User login

Update on Acne Scar Treatment

Acne vulgaris is prevalent in the general population, with 40 to 50 million affected individuals in the United States.1 Severe inflammation and injury can lead to disfiguring scarring, which has a considerable impact on quality of life.2 Numerous therapeutic options for acne scarring are available, including microneedling with and without platelet-rich plasma (PRP), lasers, chemical peels, and dermal fillers, with different modalities suited to individual patients and scar characteristics. This article reviews updates in treatment options for acne scarring.

Microneedling

Microneedling, also known as percutaneous collagen induction or collagen induction therapy, has been utilized for more than 2 decades.3 Dermatologic indications for microneedling include skin rejuvenation,4-6 atrophic acne scarring,7-9 and androgenic alopecia.10,11 Microneedling also has been used to enhance skin penetration of topically applied drugs.12-15 Fernandes16 described percutaneous collagen induction as the skin’s natural response to injury. Microneedling creates small wounds as fine needles puncture the epidermis and dermis, resulting in a cascade of growth factors that lead to tissue proliferation, regeneration, and a collagen remodeling phase that can last for several months.8,16

Microneedling has gained popularity in the treatment of acne scarring.7 Alam et al9 conducted a split-face randomized clinical trial (RCT) to evaluate acne scarring after 3 microneedling sessions performed at 2-week intervals. Twenty participants with acne scarring on both sides of the face were enrolled in the study and one side of the face was randomized for treatment. Participants had at least two 5×5-cm areas of acne scarring graded as 2 (moderately atrophic scars) to 4 (hyperplastic or papular scars) on the quantitative Global Acne Scarring Classification system. A roller device with a 1.0-mm depth was used on participants with fine, less sebaceous skin and a 2.0-mm device for all others. Two blinded investigators assessed acne scars at baseline and at 3 and 6 months after treatment. Scar improvement was measured using the quantitative Goodman and Baron scale, which provides a score according to type and number of scars.17 Mean scar scores were significantly reduced at 6 months compared to baseline on the treatment side (P=.03) but not the control side. Participants experienced minimal pain associated with microneedling therapy, rated 1.08 of 10, and adverse effects were limited to mild transient erythema and edema.9 Several other clinical trials have demonstrated clinical improvements with microneedling.18-20

The benefits of microneedling also have been observed on a histologic level. One group of investigators explored the effects of microneedling on dermal collagen in the treatment of various atrophic acne scars in 10 participants.7 After 6 treatment sessions performed at 2-week intervals, dermal collagen was assessed via punch biopsy. A roller device with a needle depth of 1.5 mm was used for all patients. At 1 month after treatment compared to baseline, mean (SD) levels of type I collagen were significantly increased (67.1% [4.2%] vs 70.4% [5.4%]; P=.01) as well as at 3 months after treatment compared to baseline for type III collagen (61.4% [3.6%] vs 74.3% [7.4%]; P=.01), type VII collagen (15.2% [2.1%] vs 21.3% [1.2%]; P=.03), and newly synthesized collagen (14.5% [5.8%] vs 19.5% [3.2%]; P=.02). Total elastin levels were significantly decreased at 3 months after treatment compared to baseline (51.3% [6.7%] vs 46.9% [4.3%]; P=.04). Adverse effects were limited to transient erythema and edema.7

Microneedling With Platelet-Rich Plasma

Microneedling has been combined with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.21 In addition to inducing new collagen synthesis, microneedling aids in the absorption of PRP, an autologous concentrate of platelets that is obtained through peripheral venipuncture. The concentrate is centrifuged into 3 layers: (1) platelet-poor plasma, (2) PRP, and (3) erythrocytes.22 Platelet-rich plasma contains growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor (TGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor, as well as cell adhesion molecules.22,23 The application of PRP is thought to result in upregulated protein synthesis, greater collagen remodeling, and accelerated wound healing.21

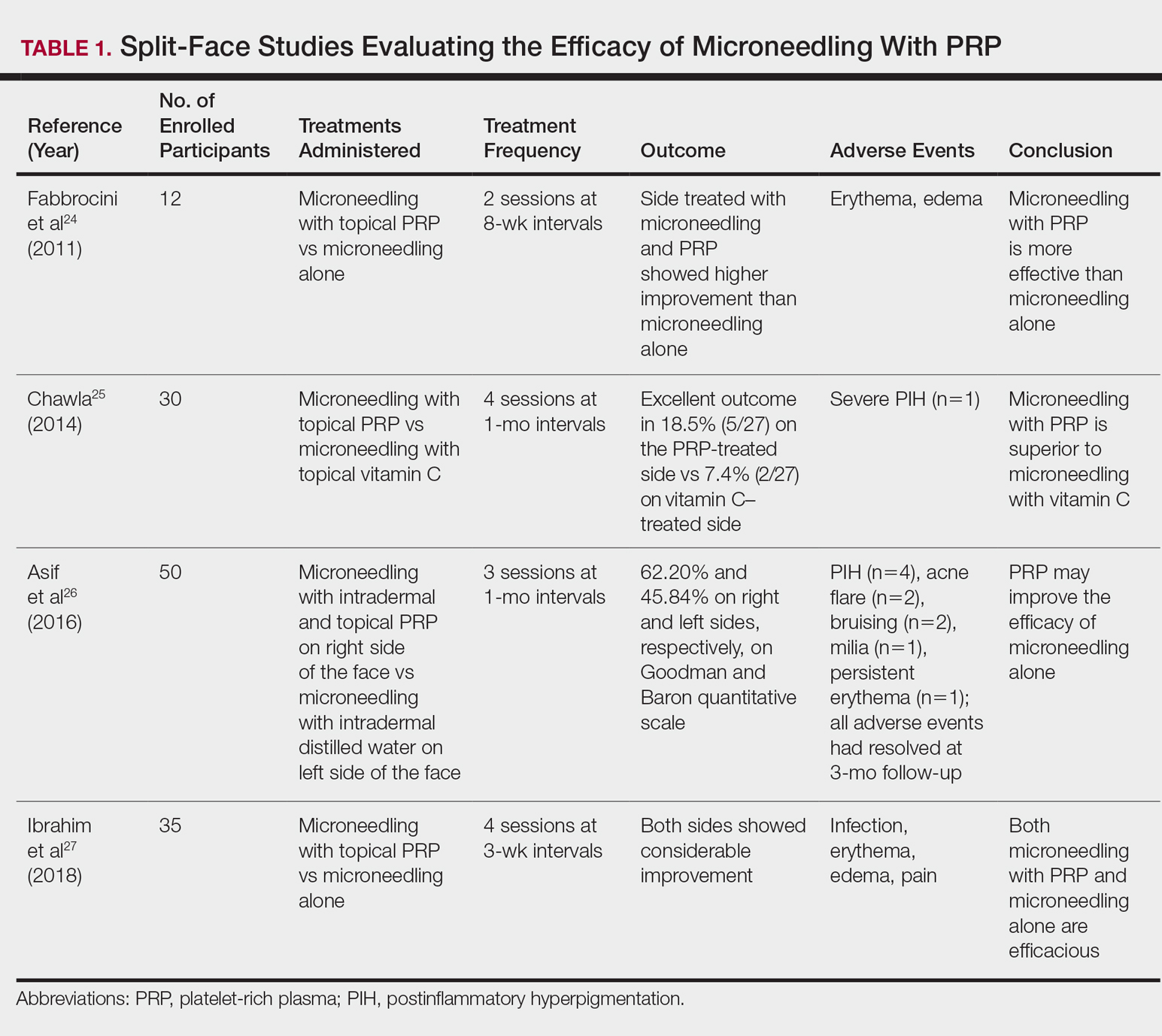

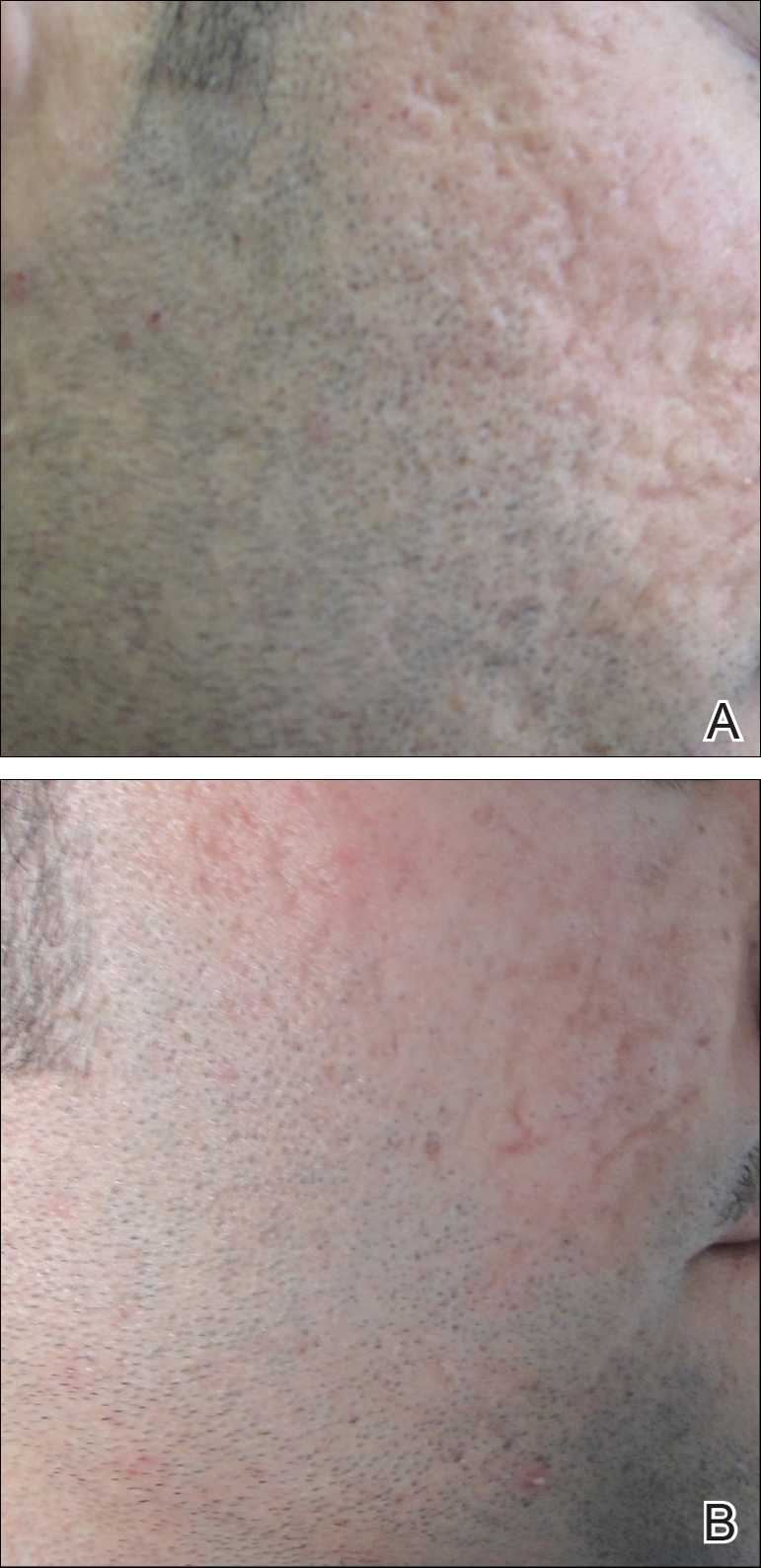

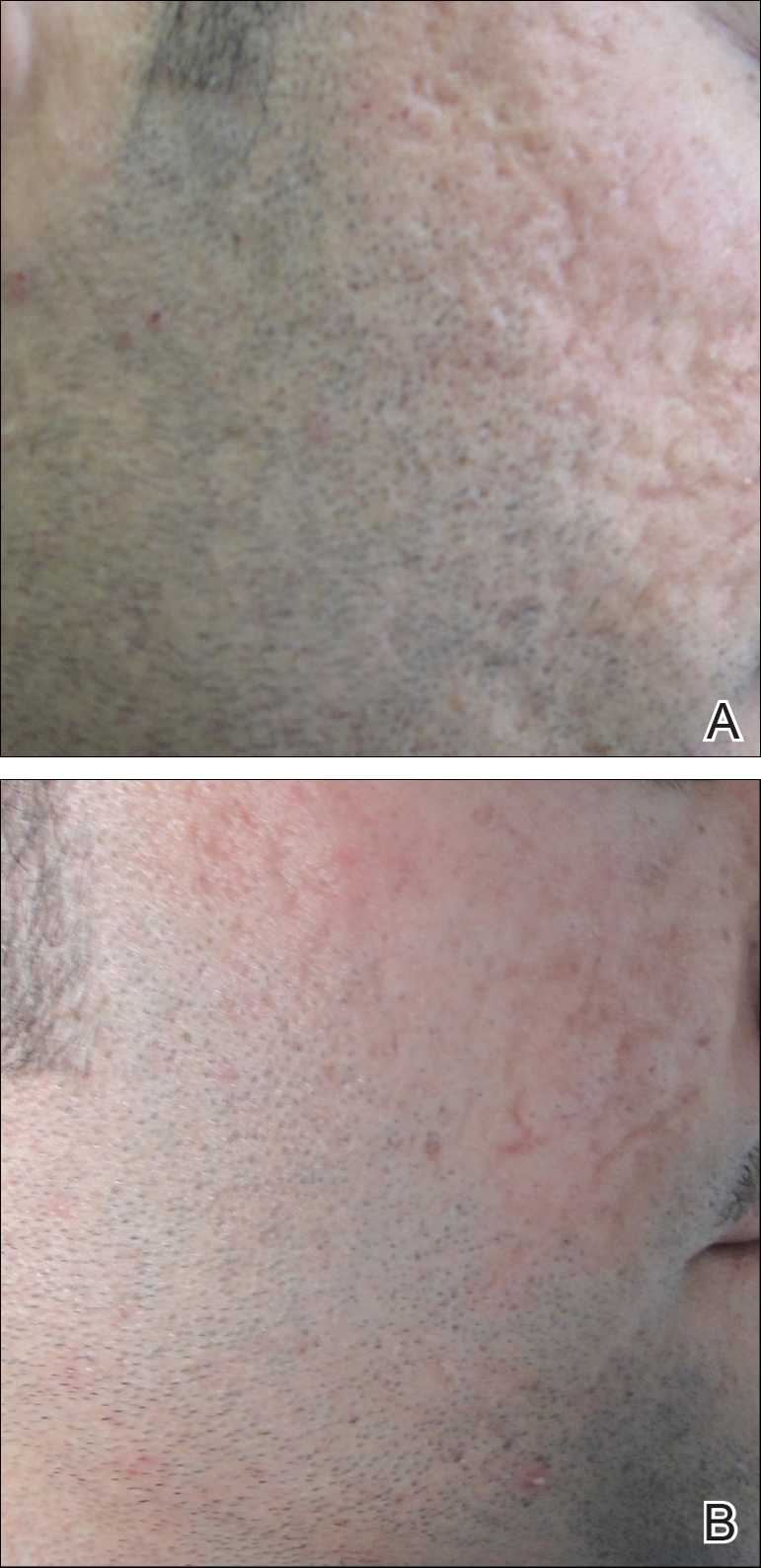

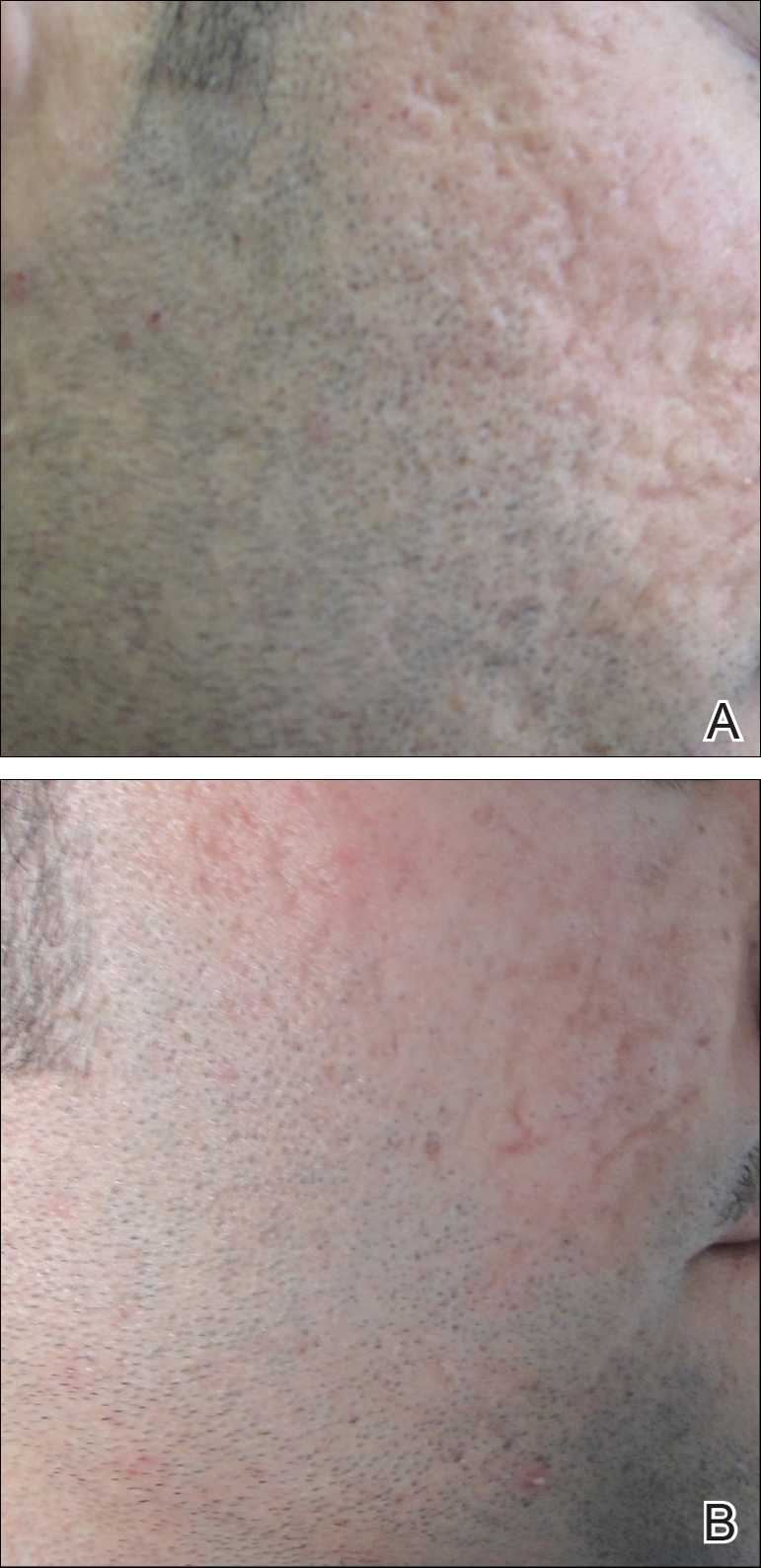

Several studies have shown that the addition of PRP to microneedling can improve treatment outcome (Table 1).24-27 Severity of acne scarring can be improved, such as reduced scar depth, by using both modalities synergistically (Figure).24 Asif et al26 compared microneedling with PRP to microneedling with distilled water in the treatment of 50 patients with atrophic acne scars graded 2 to 4 (mild to severe acne scarring) on the Goodman’s Qualitative classification and equal Goodman’s Qualitative and Quantitative scores on both halves of the face.17,28 The right side of the face was treated with a 1.5-mm microneedling roller with intradermal and topical PRP, while the left side was treated with distilled water (placebo) delivered intradermally. Patients underwent 3 treatment sessions at 1-month intervals. The area treated with microneedling and PRP showed a 62.20% improvement from baseline after 3 treatments, while the placebo-treated area showed a 45.84% improvement on the Goodman and Baron quantitative scale.26

Chawla25 compared microneedling with topical PRP to microneedling with topical vitamin C in a split-face study of 30 participants with atrophic acne scarring graded 2 to 4 on the Goodman and Baron scale. A 1.5-mm roller device was used. Patients underwent 4 treatment sessions at 1-month intervals, and treatment efficacy was evaluated using the qualitative Goodman and Baron scale.28 Participants experienced positive outcomes overall with both treatments. Notably, 18.5% (5/27) on the microneedling with PRP side demonstrated excellent response compared to 7.4% (2/27) on the microneedling with vitamin C side.25

Laser Treatment

Laser skin resurfacing has shown to be efficacious in the treatment of both acne vulgaris and acne scarring. Various lasers have been utilized, including nonfractional CO2 and erbium-doped:YAG (Er:YAG) lasers, as well as ablative fractional lasers (AFLs) and nonablative fractional lasers (NAFLs).29

One retrospective study of 58 patients compared the use of 2 resurfacing lasers—10,600-nm nonfractional CO2 and 2940-nm Er:YAG—and 2 fractional lasers—1550-nm NAFL and 10,600-nm AFL—in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.29 A retrospective photographic analysis was performed by 6 blinded dermatologists to evaluate clinical improvement on a scale of 0 (no improvement) to 10 (excellent improvement). The mean improvement scores of the CO2, Er:YAG, AFL, and NAFL groups were 6.0, 5.8, 2.2, and 5.2, respectively, and the mean number of treatments was 1.6, 1.1, 4.0, and 3.4, respectively. Thus, patients in the fractional laser groups required more treatments; however, those in the resurfacing laser groups had longer recovery times, pain, erythema, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The investigators concluded that 3 consecutive AFL treatments could be as effective as a single resurfacing treatment with lower risk for complications.29

A split-face RCT compared the use of the fractional Er:YAG laser on one side of the face to microneedling with a 2.0-mm needle on the other side for treatment of atrophic acne scars.30 Thirty patients underwent 5 treatments at 1-month intervals. At 3-month follow-up, the areas treated with the Er:YAG laser showed 70% improvement from baseline compared to 30% improvement in the areas treated with microneedling (P<.001). Histologically, the Er:YAG laser showed a higher increase in dermal collagen than microneedling (P<.001). Furthermore, the Er:YAG laser yielded significantly lower pain scores (P<.001); however, patients reported higher rates of erythema, swelling, superficial crusting, and total downtime.30

Lasers With PRP

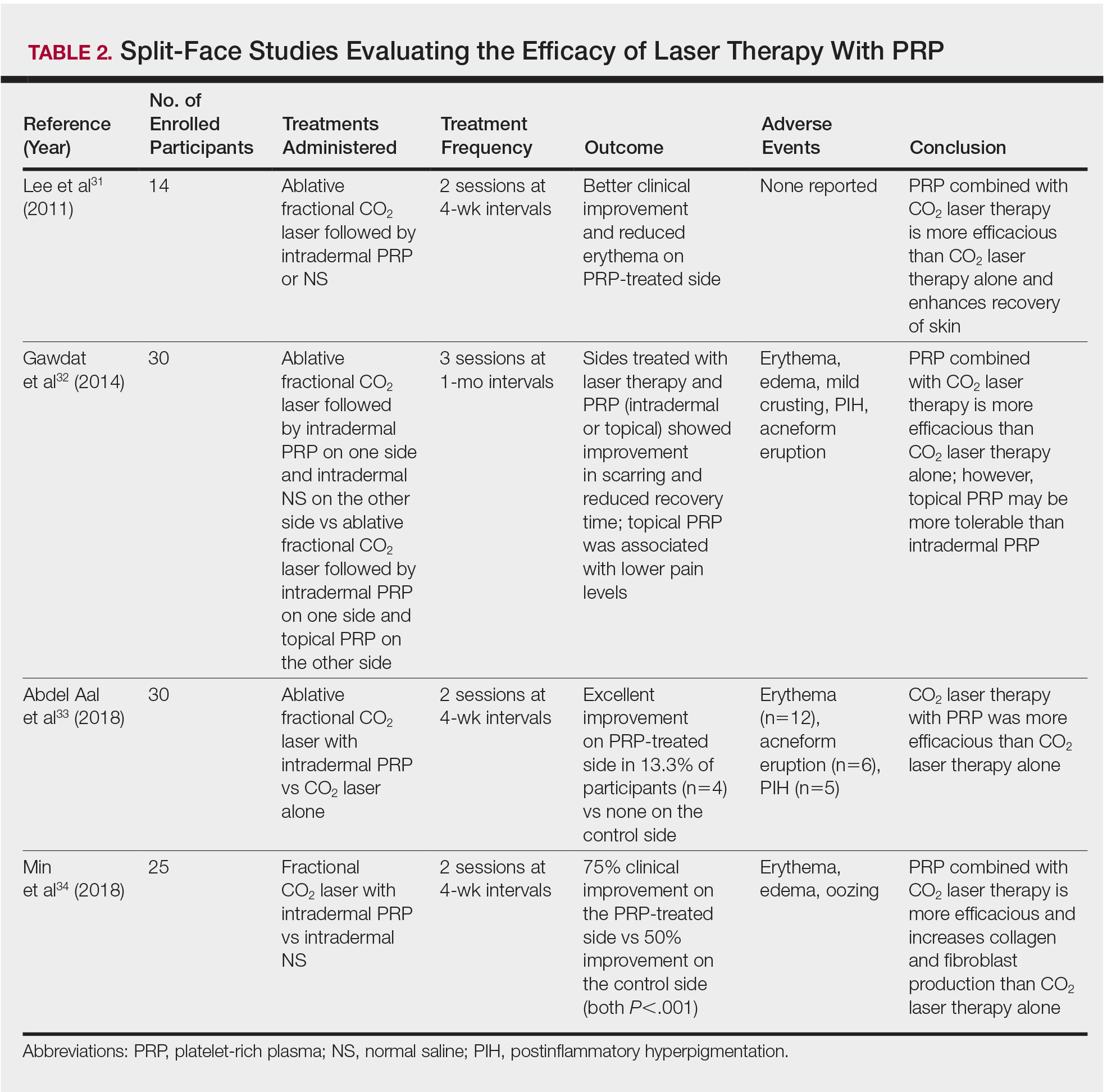

More recent studies have examined the use of laser therapy in addition to PRP for the treatment of acne scars (Table 2).31-34 Abdel Aal et al33 examined the use of the ablative fractional CO2 laser with and without intradermal PRP in a split-face study of 30 participants with various types of acne scarring (ie, boxcar, ice pick, and rolling scars). Participants underwent 2 treatments at 4-week intervals. Evaluations were performed by 2 blinded dermatologists 6 months after the final laser treatment using the qualitative Goodman and Baron scale.28 Both treatments yielded improvement in scarring, but the PRP-treated side showed shorter durations of postprocedure erythema (P=.0052) as well as higher patient satisfaction scores (P<.001) than laser therapy alone.33

In another split-face study, Gawdat et al32 examined combination treatment with the ablative fractional CO2 laser and PRP in 30 participants with atrophic acne scars graded 2 to 4 on the qualitative Goodman and Baron scale.28 Participants were randomized to 2 different treatment groups: In group 1, half of the face was treated with the fractional CO2 laser and intradermal PRP, while the other half was treated with fractional CO2 laser and intradermal saline. In group 2, half of the face was treated with fractional CO2 laser and intradermal PRP, while the other half was treated with fractional CO2 laser and topical PRP. All patients underwent 3 treatment sessions at 1-month intervals with assessment occurring a 6-month follow-up using the qualitative Goodman and Baron Scale.28 In all participants, areas treated with the combined laser and PRP showed significant improvement in scarring (P=.03) and reduced recovery time (P=.02) compared to areas treated with laser therapy only. Patients receiving intradermal or topical PRP showed no statistically significant differences in improvement of scarring or recovery time; however, areas treated with topical PRP had significantly lower pain levels (P=.005).32

Lee et al31 conducted a split-face study of 14 patients with moderate to severe acne scarring treated with an ablative fractional CO2 laser followed by intradermal PRP or intradermal normal saline injections. Patients underwent 2 treatment sessions at 4-week intervals. Photographs taken at baseline and 4 months posttreatment were evaluated by 2 blinded dermatologists for clinical improvement using a quartile grading system. Erythema was assessed using a skin color measuring device. A blinded dermatologist assessed patients for adverse events. At 4-month follow-up, mean (SD) clinical improvement on the side receiving intradermal PRP was significantly better than the control side (2.7 [0.7] vs 2.3 [0.5]; P=.03). Erythema on posttreatment day 4 was significantly less on the side treated with PRP (P=.01). No adverse events were reported.31

Another split-face study compared the use of intradermal PRP to intradermal normal saline following fractional CO2 laser treatment.34 Twenty-five participants with moderate to severe acne scars completed 2 treatment sessions at 4-week intervals. Additionally, skin biopsies were collected to evaluate collagen production using immunohistochemistry, quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and western blot techniques. Experimental fibroblasts and keratinocytes were isolated and cultured. The cultures were irradiated with a fractional CO2 laser and treated with PRP or platelet-poor plasma. Cultures were evaluated at 30 minutes, 24 hours, and 48 hours. Participants reported 75% improvement of acne scarring from baseline in the side treated with PRP compared to 50% improvement of acne scarring from baseline in the control group (P<.001). On days 7 and 84, participants reported greater improvement on the side treated with PRP (P=.03 and P=.02, respectively). On day 28, skin biopsy evaluation yielded higher levels of TGF-β1 (P=.02), TGF-β3 (P=.004), c-myc (P=.004), type I collagen (P=.03), and type III collagen (P=.03) on the PRP-treated side compared to the control side. Transforming growth factor β increases collagen and fibroblast production, while c-myc leads to cell cycle progression.35-37 Similarly, TGF-β1, TGF-β3, types I andIII collagen, and p-Akt were increased in all cultures treated with PRP and platelet-poor plasma in a dose-dependent manner.34 p-Akt is thought to regulate wound healing38; however, PRP-treated keratinocytes yielded increased epidermal growth factor receptor and decreased keratin-16 at 48 hours, which suggests PRP plays a role in increasing epithelization and reducing laser-induced keratinocyte damage.39 Adverse effects (eg, erythema, edema, oozing) were less frequent in the PRP-treated side.34

Chemical Peels

Chemical peels are widely used in the treatment of acne scarring.40 Peels improve scarring through destruction of the epidermal and/or dermal layers, leading to skin exfoliation, rejuvenation, and remodeling. Superficial peeling agents, which extend to the dermoepidermal junction, include resorcinol, tretinoin, glycolic acid, lactic acid, salicylic acid, and trichloroacetic acid (TCA) 10% to 35%.41 Medium-depth peeling agents extend to the upper reticular dermis and include phenol, TCA 35% to 50%, and Jessner solution (resorcinol, lactic acid, and salicylic acid in ethanol) followed by TCA 35%.41 Finally, the effects of deep peeling agents reach the mid reticular dermis and include the Baker-Gordon or Litton phenol formulas.41 Deep peels are associated with higher rates of adverse outcomes including infection, dyschromia, and scarring.41,42

An RCT was performed to evaluate the use of a deep phenol 60% peel compared to microneedling with a 1.5-mm roller device plus a TCA 20% peel in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.43 Twenty-four patients were randomly and evenly assigned to both treatment groups. The phenol group underwent a single treatment session, while the microneedling plus TCA group underwent 4 treatment sessions at 6-week intervals. Both groups were instructed to use daily topical tretinoin and hydroquinone 2% in the 2 weeks prior to treatment. Posttreatment results were evaluated using a quartile grading scale. Scarring improved from baseline by 75.12% (P<.001) in the phenol group and 69.43% (P<.001) in the microneedling plus TCA group, with no significant difference between groups. Adverse effects in the phenol group included erythema and hyperpigmentation, while adverse events in the microneedling plus TCA group included transient pain, edema, erythema, and desquamation.43

Another study compared the use of a TCA 15% peel with microneedling to PRP with microneedling and microneedling alone in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.44 Twenty-four patients were randomly assigned to the 3 treatment groups (8 to each group) and underwent 6 treatment sessions with 2-week intervals. A roller device with a 1.5-mm needle was used for microneedling. Microneedling plus TCA and microneedling plus PRP were significantly more effective than microneedling alone (P=.011 and P=.015, respectively); however, the TCA 15% peel with microneedling resulted in the largest increase in epidermal thickening. The investigators concluded that combined use of a TCA 15% peel and microneedling was the most effective in treating atrophic acne scarring.44

Dermal Fillers

Dermal or subcutaneous fillers are used to increase volume in depressed scars and stimulate the skin’s natural production.45 Tissue augmentation methods commonly are used for larger rolling acne scars. Options for filler materials include autologous fat, bovine, or human collagen derivatives; hyaluronic acid; and polymethyl methacrylate microspheres with collagen.45 Newer fillers are formulated with lidocaine to decrease pain associated with the procedure.46 Hyaluronic acid fillers provide natural volume correction and have limited potential to elicit an immune response due to their derivation from bacterial fermentation. Fillers using polymethyl methacrylate microspheres with collagen are permanent and effective, which may lead to reduced patient costs; however, they often are not a first choice for treatment.45,46 Furthermore, if dermal fillers consist of bovine collagen, it is necessary to perform skin testing for allergy prior to use. Autologous fat transfer also has become popular for treatment of acne scarring, especially because there is no risk of allergic reaction, as the patient’s own fat is used for correction.46 However, this method requires a high degree of skill, and results are unpredictable, generally lasting from 6 months to several years.

Therapies on the horizon include autologous cell therapy. A multicenter, double-blinded, placebo-controlled RCT examined the use of an autologous fibroblast filler in the treatment of bilateral, depressed, and distensible acne scars that were graded as moderate to severe.47 Autologous fat fibroblasts were harvested from full-thickness postauricular punch biopsies. In this split-face study, 99 participants were treated with an intradermal autologous fibroblast filler on one cheek and a protein-free cell-culture medium on the contralateral cheek. Participants received an average of 5.9 mL of both autologous fat fibroblasts and cell-culture medium over 3 treatment sessions at 2-week intervals. The autologous fat fibroblasts were associated with greater improvement compared to cell-culture medium based on participant (43% vs 18%), evaluator (59% vs 42%), and independent photographic viewer’s assessment.47

Conclusion

Acne scarring is a burden affecting millions of Americans. It often has a negative impact on quality of life and can lead to low self-esteem in patients. Numerous trials have indicated that microneedling is beneficial in the treatment of acne scarring, and emerging evidence indicates that the addition of PRP provides measurable benefits. Similarly, the addition of PRP to laser therapy may reduce recovery time as well as the commonly associated adverse events of erythema and pain. Chemical peels provide the advantage of being easily and efficiently performed in the office setting. Finally, the wide range of available dermal fillers can be tailored to treat specific types of acne scars. Autologous dermal fillers recently have been used and show promising benefits. It is important to consider desired outcome, cost, and adverse events when discussing therapeutic options for acne scarring with patients. The numerous therapeutic options warrant further research and well-designed RCTs to ensure optimal patient outcomes.

- White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 3):S34-S37.

- Yazici K, Baz K, Yazici AE, et al. Disease-specific quality of life is associated with anxiety and depression in patients with acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:435-439.

- Orentreich DS, Orentreich N. Subcutaneous incisionless (subcision) surgery for the correction of depressed scars and wrinkles. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:543-549.

- Fabbrocini G, De Padova M, De Vita V, et al. Periorbital wrinkles treatment using collagen induction therapy. Surg Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;1:106-111.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Pastore F, et al. Collagen induction therapy for the treatment of upper lip wrinkles. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23:144-152.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Di Costanzo L, et al. Skin needling in the treatment of the aging neck. Skinmed. 2011;9:347-351.

- El-Domyati M, Barakat M, Awad S, et al. Microneedling therapy for atrophic acne scars: an objective evaluation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-42.

- Fabbrocini G, Fardella N, Monfrecola A, et al. Acne scarring treatment using skin needling. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:874-879.

- Alam M, Han S, Pongprutthipan M, et al. Efficacy of a needling device for the treatment of acne scars: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:844-849.

- Dhurat R, Sukesh M, Avhad G, et al. A randomized evaluator blinded study of effect of microneedling in androgenetic alopecia: a pilot study. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:6-11.

- Dhurat R, Mathapati S. Response to microneedling treatment in men with androgenetic alopecia who failed to respond to conventional therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:260-263.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Fardella N, et al. Skin needling to enhance depigmenting serum penetration in the treatment of melasma [published online April 7, 2011]. Plast Surg Int. 2011;2011:158241.

- Bariya SH, Gohel MC, Mehta TA, et al. Microneedles: an emerging transdermal drug delivery system. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;64:11-29.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Izzo R, et al. The use of skin needling for the delivery of a eutectic mixture of local anesthetics. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149:581-585.

- De Vita V. How to choose among the multiple options to enhance the penetration of topically applied methyl aminolevulinate prior to photodynamic therapy [published online February 22, 2018]. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.02.014.

- Fernandes D. Minimally invasive percutaneous collagen induction. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005;17:51-63.

- Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring—a quantitative global scarring grading system. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2006;5:48-52.

- Majid I. Microneedling therapy in atrophic facial scars: an objective assessment. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009;2:26-30.

- Dogra S, Yadav S, Sarangal R. Microneedling for acne scars in Asian skin type: an effective low cost treatment modality. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014;13:180-187.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Monfrecola A, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction: an effective and safe treatment for post-acne scarring in different skin phototypes. J Dermatol Treat. 2014;25:147-152.

- Hashim PW, Levy Z, Cohen JL, et al. Microneedling therapy with and without platelet-rich plasma. Cutis. 2017;99:239-242.

- Wang HL, Avila G. Platelet rich plasma: myth or reality? Eur J Dent. 2007;1:192-194.

- Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:489-496.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Pastore F, et al. Combined use of skin needling and platelet-rich plasma in acne scarring treatment. Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;24:177-183.

- Chawla S. Split face comparative study of microneedling with PRP versus microneedling with vitamin C in treating atrophic post acne scars. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:209-212.

- Asif M, Kanodia S, Singh K. Combined autologous platelet-rich plasma with microneedling verses microneedling with distilled water in the treatment of atrophic acne scars: a concurrent split-face study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15:434-443.

- Ibrahim MK, Ibrahim SM, Salem AM. Skin microneedling plus platelet-rich plasma versus skin microneedling alone in the treatment of atrophic post acne scars: a split face comparative study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:281-286.

- Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring: a qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1458-1466.

- You H, Kim D, Yoon E, et al. Comparison of four different lasers for acne scars: resurfacing and fractional lasers. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:E87-E95.

- Osman MA, Shokeir HA, Fawzy MM. Fractional erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser versus microneedling in treatment of atrophic acne scars: a randomized split-face clinical study. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(suppl 1):S47-S56.

- Lee JW, Kim BJ, Kim MN, et al. The efficacy of autologous platelet rich plasma combined with ablative carbon dioxide fractional resurfacing for acne scars: a simultaneous split-face trial. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:931-938.

- Gawdat HI, Hegazy RA, Fawzy MM, et al. Autologous platelet rich plasma: topical versus intradermal after fractional ablative carbon dioxide laser treatment of atrophic acne scars. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:152-161.

- Abdel Aal AM, Ibrahim IM, Sami NA, et al. Evaluation of autologous platelet rich plasma plus ablative carbon dioxide fractional laser in the treatment of acne scars. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:106-113.

- Min S, Yoon JY, Park SY, et al. Combination of platelet rich plasma in fractional carbon dioxide laser treatment increased clinical efficacy of for acne scar by enhancement of collagen production and modulation of laser-induced inflammation. Lasers Surg Med. 2018;50:302-310.

- Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Assoian RK, et al. Transforming growth factor type beta: rapid induction of fibrosis and angiogenesis in vivo and stimulation of collagen formation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4167-4171.

- Schmidt EV. The role of c-myc in cellular growth control. Oncogene. 1999;18:2988-2996.

- Varga J, Rosenbloom J, Jimenez SA. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF beta) causes a persistent increase in steady-state amounts of type I and type III collagen and fibronectin mRNAs in normal human dermal fibroblasts. Biochem J. 1987;247:597-604.

- Chen J, Somanath PR, Razorenova O, et al. Akt1 regulates pathological angiogenesis, vascular maturation and permeability in vivo. Nat Med. 2005;11:1188-1196.

- Repertinger SK, Campagnaro E, Fuhrman J, et al. EGFR enhances early healing after cutaneous incisional wounding. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:982-989.

- Landau M. Chemical peels. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:200-208.

- Drake LA, Dinehart SM, Goltz RW, et al. Guidelines of care for chemical peeling. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:497-503.

- Meaike JD, Agrawal N, Chang D, et al. Noninvasive facial rejuvenation. part 3: physician-directed-lasers, chemical peels, and other noninvasive modalities. Semin Plast Surg. 2016;30:143-150.

- Leheta TM, Abdel Hay RM, El Garem YF. Deep peeling using phenol versus percutaneous collagen induction combined with trichloroacetic acid 20% in atrophic post-acne scars; a randomized controlled trial.J Dermatol Treat. 2014;25:130-136.

- El-Domyati M, Abdel-Wahab H, Hossam A. Microneedling combined with platelet-rich plasma or trichloroacetic acid peeling for management of acne scarring: a split-face clinical and histologic comparison.J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:73-83.

- Hession MT, Graber EM. Atrophic acne scarring: a review of treatment options. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:50-58.

- Dayan SH, Bassichis BA. Facial dermal fillers: selection of appropriate products and techniques. Aesthet Surg J. 2008;28:335-347.

- Munavalli GS, Smith S, Maslowski JM, et al. Successful treatment of depressed, distensible acne scars using autologous fibroblasts: a multi-site, prospective, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1226-1236.

Acne vulgaris is prevalent in the general population, with 40 to 50 million affected individuals in the United States.1 Severe inflammation and injury can lead to disfiguring scarring, which has a considerable impact on quality of life.2 Numerous therapeutic options for acne scarring are available, including microneedling with and without platelet-rich plasma (PRP), lasers, chemical peels, and dermal fillers, with different modalities suited to individual patients and scar characteristics. This article reviews updates in treatment options for acne scarring.

Microneedling

Microneedling, also known as percutaneous collagen induction or collagen induction therapy, has been utilized for more than 2 decades.3 Dermatologic indications for microneedling include skin rejuvenation,4-6 atrophic acne scarring,7-9 and androgenic alopecia.10,11 Microneedling also has been used to enhance skin penetration of topically applied drugs.12-15 Fernandes16 described percutaneous collagen induction as the skin’s natural response to injury. Microneedling creates small wounds as fine needles puncture the epidermis and dermis, resulting in a cascade of growth factors that lead to tissue proliferation, regeneration, and a collagen remodeling phase that can last for several months.8,16

Microneedling has gained popularity in the treatment of acne scarring.7 Alam et al9 conducted a split-face randomized clinical trial (RCT) to evaluate acne scarring after 3 microneedling sessions performed at 2-week intervals. Twenty participants with acne scarring on both sides of the face were enrolled in the study and one side of the face was randomized for treatment. Participants had at least two 5×5-cm areas of acne scarring graded as 2 (moderately atrophic scars) to 4 (hyperplastic or papular scars) on the quantitative Global Acne Scarring Classification system. A roller device with a 1.0-mm depth was used on participants with fine, less sebaceous skin and a 2.0-mm device for all others. Two blinded investigators assessed acne scars at baseline and at 3 and 6 months after treatment. Scar improvement was measured using the quantitative Goodman and Baron scale, which provides a score according to type and number of scars.17 Mean scar scores were significantly reduced at 6 months compared to baseline on the treatment side (P=.03) but not the control side. Participants experienced minimal pain associated with microneedling therapy, rated 1.08 of 10, and adverse effects were limited to mild transient erythema and edema.9 Several other clinical trials have demonstrated clinical improvements with microneedling.18-20

The benefits of microneedling also have been observed on a histologic level. One group of investigators explored the effects of microneedling on dermal collagen in the treatment of various atrophic acne scars in 10 participants.7 After 6 treatment sessions performed at 2-week intervals, dermal collagen was assessed via punch biopsy. A roller device with a needle depth of 1.5 mm was used for all patients. At 1 month after treatment compared to baseline, mean (SD) levels of type I collagen were significantly increased (67.1% [4.2%] vs 70.4% [5.4%]; P=.01) as well as at 3 months after treatment compared to baseline for type III collagen (61.4% [3.6%] vs 74.3% [7.4%]; P=.01), type VII collagen (15.2% [2.1%] vs 21.3% [1.2%]; P=.03), and newly synthesized collagen (14.5% [5.8%] vs 19.5% [3.2%]; P=.02). Total elastin levels were significantly decreased at 3 months after treatment compared to baseline (51.3% [6.7%] vs 46.9% [4.3%]; P=.04). Adverse effects were limited to transient erythema and edema.7

Microneedling With Platelet-Rich Plasma

Microneedling has been combined with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.21 In addition to inducing new collagen synthesis, microneedling aids in the absorption of PRP, an autologous concentrate of platelets that is obtained through peripheral venipuncture. The concentrate is centrifuged into 3 layers: (1) platelet-poor plasma, (2) PRP, and (3) erythrocytes.22 Platelet-rich plasma contains growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor (TGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor, as well as cell adhesion molecules.22,23 The application of PRP is thought to result in upregulated protein synthesis, greater collagen remodeling, and accelerated wound healing.21

Several studies have shown that the addition of PRP to microneedling can improve treatment outcome (Table 1).24-27 Severity of acne scarring can be improved, such as reduced scar depth, by using both modalities synergistically (Figure).24 Asif et al26 compared microneedling with PRP to microneedling with distilled water in the treatment of 50 patients with atrophic acne scars graded 2 to 4 (mild to severe acne scarring) on the Goodman’s Qualitative classification and equal Goodman’s Qualitative and Quantitative scores on both halves of the face.17,28 The right side of the face was treated with a 1.5-mm microneedling roller with intradermal and topical PRP, while the left side was treated with distilled water (placebo) delivered intradermally. Patients underwent 3 treatment sessions at 1-month intervals. The area treated with microneedling and PRP showed a 62.20% improvement from baseline after 3 treatments, while the placebo-treated area showed a 45.84% improvement on the Goodman and Baron quantitative scale.26

Chawla25 compared microneedling with topical PRP to microneedling with topical vitamin C in a split-face study of 30 participants with atrophic acne scarring graded 2 to 4 on the Goodman and Baron scale. A 1.5-mm roller device was used. Patients underwent 4 treatment sessions at 1-month intervals, and treatment efficacy was evaluated using the qualitative Goodman and Baron scale.28 Participants experienced positive outcomes overall with both treatments. Notably, 18.5% (5/27) on the microneedling with PRP side demonstrated excellent response compared to 7.4% (2/27) on the microneedling with vitamin C side.25

Laser Treatment

Laser skin resurfacing has shown to be efficacious in the treatment of both acne vulgaris and acne scarring. Various lasers have been utilized, including nonfractional CO2 and erbium-doped:YAG (Er:YAG) lasers, as well as ablative fractional lasers (AFLs) and nonablative fractional lasers (NAFLs).29

One retrospective study of 58 patients compared the use of 2 resurfacing lasers—10,600-nm nonfractional CO2 and 2940-nm Er:YAG—and 2 fractional lasers—1550-nm NAFL and 10,600-nm AFL—in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.29 A retrospective photographic analysis was performed by 6 blinded dermatologists to evaluate clinical improvement on a scale of 0 (no improvement) to 10 (excellent improvement). The mean improvement scores of the CO2, Er:YAG, AFL, and NAFL groups were 6.0, 5.8, 2.2, and 5.2, respectively, and the mean number of treatments was 1.6, 1.1, 4.0, and 3.4, respectively. Thus, patients in the fractional laser groups required more treatments; however, those in the resurfacing laser groups had longer recovery times, pain, erythema, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The investigators concluded that 3 consecutive AFL treatments could be as effective as a single resurfacing treatment with lower risk for complications.29

A split-face RCT compared the use of the fractional Er:YAG laser on one side of the face to microneedling with a 2.0-mm needle on the other side for treatment of atrophic acne scars.30 Thirty patients underwent 5 treatments at 1-month intervals. At 3-month follow-up, the areas treated with the Er:YAG laser showed 70% improvement from baseline compared to 30% improvement in the areas treated with microneedling (P<.001). Histologically, the Er:YAG laser showed a higher increase in dermal collagen than microneedling (P<.001). Furthermore, the Er:YAG laser yielded significantly lower pain scores (P<.001); however, patients reported higher rates of erythema, swelling, superficial crusting, and total downtime.30

Lasers With PRP

More recent studies have examined the use of laser therapy in addition to PRP for the treatment of acne scars (Table 2).31-34 Abdel Aal et al33 examined the use of the ablative fractional CO2 laser with and without intradermal PRP in a split-face study of 30 participants with various types of acne scarring (ie, boxcar, ice pick, and rolling scars). Participants underwent 2 treatments at 4-week intervals. Evaluations were performed by 2 blinded dermatologists 6 months after the final laser treatment using the qualitative Goodman and Baron scale.28 Both treatments yielded improvement in scarring, but the PRP-treated side showed shorter durations of postprocedure erythema (P=.0052) as well as higher patient satisfaction scores (P<.001) than laser therapy alone.33

In another split-face study, Gawdat et al32 examined combination treatment with the ablative fractional CO2 laser and PRP in 30 participants with atrophic acne scars graded 2 to 4 on the qualitative Goodman and Baron scale.28 Participants were randomized to 2 different treatment groups: In group 1, half of the face was treated with the fractional CO2 laser and intradermal PRP, while the other half was treated with fractional CO2 laser and intradermal saline. In group 2, half of the face was treated with fractional CO2 laser and intradermal PRP, while the other half was treated with fractional CO2 laser and topical PRP. All patients underwent 3 treatment sessions at 1-month intervals with assessment occurring a 6-month follow-up using the qualitative Goodman and Baron Scale.28 In all participants, areas treated with the combined laser and PRP showed significant improvement in scarring (P=.03) and reduced recovery time (P=.02) compared to areas treated with laser therapy only. Patients receiving intradermal or topical PRP showed no statistically significant differences in improvement of scarring or recovery time; however, areas treated with topical PRP had significantly lower pain levels (P=.005).32

Lee et al31 conducted a split-face study of 14 patients with moderate to severe acne scarring treated with an ablative fractional CO2 laser followed by intradermal PRP or intradermal normal saline injections. Patients underwent 2 treatment sessions at 4-week intervals. Photographs taken at baseline and 4 months posttreatment were evaluated by 2 blinded dermatologists for clinical improvement using a quartile grading system. Erythema was assessed using a skin color measuring device. A blinded dermatologist assessed patients for adverse events. At 4-month follow-up, mean (SD) clinical improvement on the side receiving intradermal PRP was significantly better than the control side (2.7 [0.7] vs 2.3 [0.5]; P=.03). Erythema on posttreatment day 4 was significantly less on the side treated with PRP (P=.01). No adverse events were reported.31

Another split-face study compared the use of intradermal PRP to intradermal normal saline following fractional CO2 laser treatment.34 Twenty-five participants with moderate to severe acne scars completed 2 treatment sessions at 4-week intervals. Additionally, skin biopsies were collected to evaluate collagen production using immunohistochemistry, quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and western blot techniques. Experimental fibroblasts and keratinocytes were isolated and cultured. The cultures were irradiated with a fractional CO2 laser and treated with PRP or platelet-poor plasma. Cultures were evaluated at 30 minutes, 24 hours, and 48 hours. Participants reported 75% improvement of acne scarring from baseline in the side treated with PRP compared to 50% improvement of acne scarring from baseline in the control group (P<.001). On days 7 and 84, participants reported greater improvement on the side treated with PRP (P=.03 and P=.02, respectively). On day 28, skin biopsy evaluation yielded higher levels of TGF-β1 (P=.02), TGF-β3 (P=.004), c-myc (P=.004), type I collagen (P=.03), and type III collagen (P=.03) on the PRP-treated side compared to the control side. Transforming growth factor β increases collagen and fibroblast production, while c-myc leads to cell cycle progression.35-37 Similarly, TGF-β1, TGF-β3, types I andIII collagen, and p-Akt were increased in all cultures treated with PRP and platelet-poor plasma in a dose-dependent manner.34 p-Akt is thought to regulate wound healing38; however, PRP-treated keratinocytes yielded increased epidermal growth factor receptor and decreased keratin-16 at 48 hours, which suggests PRP plays a role in increasing epithelization and reducing laser-induced keratinocyte damage.39 Adverse effects (eg, erythema, edema, oozing) were less frequent in the PRP-treated side.34

Chemical Peels

Chemical peels are widely used in the treatment of acne scarring.40 Peels improve scarring through destruction of the epidermal and/or dermal layers, leading to skin exfoliation, rejuvenation, and remodeling. Superficial peeling agents, which extend to the dermoepidermal junction, include resorcinol, tretinoin, glycolic acid, lactic acid, salicylic acid, and trichloroacetic acid (TCA) 10% to 35%.41 Medium-depth peeling agents extend to the upper reticular dermis and include phenol, TCA 35% to 50%, and Jessner solution (resorcinol, lactic acid, and salicylic acid in ethanol) followed by TCA 35%.41 Finally, the effects of deep peeling agents reach the mid reticular dermis and include the Baker-Gordon or Litton phenol formulas.41 Deep peels are associated with higher rates of adverse outcomes including infection, dyschromia, and scarring.41,42

An RCT was performed to evaluate the use of a deep phenol 60% peel compared to microneedling with a 1.5-mm roller device plus a TCA 20% peel in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.43 Twenty-four patients were randomly and evenly assigned to both treatment groups. The phenol group underwent a single treatment session, while the microneedling plus TCA group underwent 4 treatment sessions at 6-week intervals. Both groups were instructed to use daily topical tretinoin and hydroquinone 2% in the 2 weeks prior to treatment. Posttreatment results were evaluated using a quartile grading scale. Scarring improved from baseline by 75.12% (P<.001) in the phenol group and 69.43% (P<.001) in the microneedling plus TCA group, with no significant difference between groups. Adverse effects in the phenol group included erythema and hyperpigmentation, while adverse events in the microneedling plus TCA group included transient pain, edema, erythema, and desquamation.43

Another study compared the use of a TCA 15% peel with microneedling to PRP with microneedling and microneedling alone in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.44 Twenty-four patients were randomly assigned to the 3 treatment groups (8 to each group) and underwent 6 treatment sessions with 2-week intervals. A roller device with a 1.5-mm needle was used for microneedling. Microneedling plus TCA and microneedling plus PRP were significantly more effective than microneedling alone (P=.011 and P=.015, respectively); however, the TCA 15% peel with microneedling resulted in the largest increase in epidermal thickening. The investigators concluded that combined use of a TCA 15% peel and microneedling was the most effective in treating atrophic acne scarring.44

Dermal Fillers

Dermal or subcutaneous fillers are used to increase volume in depressed scars and stimulate the skin’s natural production.45 Tissue augmentation methods commonly are used for larger rolling acne scars. Options for filler materials include autologous fat, bovine, or human collagen derivatives; hyaluronic acid; and polymethyl methacrylate microspheres with collagen.45 Newer fillers are formulated with lidocaine to decrease pain associated with the procedure.46 Hyaluronic acid fillers provide natural volume correction and have limited potential to elicit an immune response due to their derivation from bacterial fermentation. Fillers using polymethyl methacrylate microspheres with collagen are permanent and effective, which may lead to reduced patient costs; however, they often are not a first choice for treatment.45,46 Furthermore, if dermal fillers consist of bovine collagen, it is necessary to perform skin testing for allergy prior to use. Autologous fat transfer also has become popular for treatment of acne scarring, especially because there is no risk of allergic reaction, as the patient’s own fat is used for correction.46 However, this method requires a high degree of skill, and results are unpredictable, generally lasting from 6 months to several years.

Therapies on the horizon include autologous cell therapy. A multicenter, double-blinded, placebo-controlled RCT examined the use of an autologous fibroblast filler in the treatment of bilateral, depressed, and distensible acne scars that were graded as moderate to severe.47 Autologous fat fibroblasts were harvested from full-thickness postauricular punch biopsies. In this split-face study, 99 participants were treated with an intradermal autologous fibroblast filler on one cheek and a protein-free cell-culture medium on the contralateral cheek. Participants received an average of 5.9 mL of both autologous fat fibroblasts and cell-culture medium over 3 treatment sessions at 2-week intervals. The autologous fat fibroblasts were associated with greater improvement compared to cell-culture medium based on participant (43% vs 18%), evaluator (59% vs 42%), and independent photographic viewer’s assessment.47

Conclusion

Acne scarring is a burden affecting millions of Americans. It often has a negative impact on quality of life and can lead to low self-esteem in patients. Numerous trials have indicated that microneedling is beneficial in the treatment of acne scarring, and emerging evidence indicates that the addition of PRP provides measurable benefits. Similarly, the addition of PRP to laser therapy may reduce recovery time as well as the commonly associated adverse events of erythema and pain. Chemical peels provide the advantage of being easily and efficiently performed in the office setting. Finally, the wide range of available dermal fillers can be tailored to treat specific types of acne scars. Autologous dermal fillers recently have been used and show promising benefits. It is important to consider desired outcome, cost, and adverse events when discussing therapeutic options for acne scarring with patients. The numerous therapeutic options warrant further research and well-designed RCTs to ensure optimal patient outcomes.

Acne vulgaris is prevalent in the general population, with 40 to 50 million affected individuals in the United States.1 Severe inflammation and injury can lead to disfiguring scarring, which has a considerable impact on quality of life.2 Numerous therapeutic options for acne scarring are available, including microneedling with and without platelet-rich plasma (PRP), lasers, chemical peels, and dermal fillers, with different modalities suited to individual patients and scar characteristics. This article reviews updates in treatment options for acne scarring.

Microneedling

Microneedling, also known as percutaneous collagen induction or collagen induction therapy, has been utilized for more than 2 decades.3 Dermatologic indications for microneedling include skin rejuvenation,4-6 atrophic acne scarring,7-9 and androgenic alopecia.10,11 Microneedling also has been used to enhance skin penetration of topically applied drugs.12-15 Fernandes16 described percutaneous collagen induction as the skin’s natural response to injury. Microneedling creates small wounds as fine needles puncture the epidermis and dermis, resulting in a cascade of growth factors that lead to tissue proliferation, regeneration, and a collagen remodeling phase that can last for several months.8,16

Microneedling has gained popularity in the treatment of acne scarring.7 Alam et al9 conducted a split-face randomized clinical trial (RCT) to evaluate acne scarring after 3 microneedling sessions performed at 2-week intervals. Twenty participants with acne scarring on both sides of the face were enrolled in the study and one side of the face was randomized for treatment. Participants had at least two 5×5-cm areas of acne scarring graded as 2 (moderately atrophic scars) to 4 (hyperplastic or papular scars) on the quantitative Global Acne Scarring Classification system. A roller device with a 1.0-mm depth was used on participants with fine, less sebaceous skin and a 2.0-mm device for all others. Two blinded investigators assessed acne scars at baseline and at 3 and 6 months after treatment. Scar improvement was measured using the quantitative Goodman and Baron scale, which provides a score according to type and number of scars.17 Mean scar scores were significantly reduced at 6 months compared to baseline on the treatment side (P=.03) but not the control side. Participants experienced minimal pain associated with microneedling therapy, rated 1.08 of 10, and adverse effects were limited to mild transient erythema and edema.9 Several other clinical trials have demonstrated clinical improvements with microneedling.18-20

The benefits of microneedling also have been observed on a histologic level. One group of investigators explored the effects of microneedling on dermal collagen in the treatment of various atrophic acne scars in 10 participants.7 After 6 treatment sessions performed at 2-week intervals, dermal collagen was assessed via punch biopsy. A roller device with a needle depth of 1.5 mm was used for all patients. At 1 month after treatment compared to baseline, mean (SD) levels of type I collagen were significantly increased (67.1% [4.2%] vs 70.4% [5.4%]; P=.01) as well as at 3 months after treatment compared to baseline for type III collagen (61.4% [3.6%] vs 74.3% [7.4%]; P=.01), type VII collagen (15.2% [2.1%] vs 21.3% [1.2%]; P=.03), and newly synthesized collagen (14.5% [5.8%] vs 19.5% [3.2%]; P=.02). Total elastin levels were significantly decreased at 3 months after treatment compared to baseline (51.3% [6.7%] vs 46.9% [4.3%]; P=.04). Adverse effects were limited to transient erythema and edema.7

Microneedling With Platelet-Rich Plasma

Microneedling has been combined with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.21 In addition to inducing new collagen synthesis, microneedling aids in the absorption of PRP, an autologous concentrate of platelets that is obtained through peripheral venipuncture. The concentrate is centrifuged into 3 layers: (1) platelet-poor plasma, (2) PRP, and (3) erythrocytes.22 Platelet-rich plasma contains growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor (TGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor, as well as cell adhesion molecules.22,23 The application of PRP is thought to result in upregulated protein synthesis, greater collagen remodeling, and accelerated wound healing.21

Several studies have shown that the addition of PRP to microneedling can improve treatment outcome (Table 1).24-27 Severity of acne scarring can be improved, such as reduced scar depth, by using both modalities synergistically (Figure).24 Asif et al26 compared microneedling with PRP to microneedling with distilled water in the treatment of 50 patients with atrophic acne scars graded 2 to 4 (mild to severe acne scarring) on the Goodman’s Qualitative classification and equal Goodman’s Qualitative and Quantitative scores on both halves of the face.17,28 The right side of the face was treated with a 1.5-mm microneedling roller with intradermal and topical PRP, while the left side was treated with distilled water (placebo) delivered intradermally. Patients underwent 3 treatment sessions at 1-month intervals. The area treated with microneedling and PRP showed a 62.20% improvement from baseline after 3 treatments, while the placebo-treated area showed a 45.84% improvement on the Goodman and Baron quantitative scale.26

Chawla25 compared microneedling with topical PRP to microneedling with topical vitamin C in a split-face study of 30 participants with atrophic acne scarring graded 2 to 4 on the Goodman and Baron scale. A 1.5-mm roller device was used. Patients underwent 4 treatment sessions at 1-month intervals, and treatment efficacy was evaluated using the qualitative Goodman and Baron scale.28 Participants experienced positive outcomes overall with both treatments. Notably, 18.5% (5/27) on the microneedling with PRP side demonstrated excellent response compared to 7.4% (2/27) on the microneedling with vitamin C side.25

Laser Treatment

Laser skin resurfacing has shown to be efficacious in the treatment of both acne vulgaris and acne scarring. Various lasers have been utilized, including nonfractional CO2 and erbium-doped:YAG (Er:YAG) lasers, as well as ablative fractional lasers (AFLs) and nonablative fractional lasers (NAFLs).29

One retrospective study of 58 patients compared the use of 2 resurfacing lasers—10,600-nm nonfractional CO2 and 2940-nm Er:YAG—and 2 fractional lasers—1550-nm NAFL and 10,600-nm AFL—in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.29 A retrospective photographic analysis was performed by 6 blinded dermatologists to evaluate clinical improvement on a scale of 0 (no improvement) to 10 (excellent improvement). The mean improvement scores of the CO2, Er:YAG, AFL, and NAFL groups were 6.0, 5.8, 2.2, and 5.2, respectively, and the mean number of treatments was 1.6, 1.1, 4.0, and 3.4, respectively. Thus, patients in the fractional laser groups required more treatments; however, those in the resurfacing laser groups had longer recovery times, pain, erythema, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The investigators concluded that 3 consecutive AFL treatments could be as effective as a single resurfacing treatment with lower risk for complications.29

A split-face RCT compared the use of the fractional Er:YAG laser on one side of the face to microneedling with a 2.0-mm needle on the other side for treatment of atrophic acne scars.30 Thirty patients underwent 5 treatments at 1-month intervals. At 3-month follow-up, the areas treated with the Er:YAG laser showed 70% improvement from baseline compared to 30% improvement in the areas treated with microneedling (P<.001). Histologically, the Er:YAG laser showed a higher increase in dermal collagen than microneedling (P<.001). Furthermore, the Er:YAG laser yielded significantly lower pain scores (P<.001); however, patients reported higher rates of erythema, swelling, superficial crusting, and total downtime.30

Lasers With PRP

More recent studies have examined the use of laser therapy in addition to PRP for the treatment of acne scars (Table 2).31-34 Abdel Aal et al33 examined the use of the ablative fractional CO2 laser with and without intradermal PRP in a split-face study of 30 participants with various types of acne scarring (ie, boxcar, ice pick, and rolling scars). Participants underwent 2 treatments at 4-week intervals. Evaluations were performed by 2 blinded dermatologists 6 months after the final laser treatment using the qualitative Goodman and Baron scale.28 Both treatments yielded improvement in scarring, but the PRP-treated side showed shorter durations of postprocedure erythema (P=.0052) as well as higher patient satisfaction scores (P<.001) than laser therapy alone.33

In another split-face study, Gawdat et al32 examined combination treatment with the ablative fractional CO2 laser and PRP in 30 participants with atrophic acne scars graded 2 to 4 on the qualitative Goodman and Baron scale.28 Participants were randomized to 2 different treatment groups: In group 1, half of the face was treated with the fractional CO2 laser and intradermal PRP, while the other half was treated with fractional CO2 laser and intradermal saline. In group 2, half of the face was treated with fractional CO2 laser and intradermal PRP, while the other half was treated with fractional CO2 laser and topical PRP. All patients underwent 3 treatment sessions at 1-month intervals with assessment occurring a 6-month follow-up using the qualitative Goodman and Baron Scale.28 In all participants, areas treated with the combined laser and PRP showed significant improvement in scarring (P=.03) and reduced recovery time (P=.02) compared to areas treated with laser therapy only. Patients receiving intradermal or topical PRP showed no statistically significant differences in improvement of scarring or recovery time; however, areas treated with topical PRP had significantly lower pain levels (P=.005).32

Lee et al31 conducted a split-face study of 14 patients with moderate to severe acne scarring treated with an ablative fractional CO2 laser followed by intradermal PRP or intradermal normal saline injections. Patients underwent 2 treatment sessions at 4-week intervals. Photographs taken at baseline and 4 months posttreatment were evaluated by 2 blinded dermatologists for clinical improvement using a quartile grading system. Erythema was assessed using a skin color measuring device. A blinded dermatologist assessed patients for adverse events. At 4-month follow-up, mean (SD) clinical improvement on the side receiving intradermal PRP was significantly better than the control side (2.7 [0.7] vs 2.3 [0.5]; P=.03). Erythema on posttreatment day 4 was significantly less on the side treated with PRP (P=.01). No adverse events were reported.31

Another split-face study compared the use of intradermal PRP to intradermal normal saline following fractional CO2 laser treatment.34 Twenty-five participants with moderate to severe acne scars completed 2 treatment sessions at 4-week intervals. Additionally, skin biopsies were collected to evaluate collagen production using immunohistochemistry, quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and western blot techniques. Experimental fibroblasts and keratinocytes were isolated and cultured. The cultures were irradiated with a fractional CO2 laser and treated with PRP or platelet-poor plasma. Cultures were evaluated at 30 minutes, 24 hours, and 48 hours. Participants reported 75% improvement of acne scarring from baseline in the side treated with PRP compared to 50% improvement of acne scarring from baseline in the control group (P<.001). On days 7 and 84, participants reported greater improvement on the side treated with PRP (P=.03 and P=.02, respectively). On day 28, skin biopsy evaluation yielded higher levels of TGF-β1 (P=.02), TGF-β3 (P=.004), c-myc (P=.004), type I collagen (P=.03), and type III collagen (P=.03) on the PRP-treated side compared to the control side. Transforming growth factor β increases collagen and fibroblast production, while c-myc leads to cell cycle progression.35-37 Similarly, TGF-β1, TGF-β3, types I andIII collagen, and p-Akt were increased in all cultures treated with PRP and platelet-poor plasma in a dose-dependent manner.34 p-Akt is thought to regulate wound healing38; however, PRP-treated keratinocytes yielded increased epidermal growth factor receptor and decreased keratin-16 at 48 hours, which suggests PRP plays a role in increasing epithelization and reducing laser-induced keratinocyte damage.39 Adverse effects (eg, erythema, edema, oozing) were less frequent in the PRP-treated side.34

Chemical Peels

Chemical peels are widely used in the treatment of acne scarring.40 Peels improve scarring through destruction of the epidermal and/or dermal layers, leading to skin exfoliation, rejuvenation, and remodeling. Superficial peeling agents, which extend to the dermoepidermal junction, include resorcinol, tretinoin, glycolic acid, lactic acid, salicylic acid, and trichloroacetic acid (TCA) 10% to 35%.41 Medium-depth peeling agents extend to the upper reticular dermis and include phenol, TCA 35% to 50%, and Jessner solution (resorcinol, lactic acid, and salicylic acid in ethanol) followed by TCA 35%.41 Finally, the effects of deep peeling agents reach the mid reticular dermis and include the Baker-Gordon or Litton phenol formulas.41 Deep peels are associated with higher rates of adverse outcomes including infection, dyschromia, and scarring.41,42

An RCT was performed to evaluate the use of a deep phenol 60% peel compared to microneedling with a 1.5-mm roller device plus a TCA 20% peel in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.43 Twenty-four patients were randomly and evenly assigned to both treatment groups. The phenol group underwent a single treatment session, while the microneedling plus TCA group underwent 4 treatment sessions at 6-week intervals. Both groups were instructed to use daily topical tretinoin and hydroquinone 2% in the 2 weeks prior to treatment. Posttreatment results were evaluated using a quartile grading scale. Scarring improved from baseline by 75.12% (P<.001) in the phenol group and 69.43% (P<.001) in the microneedling plus TCA group, with no significant difference between groups. Adverse effects in the phenol group included erythema and hyperpigmentation, while adverse events in the microneedling plus TCA group included transient pain, edema, erythema, and desquamation.43

Another study compared the use of a TCA 15% peel with microneedling to PRP with microneedling and microneedling alone in the treatment of atrophic acne scars.44 Twenty-four patients were randomly assigned to the 3 treatment groups (8 to each group) and underwent 6 treatment sessions with 2-week intervals. A roller device with a 1.5-mm needle was used for microneedling. Microneedling plus TCA and microneedling plus PRP were significantly more effective than microneedling alone (P=.011 and P=.015, respectively); however, the TCA 15% peel with microneedling resulted in the largest increase in epidermal thickening. The investigators concluded that combined use of a TCA 15% peel and microneedling was the most effective in treating atrophic acne scarring.44

Dermal Fillers

Dermal or subcutaneous fillers are used to increase volume in depressed scars and stimulate the skin’s natural production.45 Tissue augmentation methods commonly are used for larger rolling acne scars. Options for filler materials include autologous fat, bovine, or human collagen derivatives; hyaluronic acid; and polymethyl methacrylate microspheres with collagen.45 Newer fillers are formulated with lidocaine to decrease pain associated with the procedure.46 Hyaluronic acid fillers provide natural volume correction and have limited potential to elicit an immune response due to their derivation from bacterial fermentation. Fillers using polymethyl methacrylate microspheres with collagen are permanent and effective, which may lead to reduced patient costs; however, they often are not a first choice for treatment.45,46 Furthermore, if dermal fillers consist of bovine collagen, it is necessary to perform skin testing for allergy prior to use. Autologous fat transfer also has become popular for treatment of acne scarring, especially because there is no risk of allergic reaction, as the patient’s own fat is used for correction.46 However, this method requires a high degree of skill, and results are unpredictable, generally lasting from 6 months to several years.

Therapies on the horizon include autologous cell therapy. A multicenter, double-blinded, placebo-controlled RCT examined the use of an autologous fibroblast filler in the treatment of bilateral, depressed, and distensible acne scars that were graded as moderate to severe.47 Autologous fat fibroblasts were harvested from full-thickness postauricular punch biopsies. In this split-face study, 99 participants were treated with an intradermal autologous fibroblast filler on one cheek and a protein-free cell-culture medium on the contralateral cheek. Participants received an average of 5.9 mL of both autologous fat fibroblasts and cell-culture medium over 3 treatment sessions at 2-week intervals. The autologous fat fibroblasts were associated with greater improvement compared to cell-culture medium based on participant (43% vs 18%), evaluator (59% vs 42%), and independent photographic viewer’s assessment.47

Conclusion

Acne scarring is a burden affecting millions of Americans. It often has a negative impact on quality of life and can lead to low self-esteem in patients. Numerous trials have indicated that microneedling is beneficial in the treatment of acne scarring, and emerging evidence indicates that the addition of PRP provides measurable benefits. Similarly, the addition of PRP to laser therapy may reduce recovery time as well as the commonly associated adverse events of erythema and pain. Chemical peels provide the advantage of being easily and efficiently performed in the office setting. Finally, the wide range of available dermal fillers can be tailored to treat specific types of acne scars. Autologous dermal fillers recently have been used and show promising benefits. It is important to consider desired outcome, cost, and adverse events when discussing therapeutic options for acne scarring with patients. The numerous therapeutic options warrant further research and well-designed RCTs to ensure optimal patient outcomes.

- White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 3):S34-S37.

- Yazici K, Baz K, Yazici AE, et al. Disease-specific quality of life is associated with anxiety and depression in patients with acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:435-439.

- Orentreich DS, Orentreich N. Subcutaneous incisionless (subcision) surgery for the correction of depressed scars and wrinkles. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:543-549.

- Fabbrocini G, De Padova M, De Vita V, et al. Periorbital wrinkles treatment using collagen induction therapy. Surg Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;1:106-111.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Pastore F, et al. Collagen induction therapy for the treatment of upper lip wrinkles. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23:144-152.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Di Costanzo L, et al. Skin needling in the treatment of the aging neck. Skinmed. 2011;9:347-351.

- El-Domyati M, Barakat M, Awad S, et al. Microneedling therapy for atrophic acne scars: an objective evaluation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-42.

- Fabbrocini G, Fardella N, Monfrecola A, et al. Acne scarring treatment using skin needling. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:874-879.

- Alam M, Han S, Pongprutthipan M, et al. Efficacy of a needling device for the treatment of acne scars: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:844-849.

- Dhurat R, Sukesh M, Avhad G, et al. A randomized evaluator blinded study of effect of microneedling in androgenetic alopecia: a pilot study. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:6-11.

- Dhurat R, Mathapati S. Response to microneedling treatment in men with androgenetic alopecia who failed to respond to conventional therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:260-263.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Fardella N, et al. Skin needling to enhance depigmenting serum penetration in the treatment of melasma [published online April 7, 2011]. Plast Surg Int. 2011;2011:158241.

- Bariya SH, Gohel MC, Mehta TA, et al. Microneedles: an emerging transdermal drug delivery system. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;64:11-29.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Izzo R, et al. The use of skin needling for the delivery of a eutectic mixture of local anesthetics. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149:581-585.

- De Vita V. How to choose among the multiple options to enhance the penetration of topically applied methyl aminolevulinate prior to photodynamic therapy [published online February 22, 2018]. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.02.014.

- Fernandes D. Minimally invasive percutaneous collagen induction. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005;17:51-63.

- Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring—a quantitative global scarring grading system. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2006;5:48-52.

- Majid I. Microneedling therapy in atrophic facial scars: an objective assessment. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009;2:26-30.

- Dogra S, Yadav S, Sarangal R. Microneedling for acne scars in Asian skin type: an effective low cost treatment modality. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014;13:180-187.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Monfrecola A, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction: an effective and safe treatment for post-acne scarring in different skin phototypes. J Dermatol Treat. 2014;25:147-152.

- Hashim PW, Levy Z, Cohen JL, et al. Microneedling therapy with and without platelet-rich plasma. Cutis. 2017;99:239-242.

- Wang HL, Avila G. Platelet rich plasma: myth or reality? Eur J Dent. 2007;1:192-194.

- Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:489-496.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Pastore F, et al. Combined use of skin needling and platelet-rich plasma in acne scarring treatment. Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;24:177-183.

- Chawla S. Split face comparative study of microneedling with PRP versus microneedling with vitamin C in treating atrophic post acne scars. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:209-212.

- Asif M, Kanodia S, Singh K. Combined autologous platelet-rich plasma with microneedling verses microneedling with distilled water in the treatment of atrophic acne scars: a concurrent split-face study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15:434-443.

- Ibrahim MK, Ibrahim SM, Salem AM. Skin microneedling plus platelet-rich plasma versus skin microneedling alone in the treatment of atrophic post acne scars: a split face comparative study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:281-286.

- Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring: a qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1458-1466.

- You H, Kim D, Yoon E, et al. Comparison of four different lasers for acne scars: resurfacing and fractional lasers. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:E87-E95.

- Osman MA, Shokeir HA, Fawzy MM. Fractional erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser versus microneedling in treatment of atrophic acne scars: a randomized split-face clinical study. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(suppl 1):S47-S56.

- Lee JW, Kim BJ, Kim MN, et al. The efficacy of autologous platelet rich plasma combined with ablative carbon dioxide fractional resurfacing for acne scars: a simultaneous split-face trial. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:931-938.

- Gawdat HI, Hegazy RA, Fawzy MM, et al. Autologous platelet rich plasma: topical versus intradermal after fractional ablative carbon dioxide laser treatment of atrophic acne scars. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:152-161.

- Abdel Aal AM, Ibrahim IM, Sami NA, et al. Evaluation of autologous platelet rich plasma plus ablative carbon dioxide fractional laser in the treatment of acne scars. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:106-113.

- Min S, Yoon JY, Park SY, et al. Combination of platelet rich plasma in fractional carbon dioxide laser treatment increased clinical efficacy of for acne scar by enhancement of collagen production and modulation of laser-induced inflammation. Lasers Surg Med. 2018;50:302-310.

- Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Assoian RK, et al. Transforming growth factor type beta: rapid induction of fibrosis and angiogenesis in vivo and stimulation of collagen formation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4167-4171.

- Schmidt EV. The role of c-myc in cellular growth control. Oncogene. 1999;18:2988-2996.

- Varga J, Rosenbloom J, Jimenez SA. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF beta) causes a persistent increase in steady-state amounts of type I and type III collagen and fibronectin mRNAs in normal human dermal fibroblasts. Biochem J. 1987;247:597-604.

- Chen J, Somanath PR, Razorenova O, et al. Akt1 regulates pathological angiogenesis, vascular maturation and permeability in vivo. Nat Med. 2005;11:1188-1196.

- Repertinger SK, Campagnaro E, Fuhrman J, et al. EGFR enhances early healing after cutaneous incisional wounding. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:982-989.

- Landau M. Chemical peels. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:200-208.

- Drake LA, Dinehart SM, Goltz RW, et al. Guidelines of care for chemical peeling. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:497-503.

- Meaike JD, Agrawal N, Chang D, et al. Noninvasive facial rejuvenation. part 3: physician-directed-lasers, chemical peels, and other noninvasive modalities. Semin Plast Surg. 2016;30:143-150.

- Leheta TM, Abdel Hay RM, El Garem YF. Deep peeling using phenol versus percutaneous collagen induction combined with trichloroacetic acid 20% in atrophic post-acne scars; a randomized controlled trial.J Dermatol Treat. 2014;25:130-136.

- El-Domyati M, Abdel-Wahab H, Hossam A. Microneedling combined with platelet-rich plasma or trichloroacetic acid peeling for management of acne scarring: a split-face clinical and histologic comparison.J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:73-83.

- Hession MT, Graber EM. Atrophic acne scarring: a review of treatment options. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:50-58.

- Dayan SH, Bassichis BA. Facial dermal fillers: selection of appropriate products and techniques. Aesthet Surg J. 2008;28:335-347.

- Munavalli GS, Smith S, Maslowski JM, et al. Successful treatment of depressed, distensible acne scars using autologous fibroblasts: a multi-site, prospective, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1226-1236.

- White GM. Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2, pt 3):S34-S37.

- Yazici K, Baz K, Yazici AE, et al. Disease-specific quality of life is associated with anxiety and depression in patients with acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:435-439.

- Orentreich DS, Orentreich N. Subcutaneous incisionless (subcision) surgery for the correction of depressed scars and wrinkles. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:543-549.

- Fabbrocini G, De Padova M, De Vita V, et al. Periorbital wrinkles treatment using collagen induction therapy. Surg Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;1:106-111.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Pastore F, et al. Collagen induction therapy for the treatment of upper lip wrinkles. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23:144-152.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Di Costanzo L, et al. Skin needling in the treatment of the aging neck. Skinmed. 2011;9:347-351.

- El-Domyati M, Barakat M, Awad S, et al. Microneedling therapy for atrophic acne scars: an objective evaluation. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-42.

- Fabbrocini G, Fardella N, Monfrecola A, et al. Acne scarring treatment using skin needling. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:874-879.

- Alam M, Han S, Pongprutthipan M, et al. Efficacy of a needling device for the treatment of acne scars: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:844-849.

- Dhurat R, Sukesh M, Avhad G, et al. A randomized evaluator blinded study of effect of microneedling in androgenetic alopecia: a pilot study. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:6-11.

- Dhurat R, Mathapati S. Response to microneedling treatment in men with androgenetic alopecia who failed to respond to conventional therapy. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:260-263.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Fardella N, et al. Skin needling to enhance depigmenting serum penetration in the treatment of melasma [published online April 7, 2011]. Plast Surg Int. 2011;2011:158241.

- Bariya SH, Gohel MC, Mehta TA, et al. Microneedles: an emerging transdermal drug delivery system. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;64:11-29.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Izzo R, et al. The use of skin needling for the delivery of a eutectic mixture of local anesthetics. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014;149:581-585.

- De Vita V. How to choose among the multiple options to enhance the penetration of topically applied methyl aminolevulinate prior to photodynamic therapy [published online February 22, 2018]. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2018.02.014.

- Fernandes D. Minimally invasive percutaneous collagen induction. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2005;17:51-63.

- Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring—a quantitative global scarring grading system. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2006;5:48-52.

- Majid I. Microneedling therapy in atrophic facial scars: an objective assessment. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2009;2:26-30.

- Dogra S, Yadav S, Sarangal R. Microneedling for acne scars in Asian skin type: an effective low cost treatment modality. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2014;13:180-187.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Monfrecola A, et al. Percutaneous collagen induction: an effective and safe treatment for post-acne scarring in different skin phototypes. J Dermatol Treat. 2014;25:147-152.

- Hashim PW, Levy Z, Cohen JL, et al. Microneedling therapy with and without platelet-rich plasma. Cutis. 2017;99:239-242.

- Wang HL, Avila G. Platelet rich plasma: myth or reality? Eur J Dent. 2007;1:192-194.

- Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma: evidence to support its use. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:489-496.

- Fabbrocini G, De Vita V, Pastore F, et al. Combined use of skin needling and platelet-rich plasma in acne scarring treatment. Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;24:177-183.

- Chawla S. Split face comparative study of microneedling with PRP versus microneedling with vitamin C in treating atrophic post acne scars. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:209-212.

- Asif M, Kanodia S, Singh K. Combined autologous platelet-rich plasma with microneedling verses microneedling with distilled water in the treatment of atrophic acne scars: a concurrent split-face study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15:434-443.

- Ibrahim MK, Ibrahim SM, Salem AM. Skin microneedling plus platelet-rich plasma versus skin microneedling alone in the treatment of atrophic post acne scars: a split face comparative study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:281-286.

- Goodman GJ, Baron JA. Postacne scarring: a qualitative global scarring grading system. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1458-1466.

- You H, Kim D, Yoon E, et al. Comparison of four different lasers for acne scars: resurfacing and fractional lasers. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:E87-E95.

- Osman MA, Shokeir HA, Fawzy MM. Fractional erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser versus microneedling in treatment of atrophic acne scars: a randomized split-face clinical study. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(suppl 1):S47-S56.

- Lee JW, Kim BJ, Kim MN, et al. The efficacy of autologous platelet rich plasma combined with ablative carbon dioxide fractional resurfacing for acne scars: a simultaneous split-face trial. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:931-938.

- Gawdat HI, Hegazy RA, Fawzy MM, et al. Autologous platelet rich plasma: topical versus intradermal after fractional ablative carbon dioxide laser treatment of atrophic acne scars. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:152-161.

- Abdel Aal AM, Ibrahim IM, Sami NA, et al. Evaluation of autologous platelet rich plasma plus ablative carbon dioxide fractional laser in the treatment of acne scars. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2018;20:106-113.

- Min S, Yoon JY, Park SY, et al. Combination of platelet rich plasma in fractional carbon dioxide laser treatment increased clinical efficacy of for acne scar by enhancement of collagen production and modulation of laser-induced inflammation. Lasers Surg Med. 2018;50:302-310.

- Roberts AB, Sporn MB, Assoian RK, et al. Transforming growth factor type beta: rapid induction of fibrosis and angiogenesis in vivo and stimulation of collagen formation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4167-4171.

- Schmidt EV. The role of c-myc in cellular growth control. Oncogene. 1999;18:2988-2996.

- Varga J, Rosenbloom J, Jimenez SA. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF beta) causes a persistent increase in steady-state amounts of type I and type III collagen and fibronectin mRNAs in normal human dermal fibroblasts. Biochem J. 1987;247:597-604.

- Chen J, Somanath PR, Razorenova O, et al. Akt1 regulates pathological angiogenesis, vascular maturation and permeability in vivo. Nat Med. 2005;11:1188-1196.

- Repertinger SK, Campagnaro E, Fuhrman J, et al. EGFR enhances early healing after cutaneous incisional wounding. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123:982-989.

- Landau M. Chemical peels. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:200-208.

- Drake LA, Dinehart SM, Goltz RW, et al. Guidelines of care for chemical peeling. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:497-503.

- Meaike JD, Agrawal N, Chang D, et al. Noninvasive facial rejuvenation. part 3: physician-directed-lasers, chemical peels, and other noninvasive modalities. Semin Plast Surg. 2016;30:143-150.