User login

Improving Patient Safety and Quality of Care

Patient safety and improved quality of care have become priority issues in the American healthcare system. The potential for medical errors was highlighted in 1999 when the Quality of Health Care in America Committee of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its first report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The committee estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 people die annually from inpatient medical errors. The eighth leading cause of death in this country, preventable medical errors, cost the U.S. approximately $17 billion annually in direct and indirect costs (IOM). These alarming statistics in the IOM report ignited the patient safety movement (I).

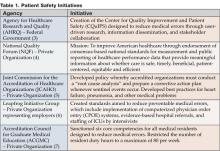

The IOM report made a series of recommendations that included the creation of a center for patient safety, the development of a national public reporting system, the establishment of oversight agencies, and the incorporation of safety principles into monitoring systems. Public and private agencies have responded with a series of initiatives that address these recommendations (See Table 1).

One healthcare expert describes three reasons as to why the potential for medical errors has increased. First, technology has created a sophisticated array of test, x-rays, laboratory procedures, and diagnostic tools. Second, pharmaceutical research has introduced thousands of new medications to the marketplace. Finally, specialization has led to experts, both physician and non-physician, in a wide range of body systems, diseases, settings, procedures, and therapies. Hospital medicine represents a new type of medical specialty that has the potential to address this increased complexity and sophistication and to improve patient care in the hospital inpatient environment (2).

Hospitalists as Team Coordinators

To achieve maximum positive outcomes in the complex inpatient environment, a qualified coordinator must educate others and facilitate activity revolving around patient care. Hospitalists as inpatient experts possess the necessary qualifications to integrate hospital systems and maximize efforts to enhance patient safety by monitoring medication distribution, chairing pharmaceuticals and therapeutics (P&T) committees, overseeing computerized physician order entry (CPOE), directing quality/performance improvement projects, and collaborating with discharge planning and case management.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, is vice chair of the department of Internal Medicine at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Michigan and chairperson of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee. She says, Hospitalists have a ‘lens of understanding the systems under which they care for patients.’ They take care of patients in the hospital every single day so they can examine the processes with which they work. Hospitalists have an ideal perspective from which to reform ineffective systems.”

In spite of all the guidelines established by federal agencies and expert groups, Dr. Halasyamani points out that implementation barriers exist that prevent well-intentioned protocols and best practices from being carried out. Part of the challenge is the performance of a critical piece of the infrastructure—the multidisciplinary team. The very nature of healthcare demands an inherent need to coordinate and communicate. “Treating the patient is not the responsibility of one single individual,” says Halasyamani. “This is a team effort. The hospitalist recognizes that he is part of that team.” By elevating the ideals of teamwork, hospitalists can deliver to the patients the essential care that patients need, both while in the hospital and after they are discharged. In managing hospital inpatients, physicians must cope with high intensity of illness, pressures to reduce length of stay (LOS), and the coordination of handoffs among many specialists. According to Halasyamani, this can be a “recipe for disaster.”

Halasyamani acknowledges the vital role of protocols in reducing medical errors and improving quality of care. The training, education, and experience a hospitalist has acquired enables him to optimize communication and implement protocols, thus facilitating the practice of delivering safe and consistent care to all patients. In fact, with this smaller core group of inpatient physicians, the development and implementation of protocols can potentially be more effective because it targets a smaller group of physicians than the traditional inpatient model (8).

Kaveh C. Shojania, MD, is assistant professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa and co-author of Internal Bleeding: The Terrifying Truth Behind America's Epidemic Medical Mistakes. He points out that the current inpatient medical landscape involves a significant number of clinicians who practice at the hospital but not all their activity is centered there. “From a clinical perspective, no one has ownership,” he says. “On the other hand, hospitalists are based in a single hospital and have a vested interest in that particular hospital.” Typically generalists, hospitalists tend to interact with all specialists and therefore have a good sense of all interests.

Medical errors occur most often during transition times, from the ICU to the floor or from inpatient to outpatient status. There is the potential for a loss of clinical information during these transfers. According to Shojania, a significant portion of the hospitalist’s time is spent managing these transitions and overseeing patients as they are relocated from floor to floor and discharge to home, rehabilitation facility, or nursing home. He notes that the regulatory agencies have begun to acknowledge the importance of hospitalists. “The JCAHO (Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) recognizes hospitalists as a resource because they are always in the hospital and have a vested interest,” he says (9).

Stakeholder Analysis

Patients stand to gain the most benefit from hospitalists insofar as safety and quality of care is concerned. Through the efforts and oversight of hospitalists, patients may experience reduced medical errors and lower mortality rates. For primary care physicians and hospitals, this lower rate of medical error means fewer medical malpractice cases, the potential for lower insurance premiums and, as a result, enhanced reputations. When hospitals are run more efficiently and provide a greater sense of trust and efficient management practices, society in general becomes the benefactor.

Clinical Trials

To date, few research studies measuring the impact of hospitalists on patient safety and quality of care have been conducted. Quality of care has been assessed largely through the surrogate markers of mortality and readmission rates. One study showed decreased in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates for hospitalist patients (10), and another indicated a decrease in 30-day readmission rates (11).

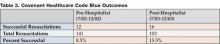

In addition, data from individual programs demonstrate positive findings. For example, Stacy Goldsholl, MD, medical director of the Covenant Healthcare hospital medicine program in Michigan, reports a 17% decrease in the expected mortality rate in the first year of the hospital medicine program. The information was drawn from the Michigan Hospital Association (MHA) databank and matched for severity and diagnosis (See Table 2). “This was significant when compared to the internal medicine comparison group with similar case mix index (CMI),” says Goldsholl. “In the first half of our second year, we have demonstrated a 46% decrease in expected mortality, while internal medicine had a 4% increase” (12).

Additionally, Goldsholl reports that Covenant initiated a Code Blue and emergency consult service to improve patient outcome and experienced a marked increase in efficiency. Table 3 represents elementary data collected during the first 6 months pre- and post-initiation of the hospital medicine program at Covenant (12).

Conclusion

Patient safety and quality of care in the hospital require a team of dedicated people to effect change. Orchestrating the team effectively is the responsibility of an attending physician. With the numerous “handoffs” that take place during hospitalization, the potential for medical errors increases exponentially. Federal mandates requiring the conversion to electronic medical records, which includes basic health information as well as critical data regarding medications, procedures, and surgeries, further complicates efficient and safe patient management. According to Robert Wachter, “Those doctors with the best outcomes were those who tended to treat similar patients with similar problems using similar techniques.” By definition, the hospitalist is a “physician who focuses his practice on the care, coordination, and safety of hospitalized patients.” Who better to stand at the center of the issue of reduced medical errors, improved patient care, and enhanced quality of care than hospitalists (13)?

Dr. Pak can be contacted at mhp@medicine.wisc.edu.

References

- To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, Institute of Medicine, November 1999.

- Wachter R. The end of the beginning: patient safety five years after ‘To Err Is Human.’ Health Affairs. November 30, 2004.

- Mission Statement: Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety. February 2004. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.ahrq.gov/about/cquips/cquipsmiss.htm.

- Safe Practices for Better Healthcare: a Consensus. The National Quality Forum, 2003.

- Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), www.jcaho.org.

- Leapfrog Group, www.leapfroggroup.org.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), www.acgme.org.

- Halasyamani L. Telephone interview. February 7, 2005.

- Shojania KG. Assistant professor of medicine, University of Ottawa. Telephone interview. January 31, 2005.

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P. et al. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:859-65.

- Kulaga ME, Charney P, O’Mahoney SP, et al. The positive impact of initiation of hospitalist clinician educators. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:293-301.

- Goldsholl S. Medical director. Covenant Healthcare hospital medicine program, Saginaw, Michigan, email interview. January 31, 2005.

- Wachter R, Shojania K. Internal bleeding: the truth behind America’s terrifying epidemic of medical mistakes. Rugged Land, LLC, 2004.

Patient safety and improved quality of care have become priority issues in the American healthcare system. The potential for medical errors was highlighted in 1999 when the Quality of Health Care in America Committee of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its first report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The committee estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 people die annually from inpatient medical errors. The eighth leading cause of death in this country, preventable medical errors, cost the U.S. approximately $17 billion annually in direct and indirect costs (IOM). These alarming statistics in the IOM report ignited the patient safety movement (I).

The IOM report made a series of recommendations that included the creation of a center for patient safety, the development of a national public reporting system, the establishment of oversight agencies, and the incorporation of safety principles into monitoring systems. Public and private agencies have responded with a series of initiatives that address these recommendations (See Table 1).

One healthcare expert describes three reasons as to why the potential for medical errors has increased. First, technology has created a sophisticated array of test, x-rays, laboratory procedures, and diagnostic tools. Second, pharmaceutical research has introduced thousands of new medications to the marketplace. Finally, specialization has led to experts, both physician and non-physician, in a wide range of body systems, diseases, settings, procedures, and therapies. Hospital medicine represents a new type of medical specialty that has the potential to address this increased complexity and sophistication and to improve patient care in the hospital inpatient environment (2).

Hospitalists as Team Coordinators

To achieve maximum positive outcomes in the complex inpatient environment, a qualified coordinator must educate others and facilitate activity revolving around patient care. Hospitalists as inpatient experts possess the necessary qualifications to integrate hospital systems and maximize efforts to enhance patient safety by monitoring medication distribution, chairing pharmaceuticals and therapeutics (P&T) committees, overseeing computerized physician order entry (CPOE), directing quality/performance improvement projects, and collaborating with discharge planning and case management.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, is vice chair of the department of Internal Medicine at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Michigan and chairperson of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee. She says, Hospitalists have a ‘lens of understanding the systems under which they care for patients.’ They take care of patients in the hospital every single day so they can examine the processes with which they work. Hospitalists have an ideal perspective from which to reform ineffective systems.”

In spite of all the guidelines established by federal agencies and expert groups, Dr. Halasyamani points out that implementation barriers exist that prevent well-intentioned protocols and best practices from being carried out. Part of the challenge is the performance of a critical piece of the infrastructure—the multidisciplinary team. The very nature of healthcare demands an inherent need to coordinate and communicate. “Treating the patient is not the responsibility of one single individual,” says Halasyamani. “This is a team effort. The hospitalist recognizes that he is part of that team.” By elevating the ideals of teamwork, hospitalists can deliver to the patients the essential care that patients need, both while in the hospital and after they are discharged. In managing hospital inpatients, physicians must cope with high intensity of illness, pressures to reduce length of stay (LOS), and the coordination of handoffs among many specialists. According to Halasyamani, this can be a “recipe for disaster.”

Halasyamani acknowledges the vital role of protocols in reducing medical errors and improving quality of care. The training, education, and experience a hospitalist has acquired enables him to optimize communication and implement protocols, thus facilitating the practice of delivering safe and consistent care to all patients. In fact, with this smaller core group of inpatient physicians, the development and implementation of protocols can potentially be more effective because it targets a smaller group of physicians than the traditional inpatient model (8).

Kaveh C. Shojania, MD, is assistant professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa and co-author of Internal Bleeding: The Terrifying Truth Behind America's Epidemic Medical Mistakes. He points out that the current inpatient medical landscape involves a significant number of clinicians who practice at the hospital but not all their activity is centered there. “From a clinical perspective, no one has ownership,” he says. “On the other hand, hospitalists are based in a single hospital and have a vested interest in that particular hospital.” Typically generalists, hospitalists tend to interact with all specialists and therefore have a good sense of all interests.

Medical errors occur most often during transition times, from the ICU to the floor or from inpatient to outpatient status. There is the potential for a loss of clinical information during these transfers. According to Shojania, a significant portion of the hospitalist’s time is spent managing these transitions and overseeing patients as they are relocated from floor to floor and discharge to home, rehabilitation facility, or nursing home. He notes that the regulatory agencies have begun to acknowledge the importance of hospitalists. “The JCAHO (Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) recognizes hospitalists as a resource because they are always in the hospital and have a vested interest,” he says (9).

Stakeholder Analysis

Patients stand to gain the most benefit from hospitalists insofar as safety and quality of care is concerned. Through the efforts and oversight of hospitalists, patients may experience reduced medical errors and lower mortality rates. For primary care physicians and hospitals, this lower rate of medical error means fewer medical malpractice cases, the potential for lower insurance premiums and, as a result, enhanced reputations. When hospitals are run more efficiently and provide a greater sense of trust and efficient management practices, society in general becomes the benefactor.

Clinical Trials

To date, few research studies measuring the impact of hospitalists on patient safety and quality of care have been conducted. Quality of care has been assessed largely through the surrogate markers of mortality and readmission rates. One study showed decreased in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates for hospitalist patients (10), and another indicated a decrease in 30-day readmission rates (11).

In addition, data from individual programs demonstrate positive findings. For example, Stacy Goldsholl, MD, medical director of the Covenant Healthcare hospital medicine program in Michigan, reports a 17% decrease in the expected mortality rate in the first year of the hospital medicine program. The information was drawn from the Michigan Hospital Association (MHA) databank and matched for severity and diagnosis (See Table 2). “This was significant when compared to the internal medicine comparison group with similar case mix index (CMI),” says Goldsholl. “In the first half of our second year, we have demonstrated a 46% decrease in expected mortality, while internal medicine had a 4% increase” (12).

Additionally, Goldsholl reports that Covenant initiated a Code Blue and emergency consult service to improve patient outcome and experienced a marked increase in efficiency. Table 3 represents elementary data collected during the first 6 months pre- and post-initiation of the hospital medicine program at Covenant (12).

Conclusion

Patient safety and quality of care in the hospital require a team of dedicated people to effect change. Orchestrating the team effectively is the responsibility of an attending physician. With the numerous “handoffs” that take place during hospitalization, the potential for medical errors increases exponentially. Federal mandates requiring the conversion to electronic medical records, which includes basic health information as well as critical data regarding medications, procedures, and surgeries, further complicates efficient and safe patient management. According to Robert Wachter, “Those doctors with the best outcomes were those who tended to treat similar patients with similar problems using similar techniques.” By definition, the hospitalist is a “physician who focuses his practice on the care, coordination, and safety of hospitalized patients.” Who better to stand at the center of the issue of reduced medical errors, improved patient care, and enhanced quality of care than hospitalists (13)?

Dr. Pak can be contacted at mhp@medicine.wisc.edu.

References

- To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, Institute of Medicine, November 1999.

- Wachter R. The end of the beginning: patient safety five years after ‘To Err Is Human.’ Health Affairs. November 30, 2004.

- Mission Statement: Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety. February 2004. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.ahrq.gov/about/cquips/cquipsmiss.htm.

- Safe Practices for Better Healthcare: a Consensus. The National Quality Forum, 2003.

- Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), www.jcaho.org.

- Leapfrog Group, www.leapfroggroup.org.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), www.acgme.org.

- Halasyamani L. Telephone interview. February 7, 2005.

- Shojania KG. Assistant professor of medicine, University of Ottawa. Telephone interview. January 31, 2005.

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P. et al. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:859-65.

- Kulaga ME, Charney P, O’Mahoney SP, et al. The positive impact of initiation of hospitalist clinician educators. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:293-301.

- Goldsholl S. Medical director. Covenant Healthcare hospital medicine program, Saginaw, Michigan, email interview. January 31, 2005.

- Wachter R, Shojania K. Internal bleeding: the truth behind America’s terrifying epidemic of medical mistakes. Rugged Land, LLC, 2004.

Patient safety and improved quality of care have become priority issues in the American healthcare system. The potential for medical errors was highlighted in 1999 when the Quality of Health Care in America Committee of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its first report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. The committee estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 people die annually from inpatient medical errors. The eighth leading cause of death in this country, preventable medical errors, cost the U.S. approximately $17 billion annually in direct and indirect costs (IOM). These alarming statistics in the IOM report ignited the patient safety movement (I).

The IOM report made a series of recommendations that included the creation of a center for patient safety, the development of a national public reporting system, the establishment of oversight agencies, and the incorporation of safety principles into monitoring systems. Public and private agencies have responded with a series of initiatives that address these recommendations (See Table 1).

One healthcare expert describes three reasons as to why the potential for medical errors has increased. First, technology has created a sophisticated array of test, x-rays, laboratory procedures, and diagnostic tools. Second, pharmaceutical research has introduced thousands of new medications to the marketplace. Finally, specialization has led to experts, both physician and non-physician, in a wide range of body systems, diseases, settings, procedures, and therapies. Hospital medicine represents a new type of medical specialty that has the potential to address this increased complexity and sophistication and to improve patient care in the hospital inpatient environment (2).

Hospitalists as Team Coordinators

To achieve maximum positive outcomes in the complex inpatient environment, a qualified coordinator must educate others and facilitate activity revolving around patient care. Hospitalists as inpatient experts possess the necessary qualifications to integrate hospital systems and maximize efforts to enhance patient safety by monitoring medication distribution, chairing pharmaceuticals and therapeutics (P&T) committees, overseeing computerized physician order entry (CPOE), directing quality/performance improvement projects, and collaborating with discharge planning and case management.

Lakshmi Halasyamani, MD, is vice chair of the department of Internal Medicine at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Michigan and chairperson of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee. She says, Hospitalists have a ‘lens of understanding the systems under which they care for patients.’ They take care of patients in the hospital every single day so they can examine the processes with which they work. Hospitalists have an ideal perspective from which to reform ineffective systems.”

In spite of all the guidelines established by federal agencies and expert groups, Dr. Halasyamani points out that implementation barriers exist that prevent well-intentioned protocols and best practices from being carried out. Part of the challenge is the performance of a critical piece of the infrastructure—the multidisciplinary team. The very nature of healthcare demands an inherent need to coordinate and communicate. “Treating the patient is not the responsibility of one single individual,” says Halasyamani. “This is a team effort. The hospitalist recognizes that he is part of that team.” By elevating the ideals of teamwork, hospitalists can deliver to the patients the essential care that patients need, both while in the hospital and after they are discharged. In managing hospital inpatients, physicians must cope with high intensity of illness, pressures to reduce length of stay (LOS), and the coordination of handoffs among many specialists. According to Halasyamani, this can be a “recipe for disaster.”

Halasyamani acknowledges the vital role of protocols in reducing medical errors and improving quality of care. The training, education, and experience a hospitalist has acquired enables him to optimize communication and implement protocols, thus facilitating the practice of delivering safe and consistent care to all patients. In fact, with this smaller core group of inpatient physicians, the development and implementation of protocols can potentially be more effective because it targets a smaller group of physicians than the traditional inpatient model (8).

Kaveh C. Shojania, MD, is assistant professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa and co-author of Internal Bleeding: The Terrifying Truth Behind America's Epidemic Medical Mistakes. He points out that the current inpatient medical landscape involves a significant number of clinicians who practice at the hospital but not all their activity is centered there. “From a clinical perspective, no one has ownership,” he says. “On the other hand, hospitalists are based in a single hospital and have a vested interest in that particular hospital.” Typically generalists, hospitalists tend to interact with all specialists and therefore have a good sense of all interests.

Medical errors occur most often during transition times, from the ICU to the floor or from inpatient to outpatient status. There is the potential for a loss of clinical information during these transfers. According to Shojania, a significant portion of the hospitalist’s time is spent managing these transitions and overseeing patients as they are relocated from floor to floor and discharge to home, rehabilitation facility, or nursing home. He notes that the regulatory agencies have begun to acknowledge the importance of hospitalists. “The JCAHO (Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) recognizes hospitalists as a resource because they are always in the hospital and have a vested interest,” he says (9).

Stakeholder Analysis

Patients stand to gain the most benefit from hospitalists insofar as safety and quality of care is concerned. Through the efforts and oversight of hospitalists, patients may experience reduced medical errors and lower mortality rates. For primary care physicians and hospitals, this lower rate of medical error means fewer medical malpractice cases, the potential for lower insurance premiums and, as a result, enhanced reputations. When hospitals are run more efficiently and provide a greater sense of trust and efficient management practices, society in general becomes the benefactor.

Clinical Trials

To date, few research studies measuring the impact of hospitalists on patient safety and quality of care have been conducted. Quality of care has been assessed largely through the surrogate markers of mortality and readmission rates. One study showed decreased in-hospital and 1-year mortality rates for hospitalist patients (10), and another indicated a decrease in 30-day readmission rates (11).

In addition, data from individual programs demonstrate positive findings. For example, Stacy Goldsholl, MD, medical director of the Covenant Healthcare hospital medicine program in Michigan, reports a 17% decrease in the expected mortality rate in the first year of the hospital medicine program. The information was drawn from the Michigan Hospital Association (MHA) databank and matched for severity and diagnosis (See Table 2). “This was significant when compared to the internal medicine comparison group with similar case mix index (CMI),” says Goldsholl. “In the first half of our second year, we have demonstrated a 46% decrease in expected mortality, while internal medicine had a 4% increase” (12).

Additionally, Goldsholl reports that Covenant initiated a Code Blue and emergency consult service to improve patient outcome and experienced a marked increase in efficiency. Table 3 represents elementary data collected during the first 6 months pre- and post-initiation of the hospital medicine program at Covenant (12).

Conclusion

Patient safety and quality of care in the hospital require a team of dedicated people to effect change. Orchestrating the team effectively is the responsibility of an attending physician. With the numerous “handoffs” that take place during hospitalization, the potential for medical errors increases exponentially. Federal mandates requiring the conversion to electronic medical records, which includes basic health information as well as critical data regarding medications, procedures, and surgeries, further complicates efficient and safe patient management. According to Robert Wachter, “Those doctors with the best outcomes were those who tended to treat similar patients with similar problems using similar techniques.” By definition, the hospitalist is a “physician who focuses his practice on the care, coordination, and safety of hospitalized patients.” Who better to stand at the center of the issue of reduced medical errors, improved patient care, and enhanced quality of care than hospitalists (13)?

Dr. Pak can be contacted at mhp@medicine.wisc.edu.

References

- To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System, Institute of Medicine, November 1999.

- Wachter R. The end of the beginning: patient safety five years after ‘To Err Is Human.’ Health Affairs. November 30, 2004.

- Mission Statement: Center for Quality Improvement and Patient Safety. February 2004. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.ahrq.gov/about/cquips/cquipsmiss.htm.

- Safe Practices for Better Healthcare: a Consensus. The National Quality Forum, 2003.

- Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), www.jcaho.org.

- Leapfrog Group, www.leapfroggroup.org.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), www.acgme.org.

- Halasyamani L. Telephone interview. February 7, 2005.

- Shojania KG. Assistant professor of medicine, University of Ottawa. Telephone interview. January 31, 2005.

- Auerbach AD, Wachter RM, Katz P. et al. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:859-65.

- Kulaga ME, Charney P, O’Mahoney SP, et al. The positive impact of initiation of hospitalist clinician educators. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:293-301.

- Goldsholl S. Medical director. Covenant Healthcare hospital medicine program, Saginaw, Michigan, email interview. January 31, 2005.

- Wachter R, Shojania K. Internal bleeding: the truth behind America’s terrifying epidemic of medical mistakes. Rugged Land, LLC, 2004.

Improving Physician's Practices

Hospitals face a range of critical issues and need members of their medical staff to assume a role in addressing them. These concerns include declining payments and pressures on the bottom line; staffing shortages and dissatisfaction; questions about quality and patient safety; constantly changing technologies; employer and consumer demands for performance metrics; capacity constraints; and increased competition from independent, niche providers of clinical services.

Many physicians are no longer able or willing to serve on hospital committees or play a leadership role for the medical staff. As a result of the pressures of lost income, managed care requirements, on-call responsibilities, and competition for patients, as well as life-style concerns, many physicians are reluctant to perform volunteer work that hospitals used to take for granted. A 2004 survey of CEOs and physician leaders at 55 hospitals in the Northeast conducted by Mitretek, a healthcare consulting firm, noted that "volunteerism is dead." Physicians expect to be paid for time spent on hospital business. Sixty-four percent of the respondents said their hospitals compensate physicians to serve as officers or department heads (1).

"It used to be that most doctors needed the hospital to be successful; now that is not the case," says Larry Wellikson, MD, CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), the national professional society for hospitalists. Trends have shifted and a growing number of specialists do not even practice in the hospital (2).

Hospitalists: Stepping Up to the Medical Staff Leadership Challenge

Wellikson predicts that doctors on the hospital's "home team" - hospitalists, intensivists, and emergency department physicians - will assume more prominent positions on hospital committees. Hospitalists emerge as strong candidates for providing medical staff leadership for the following reasons:

- Hospitalists spend the majority of their time in the in-patient environment, making them familiar with hospital systems, policies, services, departments, and staff.

- Hospitalists are inpatient experts who possess clinical credibility when addressing key issues regarding the inpatient environment.

- Many hospitalists are hospital employees who can understand the tradeoffs involved in balancing the needs of the institution with those of the medical staff. Even hospitalists not employed by the hospital have an intimate knowledge of the issues that the hospital is facing and are invested in finding solutions to these problems.

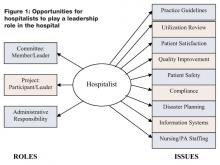

Figure 1. describes a range of roles that a hospitalist could assume and a range of topics that a hospitalist could address in providing medical staff leadership in a hospital.

The left side of the diagram describes three leadership roles that a hospitalist might play in the hospital. First, a hospitalist can volunteer to participate on a hospital committee, either as a member of the committee or as its chairperson. Second, a hospitalist can volunteer to work on a hospital project, either in a staff/expert role or in the role of project leader. Third, a hospitalist can assume a direct administrative role in the hospital, directing a service or program.

Whether it is through a committee, project, or direct administrative responsibility, a hospitalist has the knowledge and expertise to become involved in a wide range of hospital issues. As characterized on the right side of Figure 1, these topics include:

- Practice Guidelines: Many hospitals have adopted practice guidelines as a tool for improving the quality and efficiency of care. When properly developed, guidelines can improve patient safety, facilitate the adoption of best practices, and reduce hospital costs. Hospitalists can be asked to participate in all aspects of guideline development, including research, authorship, implementation, outcome measurement, and on-going revision and educational efforts.

- Utilization Review: Hospitals or medical groups routinely arrange for physicians to perform utilization review or improve the utilization review process. A hospitalist can: 1) facilitate the discharge process for individual patients, reducing length of stay and hospital costs; and 2) globally improve throughput by identifying and addressing system problems that create inefficiencies in the patient care or discharge process (e.g., paperwork or dictations not completed on time, poor communication across healthcare team disciplines, administrative deficiencies that delay therapies, etc.).

- Patient Satisfaction: Hospitals are increasingly being asked to capture and disseminate performance metrics so that employers and consumers can make informed decisions about their provider of choice. Patient satisfaction is a key measure of a hospital's performance. Hospitalists can become engaged in efforts to review patient satisfaction survey results, identify problems, and propose/implement solutions.

- Quality Improvement: Many hospitals look to hospitalists to become involved in or lead the hospital's quality improvement (QI) efforts. Specific activities may include championing individual QI projects, working with QI staff to develop and analyze outcomes data, educating colleagues regarding new projects and protocols, etc.

- Patient Safety: Preventing harmful errors from occurring in the inpatient environment has become a major priority for the hospitals across the country. Identifying the causes of these errors and developing methods of error prevention require detailed investigations and analyses of the diagnostic and/or treatment process. Increasingly, hospitalists are being asked to provide leadership to patient safety initiatives.

- Compliance: Hospitals must comply with many federal, state, and local rules and regulations. For example, a great deal of coordination and planning is required to meet the requirements of the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, and/or the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). In some hospitals, hospitalists assume leadership roles in these compliance efforts.

- Disaster Planning: Hospitals need to demonstrate the ability to respond to a range of potential crises, including those related to bioterrorism, industrial accidents, and natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes, tornados, and earthquakes). In light of their knowledge of patient flow, hospitalists can be asked to work with emergency physicians to do disaster planning for the hospital and the local region.

- Information Systems: Several organizations have issued reports identifying information technology as a critical tool for improving healthcare quality (e.g., Institute of Medicine [IOM], the Leapfrog Group, eHealth Initiative, the Markle Foundation, and the Federal Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology). Hospitals are being encouraged and incentivized to implement electronic health records (EHRs) and computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems. Implementing these systems requires significant clinical input. Many hospitals have asked hospitalists to champion and lead the implementation process of new information systems.

- Nursing/Physician Assistant Staffing: There exists a wide range of roles for nurses and physician assistants in the inpatient setting. Every institution needs to find a staffing model that is efficient, effective, and results in provider satisfaction. Hospitalists are considered leaders of the inpatient medical team and can be asked to help design and evaluate staffing models.

Hospitalists as Physician Leaders: The Facts

A 1999 survey (3) conducted by the National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP, now SHM) documented the medical staff leadership roles of hospitalists. Of the survey respondents, 53% held responsibility for quality assurance and/or utilization review; 46% were responsible for practice guideline development; 23% had administrative responsibilities; and 22% were charged with information systems development.

There are several different types of hospitalist programs and, as shown by the examples below, each model offers opportunities for hospitalists to play a medical staff leadership role.

Academic Medical Centers

The hospitalists that practice at University of California at San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) are making a significant impact on many critical hospital issues. Robert Wächter, MD, chief of the hospitalist program at UCSF and a former president of SI IM says, while it is still important to have other specialists serve on medical staff committees, UCSF hospitalists participate on all committees, chairing some of the crucial ones, such as patient safety. "The structure of the medical staff won't change, but the doctors who participate will," Wächter says. "They [hospitalists] will be more invested in the hospital, so the nature of the committee work will change. It will become more effective" (4). Selected QI projects led by UCSF hospitalists include:

- Medical Service Discharge Planning Improvement Project

- Collaborative Daily Bedside Rounds— a program to improve physician-nurse communication

- Protocol for Management of Alcohol Withdrawal

- Protocol for Prevention and Management of Delirium

- Medical Service Intern Signout— an educational program to enhance physician signout in the setting of new resident duty hours requirements

- Perioperative Performance Improvement Project— assessing the use of beta-blockers, glucose management surgical site infection and DVT prophylaxis

- DVT Treatment and DVT Prophylaxis Protocols

- JCAHO Core Measures in community acquired pneumonia and smoking cessation

- Post-Discharge Home Visits— a collaborative pharmacy-hospitalist project for patients at high risk for readmission

UCSF hospitalists are also leaders and key participants in many interdisciplinary medical center performance improvement committees including the Patient Safety Committee, Clinical Performance Improvement Committee, Physicians Advisory Group for Clinical Information Systems, Patient Satisfaction Committee, Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, and the Patient Flow Committee (4).

Community Hospitals

At Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, MA, 10% of the hospitalist's bonus is based on participation in "good citizenship" activities for the hospital. To earn his bonus, Winthrop Whitcomb, MD, director of the Mercy Inpatient Medical Service (MIMS), organizes the hospital's CME accredited medical education series, which is offered to the entire medical staff. Every month, Whitcomb is responsible for developing learning objectives, identifying speakers, and coordinating the program logistics.

Other MIMS hospitalists have chosen the following good citizenship activities:

- Chairperson of the Medication Reconciliation Committee, a statewide initiative designed to assure medication information is consistently communicated across different care settings

- Leadership of a tribunal that evaluated a physician for ethical issues and made a decision whether or not medical staff privileges should be revoked

- Clinical expert and resource for the implementation of a new hospital information system

Medical Groups

Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates (HVMA) is a 550-physician group practice with 14 practice locations in the greater Boston area. Joseph L. Dorsey, MD, director of the medical group's hospitalist program, described the following medical staff leadership roles that HVMA hospitalists execute at their six affiliated hospitals:

- Quality Improvement Committee

- Interdepartmental Committee, which reviews cases for possible reporting to state healthcare agencies

- Medical Executive Committee

- Clinical and Education Planning Task Force, which is preparing plans to move approximately 60 medical inpatients off the house staff covered service onto a Physician Assistant-supported alternative

- Advisory Committee to the Department of Medicine Chairperson, consisting of all sub-specialty Chiefs

- Credentialing Committee

- Clinical Teaching Initiative

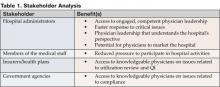

Stakeholder analysis

By playing a medical staff leadership role, hospitalists provide value to several stakeholders involved in the inpatient care process. The benefits to these stakeholders are summarized in Table 1.

Conclusion

Hospital administrators need physician leaders to address critical strategic and operational issues. Given their position as "inpatient experts," hospitalists are a logical choice to play this role. In the years ahead, it is likely that hospitalists will assume an increasingly important leadership role within community hospitals and academic medical centers around the country.

Dr. Pak can be contacted at mhp@medicine.wisc.edu.

Ms. Kerr can be contacted at kkerr@medicine.ucsf.edu.

References

- McGowan RA. Strengthening hospital-physician relationships. HFMA Business December 2004.

- Hospitals & Health Networks, Vol. 77, No. 11. Health Forum, November 2003.

- Lindenauer PK, Pantilat SZ, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: result of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130: 343-9.

- UCSF hospitalist Web site: http://medicine.ucsf.edu/hospitalists/quality.html.

Hospitals face a range of critical issues and need members of their medical staff to assume a role in addressing them. These concerns include declining payments and pressures on the bottom line; staffing shortages and dissatisfaction; questions about quality and patient safety; constantly changing technologies; employer and consumer demands for performance metrics; capacity constraints; and increased competition from independent, niche providers of clinical services.

Many physicians are no longer able or willing to serve on hospital committees or play a leadership role for the medical staff. As a result of the pressures of lost income, managed care requirements, on-call responsibilities, and competition for patients, as well as life-style concerns, many physicians are reluctant to perform volunteer work that hospitals used to take for granted. A 2004 survey of CEOs and physician leaders at 55 hospitals in the Northeast conducted by Mitretek, a healthcare consulting firm, noted that "volunteerism is dead." Physicians expect to be paid for time spent on hospital business. Sixty-four percent of the respondents said their hospitals compensate physicians to serve as officers or department heads (1).

"It used to be that most doctors needed the hospital to be successful; now that is not the case," says Larry Wellikson, MD, CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), the national professional society for hospitalists. Trends have shifted and a growing number of specialists do not even practice in the hospital (2).

Hospitalists: Stepping Up to the Medical Staff Leadership Challenge

Wellikson predicts that doctors on the hospital's "home team" - hospitalists, intensivists, and emergency department physicians - will assume more prominent positions on hospital committees. Hospitalists emerge as strong candidates for providing medical staff leadership for the following reasons:

- Hospitalists spend the majority of their time in the in-patient environment, making them familiar with hospital systems, policies, services, departments, and staff.

- Hospitalists are inpatient experts who possess clinical credibility when addressing key issues regarding the inpatient environment.

- Many hospitalists are hospital employees who can understand the tradeoffs involved in balancing the needs of the institution with those of the medical staff. Even hospitalists not employed by the hospital have an intimate knowledge of the issues that the hospital is facing and are invested in finding solutions to these problems.

Figure 1. describes a range of roles that a hospitalist could assume and a range of topics that a hospitalist could address in providing medical staff leadership in a hospital.

The left side of the diagram describes three leadership roles that a hospitalist might play in the hospital. First, a hospitalist can volunteer to participate on a hospital committee, either as a member of the committee or as its chairperson. Second, a hospitalist can volunteer to work on a hospital project, either in a staff/expert role or in the role of project leader. Third, a hospitalist can assume a direct administrative role in the hospital, directing a service or program.

Whether it is through a committee, project, or direct administrative responsibility, a hospitalist has the knowledge and expertise to become involved in a wide range of hospital issues. As characterized on the right side of Figure 1, these topics include:

- Practice Guidelines: Many hospitals have adopted practice guidelines as a tool for improving the quality and efficiency of care. When properly developed, guidelines can improve patient safety, facilitate the adoption of best practices, and reduce hospital costs. Hospitalists can be asked to participate in all aspects of guideline development, including research, authorship, implementation, outcome measurement, and on-going revision and educational efforts.

- Utilization Review: Hospitals or medical groups routinely arrange for physicians to perform utilization review or improve the utilization review process. A hospitalist can: 1) facilitate the discharge process for individual patients, reducing length of stay and hospital costs; and 2) globally improve throughput by identifying and addressing system problems that create inefficiencies in the patient care or discharge process (e.g., paperwork or dictations not completed on time, poor communication across healthcare team disciplines, administrative deficiencies that delay therapies, etc.).

- Patient Satisfaction: Hospitals are increasingly being asked to capture and disseminate performance metrics so that employers and consumers can make informed decisions about their provider of choice. Patient satisfaction is a key measure of a hospital's performance. Hospitalists can become engaged in efforts to review patient satisfaction survey results, identify problems, and propose/implement solutions.

- Quality Improvement: Many hospitals look to hospitalists to become involved in or lead the hospital's quality improvement (QI) efforts. Specific activities may include championing individual QI projects, working with QI staff to develop and analyze outcomes data, educating colleagues regarding new projects and protocols, etc.

- Patient Safety: Preventing harmful errors from occurring in the inpatient environment has become a major priority for the hospitals across the country. Identifying the causes of these errors and developing methods of error prevention require detailed investigations and analyses of the diagnostic and/or treatment process. Increasingly, hospitalists are being asked to provide leadership to patient safety initiatives.

- Compliance: Hospitals must comply with many federal, state, and local rules and regulations. For example, a great deal of coordination and planning is required to meet the requirements of the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, and/or the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). In some hospitals, hospitalists assume leadership roles in these compliance efforts.

- Disaster Planning: Hospitals need to demonstrate the ability to respond to a range of potential crises, including those related to bioterrorism, industrial accidents, and natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes, tornados, and earthquakes). In light of their knowledge of patient flow, hospitalists can be asked to work with emergency physicians to do disaster planning for the hospital and the local region.

- Information Systems: Several organizations have issued reports identifying information technology as a critical tool for improving healthcare quality (e.g., Institute of Medicine [IOM], the Leapfrog Group, eHealth Initiative, the Markle Foundation, and the Federal Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology). Hospitals are being encouraged and incentivized to implement electronic health records (EHRs) and computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems. Implementing these systems requires significant clinical input. Many hospitals have asked hospitalists to champion and lead the implementation process of new information systems.

- Nursing/Physician Assistant Staffing: There exists a wide range of roles for nurses and physician assistants in the inpatient setting. Every institution needs to find a staffing model that is efficient, effective, and results in provider satisfaction. Hospitalists are considered leaders of the inpatient medical team and can be asked to help design and evaluate staffing models.

Hospitalists as Physician Leaders: The Facts

A 1999 survey (3) conducted by the National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP, now SHM) documented the medical staff leadership roles of hospitalists. Of the survey respondents, 53% held responsibility for quality assurance and/or utilization review; 46% were responsible for practice guideline development; 23% had administrative responsibilities; and 22% were charged with information systems development.

There are several different types of hospitalist programs and, as shown by the examples below, each model offers opportunities for hospitalists to play a medical staff leadership role.

Academic Medical Centers

The hospitalists that practice at University of California at San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) are making a significant impact on many critical hospital issues. Robert Wächter, MD, chief of the hospitalist program at UCSF and a former president of SI IM says, while it is still important to have other specialists serve on medical staff committees, UCSF hospitalists participate on all committees, chairing some of the crucial ones, such as patient safety. "The structure of the medical staff won't change, but the doctors who participate will," Wächter says. "They [hospitalists] will be more invested in the hospital, so the nature of the committee work will change. It will become more effective" (4). Selected QI projects led by UCSF hospitalists include:

- Medical Service Discharge Planning Improvement Project

- Collaborative Daily Bedside Rounds— a program to improve physician-nurse communication

- Protocol for Management of Alcohol Withdrawal

- Protocol for Prevention and Management of Delirium

- Medical Service Intern Signout— an educational program to enhance physician signout in the setting of new resident duty hours requirements

- Perioperative Performance Improvement Project— assessing the use of beta-blockers, glucose management surgical site infection and DVT prophylaxis

- DVT Treatment and DVT Prophylaxis Protocols

- JCAHO Core Measures in community acquired pneumonia and smoking cessation

- Post-Discharge Home Visits— a collaborative pharmacy-hospitalist project for patients at high risk for readmission

UCSF hospitalists are also leaders and key participants in many interdisciplinary medical center performance improvement committees including the Patient Safety Committee, Clinical Performance Improvement Committee, Physicians Advisory Group for Clinical Information Systems, Patient Satisfaction Committee, Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, and the Patient Flow Committee (4).

Community Hospitals

At Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, MA, 10% of the hospitalist's bonus is based on participation in "good citizenship" activities for the hospital. To earn his bonus, Winthrop Whitcomb, MD, director of the Mercy Inpatient Medical Service (MIMS), organizes the hospital's CME accredited medical education series, which is offered to the entire medical staff. Every month, Whitcomb is responsible for developing learning objectives, identifying speakers, and coordinating the program logistics.

Other MIMS hospitalists have chosen the following good citizenship activities:

- Chairperson of the Medication Reconciliation Committee, a statewide initiative designed to assure medication information is consistently communicated across different care settings

- Leadership of a tribunal that evaluated a physician for ethical issues and made a decision whether or not medical staff privileges should be revoked

- Clinical expert and resource for the implementation of a new hospital information system

Medical Groups

Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates (HVMA) is a 550-physician group practice with 14 practice locations in the greater Boston area. Joseph L. Dorsey, MD, director of the medical group's hospitalist program, described the following medical staff leadership roles that HVMA hospitalists execute at their six affiliated hospitals:

- Quality Improvement Committee

- Interdepartmental Committee, which reviews cases for possible reporting to state healthcare agencies

- Medical Executive Committee

- Clinical and Education Planning Task Force, which is preparing plans to move approximately 60 medical inpatients off the house staff covered service onto a Physician Assistant-supported alternative

- Advisory Committee to the Department of Medicine Chairperson, consisting of all sub-specialty Chiefs

- Credentialing Committee

- Clinical Teaching Initiative

Stakeholder analysis

By playing a medical staff leadership role, hospitalists provide value to several stakeholders involved in the inpatient care process. The benefits to these stakeholders are summarized in Table 1.

Conclusion

Hospital administrators need physician leaders to address critical strategic and operational issues. Given their position as "inpatient experts," hospitalists are a logical choice to play this role. In the years ahead, it is likely that hospitalists will assume an increasingly important leadership role within community hospitals and academic medical centers around the country.

Dr. Pak can be contacted at mhp@medicine.wisc.edu.

Ms. Kerr can be contacted at kkerr@medicine.ucsf.edu.

References

- McGowan RA. Strengthening hospital-physician relationships. HFMA Business December 2004.

- Hospitals & Health Networks, Vol. 77, No. 11. Health Forum, November 2003.

- Lindenauer PK, Pantilat SZ, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: result of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130: 343-9.

- UCSF hospitalist Web site: http://medicine.ucsf.edu/hospitalists/quality.html.

Hospitals face a range of critical issues and need members of their medical staff to assume a role in addressing them. These concerns include declining payments and pressures on the bottom line; staffing shortages and dissatisfaction; questions about quality and patient safety; constantly changing technologies; employer and consumer demands for performance metrics; capacity constraints; and increased competition from independent, niche providers of clinical services.

Many physicians are no longer able or willing to serve on hospital committees or play a leadership role for the medical staff. As a result of the pressures of lost income, managed care requirements, on-call responsibilities, and competition for patients, as well as life-style concerns, many physicians are reluctant to perform volunteer work that hospitals used to take for granted. A 2004 survey of CEOs and physician leaders at 55 hospitals in the Northeast conducted by Mitretek, a healthcare consulting firm, noted that "volunteerism is dead." Physicians expect to be paid for time spent on hospital business. Sixty-four percent of the respondents said their hospitals compensate physicians to serve as officers or department heads (1).

"It used to be that most doctors needed the hospital to be successful; now that is not the case," says Larry Wellikson, MD, CEO of the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), the national professional society for hospitalists. Trends have shifted and a growing number of specialists do not even practice in the hospital (2).

Hospitalists: Stepping Up to the Medical Staff Leadership Challenge

Wellikson predicts that doctors on the hospital's "home team" - hospitalists, intensivists, and emergency department physicians - will assume more prominent positions on hospital committees. Hospitalists emerge as strong candidates for providing medical staff leadership for the following reasons:

- Hospitalists spend the majority of their time in the in-patient environment, making them familiar with hospital systems, policies, services, departments, and staff.

- Hospitalists are inpatient experts who possess clinical credibility when addressing key issues regarding the inpatient environment.

- Many hospitalists are hospital employees who can understand the tradeoffs involved in balancing the needs of the institution with those of the medical staff. Even hospitalists not employed by the hospital have an intimate knowledge of the issues that the hospital is facing and are invested in finding solutions to these problems.

Figure 1. describes a range of roles that a hospitalist could assume and a range of topics that a hospitalist could address in providing medical staff leadership in a hospital.

The left side of the diagram describes three leadership roles that a hospitalist might play in the hospital. First, a hospitalist can volunteer to participate on a hospital committee, either as a member of the committee or as its chairperson. Second, a hospitalist can volunteer to work on a hospital project, either in a staff/expert role or in the role of project leader. Third, a hospitalist can assume a direct administrative role in the hospital, directing a service or program.

Whether it is through a committee, project, or direct administrative responsibility, a hospitalist has the knowledge and expertise to become involved in a wide range of hospital issues. As characterized on the right side of Figure 1, these topics include:

- Practice Guidelines: Many hospitals have adopted practice guidelines as a tool for improving the quality and efficiency of care. When properly developed, guidelines can improve patient safety, facilitate the adoption of best practices, and reduce hospital costs. Hospitalists can be asked to participate in all aspects of guideline development, including research, authorship, implementation, outcome measurement, and on-going revision and educational efforts.

- Utilization Review: Hospitals or medical groups routinely arrange for physicians to perform utilization review or improve the utilization review process. A hospitalist can: 1) facilitate the discharge process for individual patients, reducing length of stay and hospital costs; and 2) globally improve throughput by identifying and addressing system problems that create inefficiencies in the patient care or discharge process (e.g., paperwork or dictations not completed on time, poor communication across healthcare team disciplines, administrative deficiencies that delay therapies, etc.).

- Patient Satisfaction: Hospitals are increasingly being asked to capture and disseminate performance metrics so that employers and consumers can make informed decisions about their provider of choice. Patient satisfaction is a key measure of a hospital's performance. Hospitalists can become engaged in efforts to review patient satisfaction survey results, identify problems, and propose/implement solutions.

- Quality Improvement: Many hospitals look to hospitalists to become involved in or lead the hospital's quality improvement (QI) efforts. Specific activities may include championing individual QI projects, working with QI staff to develop and analyze outcomes data, educating colleagues regarding new projects and protocols, etc.

- Patient Safety: Preventing harmful errors from occurring in the inpatient environment has become a major priority for the hospitals across the country. Identifying the causes of these errors and developing methods of error prevention require detailed investigations and analyses of the diagnostic and/or treatment process. Increasingly, hospitalists are being asked to provide leadership to patient safety initiatives.

- Compliance: Hospitals must comply with many federal, state, and local rules and regulations. For example, a great deal of coordination and planning is required to meet the requirements of the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, and/or the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). In some hospitals, hospitalists assume leadership roles in these compliance efforts.

- Disaster Planning: Hospitals need to demonstrate the ability to respond to a range of potential crises, including those related to bioterrorism, industrial accidents, and natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes, tornados, and earthquakes). In light of their knowledge of patient flow, hospitalists can be asked to work with emergency physicians to do disaster planning for the hospital and the local region.

- Information Systems: Several organizations have issued reports identifying information technology as a critical tool for improving healthcare quality (e.g., Institute of Medicine [IOM], the Leapfrog Group, eHealth Initiative, the Markle Foundation, and the Federal Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology). Hospitals are being encouraged and incentivized to implement electronic health records (EHRs) and computerized physician order entry (CPOE) systems. Implementing these systems requires significant clinical input. Many hospitals have asked hospitalists to champion and lead the implementation process of new information systems.

- Nursing/Physician Assistant Staffing: There exists a wide range of roles for nurses and physician assistants in the inpatient setting. Every institution needs to find a staffing model that is efficient, effective, and results in provider satisfaction. Hospitalists are considered leaders of the inpatient medical team and can be asked to help design and evaluate staffing models.

Hospitalists as Physician Leaders: The Facts

A 1999 survey (3) conducted by the National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP, now SHM) documented the medical staff leadership roles of hospitalists. Of the survey respondents, 53% held responsibility for quality assurance and/or utilization review; 46% were responsible for practice guideline development; 23% had administrative responsibilities; and 22% were charged with information systems development.

There are several different types of hospitalist programs and, as shown by the examples below, each model offers opportunities for hospitalists to play a medical staff leadership role.

Academic Medical Centers

The hospitalists that practice at University of California at San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) are making a significant impact on many critical hospital issues. Robert Wächter, MD, chief of the hospitalist program at UCSF and a former president of SI IM says, while it is still important to have other specialists serve on medical staff committees, UCSF hospitalists participate on all committees, chairing some of the crucial ones, such as patient safety. "The structure of the medical staff won't change, but the doctors who participate will," Wächter says. "They [hospitalists] will be more invested in the hospital, so the nature of the committee work will change. It will become more effective" (4). Selected QI projects led by UCSF hospitalists include:

- Medical Service Discharge Planning Improvement Project

- Collaborative Daily Bedside Rounds— a program to improve physician-nurse communication

- Protocol for Management of Alcohol Withdrawal

- Protocol for Prevention and Management of Delirium

- Medical Service Intern Signout— an educational program to enhance physician signout in the setting of new resident duty hours requirements

- Perioperative Performance Improvement Project— assessing the use of beta-blockers, glucose management surgical site infection and DVT prophylaxis

- DVT Treatment and DVT Prophylaxis Protocols

- JCAHO Core Measures in community acquired pneumonia and smoking cessation

- Post-Discharge Home Visits— a collaborative pharmacy-hospitalist project for patients at high risk for readmission

UCSF hospitalists are also leaders and key participants in many interdisciplinary medical center performance improvement committees including the Patient Safety Committee, Clinical Performance Improvement Committee, Physicians Advisory Group for Clinical Information Systems, Patient Satisfaction Committee, Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, and the Patient Flow Committee (4).

Community Hospitals

At Mercy Medical Center in Springfield, MA, 10% of the hospitalist's bonus is based on participation in "good citizenship" activities for the hospital. To earn his bonus, Winthrop Whitcomb, MD, director of the Mercy Inpatient Medical Service (MIMS), organizes the hospital's CME accredited medical education series, which is offered to the entire medical staff. Every month, Whitcomb is responsible for developing learning objectives, identifying speakers, and coordinating the program logistics.

Other MIMS hospitalists have chosen the following good citizenship activities:

- Chairperson of the Medication Reconciliation Committee, a statewide initiative designed to assure medication information is consistently communicated across different care settings

- Leadership of a tribunal that evaluated a physician for ethical issues and made a decision whether or not medical staff privileges should be revoked

- Clinical expert and resource for the implementation of a new hospital information system

Medical Groups

Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates (HVMA) is a 550-physician group practice with 14 practice locations in the greater Boston area. Joseph L. Dorsey, MD, director of the medical group's hospitalist program, described the following medical staff leadership roles that HVMA hospitalists execute at their six affiliated hospitals:

- Quality Improvement Committee

- Interdepartmental Committee, which reviews cases for possible reporting to state healthcare agencies

- Medical Executive Committee

- Clinical and Education Planning Task Force, which is preparing plans to move approximately 60 medical inpatients off the house staff covered service onto a Physician Assistant-supported alternative

- Advisory Committee to the Department of Medicine Chairperson, consisting of all sub-specialty Chiefs

- Credentialing Committee

- Clinical Teaching Initiative

Stakeholder analysis

By playing a medical staff leadership role, hospitalists provide value to several stakeholders involved in the inpatient care process. The benefits to these stakeholders are summarized in Table 1.

Conclusion

Hospital administrators need physician leaders to address critical strategic and operational issues. Given their position as "inpatient experts," hospitalists are a logical choice to play this role. In the years ahead, it is likely that hospitalists will assume an increasingly important leadership role within community hospitals and academic medical centers around the country.

Dr. Pak can be contacted at mhp@medicine.wisc.edu.

Ms. Kerr can be contacted at kkerr@medicine.ucsf.edu.

References

- McGowan RA. Strengthening hospital-physician relationships. HFMA Business December 2004.

- Hospitals & Health Networks, Vol. 77, No. 11. Health Forum, November 2003.

- Lindenauer PK, Pantilat SZ, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: result of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130: 343-9.

- UCSF hospitalist Web site: http://medicine.ucsf.edu/hospitalists/quality.html.