User login

Cutaneous Complications Associated With Intraosseous Access Placement

Intraosseous (IO) access can afford a lifesaving means of vascular access in emergency settings, as it allows for the administration of large volumes of fluids, blood products, and medications at high flow rates directly into the highly vascularized osseous medullary cavity.1 Fortunately, the complication rate with this resuscitative effort is low, with many reports demonstrating complication rates of less than 1%.2 The most commonly reported complications include fluid extravasation, osteomyelitis, traumatic bone fracture, and epiphyseal plate damage.1-3 Although compartment syndrome and skin necrosis have been reported,4,5 there is no comprehensive list of sequelae resulting from fluid extravasation in the literature, and there are no known studies examining the incidence and types of cutaneous complications. In this study, we sought to evaluate the dermatologic impacts of this procedure.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review approved by the institutional review board at a large metropolitan level I trauma center in the Midwestern United States spanning 18 consecutive months to identify all patients who underwent IO line placement, either en route to or upon arrival at the trauma center. The electronic medical records of 113 patients (age range, 10 days–94 years) were identified using either an automated natural language look-up program with keywords including intraosseous access and IO or a Current Procedural Terminology code 36680. Data including patient age, reason for IO insertion, anatomic location of the IO, and complications secondary to IO line placement were recorded.

Results

We identified an overall complication rate of 2.7% (3/113), with only 1 patient showing isolated cutaneous complications from IO line placement. The complications in the first 2 patients included compartment syndrome following IO line placement in the right tibia and needle breakage during IO line placement. The third patient, a 30-year-old heart transplant recipient, developed tense bullae on the left leg 5 days after a resuscitative effort required IO access through the bilateral tibiae. The patient had received vasopressors as well as 750 mL of normal saline through these access points. Two days after resuscitation, she developed an enlarg

At a scheduled 7-month dermatology follow-up, the wound bed appeared to be healing well with surrounding scarring with no residual bleeding or drainage (Figure 2) despite the patient reporting a protracted course of wound healing requiring debridement due to eschar formation and multiple follow-up appointments with the wound care service.

Comment

The most commonly reported complications with IO line placement result from fluid infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue secondary to catheter misplacement.1,3 Extravasated fluid may lead to tissue damage, compartment syndrome, and even tissue necrosis in some cases.1,4,5 Localized cellulitis and the formation of subcutaneous abscesses also have been reported, albeit rarely.3,5

In our retrospective cohort review, we identified an additional potential complication of IO line placement that has not been widely reported—development of large traumatic bullae. It is most likely that this patient’s IO catheter became dislodged, resulting in extravasation of fluids into the dermal and subcutaneous tissues.

Our findings support the previously noted complication rate of less than 1% following IO line placement, with an overall complication rate of 2.7% that included only 1 patient with a cutaneous complication.2 Given this low incidence, providers may not be used to recognizing such complications, leading to delayed or incorrect diagnosis of these entities. While there are certain conditions in which IO insertion is contraindicated, including severe bone diseases (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta, osteomyelitis), overlying cellulitis, and bone fracture, these conditions are rare and can be avoided in most cases by use of an alternative site for needle insertion.2 Due to the widespread utility of this tool and its few contraindications, its use in hospitalized patients is rapidly increasing, necessitating a need for quick recognition of potential complications.

From previous data on the incidence of traumatic blisters with underlying bone fractures, there are several identifiable risk factors that could be extended to patients at high risk for developing cutaneous IO complications secondary to the trauma associated with needle insertion,6 including wound-healing impairments in patients with fragile lymphatics, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, or collagen vascular diseases (eg, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome). Patients with these conditions should be closely monitored for the development of bullae.6 While the patient we highlighted in our study did not have a history of such conditions, her history of cardiac disease, recent resuscitation attempts, and immunosuppression certainly could have contributed to suboptimal tissue agility and repair after IO line placement.

Conclusion

Intraosseous access is a safe, effective, and reliable option for vascular access in both pediatric and adult populations that is widely used in both prehospital (ie, paramedic administered) and hospital settings, including intensive care units, emergency departments, and any acute situation where rapid vascular access is necessary. This retrospective chart review examining the incidence and types of cutaneous complications associated with IO line placement at a level I trauma center revealed a total complication rate similar to those reported in previous studies and also highlighted a unique postprocedural cutaneous finding of traumatic bullae. Although no unified management recommendations currently exist, providers should consider this complication in the differential for hospitalized patients with large, atypical, asymmetric bullae in the absence of an alternative explanation for such skin findings.

- Day MW. Intraosseous devices for intravascular access in adult trauma patients. Crit Care Nurse. 2011;31:76-90. doi:10.4037/ccn2011615

- Petitpas F, Guenezan J, Vendeuvre T, et al. Use of intra-osseous access in adults: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2016;20:102. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1277-6

- Desforges JF, Fiser DH. Intraosseous infusion. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1579-1581. doi:10.1056/NEJM199005313222206

- Simmons CM, Johnson NE, Perkin RM, et al. Intraosseous extravasation complication reports. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:363-366. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(94)70053-2

- Paxton JH. Intraosseous vascular access: a review. Trauma. 2012;14:195-232. doi:10.1177/1460408611430175

- Uebbing CM, Walsh M, Miller JB, et al. Fracture blisters. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:131-133. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(09)80152-7

Intraosseous (IO) access can afford a lifesaving means of vascular access in emergency settings, as it allows for the administration of large volumes of fluids, blood products, and medications at high flow rates directly into the highly vascularized osseous medullary cavity.1 Fortunately, the complication rate with this resuscitative effort is low, with many reports demonstrating complication rates of less than 1%.2 The most commonly reported complications include fluid extravasation, osteomyelitis, traumatic bone fracture, and epiphyseal plate damage.1-3 Although compartment syndrome and skin necrosis have been reported,4,5 there is no comprehensive list of sequelae resulting from fluid extravasation in the literature, and there are no known studies examining the incidence and types of cutaneous complications. In this study, we sought to evaluate the dermatologic impacts of this procedure.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review approved by the institutional review board at a large metropolitan level I trauma center in the Midwestern United States spanning 18 consecutive months to identify all patients who underwent IO line placement, either en route to or upon arrival at the trauma center. The electronic medical records of 113 patients (age range, 10 days–94 years) were identified using either an automated natural language look-up program with keywords including intraosseous access and IO or a Current Procedural Terminology code 36680. Data including patient age, reason for IO insertion, anatomic location of the IO, and complications secondary to IO line placement were recorded.

Results

We identified an overall complication rate of 2.7% (3/113), with only 1 patient showing isolated cutaneous complications from IO line placement. The complications in the first 2 patients included compartment syndrome following IO line placement in the right tibia and needle breakage during IO line placement. The third patient, a 30-year-old heart transplant recipient, developed tense bullae on the left leg 5 days after a resuscitative effort required IO access through the bilateral tibiae. The patient had received vasopressors as well as 750 mL of normal saline through these access points. Two days after resuscitation, she developed an enlarg

At a scheduled 7-month dermatology follow-up, the wound bed appeared to be healing well with surrounding scarring with no residual bleeding or drainage (Figure 2) despite the patient reporting a protracted course of wound healing requiring debridement due to eschar formation and multiple follow-up appointments with the wound care service.

Comment

The most commonly reported complications with IO line placement result from fluid infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue secondary to catheter misplacement.1,3 Extravasated fluid may lead to tissue damage, compartment syndrome, and even tissue necrosis in some cases.1,4,5 Localized cellulitis and the formation of subcutaneous abscesses also have been reported, albeit rarely.3,5

In our retrospective cohort review, we identified an additional potential complication of IO line placement that has not been widely reported—development of large traumatic bullae. It is most likely that this patient’s IO catheter became dislodged, resulting in extravasation of fluids into the dermal and subcutaneous tissues.

Our findings support the previously noted complication rate of less than 1% following IO line placement, with an overall complication rate of 2.7% that included only 1 patient with a cutaneous complication.2 Given this low incidence, providers may not be used to recognizing such complications, leading to delayed or incorrect diagnosis of these entities. While there are certain conditions in which IO insertion is contraindicated, including severe bone diseases (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta, osteomyelitis), overlying cellulitis, and bone fracture, these conditions are rare and can be avoided in most cases by use of an alternative site for needle insertion.2 Due to the widespread utility of this tool and its few contraindications, its use in hospitalized patients is rapidly increasing, necessitating a need for quick recognition of potential complications.

From previous data on the incidence of traumatic blisters with underlying bone fractures, there are several identifiable risk factors that could be extended to patients at high risk for developing cutaneous IO complications secondary to the trauma associated with needle insertion,6 including wound-healing impairments in patients with fragile lymphatics, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, or collagen vascular diseases (eg, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome). Patients with these conditions should be closely monitored for the development of bullae.6 While the patient we highlighted in our study did not have a history of such conditions, her history of cardiac disease, recent resuscitation attempts, and immunosuppression certainly could have contributed to suboptimal tissue agility and repair after IO line placement.

Conclusion

Intraosseous access is a safe, effective, and reliable option for vascular access in both pediatric and adult populations that is widely used in both prehospital (ie, paramedic administered) and hospital settings, including intensive care units, emergency departments, and any acute situation where rapid vascular access is necessary. This retrospective chart review examining the incidence and types of cutaneous complications associated with IO line placement at a level I trauma center revealed a total complication rate similar to those reported in previous studies and also highlighted a unique postprocedural cutaneous finding of traumatic bullae. Although no unified management recommendations currently exist, providers should consider this complication in the differential for hospitalized patients with large, atypical, asymmetric bullae in the absence of an alternative explanation for such skin findings.

Intraosseous (IO) access can afford a lifesaving means of vascular access in emergency settings, as it allows for the administration of large volumes of fluids, blood products, and medications at high flow rates directly into the highly vascularized osseous medullary cavity.1 Fortunately, the complication rate with this resuscitative effort is low, with many reports demonstrating complication rates of less than 1%.2 The most commonly reported complications include fluid extravasation, osteomyelitis, traumatic bone fracture, and epiphyseal plate damage.1-3 Although compartment syndrome and skin necrosis have been reported,4,5 there is no comprehensive list of sequelae resulting from fluid extravasation in the literature, and there are no known studies examining the incidence and types of cutaneous complications. In this study, we sought to evaluate the dermatologic impacts of this procedure.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review approved by the institutional review board at a large metropolitan level I trauma center in the Midwestern United States spanning 18 consecutive months to identify all patients who underwent IO line placement, either en route to or upon arrival at the trauma center. The electronic medical records of 113 patients (age range, 10 days–94 years) were identified using either an automated natural language look-up program with keywords including intraosseous access and IO or a Current Procedural Terminology code 36680. Data including patient age, reason for IO insertion, anatomic location of the IO, and complications secondary to IO line placement were recorded.

Results

We identified an overall complication rate of 2.7% (3/113), with only 1 patient showing isolated cutaneous complications from IO line placement. The complications in the first 2 patients included compartment syndrome following IO line placement in the right tibia and needle breakage during IO line placement. The third patient, a 30-year-old heart transplant recipient, developed tense bullae on the left leg 5 days after a resuscitative effort required IO access through the bilateral tibiae. The patient had received vasopressors as well as 750 mL of normal saline through these access points. Two days after resuscitation, she developed an enlarg

At a scheduled 7-month dermatology follow-up, the wound bed appeared to be healing well with surrounding scarring with no residual bleeding or drainage (Figure 2) despite the patient reporting a protracted course of wound healing requiring debridement due to eschar formation and multiple follow-up appointments with the wound care service.

Comment

The most commonly reported complications with IO line placement result from fluid infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue secondary to catheter misplacement.1,3 Extravasated fluid may lead to tissue damage, compartment syndrome, and even tissue necrosis in some cases.1,4,5 Localized cellulitis and the formation of subcutaneous abscesses also have been reported, albeit rarely.3,5

In our retrospective cohort review, we identified an additional potential complication of IO line placement that has not been widely reported—development of large traumatic bullae. It is most likely that this patient’s IO catheter became dislodged, resulting in extravasation of fluids into the dermal and subcutaneous tissues.

Our findings support the previously noted complication rate of less than 1% following IO line placement, with an overall complication rate of 2.7% that included only 1 patient with a cutaneous complication.2 Given this low incidence, providers may not be used to recognizing such complications, leading to delayed or incorrect diagnosis of these entities. While there are certain conditions in which IO insertion is contraindicated, including severe bone diseases (eg, osteogenesis imperfecta, osteomyelitis), overlying cellulitis, and bone fracture, these conditions are rare and can be avoided in most cases by use of an alternative site for needle insertion.2 Due to the widespread utility of this tool and its few contraindications, its use in hospitalized patients is rapidly increasing, necessitating a need for quick recognition of potential complications.

From previous data on the incidence of traumatic blisters with underlying bone fractures, there are several identifiable risk factors that could be extended to patients at high risk for developing cutaneous IO complications secondary to the trauma associated with needle insertion,6 including wound-healing impairments in patients with fragile lymphatics, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, or collagen vascular diseases (eg, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome). Patients with these conditions should be closely monitored for the development of bullae.6 While the patient we highlighted in our study did not have a history of such conditions, her history of cardiac disease, recent resuscitation attempts, and immunosuppression certainly could have contributed to suboptimal tissue agility and repair after IO line placement.

Conclusion

Intraosseous access is a safe, effective, and reliable option for vascular access in both pediatric and adult populations that is widely used in both prehospital (ie, paramedic administered) and hospital settings, including intensive care units, emergency departments, and any acute situation where rapid vascular access is necessary. This retrospective chart review examining the incidence and types of cutaneous complications associated with IO line placement at a level I trauma center revealed a total complication rate similar to those reported in previous studies and also highlighted a unique postprocedural cutaneous finding of traumatic bullae. Although no unified management recommendations currently exist, providers should consider this complication in the differential for hospitalized patients with large, atypical, asymmetric bullae in the absence of an alternative explanation for such skin findings.

- Day MW. Intraosseous devices for intravascular access in adult trauma patients. Crit Care Nurse. 2011;31:76-90. doi:10.4037/ccn2011615

- Petitpas F, Guenezan J, Vendeuvre T, et al. Use of intra-osseous access in adults: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2016;20:102. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1277-6

- Desforges JF, Fiser DH. Intraosseous infusion. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1579-1581. doi:10.1056/NEJM199005313222206

- Simmons CM, Johnson NE, Perkin RM, et al. Intraosseous extravasation complication reports. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:363-366. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(94)70053-2

- Paxton JH. Intraosseous vascular access: a review. Trauma. 2012;14:195-232. doi:10.1177/1460408611430175

- Uebbing CM, Walsh M, Miller JB, et al. Fracture blisters. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:131-133. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(09)80152-7

- Day MW. Intraosseous devices for intravascular access in adult trauma patients. Crit Care Nurse. 2011;31:76-90. doi:10.4037/ccn2011615

- Petitpas F, Guenezan J, Vendeuvre T, et al. Use of intra-osseous access in adults: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2016;20:102. doi:10.1186/s13054-016-1277-6

- Desforges JF, Fiser DH. Intraosseous infusion. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1579-1581. doi:10.1056/NEJM199005313222206

- Simmons CM, Johnson NE, Perkin RM, et al. Intraosseous extravasation complication reports. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:363-366. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(94)70053-2

- Paxton JH. Intraosseous vascular access: a review. Trauma. 2012;14:195-232. doi:10.1177/1460408611430175

- Uebbing CM, Walsh M, Miller JB, et al. Fracture blisters. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:131-133. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(09)80152-7

Practice Points

- Intraosseous (IO) access provides rapid vascular access for the delivery of fluids, drugs, and blood products in emergent situations.

- Bullae are potential complications from IO line placement.

Perianal Extramammary Paget Disease Treated With Topical Imiquimod and Oral Cimetidine

Case Report

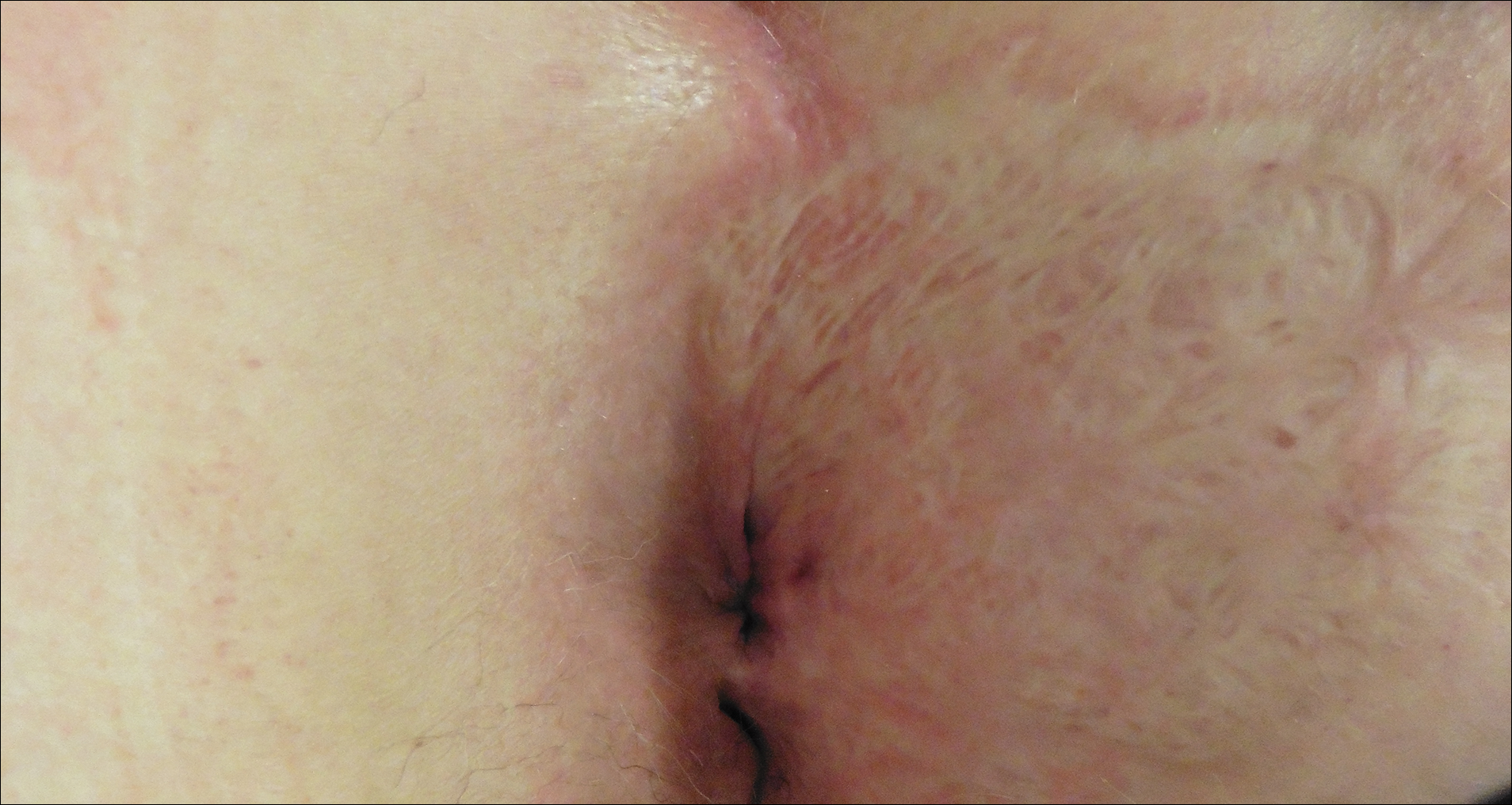

A 56-year-old woman with well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease initially presented with itching and a rash in the perianal region of 1 year’s duration. She had been treated intermittently by her primary care physician over the past year for presumed hemorrhoids and a perianal fungal infection without improvement. Physical examination at the time of intitial presentation revealed a single, well-demarcated, scaly, pink plaque on the perianal area on the right buttock extending toward the anal canal (Figure 1).

Four years later, the patient returned with new symptoms of bleeding when wiping the perianal region, pruritus, and fecal urgency of 3 to 4 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed scaly patches on the anus that were suspicious for recurrence of EMPD. Biopsies from the anal margin and anal canal confirmed recurrent EMPD involving the anal canal. Repeat evaluation for internal malignancy was negative.

Given the involvement of the anal canal, repeat wide local excision would have required anal resection and would therefore have been functionally impairing. The patient refused further surgical intervention as well as radiotherapy. Rather, a novel 16-week immunomodulatory regimen involving imiquimod cream 5% cream and low-dose oral cimetidine was started. To address the anal involvement, the patient was instructed to lubricate glycerin suppositories with the imiquimod cream and insert intra-anally once weekly. Dosing was adjusted based on the patient’s inflammatory response and tolerability, as she did initially report some flulike symptoms with the first few weeks of treatment. For most of the 16-week course, she applied 250 mg of imiquimod cream 5% to the perianal area 3 times weekly and 250 mg into the anal canal once weekly. Oral cimetidine initially was dosed at 800 mg twice daily as tolerated, but due to stomach irritation, the patient self-reduced her intake to 800 mg 3 times weekly.

To determine treatment response, scouting biopsies of the anal margin and anal canal were obtained 4 weeks after treatment cessation and demonstrated no evidence of residual disease. The patient resumed topical imiquimod applied once weekly into the anal canal and around the anus for a planned prolonged course of at least 1 year. To reduce the risk of recurrence, the patient continued taking oral cimetidine 800 mg 3 times weekly. Recommended follow-up included annual anoscopy or colonoscopy, serum carcinoembryonic antigen evaluation, and regular clinical monitoring by the dermatology and colorectal surgery teams.

Six months after completing the combination therapy, she was seen by the dermatology department and remained clinically free of disease (Figure 4). Anoscopy examination by the colorectal surgery department 4 months later showed no clinical evidence of malignancy.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial adenocarcinoma with a predilection for white females and an average age of onset of 50 to 80 years.1-3 The vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and perineum are the most commonly affected sites.1-3 Clinically, EMPD presents as a chronic, well-demarcated, scaly, and often expanding plaque. The incidence of EMPD is unknown, as there are only a few hundred cases reported in the literature.2

Extramammary Paget disease can occur primarily, arising in the epidermis at the sweat-gland level or from primitive epidermal basal cells, or secondarily due to pagetoid spread of malignant cells from an adjacent or contiguous underlying adnexal adenocarcinoma or visceral malignancy.2 While primary EMPD is not associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, it may become invasive, infiltrate the dermis, or metastasize via the lymphatics.2 Secondary EMPD is associated with underlying malignancy most often originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts.1,2

Currently, treatment of primary EMPD typically is surgical with wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1,2 However, margins often are positive, and the local recurrence rate is high (ie, 33%–66%).2,3 There are a variety of other therapies that have been reported in the literature, including radiation, topical chemotherapeutics (eg, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin), photodynamic therapy, and CO2 laser ablation.1,3 To our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare surgery with other treatment options for EMPD.

Despite recurrence of EMPD with involvement of the anal canal, our patient refused further surgical intervention, as it would have required anal resection and radiotherapy due to the potentially negative impact on sphincter function. While investigating minimally invasive treatment options, we found several citations in the literature highlighting positive response with imiquimod cream 5% in patients with vulvar and periscrotal EMPD.4,5 A large, systematic review that analyzed 63 cases of vulvar EMPD—nearly half of which were recurrences of a prior malignancy—reported a response rate of 52% to 80% following treatment with imiquimod.5 Almost 70% of patients achieved complete clearance while applying imiquimod 3 to 4 times weekly for a median of 4 months; however, little has been written about the effectiveness of topical imiquimod in EMPD. Knight et al6 reported the case of a 40-year-old woman with perianal EMPD who was treated with imiquimod 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, the patient was completely clear of disease both clinically and histologically on random biopsies of the perianal skin; however, the EMPD later recurred with lymph node metastasis 18 months after stopping treatment.6

Given the growing evidence demonstrating disease control of EMPD with topical imiquimod, we elected to utilize this agent in combination with oral cimetidine in our patient. Cimetidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to have antineoplastic properties in a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies for a number of different malignancies.7 Four distinct mechanisms of action have been shown. Cimetidine, which blocks the histamine pathway, has been shown to have a direct antiproliferative action on cancer cells.7 Histamine has been associated with increased regulatory T-cell activity, decreased antigen-presenting activity of dendritic cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity, which create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the setting of cancer. By blocking histamine and thus reversing this immunosuppressive environment, cimetidine demonstrates immunomodulatory effects.7 Cimetidine also has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on cancer cell adhesion to endothelial cells, which is noted to be independent of histamine-blocking activity.7 Finally, an antiangiogenic action is attributed to blocking of the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor that is normally induced by histamine.7

Cimetidine’s antineoplastic properties, specifically in the setting of colorectal cancer,8 were particularly compelling given our patient’s EMPD involvement of the anal canal. The most impressive clinical trial data showed a dramatically increased survival rate for colorectal cancer patients treated with oral cimetidine (800 mg once daily) and oral 5-fluorouracil (200 mg once daily) for 1 year following curative resection. The cimetidine-treated group had a 10-year survival rate of 84.6% versus 49.8% for the 5-fluorouracil–only group.8

Conclusion

We present this case of recurrent perianal and anal EMPD treated successfully with imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine to highlight a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with EMPD.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Vergati M, Filingeri V, Palmieri G, et al. Perianal Paget’s disease: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4461-4465.

- Liau MM, Yang SS, Tan KB, et al. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease: a 10 year retrospective analysis in an Asian tertiary centre. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:459-462.

- Machida H, Moeini A, Roman LD, et al. Effects of imiquimod on vulvar Paget’s disease: a systematic review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:165-171.

- Knight SR, Proby C, Ziyaie D, et al. Extramammary Paget disease of the perianal region: the potential role of imiquimod in achieving disease control. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:1-3.

- Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)—cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:161-167.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease initially presented with itching and a rash in the perianal region of 1 year’s duration. She had been treated intermittently by her primary care physician over the past year for presumed hemorrhoids and a perianal fungal infection without improvement. Physical examination at the time of intitial presentation revealed a single, well-demarcated, scaly, pink plaque on the perianal area on the right buttock extending toward the anal canal (Figure 1).

Four years later, the patient returned with new symptoms of bleeding when wiping the perianal region, pruritus, and fecal urgency of 3 to 4 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed scaly patches on the anus that were suspicious for recurrence of EMPD. Biopsies from the anal margin and anal canal confirmed recurrent EMPD involving the anal canal. Repeat evaluation for internal malignancy was negative.

Given the involvement of the anal canal, repeat wide local excision would have required anal resection and would therefore have been functionally impairing. The patient refused further surgical intervention as well as radiotherapy. Rather, a novel 16-week immunomodulatory regimen involving imiquimod cream 5% cream and low-dose oral cimetidine was started. To address the anal involvement, the patient was instructed to lubricate glycerin suppositories with the imiquimod cream and insert intra-anally once weekly. Dosing was adjusted based on the patient’s inflammatory response and tolerability, as she did initially report some flulike symptoms with the first few weeks of treatment. For most of the 16-week course, she applied 250 mg of imiquimod cream 5% to the perianal area 3 times weekly and 250 mg into the anal canal once weekly. Oral cimetidine initially was dosed at 800 mg twice daily as tolerated, but due to stomach irritation, the patient self-reduced her intake to 800 mg 3 times weekly.

To determine treatment response, scouting biopsies of the anal margin and anal canal were obtained 4 weeks after treatment cessation and demonstrated no evidence of residual disease. The patient resumed topical imiquimod applied once weekly into the anal canal and around the anus for a planned prolonged course of at least 1 year. To reduce the risk of recurrence, the patient continued taking oral cimetidine 800 mg 3 times weekly. Recommended follow-up included annual anoscopy or colonoscopy, serum carcinoembryonic antigen evaluation, and regular clinical monitoring by the dermatology and colorectal surgery teams.

Six months after completing the combination therapy, she was seen by the dermatology department and remained clinically free of disease (Figure 4). Anoscopy examination by the colorectal surgery department 4 months later showed no clinical evidence of malignancy.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial adenocarcinoma with a predilection for white females and an average age of onset of 50 to 80 years.1-3 The vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and perineum are the most commonly affected sites.1-3 Clinically, EMPD presents as a chronic, well-demarcated, scaly, and often expanding plaque. The incidence of EMPD is unknown, as there are only a few hundred cases reported in the literature.2

Extramammary Paget disease can occur primarily, arising in the epidermis at the sweat-gland level or from primitive epidermal basal cells, or secondarily due to pagetoid spread of malignant cells from an adjacent or contiguous underlying adnexal adenocarcinoma or visceral malignancy.2 While primary EMPD is not associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, it may become invasive, infiltrate the dermis, or metastasize via the lymphatics.2 Secondary EMPD is associated with underlying malignancy most often originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts.1,2

Currently, treatment of primary EMPD typically is surgical with wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1,2 However, margins often are positive, and the local recurrence rate is high (ie, 33%–66%).2,3 There are a variety of other therapies that have been reported in the literature, including radiation, topical chemotherapeutics (eg, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin), photodynamic therapy, and CO2 laser ablation.1,3 To our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare surgery with other treatment options for EMPD.

Despite recurrence of EMPD with involvement of the anal canal, our patient refused further surgical intervention, as it would have required anal resection and radiotherapy due to the potentially negative impact on sphincter function. While investigating minimally invasive treatment options, we found several citations in the literature highlighting positive response with imiquimod cream 5% in patients with vulvar and periscrotal EMPD.4,5 A large, systematic review that analyzed 63 cases of vulvar EMPD—nearly half of which were recurrences of a prior malignancy—reported a response rate of 52% to 80% following treatment with imiquimod.5 Almost 70% of patients achieved complete clearance while applying imiquimod 3 to 4 times weekly for a median of 4 months; however, little has been written about the effectiveness of topical imiquimod in EMPD. Knight et al6 reported the case of a 40-year-old woman with perianal EMPD who was treated with imiquimod 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, the patient was completely clear of disease both clinically and histologically on random biopsies of the perianal skin; however, the EMPD later recurred with lymph node metastasis 18 months after stopping treatment.6

Given the growing evidence demonstrating disease control of EMPD with topical imiquimod, we elected to utilize this agent in combination with oral cimetidine in our patient. Cimetidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to have antineoplastic properties in a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies for a number of different malignancies.7 Four distinct mechanisms of action have been shown. Cimetidine, which blocks the histamine pathway, has been shown to have a direct antiproliferative action on cancer cells.7 Histamine has been associated with increased regulatory T-cell activity, decreased antigen-presenting activity of dendritic cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity, which create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the setting of cancer. By blocking histamine and thus reversing this immunosuppressive environment, cimetidine demonstrates immunomodulatory effects.7 Cimetidine also has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on cancer cell adhesion to endothelial cells, which is noted to be independent of histamine-blocking activity.7 Finally, an antiangiogenic action is attributed to blocking of the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor that is normally induced by histamine.7

Cimetidine’s antineoplastic properties, specifically in the setting of colorectal cancer,8 were particularly compelling given our patient’s EMPD involvement of the anal canal. The most impressive clinical trial data showed a dramatically increased survival rate for colorectal cancer patients treated with oral cimetidine (800 mg once daily) and oral 5-fluorouracil (200 mg once daily) for 1 year following curative resection. The cimetidine-treated group had a 10-year survival rate of 84.6% versus 49.8% for the 5-fluorouracil–only group.8

Conclusion

We present this case of recurrent perianal and anal EMPD treated successfully with imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine to highlight a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with EMPD.

Case Report

A 56-year-old woman with well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease initially presented with itching and a rash in the perianal region of 1 year’s duration. She had been treated intermittently by her primary care physician over the past year for presumed hemorrhoids and a perianal fungal infection without improvement. Physical examination at the time of intitial presentation revealed a single, well-demarcated, scaly, pink plaque on the perianal area on the right buttock extending toward the anal canal (Figure 1).

Four years later, the patient returned with new symptoms of bleeding when wiping the perianal region, pruritus, and fecal urgency of 3 to 4 months’ duration. Physical examination revealed scaly patches on the anus that were suspicious for recurrence of EMPD. Biopsies from the anal margin and anal canal confirmed recurrent EMPD involving the anal canal. Repeat evaluation for internal malignancy was negative.

Given the involvement of the anal canal, repeat wide local excision would have required anal resection and would therefore have been functionally impairing. The patient refused further surgical intervention as well as radiotherapy. Rather, a novel 16-week immunomodulatory regimen involving imiquimod cream 5% cream and low-dose oral cimetidine was started. To address the anal involvement, the patient was instructed to lubricate glycerin suppositories with the imiquimod cream and insert intra-anally once weekly. Dosing was adjusted based on the patient’s inflammatory response and tolerability, as she did initially report some flulike symptoms with the first few weeks of treatment. For most of the 16-week course, she applied 250 mg of imiquimod cream 5% to the perianal area 3 times weekly and 250 mg into the anal canal once weekly. Oral cimetidine initially was dosed at 800 mg twice daily as tolerated, but due to stomach irritation, the patient self-reduced her intake to 800 mg 3 times weekly.

To determine treatment response, scouting biopsies of the anal margin and anal canal were obtained 4 weeks after treatment cessation and demonstrated no evidence of residual disease. The patient resumed topical imiquimod applied once weekly into the anal canal and around the anus for a planned prolonged course of at least 1 year. To reduce the risk of recurrence, the patient continued taking oral cimetidine 800 mg 3 times weekly. Recommended follow-up included annual anoscopy or colonoscopy, serum carcinoembryonic antigen evaluation, and regular clinical monitoring by the dermatology and colorectal surgery teams.

Six months after completing the combination therapy, she was seen by the dermatology department and remained clinically free of disease (Figure 4). Anoscopy examination by the colorectal surgery department 4 months later showed no clinical evidence of malignancy.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a rare intraepithelial adenocarcinoma with a predilection for white females and an average age of onset of 50 to 80 years.1-3 The vulva, perianal region, scrotum, penis, and perineum are the most commonly affected sites.1-3 Clinically, EMPD presents as a chronic, well-demarcated, scaly, and often expanding plaque. The incidence of EMPD is unknown, as there are only a few hundred cases reported in the literature.2

Extramammary Paget disease can occur primarily, arising in the epidermis at the sweat-gland level or from primitive epidermal basal cells, or secondarily due to pagetoid spread of malignant cells from an adjacent or contiguous underlying adnexal adenocarcinoma or visceral malignancy.2 While primary EMPD is not associated with an underlying adenocarcinoma, it may become invasive, infiltrate the dermis, or metastasize via the lymphatics.2 Secondary EMPD is associated with underlying malignancy most often originating in the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts.1,2

Currently, treatment of primary EMPD typically is surgical with wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.1,2 However, margins often are positive, and the local recurrence rate is high (ie, 33%–66%).2,3 There are a variety of other therapies that have been reported in the literature, including radiation, topical chemotherapeutics (eg, imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin), photodynamic therapy, and CO2 laser ablation.1,3 To our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials that compare surgery with other treatment options for EMPD.

Despite recurrence of EMPD with involvement of the anal canal, our patient refused further surgical intervention, as it would have required anal resection and radiotherapy due to the potentially negative impact on sphincter function. While investigating minimally invasive treatment options, we found several citations in the literature highlighting positive response with imiquimod cream 5% in patients with vulvar and periscrotal EMPD.4,5 A large, systematic review that analyzed 63 cases of vulvar EMPD—nearly half of which were recurrences of a prior malignancy—reported a response rate of 52% to 80% following treatment with imiquimod.5 Almost 70% of patients achieved complete clearance while applying imiquimod 3 to 4 times weekly for a median of 4 months; however, little has been written about the effectiveness of topical imiquimod in EMPD. Knight et al6 reported the case of a 40-year-old woman with perianal EMPD who was treated with imiquimod 3 times weekly for 16 weeks. At the end of treatment, the patient was completely clear of disease both clinically and histologically on random biopsies of the perianal skin; however, the EMPD later recurred with lymph node metastasis 18 months after stopping treatment.6

Given the growing evidence demonstrating disease control of EMPD with topical imiquimod, we elected to utilize this agent in combination with oral cimetidine in our patient. Cimetidine, an H2 receptor antagonist, has been shown to have antineoplastic properties in a broad range of preclinical and clinical studies for a number of different malignancies.7 Four distinct mechanisms of action have been shown. Cimetidine, which blocks the histamine pathway, has been shown to have a direct antiproliferative action on cancer cells.7 Histamine has been associated with increased regulatory T-cell activity, decreased antigen-presenting activity of dendritic cells, reduced natural killer cell activity, and increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity, which create an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in the setting of cancer. By blocking histamine and thus reversing this immunosuppressive environment, cimetidine demonstrates immunomodulatory effects.7 Cimetidine also has demonstrated an inhibitory effect on cancer cell adhesion to endothelial cells, which is noted to be independent of histamine-blocking activity.7 Finally, an antiangiogenic action is attributed to blocking of the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor that is normally induced by histamine.7

Cimetidine’s antineoplastic properties, specifically in the setting of colorectal cancer,8 were particularly compelling given our patient’s EMPD involvement of the anal canal. The most impressive clinical trial data showed a dramatically increased survival rate for colorectal cancer patients treated with oral cimetidine (800 mg once daily) and oral 5-fluorouracil (200 mg once daily) for 1 year following curative resection. The cimetidine-treated group had a 10-year survival rate of 84.6% versus 49.8% for the 5-fluorouracil–only group.8

Conclusion

We present this case of recurrent perianal and anal EMPD treated successfully with imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine to highlight a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with EMPD.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Vergati M, Filingeri V, Palmieri G, et al. Perianal Paget’s disease: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4461-4465.

- Liau MM, Yang SS, Tan KB, et al. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease: a 10 year retrospective analysis in an Asian tertiary centre. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:459-462.

- Machida H, Moeini A, Roman LD, et al. Effects of imiquimod on vulvar Paget’s disease: a systematic review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:165-171.

- Knight SR, Proby C, Ziyaie D, et al. Extramammary Paget disease of the perianal region: the potential role of imiquimod in achieving disease control. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:1-3.

- Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)—cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:161-167.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Lam C, Funaro D. Extramammary Paget’s disease: summary of current knowledge. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:807-826.

- Vergati M, Filingeri V, Palmieri G, et al. Perianal Paget’s disease: a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4461-4465.

- Liau MM, Yang SS, Tan KB, et al. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease: a 10 year retrospective analysis in an Asian tertiary centre. Dermatol Ther. 2016;29:459-462.

- Machida H, Moeini A, Roman LD, et al. Effects of imiquimod on vulvar Paget’s disease: a systematic review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;139:165-171.

- Knight SR, Proby C, Ziyaie D, et al. Extramammary Paget disease of the perianal region: the potential role of imiquimod in achieving disease control. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;8:1-3.

- Pantziarka P, Bouche G, Meheus L, et al. Repurposing drugs in oncology (ReDO)—cimetidine as an anti-cancer agent. Ecancermedicalscience. 2014;8:485.

- Matsumoto S, Imaeda Y, Umemoto S, et al. Cimetidine increases survival of colorectal cancer patients with high levels of sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A epitope expression on tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:161-167.

Resident Pearls

- Topical imiquimod cream 5% and oral cimetidine can be a potential alternative treatment regimen for poor surgical candidates with perianal extramammary Paget disease (EMPD).

- Its antineoplastic and immunomodulatory properties may suggest a role for oral cimetidine as an adjuvant therapy in the treatment of perianal EMPD.