User login

Papular Eruption Following Excessive Tanning Bed Use

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis

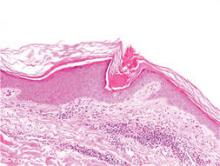

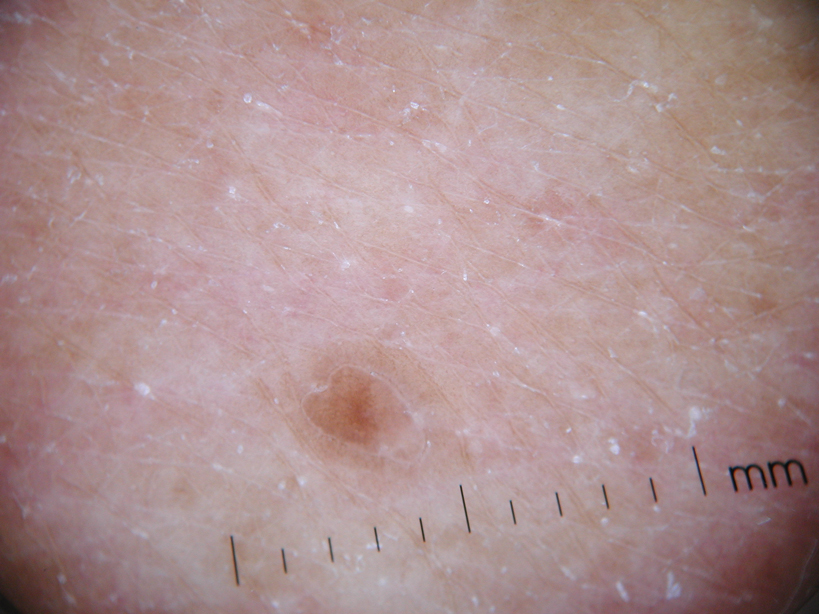

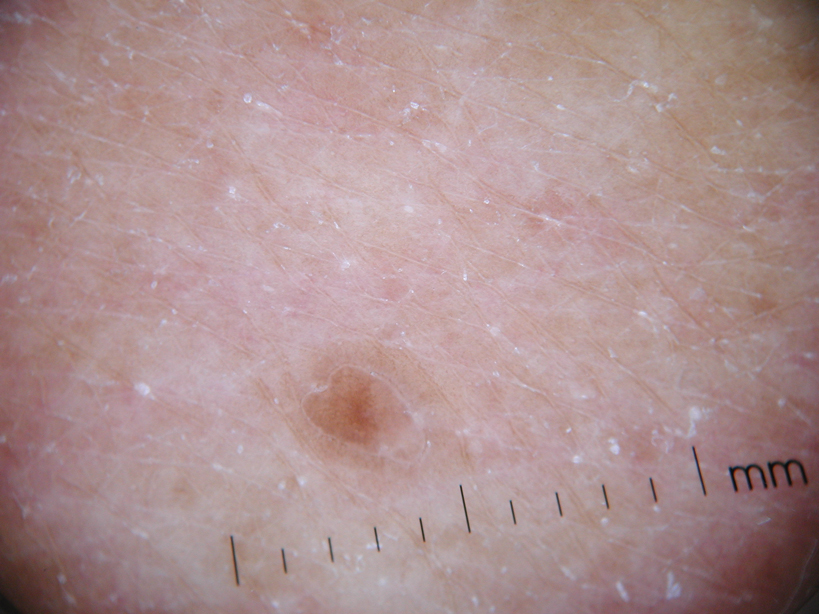

Physical examination after 7 years of tanning salon use showed a tanned white man with multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs that were rough to palpate (Figure 1), with a peripheral rim of scale seen more prominently on dermoscopy. There were no lesions on the palms or soles. A subsequent 4-mm punch biopsy was done on the right abdomen and right thigh, which showed focal thinning of the epidermis, loss of the granular layer, a discrete column of parakeratosis and a characteristic feature of a coronoid lamella in the epidermis (Figure 2). The patient received 14 narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) treatments; however, he could not continue due to transportation issues. He visited the clinic sporadically for 6 months thereafter and reportedly went to tanning salons daily. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

|

|

| Figure 1. Multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the abdomen (A) and leg (B) that were rough to palpate. |

Disseminated porokeratosis, or disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), was first described in 1967 by Chernosky and Freeman.1 It is the most common variant of porokeratosis. Other variants include Mibelli type, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, punctuate porokeratosis, and linear porokeratosis.2-4 Porokeratosis is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, presenting in the third or fourth decades of life; however, most cases are sporadic.5 Pruritus is a common symptom and can be debilitating.5

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis can be precipitated by excessive sun exposure, with a reported increase in lesions during summer months and resolution during the winter months.6 The lesions of DSAP can be experimentally induced by exposure to daily use of artificial UV sunlamps.7 Patients with psoriasis undergoing psoralen plus UVA and NB-UVB treatments also have been reported to trigger DSAP.8 A study by Neumann et al6 suggested that a combination of both UVB and UVA wavelengths may be most effective in inducing DSAP. Exposure to UVA and UVB light may explain an increased number of DSAP lesions in patients who excessively visit tanning salons, as the bulbs emit a combination of wavelengths with UVA in much greater amounts than UVB.

Our patient developed DSAP secondary to artificial UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use. Medications (allopurinol and lisinopril) were initially thought to be etiologic agents for the eruption and also corroborated with histologic findings of a drug eruption on the initial biopsy. However, new lesions continued to develop even after cessation of medications and NB-UVB treatments. A subsequent biopsy and further history of daily tanning salon use confirmed the diagnosis of DSAP.

Therapies for this condition are limited with variable degrees of success. Cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil cream, imiquimod cream 5%, Q-switched ruby laser, diclofenac gel 3%, and acitretin for more widespread or refractory lesions have been used with partial to complete resolution of DSAP.9

We present this case to highlight the occurrence of DSAP secondary to UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use.

1. Chernosky ME, Freeman RG. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP). Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:611-624.

2. Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris et disseminata: a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

3. Brown FC. Punctate keratoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:682-683.

4. Eyre WG, Carson WE. Linear porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:426-429.

5. Anderson DE, Chernosky ME. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:408-412.

6. Neumann RA, Knobler RM, Jurecka W, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: experimental induction and exacerbation of skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1182-1188.

7. Chernosky ME, Anderson DE. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: clinical studies and experimental production of lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:401-407.

8. Allen LA, Glaser DA. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis associated with topical PUVA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:720-722.

9. Arun B, Pearson J, Chalmers R. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis treated effectively with topical imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:509-511.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis

Physical examination after 7 years of tanning salon use showed a tanned white man with multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs that were rough to palpate (Figure 1), with a peripheral rim of scale seen more prominently on dermoscopy. There were no lesions on the palms or soles. A subsequent 4-mm punch biopsy was done on the right abdomen and right thigh, which showed focal thinning of the epidermis, loss of the granular layer, a discrete column of parakeratosis and a characteristic feature of a coronoid lamella in the epidermis (Figure 2). The patient received 14 narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) treatments; however, he could not continue due to transportation issues. He visited the clinic sporadically for 6 months thereafter and reportedly went to tanning salons daily. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

|

|

| Figure 1. Multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the abdomen (A) and leg (B) that were rough to palpate. |

Disseminated porokeratosis, or disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), was first described in 1967 by Chernosky and Freeman.1 It is the most common variant of porokeratosis. Other variants include Mibelli type, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, punctuate porokeratosis, and linear porokeratosis.2-4 Porokeratosis is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, presenting in the third or fourth decades of life; however, most cases are sporadic.5 Pruritus is a common symptom and can be debilitating.5

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis can be precipitated by excessive sun exposure, with a reported increase in lesions during summer months and resolution during the winter months.6 The lesions of DSAP can be experimentally induced by exposure to daily use of artificial UV sunlamps.7 Patients with psoriasis undergoing psoralen plus UVA and NB-UVB treatments also have been reported to trigger DSAP.8 A study by Neumann et al6 suggested that a combination of both UVB and UVA wavelengths may be most effective in inducing DSAP. Exposure to UVA and UVB light may explain an increased number of DSAP lesions in patients who excessively visit tanning salons, as the bulbs emit a combination of wavelengths with UVA in much greater amounts than UVB.

Our patient developed DSAP secondary to artificial UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use. Medications (allopurinol and lisinopril) were initially thought to be etiologic agents for the eruption and also corroborated with histologic findings of a drug eruption on the initial biopsy. However, new lesions continued to develop even after cessation of medications and NB-UVB treatments. A subsequent biopsy and further history of daily tanning salon use confirmed the diagnosis of DSAP.

Therapies for this condition are limited with variable degrees of success. Cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil cream, imiquimod cream 5%, Q-switched ruby laser, diclofenac gel 3%, and acitretin for more widespread or refractory lesions have been used with partial to complete resolution of DSAP.9

We present this case to highlight the occurrence of DSAP secondary to UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use.

The Diagnosis: Disseminated Superficial Actinic Porokeratosis

Physical examination after 7 years of tanning salon use showed a tanned white man with multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs that were rough to palpate (Figure 1), with a peripheral rim of scale seen more prominently on dermoscopy. There were no lesions on the palms or soles. A subsequent 4-mm punch biopsy was done on the right abdomen and right thigh, which showed focal thinning of the epidermis, loss of the granular layer, a discrete column of parakeratosis and a characteristic feature of a coronoid lamella in the epidermis (Figure 2). The patient received 14 narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) treatments; however, he could not continue due to transportation issues. He visited the clinic sporadically for 6 months thereafter and reportedly went to tanning salons daily. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

|

|

| Figure 1. Multiple 4- to 5-mm, discrete, round to oval, reddish brown papules on the abdomen (A) and leg (B) that were rough to palpate. |

Disseminated porokeratosis, or disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP), was first described in 1967 by Chernosky and Freeman.1 It is the most common variant of porokeratosis. Other variants include Mibelli type, porokeratosis palmaris et plantaris disseminata, punctuate porokeratosis, and linear porokeratosis.2-4 Porokeratosis is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion, presenting in the third or fourth decades of life; however, most cases are sporadic.5 Pruritus is a common symptom and can be debilitating.5

Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis can be precipitated by excessive sun exposure, with a reported increase in lesions during summer months and resolution during the winter months.6 The lesions of DSAP can be experimentally induced by exposure to daily use of artificial UV sunlamps.7 Patients with psoriasis undergoing psoralen plus UVA and NB-UVB treatments also have been reported to trigger DSAP.8 A study by Neumann et al6 suggested that a combination of both UVB and UVA wavelengths may be most effective in inducing DSAP. Exposure to UVA and UVB light may explain an increased number of DSAP lesions in patients who excessively visit tanning salons, as the bulbs emit a combination of wavelengths with UVA in much greater amounts than UVB.

Our patient developed DSAP secondary to artificial UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use. Medications (allopurinol and lisinopril) were initially thought to be etiologic agents for the eruption and also corroborated with histologic findings of a drug eruption on the initial biopsy. However, new lesions continued to develop even after cessation of medications and NB-UVB treatments. A subsequent biopsy and further history of daily tanning salon use confirmed the diagnosis of DSAP.

Therapies for this condition are limited with variable degrees of success. Cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil cream, imiquimod cream 5%, Q-switched ruby laser, diclofenac gel 3%, and acitretin for more widespread or refractory lesions have been used with partial to complete resolution of DSAP.9

We present this case to highlight the occurrence of DSAP secondary to UV light exposure from excessive tanning salon use.

1. Chernosky ME, Freeman RG. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP). Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:611-624.

2. Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris et disseminata: a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

3. Brown FC. Punctate keratoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:682-683.

4. Eyre WG, Carson WE. Linear porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:426-429.

5. Anderson DE, Chernosky ME. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:408-412.

6. Neumann RA, Knobler RM, Jurecka W, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: experimental induction and exacerbation of skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1182-1188.

7. Chernosky ME, Anderson DE. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: clinical studies and experimental production of lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:401-407.

8. Allen LA, Glaser DA. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis associated with topical PUVA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:720-722.

9. Arun B, Pearson J, Chalmers R. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis treated effectively with topical imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:509-511.

1. Chernosky ME, Freeman RG. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis (DSAP). Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:611-624.

2. Guss SB, Osbourn RA, Lutzner MA. Porokeratosis plantaris, palmaris et disseminata: a third type of porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:366-373.

3. Brown FC. Punctate keratoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1971;104:682-683.

4. Eyre WG, Carson WE. Linear porokeratosis of Mibelli. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:426-429.

5. Anderson DE, Chernosky ME. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:408-412.

6. Neumann RA, Knobler RM, Jurecka W, et al. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: experimental induction and exacerbation of skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:1182-1188.

7. Chernosky ME, Anderson DE. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: clinical studies and experimental production of lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:401-407.

8. Allen LA, Glaser DA. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis associated with topical PUVA. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:720-722.

9. Arun B, Pearson J, Chalmers R. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis treated effectively with topical imiquimod 5% cream. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:509-511.

A 78-year-old man with Fitzpatrick skin type III presented to the dermatology department for evaluation of a pruritic, erythematous, papular eruption on the chest, back, abdomen, arms, and legs of 5 years’ duration. His medications include clonazepam, lisinopril, allopurinol, omeprazole, tramadol, and mirtazapine. The lesions did not respond to topical corticosteroids; however, the pruritus improved with narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) treatments. Review of systems did not reveal any abnormalities. The patient’s medical history included gout, hypertension, anxiety, esophageal stricture, and emphysema. He reported a history of tanning salon use at least 3 times weekly for 7 years. After initial consultation, the patient was treated with clobetasol propionate cream 0.05% twice daily and hydroxyzine 10 mg 3 times daily. Following 1 month of treatment, the eruption did not improve. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the left upper arm revealed a dense infiltrate in the upper dermis with prominent parakeratosis, lymphocytes, and numerous eosinophils, suggestive of a drug eruption. As a result, allopurinol was discontinued as a causative agent; however, the eruption presented prior to taking allopurinol. Because the patient experienced intense pruritus, he was started on NB-UVB treatments. After 14 treatments of NB-UVB 3 times weekly, the patient noticed some improvement with respect to pruritus, but the lesions did not resolve. A complete blood cell count indicated 7.6% eosinophils (reference range, 0%–5%). Liver function tests, complete metabolic profile, and renal function were within reference range. Lisinopril was then discontinued as a likely culprit for persistent drug eruption; however, new lesions continued to develop.