User login

Psychotropic medications for chronic pain

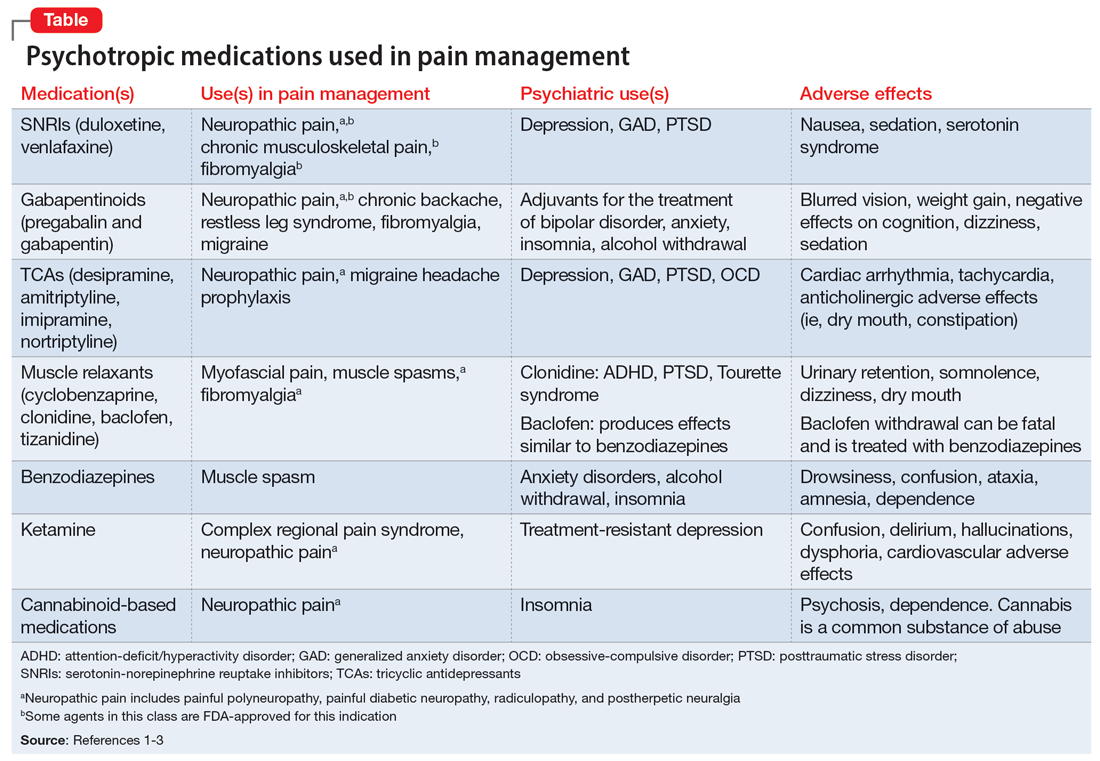

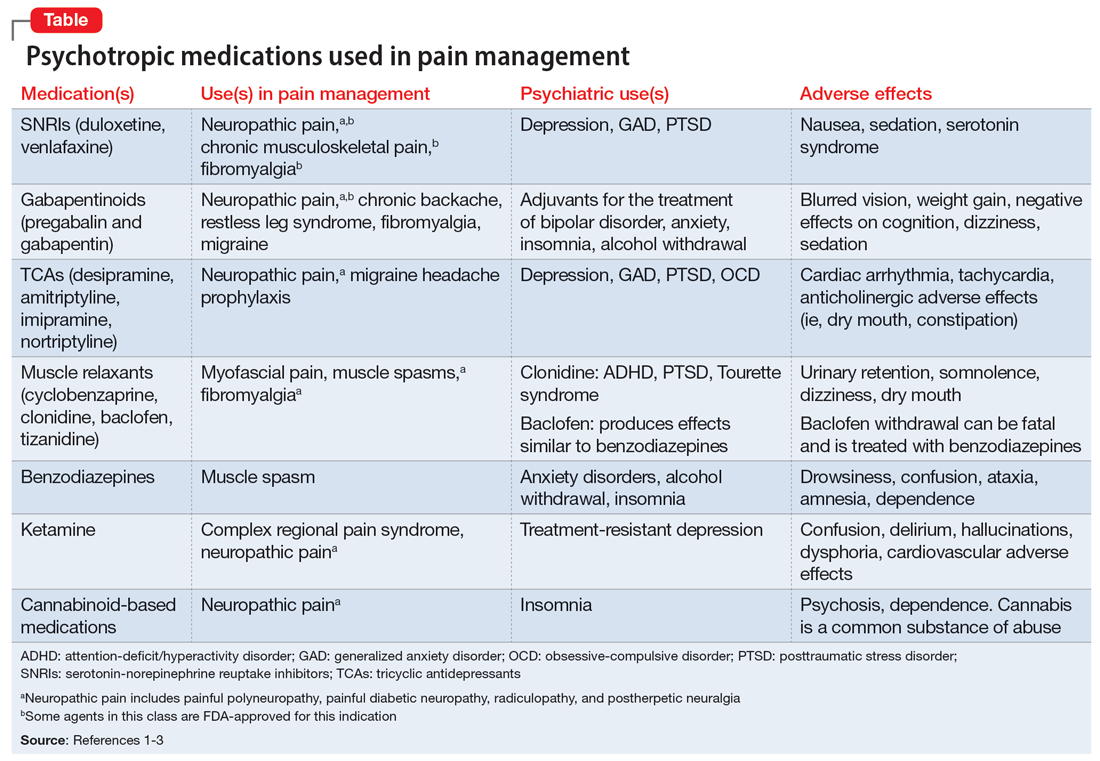

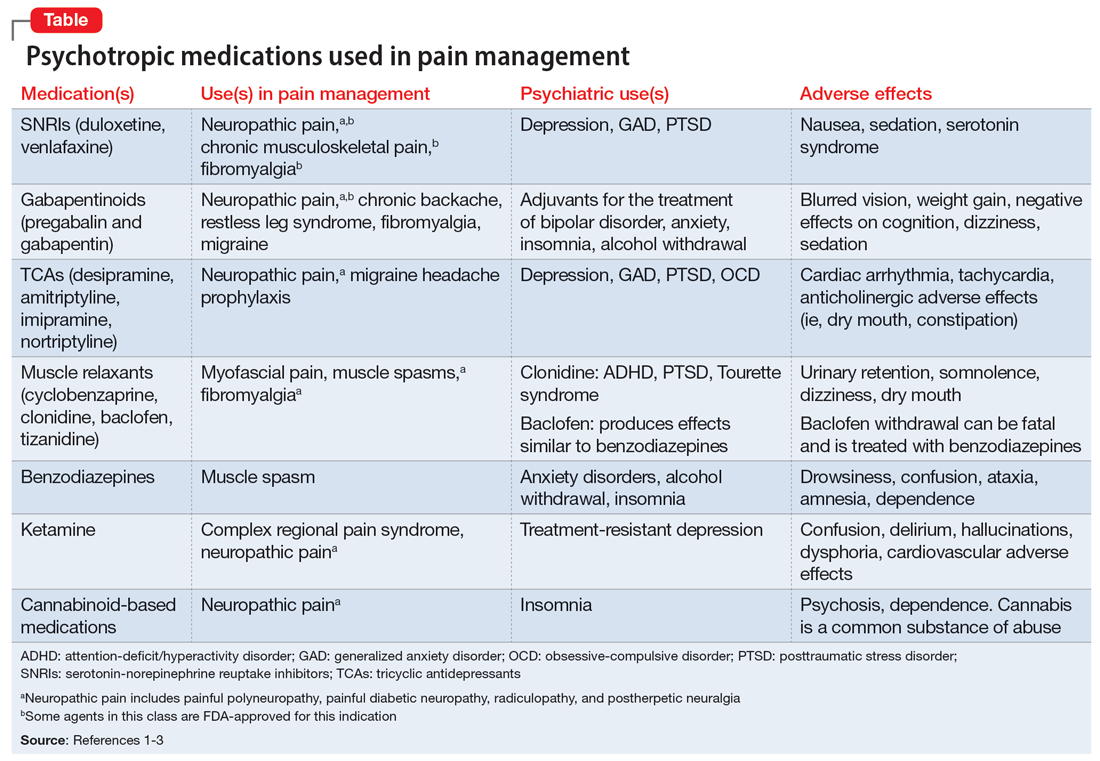

The opioid crisis presents a need to consider alternative options for treating chronic pain. There is significant overlap in neuroanatomical circuits that process pain, emotions, and motivation. Neurotransmitters modulated by psychotropic medications are also involved in regulating the pain pathways.1,2 In light of this, psychotropics can be considered for treating chronic pain in certain patients. The Table1-3 outlines various uses and adverse effects of select psychotropic medications used to treat pain, as well as their psychiatric uses.

In addition to its psychiatric indications, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain. It is often prescribed in the treatment of multiple pain disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have the largest effect size in the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Cyclobenzaprine is a TCA used to treat muscle spasms. Gabapentinoids (alpha-2 delta-1 calcium channel inhibition) are FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathy.1,2

Ketamine is an anesthetic with analgesic and antidepressant properties used as an IV infusion to manage several pain disorders.2 The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists tizanidine and clonidine are muscle relaxants2; the latter is used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette syndrome. Benzodiazepines (GABA-A agonists) are used for short-term treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and muscle spasms.1,2 Baclofen (GABA-B receptor agonist) is used to treat spasticity.2 Medical cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol) is also gaining popularity for treating chronic pain and insomnia.1-3

1. Sutherland AM, Nicholls J, Bao J, et al. Overlaps in pharmacology for the treatment of chronic pain and mental health disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):290-297.

2. Bajwa ZH, Wootton RJ, Warfield CA. Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2016.

3. McDonagh MS, Selph SS, Buckley DI, et al. Nonopioid Pharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 228. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER228

The opioid crisis presents a need to consider alternative options for treating chronic pain. There is significant overlap in neuroanatomical circuits that process pain, emotions, and motivation. Neurotransmitters modulated by psychotropic medications are also involved in regulating the pain pathways.1,2 In light of this, psychotropics can be considered for treating chronic pain in certain patients. The Table1-3 outlines various uses and adverse effects of select psychotropic medications used to treat pain, as well as their psychiatric uses.

In addition to its psychiatric indications, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain. It is often prescribed in the treatment of multiple pain disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have the largest effect size in the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Cyclobenzaprine is a TCA used to treat muscle spasms. Gabapentinoids (alpha-2 delta-1 calcium channel inhibition) are FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathy.1,2

Ketamine is an anesthetic with analgesic and antidepressant properties used as an IV infusion to manage several pain disorders.2 The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists tizanidine and clonidine are muscle relaxants2; the latter is used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette syndrome. Benzodiazepines (GABA-A agonists) are used for short-term treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and muscle spasms.1,2 Baclofen (GABA-B receptor agonist) is used to treat spasticity.2 Medical cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol) is also gaining popularity for treating chronic pain and insomnia.1-3

The opioid crisis presents a need to consider alternative options for treating chronic pain. There is significant overlap in neuroanatomical circuits that process pain, emotions, and motivation. Neurotransmitters modulated by psychotropic medications are also involved in regulating the pain pathways.1,2 In light of this, psychotropics can be considered for treating chronic pain in certain patients. The Table1-3 outlines various uses and adverse effects of select psychotropic medications used to treat pain, as well as their psychiatric uses.

In addition to its psychiatric indications, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor duloxetine is FDA-approved for treating fibromyalgia and diabetic neuropathic pain. It is often prescribed in the treatment of multiple pain disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have the largest effect size in the treatment of neuropathic pain.2 Cyclobenzaprine is a TCA used to treat muscle spasms. Gabapentinoids (alpha-2 delta-1 calcium channel inhibition) are FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia, fibromyalgia, and diabetic neuropathy.1,2

Ketamine is an anesthetic with analgesic and antidepressant properties used as an IV infusion to manage several pain disorders.2 The alpha-2 adrenergic agonists tizanidine and clonidine are muscle relaxants2; the latter is used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette syndrome. Benzodiazepines (GABA-A agonists) are used for short-term treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and muscle spasms.1,2 Baclofen (GABA-B receptor agonist) is used to treat spasticity.2 Medical cannabis (tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol) is also gaining popularity for treating chronic pain and insomnia.1-3

1. Sutherland AM, Nicholls J, Bao J, et al. Overlaps in pharmacology for the treatment of chronic pain and mental health disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):290-297.

2. Bajwa ZH, Wootton RJ, Warfield CA. Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2016.

3. McDonagh MS, Selph SS, Buckley DI, et al. Nonopioid Pharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 228. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER228

1. Sutherland AM, Nicholls J, Bao J, et al. Overlaps in pharmacology for the treatment of chronic pain and mental health disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):290-297.

2. Bajwa ZH, Wootton RJ, Warfield CA. Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2016.

3. McDonagh MS, Selph SS, Buckley DI, et al. Nonopioid Pharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 228. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. doi:10.23970/AHRQEPCCER228

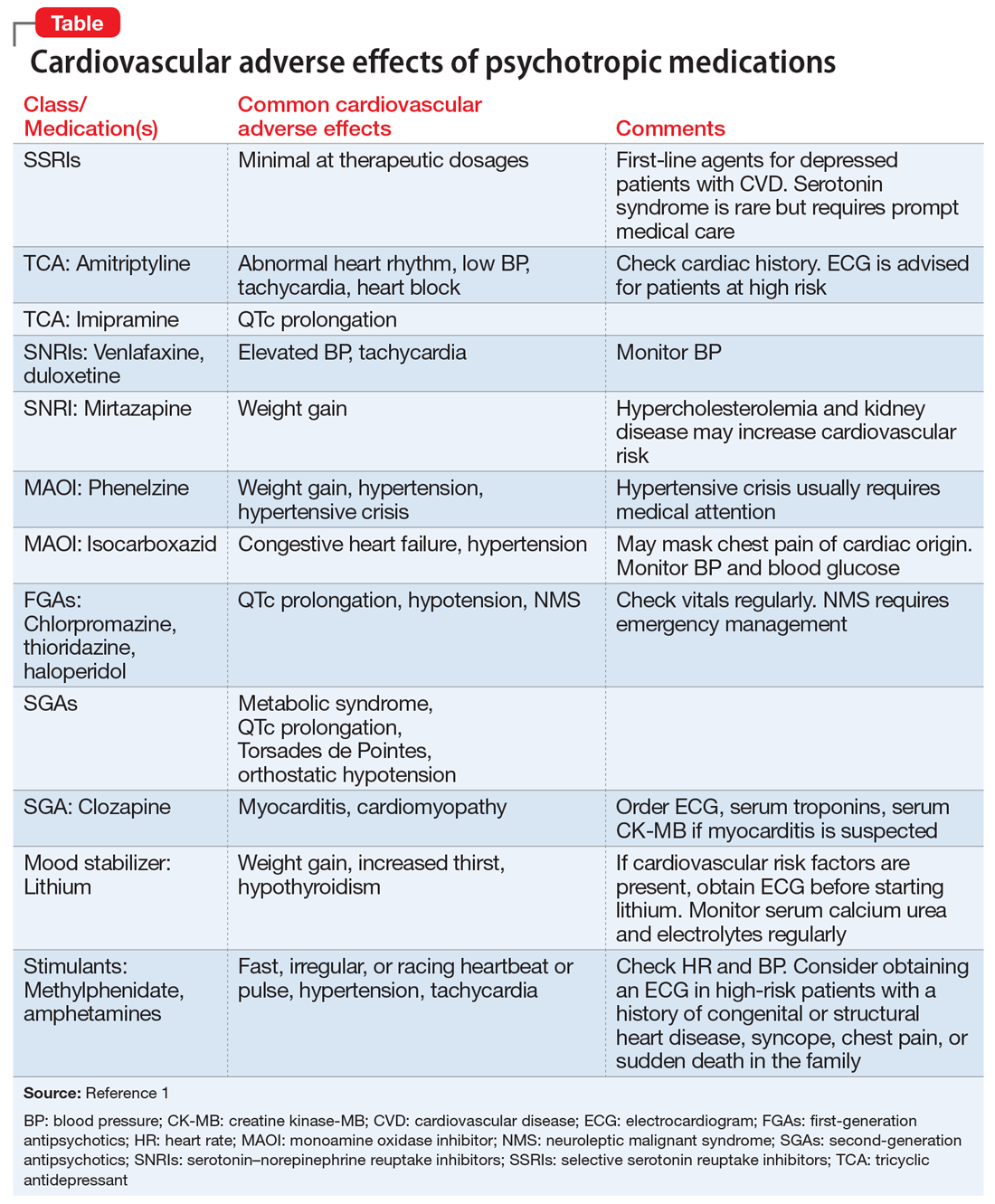

Cardiovascular adverse effects of psychotropics: What to look for

Most patients who take psychotropic medications are at low risk for cardiovascular adverse effects from these medications, and require only routine monitoring. However, patients with severe mental illness, those with a personal or family history of cardiovascular disease, or those receiving high doses or multiple medications are considered at high risk for morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular adverse effects. Such patients may need more careful cardiovascular monitoring.

To help identify important cardiovascular-related adverse effects of various psychotropics, we summarize these risks, and offer guidance about what you can do when your patient experiences them (Table).1

Antipsychotics and metabolic syndrome

Patients who take antipsychotics should be monitored for metabolic syndrome. The presence of 3 of the following 5 parameters is considered positive for metabolic syndrome2:

- fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥5.6%

- blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg

- triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL

- high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- waist circumference ≥102 cm in men or ≥88 cm in women.

Stimulants and sudden cardiac death

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) in children and adolescents who take stimulants to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is rare. For these patients, the risk of SCD is no higher than that of the general population.3 For patients who do not have any known cardiac risk factors, the American Academy of Pediatrics does not recommend performing any cardiac tests before starting stimulants.3

1. Mackin P. Cardiac side effects of psychiatric drugs. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(suppl 1):S3-S14.

2. Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, Cleeman JI, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(2):e13-e18.

3. American Academy of Pediatrics Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. Classifying recommendations for clinical practice guidelines. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):874-877.

Most patients who take psychotropic medications are at low risk for cardiovascular adverse effects from these medications, and require only routine monitoring. However, patients with severe mental illness, those with a personal or family history of cardiovascular disease, or those receiving high doses or multiple medications are considered at high risk for morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular adverse effects. Such patients may need more careful cardiovascular monitoring.

To help identify important cardiovascular-related adverse effects of various psychotropics, we summarize these risks, and offer guidance about what you can do when your patient experiences them (Table).1

Antipsychotics and metabolic syndrome

Patients who take antipsychotics should be monitored for metabolic syndrome. The presence of 3 of the following 5 parameters is considered positive for metabolic syndrome2:

- fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥5.6%

- blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg

- triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL

- high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- waist circumference ≥102 cm in men or ≥88 cm in women.

Stimulants and sudden cardiac death

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) in children and adolescents who take stimulants to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is rare. For these patients, the risk of SCD is no higher than that of the general population.3 For patients who do not have any known cardiac risk factors, the American Academy of Pediatrics does not recommend performing any cardiac tests before starting stimulants.3

Most patients who take psychotropic medications are at low risk for cardiovascular adverse effects from these medications, and require only routine monitoring. However, patients with severe mental illness, those with a personal or family history of cardiovascular disease, or those receiving high doses or multiple medications are considered at high risk for morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular adverse effects. Such patients may need more careful cardiovascular monitoring.

To help identify important cardiovascular-related adverse effects of various psychotropics, we summarize these risks, and offer guidance about what you can do when your patient experiences them (Table).1

Antipsychotics and metabolic syndrome

Patients who take antipsychotics should be monitored for metabolic syndrome. The presence of 3 of the following 5 parameters is considered positive for metabolic syndrome2:

- fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL or hemoglobin A1c ≥5.6%

- blood pressure ≥130/85 mm Hg

- triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL

- high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- waist circumference ≥102 cm in men or ≥88 cm in women.

Stimulants and sudden cardiac death

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) in children and adolescents who take stimulants to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is rare. For these patients, the risk of SCD is no higher than that of the general population.3 For patients who do not have any known cardiac risk factors, the American Academy of Pediatrics does not recommend performing any cardiac tests before starting stimulants.3

1. Mackin P. Cardiac side effects of psychiatric drugs. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(suppl 1):S3-S14.

2. Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, Cleeman JI, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(2):e13-e18.

3. American Academy of Pediatrics Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. Classifying recommendations for clinical practice guidelines. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):874-877.

1. Mackin P. Cardiac side effects of psychiatric drugs. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(suppl 1):S3-S14.

2. Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, Cleeman JI, et al; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(2):e13-e18.

3. American Academy of Pediatrics Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. Classifying recommendations for clinical practice guidelines. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):874-877.

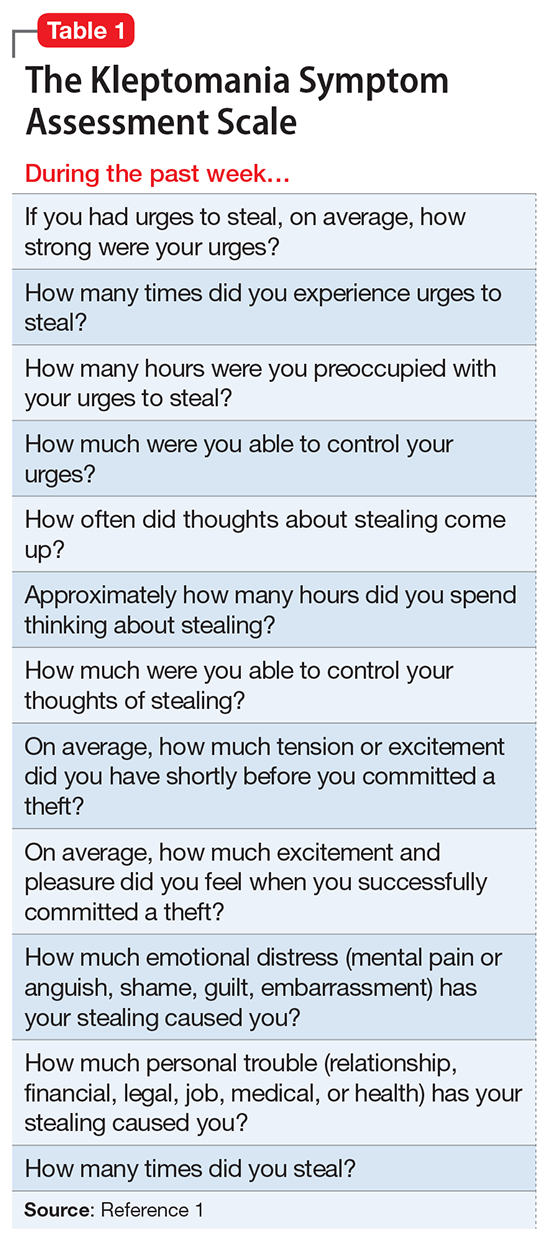

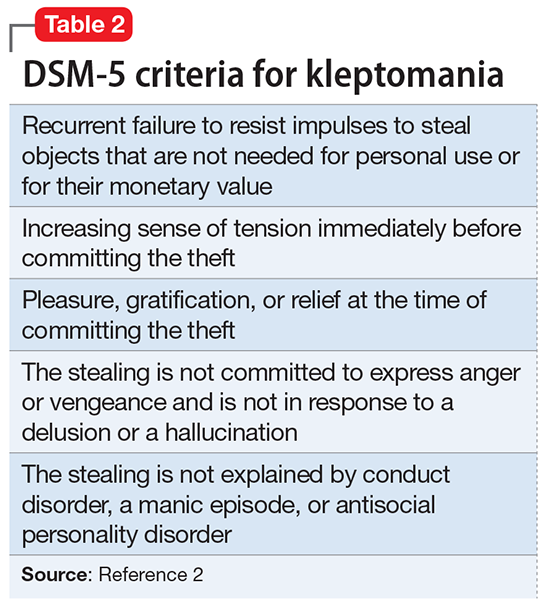

The girl who couldn’t stop stealing

CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

[polldaddy:9837962]

EVALUATION Continued stealing

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

The author’s observations

Risk-taking and novelty-seeking behaviors are common in adolescent patients. Impulsivity, instant reward-seeking behavior, and poor judgment can lead to stealing in this population, but this behavior is not necessarily indicative of kleptomania.

Kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects.2 It differs from other forms of stealing in that the objects stolen by a patient with kleptomania are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence, is found in about 0.5% of the general population, and is more common among females.3

There are 2 important theories to explain kleptomania:

- The psychoanalytical theory explains kleptomania as an immature defense against unconscious impulses, conflicts, and desires of destruction. By stealing, the individual protects the self from narcissistic injury and disintegration. The frantic search for objects helps to divert self-destructive aggressiveness and allows for the preservation of the self.4

- The biological model indicates that individuals with kleptomania have a significant deficit of white matter in inferior frontal regions and poor integrity of the tracts connecting the limbic system to the thalamus and to the prefrontal cortex.5 Reward system circuitry (ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbital frontal cortex) is likely to be involved in impulse control disorders including kleptomania.6

Comorbidity. Kleptomania often is comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and compulsive shopping, as well as depression, anxiety disorders, bulimia nervosa, and impulse control and conduct disorders.3,6

Kleptomania shares many characteristics with SUD, including continued engagement in a behavior despite negative consequences and the temporary reduction in urges after the behavior’s completion, followed by a return of the urge to steal. There also is a bidirectional relationship between OCD and kleptomania. Individuals with both disorders frequently engage in excessive and unnecessary rituals even when it is ego-dystonic. First-degree relatives of kleptomania patients have high rates of SUD and OCD.3

Serotonin, dopamine, and opioid pathways play a role in both kleptomania and other behavioral addictions.6 Clinicians should be cautious in treating comorbid disorders with stimulants. These agents may help patients with high impulsivity, but lead to disinhibition and worsen impulse control in patients with low impulsivity.7

TREATMENT Naltrexone

The psychiatrist discusses pharmacologic options to treat kleptomania with Ms. B and her mother. After considering the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternative treatments (including the option of no pharmacologic treatment), the mother consents and Ms. B assents to treatment with naltrexone, 25 mg/d. Before starting this medication, both the mother and Ms. B receive detailed psychoeducation describing naltrexone’s interactions with opioids. They are told that if Ms. B has a traumatic injury, they should inform the treatment team that she is taking naltrexone, which can acutely precipitate opiate withdrawal.

Before initiating pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive metabolic profile is obtained, and all values are within the normal range. After 1 week, naltrexone is increased to 50 mg/d. The medication is well tolerated, without any adverse effects.

[polldaddy:9837976]

The author’s observations

Behavioral interventions, such as covert sensitization and systemic desensitization, often are used to treat kleptomania.8 There are no FDA-approved medications for this condition. Opioid antagonists have been considered for the treatment of kleptomania.7

Mu-opioid receptors exist in highest concentrations in presynaptic neurons in the periaqueductal gray region and spinal cord and have high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. They also are involved in the reward and pleasure pathway. This neurocircuit is implicated in behavioral addiction.9

Naltrexone is an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors. It blocks the binding of endogenous and exogenous opioids at the receptors, particularly at the ventral tegmental area. By blocking the μ-receptor, naltrexone inhibits the processing of the reward and pleasure pathway involved in kleptomania. Naltrexone binds to these receptors, preventing the euphoric effects of behavioral addictions.10 This medication works best in conjunction with behavioral interventions.8

Naltrexone is a Schedule II drug. Use of naltrexone to treat kleptomania or other impulse control disorders is an off-label use of the medication. Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are receiving opiates because it can cause acute opiate withdrawal.

Liver function tests should be monitored in all patients taking naltrexone. If liver function levels begin to rise, naltrexone should be discontinued. Naltrexone should be used with caution in patients with preexisting liver disease.11

OUTCOME Marked improvement

Ms. B’s K-SAS scores are evaluated 2 weeks after starting naltrexone. The results show a marked reduction in the urge to steal and in stealing behavior, and Ms. B’s mother reports no incidents of stealing in the previous week.

Ms. B is maintained on naltrexone, 50 mg/d, for 2 months. On repeated K-SAS scores, her mother rates Ms. B’s symptoms “very much improved” with “occasional” stealing. Ms. B is discharged from the intensive outpatient program.

1. Christianini AR, Conti MA, Hearst N, et al. Treating kleptomania: cross-cultural adaptation of the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale and assessment of an outpatient program. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:289-294.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Talih FR. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: a review and case report. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):35-39.

4. Cierpka M. Psychodynamics of neurotically-induced kleptomania [in German]. Psychiatr Prax. 1986;13(3):94-103.

5. Grant JE, Correia S, Brennan-Krohn T. White matter integrity in kleptomania: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;147(2-3):233-237.

6. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

7. Zack M, Poulos CX. Effects of the atypical stimulant modafinil on a brief gambling episode in pathological gamblers with high vs. low impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6):660-671.

8. Grant JE. Understanding and treating kleptomania: new models and new treatments. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(2):81-87.

9. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):142-151.

10. Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):349-356.

11. Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson RL, et al. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:66-72.

CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

[polldaddy:9837962]

EVALUATION Continued stealing

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

The author’s observations

Risk-taking and novelty-seeking behaviors are common in adolescent patients. Impulsivity, instant reward-seeking behavior, and poor judgment can lead to stealing in this population, but this behavior is not necessarily indicative of kleptomania.

Kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects.2 It differs from other forms of stealing in that the objects stolen by a patient with kleptomania are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence, is found in about 0.5% of the general population, and is more common among females.3

There are 2 important theories to explain kleptomania:

- The psychoanalytical theory explains kleptomania as an immature defense against unconscious impulses, conflicts, and desires of destruction. By stealing, the individual protects the self from narcissistic injury and disintegration. The frantic search for objects helps to divert self-destructive aggressiveness and allows for the preservation of the self.4

- The biological model indicates that individuals with kleptomania have a significant deficit of white matter in inferior frontal regions and poor integrity of the tracts connecting the limbic system to the thalamus and to the prefrontal cortex.5 Reward system circuitry (ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbital frontal cortex) is likely to be involved in impulse control disorders including kleptomania.6

Comorbidity. Kleptomania often is comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and compulsive shopping, as well as depression, anxiety disorders, bulimia nervosa, and impulse control and conduct disorders.3,6

Kleptomania shares many characteristics with SUD, including continued engagement in a behavior despite negative consequences and the temporary reduction in urges after the behavior’s completion, followed by a return of the urge to steal. There also is a bidirectional relationship between OCD and kleptomania. Individuals with both disorders frequently engage in excessive and unnecessary rituals even when it is ego-dystonic. First-degree relatives of kleptomania patients have high rates of SUD and OCD.3

Serotonin, dopamine, and opioid pathways play a role in both kleptomania and other behavioral addictions.6 Clinicians should be cautious in treating comorbid disorders with stimulants. These agents may help patients with high impulsivity, but lead to disinhibition and worsen impulse control in patients with low impulsivity.7

TREATMENT Naltrexone

The psychiatrist discusses pharmacologic options to treat kleptomania with Ms. B and her mother. After considering the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternative treatments (including the option of no pharmacologic treatment), the mother consents and Ms. B assents to treatment with naltrexone, 25 mg/d. Before starting this medication, both the mother and Ms. B receive detailed psychoeducation describing naltrexone’s interactions with opioids. They are told that if Ms. B has a traumatic injury, they should inform the treatment team that she is taking naltrexone, which can acutely precipitate opiate withdrawal.

Before initiating pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive metabolic profile is obtained, and all values are within the normal range. After 1 week, naltrexone is increased to 50 mg/d. The medication is well tolerated, without any adverse effects.

[polldaddy:9837976]

The author’s observations

Behavioral interventions, such as covert sensitization and systemic desensitization, often are used to treat kleptomania.8 There are no FDA-approved medications for this condition. Opioid antagonists have been considered for the treatment of kleptomania.7

Mu-opioid receptors exist in highest concentrations in presynaptic neurons in the periaqueductal gray region and spinal cord and have high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. They also are involved in the reward and pleasure pathway. This neurocircuit is implicated in behavioral addiction.9

Naltrexone is an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors. It blocks the binding of endogenous and exogenous opioids at the receptors, particularly at the ventral tegmental area. By blocking the μ-receptor, naltrexone inhibits the processing of the reward and pleasure pathway involved in kleptomania. Naltrexone binds to these receptors, preventing the euphoric effects of behavioral addictions.10 This medication works best in conjunction with behavioral interventions.8

Naltrexone is a Schedule II drug. Use of naltrexone to treat kleptomania or other impulse control disorders is an off-label use of the medication. Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are receiving opiates because it can cause acute opiate withdrawal.

Liver function tests should be monitored in all patients taking naltrexone. If liver function levels begin to rise, naltrexone should be discontinued. Naltrexone should be used with caution in patients with preexisting liver disease.11

OUTCOME Marked improvement

Ms. B’s K-SAS scores are evaluated 2 weeks after starting naltrexone. The results show a marked reduction in the urge to steal and in stealing behavior, and Ms. B’s mother reports no incidents of stealing in the previous week.

Ms. B is maintained on naltrexone, 50 mg/d, for 2 months. On repeated K-SAS scores, her mother rates Ms. B’s symptoms “very much improved” with “occasional” stealing. Ms. B is discharged from the intensive outpatient program.

CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

[polldaddy:9837962]

EVALUATION Continued stealing

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

The author’s observations

Risk-taking and novelty-seeking behaviors are common in adolescent patients. Impulsivity, instant reward-seeking behavior, and poor judgment can lead to stealing in this population, but this behavior is not necessarily indicative of kleptomania.

Kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects.2 It differs from other forms of stealing in that the objects stolen by a patient with kleptomania are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence, is found in about 0.5% of the general population, and is more common among females.3

There are 2 important theories to explain kleptomania:

- The psychoanalytical theory explains kleptomania as an immature defense against unconscious impulses, conflicts, and desires of destruction. By stealing, the individual protects the self from narcissistic injury and disintegration. The frantic search for objects helps to divert self-destructive aggressiveness and allows for the preservation of the self.4

- The biological model indicates that individuals with kleptomania have a significant deficit of white matter in inferior frontal regions and poor integrity of the tracts connecting the limbic system to the thalamus and to the prefrontal cortex.5 Reward system circuitry (ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbital frontal cortex) is likely to be involved in impulse control disorders including kleptomania.6

Comorbidity. Kleptomania often is comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and compulsive shopping, as well as depression, anxiety disorders, bulimia nervosa, and impulse control and conduct disorders.3,6

Kleptomania shares many characteristics with SUD, including continued engagement in a behavior despite negative consequences and the temporary reduction in urges after the behavior’s completion, followed by a return of the urge to steal. There also is a bidirectional relationship between OCD and kleptomania. Individuals with both disorders frequently engage in excessive and unnecessary rituals even when it is ego-dystonic. First-degree relatives of kleptomania patients have high rates of SUD and OCD.3

Serotonin, dopamine, and opioid pathways play a role in both kleptomania and other behavioral addictions.6 Clinicians should be cautious in treating comorbid disorders with stimulants. These agents may help patients with high impulsivity, but lead to disinhibition and worsen impulse control in patients with low impulsivity.7

TREATMENT Naltrexone

The psychiatrist discusses pharmacologic options to treat kleptomania with Ms. B and her mother. After considering the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternative treatments (including the option of no pharmacologic treatment), the mother consents and Ms. B assents to treatment with naltrexone, 25 mg/d. Before starting this medication, both the mother and Ms. B receive detailed psychoeducation describing naltrexone’s interactions with opioids. They are told that if Ms. B has a traumatic injury, they should inform the treatment team that she is taking naltrexone, which can acutely precipitate opiate withdrawal.

Before initiating pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive metabolic profile is obtained, and all values are within the normal range. After 1 week, naltrexone is increased to 50 mg/d. The medication is well tolerated, without any adverse effects.

[polldaddy:9837976]

The author’s observations

Behavioral interventions, such as covert sensitization and systemic desensitization, often are used to treat kleptomania.8 There are no FDA-approved medications for this condition. Opioid antagonists have been considered for the treatment of kleptomania.7

Mu-opioid receptors exist in highest concentrations in presynaptic neurons in the periaqueductal gray region and spinal cord and have high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. They also are involved in the reward and pleasure pathway. This neurocircuit is implicated in behavioral addiction.9

Naltrexone is an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors. It blocks the binding of endogenous and exogenous opioids at the receptors, particularly at the ventral tegmental area. By blocking the μ-receptor, naltrexone inhibits the processing of the reward and pleasure pathway involved in kleptomania. Naltrexone binds to these receptors, preventing the euphoric effects of behavioral addictions.10 This medication works best in conjunction with behavioral interventions.8

Naltrexone is a Schedule II drug. Use of naltrexone to treat kleptomania or other impulse control disorders is an off-label use of the medication. Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are receiving opiates because it can cause acute opiate withdrawal.

Liver function tests should be monitored in all patients taking naltrexone. If liver function levels begin to rise, naltrexone should be discontinued. Naltrexone should be used with caution in patients with preexisting liver disease.11

OUTCOME Marked improvement

Ms. B’s K-SAS scores are evaluated 2 weeks after starting naltrexone. The results show a marked reduction in the urge to steal and in stealing behavior, and Ms. B’s mother reports no incidents of stealing in the previous week.

Ms. B is maintained on naltrexone, 50 mg/d, for 2 months. On repeated K-SAS scores, her mother rates Ms. B’s symptoms “very much improved” with “occasional” stealing. Ms. B is discharged from the intensive outpatient program.

1. Christianini AR, Conti MA, Hearst N, et al. Treating kleptomania: cross-cultural adaptation of the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale and assessment of an outpatient program. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:289-294.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Talih FR. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: a review and case report. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):35-39.

4. Cierpka M. Psychodynamics of neurotically-induced kleptomania [in German]. Psychiatr Prax. 1986;13(3):94-103.

5. Grant JE, Correia S, Brennan-Krohn T. White matter integrity in kleptomania: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;147(2-3):233-237.

6. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

7. Zack M, Poulos CX. Effects of the atypical stimulant modafinil on a brief gambling episode in pathological gamblers with high vs. low impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6):660-671.

8. Grant JE. Understanding and treating kleptomania: new models and new treatments. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(2):81-87.

9. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):142-151.

10. Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):349-356.

11. Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson RL, et al. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:66-72.

1. Christianini AR, Conti MA, Hearst N, et al. Treating kleptomania: cross-cultural adaptation of the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale and assessment of an outpatient program. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:289-294.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Talih FR. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: a review and case report. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):35-39.

4. Cierpka M. Psychodynamics of neurotically-induced kleptomania [in German]. Psychiatr Prax. 1986;13(3):94-103.

5. Grant JE, Correia S, Brennan-Krohn T. White matter integrity in kleptomania: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;147(2-3):233-237.

6. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

7. Zack M, Poulos CX. Effects of the atypical stimulant modafinil on a brief gambling episode in pathological gamblers with high vs. low impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6):660-671.

8. Grant JE. Understanding and treating kleptomania: new models and new treatments. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(2):81-87.

9. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):142-151.

10. Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):349-356.

11. Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson RL, et al. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:66-72.

Caution patients about common food–drug interactions

Many individuals read about the health benefits of certain foods, such as coffee, grapefruit, and red wine, but psychiatrists might neglect to inform their patients that these common foods could interact with drugs, thereby preventing certain psychotropics from achieving maximum benefit or causing toxicity. Educate your patients about food–drug interactions and to refrain from alcohol and specific foods when taking psychotropics. Although far from comprehensive, we present a discussion of the most frequently encountered and preventable food/nutrient–drug interactions.

Grapefruit juice may alter bioavailability of many psychotropics by inhibiting cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and 1A2 isoforms, interfering with prehepatic metabolism, and enteric absorption. Common medications affected by this interaction include alprazolam, buspirone, sertraline, carbamazepine, and methadone.1 Patients should be advised about eating grapefruit or drinking grapefruit juice as it could require dose adjustment to avoid drug toxicity.

Table salt. Lithium is a salt, and less table salt intake could cause lithium levels to rise and vice versa. Lithium and other salts compete for absorption and secretion in the renal tubules, which are responsible for this interaction. Therefore, it is advisable to keep a stable salt intake throughout treatment. Patients should be cautioned about eating salty foods during the summer because excessive sweating could lead to lithium intoxication.

Caffeine is a widely used stimulant; however, it can decrease blood lithium levels and block clozapine clearance via inhibition of the CYP1A2 enzyme. Excessive caffeine intake can lead to clozapine toxicity.2

Beef liver, aged sausage and cheese, and wine contain tyramine. Tyramine is broken down by monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzymes in the body, which are inhibited by MAO inhibitors (MAOI) such as phenelzine and selegiline. A patient taking a MAOI cannot catabolize tyramine and other amines. These exogenous amines could cause a life-threatening hyperadrenergic crisis. Physicians should educate their patients about the MAOI diet and monitor adherence to the food avoidance list.

St. John’s wort is a herb commonly used for treating mild depression. It is a strong inducer of the CYP3A4 enzyme and reduces plasma concentrations and could decrease clinical effectiveness of aripiprazole, quetiapine, alprazolam, and oxycodone.3 It could interact with serotonin reuptake inhibitors causing serotonin syndrome.

Full vs empty stomach. Food is known to affect bioavailability and enteral absorption of different psychotropics. Some medications are best taken on a full stomach and some on an empty one. For example, the antipsychotic ziprasidone should be taken with meals of at least 500 calories for optimal and consistent bioavailability. Benzodiazepines are rapidly absorbed when taken on an empty stomach.

Discuss dietary habits with patients to encourage a healthy lifestyle and provide valuable direction about potential food/nutrient–drug interactions.

1. Pawełczyk T, Kłoszewska I. Grapefruit juice interactions with psychotropic drugs: advantages and potential risk [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2008;62(2):92-95.

2. Hägg S, Spigset O, Mjörndal T, et al. Effect of caffeine on clozapine pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49(1):59-63.

3. Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, et al. Effect of St John’s wort on drug metabolism by induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1500-1504.

Many individuals read about the health benefits of certain foods, such as coffee, grapefruit, and red wine, but psychiatrists might neglect to inform their patients that these common foods could interact with drugs, thereby preventing certain psychotropics from achieving maximum benefit or causing toxicity. Educate your patients about food–drug interactions and to refrain from alcohol and specific foods when taking psychotropics. Although far from comprehensive, we present a discussion of the most frequently encountered and preventable food/nutrient–drug interactions.

Grapefruit juice may alter bioavailability of many psychotropics by inhibiting cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and 1A2 isoforms, interfering with prehepatic metabolism, and enteric absorption. Common medications affected by this interaction include alprazolam, buspirone, sertraline, carbamazepine, and methadone.1 Patients should be advised about eating grapefruit or drinking grapefruit juice as it could require dose adjustment to avoid drug toxicity.

Table salt. Lithium is a salt, and less table salt intake could cause lithium levels to rise and vice versa. Lithium and other salts compete for absorption and secretion in the renal tubules, which are responsible for this interaction. Therefore, it is advisable to keep a stable salt intake throughout treatment. Patients should be cautioned about eating salty foods during the summer because excessive sweating could lead to lithium intoxication.

Caffeine is a widely used stimulant; however, it can decrease blood lithium levels and block clozapine clearance via inhibition of the CYP1A2 enzyme. Excessive caffeine intake can lead to clozapine toxicity.2

Beef liver, aged sausage and cheese, and wine contain tyramine. Tyramine is broken down by monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzymes in the body, which are inhibited by MAO inhibitors (MAOI) such as phenelzine and selegiline. A patient taking a MAOI cannot catabolize tyramine and other amines. These exogenous amines could cause a life-threatening hyperadrenergic crisis. Physicians should educate their patients about the MAOI diet and monitor adherence to the food avoidance list.

St. John’s wort is a herb commonly used for treating mild depression. It is a strong inducer of the CYP3A4 enzyme and reduces plasma concentrations and could decrease clinical effectiveness of aripiprazole, quetiapine, alprazolam, and oxycodone.3 It could interact with serotonin reuptake inhibitors causing serotonin syndrome.

Full vs empty stomach. Food is known to affect bioavailability and enteral absorption of different psychotropics. Some medications are best taken on a full stomach and some on an empty one. For example, the antipsychotic ziprasidone should be taken with meals of at least 500 calories for optimal and consistent bioavailability. Benzodiazepines are rapidly absorbed when taken on an empty stomach.

Discuss dietary habits with patients to encourage a healthy lifestyle and provide valuable direction about potential food/nutrient–drug interactions.

Many individuals read about the health benefits of certain foods, such as coffee, grapefruit, and red wine, but psychiatrists might neglect to inform their patients that these common foods could interact with drugs, thereby preventing certain psychotropics from achieving maximum benefit or causing toxicity. Educate your patients about food–drug interactions and to refrain from alcohol and specific foods when taking psychotropics. Although far from comprehensive, we present a discussion of the most frequently encountered and preventable food/nutrient–drug interactions.

Grapefruit juice may alter bioavailability of many psychotropics by inhibiting cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and 1A2 isoforms, interfering with prehepatic metabolism, and enteric absorption. Common medications affected by this interaction include alprazolam, buspirone, sertraline, carbamazepine, and methadone.1 Patients should be advised about eating grapefruit or drinking grapefruit juice as it could require dose adjustment to avoid drug toxicity.

Table salt. Lithium is a salt, and less table salt intake could cause lithium levels to rise and vice versa. Lithium and other salts compete for absorption and secretion in the renal tubules, which are responsible for this interaction. Therefore, it is advisable to keep a stable salt intake throughout treatment. Patients should be cautioned about eating salty foods during the summer because excessive sweating could lead to lithium intoxication.

Caffeine is a widely used stimulant; however, it can decrease blood lithium levels and block clozapine clearance via inhibition of the CYP1A2 enzyme. Excessive caffeine intake can lead to clozapine toxicity.2

Beef liver, aged sausage and cheese, and wine contain tyramine. Tyramine is broken down by monoamine oxidase (MAO) enzymes in the body, which are inhibited by MAO inhibitors (MAOI) such as phenelzine and selegiline. A patient taking a MAOI cannot catabolize tyramine and other amines. These exogenous amines could cause a life-threatening hyperadrenergic crisis. Physicians should educate their patients about the MAOI diet and monitor adherence to the food avoidance list.

St. John’s wort is a herb commonly used for treating mild depression. It is a strong inducer of the CYP3A4 enzyme and reduces plasma concentrations and could decrease clinical effectiveness of aripiprazole, quetiapine, alprazolam, and oxycodone.3 It could interact with serotonin reuptake inhibitors causing serotonin syndrome.

Full vs empty stomach. Food is known to affect bioavailability and enteral absorption of different psychotropics. Some medications are best taken on a full stomach and some on an empty one. For example, the antipsychotic ziprasidone should be taken with meals of at least 500 calories for optimal and consistent bioavailability. Benzodiazepines are rapidly absorbed when taken on an empty stomach.

Discuss dietary habits with patients to encourage a healthy lifestyle and provide valuable direction about potential food/nutrient–drug interactions.

1. Pawełczyk T, Kłoszewska I. Grapefruit juice interactions with psychotropic drugs: advantages and potential risk [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2008;62(2):92-95.

2. Hägg S, Spigset O, Mjörndal T, et al. Effect of caffeine on clozapine pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49(1):59-63.

3. Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, et al. Effect of St John’s wort on drug metabolism by induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1500-1504.

1. Pawełczyk T, Kłoszewska I. Grapefruit juice interactions with psychotropic drugs: advantages and potential risk [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2008;62(2):92-95.

2. Hägg S, Spigset O, Mjörndal T, et al. Effect of caffeine on clozapine pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49(1):59-63.

3. Markowitz JS, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, et al. Effect of St John’s wort on drug metabolism by induction of cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1500-1504.

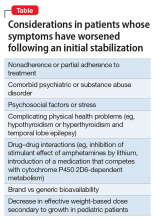

ADHD symptoms are stable, then a sudden relapse

CASE

Sudden deterioration

R, age 11, has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), combined type, and oppositional defiant disorder, which has been stable for more than a year on extended-release (ER) methylphenidate (brand name: Concerta), 54 mg/d (1.2 mg/kg). With combined pharmacotherapy and behavioral management, his symptoms of hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity improved at school and at home. He shows some academic gains as evidenced by improved achievement at school.

Over 2 months, R experiences a substantial deterioration in behavioral and academic performance. Along with core symptoms of ADHD, he begins to exhibit physical and verbal aggression. A report from school states that R has been using obscene language and destroying property, and has had episodes of provoked aggression toward his peers. His grades drop and he receives 2 school suspensions because of aggressive behavior.

What could be causing R’s ADHD symptoms to reemerge?

a) nonadherence to treatment

b) substance abuse

c) medication change

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

Worsening of psychiatric symptoms in a stable patient is relatively common. Many factors can contribute to patient destabilization. Treatment nonadherence is a leading cause, along with psychosocial stressors and substance use (Table).

EVALUATION

Adherence confirmed

R is hyperactive and distracted during his visit, a clear deterioration from his baseline status. R is oppositional and defiant toward his mother during the session, but shows good social skills when communicating with the physician.

R’s mother reports that her son seldom forgets to take his medication, and she ensures that he is swallowing the pill, rather than chewing it. Data from the prescription drug-monitoring program show that the family is filling the prescriptions regularly. The ER methylphenidate dosage is raised to 72 mg/d. The clinicians provide psychoeducation about adherence to a medication regimen to R and his family. Also, his parents and teachers receive Vanderbilt Assessment Scales for ADHD to assess the symptoms in different settings.

At a follow-up visit a week later, R’s mother reports that her son continues to have problems in school and at home. The Vanderbilt scales reveal that R is having clinically significant problems with attention, hyperactivity, impulse control, and oppositional behavior.

A urine drug screen is ordered to rule out the possibility of a sudden deterioration of ADHD symptoms secondary to substance use disorder. To ensure compliance, we recommend that R take his medication at the school nurse’s office in the morning.

A week later

Although R takes his medication at school, he continues to show core symptoms of ADHD without improvement. The urine drug screen is negative. A physical examination does not reveal any medical illness. The treatment team calls the pharmacist to obtain a complete list of medications R is taking, who confirms that he is only receiving ER methylphenidate, 72 mg/d. The pharmacist also notes that R’s medication was switched from the brand-name drug to a generic 3 months ago because of a change in insurance coverage. This change coincided with the reemergence of his ADHD symptoms.

R’s mother reports that the new pills do not look like the old ones even before the dosage was raised. A new brand-necessary prescription is sent to the pharmacy. With the brand-name medication, R’s symptoms quickly improve, and remain improved when the dosage is decreased to the previous dosage of 54 mg/d.

With osmotic-controlled release oral delivery system (OROS) and outer coating of ER methylphenidate, how much drug is released immediately vs slow release?

a) 22% immediate release and 78% slow release

b) 78% immediate release and 22% slow release

c) 50% immediate release and 50% slow release

The authors’ observations

Generic substitution of a brand medication can result in worsening of symptoms and increased adverse effects. Possible bioequivalence issues can lead to failure of drug therapy.1

In 2013, the FDA determined that 2 specific generic formulations of ER methylphenidate do not have therapeutic equivalency to the brand-name medication, Concerta. The FDA stated, “Based on an analysis of data, FDA has concerns about whether or not two approved generic versions of Concerta tablets (methylphenidate hydrochloride extended-release tablets), used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults and children, are therapeutically equiv

In an apparent confirmation of the FDA’s concerns, a case series of children and adolescents with ADHD observed that almost all of the patients showed symptom improvement when they switched from a non-OROS formulation to an OROS preparation at the same dosage.3

The OROS preparation is thought to provide more predictable medication delivery over an extended period of time (Figure). A patient taking an ER formulation without OROS might lose this benefit, which could lead to symptom destabilization, even if the patient is taking the medication as instructed.

Brand vs generic

Under FDA regulations, companies seeking approval for generic formulations of approved drugs must demonstrate that their products are the same as the brand-name drug in terms of:

- active ingredients

- strength

- dosage form

- route of administration

- packaging label.

In addition, the pharmaceutical company must demonstrate that the generic form is absorbed and distributed to the part of the body at which it has its effect at acceptably similar levels to the brand-name drug. All medications—new or generic, in clinical trials or approved, prescription or over-the-counter—must be manufactured under controlled conditions that assure product quality.

However, some studies have disputed this equivalency. In 1 study, patients with schizophrenia receiving generic olanzapine had lower serum concentration than patients with schizophrenia taking equivalent dosages of brand-name olanzapine.4 Similarly, studies comparing generic and brand-name venlafaxine showed significant differences in peak plasma concentration (Cmax)between generic and brand-name compounds.5

The FDA has considered upgrading the manufacturers’ warnings about the risk of generic medications, but has delayed the decision to 2017.6

FDA’s approval process for generic drugs

To receive approval of a generic formulation in the United States, the FDA requires that the generic drug should be compared with the corresponding brand-name drug in small crossover trials involving at least 24 to 36 healthy volunteers.

Bioequivalence is then established based on assessments of the rate of absorption (Cmax and area under the plasma concentration-time curve [AUC]). The FDA’s criteria are designed to achieve 90% confidence that the ratios of the test-to-reference log-transformed mean values for AUC and Cmax are within the interval of 80% to 125%. The FDA accepts −20% to 25% variation in Cmax and AUC in products that are considered bioequivalent. This is much less stringent than its −5% to 5% standard used for brand-name products. The FDA publishes a list of generic drugs that have been certified as bioequivalent, known as the “Orange Book.”5

Considerations when substituting generic medication

Because of the growing number of generic formulations of the same medication, generic–generic switches are becoming more commonplace. Theoretically, any 2 generic versions of the same medication can have a variation of up to 40% in AUC and Cmax. Generic medications are tested in healthy human controls through single-dose studies, which raises concerns about their applicability to the entire patient population.

Bioequivalence. It is a matter of debate whether bioequivalence translates to therapeutic equivalency. For medications with a narrow therapeutic index, the FDA has accepted that these 2 phenomena are not necessarily linked. With the exception of a few medications, including lithium and some anticonvulsants such as divalproex sodium and carbamazepine, serum level of the medications usually does not predict clinical response.

Inert ingredients. Generic medications can include inert ingredients (excipients) that are different from those in their branded counterparts. Some of these inactive ingredients can cause adverse effects. A study comparing paroxetine mesylate and paroxetine hydrochloride showed differences in bioequivalence and clinical efficacy.7

In some cases, brand-to-generic substitution can thwart clinical progress in a stable patient. This small change in the medication could destabilize the patient’s condition, which, in turn, may lead to unnecessary and significant social and financial burdens on the patient’s family, school, community, and the health care system.

Recommendations

In the event of a change in clinical response, clinicians first should evaluate adherence and explore other factors, such as biological, psychological, medical, and social issues. Adherence can be adversely affected by a change in the physical characteristics of the pill. Prescribers should remain cognizant of brand–generic and generic–generic switches. It may be reasonable to adjust the dosage of the new generic medication to address changes in clinical effectiveness.

If these strategies are ineffective, consider switching to a brand-name medication. Write “Dispense As Written” on the prescription to ensure delivery of the branded medication or a specific generic version of the medication.

An insurance company might require prior authorization to approve payment for the brand medication. To save time, use electronic forms or fax for communicating with the insurance company. Adding references to FDA statements and research papers, along with the patient’s history and presentations, would be prudent to demonstrate doubts about efficacy of the generic medication.

1. Atif M, Azeem M, Sarwar MR. Potential problems and recommendations regarding substitution of generic antiepileptic drugs: a systematic review of literature. Springerplus. 2016;5:182. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-1824-2.

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Methylphenidate hydrochloride extended release tablets (generic Concerta) made by Mallinckrodt and Kudco. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm422568.htm. Updated November 13, 2014. Accessed August 29, 2016.

3. Lally MD, Kral MC, Boan AD. Not all generic Concerta is created equal: comparison of OROS versus non-OROS for the treatment of ADHD [published online October 14, 2015]. Clin Pediatr (Phila). doi:10.1177/0009922815611647.

4. Italiano DD, Bruno A, Santoro V, et al. Generic olanzapine substitution in patients with schizophrenia: assessment of serum concentrations and therapeutic response after switching. Ther Drug Monit. 2015;37(6):827-830.

5. Borgheini GG. The bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of generic versus brand-name psychoactive drugs. Clin Ther. 2003;25(6):1578-1592.

6. Thomas K. F.D.A. delays rule on generic drug labels. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/20/business/fda-delays-rule-on-generic-drug-labels.html. Published May 19, 2016. Accessed August 29, 2016.

7. Pae CU, Misra A, Ham BJ, et al. Paroxetine mesylate: comparable to paroxetine hydrochloride? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11(2):185-193

CASE

Sudden deterioration

R, age 11, has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), combined type, and oppositional defiant disorder, which has been stable for more than a year on extended-release (ER) methylphenidate (brand name: Concerta), 54 mg/d (1.2 mg/kg). With combined pharmacotherapy and behavioral management, his symptoms of hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity improved at school and at home. He shows some academic gains as evidenced by improved achievement at school.

Over 2 months, R experiences a substantial deterioration in behavioral and academic performance. Along with core symptoms of ADHD, he begins to exhibit physical and verbal aggression. A report from school states that R has been using obscene language and destroying property, and has had episodes of provoked aggression toward his peers. His grades drop and he receives 2 school suspensions because of aggressive behavior.

What could be causing R’s ADHD symptoms to reemerge?

a) nonadherence to treatment

b) substance abuse

c) medication change

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

Worsening of psychiatric symptoms in a stable patient is relatively common. Many factors can contribute to patient destabilization. Treatment nonadherence is a leading cause, along with psychosocial stressors and substance use (Table).

EVALUATION

Adherence confirmed

R is hyperactive and distracted during his visit, a clear deterioration from his baseline status. R is oppositional and defiant toward his mother during the session, but shows good social skills when communicating with the physician.

R’s mother reports that her son seldom forgets to take his medication, and she ensures that he is swallowing the pill, rather than chewing it. Data from the prescription drug-monitoring program show that the family is filling the prescriptions regularly. The ER methylphenidate dosage is raised to 72 mg/d. The clinicians provide psychoeducation about adherence to a medication regimen to R and his family. Also, his parents and teachers receive Vanderbilt Assessment Scales for ADHD to assess the symptoms in different settings.

At a follow-up visit a week later, R’s mother reports that her son continues to have problems in school and at home. The Vanderbilt scales reveal that R is having clinically significant problems with attention, hyperactivity, impulse control, and oppositional behavior.

A urine drug screen is ordered to rule out the possibility of a sudden deterioration of ADHD symptoms secondary to substance use disorder. To ensure compliance, we recommend that R take his medication at the school nurse’s office in the morning.

A week later

Although R takes his medication at school, he continues to show core symptoms of ADHD without improvement. The urine drug screen is negative. A physical examination does not reveal any medical illness. The treatment team calls the pharmacist to obtain a complete list of medications R is taking, who confirms that he is only receiving ER methylphenidate, 72 mg/d. The pharmacist also notes that R’s medication was switched from the brand-name drug to a generic 3 months ago because of a change in insurance coverage. This change coincided with the reemergence of his ADHD symptoms.

R’s mother reports that the new pills do not look like the old ones even before the dosage was raised. A new brand-necessary prescription is sent to the pharmacy. With the brand-name medication, R’s symptoms quickly improve, and remain improved when the dosage is decreased to the previous dosage of 54 mg/d.

With osmotic-controlled release oral delivery system (OROS) and outer coating of ER methylphenidate, how much drug is released immediately vs slow release?

a) 22% immediate release and 78% slow release

b) 78% immediate release and 22% slow release

c) 50% immediate release and 50% slow release

The authors’ observations

Generic substitution of a brand medication can result in worsening of symptoms and increased adverse effects. Possible bioequivalence issues can lead to failure of drug therapy.1

In 2013, the FDA determined that 2 specific generic formulations of ER methylphenidate do not have therapeutic equivalency to the brand-name medication, Concerta. The FDA stated, “Based on an analysis of data, FDA has concerns about whether or not two approved generic versions of Concerta tablets (methylphenidate hydrochloride extended-release tablets), used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults and children, are therapeutically equiv

In an apparent confirmation of the FDA’s concerns, a case series of children and adolescents with ADHD observed that almost all of the patients showed symptom improvement when they switched from a non-OROS formulation to an OROS preparation at the same dosage.3

The OROS preparation is thought to provide more predictable medication delivery over an extended period of time (Figure). A patient taking an ER formulation without OROS might lose this benefit, which could lead to symptom destabilization, even if the patient is taking the medication as instructed.

Brand vs generic

Under FDA regulations, companies seeking approval for generic formulations of approved drugs must demonstrate that their products are the same as the brand-name drug in terms of:

- active ingredients

- strength

- dosage form

- route of administration

- packaging label.

In addition, the pharmaceutical company must demonstrate that the generic form is absorbed and distributed to the part of the body at which it has its effect at acceptably similar levels to the brand-name drug. All medications—new or generic, in clinical trials or approved, prescription or over-the-counter—must be manufactured under controlled conditions that assure product quality.

However, some studies have disputed this equivalency. In 1 study, patients with schizophrenia receiving generic olanzapine had lower serum concentration than patients with schizophrenia taking equivalent dosages of brand-name olanzapine.4 Similarly, studies comparing generic and brand-name venlafaxine showed significant differences in peak plasma concentration (Cmax)between generic and brand-name compounds.5

The FDA has considered upgrading the manufacturers’ warnings about the risk of generic medications, but has delayed the decision to 2017.6

FDA’s approval process for generic drugs

To receive approval of a generic formulation in the United States, the FDA requires that the generic drug should be compared with the corresponding brand-name drug in small crossover trials involving at least 24 to 36 healthy volunteers.

Bioequivalence is then established based on assessments of the rate of absorption (Cmax and area under the plasma concentration-time curve [AUC]). The FDA’s criteria are designed to achieve 90% confidence that the ratios of the test-to-reference log-transformed mean values for AUC and Cmax are within the interval of 80% to 125%. The FDA accepts −20% to 25% variation in Cmax and AUC in products that are considered bioequivalent. This is much less stringent than its −5% to 5% standard used for brand-name products. The FDA publishes a list of generic drugs that have been certified as bioequivalent, known as the “Orange Book.”5

Considerations when substituting generic medication

Because of the growing number of generic formulations of the same medication, generic–generic switches are becoming more commonplace. Theoretically, any 2 generic versions of the same medication can have a variation of up to 40% in AUC and Cmax. Generic medications are tested in healthy human controls through single-dose studies, which raises concerns about their applicability to the entire patient population.

Bioequivalence. It is a matter of debate whether bioequivalence translates to therapeutic equivalency. For medications with a narrow therapeutic index, the FDA has accepted that these 2 phenomena are not necessarily linked. With the exception of a few medications, including lithium and some anticonvulsants such as divalproex sodium and carbamazepine, serum level of the medications usually does not predict clinical response.

Inert ingredients. Generic medications can include inert ingredients (excipients) that are different from those in their branded counterparts. Some of these inactive ingredients can cause adverse effects. A study comparing paroxetine mesylate and paroxetine hydrochloride showed differences in bioequivalence and clinical efficacy.7

In some cases, brand-to-generic substitution can thwart clinical progress in a stable patient. This small change in the medication could destabilize the patient’s condition, which, in turn, may lead to unnecessary and significant social and financial burdens on the patient’s family, school, community, and the health care system.

Recommendations

In the event of a change in clinical response, clinicians first should evaluate adherence and explore other factors, such as biological, psychological, medical, and social issues. Adherence can be adversely affected by a change in the physical characteristics of the pill. Prescribers should remain cognizant of brand–generic and generic–generic switches. It may be reasonable to adjust the dosage of the new generic medication to address changes in clinical effectiveness.

If these strategies are ineffective, consider switching to a brand-name medication. Write “Dispense As Written” on the prescription to ensure delivery of the branded medication or a specific generic version of the medication.

An insurance company might require prior authorization to approve payment for the brand medication. To save time, use electronic forms or fax for communicating with the insurance company. Adding references to FDA statements and research papers, along with the patient’s history and presentations, would be prudent to demonstrate doubts about efficacy of the generic medication.

CASE

Sudden deterioration

R, age 11, has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), combined type, and oppositional defiant disorder, which has been stable for more than a year on extended-release (ER) methylphenidate (brand name: Concerta), 54 mg/d (1.2 mg/kg). With combined pharmacotherapy and behavioral management, his symptoms of hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity improved at school and at home. He shows some academic gains as evidenced by improved achievement at school.

Over 2 months, R experiences a substantial deterioration in behavioral and academic performance. Along with core symptoms of ADHD, he begins to exhibit physical and verbal aggression. A report from school states that R has been using obscene language and destroying property, and has had episodes of provoked aggression toward his peers. His grades drop and he receives 2 school suspensions because of aggressive behavior.

What could be causing R’s ADHD symptoms to reemerge?

a) nonadherence to treatment

b) substance abuse

c) medication change

d) all of the above

The authors’ observations

Worsening of psychiatric symptoms in a stable patient is relatively common. Many factors can contribute to patient destabilization. Treatment nonadherence is a leading cause, along with psychosocial stressors and substance use (Table).

EVALUATION

Adherence confirmed

R is hyperactive and distracted during his visit, a clear deterioration from his baseline status. R is oppositional and defiant toward his mother during the session, but shows good social skills when communicating with the physician.

R’s mother reports that her son seldom forgets to take his medication, and she ensures that he is swallowing the pill, rather than chewing it. Data from the prescription drug-monitoring program show that the family is filling the prescriptions regularly. The ER methylphenidate dosage is raised to 72 mg/d. The clinicians provide psychoeducation about adherence to a medication regimen to R and his family. Also, his parents and teachers receive Vanderbilt Assessment Scales for ADHD to assess the symptoms in different settings.

At a follow-up visit a week later, R’s mother reports that her son continues to have problems in school and at home. The Vanderbilt scales reveal that R is having clinically significant problems with attention, hyperactivity, impulse control, and oppositional behavior.

A urine drug screen is ordered to rule out the possibility of a sudden deterioration of ADHD symptoms secondary to substance use disorder. To ensure compliance, we recommend that R take his medication at the school nurse’s office in the morning.

A week later

Although R takes his medication at school, he continues to show core symptoms of ADHD without improvement. The urine drug screen is negative. A physical examination does not reveal any medical illness. The treatment team calls the pharmacist to obtain a complete list of medications R is taking, who confirms that he is only receiving ER methylphenidate, 72 mg/d. The pharmacist also notes that R’s medication was switched from the brand-name drug to a generic 3 months ago because of a change in insurance coverage. This change coincided with the reemergence of his ADHD symptoms.

R’s mother reports that the new pills do not look like the old ones even before the dosage was raised. A new brand-necessary prescription is sent to the pharmacy. With the brand-name medication, R’s symptoms quickly improve, and remain improved when the dosage is decreased to the previous dosage of 54 mg/d.

With osmotic-controlled release oral delivery system (OROS) and outer coating of ER methylphenidate, how much drug is released immediately vs slow release?

a) 22% immediate release and 78% slow release

b) 78% immediate release and 22% slow release

c) 50% immediate release and 50% slow release

The authors’ observations

Generic substitution of a brand medication can result in worsening of symptoms and increased adverse effects. Possible bioequivalence issues can lead to failure of drug therapy.1

In 2013, the FDA determined that 2 specific generic formulations of ER methylphenidate do not have therapeutic equivalency to the brand-name medication, Concerta. The FDA stated, “Based on an analysis of data, FDA has concerns about whether or not two approved generic versions of Concerta tablets (methylphenidate hydrochloride extended-release tablets), used to treat attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults and children, are therapeutically equiv

In an apparent confirmation of the FDA’s concerns, a case series of children and adolescents with ADHD observed that almost all of the patients showed symptom improvement when they switched from a non-OROS formulation to an OROS preparation at the same dosage.3

The OROS preparation is thought to provide more predictable medication delivery over an extended period of time (Figure). A patient taking an ER formulation without OROS might lose this benefit, which could lead to symptom destabilization, even if the patient is taking the medication as instructed.

Brand vs generic

Under FDA regulations, companies seeking approval for generic formulations of approved drugs must demonstrate that their products are the same as the brand-name drug in terms of:

- active ingredients

- strength

- dosage form

- route of administration

- packaging label.