User login

Lupus Erythematosus and Localized Scleroderma Coexistent at the Same Sites: A Rare Presentation of Overlap Syndrome of Connective-Tissue Diseases

Although lupus erythematosus (LE) and scleroderma are regarded as 2 distinct entities, there have been multiple cases described in the literature showing an overlap between these 2 disease processes. We report the case of a 60-year-old man with clinical and histopathologic findings consistent with the presence of localized scleroderma and discoid LE (DLE) within the same lesions. We also present a review of the literature and delineate the general patterns of coexistence of these 2 diseases based on our case and other reported cases.

Case Report

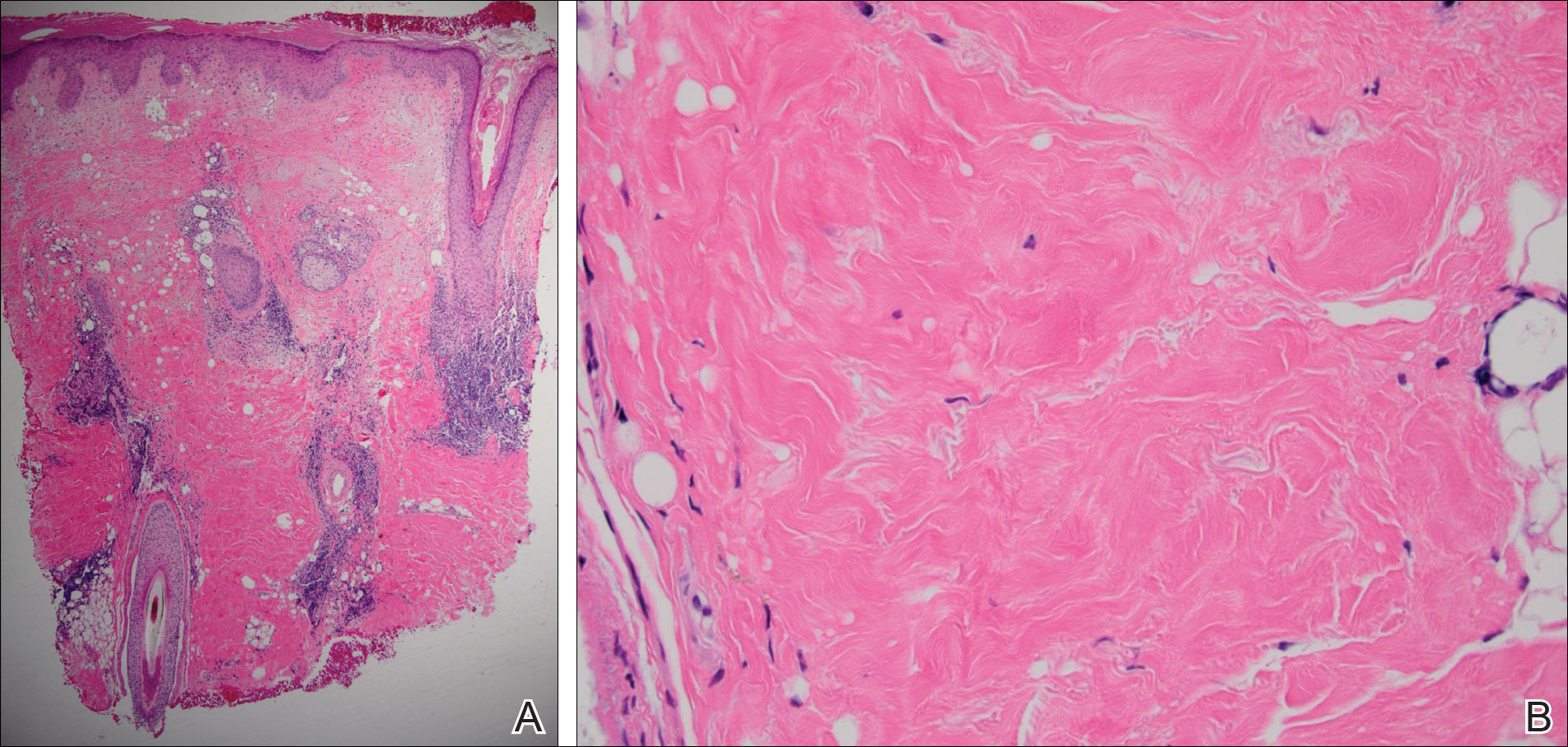

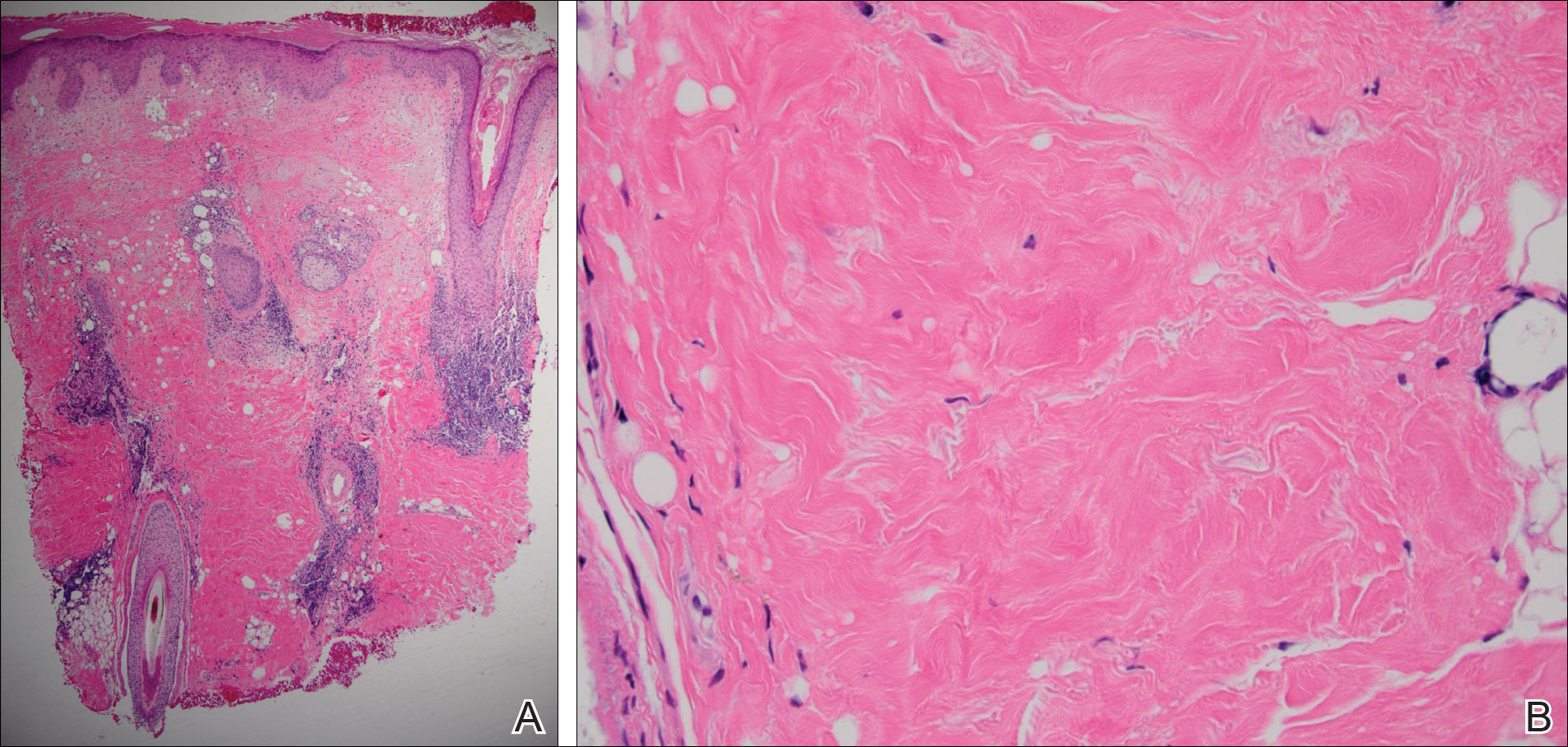

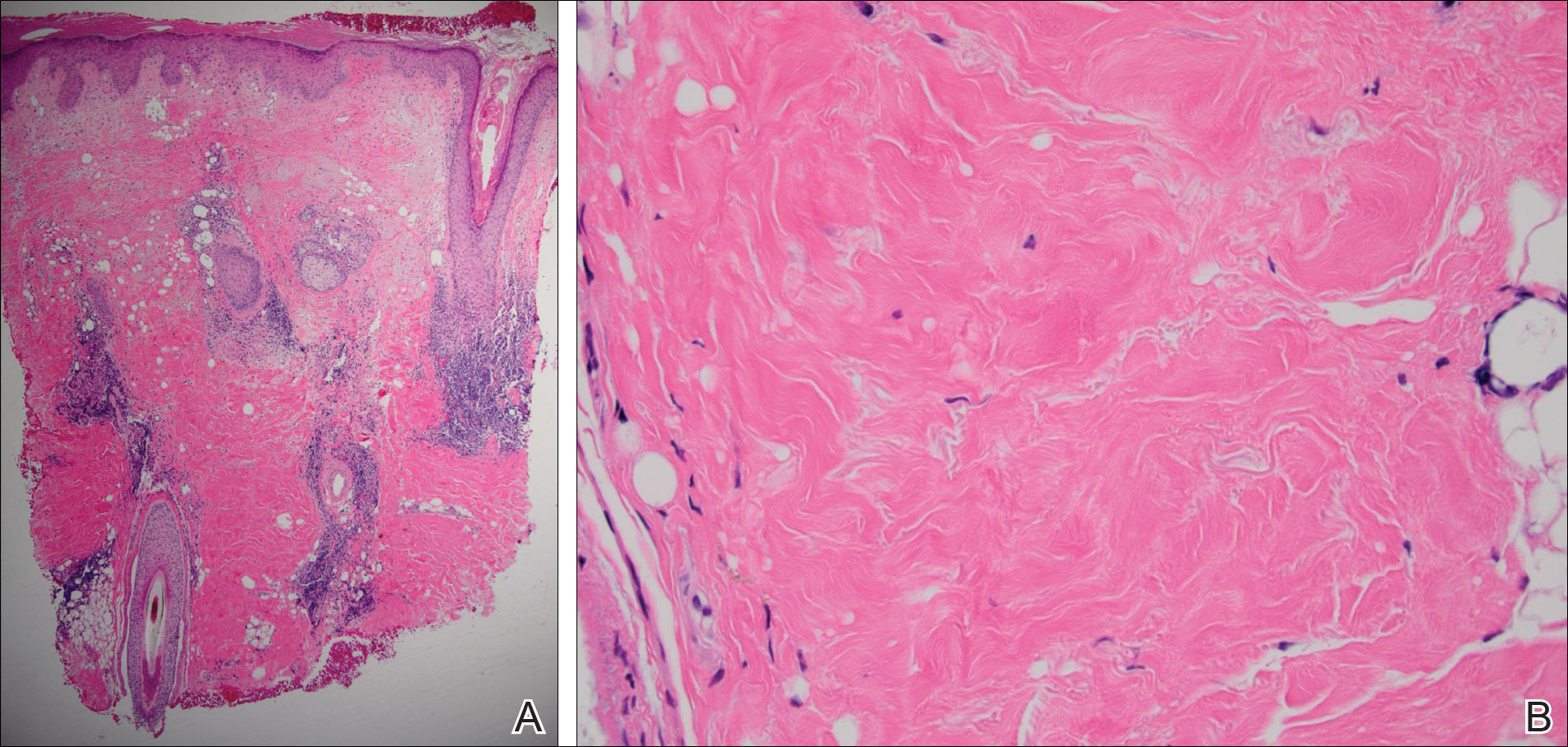

A 60-year-old man presented with a progressive pruritic rash on the face, neck, and upper back of approximately 20 to 30 years’ duration. On initial evaluation, the patient was found to have indurated hypopigmented plaques with follicular plugging bilaterally on the cheeks, temples, ears, and upper back (Figure 1). Punch biopsies were performed on the left cheek and upper back. Histopathology was notable for vacuolar interface dermatitis with dermal sclerosis at both sites. Specifically, interface changes, basement membrane thickening, and periadnexal inflammation were present on histopathologic examination from both biopsies supporting a diagnosis of DLE (Figure 2A). However, there also was sclerosis present in the reticular dermis, suggesting a diagnosis of localized scleroderma (Figure 2B). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for a lupus band. Laboratory workup was positive for antinuclear antibody (titer, 1:40; speckled pattern) and anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A but negative for double-stranded DNA antibody, anti-Smith antibody, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen B, and Scl-70.

The patient was started on oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily and clobetasol oint-ment 0.05% twice daily to affected areas. After 2 weeks of treatment, he developed urticaria on the trunk and the hydroxychloroquine was discontinued. He continued using only topical steroids following a regimen of applying clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 2 weeks, alternating with the use of triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily for 2 weeks with improvement of the pruritus, but the induration and hypopigmentation remained unchanged. Alternative systemic medication was started with mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily. The patient showed remarkable clinical improvement with a decrease in induration and partial resolution of follicular plugging after 4 months of treatment with mycophenolate mofetil in combination with the topical steroid regimen.

Comment

Autoimmune connective-tissue diseases (CTDs) often occur with a wide range of symptoms and signs. Most often patients affected by these diseases can be sorted into one of the named CTDs such as LE, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, polymyositis/dermatomyositis, and Sjögren syndrome. On the other hand, it is widely recognized that patients with one classic autoimmune CTD are likely to possess multiple autoantibodies, and a small number of these patients develop symptoms and/or signs that satisfy the diagnostic criteria of a second autoimmune CTD; these latter patients are said to have an overlap syndrome.1 The development of a second identifiable CTD, hence indicating an overlap syndrome, may occur coincident to the initial CTD or may occur at a different time.1

Essentially all 5 of the CTDs mentioned above have been reported to occur in combination with one another. Most of the reports involving overlap among these 5 CTDs include patients with multiorgan systemic involvement without cutaneous involvement, leading to a fairly simple straightforward classification of overlap syndromes as viewed by rheumatologists.1

When the overlap occurs between the localized forms of scleroderma and purely cutaneous LE, the situation becomes even more complicated, as the skin lesions of the 2 diseases may occur at separate locations or coexistent disease may develop in the same location, as in our case.

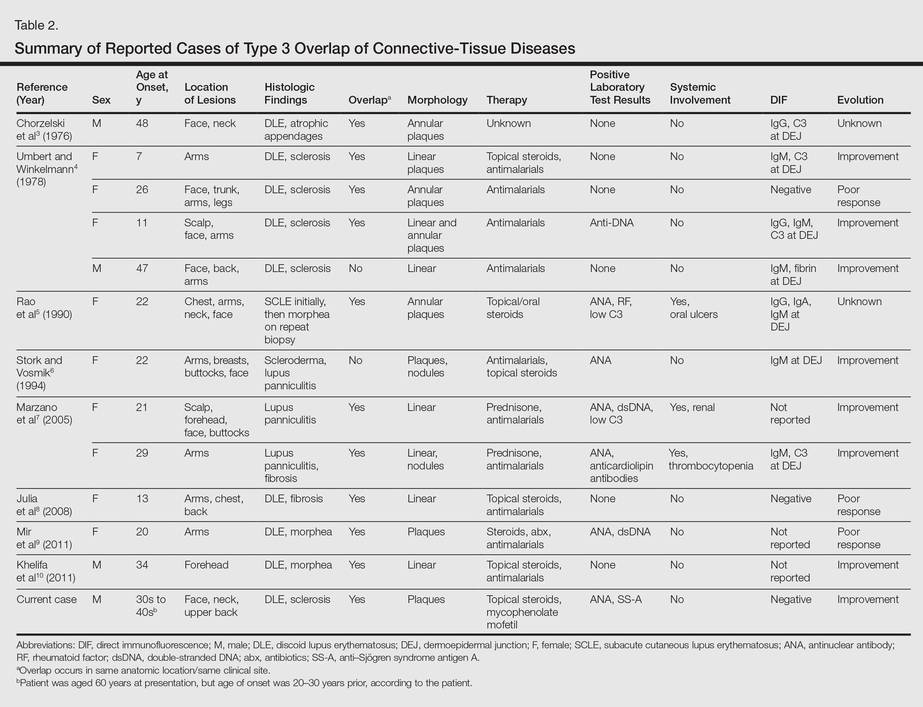

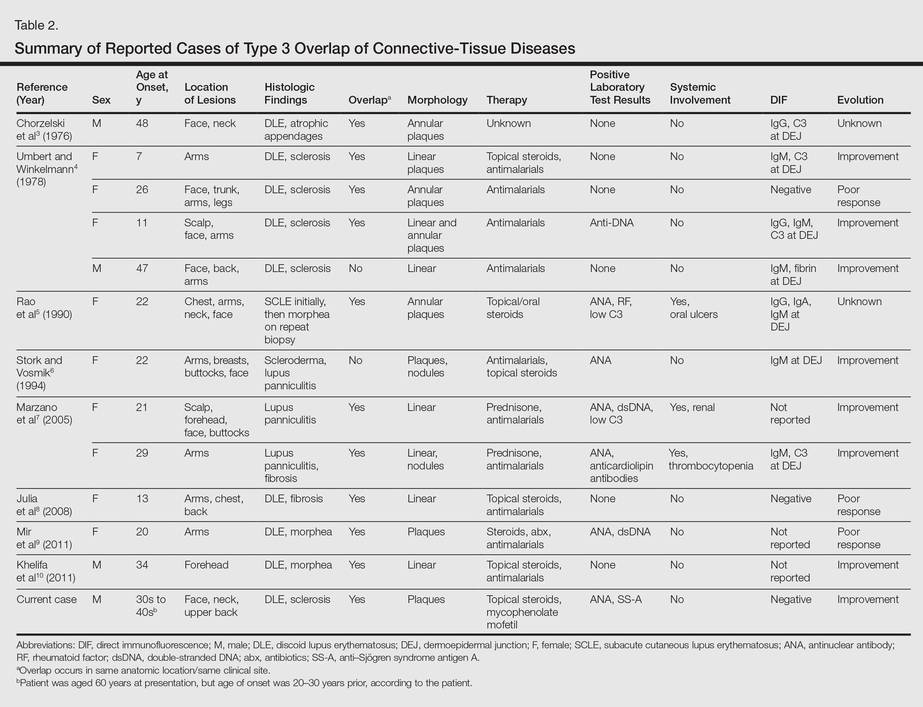

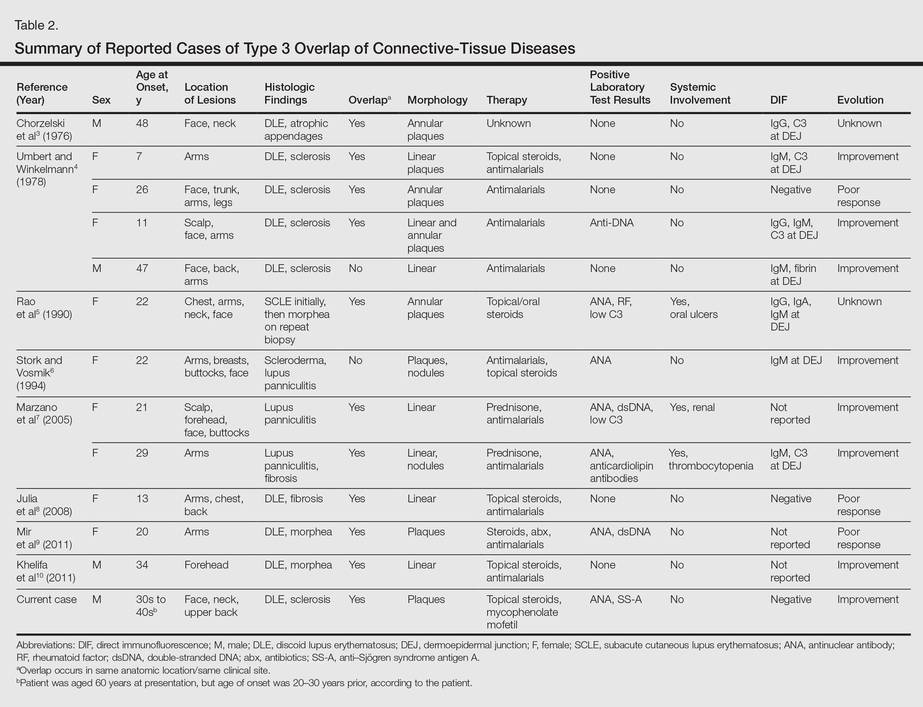

More than 100 cases have been reported wherein LE and scleroderma coexist in the same patient.1 Most of these cases have been examples of type 1 overlap (Table 1), though a few have been type 2 overlap, with localized scleroderma coexisting with systemic LE or vice versa.1,2 There are rare reports of an overlap of the localized form of both of these entities (type 3 overlap), as demonstrated in our patient. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms localized scleroderma and morphea as well as discoid lupus erythematosus, we found 12 other cases describing type 3 overlap (Table 2).

The first case was described in 1976 as annular atrophic plaques on the face and neck of a 48-year-old man.3 As in our case, there were overlapping features of DLE and localized scleroderma. The investigators postulated that the entity was an atypical form of DLE.3 There were 4 more cases described in 1978, but the majority of these patients were young women with linear plaques. Instead of calling the disease a new form of DLE, the investigators considered it to be an overlap syndrome.4 Many years passed before another similar case was described in the literature in 1990.5 Interestingly, the investigators performed multiple biopsies on this patient over several years and observed that the pathology changed from subacute cutaneous LE to an overlap of subacute cutaneous LE and localized scleroderma to localized scleroderma, suggesting that localized scleroderma was the end result of persistent inflammation from the cutaneous LE lesions. The investigators compared the evolution of subacute cutaneous LE to localized scleroderma in the patient to the evolution of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) to chronic GVHD. Acute GVHD has a lichenoid tissue reaction that develops into sclerosis in the chronic form.5

Additionally, there were 3 cases in the literature showing an overlap of lupus panniculitis with localized scleroderma.6,7 Stork and Vosmik6 described a case of a 22-year-old woman with lesions clinically suspicious for localized scleroderma, with lupus panniculitis demonstrated on histopathology. They discussed the difficulty in differentiating between lupus panniculitis and localized scleroderma but did not specify whether they believed the case represented a distinct entity or an overlap syndrome.6 Alternatively, Marzano et al7 reported 2 similar cases, which the investigators considered to be a specific new variant called sclerodermic linear lupus panniculitis.

In the last 10 years, there were 3 additional cases reported that described an overlap of DLE and localized scleroderma in the same anatomic location, similar to our patient.8-10 Although Julia et al8 considered their case to be an example of the distinct entity called sclerodermiform linear LE, the investigators in the other 2 cases described the possibility of an overlap syndrome.9,10

Based on reported cases, we found the following patterns in the overlap of cutaneous LE and localized scleroderma: predilection for young women, photodistributed lesions, DLE, linear morphology clinically, and positivity along the dermoepidermal junction on direct immunofluorescence. As in our case, the few affected men were older compared to affected women. Men ranged in age from 34 to 48 years compared to women who ranged in age from 7 to 29 years. We did not find a pattern in the laboratory findings in these patients. Most patients had a good response to antimalarials, topical steroids, or systemic steroids.

Conclusion

All 12 previously reported cases showed some form of overlap of cutaneous LE and localized scleroderma. As previously discussed, overlap syndromes are common in patients with CTDs. We postulate that our case represents a rare form of overlap syndrome, with the overlap occurring at the same clinical sites.

- Iaccarino L, Gatto M, Bettio S, et al. Overlap connective tissue disease syndromes [published online June 26, 2012]. Autoimmun Reviews. 2012;12:363-373.

- Balbir-Gurman A, Braun-Moscovici Y. Scleroderma overlap syndrome. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13:14-20.

- Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszyczyk M, et al. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1143-1145.

- Umbert P, Winkelmann RK. Concurrent localized scleroderma and discoid lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1473-1478.

- Rao BK, Coldiron B, Freeman RG, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus progressing to morphea erythematosus lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(5, pt 2):1019-1022.

- Stork J, Vosmik F. Lupus erythematosus panniculitis with morphea-like lesions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:79-82.

- Marzano AV, Tanzi C, Caputo R, et al. Sclerodermic linear lupus panniculitis: report of two cases. Dermatology. 2005;210:329-332.

- Julia M, Mascaro JM Jr, Guilaber A, et al. Sclerodermiform linear lupus erythematosus: a distinct entity or coexistence of two autoimmune diseases? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:665-667.

- Mir A, Tlougan B, O’Reilly K, et al. Morphea with discoid lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Khelifa E, Masouye I, Pham HC, et al. Linear sclerodermic lupus erythematosus, a distinct variant of linear morphea and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1491-1495.

Although lupus erythematosus (LE) and scleroderma are regarded as 2 distinct entities, there have been multiple cases described in the literature showing an overlap between these 2 disease processes. We report the case of a 60-year-old man with clinical and histopathologic findings consistent with the presence of localized scleroderma and discoid LE (DLE) within the same lesions. We also present a review of the literature and delineate the general patterns of coexistence of these 2 diseases based on our case and other reported cases.

Case Report

A 60-year-old man presented with a progressive pruritic rash on the face, neck, and upper back of approximately 20 to 30 years’ duration. On initial evaluation, the patient was found to have indurated hypopigmented plaques with follicular plugging bilaterally on the cheeks, temples, ears, and upper back (Figure 1). Punch biopsies were performed on the left cheek and upper back. Histopathology was notable for vacuolar interface dermatitis with dermal sclerosis at both sites. Specifically, interface changes, basement membrane thickening, and periadnexal inflammation were present on histopathologic examination from both biopsies supporting a diagnosis of DLE (Figure 2A). However, there also was sclerosis present in the reticular dermis, suggesting a diagnosis of localized scleroderma (Figure 2B). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for a lupus band. Laboratory workup was positive for antinuclear antibody (titer, 1:40; speckled pattern) and anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A but negative for double-stranded DNA antibody, anti-Smith antibody, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen B, and Scl-70.

The patient was started on oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily and clobetasol oint-ment 0.05% twice daily to affected areas. After 2 weeks of treatment, he developed urticaria on the trunk and the hydroxychloroquine was discontinued. He continued using only topical steroids following a regimen of applying clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 2 weeks, alternating with the use of triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily for 2 weeks with improvement of the pruritus, but the induration and hypopigmentation remained unchanged. Alternative systemic medication was started with mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily. The patient showed remarkable clinical improvement with a decrease in induration and partial resolution of follicular plugging after 4 months of treatment with mycophenolate mofetil in combination with the topical steroid regimen.

Comment

Autoimmune connective-tissue diseases (CTDs) often occur with a wide range of symptoms and signs. Most often patients affected by these diseases can be sorted into one of the named CTDs such as LE, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, polymyositis/dermatomyositis, and Sjögren syndrome. On the other hand, it is widely recognized that patients with one classic autoimmune CTD are likely to possess multiple autoantibodies, and a small number of these patients develop symptoms and/or signs that satisfy the diagnostic criteria of a second autoimmune CTD; these latter patients are said to have an overlap syndrome.1 The development of a second identifiable CTD, hence indicating an overlap syndrome, may occur coincident to the initial CTD or may occur at a different time.1

Essentially all 5 of the CTDs mentioned above have been reported to occur in combination with one another. Most of the reports involving overlap among these 5 CTDs include patients with multiorgan systemic involvement without cutaneous involvement, leading to a fairly simple straightforward classification of overlap syndromes as viewed by rheumatologists.1

When the overlap occurs between the localized forms of scleroderma and purely cutaneous LE, the situation becomes even more complicated, as the skin lesions of the 2 diseases may occur at separate locations or coexistent disease may develop in the same location, as in our case.

More than 100 cases have been reported wherein LE and scleroderma coexist in the same patient.1 Most of these cases have been examples of type 1 overlap (Table 1), though a few have been type 2 overlap, with localized scleroderma coexisting with systemic LE or vice versa.1,2 There are rare reports of an overlap of the localized form of both of these entities (type 3 overlap), as demonstrated in our patient. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms localized scleroderma and morphea as well as discoid lupus erythematosus, we found 12 other cases describing type 3 overlap (Table 2).

The first case was described in 1976 as annular atrophic plaques on the face and neck of a 48-year-old man.3 As in our case, there were overlapping features of DLE and localized scleroderma. The investigators postulated that the entity was an atypical form of DLE.3 There were 4 more cases described in 1978, but the majority of these patients were young women with linear plaques. Instead of calling the disease a new form of DLE, the investigators considered it to be an overlap syndrome.4 Many years passed before another similar case was described in the literature in 1990.5 Interestingly, the investigators performed multiple biopsies on this patient over several years and observed that the pathology changed from subacute cutaneous LE to an overlap of subacute cutaneous LE and localized scleroderma to localized scleroderma, suggesting that localized scleroderma was the end result of persistent inflammation from the cutaneous LE lesions. The investigators compared the evolution of subacute cutaneous LE to localized scleroderma in the patient to the evolution of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) to chronic GVHD. Acute GVHD has a lichenoid tissue reaction that develops into sclerosis in the chronic form.5

Additionally, there were 3 cases in the literature showing an overlap of lupus panniculitis with localized scleroderma.6,7 Stork and Vosmik6 described a case of a 22-year-old woman with lesions clinically suspicious for localized scleroderma, with lupus panniculitis demonstrated on histopathology. They discussed the difficulty in differentiating between lupus panniculitis and localized scleroderma but did not specify whether they believed the case represented a distinct entity or an overlap syndrome.6 Alternatively, Marzano et al7 reported 2 similar cases, which the investigators considered to be a specific new variant called sclerodermic linear lupus panniculitis.

In the last 10 years, there were 3 additional cases reported that described an overlap of DLE and localized scleroderma in the same anatomic location, similar to our patient.8-10 Although Julia et al8 considered their case to be an example of the distinct entity called sclerodermiform linear LE, the investigators in the other 2 cases described the possibility of an overlap syndrome.9,10

Based on reported cases, we found the following patterns in the overlap of cutaneous LE and localized scleroderma: predilection for young women, photodistributed lesions, DLE, linear morphology clinically, and positivity along the dermoepidermal junction on direct immunofluorescence. As in our case, the few affected men were older compared to affected women. Men ranged in age from 34 to 48 years compared to women who ranged in age from 7 to 29 years. We did not find a pattern in the laboratory findings in these patients. Most patients had a good response to antimalarials, topical steroids, or systemic steroids.

Conclusion

All 12 previously reported cases showed some form of overlap of cutaneous LE and localized scleroderma. As previously discussed, overlap syndromes are common in patients with CTDs. We postulate that our case represents a rare form of overlap syndrome, with the overlap occurring at the same clinical sites.

Although lupus erythematosus (LE) and scleroderma are regarded as 2 distinct entities, there have been multiple cases described in the literature showing an overlap between these 2 disease processes. We report the case of a 60-year-old man with clinical and histopathologic findings consistent with the presence of localized scleroderma and discoid LE (DLE) within the same lesions. We also present a review of the literature and delineate the general patterns of coexistence of these 2 diseases based on our case and other reported cases.

Case Report

A 60-year-old man presented with a progressive pruritic rash on the face, neck, and upper back of approximately 20 to 30 years’ duration. On initial evaluation, the patient was found to have indurated hypopigmented plaques with follicular plugging bilaterally on the cheeks, temples, ears, and upper back (Figure 1). Punch biopsies were performed on the left cheek and upper back. Histopathology was notable for vacuolar interface dermatitis with dermal sclerosis at both sites. Specifically, interface changes, basement membrane thickening, and periadnexal inflammation were present on histopathologic examination from both biopsies supporting a diagnosis of DLE (Figure 2A). However, there also was sclerosis present in the reticular dermis, suggesting a diagnosis of localized scleroderma (Figure 2B). Direct immunofluorescence was negative for a lupus band. Laboratory workup was positive for antinuclear antibody (titer, 1:40; speckled pattern) and anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen A but negative for double-stranded DNA antibody, anti-Smith antibody, anti–Sjögren syndrome antigen B, and Scl-70.

The patient was started on oral hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily and clobetasol oint-ment 0.05% twice daily to affected areas. After 2 weeks of treatment, he developed urticaria on the trunk and the hydroxychloroquine was discontinued. He continued using only topical steroids following a regimen of applying clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 2 weeks, alternating with the use of triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily for 2 weeks with improvement of the pruritus, but the induration and hypopigmentation remained unchanged. Alternative systemic medication was started with mycophenolate mofetil 1 g twice daily. The patient showed remarkable clinical improvement with a decrease in induration and partial resolution of follicular plugging after 4 months of treatment with mycophenolate mofetil in combination with the topical steroid regimen.

Comment

Autoimmune connective-tissue diseases (CTDs) often occur with a wide range of symptoms and signs. Most often patients affected by these diseases can be sorted into one of the named CTDs such as LE, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, polymyositis/dermatomyositis, and Sjögren syndrome. On the other hand, it is widely recognized that patients with one classic autoimmune CTD are likely to possess multiple autoantibodies, and a small number of these patients develop symptoms and/or signs that satisfy the diagnostic criteria of a second autoimmune CTD; these latter patients are said to have an overlap syndrome.1 The development of a second identifiable CTD, hence indicating an overlap syndrome, may occur coincident to the initial CTD or may occur at a different time.1

Essentially all 5 of the CTDs mentioned above have been reported to occur in combination with one another. Most of the reports involving overlap among these 5 CTDs include patients with multiorgan systemic involvement without cutaneous involvement, leading to a fairly simple straightforward classification of overlap syndromes as viewed by rheumatologists.1

When the overlap occurs between the localized forms of scleroderma and purely cutaneous LE, the situation becomes even more complicated, as the skin lesions of the 2 diseases may occur at separate locations or coexistent disease may develop in the same location, as in our case.

More than 100 cases have been reported wherein LE and scleroderma coexist in the same patient.1 Most of these cases have been examples of type 1 overlap (Table 1), though a few have been type 2 overlap, with localized scleroderma coexisting with systemic LE or vice versa.1,2 There are rare reports of an overlap of the localized form of both of these entities (type 3 overlap), as demonstrated in our patient. According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms localized scleroderma and morphea as well as discoid lupus erythematosus, we found 12 other cases describing type 3 overlap (Table 2).

The first case was described in 1976 as annular atrophic plaques on the face and neck of a 48-year-old man.3 As in our case, there were overlapping features of DLE and localized scleroderma. The investigators postulated that the entity was an atypical form of DLE.3 There were 4 more cases described in 1978, but the majority of these patients were young women with linear plaques. Instead of calling the disease a new form of DLE, the investigators considered it to be an overlap syndrome.4 Many years passed before another similar case was described in the literature in 1990.5 Interestingly, the investigators performed multiple biopsies on this patient over several years and observed that the pathology changed from subacute cutaneous LE to an overlap of subacute cutaneous LE and localized scleroderma to localized scleroderma, suggesting that localized scleroderma was the end result of persistent inflammation from the cutaneous LE lesions. The investigators compared the evolution of subacute cutaneous LE to localized scleroderma in the patient to the evolution of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) to chronic GVHD. Acute GVHD has a lichenoid tissue reaction that develops into sclerosis in the chronic form.5

Additionally, there were 3 cases in the literature showing an overlap of lupus panniculitis with localized scleroderma.6,7 Stork and Vosmik6 described a case of a 22-year-old woman with lesions clinically suspicious for localized scleroderma, with lupus panniculitis demonstrated on histopathology. They discussed the difficulty in differentiating between lupus panniculitis and localized scleroderma but did not specify whether they believed the case represented a distinct entity or an overlap syndrome.6 Alternatively, Marzano et al7 reported 2 similar cases, which the investigators considered to be a specific new variant called sclerodermic linear lupus panniculitis.

In the last 10 years, there were 3 additional cases reported that described an overlap of DLE and localized scleroderma in the same anatomic location, similar to our patient.8-10 Although Julia et al8 considered their case to be an example of the distinct entity called sclerodermiform linear LE, the investigators in the other 2 cases described the possibility of an overlap syndrome.9,10

Based on reported cases, we found the following patterns in the overlap of cutaneous LE and localized scleroderma: predilection for young women, photodistributed lesions, DLE, linear morphology clinically, and positivity along the dermoepidermal junction on direct immunofluorescence. As in our case, the few affected men were older compared to affected women. Men ranged in age from 34 to 48 years compared to women who ranged in age from 7 to 29 years. We did not find a pattern in the laboratory findings in these patients. Most patients had a good response to antimalarials, topical steroids, or systemic steroids.

Conclusion

All 12 previously reported cases showed some form of overlap of cutaneous LE and localized scleroderma. As previously discussed, overlap syndromes are common in patients with CTDs. We postulate that our case represents a rare form of overlap syndrome, with the overlap occurring at the same clinical sites.

- Iaccarino L, Gatto M, Bettio S, et al. Overlap connective tissue disease syndromes [published online June 26, 2012]. Autoimmun Reviews. 2012;12:363-373.

- Balbir-Gurman A, Braun-Moscovici Y. Scleroderma overlap syndrome. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13:14-20.

- Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszyczyk M, et al. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1143-1145.

- Umbert P, Winkelmann RK. Concurrent localized scleroderma and discoid lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1473-1478.

- Rao BK, Coldiron B, Freeman RG, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus progressing to morphea erythematosus lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(5, pt 2):1019-1022.

- Stork J, Vosmik F. Lupus erythematosus panniculitis with morphea-like lesions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:79-82.

- Marzano AV, Tanzi C, Caputo R, et al. Sclerodermic linear lupus panniculitis: report of two cases. Dermatology. 2005;210:329-332.

- Julia M, Mascaro JM Jr, Guilaber A, et al. Sclerodermiform linear lupus erythematosus: a distinct entity or coexistence of two autoimmune diseases? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:665-667.

- Mir A, Tlougan B, O’Reilly K, et al. Morphea with discoid lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Khelifa E, Masouye I, Pham HC, et al. Linear sclerodermic lupus erythematosus, a distinct variant of linear morphea and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1491-1495.

- Iaccarino L, Gatto M, Bettio S, et al. Overlap connective tissue disease syndromes [published online June 26, 2012]. Autoimmun Reviews. 2012;12:363-373.

- Balbir-Gurman A, Braun-Moscovici Y. Scleroderma overlap syndrome. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13:14-20.

- Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S, Blaszyczyk M, et al. Annular atrophic plaques of the face. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:1143-1145.

- Umbert P, Winkelmann RK. Concurrent localized scleroderma and discoid lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1473-1478.

- Rao BK, Coldiron B, Freeman RG, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus progressing to morphea erythematosus lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(5, pt 2):1019-1022.

- Stork J, Vosmik F. Lupus erythematosus panniculitis with morphea-like lesions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:79-82.

- Marzano AV, Tanzi C, Caputo R, et al. Sclerodermic linear lupus panniculitis: report of two cases. Dermatology. 2005;210:329-332.

- Julia M, Mascaro JM Jr, Guilaber A, et al. Sclerodermiform linear lupus erythematosus: a distinct entity or coexistence of two autoimmune diseases? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:665-667.

- Mir A, Tlougan B, O’Reilly K, et al. Morphea with discoid lupus erythematosus. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:10.

- Khelifa E, Masouye I, Pham HC, et al. Linear sclerodermic lupus erythematosus, a distinct variant of linear morphea and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:1491-1495.

Practice Points

- Discoid lupus erythematosus and localized scleroderma may rarely overlap within the same lesions.

- Cutaneous overlap syndromes tend to respond well to antimalarials, topical steroids, and systemic steroids.

The Great Mimickers of Rosacea

Although rosacea is one of the most common conditions treated by dermatologists, it also is one of the most misunderstood. Historically, large noses due to rhinomegaly were associated with indulgence in wine and wealth.1 The term rosacea is derived from the Latin adjective meaning “like roses.” Rosacea was first medically described in French as goutterose (pink droplet) and pustule de vin (pimples of wine).1 This article reviews the characteristics of rosacea compared to several mimickers of rosacea that physicians should consider.

Rosacea Characteristics

Rosacea is a chronic disorder affecting the central parts of the face that is characterized by frequent flushing; persistent erythema (ie, lasting for at least 3 months); telangiectasia; and interspersed episodes of inflammation with swelling, papules, and pustules.2 It is most commonly seen in adults older than 30 years and is considered to have a strong hereditary component, as it is more commonly seen in individuals of Celtic and Northern European descent as well as those with fair skin. Furthermore, approximately 30% to 40% of patients report a family member with the condition.2

Rosacea Subtypes

In a 2002 meeting held to standardize the diagnostic criteria for rosacea, the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea described 4 broad clinical subtypes of rosacea: erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular.3 More than 1 subtype may present in the same patient. A progression from one subtype to another can occur in cases of severe papulopustular or glandular rosacea that eventuate into the phymatous form.2 Moreover, not all of the disease features are present in every patient. Secondary features of rosacea include burning or stinging, edema, plaques, dry appearance of the skin, ocular manifestations, peripheral site involvement, and phymatous changes.

In erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, episodic flushing occurs, which can last longer than 10 minutes with the central face exhibiting the most intense color. The redness also may involve the peripheral portion of the face as well as extrafacial areas (eg, ears, scalp, neck, chest). Periocular skin is spared. The stimuli that may bring on flushing include short-term emotional stress, hot drinks, alcohol, spicy foods, exercise, cold or hot weather, and hot water.3

Patients with papulopustular rosacea generally present with redness of the central portion of the face along with persistent or intermittent flares characterized by small papules and pinpoint pustules. There also is an almost universal sparing of the periocular skin, and a history of flushing often is present; however, flushing usually is milder than in the erythematotelangiectatic subtype. The constant inflammation may lead to chronic edema and phymatous changes, which occur more commonly in men than in women.3

Phymatous rosacea is characterized by marked skin thickening and irregular surface nodularities, most commonly involving the nose (rhinophyma), though the chin (gnathophyma), forehead (metophyma), ears (otophyma), and eyelids (blepharophyma) also are occasionally affected. There are 4 variants of rhinophyma with distinct histopathologic features: glandular, fibrous, fibroangiomatous, and actinic.3 The glandular variant is most often seen in men who have thick sebaceous skin. Edematous papules and pustules often are large and may be accompanied by nodulocystic lesions. Frequently, affected patients will have a history of adolescent acne with scarring.

Ocular rosacea may precede cutaneous findings by many years; however, in most cases the ocular findings occur concurrently or develop later on in the disease course. The most consistent findings in ocular rosacea are blepharitis and conjunctivitis. Symptoms of burning or stinging, itching, light sensitivity, and a foreign body sensation are common in these patients.3

Pathogenesis

Several investigators have proposed that Demodex folliculorum may play a pathogenic role in rosacea. Demodex is a common inhabitant of normal human skin, and its role in human disease is a matter of controversy.3Demodex has a predilection for the regions of the skin that are most often affected by rosacea, such as the nose and cheeks. The clinical manifestations of rosacea tend to appear later in life, which parallels the increase in the density of Demodex mites that occurs with age.4 It has been hypothesized that beneficial effects of metronidazole in the treatment of rosacea may be related to an antiparasitic effect on Demodex; however, these mites can survive high concentrations of the drug.3 Moreover, modern techniques that employ cyanoacrylate surface biopsies, which are extremely sensitive, estimate that the prevalence of Demodex in healthy skin approaches 100%.4 Consequently, the simple identification of Demodex is by no means proof of pathogenesis. Whether Demodex is truly pathogenic or simply an inhabitant of follicles in rosacea-prone skin remains a subject for future investigation.

Demodicosis occurs mainly in immunosuppressed patients because immunosuppression influences the number of Demodex mites and the treatment response. Multiple patients with AIDS and/or those with a CD4 lymphocyte count below 200/mm3 have been reported to have demodicosis.5-11 In immunocompetent patients, pruritic papular, papulopustular, and nodular lesions occur on the face, but in immunocompromised patients, the eruption may be more diffuse, affecting the back, presternal area, and upper limbs.6 A correct diagnosis relies on suggestive clinical signs, the presence of numerous parasites on direct examination, and a good clinical response to acaricide treatment.

Helicobacter pylori seropositivity has been associated with various dermatologic disorders, including rosacea.12 However, robust support for a causal association between H pylori and rosacea does not exist. Several studies have demonstrated high prevalence rates of H pylori in rosacea patients, some even in comparison with age- and sex-matched controls.13,14 Moreover, treatments aimed at eradicating H pylori also beneficially influence the clinical outcome of rosacea; for instance, metronidazole, a common treatment of roscea, is an effective agent against H pylori.

Understanding the clinical variants and disease course of rosacea is important to differentiate this entity from other conditions that can mimic rosacea. Laboratory studies and histopathologic examination via skin biopsy may be needed to differentiate between rosacea and rosacealike conditions.

Common Rosacealike Conditions

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory disease that has protean clinical manifestations and follows a relapsing and remitting course. Characteristic malar erythema appears in approximately 50% of patients and may accompany or precede other symptoms of lupus. The affected skin generally feels warm and appears slightly edematous. The erythema may last for hours to days and often recurs, particularly with sun exposure. The malar erythema of SLE can be confused with the redness of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. Nevertheless, the color of the skin in SLE has a violaceous quality and may show a more abrupt cutoff, especially at its most lateral margins. Marzano et al15 reported 4 cases in which lupus erythematosus was misdiagnosed as rosacea. All 4 patients presented with erythema that was localized to the central face along with a few raised, smooth, round, erythematous to violaceous papules over the malar areas and the forehead. This presentation evolved rapidly and was aggravated by sun exposure. The patients were all treated with medication for rosacea but showed no improvement. These patients originally presented with limited skin involvement in the absence of any systemic sign or symptoms of SLE.15

Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an inflammatory myopathy characterized by varying degrees of muscle weakness and distinctive skin erythema (Figure 1); however, some patients lack muscular involvement and initially present with skin manifestations only. Sontheimer16 described criteria for defining skin involvement in DM. Major criteria include the heliotrope rash, Gottron papules, and Gottron sign, while minor criteria include macular violaceous erythema (MVE), periungual telangiectasia of the nail fold, poikiloderma, mechanic’s hands, cutaneous calcinosis, cutaneous ulcers, and pruritus. With the exception of the heliotrope rash, facial erythema has drawn little attention in prior studies of DM-associated skin manifestations. Therefore, Okiyama et al17 performed a retrospective study on the skin manifestations of DM in 33 patients. The investigators observed that MVE in the seborrheic area of the face was most frequent.17 Therefore, it is critical to consider DM in the differential diagnosis of rosacea because the MVE seen in DM might be confused with the erythema seen in rosacea.

|

| Figure 1. Macular violaceous erythema of the face in a patient with dermatomyositis. Photograph courtesy of Marc Silverstein, MD, Sacramento, California. |

|

Figure 2. Polymorphous light eruption manifesting as erythematous papules over the cheek and dorsal aspect of the nose. Photograph courtesy of Marc Silverstein, MD, Sacramento, California. |

Polymorphous Light Eruption

Polymorphous light eruption (PMLE), the most common of the idiopathic photodermatoses, is characterized by erythematous papules, papulovesicles, and plaques on sun-exposed surfaces (Figure 2). The areas of the skin that are most commonly affected are the face, neck, outer aspects of the arms, and dorsal surfaces of the hands.18 Lesions may appear immediately but often develop several hours after sun exposure. Symptoms of itching and/or burning usually are mild and transient. The etiology of PMLE is unknown, though it is likely to be multifactorial.

Similarities between PMLE and rosacea include exacerbation by sun exposure and a higher prevalence in fair-skinned individuals.19 Also, in both conditions erythematous papules appear on the face and may be pruritic and in some instances painful; however, unlike rosacea, which is chronic, PMLE tends to be intermittent and recurrent, typically occurring in the spring and early summer months. In contrast to rosacea, the onset of the erythema in PMLE is abrupt, appearing quickly after sun exposure and subsiding within 1 to 7 days. Furthermore, patients with PMLE may experience systemic flulike symptoms after sun exposure.19

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic relapsing papulosquamous skin disease most commonly involving sebum-rich areas such as the scalp and face. The prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis is higher in human immunodeficiency virus–positive individuals and in patients with neurologic conditions such as Parkinson disease. The pathogenesis of seborrheic dermatitis has been linked to the yeast of Malassezia species, immunologic abnormalities, and activation of complements. A clinical diagnosis usually is made based on a history of waxing and waning in severity and by the sites of involvement.20

Similar to rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic and relapsing erythematous rash with well-demarcated erythematous patches, papules, or plaques; however, unlike rosacea, the distribution varies from minimal asymptomatic scaliness of the scalp to more widespread involvement (eg, scalp, ears, upper aspect of the trunk, intertriginous areas). Also, although macular erythema and scaling involving the perinasal area (Figure 3) may be seen in either rosacea or seborrheic dermatitis, a greasy quality to the scales and involvement of other sites such as the scalp, retroauricular skin, and eyebrows suggest a diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis.

Acne Vulgaris

Acne vulgaris is the most common skin disease in the United States.21 It is characterized by noninflammatory; open or closed comedones; and inflammatory papules, pustules, and nodules. Acne vulgaris typically affects the areas of skin with the highest density of sebaceous follicles including the face, upper aspect of the chest, and back.22 It is the most common skin disease in the differential diagnosis of the papulopustular form of rosacea. Inflammatory lesions in both acne vulgaris and rosacea may be clinically identical; however, unlike acne vulgaris, rosacea is characterized by a complete absence of comedones. A prominent centrofacial distribution also favors rosacea. As a general rule, acne peaks in adolescence, years before papulopustular rosacea usually becomes prominent. However, some acne patients who are prone to flushing and blushing may develop rosacea later in life.

Topical Steroid–Induced Acne

Chronic use of topical corticosteroids on the face for several months can result in the appearance of monomorphic inflammatory papules (Figure 4). Corticosteroids can cause a dry scaly eruption with scattered follicular pustules around the mouth (perioral dermatitis).23 This acneform eruption is indistinguishable from rosacea. However, the monomorphic inflammatory papules generally resolve within 1 to 2 months following discontinuation of the corticosteroid therapy.

Multiple pathways have been proposed as the mechanism for such reactions, including rebound vasodilation and proinflammatory cytokine release by chronic intermittent steroid exposure.24 At first, the vasoconstrictive and anti-inflammatory effects of the steroids result in what seems to be clearance of the primary dermatitis for which the steroids were being used. Unfortunately, persistent use of steroids, particularly high-potency products, leads to epidermal atrophy, degeneration of dermal structures, and destruction of collagen, rendering the skin vulnerable to bacterial, viral, and fungal infections. In the end, the skin has the appearance of bright red rosacea with red scaly papules.

Rare Rosacealike Conditions

Carcinoid Syndrome

Carcinoid syndrome typically develops after hepatic metastasis from a carcinoid tumor when the circulating neuroendocrine mediators produced by the tumor can no longer be adequately cleared. Flushing is characteristic of carcinoid syndrome and usually presents on the face, neck, and upper trunk. Although rare, other types of cutaneous involvement also have been reported.25 Bell et al25 concluded that skin involvement is not uncommon in carcinoid syndrome, as all 25 patients with carcinoid syndrome showed cutaneous involvement in their case series. The investigators observed that chronic flushing eventually may become permanent and evolve into a rosacealike picture.25

Cases of carcinoid syndrome that were misdiagnosed as rosacea have been reported in the literature.26-28 Creamer et al26 reported a case of a 67-year-old woman who initially was diagnosed with rosacea; it took 1 year to finally arrive at the correct diagnosis of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 after developing a malignant carcinoid tumor and a parathyroid tumor.

Cutaneous Lymphoma

B-cell neoplasms with skin involvement can present as primary cutaneous lymphomas or as secondary processes, including specific infiltrates of nodal or extranodal lymphoma or leukemia.29 B-cell lymphomas involving the skin have a distinct clinical appearance, presenting as isolated, grouped, or multiple erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules, usually in an asymmetric distribution (Figure 5). B-cell lymphoproliferative diseases simulating rosacea are extremely rare.29 Nevertheless, B-cell lymphoma mimicking rhinophyma has been documented in the literature.29-35

Barzilai et al29 described 12 patients with B-cell lymphoproliferative neoplasms presenting with facial eruptions that clinically mimicked rosacea or rhinophyma. The clinical presentation included small papules on the nose, cheeks, and around the eyes mimicking granulomatous rosacea, and/or nodules on the nose, cheeks, chin, or forehead simulating phymatous rosacea. Three patients had preexisting erythematotelangiectatic rosacea and 1 had rhinophyma.29

Lupus Miliaris Disseminatus Faciei

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF) is an uncommon chronic inflammatory skin disorder characterized by the appearance of asymptomatic small, red to yellowish brown papules on the face.36 This rare dermatologic disease usually is self-limited with spontaneous resolution of the lesions occurring within months or years; however, residual disfiguring scars may persist and usually are characteristic of LMDF.36,37 The pathogenesis of LMDF is unclear, and controversy remains as to whether it is a distinct cutaneous entity or a variant of granulomatous rosacea.38,39 It usually develops slowly as small, dome-shaped, red to yellowish brown papules in adults, most commonly appearing in men.39 Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei shares several common features with both acne vulgaris and rosacea. For example, the inflammatory lesions of LMDF are located on the central face and usually respond to treatments that typically are used to treat acne vulgaris and rosacea. However, LMDF can be distinguished histologically by more intense granulomatous inflammation and central caseation, occurring in the absence of an apparent infectious origin.36

Tyrosinase Kinase Inhibitor Drug Eruptions

Sorafenib and sunitinib malate are multitargeted kinase inhibitors approved for the treatment of cancers such as renal cell carcinoma.40 A study by Lee et al40 reported that approximately 75% of patients treated with either sorafenib (n=109) or sunitinib (n=119) went on to develop at least one cutaneous reaction. Although hand-foot skin reaction was the most common and serious cutaneous side effect, other dermatologic manifestations, including alopecia, stomatitis, discoloration (hair or face), subungual splinter hemorrhages, facial swelling, facial erythema, and xerosis, were described. Facial changes such as swelling, yellowish discoloration, erythema, and acneform eruptions were described more frequently in patients treated with sunitinib than in those treated with sorafenib.40

Other reports have described facial erythematous papules with sorafenib.41 In these patients, facial erythema usually occurs within 1 to 2 weeks after initiation of treatment, unlike hand-foot skin reaction, which usually develops later.42

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitor Drug Eruptions

Monoclonal antibodies against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (eg, cetuximab, panitumumab) and EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (eg, gefitinib, erlotinib) are used in the treatment of several cancers. Use of these drugs has been associated with various dermatologic side effects, including rashes, paronychia and fissuring of the nail bed, hair changes, dry skin, hypersensitivity reactions, and mucositis.43 The most frequent dermatologic side effect is a sterile follicular and pustular rash, often affecting the face, that is seen in more than half of the patients treated with these drugs.43,44 These rosacealike facial lesions are accompanied by diffuse erythema and telangiectasia. In some cases, the pustules leave areas of erythema covered with greasy scaling, thus resembling seborrheic dermatitis.43 In general, the pustular rash manifests within 1 to 3 weeks after the onset of treatment with EGFR inhibitors. The reaction typically resolves within 4 weeks of stopping treatment.44 The etiology of the rash is unknown, but inhibition of EGFR may result in occlusion of hair follicles and their associated sebaceous glands, producing a rosacealike appearance.45

Conclusion

Since its first medical description, rosacea has undergone extensive study regarding its pathogenesis and management. The most current investigations indicate microorganisms such as D folliculorum and H pylori as etiologic factors, though several other possibilities (eg, vascular abnormalities) have been suggested. Understanding the clinical variants and disease course of rosacea is important in differentiating this entity from other conditions that can mimic rosacea.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank Jennifer Rullan, MD, San Diego, California, and Jose Gonzalez-Chavez, MD, San Juan, Puerto Rico, for their assistance.

1. Bateman T, Thomson AT, Willan R. A Practical Synopsis of Cutaneous Diseases According to the Arrangement of Dr. Willan, Exhibiting a Concise View of the Diagnostic Symptoms and the Method of Treatment. London, England: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Browne; 1813.

2. Plewig G, Kligman AM. Acne and Rosacea. 3rd ed. Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2000.

3. Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

4. Crawford GH, Pelle MT, James WD. Rosacea: i. etiology, pathogenesis, and subtype classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:327-341.

5. Clyti E, Nacher M, Sainte-Marie D, et al. Ivermectin treatment of three cases of demodicosis during human immunodeficiency virus infection. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1066-1068.

6. Aquilina C, Viraben R, Sire S. Ivermectin-responsive Demodex infestation during human immunodeficiency virus infection. a case report and literature review. Dermatology. 2002;205:394-397.

7. Brutti CS, Artus G, Luzzatto L, et al. Crusted rosacea-like demodicidosis in an HIV-positive female. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e131-e132.

8. Clyti E, Sayavong K, Chanthavisouk K. Demodicosis in a patient infected by HIV: successful treatment with ivermectin. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2005;132:459-461.

9. Patrizi A, Neri I, Chieregato C, et al. Demodicosis in immunocompetent young children: report of eight cases. Dermatology. 1997;195:239-242.

10. Barrio J, Lecona M, Hernanz JM, et al. Rosacea-like demodicosis in an HIV-positive child. Dermatology. 1996;192:143-145.

11. Vin-Christian K, Maurer TA, Berger TG. Acne rosacea as a cutaneous manifestation of HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:139-140.

12. Tüzün Y, Keskin S, Kote E. The role of Helicobacter pylori infection in skin diseases: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:478-482.

13. El-Khalawany M, Mahmoud A, Mosbeh AS, et al. Role of Helicobacter pylori in common rosacea subtypes: a genotypic comparative study of Egyptian patients. J Dermatol. 2012;39:989-995.

14. Boixeda de Miquel D, Vázquez Romero M, Vázquez Sequeiros E, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in rosacea patients [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2006;98:501-509.

15. Marzano AV, Lazzari R, Polloni I, et al. Rosacea-like cutaneous lupus erythematosus: an atypical presentation responding to antimalarials. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:106-107.

16. Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous features of classic dermatomyositis and amyopathic dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:475-482.

17. Okiyama N, Kohsaka H, Ueda N, et al. Seborrheic area erythema as a common skin manifestation in Japanese patients with dermatomyositis. Dermatology. 2008;217:374-377.

18. Naleway AL, Greenlee RT, Melski JW. Characteristics of diagnosed polymorphous light eruption. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2006;22:205-207.

19. Tutrone WD. Polymorphic light eruption. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:28-39.

20. Sampaio AL, Mameri AC, Vargas TJ, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1061-1071.

21. Cordain L, Lindberg S, Hurtado M, et al. Acne vulgaris: a disease of Western civilization. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1584-1590.

22. Titus S, Hodge J. Diagnosis and treatment of acne. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:734-740.

23. Poulos GA, Brodell RT. Perioral dermatitis associated with an inhaled corticosteroid. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1460.

24. Bhat YJ, Manzoor S, Qayoom S. Steroid-induced rosacea: a clinical study of 200 patients. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:30-32.

25. Bell HK, Poston GJ, Vora J, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of the malignant carcinoid syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:71-75.

26. Creamer JD, Whittaker SJ, Griffiths WA. Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 presenting as rosacea. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:170-171.

27. Reichert S, Truchetet F, Cuny JF, et al. Carcinoid tumor with revealed by skin manifestation [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1994;121:485-488.

28. Findlay GH, Simson IW. Leonine hypertrophic rosacea associated with a benign bronchial carcinoid tumour. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1977;2:175-176.

29. Barzilai A, Feuerman H, Quaglino P, et al. Cutaneous B-cell neoplasms mimicking granulomatous rosacea or rhinophyma. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:824-831.

30. Moulonguet I, Ghnassia M, Molina T, et al. Miliarial-type perifollicular B-cell pseudolymphoma (lymphocytoma cutis): a misleading eruption in two women. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:1016-1021.

31. Soon CW, Pincus LB, Ai WZ, et al. Acneiform presentation of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:887-889.

32. Rosmaninho A, Alves R, Lima M, et al. Red nose: primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Res. 2010;34:682-684.

33. Ogden S, Coulson IH. B-cell lymphoma mimicking rhinophyma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:213-214.

34. Seward JL, Malone JC, Callen JP. Rhinophymalike swelling in an 86-year-old woman. Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma of the nose. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:751-756.

35. Colvin JH, Lamerson CL, Cualing H, et al. Cutaneous lymphoplasmacytoid lymphoma (immunocytoma) with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia mimicking rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1159-1162.

36. Jih MH, Friedman PM, Kimyai-Asadi A, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei treatment with the 1450-nm diode laser. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:143-145.

37. Abdullah L, Abbas O. Dermacase. can you identify this condition? lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:795-796.

38. van de Scheur MR, van der Waal RI, Starink TM. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei: a distinctive rosacea-like syndrome and not a granulomatous form of rosacea. Dermatology. 2003;206:120-123.

39. Skowron F, Causeret AS, Pabion C, et al. F.I.GU.R.E.: facial idiopathic granulomas with regressive evolution. is ‘lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei’ still an acceptable diagnosis in the third millennium? Dermatology. 2000;201:287-289.

40. Lee WJ, Lee JL, Chang SE, et al. Cutaneous adverse effects in patients treated with the multitargeted kinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:1045-1051.

41. Kim DH, Son IP, Lee JW, et al. Sorafenib (Nexavar®, BAY 43-9006)–induced hand-foot skin reaction with facial erythema. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:119-122.

42. Sahai S, Swick BL. Hyperkeratotic eruption, hand-foot skin reaction, facial erythema, and stomatitis secondary to multi-targeted kinase inhibitor sorafenib. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1203-1206.

43. Segaert S, Van Cutsem E. Clinical signs, pathophysiology and management of skin toxicity during therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1425-1433.

44. Agero AL, Dusza SW, Benvenuto-Andrade C, et al. Dermatologic side effects associated with the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:657-670.

45. Acharya J, Lyon C, Bottomley DM. Folliculitis-perifolliculitis related to erlotinib therapy spares previously irradiated skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:154-157.

Although rosacea is one of the most common conditions treated by dermatologists, it also is one of the most misunderstood. Historically, large noses due to rhinomegaly were associated with indulgence in wine and wealth.1 The term rosacea is derived from the Latin adjective meaning “like roses.” Rosacea was first medically described in French as goutterose (pink droplet) and pustule de vin (pimples of wine).1 This article reviews the characteristics of rosacea compared to several mimickers of rosacea that physicians should consider.

Rosacea Characteristics

Rosacea is a chronic disorder affecting the central parts of the face that is characterized by frequent flushing; persistent erythema (ie, lasting for at least 3 months); telangiectasia; and interspersed episodes of inflammation with swelling, papules, and pustules.2 It is most commonly seen in adults older than 30 years and is considered to have a strong hereditary component, as it is more commonly seen in individuals of Celtic and Northern European descent as well as those with fair skin. Furthermore, approximately 30% to 40% of patients report a family member with the condition.2

Rosacea Subtypes

In a 2002 meeting held to standardize the diagnostic criteria for rosacea, the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea described 4 broad clinical subtypes of rosacea: erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular.3 More than 1 subtype may present in the same patient. A progression from one subtype to another can occur in cases of severe papulopustular or glandular rosacea that eventuate into the phymatous form.2 Moreover, not all of the disease features are present in every patient. Secondary features of rosacea include burning or stinging, edema, plaques, dry appearance of the skin, ocular manifestations, peripheral site involvement, and phymatous changes.

In erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, episodic flushing occurs, which can last longer than 10 minutes with the central face exhibiting the most intense color. The redness also may involve the peripheral portion of the face as well as extrafacial areas (eg, ears, scalp, neck, chest). Periocular skin is spared. The stimuli that may bring on flushing include short-term emotional stress, hot drinks, alcohol, spicy foods, exercise, cold or hot weather, and hot water.3

Patients with papulopustular rosacea generally present with redness of the central portion of the face along with persistent or intermittent flares characterized by small papules and pinpoint pustules. There also is an almost universal sparing of the periocular skin, and a history of flushing often is present; however, flushing usually is milder than in the erythematotelangiectatic subtype. The constant inflammation may lead to chronic edema and phymatous changes, which occur more commonly in men than in women.3

Phymatous rosacea is characterized by marked skin thickening and irregular surface nodularities, most commonly involving the nose (rhinophyma), though the chin (gnathophyma), forehead (metophyma), ears (otophyma), and eyelids (blepharophyma) also are occasionally affected. There are 4 variants of rhinophyma with distinct histopathologic features: glandular, fibrous, fibroangiomatous, and actinic.3 The glandular variant is most often seen in men who have thick sebaceous skin. Edematous papules and pustules often are large and may be accompanied by nodulocystic lesions. Frequently, affected patients will have a history of adolescent acne with scarring.

Ocular rosacea may precede cutaneous findings by many years; however, in most cases the ocular findings occur concurrently or develop later on in the disease course. The most consistent findings in ocular rosacea are blepharitis and conjunctivitis. Symptoms of burning or stinging, itching, light sensitivity, and a foreign body sensation are common in these patients.3

Pathogenesis

Several investigators have proposed that Demodex folliculorum may play a pathogenic role in rosacea. Demodex is a common inhabitant of normal human skin, and its role in human disease is a matter of controversy.3Demodex has a predilection for the regions of the skin that are most often affected by rosacea, such as the nose and cheeks. The clinical manifestations of rosacea tend to appear later in life, which parallels the increase in the density of Demodex mites that occurs with age.4 It has been hypothesized that beneficial effects of metronidazole in the treatment of rosacea may be related to an antiparasitic effect on Demodex; however, these mites can survive high concentrations of the drug.3 Moreover, modern techniques that employ cyanoacrylate surface biopsies, which are extremely sensitive, estimate that the prevalence of Demodex in healthy skin approaches 100%.4 Consequently, the simple identification of Demodex is by no means proof of pathogenesis. Whether Demodex is truly pathogenic or simply an inhabitant of follicles in rosacea-prone skin remains a subject for future investigation.

Demodicosis occurs mainly in immunosuppressed patients because immunosuppression influences the number of Demodex mites and the treatment response. Multiple patients with AIDS and/or those with a CD4 lymphocyte count below 200/mm3 have been reported to have demodicosis.5-11 In immunocompetent patients, pruritic papular, papulopustular, and nodular lesions occur on the face, but in immunocompromised patients, the eruption may be more diffuse, affecting the back, presternal area, and upper limbs.6 A correct diagnosis relies on suggestive clinical signs, the presence of numerous parasites on direct examination, and a good clinical response to acaricide treatment.

Helicobacter pylori seropositivity has been associated with various dermatologic disorders, including rosacea.12 However, robust support for a causal association between H pylori and rosacea does not exist. Several studies have demonstrated high prevalence rates of H pylori in rosacea patients, some even in comparison with age- and sex-matched controls.13,14 Moreover, treatments aimed at eradicating H pylori also beneficially influence the clinical outcome of rosacea; for instance, metronidazole, a common treatment of roscea, is an effective agent against H pylori.

Understanding the clinical variants and disease course of rosacea is important to differentiate this entity from other conditions that can mimic rosacea. Laboratory studies and histopathologic examination via skin biopsy may be needed to differentiate between rosacea and rosacealike conditions.

Common Rosacealike Conditions

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory disease that has protean clinical manifestations and follows a relapsing and remitting course. Characteristic malar erythema appears in approximately 50% of patients and may accompany or precede other symptoms of lupus. The affected skin generally feels warm and appears slightly edematous. The erythema may last for hours to days and often recurs, particularly with sun exposure. The malar erythema of SLE can be confused with the redness of erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. Nevertheless, the color of the skin in SLE has a violaceous quality and may show a more abrupt cutoff, especially at its most lateral margins. Marzano et al15 reported 4 cases in which lupus erythematosus was misdiagnosed as rosacea. All 4 patients presented with erythema that was localized to the central face along with a few raised, smooth, round, erythematous to violaceous papules over the malar areas and the forehead. This presentation evolved rapidly and was aggravated by sun exposure. The patients were all treated with medication for rosacea but showed no improvement. These patients originally presented with limited skin involvement in the absence of any systemic sign or symptoms of SLE.15

Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an inflammatory myopathy characterized by varying degrees of muscle weakness and distinctive skin erythema (Figure 1); however, some patients lack muscular involvement and initially present with skin manifestations only. Sontheimer16 described criteria for defining skin involvement in DM. Major criteria include the heliotrope rash, Gottron papules, and Gottron sign, while minor criteria include macular violaceous erythema (MVE), periungual telangiectasia of the nail fold, poikiloderma, mechanic’s hands, cutaneous calcinosis, cutaneous ulcers, and pruritus. With the exception of the heliotrope rash, facial erythema has drawn little attention in prior studies of DM-associated skin manifestations. Therefore, Okiyama et al17 performed a retrospective study on the skin manifestations of DM in 33 patients. The investigators observed that MVE in the seborrheic area of the face was most frequent.17 Therefore, it is critical to consider DM in the differential diagnosis of rosacea because the MVE seen in DM might be confused with the erythema seen in rosacea.

|

| Figure 1. Macular violaceous erythema of the face in a patient with dermatomyositis. Photograph courtesy of Marc Silverstein, MD, Sacramento, California. |

|

Figure 2. Polymorphous light eruption manifesting as erythematous papules over the cheek and dorsal aspect of the nose. Photograph courtesy of Marc Silverstein, MD, Sacramento, California. |

Polymorphous Light Eruption

Polymorphous light eruption (PMLE), the most common of the idiopathic photodermatoses, is characterized by erythematous papules, papulovesicles, and plaques on sun-exposed surfaces (Figure 2). The areas of the skin that are most commonly affected are the face, neck, outer aspects of the arms, and dorsal surfaces of the hands.18 Lesions may appear immediately but often develop several hours after sun exposure. Symptoms of itching and/or burning usually are mild and transient. The etiology of PMLE is unknown, though it is likely to be multifactorial.

Similarities between PMLE and rosacea include exacerbation by sun exposure and a higher prevalence in fair-skinned individuals.19 Also, in both conditions erythematous papules appear on the face and may be pruritic and in some instances painful; however, unlike rosacea, which is chronic, PMLE tends to be intermittent and recurrent, typically occurring in the spring and early summer months. In contrast to rosacea, the onset of the erythema in PMLE is abrupt, appearing quickly after sun exposure and subsiding within 1 to 7 days. Furthermore, patients with PMLE may experience systemic flulike symptoms after sun exposure.19

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic relapsing papulosquamous skin disease most commonly involving sebum-rich areas such as the scalp and face. The prevalence of seborrheic dermatitis is higher in human immunodeficiency virus–positive individuals and in patients with neurologic conditions such as Parkinson disease. The pathogenesis of seborrheic dermatitis has been linked to the yeast of Malassezia species, immunologic abnormalities, and activation of complements. A clinical diagnosis usually is made based on a history of waxing and waning in severity and by the sites of involvement.20

Similar to rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic and relapsing erythematous rash with well-demarcated erythematous patches, papules, or plaques; however, unlike rosacea, the distribution varies from minimal asymptomatic scaliness of the scalp to more widespread involvement (eg, scalp, ears, upper aspect of the trunk, intertriginous areas). Also, although macular erythema and scaling involving the perinasal area (Figure 3) may be seen in either rosacea or seborrheic dermatitis, a greasy quality to the scales and involvement of other sites such as the scalp, retroauricular skin, and eyebrows suggest a diagnosis of seborrheic dermatitis.

Acne Vulgaris

Acne vulgaris is the most common skin disease in the United States.21 It is characterized by noninflammatory; open or closed comedones; and inflammatory papules, pustules, and nodules. Acne vulgaris typically affects the areas of skin with the highest density of sebaceous follicles including the face, upper aspect of the chest, and back.22 It is the most common skin disease in the differential diagnosis of the papulopustular form of rosacea. Inflammatory lesions in both acne vulgaris and rosacea may be clinically identical; however, unlike acne vulgaris, rosacea is characterized by a complete absence of comedones. A prominent centrofacial distribution also favors rosacea. As a general rule, acne peaks in adolescence, years before papulopustular rosacea usually becomes prominent. However, some acne patients who are prone to flushing and blushing may develop rosacea later in life.

Topical Steroid–Induced Acne

Chronic use of topical corticosteroids on the face for several months can result in the appearance of monomorphic inflammatory papules (Figure 4). Corticosteroids can cause a dry scaly eruption with scattered follicular pustules around the mouth (perioral dermatitis).23 This acneform eruption is indistinguishable from rosacea. However, the monomorphic inflammatory papules generally resolve within 1 to 2 months following discontinuation of the corticosteroid therapy.

Multiple pathways have been proposed as the mechanism for such reactions, including rebound vasodilation and proinflammatory cytokine release by chronic intermittent steroid exposure.24 At first, the vasoconstrictive and anti-inflammatory effects of the steroids result in what seems to be clearance of the primary dermatitis for which the steroids were being used. Unfortunately, persistent use of steroids, particularly high-potency products, leads to epidermal atrophy, degeneration of dermal structures, and destruction of collagen, rendering the skin vulnerable to bacterial, viral, and fungal infections. In the end, the skin has the appearance of bright red rosacea with red scaly papules.

Rare Rosacealike Conditions

Carcinoid Syndrome

Carcinoid syndrome typically develops after hepatic metastasis from a carcinoid tumor when the circulating neuroendocrine mediators produced by the tumor can no longer be adequately cleared. Flushing is characteristic of carcinoid syndrome and usually presents on the face, neck, and upper trunk. Although rare, other types of cutaneous involvement also have been reported.25 Bell et al25 concluded that skin involvement is not uncommon in carcinoid syndrome, as all 25 patients with carcinoid syndrome showed cutaneous involvement in their case series. The investigators observed that chronic flushing eventually may become permanent and evolve into a rosacealike picture.25

Cases of carcinoid syndrome that were misdiagnosed as rosacea have been reported in the literature.26-28 Creamer et al26 reported a case of a 67-year-old woman who initially was diagnosed with rosacea; it took 1 year to finally arrive at the correct diagnosis of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 after developing a malignant carcinoid tumor and a parathyroid tumor.

Cutaneous Lymphoma

B-cell neoplasms with skin involvement can present as primary cutaneous lymphomas or as secondary processes, including specific infiltrates of nodal or extranodal lymphoma or leukemia.29 B-cell lymphomas involving the skin have a distinct clinical appearance, presenting as isolated, grouped, or multiple erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules, usually in an asymmetric distribution (Figure 5). B-cell lymphoproliferative diseases simulating rosacea are extremely rare.29 Nevertheless, B-cell lymphoma mimicking rhinophyma has been documented in the literature.29-35

Barzilai et al29 described 12 patients with B-cell lymphoproliferative neoplasms presenting with facial eruptions that clinically mimicked rosacea or rhinophyma. The clinical presentation included small papules on the nose, cheeks, and around the eyes mimicking granulomatous rosacea, and/or nodules on the nose, cheeks, chin, or forehead simulating phymatous rosacea. Three patients had preexisting erythematotelangiectatic rosacea and 1 had rhinophyma.29

Lupus Miliaris Disseminatus Faciei

Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF) is an uncommon chronic inflammatory skin disorder characterized by the appearance of asymptomatic small, red to yellowish brown papules on the face.36 This rare dermatologic disease usually is self-limited with spontaneous resolution of the lesions occurring within months or years; however, residual disfiguring scars may persist and usually are characteristic of LMDF.36,37 The pathogenesis of LMDF is unclear, and controversy remains as to whether it is a distinct cutaneous entity or a variant of granulomatous rosacea.38,39 It usually develops slowly as small, dome-shaped, red to yellowish brown papules in adults, most commonly appearing in men.39 Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei shares several common features with both acne vulgaris and rosacea. For example, the inflammatory lesions of LMDF are located on the central face and usually respond to treatments that typically are used to treat acne vulgaris and rosacea. However, LMDF can be distinguished histologically by more intense granulomatous inflammation and central caseation, occurring in the absence of an apparent infectious origin.36

Tyrosinase Kinase Inhibitor Drug Eruptions

Sorafenib and sunitinib malate are multitargeted kinase inhibitors approved for the treatment of cancers such as renal cell carcinoma.40 A study by Lee et al40 reported that approximately 75% of patients treated with either sorafenib (n=109) or sunitinib (n=119) went on to develop at least one cutaneous reaction. Although hand-foot skin reaction was the most common and serious cutaneous side effect, other dermatologic manifestations, including alopecia, stomatitis, discoloration (hair or face), subungual splinter hemorrhages, facial swelling, facial erythema, and xerosis, were described. Facial changes such as swelling, yellowish discoloration, erythema, and acneform eruptions were described more frequently in patients treated with sunitinib than in those treated with sorafenib.40

Other reports have described facial erythematous papules with sorafenib.41 In these patients, facial erythema usually occurs within 1 to 2 weeks after initiation of treatment, unlike hand-foot skin reaction, which usually develops later.42

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitor Drug Eruptions

Monoclonal antibodies against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (eg, cetuximab, panitumumab) and EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (eg, gefitinib, erlotinib) are used in the treatment of several cancers. Use of these drugs has been associated with various dermatologic side effects, including rashes, paronychia and fissuring of the nail bed, hair changes, dry skin, hypersensitivity reactions, and mucositis.43 The most frequent dermatologic side effect is a sterile follicular and pustular rash, often affecting the face, that is seen in more than half of the patients treated with these drugs.43,44 These rosacealike facial lesions are accompanied by diffuse erythema and telangiectasia. In some cases, the pustules leave areas of erythema covered with greasy scaling, thus resembling seborrheic dermatitis.43 In general, the pustular rash manifests within 1 to 3 weeks after the onset of treatment with EGFR inhibitors. The reaction typically resolves within 4 weeks of stopping treatment.44 The etiology of the rash is unknown, but inhibition of EGFR may result in occlusion of hair follicles and their associated sebaceous glands, producing a rosacealike appearance.45

Conclusion

Since its first medical description, rosacea has undergone extensive study regarding its pathogenesis and management. The most current investigations indicate microorganisms such as D folliculorum and H pylori as etiologic factors, though several other possibilities (eg, vascular abnormalities) have been suggested. Understanding the clinical variants and disease course of rosacea is important in differentiating this entity from other conditions that can mimic rosacea.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank Jennifer Rullan, MD, San Diego, California, and Jose Gonzalez-Chavez, MD, San Juan, Puerto Rico, for their assistance.

Although rosacea is one of the most common conditions treated by dermatologists, it also is one of the most misunderstood. Historically, large noses due to rhinomegaly were associated with indulgence in wine and wealth.1 The term rosacea is derived from the Latin adjective meaning “like roses.” Rosacea was first medically described in French as goutterose (pink droplet) and pustule de vin (pimples of wine).1 This article reviews the characteristics of rosacea compared to several mimickers of rosacea that physicians should consider.

Rosacea Characteristics

Rosacea is a chronic disorder affecting the central parts of the face that is characterized by frequent flushing; persistent erythema (ie, lasting for at least 3 months); telangiectasia; and interspersed episodes of inflammation with swelling, papules, and pustules.2 It is most commonly seen in adults older than 30 years and is considered to have a strong hereditary component, as it is more commonly seen in individuals of Celtic and Northern European descent as well as those with fair skin. Furthermore, approximately 30% to 40% of patients report a family member with the condition.2

Rosacea Subtypes

In a 2002 meeting held to standardize the diagnostic criteria for rosacea, the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the Classification and Staging of Rosacea described 4 broad clinical subtypes of rosacea: erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular.3 More than 1 subtype may present in the same patient. A progression from one subtype to another can occur in cases of severe papulopustular or glandular rosacea that eventuate into the phymatous form.2 Moreover, not all of the disease features are present in every patient. Secondary features of rosacea include burning or stinging, edema, plaques, dry appearance of the skin, ocular manifestations, peripheral site involvement, and phymatous changes.

In erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, episodic flushing occurs, which can last longer than 10 minutes with the central face exhibiting the most intense color. The redness also may involve the peripheral portion of the face as well as extrafacial areas (eg, ears, scalp, neck, chest). Periocular skin is spared. The stimuli that may bring on flushing include short-term emotional stress, hot drinks, alcohol, spicy foods, exercise, cold or hot weather, and hot water.3

Patients with papulopustular rosacea generally present with redness of the central portion of the face along with persistent or intermittent flares characterized by small papules and pinpoint pustules. There also is an almost universal sparing of the periocular skin, and a history of flushing often is present; however, flushing usually is milder than in the erythematotelangiectatic subtype. The constant inflammation may lead to chronic edema and phymatous changes, which occur more commonly in men than in women.3