User login

The Effects of a Multifaceted Intervention to Improve Care Transitions Within an Accountable Care Organization: Results of a Stepped-Wedge Cluster-Randomized Trial

The Effects of a Multifaceted Intervention to Improve Care Transitions Within an Accountable Care Organization: Results of a Stepped-Wedge Cluster-Randomized Trial

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Transitions from the hospital to the ambulatory setting are high-risk periods for patients in terms of adverse events, poor clinical outcomes, and readmission. Processes of care during care transitions are suboptimal, including poor communication among inpatient providers, patients, and ambulatory providers1,2; suboptimal communication of postdischarge plans of care to patients and their ability to carry out these plans3; medication discrepancies and nonadherence after discharge4; and lack of timely follow-up with ambulatory providers.5 Healthcare organizations continue to struggle with the question of which interventions to implement and how best to implement them.

Interventions to improve care transitions typically focus on readmission rates, but some studies have focused on postdischarge adverse events, defined as injuries in the 30 days after discharge caused by medical management rather than underlying disease processes.2 These adverse events cause psychological distress, out-of-pocket expenses, decreases in functional status, and caregiver burden. An estimated 20% of hospitalized patients suffer a postdischarge adverse event.1,2 Approximately two-thirds of these may be preventable or ameliorable.

The advent of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), defined as “groups of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers who come together voluntarily to give coordinated high quality care to their patients,” creates an opportunity for improvements in patient safety during care transitions.6 Another opportunity has been the advent of Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH), consisting of patient-oriented, comprehensive, team-based primary care enhanced by health information technology and population-based disease management tools.7,8 In theory, a hospital-PCMH collaboration within an ACO can improve transitional interventions since optimal communication and collaboration are more likely when both inpatient and primary care providers (PCPs) share infrastructure and are similarly incentivized. The objectives of this study were to design and implement a collaborative hospital-PCMH care transitions intervention within an ACO and evaluate its effects.

METHODS

This study was a two-arm, single-blind (blinded outcomes assessor), stepped-wedge, multisite cluster-randomized clinical trial (NCT02130570) approved by the institutional review board of Partners HealthCare.

Study Design and Randomization

The study employed a “stepped-wedge” design, which is a cluster-randomized study design in which an intervention is sequentially rolled out to different groups at different, prespecified, randomly determined times.9 Each cluster (in this case, each primary care practice) served as its own control, while still allowing for adjustment for temporal trends. Originally, 18 practices participated, but one withdrew due to the low number of patients enrolled in the study, leaving 17 clusters and 16 sequences; see Figure 1 of Appendix 1 for a full description of the sample size and timeline for each cluster. Practices were not aware of this timeline until after recruitment.

Study Setting and Participants

Conducted within a large Pioneer ACO in Boston and funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), the Partners-PCORI Transitions Study was designed as a “real-world” quality improvement project. Potential participants were adult patients who were admitted to medical and surgical services of two large academic hospitals (Hospital A and Hospital B) affiliated with an ACO, who were likely to be discharged back to the community, and whose PCP belonged to a primary care practice that was affiliated with the ACO, agreed to participate, and were designated PCMHs or on their way to being designated by meeting certain criteria: electronic health record, patient portal, team-based care, practice redesign, care management, and identification of high-risk patients. See Study Protocol (Appendix 2) for detailed patient and primary care practice inclusion criteria.

Patient Enrollment

Study staff screened participants from a daily automated list of patients admitted the day before, using medical records to determine eligibility, which was then confirmed by the patient’s nurse. Exclusion criteria included likely discharge to a location other than home, being in police custody, lack of a telephone, being homeless, previous enrollment in the study, and being unable to communicate in English or Spanish. Allocation to study arm was concealed until the patient or proxy provided informed written consent. The research assistant administered questionnaires to all study subjects to assess potential confounders and functional status 1 month prior to admission (

Intervention

The intervention was based on a conceptual model of an ideal discharge11 that we developed based on work by Naylor et al,12 work by Coleman and Berenson,3 best practices in medication reconciliation and information transfer according to our own research,13-15 the best examples of interventions to improve the discharge process,12,16,17 and a systematic review of discharge interventions.18 Some of the factors necessary for an ideal care transition include complete, organized, and timely documentation of the patient’s hospital course and postdischarge plan; effective discharge planning; coordination of care among the patient’s providers; methods to ensure medication safety; advanced care planning in appropriate patients; and education and “coaching” of patients and their caregivers so they learn how to manage their conditions. The final multifaceted intervention addressed each component of the ideal discharge and included inpatient and outpatient components (Table 1 and Table 1 of Appendix 1).

Patient and Public Involvement in Research

As with all PCORI-funded studies, this study involved a patient-family advisory council (PFAC). Our PFAC included six recently hospitalized patients or caregivers of recently hospitalized patients. The PFAC participated in monthly meetings throughout the study period. They helped inform the research questions, including confirmation that the endpoints were patient centered, and provided valuable input for the design of the intervention and the patient-facing components of the data collection instruments. They also interviewed several patient participants in the study regarding their experiences with the intervention. Lastly, they helped develop plans for dissemination of study results to the public.19

We also formed a steering committee consisting of physician, nursing, pharmacy, information technology, and administrative leadership representing primary care, inpatient care, and transitional care at both hospitals and Partners Healthcare. PFAC members took turns participating in quarterly steering committee meetings.

Evolution of the Intervention and Implementation

The intervention was iteratively refined during the course of the study in response to input from the PFAC, steering committee, and members of the intervention team; cases of adverse events and readmissions from patients despite being in the intervention arm; exit interviews of patients who had recently completed the intervention; and informal feedback from inpatient and outpatient clinicians. For example, we learned that the more complicated a patient’s conditions are, the sooner the clinical team wanted them to be seen after discharge. However, these patients were also less likely to feel well enough to keep that appointment. Therefore, the timing of follow-up of appointments needed to be a negotiation among the inpatient team, the patient, any caregivers, and the outpatient provider. PFAC members also emphasized that patients wanted one person to trust and to be the “point person” during a complicated transition such as hospital discharge.

At the same time, the intervention components evolved because of factors outside our control (eg, resource limitations). In keeping with the real-world nature of the research, the aim was for the intervention to be internally supported because incentives were theoretically more aligned with improvement of care transitions under the ACO model. By design, the PCORI contract only paid for limited parts of the intervention, such as a nurse practitioner to act as the discharge advocate at one hospital, overtime costs of inpatient pharmacists, and project manager time to facilitate inpatient-outpatient provider communication. (See Table 1 of Appendix 1 for details about the modifications to the intervention.)

Lastly, in keeping with PCORI’s methodology standards for studies of complex interventions,20 we strove to standardize the intervention by function across hospitals, units, and practices, while still allowing for local adaptation in the form. In other words, rather than specifying exactly how a task (eg, medication counseling) needed to be performed, the study design offered sites flexibility in how they implemented the task given their available personnel and institutional culture.

Intervention Fidelity

To determine the extent to which each patient in the intervention arm received each intervention component, a project manager unblinded to treatment arm reviewed the electronic medical record for documentation of each component implemented by providers (eg, inpatient pharmacists, outpatient nurses). Because each intervention component produced documentation, this provided an accurate assessment of intervention fidelity, ie, the extent to which the intervention was implemented as intended.

Outcome Assessment

Postdischarge Follow-up

Based on previous studies,2,21 a trained research assistant attempted to contact all study subjects 30 days (±5 days) after discharge and administered a questionnaire to identify any new or worsening symptoms since discharge, any healthcare use since discharge, and functional status in the previous week. Follow-up questions used branching logic to determine the relationship of any new or worsening symptoms to medications or other aspects of medical management. Research assistants followed up any positive responses with directed medical record review for objective findings, diagnoses, treatments, and responses. If patients could not be reached after five attempts, the research assistant instead conducted a thorough review of the outpatient medical record alone for provider reports of any new or worsening symptoms noted during follow-up within the 30-day postdischarge period. Research assistants also reviewed laboratory test results in all patients for evidence of postdischarge renal failure, elevated liver function tests, or new/worsening anemia.

Hospital Readmissions

We measured nonelective hospital readmissions within 30 days of discharge using a combination of administrative data for hospitalizations within the ACO network plus patient report during the 30-day phone call for all other readmissions.22

Adjudication of Outcomes

Adverse events and preventable adverse events: All cases of new or worsening symptoms or signs, along with all supporting documentation, were then presented to teams of two trained blinded physician adjudicators through application of methods established in previous studies.4,21 Each of the two adjudicators independently reviewed the information, along with the medical record, and completed a standardized form to confirm or deny the presence of any adverse events (ie, patient injury due to medical management) and to classify the type of event (eg, adverse drug event, hospital-acquired infection, procedural complication, diagnostic or management error), the severity and duration of the event, and whether the event was preventable or ameliorable. The two adjudicators then met to resolve any differences in their findings and come to consensus.

Preventable readmissions: If patients were readmitted to either study hospital, we conducted an evaluation, based on previous studies,23 to determine if and how the readmission could have been prevented including (a) a standardized patient and caregiver interview to identify possible problems with the transitions process and (b) an email questionnaire to the patient’s PCP and the inpatient teams who cared for the patient during the index admission and readmission regarding possible deficiencies with the transitions process. As with adverse event adjudications, two physician adjudicators worked independently to classify the preventability of the readmission and then met to come to consensus. Conflicts were resolved by a third adjudicator.

Analysis Plan

To evaluate the effects of the intervention on the primary outcome, the number of postdischarge adverse events per patient, we used multivariable Poisson regression, with study arm as the main predictor. A similar approach was used to evaluate the number of new or worsening postdischarge signs or symptoms and the number of preventable adverse events per patient. We used an intention-to-treat analysis: If a practice did not start the intervention when they were scheduled to, based on our randomization, we counted all patients in that practice admitted after that point as intervention patients. We adjusted for patient demographics, clinical characteristics, month, inpatient unit, and primary care practice as fixed effects. We clustered by PCP using general linear models. Intervention effects were expressed as both unadjusted and adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs). We also conducted a limited number of subgroup analyses, determined a priori, to determine whether the intervention was more effective in certain patient populations; we used interaction terms (intervention × subgroup) to determine the statistical significance of any effect modification.

To evaluate the effects of the intervention on nonelective readmissions and preventable readmissions, we used a similar approach, using multivariable logistic regression. Postdischarge functional status, adjusted for status prior to admission, was analyzed using multivariable linear regression and random effects by primary care practice. The general linear mixed model (GLIMMIX) procedure in the SAS 9.3 statistical package (SAS Institute) was used to carry out all analyses.

Power and Sample Size

We assumed a baseline rate of postdischarge adverse events of 0.30 per patient.21 We conservatively assumed an effect size of a change from 0.30 in the control group to 0.23 in the intervention group (a relative reduction of 22%, which was based on studies of preventability rates23 and close to the minimum clinically important difference). Based on prior studies,4,22 we assumed an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.01 with an average cluster size of seven patients per PCP. Assuming a 10% loss to follow-up rate and an alpha of 0.05, we targeted a sample size of 1,800 patients to achieve 80% power, with one-third of the patients in the usual care arm and two-thirds in the intervention arm.

RESULTS

We enrolled 18 PCMH primary care practices to participate in the study, including 8 from Hospital A (out of 13 approached), 8 from Hospital B (out of 11), and 2 from other ACO practices (out of 9) (plus two pilot practices). Reasons for not participating included not having dedicated personnel to play the role of the responsible outpatient clinician, undergoing recent turn-over in practice leadership, and not having enough patients admitted to the two hospitals. One practice only enrolled 5 patients in the study and withdrew from participation, which left 17 practices.

Study Patients

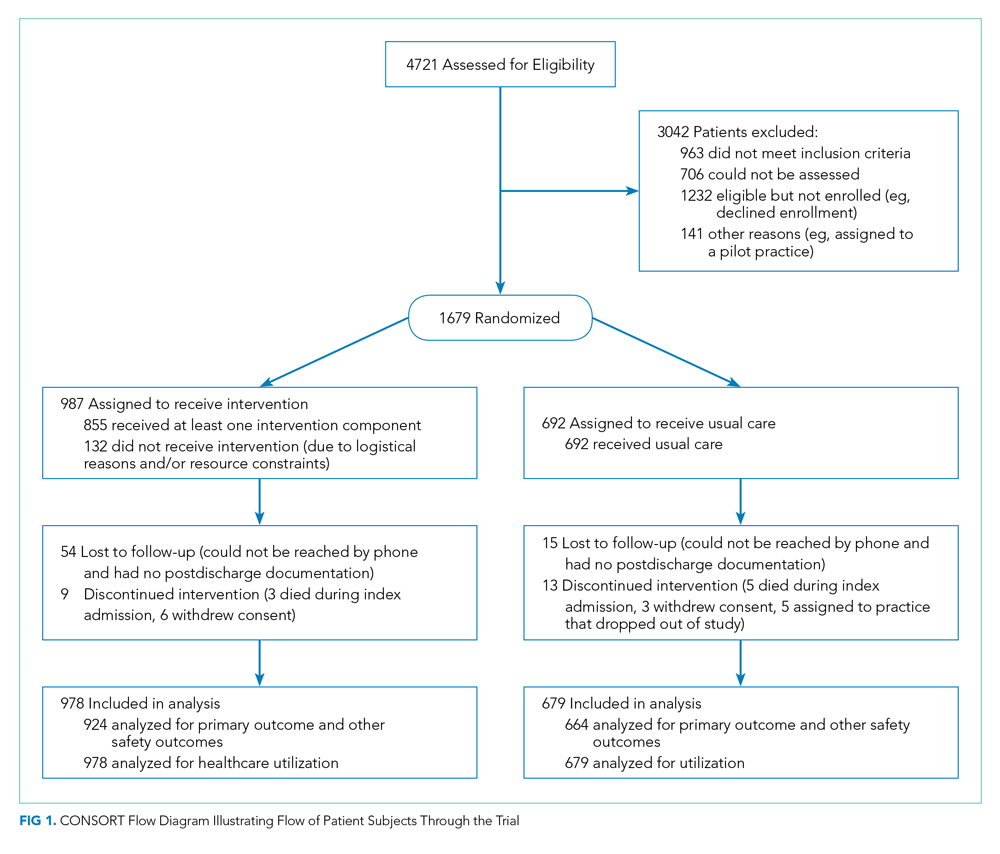

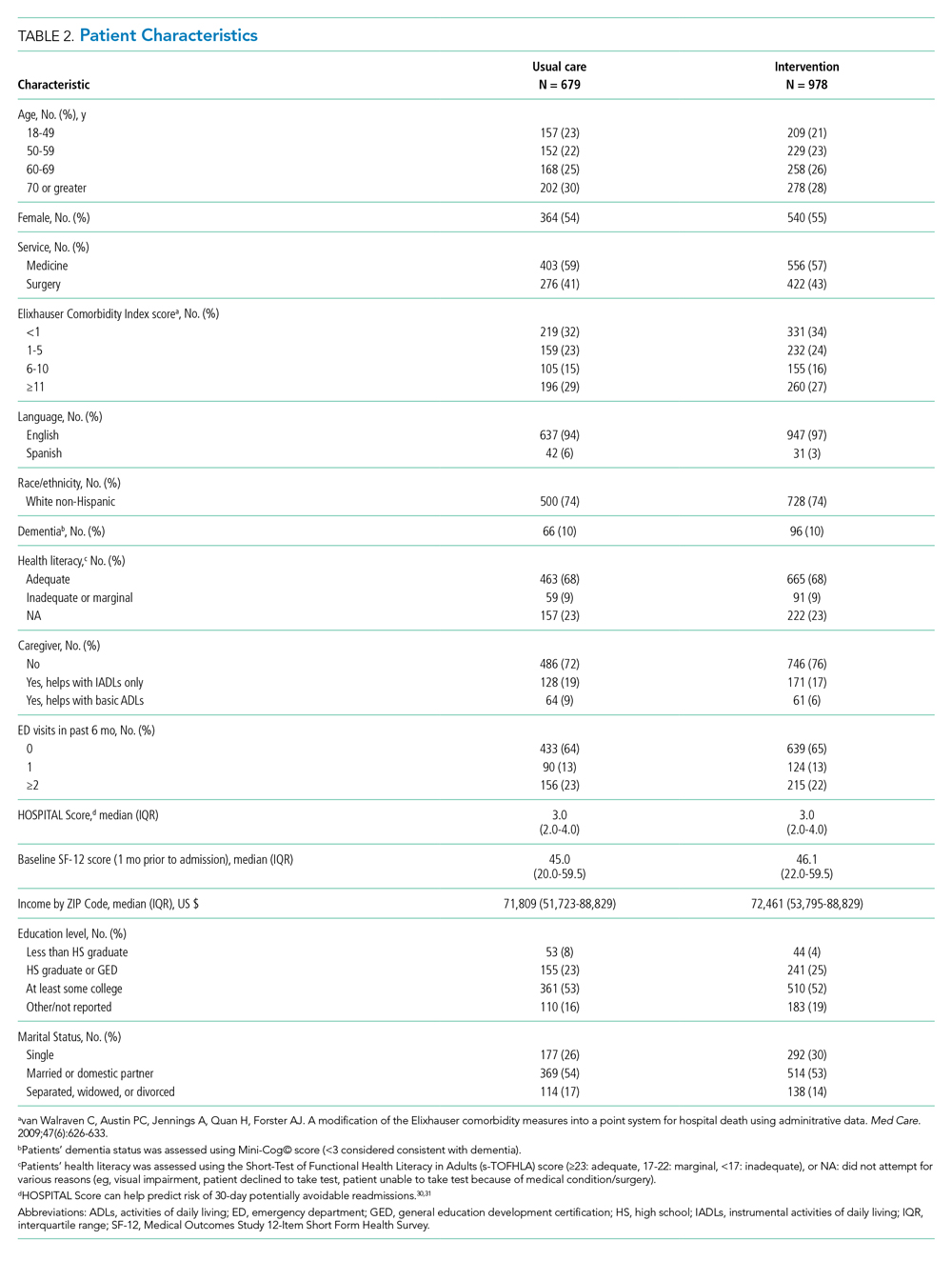

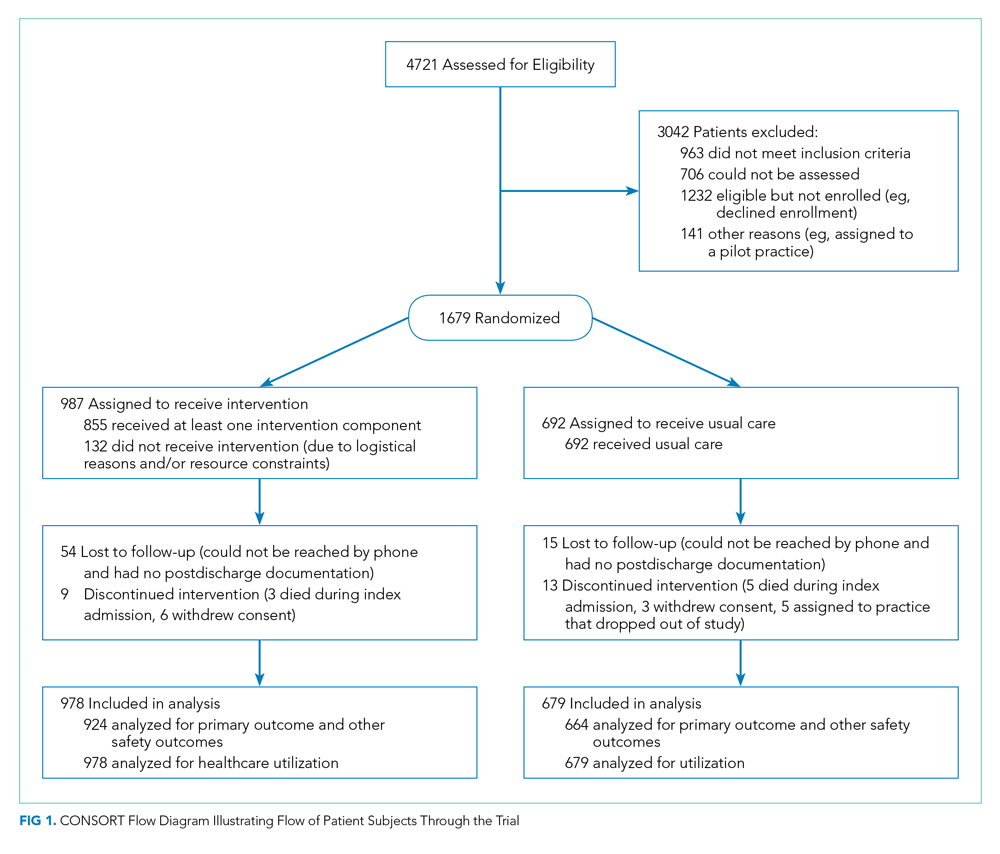

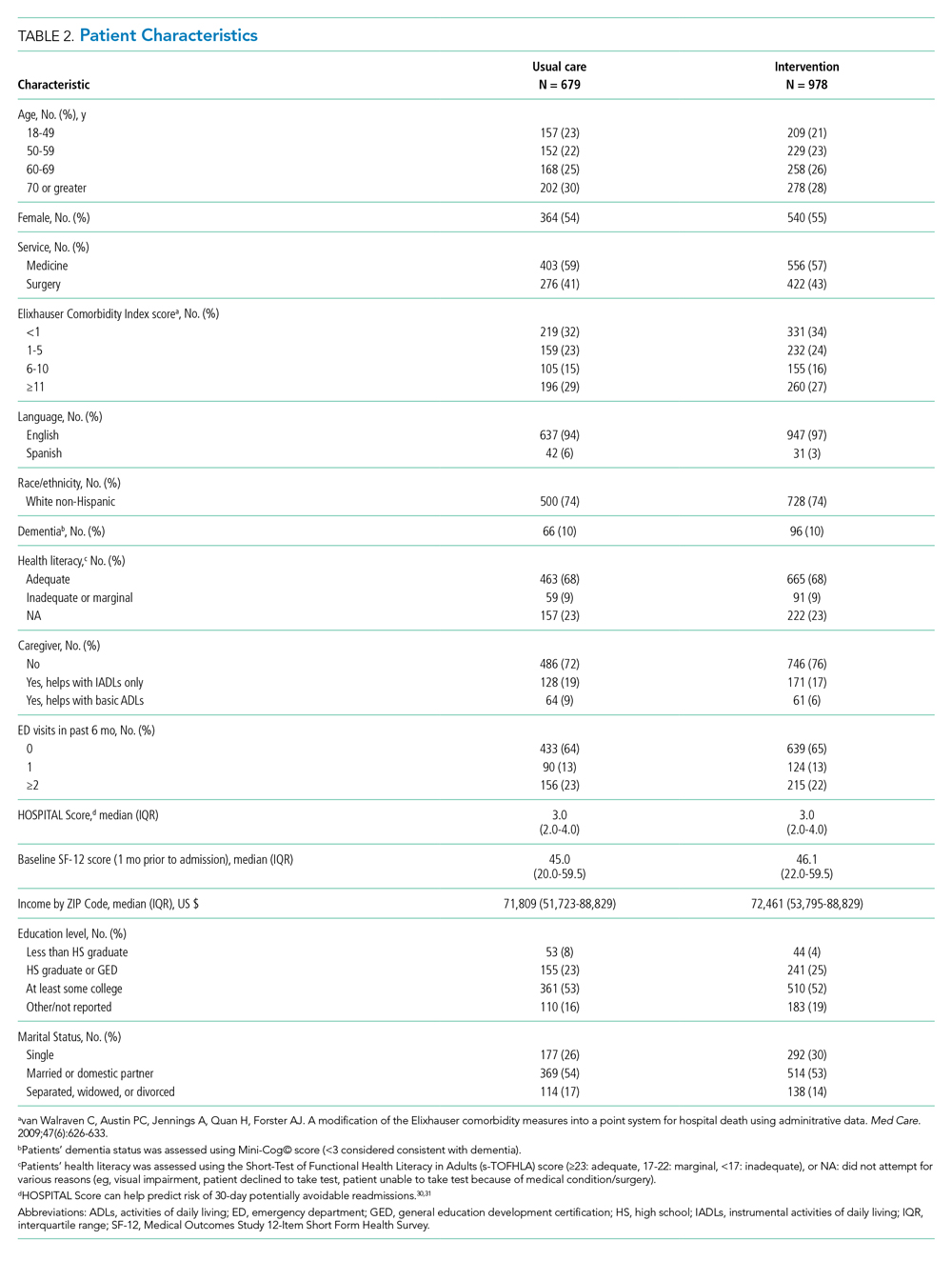

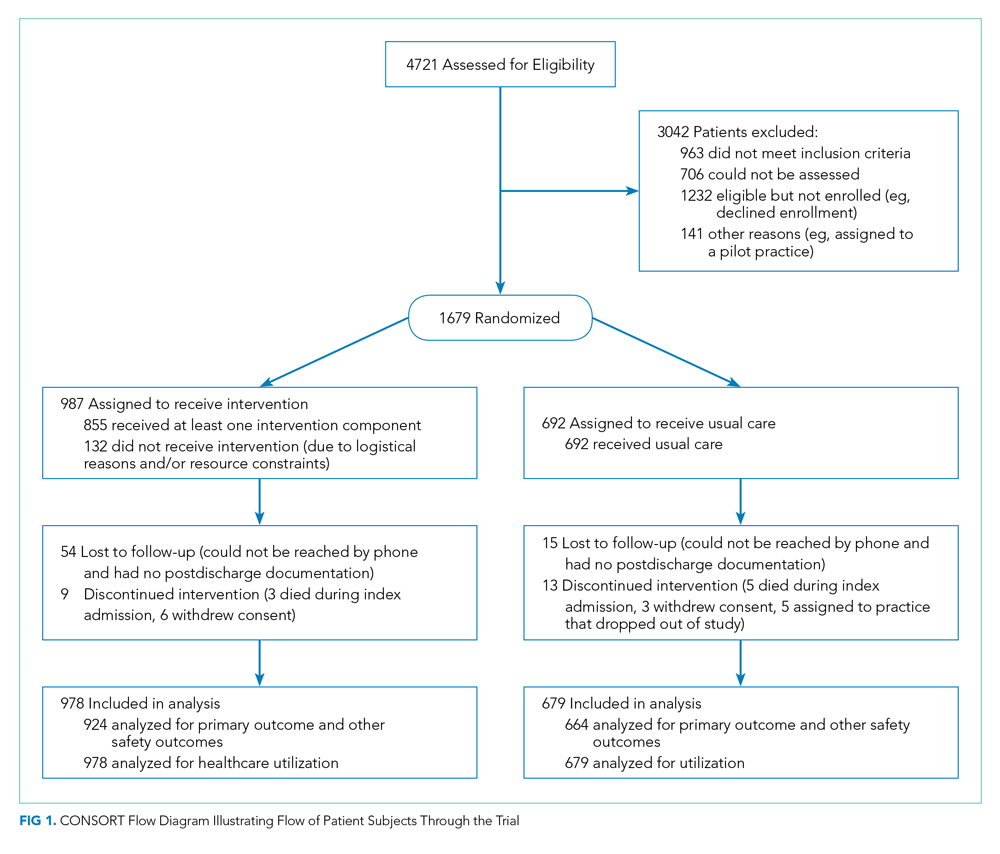

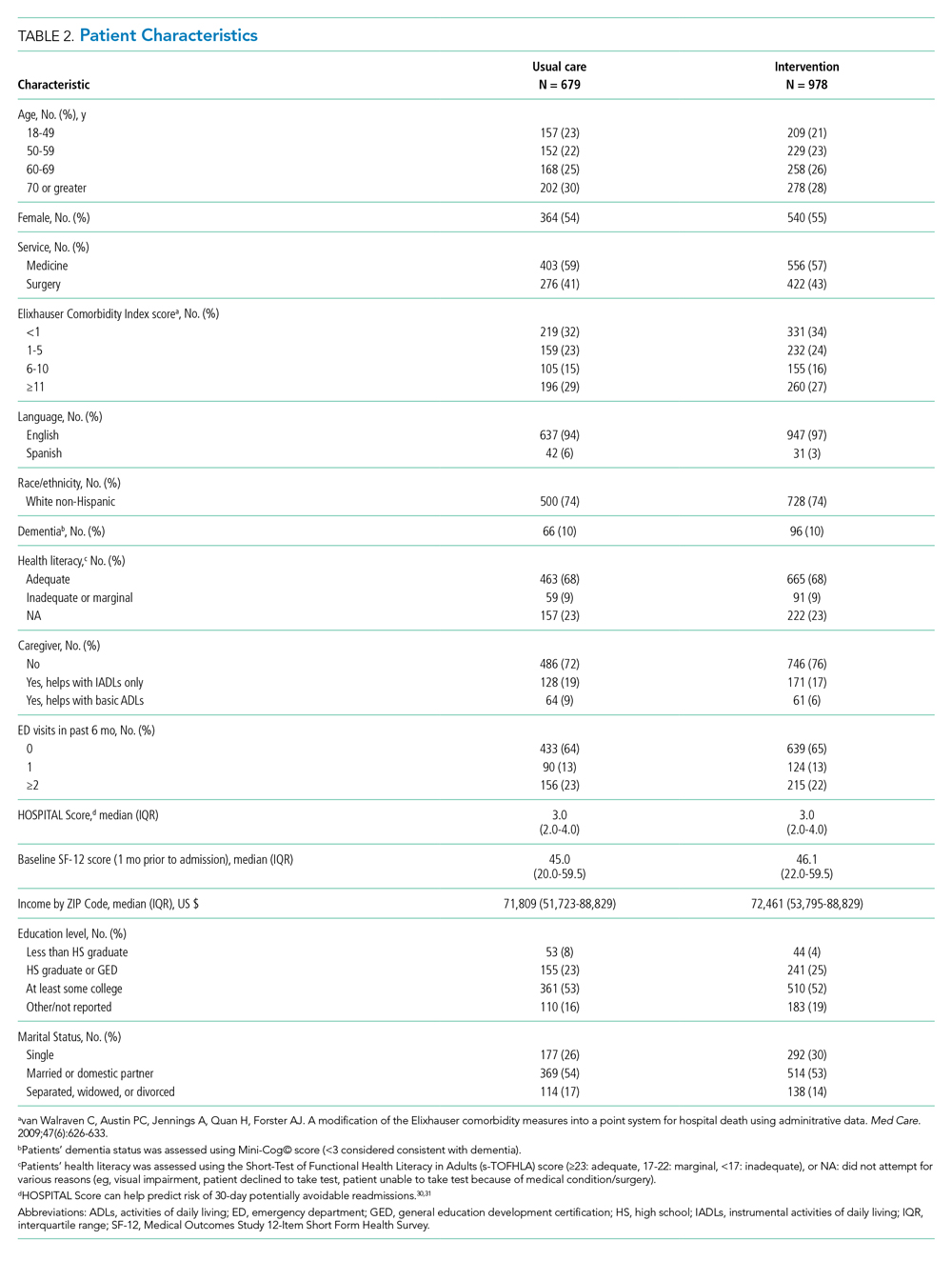

We enrolled 1,679 patients (Figure 1). Reasons for nonenrollment included being unable to complete the screen prior to discharge, not meeting inclusion criteria or meeting exclusion criteria, being assigned to a pilot practice, and declining informed written consent. The baseline characteristics of enrolled patients are presented in Table 2. Differences between the two study arms were small. About 47% of the cohort was not reachable by phone after five attempts for the 30-day phone call, but only 69 (4.1%) were truly lost to follow-up because they were unreachable by phone and had no documentation in the electronic medical record in the 30-days after discharge.

Intervention Fidelity

The majority of patients did not receive most intervention components, even those components that were supposed to be delivered to all intervention patients (Table 3). A minority of patients were referred to visiting nurse services and to the home pharmacy program. However, 855 patients (87%) in the intervention arm received at least one intervention component.

Outcome Measures

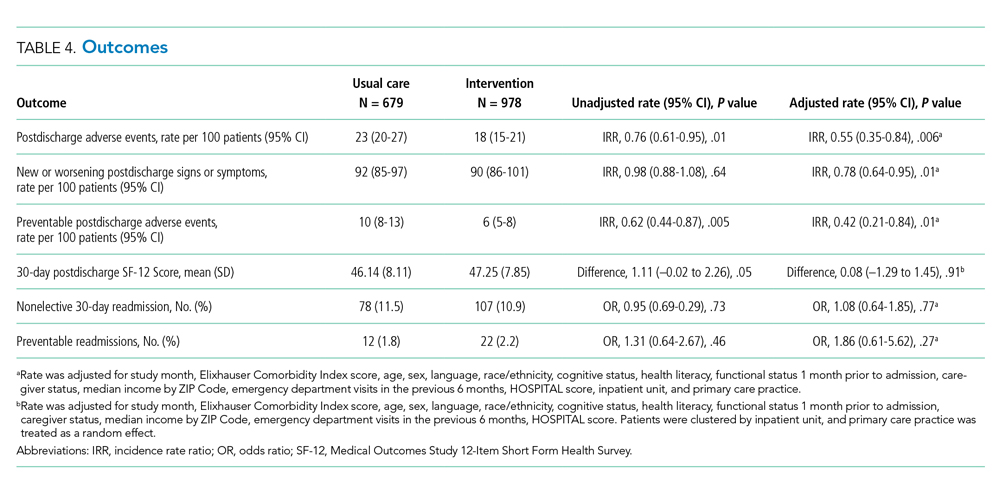

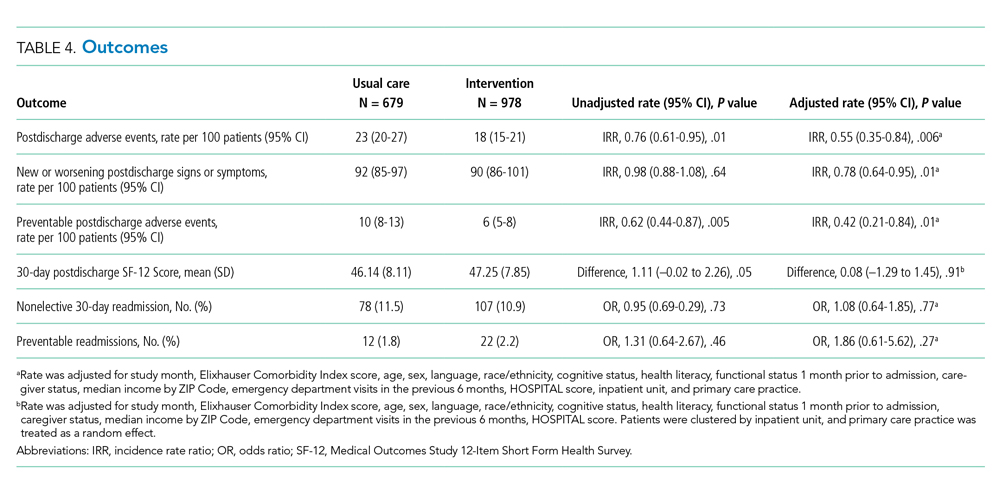

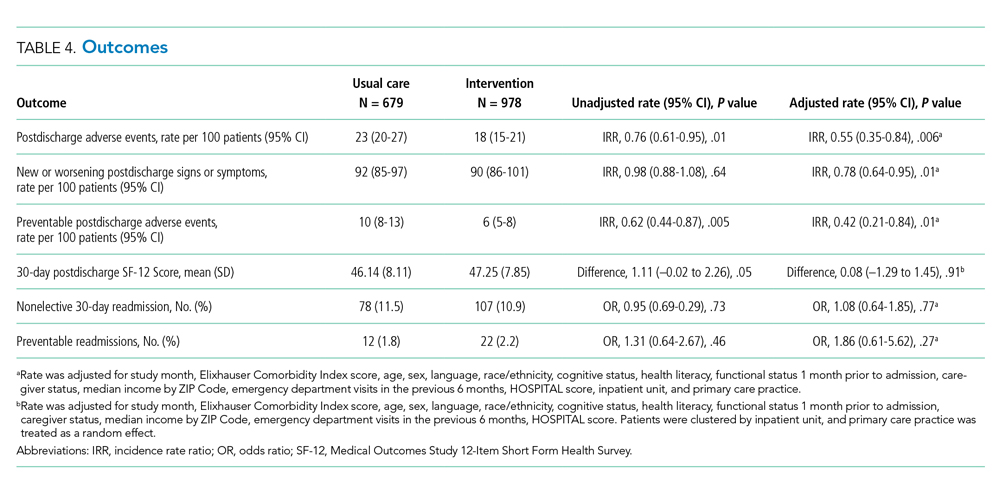

The intervention was associated with a statistically significant reduction in several of the outcomes of interest, including the primary outcome, number of postdischarge adverse events (45% reduction), and new or worsening postdischarge signs or symptoms (22% reduction), as well as preventable postdischarge adverse events (58% reduction) (Table 4). There was a nonsignificant difference in functional status. There was no significant effect on total nonelective or on preventable readmission rates. When analyzed by type of adverse event, the intervention was associated with a reduction in adverse drug events and in procedural complications (Table 2 of Appendix 1). Of note, there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients with at least one adverse event whether the outcome was determined by phone call and medical record review (49%) or medical record review alone (51%) (P = .48).

In subgroup analyses, there was no evidence of effect modification by service, hospital, patient age, readmission risk, health literacy, or comorbidity score (Table 3 of Appendix 1). Table 4 of Appendix 1 provides examples of postdischarge adverse events seen in the usual care arm that might have been prevented in the intervention.

DISCUSSION

This intervention was associated with a reduction in postdischarge adverse events. The relative improvement in each outcome aligned with the hypothesized sensitivity to change: the smallest improvement was seen in new or worsening signs or symptoms, followed by postdischarge adverse events and then by preventable postdischarge adverse events. The intervention was not associated with a difference in readmissions. The lack of effect on hospital readmissions may have been caused by the low proportion of readmissions that are preventable, as well as low intervention fidelity and lack of resources to implement facets such as postdischarge coaching, an evidence-based intervention that was never adopted.16,23 One lesson of this study is that it may be easier to reduce postdischarge injury (still an important outcome) than readmissions.

Putting this study in context, we should note that the literature on interventions to improve care transitions is mixed.18 While there are several reports of successful interventions, there are many reports of unsuccessful ones, often using similar components. Success is often the result of adequate resources and attention to myriad details regarding implementation.24 The intervention in our study likely contributed to improvements in patient and caregiver engagement in the hospital, enhancements of communication between inpatient and outpatient clinicians, and implementation of pharmacist-led interventions to improve medication safety. Regarding the latter, several prior studies have shown the benefits of pharmacist interventions in decreasing postdischarge adverse drug events.4,25,26 Therefore, even an intervention with incomplete intervention fidelity can reduce postdischarge adverse events, especially because adverse drug events make up the majority of adverse events.1,2,21

Perhaps the biggest lesson we learned was regarding the limitations of the hospital-led ACO model to incentivize sufficient up-front investments in transitional care interventions. By design, we chose a real-world approach in which interventions were integrated with existing ACO efforts, which were paid for internally by the institution. As a result, many of the interventions had to be scaled back because of resource constraints. The ACO model theoretically incentivizes more integrated care, but this may not always be true in practice. Emerging evidence suggests that physician group–led ACOs are associated with lower costs and use compared with hospital-led ACOs, likely because of more aligned incentives in physician group–led ACOs to reduce use of inpatient care.27,28

An unresolved question is whether the ideal implementation approach is to protect the time of existing clinical personnel to carry out transitional care tasks or to hire external personnel to do these tasks. We purposely spread the intervention over several clinician types to minimize the additional burden on any one of them, minimize additional costs, and play to each clinician’s expertise, but in retrospect, this may not have been the right approach. By providing additional personnel with dedicated time, interest, and training in care transitions, the intervention may be delivered with higher quantitative and qualitative fidelity, and it could create a single point of contact for patients, which was considered highly desirable by our PFAC.

This study has several limitations. A large proportion of patients (44%) were unavailable for postdischarge phone calls. However, we were able to perform medical record review for worsening signs (eg, lab abnormalities) and symptoms (as reported by patients’ providers) in the postdischarge period and adjudicate them for adverse events for all but 69 of these patients. Because all these patients had ACO-affiliated PCPs, we would expect most of their utilization to have been within the system and, therefore, to be present in the medical record. The proportion of patients with at least one adverse event did not vary by the method of follow-up, which suggests that this issue is an unlikely source of bias. Assessment of readmission was imperfect because we do not have statewide or national data. However, our combination of administrative data for Partners readmissions plus self-report for non-Partners readmission has been shown to be fairly complete in previous studies.29 Adjudicators could not be fully blinded to intervention status due to the lack of blinding of admission date. We did not calculate a kappa value for interrater reliability of individual assessments of adverse events; rather, coming to consensus among the two adjudicators was part of the process. In only a handful of cases was a third adjudicator required. Lastly, this study was conducted at two academic medical centers and their affiliated primary care clinics, which potentially limits generalizability; however, the results are likely generalizable to other ACOs that include major academic medical centers.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, in this real-world clinical trial, we designed, implemented, and iteratively refined a multifaceted intervention to improve care transitions within a hospital-based academic ACO. Evolution of the intervention components was the result of stakeholder input, experience with the intervention, and ACO resource constraints. The intervention reduced postdischarge adverse events. However, across the ACO network, intervention fidelity was low, and this may have contributed to the lack of effect on readmission rates. ACOs that implement interventions without hiring new personnel or protecting the time of existing personnel to conduct transitional tasks are likely to face the same challenges of low fidelity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the many people who worked on designing, implementing, and evaluating this intervention, including but not limited to: Natasha Isaac, Hilary Heyison, Jacqueline Minahan, Molly O’Reilly, Michelle Potter, Nailah Khoory, Maureen Fagan, David Bates, Laura Carr, Joseph Frolkis, Eric Weil, Jacqueline Somerville, Stephanie Ahmed, Marcy Bergeron, Jessica Smith, and Jane Millett. We would also like to thank the members of our Patient-Family Advisory Council: Maureen Fagan, Karen Spikes, Margie Hodges, Win Hodges, Aureldon Henderson, Dena Salzberg, and Kay Bander.

1. Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345-349.

2. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007

3. Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(7):533-536. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-141-7-200410050-00009

4. Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC, et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):565-571. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.5.565

5. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa0803563

6. Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2012. Updated February 11, 2020. Accessed July 15, 2012. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ACO/index.html?redirect=/ACO/

7. Bates DW, Bitton A. The future of health information technology in the patient-centered medical home. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(4):614-621. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0007

8. Bitton A, Martin C, Landon BE. A nationwide survey of patient centered medical home demonstration projects. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):584-592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1262-8

9. Brown C, Lilford R. Evaluating service delivery interventions to enhance patient safety. BMJ. 2008;337:a2764. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a2764

10. Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220-233. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003

11. Burke RE, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, Schnipper JL. Moving beyond readmission penalties: creating an ideal process to improve transitional care. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(2):102-109. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.1990

12. Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613-620. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.7.613

13. Gandara E, Ungar J, Lee J, Chan-Macrae M, O’Malley T, Schnipper JL. Discharge documentation of patients discharged to subacute facilities: a three-year quality improvement process across an integrated health care system. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(6):243-251. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36039-9

14. Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C, et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1414-1422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0687-9

15. Schnipper JL, Hamann C, Ndumele CD, et al. Effect of an electronic medication reconciliation application and process redesign on potential adverse drug events: a cluster-randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(8):771-780. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.51

16. Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822-1828. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822

17. Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178-187. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007

18. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520-528. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008

19. Schnipper J, Levine C. The important thing to do before leaving the hospital: many patients and families forget, which can lead to complications later. Next Avenue. October 22, 2019. Accessed September 10, 2020. https://www.nextavenue.org/before-leaving-hospital/

20. PCORI Methodology Standards: Standards for Studies of Complex Interventions. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; November 12, 2015. Updated: February 26, 2019. Accessed June 3, 2019. https://www.pcori.org/research-results/about-our-research/research-methodology/pcori-methodology-standards#Complex

21. Tsilimingras D, Schnipper J, Duke A, et al. Post-discharge adverse events among urban and rural patients of an urban community hospital: a prospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1164-1171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3260-3

22. Kripalani S, Roumie CL, Dalal AK, et al. Effect of a pharmacist intervention on clinically important medication errors after hospital discharge: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(1):1-10. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00003

23. Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and causes of readmissions in a national cohort of general medicine patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):484-493. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7863

24. Vasilevskis EE, Kripalani S, Ong MK, et al. Variability in implementation of interventions aimed at reducing readmissions among patients with heart failure: a survey of teaching hospitals. Acad Med. 2016;91(4):522-529. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000994

25. Gardella JE, Cardwell TB, Nnadi M. Improving medication safety with accurate preadmission medication lists and postdischarge education. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(10):452-458. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1553-7250(12)38060-4

26. Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, Schnipper JL. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):955-964. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.9.955

27. McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Chernew ME, Landon BE, Schwartz AL. Early performance of accountable care organizations in Medicare. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(24):2357-2366. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa1600142

28. McWilliams JM, Hatfield LA, Landon BE, Hamed P, Chernew ME. Medicare spending after 3 years of the Medicare Shared Savings Program. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(12):1139-1149. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa1803388

29. Hasan O, Meltzer DO, Shaykevich SA, et al. Hospital readmission in general medicine patients: a prediction model. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):211-219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1196-1

30. Donzé JD, Aujesky D, Williams D, Schnipper JL. Potentially avoidable 30-day hospital readmissions in medical patients: derivation and validation of a prediction model. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):632-638. https://doi.org/10.001/jamainternmed.2013.3023

31. Donzé JD, Williams MV, Robinson EJ, et al. International validity of the HOSPITAL score to predict 30-day potentially avoidable hospital readmissions. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):496-502. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8462

Transitions from the hospital to the ambulatory setting are high-risk periods for patients in terms of adverse events, poor clinical outcomes, and readmission. Processes of care during care transitions are suboptimal, including poor communication among inpatient providers, patients, and ambulatory providers1,2; suboptimal communication of postdischarge plans of care to patients and their ability to carry out these plans3; medication discrepancies and nonadherence after discharge4; and lack of timely follow-up with ambulatory providers.5 Healthcare organizations continue to struggle with the question of which interventions to implement and how best to implement them.

Interventions to improve care transitions typically focus on readmission rates, but some studies have focused on postdischarge adverse events, defined as injuries in the 30 days after discharge caused by medical management rather than underlying disease processes.2 These adverse events cause psychological distress, out-of-pocket expenses, decreases in functional status, and caregiver burden. An estimated 20% of hospitalized patients suffer a postdischarge adverse event.1,2 Approximately two-thirds of these may be preventable or ameliorable.

The advent of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), defined as “groups of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers who come together voluntarily to give coordinated high quality care to their patients,” creates an opportunity for improvements in patient safety during care transitions.6 Another opportunity has been the advent of Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH), consisting of patient-oriented, comprehensive, team-based primary care enhanced by health information technology and population-based disease management tools.7,8 In theory, a hospital-PCMH collaboration within an ACO can improve transitional interventions since optimal communication and collaboration are more likely when both inpatient and primary care providers (PCPs) share infrastructure and are similarly incentivized. The objectives of this study were to design and implement a collaborative hospital-PCMH care transitions intervention within an ACO and evaluate its effects.

METHODS

This study was a two-arm, single-blind (blinded outcomes assessor), stepped-wedge, multisite cluster-randomized clinical trial (NCT02130570) approved by the institutional review board of Partners HealthCare.

Study Design and Randomization

The study employed a “stepped-wedge” design, which is a cluster-randomized study design in which an intervention is sequentially rolled out to different groups at different, prespecified, randomly determined times.9 Each cluster (in this case, each primary care practice) served as its own control, while still allowing for adjustment for temporal trends. Originally, 18 practices participated, but one withdrew due to the low number of patients enrolled in the study, leaving 17 clusters and 16 sequences; see Figure 1 of Appendix 1 for a full description of the sample size and timeline for each cluster. Practices were not aware of this timeline until after recruitment.

Study Setting and Participants

Conducted within a large Pioneer ACO in Boston and funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), the Partners-PCORI Transitions Study was designed as a “real-world” quality improvement project. Potential participants were adult patients who were admitted to medical and surgical services of two large academic hospitals (Hospital A and Hospital B) affiliated with an ACO, who were likely to be discharged back to the community, and whose PCP belonged to a primary care practice that was affiliated with the ACO, agreed to participate, and were designated PCMHs or on their way to being designated by meeting certain criteria: electronic health record, patient portal, team-based care, practice redesign, care management, and identification of high-risk patients. See Study Protocol (Appendix 2) for detailed patient and primary care practice inclusion criteria.

Patient Enrollment

Study staff screened participants from a daily automated list of patients admitted the day before, using medical records to determine eligibility, which was then confirmed by the patient’s nurse. Exclusion criteria included likely discharge to a location other than home, being in police custody, lack of a telephone, being homeless, previous enrollment in the study, and being unable to communicate in English or Spanish. Allocation to study arm was concealed until the patient or proxy provided informed written consent. The research assistant administered questionnaires to all study subjects to assess potential confounders and functional status 1 month prior to admission (

Intervention

The intervention was based on a conceptual model of an ideal discharge11 that we developed based on work by Naylor et al,12 work by Coleman and Berenson,3 best practices in medication reconciliation and information transfer according to our own research,13-15 the best examples of interventions to improve the discharge process,12,16,17 and a systematic review of discharge interventions.18 Some of the factors necessary for an ideal care transition include complete, organized, and timely documentation of the patient’s hospital course and postdischarge plan; effective discharge planning; coordination of care among the patient’s providers; methods to ensure medication safety; advanced care planning in appropriate patients; and education and “coaching” of patients and their caregivers so they learn how to manage their conditions. The final multifaceted intervention addressed each component of the ideal discharge and included inpatient and outpatient components (Table 1 and Table 1 of Appendix 1).

Patient and Public Involvement in Research

As with all PCORI-funded studies, this study involved a patient-family advisory council (PFAC). Our PFAC included six recently hospitalized patients or caregivers of recently hospitalized patients. The PFAC participated in monthly meetings throughout the study period. They helped inform the research questions, including confirmation that the endpoints were patient centered, and provided valuable input for the design of the intervention and the patient-facing components of the data collection instruments. They also interviewed several patient participants in the study regarding their experiences with the intervention. Lastly, they helped develop plans for dissemination of study results to the public.19

We also formed a steering committee consisting of physician, nursing, pharmacy, information technology, and administrative leadership representing primary care, inpatient care, and transitional care at both hospitals and Partners Healthcare. PFAC members took turns participating in quarterly steering committee meetings.

Evolution of the Intervention and Implementation

The intervention was iteratively refined during the course of the study in response to input from the PFAC, steering committee, and members of the intervention team; cases of adverse events and readmissions from patients despite being in the intervention arm; exit interviews of patients who had recently completed the intervention; and informal feedback from inpatient and outpatient clinicians. For example, we learned that the more complicated a patient’s conditions are, the sooner the clinical team wanted them to be seen after discharge. However, these patients were also less likely to feel well enough to keep that appointment. Therefore, the timing of follow-up of appointments needed to be a negotiation among the inpatient team, the patient, any caregivers, and the outpatient provider. PFAC members also emphasized that patients wanted one person to trust and to be the “point person” during a complicated transition such as hospital discharge.

At the same time, the intervention components evolved because of factors outside our control (eg, resource limitations). In keeping with the real-world nature of the research, the aim was for the intervention to be internally supported because incentives were theoretically more aligned with improvement of care transitions under the ACO model. By design, the PCORI contract only paid for limited parts of the intervention, such as a nurse practitioner to act as the discharge advocate at one hospital, overtime costs of inpatient pharmacists, and project manager time to facilitate inpatient-outpatient provider communication. (See Table 1 of Appendix 1 for details about the modifications to the intervention.)

Lastly, in keeping with PCORI’s methodology standards for studies of complex interventions,20 we strove to standardize the intervention by function across hospitals, units, and practices, while still allowing for local adaptation in the form. In other words, rather than specifying exactly how a task (eg, medication counseling) needed to be performed, the study design offered sites flexibility in how they implemented the task given their available personnel and institutional culture.

Intervention Fidelity

To determine the extent to which each patient in the intervention arm received each intervention component, a project manager unblinded to treatment arm reviewed the electronic medical record for documentation of each component implemented by providers (eg, inpatient pharmacists, outpatient nurses). Because each intervention component produced documentation, this provided an accurate assessment of intervention fidelity, ie, the extent to which the intervention was implemented as intended.

Outcome Assessment

Postdischarge Follow-up

Based on previous studies,2,21 a trained research assistant attempted to contact all study subjects 30 days (±5 days) after discharge and administered a questionnaire to identify any new or worsening symptoms since discharge, any healthcare use since discharge, and functional status in the previous week. Follow-up questions used branching logic to determine the relationship of any new or worsening symptoms to medications or other aspects of medical management. Research assistants followed up any positive responses with directed medical record review for objective findings, diagnoses, treatments, and responses. If patients could not be reached after five attempts, the research assistant instead conducted a thorough review of the outpatient medical record alone for provider reports of any new or worsening symptoms noted during follow-up within the 30-day postdischarge period. Research assistants also reviewed laboratory test results in all patients for evidence of postdischarge renal failure, elevated liver function tests, or new/worsening anemia.

Hospital Readmissions

We measured nonelective hospital readmissions within 30 days of discharge using a combination of administrative data for hospitalizations within the ACO network plus patient report during the 30-day phone call for all other readmissions.22

Adjudication of Outcomes

Adverse events and preventable adverse events: All cases of new or worsening symptoms or signs, along with all supporting documentation, were then presented to teams of two trained blinded physician adjudicators through application of methods established in previous studies.4,21 Each of the two adjudicators independently reviewed the information, along with the medical record, and completed a standardized form to confirm or deny the presence of any adverse events (ie, patient injury due to medical management) and to classify the type of event (eg, adverse drug event, hospital-acquired infection, procedural complication, diagnostic or management error), the severity and duration of the event, and whether the event was preventable or ameliorable. The two adjudicators then met to resolve any differences in their findings and come to consensus.

Preventable readmissions: If patients were readmitted to either study hospital, we conducted an evaluation, based on previous studies,23 to determine if and how the readmission could have been prevented including (a) a standardized patient and caregiver interview to identify possible problems with the transitions process and (b) an email questionnaire to the patient’s PCP and the inpatient teams who cared for the patient during the index admission and readmission regarding possible deficiencies with the transitions process. As with adverse event adjudications, two physician adjudicators worked independently to classify the preventability of the readmission and then met to come to consensus. Conflicts were resolved by a third adjudicator.

Analysis Plan

To evaluate the effects of the intervention on the primary outcome, the number of postdischarge adverse events per patient, we used multivariable Poisson regression, with study arm as the main predictor. A similar approach was used to evaluate the number of new or worsening postdischarge signs or symptoms and the number of preventable adverse events per patient. We used an intention-to-treat analysis: If a practice did not start the intervention when they were scheduled to, based on our randomization, we counted all patients in that practice admitted after that point as intervention patients. We adjusted for patient demographics, clinical characteristics, month, inpatient unit, and primary care practice as fixed effects. We clustered by PCP using general linear models. Intervention effects were expressed as both unadjusted and adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs). We also conducted a limited number of subgroup analyses, determined a priori, to determine whether the intervention was more effective in certain patient populations; we used interaction terms (intervention × subgroup) to determine the statistical significance of any effect modification.

To evaluate the effects of the intervention on nonelective readmissions and preventable readmissions, we used a similar approach, using multivariable logistic regression. Postdischarge functional status, adjusted for status prior to admission, was analyzed using multivariable linear regression and random effects by primary care practice. The general linear mixed model (GLIMMIX) procedure in the SAS 9.3 statistical package (SAS Institute) was used to carry out all analyses.

Power and Sample Size

We assumed a baseline rate of postdischarge adverse events of 0.30 per patient.21 We conservatively assumed an effect size of a change from 0.30 in the control group to 0.23 in the intervention group (a relative reduction of 22%, which was based on studies of preventability rates23 and close to the minimum clinically important difference). Based on prior studies,4,22 we assumed an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.01 with an average cluster size of seven patients per PCP. Assuming a 10% loss to follow-up rate and an alpha of 0.05, we targeted a sample size of 1,800 patients to achieve 80% power, with one-third of the patients in the usual care arm and two-thirds in the intervention arm.

RESULTS

We enrolled 18 PCMH primary care practices to participate in the study, including 8 from Hospital A (out of 13 approached), 8 from Hospital B (out of 11), and 2 from other ACO practices (out of 9) (plus two pilot practices). Reasons for not participating included not having dedicated personnel to play the role of the responsible outpatient clinician, undergoing recent turn-over in practice leadership, and not having enough patients admitted to the two hospitals. One practice only enrolled 5 patients in the study and withdrew from participation, which left 17 practices.

Study Patients

We enrolled 1,679 patients (Figure 1). Reasons for nonenrollment included being unable to complete the screen prior to discharge, not meeting inclusion criteria or meeting exclusion criteria, being assigned to a pilot practice, and declining informed written consent. The baseline characteristics of enrolled patients are presented in Table 2. Differences between the two study arms were small. About 47% of the cohort was not reachable by phone after five attempts for the 30-day phone call, but only 69 (4.1%) were truly lost to follow-up because they were unreachable by phone and had no documentation in the electronic medical record in the 30-days after discharge.

Intervention Fidelity

The majority of patients did not receive most intervention components, even those components that were supposed to be delivered to all intervention patients (Table 3). A minority of patients were referred to visiting nurse services and to the home pharmacy program. However, 855 patients (87%) in the intervention arm received at least one intervention component.

Outcome Measures

The intervention was associated with a statistically significant reduction in several of the outcomes of interest, including the primary outcome, number of postdischarge adverse events (45% reduction), and new or worsening postdischarge signs or symptoms (22% reduction), as well as preventable postdischarge adverse events (58% reduction) (Table 4). There was a nonsignificant difference in functional status. There was no significant effect on total nonelective or on preventable readmission rates. When analyzed by type of adverse event, the intervention was associated with a reduction in adverse drug events and in procedural complications (Table 2 of Appendix 1). Of note, there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients with at least one adverse event whether the outcome was determined by phone call and medical record review (49%) or medical record review alone (51%) (P = .48).

In subgroup analyses, there was no evidence of effect modification by service, hospital, patient age, readmission risk, health literacy, or comorbidity score (Table 3 of Appendix 1). Table 4 of Appendix 1 provides examples of postdischarge adverse events seen in the usual care arm that might have been prevented in the intervention.

DISCUSSION

This intervention was associated with a reduction in postdischarge adverse events. The relative improvement in each outcome aligned with the hypothesized sensitivity to change: the smallest improvement was seen in new or worsening signs or symptoms, followed by postdischarge adverse events and then by preventable postdischarge adverse events. The intervention was not associated with a difference in readmissions. The lack of effect on hospital readmissions may have been caused by the low proportion of readmissions that are preventable, as well as low intervention fidelity and lack of resources to implement facets such as postdischarge coaching, an evidence-based intervention that was never adopted.16,23 One lesson of this study is that it may be easier to reduce postdischarge injury (still an important outcome) than readmissions.

Putting this study in context, we should note that the literature on interventions to improve care transitions is mixed.18 While there are several reports of successful interventions, there are many reports of unsuccessful ones, often using similar components. Success is often the result of adequate resources and attention to myriad details regarding implementation.24 The intervention in our study likely contributed to improvements in patient and caregiver engagement in the hospital, enhancements of communication between inpatient and outpatient clinicians, and implementation of pharmacist-led interventions to improve medication safety. Regarding the latter, several prior studies have shown the benefits of pharmacist interventions in decreasing postdischarge adverse drug events.4,25,26 Therefore, even an intervention with incomplete intervention fidelity can reduce postdischarge adverse events, especially because adverse drug events make up the majority of adverse events.1,2,21

Perhaps the biggest lesson we learned was regarding the limitations of the hospital-led ACO model to incentivize sufficient up-front investments in transitional care interventions. By design, we chose a real-world approach in which interventions were integrated with existing ACO efforts, which were paid for internally by the institution. As a result, many of the interventions had to be scaled back because of resource constraints. The ACO model theoretically incentivizes more integrated care, but this may not always be true in practice. Emerging evidence suggests that physician group–led ACOs are associated with lower costs and use compared with hospital-led ACOs, likely because of more aligned incentives in physician group–led ACOs to reduce use of inpatient care.27,28

An unresolved question is whether the ideal implementation approach is to protect the time of existing clinical personnel to carry out transitional care tasks or to hire external personnel to do these tasks. We purposely spread the intervention over several clinician types to minimize the additional burden on any one of them, minimize additional costs, and play to each clinician’s expertise, but in retrospect, this may not have been the right approach. By providing additional personnel with dedicated time, interest, and training in care transitions, the intervention may be delivered with higher quantitative and qualitative fidelity, and it could create a single point of contact for patients, which was considered highly desirable by our PFAC.

This study has several limitations. A large proportion of patients (44%) were unavailable for postdischarge phone calls. However, we were able to perform medical record review for worsening signs (eg, lab abnormalities) and symptoms (as reported by patients’ providers) in the postdischarge period and adjudicate them for adverse events for all but 69 of these patients. Because all these patients had ACO-affiliated PCPs, we would expect most of their utilization to have been within the system and, therefore, to be present in the medical record. The proportion of patients with at least one adverse event did not vary by the method of follow-up, which suggests that this issue is an unlikely source of bias. Assessment of readmission was imperfect because we do not have statewide or national data. However, our combination of administrative data for Partners readmissions plus self-report for non-Partners readmission has been shown to be fairly complete in previous studies.29 Adjudicators could not be fully blinded to intervention status due to the lack of blinding of admission date. We did not calculate a kappa value for interrater reliability of individual assessments of adverse events; rather, coming to consensus among the two adjudicators was part of the process. In only a handful of cases was a third adjudicator required. Lastly, this study was conducted at two academic medical centers and their affiliated primary care clinics, which potentially limits generalizability; however, the results are likely generalizable to other ACOs that include major academic medical centers.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, in this real-world clinical trial, we designed, implemented, and iteratively refined a multifaceted intervention to improve care transitions within a hospital-based academic ACO. Evolution of the intervention components was the result of stakeholder input, experience with the intervention, and ACO resource constraints. The intervention reduced postdischarge adverse events. However, across the ACO network, intervention fidelity was low, and this may have contributed to the lack of effect on readmission rates. ACOs that implement interventions without hiring new personnel or protecting the time of existing personnel to conduct transitional tasks are likely to face the same challenges of low fidelity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the many people who worked on designing, implementing, and evaluating this intervention, including but not limited to: Natasha Isaac, Hilary Heyison, Jacqueline Minahan, Molly O’Reilly, Michelle Potter, Nailah Khoory, Maureen Fagan, David Bates, Laura Carr, Joseph Frolkis, Eric Weil, Jacqueline Somerville, Stephanie Ahmed, Marcy Bergeron, Jessica Smith, and Jane Millett. We would also like to thank the members of our Patient-Family Advisory Council: Maureen Fagan, Karen Spikes, Margie Hodges, Win Hodges, Aureldon Henderson, Dena Salzberg, and Kay Bander.

Transitions from the hospital to the ambulatory setting are high-risk periods for patients in terms of adverse events, poor clinical outcomes, and readmission. Processes of care during care transitions are suboptimal, including poor communication among inpatient providers, patients, and ambulatory providers1,2; suboptimal communication of postdischarge plans of care to patients and their ability to carry out these plans3; medication discrepancies and nonadherence after discharge4; and lack of timely follow-up with ambulatory providers.5 Healthcare organizations continue to struggle with the question of which interventions to implement and how best to implement them.

Interventions to improve care transitions typically focus on readmission rates, but some studies have focused on postdischarge adverse events, defined as injuries in the 30 days after discharge caused by medical management rather than underlying disease processes.2 These adverse events cause psychological distress, out-of-pocket expenses, decreases in functional status, and caregiver burden. An estimated 20% of hospitalized patients suffer a postdischarge adverse event.1,2 Approximately two-thirds of these may be preventable or ameliorable.

The advent of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), defined as “groups of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers who come together voluntarily to give coordinated high quality care to their patients,” creates an opportunity for improvements in patient safety during care transitions.6 Another opportunity has been the advent of Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH), consisting of patient-oriented, comprehensive, team-based primary care enhanced by health information technology and population-based disease management tools.7,8 In theory, a hospital-PCMH collaboration within an ACO can improve transitional interventions since optimal communication and collaboration are more likely when both inpatient and primary care providers (PCPs) share infrastructure and are similarly incentivized. The objectives of this study were to design and implement a collaborative hospital-PCMH care transitions intervention within an ACO and evaluate its effects.

METHODS

This study was a two-arm, single-blind (blinded outcomes assessor), stepped-wedge, multisite cluster-randomized clinical trial (NCT02130570) approved by the institutional review board of Partners HealthCare.

Study Design and Randomization

The study employed a “stepped-wedge” design, which is a cluster-randomized study design in which an intervention is sequentially rolled out to different groups at different, prespecified, randomly determined times.9 Each cluster (in this case, each primary care practice) served as its own control, while still allowing for adjustment for temporal trends. Originally, 18 practices participated, but one withdrew due to the low number of patients enrolled in the study, leaving 17 clusters and 16 sequences; see Figure 1 of Appendix 1 for a full description of the sample size and timeline for each cluster. Practices were not aware of this timeline until after recruitment.

Study Setting and Participants

Conducted within a large Pioneer ACO in Boston and funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), the Partners-PCORI Transitions Study was designed as a “real-world” quality improvement project. Potential participants were adult patients who were admitted to medical and surgical services of two large academic hospitals (Hospital A and Hospital B) affiliated with an ACO, who were likely to be discharged back to the community, and whose PCP belonged to a primary care practice that was affiliated with the ACO, agreed to participate, and were designated PCMHs or on their way to being designated by meeting certain criteria: electronic health record, patient portal, team-based care, practice redesign, care management, and identification of high-risk patients. See Study Protocol (Appendix 2) for detailed patient and primary care practice inclusion criteria.

Patient Enrollment

Study staff screened participants from a daily automated list of patients admitted the day before, using medical records to determine eligibility, which was then confirmed by the patient’s nurse. Exclusion criteria included likely discharge to a location other than home, being in police custody, lack of a telephone, being homeless, previous enrollment in the study, and being unable to communicate in English or Spanish. Allocation to study arm was concealed until the patient or proxy provided informed written consent. The research assistant administered questionnaires to all study subjects to assess potential confounders and functional status 1 month prior to admission (

Intervention

The intervention was based on a conceptual model of an ideal discharge11 that we developed based on work by Naylor et al,12 work by Coleman and Berenson,3 best practices in medication reconciliation and information transfer according to our own research,13-15 the best examples of interventions to improve the discharge process,12,16,17 and a systematic review of discharge interventions.18 Some of the factors necessary for an ideal care transition include complete, organized, and timely documentation of the patient’s hospital course and postdischarge plan; effective discharge planning; coordination of care among the patient’s providers; methods to ensure medication safety; advanced care planning in appropriate patients; and education and “coaching” of patients and their caregivers so they learn how to manage their conditions. The final multifaceted intervention addressed each component of the ideal discharge and included inpatient and outpatient components (Table 1 and Table 1 of Appendix 1).

Patient and Public Involvement in Research

As with all PCORI-funded studies, this study involved a patient-family advisory council (PFAC). Our PFAC included six recently hospitalized patients or caregivers of recently hospitalized patients. The PFAC participated in monthly meetings throughout the study period. They helped inform the research questions, including confirmation that the endpoints were patient centered, and provided valuable input for the design of the intervention and the patient-facing components of the data collection instruments. They also interviewed several patient participants in the study regarding their experiences with the intervention. Lastly, they helped develop plans for dissemination of study results to the public.19

We also formed a steering committee consisting of physician, nursing, pharmacy, information technology, and administrative leadership representing primary care, inpatient care, and transitional care at both hospitals and Partners Healthcare. PFAC members took turns participating in quarterly steering committee meetings.

Evolution of the Intervention and Implementation

The intervention was iteratively refined during the course of the study in response to input from the PFAC, steering committee, and members of the intervention team; cases of adverse events and readmissions from patients despite being in the intervention arm; exit interviews of patients who had recently completed the intervention; and informal feedback from inpatient and outpatient clinicians. For example, we learned that the more complicated a patient’s conditions are, the sooner the clinical team wanted them to be seen after discharge. However, these patients were also less likely to feel well enough to keep that appointment. Therefore, the timing of follow-up of appointments needed to be a negotiation among the inpatient team, the patient, any caregivers, and the outpatient provider. PFAC members also emphasized that patients wanted one person to trust and to be the “point person” during a complicated transition such as hospital discharge.

At the same time, the intervention components evolved because of factors outside our control (eg, resource limitations). In keeping with the real-world nature of the research, the aim was for the intervention to be internally supported because incentives were theoretically more aligned with improvement of care transitions under the ACO model. By design, the PCORI contract only paid for limited parts of the intervention, such as a nurse practitioner to act as the discharge advocate at one hospital, overtime costs of inpatient pharmacists, and project manager time to facilitate inpatient-outpatient provider communication. (See Table 1 of Appendix 1 for details about the modifications to the intervention.)

Lastly, in keeping with PCORI’s methodology standards for studies of complex interventions,20 we strove to standardize the intervention by function across hospitals, units, and practices, while still allowing for local adaptation in the form. In other words, rather than specifying exactly how a task (eg, medication counseling) needed to be performed, the study design offered sites flexibility in how they implemented the task given their available personnel and institutional culture.

Intervention Fidelity

To determine the extent to which each patient in the intervention arm received each intervention component, a project manager unblinded to treatment arm reviewed the electronic medical record for documentation of each component implemented by providers (eg, inpatient pharmacists, outpatient nurses). Because each intervention component produced documentation, this provided an accurate assessment of intervention fidelity, ie, the extent to which the intervention was implemented as intended.

Outcome Assessment

Postdischarge Follow-up

Based on previous studies,2,21 a trained research assistant attempted to contact all study subjects 30 days (±5 days) after discharge and administered a questionnaire to identify any new or worsening symptoms since discharge, any healthcare use since discharge, and functional status in the previous week. Follow-up questions used branching logic to determine the relationship of any new or worsening symptoms to medications or other aspects of medical management. Research assistants followed up any positive responses with directed medical record review for objective findings, diagnoses, treatments, and responses. If patients could not be reached after five attempts, the research assistant instead conducted a thorough review of the outpatient medical record alone for provider reports of any new or worsening symptoms noted during follow-up within the 30-day postdischarge period. Research assistants also reviewed laboratory test results in all patients for evidence of postdischarge renal failure, elevated liver function tests, or new/worsening anemia.

Hospital Readmissions

We measured nonelective hospital readmissions within 30 days of discharge using a combination of administrative data for hospitalizations within the ACO network plus patient report during the 30-day phone call for all other readmissions.22

Adjudication of Outcomes

Adverse events and preventable adverse events: All cases of new or worsening symptoms or signs, along with all supporting documentation, were then presented to teams of two trained blinded physician adjudicators through application of methods established in previous studies.4,21 Each of the two adjudicators independently reviewed the information, along with the medical record, and completed a standardized form to confirm or deny the presence of any adverse events (ie, patient injury due to medical management) and to classify the type of event (eg, adverse drug event, hospital-acquired infection, procedural complication, diagnostic or management error), the severity and duration of the event, and whether the event was preventable or ameliorable. The two adjudicators then met to resolve any differences in their findings and come to consensus.

Preventable readmissions: If patients were readmitted to either study hospital, we conducted an evaluation, based on previous studies,23 to determine if and how the readmission could have been prevented including (a) a standardized patient and caregiver interview to identify possible problems with the transitions process and (b) an email questionnaire to the patient’s PCP and the inpatient teams who cared for the patient during the index admission and readmission regarding possible deficiencies with the transitions process. As with adverse event adjudications, two physician adjudicators worked independently to classify the preventability of the readmission and then met to come to consensus. Conflicts were resolved by a third adjudicator.

Analysis Plan

To evaluate the effects of the intervention on the primary outcome, the number of postdischarge adverse events per patient, we used multivariable Poisson regression, with study arm as the main predictor. A similar approach was used to evaluate the number of new or worsening postdischarge signs or symptoms and the number of preventable adverse events per patient. We used an intention-to-treat analysis: If a practice did not start the intervention when they were scheduled to, based on our randomization, we counted all patients in that practice admitted after that point as intervention patients. We adjusted for patient demographics, clinical characteristics, month, inpatient unit, and primary care practice as fixed effects. We clustered by PCP using general linear models. Intervention effects were expressed as both unadjusted and adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs). We also conducted a limited number of subgroup analyses, determined a priori, to determine whether the intervention was more effective in certain patient populations; we used interaction terms (intervention × subgroup) to determine the statistical significance of any effect modification.

To evaluate the effects of the intervention on nonelective readmissions and preventable readmissions, we used a similar approach, using multivariable logistic regression. Postdischarge functional status, adjusted for status prior to admission, was analyzed using multivariable linear regression and random effects by primary care practice. The general linear mixed model (GLIMMIX) procedure in the SAS 9.3 statistical package (SAS Institute) was used to carry out all analyses.

Power and Sample Size

We assumed a baseline rate of postdischarge adverse events of 0.30 per patient.21 We conservatively assumed an effect size of a change from 0.30 in the control group to 0.23 in the intervention group (a relative reduction of 22%, which was based on studies of preventability rates23 and close to the minimum clinically important difference). Based on prior studies,4,22 we assumed an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.01 with an average cluster size of seven patients per PCP. Assuming a 10% loss to follow-up rate and an alpha of 0.05, we targeted a sample size of 1,800 patients to achieve 80% power, with one-third of the patients in the usual care arm and two-thirds in the intervention arm.

RESULTS

We enrolled 18 PCMH primary care practices to participate in the study, including 8 from Hospital A (out of 13 approached), 8 from Hospital B (out of 11), and 2 from other ACO practices (out of 9) (plus two pilot practices). Reasons for not participating included not having dedicated personnel to play the role of the responsible outpatient clinician, undergoing recent turn-over in practice leadership, and not having enough patients admitted to the two hospitals. One practice only enrolled 5 patients in the study and withdrew from participation, which left 17 practices.

Study Patients

We enrolled 1,679 patients (Figure 1). Reasons for nonenrollment included being unable to complete the screen prior to discharge, not meeting inclusion criteria or meeting exclusion criteria, being assigned to a pilot practice, and declining informed written consent. The baseline characteristics of enrolled patients are presented in Table 2. Differences between the two study arms were small. About 47% of the cohort was not reachable by phone after five attempts for the 30-day phone call, but only 69 (4.1%) were truly lost to follow-up because they were unreachable by phone and had no documentation in the electronic medical record in the 30-days after discharge.

Intervention Fidelity

The majority of patients did not receive most intervention components, even those components that were supposed to be delivered to all intervention patients (Table 3). A minority of patients were referred to visiting nurse services and to the home pharmacy program. However, 855 patients (87%) in the intervention arm received at least one intervention component.

Outcome Measures

The intervention was associated with a statistically significant reduction in several of the outcomes of interest, including the primary outcome, number of postdischarge adverse events (45% reduction), and new or worsening postdischarge signs or symptoms (22% reduction), as well as preventable postdischarge adverse events (58% reduction) (Table 4). There was a nonsignificant difference in functional status. There was no significant effect on total nonelective or on preventable readmission rates. When analyzed by type of adverse event, the intervention was associated with a reduction in adverse drug events and in procedural complications (Table 2 of Appendix 1). Of note, there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients with at least one adverse event whether the outcome was determined by phone call and medical record review (49%) or medical record review alone (51%) (P = .48).

In subgroup analyses, there was no evidence of effect modification by service, hospital, patient age, readmission risk, health literacy, or comorbidity score (Table 3 of Appendix 1). Table 4 of Appendix 1 provides examples of postdischarge adverse events seen in the usual care arm that might have been prevented in the intervention.

DISCUSSION

This intervention was associated with a reduction in postdischarge adverse events. The relative improvement in each outcome aligned with the hypothesized sensitivity to change: the smallest improvement was seen in new or worsening signs or symptoms, followed by postdischarge adverse events and then by preventable postdischarge adverse events. The intervention was not associated with a difference in readmissions. The lack of effect on hospital readmissions may have been caused by the low proportion of readmissions that are preventable, as well as low intervention fidelity and lack of resources to implement facets such as postdischarge coaching, an evidence-based intervention that was never adopted.16,23 One lesson of this study is that it may be easier to reduce postdischarge injury (still an important outcome) than readmissions.

Putting this study in context, we should note that the literature on interventions to improve care transitions is mixed.18 While there are several reports of successful interventions, there are many reports of unsuccessful ones, often using similar components. Success is often the result of adequate resources and attention to myriad details regarding implementation.24 The intervention in our study likely contributed to improvements in patient and caregiver engagement in the hospital, enhancements of communication between inpatient and outpatient clinicians, and implementation of pharmacist-led interventions to improve medication safety. Regarding the latter, several prior studies have shown the benefits of pharmacist interventions in decreasing postdischarge adverse drug events.4,25,26 Therefore, even an intervention with incomplete intervention fidelity can reduce postdischarge adverse events, especially because adverse drug events make up the majority of adverse events.1,2,21

Perhaps the biggest lesson we learned was regarding the limitations of the hospital-led ACO model to incentivize sufficient up-front investments in transitional care interventions. By design, we chose a real-world approach in which interventions were integrated with existing ACO efforts, which were paid for internally by the institution. As a result, many of the interventions had to be scaled back because of resource constraints. The ACO model theoretically incentivizes more integrated care, but this may not always be true in practice. Emerging evidence suggests that physician group–led ACOs are associated with lower costs and use compared with hospital-led ACOs, likely because of more aligned incentives in physician group–led ACOs to reduce use of inpatient care.27,28

An unresolved question is whether the ideal implementation approach is to protect the time of existing clinical personnel to carry out transitional care tasks or to hire external personnel to do these tasks. We purposely spread the intervention over several clinician types to minimize the additional burden on any one of them, minimize additional costs, and play to each clinician’s expertise, but in retrospect, this may not have been the right approach. By providing additional personnel with dedicated time, interest, and training in care transitions, the intervention may be delivered with higher quantitative and qualitative fidelity, and it could create a single point of contact for patients, which was considered highly desirable by our PFAC.

This study has several limitations. A large proportion of patients (44%) were unavailable for postdischarge phone calls. However, we were able to perform medical record review for worsening signs (eg, lab abnormalities) and symptoms (as reported by patients’ providers) in the postdischarge period and adjudicate them for adverse events for all but 69 of these patients. Because all these patients had ACO-affiliated PCPs, we would expect most of their utilization to have been within the system and, therefore, to be present in the medical record. The proportion of patients with at least one adverse event did not vary by the method of follow-up, which suggests that this issue is an unlikely source of bias. Assessment of readmission was imperfect because we do not have statewide or national data. However, our combination of administrative data for Partners readmissions plus self-report for non-Partners readmission has been shown to be fairly complete in previous studies.29 Adjudicators could not be fully blinded to intervention status due to the lack of blinding of admission date. We did not calculate a kappa value for interrater reliability of individual assessments of adverse events; rather, coming to consensus among the two adjudicators was part of the process. In only a handful of cases was a third adjudicator required. Lastly, this study was conducted at two academic medical centers and their affiliated primary care clinics, which potentially limits generalizability; however, the results are likely generalizable to other ACOs that include major academic medical centers.

CONCLUSION