User login

What’s the Purpose of Rounds? A Qualitative Study Examining the Perceptions of Faculty and Students

For more than a century, medical rounds have been a cornerstone of patient care and medical education in teaching hospitals. They remain critical activities for exposing generations of trainees to clinical decision making, coordination of care, and patient communication.1

Despite this established importance within medical education and patient care, there is a relative paucity of research addressing the purpose of medical rounds in the 21st century. Medicine has evolved significantly since Osler’s day, and it is unclear whether the purpose of rounds has evolved along with it. Rounds, to Osler, were an important opportunity for future physicians to learn at the bedside from an attending physician. Increased duty hour restrictions, mandatory adoption of electronic medical records, and increasingly complex care have changed how rounds are performed, making it more difficult to achieve Osler’s ideals.2,3 While several studies have aimed to quantify the changes to rounds and have demonstrated a significant decline in bedside teaching,4-6 few studies have explored the purpose of rounds from the perspective of pertinent stakeholders, students, residents, and faculty. The authors have published the results of focus groups of resident stakeholders recently.7 We made the decision to combine the student/faculty data and describe it separately from the resident data to allow the most accurate and relevant discussion as it pertained to each group.

The aim of this study was to explore the perceptions of faculty and students of general inpatient rounds on internal medicine and pediatric rotations, and to identify any notable differences between these key stakeholders.

METHODS

Between April 2014 and June 2014, we conducted 10 semistructured focus groups at 4 teaching hospitals: The University of Chicago Medical Center, Children’s National Health System, Georgetown University Medical Center, and the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center. A sample of eligible 3rd-year medical students and residents on pediatrics and internal medicine hospitalist services as well as hospitalist attendings in pediatrics and internal medicine were invited by e-mail to participate voluntarily without compensation. Identical semistructured focus groups were also conducted with pediatric and internal medicine interns (postgraduate year [PGY1]) and senior residents (PGY2 and PGY3), and those data have been published previously.7

Data Collection

Most focus groups had 6 to 8 participants, with 2 groups of 3 and 4. The groups were interviewed separately by training and specialty: 3rd-year medical students who had completed internal medicine and/or pediatrics rotations, hospitalist attendings in pediatrics, and hospitalist attendings in internal medicine. Attendings with training in medicine-pediatrics were included in the department in which they worked most frequently. The focus group script was informed by a literature review and expert input, and we used open-ended questions to explore perspectives on current and ideal purposes of rounds. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and names of speakers or references to specific patients were removed to preserve confidentiality and anonymity. The focus groups lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. The author (OH) conducted focus groups at 1 site, and trained facilitators conducted focus groups at the remaining 3 sites. The protocol was determined to be exempt by the institutional review boards at all participating sites. Prior to the focus groups, the definition of family-centered rounds was read aloud; after which, participants were asked to fill out a demographic survey.

Data Analysis

The authors employed a grounded theory approach to data collection and analysis,8 and data were analyzed by using the constant-comparative method.9 There was no a priori hypothesis. Four transcripts were independently reviewed by 2 authors (OH and RR) by using sentences and phrases as the units of data, which were coded with an identifier. The authors discussed initial codes and resolved discrepancies through deliberation and consensus to create codebooks. Themes, made up of multiple codes, were identified inductively and iteratively and were refined to reflect the evolving dataset. One author (OH) independently coded the remaining transcripts by using a revised codebook as a guide. A faculty author (JF) assessed the interrater reliability of the final codebook by reviewing 2 previously coded, randomly selected transcripts with no new codes emerging in the process, with a kappa coefficient of >0.8 indicating significant agreement.

RESULTS

What Do You Perceive the Purpose of Rounds to Be?

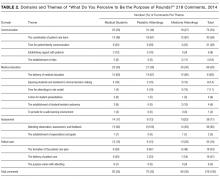

With respect to this prompt, we identified 4 themes, which represent 16 codes describing what attendings and medical students believed to be the purpose of rounds (Table 2). These themes are communication, medical education, patient care, and assessment.

Communication

Communication includes all comments addressing the role of rounds as it relates to communication between team members, patients, family members, and all those involved in patient care. There were 4 main codes, including coordination of patient care team, patient/family communication, establishing rapport with patients and/or family, and establishment of roles.

Coordination of patient care team identified rounds as a time “to make sure everyone is on the same page” and “to come together whenever possible,” so that everyone “had the same information of what was going on.” It also included comments related to interdisciplinary communication, with 1 participant describing rounds as “a time when your consulting team, or people with outside expertise, can weigh in on some medical issues.”

Medical Education

The theme of medical education is made up of 6 codes that encompass comments related to teaching and learning during rounds. These 6 codes include delivery of clinical education, exposure to clinical decision making, role modeling, student presentations, establishment of trainee autonomy, and providing a safe learning environment.

Delivery of clinical education included comments identifying rounds as a time for didactic teaching, teachable moments, “clinical pearls,” and bedside teaching of physical exam skills. Exposure to clinical decision making included comments by both medical students and attendings who described the purpose of rounds as a time for learning and teaching, specifically about how best to approach problems and decision making in a systematic manner, with 1 medical student explaining it as a time to “expose [trainees] to the way that people think about problems and how they decided to go about addressing them.”

Role modeling includes comments addressing rounds as a time for attendings to demonstrate appropriate behaviors and skills to trainees. One attending explained that “everybody learns from watching other people present and interact…so everybody has a chance to pick up things that they think, ‘Oh, this works well.’” Student presentations include comments, predominantly from students, that described rounds as an opportunity to practice presentations and receive feedback, with 1 student explaining it was a time “to learn how to present but also to be questioned and challenged.”

Establishing trainee autonomy is a code that identifies rounds as a time to encourage resident and student autonomy in order to achieve rounds that function with minimal input from the attending, with 1 attending describing how they “put resident leadership first as far as priorities… [and] fostering that because I usually let them decide what we’re going to do.”

Providing a safe learning environment identifies the purpose of rounds as being a space in which trainees can feel comfortable learning from their mistakes. One student described rounds as, “…a setting where it’s okay to be wrong and feel comfortable enough to know that it’s about a learning process.”

Assessment

Assessment is a theme composed of comments identifying the purpose of rounds as being related to observation, assessment, and feedback, and it includes 2 codes: attending observation, assessment, and feedback and establishment of expectations. Attending observation, assessment, and feedback includes comments from attendings and students alike who described rounds as a place for observation, evaluation, and provision of feedback regarding the skills and abilities of trainees. One attending explained that rounds gave him an “opportunity to observe trainees interacting with each other, with the patient, the patient’s family, and ancillary staff,” with another commenting it was time used “to assess how med students are gathering information, presenting information, and eventually their assessment and plan.” Establishment of expectations captures comments that describe rounds as a time for the establishment of expectations and goals of the team.

Patient Care

Patient care is a theme comprised of comments identifying the purpose of rounds as being directly related to the formation and delivery of the patient care plan, and it includes 2 codes: formation of the patient care plan and delivery of patient care. Formation of the patient care plan includes comments, which identified rounds as a time for discussing and forming the plan for the day, with an attending stating, “The purpose [of rounds] was to make a plan, a treatment plan, and to include the parents in making the treatment plan.” Delivery of patient care included comments identifying rounds as a means of ensuring timely, safe, and appropriate delivery of patient care occurred. One attending explained, “It can’t be undersold that the priority of rounds is patient care and the more eyes that look over information the less likely there are to be mistakes.”

What Do You Believe the Ideal Purpose of RoundsShould Be?

This study originally sought to compare responses to 2 different questions: “What do you perceive the purpose of rounds to be?” and “What do you believe the ideal purpose of rounds should be?” What became clear during the focus groups was that these were often interpreted to be the same question, and as such, responses to the latter question were truncated or were reiterations of what was previously said: “I think we’ve already discussed that, I think it’s no different than what we already kind of said, patient care, education, and communication,” explained 1 attending. Fifty-four responses to the question regarding the ideal purpose of rounds were coded and did not differ significantly from the previously noted results in terms of the domains represented and the frequency of representation.

Variation Among Respondents

Overall, there is a high level of concordance between the comments from medical students and attendings regarding the purpose of rounds, particularly in the medical education theme. However, medicine and pediatric attendings differ in their comments relating to the theme of communication, with 2 codes primarily accounting for this difference: pediatric attendings place more emphasis on time for patient/family communication and establishing rapport with patients than their internal medicine colleagues. Of note, all of the pediatric attendings involved in the study answered that they conducted family-centered rounds (FCR), compared with 22% of internal medicine attendings.10

Another notable discrepancy came up during focus groups involving comments from medical students who reiterated that the purpose of rounds was not fixed, but rather dependent on the attending that was running rounds. This theme was only identified in focus groups involving medical students. One student explained, “I think that it depends on the attending and if they actually want to teach,” and another commented that “it’s incredibly dependent on what the attending… is willing to invest.” No attendings identified student or attending variability as an important factor influencing the purpose of rounds.

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study is one of the first to explore the purpose of rounds from the perspective of both medical students and attendings. Reassuringly, our results indicate that medical student and attending perceptions are largely concordant. The 4 themes of communication, medical education, assessment, and patient care are in line with the findings of previous observational studies of internal medicine and pediatrics rounds.1,11 The themes are similar to the findings of resident focus groups done at these same sites.7

Our results support that both medical students and attendings identify the importance of medical education during rounds. This is in contrast with findings in previous observational time-motion research by Stickrath that describes the focus on patient care related activities and the relative scarcity of education during rounds.1 This stresses a divide between how medical students and attendings define the purpose of rounds and what other research suggests actually occurs on rounds. This distinction is an important one. It is possible that the way we, and others, define “medical education” and “patient care” may be at least partially responsible for these findings. This is supported by the ambiguous distinction between formal and informal educational activities on rounds and the challenges in characterizing the hidden curriculum and its role in medical student and resident education.11 Attendings role modeling effective patient communication strategies, for example, highlights that patient care, medical education, and communication are frequently indistinguishable.12 This hybridization of activities and dedication to diverse types of learning is an essential quality of rounds and is suggestive of why they have survived as a preeminent tool within the arsenal of medical education for the past century.

Yet, this finding does not excuse or adequately explain a well-documented disappearance of more formal educational activities during rounds. Recent observational studies have shown that the percentage of rounds dedicated to educational activities fell from 25% to 10% after the implementation of duty hour restrictions,1,13,14 and a recent ethnographic study of pediatric attending rounds confirmed teaching during rounds, though seen as a pedagogical ideal, occurred infrequently and inconsistently in large part because of time pressures.15 In our attending focus groups, duty hours and time pressures were frequently cited as actively working against the purpose of rounds, specifically opportunities for teaching, with 1 attending explaining, “I just don’t think we achieve our [teaching] goals like we used to.” Another attending mentioned that, because of time pressures, “I often find myself apologizing. ‘I’m so sorry. I can’t resist. Can I just tell you this one thing? I’m so sorry to do teaching.’” This tension between time pressures and education on rounds is well documented in the literature.4,16,17

Our results highlight that attendings and medical students still believe that medical education is a primary and important purpose of rounds even in the face of increasing time pressures. As such, efforts should be made to better align the many purposes of rounds with the realities of the modern day rounding environment. Increasing the presence of medical education on rounds need not be at the expense of time given that techniques like the 1-minute preceptor have been rated as both efficient and effective methods of teaching and delivering feedback.18 This is echoed in research that has found that faculty development with a focus on teaching significantly increased the rate of clinical education and interdisciplinary communication during rounds.1 Opportunities for faculty development are increasingly accessible,19 including programs like the Advancing Pediatric Excellence Teaching Program, sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine and the Academic Pediatric Association, and the Teaching Educators Across the Continuum of Healthcare program, sponsored by the Society for General Internal Medicine.20,21

A testament to the adaptability of rounds can be seen in our findings that expose the increased emphasis with which pediatric attendings identify communication as a purpose of rounds, particularly within the themes of patient/family communication and establishing rapport with patients. This is likely due to the practice of FCR by 100% of the pediatric attendings in our focus groups, and is supported elsewhere in the literature.22 A key to family-centered rounds is communication, with active participation in the care discussion by patients and families as described and endorsed by a 2012 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy.10,23

This emphasis could explain the increased frequency of comments made by pediatric attendings within the themes of patient/family communication and establishing rapport with patients. Furthermore, the AAP policy statement stresses the need to share information in a way that patients and families “effectively participate in care and decision making,” which could explain why pediatric attendings placed greater emphasis on the formation of the patient care plan in the theme of patient care.

As noted, the authors published a related study focusing on resident perceptions regarding the purpose of rounds. We initially undertook a separate analysis of the 3 groups: faculty, residents, and medical students. From that analysis, it became apparent that residents (PGY1-PGY3) viewed rounds differently than faculty and medical students. Where faculty and medical students were more focused on communication and medical education, the residents were more focused on the practical aspects of rounds (eg, “getting work done”). It was also noted that the residents’ focus aligned with the graduate medical education

Our study has a number of limitations. Only 4 university-based hospitals were included in the focus groups. This has the potential to limit the generalizability to the community hospital setting. Within the focus groups, the number of participants varied, and this may have had an impact on the flow and content of conversation. Facilitators were chosen to minimize potential bias and prior relationships with participants; however, this was not always possible, and as such, may have influenced responses. There may be a discrepancy between how people perceive rounds and how rounds actually function. Rounds were not standardized between institutions, departments, or attendings.

CONCLUSION

Rounds are an appropriate metaphor for medical education at large: they are time consuming, complex, and vary in quality, but are nevertheless essential to the goals of patients and learners alike because of their adaptability and hybridization of purpose. Our results highlight that rounds serve 4 critical purposes, including communication, medical education, patient care, and assessment. Importantly, both attendings and students agree on what they perceive to be the many purposes of rounds. Despite this agreement, a disconnect appears to exist between what people believe are the purposes of rounds and what is perceived to be happening during rounds. The causes of this gap are not well defined, and further efforts should be made to better understand the obstacles facing effective rounding. To improve rounds and adapt them to the needs of 21st century learners, it is critical that we better define the scope of medical education, both formal and informal, that occurs during rounds. In doing so, it will be possible to identify areas of development and training for faculty, residents, and medical students, which will ensure that rounds remain useful and critical tools for the development and education of future physicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following people who assisted on this project: Meghan Daly from The University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, Shannon Martin, MD, MS, Assistant Professor of Medicine from the Department of Medicine at The University of Chicago, Joyce Campbell, BSN, MS, Senior Quality Manager at the Children’s National Medical Center, Benjamin Colburn from the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, Kelly Sanders from the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, and Alekist Quach from the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine.

Disclosure

The authors report no external funding source for this study. The authors declare no conflict of interest. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at all participating institutions.

1. Stickrath C, Noble M, Prochazka A, et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084-1089. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6041 PubMed

2. Osler SW. Osler’s “A Way of Life” and Other Addresses, with Commentary and Annotations. Durham: Duke University Press; 2001.

3. Peters M, Ten Cate O. Bedside teaching in medical education: a literature review. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3(2):76-88. doi:10.1007/s40037-013-0083-y PubMed

4. Gonzalo JD, Heist BS, Duffy BL, et al. Identifying and Overcoming the Barriers to Bedside Rounds: A Multicenter Qualitative Study. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):326-334. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000100 PubMed

5. Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ, Chuang CH. Attending Rounds and Bedside Case Presentations: Medical Student and Medicine Resident Experiences and Attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105-110. doi:10.1080/10401330902791156 PubMed

6. Payson HE, Barchas JD. A Time Study of Medical Teaching Rounds. N Engl J Med. 1965;273(27):1468-1471. doi:10.1056/NEJM196512302732706 PubMed

7. Rabinowitz R, Farnan J, Hulland O, et al. Rounds Today: A Qualitative Study of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics Resident Perceptions. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(4):523-531. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00106.1 PubMed

8. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications; 2006. PubMed

9. Starks H, Trinidad SB. Choose Your Method: A Comparison of Phenomenology, Discourse Analysis, and Grounded Theory. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1372-1380. doi:10.1177/1049732307307031 PubMed

10. Sisterhen LL, Blaszak RT, Woods MB, Smith CE. Defining Family-Centered Rounds. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(3):319-322. doi:10.1080/10401330701366812 PubMed

11. Witman Y. What do we transfer in case discussions? The hidden curriculum in medicine…. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3(2):113-123. doi:10.1007/s40037-013-0101-0 PubMed

12. Benbassat J. Role Modeling in Medical Education: The Importance of a Reflective Imitation. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):550-554. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000189 PubMed

13. Miller M, Johnson B, Greene DHL, Baier M, Nowlin S. An observational study of attending rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(6):646-648. doi:10.1007/BF02599208 PubMed

14. Priest JR, Bereknyei S, Hooper K, Braddock CH III. Relationships of the Location and Content of Rounds to Specialty, Institution, Patient-Census, and Team Size. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11246. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011246 PubMed

15. Balmer DF, Master CL, Richards BF, Serwint JR, Giardino AP. An ethnographic study of attending rounds in general paediatrics: understanding the ritual. Med Educ. 2010;44(11):1105-1116. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03767.x PubMed

16. Bhansali P, Birch S, Campbell JK, et al. A Time-Motion Study of Inpatient Rounds Using a Family-Centered Rounds Model. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(1):31-38. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2012-0021 PubMed

17. Reed DA, Levine RB, Miller RG, et al. Impact of Duty Hour Regulations on Medical Students’ Education: Views of Key Clinical Faculty. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1084-1089. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0532-1 PubMed

18. Aagaard E, Teherani A, Irby DM. Effectiveness of the One-Minute Preceptor Model for Diagnosing the Patient and the Learner: Proof of Concept. Acad Med Spec Theme Teach Clin Ski. 2004;79(1):42-49. PubMed

19. Swanwick T. See one, do one, then what? Faculty development in postgraduate medical education. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84(993):339-343. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2008.068288 PubMed

20. Advancing Pediatric Educator Excellence (APEX) Teaching Program. The American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/Committees-Councils-Sections/Section-on-Hospital-Medicine/Pages/Advancing-Pediatric-Educator-Excellence.aspx?nfstatus=401&nftoken=00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000&nfstatusdescription=ERROR:+No+local+token. Accessed August 22, 2016.

21. TEACH: Teaching Educators Across the Continuum of Healthcare. Society of General Internal Medicine. http://www.sgim.org/communities/education/sgim-teach-program. Accessed August 22, 2016.

22. Mittal V, Krieger E, Lee BC, et al. Pediatrics Residents’ Perspectives on Family-Centered Rounds: A Qualitative Study at 2 Children’s Hospitals. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):81-87. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-00314.1 PubMed

23. Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Patient- and Family-Centered Care and the Pediatrician’s Role. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394-404. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3084 PubMed

For more than a century, medical rounds have been a cornerstone of patient care and medical education in teaching hospitals. They remain critical activities for exposing generations of trainees to clinical decision making, coordination of care, and patient communication.1

Despite this established importance within medical education and patient care, there is a relative paucity of research addressing the purpose of medical rounds in the 21st century. Medicine has evolved significantly since Osler’s day, and it is unclear whether the purpose of rounds has evolved along with it. Rounds, to Osler, were an important opportunity for future physicians to learn at the bedside from an attending physician. Increased duty hour restrictions, mandatory adoption of electronic medical records, and increasingly complex care have changed how rounds are performed, making it more difficult to achieve Osler’s ideals.2,3 While several studies have aimed to quantify the changes to rounds and have demonstrated a significant decline in bedside teaching,4-6 few studies have explored the purpose of rounds from the perspective of pertinent stakeholders, students, residents, and faculty. The authors have published the results of focus groups of resident stakeholders recently.7 We made the decision to combine the student/faculty data and describe it separately from the resident data to allow the most accurate and relevant discussion as it pertained to each group.

The aim of this study was to explore the perceptions of faculty and students of general inpatient rounds on internal medicine and pediatric rotations, and to identify any notable differences between these key stakeholders.

METHODS

Between April 2014 and June 2014, we conducted 10 semistructured focus groups at 4 teaching hospitals: The University of Chicago Medical Center, Children’s National Health System, Georgetown University Medical Center, and the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center. A sample of eligible 3rd-year medical students and residents on pediatrics and internal medicine hospitalist services as well as hospitalist attendings in pediatrics and internal medicine were invited by e-mail to participate voluntarily without compensation. Identical semistructured focus groups were also conducted with pediatric and internal medicine interns (postgraduate year [PGY1]) and senior residents (PGY2 and PGY3), and those data have been published previously.7

Data Collection

Most focus groups had 6 to 8 participants, with 2 groups of 3 and 4. The groups were interviewed separately by training and specialty: 3rd-year medical students who had completed internal medicine and/or pediatrics rotations, hospitalist attendings in pediatrics, and hospitalist attendings in internal medicine. Attendings with training in medicine-pediatrics were included in the department in which they worked most frequently. The focus group script was informed by a literature review and expert input, and we used open-ended questions to explore perspectives on current and ideal purposes of rounds. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and names of speakers or references to specific patients were removed to preserve confidentiality and anonymity. The focus groups lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. The author (OH) conducted focus groups at 1 site, and trained facilitators conducted focus groups at the remaining 3 sites. The protocol was determined to be exempt by the institutional review boards at all participating sites. Prior to the focus groups, the definition of family-centered rounds was read aloud; after which, participants were asked to fill out a demographic survey.

Data Analysis

The authors employed a grounded theory approach to data collection and analysis,8 and data were analyzed by using the constant-comparative method.9 There was no a priori hypothesis. Four transcripts were independently reviewed by 2 authors (OH and RR) by using sentences and phrases as the units of data, which were coded with an identifier. The authors discussed initial codes and resolved discrepancies through deliberation and consensus to create codebooks. Themes, made up of multiple codes, were identified inductively and iteratively and were refined to reflect the evolving dataset. One author (OH) independently coded the remaining transcripts by using a revised codebook as a guide. A faculty author (JF) assessed the interrater reliability of the final codebook by reviewing 2 previously coded, randomly selected transcripts with no new codes emerging in the process, with a kappa coefficient of >0.8 indicating significant agreement.

RESULTS

What Do You Perceive the Purpose of Rounds to Be?

With respect to this prompt, we identified 4 themes, which represent 16 codes describing what attendings and medical students believed to be the purpose of rounds (Table 2). These themes are communication, medical education, patient care, and assessment.

Communication

Communication includes all comments addressing the role of rounds as it relates to communication between team members, patients, family members, and all those involved in patient care. There were 4 main codes, including coordination of patient care team, patient/family communication, establishing rapport with patients and/or family, and establishment of roles.

Coordination of patient care team identified rounds as a time “to make sure everyone is on the same page” and “to come together whenever possible,” so that everyone “had the same information of what was going on.” It also included comments related to interdisciplinary communication, with 1 participant describing rounds as “a time when your consulting team, or people with outside expertise, can weigh in on some medical issues.”

Medical Education

The theme of medical education is made up of 6 codes that encompass comments related to teaching and learning during rounds. These 6 codes include delivery of clinical education, exposure to clinical decision making, role modeling, student presentations, establishment of trainee autonomy, and providing a safe learning environment.

Delivery of clinical education included comments identifying rounds as a time for didactic teaching, teachable moments, “clinical pearls,” and bedside teaching of physical exam skills. Exposure to clinical decision making included comments by both medical students and attendings who described the purpose of rounds as a time for learning and teaching, specifically about how best to approach problems and decision making in a systematic manner, with 1 medical student explaining it as a time to “expose [trainees] to the way that people think about problems and how they decided to go about addressing them.”

Role modeling includes comments addressing rounds as a time for attendings to demonstrate appropriate behaviors and skills to trainees. One attending explained that “everybody learns from watching other people present and interact…so everybody has a chance to pick up things that they think, ‘Oh, this works well.’” Student presentations include comments, predominantly from students, that described rounds as an opportunity to practice presentations and receive feedback, with 1 student explaining it was a time “to learn how to present but also to be questioned and challenged.”

Establishing trainee autonomy is a code that identifies rounds as a time to encourage resident and student autonomy in order to achieve rounds that function with minimal input from the attending, with 1 attending describing how they “put resident leadership first as far as priorities… [and] fostering that because I usually let them decide what we’re going to do.”

Providing a safe learning environment identifies the purpose of rounds as being a space in which trainees can feel comfortable learning from their mistakes. One student described rounds as, “…a setting where it’s okay to be wrong and feel comfortable enough to know that it’s about a learning process.”

Assessment

Assessment is a theme composed of comments identifying the purpose of rounds as being related to observation, assessment, and feedback, and it includes 2 codes: attending observation, assessment, and feedback and establishment of expectations. Attending observation, assessment, and feedback includes comments from attendings and students alike who described rounds as a place for observation, evaluation, and provision of feedback regarding the skills and abilities of trainees. One attending explained that rounds gave him an “opportunity to observe trainees interacting with each other, with the patient, the patient’s family, and ancillary staff,” with another commenting it was time used “to assess how med students are gathering information, presenting information, and eventually their assessment and plan.” Establishment of expectations captures comments that describe rounds as a time for the establishment of expectations and goals of the team.

Patient Care

Patient care is a theme comprised of comments identifying the purpose of rounds as being directly related to the formation and delivery of the patient care plan, and it includes 2 codes: formation of the patient care plan and delivery of patient care. Formation of the patient care plan includes comments, which identified rounds as a time for discussing and forming the plan for the day, with an attending stating, “The purpose [of rounds] was to make a plan, a treatment plan, and to include the parents in making the treatment plan.” Delivery of patient care included comments identifying rounds as a means of ensuring timely, safe, and appropriate delivery of patient care occurred. One attending explained, “It can’t be undersold that the priority of rounds is patient care and the more eyes that look over information the less likely there are to be mistakes.”

What Do You Believe the Ideal Purpose of RoundsShould Be?

This study originally sought to compare responses to 2 different questions: “What do you perceive the purpose of rounds to be?” and “What do you believe the ideal purpose of rounds should be?” What became clear during the focus groups was that these were often interpreted to be the same question, and as such, responses to the latter question were truncated or were reiterations of what was previously said: “I think we’ve already discussed that, I think it’s no different than what we already kind of said, patient care, education, and communication,” explained 1 attending. Fifty-four responses to the question regarding the ideal purpose of rounds were coded and did not differ significantly from the previously noted results in terms of the domains represented and the frequency of representation.

Variation Among Respondents

Overall, there is a high level of concordance between the comments from medical students and attendings regarding the purpose of rounds, particularly in the medical education theme. However, medicine and pediatric attendings differ in their comments relating to the theme of communication, with 2 codes primarily accounting for this difference: pediatric attendings place more emphasis on time for patient/family communication and establishing rapport with patients than their internal medicine colleagues. Of note, all of the pediatric attendings involved in the study answered that they conducted family-centered rounds (FCR), compared with 22% of internal medicine attendings.10

Another notable discrepancy came up during focus groups involving comments from medical students who reiterated that the purpose of rounds was not fixed, but rather dependent on the attending that was running rounds. This theme was only identified in focus groups involving medical students. One student explained, “I think that it depends on the attending and if they actually want to teach,” and another commented that “it’s incredibly dependent on what the attending… is willing to invest.” No attendings identified student or attending variability as an important factor influencing the purpose of rounds.

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study is one of the first to explore the purpose of rounds from the perspective of both medical students and attendings. Reassuringly, our results indicate that medical student and attending perceptions are largely concordant. The 4 themes of communication, medical education, assessment, and patient care are in line with the findings of previous observational studies of internal medicine and pediatrics rounds.1,11 The themes are similar to the findings of resident focus groups done at these same sites.7

Our results support that both medical students and attendings identify the importance of medical education during rounds. This is in contrast with findings in previous observational time-motion research by Stickrath that describes the focus on patient care related activities and the relative scarcity of education during rounds.1 This stresses a divide between how medical students and attendings define the purpose of rounds and what other research suggests actually occurs on rounds. This distinction is an important one. It is possible that the way we, and others, define “medical education” and “patient care” may be at least partially responsible for these findings. This is supported by the ambiguous distinction between formal and informal educational activities on rounds and the challenges in characterizing the hidden curriculum and its role in medical student and resident education.11 Attendings role modeling effective patient communication strategies, for example, highlights that patient care, medical education, and communication are frequently indistinguishable.12 This hybridization of activities and dedication to diverse types of learning is an essential quality of rounds and is suggestive of why they have survived as a preeminent tool within the arsenal of medical education for the past century.

Yet, this finding does not excuse or adequately explain a well-documented disappearance of more formal educational activities during rounds. Recent observational studies have shown that the percentage of rounds dedicated to educational activities fell from 25% to 10% after the implementation of duty hour restrictions,1,13,14 and a recent ethnographic study of pediatric attending rounds confirmed teaching during rounds, though seen as a pedagogical ideal, occurred infrequently and inconsistently in large part because of time pressures.15 In our attending focus groups, duty hours and time pressures were frequently cited as actively working against the purpose of rounds, specifically opportunities for teaching, with 1 attending explaining, “I just don’t think we achieve our [teaching] goals like we used to.” Another attending mentioned that, because of time pressures, “I often find myself apologizing. ‘I’m so sorry. I can’t resist. Can I just tell you this one thing? I’m so sorry to do teaching.’” This tension between time pressures and education on rounds is well documented in the literature.4,16,17

Our results highlight that attendings and medical students still believe that medical education is a primary and important purpose of rounds even in the face of increasing time pressures. As such, efforts should be made to better align the many purposes of rounds with the realities of the modern day rounding environment. Increasing the presence of medical education on rounds need not be at the expense of time given that techniques like the 1-minute preceptor have been rated as both efficient and effective methods of teaching and delivering feedback.18 This is echoed in research that has found that faculty development with a focus on teaching significantly increased the rate of clinical education and interdisciplinary communication during rounds.1 Opportunities for faculty development are increasingly accessible,19 including programs like the Advancing Pediatric Excellence Teaching Program, sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine and the Academic Pediatric Association, and the Teaching Educators Across the Continuum of Healthcare program, sponsored by the Society for General Internal Medicine.20,21

A testament to the adaptability of rounds can be seen in our findings that expose the increased emphasis with which pediatric attendings identify communication as a purpose of rounds, particularly within the themes of patient/family communication and establishing rapport with patients. This is likely due to the practice of FCR by 100% of the pediatric attendings in our focus groups, and is supported elsewhere in the literature.22 A key to family-centered rounds is communication, with active participation in the care discussion by patients and families as described and endorsed by a 2012 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy.10,23

This emphasis could explain the increased frequency of comments made by pediatric attendings within the themes of patient/family communication and establishing rapport with patients. Furthermore, the AAP policy statement stresses the need to share information in a way that patients and families “effectively participate in care and decision making,” which could explain why pediatric attendings placed greater emphasis on the formation of the patient care plan in the theme of patient care.

As noted, the authors published a related study focusing on resident perceptions regarding the purpose of rounds. We initially undertook a separate analysis of the 3 groups: faculty, residents, and medical students. From that analysis, it became apparent that residents (PGY1-PGY3) viewed rounds differently than faculty and medical students. Where faculty and medical students were more focused on communication and medical education, the residents were more focused on the practical aspects of rounds (eg, “getting work done”). It was also noted that the residents’ focus aligned with the graduate medical education

Our study has a number of limitations. Only 4 university-based hospitals were included in the focus groups. This has the potential to limit the generalizability to the community hospital setting. Within the focus groups, the number of participants varied, and this may have had an impact on the flow and content of conversation. Facilitators were chosen to minimize potential bias and prior relationships with participants; however, this was not always possible, and as such, may have influenced responses. There may be a discrepancy between how people perceive rounds and how rounds actually function. Rounds were not standardized between institutions, departments, or attendings.

CONCLUSION

Rounds are an appropriate metaphor for medical education at large: they are time consuming, complex, and vary in quality, but are nevertheless essential to the goals of patients and learners alike because of their adaptability and hybridization of purpose. Our results highlight that rounds serve 4 critical purposes, including communication, medical education, patient care, and assessment. Importantly, both attendings and students agree on what they perceive to be the many purposes of rounds. Despite this agreement, a disconnect appears to exist between what people believe are the purposes of rounds and what is perceived to be happening during rounds. The causes of this gap are not well defined, and further efforts should be made to better understand the obstacles facing effective rounding. To improve rounds and adapt them to the needs of 21st century learners, it is critical that we better define the scope of medical education, both formal and informal, that occurs during rounds. In doing so, it will be possible to identify areas of development and training for faculty, residents, and medical students, which will ensure that rounds remain useful and critical tools for the development and education of future physicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following people who assisted on this project: Meghan Daly from The University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, Shannon Martin, MD, MS, Assistant Professor of Medicine from the Department of Medicine at The University of Chicago, Joyce Campbell, BSN, MS, Senior Quality Manager at the Children’s National Medical Center, Benjamin Colburn from the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, Kelly Sanders from the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, and Alekist Quach from the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine.

Disclosure

The authors report no external funding source for this study. The authors declare no conflict of interest. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at all participating institutions.

For more than a century, medical rounds have been a cornerstone of patient care and medical education in teaching hospitals. They remain critical activities for exposing generations of trainees to clinical decision making, coordination of care, and patient communication.1

Despite this established importance within medical education and patient care, there is a relative paucity of research addressing the purpose of medical rounds in the 21st century. Medicine has evolved significantly since Osler’s day, and it is unclear whether the purpose of rounds has evolved along with it. Rounds, to Osler, were an important opportunity for future physicians to learn at the bedside from an attending physician. Increased duty hour restrictions, mandatory adoption of electronic medical records, and increasingly complex care have changed how rounds are performed, making it more difficult to achieve Osler’s ideals.2,3 While several studies have aimed to quantify the changes to rounds and have demonstrated a significant decline in bedside teaching,4-6 few studies have explored the purpose of rounds from the perspective of pertinent stakeholders, students, residents, and faculty. The authors have published the results of focus groups of resident stakeholders recently.7 We made the decision to combine the student/faculty data and describe it separately from the resident data to allow the most accurate and relevant discussion as it pertained to each group.

The aim of this study was to explore the perceptions of faculty and students of general inpatient rounds on internal medicine and pediatric rotations, and to identify any notable differences between these key stakeholders.

METHODS

Between April 2014 and June 2014, we conducted 10 semistructured focus groups at 4 teaching hospitals: The University of Chicago Medical Center, Children’s National Health System, Georgetown University Medical Center, and the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center. A sample of eligible 3rd-year medical students and residents on pediatrics and internal medicine hospitalist services as well as hospitalist attendings in pediatrics and internal medicine were invited by e-mail to participate voluntarily without compensation. Identical semistructured focus groups were also conducted with pediatric and internal medicine interns (postgraduate year [PGY1]) and senior residents (PGY2 and PGY3), and those data have been published previously.7

Data Collection

Most focus groups had 6 to 8 participants, with 2 groups of 3 and 4. The groups were interviewed separately by training and specialty: 3rd-year medical students who had completed internal medicine and/or pediatrics rotations, hospitalist attendings in pediatrics, and hospitalist attendings in internal medicine. Attendings with training in medicine-pediatrics were included in the department in which they worked most frequently. The focus group script was informed by a literature review and expert input, and we used open-ended questions to explore perspectives on current and ideal purposes of rounds. Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed, and names of speakers or references to specific patients were removed to preserve confidentiality and anonymity. The focus groups lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. The author (OH) conducted focus groups at 1 site, and trained facilitators conducted focus groups at the remaining 3 sites. The protocol was determined to be exempt by the institutional review boards at all participating sites. Prior to the focus groups, the definition of family-centered rounds was read aloud; after which, participants were asked to fill out a demographic survey.

Data Analysis

The authors employed a grounded theory approach to data collection and analysis,8 and data were analyzed by using the constant-comparative method.9 There was no a priori hypothesis. Four transcripts were independently reviewed by 2 authors (OH and RR) by using sentences and phrases as the units of data, which were coded with an identifier. The authors discussed initial codes and resolved discrepancies through deliberation and consensus to create codebooks. Themes, made up of multiple codes, were identified inductively and iteratively and were refined to reflect the evolving dataset. One author (OH) independently coded the remaining transcripts by using a revised codebook as a guide. A faculty author (JF) assessed the interrater reliability of the final codebook by reviewing 2 previously coded, randomly selected transcripts with no new codes emerging in the process, with a kappa coefficient of >0.8 indicating significant agreement.

RESULTS

What Do You Perceive the Purpose of Rounds to Be?

With respect to this prompt, we identified 4 themes, which represent 16 codes describing what attendings and medical students believed to be the purpose of rounds (Table 2). These themes are communication, medical education, patient care, and assessment.

Communication

Communication includes all comments addressing the role of rounds as it relates to communication between team members, patients, family members, and all those involved in patient care. There were 4 main codes, including coordination of patient care team, patient/family communication, establishing rapport with patients and/or family, and establishment of roles.

Coordination of patient care team identified rounds as a time “to make sure everyone is on the same page” and “to come together whenever possible,” so that everyone “had the same information of what was going on.” It also included comments related to interdisciplinary communication, with 1 participant describing rounds as “a time when your consulting team, or people with outside expertise, can weigh in on some medical issues.”

Medical Education

The theme of medical education is made up of 6 codes that encompass comments related to teaching and learning during rounds. These 6 codes include delivery of clinical education, exposure to clinical decision making, role modeling, student presentations, establishment of trainee autonomy, and providing a safe learning environment.

Delivery of clinical education included comments identifying rounds as a time for didactic teaching, teachable moments, “clinical pearls,” and bedside teaching of physical exam skills. Exposure to clinical decision making included comments by both medical students and attendings who described the purpose of rounds as a time for learning and teaching, specifically about how best to approach problems and decision making in a systematic manner, with 1 medical student explaining it as a time to “expose [trainees] to the way that people think about problems and how they decided to go about addressing them.”

Role modeling includes comments addressing rounds as a time for attendings to demonstrate appropriate behaviors and skills to trainees. One attending explained that “everybody learns from watching other people present and interact…so everybody has a chance to pick up things that they think, ‘Oh, this works well.’” Student presentations include comments, predominantly from students, that described rounds as an opportunity to practice presentations and receive feedback, with 1 student explaining it was a time “to learn how to present but also to be questioned and challenged.”

Establishing trainee autonomy is a code that identifies rounds as a time to encourage resident and student autonomy in order to achieve rounds that function with minimal input from the attending, with 1 attending describing how they “put resident leadership first as far as priorities… [and] fostering that because I usually let them decide what we’re going to do.”

Providing a safe learning environment identifies the purpose of rounds as being a space in which trainees can feel comfortable learning from their mistakes. One student described rounds as, “…a setting where it’s okay to be wrong and feel comfortable enough to know that it’s about a learning process.”

Assessment

Assessment is a theme composed of comments identifying the purpose of rounds as being related to observation, assessment, and feedback, and it includes 2 codes: attending observation, assessment, and feedback and establishment of expectations. Attending observation, assessment, and feedback includes comments from attendings and students alike who described rounds as a place for observation, evaluation, and provision of feedback regarding the skills and abilities of trainees. One attending explained that rounds gave him an “opportunity to observe trainees interacting with each other, with the patient, the patient’s family, and ancillary staff,” with another commenting it was time used “to assess how med students are gathering information, presenting information, and eventually their assessment and plan.” Establishment of expectations captures comments that describe rounds as a time for the establishment of expectations and goals of the team.

Patient Care

Patient care is a theme comprised of comments identifying the purpose of rounds as being directly related to the formation and delivery of the patient care plan, and it includes 2 codes: formation of the patient care plan and delivery of patient care. Formation of the patient care plan includes comments, which identified rounds as a time for discussing and forming the plan for the day, with an attending stating, “The purpose [of rounds] was to make a plan, a treatment plan, and to include the parents in making the treatment plan.” Delivery of patient care included comments identifying rounds as a means of ensuring timely, safe, and appropriate delivery of patient care occurred. One attending explained, “It can’t be undersold that the priority of rounds is patient care and the more eyes that look over information the less likely there are to be mistakes.”

What Do You Believe the Ideal Purpose of RoundsShould Be?

This study originally sought to compare responses to 2 different questions: “What do you perceive the purpose of rounds to be?” and “What do you believe the ideal purpose of rounds should be?” What became clear during the focus groups was that these were often interpreted to be the same question, and as such, responses to the latter question were truncated or were reiterations of what was previously said: “I think we’ve already discussed that, I think it’s no different than what we already kind of said, patient care, education, and communication,” explained 1 attending. Fifty-four responses to the question regarding the ideal purpose of rounds were coded and did not differ significantly from the previously noted results in terms of the domains represented and the frequency of representation.

Variation Among Respondents

Overall, there is a high level of concordance between the comments from medical students and attendings regarding the purpose of rounds, particularly in the medical education theme. However, medicine and pediatric attendings differ in their comments relating to the theme of communication, with 2 codes primarily accounting for this difference: pediatric attendings place more emphasis on time for patient/family communication and establishing rapport with patients than their internal medicine colleagues. Of note, all of the pediatric attendings involved in the study answered that they conducted family-centered rounds (FCR), compared with 22% of internal medicine attendings.10

Another notable discrepancy came up during focus groups involving comments from medical students who reiterated that the purpose of rounds was not fixed, but rather dependent on the attending that was running rounds. This theme was only identified in focus groups involving medical students. One student explained, “I think that it depends on the attending and if they actually want to teach,” and another commented that “it’s incredibly dependent on what the attending… is willing to invest.” No attendings identified student or attending variability as an important factor influencing the purpose of rounds.

DISCUSSION

This qualitative study is one of the first to explore the purpose of rounds from the perspective of both medical students and attendings. Reassuringly, our results indicate that medical student and attending perceptions are largely concordant. The 4 themes of communication, medical education, assessment, and patient care are in line with the findings of previous observational studies of internal medicine and pediatrics rounds.1,11 The themes are similar to the findings of resident focus groups done at these same sites.7

Our results support that both medical students and attendings identify the importance of medical education during rounds. This is in contrast with findings in previous observational time-motion research by Stickrath that describes the focus on patient care related activities and the relative scarcity of education during rounds.1 This stresses a divide between how medical students and attendings define the purpose of rounds and what other research suggests actually occurs on rounds. This distinction is an important one. It is possible that the way we, and others, define “medical education” and “patient care” may be at least partially responsible for these findings. This is supported by the ambiguous distinction between formal and informal educational activities on rounds and the challenges in characterizing the hidden curriculum and its role in medical student and resident education.11 Attendings role modeling effective patient communication strategies, for example, highlights that patient care, medical education, and communication are frequently indistinguishable.12 This hybridization of activities and dedication to diverse types of learning is an essential quality of rounds and is suggestive of why they have survived as a preeminent tool within the arsenal of medical education for the past century.

Yet, this finding does not excuse or adequately explain a well-documented disappearance of more formal educational activities during rounds. Recent observational studies have shown that the percentage of rounds dedicated to educational activities fell from 25% to 10% after the implementation of duty hour restrictions,1,13,14 and a recent ethnographic study of pediatric attending rounds confirmed teaching during rounds, though seen as a pedagogical ideal, occurred infrequently and inconsistently in large part because of time pressures.15 In our attending focus groups, duty hours and time pressures were frequently cited as actively working against the purpose of rounds, specifically opportunities for teaching, with 1 attending explaining, “I just don’t think we achieve our [teaching] goals like we used to.” Another attending mentioned that, because of time pressures, “I often find myself apologizing. ‘I’m so sorry. I can’t resist. Can I just tell you this one thing? I’m so sorry to do teaching.’” This tension between time pressures and education on rounds is well documented in the literature.4,16,17

Our results highlight that attendings and medical students still believe that medical education is a primary and important purpose of rounds even in the face of increasing time pressures. As such, efforts should be made to better align the many purposes of rounds with the realities of the modern day rounding environment. Increasing the presence of medical education on rounds need not be at the expense of time given that techniques like the 1-minute preceptor have been rated as both efficient and effective methods of teaching and delivering feedback.18 This is echoed in research that has found that faculty development with a focus on teaching significantly increased the rate of clinical education and interdisciplinary communication during rounds.1 Opportunities for faculty development are increasingly accessible,19 including programs like the Advancing Pediatric Excellence Teaching Program, sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine and the Academic Pediatric Association, and the Teaching Educators Across the Continuum of Healthcare program, sponsored by the Society for General Internal Medicine.20,21

A testament to the adaptability of rounds can be seen in our findings that expose the increased emphasis with which pediatric attendings identify communication as a purpose of rounds, particularly within the themes of patient/family communication and establishing rapport with patients. This is likely due to the practice of FCR by 100% of the pediatric attendings in our focus groups, and is supported elsewhere in the literature.22 A key to family-centered rounds is communication, with active participation in the care discussion by patients and families as described and endorsed by a 2012 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) policy.10,23

This emphasis could explain the increased frequency of comments made by pediatric attendings within the themes of patient/family communication and establishing rapport with patients. Furthermore, the AAP policy statement stresses the need to share information in a way that patients and families “effectively participate in care and decision making,” which could explain why pediatric attendings placed greater emphasis on the formation of the patient care plan in the theme of patient care.

As noted, the authors published a related study focusing on resident perceptions regarding the purpose of rounds. We initially undertook a separate analysis of the 3 groups: faculty, residents, and medical students. From that analysis, it became apparent that residents (PGY1-PGY3) viewed rounds differently than faculty and medical students. Where faculty and medical students were more focused on communication and medical education, the residents were more focused on the practical aspects of rounds (eg, “getting work done”). It was also noted that the residents’ focus aligned with the graduate medical education

Our study has a number of limitations. Only 4 university-based hospitals were included in the focus groups. This has the potential to limit the generalizability to the community hospital setting. Within the focus groups, the number of participants varied, and this may have had an impact on the flow and content of conversation. Facilitators were chosen to minimize potential bias and prior relationships with participants; however, this was not always possible, and as such, may have influenced responses. There may be a discrepancy between how people perceive rounds and how rounds actually function. Rounds were not standardized between institutions, departments, or attendings.

CONCLUSION

Rounds are an appropriate metaphor for medical education at large: they are time consuming, complex, and vary in quality, but are nevertheless essential to the goals of patients and learners alike because of their adaptability and hybridization of purpose. Our results highlight that rounds serve 4 critical purposes, including communication, medical education, patient care, and assessment. Importantly, both attendings and students agree on what they perceive to be the many purposes of rounds. Despite this agreement, a disconnect appears to exist between what people believe are the purposes of rounds and what is perceived to be happening during rounds. The causes of this gap are not well defined, and further efforts should be made to better understand the obstacles facing effective rounding. To improve rounds and adapt them to the needs of 21st century learners, it is critical that we better define the scope of medical education, both formal and informal, that occurs during rounds. In doing so, it will be possible to identify areas of development and training for faculty, residents, and medical students, which will ensure that rounds remain useful and critical tools for the development and education of future physicians.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following people who assisted on this project: Meghan Daly from The University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, Shannon Martin, MD, MS, Assistant Professor of Medicine from the Department of Medicine at The University of Chicago, Joyce Campbell, BSN, MS, Senior Quality Manager at the Children’s National Medical Center, Benjamin Colburn from the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, Kelly Sanders from the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, and Alekist Quach from the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine.

Disclosure

The authors report no external funding source for this study. The authors declare no conflict of interest. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at all participating institutions.

1. Stickrath C, Noble M, Prochazka A, et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084-1089. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6041 PubMed

2. Osler SW. Osler’s “A Way of Life” and Other Addresses, with Commentary and Annotations. Durham: Duke University Press; 2001.

3. Peters M, Ten Cate O. Bedside teaching in medical education: a literature review. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3(2):76-88. doi:10.1007/s40037-013-0083-y PubMed

4. Gonzalo JD, Heist BS, Duffy BL, et al. Identifying and Overcoming the Barriers to Bedside Rounds: A Multicenter Qualitative Study. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):326-334. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000100 PubMed

5. Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ, Chuang CH. Attending Rounds and Bedside Case Presentations: Medical Student and Medicine Resident Experiences and Attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105-110. doi:10.1080/10401330902791156 PubMed

6. Payson HE, Barchas JD. A Time Study of Medical Teaching Rounds. N Engl J Med. 1965;273(27):1468-1471. doi:10.1056/NEJM196512302732706 PubMed

7. Rabinowitz R, Farnan J, Hulland O, et al. Rounds Today: A Qualitative Study of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics Resident Perceptions. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(4):523-531. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00106.1 PubMed

8. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications; 2006. PubMed

9. Starks H, Trinidad SB. Choose Your Method: A Comparison of Phenomenology, Discourse Analysis, and Grounded Theory. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1372-1380. doi:10.1177/1049732307307031 PubMed

10. Sisterhen LL, Blaszak RT, Woods MB, Smith CE. Defining Family-Centered Rounds. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(3):319-322. doi:10.1080/10401330701366812 PubMed

11. Witman Y. What do we transfer in case discussions? The hidden curriculum in medicine…. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3(2):113-123. doi:10.1007/s40037-013-0101-0 PubMed

12. Benbassat J. Role Modeling in Medical Education: The Importance of a Reflective Imitation. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):550-554. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000189 PubMed

13. Miller M, Johnson B, Greene DHL, Baier M, Nowlin S. An observational study of attending rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(6):646-648. doi:10.1007/BF02599208 PubMed

14. Priest JR, Bereknyei S, Hooper K, Braddock CH III. Relationships of the Location and Content of Rounds to Specialty, Institution, Patient-Census, and Team Size. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11246. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011246 PubMed

15. Balmer DF, Master CL, Richards BF, Serwint JR, Giardino AP. An ethnographic study of attending rounds in general paediatrics: understanding the ritual. Med Educ. 2010;44(11):1105-1116. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03767.x PubMed

16. Bhansali P, Birch S, Campbell JK, et al. A Time-Motion Study of Inpatient Rounds Using a Family-Centered Rounds Model. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(1):31-38. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2012-0021 PubMed

17. Reed DA, Levine RB, Miller RG, et al. Impact of Duty Hour Regulations on Medical Students’ Education: Views of Key Clinical Faculty. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1084-1089. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0532-1 PubMed

18. Aagaard E, Teherani A, Irby DM. Effectiveness of the One-Minute Preceptor Model for Diagnosing the Patient and the Learner: Proof of Concept. Acad Med Spec Theme Teach Clin Ski. 2004;79(1):42-49. PubMed

19. Swanwick T. See one, do one, then what? Faculty development in postgraduate medical education. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84(993):339-343. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2008.068288 PubMed

20. Advancing Pediatric Educator Excellence (APEX) Teaching Program. The American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/Committees-Councils-Sections/Section-on-Hospital-Medicine/Pages/Advancing-Pediatric-Educator-Excellence.aspx?nfstatus=401&nftoken=00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000&nfstatusdescription=ERROR:+No+local+token. Accessed August 22, 2016.

21. TEACH: Teaching Educators Across the Continuum of Healthcare. Society of General Internal Medicine. http://www.sgim.org/communities/education/sgim-teach-program. Accessed August 22, 2016.

22. Mittal V, Krieger E, Lee BC, et al. Pediatrics Residents’ Perspectives on Family-Centered Rounds: A Qualitative Study at 2 Children’s Hospitals. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):81-87. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-00314.1 PubMed

23. Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Patient- and Family-Centered Care and the Pediatrician’s Role. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394-404. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3084 PubMed

1. Stickrath C, Noble M, Prochazka A, et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084-1089. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6041 PubMed

2. Osler SW. Osler’s “A Way of Life” and Other Addresses, with Commentary and Annotations. Durham: Duke University Press; 2001.

3. Peters M, Ten Cate O. Bedside teaching in medical education: a literature review. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3(2):76-88. doi:10.1007/s40037-013-0083-y PubMed

4. Gonzalo JD, Heist BS, Duffy BL, et al. Identifying and Overcoming the Barriers to Bedside Rounds: A Multicenter Qualitative Study. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):326-334. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000100 PubMed

5. Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ, Chuang CH. Attending Rounds and Bedside Case Presentations: Medical Student and Medicine Resident Experiences and Attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105-110. doi:10.1080/10401330902791156 PubMed

6. Payson HE, Barchas JD. A Time Study of Medical Teaching Rounds. N Engl J Med. 1965;273(27):1468-1471. doi:10.1056/NEJM196512302732706 PubMed

7. Rabinowitz R, Farnan J, Hulland O, et al. Rounds Today: A Qualitative Study of Internal Medicine and Pediatrics Resident Perceptions. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(4):523-531. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00106.1 PubMed

8. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage Publications; 2006. PubMed

9. Starks H, Trinidad SB. Choose Your Method: A Comparison of Phenomenology, Discourse Analysis, and Grounded Theory. Qual Health Res. 2007;17(10):1372-1380. doi:10.1177/1049732307307031 PubMed

10. Sisterhen LL, Blaszak RT, Woods MB, Smith CE. Defining Family-Centered Rounds. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(3):319-322. doi:10.1080/10401330701366812 PubMed

11. Witman Y. What do we transfer in case discussions? The hidden curriculum in medicine…. Perspect Med Educ. 2014;3(2):113-123. doi:10.1007/s40037-013-0101-0 PubMed

12. Benbassat J. Role Modeling in Medical Education: The Importance of a Reflective Imitation. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):550-554. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000189 PubMed

13. Miller M, Johnson B, Greene DHL, Baier M, Nowlin S. An observational study of attending rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(6):646-648. doi:10.1007/BF02599208 PubMed

14. Priest JR, Bereknyei S, Hooper K, Braddock CH III. Relationships of the Location and Content of Rounds to Specialty, Institution, Patient-Census, and Team Size. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11246. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011246 PubMed

15. Balmer DF, Master CL, Richards BF, Serwint JR, Giardino AP. An ethnographic study of attending rounds in general paediatrics: understanding the ritual. Med Educ. 2010;44(11):1105-1116. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03767.x PubMed

16. Bhansali P, Birch S, Campbell JK, et al. A Time-Motion Study of Inpatient Rounds Using a Family-Centered Rounds Model. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(1):31-38. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2012-0021 PubMed

17. Reed DA, Levine RB, Miller RG, et al. Impact of Duty Hour Regulations on Medical Students’ Education: Views of Key Clinical Faculty. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1084-1089. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0532-1 PubMed

18. Aagaard E, Teherani A, Irby DM. Effectiveness of the One-Minute Preceptor Model for Diagnosing the Patient and the Learner: Proof of Concept. Acad Med Spec Theme Teach Clin Ski. 2004;79(1):42-49. PubMed

19. Swanwick T. See one, do one, then what? Faculty development in postgraduate medical education. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84(993):339-343. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2008.068288 PubMed

20. Advancing Pediatric Educator Excellence (APEX) Teaching Program. The American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/Committees-Councils-Sections/Section-on-Hospital-Medicine/Pages/Advancing-Pediatric-Educator-Excellence.aspx?nfstatus=401&nftoken=00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000&nfstatusdescription=ERROR:+No+local+token. Accessed August 22, 2016.

21. TEACH: Teaching Educators Across the Continuum of Healthcare. Society of General Internal Medicine. http://www.sgim.org/communities/education/sgim-teach-program. Accessed August 22, 2016.

22. Mittal V, Krieger E, Lee BC, et al. Pediatrics Residents’ Perspectives on Family-Centered Rounds: A Qualitative Study at 2 Children’s Hospitals. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):81-87. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-00314.1 PubMed

23. Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Patient- and Family-Centered Care and the Pediatrician’s Role. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394-404. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3084 PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine