, anatomical location, and prognosis.4 This often led to misdiagnosis and subsequent inadequate or inappropriate surgery. In six out of the ten cases (60%) described in Table 1, an incorrect pretreatment diagnosis was made that led to treatment delay. None, except one patient, received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which is currently the standard of care. The average duration from symptom onset to diagnosis was found to be 2 years.4 However, in our case, the duration of symptoms was approximately 2 months.

Surgery for metatarsal osteosarcomas can be challenging, as the compartments of the foot are narrow spaces with poor demarcation. Limb salvage surgery in the form of metatarsectomy needs proper preoperative planning and execution. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy will serve to downstage the tumor within the fascial barriers of the metatarsal compartment.It has also been postulated that osteosarcoma of the foot may have a better prognosis and survival compared to other osteosarcoma subsites.10 This can be extrapolated from the fact that the majority are found to be low grade, and despite a long delay in treatment, there was no rapid increase in size and/or metastatic spread. However, tumor grade remains an important factor affecting survival— patients with higher grade tumors have worse survival.8

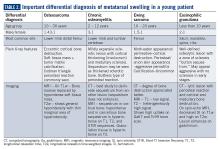

A number of differentials, including benign tumors, are to be kept in mind when diagnosing and treating such patients (Table 2). The most common benign tumors affecting the metatarsal are giant cell tumors (GCT) followed by chondromyxoid fibroma. Osteosarcomas and Ewing sarcomas constitute the malignant tumors.12 Occasionally, infections like osteomyelitis of the small bones may mimic malignancy. The absence of an extensive soft tissue component and/or calcifications with the presence of bony changes (like sequestrum) favors a diagnosis of infection/osteomyelitis. In addition, clinical findings like fever, skin redness, and presence of a painful swelling (especially after onset of fever) point to an inflammatory pathology rather than malignancy. Stress fractures rarely simulate tumors. MRI showing marrow and soft tissue edema with a visible fracture line points to the diagnosis.

A plane radiograph showing cortical bone destruction with a soft tissue component and calcification should be considered suspicious and must be thoroughly evaluated prior to surgical treatment.13 In a young patient such as ours, the important differentials that need to be considered include Ewing sarcoma, chronic osteomyelitis, and eosinophilic granuloma, which can radiologically mimic osteosarcoma at this location.

Conclusions

Osteosarcoma of the metatarsal is rare. Our case remains unique as it reports the second youngest patient in the literature. Erroneous or delayed diagnosis resulting in inadequate tumor excision and limb loss (amputation) often occurs in a majority of the cases. Proper pretreatment radiological imaging becomes imperative, and when clinical suspicion is high, a needle biopsy must follow in those cases. Early diagnosis with administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy may allow us to perform limb salvage surgery or wide excision in these cases.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. Sithara Aravind, Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, Malabar Cancer Center, for the photomicrographs.

1. Ottaviani G, Jaffe N. The epidemiology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;152:3-13.

2. Watson-Jones R. Fractures and Joint Injuries. Vol. I, 4th ed. Edinburgh and London: E & S Livingstone Ltd.1960:347.

3. Wu KK. Osteogenic sarcoma of the tarsal navicular bone. J Foot Surg. 1989;28(4):363-369.

4. Biscaglia R, Gasbarrini A, Böhling T, Bacchini P, Bertoni F, Picci P. Osteosarcoma of the bones of the foot: an easily misdiagnosed malignant tumour. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73(9):842-847.

5. Kundu ZS, Gupta V, Sangwan SS, Rana P. Curettage of benign bone tumors and tumor like lesions: A retrospective analysis. Indian J Orthop. 2013;47(3):295-301.

6. Choong PFM, Qureshil AA, Sim FH, Unni KK. Osteosarcoma of the foot. A review of 52 patients at the Mayo Clinic. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70(4):361-364.

7. Sneppen O, Dissing I, Heerfordt J, Schiödt T. Osteosarcoma of the metatarsal bones: Review of the literature and report of a case. Acta Orthop Scand. 1978;49(2):220-223.

8. Anninga JK, Picci P, Fiocco M, et al. Osteosarcoma of the hands and feet: a distinct clinico-pathological subgroup. Virchows Arch. 2013;462(1):109-120.

9. Mirabello L, Troisi RJ, Savage SA. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. Cancer.

2009;115(7):1531-1543.

10. Wang CW, Chen CY, Yang RS. Talar osteosarcoma treated with limb sparing surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:e22.

11. Aycan OE, Vanel D, Righi A, Arikan Y, Manfrini M. Chondroblastoma-like osteosarcoma:

a case report and review. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44(6):869-873.

12. Jarkiewicz-Kochman E, Gołebiowski M, Swiatkowski J, Pacholec E, Rajewski R. Tumours of the metatarsus. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2007;9(3):319-330.

13. Schatz J, Soper J, McCormack S, Healy M, Deady L, Brown W. Imaging of tumours in the ankle and foot. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;21(1):37-50.

14. Fukuda K, Ushigome S, Nikaidou T, Asanuma K, Masui F. Osteosarcoma of the metatarsal. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28(5):294-297.

15. Parsa R, Marcus M, Orlando R, Parsa C. Low-grade central osteosarcoma of the second metatarsal in a 72 year old male. Internet J Orthop Surg. 2013;21(2): 1-8.

16. Lee EY, Seeger LL, Nelson SD, Eckardt JJ. Primary osteosarcoma of a metatarsal bone. Skeletal Radiol. 2000;29(8):474-476.

17. Padhy D, Madhuri V, Pulimood SA, Danda S, Walter NM, Wang LL. Metatarsal osteosarcoma in Rothmund-Thomson syndrome: a case report. J Bone Joint

Surg Am. 2010;92(3):726-730.

18. Mohammadi A, Porghasem J, Noroozinia F, Ilkhanizadeh B, Ghasemi-Rad M, Khenari S. Periosteal osteosarcoma of the fifth metatarsal: A rare pedal tumor. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(5):620-622.

19. Nishio J, Iwasaki H, Takagi S, et al. Low-grade central osteosarcoma of the metatarsal bone: A clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic and molecular cytogenetic analysis. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(12):5429-5435.

Metatarsal bones are an unusual subsite for small bone involvement in osteosarcomas. This subgroup is often misdiagnosed and hence associated with significant treatment delays. The standard treatment of metatarsal osteosarcomas remains the same as for those treated at other sites, namely neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. Limb salvage surgery or metatarsectomy in the foot is often a challenge owing to the poor compartmentalization of the disease. We hereby describe the case of a young girl with a metatarsal osteosarcoma who was managed with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and limb salvage surgery.

Introduction

Osteosarcomas are the most common primary malignant bone tumor in children and adolescents. Although predominantly occurring in pediatric and adolescent age groups, bimodal distribution (with a second incidence peak occurring in the sixth and seventh decades) is not uncommon.1 Osteosarcomas of the foot and small bones represent a rare and distinct clinical entity. This must have been a well-known observation for years that led to Watson-Jones stating, “Sarcoma of this [metatarsal] bone has not yet been reported in thousands of years in any country.”2 The incidence of osteosarcomas of the foot is estimated to be from 0.2% to 2%.3

These tumors, owing to their rarity, often lead to diagnostic dilemmas and hence treatment delays.4 They are usually mistaken for inflammatory conditions and often treated with—but not limited to—curettages and drainage procedures.5 The following case of osteosarcoma of the metatarsal bone in a young girl highlights the importance of having a high index of clinical suspicion prior to treatment.

Case Presentation and Summary

A 10-year-old girl visited our outpatient clinic with a painful progressive swelling on the dorsum of the left foot of 2 months’ duration. There was no history of antecedent trauma or fever. Physical examination revealed a bony hard swelling measuring around 5 x 6 cm on the dorsum of the left foot around the region of the second metatarsal. There was no regional lymphadenopathy or distal neurovascular deficit. She was evaluated with a plain radiograph that demonstrated a lytic lesion in the left second metatarsal associated with cortical destruction and periosteal reaction (Figure 1). A subsequent magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed a bony lesion destroying part of the left second metatarsal with cortical destruction and marrow involvement and affecting the soft tissue around the adjacent third metatarsal (Figure 2). Needle biopsy showed chondroblastic osteosarcoma. Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax and bone scan were both negative for distant metastases.

She received 3 cycles of a MAP (highdose methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin) regimen as neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Response assessment scans showed partial response (Figures 3A and B). We performed a wide excision of the second and third metatarsal with reconstruction using a segment of non-vascularized fibular graft as rigid fixation (Figure 4). The postoperative period was uneventful. She was able to begin partial weight bearing on the fourth postoperative day and her sutures were removed on the twelfth postoperative day. She received adjuvant chemotherapy following surgery. The final histopathology report showed residual disease with Huvos grade III response (>90% necrosis) with all margins negative for malignancy (Figure 5). At present, the child is disease-free at 5 months of treatment completion and is undergoing regular follow-up visits.

Discussion

Metatarsal involvement amongst smallbone osteosarcomas is uncommon.3 There are about 32 cases of osteosarcomas reported in the literature from 1940 to 2018 involving the metatarsal bones (Table 1). According to a review article from the Mayo Clinic, the most common bone of the foot involved is the calcaneum.6 While the incidence of osteosarcomas of the foot as a whole is around 0.2% to 2%,3 metatarsal involvement is documented in 0.5% of these patients.7 However, a recent study depicted metatarsal involvement in 33% of all osteosarcomas of the foot.8

Osteosarcomas at conventional sites tend to have a bimodal age distribution with respect to disease affliction.9 Metatarsal osteosarcomas, however, are more common in an older age group.4,10 Our patient is probably the second youngest reported case of metatarsal osteosarcoma in the literature.11

Biscaglia et al propounded that osteosarcomas of the metatarsal were a distinct subgroup due to the rarity of occurrence, anatomical location, and prognosis.4 This often led to misdiagnosis and subsequent inadequate or inappropriate surgery. In six out of the ten cases (60%) described in Table 1, an incorrect pretreatment diagnosis was made that led to treatment delay. None, except one patient, received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which is currently the standard of care. The average duration from symptom onset to diagnosis was found to be 2 years.4 However, in our case, the duration of symptoms was approximately 2 months.

Surgery for metatarsal osteosarcomas can be challenging, as the compartments of the foot are narrow spaces with poor demarcation. Limb salvage surgery in the form of metatarsectomy needs proper preoperative planning and execution. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy will serve to downstage the tumor within the fascial barriers of the metatarsal compartment.It has also been postulated that osteosarcoma of the foot may have a better prognosis and survival compared to other osteosarcoma subsites.10 This can be extrapolated from the fact that the majority are found to be low grade, and despite a long delay in treatment, there was no rapid increase in size and/or metastatic spread. However, tumor grade remains an important factor affecting survival— patients with higher grade tumors have worse survival.8

A number of differentials, including benign tumors, are to be kept in mind when diagnosing and treating such patients (Table 2). The most common benign tumors affecting the metatarsal are giant cell tumors (GCT) followed by chondromyxoid fibroma. Osteosarcomas and Ewing sarcomas constitute the malignant tumors.12 Occasionally, infections like osteomyelitis of the small bones may mimic malignancy. The absence of an extensive soft tissue component and/or calcifications with the presence of bony changes (like sequestrum) favors a diagnosis of infection/osteomyelitis. In addition, clinical findings like fever, skin redness, and presence of a painful swelling (especially after onset of fever) point to an inflammatory pathology rather than malignancy. Stress fractures rarely simulate tumors. MRI showing marrow and soft tissue edema with a visible fracture line points to the diagnosis.

A plane radiograph showing cortical bone destruction with a soft tissue component and calcification should be considered suspicious and must be thoroughly evaluated prior to surgical treatment.13 In a young patient such as ours, the important differentials that need to be considered include Ewing sarcoma, chronic osteomyelitis, and eosinophilic granuloma, which can radiologically mimic osteosarcoma at this location.

Conclusions

Osteosarcoma of the metatarsal is rare. Our case remains unique as it reports the second youngest patient in the literature. Erroneous or delayed diagnosis resulting in inadequate tumor excision and limb loss (amputation) often occurs in a majority of the cases. Proper pretreatment radiological imaging becomes imperative, and when clinical suspicion is high, a needle biopsy must follow in those cases. Early diagnosis with administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy may allow us to perform limb salvage surgery or wide excision in these cases.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. Sithara Aravind, Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, Malabar Cancer Center, for the photomicrographs.

Metatarsal bones are an unusual subsite for small bone involvement in osteosarcomas. This subgroup is often misdiagnosed and hence associated with significant treatment delays. The standard treatment of metatarsal osteosarcomas remains the same as for those treated at other sites, namely neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. Limb salvage surgery or metatarsectomy in the foot is often a challenge owing to the poor compartmentalization of the disease. We hereby describe the case of a young girl with a metatarsal osteosarcoma who was managed with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and limb salvage surgery.

Introduction

Osteosarcomas are the most common primary malignant bone tumor in children and adolescents. Although predominantly occurring in pediatric and adolescent age groups, bimodal distribution (with a second incidence peak occurring in the sixth and seventh decades) is not uncommon.1 Osteosarcomas of the foot and small bones represent a rare and distinct clinical entity. This must have been a well-known observation for years that led to Watson-Jones stating, “Sarcoma of this [metatarsal] bone has not yet been reported in thousands of years in any country.”2 The incidence of osteosarcomas of the foot is estimated to be from 0.2% to 2%.3

These tumors, owing to their rarity, often lead to diagnostic dilemmas and hence treatment delays.4 They are usually mistaken for inflammatory conditions and often treated with—but not limited to—curettages and drainage procedures.5 The following case of osteosarcoma of the metatarsal bone in a young girl highlights the importance of having a high index of clinical suspicion prior to treatment.

Case Presentation and Summary

A 10-year-old girl visited our outpatient clinic with a painful progressive swelling on the dorsum of the left foot of 2 months’ duration. There was no history of antecedent trauma or fever. Physical examination revealed a bony hard swelling measuring around 5 x 6 cm on the dorsum of the left foot around the region of the second metatarsal. There was no regional lymphadenopathy or distal neurovascular deficit. She was evaluated with a plain radiograph that demonstrated a lytic lesion in the left second metatarsal associated with cortical destruction and periosteal reaction (Figure 1). A subsequent magnetic resonance image (MRI) revealed a bony lesion destroying part of the left second metatarsal with cortical destruction and marrow involvement and affecting the soft tissue around the adjacent third metatarsal (Figure 2). Needle biopsy showed chondroblastic osteosarcoma. Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax and bone scan were both negative for distant metastases.

She received 3 cycles of a MAP (highdose methotrexate, doxorubicin, and cisplatin) regimen as neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Response assessment scans showed partial response (Figures 3A and B). We performed a wide excision of the second and third metatarsal with reconstruction using a segment of non-vascularized fibular graft as rigid fixation (Figure 4). The postoperative period was uneventful. She was able to begin partial weight bearing on the fourth postoperative day and her sutures were removed on the twelfth postoperative day. She received adjuvant chemotherapy following surgery. The final histopathology report showed residual disease with Huvos grade III response (>90% necrosis) with all margins negative for malignancy (Figure 5). At present, the child is disease-free at 5 months of treatment completion and is undergoing regular follow-up visits.

Discussion

Metatarsal involvement amongst smallbone osteosarcomas is uncommon.3 There are about 32 cases of osteosarcomas reported in the literature from 1940 to 2018 involving the metatarsal bones (Table 1). According to a review article from the Mayo Clinic, the most common bone of the foot involved is the calcaneum.6 While the incidence of osteosarcomas of the foot as a whole is around 0.2% to 2%,3 metatarsal involvement is documented in 0.5% of these patients.7 However, a recent study depicted metatarsal involvement in 33% of all osteosarcomas of the foot.8

Osteosarcomas at conventional sites tend to have a bimodal age distribution with respect to disease affliction.9 Metatarsal osteosarcomas, however, are more common in an older age group.4,10 Our patient is probably the second youngest reported case of metatarsal osteosarcoma in the literature.11

Biscaglia et al propounded that osteosarcomas of the metatarsal were a distinct subgroup due to the rarity of occurrence, anatomical location, and prognosis.4 This often led to misdiagnosis and subsequent inadequate or inappropriate surgery. In six out of the ten cases (60%) described in Table 1, an incorrect pretreatment diagnosis was made that led to treatment delay. None, except one patient, received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which is currently the standard of care. The average duration from symptom onset to diagnosis was found to be 2 years.4 However, in our case, the duration of symptoms was approximately 2 months.

Surgery for metatarsal osteosarcomas can be challenging, as the compartments of the foot are narrow spaces with poor demarcation. Limb salvage surgery in the form of metatarsectomy needs proper preoperative planning and execution. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy will serve to downstage the tumor within the fascial barriers of the metatarsal compartment.It has also been postulated that osteosarcoma of the foot may have a better prognosis and survival compared to other osteosarcoma subsites.10 This can be extrapolated from the fact that the majority are found to be low grade, and despite a long delay in treatment, there was no rapid increase in size and/or metastatic spread. However, tumor grade remains an important factor affecting survival— patients with higher grade tumors have worse survival.8

A number of differentials, including benign tumors, are to be kept in mind when diagnosing and treating such patients (Table 2). The most common benign tumors affecting the metatarsal are giant cell tumors (GCT) followed by chondromyxoid fibroma. Osteosarcomas and Ewing sarcomas constitute the malignant tumors.12 Occasionally, infections like osteomyelitis of the small bones may mimic malignancy. The absence of an extensive soft tissue component and/or calcifications with the presence of bony changes (like sequestrum) favors a diagnosis of infection/osteomyelitis. In addition, clinical findings like fever, skin redness, and presence of a painful swelling (especially after onset of fever) point to an inflammatory pathology rather than malignancy. Stress fractures rarely simulate tumors. MRI showing marrow and soft tissue edema with a visible fracture line points to the diagnosis.

A plane radiograph showing cortical bone destruction with a soft tissue component and calcification should be considered suspicious and must be thoroughly evaluated prior to surgical treatment.13 In a young patient such as ours, the important differentials that need to be considered include Ewing sarcoma, chronic osteomyelitis, and eosinophilic granuloma, which can radiologically mimic osteosarcoma at this location.

Conclusions

Osteosarcoma of the metatarsal is rare. Our case remains unique as it reports the second youngest patient in the literature. Erroneous or delayed diagnosis resulting in inadequate tumor excision and limb loss (amputation) often occurs in a majority of the cases. Proper pretreatment radiological imaging becomes imperative, and when clinical suspicion is high, a needle biopsy must follow in those cases. Early diagnosis with administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy may allow us to perform limb salvage surgery or wide excision in these cases.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. Sithara Aravind, Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, Malabar Cancer Center, for the photomicrographs.

1. Ottaviani G, Jaffe N. The epidemiology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;152:3-13.

2. Watson-Jones R. Fractures and Joint Injuries. Vol. I, 4th ed. Edinburgh and London: E & S Livingstone Ltd.1960:347.

3. Wu KK. Osteogenic sarcoma of the tarsal navicular bone. J Foot Surg. 1989;28(4):363-369.

4. Biscaglia R, Gasbarrini A, Böhling T, Bacchini P, Bertoni F, Picci P. Osteosarcoma of the bones of the foot: an easily misdiagnosed malignant tumour. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73(9):842-847.

5. Kundu ZS, Gupta V, Sangwan SS, Rana P. Curettage of benign bone tumors and tumor like lesions: A retrospective analysis. Indian J Orthop. 2013;47(3):295-301.

6. Choong PFM, Qureshil AA, Sim FH, Unni KK. Osteosarcoma of the foot. A review of 52 patients at the Mayo Clinic. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70(4):361-364.

7. Sneppen O, Dissing I, Heerfordt J, Schiödt T. Osteosarcoma of the metatarsal bones: Review of the literature and report of a case. Acta Orthop Scand. 1978;49(2):220-223.

8. Anninga JK, Picci P, Fiocco M, et al. Osteosarcoma of the hands and feet: a distinct clinico-pathological subgroup. Virchows Arch. 2013;462(1):109-120.

9. Mirabello L, Troisi RJ, Savage SA. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. Cancer.

2009;115(7):1531-1543.

10. Wang CW, Chen CY, Yang RS. Talar osteosarcoma treated with limb sparing surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:e22.

11. Aycan OE, Vanel D, Righi A, Arikan Y, Manfrini M. Chondroblastoma-like osteosarcoma:

a case report and review. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44(6):869-873.

12. Jarkiewicz-Kochman E, Gołebiowski M, Swiatkowski J, Pacholec E, Rajewski R. Tumours of the metatarsus. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2007;9(3):319-330.

13. Schatz J, Soper J, McCormack S, Healy M, Deady L, Brown W. Imaging of tumours in the ankle and foot. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;21(1):37-50.

14. Fukuda K, Ushigome S, Nikaidou T, Asanuma K, Masui F. Osteosarcoma of the metatarsal. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28(5):294-297.

15. Parsa R, Marcus M, Orlando R, Parsa C. Low-grade central osteosarcoma of the second metatarsal in a 72 year old male. Internet J Orthop Surg. 2013;21(2): 1-8.

16. Lee EY, Seeger LL, Nelson SD, Eckardt JJ. Primary osteosarcoma of a metatarsal bone. Skeletal Radiol. 2000;29(8):474-476.

17. Padhy D, Madhuri V, Pulimood SA, Danda S, Walter NM, Wang LL. Metatarsal osteosarcoma in Rothmund-Thomson syndrome: a case report. J Bone Joint

Surg Am. 2010;92(3):726-730.

18. Mohammadi A, Porghasem J, Noroozinia F, Ilkhanizadeh B, Ghasemi-Rad M, Khenari S. Periosteal osteosarcoma of the fifth metatarsal: A rare pedal tumor. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(5):620-622.

19. Nishio J, Iwasaki H, Takagi S, et al. Low-grade central osteosarcoma of the metatarsal bone: A clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic and molecular cytogenetic analysis. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(12):5429-5435.

1. Ottaviani G, Jaffe N. The epidemiology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;152:3-13.

2. Watson-Jones R. Fractures and Joint Injuries. Vol. I, 4th ed. Edinburgh and London: E & S Livingstone Ltd.1960:347.

3. Wu KK. Osteogenic sarcoma of the tarsal navicular bone. J Foot Surg. 1989;28(4):363-369.

4. Biscaglia R, Gasbarrini A, Böhling T, Bacchini P, Bertoni F, Picci P. Osteosarcoma of the bones of the foot: an easily misdiagnosed malignant tumour. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73(9):842-847.

5. Kundu ZS, Gupta V, Sangwan SS, Rana P. Curettage of benign bone tumors and tumor like lesions: A retrospective analysis. Indian J Orthop. 2013;47(3):295-301.

6. Choong PFM, Qureshil AA, Sim FH, Unni KK. Osteosarcoma of the foot. A review of 52 patients at the Mayo Clinic. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70(4):361-364.

7. Sneppen O, Dissing I, Heerfordt J, Schiödt T. Osteosarcoma of the metatarsal bones: Review of the literature and report of a case. Acta Orthop Scand. 1978;49(2):220-223.

8. Anninga JK, Picci P, Fiocco M, et al. Osteosarcoma of the hands and feet: a distinct clinico-pathological subgroup. Virchows Arch. 2013;462(1):109-120.

9. Mirabello L, Troisi RJ, Savage SA. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. Cancer.

2009;115(7):1531-1543.

10. Wang CW, Chen CY, Yang RS. Talar osteosarcoma treated with limb sparing surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:e22.

11. Aycan OE, Vanel D, Righi A, Arikan Y, Manfrini M. Chondroblastoma-like osteosarcoma:

a case report and review. Skeletal Radiol. 2015;44(6):869-873.

12. Jarkiewicz-Kochman E, Gołebiowski M, Swiatkowski J, Pacholec E, Rajewski R. Tumours of the metatarsus. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2007;9(3):319-330.

13. Schatz J, Soper J, McCormack S, Healy M, Deady L, Brown W. Imaging of tumours in the ankle and foot. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;21(1):37-50.

14. Fukuda K, Ushigome S, Nikaidou T, Asanuma K, Masui F. Osteosarcoma of the metatarsal. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28(5):294-297.

15. Parsa R, Marcus M, Orlando R, Parsa C. Low-grade central osteosarcoma of the second metatarsal in a 72 year old male. Internet J Orthop Surg. 2013;21(2): 1-8.

16. Lee EY, Seeger LL, Nelson SD, Eckardt JJ. Primary osteosarcoma of a metatarsal bone. Skeletal Radiol. 2000;29(8):474-476.

17. Padhy D, Madhuri V, Pulimood SA, Danda S, Walter NM, Wang LL. Metatarsal osteosarcoma in Rothmund-Thomson syndrome: a case report. J Bone Joint

Surg Am. 2010;92(3):726-730.

18. Mohammadi A, Porghasem J, Noroozinia F, Ilkhanizadeh B, Ghasemi-Rad M, Khenari S. Periosteal osteosarcoma of the fifth metatarsal: A rare pedal tumor. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(5):620-622.

19. Nishio J, Iwasaki H, Takagi S, et al. Low-grade central osteosarcoma of the metatarsal bone: A clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic and molecular cytogenetic analysis. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(12):5429-5435.