User login

10 Strategies for Delivering a Great Presentation

It’s noon on Tuesday, and James, a new PGY-2 resident, begins his presentation on COPD. After five minutes, you notice half of the residents playing Words with Friends, the “ortho-bound” medical student talking with a buddy in the back, and the attendings looking on with innate skepticism.

Your talk on atrial fibrillation is next month, and just watching James brings on palpitations of your own. So what do you do?

Introduction

Public speaking is a near certainty for most of us regardless of training stage. A well-executed presentation establishes the clinician as an institutional authority, adroitly educating anyone around you.

So how can you deliver that killer update on atrial fibrillation? Here, we provide you with 10 tips for preparing and delivering a great presentation.

Preparation

1. Consider the audience and what they already know. No matter how interesting we think we are, if we don’t present with the audience’s needs in mind, we might as well be talking to an empty room. Consider what the audience may or may not know about the topic; this allows you to decide whether to give a comprehensive didactic on atrial fibrillation for trainees or an anticoagulation update for cardiologists. Great presenters survey their audience early on with a question such as, “How many of you here know the results of the AFFIRM trial?” This allows you to make small alterations to meet the needs of your audience.

2. Visualize the stage and setting. Understanding the stage helps you anticipate and address barriers to learning. Imagine for a moment the difference in these two scenarios: a discussion of hyponatremia with a group of medical students at 4 p.m. in a dark room versus a discussion on principles of atrial fibrillation management at 11 a.m. in an auditorium. Both require interaction, although an auditorium-based presentation requires testing your audio-visual equipment in advance.

3. Determine your objectives. To determine your objectives, begin with the end in mind. If you were to visualize your audience members at the end of the talk, what would they know (knowledge), be able to do (behavior), or have a new outlook on (attitude)? The objectives will determine the content you deliver and the activities for learning. For a one-hour presentation, identifying three to five objectives is a good rule of thumb.

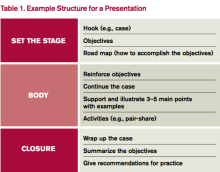

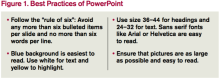

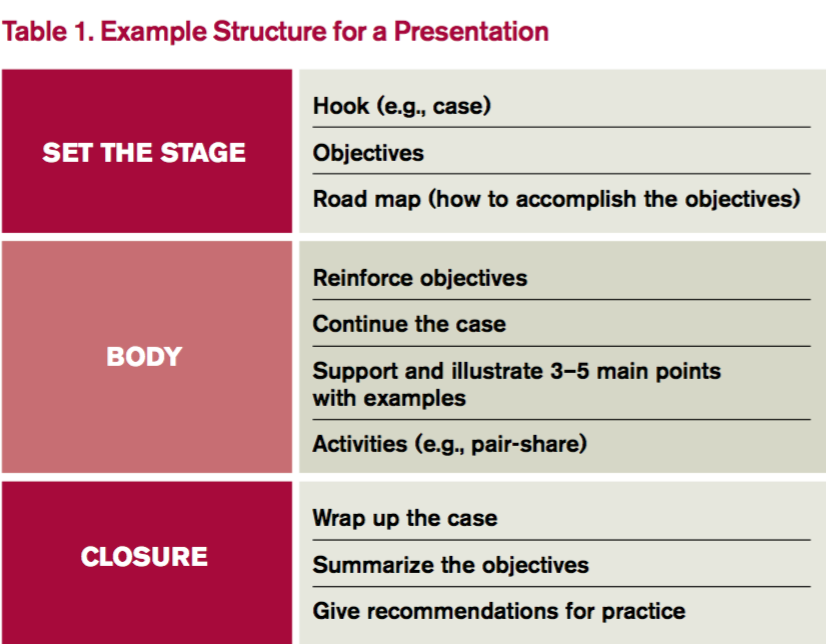

4. Build your presentation. Whether using PowerPoint, Prezi, or a white board, “build” the presentation from the objectives. Table 1 outlines one example format; Figure 1 outlines some best practices of PowerPoint.

Humans evolved to interpret visual imagery, not read text, so try to use pictures instead of bullet points. Consider first building slides with text and then using an internet search engine to convert words to pictures. For example, “atrial rate 200 bpm” is better displayed with an actual ECG.

5. Practice. Practicing helps you become more comfortable with the content itself as well as how to present that content. If you can, practice with a colleague and receive feedback to sharpen your material. No time to spare? Practice the introduction and any major point that you want to get across. Audiences decide within the first five minutes whether your talk is worth listening to before pulling out their cellphones to open up Facebook.

Delivery

1. Confront nervousness. Many of us become nervous when speaking in front of an audience. To address this, it’s perfectly reasonable to rehearse a presentation at home or in a quiet call room ahead of time. If you feel extremely nervous, breathe deeply for five- to 10-second intervals. During the presentation itself, find friendly or familiar faces in the audience and look them in the eyes as you speak. This eases nerves and improves your technique.

2. Hook your audience. The purpose of the hook is to “grab” the attention of the audience. The best presenters intrigue the audience with a story or problem at the outset and use the presentation to address that problem. Consider the differences in these openings:

- “As of 2010, atrial fibrillation has affected 33.5 million Americans each year, with a reported prevalence of stroke of 2.8% to 24.2%.”

- “Sarah is a 67-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation who loved to play the piano until she experienced a stroke, paralysis of her left arm, and the end of her career as a pianist. Today, I’m going to teach you how to reduce the risk of stroke in your patients with atrial fibrillation.”

Then as the presentation proceeds, develop the case to keep the audience thinking about their differential diagnosis or management strategy.

3. Speak clearly. We all use fillers such as “uh” and “um” without noticing. To learn to speak well, practice as much as possible and ask for feedback on your diction. Consider watching TED Talks, short clips of fascinating stories whose presenters are highly coached in public speaking. Use specific statements to key in the audience on important points, such as, “If you remember anything from this talk, I want you to remember …”

Remember, too, that public speaking requires enthusiasm. There’s nothing worse than beginning with, “I know that you all have heard about atrial fibrillation 500 times, so let’s just get through this.” The energy of the audience reflects the energy of the speaker.

4. Facilitate learning. Don’t do all of the talking; in fact, let the audience talk for you. For audience members to learn, they must engage with the material. Use a question/answer forum such as polleverywhere.com, where the audience responds in real time. Alternatively, pose a scenario to discuss using a pair-share technique. For a talk on atrial fibrillation, give direction to “turn to a neighbor and discuss anticoagulation for Mr. Jones, a 66-year-old man with cirrhosis, CVA, and hypertension admitted with atrial fibrillation.” Debrief this activity to solicit thoughts from the audience and then address the scenario.

5. Break the glass. Don’t hide behind the podium! “Breaking the glass” means stepping away from the podium to create an experience more akin to a dialogue. Remember, the audience is interested in hearing what you have to say—otherwise, they would have read about atrial fibrillation from UpToDate. Stepping away from the podium breaks the expected monotony and can help burn nervous energy.

Bottom Line

A fantastic presentation requires preparation and a thoughtful delivery. Spend the time to prepare. After all, that upcoming presentation on atrial fibrillation is only one month away. It will arrive sooner than you think. TH

Dr. Rendon is associate program director and Dr. Roesch is an assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of New Mexico Hospital in Albuquerque. They are co-directors of the medical student clinical reasoning course. Both are members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee.

References

- Anderson C. How to give a killer presentation. Harvard Business Review. June 2013.

- Covey C. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Franklin Covey Co.; 2004.

- Ganz L. Epidemiology of and risk factors for atrial fibrillation. Updated October 15, 2015.

- Sharpe B. How to give a great talk. Presented as part of SHM national conference; 2014; Las Vegas.

- Skeff K, Stratos G. Methods for Teaching Medicine. Philadelphia: ACP Press; 2010.

It’s noon on Tuesday, and James, a new PGY-2 resident, begins his presentation on COPD. After five minutes, you notice half of the residents playing Words with Friends, the “ortho-bound” medical student talking with a buddy in the back, and the attendings looking on with innate skepticism.

Your talk on atrial fibrillation is next month, and just watching James brings on palpitations of your own. So what do you do?

Introduction

Public speaking is a near certainty for most of us regardless of training stage. A well-executed presentation establishes the clinician as an institutional authority, adroitly educating anyone around you.

So how can you deliver that killer update on atrial fibrillation? Here, we provide you with 10 tips for preparing and delivering a great presentation.

Preparation

1. Consider the audience and what they already know. No matter how interesting we think we are, if we don’t present with the audience’s needs in mind, we might as well be talking to an empty room. Consider what the audience may or may not know about the topic; this allows you to decide whether to give a comprehensive didactic on atrial fibrillation for trainees or an anticoagulation update for cardiologists. Great presenters survey their audience early on with a question such as, “How many of you here know the results of the AFFIRM trial?” This allows you to make small alterations to meet the needs of your audience.

2. Visualize the stage and setting. Understanding the stage helps you anticipate and address barriers to learning. Imagine for a moment the difference in these two scenarios: a discussion of hyponatremia with a group of medical students at 4 p.m. in a dark room versus a discussion on principles of atrial fibrillation management at 11 a.m. in an auditorium. Both require interaction, although an auditorium-based presentation requires testing your audio-visual equipment in advance.

3. Determine your objectives. To determine your objectives, begin with the end in mind. If you were to visualize your audience members at the end of the talk, what would they know (knowledge), be able to do (behavior), or have a new outlook on (attitude)? The objectives will determine the content you deliver and the activities for learning. For a one-hour presentation, identifying three to five objectives is a good rule of thumb.

4. Build your presentation. Whether using PowerPoint, Prezi, or a white board, “build” the presentation from the objectives. Table 1 outlines one example format; Figure 1 outlines some best practices of PowerPoint.

Humans evolved to interpret visual imagery, not read text, so try to use pictures instead of bullet points. Consider first building slides with text and then using an internet search engine to convert words to pictures. For example, “atrial rate 200 bpm” is better displayed with an actual ECG.

5. Practice. Practicing helps you become more comfortable with the content itself as well as how to present that content. If you can, practice with a colleague and receive feedback to sharpen your material. No time to spare? Practice the introduction and any major point that you want to get across. Audiences decide within the first five minutes whether your talk is worth listening to before pulling out their cellphones to open up Facebook.

Delivery

1. Confront nervousness. Many of us become nervous when speaking in front of an audience. To address this, it’s perfectly reasonable to rehearse a presentation at home or in a quiet call room ahead of time. If you feel extremely nervous, breathe deeply for five- to 10-second intervals. During the presentation itself, find friendly or familiar faces in the audience and look them in the eyes as you speak. This eases nerves and improves your technique.

2. Hook your audience. The purpose of the hook is to “grab” the attention of the audience. The best presenters intrigue the audience with a story or problem at the outset and use the presentation to address that problem. Consider the differences in these openings:

- “As of 2010, atrial fibrillation has affected 33.5 million Americans each year, with a reported prevalence of stroke of 2.8% to 24.2%.”

- “Sarah is a 67-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation who loved to play the piano until she experienced a stroke, paralysis of her left arm, and the end of her career as a pianist. Today, I’m going to teach you how to reduce the risk of stroke in your patients with atrial fibrillation.”

Then as the presentation proceeds, develop the case to keep the audience thinking about their differential diagnosis or management strategy.

3. Speak clearly. We all use fillers such as “uh” and “um” without noticing. To learn to speak well, practice as much as possible and ask for feedback on your diction. Consider watching TED Talks, short clips of fascinating stories whose presenters are highly coached in public speaking. Use specific statements to key in the audience on important points, such as, “If you remember anything from this talk, I want you to remember …”

Remember, too, that public speaking requires enthusiasm. There’s nothing worse than beginning with, “I know that you all have heard about atrial fibrillation 500 times, so let’s just get through this.” The energy of the audience reflects the energy of the speaker.

4. Facilitate learning. Don’t do all of the talking; in fact, let the audience talk for you. For audience members to learn, they must engage with the material. Use a question/answer forum such as polleverywhere.com, where the audience responds in real time. Alternatively, pose a scenario to discuss using a pair-share technique. For a talk on atrial fibrillation, give direction to “turn to a neighbor and discuss anticoagulation for Mr. Jones, a 66-year-old man with cirrhosis, CVA, and hypertension admitted with atrial fibrillation.” Debrief this activity to solicit thoughts from the audience and then address the scenario.

5. Break the glass. Don’t hide behind the podium! “Breaking the glass” means stepping away from the podium to create an experience more akin to a dialogue. Remember, the audience is interested in hearing what you have to say—otherwise, they would have read about atrial fibrillation from UpToDate. Stepping away from the podium breaks the expected monotony and can help burn nervous energy.

Bottom Line

A fantastic presentation requires preparation and a thoughtful delivery. Spend the time to prepare. After all, that upcoming presentation on atrial fibrillation is only one month away. It will arrive sooner than you think. TH

Dr. Rendon is associate program director and Dr. Roesch is an assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of New Mexico Hospital in Albuquerque. They are co-directors of the medical student clinical reasoning course. Both are members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee.

References

- Anderson C. How to give a killer presentation. Harvard Business Review. June 2013.

- Covey C. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Franklin Covey Co.; 2004.

- Ganz L. Epidemiology of and risk factors for atrial fibrillation. Updated October 15, 2015.

- Sharpe B. How to give a great talk. Presented as part of SHM national conference; 2014; Las Vegas.

- Skeff K, Stratos G. Methods for Teaching Medicine. Philadelphia: ACP Press; 2010.

It’s noon on Tuesday, and James, a new PGY-2 resident, begins his presentation on COPD. After five minutes, you notice half of the residents playing Words with Friends, the “ortho-bound” medical student talking with a buddy in the back, and the attendings looking on with innate skepticism.

Your talk on atrial fibrillation is next month, and just watching James brings on palpitations of your own. So what do you do?

Introduction

Public speaking is a near certainty for most of us regardless of training stage. A well-executed presentation establishes the clinician as an institutional authority, adroitly educating anyone around you.

So how can you deliver that killer update on atrial fibrillation? Here, we provide you with 10 tips for preparing and delivering a great presentation.

Preparation

1. Consider the audience and what they already know. No matter how interesting we think we are, if we don’t present with the audience’s needs in mind, we might as well be talking to an empty room. Consider what the audience may or may not know about the topic; this allows you to decide whether to give a comprehensive didactic on atrial fibrillation for trainees or an anticoagulation update for cardiologists. Great presenters survey their audience early on with a question such as, “How many of you here know the results of the AFFIRM trial?” This allows you to make small alterations to meet the needs of your audience.

2. Visualize the stage and setting. Understanding the stage helps you anticipate and address barriers to learning. Imagine for a moment the difference in these two scenarios: a discussion of hyponatremia with a group of medical students at 4 p.m. in a dark room versus a discussion on principles of atrial fibrillation management at 11 a.m. in an auditorium. Both require interaction, although an auditorium-based presentation requires testing your audio-visual equipment in advance.

3. Determine your objectives. To determine your objectives, begin with the end in mind. If you were to visualize your audience members at the end of the talk, what would they know (knowledge), be able to do (behavior), or have a new outlook on (attitude)? The objectives will determine the content you deliver and the activities for learning. For a one-hour presentation, identifying three to five objectives is a good rule of thumb.

4. Build your presentation. Whether using PowerPoint, Prezi, or a white board, “build” the presentation from the objectives. Table 1 outlines one example format; Figure 1 outlines some best practices of PowerPoint.

Humans evolved to interpret visual imagery, not read text, so try to use pictures instead of bullet points. Consider first building slides with text and then using an internet search engine to convert words to pictures. For example, “atrial rate 200 bpm” is better displayed with an actual ECG.

5. Practice. Practicing helps you become more comfortable with the content itself as well as how to present that content. If you can, practice with a colleague and receive feedback to sharpen your material. No time to spare? Practice the introduction and any major point that you want to get across. Audiences decide within the first five minutes whether your talk is worth listening to before pulling out their cellphones to open up Facebook.

Delivery

1. Confront nervousness. Many of us become nervous when speaking in front of an audience. To address this, it’s perfectly reasonable to rehearse a presentation at home or in a quiet call room ahead of time. If you feel extremely nervous, breathe deeply for five- to 10-second intervals. During the presentation itself, find friendly or familiar faces in the audience and look them in the eyes as you speak. This eases nerves and improves your technique.

2. Hook your audience. The purpose of the hook is to “grab” the attention of the audience. The best presenters intrigue the audience with a story or problem at the outset and use the presentation to address that problem. Consider the differences in these openings:

- “As of 2010, atrial fibrillation has affected 33.5 million Americans each year, with a reported prevalence of stroke of 2.8% to 24.2%.”

- “Sarah is a 67-year-old woman with a history of atrial fibrillation who loved to play the piano until she experienced a stroke, paralysis of her left arm, and the end of her career as a pianist. Today, I’m going to teach you how to reduce the risk of stroke in your patients with atrial fibrillation.”

Then as the presentation proceeds, develop the case to keep the audience thinking about their differential diagnosis or management strategy.

3. Speak clearly. We all use fillers such as “uh” and “um” without noticing. To learn to speak well, practice as much as possible and ask for feedback on your diction. Consider watching TED Talks, short clips of fascinating stories whose presenters are highly coached in public speaking. Use specific statements to key in the audience on important points, such as, “If you remember anything from this talk, I want you to remember …”

Remember, too, that public speaking requires enthusiasm. There’s nothing worse than beginning with, “I know that you all have heard about atrial fibrillation 500 times, so let’s just get through this.” The energy of the audience reflects the energy of the speaker.

4. Facilitate learning. Don’t do all of the talking; in fact, let the audience talk for you. For audience members to learn, they must engage with the material. Use a question/answer forum such as polleverywhere.com, where the audience responds in real time. Alternatively, pose a scenario to discuss using a pair-share technique. For a talk on atrial fibrillation, give direction to “turn to a neighbor and discuss anticoagulation for Mr. Jones, a 66-year-old man with cirrhosis, CVA, and hypertension admitted with atrial fibrillation.” Debrief this activity to solicit thoughts from the audience and then address the scenario.

5. Break the glass. Don’t hide behind the podium! “Breaking the glass” means stepping away from the podium to create an experience more akin to a dialogue. Remember, the audience is interested in hearing what you have to say—otherwise, they would have read about atrial fibrillation from UpToDate. Stepping away from the podium breaks the expected monotony and can help burn nervous energy.

Bottom Line

A fantastic presentation requires preparation and a thoughtful delivery. Spend the time to prepare. After all, that upcoming presentation on atrial fibrillation is only one month away. It will arrive sooner than you think. TH

Dr. Rendon is associate program director and Dr. Roesch is an assistant professor in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of New Mexico Hospital in Albuquerque. They are co-directors of the medical student clinical reasoning course. Both are members of SHM’s Physicians in Training Committee.

References

- Anderson C. How to give a killer presentation. Harvard Business Review. June 2013.

- Covey C. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Franklin Covey Co.; 2004.

- Ganz L. Epidemiology of and risk factors for atrial fibrillation. Updated October 15, 2015.

- Sharpe B. How to give a great talk. Presented as part of SHM national conference; 2014; Las Vegas.

- Skeff K, Stratos G. Methods for Teaching Medicine. Philadelphia: ACP Press; 2010.

10 Questions You Should Consider for Specialist Consultations

Caring for patients in the inpatient setting is complex and often requires consultation from specialists. Yet the actual skill of obtaining a consult is rarely taught. Medical students and residents usually learn by trial and error, becoming targets of frustrated consultants and suffering humiliation and much anxiety. To facilitate communication between the primary team and the specialist, we propose that the student and/or resident start by asking the following questions.

1. Why Call This Consult?

To decide whether you need a consult, first determine the type. Consultations can be broken down into three different types: advice on diagnosis, advice on management, or arrangements for a specific procedure or test. Advice on diagnosis or management is typically required when a clinical issue has reached the bounds of knowledge, experience, or comfort zone of the team or physician (e.g., idiopathic leukocytosis). For procedures, a consultant who is licensed to perform the procedure may be required (e.g., endoscopy for GI bleed).

2. What Should Be Done before a Consult Is Requested?

First, ask yourself, “If I were the consultant, what would I want to know?” Before calling, put yourself in the shoes of the consultant and consider the available data carefully to develop your own hypotheses. For example, infectious disease consultants typically make judgments based on relevant culture data, current and/or past antibiotics, imaging, and signs or symptoms of active infection. Reading about the problem beforehand allows you to anticipate possible questions and consider additional studies that may be requested by the consultant. It also helps ascertain whether the consultation is actually necessary or targeted to the right team.

3. What Is the Clinical Question?

Bergus and colleagues found that a well-structured clinical question clearly identifies the treatment the primary doctor is proposing and the desired outcomes for the patient.1 For instance, rather than asking, “What should we do for this 75-year-old man with chest pain?”, a better question might be, “Will the addition of ranolazine increase exercise tolerance in our 75-year-old man with angina who is already taking a beta blocker and nitrates?” When both components are present, clinical questions are more likely to be answered.

4. How Do I Best Present the Case to My Consultant?

Requesting a consultation requires a succinct presentation that focuses on the aspects of the case most pertinent to the specialist. To do this, again put yourself in the shoes of the consultant. For example, a patient’s history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) will always be relevant to a hematologist, whereas a history of GERD may not be needed in your initial conversation. Limit the initial presentation to two to three minutes and organize using the four I’s:

- Introduction: “My name is X with blue medicine team; I am calling to request a consult.”

- Information: Patient name, location, medical record number, attending physician.

- Inquiry: “I am requesting evaluation for an EGD in a patient with an upper GI bleed.”

- Important items (the story): “Mr. X is a 55-year-old male with history of peptic ulcer disease presenting with abdominal pain.”

5. What Data Requests Should I Anticipate?

Have your clinical data easily accessible in case additional information is requested (i.e., keep the chart open when calling). If certain tests are predictably going to be needed by the specialist (e.g., renal ultrasound for a nephrologist), make sure that the results are available or in process. Also, be prepared to take notes if the consultant requests additional tests up front.

6. How Urgent Is the Consult?

Consultations can be emergent, urgent, or elective. Directly communicate any emergent or urgent consults in order to clarify the issues expeditiously. For more routine consults, consider delaying the call until enough laboratory data or imaging is available for the consultant to answer the question. Do not call a nonurgent consult at the end of the day or on a weekend.

7. Where Can I Meet with the Consultant to Discuss the Case?

Be available to your consultants by offering the fastest and most reliable means for them to get in touch with you. Take advantage of your consultants and learn from them. Be where they are: If looking at the blood smear, join them. If spinning the urine, ask to examine the sediment together. Discussing the case in person demonstrates your interest, engendering a more serious and perhaps expeditious consideration of your case. Finally, request seminal articles that have driven their decision to allow for more intelligent conversations in the future.

8. How Can I Nurture My Relationship with the Consulting Team?

The best relationships with consultants require give-and-take. Be a reliable source by providing accurate documentation of ongoing events, history and physical examination, and laboratory data in your notes. Understand consultant recommendations and summarize these in your plan. Avoid “Plan per Renal/GI/Cards/Heme, etc.” in your notes. Continue to think about the questions and issues and read on your own. If you are unclear about the recommendations, clarify them with the consulting team. Speaking with consultants is a learning opportunity; never forget to ask why they have made a certain recommendation. Avoid “chart wars” if there are points of disagreement with the plan or recommendations.

9. How Do I Close the Loop on the Consult?

Closing the communication loop is one of the most important aspects of the consult because it allows you to act on the recommendations. Remember that consultants are likely to be as busy as you are (if not busier). If the consult was urgent, call consultants directly for guidance. If it wasn’t urgent, look in the chart first for their note. Checking the chart later in the day could help to avoid unnecessary phone calls and increase your efficiency.

10. Am I Sure I Want a Curbside Consult?

In a curbside consult, you request advice of an expert who is neither in the presence of the patients nor has a therapeutic relationship with them. A study by Burden and colleagues in 2013 found that 55% of physicians offered different advice in formal consultation than in a curbside consultation, and 60% felt that formal consultation changed management.2 Similarly, Kuo and colleagues noted that 77% of subspecialists reported that important clinical findings were frequently missing from curbsides.3 Some recommend limiting curbsides to simple questions that don’t require consultants to assess multiple variables; as a courtesy, consider offering them the option of a formal consult. Ultimately, the decision to request a curbside consultation, and any consultation for that matter, should always be discussed with your attending physician.

Conclusion

Effective communication with consultants requires forethought and is an exercise in clinical reasoning of great educational value to students and residents. By considering the questions above, the consultative experience can be more productive for both the primary and consulting team and will enhance the care of the hospitalized patient. TH

Dr. Esquivel is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr. Rendon is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque.

References

1. Bergus GR, Randall CS, Sinift SD, Rosenthal DM. Does the structure of clinical questions affect the outcome of curbside consultations with specialty colleagues? Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(6):541-547.

2. Burden M, Sarcone E, Keniston A, et al. Prospective comparison of curbside versus formal consultations. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(1):31-35.

3. Kuo D, Gifford DR, Stein MD. Curbside consultation practices and attitudes among primary care physicians and medical subspecialists. JAMA. 1998;280(10):905-909.

Caring for patients in the inpatient setting is complex and often requires consultation from specialists. Yet the actual skill of obtaining a consult is rarely taught. Medical students and residents usually learn by trial and error, becoming targets of frustrated consultants and suffering humiliation and much anxiety. To facilitate communication between the primary team and the specialist, we propose that the student and/or resident start by asking the following questions.

1. Why Call This Consult?

To decide whether you need a consult, first determine the type. Consultations can be broken down into three different types: advice on diagnosis, advice on management, or arrangements for a specific procedure or test. Advice on diagnosis or management is typically required when a clinical issue has reached the bounds of knowledge, experience, or comfort zone of the team or physician (e.g., idiopathic leukocytosis). For procedures, a consultant who is licensed to perform the procedure may be required (e.g., endoscopy for GI bleed).

2. What Should Be Done before a Consult Is Requested?

First, ask yourself, “If I were the consultant, what would I want to know?” Before calling, put yourself in the shoes of the consultant and consider the available data carefully to develop your own hypotheses. For example, infectious disease consultants typically make judgments based on relevant culture data, current and/or past antibiotics, imaging, and signs or symptoms of active infection. Reading about the problem beforehand allows you to anticipate possible questions and consider additional studies that may be requested by the consultant. It also helps ascertain whether the consultation is actually necessary or targeted to the right team.

3. What Is the Clinical Question?

Bergus and colleagues found that a well-structured clinical question clearly identifies the treatment the primary doctor is proposing and the desired outcomes for the patient.1 For instance, rather than asking, “What should we do for this 75-year-old man with chest pain?”, a better question might be, “Will the addition of ranolazine increase exercise tolerance in our 75-year-old man with angina who is already taking a beta blocker and nitrates?” When both components are present, clinical questions are more likely to be answered.

4. How Do I Best Present the Case to My Consultant?

Requesting a consultation requires a succinct presentation that focuses on the aspects of the case most pertinent to the specialist. To do this, again put yourself in the shoes of the consultant. For example, a patient’s history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) will always be relevant to a hematologist, whereas a history of GERD may not be needed in your initial conversation. Limit the initial presentation to two to three minutes and organize using the four I’s:

- Introduction: “My name is X with blue medicine team; I am calling to request a consult.”

- Information: Patient name, location, medical record number, attending physician.

- Inquiry: “I am requesting evaluation for an EGD in a patient with an upper GI bleed.”

- Important items (the story): “Mr. X is a 55-year-old male with history of peptic ulcer disease presenting with abdominal pain.”

5. What Data Requests Should I Anticipate?

Have your clinical data easily accessible in case additional information is requested (i.e., keep the chart open when calling). If certain tests are predictably going to be needed by the specialist (e.g., renal ultrasound for a nephrologist), make sure that the results are available or in process. Also, be prepared to take notes if the consultant requests additional tests up front.

6. How Urgent Is the Consult?

Consultations can be emergent, urgent, or elective. Directly communicate any emergent or urgent consults in order to clarify the issues expeditiously. For more routine consults, consider delaying the call until enough laboratory data or imaging is available for the consultant to answer the question. Do not call a nonurgent consult at the end of the day or on a weekend.

7. Where Can I Meet with the Consultant to Discuss the Case?

Be available to your consultants by offering the fastest and most reliable means for them to get in touch with you. Take advantage of your consultants and learn from them. Be where they are: If looking at the blood smear, join them. If spinning the urine, ask to examine the sediment together. Discussing the case in person demonstrates your interest, engendering a more serious and perhaps expeditious consideration of your case. Finally, request seminal articles that have driven their decision to allow for more intelligent conversations in the future.

8. How Can I Nurture My Relationship with the Consulting Team?

The best relationships with consultants require give-and-take. Be a reliable source by providing accurate documentation of ongoing events, history and physical examination, and laboratory data in your notes. Understand consultant recommendations and summarize these in your plan. Avoid “Plan per Renal/GI/Cards/Heme, etc.” in your notes. Continue to think about the questions and issues and read on your own. If you are unclear about the recommendations, clarify them with the consulting team. Speaking with consultants is a learning opportunity; never forget to ask why they have made a certain recommendation. Avoid “chart wars” if there are points of disagreement with the plan or recommendations.

9. How Do I Close the Loop on the Consult?

Closing the communication loop is one of the most important aspects of the consult because it allows you to act on the recommendations. Remember that consultants are likely to be as busy as you are (if not busier). If the consult was urgent, call consultants directly for guidance. If it wasn’t urgent, look in the chart first for their note. Checking the chart later in the day could help to avoid unnecessary phone calls and increase your efficiency.

10. Am I Sure I Want a Curbside Consult?

In a curbside consult, you request advice of an expert who is neither in the presence of the patients nor has a therapeutic relationship with them. A study by Burden and colleagues in 2013 found that 55% of physicians offered different advice in formal consultation than in a curbside consultation, and 60% felt that formal consultation changed management.2 Similarly, Kuo and colleagues noted that 77% of subspecialists reported that important clinical findings were frequently missing from curbsides.3 Some recommend limiting curbsides to simple questions that don’t require consultants to assess multiple variables; as a courtesy, consider offering them the option of a formal consult. Ultimately, the decision to request a curbside consultation, and any consultation for that matter, should always be discussed with your attending physician.

Conclusion

Effective communication with consultants requires forethought and is an exercise in clinical reasoning of great educational value to students and residents. By considering the questions above, the consultative experience can be more productive for both the primary and consulting team and will enhance the care of the hospitalized patient. TH

Dr. Esquivel is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr. Rendon is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque.

References

1. Bergus GR, Randall CS, Sinift SD, Rosenthal DM. Does the structure of clinical questions affect the outcome of curbside consultations with specialty colleagues? Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(6):541-547.

2. Burden M, Sarcone E, Keniston A, et al. Prospective comparison of curbside versus formal consultations. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(1):31-35.

3. Kuo D, Gifford DR, Stein MD. Curbside consultation practices and attitudes among primary care physicians and medical subspecialists. JAMA. 1998;280(10):905-909.

Caring for patients in the inpatient setting is complex and often requires consultation from specialists. Yet the actual skill of obtaining a consult is rarely taught. Medical students and residents usually learn by trial and error, becoming targets of frustrated consultants and suffering humiliation and much anxiety. To facilitate communication between the primary team and the specialist, we propose that the student and/or resident start by asking the following questions.

1. Why Call This Consult?

To decide whether you need a consult, first determine the type. Consultations can be broken down into three different types: advice on diagnosis, advice on management, or arrangements for a specific procedure or test. Advice on diagnosis or management is typically required when a clinical issue has reached the bounds of knowledge, experience, or comfort zone of the team or physician (e.g., idiopathic leukocytosis). For procedures, a consultant who is licensed to perform the procedure may be required (e.g., endoscopy for GI bleed).

2. What Should Be Done before a Consult Is Requested?

First, ask yourself, “If I were the consultant, what would I want to know?” Before calling, put yourself in the shoes of the consultant and consider the available data carefully to develop your own hypotheses. For example, infectious disease consultants typically make judgments based on relevant culture data, current and/or past antibiotics, imaging, and signs or symptoms of active infection. Reading about the problem beforehand allows you to anticipate possible questions and consider additional studies that may be requested by the consultant. It also helps ascertain whether the consultation is actually necessary or targeted to the right team.

3. What Is the Clinical Question?

Bergus and colleagues found that a well-structured clinical question clearly identifies the treatment the primary doctor is proposing and the desired outcomes for the patient.1 For instance, rather than asking, “What should we do for this 75-year-old man with chest pain?”, a better question might be, “Will the addition of ranolazine increase exercise tolerance in our 75-year-old man with angina who is already taking a beta blocker and nitrates?” When both components are present, clinical questions are more likely to be answered.

4. How Do I Best Present the Case to My Consultant?

Requesting a consultation requires a succinct presentation that focuses on the aspects of the case most pertinent to the specialist. To do this, again put yourself in the shoes of the consultant. For example, a patient’s history of venous thromboembolism (VTE) will always be relevant to a hematologist, whereas a history of GERD may not be needed in your initial conversation. Limit the initial presentation to two to three minutes and organize using the four I’s:

- Introduction: “My name is X with blue medicine team; I am calling to request a consult.”

- Information: Patient name, location, medical record number, attending physician.

- Inquiry: “I am requesting evaluation for an EGD in a patient with an upper GI bleed.”

- Important items (the story): “Mr. X is a 55-year-old male with history of peptic ulcer disease presenting with abdominal pain.”

5. What Data Requests Should I Anticipate?

Have your clinical data easily accessible in case additional information is requested (i.e., keep the chart open when calling). If certain tests are predictably going to be needed by the specialist (e.g., renal ultrasound for a nephrologist), make sure that the results are available or in process. Also, be prepared to take notes if the consultant requests additional tests up front.

6. How Urgent Is the Consult?

Consultations can be emergent, urgent, or elective. Directly communicate any emergent or urgent consults in order to clarify the issues expeditiously. For more routine consults, consider delaying the call until enough laboratory data or imaging is available for the consultant to answer the question. Do not call a nonurgent consult at the end of the day or on a weekend.

7. Where Can I Meet with the Consultant to Discuss the Case?

Be available to your consultants by offering the fastest and most reliable means for them to get in touch with you. Take advantage of your consultants and learn from them. Be where they are: If looking at the blood smear, join them. If spinning the urine, ask to examine the sediment together. Discussing the case in person demonstrates your interest, engendering a more serious and perhaps expeditious consideration of your case. Finally, request seminal articles that have driven their decision to allow for more intelligent conversations in the future.

8. How Can I Nurture My Relationship with the Consulting Team?

The best relationships with consultants require give-and-take. Be a reliable source by providing accurate documentation of ongoing events, history and physical examination, and laboratory data in your notes. Understand consultant recommendations and summarize these in your plan. Avoid “Plan per Renal/GI/Cards/Heme, etc.” in your notes. Continue to think about the questions and issues and read on your own. If you are unclear about the recommendations, clarify them with the consulting team. Speaking with consultants is a learning opportunity; never forget to ask why they have made a certain recommendation. Avoid “chart wars” if there are points of disagreement with the plan or recommendations.

9. How Do I Close the Loop on the Consult?

Closing the communication loop is one of the most important aspects of the consult because it allows you to act on the recommendations. Remember that consultants are likely to be as busy as you are (if not busier). If the consult was urgent, call consultants directly for guidance. If it wasn’t urgent, look in the chart first for their note. Checking the chart later in the day could help to avoid unnecessary phone calls and increase your efficiency.

10. Am I Sure I Want a Curbside Consult?

In a curbside consult, you request advice of an expert who is neither in the presence of the patients nor has a therapeutic relationship with them. A study by Burden and colleagues in 2013 found that 55% of physicians offered different advice in formal consultation than in a curbside consultation, and 60% felt that formal consultation changed management.2 Similarly, Kuo and colleagues noted that 77% of subspecialists reported that important clinical findings were frequently missing from curbsides.3 Some recommend limiting curbsides to simple questions that don’t require consultants to assess multiple variables; as a courtesy, consider offering them the option of a formal consult. Ultimately, the decision to request a curbside consultation, and any consultation for that matter, should always be discussed with your attending physician.

Conclusion

Effective communication with consultants requires forethought and is an exercise in clinical reasoning of great educational value to students and residents. By considering the questions above, the consultative experience can be more productive for both the primary and consulting team and will enhance the care of the hospitalized patient. TH

Dr. Esquivel is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr. Rendon is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque.

References

1. Bergus GR, Randall CS, Sinift SD, Rosenthal DM. Does the structure of clinical questions affect the outcome of curbside consultations with specialty colleagues? Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(6):541-547.

2. Burden M, Sarcone E, Keniston A, et al. Prospective comparison of curbside versus formal consultations. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(1):31-35.

3. Kuo D, Gifford DR, Stein MD. Curbside consultation practices and attitudes among primary care physicians and medical subspecialists. JAMA. 1998;280(10):905-909.